This study surveyed patients with chronic heart failure to better understand their experiences and perceptions of living with heart failure, including their familiarity and concerns with important guideline-directed medical therapies.

Key Points

Question

What are patient perceptions and priorities while living with heart failure (HF) and when choosing therapies for HF?

Findings

In this survey study of 429 patients with HF, respondents reported functioning independently, reducing morbidity/mortality, and minimizing HF symptoms as their most important priorities. Most survey responders reported familiarity with β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and diuretics; less than 25% reported familiarity with angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists.

Meaning

Many patients are not familiar with guideline-directed medical therapies for HF and/or question the safety and effectiveness of therapy, and these findings may significantly contribute to underutilization of guideline-directed medical therapies observed in prior studies.

Abstract

Importance

There are major gaps in use of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for patients with heart failure (HF). Patient-reported data outlining patient goals and preferences associated with GDMT are not available.

Objective

To survey patients with chronic HF to better understand their experiences and perceptions of living with HF, including their familiarity and concerns with important GDMT therapies.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Study participants were recruited from the GfK KnowledgePanel, a probability-sampled online panel representative of the US adult population. English-speaking adults who met the following criteria were eligible if they were (1) previously told by a physician that they had HF; (2) currently taking medications for HF; and (3) had no history of left ventricular assist device or cardiac transplant. Data were collected between October and November 2018. Analysis began in December 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The survey included 4 primary domains: (1) relative importance of disease-related goals, (2) challenges associated with living with HF, (3) decision-making process associated with HF medication use, and (4) awareness and concerns about available HF medications.

Results

Of 30 707 KnowledgePanel members who received the initial survey, 15 091 (49.1%) completed the screening questions, 440 were eligible and began the survey, and 429 completed the survey. The median (interquartile range) age was 68 (60-75) years and most were white (320 [74.6%]), male (304 [70.9%]), and had at least a high school education (409 [95.3%]). Most survey responders reported familiarity with β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and diuretics. Overall, 107 (24.9%) reported familiarity with angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Overall, 136 patients (42.5%) reported have safety concerns regarding angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, and 133 (38.5%) regarding β-blockers, 35 (37.9%) regarding mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, 38 (36.5%) regarding angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors, and 123 (37.2%) regarding diuretics. Between 27.7% (n = 26) and 38.5% (n = 136) reported concerns regarding the effectiveness of β-blockers, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, or diuretics, while 41% (n = 132) were concerned with the effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this survey study, many patients were not familiar with GDMT for HF, with familiarity lowest for angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Among patients not familiar with these therapies, significant proportions questioned their effectiveness and/or safety. Enhanced patient education and shared decision-making support may be effective strategies to improve the uptake of GDMT for HF in US clinical practice.

Introduction

Health-related quality of life for patients with heart failure (HF) is markedly reduced compared with other chronic diseases.1,2 In addition to reducing mortality and preventing hospitalization, therapeutic goals for patients with HF include reducing symptom burden and improving health-related quality of life. Based on large randomized clinical trials demonstrating substantial reductions in hospitalization and death, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) have historically been cornerstone therapies for HF. More recently, the PARADIGM-HF (Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) trial3,4 demonstrated significant reductions in mortality and hospitalization with use of combination sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril. The trial also showed that sacubitril/valsartan was effective in improving health-related quality of life as measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire among patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction.

Despite quality improvement efforts and consensus guideline recommendations, there remain large treatment gaps in the use and dosing of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction. Although the reasons underlying these treatment gaps are multifactorial, data from the CHAMP-HF (Change the Management of Patients with Heart Failure) registry5,6 found patient decisions and preferences to be common reasons for initiation, discontinuation, and dosing changes of GDMT. Unfortunately, detailed patient-reported data outlining the specific patient goals and preferences driving such medication decisions were not available.5,6,7,8,9

In this context, improved understanding of patient perceptions regarding HF and patient-specific treatment goals of HF therapy may identify gaps in patient-centered care and improve use of GDMT for HF. The objective of this study was to survey patients with chronic HF to better understand their experiences and perceptions of living with HF, including their familiarity and concerns with important HF therapies.

