Abstract

Cancer cells are characterized by a high glycolytic rate, which leads to energy regeneration and anabolic metabolism; a consequence of this is the abnormal expression of pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2 (PKM2). Multiple studies have demonstrated that the expression levels of PKM2 are upregulated in numerous cancer types. Consequently, the mechanism of action of certain anticancer drugs is to downregulate PKM2 expression, indicating the significance of PKM2 in a chemotherapeutic setting. Furthermore, it has previously been highlighted that the downregulation of PKM2 expression, using either inhibitors or short interfering RNA, enhances the anticancer effect exerted by THP treatment on bladder cancer cells, both in vitro and in vivo. The present review summarizes the detailed mechanisms and therapeutic relevance of anticancer drugs that inhibit PKM2 expression. In addition, the relationship between PKM2 expression levels and drug resistance were explored. Finally, future directions, such as the targeting of PKM2 as a strategy to explore novel anticancer agents, were suggested. The current review explored and highlighted the important role of PKM2 in anticancer treatments.

Keywords: PKM2, cancer, chemotherapeutic drugs, resistance, target

1. Introduction

Cancer is a disease with a high prevalence and mortality rate, and its treatment represents a considerable clinical challenge. The benefits of current chemotherapeutics are limited due to their propensity to cause DNA damage in normal cells (1). Therefore, research has been directed towards finding safer and more sustainable cancer treatments. Notably, it has been demonstrated that targeting the regulation of tumor cell metabolism, without causing toxicity in normal cells, is a potential strategy for the treatment or adjuvant therapy of cancer (2).

The metabolic mechanism is one of a multitude of differential characteristics separating cancer cells from normal cells. Tumor cells are primarily dependent on aerobic glycolysis to obtain energy and produce lactate, even in the presence of oxygen (3). Recently, the targeting of cancer cell metabolism has gained traction as an effective strategy for the development of new cancer treatments (4,5). In 2017, the Food and Drug Administration approved Enasidenib (AG-221), an inhibitor of the mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) protein, for the treatment of relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (6). In addition to IDH2, pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2 (PKM2) has also emerged as a critical regulator of cancer cell metabolism. PK is an enzyme that plays a critical function in the glycolytic pathway, catalyzing the final, rate-limiting step of glycolysis by converting phosphoenolpyruvate and ADP to pyruvate and ATP, respectively (7,8). Alternate splicing of PKM pre-mRNA by heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1/2 and polypyrimidine-tract binding protein (PTBP1), results in PKM2 generation (9). There is mounting evidence that unlike other PK isoforms, PKM2 is upregulated in multiple carcinomas, including colorectal (10), lung (11), liver (12), breast cancer (13) and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (14). The general molecular mechanisms involved in tumor growth are briefly summarized in Fig. 1.

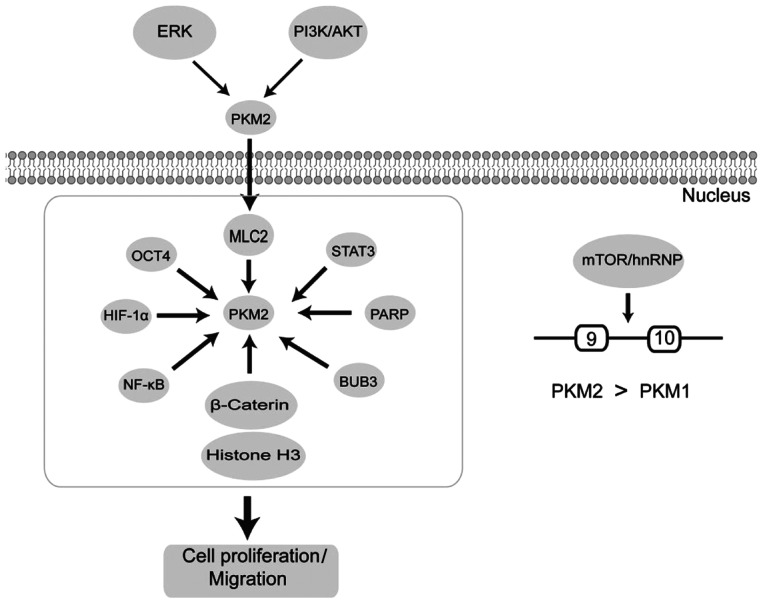

Figure 1.

Pathways related to tumor growth involving PKM2. PKM2 is phosphorylated by ERK2 or PI3K/AKT resulting the nuclear translocation of PKM2. Nuclear PKM2 binds to proteins upregulating transcriptional activity, thereby promoting the Warburg effect and tumorigenesis; hnRNP induces PKM2 via alternative splicing of PKM genes to stimulate cancer cell invasion and migration. PKM2, pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2; HIF1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1α; hnRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins; MLC2, myosin light chain 2; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1; BUB3, BUB3 mitotic checkpoint protein; OCT4, octamer-binding transcription factor 4.

The upregulation of PKM2 expression enhances chemosensitivity in breast (15), gastric (16) and colorectal cancer (17). High expression levels of PKM2 have been shown to be associated with increased chemosensitivity to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and epirubicin in breast and cervical cancer (15,18). By contrast, PKM2 contributes to gefitinib resistance via the upregulation of STAT3 in colorectal cancer (19). Moreover, the downregulation of PKM2 leads to cell apoptosis and increases the sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapy (20). This highlights the ability of PKM2 to alter cell sensitivity to chemotherapy.

The present review summarizes the advancements in targeting PKM2 expression as a novel therapeutic strategy. The underlying mechanisms, and the potential for future clinical translation, were also analyzed. An informative overview of PKM2 is detailed, establishing a precedent for the development of clinical therapeutics that target PKM2, for the treatment of cancer.

2. Biochemical role of PKM2 in physiological processes

PKM2 can function as: i) A metabolic enzyme; ii) a protein kinase; or iii) a transcriptional coactivator of genes that influence cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis. It has been demonstrated that the inhibition of PKM2 slows tumor growth or causes tumor cell death (21). Following PKM2 inhibition, a reduction in cancer cell proliferation and survival have both been observed (21,22). RNA interference and peptide aptamers that ablate PKM2 have been reported to elicit anticancer effects, such as the impairment of tumor growth, the induction of apoptotic cell death and increasing sensitivity to chemotherapy (20,23–26). Conversely, a PKM2 activator was proven to effectively induce apoptosis in lung cancer cells via the inhibition of AKT phosphorylation (27). The aforementioned findings support the hypothesis that PKM2 represents a promising therapeutic target.

