Abstract

We investigate the influence of optical coherence tomography (OCT) system resolution on high-quality in vivo en face corneal endothelial cell images of the monkey eye, to allow for quantitative analysis of cell density. We vary the lateral resolution of the ultrahigh resolution (UHR) OCT system (centered at 850 nm) by using different objectives, and the axial resolution by windowing the source spectrum. By suppressing the motion of the animal, we are able to obtain a high-quality en face corneal endothelial cell map in vivo using UHR OCT for the first time with a lateral resolution of 3.1 µm. Increasing lateral resolution did not result in a better image quality but a smaller field of view (FOV), and the axial resolution had little impact on the visualization of corneal endothelial cells. Quantitative analysis of cell density was performed on in vivo en face OCT images of corneal endothelial cells, and the results are in agreement with previously reported data. Our study may offer a practical guideline for designing OCT systems that allow for in vivo corneal endothelial cell imaging with high quality.

1. Introduction

The cornea is the outermost, optically transparent window of the eye. Its innermost layer, the endothelium, consists of a monolayer of hexagonal cells, which plays a crucial role in the homeostasis of the cornea. Currently, the mainstay of treatment of corneal dysfunction leading to opacity still remains surgical treatment i.e. corneal transplantation, which is one of the most commonly performed allograft procedures worldwide e.g. almost 50000 corneal transplants are performed yearly in the United States of America [1]. Moreover, corneal endothelial dysfunction is one of the most common surgical indication for corneal transplantation, [2] and there is a rising trend towards selective endothelial replacement i.e. endothelial keratoplasty [3]. As such, there is an increasing clinical need for accurate assessment of corneal endothelial cells in vivo pre-operatively and after treatment or surgery.[4]

Corneal endothelial cells are currently evaluated clinically using imaging technologies such as specular microscopy (SM) and in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) [5–7]. These microscopy techniques allow visualization of corneal endothelial cells in vivo to examine the morphology and health of cells. Unfortunately, the field of view (FOV) of these microscopy techniques is limited both by confocal gating and the curvature of the cornea. Further, SM is most commonly used in clinical practice for epithelium and endothelium characterization, but not able to evaluate all layers of the cornea. IVCM, on the other hand, requires contact to the eye to achieve a high numerical aperture that allows to resolve single endothelial cells. It may lead to patient discomfort, alterations to the corneal surface, as well as increased risk of corneal infection and abrasion.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) allows for three-dimensional, in vivo imaging in a non-contact manner for anterior segment imaging with a spatial resolution down to sub-cellular level [8–16]. It offers deep signal penetration in the corenal tissue to enable visualization of all the layers simultaneously. The axial resolution of OCT is determined by the central wavelength and the bandwidth of the source, while its lateral resolution is mainly dependent on the imaging objective. Therefore, high-NA is not required in OCT unless very high lateral resolution is needed. Various types of OCT systems have been demonstrated for cross-sectional and en face corneal endothelial cell imaging, including spectral domain (SD) OCT [12,13,17], full-field (FF) OCT [9], and Gabor domain(GD) OCT [16]. The lateral resolutions of all the systems were reported to be around or below 2 µm in tissue, which resulted in a very limited FOV and depth of focus (DOF). Consequently, the systems were very sensitive to fast eye motion, and only FF OCT [9] and high-speed SD OCT [13] were able to show successful delineation of the corneal endothelial cells within a small FOV when imaged in vivo. To date, OCT has yet to successfully visualize corneal endothelial cells in vivo in the en face plane to allow for quantitative analysis [18]. More importantly, the spatial resolution required for in vivo OCT imaging of corneal endothelial cells in the en face plane is still unclear.

In this paper, we investigated the OCT spatial resolutions required for visualization of the corneal endothelium in vivo in the en face plane A custom-built UHR SDOCT system at 850 nm was adopted in this study. We varied its lateral resolution by using different objectives, and the axial resolution by windowing the source spectrum. Hexagonal grids were employed for quantitatively studying the impact of lateral resolution on the visualization of structures similar to corneal endothelial cells. We investigated different lateral resolutions for the imaging of the monkey cornea in order to identify the optimal resolution required for good visualization of the endothelial layer and successfully obtained the first in vivo large FOV endothelial cell enface maps that were almost free of motion artifacts. The ex vivo endothelial cell maps for the same eye were provided for comparison. By varying the axial resolution by source windowing, we showed that reducing axial resolution did not affect corneal endothelial cell visualization. Finally, cell density quantification was conducted on the endothelial cell maps and was shown to be in agreement with the results of the manual counting as well as literature reported values for the imaged animal. Our study provides a practical guideline for clinical corneal endothelium studies using OCT.

