Abstract

Chronic scrotal content pain (CSCP) refers to bothersome pain localized to structures within the scrotum that has been present for ≥ 3 months. Etiologies include infection, trauma, and referred pain from the spine, abdomen, and retroperitoneum. However, in many patients there is no obvious identifiable cause. The initial evaluation should include a thorough history and physical examination with adjunctive imaging and laboratory tests as indicated. Treatments vary based on the underlying etiology and include both nonsurgical and surgical options with high levels of success when selectively utilized. The spermatic cord block with local anesthetic is an important tool that helps identify those patients who may benefit from surgery such as microscopic denervation of the spermatic cord. Other treatments including pelvic floor physical therapy may also be indicated in specific circumstances. Using a thoughtful and thorough approach to evaluation and treatment of CSCP, urologists can work with patients to achieve significant improvements in quality of life.

Keywords: Testicle; Pain, inguinal; Denervation; Orchialgia

Chronic scrotal content pain (CSCP), also referred to as chronic testicular pain, chronic scrotal pain, chronic orchialgia, testalgia, and testicular pain syndrome, is characterized by pain or discomfort localized to the contents of the scrotum including the testicle, epididymis, and spermatic cord. To meet diagnostic criteria, the pain must be present for more than 3 months and interfere with activities of daily living.1 This condition may have a significant impact on physical, mental, sexual, and even psychological well-being.2 The underlying etiology is highly variable and includes chronic epididymitis, hydrocele, spermatocele, testicular and paratesticular tumors, and varicocele. Other conditions include post-vasectomy pain syndrome (PVPS), nerve entrapment (post-inguinal hernia repair), pelvic floor tension myalgia, obstructing ureteral calculi, vertebral disk disease, hip pathology, and retroperitoneal tumors.3 However, no obvious etiology is found in a significant proportion of patients, which can be frustrating for the patient and physician.

Significant time and resources are devoted to evaluation and management of CSCP, with yearly attributed costs exceeding $55 million—likely a gross understimation.4 Scrotal pain accounts for 2% to 5% of new outpatient urology clinic visits, and it is also a frequent concern for patients presenting to their primary care physicians, representing nearly 1% of clinic visits for young men.5,6 Moreover, patients see an average of five different providers prior to definitive treatment.7 A general understanding of this entity is imperative for the practicing urologist. Caring for patients with CSCP can be challenging, and there are no universally accepted standardized protocols for diagnosis and treatment. In the following review we discuss the etiology, diagnosis, and management of CSCP and discuss a general algorithm for evaluation and treatment.

Spermatic Cord Neuroanatomy

It is necessary to consider relevant anatomy and physiology. Several peripheral nerves are implicated in genital pain. The genital branch of the genitofermoral nerve arises from lumbar nerve roots (L1–L2).8,9 In addition to transmitting sensory information to the anterolateral scrotum, this nerve also contains motor fibers responsible for the cremasteric reflex. The ilioinguinal nerve (arising from the L1 nerve root) carries sensory fibers innervating the base of the penis, superior scrotum, and medial thigh.10 Branches of the pudendal nerve (sacral nerve roots S2–S4) innervate the scrotal skin posteriorly as well.11 Finally, contributions from the superior, middle, and inferior spermatic nerves are felt to play a dominant role in pain transmission with CSCP.12 These autonomic and somatic sensory nerve fibers originate in the renal/intermesenteric, superior hypogastric, and inferior hypogastric plexi, and are dispersed throughout the spermatic cord.

Spermatic cord neuroanatomy was elegantly studied by Oka and colleagues, who found that up to 50% of nerve fibers lie in close proximity to the vas deferens with another 20% located within the spermatic fascia that surrounds the cord itself.13 Autonomic and somatic sensory nerve fibers “co-localize” within macroscopic nerves, supporting a complex interplay amongst the various neural elements in the setting of CSCP. Wallerian neuronal degeneration, which is also seen in response to cut or crush injury, and other complex processes may also play a role.14

Acute pain stimuli activate local nociceptors, resulting in signal propagation along myelinated A-delta and unmyelinated C fibers.11 At higher neurologic levels, this signal generates impulses that propagate to the spinothalamic tract and other areas of the brain. In contrast, chronic pain is more complex and overall poorly understood.11 However, there is evidence that neuronal remodeling in the peripheral and central nervous system occurs in response to chronic stimulation.15 The process is known as central sensitization, and it may manifest as pain in the absence of noxious stimuli. In the case of chronic pain, this results in changes to a patients' perception of painful (hyperesthesia) and even nonpainful stimuli (allodynia).16 This has important treatment implications that will be subsequently discussed.

CSCP Etiology

The underlying etiology for CSCP varies, and an obvious etiology is not readily identified (idiopathic) in 35% to 45% of patients.3 Table 1 lists common conditions associated with CSCP. Pain is often localized to the testicle and/or epididymis. Patients may also report pain involving the spermatic cord, inguinal region, perineum, and penis with radiation to the ipsilateral abdomen, flank, and even lower extremities.1 The differential diagnosis for the acute scrotum differs from that of chronic scrotal content pain, but overlap does exist.17

Table 1.

