Abstract

The functional neuroanatomy and connectivity of reward processing in adults are well documented, with relatively less research on adolescents, a notable gap given this developmental period's association with altered reward sensitivity. Here, a large sample (n = 1,510) of adolescents performed the monetary incentive delay (MID) task during functional magnetic resonance imaging. Probabilistic maps identified brain regions that were reliably responsive to reward anticipation and receipt, and to prediction errors derived from a computational model. Psychophysiological interactions analyses were used to examine functional connections throughout reward processing. Bilateral ventral striatum, pallidum, insula, thalamus, hippocampus, cingulate cortex, midbrain, motor area, and occipital areas were reliably activated during reward anticipation. Bilateral ventromedial prefrontal cortex and bilateral thalamus exhibited positive and negative activation, respectively, during reward receipt. Bilateral ventral striatum was reliably active following prediction errors. Previously, individual differences in the personality trait of sensation seeking were shown to be related to individual differences in sensitivity to reward outcome. Here, we found that sensation seeking scores were negatively correlated with right inferior frontal gyrus activity following reward prediction errors estimated using a computational model. Psychophysiological interactions demonstrated widespread cortical and subcortical connectivity during reward processing, including connectivity between reward‐related regions with motor areas and the salience network. Males had more activation in left putamen, right precuneus, and middle temporal gyrus during reward anticipation. In summary, we found that, in adolescents, different reward processing stages during the MID task were robustly associated with distinctive patterns of activation and of connectivity.

Keywords: adolescence, functional connectivity, gender differences, reward processing, sensation seeking

1. INTRODUCTION

The capacity to anticipate and detect rewarding outcomes is fundamental for the development of goal‐orientated behavior and efficient decision‐making. Alterations in reward sensitivity during adolescence contribute to the emergence of impulsive decisions and risk‐taking behaviors, such as substance‐use (Jollans et al., 2016; Karoly et al., 2015; Weiland et al., 2013). Reward system dysfunction is also involved in the pathogenesis of numerous psychiatric disorders during adolescence, such as ADHD (Ma et al., 2016; Scheres, Milham, Knutson, & Castellanos, 2007). Given that adolescence is a neurodevelopmental period associated with an altered sensitivity to rewarding outcomes and situations, mapping the neural correlates of different stages of reward processing in adolescence is important.

Reward processing involves discrete anticipation and outcome stages that each recruits overlapping and distinct brain regions. These stages and their neural correlates can be effectively isolated using the monetary incentive delay (MID) task with concurrent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) (Knutson, Westdorp, Kaiser, & Hommer, 2000). In this task, an incentive cue signals a likely reward (e.g., 10 c) or non‐reward (i.e., 0 c) and then a target stimulus prompts a speeded behavioral response (e.g., a button‐press in response to a blue square). Simple feedback then denotes the receipt or, alternatively the infrequent omission, of the reward. In adolescents, the reward anticipation period is associated with increased activation in the ventral striatum (VS), insula, thalamus, caudate, and supplementary motor area (SMA); additionally, VS activity is positively associated with the amount of the likely reward (Bjork et al., 2004; Bjork, Smith, Chen, & Hommer, 2010). A review of 26 studies (Silverman, Jedd, & Luciana, 2015) that used a variety of differing reward‐related tasks (e.g., delay discounting tasks, MID tasks) indicated that, during adolescence, reward anticipation activates left nucleus accumbens (NAcc), right caudate, right insula, left frontal operculum cortex, and left supplementary motor cortex.

Reward receipt is associated with increased activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) in adolescents (Bjork et al., 2004, 2010). A wealth of evidence from adult studies suggests that vmPFC activation is associated with reward valuation (Levy & Glimcher, 2011; Peters & Büchel, 2010; Smith et al., 2010) and magnitude (Diekhof, Kaps, Falkai, & Gruber, 2012). The VS is also active when there is a mismatch between the expected and actual reward outcome (i.e., a prediction error; PE) (Hare, O'Doherty, Camerer, Schultz, & Rangel, 2008; Peters & Büchel, 2010). VS activity (i) increases when the actual reward is greater than what was predicted (i.e., positive PE), (ii) decreases when the actual reward is less than what was anticipated (i.e., negative PE), and (iii) remains static when there is no discrepancy between what is expected and what is received (Schultz, 2016). Reward PEs can be detected by contrasting brain activity from trials in which expected rewards were delivered against trials in which rewards were unexpectedly omitted. Furthermore, computational modeling (e.g., using a Rescorla–Wagner model; Rescorla & Wagner, 1972) of the task‐based signal‐reward contingencies can be used to estimate each individual's trial‐by‐trial prediction errors (Glascher & O'Doherty, 2010). The specificity of the vmPFC and VS for reward receipt and PE, respectively, has been shown previously in adults (Rohe, Weber, & Fliessbach, 2012).

The different stages of reward processing are characterized by distinct changes in functional connectivity among different brain regions. For example, Silverman et al. (2015) proposed that, during reward receipt in adolescents, projections from insula and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) allow the integration of reward evaluation and incentive‐based behavioral activation in VS. From the perspective of adolescent development, interactions between brain regions such as VS and regions in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) are emphasized in neurobiological models such as the dual‐system model, the triadic model, and the imbalance model (see Casey, 2015 for a review). Functional connectivity between brain regions can be quantified using a psychophysiological interactions (PPI) analysis (Friston, et al., 1997), which examines if correlation in activity between seed regions and the rest of the brain vary as a function of the experimental manipulation. This method has been employed in previous research into adolescent reward‐processing (Ernst, Torrisi, Balderston, Grillon, & Hale, 2015; Van den Bos, Cohen, Kahnt, & Crone, 2012; Van den Bos, Rodriguez, Schweitzer, & McClure, 2015). PPI analyses have shown, for example, that VS‐PFC connectivity predicted the updating of outcome expectancy following negative feedback during a probabilistic learning task in children, adolescent, and adults (Van den Bos et al., 2012).

Biological factors such as gender and pubertal development are known to influence adolescent brain functions (Azim, Mobbs, Jo, Menon, & Reiss, 2005; Blakemore, Burnett, & Dahl, 2010; Forbes, Phillips, Silk, Ryan, & Dahl, 2011; Forbes et al., 2010; Goddings et al., 2014; Haase, Green, & Murphy, 2011; Klapwijk et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2012; Munro et al., 2006; Urosevic, Collins, Muetzel, Lim, & Luciana, 2014). For instance, longitudinal research suggests that pubertal development is significantly positively correlated with the structural volumes of amygdala and hippocampus, and negatively correlated to volumes of NAcc, caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus (Goddings et al., 2014). Furthermore, adolescents at a more advanced pubertal stage exhibited less striatal and more medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) activation during reward processing than those at a less advanced pubertal stage (Forbes et al., 2010). An understanding of the impact of these factors impact could shed light on gender ratios of adolescent psychiatric disorders as well as their developmental trajectories. Typically, the effects of gender and puberty have not been analyzed or have been controlled for statistically in previous reward processing studies (Bjork et al., 2004, 2010; Jia et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2011; Stringaris et al., 2015), which make their specific contribution in reward processing unclear.

Sensation seeking is a reward‐related personality characteristic that involves seeking novel or intense sensations and experiences, and a willingness to take risks for the sake such experiences (Zuckerman, 2014). Sensation seeking is a predictor of risk‐taking behavior during adolescence, including intentions to try smoking and drinking (Jurk et al., 2015; Memetovic, Ratner, Gotay, & Richardson, 2016). Structural and functional VS variations were previously associated with sensation seeking in adolescents (Hawes et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2015). Also, a previous study demonstrated that high sensation seeking adolescents (n = 27, mean age: 14.12 years old), compared with low sensation seeking adolescents (n = 27, mean age: 13.75 years old), had greater bilateral insula and IFG brain responses to reward receipt versus reward absence during a Wheel of Fortune decision making task (Cservenka et al., 2013). Differences were only apparent when comparing tertiles of high and low sensation seeking scores. Cservenka et al. did not find brain regions that correlated with sensation seeking nor did they find that NAcc activity correlated with sensation seeking. The latter result is consistent with another study (n = 139) that used an incentivized anti‐saccade task with mid‐adolescents (age range = 12–16 years old) (Hawes et al., 2017) and reported the absence of a correlation between reward‐related NAcc activity and sensation seeking.

There are a limited number of empirical investigations into adolescent reward processing and extant studies have employed small sample sizes (Bjork et al., 2004, 2010), as is typical for functional neuroimaging studies (Button et al., 2013). Meta‐analyses of reward processing exist (Liu, Hairston, Schrier, & Fan, 2011; Silverman et al., 2015). However, these have amalgamated data from a range of different reward‐related tasks with widely different methodological parameters (e.g., delay discounting, gambling tasks, and MID tasks) that likely evoke different patterns of brain activity. The MID task is currently used in multisite longitudinal neuroimaging studies, such as IMAGEN (Schumann et al., 2010), and the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development study (ABCD; Casey et al., 2018). Therefore, a precise characterization of the neural correlates of the MID task would be advantageous. PPI is a useful method but—due to the inclusion of correlated regressors in the same model—has low statistical power, particularly for event‐related designs (O'Reilly, Woolrich, Behrens, Smith, & Johansen‐Berg, 2012): large sample sizes can ameliorate this drawback of PPI.

In this study, adolescents from a community‐based sample and multicenter fMRI study performed the MID task (Schumann et al., 2010). These adolescents were 14 years old on average, a key developmental period for risk‐taking behavior and for the emergence of psychiatric symptoms (Schumann et al., 2010). We first created probabilistic maps of activation to identify regions reliably activated during reward anticipation, receipt, and infrequent reward omission. Constructing probabilistic maps has proven useful for interrogating large neuroimaging datasets, including IMAGEN. For example, Tahmasebi et al. identified regions that were reliably activated in response to emotional faces (Tahmasebi et al., 2012). Second, PPI analyses were conducted to investigate the functional connectivity with respect to reward anticipation, receipt, and instances of infrequent reward omission. Based on prior findings (Silverman et al., 2015), we expected to observe activation in SMA, VS, insula, and caudate during reward anticipation. In line with previous studies showing increased vmPFC activation during reward outcome (Bjork et al., 2004, 2010), we expected similar findings during reward receipt. For the infrequent reward omission, we predicted that the VS would be activated. Furthermore, we applied the Rescorla–Wagner reinforcement learning model to first estimate trial‐by‐trial reward PE and then describe its neural correlates. As reward PE is observed primarily in VS (Garrison, Erdeniz, & Done, 2013), we predicted that the modulation effects of trial‐by‐trial estimated reward PE to be observed in VS. For the functional connectivity, we expected to observe the involvement of a wide range brain networks such as visual, salience, sensorimotor, and control networks in reward processing, which could be represented by the connections between seed regions and typical areas such as occipital lobe, motor areas, insula, SMA, and frontal areas (Silverman et al., 2015; Van den Bos et al., 2012, 2015). To clarify the role of other biological factors, we directly compared activation and connectivity patterns between males and females, and between early and late pubertal stages. Finally, we correlated sensation seeking scores with brain activation and connectivity during reward processing to examine neural correlates of this personality trait.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants

Adolescents (n = 1,510, 795 females) from the IMAGEN project were included in the present study, with data collected from eight sites (France, United Kingdom, Ireland, Germany). The project was approved by all local ethics research committees, and informed consent was obtained from participants and their parents/guardians. A detailed description of the study protocol and data acquisition has been previously published (Schumann et al., 2010).

