Key Points

Question

Does training college (university) counseling center therapists in an evidence-based treatment (interpersonal psychotherapy) using the train-the-trainer method vs an expert training method result in improved fidelity (adherence and competence)?

Findings

In this cluster-randomized trial that included 184 therapists from 24 college counseling centers, results indicated within group improvements in both adherence and competence; only competence differed between groups, favoring the train-the-trainer condition.

Meaning

Results support the effectiveness of the train-the-trainer approach; further, given its potential capability to train more therapists over time, it has the potential to facilitate widespread dissemination of evidence-based treatments.

This cluster-randomized trial of 184 therapists at 24 college (university) counseling center therapists compares 2 methods of training to treat psychiatric disorders using interpersonal psychotherapy, a train-the-trainer model and a condition emphasizing expert advice.

Abstract

Importance

Progress has been made in establishing evidence-based treatments for psychiatric disorders, but these are not often delivered in routine settings. A scalable solution for training clinicians in evidence-based treatments is needed.

Objective

To compare 2 methods of training college (university) counseling center therapists to treat psychiatric disorders using interpersonal psychotherapy. The hypothesis was that the train-the-trainer condition would demonstrate superior implementation outcomes vs the expert condition. Moderating factors were also explored.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cluster-randomized trial was conducted from October 2012 to December 2017 in 24 college counseling centers across the United States. Therapist participants were recruited from enrolled centers, and student patients with symptoms of depression and eating disorders were recruited by therapists. Data were analyzed from 184 enrolled therapists.

Interventions

Counseling centers were randomized to the expert condition, which involved a workshop and 12 months of follow-up consultation, or the train-the-trainer condition, in which a staff member from the counseling center was coached to train other staff members.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was therapist fidelity (adherence and competence) to interpersonal psychotherapy, as assessed via audio recordings of therapy sessions. Therapist knowledge of interpersonal psychotherapy was a secondary outcome.

Result

A total of 184 therapists (mean [SD] age, 41.9 [10.6] years; 140 female [76.1%]; 142 white [77.2%]) were included. Both the train-the-trainer–condition and expert-condition groups showed significant within-group improvement for adherence to interpersonal psychotherapy (change: 0.233 [95% CI, 0.192-0.274] and 0.190 [0.145-0.235], respectively; both P < .001), with large effect sizes (1.64 [95% CI, 1.35-1.93] and 1.34 [95% CI, 1.02-1.66], respectively) and no significant difference between conditions. Both groups also showed significant within-group improvement in interpersonal therapy competence (change: 0.179 [95% CI, 0.132-0.226] and 0.106 [0.059-0.153], respectively; both P < .001), with a large effect size for the train-the-trainer condition (1.16 [95% CI, 0.85-1.46]; P < .001) and a significant difference between groups favoring the train-the-trainer condition (effect size, 0.47 [95% CI, 0.05-0.89]; P = .03). Knowledge of interpersonal psychotherapy improved significantly within both groups (effect sizes: train-the-trainer, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.28-0.99]; P = .005; expert, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.38-1.01]; P < .001), with no significant difference between groups. The significant moderating factors were job satisfaction for adherence (b, 0.120 [95% CI, 0.001-0.24]; P = .048) and competence (b, 0.133 [95% CI, 0.001-0.27]; P = .048), and frequency of clinical supervision for competence (b, 0.05 [95% CI, 0.004-0.09]; P = .03).

Conclusions and Relevance

Results demonstrate that the train-the-trainer model produced training outcomes comparable with the expert model for adherence and was superior on competence. Given its potential capability to train more therapists over time, it has the potential to facilitate widespread dissemination of evidence-based treatments.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02079142

Introduction

Remarkable progress has been made in establishing evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for psychiatric disorders. However, when individuals receive treatment in routine settings, it is typically not an EBT.1,2,3 As Insel noted, “We have powerful, evidence-based psychosocial interventions, but they are not widely available…A serious deficit exists in training.”4(p131) Standard approaches to training typically consist of provision of a manual and a workshop delivered by an expert.5 The influence of this approach on skills is short-lived if follow-up consultation does not occur.6,7,8,9 A practical, scalable, effective means of training therapists to implement EBTs is needed. One option for which there is a strong theoretical case10 for changing therapist behavior is the train-the-trainer approach,5 which centers around the development of a trainer who then trains therapists in the setting and serves as an internal coach. Although this approach has some evidence, past research has had limitations (eg, small samples, no comparison group, no assessment of implementation outcomes).11,12,13

In this study, we compared the implementation outcomes of 2 methods of training therapists to treat depression and eating disorders on college (university) campuses using interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). Counseling centers were chosen because they are staffed by therapists of various backgrounds in a manner similar to many community settings. The demand for treatment, also similar to community settings, often outweighs available resources, resulting in barriers to EBT implementation and little time for training. Moreover, this method meant that it was possible to recruit a sufficiently large sample of centers for a cluster-randomized design.