Differential Diagnosis for Scrotal Content Pain

| Etiology | Common History and Examination Findings | Adjunctive Testing | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testicle/epididymis | |||

| Epididymo-orchitis |

|

|

|

| Testicular torsion |

|

|

|

| Testicular tumor |

|

|

|

| Testicular infarct |

|

|

|

| Epididymal cyst |

|

|

|

| Spermatocele |

|

|

|

| Hydrocele |

|

|

|

| Spermatic cord/epididymis | |||

| Paratesticular tumor |

|

|

|

| Varicocele |

|

|

|

| Post-vasectomy pain syndrome |

|

|

|

| Other/epididymis | |||

| Obstructing ureteral calculus |

|

|

|

| Inguinal hernia |

|

|

|

| Vascular aneurysm |

|

|

|

| Retroperitoneal mass |

|

|

|

| Spinal pathology |

|

|

|

| Urinary tract infection |

|

|

|

| Chronic pelvic pain syndrome Interstitial cystitis Chronic prostatitis |

|

|

|

| Pelvic floor tension myalgia |

|

|

|

| Idiopathic |

|

||

MDSC, microscopic denervation of the spermatic cord; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; DRE, digital rectal examination.

Pain originating in the testicle or epididymis can arise from several underlying processes. Infectious epididymo-orchitis (viral or bacterial) is a frequent cause of acute pain. The diagnosis can be made by history and physical examination, but scrotal duplex Doppler ultrasound is a useful adjunctive test that will reveal hyperemia in the epididymis and/or testicle. Rapid clinical improvement is seen with antiinflammatory agents and, in some cases, antibiotics. If symptoms persist, one must consider the possibility of an underlying abscess or an alternative diagnosis. However, post-infectious inflammation may result in a period of prolonged discomfort lasting up to 6 weeks or more.18 Supportive care and tincture of time are often all that is necessary. Other infectious causes such as mumps orchitis are quite rare.19 Noninfectious inflammatory epididymitis can result from reflux of urine through the ejaculatory ducts, and it is important to screen these patients for underlying urethral stricture disease or other urologic abnormalities such as Wolffian duct abnormalities.20,21

Scrotal conditions associated with CSCP include epididymal cysts (spermatocele), varicoceles, and even hydroceles (although patients tend to describe pressure rather than true pain). These are readily identified on examination or with scrotal ultrasonography. Benign and malignant scrotal tumors including germ cell tumors, paratesticular sarcomas, and epididymal cystadenomas should be considered in the differential diagnosis, but patients are more likely to present with a painless scrotal mass. If a suspicious solid mass is identified on physical examination or scrotal ultrasound, further work-up including serum tumor markers and cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen and pelvis may be indicated.

Post-vasectomy pain syndrome (PVSP) is another important cause of CSCP.22 Up to 500,000 vasectomies are performed in the United States each year, and the prevalence of post-procedural pain is not inconsequential, with prolonged pain reported in >15% of patients.23,24 Severe pain requiring treatment is far less common, but affects approximately 1% to 2%.25,26 One proposed mechanism involves increased pressure proximal to the vasectomy site causing aberrant neuronal signaling in the densely populated pain fibers within perivasal tissues.13,27 The average time to presentation is approximately 2 years, but this is highly variable—some patients report immediate and lasting pain and others having a delay of many years.24 Clinical examination findings include a painful and swollen epididymis, tender vasectomy site, and sperm granuloma.28

Finally, nonscrotal conditions need to be considered. During embryologic development, the testes arise from the gonadal ridge within the abdominal cavity prior to descent into the scrotum in response to hormonal signaling.29 Referred pain from intra-abdominal processes such as obstructing ureteral calculi, inguinal hernia, abdominal vascular aneurysms, and even retroperitoneal tumors can present with scrotal pain.30 The presence of a new onset varicocele, inguinal bulge, abdominal bruit, or hematuria suggests a possible retroperitoneal or pelvic process masquerading as scrotal pathology. Spinal pathology (eg, slipped disc) should also be considered in patients with a history of concurrent back pain or other neurologic symptoms.31 Finally, testicular pain is reported in nearly 50% of patients diagnosed with chronic pelvic pain from pelvic floor tension, and may be the initial presenting chief complaint.32 Bilateral pain and concurrent bladder, bowel, or sexual symptoms (including painful ejaculation) are frequent in this patient cohort as well.