2.2. MRI data acquisition

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquisition was performed with a 3 T MRI system from various manufacturers (Siemens, Philips, General Electric, and Bruker). Standardized hardware for visual and auditory stimulus presentation (Nordic Neurolabs, Bergen Norway) was used at all sites. To minimize effects of different scanners, a set of acquisition parameters compatible with all scanners was used across sites. High resolution T1‐weighted structural images were acquired (sagittal slice plane, repetition time = 2,300 ms, echo time = 2.8 ms, flip angle = 8°, matrix = 256 × 256, field of view = 280 × 280 mm2) for anatomical localization and co‐registration with the functional time series. Blood‐oxygen‐level‐dependent (BOLD) images were acquired with a gradient echo‐planar imaging (EPI) sequence using similar acquisition parameters across sites (i.e., oblique slice plane, repetition time = 2,200 ms, echo time = 30 ms, flip angle = 75°, matrix = 64 × 64, field of view = 220 × 220 mm2, 40 slices with 2.4‐mm slice thickness, and 1‐mm gap; 300 volumes per run). The relatively short echo time was used to optimize imaging of subcortical areas. Two quality control procedures were implemented at each site: (1) The American College of Radiology phantom was scanned to provide information about geometric distortions and signal uniformity related to hardware differences in radiofrequency coils and gradient systems, image contrast, and temporal stability and (2) several healthy volunteers were regularly scanned at each site to determine inter‐site variability in structural and functional measures (e.g., tissue contrast in raw MRI signal, tissue relaxation properties). Further details of MRI acquisition and quality control procedures have been described previously (Schumann et al., 2010).

2.3. Monetary incentive delay task

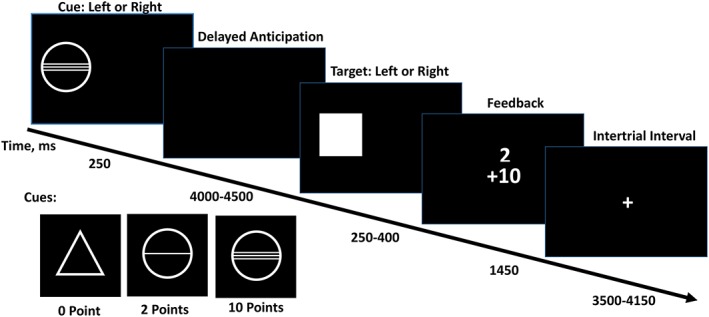

Participants performed a variant of the MID task, in which small and large monetary gains were indicated by different cues (see Figure 1). On each trial, an incentive cue indicating potential rewards was displayed on the left or right side of a black screen for 250 ms. There were three types of incentive cues (i.e., three within‐subject conditions): a circle with two lines (large reward: 10 points), a circle with one line (small reward; 2 points), and a triangle (no reward: 0 points). Subsequently, a blank black screen was presented for 4,000–4,500 ms, followed by a target screen in which participants were asked to respond to a target stimulus by pressing a button (with left or right hand). Responding too early or too late resulted in a failure to gain the points (i.e., reward miss). Responding within the response interval resulted in gaining the points (i.e., reward hit). The response interval was adjusted to produce a 66% success rate: the response interval was shortened if the success rate exceeded 66% (making the task more difficult), and lengthened if the success rate was below 66% (making the task easier). Then, the points won in this trial as well as the accumulated points won by previous trials were displayed. The response and feedback screens lasted a total of 2000 ms. The inter‐trial interval was 3,500–4,150 ms, during which a fixation cross was presented. There were 66 trials in total and 22 trials per condition.

Figure 1.

Stimuli in the monetary incentive delay (MID) task. Cues signaling the task condition (no reward, small reward, large reward) were displayed for 4,000 to 4,500 ms. the response and feedback phase lasted a total of 2 s, during which target was displayed for 250–400 ms and feedback was displayed for 1,450 ms. trials were separated by 3,500–4,150 ms intertrial interval [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.4. Puberty development

The pubertal status of adolescents was assessed using the computerized Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen, Crockett, & Richards, 1988), which is an 8‐item self‐report assessment of physical development. Pubertal status is estimated on a 5 point‐scale where 1 = prepubertal, 2 = beginning pubertal, 3 = midpubertal, 4 = advanced pubertal, 5 = postpubertal. Psytools (Delosis, London), an online platform for self‐assessment, was used to collect the pubertal measure.

2.5. Intelligence

Intelligence was assessed by a version of Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children WISC‐IV (Wechsler, 2003) with following subscales included: Perceptual Reasoning, consisting of Block Design (arranging bi‐colored blocks to duplicate a printed image) and Matrix Reasoning (a series of colored matrices are presented and the adolescent is asked to select the consistent pattern from a range of options); and Verbal Comprehension, consisting of Similarities (two similar but different objects or concepts are presented and the adolescent is asked to explain how they are alike or different) and Vocabulary (a picture is presented or a word is spoken aloud by the experimenter and the adolescent is asked to provide the name of the depicted object or to define the word).

2.6. Sensation seeking

Sensation seeking was measured with a 23‐item (4‐point Likert scale “1 = Strong Disagree” to “4 = Strongly Agree”) subscale in the Substance Use Risk Profile Scale (SURPS; Woicik, Stewart, Pihl, & Conrod, 2009). The SURPS assesses personality traits that confer risk for substance misuse and psychopathology. Four distinct and independent personality dimensions; anxiety sensitivity, hopelessness, sensation seeking, and impulsivity are measured by SURPS. The SURPS is a valid instrument for measuring sensation seeking (Schlauch et al., 2015).

2.7. fMRI preprocessing and analysis

Analyses were performed using Statistical Parametric Mapping software package (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London). The preprocessing was completed using SPM8 with the subsequent statistical analyses conducted using SPM12. Time series data were corrected for slice timing, then for movement, non‐linearly warped onto Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using a custom EPI template (53 × 63 × 46 voxels) created out of an average of the mean images of 400 adolescents, and Gaussian‐smoothed using a 5‐mm full‐width half‐maximum kernel. Automatic and visual (web‐based) quality control procedures of pre‐processed structural and functional MRI were implemented. Data were screened for normalization issues, segmentation issues, clinical abnormalities, motion artifacts, deformation, and susceptibility artifacts.

Eight conditions and six estimated movement parameters (three translations, three rotations) were included in the individual level general linear model (GLM), which used SPM's default hemodynamic response function (HRF). The conditions were: (i) the no‐reward cue, (ii) the small‐reward cue, (iii) the large‐reward cue, (iv) no reward (i.e., no‐reward hit and miss), (v) small‐reward hit, (vi) small‐reward miss, (vii) large‐reward hit, and (viii) large‐reward miss. In the group level analyses, gender, pubertal stage, handedness, and seven dummy‐coded acquisition sites were added in as nuisance covariates, unless otherwise stated. For all fMRI analyses, we used SPM's voxel‐wise FWE correction at p < .05. For interpretability (i.e., to exclude very small clusters) we also applied a cluster extent threshold of 10 contiguous voxels for connectivity maps and gender and puberty analyses. Results with cluster extent set to 1 are displayed in Supporting Information Tables S2–S7.

In the following group level and connectivity analyses, we focused on three specific contrasts. First, reward anticipation was estimated as large‐reward cue minus no‐reward cue. Second, reward receipt was estimated as large‐reward hit minus no reward. Third, infrequent reward omission was estimated as large‐reward miss minus large‐reward hit (i.e., the cue signaled a large reward was potentially available but the reward was not delivered). Previous studies have revealed the impact of reward magnitude on reward‐related responses, with larger reward eliciting greater activity in reward‐related regions (Bjork et al., 2010; Yacubian et al., 2006). Thus, we focused on the large reward to attain the maximal sensitivity to detect associations with reward‐relate neural response, which has been done in previous studies (Schneider, Brassen, et al., 2012a; Schneider, Peters, et al., 2012b).

2.7.1. Probabilistic mapping

For the activation analyses, results of the group‐level analyses with the whole sample of 1,510 participants were robust (e.g., a cluster with 37,258 voxels was suprathreshold for reward anticipation at a voxel‐wise FWE p < 10−11). Therefore, we adopted the probability mapping approach similar to Tahmasebi et al. (2012). Specifically, a random sample of 100 participants (50 males and 50 females) were selected from the whole sample and then entered into a group level analysis. Next, these t‐maps were thresholded at voxel‐wise FWE‐corrected p < .05, and binarized (i.e., 1 for significant, 0 for non‐significant). These steps were repeated 100 times with a new random sample of 100, for each iteration, which generated a set of 100 binarized t‐maps that were then averaged to obtain probabilistic maps. Regions showing probability of activation above 0.8 (i.e., over 80% of samples) were reported with peak probability, MNI coordinates and corresponding t value from normal group level results. If the peak probability of activation was the same for two or more voxels in the same region (e.g., two voxels with a probability of 1), the MNI coordinates for the voxel having highest t value were reported.

2.7.2. Connectivity mapping

Connectivity maps of seed regions during reward anticipation, receipt and PE were obtained by PPI analyses (Friston et al., 1997). The selection of seed regions was based on peak activity with respect to the probabilistic maps from the contrasts. If several regions showed the same peak probability of activation (e.g., several regions with a probability of 1 during reward anticipation), the region that had highest t value as well as its bilateral counterpart were selected as seed regions. Thus, chosen seed regions were bilateral thalamus (left: [−9, −19, 7] and right: [9, −19, 7]) for the reward anticipation, bilateral vmPFC (left: [−3, 41, 7] and right: [3, 41, 7]), and bilateral thalamus (left: [−9, −19, 7] and right: [9, −19, 7]) for reward receipt and bilateral VS (left: [−12, 14, −8] and right: [12, 14, −8]) for infrequent reward omission. In addition, bilateral VS (left: [−12, 14, −8] and right: [12, 14, −8]) were also included as seed regions for reward anticipation given that VS has been a region of interest in previous reward processing studies (Haber & Knutson, 2010; Liu et al., 2011; Loren, et al., 2014; Silverman et al., 2015). The selected MNI coordinates for the seed regions were slightly different from the peak voxel coordinates to keep the MIN coordinates consistent across conditions and hemisphere. Detailed statistical values for selected ROIs and regional peak coordinates are displayed in Supporting Information Table S1.

