Abstract

The absolute temperature-dependent kinetics for the reaction between hydroxyl radicals and the chloramine water disinfectant species monochloramine (NH2Cl), as well as dichloramine (NHCl2) and trichloramine (NCl3), have been determined using electron pulse radiolysis and transient absorption spectroscopy. These radical reaction rate constants were fast, with values of 6.06 × 108, 2.57 × 108, and 1.67 × 108 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C for NH2Cl, NHCl2, and NCl3, respectively. The corresponding temperature dependence of these reaction rate constants, measured over the range 10–40 °C, is well-described by the transformed Arrhenius equations:

giving activation energies of 8.57 ± 0.58, 6.11 ± 0.40, and 5.77 ± 0.72 kJ mol−1 for these three chloramines, respectively. These data will aid water utilities in predicting hydroxyl radical partitioning and chemical contaminant removal efficiencies under real-world advanced oxidation process treatment conditions.

Keywords: Advanced oxidation processes, Chloramines, Hydroxyl radical kinetics, Temperature-dependent rate constants

1. Introduction

For over a century the disinfection of drinking water and wastewater effluent has been performed through the addition of chlorine prior to distribution for human consumption and reuse applications (CRWQCB, 2002; CDPH, 2012; Stone et al., 2009). However, the application of chlorine leads to the formation of halogenated disinfection by-products (DBPs) that are toxic to the environment and show evidence of human toxicity through chronic exposure (Rook, 1974; Krasner et al., 2006; Richardson et al., 2007; Krasner, 2009; Krasner et al., 2009a, 2009b). Consequently, many water utilities are now considering the use of monochloramine as an alternative water disinfectant because its reaction with dissolved organic matter (DOM), in general, promotes lower formation of regulated DBPs such as haloacetic acids and trihalomethanes (EPA, 1999; Diehl et al., 2000; Vikesland et al., 2001; Hua and Reckhow, 2008; Zha et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016).

However, the simultaneous presence of chloramines and chlorine reacting with DOM can increase overall DBP production (Wang et al., 2016), and the reaction of monochloramine with DOM and other trace chemical contaminants can produce N-nitrosodimethylamine and other species such as aromatic halogenated DBPs (Pan and Zhang, 2013; Hua et al., 2015; LeRoux et al., 2016; Pan et al., 2016; LeRoux et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2017) that can be more toxic than trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids, but are currently not as widely regulated (Krasner et al., 2013; Pan et al., 2013; Gong et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2016; Nihemaiti et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2016; Spahr et al., 2017). The specific timing of chloramination in the water treatment train is thus very important; chloramines need to be generated at specific times that allows for maximum microbial inhibition while minimizing harmful DBP formation (Carlson and Hardy, 1998; Hua and Reckhow, 2007; Wang et al., 2016). In post-treated wastewaters, levels of monochloramine (NH2Cl) can exceed 2 mg L−1 (measured as equivalent Cl2) (Johnson et al., 2002).

At the Orange County Water District (OCWD) Advanced Water Purification Facility (AWPF) in Fountain Valley, CA, USA chloramines are deliberately generated by adding sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) to a secondary-treated wastewater effluent prior to microfiltration (MF) to prevent reverse osmosis (RO) membrane biofouling downstream and to avoid the damaging effects of free chlorine on the thin-film composite polyamide RO membranes. The hypochlorite reacts with residual ammonia (~2.5 mg L−1) present in the secondary effluent to produce a mixture of chloramines. At the injection point, the initial high OCl−:NH3 ratio and pH (~12.5) likely favours the formation of trichloramine (NCl3); however, as the NCl3 is eventually diluted in the source water to the approximately neutral system pH, formation of both NH2Cl and dichloramine (NHCl2) will occur:

| (1) |

A large fraction of the residual chloramines pass through the MF and RO membranes and are detected in the RO permeate. Analysis of the chloramines by membrane introduction mass spectrometry indicated an approximate ratio of 48% NH2Cl: 48% NHCl2: 2% NCl3 (unpublished data), consistent with expectations at this pH of 5.5–5.7 (Palin, 1950).

As the final treatment step before groundwater recharge for indirect potable reuse, OCWD incorporates an advanced oxidation process (AOP) for disinfection and removal of any trace organic contaminants that are not effectively removed by the RO process. AOPs are characterized by their in-situ generation of highly oxidizing hydroxyl radicals (•OH). In the AWPF, UV light (254 nm) from low pressure mercury lamps is utilized with added hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to produce •OH radicals (von Gunten, 2003; von Gunten, 2007; Wert et al., 2010). The efficiency of the AOP is highly dependent upon the water quality, and consequently the introduction of chloramines into this system could significantly impact the efficiency of the desired reaction of •OH with chemical contaminants. All chloramines react with H2O2 (McKay et al., 2013), but these reactions are too slow to impact the AOP chemistry. In contrast, literature measurements for the room-temperature reaction of •OH with NH2Cl (Poskrebyshey et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2002) show that this reaction is fast, and thus this radical scavenging pathway could significantly impact the AOP efficiency:

| (2) |

Given the relative concentrations of chloramine species in the OCWD treatment system, the contribution of NHCl2 and to a lesser extent, NCl3 may also impact AOP efficiency. However, no temperature-dependent kinetic data for this reaction, nor any product species for the analogous reactions with NHCl2 and NCl3 have been reported:

| (3) |

| (4) |

Therefore, in this study, absolute temperature-dependent rate constants for •OH radical reaction with NH2Cl, NHCl2, and NCl3 were measured to allow a quantitative understanding of their impacts under AOP conditions.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and methods

Ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), sodium tetraborate decahydrate (Na2B4O7·10H2O), and hydrochloric acid (HCl) were obtained from VWR International. Potassium thiocyante (KSCN) was purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company. All chemicals were >99% purity and used as received. Solutions were prepared in Milli-Q water (≥18.2 MΩ cm−1). Concentrations of individual chloramine solutions were determined spectrophotometrically using literature (Yiin and Margerum, 1989) absorption coefficients (ε(NH2Cl) = 461 M−1 cm−1 at 243 nm, ε (NHCl2) = 272 M−1 cm−1 at 294 nm, and ε (NCl3) = 195 M−1 cm−1 at 336 nm). Fresh chloramine solutions were prepared daily as described below, kept in the dark, and were used as soon as possible at their buffered pHs. The thermal decay of the chloramines was found to be less than 10% over a 5 h period.

