Abstract

Objectives:

We assessed intrauterine device (IUD) preference among women presenting for emergency contraception (EC) and the probability of pregnancy among concurrent oral levonorgestrel (LNG) plus LNG 52 mg IUD EC users.

Methods:

We offered women presenting for EC at a single family planning clinic the CuT380A IUD (copper IUD) or oral LNG 1.5 mg plus the LNG 52 mg IUD. Two weeks after IUD insertion, participants reported the results of a self-administered home urine pregnancy test. The primary outcome, EC failure, was defined as pregnancies resulting from intercourse occurring within five days prior to IUD insertion.

Results:

One hundred eighty-eight women enrolled and provided information regarding their current menstrual cycle and recent unprotected intercourse. Sixty-seven (36%) chose the copper IUD and 121 (64%) chose oral LNG plus the LNG IUD. The probability of pregnancy two weeks after oral LNG plus LNG IUD EC use was 0.9% (95% CI 0.0–5.1%). The only positive pregnancy test after treatment occurred in a woman who received oral LNG plus the LNG IUD and who had reported multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse including an episode more than 5 days prior to treatment.

Conclusions:

Study participants seeking EC who desired an IUD preferentially chose oral LNG 1.5 mg with the LNG 52 mg IUD over the copper IUD. Neither group had EC treatment failures. Including the option of oral LNG 1.5 mg with concomitant insertion of the LNG 52 mg IUD in EC counseling may increase the number of EC users who opt to initiate highly effective reversible contraception.

Implications:

Consideration should be given to LNG IUD insertion with concomitant use of oral LNG 1.5 mg for EC. Use of this combination may increase the number of women initiating highly effective contraception at the time of their EC visit.

Keywords: Emergency contraception, copper IUD, levonorgestrel IUD, pregnancy

1. Introduction

Increased availability of emergency contraception (EC) pills has not reduced population rates of abortion or unintended pregnancy in the United States [1]. The copper intrauterine device (IUD) for EC is rarely employed in the United States [2] despite widespread professional organization support [3–9] and demonstrated superiority in reducing rates of unintended pregnancy compared to oral EC [10].

Women presenting for EC may be more likely to initiate a highly effective method of contraception if they have options beyond the copper IUD. Utah women selecting IUDs outside of the EC setting show a strong preference for the levonorgestrel (LNG) IUD [11]. The LNG 52 mg IUD is not labeled for EC. A novel approach is to pair the LNG 52 mg IUD with oral LNG 1.5 mg after unprotected intercourse. This prospective cohort study aimed to assess 1) EC users’ preference for the copper IUD versus oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD for EC and 2) the probability of pregnancy for participants choosing an oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD EC regimen.

2. Material and methods

Study staff approached all women seeking EC at a single family planning clinic in Salt Lake City, UT from June 2013 to September 2014 for participation in this study. Patients fluent in English or Spanish, aged 18–35 years old, who requested EC after unprotected intercourse within the previous 120 h and had a negative urine pregnancy test (Osom® card pregnancy test, Genzyme Diagnostics, human chorionic gonadotropin ≤ 20 IU/L) were eligible for participation. Inclusion criteria also required a desire to initiate an IUD, desire to prevent pregnancy for at least one year, history of regular menstrual cycle (24–35 days), and knowledge of date of last menstrual period (LMP). This information provided an estimate of menstrual cycle day for: unprotected intercourse, IUD insertion and pregnancy dating, if needed. Exclusion criteria included a positive urine pregnancy test, breastfeeding, vaginal bleeding of unknown etiology, current use of a highly effective method of contraception (sterilization, IUD or contraceptive implant), current intrauterine infection, untreated Neisseria gonorrhea or Chlamydia trachomatis infection, allergy to LNG or copper (respective to participants’ choice of device), and known abnormalities of the uterine cavity such as bicornuate uterus, uterine didelphys, or a uterine leiomoyoma impinging on the uterine cavity.