For the PPI analyses, the first eigenvariate of the time course within a 3‐mm radius sphere in each seed region was extracted, adjusted for effects of interest (i.e., effects of conditions) as the physiological factor. Variance in the eigenvarite attributable to head motion was removed. The psychological factors were defined as the contrast between conditions (i.e., reward anticipation: large reward cue minus no reward cue; reward receipt: large reward hit minus no reward; infrequent reward omission: large reward miss minus large reward hit). The psychophysiological interaction factors were calculated as an interaction term of the physiological factors and psychological factors using the PPI toolbox in SPM 12. Finally, a GLM model with the PPI regressors (physiological, psychological, and interaction factors) of the seed region together with estimated movement parameters was generated. The effects of psychophysiological interaction for each subject were estimated in the individual level GLM model and then specified in a group level GLM model together with other nuisance covariates (i.e., gender, pubertal stage, handedness, and seven dummy‐coded acquisition sites).

2.7.3. Computational modeling of reward PE

To further examine brain activations associated with reward prediction error, a Rescorla–Wagner algorithm based Reinforcement Learning model was trained using reward cues and outcomes (Glascher & O'Doherty, 2010; Rescorla & Wagner, 1972). The model contained two internal variables: Expected value (EV) representing the current estimation of the future expected rewards and Prediction error (PE) representing the difference between the current reward and the expected value.

where, C is the possible reward (0, 2, or 10 points), EV is expected value (EV), R is the actual reward, PE is prediction error, pGain is participant's subjective probability of obtaining the reward, η is learning rate, and t corresponds to trial t. For a certain trial (t), each participant's subjective expected value (EVt) is determined by the cue presented (C t) and the participant's subjective possibility of obtaining it (pGaint). The prediction error (PEt) is defined as the difference between the actual received reward (R t) and EVt. Following reward receipt, the subjective probability of obtaining reward for next trial (pGaint + 1) is a sum of pGaint and PEt divided by C t, with the latter multiplied by the learning rate (η). The initial probability (pGain) was set to 0.5 and the learning rate was assumed to be same for all subjects and set to 0.7 (Glascher & O'Doherty, 2010; O'Doherty, Dayan, Friston, Critchley, & Dolan, 2003). The EV and PE at each trial for each subject were obtained from the record of rewards delivered during the task. In the individual GLM model, cue, and outcome onsets were specified and parametrically modulated with trial‐wise EV and PE, respectively. The estimated head motion parameters were included as covariates. All regressors were convolved with the standard HRF in SPM12. Brain activations associated with reward PE were obtained by estimation of the parametric modulation effects of reward PE.

2.7.4. Gender and puberty analyses

Gender correlates (male vs. female) of adolescent brain response to reward processing were examined via two sample t‐tests with pubertal stage, handedness, and seven dummy‐coded acquisition sites included as nuisance covariates. For analyses of puberty, we focused on differences between early and late puberty stages (Menzies, Goddings, Whitaker, Blakemore, & Viner, 2015). Given that males and females reach puberty at different ages, we compared male early puberty (PDS Stage 2, n = 91) versus male late puberty (PDS Stage 4, n = 237) and female early puberty (PDS Stage 3, n = 80) versus female late puberty (PDS Stage 5, n = 84).

2.7.5. Sensation seeking

Sensation seeking scores were measured using a subscale of the SURPS (20 participants did not complete this measure and were not included in the sensation seeking analyses). Brain activation and functional connectivity during reward processing were correlated sensation seeking scores in a group level GLM model together with other nuisance covariates (i.e., gender, pubertal stage, handedness, and seven dummy‐coded acquisition sites). For comparison with Cservenka et al. (2013), adolescents were further stratified into high sensation seekers and low sensation seekers (bottom 33% vs. top 33%; scores below 14 and above 16, respectively). Brain activation and functional connectivity during reward processing was compared between two groups using two sample t‐test with other nuisance covariates regressed out.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 displays sample characteristics. For the large reward condition, participants completed an average of 14.82 (SD = 2.47) reward hit trials and 7.17 (SD = 2.45) reward miss trials. For the small reward condition, participants completed an average of 14.85 (SD = 2.33) reward hit trials and 7.14 (SD = 2.33) reward miss trials. The different counts between hit and miss trials were due to an adaptive response interval designed to provide a successful outcome on 66% of trials. For the no reward condition participants completed an average of 22.01 (SD = 0.16) trials (including both hit and miss). The mean sensation seeking score was 13.95 (SD = 2.69; n = 1,490) and the distribution of the sensation seeking scores is displayed in Supporting Information Figure S1. The mean sensation seeking score for high sensation seeking group was 17.19 (SD = 1.25; n = 416), low sensation seeking group was 10.73 (SD = 1.38; n = 434).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Whole sample | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n | 1,510 | 715 | 795 |

| Handedness, left/right, n | 166/1344 | 89/626 | 77/718 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 14.54 (0.44) | 14.53 (0.43) | 14.55 (0.45) |

| Verbal comprehension, mean (SD) | 111.13 (14.41) | 112.61 (14.20) | 109.79 (14.47) |

| Perceptual reasoning, mean (SD) | 108.48 (14.23) | 108.43 (14.62) | 108.52 (13.87) |

| Pubertal stage, n | |||

| Pre‐pubertal (1) | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| Beginning pubertal (2) | 92 | 91 | 1 |

| Mid‐pubertal (3) | 448 | 368 | 80 |

| Advanced pubertal (4) | 867 | 237 | 630 |

| Post‐pubertal (5) | 94 | 10 | 84 |

3.1. Reward anticipation

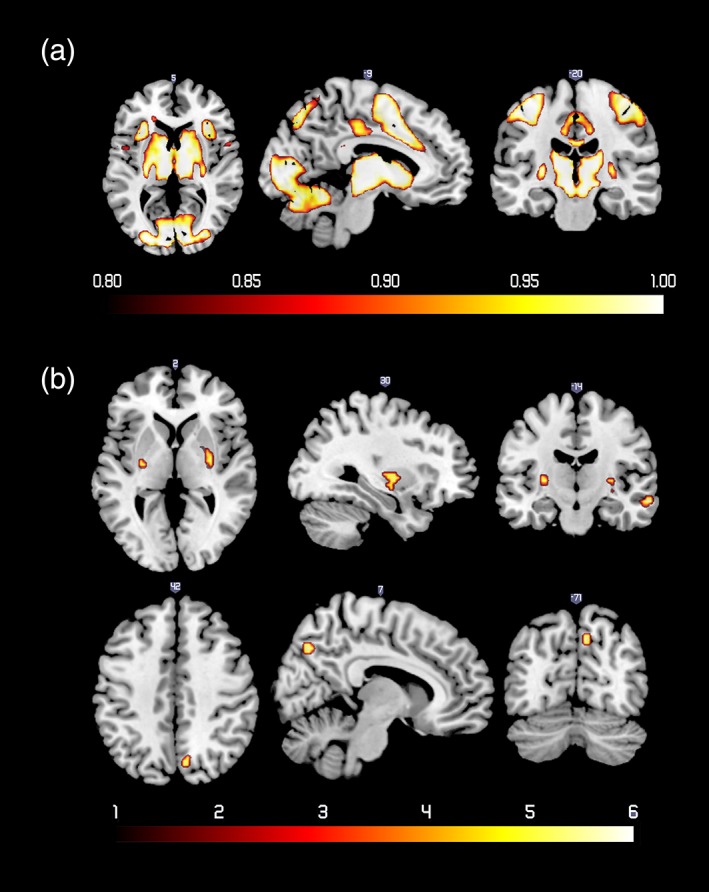

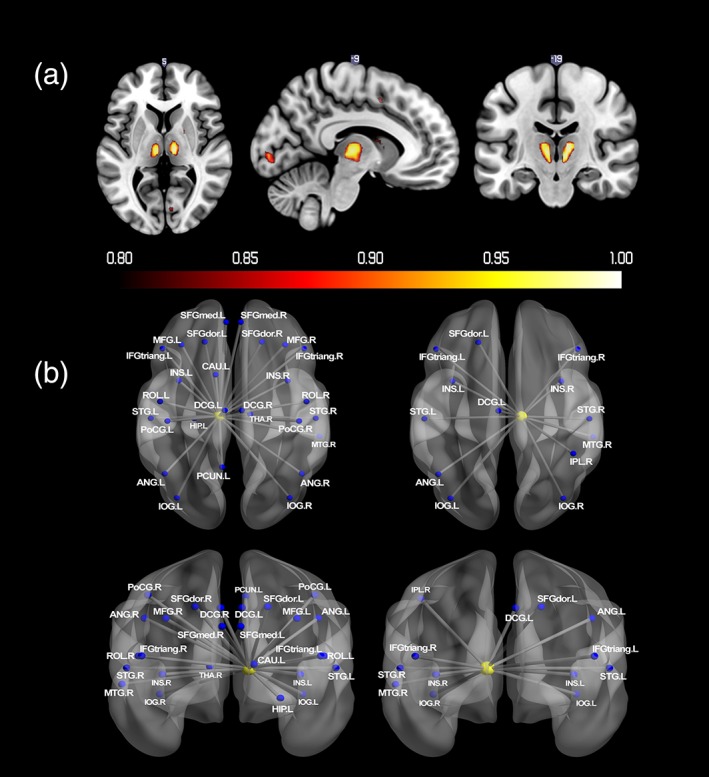

Several regions had greater than 0.8 probability of positive activation during reward anticipation (see Figure 2a and Table 2). Specifically, the activation of the midbrain included ventral tegmental area (VTA)/substantia nigra (SN) activation (left: peak probability: 1, MNI: −9, −16, −11; right: peak probability: 1, MNI: 9, −16, −11). No region had greater than 0.8 probability of negative activation. Figure 3a and Table 2 depict regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with thalamus during the anticipation of large reward versus no reward. Figure 3b and Table 2 depict regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with VS. Male adolescents had greater brain activity in bilateral putamen (left: t = 5.81, cluster size: 13, MNI: −30, −13, 4; right: t = 5.53, cluster size: 28, MNI: 30, −7, 1), right middle temporal gyrus (t = 6.13, cluster size: 22, MNI: 63, −16, −14), and right precuneus (t = 5.81, cluster size: 17, MNI: 9, −70, 40) than females in the reward anticipation (see Figure 2b). The sensation seeking analyses as well as other comparisons for gender and puberty, for either activation or connectivity, were non‐significant.

Figure 2.

(a) Probabilistic map of positive activation during reward anticipation. The color bar denotes the probability of activation. (b) Regions that showed more activity for male compared with female adolescents during reward anticipation. The color bar denotes t values [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 2.