Methods

Setting and Participants

We used the GfK KnowledgePanel (GfK Custom Research North America), a probability-based online panel of adults 18 years or older that is designed to be representative of the noninstitutionalized civilian US population.10,11,12,13 The KnowledgePanel comprises approximately 55 000 active panel members recruited through a combination of probability-based, random-digit dialing and address-based sampling to create a nationally representative panel covering 97% of US households. Participants were eligible if they were 18 years or older, self-reported as having been diagnosed with HF (irrespective of ejection fraction), and taking HF medications. For practical purposes, we did not expect patients to know or be able to report their ejection fraction, and therefore patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction were invited to participate. Patients with a history of durable left ventricular assist device implantation or cardiac transplant were not eligible. Hence, the survey consisted of 2 stages: initial screening to determine if participants qualified for the study, followed by the main survey with the study-eligible respondents. Data were collected between October and November 2018. This study was approved by the Duke University Health System institutional review board. Patients who participated in the focus group sessions provided written informed consent. Survey respondents were identified and solicited by the GfK KnowledgePanel. GfK emailed KnowledgePanel members who received a digital invitation and consent via email, and completion was required prior to having access to the survey. Analysis began December 2018.

Survey Development

From June through August 2017, 4 focus groups (2 in-person groups and 2 telephone groups) were conducted with 18 people with HF. The objective of these focus groups was to inform development of a quantitative survey regarding patient goals priorities, experience with disease, and the decision-making process about new HF therapies. The focus group participants were recruited from the Duke University Department of Medicine’s Division of Cardiology and represented a diverse set of patients with HF in terms of age, sex, HF etiology, and severity.

Each focus group lasted approximately 90 minutes and was conducted by a professional focus group moderator. Saturation of data, defined as the point at which no new themes were emerging, was reached by the completion of the fourth focus group. Key focus group themes included HF challenges and goals, the decision-making process regarding therapies, and gaps with the current medications used to treat HF. Focus group findings were interpreted and synthesized by a group of cardiologists, epidemiologists, and qualitative researchers to generate draft survey questions. These questions were reviewed for face validity and revised by a GfK survey methodologist prior to deployment.

The full survey is provided in the eAppendix in the Supplement. The survey included 4 primary domains: (1) relative importance of disease-related personal goals, (2) challenges related to living with HF, (3) decision-making process related to HF medication use, and (4) awareness and concerns about available HF medications. For patients with defibrillators, an additional domain to characterize the decision-making process related to device use was included. Most questions included multiple items with Likert-type scale responses. Two questions on general perceptions of HF were structured as multiple choice.

Statistical Analysis

Simple descriptive statistics from the unweighted sample were used to describe participant characteristics. To analyze the main survey items, we used sampling weights and estimation of sampling errors accounting for the complex sample design so that weighted statistics calculated from the survey sample data could be applied to the target population. Proportion and 95% CIs were computed for each response option of each item. Means with 95% CI were also reported for items with Likert-type scale responses, where 1 indicated much less important; 2, somewhat less important; 3, about as important; 4, somewhat more important; and 5, much more important or 1 indicating not important; 2, somewhat important; 3, very important; and 4, extremely important. Stacked bar plots were used to visualize factor importance or prevalence ranked within each domain or main question, while simple bar plots of the positive response were used for domains with dichotomous scale items.

We explored the association between selected survey outcomes of interest and patient characteristics including sex, age (≥65 years vs <65 years), and household income (lower vs higher [<$60 000 vs ≥$60 000]). Survey domain analysis was conducted to estimate subpopulation means and to construct the 95% CIs. Nonoverlapping CIs indicate statistically significant difference between groups being compared.

Patient familiarity was defined for each medication class as a yes answer to the question “Have you ever heard of (medication class with common generic and brand name examples).” Patient familiarity is reported as a proportion of survey responders.

Because of the exploratory nature of this study, we did not perform any statistical hypothesis tests. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Survey Participants

Overall, 30 707 KnowledgePanel members were randomly sampled to receive the survey via email and 15 091 (49.1%) completed the survey screening questions. Of those screened, 440 met eligibility criteria and qualified for the study. Of those 440 participants who completed the main survey, 11 participants were excluded owing to speeding through the survey or refusing to answer 25% or more of the substantive survey questions. Following these exclusions, data from 429 individuals were included in the final analysis. The median (interquartile range) age was 68 years (60-75 years), most participants were married (265 [61.8%]), white (320 [74.6%]), or men (304 [70.9%]), had at least a high school graduate’s degree or equivalent (409 [95.3%]), owned their own home (335 [78.1%]), and were retired (259 [60.4%]) (Table).