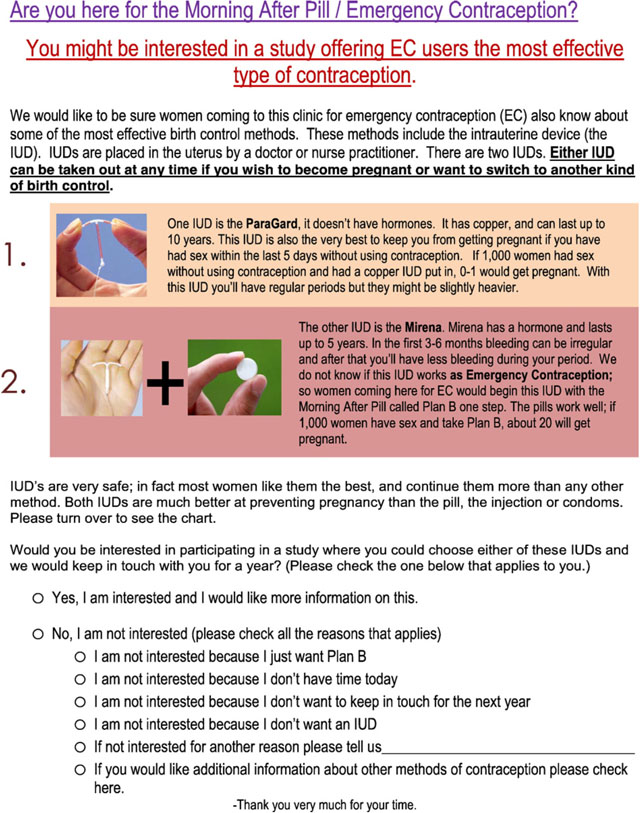

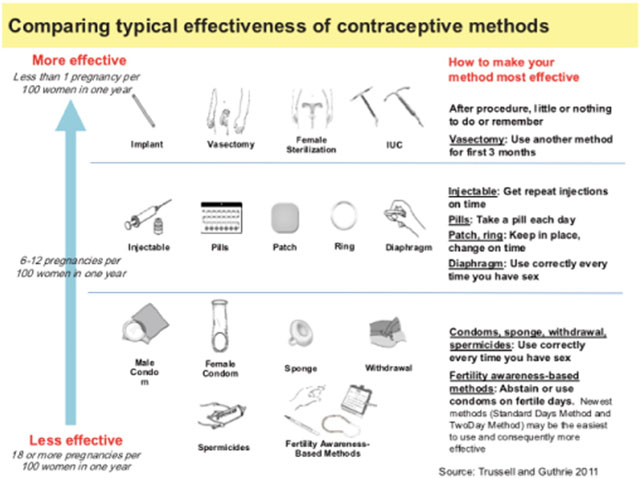

Potential participants received a printed handout describing the study (see Appendix A). This handout described the two study regimens in lay terms and the efficacy of each of the EC options. This handout did not include data on possible changes in oral LNG 1.5 mg EC efficacy based on weight or BMI. All participants provided informed consent. Study staff tested participant cell phone numbers provided at the time of enrollment to ensure a reliable method of follow-up. Participants selected either the 1) Cu T380A IUD (ParaGard®, Teva Women’s Health, Inc.) or 2) oral LNG 1.5 mg (PlanB One-Step®, Teva Women’s Health, Inc.) as a single dose and insertion of the LNG 52 mg IUD (Mirena®, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals). Participants obtained their desired EC regimen of choice at no cost. Oral LNG 1.5 mg was administered in the clinic prior to LNG 52 mg IUD insertion. The option to switch methods without charge was not offered. All participants received Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis PCR testing (Gen-Probe Aptima®).

Advanced practice clinicians with IUD insertion experience performed all IUD insertions in accordance with manufacturer directions. Prior to discharge from the clinic, each participant obtained a home urine pregnancy test (Osom® card pregnancy test, Genzyme Diagnostics, human chorionic gonadotropin ≤ 20 IU/L) with instructions to complete the test at home two weeks post-IUD insertion. Phone, text or email prompted participants to access a link to the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure web-based application. Participants entered the results of their two-week pregnancy test and completed a follow-up survey via this link. Participants did not receive any reimbursement beyond chosen EC regimen without charge.

The primary outcome was EC failure for the oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD regimen. EC failure was defined as a pregnancy that was a result of intercourse occurring within five days prior to IUD insertion. Our sample size intention was to include 100 evaluable oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG IUD users in order to create a point estimate and confidence interval for the risk of pregnancy using oral LNG 1.5 mg and the LNG 52 mg IUD for EC. Two methods calculated EC failures: first by using the number of participants contacted at follow up as the denominator and second by assuming all participants lost to follow up had an EC failure. We used the Adjusted Wald method to calculate confidence intervals [12–14] and conducted data analysis utilizing Stata 13 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). We excluded from analysis missing data and data from participants lost to follow up. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Utah approved the study. We followed STROBE guidelines for study design and manuscript preparation.