Regions that showed probability of positive activation above 0.8 during reward anticipation (A) and significant changes in functional connectivity with thalamus and VS during reward anticipation (B)

| Region | Cluster size (voxels) | Peak | MNI (x,y,z) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Probabilistic map | ||||||||

| 1 | >0.9 | >0.8 | P (t) | |||||

| Superior frontal gyrus (L) | 5 | 31 | 49 | 1 (32.54) | −30 | −7 | 67 | |

| Superior frontal gyrus (R) | 7 | 61 | 88 | 1 (32.17) | 36 | −4 | 64 | |

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 6 | 15 | 39 | 1 (33.01) | −30 | −4 | 52 | |

| Middle frontal gyrus (R) | 24 | 35 | 56 | 1 (32.82) | 33 | −4 | 55 | |

| Olfactory cortex (L) | 3 | 6 | 6 | 1 (34.37) | −15 | 8 | −14 | |

| Olfactory cortex (R) | 3 | 4 | 6 | 1 (34.51) | 18 | 8 | −14 | |

| Thalamus (L) | 132 | 168 | 183 | 1 (49.00) | −12 | −19 | 10 | |

| Thalamus (R) | 126 | 159 | 165 | 1 (49.37) | 12 | −13 | 7 | |

| VS (L) | 5 | 6 | 8 | 1 (42.13) | −12 | 14 | −8 | |

| VS (R) | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 (44.92) | 12 | 14 | −8 | |

| Insula (L) | 15 | 71 | 97 | 1 (34.77) | −30 | 26 | 4 | |

| Insula (R) | 21 | 74 | 87 | 1 (35.10) | 33 | 29 | 4 | |

| Caudate (L) | 39 | 62 | 83 | 1 (47.13) | −9 | 11 | −2 | |

| Caudate (R) | 57 | 94 | 112 | 1 (48.41) | 9 | 11 | 1 | |

| Pallidum (L) | 7 | 24 | 27 | 1 (40.07) | −12 | 8 | −2 | |

| Pallidum (R) | 6 | 20 | 23 | 1 (35.14) | 12 | 5 | −2 | |

| Putamen (L) | 32 | 93 | 119 | 1 (42.49) | −15 | 11 | −8 | |

| Putamen (R) | 17 | 65 | 101 | 1 (42.29) | 18 | 17 | −8 | |

| Midbrain (L) | 95 | 133 | 157 | 1 (44.04) | −6 | −25 | −5 | |

| Midbrain (R) | 77 | 130 | 147 | 1 (47.04) | 6 | −25 | −5 | |

| Anterior cingulate gyri (L) | 6 | 28 | 42 | 1 (30.05) | −6 | 20 | 28 | |

| Anterior cingulate gyri (R) | 4 | 28 | 53 | 1 (29.71) | 6 | 23 | 28 | |

| Supplementary motor area (L) | 129 | 180 | 199 | 1 (43.14) | −6 | 5 | 49 | |

| Supplementary motor area (R) | 131 | 205 | 225 | 1 (42.71) | 6 | 5 | 49 | |

| Precentral gyrus (L) | 132 | 245 | 303 | 1 (36.72) | −36 | −25 | 61 | |

| Precentral gyrus (R) | 109 | 214 | 276 | 1 (34.88) | 42 | −16 | 52 | |

| Precuneus (L) | 6 | 45 | 72 | 1 (30.62) | −12 | −73 | 46 | |

| Precuneus (R) | 8 | 40 | 69 | 1 (30.65) | 15 | −73 | 46 | |

| Median cingulate gyri (L) | 58 | 119 | 144 | 1 (38.15) | −6 | 8 | 40 | |

| Median cingulate gyri (R) | 73 | 155 | 213 | 1 (39.86) | 6 | 11 | 43 | |

| Postcentral gyrus (L) | 142 | 219 | 258 | 1 (36.49) | −42 | −19 | 52 | |

| Postcentral gyrus (R) | 22 | 131 | 202 | 1 (33.20) | 42 | −22 | 52 | |

| Inferior parietal gyrus (L) | 14 | 149 | 200 | 1 (32.09) | −30 | −49 | 49 | |

| Inferior parietal gyrus (R) | 0 | 20 | 48 | 0.98 (25.85) | 30 | −49 | 49 | |

| Superior parietal gyrus (L) | 35 | 139 | 181 | 1 (30.20) | −15 | −70 | 52 | |

| Superior parietal gyrus (R) | 5 | 53 | 101 | 1 (31.55) | 12 | −70 | 52 | |

| Cuneus (L) | 2 | 11 | 27 | 1 (28.85) | 0 | −82 | 16 | |

| Cuneus (R) | 2 | 17 | 37 | 1 (28.89) | 18 | −91 | 10 | |

| Lingual gyrus (L) | 58 | 110 | 133 | 1 (37.85) | −12 | −88 | −8 | |

| Lingual gyrus (R) | 49 | 99 | 137 | 1 (39.63) | 15 | −88 | −5 | |

| Calcarine (L) | 102 | 140 | 155 | 1 (40.21) | −12 | −91 | −5 | |

| Calcarine (R) | 62 | 111 | 143 | 1 (40.99) | 15 | −91 | −2 | |

| Fusiform gyrus (L) | 13 | 31 | 54 | 1 (35.59) | −18 | −88 | −8 | |

| Fusiform gyrus (R) | 6 | 24 | 38 | 1 (31.22) | 24 | −82 | −14 | |

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | 24 | 36 | 56 | 1 (36.92) | −30 | −88 | −8 | |

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | 7 | 22 | 38 | 1 (32.66) | 33 | −85 | −2 | |

| Middle occipital gyrus (L) | 71 | 128 | 172 | 1 (38.17) | −27 | −91 | 1 | |

| Middle occipital gyrus (R) | 9 | 53 | 90 | 1 (32.60) | 33 | −85 | 1 | |

| Superior occipital gyrus (L) | 17 | 50 | 68 | 1 (34.56) | −12 | −94 | 4 | |

| Superior occipital gyrus (R) | 2 | 45 | 69 | 1 (29.31) | 24 | −88 | 10 | |

| Cerebellum (L) | 178 | 562 | 756 | 1 (35.83) | −33 | −52 | −32 | |

| Cerebellum (R) | 222 | 537 | 698 | 1 (34.86) | 18 | −52 | −23 | |

| B. Connectivity map | ||||||||

| Thalamus (L) positive | ||||||||

| Lingual gyrus (L/R) | 1,208 | 9.63 | 9 | −88 | 16 | |||

| Calcarine (L/R) | ||||||||

| Cuneus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Supplementary motor area (L/R) | 174 | 7.16 | 3 | 2 | 64 | |||

| Dorsal cingulate gyri (L/R) | ||||||||

| Insula (L) | 25 | 5.76 | −33 | 14 | 10 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, opercular part (R) | 10 | 5.46 | 33 | 23 | −8 | |||

| Insula (L) | 13 | 5.38 | −45 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Thalamus (L) negative | ||||||||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | 137 | 15.66 | −30 | −88 | −8 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | 165 | 15.04 | 21 | −88 | −11 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (R) | 83 | 6.93 | 57 | −7 | 28 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (L) | 67 | 6.55 | −51 | −10 | 31 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, opercular part (L) | 26 | 5.99 | −48 | 17 | 34 | |||

| Thalamus (R) positive | ||||||||

| Lingual gyrus (L/R) | 708 | 9.02 | 9 | −91 | 16 | |||

| Calcarine (L/R) | ||||||||

| Cuneus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Supplementary motor area (L/R) | 50 | 6.66 | 0 | 2 | 61 | |||

| Insula (L) | 33 | 6.23 | −33 | 17 | 10 | |||

| Dorsal cingulate gyri (L) | 24 | 5.66 | −6 | 14 | 37 | |||

| Insula (R) | 11 | 5.73 | 48 | 5 | 1 | |||

| Putamen (R) | 16 | 5.57 | 21 | 11 | 1 | |||

| Calcarine (R) | 10 | 5.07 | 24 | −64 | 13 | |||

| Thalamus (R) negative | ||||||||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | 195 | 16.76 | −27 | −88 | −8 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | 171 | 15.18 | 33 | −85 | −8 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (L) | 119 | 7.91 | −57 | −10 | 34 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (R) | 108 | 7.3 | 60 | −7 | 28 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 73 | 6.25 | −42 | 14 | 31 | |||

| Angular gyrus (R) | 67 | 6.14 | 39 | −70 | 40 | |||

| Precuneus (R) | 31 | 6.01 | 6 | −61 | 49 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (L) | 23 | 5.99 | −36 | −31 | 67 | |||

| Angular gyrus (L) | 68 | 5.72 | −33 | −67 | 37 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 15 | 5.36 | −33 | 17 | 55 | |||

| VS (L) positive | ||||||||

| Lingual gyrus (L/R) | 1,375 | 9.78 | 9 | −88 | 22 | |||

| Calcarine (L/R) | ||||||||

| Cuneus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Supplementary motor area (L/R) | 612 | 9.77 | 3 | 5 | 61 | |||

| Median cingulate gyri (L/R) | ||||||||

| Precentral gyrus (R) | 84 | 8.02 | 45 | −7 | 52 | |||

| Insula (L) | 40 | 7.67 | −30 | 20 | 10 | |||

| Precentral gyrus (L) | 84 | 7.37 | −42 | −7 | 55 | |||

| Putamen (R) | 85 | 7.33 | 21 | 14 | −2 | |||

| Median cingulate gyri (L) | 38 | 6.84 | −12 | −22 | 40 | |||

| Insula (L) | 48 | 6.55 | −45 | 11 | 1 | |||

| Thalamus (R) | 43 | 6.16 | 6 | −13 | −2 | |||

| Putamen (L) | 26 | 5.44 | −21 | 14 | −2 | |||

| Thalamus (L) | 16 | 6.05 | −6 | −22 | 4 | |||

| Superior temporal gyrus (L) | 11 | 5.66 | 51 | 11 | −2 | |||

| VS (L) negative | ||||||||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | 103 | 15.26 | −21 | −91 | −5 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | 104 | 13.72 | 33 | −85 | −8 | |||

| Angular gyrus (L) | 67 | 7.16 | −42 | −73 | 37 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (L) | 45 | 7.14 | −54 | −7 | 28 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (R) | 83 | 6.99 | 57 | −7 | 28 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (R) | 54 | 6.56 | 48 | 38 | 16 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, opercular part (L) | 51 | 6.52 | −45 | 17 | 34 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 59 | 6.40 | −30 | 23 | 55 | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus, medial orbital (R) | 41 | 5.99 | 6 | 47 | −11 | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus (R) | 37 | 5.86 | 30 | 26 | 55 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (L) | 31 | 5.71 | −45 | 35 | 10 | |||

| Angular gyrus (R) | 19 | 6.02 | 45 | −67 | 40 | |||

| Superior temporal gyrus (R) | 17 | 5.77 | 57 | −10 | 4 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (L) | 12 | 5.36 | −54 | 26 | 7 | |||

