Abstract

Brain development is most rapid during the fetal period and the first years of life. This process can be affected by many in utero factors, such as chemical exposures and maternal health characteristics. The goal of this review is twofold: to review the most recent findings on the effects of these prenatal factors on the developing brain and to qualitatively assess how those factors were generally reported in studies on infants up to 2 years of age. To capture the latest findings in the field, we searched articles from PubMed 2012 onward with search terms referring to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), brain development, and infancy. We identified 19 MRI studies focusing on the effects of prenatal environment and summarized them to highlight the recent advances in the field. We assessed population descriptions in a representative sample of 67 studies and conclude that prenatal factors that have been shown to affect brain metrics are not generally reported comprehensively. Based on our findings, we propose some improvements for population descriptions to account for plausible confounders and in time enable reliable meta‐analyses to be performed. This could help the pediatric neuroimaging field move toward more reliable identification of biomarkers for developmental outcomes and to better decipher the nuances of normal and abnormal brain development.

Keywords: brain, central nervous system, growth and development, infant, magnetic resonance imaging, maternal exposure, neuroimaging

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Early brain development

The brain grows and develops most rapidly during the fetal period and the first years of life. Total brain volume measured 2–4 weeks after birth is approximately 36% of that of an average adult brain. The brain increases in size by 101% during the first year and by another 15% during the second year, reaching over 80% of adult brain volume (Knickmeyer et al., 2008). During this rapid development, multiple interacting mechanisms such as myelination of white matter (WM) and functional specialization of brain areas are happening simultaneously (Dubois, Kulikova, Poupon, & Hu, 2014). This delicate process can be affected by several external factors already present during the in utero period. The prenatal factors that may significantly affect early brain development include two major categories: (1) chemical exposures in utero, and (2) maternal health characteristics.

1.2. Chemical exposures in utero

Prenatal drug exposure is a relatively common problem that causes long‐lasting developmental disturbances. In year 2015, based on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, in the United States, 9.3% of pregnant women used alcohol, 13.9% tobacco products, and 4.7% illicit drugs (SAMHSA, 2016). Illicit drugs are here defined as all drugs of abuse except alcohol, nicotine products, and prescription drugs used for medical purposes, and we will use this definition throughout this article. Alcohol is one of the prenatal chemical exposures known to have long‐lasting effects on brain development, including smaller total brain volume, smaller gray matter (GM) volumes in basal ganglia, frontal, and parietal lobes, as well as size changes in the hippocampus and caudate nucleus (Donald, Eastman, et al., 2015). Nicotine causes hypoxia and disrupts neurotransmission (Slotkin, 1998), leading to lowered birth weight (Janisse, Bailey, Ager, & Sokol, 2014). Furthermore, prenatal maternal smoking is associated with an increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome (Anderson, Johnson, & Batal, 2005). Moreover, illicit drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, and narcotics can hinder fetal development (Janisse et al., 2014), whereas perhaps less attention has been paid to the effects of pharmaceutical drug use during pregnancy. Of note, many neuroimaging studies concerning the effects of prenatal drug exposure have been done in later childhood or adolescence, and as these findings are heavily affected by postnatal factors, they are not reviewed here.

1.3. Maternal health characteristics

Multiple maternal health issues can affect in utero brain development. For example, prenatal maternal depression is a common problem. Untreated prenatal depression is associated with preterm birth, neonatal complications, and behavioral problems in the offspring (Waters, Hay, Simmonds, & van Goozen, 2014; Yonkers et al., 2009). Similarly, children of parents with anxiety disorders have an increased risk of anxiety disorders (Turner, Beidel, & Costello, 1987). However, antidepressants may also lead to alterations in brain structure (Jha et al., 2016) and functional organization (Salzwedel, Grewen, Goldman, & Gao, 2016), although the long‐term consequences of these changes are still unknown. Separating the effects of pharmaceutical use from socioeconomic factors and psychiatric symptoms is a major challenge in these exposure studies.

Besides maternal mental health status, maternal obesity is also recognized as a potential cause for offspring adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. For example, a recent study on 5‐ to 7‐year‐olds found a negative association between maternal body mass index (BMI) and offspring's cognitive performance (Basatemur et al., 2013). In addition to maternal obesity, other proinflammatory states (Graham et al., 2018) and even noninflammatory states (Tingi, Syed, Kyriacou, Mastorakos, & Kyriacou, 2016) as well as many still unknown factors may affect fetal neurodevelopment.

1.4. Purpose of this review

In this structured review, we cover a wide variety of studies from recent years, with a primary focus on prenatal factors that may affect early brain development. In addition, we examine a representative set of studies on up to 2 years old healthy term born infants to assess how well these prenatal influences have been considered as confounding factors in studies where they were not the main focus. This review will highlight the importance of the fetal period on early brain development, complementing a recent review on gene–environment interactions in similar studies (Gao et al., 2018).