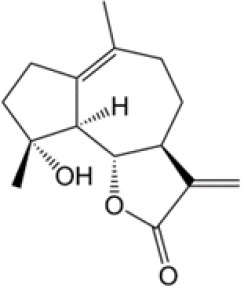

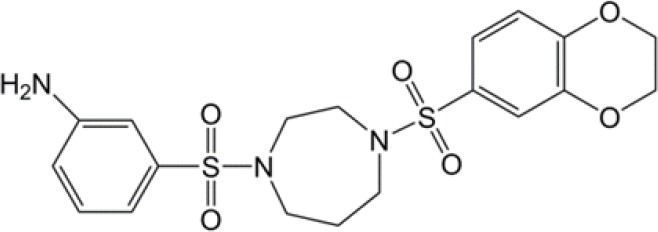

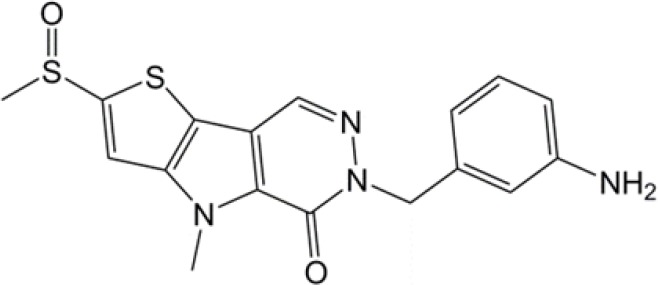

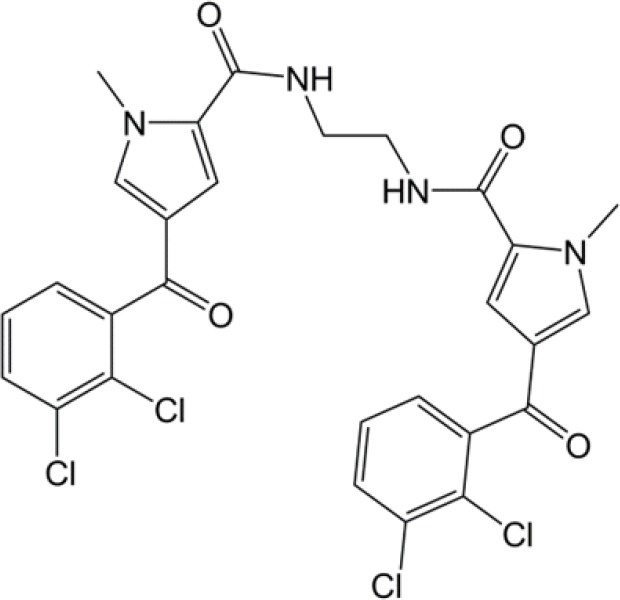

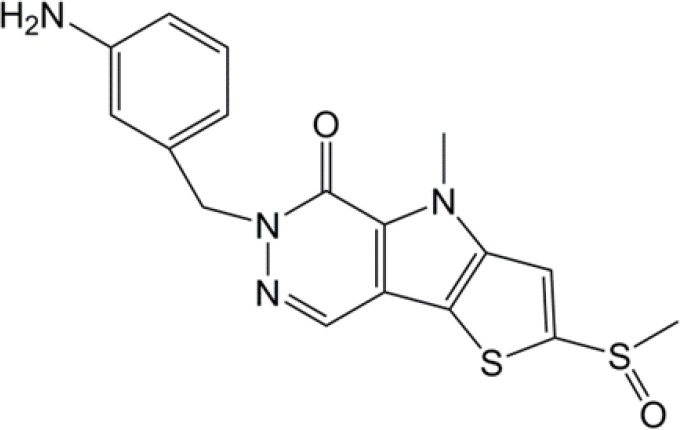

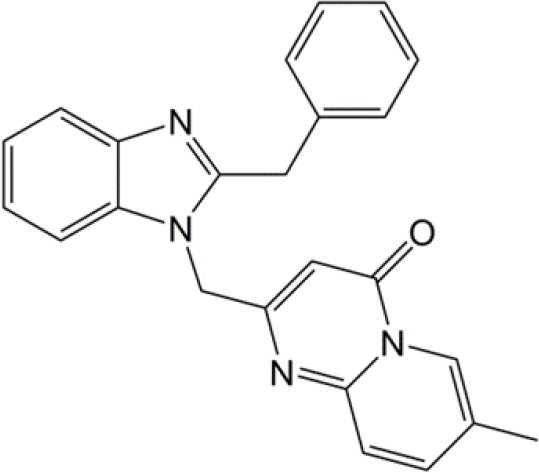

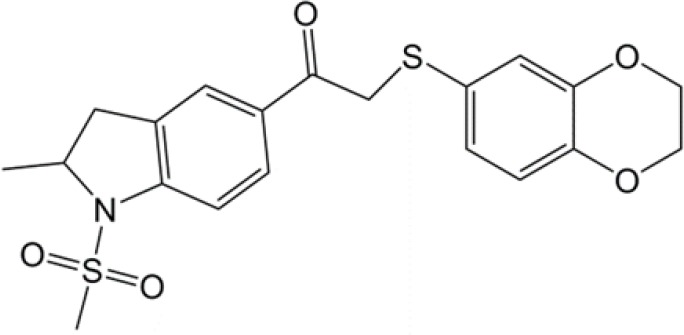

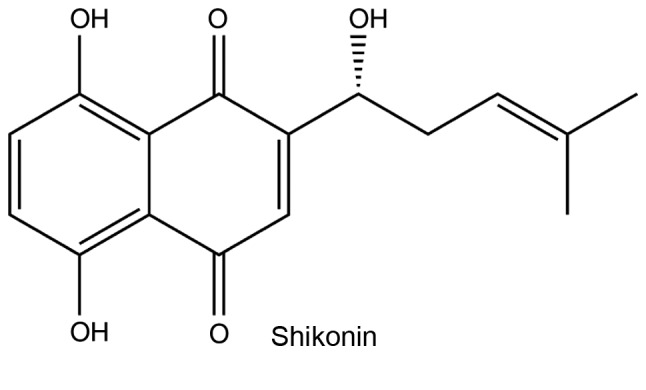

Activators of PKM2 exert their effects by stabilizing the molecular in its tetramer form, subsequently affecting cancer cell metabolism and indicating a novel anti-cancer therapeutic strategy (28). To date, several PKM2 activators have been reported, including N,N′-diarylsulfonamide (29) and 2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)methyl)-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones (30). The structures of certain PKM2 activators are detailed in Table I (29–35). Conversely, PKM2 inhibitors (such as shikonin; Fig. 2) have been studied and will be explored in the following sections.

Table I.

Structures of representative PKM2 activators.

| PKM2 activators | Structures | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|

| Micheliolide |  |

(31) |

| Diarylsulfonamides |  |

(29) |

| Thieno[3,2-b]pyrrole[3,2-d]pyridazinones |  |

(32) |

| 4-(2,3-dichlorobenzoyl)-1-methyl-pyrrole-2-carboxamide |  |

(33) |

| TEPP-46 |  |

(34) |

| 2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)methyl)-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones |  |

(30) |

| 1-(sulfonyl)-5-(arylsulfonyl)indoline |  |

(35) |

PKM2, pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of shikonin.

3. PKM2-inhibitory compounds

Shikonin

Shikonin is an active chemical component extracted from Lithospermum erythrorhizon, which has been found to exert multiple pharmacological effects. Notably, it exhibits antitumor properties in numerous human cancer types (36,37). Shikonin has been identified as a PKM2 inhibitor and is able to reduce the rate of cancer cell glycolysis (38). Additionally, one study determined that shikonin improved the therapeutic efficacy of Taxol, and reduced chemoresistance to cisplatin in advanced bladder cancer (BC) via the inhibition of PKM2 (38). In summary, shikonin is able to inhibit tumor growth by suppressing aerobic glycolysis, which is mediated by PKM2 in vivo (39).

