Key Points

Question

Does providing patients with copayment assistance for P2Y12 inhibitors also have an association with patient persistence in taking other cardiovascular medications?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of the Affordability and Real-World Antiplatelet Treatment Effectiveness After Myocardial Infarction Study (ARTEMIS) cluster-randomized trial, providing copayment assistance for P2Y12 inhibitors significantly increased patient persistence in taking β-blockers and statins in addition to P2Y12 inhibitors but not in taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II–receptor blockers.

Meaning

The association of the P2Y12 inhibitor copayment assistance program evaluated in the ARTEMIS trial with persistence in taking other cardiovascular medications may have important implications important implications for the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of similar programs.

This post hoc secondary analysis of a cluster-randomized trial assesses whether providing copayment reduction for P2Y12 inhibitors increases patient persistence in taking other secondary prevention cardiovascular medications.

Abstract

Importance

The Affordability and Real-World Antiplatelet Treatment Effectiveness After Myocardial Infarction Study (ARTEMIS) cluster-randomized trial found that copayment reduction for P2Y12 inhibitors improved 1-year patient persistence in taking that medication.

Objective

To assess whether providing copayment reduction for P2Y12 inhibitors increases patient persistence in taking other secondary prevention cardiovascular medications.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This post hoc analysis of the ARTEMIS trial includes data from 287 hospitals that enrolled patients between June 2015 and September 2016. Patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction were included. Data analysis occurred from May 2018 through August 2019.

Interventions

Hospitals randomized to the intervention provided patients vouchers that waived copayments for P2Y12 inhibitors fills for 1 year. Hospitals randomized to usual care did not provide study vouchers.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Persistence in taking β-blocker, statin, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker medications at 1 year, defined as the absence of a gap in medication supply of 30 or more days by pharmacy fill data in the intervention-arm (intent-to-treat) population.

Results

A total of 131 hospitals (with 5109 patients) were randomized to the intervention, and 156 hospitals (with 3264 patients) randomized to the control group. Patients discharged from intervention hospitals had higher persistence in taking statins (2247 [46.1%] vs 1300 [41.9%]; adjusted odds ratio, 1.11 [95% CI, 1.00-1.24]), and β-blockers (2235 [47.6%] vs 1277 [42.5%]; odds ratio, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.10-1.38]), although the association was smaller than that seen for P2Y12 inhibitors (odds ratio, 1.47 [95% CI, 1.29-1.66]). Persistence in taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II-receptor blockers were also numerically higher among patients in the intervention arm than in the usual-care arm, but this was not significant after risk adjustment (1520 [43.9%] vs 847 [40.5%]; adjusted odds ratio, 1.10 [95% CI, 0.97-1.24]). Patients in the intervention arm reported greater financial burden associated with medication cost than the patients in the usual-care arm at baseline, but these differences were no longer significant at 1 year.

Conclusions and Relevance

Reducing patient copayments for 1 medication class increased persistence not only to that therapy class but may also have modestly increased persistence to other post–myocardial infarction secondary prevention medications. These findings have important implications for the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of medication cost-assistance programs.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02406677

Introduction

Statins, P2Y12 inhibitors, β-blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi)/angiotensin II–receptor blockers (ARBs) are guideline-recommended secondary prevention therapies for patients after acute myocardial infarction (MI).1,2 Quality-improvement efforts have resulted in the prescription of these secondary prevention medications at the time of discharge to more than 90% of eligible patients with MI3; however, medication use rates fall rapidly after hospital discharge, ranging between 60% and 70% by 90 days and 50% and 60% by 1 year after MI.4,5,6 Medication nonpersistence is a complex behavior that may be affected by many patient, clinician, socioeconomic, and communication factors.7

One driver of long-term medication persistence is patient out-of-pocket costs. The Affordability and Real-World Antiplatelet Treatment Effectiveness After Myocardial Infarction Study (ARTEMIS) cluster-randomized trial found that reducing copayments for P2Y12 inhibitors improved 1-year patient persistence in taking that medication class in patients with MI. Because health services interventions deployed within complex systems can have indirect consequences,8 we evaluated the association of this P2Y12 inhibitor copayment reduction intervention with persistence in taking other secondary prevention medications, specifically statins, β-blockers, and ACEi/ARBs in the first year after MI.