Evaluation: History, Physical Examination, and Adjunctive Testing

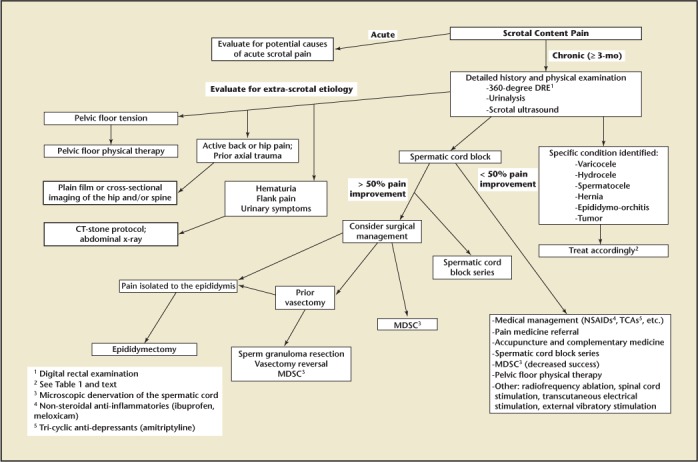

Our basic approach for the evaluation and management of CSCP is shown in Figure 1. Crucial historical elements include the pain location, subjective description (sharp, dull, burning), timing (onset, duration, constant versus intermittent), radiation to surrounding structures, and severity (we use a Likert-type visual-analog pain scale from 0–10). Are there exacerbating factors such as activity or positional changes (ambulation or prolonged sitting)? Does the pain change with urination, defecation, or ejaculation? Is there scrotal swelling or mass? These questions reveal important information as the differential diagnosis is formulated. Patients with scrotal pain often express anxiety related to concern about testicular cancer. Acknowledging these concerns early will create a partnership between the provider and patient.

Figure 1.

Diagnosis and treatment algorithm for CSCP.

The medical history should be scrutinized including prior sexually transmitted diseases, childhood urologic conditions, back and spine pathology, and any underlying psychological conditions such as anxiety or depression. Prior abdominal or pelvic surgery including inguinal hernia repair, varicocelectomy, and surgery for undescended testicle, as well as prior spine or orthopedic surgeries provides clues for an anatomic contribution to CSCP. A detailed social history has implications on diagnosis and treatment as well. For instance, a sexual abuse history has been associated with increased rates of chronic pelvic pain in adulthood and may impact subsequent approaches to physical examination and adjunctive testing.33

A thorough examination of the abdomen and genitalia is mandatory, and clear communication during the examination is imperative. We favor starting the examination with the patient in the upright standing position, focusing on the unaffected side first (or in the case of bilateral pain, the side with less pain) and then transitioning to the affected side. Visual inspection of the scrotum and inguinal region will reveal scars from prior surgery or trauma. Swelling may indicate a solid mass, hydrocele, or varicocele. Careful sequential palpation of the testicle, epididymis, vas deferens, and spermatic cord is performed to elicit focal or more diffuse tenderness. In the case of prior vasectomy, fullness or overt swelling of the epididymis and testicle and pain over the sperm granuloma is often seen. Importantly, a 360-degree digital rectal examination (DRE) with careful palpation of the entire rectal vault, prostate, and pelvic floor musculature should be routinely performed as this can significantly alter treatment recommendations.32 Positive focal or diffuse tenderness involving the prostate or pelvic floor musculature as well as a generalized increase in anal/rectal tone suggest underlying pelvic floor tension myalgia or chronic prostatitis.

Adjunctive testing supplements the history and physical examination. Urinalysis with microscopy should be obtained during the initial evaluation to exclude hematuria or pyuria, both of which can be seen in the case of infectious etiologies or referred pain from urolithiasis. If microscopic hematuria is identified, further work-up includes abdominal/pelvis cross sectional imaging and possibly cystoscopy.34 Scrotal ultrasonography will identify structural causes within the scrotum such as a tumor, cyst, or subclinical varicocele and is recommended in most circumstances. Also, imaging of the spine or hips is indicated if symptoms are suggestive of any underlying involvement of the musculoskeletal system. In the setting of a new onset varicocele, particularly on the right side, cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen and pelvis must be considered to rule out a retroperitoneal or abdominal process.35

One of the most powerful tools in our armamentarium is the spermatic cord block.36 This is indicated for any patient presenting with CSCP who desires definitive management in the absence of an obvious source of referred pain. We perform this in the office using 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine without epinephrine. The spermatic cord is isolated at the pubic tubercle and the medication is instilled into the cord with a 27-gauge needle. Pain improvement after the cord block suggests that afferent input from the genitofermoral, ilioinguinal, and spermatic nerves are at least partially responsible for pain transmission.37 We have found that patients with pain improvement lasting more than 4 hours are more likely to benefit from surgical management.36 A negative response to spermatic cord block (lack of improvement or very short duration) suggests that alternative sources outside of these nerve distributions are responsible for the CSCP, or that central sensitization has occurred. In this setting, surgical intervention is less effective. Of note, some authors advocate for a blinded placebo-controlled spermatic cord injection, with the proposed benefit of excluding malingering and placebo effect.38 However, in the senior author's experience over nearly 3 decades of treating CSCP, he has rarely encountered this in clinical practice. Moreover, there is no definitive data to support placebo-controlled blocks to exclude malingering or other secondary gain. This approach may also damage the patient-physician partnership that is essential when treating chronic pain.39