2. Methods

2.1. UHR-OCT system

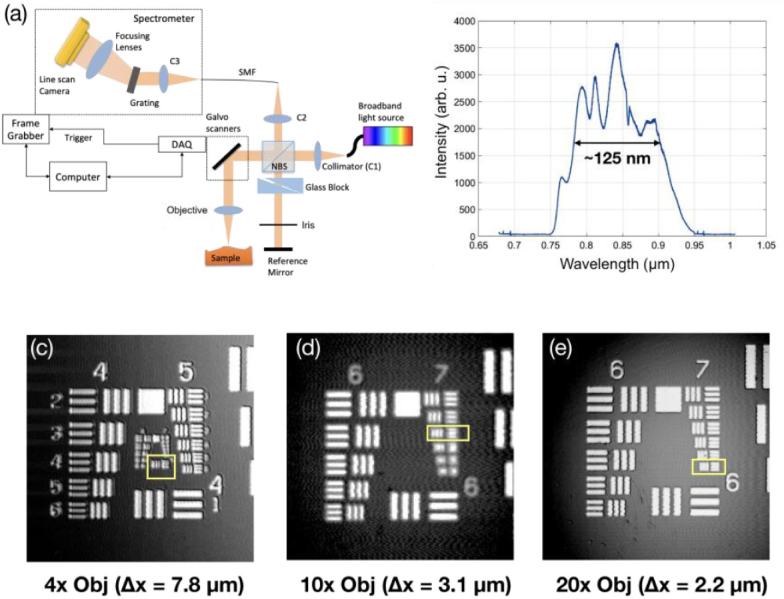

Figure 1(a) shows the schematic of the custom-built UHR SD-OCT system [12]. Specifically, a superluminescence diode centered at 850 nm with a FWHM (Full Width Half Maximum) bandwidth of 165 nm (cBLMD-T-850-HP-I, Superlum, Republic of Ireland) was used as the light source. It was sent to a free-space Michelson interferometer, with one arm as the reference arm and the other as the sample arm. In the reference arm, a pair of prisms was inserted to match the dispersion caused by the optics in the sample arm, and an iris was used to adjust the reference power. A customized spectrometer was constructed to allow for an imaging range of 2.6 mm in air. It consisted of a collimator, a transmission grating (1200 lp/mm, Wasatch Photonics, Logan, UT, USA), a camera lens (f = 85mm, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany), and a CMOS line-scan camera (spL4096-140km, Basler AG, Ahrensburg, Germany). An in-house developed software (LabVIEW, National Instruments) was employed to control the image acquisition. The source spectrum acquired by the spectrometer is displayed in Fig. 1(b). The actual bandwidth of the source was read out as 125 nm, smaller than the nominal bandwidth mainly due to the modification by grating diffraction efficiency, camera spectral response, and degradation of the SLD over time. The sample arm delivered 1.5 mW to the sample, and the sensitivity of the system was measured to be 103 dB at 70kHz A-line rate.

Fig. 1.

(a) The schematic of the UHR SD-OCT system. (b) The source spectrum read from the spectrometer. (c) (d) (e) The 1951 USAF resolution target imaged with 4x, 10x, and 20x objectives, respectively. The lateral resolution for each objective is read out as the line width of the last resolvable group, which is 7.8 µm, 3.1 µm, and 2.2 µm for 4x, 10x, and 20x objective respectively.

The axial resolution was measured about 2.8 µm in air, agreed with the theoretical estimation of 2.5 µm according to the actual bandwidth. The lateral resolution of the system was varied by switching the objective of the sample arm. Three objectives, with a magnification of 4X (LSM03-BB, Thorlabs GmbH, Newton, USA), 10X (Mitutoyo), and 20X (Mitutoyo), respectively, were adopted, and the lateral resolution of the system with each objective was characterized by imaging the 1951 USAF resolution target. As shown in Fig. 1(c)–(e), the lateral resolution, determined by the line width of the last resolvable group (marked by yellow boxes), was measured to be 7.8 µm (group 6 element 1), 3.1 µm (group 7 element 3), and 2.2 µm (group 7 element 6) for the 4X, 10X, and 20X objective, respectively. The corresponding DOF of the objectives were calculated as 449.7 µm, 71.0 µm, and 35.5 µm for 4X, 10X, and 20X, respectively [19].

To understand the lateral resolution required to clearly delineate the corneal endothelial cell structure, we conducted OCT imaging at different lateral resolutions on an ideal hexagonal TEM grid (G1000HEXC, Ladd Research, Williston, VT, USA) with a pitch of 25 µm (hole width 19 µm, bar width 6 µm) comparable to the actual cell width. We identified the objectives that may offer the sufficient lateral resolution for imaging corneal endothelial cell, and evaluated their performance in both in vivo and ex vivo OCT imaging.

2.2. Animal preparation and imaging protocol

The study included one adult cynomolgus macaque monkey (Macaca fascicularis) with an age ranging from four to six years and a weight of 5.79 kg. All animal procedures conformed to the adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the SingHealth standard for responsible use of animals in research, from whom ethical approval was obtained (approval number 2017/SHS/1331). All the procedures were carried out in the SingHealth Experimental Medicine Centre, which is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC).

The animal used in this study was socially housed in groups of 3-5 animals. Animals were housed in cages measuring 1.22m L × 1.83m D × 1.83m HT. The temperature of the housing room was maintained at 25–27°C and the relative humidity was 45∼55%. Regular changes of equipment and toys were provided. Foods was provided two times a day and water was available ad libitum. Before recruiting into the experimental study, cynomolgus monkeys were given comprehensive ocular examination, including anterior segment and fundus examination, to exclude any ocular disease.