Methods

Study Population

Details of the ARTEMIS study design and primary results have been published previously.9,10 Briefly, the ARTEMIS trial, conducted from June 2015 to September 2016, randomized hospitals to a P2Y12 inhibitor copayment reduction program vs usual care to examine the program’s associations with 1-year medication persistence and clinical outcomes in patients with MI. In both arms, P2Y12 inhibitor selection and treatment duration were determined by the clinical care team. Patients enrolled at intervention hospitals were given a voucher card that could be used at any pharmacy to fill either a generic (clopidogrel) or brand-name (ticagrelor) P2Y12 inhibitor in any prescribed quantity throughout the first year after an MI. Medication refills needed to be initiated by the patient, and the study provided no refill reminders. The voucher did not apply to any other filled medications. Enrolled patients were 18 years or older, diagnosed with MI, discharged taking a P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor), had US-based private or government health insurance coverage with a prescription drug benefit, and were able to provide written informed consent for longitudinal follow-up. Patients with prior intracranial hemorrhage, contraindications to P2Y12 inhibitor therapy at discharge, enrollment in another research study that specified the type and duration of P2Y12 inhibitor in the 1 year after an MI, life expectancy of less than 1 year, or plans to move outside of the United States were excluded.

All patients enrolled in ARTEMIS provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the ethics committee or institutional review board of each participating site and implemented in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The Duke University Medical Center institutional review board approved use of ARTEMIS data for this analysis.

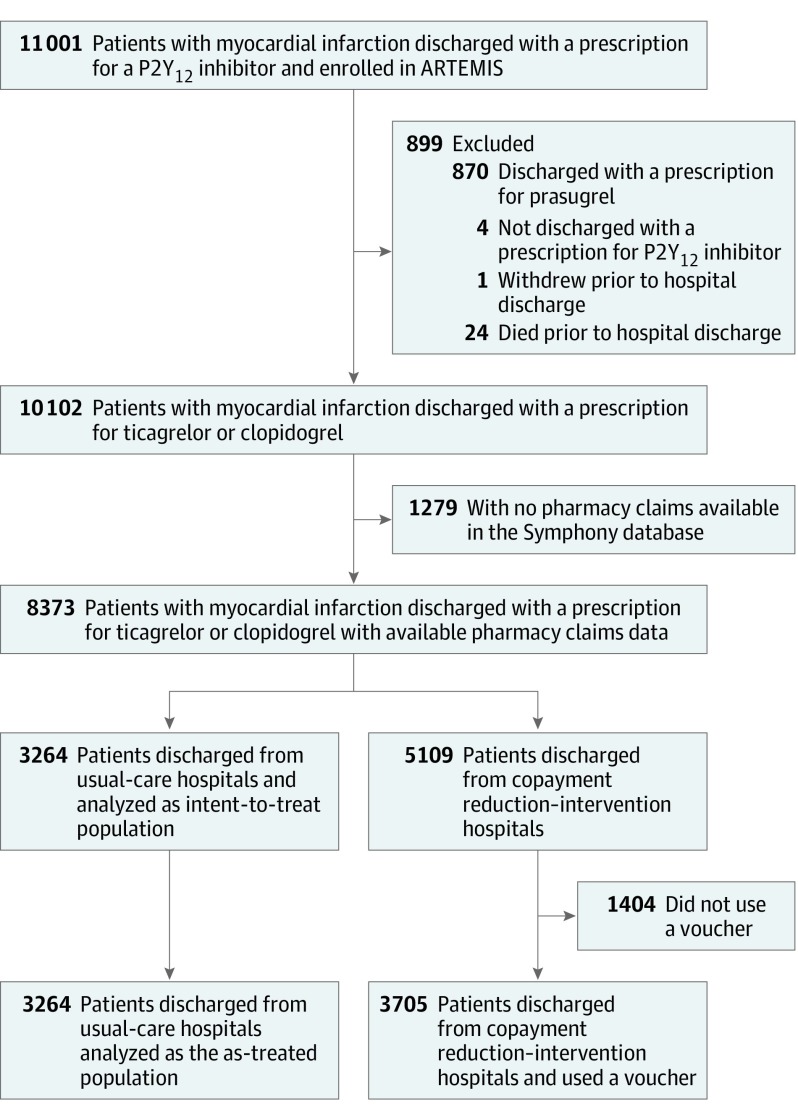

The ARTEMIS trial enrolled 11 001 patients at 287 hospitals. Because our analysis focused on the associations of the copayment reduction intervention with persistence in taking other cardiovascular medications, we excluded patients ineligible for voucher use, including those discharged with a prescription for prasugrel (n = 870), those discharged without a P2Y12 inhibitor (n = 4), those who withdrew prior to discharge (n = 1), and those who died prior to hospital discharge (n = 24). Enrolled patients were linked to Symphony Health (a PRA HealthSciences company) pharmacy data via an anonymous unique identifier to assess medication persistence. This database contains more than 10 billion adjudicated prescription claims for more than 220 million patients in the United States. We excluded patients who did not have 1 or more medication fills (of any prescription) recorded in the Symphony database on or after the date of index discharge (n = 1729). The final analysis population included 8373 patients at 287 hospitals (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the study population and the population excluded because of a lack of Symphony Health data are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

ARTEMIS indicates Affordability and Real-World Antiplatelet Treatment Effectiveness After Myocardial Infarction Study.