| Anterior cingulate gyri (L) | 11 | 4.98 | −6 | 38 | 1 | |||

| VS (R) positive | ||||||||

| Supplementary motor area (L/R) | 884 | 10.44 | 0 | −1 | 61 | |||

| Median cingulate gyri (L/R) | ||||||||

| Lingual gyrus (L/R) | 1,595 | 10.41 | 9 | −88 | 22 | |||

| Calcarine (L/R) | ||||||||

| Cuneus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Precentral gyrus (R) | 122 | 8.16 | 42 | −10 | 55 | |||

| Insula (L) | 119 | 7.85 | −33 | 20 | 10 | |||

| Thalamus (L) | 58 | 7.36 | −6 | −22 | 7 | |||

| Precentral gyrus (L) | 78 | 6.98 | −36 | −7 | 46 | |||

| Thalamus (R) | 89 | 6.66 | 6 | −16 | 1 | |||

| Insula (R) | 61 | 6.42 | 33 | 26 | 7 | |||

| Putamen (R) | 73 | 6.30 | 21 | 11 | −2 | |||

| Putamen (L) | 57 | 6.09 | −12 | 8 | −2 | |||

| Precentral gyrus (L) | 13 | 6.45 | −51 | −1 | 43 | |||

| Inferior parietal gyrus (L) | 11 | 5.46 | −24 | −52 | 52 | |||

| VS (R) negative | ||||||||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | 107 | 14.61 | −30 | −88 | −8 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | 98 | 14.51 | 33 | −85 | −8 | |||

| Angular gyrus (L) | 38 | 7.33 | −42 | −73 | 34 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (R) | 45 | 6.54 | 57 | −7 | 31 | |||

| Angular gyrus (R) | 28 | 6.08 | 48 | −67 | 37 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (L) | 21 | 5.66 | −54 | −10 | 31 | |||

| Superior temporal gyrus (R) | 18 | 5.96 | 60 | −7 | 4 | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus, medial orbital (R) | 18 | 5.68 | 9 | 50 | −11 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (R) | 11 | 5.68 | 30 | 20 | 58 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, opercular part (L) | 13 | 5.61 | −39 | 17 | 31 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 14 | 5.31 | −30 | 23 | 55 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (L) | 15 | 5.30 | −45 | 38 | −2 | |||

The number of voxels exceeding the threshold for probabilities of 0.8, 0.9, and 1 from each cluster are presented, in addition to the maximum t value and corresponding MNI coordinates. Main regions within the cluster, cluster size, peak t‐value within the cluster as well as the corresponding MNI coordinates for the clusters with cluster size above 10 are shown in the table (L, left; R, right; L/R, bilateral).

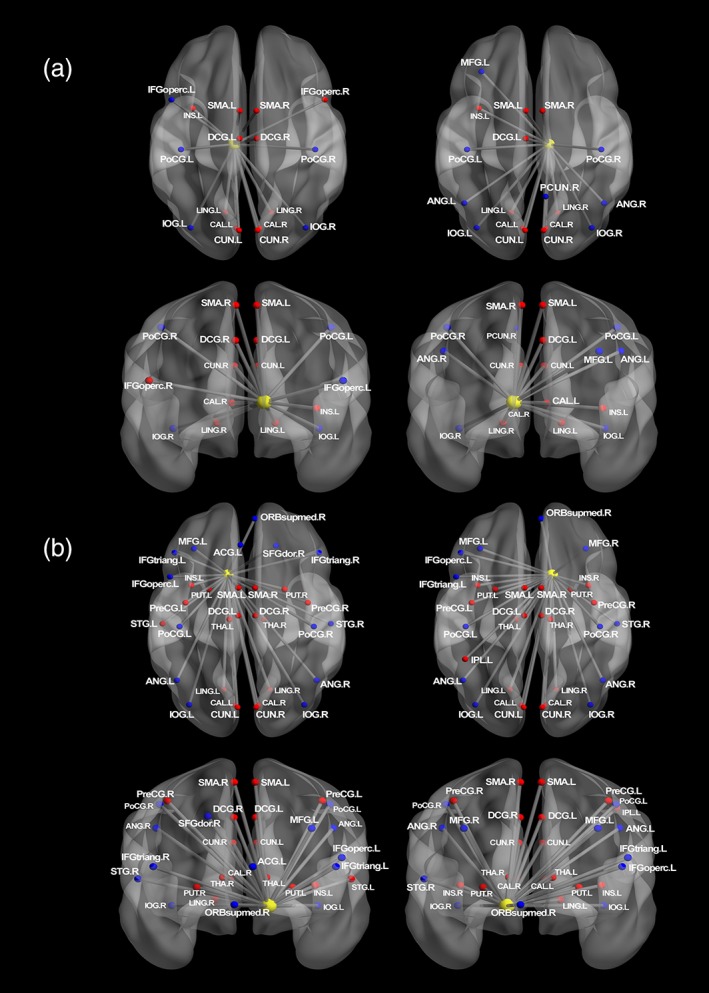

Figure 3.

(a) Regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with left and right thalamus during reward anticipation. (b) Regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with left and right VS during reward anticipation. The connectivity maps were generated using BrainNet viewer (Xia, Wang, & He, 2013). Nodes drawn in red indicate regions showed positive connectivity with the seed region. Blue indicates negative connectivity. Unified MNI coordinates are used for the display purpose. The MNI coordinates used for plots are shown in the Supporting Information Materials. ANG, angular gyrus; ACG, anterior cingulate gyri; CAL, calcarine; CAU, caudate; CUN, cuneus; IFGoperc, inferior frontal gyrus; opercular part, IFGtriang, inferior frontal gyrus; triangular part; IOG, inferior occipital gyrus; IPL, inferior parietal gyrus; INS, insula; LING, lingual gyrus; DCG, median cingulate gyri; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; PoCG, postcentral gyrus; PreCG, precentral gyrus; PUT, putamen; SFGdor, superior frontal gyrus; ORBsupmed, superior frontal gyrus; medial orbital; STG, superior temporal gyrus; SMA, supplementary motor area; THA, thalamus; L, left; R, right [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

A previous study (Silverman et al., 2015) examined activation likelihood estimation (ALE) for brain regions across 26 studies of adolescent reward processing and reported that the anticipation of positive rewards activated ventral striatum, OFC, insula, paracingulate gyrus, posterior cingulate gyrus, and lateral occipital cortex, all of which were also activated in our study. In addition to the regions described by Silverman et al., we also observed reliable activation in bilateral middle frontal gyrus, medial occipital cortex, and parietal lobe. These additional observed regions are likely due to the use of a single standardized task across all participants. Silverman et al.’s (2015) findings were derived from a meta‐analysis of different studies with an array of reward‐processing tasks, whereas the activation patterns reported here are derived from the MID task alone using probability mapping on samples of 100 participants. Brain areas identified in our study, with 14‐year‐old adolescents, were previously reported in a meta‐analysis of reward‐related activation in healthy adults (Liu et al., 2011).

With respect to the PPI analysis of reward anticipation, both thalamus and VS showed similar positive connections to anterior supplementary motor area (pre‐SMA), dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), left anterior insula, and medial occipital lobe. The pre‐SMA and dACC are related to the control of movement and action initiation (Asemi, Ramaseshan, Burgess, Diwadkar, & Bressler, 2015; Srinivasan, et al., 2013), with evidence from a primate study showing that SMA and pre‐SMA are targets of basal ganglia circuit (Akkal, Dum, & Strick, 2007). Therefore, the positive connectivity with pre‐SMA and dACC likely reflects the increased motor preparation following the presentation of relatively large monetary cues. The anterior insula can relate to the interpretation of reward salience; that is, the insula is associated with the bottom‐up processing of events such as the differential value of reward cues (Menon & Uddin, 2010). A previous meta‐analysis showed that insula activity, particularly in left insula, relates to the motivational or affective salience of environmental events (Craig & Craig, 2009; Duerden, Arsalidou, Lee, & Taylor, 2013). Therefore, positive connectivity between VS/thalamus and left insula could indicate the integration of information about the motivational significance of cue. Thalamus and VS were both positively connected with medial occipital regions such as lingual gyrus, calcarine sulcus, cuneus, but negatively with inferior occipital lobe. This connectivity might represent value‐driven attention capture whereby the evaluative strength of an event influences visual information processing (Anderson, 2016, 2017). Specifically, the positive connections between seed and occipital regions could be attributed to differences in saliency between large reward and no reward stimulus.

3.2. Reward receipt: Positive activation

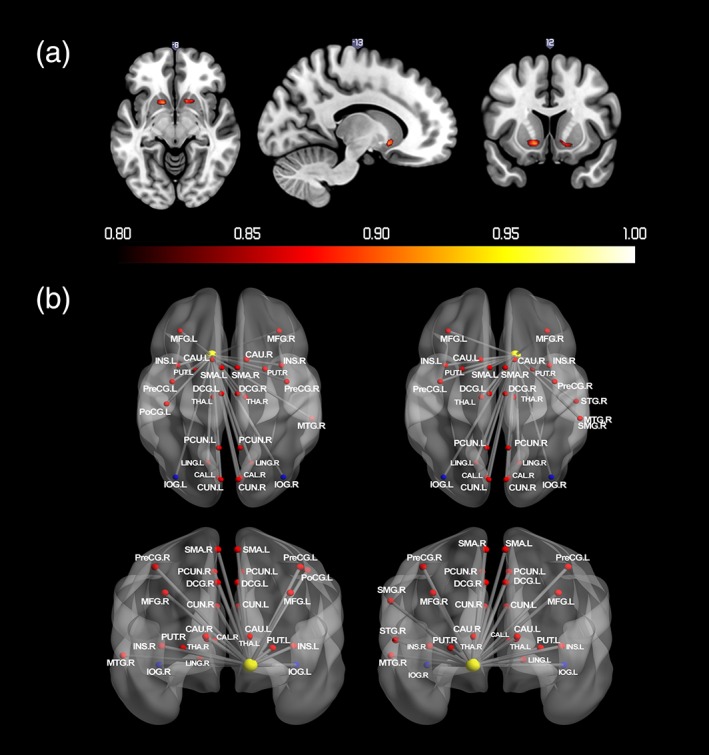

Bilateral vmPFC were the only regions to have greater than 0.8 probability of activation for reward receipt; see Figure 4a and Table 3. Figure 4b and Table 3 report regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with vmPFC during the reward receipt. None of the comparisons for gender and puberty or with sensation seeking, with either activation or connectivity, were significant.

Figure 4.

(a) Probabilistic map for positive activation during reward receipt. The color bar denotes the probability of activation. (b) Regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with vmPFC during reward receipt. Nodes drawn in red indicate regions showed positive connectivity with the seed region. Blue indicates negative connectivity. Unified MNI coordinates are used for the display purpose. The MNI coordinates used for plots are shown in the Supporting Information Materials. ACG, anterior cingulate gyri; CAL, calcarine; CAU, caudate; CUN, cuneus; DS, dorsal striatum; HIP, hippocampus; IFGoperc, inferior frontal gyrus; opercular part; IFGtriang, inferior frontal gyrus; triangular part; IOG, inferior occipital gyrus; INS, insula; LING, lingual gyrus; DCG, median cingulate gyri; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; MOG, middle occipital gyrus; PreCG, precentral gyrus; PCUN, Precuneus; PUT, putamen; SMA, supplementary motor area; THA, thalamus; L, left; R, right [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 3.