The 2 training methods were an external expert consultation model involving a workshop, manual, and 12 months of expert follow-up consultation (called the expert condition) and a train-the-trainer model in which a staff member from the counseling center was coached to train other staff members to implement IPT (called the trainer condition). Because a trainer is embedded in the site, therapists can continuously be trained over a prolonged period, providing sustainability of benefits, including potential cost-effectiveness, compared with the expert model. This model may also be a particularly good fit for college counseling centers, which typically have new trainees entering each year. The primary outcome was therapist fidelity to IPT assessed via audio recordings of therapy sessions, with assessments in 2 dimensions: adherence to the procedures of IPT and level of competence in applying these procedures. Changes in therapist knowledge of IPT were a secondary outcome.

We selected IPT, which is similar in structure to other EBTs, to disseminate because it is an EBT for 2 of the most common psychiatric disorders seen in college counseling centers, depression and eating disorders14,15,16,17,18; IPT is thus a transdiagnostic treatment, making it a so-called best-buy intervention.3 Treatments with a wide clinical range, such as IPT, may have increased therapist adoption.19 Interpersonal psychotherapy is also a particularly good match for young adults, because interpersonal issues are common.20,21,22,23

We hypothesized that the trainer condition would demonstrate superiority in these implementation outcomes compared with the expert condition. We also explored factors associated with and factors moderating the outcomes, including therapist-level and site-level characteristics.

Methods

Sample

Colleges

Colleges were eligible to participate if they had a counseling center, at least 3 interested therapists, and a staff member who consented to serve as the study director. This individual provided organizational-level data. Of the 24 consenting directors, 11 also participated as therapists, and 1 participated as a trainer in the trainer condition.

Therapists and Student Patients

Therapists were eligible if they treated students at the counseling center at least 25% of the time. Study staff obtained written consent from them, and they were enrolled between October 2012 and April 2014. Therapists were asked to obtain written informed consent from up to 2 student patients (eligible if they were 18 years or older and presenting with symptoms of depression and/or eating disorders [excluding anorexia nervosa, given that IPT is not an EBT for this diagnosis]). Therapists decided if the patients met these criteria using their clinical judgment or usual assessment procedures during each of the 2 study phases: baseline (ie, prior to training in IPT) and after training. Student data collection occurred from September 2014 to December 2017. At each site in the trainer condition, 1 trainer was selected by the study’s director at that center. Directors were informed that they should select someone with interest in the project, proficiency as a therapist and supervisor, and a stable position within the center. The study received institutional review board approval at the coordinating sites and each of the participating colleges.

Conditions

Expert Condition

We provided a 2-day workshop in IPT conducted by a study team member with expertise in IPT at each site randomized to the expert condition. Therapists were provided with a treatment manual, and the workshop involved a detailed review of key principles and procedures of IPT, using slides, plus role plays and case examples to demonstrate IPT treatment phases. Therapists at each site had the opportunity to engage in a 1-hour consultation call with the study team member who conducted the workshop every month for up to 12 months after the workshop to monitor treatment quality, provide feedback, and track patient progress.

Train-the-Trainer Condition

As a group, trainers attended 2 separate workshops at 1 of the study team sites; the first 2-day workshop was identical in content to the workshop provided in the expert condition and was designed to teach participants to conduct IPT. The second workshop provided training in training others in IPT.

After participation in the first workshop, each trainer returned to their site and was encouraged to treat up to 2 patients with IPT, audio-recording each session. The study team member who conducted the IPT training reviewed a selection of recorded sessions from each case treated by the trainers and provided feedback regarding treatment quality, which modeled for these individuals how to provide such feedback.

The goal of the second workshop was to prepare trainers to train others in IPT. Problem-solving was offered for potential barriers to conducting the training at their sites and providing ongoing consultation. Trainers were provided with video-recorded role plays demonstrating the treatment phases for use in conducting training, as well as standardized IPT checklists and forms designed to facilitate trainees’ use of IPT. This portion of the study, including the 2 workshops for the trainers and the trainer’s practice treating up to 2 patients and receiving feedback, spanned approximately 6 months. Once that phase was complete, trainers were encouraged to train therapists at their sites.