2.2. Chloramine preparation

The concentration of sodium hypochlorite in the stock solution was spectrophotometrically determined at λmax = 290 nm based on the absorption coefficient ε = 350.4 M−1 cm−1 (Morris, 1966). NH2Cl was prepared in 2.00 mM sodium tetraborate decahydrate solution buffered to pH 8.8 ± 0.1 by adding 20.0 mL of 6.25 mM sodium hypochlorite dropwise to 5.00 mL of 25 mM NH4Cl with vigorous stirring over a period of ~15–30 min (Jafvert and Valentine, 1992). This allowed the reaction:

| (5) |

(Margerum et al., 1994) to occur (Armesto et al., 1998). The solutions were kept stirring for at least 30 min after complete NaOCl addition. Typical efficiencies of NH2Cl production were >95%, as based on initial reactant concentrations.

Dichloramine solutions were prepared by adjusting a monochloramine solution to pH = 3.5 using hydrochloric or perchloric acid. This allowed the disproportionation reaction (Vikesland et al., 2001; Vikesland and Valentine, 2002):

| (6) |

to occur. The pH was continuously adjusted until it became stable (constant to 0.01 pH units for 10 min), and this solution was also kept in the dark until use. Dichloramine production efficiencies were 90–95% by this method. Trichloramine was produced by mixing a pH 6.5 ± 0.1 solution of NaOCl with NH4Cl in a 3:1 mol ratio. Upon complete addition, the pH was then adjusted to 3.5 ± 0.1, and left stirring for at least 30 min before experimental use (Yiin and Margerum, 1989). The efficiency of NCl3 production was 85–90% by this method.

2.3. Kinetics experiments

The nanosecond pulse radiolysis transient absorption measurements were performed using the linear electron accelerator system at the University of Notre Dame’s Radiation Research Laboratory. A detailed description of the irradiation procedure and transient absorption detection system has been published previously (Whitman et al., 1996; Hug et al., 1999).

The electron pulse radiolysis of water generates the following suite of radicals and molecular products in the stoichiometry (Buxton et al., 1988):

| (7) |

The values in brackets are the absolute yields (G-values, μmol J−1) of generation of each species. In order to isolate the •OH radical, all chloramine solutions were individually pre-saturated with N2O before mixing and irradiation, which allows the quantitative conversion of radiolytically-produced hydrated electrons and some hydrogen atoms to •OH (Buxton et al., 1988):

| (8) |

| (9) |

Absolute energy deposition measurements (dosimetry, Buxton and Stuart (1995)) were performed using N2O saturated solutions of 1.00 × 10−2 M KSCN at λmax = 475 nm, (Gε = 5.2 × 10−4 m2 J−1) with doses of 3–5 Gy per 2–3 ns pulse, giving initial •OH concentrations in the range 2–4 μM.

During kinetic measurements, NH2Cl solutions were continuously sparged with the minimum amount of N2O necessary to prevent air ingress. The more volatile NHCl2 and NCl3 solutions were not sparged, instead they were kept in glass vessels whose head space was filled with N2O gas. All transient absorption measurements were made using a quartz flow cell, with the flow adjusted such that each irradiation occurred on a fresh sample. Sample solutions were flowed through a temperature-controlled condenser into the cell, and the solution temperature was measured immediately after the irradiation. The temperature stability of the system was ±0.3 °C. Typically, 10–15 individual measurements were averaged to generate a single kinetic trace. The quoted errors for the reaction rate constants of this study are a combination of the measurement precision and concentration errors.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Monochloramine reaction with hydroxyl radical

The hydroxyl radical has been demonstrated to react with monochloramine by hydrogen atom abstraction (Reaction (2)), yielding water and the •NHCl radical (Poskrebyshey et al., 2003). To determine the temperature-dependence rate constants for this reaction, we used benzoate competition kinetics, as no significant transient absorption change was found in the UV–visible region (200–800 nm) for the concentration of radicals produced under our experimental conditions. The reaction of •OH with benzoate () gives the transient adduct :

| (10) |

which has a strong absorption at 350 nm (Hug, 1981). The temperature dependence of Reaction (10) has been well established, and over the range 10–70 °C is given by (Ashton et al., 1995; Poskrebyshey et al., 2002):