2. LITERATURE SEARCH

We focused on studies that used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques to assess brain development in healthy term born infants up to 2 years of age. To identify relevant articles, we conducted a PubMed search using the following terms: (“Magnetic Resonance Imaging” [Mesh] OR MR imaging* OR MRI OR fMRI OR DTI OR “diffusion tensor imaging”) AND (“Brain/growth and development” [Mesh] OR brain growth* OR brain developm*) AND (“Infant” [Mesh] OR infant* OR toddler* OR neonat* OR newborn*). To keep the search comprehensive, no search term referred to the prenatal time, in utero environment, or maternal characteristics. This was important as we were also interested in how these factors were reported in other MRI studies on healthy term born infants. The only filter used was the time of publication which ranged from January 1, 2012 to March 31, 2018, the search being performed on April 1, 2018. We chose to review the most recent findings in hope to capture a methodologically comparable set of studies.

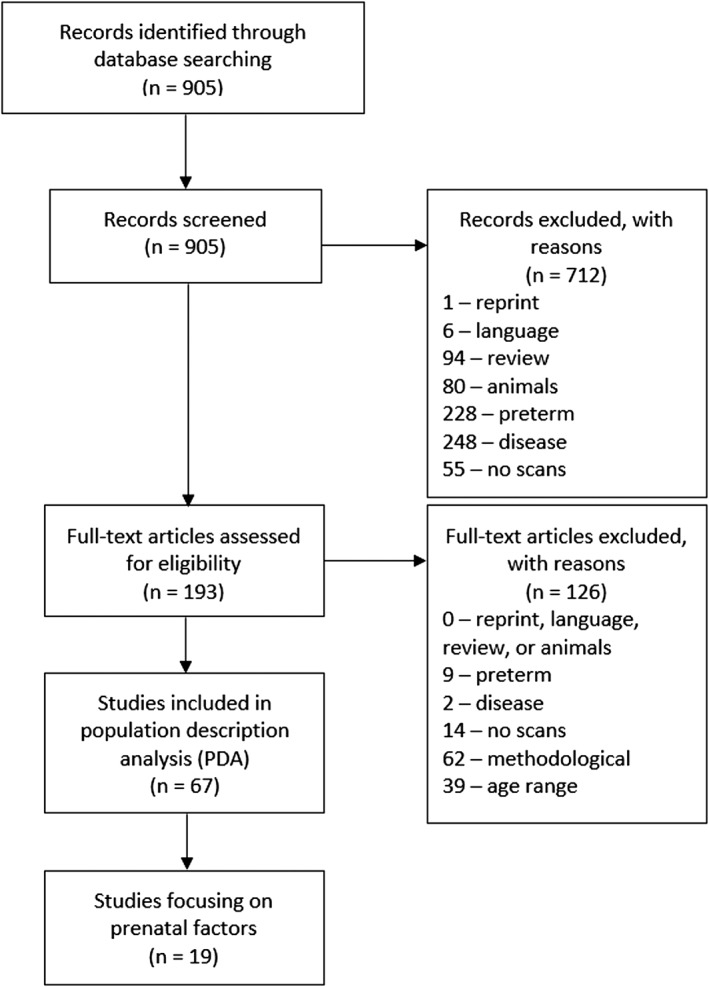

Our search resulted in 905 articles. In the screening phase, our major goal was to exclude all studies outside the set age range and/or involving “abnormally” developing participants, that is, with congenital disease or malformation, prematurely born (preterm), or low birth weight (LBW) infants. We considered the latter two categories abnormal as both conditions are linked with increased risk of adverse developmental outcomes and their developmental trajectories are likely different from those of term‐born infants (Inder, Warfield, Wang, Hüppi, & Volpe, 2005; Linsell, Malouf, Morris, Kurinczuk, & Marlow, 2015). We went through titles and abstracts for initial screening. Subsequently, we identified 193 potentially relevant articles. The other 712 were excluded as presented in Figure 1. During screening, if a publication met more than one of our exclusion criteria it was excluded based on the highest priority criterion they met. In case an exclusion criterion was clear from the title, we did not search the abstract for a higher priority criterion. Exclusion criteria are presented in detail in the Supporting Information Material. Exclusion criteria at this phase in descending order of priority were:

Publication was a duplicate of another publication found in this search.

Publication was not written in English.

Publication was a review article.

Subjects were nonhuman animals. Studies were also excluded if both humans and other animals were studied.

The study focused on preterm (born before 37 weeks gestational age [GA]) or LBW (birth weight <2,500 g) subjects of any age.

The study focused on the effects of a certain disease or treatment.

Living 0‐ to 2‐year‐olds were not MRI scanned in the study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram outlining the study selection process

About 193 articles passed the screening process. To identify the appropriate studies, we did assessment for eligibility using full articles. In addition to excluding the studies where participants were not healthy term born infants up to 2 years of age, we also excluded studies where the examination of brain development between 0 and 2 years of age was peripheral due to the main focus being on a new method or on a population with a wider age range. This was done to maintain focus on the effects of prenatal factors on early brain development. The assessment for eligibility consisted of three steps (these steps are presented in more detail in Supporting Information Material):

We implemented all the same criteria we did in the screening phase.

We excluded methodological articles regarding either creation, comparison, or optimization of scanning sequences, analysis pipelines, statistics, atlases, or practicalities of the pediatric MRI imaging procedure.

We excluded articles where the age of the participants extended beyond the 2‐year timepoint or conversely to the fetal period.