3. Results

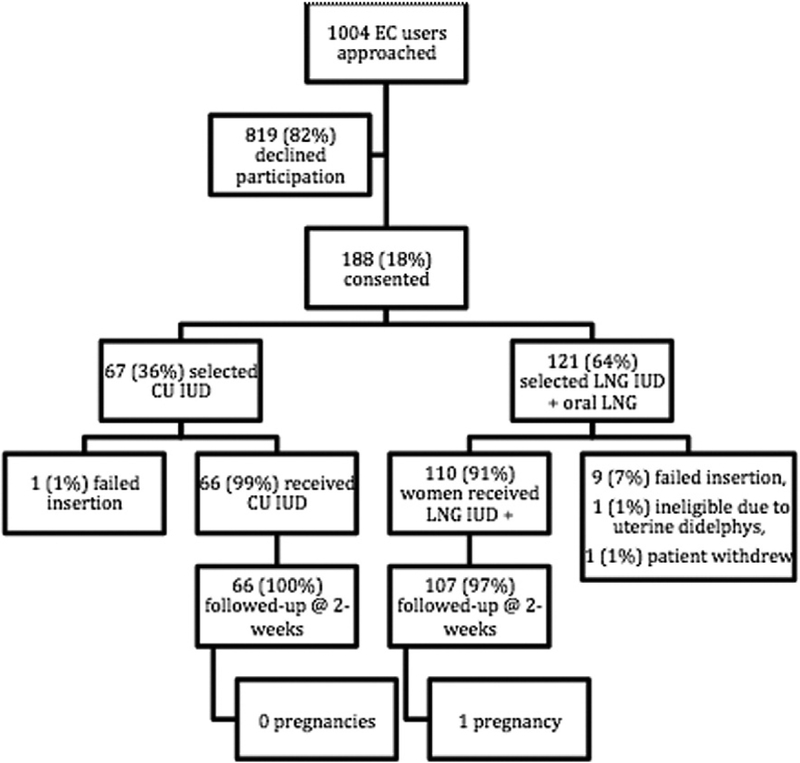

Of the 1004 women presenting for EC during the study time period, 188 women (18%) desired an IUD and enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). Twenty-six percent of women who declined study participation desired only oral EC. Another 27% indicated they were not interested in an IUD. Demographics by treatment group are presented in Table 1. The LNG group had more overweight and obese participants than the copper IUD group (61% vs. 40%, p = .035). Nearly two-thirds of participants (n= 121) chose oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD and one-third (n=67) selected the copper IUD. In the copper IUD group, 66 women received the copper IUD as their EC regimen and one participant had an IUD insertion failure. In the oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD group, one patient withdrew prior to IUD insertion, nine insertions failed, and one participant was excluded as she had a uterine didelphys identified at the time of IUD insertion; thus, 110 women received oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD as their EC regimen. Two-week urine pregnancy test results were available for all of the 66 women who received copper IUDs and 107 of the 110 women who received oral LNG 1.5 mg plus the LNG 52 mg IUD.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow chart and outcomes.EC, emergency contraception; CU copper; IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Copper IUD (n=67) | Oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG IUD(n=121) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age | |||

| 18–24 years old | 40 (60) | 74 (61) | 0.6 |

| 25–34 years old | 25 (37) | 47 (39) | |

| 35+ years old | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| UPI Timing | |||

| <24h | 37 (55) | 64 (53) | 0.99 |

| 24–48 h | 19 (28) | 38 (31) | |

| >48 h | 11 (16) | 19 (16) | |

| #UPI in past 2 weeks | |||

| 1 | 33 (49) | 72 (60) | 0.10 |

| 2 | 12 (18) | 26 (21) | |

| 3 + | 22 (33) | 23 (19) | |

| Days since LMP | 17.1 (SD 8.2) | 16.8 (SD 8.9) | 0.82 |

| Menstrual Cycle Length (days) | 29.4 (SD 2.0) | 28.8 (SD 2.0) | 0.06 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 39 (59) | 71 (60) | 0.56 |

| Hispanic | 19 (29) | 39 (33) | |

| Other | 8 (12) | 9 (7) | |

| Income | |||

| <$24,000 | 49 (74) | 83 (69) | 0.75 |

| $24,000–$47,999 | 14 (21) | 34 (28) | |

| $48,000–$60,000 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| >$60,000 | 2 (3) | 3 (2) | |