Li et al (40) demonstrated that PKM2 expression levels were higher in skin tumor tissues than normal tissues. Moreover, it was also observed that shikonin inhibited cancer-cell transformation and PKM2 activation, which was induced by the tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate in the early stages of carcinogenesis. Furthermore, another study indicated that shikonin reduced epidermal growth factor receptor, PI3K, p-AKT, Hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and PKM2 expression levels. Moreover, the viability of esophageal cancer cells was decreased and cell apoptosis was induced in the presence of shikonin (41). Additionally, increased expression levels of PKM2 increase the resistance of esophageal cancer cells to shikonin. It was observed that shikonin exerted its chemotherapeutic effects via the induction of cell apoptosis in vivo. To summarize, shikonin was determined to inhibit esophageal and bladder cancer progression via the inhibition of PKM2 expression (41,42).

However, because the clinical use of shikonin as an anticancer agent is still limited by its toxicity and poor solubility (43), it is problematic to incorporate directly into cancer therapy regimes. The study of PKM2 inhibitors is ongoing and the discovery of novel inhibitors with low toxicity would confer great benefit to patients with cancer (44).

Metformin

Metformin (a commonly prescribed drug used for the treatment of type II diabetes) has been extensively investigated as a metabolic modulator, but also exhibits anticancer properties. Epidemiological evidence has demonstrated that metformin exhibits high potential efficacy as an antitumor agent (45). Data gathered from multiple xenograft cancer models suggest that metformin may inhibit the progression and recrudescence of cancer (46).

Moreover, metformin induces tumor cell death and increases sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs via the inhibition of PKM2. For instance, Shang et al (47) demonstrated that metformin enhanced the sensitivity of osteosarcoma stem cells to cisplatin, by reducing the expression level of PKM2. Mechanistically, it was confirmed that upregulated expression levels of PKM2 were responsible for resistance to cisplatin in osteosarcoma stem cells. Additionally, PKM2 downregulation by metformin has been shown to result in the inhibition of glucose uptake, lactate production and ATP production in human osteosarcoma cancer stem cells (CSCs). Metformin was also found to exert a significant antitumor effect on gastric cancer cells via inhibition of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)1α/PKM2 signaling pathway (48). Moreover, it was determined that the upregulation of PKM2 induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which in turn increased the invasion and metastatic potential of carcinoma cells (49). Cheng et al (50) discovered that metformin inhibits transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)-induced EMT in cervical cancer cells, and also investigated the mechanisms involved in tumorigenesis (which reduced PKM2 expression levels). Furthermore, the present authors demonstrated that decreased PKM2 expression levels, induced by metformin, enhanced the efficiency of THP (Docetaxel, Trastuzumab and Pertuzumab) for BC treatment (51).

Vitamin K (VK)3 and 5

VK family members are essential and fat-soluble naphthoquinones that serve vital physiological roles (52). Numerous studies have suggested that VK3 and 5 are promising anticancer adjuvants, both in vitro and in vivo (53–57). It has been demonstrated that combination therapy with VK3 and vitamin C exerts a synergistic anticancer effect in Jurkat and K562 cells (58,59). VK3 also improves the efficacy of anticancer drugs such as doxorubicin (DOX) (58,60). Moreover, a clinical trial suggested that VK3 improves cell sensitivity to Inopera: Chen et al (61) discovered that VK3 and 5 inhibit PKM2 significantly more than PKM1 and pyruvate kinase isoenzyme L, while other isoforms of PK are predominantly expressed in most adult tissues and the liver. This study further demonstrated that VK3 and 5 have the potential to exert a therapeutic effect on cancer cells via the suppression of PKM2 expression.

Temozolomide (TMZ)

TMZ is an antitumor drug that damages DNA, and is used to treat glioblastoma (GBM). It also inhibits the rate of pyruvate-to-lactate transformation (62–64). Park et al (65) demonstrated that TMZ alters PKM2 expression, leading to changes in pyruvate metabolism, and highlighting that PKM2 plays a key role in the DNA-damage response.

4. PKM2 activity influences chemosensitivity

Resistance to chemotherapy is a major challenge concerning cancer treatment; therefore, overcoming the development of resistance in cancer cells remains a primary focus (66). Drug-resistant cancer cells exhibit an increased glycolytic rate, meaning that targeting glycolysis may represent a novel strategy to reduce the adverse effects of drug resistance (67). Therefore, the role of PKM2 in the development of chemoresistance in cancer cells, and the targeting of PKM2 expression, are important factors that could help to increase the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapy.

Gemcitabine (GEM)

GEM is a targeted drug metabolite with two fluorine atoms that has been suggested by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines as a first-line chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of pancreatic cancer (68); however, only a small proportion of patients respond positively to GEM. Despite a meta-analysis showing that the combination of GEM with other therapeutics results in significantly higher disease response rates, and longer progression-free and overall survival, after several typical chemotherapy treatment cycles, the emergence of drug resistance often leads to therapeutic failure (69).

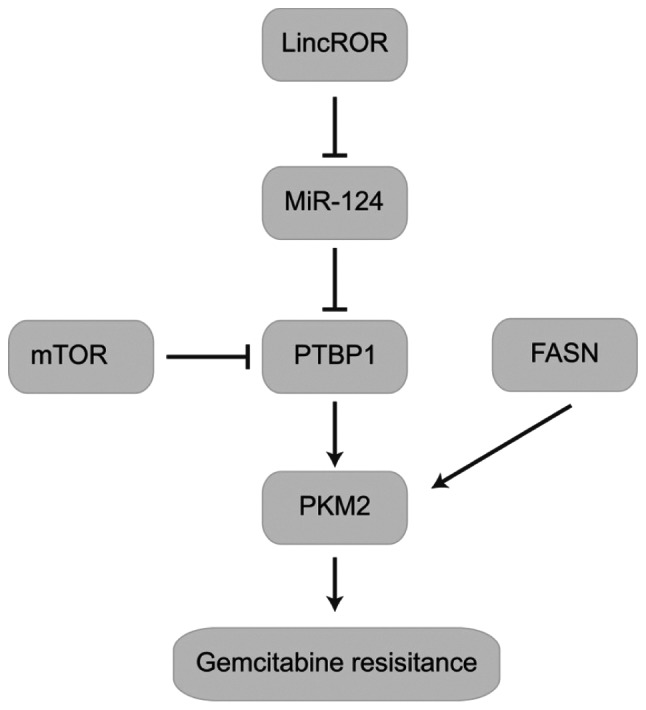

The resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to GEM involves PKM2 expression and its nonmetabolic function. Thus, PKM2 should be considered a therapeutic target in GEM-resistant pancreatic cancer cells (70,71). The role of PKM2 in GEM resistance is demonstrated in Fig. 3. Kim et al (72) discovered that PKM2-knockdown induced tumor protein 53 activation via the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, following treatment with GEM. Subsequent apoptosis was then induced through the activation of caspase 3/7 and poly ADP-ribose polymerase cleavage. These findings further indicate PKM2 as a novel target for the treatment of GEM resistance, and also support the combination of GEM with a PKM2 inhibitor for treating pancreatic cancer.