We identified 19 studies that focused on infants with a certain in utero chemical exposure or infants of mothers with certain characteristics. We summarized these 19 articles to show how the prenatal factors they examined may affect early neurodevelopment and to therefore provide basis for why these factors should be reported in all pediatric neuroimaging studies.

On a complementary approach, we performed a population description analysis (PDA) among the articles identified during the literature search. In addition to the aforementioned 19 articles, we found 48 articles that focused on other aspects of early brain development. Altogether 67 articles were used in the PDA, where we examined how the reviewed prenatal factors were generally reported in MRI studies on infants up to 2 years of age. In the PDA, we went through both the articles and their supplementary materials to gather the information on participant characteristics.

We aimed at covering a wide variety of studies both qualitatively and thematically to get a sample that represents the infant/pediatric neuroimaging field. To minimize selection bias, we selected studies using predefined search terms and exclusion criteria. Therefore, we decided to conduct a structured review. We concluded that this approach was sufficient to describe the current trends in population descriptions. Of note, we considered performing systematic review, but soon discovered that it is not feasible due to small amount of studies on a single prenatal exposure. While some articles relevant to prenatal effects of the environment might have been left out of the sample, findings from studies outside our search are discussed where appropriate. For the purposes of the PDA, we believe this is a representative sample of the research done during the chosen period and can be used to accurately describe current trends in the infant neuroimaging field.

3. EFFECTS OF PRENATAL EXPOSURES ON THE INFANT BRAIN

3.1. Overview of the studies on prenatal exposures

We identified 19 articles addressing the effects of prenatal environment on infant brain structure and function (summarized in Table 1, presented in more detail in Supporting Information Material). These studies were expectedly most often done during the first few weeks of life (the baseline scans were performed within the first six weeks of life in all 19 studies) to best isolate the effects of prenatal environment. Many chemical and maternal factors were found to affect brain structure at this early age, while the number of studies per topic is still quite small. In the following, we synthesize the results from the reviewed studies and discuss viable future directions.

Table 1.

Summaries of recent studies on the effects of prenatal environment on the infant brain

| Study | Study design | N | Age at scan: mean (SD) | Teslas | Modality | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | ||||||

| (Donald et al., 2016) | Cross‐sectional | 73. 28 alcohol, 45 CTL | Alcohol 20.54 (5.98), CTL 22.24 (6.11) days | 3.0 | T2 | Total GM volumes were lower in infants with in utero alcohol exposure compared with the control group. The greatest changes were observed in the left and right amygdalae, left hippocampus, and left thalamus. |

| Tobacco and drugs of abuse | ||||||

| (Chang et al., 2016) | Longitudinal | 139. 36 M/To, 32 To, 71 CTL | 1 week, 1–2 months, and 2–4 months. At baseline, post‐menstrual ages M/To 43.44 (.77), To 41.38 (.56), CTL 40.56 (.19) weeks | 3.0 | DTI | Prenatal tobacco and methamphetamine exposures were associated with gender‐ and region‐dependent alterations in WM FA values and diffusivities. Delayed motor development was seen in those with methamphetamine and tobacco exposures. Many observed changes normalized by 3–4 months of age. |

| (Salzwedel et al., 2016) | Cross‐sectional | 152. PCE 45, NCOC 43, CTL 64 | 2–6 weeks. GA at scan PCE 308 (2.92), NCOC 305 (1.53), CTL 306 (1.41) days | 3.0 | rs‐fMRI | The study revealed that cocaine exposure was associated with increased connectivity between anterior thalamus and frontal cortex. PCE and NCOC neonates had lower connectivity between the thalamus and motor‐related regions compared with CTL group. |

| (Grewen et al., 2014) | Cross‐sectional | 119. 33 PCE, 40 NCOC, 46 CTL | 1 month after birth. GA at scan: PCE 307.5 (2.9), NCOC 304.8 (2.7), CTL 303.1 (2.5) | 3.0 | T1, T2 | PCE group had smaller GM volumes in frontal and prefrontal regions and larger CSF volumes in frontal, prefrontal, and parietal regions compared with the other groups. No volumetric differences between NCOC and CTL groups were observed. |

| Pharmaceuticals | ||||||

| (Monnelly et al., 2018) | Cross‐sectional | 40. 20 methadone, 20 CTL | Median (range): methadone 3 (1–21), CTL 13 (5–29) days | 3.0 | dMRI | Median FA was 12% lower in the methadone‐exposed group than in the control group throughout the WM. |

| (Spann et al., 2015) | Cross‐sectional | 37. 24 anesthetics, 13 CTL | Anesthetics 22.4 (10.5), CTL 16.1 (11.2) days | 3.0 | T2 | Local volumes in frontal and occipital lobes and in the right posterior cingulate gyrus were higher in infants exposed to anesthetic drugs than in controls. Volumes in frontal and occipital lobes correlated inversely with the results of fine motor and expressive communication scores. |

| Depression and SSRIs | ||||||

| (Wang et al., 2018) | Cross‐sectional | 161 | 5–14 days. GA at MRI: 40.3 (1.1) weeks | 1.5 | T2 | Infant right hippocampal volume correlated positively with prenatal maternal depressive symptoms in low genetic risk individuals and negatively in high genetic risk individuals. |