Data Definitions

The primary outcome of this analysis was persistence to secondary prevention medications, defined as continuous fill without a gap of 30 or more days in supply from the time of discharge after the index MI, in the intent-to-treat population. Any patient with a gap in supply of more than 30 days was defined as nonpersistent, as were patients who never filled a prescription for a given medication. We also evaluated medication adherence as a secondary outcome measure, defined as a proportion of days covered with a supply of medication over the 1-year follow-up of 80% or more. We determined each patient’s persistence and adherence to statins, β-blockers, and ACEi or ARBs. Persistence to P2Y12 inhibitor was examined previously, and 1-year adherence was calculated for P2Y12 inhibitors.10

At baseline and 1 year postdischarge, patients were asked about financial hardship affecting their affording medications, the likelihood of not filling a prescription because of cost, out-of-pocket prescription fill expenses, and any difficulty getting medical care to evaluate the outcome of the intervention on patient-reported outcomes. (The questions are shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics are reported for patients discharged from intervention and usual-care hospitals. Descriptive statistics are reported as median (interquartile ranges [IQRs]) for continuous variables and frequency (and percentages) for categorical variables. Differences between groups were compared by calculating standardized differences.

Because of the cluster-randomized design of the ARTEMIS trial, there were baseline imbalances between patients enrolled at the intervention and usual-care sites, so analyses of medication persistence and adherence were conducted using multivariable analysis with generalized estimating equations to account for within-hospital clustering and adjustment for selected characteristics, including a propensity score for intervention. Intraclass correlation coefficients are shown in eTable 3 in the Supplement. The propensity score was estimated using a logistic regression model for intervention. It was calculated at the patient level and represents the propensity that a given patient would be treated at a hospital that was randomized to the intervention arm. Covariates for adjustment in the propensity model were selected based on expert opinion and included hospital characteristics, demographic information, comorbidities, details of the index presentation and hospital course, and patient responses to baseline survey questions about quality of life and medication-taking behaviors (eMethods in the Supplement for a full list of variables used to calculate the propensity score). After inverse propensity weighting, 65 of 68 variables had good balance between the intervention and usual-care arms as indicated by standardized differences less than 0.10 (eTable 4 in the Supplement). In persistence and adherence models, we adjusted for intervention; randomization scheme (2: 1 [intervention: usual care] vs 1:1); hospital MI volume of 400 or more; hospital-reported ticagrelor use before ARTEMIS of 15% or more; patient age, sex, race, and insurance type; region; and propensity for intervention. For all analyses, we report odds ratios (ORs) with associated 95% CIs for persistence to secondary prevention medications among patients discharged from intervention hospitals, with usual-care hospitals as the reference. An OR of more than 1.00 indicates greater odds of persistence among patients discharged from an intervention hospital. We repeated these analyses for the secondary outcome of 1-year adherence. In sensitivity analyses, we repeated these comparisons in 3705 patients (72.5%) in the intervention arm who used the provided study voucher.

To identify potential reasons for an association of the P2Y12 inhibitor copayment assistance voucher with persistence and adherence to other cardiovascular medications, we tested 2 main hypotheses: (1) the copayment intervention reduced patients’ financial burden for 1 medication, enabling them to spend some or all of those savings on other necessary medications while maintaining the same or smaller overall financial burden; and (2) the copayment intervention motivated patients to go to their pharmacy to fill the covered P2Y12 inhibitor, and they filled prescriptions for other secondary prevention medications concurrently. To test the first hypothesis, we compared the proportion of patients reporting financial hardship in affording medications and not filling prescriptions because of cost between intervention and control arms at baseline and then again at 1 year. We also compared patient-reported out-of-pocket money spent to fill all prescriptions (including P2Y12 inhibitor, other secondary prevention medications, and other cardiovascular and noncardiovascular medications) between the intervention and control arms at baseline and 1 year, as well as actual monthly out-of-pocket expenditures on all prescription medications over the course of the study. To test the second hypothesis, we counted the number of prescriptions for cardiac medications other than P2Y12 inhibitors (statins, β-blockers, and ACEi/ARBs) filled on the same day as a P2Y12 inhibitor prescription and compared the results between the intervention and control arms. We then divided patients into 2 cohorts: those who ever filled a cardiac medication prescription at the same time as a P2Y12 inhibitor prescription and those who did not. We compared persistence and adherence for patients discharged from intervention and usual-care hospitals separately among these 2 cohorts and tested the interaction between persistence, the intervention, and whether a patient ever filled a cardiac medication at the same time as a P2Y12 inhibitor.