Table. Baseline Characteristics of Survey Responders.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| 18-29 | 4 (0.9) |

| 30-44 | 17 (4.0) |

| 45-59 | 79 (18.4) |

| ≥60 | 329 (76.7) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 304 (70.9) |

| Female | 125 (29.1) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 20 (4.7) |

| High school | 113 (26.3) |

| Some college | 163 (38.0) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 133 (31.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | |

| White | 320 (74.6) |

| Black | 42 (9.8) |

| Other | 6 (1.4) |

| ≥2 Races | 18 (4.2) |

| Hispanic | 43 (10.0) |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 67 (15.6) |

| Midwest | 110 (25.6) |

| South | 166 (38.7) |

| West | 86 (20.0) |

| Current employment | |

| Working | |

| As a paid employee | 93 (21.7) |

| Self-employed | 30 (7.0) |

| Not working | |

| On temporary layoff from a job | 1 (0.2) |

| Looking for work | 6 (1.4) |

| Retired | 259 (60.4) |

| Disabled | 36 (8.4) |

| Other | 4 (0.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 265 (61.8) |

| Widowed | 40 (9.3) |

| Divorced | 73 (17.0) |

| Separated | 5 (1.2) |

| Never married | 38 (8.9) |

| Living with partner | 8 (1.9) |

| Household head | |

| No | 49 (11.4) |

| Yes | 380 (88.6) |

| Housing type | |

| Single family house | |

| Detached from any other house | 312 (72.7) |

| Attached to ≥1 houses | 35 (8.2) |

| Building with ≥2 apartments | 60 (14.0) |

| Mobile home | 19 (4.4) |

| Boat, recreational vehicle, van, etc | 3 (0.7) |

| Household income, $ | |

| <20 000 | 69 (16.1) |

| 20 000-50 000 | 130 (30.3) |

| 50 000-100 000 | 146 (34.0) |

| 100 000-200 000 | 71 (16.6) |

| >200 000 | 13 (3.0) |

| Ownership status of living quarters | |

| Owned or being bought by respondent or someone in their household | 335 (78.1) |