| (Qiu et al., 2017) | Cross‐sectional | 189 Asian cohort, 85 US cohort | GA at MRI: Asian 40.08 (1.21), US 43.02 (2.10) weeks | Asian 1.5, US 3.0 | Asian T2, US T1, T2 | Right amygdala and right hippocampal volumes correlated positively with maternal depressive symptoms in infants with high genetic risk and negatively in infants with low genetic risk for major depressive disorder in the Asian cohort, while the direction of this interaction effect on the right amygdala volume was the opposite in their US cohort. |

| (Jha et al., 2016) | Cross‐sectional | 204. Cohort1: SSRI 27, CTL 54. Cohort2: Dep 41, CTL 82 | Cohort1: SSRI 27.07 (13.56), CTL 24.83 (12.90). Cohort2: Dep 27.98 (14.49), CTL 27.1 (12.94) days | 3.0 | DTI | SSRI exposed group had lower FA and higher diffusivity values than their controls. Infants with maternal history of depression but no prenatal SSRI exposure did not differ from their controls. |

| Anxiety and stress | ||||||

| (Qiu et al., 2013) | Longitudinal | 175 at baseline, 35 at 6 months | 5–17 days and 6 months. Post conceptual ages 40.1 (1.2) and 66.2 (1.9) weeks | 1.5 | T2 | Prenatal maternal anxiety was discovered to negatively affect the growth rates of bilateral hippocampi during the first 6 months of infant's life. Only right side remained significant after controlling for postnatal maternal anxiety. |

| (Qiu et al., 2014) | Cross‐sectional | 146 | Range 5–17 days | 1.5 | T2 | Prenatal maternal anxiety did not affect the neonatal CT. However, certain SNPs in the COMT gene moderated associations between maternal anxiety and neonatal CT. |

| (Moog et al., 2018) | Cross‐sectional | 80. 28 CM+, 52 CM‐ | CM 28.29 (14.6), CTL 24.77 (12.3) days | 3.0 | T1, T2 | CM+ group had significantly lower intracranial volumes (ICV) and GM volumes compared with CM‐ group. Infant sex did not moderate these effects of maternal CM. Regional analyses of GM suggested global, rather than region specific effects by maternal CM. |

| Maternal obesity and other proinflammatory states | ||||||

| (Ou et al. 2015) | Cross‐sectional | 28. 11 obese, 17 NW mothers | Obese 2.2 (0.5), NW 2.1 (0.2) weeks | 1.5 | DTI | Infants of normal‐weight mothers had higher FA values than those from obese mothers in multiple WM regions including association, projection, callosal, and limbic tracts. |

| (Li et al., 2016) | Cross‐sectional | 34. 16 obese, 18 NW mothers | Obese 14.3 (1.7), NW 14.2 (1.8) days | 3.0 | rs‐fMRI | Left and right dorsal anterior cingulate had significant group differences, with infants born to obese mothers having lower functional connectivity to prefrontal lobe network than those born to normal weight mothers. |

| (Graham et al., 2018) | Cross‐sectional | 86 | 3.79 (1.84) weeks | 3.0 | T1, T2, rs‐fMRI | Higher maternal IL‐6 level was significantly associated with larger right amygdala volume. Larger neonatal right amygdala volume was associated with poorer impulse control at 2 years of age. Higher IL‐6 concentrations were associated with stronger connectivity from bilateral amygdalae to multiple brain regions. |

| Other maternal and family characteristics | ||||||

| (Knickmeyer et al., 2016) | Cross‐sectional | 756 | 33 (20) days | 3.0 | T1, T2 | Gestational ages at MRI and at birth, gender, and birth weight were the most important predictors of differences in brain volumes. |

| (Jha et al., 2018) | Cross‐sectional | 805 | 30.64 (16.871) days | 3.0 | T2 | Postnatal age at MRI, paternal education, and maternal ethnicity were significantly associated with average CT. Average CT correlated positively with postnatal age at MRI and negatively with paternal years of education. For total surface area, postnatal age at scan, age at birth, birth weight, and sex were the most important predictors. |

| (Betancourt et al., 2016) | Cross‐sectional | 44. 25 low SES, 19 high SES | Low SES 5.0 (0.9), high SES 5.0 (1.2) weeks | 3.0 | T1, T2 | SES correlated positively with cortical and deep GM volumes. SES had no effect on WM volumes. |

| (Monk et al., 2016) | Cross‐sectional | 40 | 19.63 (8.31) days | 3.0 | DTI | Self‐reported iron intake during pregnancy was inversely correlated with neonatal FA values. Differences were most pronounced in cortical GM, but they were also present in some major axonal pathways. |

Age at scan is presented as postnatal age: mean (standard deviation), unless otherwise stated. SD = standard deviation; CTL = control group; M/To = prenatal exposure to methamphetamine and tobacco; To = prenatal exposure to tobacco; PCE = prenatal cocaine exposure; NCOC = exposure to similar drugs as PCE group but without cocaine; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; Dep = history of maternal depression but no prenatal exposure to antidepressants; CM+ = maternal exposure to childhood maltreatment; CM− = no maternal exposure to childhood maltreatment; NW = normal‐weight; SES = socio‐economic status; DTI = diffusion tensor imaging; rs‐fMRI = resting‐state functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); dMRI = diffusion MRI; CT = cortical thickness; GM = gray matter; WM = white matter; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; FA = fractional anisotropy; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; COMT = catechol‐O‐methyltransferase; IL‐6 = interleukin 6. Study design is labeled as cross‐sectional or longitudinal based on the number of scan timepoints, not other (e.g., behavioral) measurement timepoints.