All statistical analyses, except as noted, were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All statistical tests were 2-sided, with a significance level of .05.

Results

Of the 8373 patients included in this analysis, 5109 patients (61.0%) were enrolled at 131 hospitals randomized to the P2Y12 inhibitor copayment reduction intervention, and 3264 patients (39.0%) were enrolled at 156 hospitals randomized to usual care. Patients discharged from usual-care hospitals and intervention hospitals were similar in age (median [IQR] age, 62 [54-70] years) and had similar proportions of patients with private health insurance (Table). Patients discharged from intervention hospitals were more frequently white (4559 [89.2%] vs 2823 [86.5%]) but less often had a college or higher degree (2401 [47.0%] vs 1679 [51.4%]), and more often reported difficulty obtaining medical care (2484 [48.6%] vs 1411 [43.3%]) and financial hardship in filling medications (2573 [57.0%] vs 1466 [49.1%]).

Table. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Copayment Reduction Intervention (n = 5109) | Usual Care (n = 3264) | Standardized Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic | |||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 62 (54-70) | 62 (54-70) | −0.01 |

| Male | 3470 (67.9) | 2194 (67.2) | 0.01 |

| Nonwhite race | 550 (10.8) | 441 (13.5) | 0.08 |

| Private health insurance | 3237 (63.4) | 2113 (64.7) | −0.03 |

| Employed | 2386 (46.7) | 1475 (45.2) | 0.06 |

| College degree or higher | 2401 (47.0) | 1679 (51.4) | −0.09 |

| Low health literacy | 744 (14.6) | 428 (13.1) | 0.04 |

| Self-reported difficulty getting medical care | 2484 (48.6) | 1411 (43.3) | 0.12 |

| Financial hardship paying for medications | |||

| Extreme/moderate | 960 (18.8) | 527 (16.2) | 0.16 |

| Some/low | 1613 (31.6) | 939 (28.8) | |

| None | 1942 (38.0) | 1518 (46.5) | |

| Missed >1 dose of medication in last month because of cost | 1240 (24.3) | 930 (28.5) | −0.09 |

| Medical history | |||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1000 (19.6) | 713 (21.8) | −0.06 |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 1249 (24.5) | 874 (26.8) | −0.05 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass graft | 533 (10.4) | 392 (12.0) | −0.05 |

| Prior stroke or transient ischemic attack | 310 (6.1) | 240 (7.4) | −0.05 |

| Prior heart failure | 357 (7.0) | 292 (9.0) | −0.07 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 288 (5.6) | 231 (7.1) | −0.06 |

| Chronic kidney disease with dialysis | 87 (1.7) | 69 (2.1) | −0.03 |

| Diabetes | 1628 (31.9) | 1105 (33.9) | −0.04 |

| Current or recent smoker | 1744 (34.1) | 1063 (32.6) | 0.03 |

| Weight, median (IQR), kg | 89 (77-104) | 89 (77-104) | 0.00 |

| In-hospital characteristics | |||

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 2377 (46.5) | 1470 (45.0) | 0.03 |

| Multivessel disease | 2403 (47.0) | 1465 (44.9) | 0.02 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 4615 (90.3) | 2852 (87.4) | 0.09 |

| Drug-eluting stent | 4210 (91.2) | 2517 (88.3) | 0.10 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 77 (1.5) | 48 (1.5) | 0.00 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Persistence and Adherence at Intervention vs Usual-Care Hospitals

At intervention hospitals, 2820 patients (55.2%) were persistent in receiving P2Y12 inhibitor therapy over the 1 year after their index MI, compared with 1511 patients (46.3%) at usual-care hospitals. After multivariable adjustment, patients discharged from intervention hospitals remained more likely to be persistent in receiving P2Y12 inhibitor therapy (odds ratio [OR], 1.47 [95% CI, 1.29-1.66]) than those discharged from usual-care hospitals. The median percentage of days covered with a P2Y12 inhibitor was 90.1% (IQR, 49%-98%) for patients discharged from intervention hospitals, compared with 82.2% (95% CI, 25%-98%) for those discharged from usual-care hospitals, and 3078 patients (60.3%) in intervention hospitals were adherent to P2Y12 inhibitors at 1 year vs 1695 patients (51.9%) in usual-care hospitals. After adjustment, patients discharged from intervention hospitals were more likely to be adherent to P2Y12 inhibitor therapy than those discharged from usual-care hospitals (OR, 1.40 [95% CI, 1.23-1.59]).