CSCP Treatment

Nonsurgical Options

Treatment for CSCP suffers from a lack of evidence-based guidance. Although clinical data exists, most reports in the literature regarding treatment consist of small case series without control groups. The nonsurgical treatments discussed herein are all considered off-label. Prior to implementing a definitive treatment plan, and in particular if an invasive treatment is decided upon, it may be necessary to involve colleagues from multiple disciplines including urology, pain medicine, and pelvic floor physical therapy.40 Also, given the extreme psychological toll that accompanies chronic pain, there should be a low threshold for involving a mental health professional in the patient's care plan.41

Conservative management is appropriate after ruling out an underlying structural cause (ie, scrotal mass, varicocele, or inguinal hernia) or a source of referred pain (ie, ureteral calculus, hip or labrum disease, or spinal pathology). This includes sitz baths and supportive undergarments, although these recommendations are for the most part anecdotal.42 If a urinary tract or other genital infection is present, this should be treated accordingly. Antimicrobial therapy for epididymitis is dependent on age and other risk factors.43 Fluoroquinolones and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole have excellent local penetration.44 However, repeated antibiotic courses, as are commonly prescribed, are rarely helpful and prolong the interval to definitive therapy in many patients with CSCP.45 Bilateral pain, pain elicited with ejaculation, and pelvic floor tenderness or “tightness” on DRE are suggestive of underlying pelvic floor tension myalgia. Referral to a pelvic floor therapist for specialized treatment including biofeedback and pelvic floor massage improves pain in many patients.32

When supportive care alone is insufficient, oral agents are another option, although very few studies have evaluated oral treatments specifically for CSCP. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are appealing given their ability to improve pain and inflammation.46 On occasion, this may be the only therapy necessary. However, a neuropathic component plays a role in ≥30% of CSCP patients.3 In fact, antidepressants and anticonvulsants such as gabapentin and pregabalin, which work to modulate neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels, are used to treat CSCP.47 In a small study, Sinclair and colleagues found that >60% of patients receiving gabapentin (dose range, 300–1800 mg daily) reported ≥50% improvement in scrotal pain.48 We have found success with low-dose amitriptyline, which is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) with anticholingergic properties that also blocks reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine.49 It is well tolerated at low doses, with minor side effects including dizziness, xerostomia, and somnolence.50 A careful medication history is mandatory to prevent potential adverse drug interactions. We recommend beginning with amitriptyline, 10 mg, at bedtime, and this can be increased to 20 mg nightly if tolerated. Sinclair and colleagues also found that 4 of 6 patients (67%) taking nortriptyline (another TCA) had a ≥50% improvement in scrotal pain.48 Interestingly, post-vasectomy pain syndrome was associated with a very low response rate to both gabapentin and nortriptyline. Finally, opioid medications are not recommended for CSCP. This is important given current societal concerns surrounding opioid misuse and abuse.51 Moreover, many young men presenting with CSCP desire future fertility and chronic opioid use is associated with malefactor infertility related to secondary hypogonadism.52

As previously discussed, administration of a spermatic cord block has important diagnostic and treatment implications. A cord block utilizing local anesthetic with or without steroid (our agents of choice are bupivacaine and triamcinolone) may also have a direct treatment effect by, in essence, “breaking the cycle” of aberrant afferent peripheral pain signaling.53 The protocol involves a series of spermatic cord injections with 9 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine mixed with 10 mg/1 mL triamcinolone administered once every 2 weeks for a series of 4 to 5 injections. We find this treatment to be most efficacious in patients with adequate response to a diagnostic spermatic cord block and pain duration <6 months.

Spinal cord stimulation is utilized for many other forms of chronic pain, and to date three case reports have shown positive results in patients with CSCP pain refractory to other nonsurgical treatments.54–56 It should be emphasized that this treatment requires placement of a foreign body with inherent risks of infection and mechanical failure necessitating subsequent procedures. Pulsed radiofrequency ablation of the genitofemoral and ilioinguinal nerves is another treatment that has shown some promise.57,58 Hetta and colleagues randomized 70 patients with chronic orchalgia to radiofrequency ablation versus sham.59 They found a significant improvement in pain scores and a decrease in the need for pain medication in the treatment group. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS) diminishes pain signaling via effects on central and peripheral opioid, serotonin, noradrenergic, and muscarinic receptors.60,61 A recently published randomized trial showed that TENS, when used with oral pain medications, resulted in significant improvements in pain scores and quality of life.61 Acupuncture and other complementary medicine techniques may also be considered.62 Finally, Khandwala and colleagues assessed the impact of vibratory stimulation with an external device for CSCP in a 10-patient pilot study, noting a nearly 50% improvement in pain scores along with improvements in pain frequency.63