3.2. Alcohol as a prenatal exposure

Prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) has previously received little attention in brain imaging of children under 5 years of age (Donald, Eastman, et al., 2015); however; in the last few years some studies have addressed this topic. A 2016 study by Donald et al. (2016) found that PAE was associated with reduced overall GM volumes, most notably in bilateral amygdalae, left hippocampus, and left thalamus at 3 weeks of age and with slightly delayed socio‐emotional development compared with control infants at 6 months of age. The findings of lower total GM volume are consistent with results on older children, which suggests that they are pervasive (Archibald et al., 2001; Nardelli, Lebel, Rasmussen, Andrew, & Beaulieu, 2011). Structurally, PAE has also been linked to decreased corpus callosum area (Jacobson et al., 2017). Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies on the topic have found lowered axial diffusivity (AD) values in PAE infants (Donald, Roos, et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2015). Additionally, a recent neonatal functional MRI (fMRI) study (Donald, Ipser, et al., 2016) found increased connectivity in somatosensory, motor, brainstem, thalamic, and striatal intrinsic networks at 2–4 weeks of age. Findings in both structural and functional imaging studies strengthen the notion that PAE affects the developing brain. However, discovering the practical meaning of these findings requires follow‐up studies and measurements of neurobehavioral correlates.

3.3. Tobacco and drugs of abuse as prenatal exposures

One study by Knickmeyer et al. (2016) found marginal associations between maternal smoking and reduced GM, WM, and intracranial volumes (ICV). Changes in GM volumes were mediated by birth weight, which is not surprising considering that the effects of smoking primarily owe to growth restriction from hypoxemia (Lambers & Clark, 1996; Slotkin, 1998). However, WM and intracranial volumes were not mediated by birth weight, suggesting another mechanism not related to overall growth restriction.

Studies with repeated scans are especially informative, partly because some of the observed structural changes may disappear, even if the functional effects of the exposure remain. One such study by Chang et al. (2016) examined the effects of prenatal methamphetamine and tobacco exposures, performing repeated scans during the first 6 months of life. Sex‐dependent variations in fractional anisotropy (FA) and diffusivity values were seen widely in the corona radiata. In addition, the infants with exposure to both methamphetamine and tobacco showed delayed sensorimotor development during first the weeks of life. Most of the changes reversed by 3 to 4 months of age, which is intriguing considering that prenatal cigarette smoking exposure has been reported to lead to undesirable outcomes in later life (Müller et al., 2013; Weissman, Warner, Wickramaratne, & Kandel, 1999). This finding stresses the importance of longitudinal studies linking early structural changes to possible future outcomes.

Apart from nicotine and alcohol, other drugs of abuse seem to have detrimental effects on the developing brain—often reported as decreased brain volumes or altered functional maturation (Grant, Petroff, Isoherranen, Stella, & Burbacher, 2017; Sirnes et al., 2017, 2018). Furthermore, most prenatal drug exposures are associated with reduced birth height and weight (Janisse et al., 2014). Drug use is rarely limited to one substance. This methodological challenge is partly overcome by including a control group with similar drug exposure to the main group but without the drug of interest (Grewen et al., 2014; Salzwedel et al., 2016). Moreover, treatments for drug dependency disorders likely have neurodevelopmental outcomes that are still poorly understood, and finding optimal treatments also with regard to fetal development is of crucial importance (Minozzi, Amato, Bellisario, Ferri, & Davoli, 2013; Monnelly et al., 2018). Furthermore, pharmacotherapy during delivery and pregnancy may cause adverse effects to the fetus (Monnelly et al., 2018; Spann et al., 2015) and should be examined more thoroughly in the future.