Each OCT volume consisted of 600-by-600 pixels laterally and 2048 pixels axially. The lateral field of view (FOV) was adjustable and varied for different objectives. The A-line speed was set at 70 kHz for both ex vivo and in vivo OCT imaging, taking about 5 seconds to complete one volumetric scan. In vivo imaging of corneal endothelial cells was performed on one eye (randomly chosen) while the monkey was anesthetized. For OCT imaging, the monkey was positioned in the adjustable platform and its head secured to the OCT apparatus using parafilm strips to avoid large motion. Saline drops were applied in between the scans to keep the cornea moisturized. The focused endothelium was brought close to the DC term in the B-scans, with the full cornea flipped (the endothelium on top of the epithelium). Several volumes were taken with ± 50 µm offsets after placing the central corneal endothelium in focus. This was to ensure at least one of the volumes delivered the best on-focus en face image of the corneal endothelium.

Afterwards, the same eye was imaged by IVCM (HRT3 Rostock module; Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). The monkey was then sacrificed, and the eye was procured immediately to perform ex vivo OCT imaging at the same location within 2 hours.

After completing all the imaging procedures, the eye was fixed in formalin and sent for histology process. Specimen blocks were embedded and excised along the OCT B-scan direction. Multiple 5 µm-thick slices were taken from the specimen block and stained with Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stain. The processed slides were imaged with (Nikon Inverted Microscope Eclipse Ti-E, Tokyo, Japan) digitalized at 40x magnification.

2.3. Post processing and data analysis

2.3.1. OCT signal processing

The OCT cross sectional scans (B-scans) were generated following standard OCT post-processing steps, including spectral shaping, linear-k interpolation, dispersion compensation, and inverse Fourier transform in MATLAB (MathWorks). The B-scans were registered to eliminate motion artifact using Amira (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Next, the processed B-scans were thresholded to include only the high-SNR pixels. As the endothelial layer is the top surface in the image, it is determined by finding the first pixel along each A-line in the thresholded B-scans. A second-order polynomial fitting was applied to represent the smoothed boundary marking the endothelium. The entire A-lines were shifted, so that the edge pixels were brought to the same height of the image to generate the flattened endothelium. The corneal endothelial cell maps were generated by the maximum projection (MP) of the entire endothelial layer stack onto the en face plane, after surface flattening was performed for each B-scan of the volume.

To study the effect of varying axial resolution in the OCT B-scans, a narrow Hann window was multiplied to the original spectrum before Fourier transform. In this study, the original bandwidth of the source was reduced to its half (63 nm) and quarter (32 nm), to generate B-scans with an axial resolution of 5.4 µm and 10.8 µm, respectively.

2.3.2. Cell density analysis

For ideal hexagonal grids with side-to-side cell width (pitch) of a, the single cell area is known as The cell density is defined as the inverse of the cell area as [20]. To measure the side-to-side cell width from the grid map, one common practice is to compute the two-dimensional (2D) fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the grid map, resulting in another hexagonal pattern where the characteristic frequency can be written as

| (1) |

Therefore, the cell density expressed in terms of is .

Similarly, for corneal endothelial cells, the cell density can be estimated as

| (2) |

where is a factor determined by both cell shape and pattern regularity. In general, is assumed as 1, for the reason that the corneal endothelial cells are usually arranged in an irregular-shaped hexagonal pattern.

In this study, 2D FFT was performed on the 600-by-600 pixel en face maps zero-padded to 1024-by-1024 points. The magnitude of the spatial frequency spectra was used for quantitative analysis of cell density. For ideal hexagonal grid images, the characteristic frequency was directly located in the spatial frequency map as the nearest peaks around the DC term. For corneal endothelial cell maps, the spatial frequency maps were resampled to polar coordinates, generating a series of radial frequency spectra, and then averaged to form a mean radial frequency spectrum. The characteristic frequency was identified as the location of the secondary peak next to the main peak at DC in the radial frequency spectrum. The manual cell counting was conducted by a trained grader (A.K.). The cells were counted in areas where cells could be clearly distinguished visually. This is similar to the sampling performed in clinical corneal endothelial cell counting on platforms such as a specular microscope.