Surgical Options

Surgical management can offer patients significant and lasting pain improvement. The key to successful surgical outcomes lies in patient selection. If a structure abnormality is present, definitive treatment of the underlying process can significantly improve scrotal pain. Gray and colleagues reported pain resolution rates of 75% to 100% for patients undergoing hydrocelectomy, spermatocelectomy, and varicocelectomy.64 On the other hand, in the absence of an obvious structural cause, the spermatic cord block helps guide treatment decision-making. In those patients with a positive response to the block, defined as at least a 50% reduction in scrotal content pain, surgical treatment may be offered.65 The duration of pain relief with the block varies widely from 15 minutes to 3 weeks, but in our experience a duration >4 hours is consistently associated with improved outcomes.36

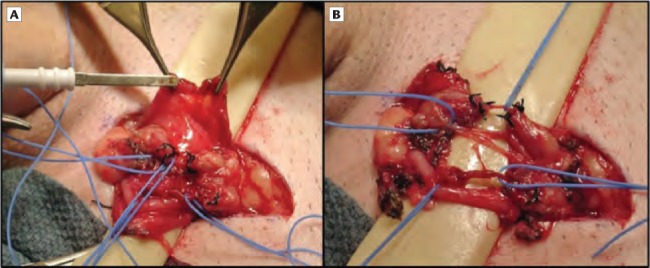

The type of surgical procedure that should be performed depends on the nature and location of the pain. In patients with pain isolated to the epididymis, surgical removal of the epididymis alone (known as epididymectomy) may improve or resolve pain in as many as 75% to 90%.66,67 In contrast, if the pain is localized to the testicle, spermatic cord, or more diffuse throughout the scrotal contents, microscopic denervation of the spermatic cord (MDSC) is the surgical treatment of choice (Figure 2). The procedure involves transecting all of the nerves within the spermatic cord including autonomic and somatic branches of the genital and ilioinguinal nerves.68,69 MDSC is performed in an outpatient setting under general anesthesia. We utilize an open, minimally invasive microsurgical approach. A 3- to 5-cm inguinal incision is made and the spermatic cord is isolated. The ilioinguinal nerve is identified and divided. The operating microscope is used to meticulously dissect the spermatic cord contents. Typically, three separate arteries (testicular, deferential, and cremasteric arteries) can be separately isolated with careful dissection and the aid of a microvascular Doppler probe. Lymphatics are spared to minimize the risk of developing a symptomatic hydrocele. In patients without prior vasectomy, the vas deferens is often left intact, particularly if future fertility is a concern. However, the fascia surrounding the vas is stripped free and divided for a length of 2 cm as 50% of spermatic cord nerves are located in close proximity to the vas deferens.13,14 The cremasteric muscle fibers also contain a significant portion of nervous tissue and this is divided after identifying the cremasteric artery.13 The remaining tissue including internal spermatic veins can then be divided and ligated.

Figure 2.

Microscopic denervation of the spermatic cord. (A) Ligation of the cremasteric fascia after isolation and sparing of the vas deferens, spermatic cord arteries, and several small lymphatic challens, and (B) the final appearance of the spermatic cord.

Prior to surgery, patients should be counseled on possible treatment failure with persistent pain due to accessory pudendal nerve fibers, central sensitization, and malingering.65,68 Risks associated with this procedure include hydrocele formation (<1%) if there is damage to the lymphatic drainage of the testicle as well as testicular atrophy (1%) resulting from injury to the arterial supply.70 Overall, complete pain resolution following MDSC ranges from 50% to 100%, with partial response in 3% to 24%.22,71 In cases of bilateral CSCP that are appropriate for MDSC, we perform the operation on the more severely affected side first to avoid the risk of prolonged postoperative scrotal swelling. In a study of 14 patients with bilateral CSCP who underwent unilateral MDSC, 12 (86%) did not require additional surgery on the contralateral side. Although the mechanism has not been fully elucidated, it is possible that pain may be referred from the more severely affected side to the contralateral scrotal contents, so-called neural cross-talk.22 As an alternative to the traditional operating microscope-assisted approach, Calixte and colleagues reported outcomes in a large cohort of patients undergoing targeted microdenervation of the spermatic cord via a robotic-assisted approach.71 With this technique, the surgeon ligates tissue within the cremasteric muscle fibers, peri-vasal sheath, and posterior spermatic cord lipomatous tissue while leaving the remaining tissue within the spermatic cord intact. At a median followup of 24 months, 83% of patients experienced >50% improvement in pain scores including nearly 50% with complete pain relief.