3.4. Depression and pharmacotherapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) as prenatal exposures

Depression is a common and strongly familial disorder (Weissman et al., 2016). Two recent studies by Wang et al. (2018) and by Qiu et al. (2017) examined the effects of different genetic variants on amygdalar and hippocampal morphology. Wang et al. discovered that infant right hippocampal volumes correlated positively with prenatal maternal depressive symptoms in low genetic risk individuals and negatively in high genetic risk individuals in an Asian cohort. High and low genetic risk were defined by FKBP5 genotype (FKBP5 gene regulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function). On the other hand, Qiu et al. discovered that right amygdalar and right hippocampal volumes correlated positively with maternal depressive symptoms in infants with high genetic risk and negatively in infants with low genetic risk for major depressive disorder (calculated from multiple risk genes) in their Asian cohort, while the direction of this interaction effect on the right amygdala volume was the opposite in their US cohort. These studies bring up two very interesting points. Firstly, the direction of the interaction effect between prenatal maternal depressive symptoms and high genetic risk for psychopathology was different between the Asian cohorts in the two studies, and different between Asian and US cohorts within the study by Qiu et al. In the former, the difference could owe to the focus being in variation in a single gene (Wang et al., 2018), while the other one calculated genetic risk from multiple known risk loci (Qiu et al., 2017). In any case, this discrepancy suggests that hippocampal or amygdala volumes alone should not be used to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes without knowledge of the genetic variants. Moreover, same single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in certain genes may have opposing effects for risk of psychopathology in groups of different backgrounds (Domschke, Deckert, O'Donovan, & Glatt, 2007), which was supported by the difference seen between Asian and US cohorts (Qiu et al., 2017). Secondly, all effects in these two studies were on the right side of the brain, strongly suggesting a lateralization pattern. Structural and functional lateralization of these subcortical areas is also seen in older subjects (Baas, Aleman, & Kahn, 2004; Carrion, Weems, & Reiss, 2007). However, the lateralization patterns are poorly understood, and follow‐up studies with behavioral measurements are crucial to further understand their practical implications.

SSRI medication is sometimes prescribed to pregnant mothers suffering from depression. A study by Jha et al. (2016) compared brain volumes and DTI parameters of infants with prenatal SSRI exposure to their matched controls, and infants of mothers with a history of depression but no current pharmacotherapy to their matched controls attempting to separate the effects of the SSRI exposure from the effects of maternal qualities. Widespread differences were seen in DTI values between SSRI‐exposed infants and controls, while no differences were seen between those with maternal history of depression and their controls. Effects were particularly pronounced in mean diffusivity (MD) and radial diffusivity (RD) values in corticofugal and corticothalamic tracts. Another study be Salzwedel et al. (2016) found marginally significant, constant drug–drug interactions between SSRIs and cocaine on thalamocortical connectivity measures. On the cognitive side, prenatal SSRI exposure has been found to delay language development (Rotem‐Kohavi & Oberlander, 2017). Untreated prenatal depression is associated with preterm birth, neonatal complications, and behavioral problems in the offspring (Rotem‐Kohavi & Oberlander, 2017; Waters et al., 2014; Yonkers et al., 2009). However, distinguishing the exact role of SSRIs from other factors, such as genetic risk and maternal depression as such, remains a challenge for future studies. One of the reasons for this difficulty is the notion that mothers who require SSRIs during pregnancy likely have more severe depression than those who do not.

3.5. Maternal mental health as a prenatal exposure: Anxiety and stress

The terms early life stress (ELS) and prenatal stress (PS) can have multiple meanings. Since there is no test or questionnaire for stress per se, each study defines its own markers for ELS and/or PS. Some studies use psychiatric questionnaires such as Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and Symptom Checklist‐90, the anxiety subscale (Karlsson et al., 2018) while others may also include somatic or biological measures such as nutrition and drug intake (Bock, Wainstock, Braun, & Segal, 2015). Here we will discuss primarily anxiety‐related measures.

A study by Qiu et al. (2013) found that prenatal maternal anxiety did not affect hippocampal volumes at birth but was associated with slower growth of bilateral hippocampi during the first 6 months of life. Interestingly, postnatal anxiety correlated positively with right hippocampal growth between birth and 6 months of age after controlling for prenatal anxiety, and negatively with left hippocampal volume at 6 months of age (Qiu et al., 2013). Similarly, previous studies have found probable developmental differences between the left and the right hippocampi, and these differences may well have functional implications (Bremner et al., 1997; Koolschijn, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans‐Kranenburg, & Crone, 2013; Rusch, Abercrombie, Oakes, Schaefer, & Davidson, 2001). Right–left differences and the timing of adversity ought to be examined more rigorously, especially concerning the intriguing interplay between prenatal programming and postnatal adaptation.

Findings by Qiu et al. (2014) show that prenatal anxiety differentially associated with cortical thickness (CT) based on catechol‐O‐methyltransferase (COMT) gene haplotype. In the brain, the product of COMT gene breaks down certain neurotransmitters such as catecholamines and is particularly important in the prefrontal cortex. An interaction effect between maternal anxiety and val158met SNP in the COMT gene was observed in the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. In this area, higher prenatal maternal anxiety was associated with thicker cortex in higher activity genotypes (val homozygotes) that cause decreased dopamine signaling, and with thinner cortex in lower activity genotypes (met homozygotes). COMT is a gene linked with both psychiatric outcomes in later life and structural findings in early life and is therefore an example of how neuroimaging might provide useful biomarkers to more accurately identify those at risk. On the other hand, this finding also underlines the need to link genetic variants with imaging data prior to addressing the prenatal exposures.

Early life adversity, such as abuse or neglect, can lead to greater sensitivity to stress and increased risk for mental health problems in later life (Banyard, Williams, & Siegel, 2001; Heim, Shugart, Craighead, & Nemeroff, 2010). Furthermore, a lot of research has focused on the intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment (CM) (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011; Ertem, Leventhal, & Dobbs, 2000), although pediatric neuroimaging studies on the topic are scarce. A recent study by Moog et al. (2018) examined the effects of maternal exposure to CM on total brain and GM volumes of their offspring at approximately one month of age. Infants with mothers exposed to CM had smaller intracranial and global GM volumes, suggesting that maternal exposure to CM has a direct intergenerational effect on infant neurodevelopment.