| Rented for cash | 84 (19.6) |

| Occupied without payment of cash rent | 10 (2.3) |

Patient Prioritized Goals of HF Therapies

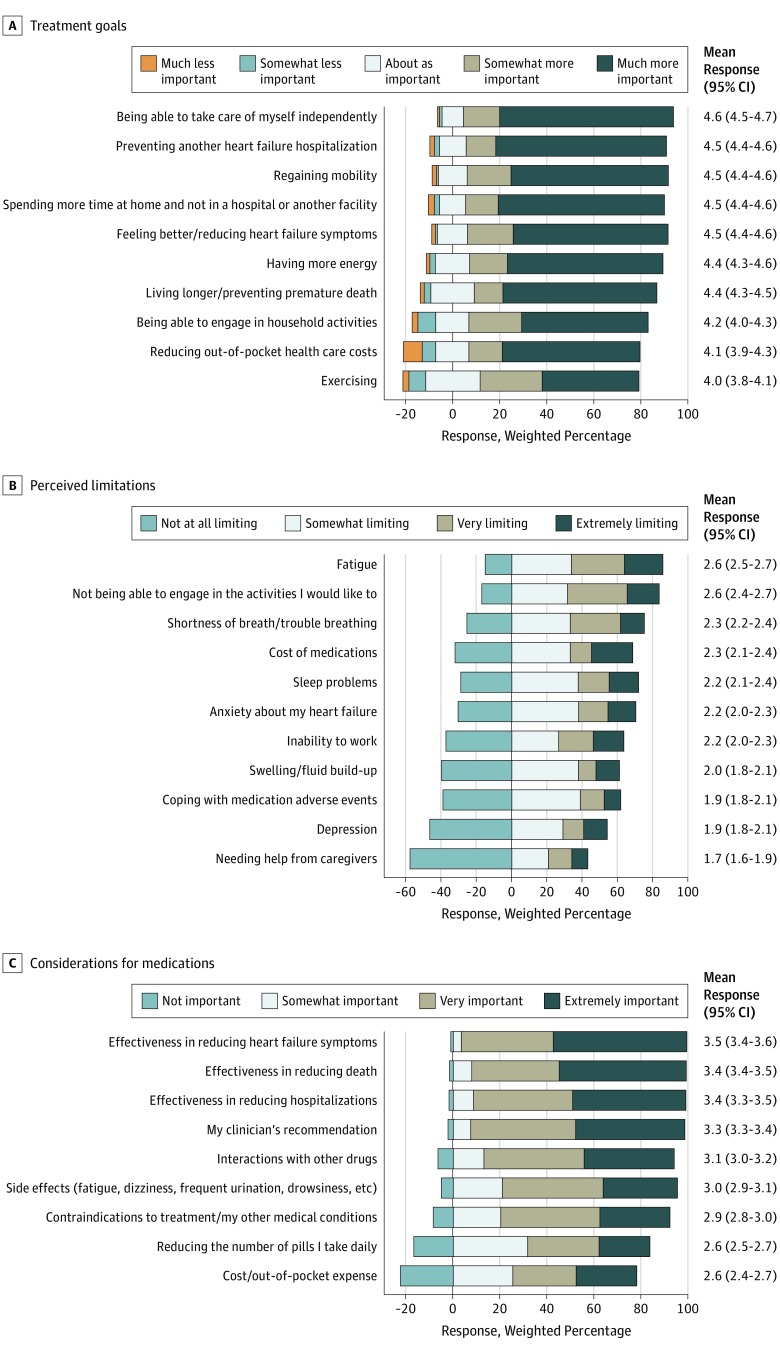

Treatment goals, listed in order of reported importance, are presented in Figure 1A. Patients prioritized being able to manage self-care independently as the most important goal of HF treatment. The second most important goal of treatment was to prevent readmission, followed by regaining mobility. Maximizing time spent at home, reducing HF symptoms, and living longer were of similar importance as well. Across all questions, men and women prioritized goals of HF therapies similarly. There were no substantial differences in prioritization of treatment goals based on age (<65 years vs ≥65 years). Participants from higher-income homes prioritized living longer more than those from lower-income homes (mean [95% CI] response score, 4.6 [4.4-4.7] vs 4.2 [4.0-4.4]). Unique to participants from higher-income homes, living longer was one of the 3 most important goals of HF therapy (eTable 1 and eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Patient Perceptions of Living With Heart Failure.

A, Patient-prioritized goals for heart failure treatment are ordered from most to least important, per weighted average survey responses. Survey design-adjusted mean (95% CI) of responses are depicted for the overall cohort to the right of each row. B, Patient-perceived limitations while living with heart failure are listed from most limiting to least limiting. Survey design-adjusted mean (95% CI) of responses are depicted for the overall cohort to the right of each row. C, Importance of patient considerations when choosing medications for treatment of heart failure. Patient considerations when choosing medications for treatment of heart failure are listed in order of most to least important. Survey design-adjusted mean (95% CI) of responses are depicted for the overall cohort to the right of each row.

Challenges Associated With Living With HF

Challenges associated with living with HF, listed in order of most to least challenging are presented in Figure 1B. For all responders, fatigue was rated as the most limiting symptom. Across all questions, men and women perceived similar challenges associated with living with HF. Patients younger than 65 years consistently responded as having more perceived challenges directly attributable to HF than did patients 65 years or older. Younger patients also perceived cost of medications as a greater limitation compared with older patients. Compared with those from higher-income households (≥$60 000), responders from lower-income households perceived more limitation from having to take more medications and from medication adverse events. Responders from lower-income homes perceived cost as one of the least limiting factors of living with HF (eTable 2 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Patient-Reported Treatment Goals

Considerations when choosing medications for treatment of HF, listed in order of most to least important, are presented in Figure 1C. Overall, effectively reducing HF-related symptoms was the most important consideration when choosing HF therapies, followed by effectiveness in reducing death and reducing HF hospitalization. Across all questions, men and women shared similar considerations when choosing medications for HF. Cost of medications was perceived as more important to younger (<65 years) patients and those from lower-income homes. However, compared with other considerations, both subgroups ranked cost as a less important consideration when choosing HF therapies (eTable 3 and eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Familiarity With Heart Failure Therapies