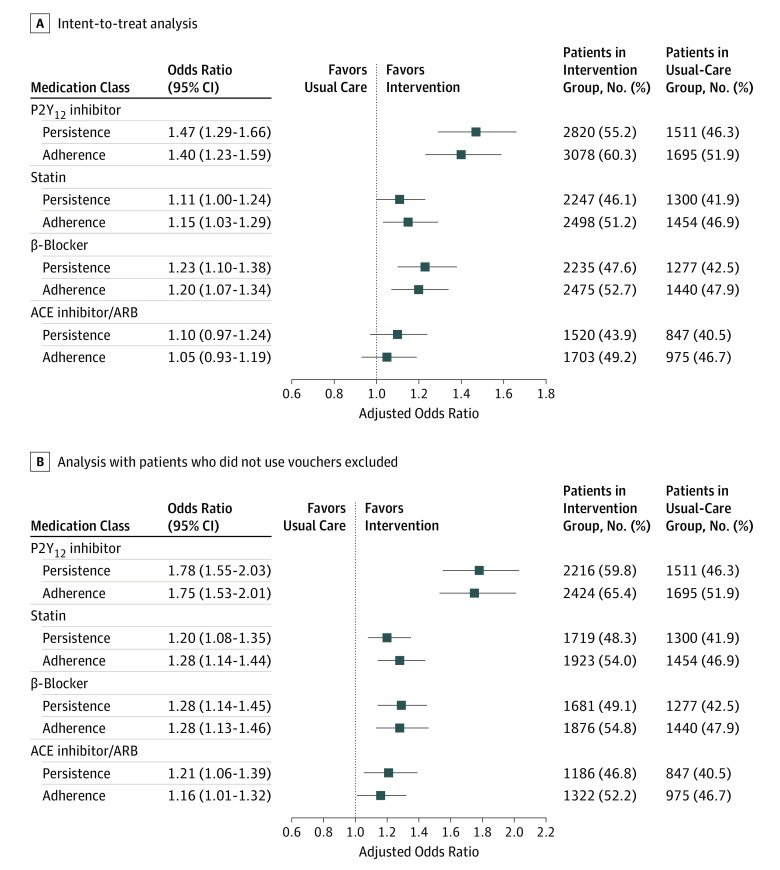

Patients discharged from intervention hospitals were more often persistent in taking statins (2247 [46.1%] vs 1300 [41.9%]; P < .001), β-blockers (2235 [47.6%] vs 1277 [42.5%]; P < .001), and ACEi or ARBs (1520 [43.9%] vs 847 [40.5%]; P = .01) than those discharged from usual-care hospitals over the 1 year after their index MI (Figure 2A). They were also more often adherent to all 3 classes of medications. After risk adjustment, patients in intervention hospitals had significantly higher persistence and adherence to β-blockers and statins (P = .05 for statins; P < .001 for β-blockers), but while the differences were directionally higher for ACEi/ARBs, they were not statistically significant.

Figure 2. Adjusted Associations Between P2Y12 Inhibitor Copayment Reduction Intervention and Persistence and Adherence to Secondary Prevention Medications.

Patients in the intervention arm had higher rates of persistence and adherence to non–P2Y12 inhibitor secondary prevention medications than the usual-care arm in both the intent-to-treat and as-treated arms. Results for the intent-to-treat population (A) and with patients who did not use vouchers excluded (B); the outcome of the intervention was greater when those who did not use vouchers were excluded. Variables for adjustment included hospital characteristics, demographic information, comorbidities, details of the index presentation and hospital course, and patient responses to baseline survey questions about quality of life and medication-taking behaviors. ACE indicates antiotengin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotension II–receptor blocker.

Among patients discharged from intervention hospitals, 3705 (72.5%) used the copayment assistance voucher at least once. Compared with patients in the usual-care group, these patients were significantly more often persistent in taking P2Y12 inhibitors (2216 [59.8%] vs 1511 [46.3%]; P < .001), statins (1719 [48.3%] vs 1300 [41.9%]; P < .001), β-blockers (1681 [49.1%] vs 1277 [42.5%]; P < .001), and ACEi/ARBs (1186 [46.8%] vs 847 [40.5%]; P < .001); these differences persisted after risk adjustment (Figure 2B). Patients were also more likely to be adherent to these classes of medications.