| Insurance | |||

| No | 37 (57) | 69 (58) | 0.94 |

| Yes | 28 (43) | 51 (42) | |

| Previous Pregnancy | |||

| No | 35 (52) | 55 (45) | 0.37 |

| Yes | 32 (48) | 66 (55) | |

| Positive STI Screen | 4 (7) | 6 (7) | 0.75 |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight/Normal (< 25 kg/m2) | 38 (60) | 45 (39) | 0.035 |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 15 (24) | 44 (38) | |

| Obese (30+ kg/m2) | 10 (16) | 27 (23) |

IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel; UPI, unprotected intercourse; BMI, body mass index; LMP, last menstrual period; STI, sexually transmitted infection; SD, standard deviation. Percentage totals may not equal 100% due to rounding.

The EC pregnancy rate for both groups was 0%, corresponding 95% confidnece intervals were 0–5.5% for copper IUD users and 0–3.4% for oral LNG 1.5 mg and LNG 52 mg IUD users. The cycle pregnancy rate for the oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD group, based on a single pregnancy reported at three weeks post-intervention was 0.9% (95% CI 0–5.1%). If the three oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD users lost to follow up all had an EC failure then the EC failure rate in this regimen would have been 2.7% (95% 0.5–7.8%).

The pregnant participant used oral EC three times within 14 days of enrolling in the study (all within a single menstrual cycle) and had a negative urine pregnancy test at study enrollment. She did not use her follow up urine pregnancy test correctly at home, and when she presented to clinic twenty days after IUD insertion she was diagnosed with an ectopic pregnancy. This was based on a beta human chorionic gonadotropin level of 18,510 international units and a transvaginal ultrasound showing an empty uterus and an adnexal mass. At the time of laparoscopic salpingectomy, the gestational sac and villi measured 1.8 cm × 1.3 cm × 0.3 cm. These findings suggest that the gestation resulted from intercourse prior to the episode of unprotected intercourse for which the participant presented when she received oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD. Thus, this is not a failure of this EC regimen.

4. Discussion

In this study one in five women presenting for EC desired an IUD. Of those women initiating an IUD at presentation for EC, the majority preferred a regimen of oral LNG 1.5 mg plus the LNG 52 mg IUD over the copper IUD. Women in this study preferentially selected this regimen despite the need for additional medication at time of IUD insertion and counseling that disclosed a potential increased risk of pregnancy compared to the copper IUD regimen.

Large randomized controlled trials of single dose oral LNG 1.5 mg alone for EC report pregnancy rates of 1.5% - 2.6% [15–16]. Pregnancy rates after oral LNG 1.5 mg alone in overweight or obese populations may be as as high as 2.5% and 5.8% respectively [17]; over half of the participants receiving the oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG IUD regimen in this study were overweight or obese. Extrapolating these data to our cohort of 107 oral LNG 1.5 mg EC users, greater than 1 pregnancy would be expected. The inclusion of higher BMI patients in the oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG IUD treatment arm of our study strengthens our findings.

The primary strength of this study lies in the novel investigation of a desired and highly effective method of long acting contraception among women presenting for EC. In addition, nearly half of the participants in our study reported multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse in the prior two weeks and would have been excluded from conventional EC efficacy studies. Inclusion of these high-risk participants provides more realistic pregnancy outcome data and strengthens our findings of low pregnancy rates using the oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD regimen for EC. The low rate of loss to follow-up in the study is an additional strength. If all three oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD users actually had a pregnancy than the resultant EC pregnancy rate of 3.6% would be consistent with previously reported rates for women of this BMI range using oral LNG 1.5 mg alone for EC.

The main study limitation is the lack of power to adequately compare pregnancy proportions between the two regmiens. A further limitation of this study is the small proportion of eligible women who participated. Less than 1 of 5 women approached for the study proceeded with IUD placement though this is higher than previous estimates that 12% of EC users are interested in IUD placement [18–19]. The family planning clinic utilized in this study is a known provider of over-the-counter EC and commonly women presenting for EC expect a rapid transaction, excluding the possibility of a potentially time consuming IUD insertion and study participation. IUD insertion failures are a limitation for implementing this strategy into practice as is the fact that over the counter EC access means that fewer women seeking EC present to clinics where an IUD can be inserted.