| (11) |

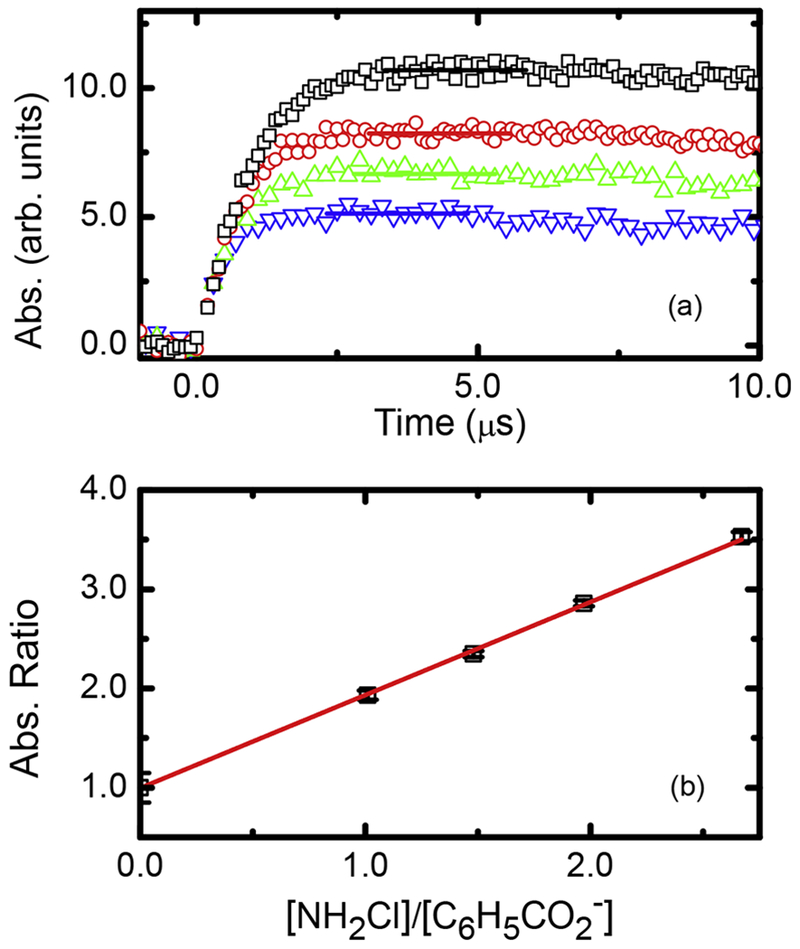

Upon addition of NH2Cl to a benzoate solution, the competition for the •OH radical results in a decrease in the absorption intensity of the benzoate adduct transient, as shown in Fig. 1a. The competition between Reactions (2) and (10) is readily solved to give the following relationship:

| (12) |

where is the yield of the transient adduct absorbance in the absence of NH2Cl, and is the reduced yield in the presence of NH2Cl. By plotting this ratio of intensities against the concentration ratio (Fig. 1 (b)) an excellent straight line with a slope of k2/k10 is obtained. Based on the calculated rate constant of k10 = 6.2 × 109 M−1 s−1 at this temperature, this gives a calculated absolute second-order rate coefficient of (6.10 ± 0.08) × 108 M−1 s−1. However, this calculated value includes the contribution of Reaction (2) as well as that of residual ammonia with •OH (Buxton et al., 1988):

| (13) |

Fig. 1.

(a) Growth kinetics of at 350 nm for N2O saturated solutions of 102.5 μM benzoate at pH 9.2 in aqueous solution at 22.2 °C with 0(□), 0.52 (O), 1.01 (Δ), and 1.48 mM (∇) NH2Cl (b) Transformed competition kinetics plot using maximum intensity data (shown as horizontal lines) in (a). Solid line is weighted linear fit, with slope value of (0.984 ± 0.019) and an intercept of 0.998 ± 0.003, R2 = 0.999. This slope corresponding to a total k = (6.10 ± 0.12) × 108 M−1 s−1 under these conditions.

Residual NH3 is presumed to exist as the formation of NH2Cl (Reaction (5)) is not quantitative (measured at ~95% using a theoretical yield based on NaOCl and chloramine absorption coefficients). By taking this small side reaction into account, a final value of k2 = (5.99 ± 0.12) × 108 M−1 s−1 is obtained, in very good agreement with the 22 ± 1 °C reported value (Poskrebyshey et al., 2003) of (5.1 ± 0.6) × 108 M−1 s−1. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of reported rate constants for •OH with single chlorine-containing chemicals in aqueous solution; however, our measured room-temperature rate constant for NH2Cl is also comparable to the reaction of the hydroxyl radical with chloroethane, determined as 5.5 × 108 M−1 s−1 (Milosavljevic et al., 2005), but significantly higher than measured for chloroacetamide ((8.1 ± 0.3) × 107 M−1 s−1, Xu et al., 2014) or chloronitromethane ((1.9 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1 s−1, Mincher et al., 2010; Mezyk et al., 2006).

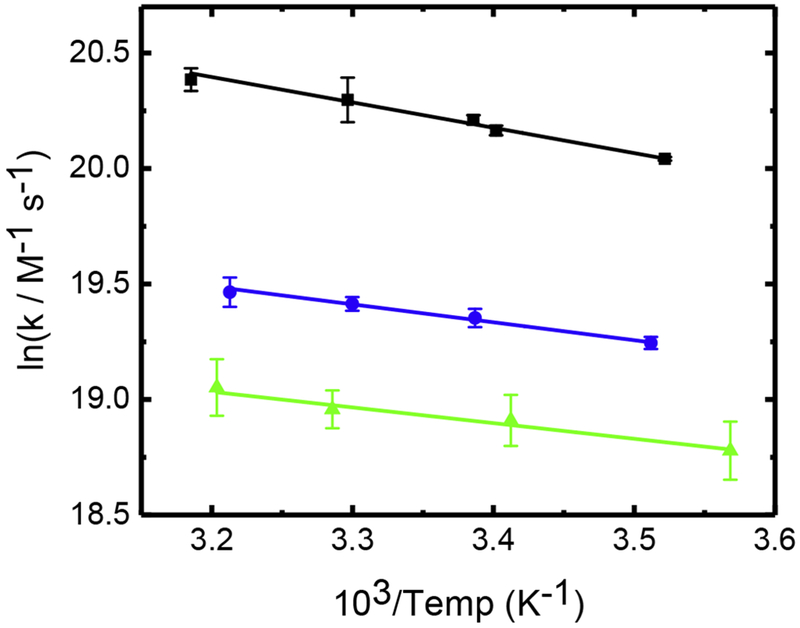

Similar benzoate competition kinetics measurements were made for NH2Cl reaction over the temperature range of 10–41 °C, the second-order rate constants obtained are summarized in Table 1. These NH2Cl reaction data are well described by the transformed Arrhenius equation:

| (14) |

corresponding to an activation energy of Ea2 = 8.57 ± 0.58 kJ mol−1 (see Fig. 2). No comparable literature data were found for this measured activation energy.