3.6. Maternal obesity and malnutrition as prenatal exposures

Maternal obesity has become recognized as a factor affecting early brain development. A study by Ou et al. (2015) examined how maternal adiposity affects WM maturation in 2‐week‐old infants. Maternal fat percentage correlated negatively with FA values in anterior parts of the brain, suggesting poorer maturation in infants of obese mothers. Another study by Li et al. (2016) found that maternal obesity was associated with decreased functional connectivity in the prefrontal network, more specifically in the left and right dorsal anterior cingulate, although only the left side remained significant after controlling for covariates.

In the study by Ou et al. (2015), the infants of normal‐weight and obese mothers did not differ from each other in birth weight or other measures, suggesting that maternal adiposity can directly cause changes in the fetal brain. Distinguishing pre‐ and postnatal effects of maternal adiposity is of critical importance, as the social environment in postnatal life can also alter the development of the child. On a molecular level, epigenetic changes could cause the observed changes. The study by Ou et al. also found that many genes related to central nervous system development were differently methylated in umbilical cord samples depending on maternal adiposity profile. However, epigenetic mechanisms are outside the scope of this review.

Contrasting obese mothers, children of underweight mothers have an increased risk to be small for GA (Black et al., 2013). Some studies have found associations between LBW and poorer psychomotor development (Tofail et al., 2012). Undernutrition can also accentuate the effects of other maternal diseases such as anemia (Patel et al., 2018). Specific maternal nutritional deficits, such as vitamin D and vitamin B12 deficiencies, can also affect infant neurodevelopment (Hanieh et al., 2014; Lövblad et al., 1997). The mechanisms behind the neurodevelopmental effects of these multiple nutritional deficiencies are outside the scope of this review.

3.7. Proinflammatory states as prenatal exposures

Proinflammatory environment can result from multiple causes including the aforementioned obesity (Choi, Joseph, & Pilote, 2013) and malnutrition (Marques, Bjørke‐Monsen, Teixeira, & Silverman, 2015). Other potential causes are PS (Marques et al., 2015) and maternal infections, such as the human immunodeficiency virus infection that can affect infant neurodevelopmental outcomes, even when the infant is uninfected (Tran et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2018). Meanwhile, some pathogens primarily cause pathological outcomes through fetal infection, for example, Zika virus (Melo et al., 2016). Infected infants are outside the scope of this review, and for the sake of conciseness maternal infections are not covered in more detail.

Maternal inflammation has been linked with increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders (Estes & McAllister, 2016; Li et al., 2016), however debate exists on what biological mechanisms are included in this process (Van der Burg et al., 2016). One potentially important molecule is interleukin 6 (IL‐6), a proinflammatory cytokine (Van der Burg et al., 2016). A study by Graham et al. (2018) examined the effects of maternal systemic IL‐6 levels on the neonatal amygdalar volumes and functional connectivity as well as impulse control at 2 years of age. Larger neonatal right amygdalar volume mediated the association between higher maternal IL‐6 levels during pregnancy and poorer impulse control in the offspring at 2 years of age. This finding was compatible with previous findings (Tottenham et al., 2010; Vassilopoulou et al., 2013). For future studies, we propose comprehensive examination of the different molecular components in inflammation, in both mothers and infants, to identify mechanisms linking maternal inflammation to fetal neurodevelopment.

3.8. Other maternal health and family characteristics

Multiple maternal characteristics have potential to affect infant brain development. Two large studies by Knickmeyer et al. (2016) and Jha et al. (2018) (n = 756 and n = 805, respectively) examined the effects of prenatal environment and family characteristics on infant brain morphology at approximately 1 month of age. Knickmeyer et al. found that GA at scan, GA at birth, birth weight, and sex were the most important predictors of all brain volumes (GM, WM, CSF, and ICV). Jha et al. found these same four factors to be the most important predictors of total surface area (SA), with the difference that they used postnatal age at scan instead of GA at scan. For total CT, the most powerful predictors were postnatal age at MRI, paternal education, and maternal ethnicity. The most intriguing findings among these results are the opposing effects of age at birth and age at scan on different GM measures. Age at scan, whether gestational or postnatal, associated positively with GM volume, CT, and SA (Jha et al., 2018; Knickmeyer et al., 2016). GA at birth associated positively with SA (Jha et al., 2018) but negatively with regional CT (Jha et al., 2018) and GM volume (Knickmeyer et al., 2016).

In the study by Jha et al. (2018), paternal education was strongly negatively associated with infant CT. This finding is in line with the finding that children with higher intellectual capacity reach their peak CT later (Shaw et al., 2006). On the other hand, another study by Betancourt et al. (2016) examined the effects of socioeconomic status (SES) on brain volumes in female African‐American infants born at term and appropriate weight for GA and found positive correlations between SES and cortical and deep GM volumes. Jha et al. (2018) also found effects between maternal/paternal ethnicity and infant CT and SA, so differences between ethnic groups may explain part of the opposite effects of SES on infant GM morphology. In any case, more studies are required to delineate the effects of parental SES on early brain development.