Once trainers had trained their colleagues in IPT, they were encouraged to meet weekly with their trainee colleagues for 1-hour group consultations to monitor treatment quality, provide feedback, and track patient progress. Trainers were also encouraged to join monthly group implementation review calls with the study team member who conducted their training and trainers from other sites.

Additional details of both conditions have been previously described.24 More details on the study methods are also available in the Trial Protocol in Supplement 1.

Measures

Three measures were used to assess training outcomes during each assessment interval (ie, baseline and posttraining implementation): therapist adherence to, competence in, and knowledge of IPT. The 2 dimensions of fidelity (adherence [the extent to which treatment is delivered as outlined] and competence [the skill with which the intervention is implemented])25 were assessed from audio recordings of therapy sessions by raters blind to the participant condition, using the IPT Fidelity Rating Scale, which was adapted (to assess both adherence and competence) from the measure developed for the Veterans Health Administration IPT Training Program, which was established through expert consensus.26 Items relevant to the IPT phase being delivered were scored as either 0 or 1 for adherence (absent or present), and for competence, the item was scored as 0 (unsatisfactory or incompetent; this grade was automatically given if the therapist was nonadherent), 1 (good enough or satisfactory), or 2 (at a high level of quality), with the means of ratings being calculated to generate overall scores. We note that it was not expected that therapists would use every technique in a single session. Raters also determined whether the session could be better characterized as cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, psychodynamic therapy, or motivational interviewing. Additional information is in the eAppendix in Supplement 2. Two audio recordings were rated for each patient from session 1 and a randomly chosen later session so that a selected sample of therapist behavior could be rated. Raters were a senior study team member and 5 graduate students and study staff members who were blinded to condition and study phase and who had received training in IPT. All raters received their training from the same study team member with expertise in IPT who had trained therapists in the expert condition and trainers in the trainer condition; in addition, the raters also received training from a senior study team member in rating audio recordings for IPT fidelity. This method of training raters and auditing audio recordings for fidelity to IPT has demonstrated validity and good reliability (ie, intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.78-0.96) in other clinical trials.27,28 Interrater reliability (2-way mixed-effects intraclass correlation), calculated from a subset of 9 audio recordings of posttraining tapes rated by multiple raters, was 0.72 (95% CI, 0.46-0.91), which is consistent with prior work.27,28 Knowledge of IPT was assessed from 20 multiple-choice questions developed for this study.

Therapist characteristics assessed at baseline included age, sex, race/ethnicity, degree, years employed in the present position, attendance at a prior IPT workshop or class (yes or no), experience using IPT with patients in the past year (yes or no), and job satisfaction. The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale29 total score was used to ascertain the individual’s degree of acceptance of EBTs. Finally, job satisfaction was assessed with the 14-item job-satisfaction scale, which demonstrates construct validity and acceptable internal consistency.30

Site-level assessments included information concerning the site director: age, experience, race/ethnicity, and degree, as well as the number of students at the site, therapist-to-student ratio, clinical supervision frequency (rated on a scale of 1 [indicating 0 times per week] to 7 [>2 times per week]), and 1 item assessing staff training and educational priorities (rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating not at all and 5 indicating a very great extent).

Statistical Analysis

After baseline assessment, 24 sites were randomly allocated to the 2 conditions by the data coordinating center using a computer program, matched on therapist-to-student ratio. Matching was achieved based on simple randomization. A power analysis was conducted based on the primary longitudinal analysis at the therapist level. With a medium effect size (Cohen d, 0.50), 112 therapists (56 per group) were needed to reach power of 0.80.

We used standard linear mixed effects modeling31,32 to estimate changes from baseline to posttraining assessments in primary and secondary outcomes. In line with the intention-to-treat principle, we included all randomized therapists in the analyses, as long as data were available from at least 1 of the repeated assessments. For all model estimations, we used maximum likelihood embedded in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén).33 Given the moderate sample size, standard errors were estimated using robust maximum likelihood, which is more robust to deviation from parametric assumptions. For the model specification, we used a random-intercept mode, assuming linear change over time. Finally, focusing on key outcomes of interest (adherence and competence), we examined potential moderators in the mixed-effects modeling framework, applying the analytical criteria for detecting moderators in line with the MacArthur approach.34,35 Effect sizes are reported as Cohen d, and other results are reported in the form of b, a nonstandardized coefficient from the regression of the slope on training condition (centered), baseline covariate (centered), and their interaction. The threshold of significance was P < .05, 2-sided.