Figure 3.

Major role of PKM2 in gemcitabine resistance. The lincROR/miR-124/PTBP1/PKM2 complex is involved in the regulation of gemcitabine resistance. FASN regulates PKM2 expression and is associated with gemcitabine resistance. LincROR, long intergenic non-protein coding RNA, regulator of reprogramming PKM2, pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2; PTBP1, polypyrimidine tract binding protein; FASN, Fatty acid synthase; miR, micro RNA.

Calabretta et al (73) mechanistically characterized a novel PTBP1/PKM2 pro-survival pathway, triggered by chronic treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells with GEM. It was observed that alternative splicing of PKM was found to be differently regulated in DR-PDAC cells, leading to an increase in the cancer-associated PKM2 isoform. Moreover, upregulation of PKM2 expression was also associated with shorter recurrence-free survival times in patients with PDAC. These findings indicate that PKM2 is a novel potential therapeutic target that may improve the response of PDAC to chemotherapy, and reduce the resistance of cancer cells to current treatments (73). Li et al (71) also determined that GEM resistance to pancreatic cancer cells is associated with a long intergenic non-protein coding RNA, regulator of reprogramming /PTBP1/PKM2 axis (71).

Platinum

Cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin (OXA) are typically used to treat human cancers. However, their clinical success is limited by severe side effects and intrinsic or acquired resistance (74).

Cisplatin

Cisplatin, the first discovered platinum anticancer drug, is active against a wide spectrum of solid neoplasms, including ovarian, bladder, colorectal and lung cancer (75–77). However, treatment with cisplatin often results in drug resistance and several adverse side effects (78).

Wang et al (76) determined that shikonin inhibited PKM2 and reduced BC cell survival time in a dose-dependent, but also a PK activity-independent manner. PKM2 upregulation is strongly associated with cisplatin resistance; however, cisplatin-resistant cells respond sensitively to shikonin when PKM2 is upregulated. In mice, the combination of shikonin and cisplatin significantly reduced BC growth and metastasis (in contrast to monotherapy with either drug). Thus, PKM2 is indicated as a key factor in the development of resistance to cisplatin treatment in advanced BC. Suppression of PKM2 via RNAi or specific inhibitors may be an effective approach to reducing resistance and improving the outcomes of patients with advanced BC (76). Furthermore, a study conducted by Shang et al (47) confirmed that osteosarcoma stem cells exhibit significantly higher levels of cisplatin resistance compared with osteosarcoma non-CSCs. The aforementioned results indicated that PKM2 upregulation caused resistance to cisplatin in osteosarcoma stem cells.

Zhu et al (18) collected tumor tissues from 36 patients with cervical cancer (pre- and post-chemotherapy). The expression levels of multiple tumor-associated proteins (including PKM2 and HIF1α) were then determined using immunohistochemistry. As a result, it was discovered that the mTOR/HIF-1α/c-Myc/PKM2 signaling pathway was significantly downregulated in patients with cervical cancer, following chemotherapy. It was then demonstrated that PKM2 inhibited the proliferation of cervical cancer cells, and enhanced their sensitivity to cisplatin in vitro. Additionally, PKM2 was inextricably associated with the mTOR pathway. PKM2 and mTOR expression in cervical cancer tissues may serve as predictive biomarkers for the use of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Consequently, it was concluded that PKM2 increased the sensitivity of cervical cancer cells to cisplatin, by interacting with the mTOR signaling pathway.

It has been demonstrated that PKM2 is closely associated with the sensitivity of certain cancer cells to cisplatin. However, PKM2 may exert an opposing effect by either increasing or decreasing the antitumor activity of cisplatin. Table II summarizes the effect of PKM2 on the sensitivity of multiple tumors to cisplatin treatment (18,47,76,79,80).

Table II.

Effect of pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2 on cisplatin sensitivity in different cancers.

| Cancer type | Effect | Treatment | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder cancer | Overcomes resistance | Shikonin | (76,79) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Chemosensitivity | MicroRNA-199a | (80) |

| Osteosarcoma | Chemosensitivity | Metformin | (47) |

| Cervical cancer | Chemosensitivity | PKM2 | (18) |

PKM2, pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2.

Carboplatin

Carboplatin is also a platinum-based chemotherapeutic drug. It is an effective treatment for various solid tumor types, particularly non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (81). However, NSCLC cells commonly develop resistance following carboplatin treatment (82). Liu et al (83) investigated carboplatin-resistant NSCLC models using the A549 and PC9 lung cancer cell lines, termed A549/R and PC9/R, respectively. It was discovered that as well as the low sensitivity of A549/R and PC9/R cells to carboplatin treatment, resistant cells exhibited higher glucose metabolism than wild type cells. Mechanistically, it was confirmed that a high expression level of PKM2 in A549/R and PC9/R cells was dependent on both a high rate of glucose metabolism, and carboplatin resistance (83).

OXA

OXA is a third-generation platinum-based compound (84) and is the first platinum-based therapy to categorically exhibit clinical activity against CRCs (85). However, an increasing number of research reports have detailed the development of OXA resistance in CRC therapy, and this has become problematic for its clinical application (86,87). Despite this, it has been elucidated that PKM2 is associated with OXA resistance in vitro (88,89). In conclusion, PKM2 may play an important role in the development of OXA resistance in cancer cells.

5-FU

5-FU is an anticancer drug, commonly used in the treatment of colon cancer. Acquired resistance is becoming a key challenge for the treatment of patients in the advanced stages of colon cancer (90). He et al (91) discovered that aerobic glycolysis was significantly upregulated in 5-FU-resistant cells (91). It was also reported that PKM2 is targeted by miR-122 in colon cancer cells. High expression levels of miR-122 in 5-FU-resistant cells has been shown to reduce resistance to 5-FU through the inhibition of PKM2, both in vitro and in vivo. In summary, research indicates that enhanced glucose metabolism reduces 5-FU resistance to cancer cells, and that the inhibition of glycolysis may be a possible therapeutic method to overcome 5-FU resistance (91,92).

DOX

DOX is an anticancer drug used to treat hepatocellular carcinoma. Acquired drug resistance following treatment represents a major challenge for both DOX and other chemotherapeutic agents. Pan et al (93) determined that the expression levels of miR-122 were lower in DOX-resistant Huh7/R cells compared with wild type cells, demonstrating that miR-122 is associated with chemoresistance to DOX. This was supported by the results of a luciferase reporter assay. High expression levels of miR-122 in Huh7/R cells were shown to reverse doxorubicin resistance via the inhibition of PKM2, leading to DOX-resistant cancer cell apoptosis. Therefore, it was demonstrated that the upregulation of glucose metabolism increases resistance to DOX, thus, inhibition of glycolysis by miR-122 may represent a potential therapeutic strategy to reduce DOX resistance in liver cancer (93).