Table 1.

Summary of temperature-dependent rate constants measured in this study.

| Species | Temperature °C | 10−8 k value M−1 s−1 | Ea kJ mol−1 | ln (A) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH2Cl | 10.8 | (5.06 ± 0.04) | ||

| 20.8 | (5.72 ± 0.12) | |||

| 22.2 | (5.99 ± 0.12) | 8.57 ± 0.58 | 23.68 ± 0.23 | |

| 30.2 | (6.53 ± 0.63) | |||

| 40.8 | (7.13 ± 0.35) | |||

| NHCl2 | 11.6 | (2.28 ± 0.06) | ||

| 22.1 | (2.54 ± 0.10) | 6.11 ± 0.40 | 21.96 ± 0.56 | |

| 29.9 | (2.70 ± 0.08) | |||

| 38.1 | (2.84 ± 0.18) | |||

| NCl3 | 7.1 | (1.43 ± 0.18) | ||

| 19.9 | (1.63 ± 0.18) | 5.77 ± 0.72 | 21.26 ± 0.29 | |

| 31.2 | (1.71 ± 0.14) | |||

| 39.0 | (1.88 ± 0.23) |

Fig. 2.

Arrhenius plot for the reaction of •OH with NH2Cl (▪), NHCl2 (●), and NCl3 (▴). Solid lines correspond to weighted linear fits, corresponding to activation energies of Ea2 = 8.57 ± 0.58, Ea3 = 6.11 ± 0.40, and Ea4 = 5.77 ± 0.72 kJ mol−1, respectively.

3.2. Determination of di- and trichloramine spectra and kinetics

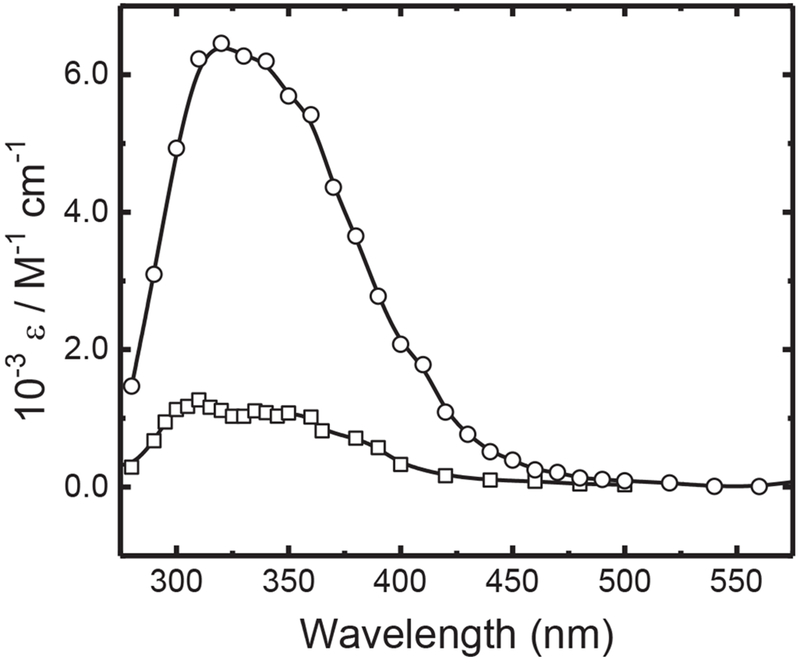

Conversely to NH2Cl the pulse irradiation of an aqueous solution of NHCl2 gave a measurable transient absorption spectrum peaking at 310 nm (see Fig. 3). The same, but more intense, absorption spectrum was observed for hydroxyl radical reaction with NCl3. Absorption coefficients for these spectra were calculated based upon our measured dosimetry (which gave absolute initial •OH concentrations), utilizing the scavenging radical yield corrections of LaVerne and Pimblott (1993).

Fig. 3.

Absolute transient absorption spectra obtained for NCl2• radical from reaction of hydroxyl radical reaction with NHCl2 (□) and NC13 (O).

By assuming that Cl-atom abstraction is the only possible mechanism for •OH reaction with NCl3, we can attribute these measured transient absorptions to the •NCl2 radical. For NH2Cl, there are two possible products of the hydroxyl radical-induced oxidation:

| (3a) |

| (3b) |

Through normalization of the NHCl2 measured product spectra to that obtained for NCl3 (at 310 nm) we can readily calculate the branching ratio for the overall NHCl2 reaction to be 20.3% for Reaction (3a) and 79.7% for Reaction (3b). These fractions can be used to calculate individual reaction rate constants for these two reactions (see later). It is also important to note that while the •NHCl radical also absorbs in this wavelength region (Poskrebyshey et al., 2003) this previous study showed that the •NHCl radical intensity was similar to the aqueous •NH2 radical peak (ε = 80 M−1 cm−1, Hug, 1981), and thus at our product radical concentrations, the absorbance of produced •NHCl in Reaction (3b) would not significantly contribute to the overall •NCl2 intensity seen in our study.