3. Results

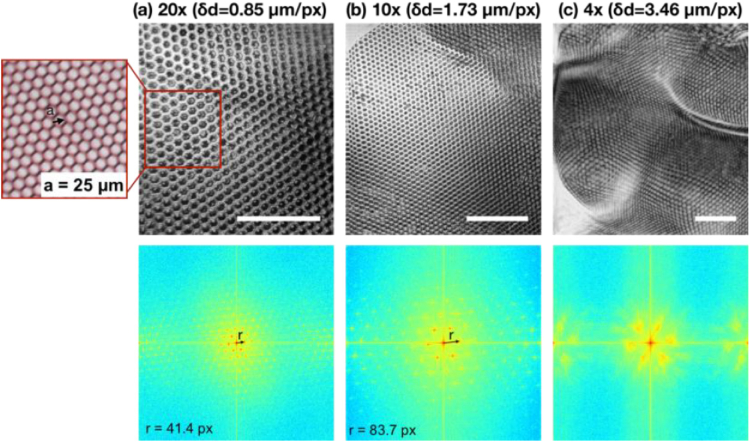

3.1. Hexagonal grid imaging

Figure 2 summarizes the results: the top row shows the en face OCT images of the grid taken with 20X, 10X, and 4X objectives, respectively; The bottom row shows the corresponding 2D FFT maps with normalized magnitude. By visual inspection, it is not difficult to observe that the individual grid cells are well delineated in the en face images generated with 10X and 20X objectives, while it fails for the 4X objective. This observation was confirmed quantitatively by analyzing the power spectrum map after 2D FFT. In Fig. 2(a) and (b), the power spectra manifested a periodic, hexagonal pattern, implying that the ideal hexagonal cell map was faithfully portrayed by OCT. Conversely, the power spectrum shown in Fig. 2(c) lacks the periodicity, indicating the hexagonal pattern was not delineated in the corresponding OCT en face image.

Fig. 2.

En face OCT images as well as its corresponding spatial frequency spectra of the hexagonal grid taken with (a) 20X, (b) 10X, and (c) 4X objectives, respectively. The spatial sampling interval was 0.85 µm, 1.73 µm, and 3.46 µm for 20X, 10X, and 4X objectives, respectively. The characteristic frequency, marked by “r”, was measured to be 42.4/1024 px−1 and 83.7/1024 px−1 for 20X and 10X maps, respectively. The 4X objective failed to resolve the periodic grid patterns and therefore the characteristic frequency was not given here. Inset: white light camera image of the hexagonal grid. Scale bar: 200 µm.

For the 20X objective (lateral resolution 2.2 µm), the spatial sampling density was 0.85 µm/pixel. The characteristic spatial frequency, shown as six red dots around the center on the 2D FFT maps and marked by the black arrow in Fig. 2, was measured to be 0.0476 µm−1 and, based on Eq. (1), resulted in a cell width of 24.3 µm. Similarly, the characteristic spatial frequency was measured to be 0.0472 µm−1 for the 10X objective, and the corresponding cell width was computed to be 24.4 µm. The measurements were slightly smaller than the true value of 25 µm, mainly because the grid was curved and the cells at the lower part of the images were bent and appeared narrower.

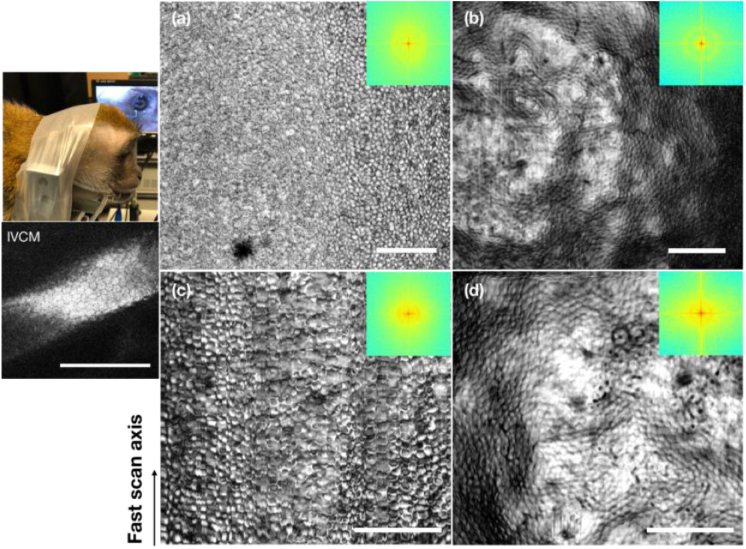

3.2. In vivo corneal endothelial cell imaging in monkeys with different lateral resolutions

Given the above results, 10X and 20X objectives were used for corneal endothelial cell imaging in monkeys. Figure 3 shows the imaging results using the 10X objective. Specifically, the en face corneal endothelial cell maps acquired with a large FOV of 1.037 mm by 1.037 mm are shown in Fig. 3(a) and (b) from in vivo and ex vivo imaging, respectively. The spatial frequency spectra in the insets manifested a faint concentric ring in both images, similar to what has been reported in previous studies [20–23]. It implies that the cells were readily visible in both in vivo and ex vivo en face cell maps. However, the ring was less salient in the in vivo map, suggesting lower clarity of cells when imaged in vivo. Indeed, the cell shape appeared more distorted in the in vivo map. This was mainly due to the presence of motion: lateral motion will deteriorate the cell shape along the slow scan axis, and axial motion will lead to the defocusing (blurring) effect. It should be noted that the lateral motion was reduced and can be almost eliminated by frame registration via post-processing using the animal management setup shown in the camera photo in Fig. 3. We were also able to constrain the axial motion down to around 100 µm displacement. Still, it was larger than the DOF of the 10X objective, and the corneal curvature was prominent for a wide FOV. Therefore, distortion and defocusing cannot be avoided. As a comparison, the en face corneal endothelial cell maps acquired with a relatively smaller FOV of 0.691 mm by 0.691 mm are shown in Fig. 3(c) and (d). With a finer spatial sampling interval of 1.15 µm/pixel, it is obvious that the cells were better delineated in vivo compared with Fig. 3(a). The ring in its spatial frequency map was also more prominent compared with the above case, suggesting a higher contrast in the cells in this image. The detailed quantification is presented and discussed in Section 3.4. One might also notice that the appearances of the endothelial cell body were different (dark or bright) between the IVCM and OCT images. The difference in the colors of the cell body was also seen in other literatures [17]. We suspect it was due to the location of the focal plane as well as the incident angle with respect to the endothelial cell layer, and/or the endothelial cell layer morphology.

