Key Points

Question

What are the patterns of use and associated costs of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine for Medicare Part D and Medicaid?

Findings

In this US nationwide claims-based study, the number of Medicare beneficiaries prescribed sacubitril/valsartan increased from 35 423 to 90 606 (156% increase from 2016 to 2017). Medicare beneficiaries prescribed ivabradine increased from 15 856 to 23 213 (46% increase), the annual Medicare per-beneficiary spending on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine was $2512 and $2400, and parallel trends in use patterns and spending were observed among Medicaid beneficiaries.

Meaning

Current use of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine is increasing, but ongoing efforts are needed to promote high-value care, while improving affordability and access to established and emerging heart failure therapies.

Abstract

Importance

In 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration approved 2 new medications for treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine. However, few national data are available examining their contemporary use and associated costs.

Objective

To evaluate national patterns of use of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine and associated therapeutic spending in Medicare Part D and Medicaid.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this US nationwide claims-based study, we analyzed data from the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event and Medicaid Utilization and Spending data sets to compare national patterns of use of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine between 2016 and 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Changes in total spending, per-beneficiary/claim spending, number of beneficiaries, and number of claims between 2016 and 2017 for sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine.

Results

The number of Medicare beneficiaries prescribed sacubitril/valsartan increased from 35 423 to 90 606 (156% increase from 2016 to 2017). Medicare beneficiaries prescribed ivabradine increased from 15 856 to 23 213 (46% increase). In 2017, Medicare Part D spent $227 million and $7.3 million on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine, respectively. This represented increases of 241% and 59% compared with 2016 spending, respectively. The annual Medicare per-beneficiary spending on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine was $2512 and $2400. Parallel trends in use patterns and spending were observed among Medicaid beneficiaries.

Conclusions and Relevance

Although initial experiences suggested slow uptake after regulatory approval, these national data demonstrate an increase in use of sacubitril/valsartan and, to a lesser degree, ivabradine in the United States. Current annual per-beneficiary expenditures remain less than spending thresholds that have been reported to be cost-effective. Ongoing efforts are needed to promote high-value care while improving affordability and access to established and emerging heart failure therapies.

This study evaluates US national patterns of use of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine and associated therapeutic spending in Medicare Part D and Medicaid.

Introduction

Nine classes of therapies have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), of which 5 have class I recommendations in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines and many are available as low-cost generic formulations.1 In 2015, the FDA approved 2 new medications for treatment of HFrEF, sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine, both of which are supported by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for HF.1 While initial experiences with use of sacubitril/valsartan reported suboptimal uptake, limited nationally representative data are available examining the contemporary patterns of use and associated spending for these latest HFrEF therapies.2 The increasing burden of HFrEF and the growing complexity of its management necessitates a comprehensive, national-level assessment of the utilization patterns and associated costs to better understand the existing gaps and future challenges to evidence-based care. Accordingly, we examined the national patterns of use of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine and associated spending in 2016 and 2017 among Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries using claims data.

Methods

We analyzed publicly available data from the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event, a data set that contains pharmaceutical spending data for approximately 70% of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part D, and the Medicaid Utilization and Spending data set, which contains national-level Medicaid spending data for medications partially or fully reimbursed by Medicaid for the approximately 75 million beneficiaries. We extracted the number of beneficiaries, total spending, spending per claim, and spending per beneficiary for sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine. All beneficiaries who received a minimum of 1 prescription were included in the calculation for spending per beneficiary. The per-claim spending was defined as the cost per prescription. Because sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine were approved mid-2015, we examined changes between 2016 and 2017. All costs were adjusted for inflation and represented in 2017 US dollars. Because all data were deidentified and publicly available, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, institutional review board considered our study exempt.