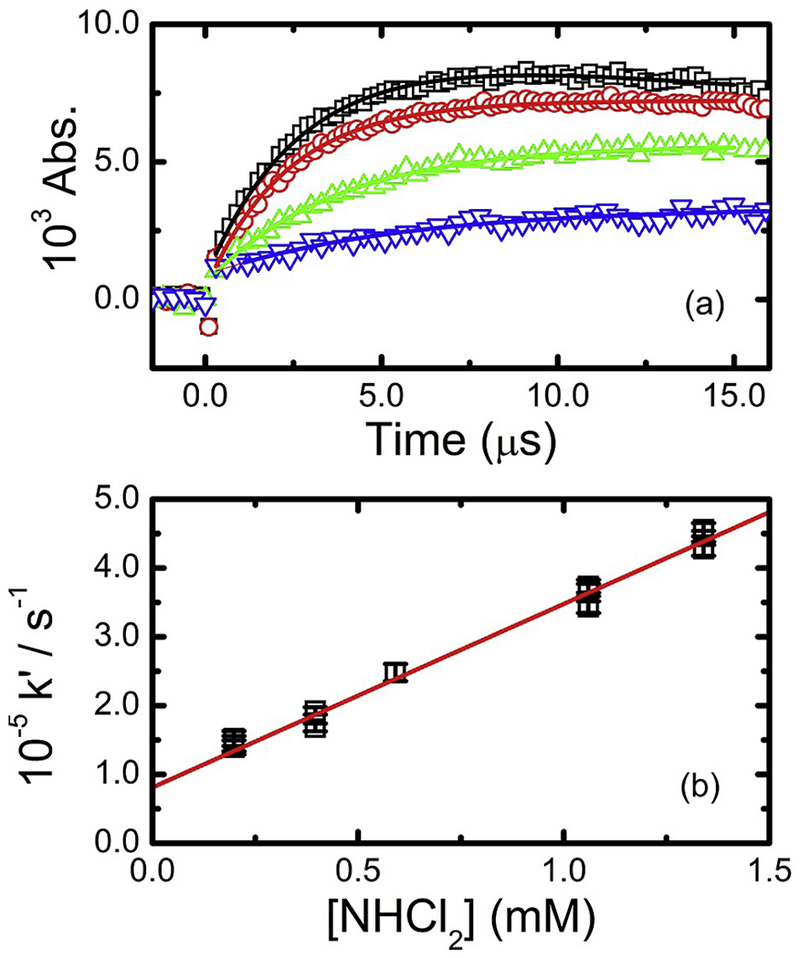

3.3. Dichloramine reaction with the hydroxyl radical

The kinetics of hydroxyl radical reaction with NHCl2 were directly measured at 310 nm. Typical kinetic data at 22.1 °C are given in Fig. 4. These measurements were conducted at pH 3.3, to maximize the stability of dichloramine in aqueous solution. By fitting the measured transient absorptions (Fig. 4a) to exponential growth kinetics, pseudo-first-order rate coefficients were attained. Plotting these fitted values against the dichloramine concentration (Fig. 4b) yielded a total second-order rate coefficient of k3 = (2.54 ± 0.12) × 108 M−1 s−1 under these conditions. From the spectral analysis performed for this compound, this overall rate constant consists of the sum of Reaction (3a) and (3b) pathways, from which we can calculate k3a = (5.2 ± 0.2) × 107 M−1 s−1 and k3b = (2.0 ± 0.1) × 108 M−1 s−1 at 22.1 °C. The overall rate constants for this reaction measured over the range 11–38 °C, were well described by the equation:

| (15) |

corresponding to an activation energy of Ea3 = 6.11 ± 0.40 kJ mol−1 for both pathways. All the measured temperature-dependent kinetic data for NHCl2 are summarized in Table 1, and shown in Fig. 2. Again, no comparable Arrhenius parameters for analogous species were found in the literature. However, the decrease in hydroxyl radical reactivity between NH2Cl (5.99 × 108 M−1 s−1) to NHCl2 (2.54 × 108 M−1 s−1) at ~22 °C is consistent with the decrease seen for this radical reaction with chloromethane (5.5 × 108 M−1 s−1) and 1,1-dichloroethane (1.3 × 108 M−1 s−1) in aqueous solution (Milosavljevic et al., 2005). In contrast, an increase in reaction rate constant was seen in going from chloroacetamide ((8.1 ± 0.3) × 107 M−1 s−1) to dichloracetamide ((1.25 ± 0.02) × 108 M−1 s−1; Xu et al., 2014), and from chloronitromethane ((1.9 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1 s−1) to dichloronitromethane ((5.1 ± 0.8) × 108 M−1 s−1; Mezyk et al., 2006).

Fig. 4.

(a) Transient absorption kinetics determined at 310 nm for reaction of hydroxyl radical with dichloramine in N2O-saturated solution at pH 3.3 and 22.1 °C for 1.34 (□), 1.06 (O), 0.40 (Δ), and 0.20 mM (∇) NHCl2. Fitted lines are pseudo first-order growth kinetics, with rate constants of (4.57 ± 0.09) × 105, (3.68 ± 0.09) × 105, (1.92 ± 0.05) × 105, and (1.39 ± 0.10) × 105 s−1, respectively (b) Transformed second-order kinetic plot from kinetic data. Solid line corresponds to weighted linear fit, with slope corresponding to k = (2.54 ± 0.12) × 108 M−1 s−1, R2 = 0.994.

3.4. Trichloramine reaction with hydroxyl radical

The kinetics of hydroxyl radical reaction with NCl3 were measured as for NHCl2, at pH 3.5. However, for this chloramine, concentrations had to be corrected for thermal decay over the time course of the irradiation experiments. This was achieved by directly measuring the decay of the initial trichloramine solution with time using UV–vis spectrophotometry. The reaction rate constants (see Table 1) for the temperature-dependent reaction of the hydroxyl radical with NCl3 was found to be well described by:

| (16) |

corresponding to an activation energy of Ea4 = 5.77 ± 0.72 kJ mol−1 over the temperature range 7–39 °C. The room-temperature rate constant for this reaction, k4 = 1.67 × 108 M−1 s−1 is again slower than for NH2Cl and NHCl2, again consistent with the lower reactivity of 1,1,1-trichloroethane (k < 5 × 106 M−1 s−1, Milosavljevic et al., 2005) and for trichloronitromethane ((4.8 ± 0.4) × 107 M−1 s−1, Cole et al., 2007).