Fig. 3.

Monkey corneal endothelial cell maps acquired using the 10X objective (a) (c) in vivo and (b) (d) ex vivo. (a) (b) FOV: 1.037 mm by 1.037 mm. (c) (d) FOV: 0.691 mm by 0.691 mm. Left top: animal management for in vivo imaging. Left bottom: the IVCM image of the same eye. Arrow: fast scan direction. Insets: spatial frequency spectra of the corresponding en face cell maps. Scale bar: 200 µm.

Figure 4 shows the imaging results using the 20X objective. The in vivo cell map in Fig. 4(a) had a FOV of 0.343 mm by 0.343 mm with a sampling rate of 0.57 µm/px, while the ex vivo map in Fig. 4(b) had a larger FOV of 0.510 mm by 0.510 mm with a sampling rate of 0.85 µm/px. Individual cells were clearly visible in both in vivo and ex vivo images. Yet, during in vivo imaging, the motion artifact along the slow scan axis was much more pronounced compared with that taken with 10X objective at a lower resolution. The spatial frequency analysis also suggested that it failed to capture the detailed cell structures by using the 20X objective in vivo. From the ex vivo image, one may also notice that the peripheral area at the bottom right has little contrast and seems out of focus, despite of a small FOV. This was due to the disadvantage of a smaller DOF (half of the DOF of 10X objective) associated with the higher resolution offered by the 20X objective.

Fig. 4.

Monkey corneal endothelial cell maps acquired using the 20X objective (a) in vivo and (b) ex vivo, with a FOV of 0.343 mm by 0.343 mm and 0.510 mm by 0.510 mm, respectively. Insets: spatial frequency spectra of the corresponding en face cell maps. Scale bar: 200 µm.

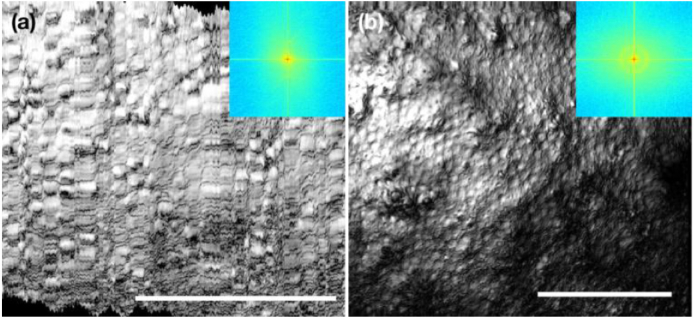

3.3. The impact of axial resolution on corneal endothelial cell visualization

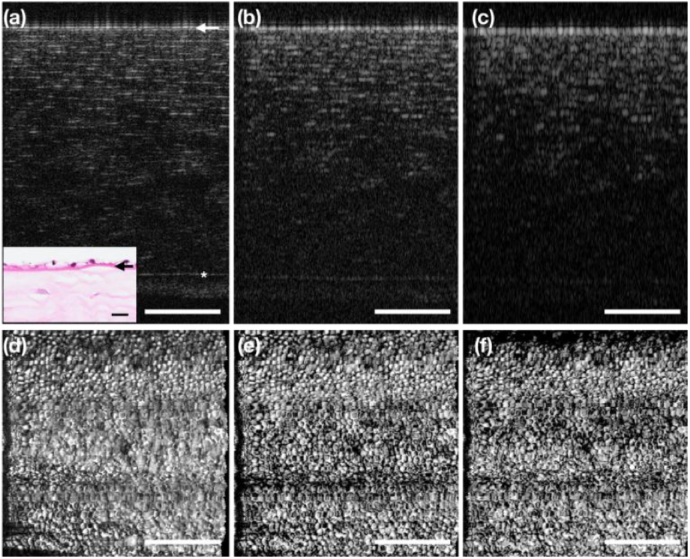

To vary the axial resolution of the OCT images, we used a Hann window to taper the source spectrum. The typical UHR OCT B-scan of the cornea with the corneal endothelium on top is presented in Fig. 5(a), with the corresponding histology focused on the endothelial layer as inset. The endothelial cells resided right on top of the Descemet’s membrane, which was marked by the white arrow. At the original axial resolution (around 2 µm in tissue), each layer of the cornea was well delineated. With the focal plane set on the endothelial layer, the other anterior layers were located out of DOF, possessing less contrast, and the lateral resolution can be no longer maintained. The corresponding en face endothelial cell map was presented in Fig. 5(d) as a reference. When the axial resolution of the B-scans was reduced to 4 µm in tissue, the anterior layers with less contrast were hardly visible in Fig. 5(b). However, the en face corneal endothelial cell map remained intact, as shown in Fig. 5(e). When the axial resolution was further reduced to 8 µm in tissue, the original details in the B-scan were almost washed away, and yet the endothelial cell map remained sharp as in Fig. 5(d) and (e). In fact, with the contrast of the other layers diminished, the maximum projection resulted in a better contrast of the en face image at the corneal endothelial layer.