Results

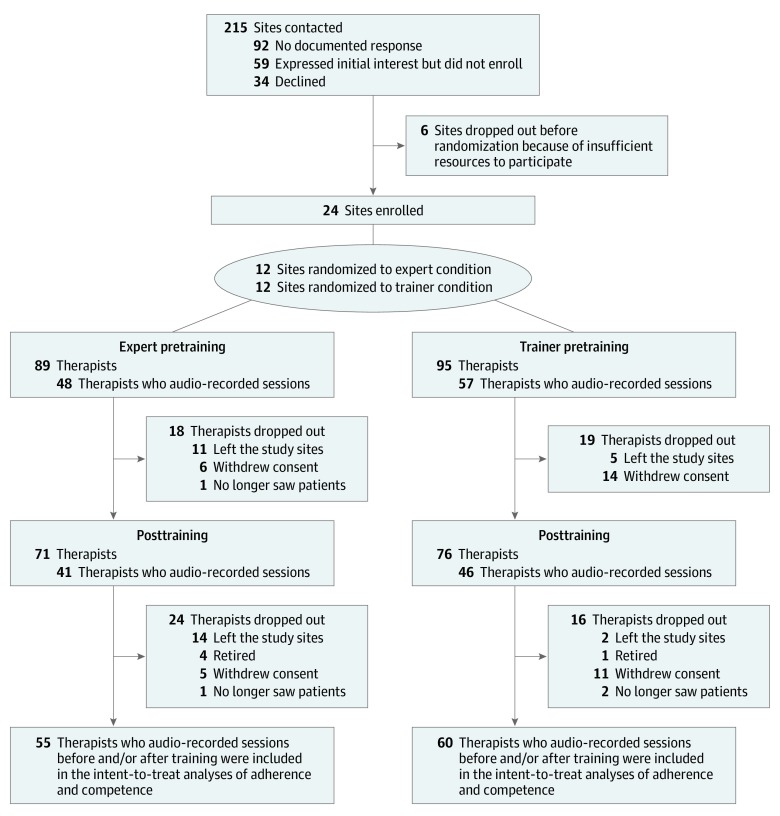

Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram. Among 215 college counseling sites that were contacted regarding the study, we had no documented response from 92 sites; 59 expressed initial interest but did not enroll; 34 declined; and 6 enrolled but dropped out before randomization, citing inadequate resources to continue. Hence, 24 sites were randomized with the therapist-to-student ratio for each institution taken into account. From those sites, 184 therapists were enrolled, with 89 allocated to the expert condition and 95 to the trainer condition. During the pretraining period, 105 therapists audio-recorded sessions with 1 to 2 patients to allow estimation of the primary outcome. After training, 87 therapists audio-recorded sessions with 1 to 2 patients. There were no significant baseline differences between those who audio-recorded sessions compared with those who did not. In total, we received audio recordings from 115 therapists before and/or after training. Pretraining recordings indicated that 9 of 97 therapists (9.3%) were using an EBT (either cognitive behavioral therapy or dialectical behavior therapy). There was no evidence of the use of IPT. Ratings of nonspecific factors of establishing rapport and using a collaborative approach were high both before and after training.

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

In the expert condition, at pretraining, the 89 therapists were distributed at a mean (SD) of 4.1 (2.4) per site, with 1.8 (0.5) patients recorded per therapist. In the trainer condition, at pretraining, the 95 therapists were distributed at a mean (SD) of 4.8 (2.1) per site, with 1.8 (0.4) patients recorded per therapist. In the expert condition, at posttraining, the 71 therapists were distributed at a mean (SD) of 3.4 (1.7) per site, with 1.7 (0.5) patients recorded per therapist. In the trainer condition, at posttraining, the 76 therapists were distributed at a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.9) per site, with 1.7 (0.5) patients recorded per therapist.

Site and Therapist Characteristics

Site, site director, and therapist characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. A diverse sample of small institutions (with 2500 students) to large institutions (with 51 000 students) and private (n = 7) and public (n = 17) institutions entered the study. Therapist-to-student ratios ranged from 1 therapist for 337 students to 1 therapist for 2900 students at various single institutions, indicating different abilities between institutions to provide services.