Overall, 58 of 429 respondents (13.4%) reported having an implanted cardioverter/defibrillator. All 58 patients reported that they had at least a partial understanding of the role of implanted cardioverter/defibrillator therapy as it pertains to the HF treatment. Overall, 55 respondents (95.3%) reported that risks/benefits of implanted cardioverter/defibrillators were clearly explained and that personal preference regarding implanted cardioverter/defibrillators was considered at the time of implantation (eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

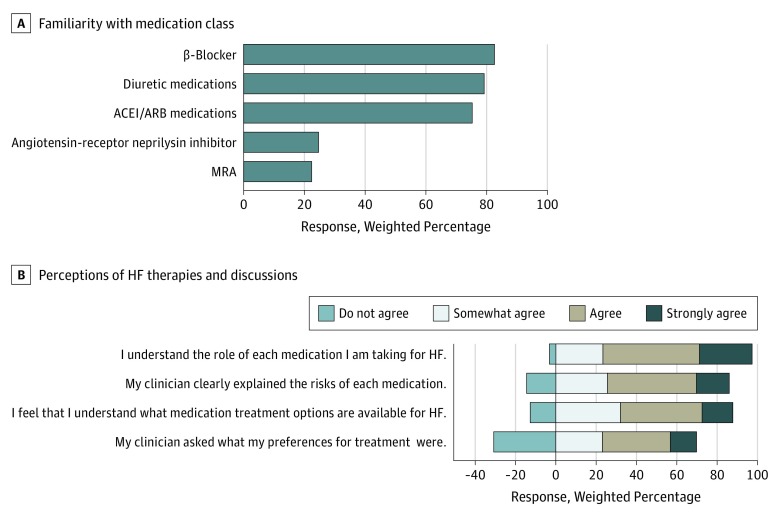

Most respondents reported having previously heard of (defined as familiarity) β-blockers (354 [82.5%]), ACEI or ARB (322 [75.2%]), and diuretics (339 [79.1%]). A total of 105 responders (24.6%) reported familiarity with angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), and 94 (22.4%) reported familiarity with MRA (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Patient Familiarity of Heart Failure Therapies.

A, Proportion of patients who responded that they were familiar with the particular medication class. B, Response frequencies for each question regarding patient perceptions of heart failure therapies and discussions with their clinician.