Fig. 5.

The impact of OCT axial resolution on en face visualization of corneal endothelial cell map. (a) Representative OCT B-scan of the Monkey cornea with the original axial resolution (∼ 2 µm in tissue). (b) The same B-scan with the axial resolution reduced by half (∼4 µm in tissue) and (c) quarter (∼ 8 µm in tissue). (d)–(f) The en face corneal endothelial cell images generated from the MP of the endothelial layer stacks of the respective volumes with different axial resolutions. Inset: histology slide of the cornea. The star (*) indicates the Bowman’s layer, and the arrow indicates the Descemet’s membrane. Scale bar: 200 µm

3.4. Quantification of corneal cell density

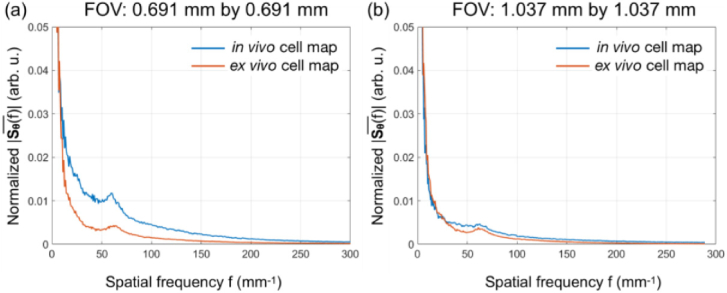

We quantitatively assessed the OCT image quality from the 10X objective by comparing the cell density obtained via spatial frequency analysis and manual counting. The averaged radial spatial frequency spectra in Fig. 6(a) and (b) were obtained from the spatial frequency spectra presented in the insets of Fig. 3(a) and (b). As shown in Fig. 6(a), the characteristic frequency was salient in both in vivo and ex vivo cases for a FOV of 0.691 mm by 0.691 mm, located at 60.3 mm−1 and 61.9 mm−1, for in vivo and ex vivo corneal endothelial cell maps, respectively. Using Eq. (2), the in vivo cell density was calculated to be 3636 cells/mm, which was in accordance with the manual counting result showing a mean cell density of 3783 cells/mm. It was also very close to the ex vivo cell density of 3831 cells/mm. For the same cornea, when imaging with a larger FOV (1.037 mm by 1.037 mm) and lower spatial sampling density, the cell visibility reduced and there was a greater chance of capturing cells located out of the DOF. Hence, the strength of the peak was reduced, as shown in Fig. 6(b). The resultant cell density was calculated to be 3869 cells/mm and 3721 cells/mm for in vivo and ex vivo cell maps, respectively, similar to what we got from the smaller FOV. Generally, the ex vivo images had more area with reduced visibility due to signal saturation on the endothelium (seen in Fig. 3(b) and (d)), resulting in a less salient peak at the characteristic frequency. All the calculated results were in agreement with previously reported corneal endothelial cell densities in Macaque monkeys [24], supporting the excellent quality of the OCT en face images and demonstrating their utility for in vivo assessment of corneal endothelial cells.

Fig. 6.

The averaged radial power spectra reconstructed from the 2D FFT maps for in vivo and ex vivo corneal endothelial cell maps with FOV of (a) 0.691 mm by 0.691 mm and (b) 1.037 mm by 1.037 mm). In (a), salient peaks were observed at f = 60.3 mm−1 and 61.9 mm−1 for in vivo and ex vivo images, respectively. In (b), less salient peaks were observed at f = 62.2 mm−1 and 61.0 mm−1 for in vivo and ex vivo images, respectively.

4. Discussion and conclusion

We demonstrated in vivo corneal endothelial cell imaging with good contrast and high clarity in a monkey eyes using OCT. This is, to our best knowledge, the first in vivo OCT corneal endothelial cell en face map with a FOV of 0.691 mm by 0.691 mm (larger than that of the FF OCT). In vivo acquisition of on-focus OCT en face image of corneal endothelial cells remains challenging, due to the small DOF coming along with the high NA required for visualization of single cells and making the measurement very prone to any sample movement. In our study, eye and head movements in both lateral and axial direction were minimized by different measures including the use of a headrest and additionally fixating the head using parafilm strips, allowing to position the cornea in a range close to the focus depth. The focus adjustment was equally critical especially for the curved cornea with the presence of motion. Several volumes were taken with ± 50 µm axial offsets after placing the central corneal endothelium in focus. This was to ensure at least one of the volumes delivered the best on-focus en face image of the corneal endothelium.