Table 1. Site Director and Site Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Training Condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert (n = 12) | Trainer (n = 12) | Total (N = 24) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 45.6 (8.5) | 53.3 (7.3) | 49.5 (8.7) |

| Experience as director, mean (SD), y | 7.3 (5.6) | 10.9 (7.1) | 9 (6.4) |

| Race, No. (%) | |||

| Asian | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (4.2) |

| African American | 0 | 2 (16.7) | 2 (8.3) |

| White | 9 (75.0) | 10 (83.3) | 19 (79.2) |

| Mixed | 2 (16.7) | 0 | 2 (8.3) |

| Degree, No. (%)a | |||

| Doctoral | 12 (100) | 10 (83.3) | 22 (91.7) |

| Masters | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 1 (4.2) |

| Clinical supervision frequency for eating disorders by therapist, No. (%) | |||

| <Weekly | 2 (16.7) | 3 (25.0) | 5 (20.8) |

| Weekly | 7 (58.3) | 7 (58.3) | 14 (58.3) |

| >Weekly | 2 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (12.5) |

| Staff training and educational priorityb | 4.42 (0.79) | 3.92 (0.90) | 4.17 (0.87) |

| No. of students per site | 23 475 | 13 960 | 18 853 |

| Therapists per students, ratio | 1:1840 | 1:1821 | 1:1789 |

One director did not provide degree information.

Staff training and educational priority was rated on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a very great extent) scale.

Table 2. Therapist Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Training Condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert (n = 89) | Trainer (n = 95) | Total (N = 184) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 41.1 (10.8) | 42.8 (10.3) | 41.9 (10.6) |

| Sex, No. (%)a | |||

| Male | 25 (28.1) | 13 (13.7) | 38 (20.7) |

| Female | 63 (70.8) | 77 (81.1) | 140 (76.1) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 4 (4.5) | 6 (6.3) | 10 (5.4) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) |

| Asian | 8 (9.0) | 4 (4.2) | 12 (6.5) |

| Black/African-American | 11 (12.4) | 8 (8.4) | 19 (10.3) |

| White | 66 (74.2) | 76 (80.0) | 142 (77.2) |

| Mixed | 3 (3.4) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.2) |

| Degree, No. (%)b | |||

| Doctoral | 57 (64.0) | 53 (55.8) | 110 (59.8) |

| Masters | 22 (24.7) | 33 (34.7) | 55 (29.9) |

| Other | 7 (7.9) | 4 (4.2) | 11 (6.0) |

| Experience in present position, mean (SD), y | 4.8 (5.7) | 6.2 (6.6) | 5.5 (6.2) |

| Taken interpersonal psychotherapy workshop or class, No. (%) | 23 (25.8) | 20 (21.1) | 43 (23.4) |

| Used interpersonal psychotherapy in past year, No. (%) | 39 (43.8) | 31 (32.6) | 70 (38) |

| Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale score, mean (SD)c | 2.9 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.5) |

| Job Satisfaction Scale score, mean (SD)d | 5.9 (0.6) | 5.9 (0.7) | 5.9 (0.6) |

| Adherence scoree | |||

| Pretraining | 0.05 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.07) |

| Posttraining | 0.23 (0.15) | 0.27 (0.14) | 0.25 (0.14) |

| Competence scoref | |||

| Pretraining | 0.04 (0.10) | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.03 (0.07) |

| Posttraining | 0.13 (0.15) | 0.21 (0.16) | 0.17 (0.16) |

| Interpersonal psychotherapy knowledge scoreg | |||

| Pretraining | 12.4 (2.5) | 11.4 (2.2) | 11.8 (2.4) |

| Posttraining | 13.4 (1.8) | 12.7 (2.1) | 13.1 (2.1) |

Of the 184 therapists, 178 provided information about their sex. The remaining 6 therapists did not provide information about their sex.

Of the 184 therapists, 176 provided information about their degree. The remaining 8 therapists did not provide information about their degree.

Range, 0-4 points.

Range, 1-7 points.

Range, 0 to 1 point.

Range, 0 to 2 points.

On a test of 20 multiple-choice questions.

Most directors and therapists were white (19 of 24 directors [79.2%]; 142 of 184 therapists [77.2%]), and as expected, directors tended to be older than therapists (mean [SD] age: directors, 49.5 [8.7] years; therapists, 41.9 [10.6] years) and to be more likely to have a doctoral degree (directors: 22 of 24 [91.7%]; therapists, 110 of 184 [59.8%]). Nearly one-quarter of therapists (43 of 184 [23.4%]) reported having had taken a class/workshop in IPT before training and more than one-third of therapists (70 of 184 [38.0%]) reported having used IPT in the past year. Attitudes toward evidence-based practice were in the midrange (mean [SD], 2.8 [0.5] on a scale of 0 to 4), and mean job satisfaction was high (mean [SD], 5.9 [0.6] on a scale of 1 to 7).