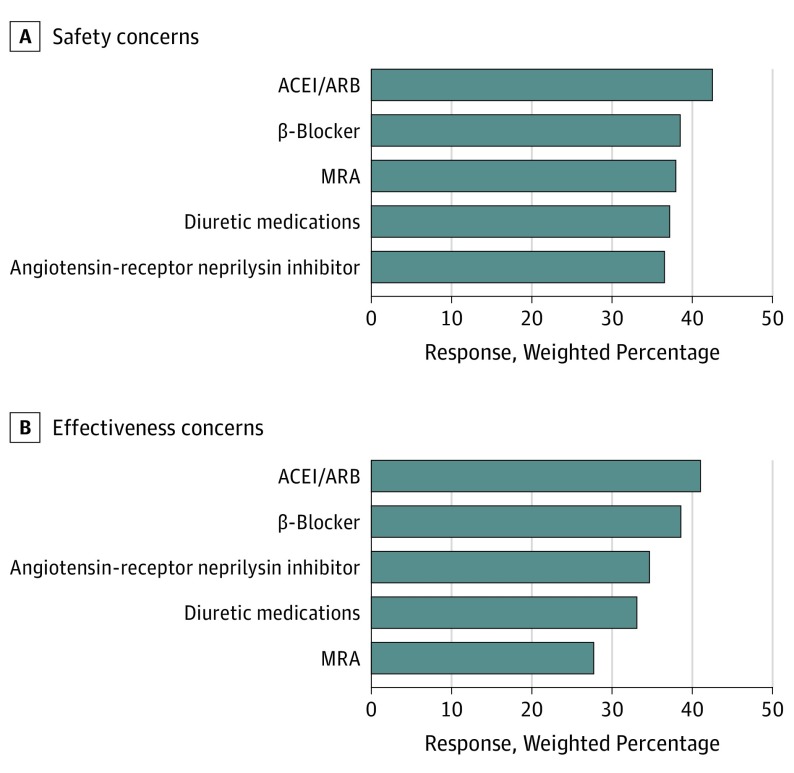

Concerns regarding safety and effectiveness of guideline-directed HF medications are shown in Figure 3. Overall, 136 patients (42.5%) reported having safety concerns regarding ACEIs/ARBs and 133 (38.5%) regarding β-blockers, 35 (37.9%) regarding MRAs, 38 (36.5%) regarding ARNIs, and 123 (37.2%) regarding diuretics. A total of 132 survey responders (41%) reported concerns regarding effectiveness of ACEI/sARBs. Between 27.7% (n = 26) and 38.5% (n = 136) of responders reported concerns regarding effectiveness of β-blockers, ARNIs, diuretics, and MRAs.

Figure 3. Patient Perceptions of Heart Failure Therapies.

A, Proportion of patients who reported having concerns regarding safety of guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure (HF). B, Proportion of patients who reported having concerns regarding effectiveness of various medications (nonmissing responses only).

Discussion

In a contemporary cohort recruited from a nationally representative sample, patients with HF identified the most important HF-related goals as (1) independently performing self-care, (2) preventing HF hospitalization/maximizing home time, (3) regaining mobility, (4) reducing HF symptoms, and (5) reducing mortality. Similarly, effectively reducing HF symptoms, reducing HF hospitalization, and reducing mortality were reported as the most important considerations when choosing HF therapies. With regard to HF-related symptoms, patients reported fatigue, being unable to engage in desired activities, and shortness of breath as the most limiting. Finally, we found that patient-reported familiarity with guideline-recommended HF with reduced ejection fraction therapies including ARNI and MRA were low, and a substantial proportion of patients reported concerns associated with perceived safety and effectiveness of these therapies.

To our knowledge, we present the most comprehensive and contemporary analysis of patient-reported goals and perceptions of long-term HF therapy. These findings support the importance of independence in self-care activities, maximizing time spent at home out of the hospital, regaining mobility, and reducing symptoms and mortality as important patient-centered goals for patients living with HF. The high relative importance of these goals was consistent irrespective of sex, age, and household income. These data are consistent with that from other highly morbid conditions including patients who have had ischemic stroke. In fact, the concept of home time, defined as time spent alive and out of health care institutions, is a robust measure of health-related quality of life after ischemic stroke and was recently as a patient-centered end point for HF populations.14

Survey responders stated that fatigue, physical limitation, and dyspnea were the most limiting symptoms of chronic HF. Consistently, improvement in symptoms along with reductions in HF hospitalization and mortality are priorities of HF therapies. Despite the results of PARADIGM-HF,3,4 which demonstrated a reduction in mortality, a reduction in HF hospitalization, and decrease in the physical limitations and symptoms associated with HF, only 25% of survey responders were familiar with ARNI. Perhaps patient unfamiliarity with newer HF therapies may explain such low recognition of sacubitril/valsartan. However, given the low rate of patient familiarity with MRAs in this analysis (approximately 20%) compared with β-blockers and ACEIs/ARBs, the lack of awareness of sacubitril/valsartan is unlikely to be fully explained by the therapy’s novelty. These findings mirror those from ongoing observational registry data such as the CHAMP-HF registry.5,6 Work from CHAMP-HF demonstrated substantial gaps in guideline-directed use, dosing, and titration of evidenced-based medications for HF.5,6 As mentioned, use of ARNIs and MRAs among appropriate patients was 14% and 33%, respectively, with a substantial proportion of discontinuations associated with a patient decision/request (rather than a medical reason, system of care reason, or heath care team member decision).6 Similarly, data from the Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure registry7 found prescription rates of sacubitril/valsartan of only 2.3% at time of hospital discharge during the 12 months after sacubitril/valsartan approval.

Our analysis showed relatively widespread patient recognition of diuretics, especially compared with sacubitril/valsartan and MRAs. Despite no definitive evidence linking diuretics with improved survival, the marked immediate symptom relief associated with diuretic use may resonate with patients. Taken in aggregate, this paradox of medication recognition compared with proven benefits on clinical outcomes, combined with registry data from the Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure registry7 and CHAMP-HF,5,6 highlight ongoing needs to improve patient awareness of the benefits of ARNI and other evidence-based HF therapies.