From the hexagonal grid (pitch size 25 µm) imaging results, we concluded both 20X and 10X objectives in our system offered sufficient lateral resolution (corresponding to system resolutions of 2.2 µm and 3.1 µm respectively) to delineate the corneal endothelial cells. While cell boundaries would be more defined when imaging with higher resolution, there are a few drawbacks associated with using a higher lateral resolution, such as a smaller DOF and restricted FOV ultimately limiting its utility for corneal endothelial cell imaging. Specifically, in our study, the lateral resolution of the 20X objective was 0.7 times finer than that of the 10X objective, at a cost of the reduction of both FOV and DOF to half of the 10X objective. Moreover, with higher resolution, the motion artifact along the slow scan axis led to a deterioration of the image quality. Hence we believe it is necessary to choose the appropriate lateral resolution to balance all requirements for corneal endothelial cell imaging rather than just the highest lateral resolution available. During in vivo corneal endothelial cell imaging, the best en face cell image was obtained using a combination of the 10X objective (lateral resolution of 3.1 µm) and a FOV of 0.691 mm by 0.691 mm. When increasing the FOV to 1.037 mm by 1.037 mm, the cornea curvature became prominent and more cells were out of focus. Therefore, the overall image quality was compromised. To improve the OCT image quality of large-FOV en face corneal endothelial cell images and the robustness of focusing adjustment, one may consider numerical refocusing techniques such as digital adaptive optics [25], which were not covered in this study. On the other hand, the axial resolution of the OCT system showed less impact on the visualization of the en face corneal endothelial cell image. Our results suggested that, while the ultra-high axial resolution was vital for delineation of individual corneal layers, it was not necessary for visualization of the corneal endothelial cells in a normal cornea. Because the corneal endothelium is a mono-layer structure sitting beneath the Descemet’s membrane, its enface morphometry can be visualized without fine axial sectioning as long as it is within the DOF and the lateral resolution as well as spatial sampling is sufficient, similar to what IVCM ultimately offers.

Our study was also confronted with some limitations. First, we only performed the in vivo imaging on one monkey, which was constrained by the availability of this research resources. Second, the OCT A-line speed was 70 kHz and the B-scan rate was 117 Hz. While it seemed to be sufficient for in vivo monkey imaging with motion management, it was too slow for human corneal imaging, given that the physical motion management measures are not readily applied to humans. For human corneal endothelial cell imaging using conventional raster-scanning OCT, the highest frame rate up to date was 500 Hz [13], and that still it was not possible to visualize a large area of human corneal endothelial cells in vivo. Therefore, an even higher OCT frame rate will be needed to fulfill this purpose. Since the axial resolution is not crucial for corneal endothelial cell imaging, it is also possible to employ the high-speed SS OCT with multiple MHz A-line rate at 1060 nm [26] and even 19 MHz at 1500 nm [27].

In conclusion, we performed a quantitative study to evaluate the optimal spatial resolution of OCT required for acquiring high-quality corneal endothelial cell images in vivo. We found that the requirement on the lateral resolution was very crucial whereas the axial resolution was not. By controlling the motion of the animal, clear corneal cellular maps can be obtained at a lateral resolution of 3.1 µm. Further improvement of the lateral resolution did not result in a better image quality. The axial resolution did not have much impact on the visualization of corneal endothelial cells. Quantitative analysis of corneal cell density was performed on in vivo en face OCT images of corneal endothelial cells, and the results were in agreement with previously reported data. Our study may offer a practical guideline for designing OCT systems that allow for in vivo corneal endothelial cell imaging with high quality.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Ms. Candice Ho for helping with the histology procedure, Mr. Shahrill Mohamed for animal management, and Mr. Yijie Ho for processing volumes in Amira. The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Funding

National Medical Research Council10.13039/501100001349 (CG.C010A.2017); National University of Singapore10.13039/501100001352 (Duke-Duke NUS. RECA(Pilot). 2017. 0036).

Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this article.