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Both training groups showed significant within-group improvement for IPT adherence (trainer group: 0.233 [95% CI, 0.192-0.274]; expert group: 0.190 [0.145-0.235]; both P < .001) with large effect sizes (trainer group: 1.64 [95% CI, 1.35-1.93]; expert group: 1.34 [1.02-1.66]), but there was no significant difference between conditions (Table 3). Both groups also showed significant within-group improvement in IPT competence (trainer group: 0.179 [95% CI, 0.132-0.226]; expert group: 0.106 [0.059-0.153]; both P < .001), with a large effect size for the trainer condition (1.16 [95% CI, 0.85-1.46]; P < .001) and a medium effect size for the expert condition (0.69 [95% CI, 0.38-0.99]; P < .001), as well as a significant difference between groups favoring the trainer condition (0.47 [95% CI, 0.05-0.89]; P = .03). Adherence and competence were highly correlated both before and after training (pretraining: Spearman ρ, 0.85; P < .001; posttraining: Spearman ρ, 0.83; P < .001). Within-group knowledge of IPT improved significantly for both groups (effect sizes: trainer, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.28-0.99]; P = .005; expert, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.38-1.01]; P < .001), with no significant difference between groups.

Table 3. Longitudinal Changes in Therapist-Level Outcomes.

| Outcome | Within-Group Differences | Between-Group Differences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining-to-Posttraining Change | P Value | Effect Size | Group Difference (Trainer − Expert) | P Value | Effect Size | |

| Adherence | ||||||

| Trainer | 0.233 (0.192-0.274) | <.001 | 1.64 (1.35-1.93) | 0.043 (−0.016 to 0.102) | .15 | 0.3 (−0.11 to 0.72) |

| Expert | 0.190 (0.145-0.235) | <.001 | 1.34 (1.02-1.66) | |||

| Competence | ||||||

| Trainer | 0.179 (0.132-0.226) | <.001 | 1.16 (0.85-1.46) | 0.073 (0.008-0.138) | .03 | 0.47 (0.05-0.89) |

| Expert | 0.106 (0.059-0.153) | <.001 | 0.69 (0.38-0.99) | |||

| Interpersonal psychotherapy knowledge | ||||||

| Trainer | 1.243 (0.543-1.943) | .005 | 0.64 (0.28-0.99) | −0.111 (−1.046 to 0.824) | .82 | −0.06 (−0.54 to 0.42) |

| Expert | 1.354 (0.735-1.973) | <.001 | 0.69 (0.38-1.01) | |||

Moderators and Factors Associated With Outcomes

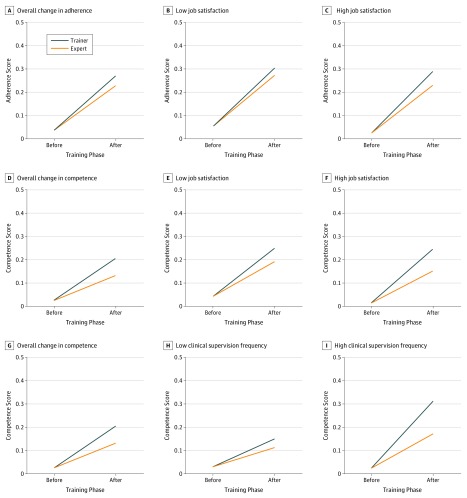

Six pretraining variables were examined as moderating factors of training on both adherence and competence: knowledge of IPT, job satisfaction, clinical supervision frequency, staff training and educational priorities, evidence-based practice attitude, and use of IPT in the past year. Job satisfaction significantly moderated the outcome of training on adherence (b, 0.120 [95% CI, 0.001-0.24]; P = .048). Figure 2 shows the overall outcome of training with respect to adherence favoring the trainer group, together with job satisfaction dichotomized. This depicts a greater difference between conditions for therapists with high job satisfaction. The trainer condition was also associated with greater competence regardless of job satisfaction, although the outcome with respect to competence was greater in the group with high job satisfaction (b, 0.133 [95% CI, 0.001-0.27]; P = .048). In addition, the frequency of clinical supervision afforded by the site moderated the outcome of training with respect to therapist competence, with a higher frequency of supervision showing greater training outcome with respect to competence (b, 0.05 [95% CI, 0.004-0.09]; P = .03). Several pretraining variables were positively associated with therapist adherence to IPT, irrespective of condition. These included evidence-based practice attitude (b, 0.10 [95% CI, 0.04-0.17]; P = .002), site staff training and educational priorities (b, 0.06 [95% CI, 0.02-0.09]; P = .003), and clinical supervision frequency (b, 0.05 [95% CI, 0.02-0.07]; P < .001). Evidence-based practice attitude (b, 0.10 [95% CI, 0.02-0.18]; P = .01) and staff training and educational priorities (b, 0.06 [95% CI, 0.02-0.10]; P = .001) were significantly associated with competence.