Regions that showed probability of positive activation above 0.8 during reward receipt (A) and significant changes in functional connectivity with vmPFC during reward receipt (B)

| Region | Cluster size (voxels) | Peak | MNI (x,y,z) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Probabilistic map | ||||||||

| 1 | >0.9 | >0.8 | P (t) | |||||

| vmPFC (L) | 0 | 5 | 19 | 0.97 (25.83) | 0 | 38 | 10 | |

| vmPFC (R) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.88 (23.53) | 3 | 41 | 7 | |

| B. Connectivity map | ||||||||

| vmPFC (L) positive | ||||||||

| Middle occipital gyrus (L) | 302 | 18.48 | −27 | −88 | −11 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | ||||||||

| Middle occipital gyrus (R) | 302 | 18.44 | 21 | −88 | −11 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | ||||||||

| Hippocampus (L) | 12 | 7.15 | 24 | −28 | −2 | |||

| Angular gyrus (R) | 94 | 6.86 | 30 | −70 | 28 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (R) | 24 | 6.02 | 54 | 23 | 22 | |||

| Median cingulate gyri (R) | 19 | 5.58 | 3 | −22 | 31 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, opercular part (R) | 12 | 5.22 | 51 | 14 | 34 | |||

| vmPFC (L) negative | ||||||||

| Cuneus (L/R) | 674 | 9.94 | −9 | −76 | −5 | |||

| Calcarine (L/R) | ||||||||

| Lingual gyrus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Supplementary motor area (L) | 299 | 8.91 | −6 | 2 | 58 | |||

| Insula (L) | 153 | 6.83 | −21 | 8 | 10 | |||

| Dorsal striatum (L) | ||||||||

| Precentral gyrus (L) | 103 | 6.67 | −42 | −10 | 49 | |||

| Insula (R) | 19 | 6.83 | 36 | 14 | 7 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (R) | 20 | 6.26 | 39 | −7 | 52 | |||

| Precuneus (L) | 23 | 5.98 | −9 | −58 | 61 | |||

| Thalamus (R) | 17 | 5.71 | −15 | −28 | 22 | |||

| Calcarine (R) | 27 | 5.62 | 33 | −55 | 1 | |||

| Lingual gyrus (R) | 11 | 5.54 | 18 | −46 | −8 | |||

| Putamen (R) | 12 | 5.33 | 24 | 8 | 7 | |||

| Superior parietal gyrus (R) | 10 | 5.19 | 18 | −58 | 61 | |||

| vmPFC (R) positive | ||||||||

| Middle occipital gyrus (L) | 265 | 18.3 | −27 | −88 | −11 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | ||||||||

| Middle occipital gyrus (R) | 278 | 17.67 | 21 | −88 | −11 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | ||||||||

| Middle occipital gyrus (R) | 51 | 6.64 | 30 | −70 | 28 | |||

| vmPFC (R) negative | ||||||||

| Cuneus (L/R) | 852 | 10.04 | −6 | −79 | −5 | |||

| Calcarine (L/R) | ||||||||

| Lingual gyrus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Supplementary motor area (L/R) | 522 | 9.2 | −6 | 5 | 55 | |||

| Precentral gyrus (L) | ||||||||

| Precuneus (L) | 80 | 7.24 | −9 | −58 | 61 | |||

| Precentral gyrus (R) | 61 | 7.12 | 42 | −4 | 52 | |||

| Insula (L) | 54 | 6.38 | −39 | 11 | 7 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 29 | 6.3 | −33 | 38 | 31 | |||

| Precuneus (R) | 44 | 6.24 | 9 | −52 | 58 | |||

| Dorsal striatum (L) | 29 | 6.13 | −21 | 8 | 10 | |||

| Caudate (L) | 15 | 5.82 | 3 | 8 | 13 | |||

| Insula (R) | 10 | 5.78 | 36 | 14 | 7 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (R) | 22 | 5.64 | 30 | 35 | 31 | |||

The number of voxels exceeding the threshold for probabilities of 0.8, 0.9, and 1 from each cluster are presented, in addition to the maximum t value and corresponding MNI coordinates. Main regions within the cluster, cluster size, peak t‐value within the cluster as well as the corresponding MNI coordinates for the clusters with cluster size above 10 are shown in the table (L, left; R, right; L/R, bilateral).

In the present study, only vmPFC was positively reliably activated during reward receipt. This finding strongly supports the notion that activity in vmPFC represent outcome value (Peters & Büchel, 2010; Smith et al., 2010), in both general and specific reward valuation (Levy & Glimcher, 2011), and especially, the magnitude during reward receipt (Diekhof et al., 2012). For instance, the majority of previous studies using MID task reported the increased activation of vmPFC area in response to reward receipt (Bjork et al., 2004, 2010; Knutson, Fong, Bennett, Adams, & Hommer, 2003); and the activity showed a positive correlation with the subjective pleasantness of different type of rewards: taste in the mouth and warmth on the hand (Grabenhorst, D'Souza, Parris, Rolls, & Passingham, 2010). Therefore, the activation of vmPFC would reflect the selectively active for reward magnitude. It is worth noting that the observed positive activation in vmPFC during reward receipt appears inconsistent with previous adolescent studies showing reliable VS activation during reward receipt (Shulman et al., 2016), or absence of higher cortical activation related to reward (Silverman et al., 2015). However, these differences may be explained by differences in the nature of the rewarding outcome. For example, Silverman et al.’s analysis focused on situations in which the reward outcome stage provided feedback about gains or losses. In our study, the contrast for reward receipt involved a condition in which participants knew that the outcome would likely be a reward versus a condition in which it was known for certain that no reward would be provided. The observation of activity in vmPFC, but not VS, during reward receipt is consistent with previous adult findings (Knutson et al., 2003; Rohe et al., 2012) in this respect. Regarding the PPI results of reward receipt, bilateral vmPFC was negatively connected with bilateral insula and dorsal striatum. The anterior insula relates to the interpretation of reward salience (Menon & Uddin, 2010). Therefore, one possible explanation for vmPFC and insula connections would be that the connections may reflect the bottom‐up processing of the differential value of reward outcome. Previous studies have dissociated roles of ventral and dorsal striatum and demonstrated that dorsal striatum is involved in maintaining information about the rewarding outcomes (Balleine, Delgado, & Hikosaka, 2007; O'Doherty et al., 2004). The vmPFC and dorsal striatum connectivity may indicate learning of the reward results. Interestingly, left vmPFC was positively connected to right dlPFC. Rudorf and Hare (2014) showed that dlPFC encoded deviations from the default valuation context, and functional connectivity between vmPFC and dlPFC increased when choice context changes require a reweighting of the stimulus (Rudorf & Hare, 2014). Thus, functional coupling between right dlPFC and left vmPFC could indicate context‐dependent valuation during reward receipt.

3.3. Reward receipt: Negative activation

As shown in Figure 5a and Table 4, bilateral thalamus had greater than 0.8 probability of negative activation following reward receipt. Figure 5b and Table 4 depict regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with thalamus during reward receipt. None of the comparisons for gender and puberty, or with sensation seeking, with either activation or connectivity, were significant.

Figure 5.

(a) Probabilistic map for negative activation during reward receipt. The color bar denotes the probability of activation. (b) Regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with thalamus during reward receipt. Nodes drawn in red indicate regions showed positive connectivity with the seed region. Blue indicates negative connectivity. Unified MNI coordinates are used for the display purpose. The MNI coordinates used for plots are shown in the Supporting Information Materials. ANG, angular gyrus; HIP, hippocampus; IFGtriang, inferior frontal gyrus; triangular part; IOG, inferior occipital gyrus; IPL, inferior parietal gyrus; INS, insula; DCG, median cingulate gyri; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; PoCG, postcentral gyrus; PCUN, precuneus; ROL, rolandic operculum; SFGdor, superior frontal gyrus; SFGmed, superior frontal gyrus; medial; STG, superior temporal gyrus; THA, thalamus; L, left; R, right [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 4.

Regions that showed probability of negative activation above 0.8 during reward receipt (A) and significant changes in functional connectivity with thalamus during reward receipt (B)

| Region | Cluster size (voxels) | Peak | MNI (x,y,z) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Probabilistic map | ||||||||

| 1 | >0.9 | >0.8 | P (t) | |||||

| Thalamus (L) | 2 | 47 | 67 | 1.00 (29.97) | −6 | −22 | −2 | |

| Thalamus (R) | 3 | 41 | 57 | 1.00 (28.18) | 9 | −19 | 10 | |

| Supramarginal gyrus (R) | 5 | 27 | 44 | 1.00 (26.94) | 60 | −46 | 37 | |

| Supplementary motor area (L) | 0 | 2 | 13 | 0.95 (25.90) | −6 | 2 | 52 | |

| Supplementary motor area (R) | 2 | 19 | 31 | 1.00 (27.55) | 6 | 5 | 55 | |

| Angular gyrus (R) | 0 | 4 | 10 | 0.95 (26.53) | 60 | −52 | 28 | |

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0.88 (23.98) | −36 | 41 | 31 | |

| Caudate (R) | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0.91 (24.22) | 12 | 2 | 16 | |

| Calcarine (L) | 0 | 1 | 16 | 0.91 (23.86) | −9 | −88 | −5 | |

| Calcarine (R) | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.86 (23.79) | 9 | −82 | 1 | |

| Lingual gyrus (R) | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0.93 (24.73) | 9 | −79 | −2 | |

| B. Connectivity map | ||||||||

| Thalamus (L) negative | ||||||||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | 214 | 10.77 | −30 | −88 | −8 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | 260 | 10.36 | 21 | −88 | −11 | |||

| Superior temporal gyrus (R) | 869 | 9.31 | 48 | −13 | 16 | |||

| Insula (R) | ||||||||

| Rolandic operculum (R) | ||||||||

| Postcentral gyrus (R) | ||||||||

| Superior temporal gyrus (L) | 1,619 | 9.09 | 0 | −25 | 13 | |||

| Rolandic operculum (L) | ||||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (L) | ||||||||

| Insula (L) | ||||||||

| Postcentral gyrus (L) | ||||||||

| Angular gyrus (L) | 103 | 7.89 | −48 | −67 | 34 | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus (L/R) | 536 | 7.65 | −18 | 35 | 46 | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus, medial (L/R) | ||||||||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | ||||||||