Overall, the second-order rate constant for the reaction between chloramines and the hydroxyl radical follows the order mono- > di- > trichloramine, with NH2Cl being approximately a factor of two more reactive than NHCl2 and NCl3. In addition, there is a clear grouping of activation energies and Arrhenius pre-factors that is dependent upon the degree of chlorine substitution. We attribute these differences to the change in •OH reaction mechanism, from mainly H-atom abstraction for monochloramine to only Cl-atom abstraction for trichloramine. This is also reflected in the calculated Erying values, where for di- and trichloramine ΔH ≈ 3.5 kJ mol−1 and ΔS ≈ −73 J mol−1K−1, in contrast to monochloramine where ΔH ≈ 6 kJ mol−1 and ΔS ≈ −56 J mol−1 K−1.

3.5. Applicability to AOP treatment conditions

It is important to quantitatively account for the presence of all three chloramines within an AOP, especially as their presence will significantly interfere with the remediation chemistry that occurs, specifically through reaction of formed hydroxyl radicals with these disinfectants rather than removal of the target chemical contaminants of concern. Although development of a full kinetic model is beyond the scope of this work, as this would require quantitative evaluation of all the intermediates formed in these oxidations, as well as their radical reaction rate constants, the kinetic data from this study provides a useful foundation for the initial evaluation of the AOP efficiencies in removing trace levels of chemical contaminants. For example, on rare occasion 1,4-dioxane has been detected in OCWD AOP feedwater at a concentration of 1–3 μg/L. This amount was subsequently reduced to non-detect (<1 μg/L) in the UV/H2O2 AOP. This is a compound of concern (CDPH, 2010), and since 1,4-dioxane is not readily photolyzed, it requires •OH oxidation for its degradation (Patton et al., 2017). Assuming a concentration of 2 μg/L entering the AOP, Table 2 summarizes the most important •OH radical reactions for 1,4-dioxane in wastewater that has undergone primary, secondary, MF, and RO treatments prior to the final AOP with UV/H2O2. Based on these typically measured concentrations of these treated wastewater standard constituents, the photolytically produced •OH radicals will partition according to the relative rates of the individual reactions:

| (17) |

Table 2.

Summary of •OH reactivity with wastewater constituents in OCWD AOP system.

| Reaction | k @ 25 °Cb (M−1 s−1 | [Species] (mol dm−3) | •OH partitioning w/o chloramines (%) | •OH partitioning w/chloramines (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| •OH + 1,4-dioxane → products | 2.50 × 109 | 2.27 × 10−8 | 4.7 × 10−4 | 1.9 × 10−4 |

| •OH + H2O2 → H2O + HO2• | 9.00 × 107 | 8.82 × 10−5 | 65.5 | 26.2 |

| 8.50 × 106 | 3.74 × 10−4 | 22.9 | 9.2 | |

| •OH + DOM → H2O + DOM• | 2.25 × 108 | 6.25 × 10−6 | 11.6 | 4.6 |

| •OH + NH2Cl → H2O + NHCl• | 6.06 × 108 a | 2.38 × 10−5 | – | 47.6 |

| •OH + NHCl2 → H2O + NCl2•/HOCl + NHCl• | 2.57 × 108 a | 1.43 × 10−5 | – | 12.1 |

| •OH + NCl3 → HOCl + NCl2• | 1.67 × 108 a | 4.15 × 10−7 | – | 0.23 |

Calculated using measured Arrhenius behaviour.

Buxton et al., 1988 or this study.

Although the fraction of •OH radicals reacting with 1,4-dioxane is small under both circumstances, by including the scavenging reactions of chloramines into this calculation, it is seen that approximately 60% of the •OH radicals are scavenged by these three chloramine species, with a concomitant decrease of •OH reactivity with 1,4-dioxane by ~150%.

4. Conclusions

Absolute second-order temperature-dependent rate constants for hydroxyl radical reaction with mono-, di-, and trichloramine in aqueous solution have been determined. At 25 °C, these rate constants were calculated to be 6.06 × 108, 2.57 × 108, and 1.67 × 108 M−1 s−1, respectively with corresponding activation energies of 8.57, 6.11, and 5.77 kJ mol−1. The •OH radical reaction with monochloramine gives •NHCl as the radical product. For trichloramine, HOCl and the •NCl2 radical are the proposed products for •OH reaction. Based on the transient absorbance intensity of the •NCl2 radical formed for the hydroxyl radical reaction with NHCl2, there were two sets of products; H2O/•NCl2 (20.3%) and HOCl/•NHCl (79.7%). A relative rates analysis showed that the presence of the three chloramine species in an advanced oxidation process treatment of wastewaters will significantly decrease the overall efficiency of hydroxyl radical reaction with chemical contaminants of concern, with up to 60% of produced •OH reacting with these species instead of contaminants of concern.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Absolute hydroxyl radical rate constants for three chloramine species in water.

Temperature-dependent oxidation kinetics and identified product species.

Impacts on advanced oxidation process efficiency due to chloramines presence.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Orange County Water District for partial funding of this research. Kinetic measurements were made using the LINAC accelerator facility at the Radiation Laboratory, University of Notre Dame, which is supported by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. James Kiddle for useful discussions throughout this work.