Results

Sacubitril/Valsartan

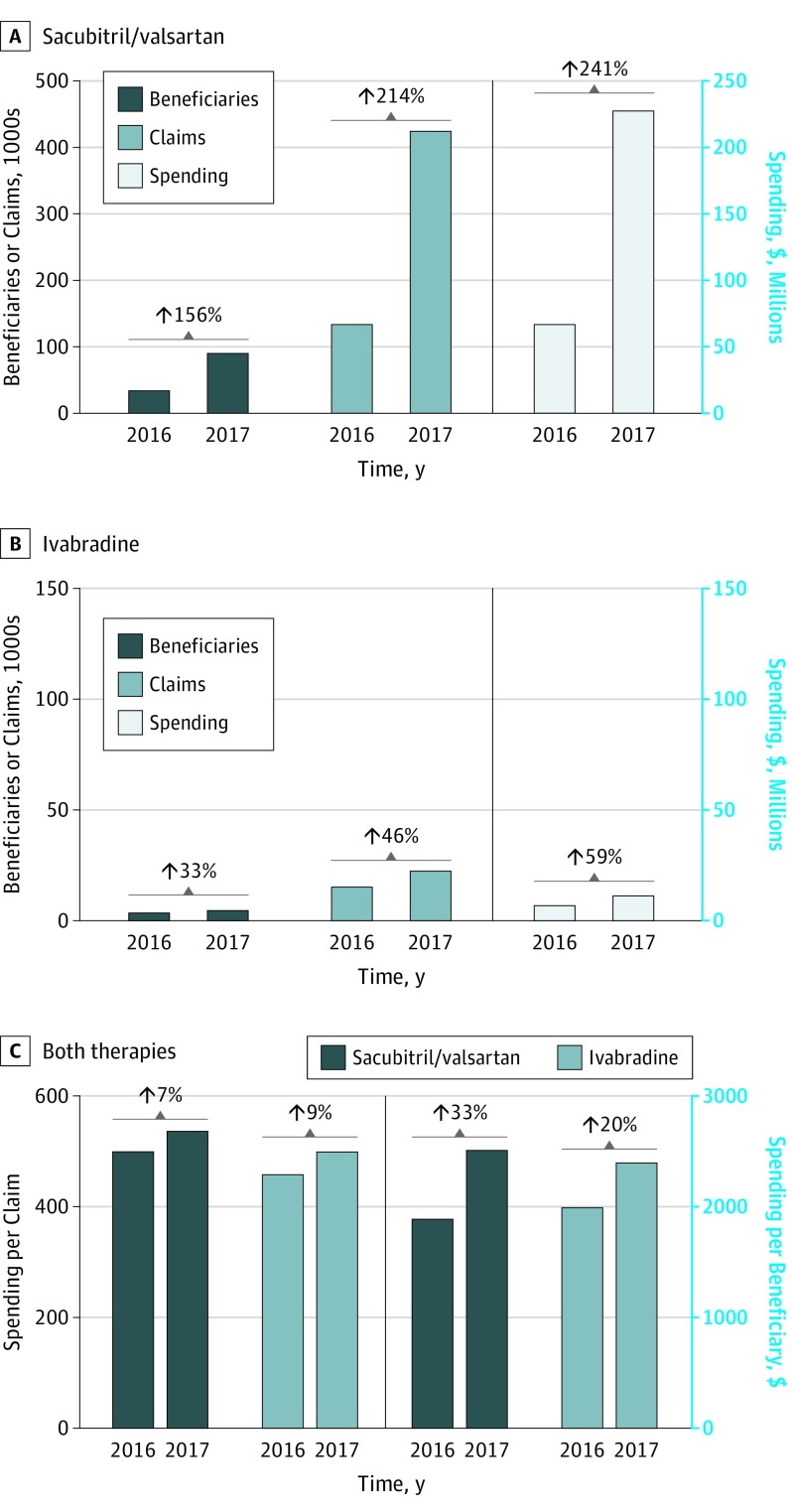

The number of Medicare Part D beneficiaries prescribed sacubitril/valsartan increased by 156%, from 35 423 in 2016 to 90 606 in 2017 (Figure 1A). The number of individual prescriptions for sacubitril/valsartan also increased by 217% (424 910) and the average spending per beneficiary increased by 33% ($2512) during the same period (Figure 1C). In 2017, Medicare Part D spent $227 million on sacubitril/valsartan, an increase of 241% from 2016. The average Medicare spending per sacubitril/valsartan prescription was $536 in 2017.

Figure 1. Medicare Part D Utilization Trends of Sacubitril/Valsartan and Ivabradine Between 2016 and 2017.

A, Beneficiaries, claims, and total spending of sacubitril/valsartan. B, Beneficiaries, claims, and total spending of ivabradine. C, Per claim and per-beneficiary cost of both therapies.