In contrast, orchiectomy (surgical removal of the entire testicle and spermatic cord) is a final consideration when medical and surgical approaches have been unsuccessful. This should be reserved as a treatment of last resort because preserving the testicle optimizes testosterone production and fertility potential. Moreover, failure rates as high as 30% to 80% have been reported after orchiectomy.72,73

Finally, PVPS deserves special mention. As discussed earlier, the exact etiology is unknown but one hypothesis involves excessive epididymal pressures in response to the iatrogenic obstruction induced at the vasectomy site.25 Vasovasostomy (vasectomy reversal), has been used to reverse this obstruction, and modern series reveal treatment success rates ranging from 50% to 69%.74–76 However, the procedure is rarely covered by medical insurance plans, and this has important financial implications for patients. Moreover, the contraceptive effect of vasectomy is reversed with this approach. In our experience, MDSC is an excellent alternative that maintains the contraceptive benefits of the prior vasectomy and results in significant pain improvement in >70% with PVPS.22

Conclusions

CSCP is a common yet poorly understood condition. The etiology varies widely, and includes processes involving the scrotum, inguinal canal, retroperitoneum, abdominal cavity, and spine. However, in a significant portion of patients with CSCP, the inciting etiology is unknown. By using a stepwise approach to evaluation and management, urologists can significantly improve QOL for patients who are suffering with CSCP.

Main Points.

Chronic scrotal content pain (CSCP), also referred to as chronic testicular pain, chronic scrotal pain, chronic orchialgia, testalgia, and testicular pain syndrome, is characterized by pain or discomfort localized to the contents of the scrotum including the testicle, epididymis, and spermatic cord. To meet diagnostic criteria, the pain must be present for more than 3 months and interfere with activities of daily living.

The underlying etiology for CSCP varies, and an obvious etiology is not readily identified (idiopathic) in 35% to 45% of patients presenting with CSCP.

The evaluation and management of CSCP includes historical elements include the pain location, subjective description (sharp, dull, burning), timing (onset, duration, constant versus intermittent), radiation to surrounding structures, and severity. A thorough examination of the abdomen and genitalia is mandatory.

Conservative management is appropriate after ruling out an underlying structural cause (ie, scrotal mass, varicocele, or inguinal hernia) or a source of referred pain (ie, ureteral calculus, hip or labrum disease, or spinal pathology).

Surgical management can offer patients significant and lasting pain improvement. The key to successful surgical outcomes lies in patient selection. In the presence of a structural abnormality, definitive treatment of the underlying process can significantly improve scrotal pain.