References

- Armesto XL, Canle M, Garcia MV, Santaballa JA, 1998. Aqueous chemistry of N-halo-compounds. Chem. Soc. Rev 27, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton L, Buxton GV, Stuart CR, 1995. Temperature dependence of the rate of reaction of OH with some aromatic compounds in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans 91, 1631–1633. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton GV, Greenstock CL, Helman WP, Ross AB, 1988. Critical review of rate constants for the reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms, and hydroxyl radicals (•OH/O•−) in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 17, 513–886. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton GV, Stuart CR, 1995. Re-evaluation of the thiocyanate dosimeter for pulse radiolysis. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans 92, 279–281. [Google Scholar]

- CDPH, 2010. Drinking Water Notification Levels and Response Levels: an Overview. California Department of Public Health, Sacramento, CA: http:www.cdph.ca.gov/certlic/drinkingwater/Documents/Notificationlevels/NotificationLevels.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- CDPH, 2012. Drinking Water-related Regulations. California Department of Public Health, Sacramento, CA: http://www.cdph.ca.gov/certlic/drinkingwater/Pages/Lawbook.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- CRWQCB, 2002. Santa Ana Region WATER Reclamation Requirements for the Orange County Water District Green Acres Project Orange County. Order No. R8-2002-0077 California Regional Water Quality Control Board, Sacramento, CA: http:222.waterboards.ca.gov/santaana/board_decisions/adopted_orders/orders/2002/02_077_wdr_ocwd_green_acres_10252002.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Hardy D, 1998. Controlling DBPs with monochloramine. J. Am. Water Works Assoc 90, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Cole SK, Cooper WJ, Fox RV, Gardinali PR, Mezyk SP, Mincher BJ, O’Shea KE, 2007. Free radical chemistry of disinfection byproducts. 2. Rate constants and degradation mechanisms of trichloronitromethane (Chloropicrin). Env. Sci. Technol 41, 863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl AC, Speitel GE, Symons JM, Krasner SW, Hwang CJ, Barrett SE, 2000. DBP formation during chloramination. J. Am. Water Works Assoc 92, 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- EPA, 1999. Alternative Disinfectants and Oxidants Guidance Manual EPA815-R-99-014. http://water.epa.gov/lawsregs/rulesregs/sdwa/mdbp/upload/2001_07_13_mdbp_alternative_disinfectants_guidance.pdf.

- Gong T, Zhang X, Li Y, Xian Q, 2016. Formation and toxicity of halogenated disinfection byproducts resulting from linear alkylbenzene sulfonates. Chemosphere 149, 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z-B, Lin Y-L, Xu B, Huang H, Zhang T-Y, Tian F-X, Gao N-Y, 2016. Degradation of chlortoluron during UV irradiation and UV/chlorine processes and formation of disinfection by-products in sequential chlorination. Chem. Eng. J 283, 412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Hua G, Reckhow DA, 2007. Comparison of disinfection byproduct formation from chlorine and alternative disinfectants. Water Res. 41, 1667–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua GH, Reckhow DA, 2008. DBP formation during chlorination and chloramination: effect of reaction time, pH, dosage, and temperature. J. Am. Water Works Assoc 100, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hua G, Reckhow DA, Abusallout I, 2015. Correlation between SUVA and DBP formation during chlorination and chloramination of NOM fractions from different sources. Chemosphere 130, 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hug G, 1981. Optical Spectra of Nonmetallic Inorganic Transient Species in Aqueous Solution. NSRDS-NBS 69.

- Hug GL, Wang Y, Schöneich C, Jiang PY, Fessenden RW, 1999. Multiple time scales in pulse radiolysis. application to bromide solutions and dipeptides. Radiat. Phys. Chem 54, 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Jafvert CT, Valentine RL, 1992. Reaction scheme for the chlorination of ammoniacal water. Environ. Sci. Technol 26, 577–586. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Zhang X, Zhu X, Li Y, 2017. Removal of intermediate aromatic halogenated DBPs by activated carbon absorption: A new approach to controlling halogenated DBPs in chlorinated drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol 51, 3435–3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson HD, Cooper WJ, Mezyk SP, Bartels DM, 2002. Free radical reactions of monochloramine and hydroxylamine in aqueous solution. Radiat. Phys. Chem 65, 317–326. [Google Scholar]

- Krasner SW, Weinberg HS, Richardson SD, Pastor SJ, Chinn R, Sclimenti MJ, Onstad GD, Thurston AD Jr., 2006. Occurrence of a new generation of disinfection byproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol 40, 7175–7185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasner SW, 2009. The formation and control of emerging disinfection byproducts of health concern. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 367, 4077–4095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasner SW, Westerhoff P, Chen B, Rittmann BE, Nam S-N, Amy G, 2009a. Impact of wastewater treatment processes on organic carbon, organic nitrogen, and DBP precursors in effluent organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol 43, 2911–2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasner SW, Westerhoff P, Chen B, Rittman BE, Amy G, 2009b. Occurrence of disinfection byproducts in United States wastewater treatment plant effluents. Environ. Sci. Technol 43, 8320–8325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasner SW, Mitch WA, McCurry DL, Hanigan D, Westerhoff P, 2013. Formation, precursors, control, and occurrence of nitrosamines in drinking water: A review. Water Res 47, 4433–4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVerne JA, Pimblott SM, 1993. Yields of hydroxyl radical and hydrated electron scavenging reactions in aqueous solutions of biological interest. Rad. Res 135, 16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoux J, Nihemaiti M, Croue J-P, 2016. The role of aromatic precursors in the formation of haloacetamides by chloramination of dissolved organic matter. Water Res 88, 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoux J, Plewa MJ, Wagner ED, Nihemaiti M, Dad A, Croue J-P, 2017. Chloramination of wastewater effluent: toxicity and formation of disinfection byproducts. J. Environ. Sci 58, 135–145. 10.1016/j.jes.2017.04.022 in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margerum DW, Schurter LM, Hobson J, Moore EE, 1994. Water chlorination chemistry: nonmetal redox kinetics of chloramine and nitrite ion. Environ. Sci. Technol 28, 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay G, Sjelin B, Chagnon M, Ishida KP, Mezyk SP, 2013. Kinetic studies of the reactions between chloramine disinfectants and hydrogen peroxide: temperature dependence and reaction mechanism. Chemosphere 92, 1417–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezyk SP, Helgeson T, Cole SK, Cooper WJ, Fox RV, Gardinali PR, Mincher BJ, 2006. Free radical chemistry of disinfection-byproducts. 1. Kinetics of hydrated electron and hydroxyl radical reactions with halonitromethanes in water. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 2176–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milosavljevic BH, LaVerne JA, Pimblott SM, 2005. Rate coefficient measurements of hydrated electrons and hydroxyl radicals with chlorinated ethanes in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. A 109, 7751–7756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mincher BJ, Mezyk SP, Cooper WJ, Cole SK, Fox RV, Gardinali PR, 2010. Free-radical chemistry of disinfection byproducts. 3. Degradation mechanisms of chloronitromethane, bromonitromethane, and dichloronitromethane. J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, 1966. The acid ionization constant of HOCl from 5 to 35 °C. J. Chem 70, 3798–3800. [Google Scholar]