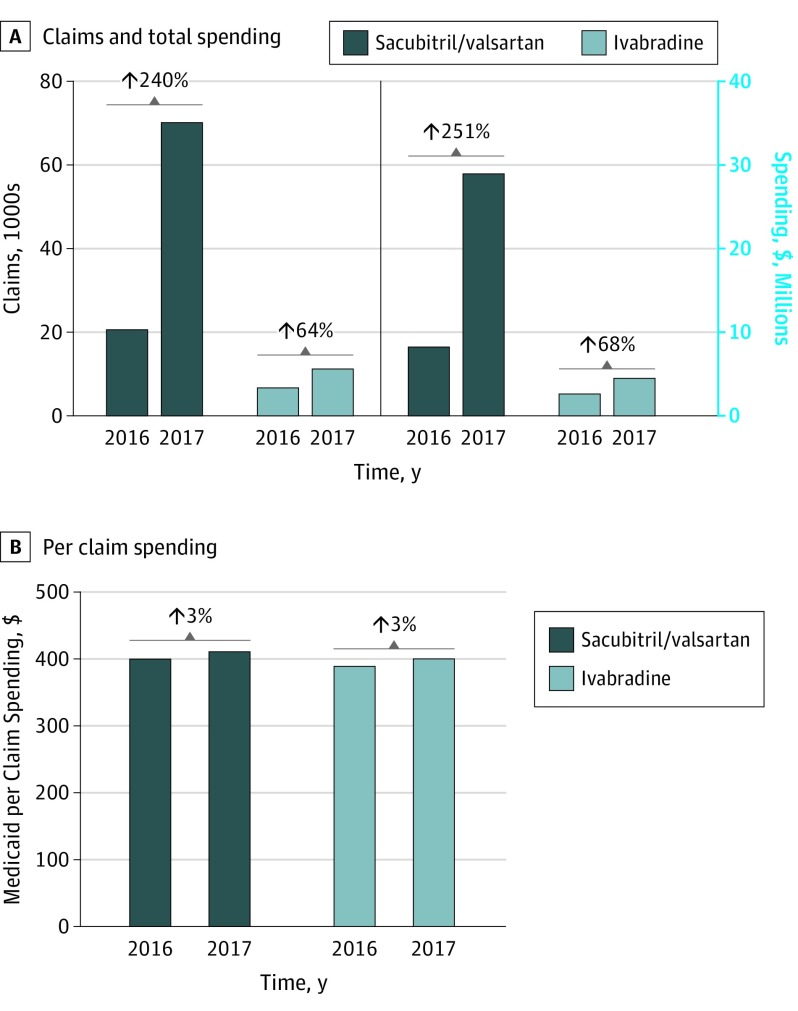

Medicaid spent $29 million on 1.7 million prescription fills of sacubitril/valsartan in 2017, representing a 251% increase in total spending (Figure 2) and 240% increase in total claims from 2016. The mean Medicaid spending per sacubitril/valsartan prescription was $412 in 2017.

Figure 2. Medicaid Utilization Trends of Sacubitril/Valsartan and Ivabradine Between 2016 and 2017.

A, Claims and total spending of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine. B, Per claim spending on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine.

Ivabradine

The number of Medicare beneficiaries and prescription claims for ivabradine increased by 33% (from 3637 to 4820) and 46% (from 15 856 to 23 213), respectively, while the spending per beneficiary increased 20% ($1996 to $2400). Medicare Part D payments for ivabradine increased from $7.3 million in 2016 to $11.6 million in 2017 (59% increase) (Figure 1B). The average Medicare spending per ivabradine prescription was $401.

In 2017, Medicaid spending on ivabradine increased by 68% to $4.5 million, coinciding with a 64% increase in number of filled prescriptions (6864 in 2016 to 11 234 in 2017) (Figure 2). The mean Medicaid spending per ivabradine prescription was $401.

Discussion

We observed marked increases in use of sacubitril/valsartan and, to a lesser degree, ivabradine, from 2016 to 2017 among Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Spending on these novel therapies for HFrEF paralleled this expanded use.

Early experiences from the Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure registry reported that only 2% of eligible patients received sacubitril/valsartan in the year following FDA approval.2 Findings from the Change the Management of Patients With Heart Failure registry3 demonstrated that 15% of eligible patients were prescribed sacubitril/valsartan from 2016 to 2017.4 Our data add to the existing literature and highlight the ongoing expanded use of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine in the larger, less selected, and more generalizable Medicare and Medicaid populations. Our findings also provide insights into the cost burden to Medicare and Medicaid associated with the expanded use of these novel HFrEF therapies.

The accelerated uptake of sacubitril/valsartan observed in our study is in sharp contrast to the previously reported delayed adoption of evidence-based therapies for HFrEF and may be associated with several factors.5 A significant contributing factor to the increase in prescription is the expansion of Medicare plans covering sacubitril/valsartan, from 9% in 2015 to 88% by December 2016.6 Similarly, ease of prescribing improved, with 100% prior authorization rate in mid-2016 and decreasing to 77% by the end of 2016. As of 2018, 100% of Medicare plans cover sacubitril/valsartan and 38% require prior authorization rate.7 In addition, the large magnitude of benefit observed consistently across multiple clinical and patient-reported outcomes, additional randomized clinical trial data confirming its overall safety profile, and the integration of sacubitril/valsartan into guidelines as class I recommendations for HFrEF likely also contributed to the increase in its prescription.1 Furthermore, while our study focuses on costs to the payer, studies have demonstrated a decline in out-of-pocket costs for sacubitril/valsartan as Medicare formularies started adding sacubitril/valsartan as a preferred agent.7 Proposals aimed at limiting out-of-pocket costs for Medicare Part D beneficiaries, such as redesigning Part D payment structures and permitting Medicare to negotiate prices, are under active consideration and would be key to promoting its use among eligible patients.8,9