Women presenting for EC are at high-risk of future unintended pregnancy and may be interested in initiating highly effective contraception [10,18–20]. Although the copper IUD is the most effective option for patients requesting EC, women utilizing the oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD regmien had a low probability of pregnancy. The combination of oral LNG 1.5 mg plus LNG 52 mg IUD is a reasonable approach to EC and may be more efficacious than oral LNG 1.5 mg alone. When providers utilize EC encounters to meet demand for highly effective contraception, the probability of future unintended pregnancy falls. Prior studies of women presenting for abortion, childbirth, or oral EC administration demonstrate that provision of highly effective methods of contraception, such as an IUD, reduce the probability of subsequent unintended pregnancy [10,21,22]. Oral LNG 1.5 mg alone for EC has not decreased rates of unintended pregnancy. The combination of oral LNG and the LNG IUD may offer a novel approach to increase IUD uptake among women seeking EC, which may ultimately drive down the number of unintended pregnancies and subsequent abortions.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support for REDCap (8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764) NCATS/NIH).

This study was independently funded by the University of Utah Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Division of Family Planning. Use of REDCap provided by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development grant (8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764) NCATS/NIH).

Appendix A. Study handout

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: DKT receives speaking honoraria from Allergan and Medicines360, is a consultant for Bioceptive, and serves on advisory boards for Actavis, Bayer, Pharmanest and Teva. The Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Utah, receives contraceptive clinical trials research funding from Bayer, Bioceptive, Medicines360, Merck, Teva, and Veracept.

Study location: Salt Lake City, UT.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: .

Findings were presented at the Society of Family Planning’s annual North American Forum on Family Planning held in Miami, FL in October 2014.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc.

References

- [1].Raymond EG, Trussell J, Polis CB. Population effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Harper CC, Speidel JJ, Drey EA, Trussell J, Blum M, Darney PD. Copper intrauterine device for emergency contraception: clinical practice among contraceptive providers. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119(Pt 1):220–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dermish AI, Turok DK. The copper intrauterine device for emergency contraception: an opportunity to provide the optimal emergency contraception method and transition to highly effective contraception. Expert Rev Med Devices 2013;10:477–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, Cheng L, Trussell J. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1994–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cheng L, Che Y, Gülmezoglu AM. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD001324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 112: Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2010;115:1100–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cleland K, Raymond EG, Westley E, Trussell J. Emergency contraception review: evidence-based recommendations for clinicians. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2014;57:741–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Corbelli J, Schwarz BE. Emergency contraception: a review. Minerva Ginecol 2014;66:551–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Emergency contraception. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2006;32:121–8 [quiz 128]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Turok DK, Jacobson JC, Dermish AI, Simonsen SE, Gurtcheff S, McFadden M, et al. Emergency contraception with a copper IUD or oral levonorgestrel: an observational study of 1-year pregnancy rates. Contraception 2014;89(3):222–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Penny Davies. Vice president of Clinical Services, planned parenthood association Of Utah. Pers Commun 2016;4. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bonett DG, Price RM. Confidence intervals for a ratio of binomial proportions based on paired data. Stat Med 2006;25:3039–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lewis J, Sauro J. 100% really isn’t 100%: improving the accuracy of small-sample estimates of completion rates. J Usability Stud 2006;1:136–50. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sauro J, Lewis J. Estimating completion rates from small samples using binomial confidence intervals: comparisons and recommendations. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting; Orlando, FL; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, Chen J, Song S, Bártfai G, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2002;360:1803–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, Logan SJS, Casale W, Van Horn J, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:555–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, Scherrer B, Mathe H, Levy D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception 2011;84:363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Turok DK, Gurtcheff SE, Handley E, Simonsen SE, Sok C, North R, et al. A survey of women obtaining emergency contraception: are they interested in using the copper IUD? Contraception 2011;83:441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Schwarz EB, Kavanaugh M, Douglas E, Dubowitz T, Creinin MD. Interest in intrauterine contraception among seekers of emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:833–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rickert VI, Tiezzi L, Lipshutz J, León J, Vaughan RD, Westhoff C. Depo now: preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health 2007;40:22–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:481–e1–7.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bednarek PH, Creinin MD, Reeves MF, Cwiak C, Espey E, Jensen JT, et al. Immediate versus delayed IUD insertion after uterine aspiration. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2208–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]