References

- 1.Park C. Y., Lee J. K., Gore P. K., Lim C.-Y., Chuck R. S., “Keratoplasty in the United States: a 10-year review from 2005 through 2014,” Ophthalmology 122(12), 2432–2442 (2015). 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woo J. H., Ang M., Htoon H. M., Tan D. T., “Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty versus descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty,” Am. J. Ophthalmol. 207, 288–303 (2019). 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang M., Wilkins M. R., Mehta J. S., Tan D., “Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty,” Br. J. Ophthalmol. 100(1), 15–21 (2016). 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ang M., Mehta J. S., Lim F., Bose S., Htoon H. M., Tan D., “Endothelial cell loss and graft survival after Descemet's stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty,” Ophthalmology 119(11), 2239–2244 (2012). 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourne W. M., Kaufman H. E., “Specular microscopy of human corneal endothelium in vivo,” Am. J. Ophthalmol. 81(3), 319–323 (1976). 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90247-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villani E., Baudouin C., Efron N., Hamrah P., Kojima T., Patel S. V., Pflugfelder S. C., Zhivov A., Dogru M., “In vivo confocal microscopy of the ocular surface: from bench to bedside,” Curr. Eye Res. 39(3), 213–231 (2014). 10.3109/02713683.2013.842592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhivov A., Stachs O., Stave J., Guthoff R. F., “In vivo three-dimensional confocal laser scanning microscopy of corneal surface and epithelium,” Br. J. Ophthalmol. 93(5), 667–672 (2009). 10.1136/bjo.2008.137430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drexler W., Fujimoto J. G., Optical Coherence Tomography: Technology and Applications (Springer Science & Business Media, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazlin V., Xiao P., Dalimier E., Grieve K., Irsch K., Sahel J.-A., Fink M., Boccara A. C., “In vivo high resolution human corneal imaging using full-field optical coherence tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9(2), 557–568 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.000557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bizheva K., Tan B., MacLelan B., Kralj O., Hajialamdari M., Hileeto D., Sorbara L., “Sub-micrometer axial resolution OCT for in-vivo imaging of the cellular structure of healthy and keratoconic human corneas,” Biomed. Opt. Express 8(2), 800–812 (2017). 10.1364/BOE.8.000800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.dos Santos V. A., Schmetterer L., Groschl M., Garhofer G., Schmidl D., Kucera M., Unterhuber A., Hermand J.-P., Werkmeister R. M., “In vivo tear film thickness measurement and tear film dynamics visualization using spectral domain optical coherence tomography,” Opt. Express 23(16), 21043–21063 (2015). 10.1364/OE.23.021043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werkmeister R. M., Sapeta S., Schmidl D., Garhofer G., Schmidinger G., Aranha dos Santos V., Aschinger G. C., Baumgartner I., Pircher N., Schwarzhans F., Pantalon A., Dua H., Schmetterer L., “Ultrahigh-resolution OCT imaging of the human cornea,” Biomed. Opt. Express 8(2), 1221–1239 (2017). 10.1364/BOE.8.001221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan B., Hosseinaee Z., Han L., Kralj O., Sorbara L., Bizheva K., “250 kHz, 1.5 µm resolution SD-OCT for in-vivo cellular imaging of the human cornea,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9(12), 6569–6583 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.006569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pantalon A., Pfister M., Aranha dos Santos V., Sapeta S., Unterhuber A., Pircher N., Schmidinger G., Garhofer G., Schmidl D., Schmetterer L., “Ultrahigh-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography for analysis of corneal microarchitecture during wound healing,” Acta Ophthalmol. 97(5), e761–e771 (2019). 10.1111/aos.14053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bizheva K., Tan B., MacLellan B., Hosseinaee Z., Mason E., Hileeto D., Sorbara L., “In-vivo imaging of the palisades of Vogt and the limbal crypts with sub-micrometer axial resolution optical coherence tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 8(9), 4141–4151 (2017). 10.1364/BOE.8.004141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tankam P., He Z., Thuret G., Hindman H. B., Canavesi C., Escudero J. C., Lépine T., Gain P., Rolland J. P., Capabilities of Gabor-Domain Optical Coherence Microscopy for the Assessment of Corneal Disease (SPIE, 2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ang M., Konstantopoulos A., Goh G., Htoon H. M., Seah X., Lwin N. C., Liu X., Chen S., Liu L., Mehta J. S., “Evaluation of a micro-optical coherence tomography for the corneal endothelium in an animal model,” Sci. Rep. 6(1), 29769 (2016). 10.1038/srep29769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ang M., Baskaran M., Werkmeister R. M., Chua J., Schmidl D., dos Santos V. A., Garhoefer G., Mehta J. S., Schmetterer L., “Anterior segment optical coherence tomography,” Prog. Retinal Eye Res. 66, 132–156 (2018). 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pircher M., Zawadzki R. J., “Review of adaptive optics OCT (AO-OCT): principles and applications for retinal imaging [Invited],” Biomed. Opt. Express 8(5), 2536–2562 (2017). 10.1364/BOE.8.002536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selig B., Vermeer K. A., Rieger B., Hillenaar T., Luengo Hendriks C. L., “Fully automatic evaluation of the corneal endothelium from in vivo confocal microscopy,” BMC Med. Imaging 15(1), 13 (2015). 10.1186/s12880-015-0054-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzke F. W., Masters B. R., Buckley R. J., Speedwell L., “Fourier transform analysis of human corneal endothelial specular photomicrographs,” Exp. Eye Res. 65(2), 205–214 (1997). 10.1006/exer.1997.0326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foracchia M., Ruggeri A., “Automatic estimation of endothelium cell density in donor corneas by means of Fourier analysis,” Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 42(5), 725–731 (2004). 10.1007/BF02347557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruggeri A., Grisan E., Jaroszewski J., “A new system for the automatic estimation of endothelial cell density in donor corneas,” Br. J. Ophthalmol. 89(3), 306–311 (2005). 10.1136/bjo.2004.051722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ollivier F., Brooks D., Komaromy A., Kallberg M., Andrew S., Sapp H., Sherwood M., Dawson W., “Corneal thickness and endothelial cell density measured by non-contact specular microscopy and pachymetry in Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) with laser-induced ocular hypertension,” Exp. Eye Res. 76(6), 671–677 (2003). 10.1016/S0014-4835(03)00055-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A., Drexler W., Leitgeb R. A., “Numerical focusing methods for full field OCT: a comparison based on a common signal model,” Opt. Express 22(13), 16061–16078 (2014). 10.1364/OE.22.016061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolb J. P., Draxinger W., Klee J., Pfeiffer T., Eibl M., Klein T., Wieser W., Huber R., “Live video rate volumetric OCT imaging of the retina with multi-MHz A-scan rates,” PLoS One 14(3), e0213144 (2019). 10.1371/journal.pone.0213144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tozburun S., Blatter C., Siddiqui M., Meijer E. F. J., Vakoc B. J., “Phase-stable Doppler OCT at 19 MHz using a stretched-pulse mode-locked laser,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9(3), 952–961 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.000952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]