Potential Explanations for the Observed Association

To evaluate whether the observed association between the P2Y12 inhibitor copayment intervention and persistence in taking other secondary prevention medications may be influenced by reduced financial burden in patients in the copayment intervention group, leading to better ability to afford other cardiovascular medications, we examined patient survey responses. At baseline, 960 patients in the intervention arm (21.3%) reported moderate or extreme financial hardship in affording medications, compared with 527 patients in the usual-care arm (17.2%; P < .001). At 1 year, there was no difference between the 2 groups in the proportion of patients reporting moderate or extreme financial hardship (486 [10.1%] vs 306 [10.3%]; P = .77); 611 patients (14.4%) in the intervention arm reported less financial hardship at 1 year than at baseline, compared with 305 in the usual-care arm (11.2%; P < .001). Additionally, at baseline, 1088 patients (18.4%) in the intervention arm reported not filling a prescription because of expense, compared with 641 patients (16.6%) in the control arm (P = .02); this difference was no longer significant at 1 year (377 [7.7%] vs 244 [8.1%]; P = .55). Patient-reported out-of-pocket medication costs were similar between the 2 groups at baseline: overall, 1259 (12.9%) reported no out-of-pocket costs, 3620 (37.1%) reported $1 to $49 per month, 1858 (19.1%) reported $50 to $99 per month, 2176 (22.3%) reported $100 or more per month, and 834 (8.6%) did not know (eTable 5 in the Supplement; P = .85 for difference between groups). At 1 year, there remained no significant differences between the groups in reported out-of-pocket costs. Over the course of the study period, patients in the intervention arm had higher median (IQR) monthly out-of-pocket spending for all filled prescriptions than patients receiving usual care (median [IQR], $26.99 [$9.46-$62.12] vs $24.36 [$7.78-$55.21]; P < .001).

At baseline, patients in the intervention arm more often reported difficulty getting medical care than patients in the usual-care arm (2484 [48.6%] vs 1411 [43.3%]; P < .001). However, the difference between the 2 groups was no longer significant at 1 year.

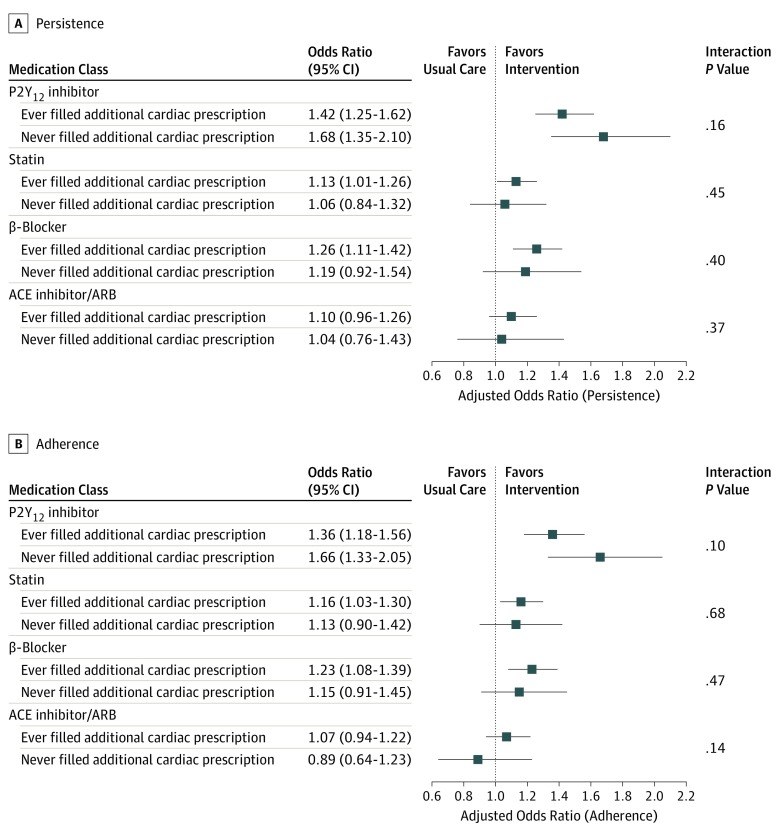

To evaluate whether the P2Y12 inhibitor copayment reduction intervention increased persistence and adherence to other medications owing at least in part to patients filling their other secondary prevention medications concurrently with their P2Y12 inhibitor fill, we examined the proportion of fills of other cardiovascular medications on the same day as P2Y12 inhibitor fills. Patients in the intervention arm filled P2Y12 inhibitor prescriptions 40 792 times during the study period; among these, 17 655 (43.3%) had a concurrent fill of at least 1 other secondary prevention medication. In contrast, among 22 695 P2Y12 inhibitor prescriptions for patients in the usual-care arm during the study period, 10 725 (47.3%) had a concurrent fill of at least 1 other secondary prevention medication (P < .001).

On the patient level, 3844 of 4715 patients (81.5%) in the copayment intervention arm ever concurrently filled a prescription for an additional cardiac medication on the same date as they filled their P2Y12 inhibitor, compared with 2424 of 2928 patients (82.8%) in the usual-care arm (P = .16). The association between the P2Y12 inhibitor copayment intervention and persistence with statins, β-blockers, and ACEi/ARBs remained similar regardless of whether the patient ever concurrently filled another cardiac medication at the same time as their P2Y12 inhibitor prescription (Figure 3). Results were similar for adherence.