| Cerebellum (L) | 30 | 6.86 | −3 | −43 | −26 | |||

| Cerebellum (R) | 33 | 6.84 | 24 | −34 | −26 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (L) | 61 | 6.51 | −30 | −40 | 61 | |||

| Precuneus (L) | 70 | 6.42 | −3 | −55 | 7 | |||

| Cerebellum (L) | 15 | 6.39 | −27 | −37 | −29 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (R) | 23 | 6.28 | 36 | 23 | 49 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (R) | 26 | 6.26 | 24 | −40 | 67 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (R) | 83 | 6.26 | 48 | 41 | 19 | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus (R) | 43 | 6.05 | 12 | 41 | 52 | |||

| Middle temporal gyrus (R) | 16 | 5.98 | 60 | −10 | −14 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (R) | 65 | 5.94 | 42 | −34 | 61 | |||

| Angular gyrus (R) | 44 | 5.89 | 36 | −73 | 37 | |||

| Thalamus (R) | 18 | 5.88 | 18 | −31 | −2 | |||

| Insula (R) | 22 | 5.88 | 21 | 29 | 13 | |||

| Thalamus (R) | 13 | 5.76 | 24 | −28 | 16 | |||

| Median cingulate gyri (L/R) | 40 | 5.67 | 6 | −4 | 37 | |||

| Caudate (L) | 13 | 5.47 | 18 | 11 | 22 | |||

| Hippocampus (L) | 13 | 5.45 | −33 | −37 | −5 | |||

| Thalamus (R) negative | ||||||||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | 118 | 10.42 | −30 | −88 | −8 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | 195 | 9.32 | 21 | −88 | −11 | |||

| Superior temporal gyrus (R) | 377 | 8.03 | 54 | −28 | 16 | |||

| Insula (R) | ||||||||

| Superior temporal gyrus (L) | 519 | 6.84 | −54 | −7 | 4 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (L) | ||||||||

| Insula (L) | ||||||||

| Cerebellum (R) | 25 | 6.31 | 27 | −34 | −26 | |||

| Inferior frontal gyrus, triangular part (R) | 64 | 6.02 | 51 | 38 | 16 | |||

| Angular gyrus (L) | 11 | 5.74 | −48 | −67 | 34 | |||

| Median cingulate gyri (L) | 19 | 5.66 | 0 | −4 | 37 | |||

| Inferior parietal gyrus (R) | 10 | 5.47 | 54 | −31 | 55 | |||

| Middle temporal gyrus (R) | 15 | 5.40 | 66 | −37 | 1 | |||

| Superior frontal gyrus (L) | 23 | 5.31 | −15 | 38 | 46 | |||

The number of voxels exceeding the threshold for probabilities of 0.8, 0.9, and 1 from each cluster are presented, in addition to the maximum t value and corresponding MNI coordinates. Main regions within the cluster, cluster size, peak t‐value within the cluster as well as the corresponding MNI coordinates for the clusters with cluster size above 10 are shown in the table (L, left; R, right; L/R, bilateral).

The negative activity following reward receipt is likely because the no reward condition could be regarded as a negative outcome when compared with large reward outcome. This could, therefore, contribute to increased activation of brain networks associated with negative emotion when compared with a large reward. For example, Santesso et al. (2012) reported that negative feedback on MID task was associated with greater self‐reported negative emotionality. Therefore, it is plausible that a no‐reward outcome would be associated with increased thalamic activity given that thalamus serves as an information hub that conveys information between subcortical and cortical regions (Haber & Calzavara, 2009; Haber & Knutson, 2010). For instance, the negative connectivity between thalamus and prefrontal cortex when no reward is anticipated could reflect the regulation of the negative arousal associated given prefrontal cortex's role in regulation of emotional, motivational, and cognitive arousal (Diamond, 2013; Hampshire, Chamberlain, Monti, Duncan, & Owen, 2010).

3.4. Infrequent reward omission

As shown in Figure 6a and Table 5, bilateral VS showed greater than 0.8 probability of negative activation when a signaled reward was not delivered. No region had greater than 0.8 probability of positive activation. Figure 6b and Table 5 depict regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with VS when a signaled reward was not delivered. None of comparisons for gender and puberty, or with sensation seeking, with either activation or connectivity, were significant.

Figure 6.

(a) Probabilistic map for negative activation during infrequent reward omission. The color bar denotes the probability of activation. (b) Regions that showed significant changes in functional connectivity with VS during infrequent reward omission. Nodes drawn in red indicate regions showed positive connectivity with the seed region. Blue indicates negative connectivity. Unified MNI coordinates are used for the display purpose. The MNI coordinates used for plots are shown in the Supporting Information Materials. CAL, calcarine; CAU, caudate; CUN, cuneus; IOG, inferior occipital gyrus; INS, insula; LING, lingual gyrus; DCG, median cingulate gyri; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; MTG, middle temporal gyrus; PoCG, postcentral gyrus; PCG, posterior cingulate gyrus; PreCG, precentral gyrus; PCUN, precuneus; PUT, putamen; SMA, supplementary motor area; SMG, supramarginal gyrus; L, left; R, right [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 5.

Regions that showed probability of negative activation above 0.8 during infrequent reward omission (A), probability of positive activation above 0.8 in response to the parametric modulation of reward PE (B), and significant changes in functional connectivity with VS during infrequent reward omission (C)

| Region | Cluster size (voxels) | Peak | MNI (x,y,z) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Probabilistic map | ||||||||

| 1 | >0.9 | >0.8 | P (t) | |||||

| VS (L) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.89 (24.11) | −12 | 14 | −8 | |

| VS (R) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0.92 (25.13) | 12 | 14 | −8 | |

| Putamen (L) | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0.91 (23.79) | −18 | 14 | −5 | |

| Putamen (R) | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0.92 (24.20) | 18 | 14 | −8 | |

| Inferior parietal gyrus (L) | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.88 (24.73) | −30 | −70 | 43 | |

| B. Probabilistic map for reward PE | ||||||||

| VS (L) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.87 (33.52) | −12 | 14 | −8 | |

| VS (R) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.90 (35.70) | 12 | 14 | −8 | |

| C. Connectivity map | ||||||||

| VS (L) positive | ||||||||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | 52 | 8.1 | −21 | −91 | −5 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | 37 | 7.43 | 21 | −88 | −11 | |||

| VS (L) negative | ||||||||

| Lingual gyrus (L/R) | 1,129 | 8.53 | −9 | −73 | −2 | |||

| Calcarine (L/R) | ||||||||

| Cuneus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Precuneus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Putamen (L) | 418 | 8.52 | −21 | 8 | 1 | |||

| Caudate (L) | ||||||||

| Insula (L) | ||||||||

| Supplementary motor area (L/R) | 1,156 | 8.22 | 6 | 5 | 55 | |||

| Median cingulate gyri (L/R) | ||||||||

| Precentral gyrus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Putamen (R) | 354 | 7.98 | 21 | 8 | −8 | |||

| Caudate (R) | ||||||||

| Middle temporal gyrus (R) | 256 | 6.81 | 48 | −61 | 16 | |||

| Thalamus (R) | 37 | 6.57 | 9 | −19 | 4 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 67 | 5.87 | −36 | 41 | 34 | |||

| Insula (R) | 16 | 5.87 | 33 | −25 | 13 | |||

| Insula (R) | 26 | 5.75 | 51 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Thalamus (L) | 30 | 5.64 | −12 | −22 | 10 | |||

| Postcentral gyrus (L) | 19 | 5.53 | −57 | −22 | 31 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 23 | 5.52 | −24 | 53 | 7 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (R) | 25 | 5.36 | 33 | 41 | 40 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 11 | 5.36 | −39 | 47 | 19 | |||

| Precentral gyrus (R) | 30 | 5.33 | 24 | −25 | 55 | |||

| VS (R) positive | ||||||||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (L) | 51 | 8.37 | −21 | −91 | −5 | |||

| Inferior occipital gyrus (R) | 51 | 7.32 | 21 | −88 | −11 | |||

| VS (R) negative | ||||||||

| Lingual gyrus (L/R) | 2,519 | 9.64 | 9 | −76 | −5 | |||

| Calcarine (L/R) | ||||||||

| Cuneus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Precuneus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Supplementary motor area (L/R) | ||||||||

| Precentral gyrus (L/R) | ||||||||

| Median cingulate gyri (L/R) | ||||||||

| Putamen (L) | 452 | 8.64 | −18 | 8 | −2 | |||

| Caudate (L) | ||||||||

| Insula (L) | ||||||||

| Putamen (R) | 360 | 7.71 | 21 | 8 | −8 | |||

| Caudate (R) | ||||||||

| Insula (R) | ||||||||

| Middle temporal gyrus (R) | 179 | 7.14 | 54 | −58 | 16 | |||

| Thalamus (R) | 56 | 7.11 | 9 | −19 | 4 | |||

| Thalamus (L) | 50 | 6.77 | −9 | −22 | 4 | |||

| Lingual gyrus (R) | 23 | 6.38 | 21 | −49 | −8 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (L) | 67 | 6.15 | −33 | 41 | 31 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus (R) | 33 | 5.7 | 30 | 38 | 34 | |||

| Supramarginal gyrus (R) | 65 | 5.68 | 63 | −46 | 22 | |||

| Precentral gyrus (R) | 55 | 5.57 | 24 | −34 | 67 | |||

| Insula (R) | 13 | 5.41 | 36 | −31 | 19 | |||

| Superior temporal gyrus (R) | 11 | 5.27 | 60 | −34 | 13 | |||

The number of voxels exceeding the threshold for probabilities of 0.8, 0.9, and 1 from each cluster are presented, in addition to the maximum t value and corresponding MNI coordinates. Main regions within the cluster, cluster size, peak t‐value within the cluster as well as the corresponding MNI coordinates for the clusters with cluster size above 10 are shown in the table (L, left; R, right; L/R, bilateral).

Bilateral VS showed negative activation when a signaled reward was not delivered, commensurate with previous studies (McClure, Berns, & Montague, 2003; O'Doherty, et al., 2003). These findings are concordant with previous evidence suggesting the fundamental role of VS lies in tracking the delivery of anticipated rewards and generation of PE signals: a process that is crucial to reinforcement learning (Den Ouden, Kok, & de Lange, 2012; Schultz, 2016). When comparing infrequent reward omission to frequent reward delivery, the PPI revealed bilateral VS positive connections with medial frontal gyrus, dACC, pre‐SMA, precentral gyrus, putamen, insula, thalamus, precuneus, cuneus, lingual gyrus, and calcarine sulcus. A previous review suggested that the processing of discrepancy between expected and unexpected rewards are widely associated with perception, attention, motivation, and control network of the brain (Den Ouden, et al., 2012), and the observed connections with VS are evidence for the involvement of this broader brain network. For example, the heightened connectivity between VS and prefrontal cortex during infrequent reward omission could reflect the adjustment of outcome expectancies during the process of reinforcement learning (Van den Bos, et al., 2012). The more connection between VS and motor areas would reflect the inhibition of actions. The VS connections with lingual gyrus, calcarine sulcus, and cuneus implies the involvement of the attention network in the processing of infrequent reward omission.