References

- 1.Polackwich AS, Arora HC, Li J, et al. Development of a clinically relevant symptom index to assess patients with chronic orchialgia/chronic scrotal content pain. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7((suppl 2)):S163–S168. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.04.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong MK, Corcoran NM, Adams SJ. Understanding chronic testicular pain: a psychiatric perspective. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79:676–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2009.05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aljumaily A, Al-Khazraji H, Gordon A, et al. Characteristics and etiologies of chronic scrotal pain: a common but poorly understood condition. Pain Res Manag. 2017;2017:3829168. doi: 10.1155/2017/3829168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khandwala YS, Zhang CA, Eisenberg ML. Trends in prevalence, management and cost of scrotal pain in the United States between 2007 and 2014. Urol Pract. 2018;5:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.urpr.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciftci H, Savas M, Yeni E, et al. Chronic orchialgia and associated diseases. Curr Urol. 2010;4:67070. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rottenstreich M, Glick Y, Gofrit ON. Chronic scrotal pain in young adults. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:241. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heidenreich A, Olbert P, Engelmann UH. Management of chronic testalgia by microsurgical testicular denervation. Eur Urol. 2002;41:392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cesmebasi A, Yadav A, Gielecki J, et al. Genitofemoral neuralgia: a review. Clin Anat. 2015;28:128–135. doi: 10.1002/ca.22481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakai T, Murata H, Hara T. A case of scrotal pain associated with genitofemoral nerve injury following cystectomy. J Clin Anesth. 2016;32:150–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rab M, Ebmer Dellon AL. Anatomic variability of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerve: implications for the treatment of groin pain. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1618–1623. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200111000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter CW, Stovall B, Chen G, et al. Anatomy, pathophysiology and interventional therapies for chronic pelvic pain: a review. Pain Physician. 2018;21:147–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motoc A, Rusu MC, Jianu M. The spermatic ganglion in humans: an anatomical update. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2010;51:719–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oka S, Shiraishi K, Matsuyama H. Microsurgical anatomy of the spermatic cord and spermatic fascia: distribution of lymphatics, and sensory and autonomic nerves. J Urol. 2016;195:1841–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parekattil SJ, Gudeloglu A, Brahmbhatt JV, et al. Trifecta nerve complex: potential anatomical basis for microsurgical denervation of the spermatic cord for chronic orchialgia. J Urol. 2013;190:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152((3 suppl)):S2–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buntjen L, Hopf JM, Merkel C, et al. Somatosensory misrepresentation associated with chronic pain: spatiotemporal correlates of sensory perception in a patient following a complex regional pain syndrome spread. Front Neurol. 2017;8:142. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenzo L, Rogel R, Sanchez-Gonzalez JV, et al. Evaluation of adult acute scrotum in the emergency room: clinical characteristics, diagnosis, management, and costs. Urology. 2016;94:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai Y, Yu Z, Shi B, et al. Chronic scrotal pain caused by mild epididymitis: report of a series of 44 cases. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30:638–641. doi: 10.12669/pjms.303.4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tae BS, Ham BK, Kim JH, et al. Clinical features of mumps orchitis in vaccinated postpubertal males: a single-center series of 62 patients. Korean J Urol. 2012;53:865–869. doi: 10.4111/kju.2012.53.12.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shebel HM, Farg HM, Kolokythas O, El-Diasty T. Cysts of the lower male genitourinary tract: embryologic and anatomic considerations and differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2013;33:1125–1143. doi: 10.1148/rg.334125129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg M, Goel A, Sankhwar SN. Urethro-ejaculatory duct reflux, a complication of peno-bulbar urethral stricture: case report with review of the literature. Urol Int. 2014;93:119–121. doi: 10.1159/000350514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan WP, Levine LA. Micro-denervation of the spermatic cord for post-vasectomy pain management. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leslie TA, Illing RO, Cranston DW, Guillebaud J. The incidence of chronic scrotal pain after vasectomy: a prospective audit. BJU Int. 2007;100:1330–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manikandan R, Srirangam SJ, Pearson E, Collins GN. Early and late morbidity after vasectomy: a comparison of chronic scrotal pain at 1 and 10 years. BJU Int. 2004;93:571–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2003.04663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan WP, Levine LA. An overview of the management of post-vasectomy pain syndrome. Asian J Androl. 2016;18:332–337. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.175090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharlip ID, Belker AM, Honig S, et al. Vasectomy: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2012;188((6 suppl)):2482–2491. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson AL, Howards SS. Intratubular hydrostatic pressure in testis and epididymis before and after long-term vasectomy in the guinea pig. Biol Reprod. 1976;14:371–376. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod14.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tandon S, Sabanegh E., Jr Chronic pain after vasectomy: a diagnostic and treatment dilemma. BJU Int. 2008;102:166–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas-Herald AK, Bashamboo A. Gonadal development. Endocr Dev. 2014;27:1–16. doi: 10.1159/000363608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGee SR. Referred scrotal pain: case reports and review. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:694–701. doi: 10.1007/BF02598293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gozon B, Chu J, Schwartz I. Lumbosacral radiculopathic pain presenting as groin and scrotal pain: pain management with twitch-obtaining intramuscular stimulation. A case report and review of literature. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;41:315–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrell MR, Dugan SA, Levine LA. Physical therapy for chronic scrotal content pain with associated pelvic floor pain on digital rectal exam. Can J Urol. 2016;23:8546–8550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu JC, Link CL, McNaughton-Collins M, et al. The association of abuse and symptoms suggestive of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: results from the Boston Area Community Health survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1532–1537. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0341-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linder BJ, Bass EJ, Mostafid H, Boorjian SA. Guideline of guidelines: asymptomatic microscopic haematuria. BJU Int. 2018;121:176–183. doi: 10.1111/bju.14016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanna GB, Byrne D, Townell N. Right-sided varicocele as a presentation of right renal tumours. Br J Urol. 1995;75:798–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benson JS, Abern MR, Larsen S, Levine LA. Does a positive response to spermatic cord block predict response to microdenervation of the spermatic cord for chronic scrotal content pain? J Sex Med. 2013;10:876–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masarani M, Cox R. The aetiology, pathophysiology and management of chronic orchialgia. BJU Int. 2003;91:435–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oomen RJ, Witjens AC, van Wijck AJ, et al. Prospective double-blind preoperative pain clinic screening before microsurgical denervation of the spermatic cord in patients with testicular pain syndrome. Pain. 2014;155:1720–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine LA, Abdelsayed GA. Chronic scrotal content pain: a diagnostic and treatment dilemma. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1212–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ching CB, Hays SR, Luckett TR, et al. Interdisciplinary pain management is beneficial for refractory orchialgia in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2015;11(123):e121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lerman SF, Rudich Z, Brill S, et al. Longitudinal associations between depression, anxiety, pain, and pain-related disability in chronic pain patients. Psychosom Med. 2015;77:333–341. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowen DK, Dielubanza E, Schaeffer AJ. Chronic bacterial prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BMJ Clin Evid. 2015;2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor SN. Epididymitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61((suppl 8)):S770–S773. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Street EJ, Justice ED, Kopa Z, et al. The 2016 European guideline on the management of epididymo-orchitis. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28:744–749. doi: 10.1177/0956462417699356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strebel RT, Schmidt C, Beatrice J, Sulser T. Chronic scrotal pain syndrome (CSPS): the widespread use of antibiotics is not justified. Andrology. 2013;1:155–159. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2012.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho KY, Gwee KA, Cheng YK, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in chronic pain: implications of new data for clinical practice. J Pain Res. 2018;11:1937–1948. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S168188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agarwal MM, Elsi Sy M. Gabapentenoids in pain management in urological chronic pelvic pain syndrome: Gabapentin or pregabalin? Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:2028–2033. doi: 10.1002/nau.23225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sinclair AM, Miller B, Lee LK. Chronic orchialgia: consider gabapentin or nortriptyline before considering surgery. Int J Urol. 2007;14:622–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun Y, Fang Z, Ding Q, Zheng J. Effect of amitriptyline in treatment interstitial cystitis or bladder pain syndrome according to two criteria: does ESSIC criteria change the response rate? Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33:341–344. doi: 10.1002/nau.22407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rheker J, Rief W, Doering BK, Winkler A. Assessment of adverse events in clinical drug trials: identifying amitriptyline's placebo- and baseline-controlled side effects. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;26:320–326. doi: 10.1037/pha0000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Theisen K, Jacobs B, Macleod L, Davies B. The United States opioid epidemic: a review of the surgeon's contribution to it and health policy initiatives. BJU Int. 2018;122:754–759. doi: 10.1111/bju.14446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drobnis EZ, Nangia AK. Pain medications and male reproduction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1034:39–57. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69535-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meacham K, Shepherd A, Mohapatra DP, Haroutounian S. Neuropathic pain: central vs. peripheral mechanisms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21:28. doi: 10.1007/s11916-017-0629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McJunkin TL, Wuollet AL, Lynch PJ. Sacral nerve stimulation as a treatment modality for intractable neuropathic testicular pain. Pain Physician. 2009;12:991–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kiritsy MP, Siefferman JW. Spinal cord stimulation for intractable testicular pain: case report and review of the literature. Neuromodulation. 2016;19:889–892. doi: 10.1111/ner.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nouri KH, Brish EL. Spinal cord stimulation for testicular pain. Pain Med. 2011;12:1435–1438. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen SP, Foster A. Pulsed radiofrequency as a treatment for groin pain and orchialgia. Urology. 2003;61:645. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Basal S, Ergin A, Yildirim I, et al. A novel treatment of chronic orchialgia. J Androl. 2012;33:22–26. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.010991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hetta DF, Mahran AM, Kamal EE. Pulsed radiofrequency treatment for chronic post-surgical orchialgia: a double-blind, sham-controlled, randomized trial: three-month results. Pain Physician. 2018;21:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibson W, Wand BM, O'Connell NE. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for neuropathic pain in adults. The Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:Cd011976. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011976.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tantawy SA, Kamel DM, Abdelbasset WK. Does transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation reduce pain and improve quality of life in patients with idiopathic chronic orchialgia? A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Res. 2018;11:77–82. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S154815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu BP, Wang YT, Chen SD. Effect of acupuncture on clinical symptoms and laboratory indicators for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48:1977–1991. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1403-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khandwala YS, Serrano F, Eisenberg ML. Evaluation of external vibratory stimulation as a treatment for chronic scrotal pain in adult men: a single center open label pilot study. Scand J Pain. 2017;17:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gray CL, Powell CR, Amling CL. Outcomes for surgical management of orchalgia in patients with identifiable intrascrotal lesions. Eur Urol. 2001;39:455–459. doi: 10.1159/000052485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larsen SM, Benson JS, Levine LA. Microdenervation of the spermatic cord for chronic scrotal content pain: single institution review analyzing success rate after prior attempts at surgical correction. J Urol. 2013;189:554–558. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Siu W, Ohl DA, Schuster TG. Long-term follow-up after epididymectomy for chronic epididymal pain. Urology. 2007;70:333–335. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.03.080. discussion 335-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hori S, Sengupta A, Shukla CJ, et al. Long-term outcome of epididymectomy for the management of chronic epididymal pain. J Urol. 2009;182:1407–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levine LA. Microsurgical denervation of the spermatic cord. J Sex Med. 2008;5:526–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Strom KH, Levine LA. Microsurgical denervation of the spermatic cord for chronic orchialgia: long-term results from a single center. J Urol. 2008;180:949–953. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tan WP, Levine LA. What can we do for chronic scrotal content pain? World J Mens Health. 2017;35:146–155. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.17047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Calixte N, Tojuola B, Kartal I, et al. Targeted robotic assisted microsurgical denervation of the spermatic cord for the treatment of chronic orchialgia or groin pain: a single center, large series review. J Urol. 2018;199:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levine LA, Hoeh MP. Evaluation and management of chronic scrotal content pain. Curr Urol Rep. 2015;16:36. doi: 10.1007/s11934-015-0510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Costabile RA, Hahn M, McLeod DG. Chronic orchialgia in the pain prone patient: the clinical perspective. J Urol. 1991;146:1571–1574. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shapiro EI, Silber SJ. Open-ended vasectomy, sperm granuloma, and postvasectomy orchialgia. Fertil Steril. 1979;32:546–550. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)44357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Myers SA, Mershon CE, Fuchs EF. Vasectomy reversal for treatment of the post-vasectomy pain syndrome. J Urol. 1997;157:518–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nangia AK, Myles JL, Thomas AJ. Vasectomy reversal for the post-vasectomy pain syndrome: a clinical and histological evaluation. J Urol. 2000;164:1939–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]