Docetaxel

Docetaxel, a derivative of taxane, is an antineoplastic drug that is effective for the treatment of multiple malignant tumor types. It inhibits microtubule disassembly, consequently interfering with mitotic progress by blocking cells at the G2/M checkpoint, and promoting apoptosis (94). Docetaxel is widely used to treat breast cancer (95–97), NSCLC (98,99) and other solid tumors (100), exhibiting significant therapeutic efficacy.

Shi et al (11) determined that combining plasmid short hairpin (sh)RNA-PKM2 with standard docetaxel treatment significantly improved its efficacy (11). Moreover, a significant reduction in the expression level of PKM2 markedly suppressed A549 cell proliferation (11). Yuan et al (66) investigated the effect of PKM2 silencing combined with docetaxel treatment, on cell viability, cell cycle distribution and apoptosis of the A549 and H460 NSCLC cell lines. shRNA-PKM2 could serve as a combination therapy with docetaxel in patients with NSCLC by reducing PKM2 expression, resulting in decreased cell viability, an increase in cell cycle arrest at the G2/M checkpoint, and apoptosis. These results further suggest that targeting PKM2 has the potential to improve the treatment outcomes of patients with NSCLC, by increasing the chemotherapeutic efficacy of docetaxel (66).

5. Conclusions

Cancer is a fatal and prevalent disease with a high mortality rate worldwide, and it is predicted that the number of new cancer cases will increase to 19.3 million per year by 2025 (101). The reprogramming of cell metabolism is essential for tumorigenesis and is regulated by a complex network, in which PKM2 plays a critical role (102). PKM2 is typically upregulated in rapidly proliferating cells, such as cancerous and embryonic cells. It has been suggested that PKM2 plays an important role in cancer progression through the regulation of both metabolic and nonmetabolic pathways. Intermediate products of glycolysis, such as amino acids, nucleotides and lipids are required to sustain the rapid growth of cancer cells (103). Furthermore, high patient mRNA expression levels of PKM2 are associated with reduced median overall survival time (104). Interestingly, PKM2 can also serve as a biomarker, indicating patient sensitivity to chemotherapy. It has been demonstrated that downregulation of PKM2 expression improved the anticancer efficacy of THP treatment (51), thus, the clinical application of PKM2 activators and inhibitors in cancer therapy warrants further investigation.

In the present review, the antitumor effects of various PKM2 inhibitors were summarized. A multitude of in vitro and in vivo studies have determined the role of PKM2 in tumorigenesis and progression. Moreover, the effect of PKM2 on the sensitivity of cancer cells to certain clinically-available chemotherapeutic drugs was investigated. Numerous studies have confirmed that the inhibition of PKM2 increased tumor cell sensitivity to chemotherapy. However, PKM2 increased the sensitivity of cervical cancer cells to cisplatin by interacting with the mTOR pathway (18). The association between PKM2 expression and the development of resistance has been investigated in several types of cancer, albeit with conflicting results. A potential explanation for these discrepancies is that PKM2 has been proposed to fluctuate between different forms in order to regulate glucose metabolism. The low activity dimeric form supports cell growth by increasing the levels of glycolytic intermediates necessary for biosynthetic processes. However, when energy levels decrease, the enzyme can switch to the high activity tetrameric form and facilitate oxidative phosphorylation (20). Therefore, the resulting mechanisms may be quite different. Another explanation for the conflicting results may be that cancer cells possess the ability to alter their metabolism and regulate sensitivity to chemotherapeutics (80). Although PKM2 has become a focus of research in recent years, the development of specific inhibitors and activators of PKM2 remains to be achieved. Moreover, limited research has been conducted on results from clinical trials. It is suggested that the intervention of cancer cell metabolism via the precise regulation of PKM2 expression and activity may represent a promising translational application that warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PKM2

pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2

- PTBP1

polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha

- CSCs

cancer stem cells

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor β1

- P53

tumor protein 53

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- OS

overall survival

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- NSCLC

non-small-cell lung carcinoma

Funding

The present review was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81874212), the Hunan Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2016JJ2187), the Key Project of Hunan Province 2016 (grant no. 2016JC2036) and start-up funds of the Key Laboratory of Study and Discovery of Targeted Small Molecules of Hunan Province (grant no. 2017TP020) to XY, and from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81703008) and the Institutional Fund of Xiangya Hospital Central South University (grant no. 2016Q02) to MP.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