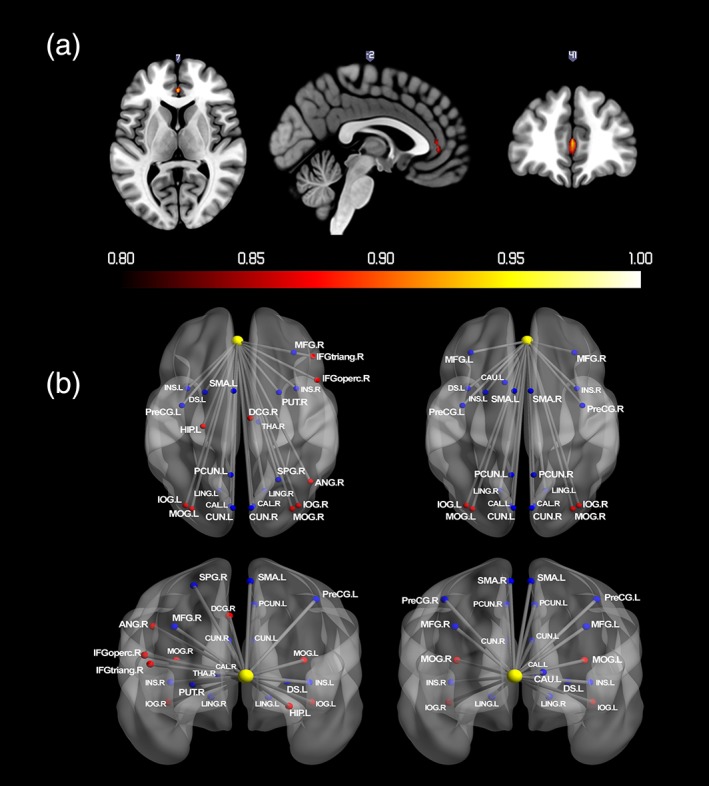

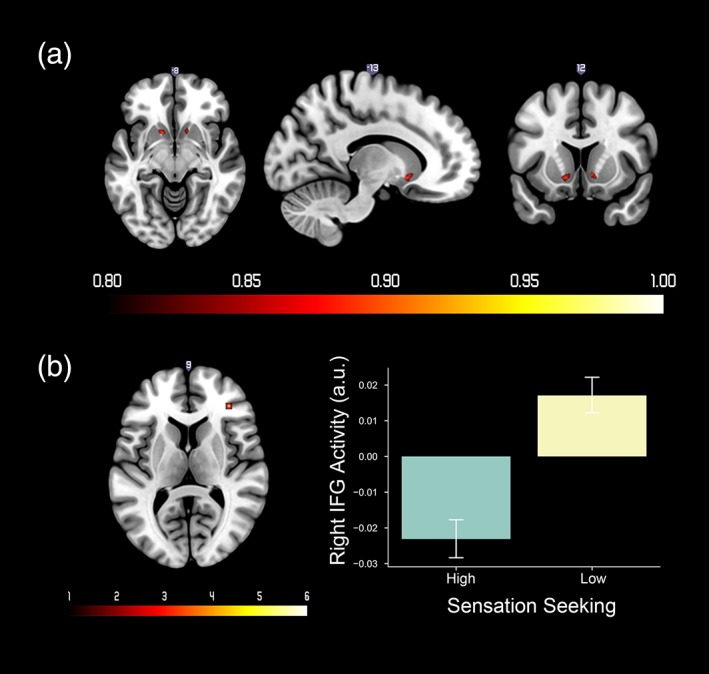

3.5. Computational modeling of reward PE

Table 5 and Figure 7a depict regions with greater than 0.8 probability of positive‐activation associated parametric modulation of reward PE. Sensation Seeking scores were negatively correlated with parametric modulation of the reward PE in right inferior frontal gyrus (right IFG) (t = 4.88, MNI: 36, 38, 10). A comparison between high and low sensation seeking groups showed that adolescents with low sensation seeking scores had stronger right IFG activation associated with reward PE compared with adolescents with higher sensation seeking scores (t = 5.13, MNI: 36, 38, 10) (see Figure 7b). Comparisons for gender and puberty as well as other sensation seeking analyses, for either activation or connectivity, were non‐significant.

Figure 7.

(a) Probabilistic map of positive activation in response to reward prediction error (PE). The color bar denotes the probability of activation. (b) Left: Regions that showed different activity associated with reward PE between low sensation seeking group versus high sensation seeking group. The color bar denotes t values. Right: Mean and standard error of right IFG activity for high and low sensation seeking groups. Right IFG activity from the contrast image was extracted from a 3‐mm spherical ROI at MNI coordinates: 36, 38, 10 [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The bilateral VS activation was correlated with parametric modulation of reward PE, consistent with a wealth of previous findings suggested that reward PE is primarily encoded in VS (Chase, Kumar, Eickhoff, & Dombrovski, 2015; Garrison et al., 2013). Sensation seeking was negatively correlated with right IFG activity following a reward PE (i.e., high sensation seeking adolescents had less right IFG activity for reward PE). Previous studies have reported right IFG involvement in processing of negative PE (Cservenka et al., 2013; Meder, Madsen, Hulme, & Siebner, 2016). For instance, participants with higher right IFG responses to negative PE were less likely to switch options in a probabilistic learning task (Meder et al., 2016). As Cservenka et al. (2013) reported previously, high sensation seeking adolescents had greater deactivation following a no‐win outcome (i.e., a larger negative PE). Here, we extend this finding by showing a correlation in the right IFG to both positive and negative PE effects, which we estimated using a Rescrola–Wagner model. Interestingly, the correlation with sensation seeking was only observed with the computational model rather than the reward omission contrast. The lower right IFG activity observed in high sensation seeking adolescents may indicate that they allocate fewer attentional resources to the discrepancy between anticipated and actual outcome. We did not observe insula activity, unlike Cservenka et al. (2013); however, the cluster in the right IFG extended into anterior insula, albeit below the threshold for multiple comparison correction.

4. GENERAL DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined neural activity associated with different stages of reward processing. We derived a map depicting the probability of a voxel being significant at a family‐wise error rate corrected p‐value under .05 for an aggregation of subsamples of 100 subjects, and we subsequently conducted PPI analyses. Our results showed that regions within the limbic system, salience network, attention network and motor areas showed activation and/or connections with seed regions in reward anticipation, reward receipt, and infrequent reward omission. Within the different reward processing stages, we observed distinct patterns of activity. For example, thalamic connectivity differed by reward processing stage, with positive connectivity to motor‐related areas only observed during reward anticipation. This work, therefore, refines our knowledge of thalamic activity during adolescent reward processing (Haber & Calzavara, 2009; Haber & Knutson, 2010). During the reward receipt stage, our probability analysis revealed markedly specific functional neuroanatomy: vmPFC was reliably activated during reward receipt but VS was reliably activated following a reward PE. These findings are consistent with results from statistical comparison showing a dissociation between reward receipt and PE (Rohe et al., 2012). Studies have suggested that predicted amount of reward associated with outcome of actions (goal values) is specifically encoded in vmPFC (Hare, Camerer, & Rangel, 2009; Hare et al., 2008), whereas reward PE is coded in VS (Hare et al., 2008; Peters & Büchel, 2010), findings that are strongly supported by our adolescent data.

Due to the large sample size, we could conduct gender‐specific analyses. During reward anticipation, males had more activation in bilateral putamen, right middle temporal gyrus and precuneus compared with females. The comparisons for brain activation during reward processing between males and females suggest the basic reward system is broadly similar for both genders, with relatively minor differences for specific structures. A previous adult study suggested that men have stronger activation in left putamen in response to anticipated monetary reward (Spreckelmeyer, et al., 2009). Our results may provide evidence that the gender differences in left putamen activity associated with reward anticipation already exist in adolescence. Previous studies have shown that putamen, middle temporal gyrus, and precuneus were associated with risk‐taking behaviors (Goh et al., 2016; Mitchell, Gao, Hallett, & Voon, 2015). For instance, right putamen activity to a novel stimulus was positively correlated with following risk‐taking choices (Mitchell et al., 2015). Higher‐risk sexual behaviors in adolescents are correlated with increased activation in right precuneus and temporal gyrus during receipt of social reward and increased precuneus functional connectivity with other regions (Eckstrand et al., 2017). Therefore, a more nuanced understanding of the gender differences in brain regions associated with reward processing can contribute to our understanding of gender‐specific vulnerabilities to problem behaviors during adolescence, such as adolescent males’ tendency to engage in more risk‐taking behaviors than females (Morrongiello & Rennie, 1998; Steinberg, 2004).

A growing literature has revealed the important role of pubertal development in adolescent reward processing (Blakemore et al., 2010; Forbes, et al., 2010, 2011; Goddings et al., 2014; Klapwijk et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2012; Urosevic et al., 2014). Previous studies have revealed the positive correlation between sex hormone level and pubertal stage (Shirtcliff, Dahl, & Pollak, 2009), and sex hormone‐levels, such as testosterone, was positively correlated with the striatum activation to a monetary reward for both boys and girls (Op de Macks, et al., 2011). Moreover, Forbes et al. (2010), in adolescents aged 11–13 years‐old (pre‐puberty vs. mid‐/late‐puberty) found that male adolescents with higher testosterone level exhibited more striatal responses during reward anticipation and both adolescent males and females with higher testosterone level showed less striatal activity during reward outcome (Forbes et al., 2010). In contrast with these studies, however, we did not observe any significant difference with voxel‐wise FWE corrected threshold in separate comparisons of early versus late pubertal development for males and females. The lack of puberty effects observed in the study was surprising especially when significant gender effects were observed from the same dataset. The Tanner stage is commonly used for measuring puberty in previous studies (Blakemore et al., 2010; Goddings et al., 2014), while other supplemental measurements such as hormone assays are recommended (Blakemore et al., 2010). The lack of other measurement of pubertal stage, and variability in puberty stage which constrained our analysis in comparing males (Pubertal Stages 2 vs. 4) and females (Pubertal Stages 3 vs. 5) should be borne in mind when interpreting our results. Future studies with a wider age range and other measurements of pubertal stage may help to better understand puberty effects on the reward system. Pubertal effects on reward processing that survived cluster‐wise FWE corrected threshold p < .05 are reported as Supporting Information Results.

There are limitations to this study. First, our claims are limited to functional connectivity between brain regions, without any inference of directionality. Second, shape of the hemodynamic response function was assumed to be the same across brain regions and participants (O'Reilly, Woolrich, Behrens, Smith, & Johansen‐Berg, 2012). Third, we assumed a fixed learning rate in the RW model. Future studies with individualized parameters may better capture the brain activation during reward processing.

5. CONCLUSION