Figure 2. Moderating Factors of Training Intervention Outcomes of Adherence and Competence.

In A, D, and G, intention-to-treat analyses included 115 individuals; B and E, Those with scores of 6 or less were counted as having low job satisfaction (n = 46); C and F, Those with scores greater than 6 were counted as having high job satisfaction (n = 65); H, Those with supervision less than once per week were categorized as having low clinical supervision frequency (n = 33); I, Those with supervision at least once per week were categorized as having high clinical supervision frequency (n = 71).

Discussion

After training, both the expert and trainer groups showed significant improvement in IPT adherence, with large effect sizes but no significant group difference. This suggested that the trainer condition was as effective as the expert condition at improving adherence. Both groups also evidenced significantly increased IPT competence after training. The trainer condition, showing a large effect size, was significantly more effective than the expert condition in enhancing competence.

Assessing adherence alone is inadequate. It is essential to determine the competence with which interventions are implemented—in other words, to measure doing the right things well25,36—hence the importance of the findings regarding the greater effectiveness of the trainer model in developing IPT competence. Knowledge of IPT improved significantly for both conditions, with no significant difference between them.

The therapists in both conditions showed little evidence of fidelity in applying IPT at baseline. Nevertheless, 23.4% of therapists self-reported having previously taken an IPT workshop or class, and 38% reported having used IPT in the past year. However, study data indicate that, despite therapists’ self-reported experience with and use of IPT, the use of this approach was not demonstrated. In addition, ratings of all sessions revealed that other possible EBTs were rarely used before or after training, aligning with other work that has demonstrated that EBTs are rarely used in clinical practice.1,2,3,37,38 In contrast with the lack of implementation of specific EBTs, therapists showed consistently high fidelity with respect to nonspecific elements.

As per Figure 2, job satisfaction and frequency of clinical supervision emerged as significant moderating factors. High job satisfaction was associated with a greater difference between conditions on adherence, and both high job satisfaction and higher frequency of clinical supervision showed greater training effect sizes on therapist competence, particularly in the trainer condition. In line with the moderator findings, models of training transfer suggest that both trainee characteristics (including job satisfaction) and aspects of the work environment (including frequency of clinical supervision) influence how well the trainee applies and maintains newly learned skills.5,6,39,40

Limitations

Findings should be interpreted in light of limitations. We cannot generalize the findings from the selected sample of sites and therapists to college counseling centers as a whole, although we had a large number of diverse, participating colleges (eg, geographic diversity and public and private institutions). Although we were able to examine moderating factors, we did not evaluate the mechanisms by which the trainer model resulted in greater competence in IPT compared with expert training. Future research is needed to examine the specific processes underlying this result, which may then lead to increased efficiency and effectiveness of the trainer model as well sustainability in either training model. Finally, we cannot specifically generalize these findings to other EBTs but anticipate the trainer model could work equally well for other approaches. Other important future research directions include establishing standards for acceptable fidelity levels in community settings, investigating whether fidelity can be increased without substantially increasing the time for training, determining cost-effectiveness of the training approaches, assessing whether the trainer model actually facilitates training of more trainees over time, and further tailoring the treatment protocol to match the reality of college counseling centers (ie, a low limit in the number of sessions).

Conclusions

Results demonstrate that the trainer model produced training outcomes comparable with the expert model with respect to adherence and actually demonstrated superiority with respect to competence. Given its potential capability to train more therapists over time, the trainer model has the potential to facilitate widespread dissemination of EBTs like IPT.

Trial Protocol.

eAppendix. IPT Fidelity Rating Scale and Scoring.