Figure 3. Adjusted Associations Between P2Y12 Inhibitor Copayment Reduction Intervention and Persistence and Adherence to Secondary Prevention Medications Among Patients Who Had Ever and Never Filled an Additional Cardiac Medication Prescription on the Same Day as a P2Y12 Inhibitor Prescription.

There was no interaction observed between whether a patient had ever filled a non–P2Y12 inhibitor secondary prevention medication at the same time as a P2Y12 inhibitor and the observed association with persistence (A) or adherence (B) in taking other cardiovascular medications. Variables for adjustment included hospital characteristics, demographic information, comorbidities, details of the index presentation and hospital course, and patient responses to baseline survey questions about quality of life and medication-taking behaviors. ACE indicates antiotengin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotension II–receptor blocker.

Discussion

In this analysis of data from the ARTEMIS randomized clinical trial, we found that a P2Y12 inhibitor copayment reduction intervention may have had an association with persistence in taking other cardiovascular medications, in that patients discharged from intervention hospitals had greater persistence and adherence to statins and β-blockers, in addition to P2Y12 inhibitors, compared with patients in the usual-care arm. The change in patients’ self-reported ability to afford medications at follow-up vs baseline suggests that the intervention may have eased copayment burden among patients in the intervention arm, thus permitting broader medication adherence and persistence. Although the observed association with persistence in taking other cardiovascular medications was modest, persistence and adherence are complex and challenging problems that affect many patients, with important consequences for key health outcomes, and even modest improvements may be important.

Changes in health care delivery or payment commonly have indirect consequences. For example, Medicaid expansion in the United States, a policy aimed at increasing insurance coverage for adults with low incomes, also increased use of preventive services for children of adults with low incomes.10 The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program penalized hospitals for readmissions after total hip and knee replacements, but readmissions declined both for penalized procedures and nonpenalized procedures after the start of the program.11 In this study, we observed an association with adherence and persistence in taking non–P2Y12 inhibitor secondary prevention cardiovascular medications in a randomized clinical trial of copayment assistance for P2Y12 inhibitors.

The most likely explanation for the association of the P2Y12 inhibitor copayment reduction intervention with persistence and adherence to other cardiovascular medications is that it reduced patients’ overall financial burden. At baseline, patients in the intervention arm more often reported financial hardship of paying for medications, not filling a prescription because of expense, and difficulty accessing medical care than those enrolled at usual-care hospitals. Over the course of the study period, differences between patients in the intervention and usual-care groups in financial hardship and access to care measures diminished, suggesting that the copayment intervention successfully reduced the burden of paying for P2Y12 inhibitors, particularly for nongeneric medications with higher out-of-pocket costs. With some of that burden removed, patients receiving the intervention may have felt better able to afford other cardiovascular medications, increasing adherence and persistence. They may also have had more financial resources to access health care and ensure continued medication prescription and counseling on adherence. The larger observed association in the subset of patients in the intervention arm who actually used the provided voucher also argues in favor of reduced financial burden as a potential cause of the results.

A second possibility is that the P2Y12 inhibitor copayment assistance vouchers prompted patients to visit the pharmacy to fill their P2Y12 inhibitor prescription, and they filled their other cardiovascular medications at the same time. While the copayment intervention showed a numerically greater association with persistence and adherence to non–P2Y12 inhibitor secondary prevention medications in patients who ever filled a prescription for one of these medications on the same date as a P2Y12 inhibitor prescription, the differences were not significant, suggesting that this mechanism had only a limited role in driving the observed outcome.

The observed association between the copayment of the ARTEMIS trial and persistence in taking other medications was not observed in the Post-Myocardial Infarction Free Rx Event and Economic Evaluation (MI FREEE) trial, in which patients who had had an MI were randomized to either usual care or to a waiver of copayments for statins, β-blockers, and ACEi/ARBs.12 Although patients in the intervention arm were more likely to adhere to the included cardiovascular medications, they were not more likely to adhere to other medication classes, including clopidogrel and oral hypoglycemic agents.12 In MI FREEE, clopidogrel was only available in branded form, with a high copayment for many patients. The waived copayments in MI FREEE may not have lifted financial burden sufficiently to affect adherence to a more expensive medication, as statins, β-blockers, and ACEi/ARBs were mostly generic medications with very low copayments.