Cost/out-of-pocket expenses were perceived to be less important by the survey participants when considering HF therapies. However, this perception is likely formed based on the survey participants’ own experience regarding out-of-pocket costs for HF therapies. Most survey participants indicated familiarity with longstanding therapies such as ACEI/ARB and β-blockers, which only require nominal copays with most insurance plans, while less than 25% of them had heard of ARNI, a newer HF therapy with no generic options available. Future research is needed to understand changes in patients’ perception of cost burden of HF therapies over time as the newer HF therapies become more widely adopted in clinical practice.15,16,17,18

More than 25% of survey responders reported that their treatment decision was made entirely by their clinician. Although every effort should be made to maximize GDMT, one must acknowledge the limitations of data generated from randomized clinical trials for individual patient treatment decisions. Specifically, that average treatment effects and individual treatment effects may not always be equal.19 As such, shared decision-making in the context of being well informed of the clinical benefits and risks of therapy should be an important and iterative component of future patient education initiatives for patients with HF.20 Furthermore, shared decision-making will help clinicians understand how patients perceive and prioritize competing risks and to help alleviate the demonstrated gap between evidence-based and preference-based treatment decisions.21,22

The results of this survey demonstrate that patients with HF prioritize independence, reducing morbidity/mortality, and minimizing HF symptoms. This analysis is consistent with findings from large, contemporary national registries demonstrating that patient unfamiliarity may be contributing to underuse and underdosing of GDMT for HF.5,6 This unfamiliarity, coupled with high proportions of patients expressing concerns over the safety and efficacy of therapies, suggest that substantial patient-targeted educational efforts are needed to match the priorities of patients with HF with the evidence-based medications proven to address them. To optimally support shared decision-making, such efforts must not only focus on inherent risks of adverse events with medications but must effectively communicate the patient-centered benefits of therapy including improved survival, reduced hospitalizations, increased home time, and improved quality of life.23 Understanding these benefits, along with the risk of not escalating GDMT among eligible patients, is critical for purposes of being well informed of how HF medication decisions affect health-related goals and overall prognosis.

Limitations

This was a random survey distributed via the GfK KnowledgePanel; therefore, there is an inherent associated selection bias as not all patients with HF have the capability to participate. Neither the selection process nor the survey required patients to state their ejection fraction or discern whether or not they had HF with reduced or preserved ejection fraction. This decision was made during the survey design phase, as patients who are told they have HF may not be aware of their specific ejection fraction or whether their ejection fraction is preserved or reduced. Given that there are fewer guideline-recommended therapies for HF with preserved ejection fraction, patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction may be less familiar with the therapies we surveyed, which may have influenced our overall results. Furthermore, this survey was constructed using qualitative data gathered from a panel of patients from a single, quaternary referral center. Although members of the focus groups were chosen to represent a culturally diverse and wide spectrum of disease status, these patients may not be fully representative of patients with HF across the United States. When prompting patients for the importance of time spent at home, this survey did not differentiate between time spent in a hospital vs an alternative care facility such as a skilled nursing facility or long-term care center. The relative importance of time spent at home may depend on the duration and location of care. This survey did not assess baseline functional status nor did it collect current medication prescriptions, which may also have biased survey responders. Although this analysis did rank patient-reported goals, mean response scores for all goals clustered within a narrow range between 4 and 5. Thus, while ranking of most important goals can be inferred, small absolute differences in mean response scores should be recognized. Finally, this study was conducted around the time of recalls of multiple ARBs. Because the survey was already underway at the time of the recalls, we were unable to assess how they may have altered patient perceptions regarding safety of GDMT.

Conclusions

Top priorities for patients with HF include the ability to function independently, to reduce morbidity/mortality, and to minimize HF symptoms. There is a disconnect between patient priorities and the awareness of GDMT proven to address them. Patient familiarity of GDMT therapies is low and many patients familiar with therapy have concerns over its safety and effectiveness. These factors may partly explain the significant underutilization of GDMT observed in other studies. Further educational efforts and quality improvement initiatives are needed to improve awareness and use of GDMT for HF.