- Nihemaiti M, Le Roux J, Hoppe-Jones C, Reckhow DA, Croue J-P, 2016. Formation of haloacetonitriles, haloacetamides, and nitrogenous heterocyclic byproducts by chloramination of phenolic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol 51, 655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palin A, 1950. A study of the chloro derivatives of ammonia. Water Water Eng October: 151–159, November: 189,–200, December: 248–256. [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Zhang X, 2013. Four groups of new aromatic halogenated disinfection byproducts: effect of bromide concentration on their formation and speciation in chlorinated drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol 47, 1265–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Zhang X, Wagner ED, Osiol J, Plewa MJ, 2013. Boiling of simulated tap water: effect on polar brominated disinfection byproducts, halogen speciation, and cytotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol 48, 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Zhang X, Li Y, 2016. Identification, toxicity and control of iodinated disinfection byproducts in cooking with simulated chlor(am)innated tap water and iodized table salt. Water Res. 88, 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton S, Li W, Couch KD, Mezyk SP, Ishida KP, Liu H, 2017. Impact of the ultraviolet photolysis of monochloramine on 1,4-dioxane removal: new insights into potable water reuse. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 4, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Poskrebyshey GA, Huie RE, Neta P, 2002. Temperature dependence of the acid dissociation constant of the hydroxyl radical. J. Phys. Chem. A 106,11488–11491. [Google Scholar]

- Poskrebyshey GA, Huie RE, Neta P, 2003. Radiolytic reactions of monochloramine in aqueous solutions. J. Phys. Chem 107, 7423–7428. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson SD, Plewa MJ, Wagner ED, Schoeny R, DeMarini DM, 2007. Occurrence, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity of regulated and emerging disinfection by products in drinking water: a review and roadmap for research. Mutat. Res 636, 178–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook JJ, 1974. Formation of haloforms during chlorination of natural waters. Water Treat. Exam 23, 234. [Google Scholar]

- Spahr S, Cirpka OA, von Gunten U, Hofstetter TB, 2017. Formation of N-nitro-sodimethylamine during chloramination of secondary and tertiary amines: role of molecular oxygen and radical intermediates. Environ. Sci. Technol 51, 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone ME, Scott JW, Schultz ST, Berry DL, Wilcoxon M, Piwoni M, Panno B, Bordson G, 2009. Comparison of chlorine and chloramine in the release of mercury from dental amalgam. Sci. Total Environ 407, 770–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F-X, Xu B, Lin Y-L, Hu C-Y, Zhang T-Y, Xia S-J, Chu W-H, Gao N-Y, 2017. Chlor(am)inatino of iopamidol: kinetics, pathways and disinfection byproduct formation. Chemosphere. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.06.012. in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikesland PJ, Ozekin K, Valentine RL, 2001. Monochloramine decay in model and distribution water systems. Water Res. 35, 1766–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikesland PJ, Valentine RL, 2002. Modeling the kinetics of ferrous iron oxidation by monochloramine. Environ. Sci. Technol 36, 662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gunten U, 2003. Ozonation of drinking water: part I. Oxidation kinetics and product formation. Water Res. 37,1443–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gunten U, 2007. The basics of oxidants in water treatment. Part B: ozone reactions. Water Sci. Technol 55, 25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Gao B, Ma D, Li R, Sun S, Yue Q, Wang Y, Li Q, 2016. Effects of operating conditions on trihalomethanes formation and speciation during chloramination in reclaimed water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 23, 1576–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wert EC, Rosario-Ortiz FL, Snyder SA, 2010. Evaluation of the efficiency of UV/H2O2 for the oxidation of pharmaceuticals in wastewater. Water Res. 44, 1440–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman K, Lyons S, Miller R, Nett D, Treas P, Zante A, Fessenden RW, Thomas MD, Wang Y, 1996. Linear accelerator for radiation chemistry research at Notre Dame. In: Proceedings of the ’95 Particle Accelerator Conference and International Conference on High Energy Accelerators, Texas, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Cooper WJ, Song W, 2014. Free radical destruction of haloacetamides in aqueous solution. Water. Sci. Tech.-W. Sup 14, 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Yiin BS, Margerum DW, 1989. Non-metal redox kinetics: reactions of sulfite with dichloramines and trichloramines. Inorg. Chem 29, 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng T, Glover CM, Marti EJ, Woods-Chabane GC, Karanfil T, Mitch WA, Dickenson ERV, 2016. Relative importance of different water categories as sources of N-Nitrosamine precursors. Environ. Sci. Technol 50, 13239–13248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha X-S, Liu Y, Liu X, Zhang Q, Dai R-H, Ying L-W, Wu J, Wang J-T, Ma L, 2014. Effects of bromide and iodide ions on the formation of disinfection byproducts during ozonation and subsequent chlorination of water containing biological source matters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 21, 2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]