QS wrote the manuscript draft. QS, QT, JD, SZ, MP and TT contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. XY and SL revised the manuscript. QS, DJ and XY conceived the design of the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Li Y, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Li J, Chen K, Zhang L, Deng M, Deng S, Li P, Xu B. Cooperative effect of chidamide and chemotherapeutic drugs induce apoptosis by DNA damage accumulation and repair defects in acute myeloid leukemia stem and progenitor cells. Clin Epigenetics. 2017;9:83. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0377-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: A cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang YP, Ward NP, DeNicola GM. Recent advances in cancer metabolism: A technological perspective. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:31. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0027-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pagés M, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Cancer metabolism: A therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:11–31. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA, Fathi AT, Roboz GJ, Altman JK, Stone RM, DeAngelo DJ, Levine RL, Flinn IW, et al. Enasidenib in mutant IDH2 relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017;130:722–731. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-779405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayley JP, Devilee P. The Warburg effect in 2012. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:62–67. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32834deb9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazurek S. Pyruvate kinase type M2: A key regulator of the metabolic budget system in tumor cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shinohara H, Taniguchi K, Kumazaki M, Yamada N, Ito Y, Otsuki Y, Uno B, Hayakawa F, Minami Y, Naoe T, Akao Y. Anti-cancer fatty-acid derivative induces autophagic cell death through modulation of PKM isoform expression profile mediated by bcr-abl in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Lett. 2015;360:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taniguchi K, Sugito N, Kumazaki M, Shinohara H, Yamada N, Nakagawa Y, Ito Y, Otsuki Y, Uno B, Uchiyama K, Akao Y. MicroRNA-124 inhibits cancer cell growth through PTB1/PKM1/PKM2 feedback cascade in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;363:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi HS, Li D, Zhang J, Wang YS, Yang L, Zhang HL, Wang XH, Mu B, Wang W, Ma Y, et al. Silencing of pkm2 increases the efficacy of docetaxel in human lung cancer xenografts in mice. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:1447–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Q, Lin Z, Xu J, Lu Y, Meng Q, Wang C, Yang Y, Xin X, Li X, Pu H, et al. Long noncoding RNA MEG3 suppresses liver cancer cells growth through inhibiting β-catenin by activating PKM2 and inactivating PTEN. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:253. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0305-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benesch C, Schneider C, Voelker HU, Kapp M, Caffier H, Krockenberger M, Dietl J, Kammerer U, Schmidt M. The clinicopathological and prognostic relevance of pyruvate kinase M2 and pAkt expression in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:1689–1694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lockney NA, Zhang M, Lu Y, Sopha SC, Washington MK, Merchant N, Zhao Z, Shyr Y, Chakravarthy AB, Xia F. Pyruvate kinase muscle isoenzyme 2 (PKM2) expression is associated with overall survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:390–398. doi: 10.1007/s12029-015-9764-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin Y, Lv F, Liu F, Guo X, Fan Y, Gu F, Gu J, Fu L. High expression of pyruvate kinase M2 is associated with chemosensitivity to epirubicin and 5-fluorouracil in breast cancer. J Cancer. 2015;6:1130–1139. doi: 10.7150/jca.12719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo BC, Ku JL, Hong SH, Shin YK, Park SY, Kim HK, Park JG. Decreased pyruvate kinase M2 activity linked to cisplatin resistance in human gastric carcinoma cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:532–539. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Balibrea E, Plasencia C, Ginés A, Martinez-Cardús A, Musulén E, Aguilera R, Manzano JL, Neamati N, Abad A. A proteomic approach links decreased pyruvate kinase M2 expression to oxaliplatin resistance in patients with colorectal cancer and in human cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:771–778. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu H, Wu J, Zhang W, Luo H, Shen Z, Cheng H, Zhu X. PKM2 enhances chemosensitivity to cisplatin through interaction with the mTOR pathway in cervical cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30788. doi: 10.1038/srep30788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q, Zhang D, Chen X, He L, Li T, Xu X, Li M. Nuclear PKM2 contributes to gefitinib resistance via upregulation of STAT3 activation in colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16082. doi: 10.1038/srep16082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, Fleming MD, Schreiber SL, Cantley LC. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 2008;452:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prakasam G, Singh RK, Iqbal MA, Saini SK, Tiku AB, Bamezai RNK. Pyruvate kinase M knockdown-induced signaling via AMP-activated protein kinase promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, autophagy, and cancer cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:15561–15576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.791343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng B, Liu F, Zeng L, Geng L, Ouyang X, Wang K, Huang Q. Overexpression of pyruvate kinase type M2 (PKM2) promotes ovarian cancer cell growth and survival via regulation of cell cycle progression related with upregulated CCND1 and downregulated CDKN1A expression. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:3103–3112. doi: 10.12659/MSM.907490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg MS, Sharp PA. Pyruvate kinase M2-specific siRNA induces apoptosis and tumor regression. J Exp Med. 2012;209:217–224. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spoden GA, Mazurek S, Morandell D, Bacher N, Ausserlechner MJ, Jansen-Dürr P, Eigenbrodt E, Zwerschke W. Isotype-specific inhibitors of the glycolytic key regulator pyruvate kinase subtype M2 moderately decelerate tumor cell proliferation. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:312–321. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spoden GA, Rostek U, Lechner S, Mitterberger M, Mazurek S, Zwerschke W. Pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2 is a glycolytic sensor differentially regulating cell proliferation, cell size and apoptotic cell death dependent on glucose supply. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:2765–2774. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo W, Zhang Y, Chen T, Wang Y, Xue J, Zhang Y, Xiao W, Mo X, Lu Y. Efficacy of RNAi targeting of pyruvate kinase M2 combined with cisplatin in a lung cancer model. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0860-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li RZ, Fan XX, Shi DF, Zhu GY, Wang YW, Luo LX, Pan HD, Yao XJ, Leung EL, Liu L. Identification of a new pyruvate kinase M2 isoform (PKM2) activator for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Chem Biol Drug Des. 2018;92:1851–1858. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu B, Yuan X, Xu B, Zhang H, Li R, Wang X, Ge Z, Li R. Synthesis of novel 7-azaindole derivatives containing pyridin-3-ylmethyl dithiocarbamate moiety as potent PKM2 activators and PKM2 nucleus translocation inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;170:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boxer MB, Jiang JK, Vander Heiden MG, Shen M, Skoumbourdis AP, Southall N, Veith H, Leister W, Austin CP, Park HW, et al. Evaluation of substituted N,N′-diarylsulfonamides as activators of the tumor cell specific M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase. J Med Chem. 2010;53:1048–1055. doi: 10.1021/jm901577g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo C, Linton A, Jalaie M, Kephart S, Ornelas M, Pairish M, Greasley S, Richardson P, Maegley K, Hickey M, et al. Discovery of 2-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)methyl)-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones as novel PKM2 activators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:3358–3363. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Li S, Guo J, Li Q, Long J, Ma C, Ding Y, Yan C, Li L, Wu Z, et al. Natural product micheliolide (MCL) irreversibly activates pyruvate kinase M2 and suppresses leukemia. J Med Chem. 2018;61:4155–4164. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang JK, Boxer MB, Vander Heiden MG, Shen M, Skoumbourdis AP, Southall N, Veith H, Leister W, Austin CP, Park HW, et al. Evaluation of thieno[3,2-b]pyrrole[3,2-d]pyridazinones as activators of the tumor cell specific M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:3387–3393. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsui Y, Yasumatsu I, Asahi T, Kitamura T, Kanai K, Ubukata O, Hayasaka H, Takaishi S, Hanzawa H, Katakura S. Discovery and structure-guided fragment-linking of 4-(2,3-dichlorobenzoyl)-1-methyl-pyrrole-2-carboxamide as a pyruvate kinase M2 activator. Bioorg Med Chem. 2017;25:3540–3546. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qi W, Keenan HA, Li Q, Ishikado A, Kannt A, Sadowski T, Yorek MA, Wu IH, Lockhart S, Coppey LJ, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 activation may protect against the progression of diabetic glomerular pathology and mitochondrial dysfunction. Nat Med. 2017;23:753–762. doi: 10.1038/nm.4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yacovan A, Ozeri R, Kehat T, Mirilashvili S, Sherman D, Aizikovich A, Shitrit A, Ben-Zeev E, Schutz N, Bohana-Kashtan O, et al. 1-(sulfonyl)-5-(arylsulfonyl)indoline as activators of the tumor cell specific M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:6460–6468. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen C, Xiao W, Huang L, Yu G, Ni J, Yang L, Wan R, Hu G. Shikonin induces apoptosis and necroptosis in pancreatic cancer via regulating the expression of RIP1/RIP3 and synergizes the activity of gemcitabine. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9:5507–5517. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin TJ, Lin HT, Chang WT, Mitapalli SP, Hsiao PW, Yin SY, Yang NS. Shikonin-enhanced cell immunogenicity of tumor vaccine is mediated by the differential effects of DAMP components. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:174. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0435-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Xie J, Jiang Z, Wang B, Wang Y, Hu X. Shikonin and its analogs inhibit cancer cell glycolysis by targeting tumor pyruvate kinase-M2. Oncogene. 2011;30:4297–4306. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao X, Zhu Y, Hu J, Jiang L, Li L, Jia S, Zen K. Shikonin inhibits tumor growth in mice by suppressing pyruvate kinase M2-mediated aerobic glycolysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:14517. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31615-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li W, Liu J, Zhao Y. PKM2 inhibitor shikonin suppresses TPA-induced mitochondrial malfunction and proliferation of skin epidermal JB6 cells. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53:403–412. doi: 10.1002/mc.21988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang JC, Zhao J, Long F, Chen JY, Mu B, Jiang Z, Ren Y, Yang J. Efficacy of Shikonin against esophageal cancer cells and its possible mechanisms in vitro and in vivo. J Cancer. 2018;9:32–40. doi: 10.7150/jca.21224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tao T, Su Q, Xu S, Deng J, Zhou S, Zhuang Y, Huang Y, He C, He S, Peng M, et al. Downr-egulation of PKM2 decreases FASN expression in bladder cancer cells through AKT/mTOR/SREBP-1c axis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:3088–3104. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boulos JC, Rahama M, Hegazy MF, Efferth T. Shikonin derivatives for cancer prevention and therapy. Cancer Lett. 2019;459:248–267. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ning X, Qi H, Li R, Jin Y, McNutt MA, Yin Y. Synthesis and antitumor activity of novel 2, 3-didithiocarbamate substituted naphthoquinones as inhibitors of pyruvate kinase M2 isoform. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2018;33:126–129. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2017.1404591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruiter R, Visser LE, van Herk-Sukel MP, Coebergh JW, Haak HR, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn PH, Straus SM, Herings RM, Stricker BH. Lower risk of cancer in patients on metformin in comparison with those on sulfonylurea derivatives: Results from a large population-based follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:119–124. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalva-Aydemir S, Bajpai R, Martinez M, Adekola KU, Kandela I, Wei C, Singhal S, Koblinski JE, Raje NS, Rosen ST, Shanmugam M. Targeting the metabolic plasticity of multiple myeloma with FDA-approved ritonavir and metformin. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1161–1171. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shang D, Wu J, Guo L, Xu Y, Liu L, Lu J. Metformin increases sensitivity of osteosarcoma stem cells to cisplatin by inhibiting expression of PKM2. Int J Oncol. 2017;50:1848–1856. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silvestri A, Palumbo F, Rasi I, Posca D, Pavlidou T, Paoluzi S, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. Metformin induces apoptosis and downregulates pyruvate kinase M2 in breast cancer cells only when grown in nutrient-poor conditions. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamabe A, Konno M, Tanuma N, Shima H, Tsunekuni K, Kawamoto K, Nishida N, Koseki J, Mimori K, Gotoh N, et al. Role of pyruvate kinase M2 in transcriptional regulation leading to epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:15526–15531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407717111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng K, Hao M. Metformin inhibits TGF-β1-induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal transition via PKM2 relative-mTOR/p70s6k signaling pathway in cervical carcinoma cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(pii):E2000. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Su Q, Tao T, Tang L, Deng J, Darko KO, Zhou S, Peng M, He S, Zeng Q, Chen AF, Yang X. Down-regulation of PKM2 enhances anticancer efficiency of THP on bladder cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:2774–2790. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hey E. Vitamin K-what, why, and when. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F80–F83. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.2.F80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ogawa M, Nakai S, Deguchi A, Nonomura T, Masaki T, Uchida N, Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S. Vitamins K2, K3 and K5 exert antitumor effects on established colorectal cancer in mice by inducing apoptotic death of tumor cells. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:323–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ivanova D, Zhelev Z, Getsov P, Nikolova B, Aoki I, Higashi T, Bakalova R. Vitamin K: Redox-modulation, prevention of mitochondrial dysfunction and anticancer effect. Redox Biol. 2018;16:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hitomi M, Nonomura T, Yokoyama F, Yoshiji H, Ogawa M, Nakai S, Deguchi A, Masaki T, Inoue H, Kimura Y, et al. In vitro and in vivo antitumor effects of vitamin K5 on hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:1337–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamada A, Osada S, Tanahashi T, Matsui S, Sasaki Y, Tanaka Y, Okumura N, Matsuhashi N, Takahashi T, Yamaguchi K, Yoshida K. Novel therapy for locally advanced triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2015;47:1266–1272. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osada S, Saji S, Osada K. Critical role of extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation on menadione (vitamin K3) induced growth inhibition. Cancer. 2001;91:1156–1165. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010315)91:6<1156::AID-CNCR1112>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lamson DW, Plaza SM. The anticancer effects of vitamin K. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:303–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonilla-Porras AR, Jimenez-Del-Rio M, Velez-Pardo C. Vitamin K3 and vitamin C alone or in combination induced apoptosis in leukemia cells by a similar oxidative stress signalling mechanism. Cancer Cell Int. 2011;11:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parekh HK, Mansuri-Torshizi H, Srivastava TS, Chitnis MP. Circumvention of adriamycin resistance: Effect of 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone (vitamin K3) on drug cytotoxicity in sensitive and MDR P388 leukemia cells. Cancer Lett. 1992;61:147–156. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(92)90173-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen J, Jiang Z, Wang B, Wang Y, Hu X. Vitamin K(3) and K(5) are inhibitors of tumor pyruvate kinase M2. Cancer Lett. 2012;316:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scicchitano BM, Sorrentino S, Proietti G, Lama G, Dobrowolny G, Catizone A, Binda E, Larocca LM, Sica G. Levetiracetam enhances the temozolomide effect on glioblastoma stem cell proliferation and apoptosis. Cancer Cell Int. 2018;18:136. doi: 10.1186/s12935-018-0626-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnson DR, O'Neill BP. Glioblastoma survival in the United States before and during the temozolomide era. J Neurooncol. 2012;107:359–364. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0749-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chu L, Wang A, Ni L, Yan X, Song Y, Zhao M, Sun K, Mu H, Liu S, Wu Z, Zhang C. Nose-to-brain delivery of temozolomide-loaded PLGA nanoparticles functionalized with anti-EPHA3 for glioblastoma targeting. Drug Deliv. 2018;25:1634–1641. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2018.1494226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park I, Mukherjee J, Ito M, Chaumeil MM, Jalbert LE, Gaensler K, Ronen SM, Nelson SJ, Pieper RO. Changes in pyruvate metabolism detected by magnetic resonance imaging are linked to DNA damage and serve as a sensor of temozolomide response in glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74:7115–7124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yuan S, Qiao T, Zhuang X, Chen W, Xing N, Zhang Q. Knockdown of the M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase (PKM2) with shRNA enhances the effect of docetaxel in human NSCLC cell lines in vitro. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:1312–1323. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.6.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheng C, Xie Z, Li Y, Wang J, Qin C, Zhang Y. PTBP1 knockdown overcomes the resistance to vincristine and oxaliplatin in drug-resistant colon cancer cells through regulation of glycolysis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taieb J, Pointet AL, Van Laethem JL, Laquente B, Pernot S, Lordick F, Reni M. What treatment in 2017 for inoperable pancreatic cancers? Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1473–1483. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun C, Ansari D, Andersson R, Wu DQ. Does gemcitabine-based combination therapy improve the prognosis of unresectable pancreatic cancer? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4944–4958. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i35.4944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tian S, Li P, Sheng S, Jin X. Upregulation of pyruvate kinase M2 expression by fatty acid synthase contributes to gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:2211–2217. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li C, Zhao Z, Zhou Z, Liu R. Linc-ROR confers gemcitabine resistance to pancreatic cancer cells via inducing autophagy and modulating the miR-124/PTBP1/PKM2 axis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78:1199–1207. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-3178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim DJ, Park YS, Kang MG, You YM, Jung Y, Koo H, Kim JA, Kim MJ, Hong SM, Lee KB, et al. Pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2 is a therapeutic target of gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2015;336:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Calabretta S, Bielli P, Passacantilli I, Pilozzi E, Fendrich V, Capurso G, Fave GD, Sette C. Modulation of PKM alternative splicing by PTBP1 promotes gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 2016;35:2031–2039. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dilruba S, Kalayda GV. Platinum-based drugs: Past, present and future. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:1103–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-2976-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Belanger F, Fortier E, Dubé M, Lemay JF, Buisson R, Masson JY, Elsherbiny A, Costantino S, Carmona E, Mes-Masson AM, et al. Replication protein A availability during DNA replication stress is a major determinant of cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2018;78:5561–5573. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang X, Zhang F, Wu XR. Inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 markedly reduces chemoresistance of advanced bladder cancer to cisplatin. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45983. doi: 10.1038/srep45983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Galanski M. Recent developments in the field of anticancer platinum complexes. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2006;1:285–295. doi: 10.2174/157489206777442287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Galluzzi L, Senovilla L, Vitale I, Michels J, Martins I, Kepp O, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene. 2012;31:1869–1883. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang Y, Hao F, Nan Y, Qu L, Na W, Jia C, Chen X. PKM2 inhibitor shikonin overcomes the cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer by inducing necroptosis. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14:1883–1891. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.27854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li W, Qiu Y, Hao J, Zhao C, Deng X, Shu G. Dauricine upregulates the chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells: Role of repressing glycolysis via miR-199a: HK2/PKM2 modulation. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;121:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miya T, Kobayashi K, Hino M, Ando M, Takeuchi S, Seike M, Kubota K, Gemma A, East Japan Chesters Group Efficacy of triple antiemetic therapy (palonosetron, dexamethasone, aprepitant) for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving carboplatin-based, moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Springerplus. 2016;5:2080. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3769-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sève P, Dumontet C. Chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:73–88. doi: 10.2174/1568011053352604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu Y, He C, Huang X. Metformin partially reverses the carboplatin-resistance in NSCLC by inhibiting glucose metabolism. Oncotarget. 2017;8:75206–75216. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Graham J, Mushin M, Kirkpatrick P. Oxaliplatin. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:11–12. doi: 10.1038/nrd1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hsu HH, Chen MC, Baskaran R, Lin YM, Day CH, Lin YJ, Tu CC, Vijaya Padma V, Kuo WW, Huang CY. Oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer cells is mediated via activation of ABCG2 to alleviate ER stress induced apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:5458–5467. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fang Z, Gong C, Yu S, Zhou W, Hassan W, Li H, Wang X, Hu Y, Gu K, Chen X, et al. NFYB-induced high expression of E2F1 contributes to oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer via the enhancement of CHK1 signaling. Cancer Lett. 2018;415:58–72. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lu WQ, Hu YY, Lin XP, Fan W. Knockdown of PKM2 and GLS1 expression can significantly reverse oxaliplatin-resistance in colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:44171–44185. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ginés A, Bystrup S, Ruiz de Porras V, Guardia C, Musulén E, Martínez-Cardús A, Manzano JL, Layos L, Abad A, Martínez-Balibrea E. PKM2 subcellular localization is involved in oxaliplatin resistance acquisition in HT29 human colorectal cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Russo A, Maiolino S, Pagliara V, Ungaro F, Tatangelo F, Leone A, Scalia G, Budillon A, Quaglia F, Russo G. Enhancement of 5-FU sensitivity by the proapoptotic rpL3 gene in p53 null colon cancer cells through combined polymer nanoparticles. Oncotarget. 2016;7:79670–79687. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.He J, Xie G, Tong J, Peng Y, Huang H, Li J, Wang N, Liang H. Overexpression of microRNA-122 re-sensitizes 5-FU-resistant colon cancer cells to 5-FU through the inhibition of PKM2 in vitro and in vivo. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;70:1343–1350. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hjerpe E, Egyhazi Brage S, Carlson J, Frostvik Stolt M, Schedvins K, Johansson H, Shoshan M, Avall-Lundqvist E. Metabolic markers GAPDH, PKM2, ATP5B and BEC-index in advanced serous ovarian cancer. BMC Clin Pathol. 2013;13:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6890-13-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pan C, Wang X, Shi K, Zheng Y, Li J, Chen Y, Jin L, Pan Z. MiR-122 reverses the doxorubicin-resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through regulating the tumor metabolism. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Han TD, Shang DH, Tian Y. Docetaxel enhances apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle arrest by suppressing mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in human renal clear cell carcinoma. Genet Mol Res. 2016:15. doi: 10.4238/gmr.15017321. doi: 10.4238/gmr.15017321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sim S, Bergh J, Hellström M, Hatschek T, Xie H. Pharmacogenetic impact of docetaxel on neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer patients. Pharmacogenomics. 2018;19:1259–1268. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2018-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.van Rossum AGJ, Kok M, van Werkhoven E, Opdam M, Mandjes IAM, van Leeuwen-Stok AE, van Tinteren H, Imholz ALT, Portielje JEA, Bos MMEM, et al. Adjuvant dose-dense doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide versus docetaxel-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide for high-risk breast cancer: First results of the randomised MATADOR trial (BOOG 2004-04) Eur J Cancer. 2018;102:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sharma P, López-Tarruella S, García-Saenz JA, Khan QJ, Gómez HL, Prat A, Moreno F, Jerez-Gilarranz Y, Barnadas A, Picornell AC, et al. Pathological response and survival in triple-negative breast cancer following neoadjuvant carboplatin plus docetaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5820–5829. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hata A, Katakami N, Shimokawa M, Mitsudomi T, Yamamoto N, Nakagawa K. Docetaxel Plus RAmucirumab with primary prophylactic pegylated Granulocyte-ColONy stimulating factor support for elderly patients with advanced Non-small-cell lung cancer: A multicenter prospective single arm phase II Trial: DRAGON study (WJOG9416L) Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19:e865–e869. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tanimura K, Uchino J, Tamiya N, Kaneko Y, Yamada T1, Yoshimura K, Takayama K. Treatment rationale and design of the RAMNITA study: A phase II study of the efficacy of docetaxel + ramucirumab for non-small cell lung cancer with brain metastasis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11084. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Milbar N, Kates M, Chappidi MR, Pederzoli F, Yoshida T, Sankin A, Pierorazio PM, Schoenberg MP, Bivalacqua TJ. Oncological outcomes of sequential intravesical gemcitabine and docetaxel in patients with Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer. 2017;3:293–303. doi: 10.3233/BLC-170126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mortimer J, Zonder HB, Pal SK. Lessons learned from the bevacizumab experience. Cancer Control. 2012;19:309–316. doi: 10.1177/107327481201900407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wong N, Ojo D, Yan J, Tang D. PKM2 contributes to cancer metabolism. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hsu MC, Hung WC. Pyruvate kinase M2 fuels multiple aspects of cancer cells: From cellular metabolism, transcriptional regulation to extracellular signaling. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:35. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0791-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Papadaki C, Sfakianaki M, Lagoudaki E, Giagkas G, Ioannidis G, Trypaki M, Tsakalaki E, Voutsina A, Koutsopoulos A, Mavroudis D, et al. PKM2 as a biomarker for chemosensitivity to front-line platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1757–1764. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.