When designing financial incentives to encourage adherence and persistence to medications, policy makers and health services researchers should consider potential indirect consequences, as well as mechanisms by which these consequences are likely mediated. For example, reminding patients of the cost savings from a copayment intervention voucher may encourage them to use those savings on other medications. More broadly, although we observed a positive indirect consequence in this analysis of ARTEMIS, indirect consequences can be positive or negative13,14,15,16 and may affect the overall effectiveness of a health services intervention, reinforcing the need for rigorous testing of these interventions before widespread implementation.17

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, ARTEMIS was a cluster-randomized clinical trial with anticipated imbalances in enrollment and patient characteristics between the intervention and usual-care hospitals. Although analyses were adjusted for numerous variables, unmeasured confounding remains likely. Second, persistence and adherence to secondary prevention medications were assessed by means of pharmacy fill data. Although the data source captures pharmacy fill data from more than 90% of US prescription fills, and baseline characteristics for patients excluded because of the lack of pharmacy fill data were similar to those for patients included in the study population, the data source does not capture all pharmacy transactions, does not include samples distributed in physician offices, and does not confirm that patients actually consumed the medications they received.

Conclusions

A copayment reduction intervention for P2Y12 inhibitors also modestly increased persistence and adherence to statins and β-blockers, even though these medication classes were not directly targeted by the intervention. The mechanism of the observed association with persistence in taking other cardiovascular medications may be attributable to reduction of patients’ overall subjective financial burden.

eMethods. Covariates included in the propensity model to determine likelihood of intervention

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population and the population excluded due to lack of Symphony Health data

eTable 2. Survey questions about financial hardship affording medications, likelihood of not filling a prescription due to cost, and difficulty getting medical care

eTable 3. Adjusted intracluster correlation coefficients for persistence and adherence analyses

eTable 4. Standardized differences between intervention and usual care arm patients after inverse probability weighting on variables included in the propensity model

eTable 5. Patient reported out of pocket costs

References

- 1.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127(4):e362-e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742c84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139-e228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masoudi FA, Ponirakis A, de Lemos JA, et al. Trends in US cardiovascular care: 2016 report from 4 ACC national cardiovascular data registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):1427-1450. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathews R, Wang TY, Honeycutt E, et al. ; TRANSLATE-ACS Study Investigators . Persistence with secondary prevention medications after acute myocardial infarction: insights from the translate-ACS study. Am Heart J. 2015;170:62-69. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathews R, Wang W, Kaltenbach LA, et al. Hospital variation in adherence rates to secondary prevention medications and the implications on quality. Circulation. 2018;137(20):2128-2138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doll JA, Hellkamp AS, Goyal A, Sutton NR, Peterson ED, Wang TY. Treatment, outcomes, and adherence to medication regimens among dual Medicare-Medicaid–eligible adults with myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(7):787-794. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baroletti S, Dell’Orfano H. Medication adherence in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2010;121(12):1455-1458. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.904003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joynt KE, Chan D, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Insurance expansion in Massachusetts did not reduce access among previously insured Medicare patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(3):571-578. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doll JA, Wang TY, Choudhry NK, et al. Rationale and design of the Affordability and Real-World Antiplatelet Treatment Effectiveness after Myocardial Infarction Study (ARTEMIS): a multicenter, cluster-randomized trial of P2Y12 receptor inhibitor copayment reduction after myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2016;177:33-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang TY, Kaltenbach LA, Cannon CP, et al. Effect of medication co-payment vouchers on P2Y12 inhibitor use and major adverse cardiovascular events among patients with myocardial infarction: the ARTEMIS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(1):44-55. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim AM, Nathan H, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Impact of the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program on surgical readmissions among medicare beneficiaries. Ann Surg. 2017;266(4):617-624. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Glynn RJ, et al. ; Post-Myocardial Infarction Free Rx Event and Economic Evaluation (MI FREEE) Trial . Full coverage for preventive medications after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2088-2097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1107913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srinivasan M, Pooler JA. Cost-related medication nonadherence for older adults participating in snap, 2013-2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):224-230. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valuck RJ, Libby AM, Orton HD, Morrato EH, Allen R, Baldessarini RJ. Spillover effects on treatment of adult depression in primary care after FDA advisory on risk of pediatric suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1198-1205. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakdawalla D, Sood N, Gu Q. Pharmaceutical advertising and medicare part d. J Health Econ. 2013;32(6):1356-1367. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miettinen J, Malila N, Hakama M, Pitkäniemi J. Spillover improved survival in non-invited patients of the colorectal cancer screening programme. J Med Screen. 2018;25(3):134-140. doi: 10.1177/0969141317718220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadhera RK, Bhatt DL. Toward precision policy—the case of cardiovascular care. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(23):2193-2195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1806260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Covariates included in the propensity model to determine likelihood of intervention

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population and the population excluded due to lack of Symphony Health data

eTable 2. Survey questions about financial hardship affording medications, likelihood of not filling a prescription due to cost, and difficulty getting medical care

eTable 3. Adjusted intracluster correlation coefficients for persistence and adherence analyses

eTable 4. Standardized differences between intervention and usual care arm patients after inverse probability weighting on variables included in the propensity model

eTable 5. Patient reported out of pocket costs