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. The dissemination and implementation of psychological treatments: problems and solutions. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(5):516-521. doi: 10.1002/eat.22110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey AG, Gumport NB. Evidence-based psychological treatments for mental disorders: modifiable barriers to access and possible solutions. Behav Res Ther. 2015;68:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazdin AE, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Wilfley DE. Addressing critical gaps in the treatment of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(3):170-189. doi: 10.1002/eat.22670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Insel TR. Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: a strategic plan for research on mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):128-133. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: a critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clin Psychol (New York). 2010;17(1):1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: a review and critique with recommendations. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(4):448-466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karlin BE, Cross G. From the laboratory to the therapy room: national dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Am Psychol. 2014;69(1):19-33. doi: 10.1037/a0033888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlin BE, Brown GK, Trockel M, Cunning D, Zeiss AM, Taylor CB. National dissemination of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system: therapist and patient-level outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):707-718. doi: 10.1037/a0029328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walser RD, Karlin BE, Trockel M, Mazina B, Barr Taylor C. Training in and implementation of acceptance and commitment therapy for depression in the Veterans Health Administration: therapist and patient outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(9):555-563. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1986;4(3):359-373. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Canning-Ball M, Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM. Teaching community program clinicians motivational interviewing using expert and train-the-trainer strategies. Addiction. 2011;106(2):428-441. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03135.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacob N, Neuner F, Maedl A, Schaal S, Elbert T. Dissemination of psychotherapy for trauma spectrum disorders in postconflict settings: a randomized controlled trial in Rwanda. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(6):354-363. doi: 10.1159/000365114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shire SY, Kasari C. Train the trainer effectiveness trials of behavioral intervention for individuals with autism: a systematic review. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2014;119(5):436-451. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-119.5.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, et al. Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: results from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1429-1437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charney E, Goodman HC, McBride M, Lyon B, Pratt R. Childhood antecedents of adult obesity. do chubby infants become obese adults? N Engl J Med. 1976;295(1):6-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197607012950102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuijpers P, Donker T, Weissman MM, Ravitz P, Cristea IA. Interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health problems: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(7):680-687. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15091141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenberg D, Nicklett EJ, Roeder K, Kirz NE. Eating disorder symptoms among college students: prevalence, persistence, correlates, and treatment-seeking. J Am Coll Health. 2011;59(8):700-707. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.546461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissman MM, Hankerson SH, Scorza P, et al. Interpersonal counseling (IPC) for depression in primary care. Am J Psychother. 2014;68(4):359-383. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2014.68.4.359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weisz J, Bearman SK, Santucci LC, Jensen-Doss A. Initial test of a principle-guided approach to transdiagnostic psychotherapy with children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46(1):44-58. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1163708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blomquist KK, Ansell EB, White MA, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Interpersonal problems and developmental trajectories of binge eating disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(8):1088-1095. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hames JL, Hagan CR, Joiner TE. Interpersonal processes in depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:355-377. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartmann A, Zeeck A, Barrett MS. Interpersonal problems in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(7):619-627. doi: 10.1002/eat.20747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rieger E, Van Buren DJ, Bishop M, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Welch R, Wilfley DE. An eating disorder-specific model of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-ED): causal pathways and treatment implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(4):400-410. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilfley DE, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Eichen DM, et al. Training models for implementing evidence-based psychological treatment for college mental health: a cluster randomized trial study protocol. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;72:117-125. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muse K, McManus F. A systematic review of methods for assessing competence in cognitive-behavioural therapy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(3):484-499. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart MO, Raffa SD, Steele JL, et al. National dissemination of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in veterans: therapist and patient-level outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(6):1201-1206. doi: 10.1037/a0037410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loeb KL, Wilson GT, Labouvie E, et al. Therapeutic alliance and treatment adherence in two interventions for bulimia nervosa: a study of process and outcome. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1097-1107. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(8):713-721. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Ment Health Serv Res. 2004;6(2):61-74. doi: 10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024351.12294.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Development of the job diagnostic survey. J Appl Psychol. 1975;60(2):159. doi: 10.1037/h0076546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2003. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195152968.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jortberg BT, Rosen R, Roth S, et al. The fit family challenge: a primary care childhood obesity pilot intervention. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(4):434-443. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.04.150238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraemer HC, Kiernan M, Essex M, Kupfer DJ. How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approaches. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2S):S101-S108. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877-883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. Therapist competence, therapy quality, and therapist training. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(6-7):373-378. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lilienfeld SO, Ritschel LA, Lynn SJ, Cautin RL, Latzman RD. Why many clinical psychologists are resistant to evidence-based practice: root causes and constructive remedies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(7):883-900. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolitzky-Taylor K, Zimmermann M, Arch JJ, De Guzman E, Lagomasino I. Has evidence-based psychosocial treatment for anxiety disorders permeated usual care in community mental health settings? Behav Res Ther. 2015;72:9-17. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldwin TT, Ford JK. Transfer of training: a review and directions for future research. Person Psychol. 1988;41(1):63-105. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1988.tb00632.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim DH, Morris ML. Influence of trainee characteristics, instructional satisfaction, and organizational climate on perceived learning and training transfer. Hum Resour Dev Rev. 2006;17(1):85-115. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.1162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eAppendix. IPT Fidelity Rating Scale and Scoring.

Data Sharing Statement.