As with sacubitril/valsartan, we also observed a significant increase in ivabradine use and associated cost. While we are unable to ascertain the proportion of patients eligible for these therapies, we believe these observed trajectories are the first reported national trends of ivabradine and suggest expansion of therapeutic uptake among Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

Several analyses have suggested that sacubitril/valsartan is cost-effective for HFrEF patients owing to reductions in downstream health care expenditures.10,11,12 The annual expenditure per Medicare beneficiary observed in our study ($2512 in 2017) was substantially lower than the cost-effective spending threshold reported in prior studies ($3375 for an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $35 696 per quality-adjusted life-year gained).10,12 Given the reported prevalence of HF in the Medicare population (5.3 million) and a conservative estimate of 50% with HFrEF (2.65 million), prescribing all eligible patients (70% of all HFrEF)13 could cost Medicare approximately $4.7 billion. Furthermore, the proportional use of sacubitril/valsartan among all eligible patients still remains low. Ivabradine has a narrower scope of eligibility and does not reduce mortality, yet cost-effectiveness analyses suggest the expected hospitalization reductions result in a reasonable incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.14 With FDA approval of tafamadis for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy and robust benefits of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in HF,15 the therapeutic options for evidence-based management of HFrEF continue to expand. Our study findings provide insights into the potential up-front economic burden that can be expected with widespread use of these novel HFrEF therapies. Furthermore, these findings highlight the need for continued efforts from all stakeholders, including the pharmaceutical industry, policy makers, payers, and health systems, to address the cost-related barriers to these medications.

Limitations

Certain limitations to our study are noteworthy. First, the use patterns may not be generalizable to other payer demographics. Second, the extent to which the patterns in use of these drugs is influenced by changes in the Medicare Part D or Medicaid populations is uncertain. However, this is unlikely to significantly influence our study findings because the total Medicare Part D beneficiaries only increased by 3.7% from 2016 to 2017. Third, our data do not account for patient-level parameters and do not inform appropriateness of therapy initiation or switching. Finally, because the most recent release of Medicare brand-name rebates was prior to the approval of ivabradine and sacubitril/valsartan, our calculations did not adjust for rebates.

Conclusions

The use of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine has increased sharply among Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries from 2016 to 2017, with per-beneficiary expenditures less than the cost-effective thresholds. Further efforts to promote use of high-value established and emerging HF therapies are needed while improving affordability to individual patients.

References

- 1.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. ; WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS . 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2016;134(13):e282-e293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo N, Fonarow GC, Lippmann SJ, et al. Early adoption of sacubitril/valsartan for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure (GWTG-HF). JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(4):305-309. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, et al. Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the CHAMP-HF registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):351-366. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeVore AD, Hill CL, Thomas L, et al. Patient, provider, and practice characteristics associated with sacubitril/valsartan use in the United States. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(9):e005400. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albert NM, Yancy CW, Liang L, et al. Use of aldosterone antagonists in heart failure. JAMA. 2009;302(15):1658-1665. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novartis. Q4 and Full Year 2016 Results. https://www.novartis.com/sites/www.novartis.com/files/q4-2016-ir-presentation.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed October 20, 2019.

- 7.DeJong C, Kazi DS, Dudley RA, Chen R, Tseng C-W. Assessment of national coverage and out-of-pocket costs for sacubitril/valsartan under Medicare Part D. JAMA Cardiol. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dusetzina SB, Keating NL, Huskamp HA. Proposals to redesign Medicare Part D: easing the burden of rising drug prices. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1401-1404. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1908688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank RG, Nichols LM. Medicare drug-price negotiation : why now…and how. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1404-1406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1909798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaziano TA, Fonarow GC, Claggett B, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of sacubitril/valsartan vs enalapril in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(6):666-672. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandhu AT, Ollendorf DA, Chapman RH, Pearson SD, Heidenreich PA. Cost-effectiveness of sacubitril-valsartan in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(10):681-689. doi: 10.7326/M16-0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert NM, Swindle JP, Buysman EK, Chang C. Lower hospitalization and healthcare costs with sacubitril/valsartan versus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker in a retrospective analysis of patients with heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(9):e011089. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parikh KS, Lippmann SJ, Greiner M, et al. Scope of sacubitril/valsartan eligibility after heart failure hospitalization: findings from the GWTG-HF registry (Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure). Circulation. 2017;135(21):2077-2080. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kansal AR, Cowie MR, Kielhorn A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ivabradine for heart failure in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(5):e003221. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. ; DAPA-HF Trial Committees and Investigators . Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]