eAppendix. Questionnaire

eTable 1. Relative Importance of HF-specific, pre-specified subgroups

eTable 2. Patient reported challenges related to living with HF, stratified by prespecified subgroups

eTable 3. Patient perceived Important considerations when choosing HF treatments, prespecified subgroups

eFigure 1. Patient prioritized treatment goals for heart failure, stratified by subgroups

eFigure 2. Patient perceived limitations while living with heart failure, stratified bv subgroups

eFigure 3. Patient considerations when choosing medications for treatment of heart failure, stratified by subgroups

eFigure 4. Patient perceptions of implantable cardioverter defibrillators for treatment of heart failure

References

- 1.Jaarsma T, Johansson P, Ågren S, Strömberg A. Quality of life and symptoms of depression in advanced heart failure patients and their partners. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2010;4(4):292-299. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e328340744d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, et al. . Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart. 2002;87(3):235-241. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. ; PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees . Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993-1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra A, Lewis EF, Claggett BL, et al. . Effects of sacubitril/valsartan on physical and social activity limitations in patients with heart failure: a secondary analysis of the PARADIGM-HF trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(6):498-505. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, et al. . Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the CHAMP-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):351-366. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, DeVore AD, et al. . Titration of medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(19):2365-2383. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo N, Fonarow GC, Lippmann SJ, et al. . Early adoption of sacubitril/valsartan for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from Get With the Guidelines-Heart Failure (GWTG-HF). JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(4):305-309. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozkurt B. Reasons for lack of improvement in treatment with evidence-based therapies in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(19):2384-2387. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Curtis AB, et al. . Improving evidence-based care for heart failure in outpatient cardiology practices: primary results of the Registry to Improve the Use of Evidence-Based Heart Failure Therapies in the Outpatient Setting (IMPROVE HF). Circulation. 2010;122(6):585-596. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller DG, Kim SYH, Li X, et al. . Ethical acceptability of postrandomization consent in pragmatic clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e186149-e186149. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nayak RK, Wendler D, Miller FG, Kim SY. Pragmatic randomized trials without standard informed consent?: a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(5):356-364. doi: 10.7326/M15-0817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomlinson T, De Vries R, Ryan K, Kim HM, Lehpamer N, Kim SY. Moral concerns and the willingness to donate to a research biobank. JAMA. 2015;313(4):417-419. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickert NW, Wendler D, Devireddy CM, et al. . Consent for pragmatic trials in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(9):1051-1053. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene SJ, O’Brien EC, Mentz RJ, et al. . Home-time after discharge among patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(23):2643-2652. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeJong C, Kazi DS, Dudley RA, Chen R, Tseng CW. Assessment of national coverage and out-of-pocket costs for sacubitril/valsartan under Medicare part D. JAMA Cardiol. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Jonge N, Kirkels H, Lahpor JR, et al. . Exercise performance in patients with end-stage heart failure after implantation of a left ventricular assist device and after heart transplantation: an outlook for permanent assisting? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(7):1794-1799. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01268-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yancy CW, Januzzi JL Jr, Allen LA, et al. . 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for optimization of heart failure treatment: answers to 10 pivotal issues about heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(2):201-230. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blackstone EH. Precision medicine versus evidence-based medicine: individual treatment effect versus average treatment effect. Circulation. 2019;140(15):1236-1238. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. ; American Heart Association; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia . Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(15):1928-1952. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tinetti ME, McAvay GJ, Fried TR, et al. . Health outcome priorities among competing cardiovascular, fall injury, and medication-related symptom outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(8):1409-1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01815.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quill TE, Holloway RG. Evidence, preferences, recommendations: finding the right balance in patient care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(18):1653-1655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, Butler J. Reply: titration of guideline-directed medical therapy improves patient-centered outcomes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(10):1426-1427. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.06.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Questionnaire

eTable 1. Relative Importance of HF-specific, pre-specified subgroups

eTable 2. Patient reported challenges related to living with HF, stratified by prespecified subgroups

eTable 3. Patient perceived Important considerations when choosing HF treatments, prespecified subgroups

eFigure 1. Patient prioritized treatment goals for heart failure, stratified by subgroups

eFigure 2. Patient perceived limitations while living with heart failure, stratified bv subgroups

eFigure 3. Patient considerations when choosing medications for treatment of heart failure, stratified by subgroups

eFigure 4. Patient perceptions of implantable cardioverter defibrillators for treatment of heart failure