Finally, maternal iron status could affect the developing brain, as iron is crucial for myelination (Connor & Menzies, 1996). Monk et al. (2016) examined the effect of maternal iron status on neonatal FA values in a sample where most mothers had normal hemoglobin values. Self‐reported maternal iron intake correlated inversely with infant FA values in GM and in some WM tracts. Cord ferritin level, a proxy for fetal iron supply in utero, was also measured in a subsample of 16 mother–infant dyads, and results were similar to those seen in the full sample. Low cord ferritin levels have previously been linked to poorer mental and psychomotor performance in children 5 years of age (Tamura et al., 2002). Inverse correlation between maternal iron intake and FA in WM tracts found by Monk et al. (2016) is quite surprising. Iron is required for the synthesis of cholesterol and lipids in oligodendrocytes (Connor & Menzies, 1996), meaning that increased iron intake should presumably accentuate WM maturation but the results by Monk et al. suggest the opposite. However, as developmental trajectories are so poorly understood, at the moment we cannot fully assess the compatibility of these seemingly opposite findings. In addition, there are multiple prenatal environmental exposures that can lead to adverse outcomes, for example, lead exposure (Horton, Margolis, Tang, & Wright, 2014), and most likely some harmful substances are yet to be discovered.

3.9. Key challenges

Interpreting the neuroimaging findings is difficult. In an ideal setting, exposures would be quantified from repeated psychological or laboratory measurements, augmented by in depth analysis of the placenta (Green et al., 2015; Vasung et al., 2018), as well as both maternal and infant genetic information. Many of the reviewed studies were cross‐sectional, which is not optimal considering developmental trajectories during the first years of life are still poorly understood. In the light of reviewed studies, one cannot simply assume that higher FA in WM always indicates “better” development from a single cross‐sectional sample (Eikenes et al., 2012; Padilla et al., 2014), as, for example, higher cognitive function may be associated with higher or lower CT depending on age (Shaw et al., 2006). Similarly, thicker cortex or larger brain volume is not always better (Sowell et al., 2004). Thus, longitudinal studies are required to better understand normal and abnormal developmental trajectories.

4. POPULATION DESCRIPTION ANALYSIS

4.1. Overview

We examined how prenatal factors were reported in a set of 67 studies on healthy, term infants between 0 and 2 years of age. Studies that only peripherally concern the topic were excluded, as the reporting in them differs significantly from studies on brain development; for example, participant sex was reported in only 29/62 (47%) and age at birth as mean and standard deviation (SD) and/or as range in only 13/62 (21%) of the methodological articles found in our search. Table 2 presents the results of our search. In summary, we found that while reporting of the most critical infant characteristics is close to a satisfactory level, there are some clear weaknesses in reporting of maternal characteristics that, in the light of the reviewed studies, can significantly affect early brain development.

Table 2.

Reporting of maternal and infantile characteristics in the studies included in population description analysis

| Characteristic | N | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Infant sex | 63 | Reported |

| 4 | Not reported | |

| Age at scan | 15 | Gestational, postmenstrual, or corrected |

| 34 | Days after birth/chronological or not specified (interpreted as days after birth) | |

| 9 | Both above | |

| 9 | Vague | |

| Age at birth | 12 | Mean and SD |

| 19 | Exact range or at least one border stated | |

| 31 | Both above | |

| 5 | Vague or not stated | |

| Birth weight | 18 | Mean and SD |

| 16 | Limited (either range, lower border, or weight “appropriate for GA”) | |

| 19 | Both above | |

| 14 | Not reported | |

| Prenatal alcohol | 7 | Amount of alcohol users/use reported in some way |

| 9 | Used as a reason for exclusion | |

| 5 | Implied as a reason for exclusion | |

| 46 | Not reported | |

| Prenatal smoking | 11 | Amount of smokers/smoking reported in some way |

| 5 | Used as a reason for exclusion | |

| 6 | Implied as a reason for exclusion | |

| 45 | Not reported | |

| Illicit drugs | 5 | Amount of users/use reported in some way |

| 16 | Used as a reason for exclusion | |

| 4 | Implied as a reason for exclusion | |

| 42 | Not reported | |

| Medications | 4 | Used maternal medications reported in some way |

| 12 | Some maternal medications used as reasons for exclusion | |

| 2 | Both above | |

| 49 | Not reported | |

| Maternal disease | 5 | Psychiatric and/or neurological conditions generally reasons for exclusion |

| 9 | Medical conditions generally reasons for exclusion | |

| 10 | Both above | |

| 23 | Certain maternal diseases reported as number of patients or excluded | |

| 20 | Not reported | |

| SES | 37 | Reported in some form |

| 30 | Not reported | |

| SES measures | 11 | Maternal years of education |

| 16 | Maternal education level or highest degree | |

| 4 | Paternal years of education | |

| 1 | Paternal education level or highest degree | |

| 19 | Household income | |

| 2 | Maternal income | |

| 7 | Hollingshead's Index of Social Status | |

| 4 | Maternal IQ | |

| 3 | Class | |

| 2 | Marital status | |

| 1 | Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation | |

| 1 | Home literacy questionnaire | |

| Race/ethnicity | 5 | Both race and ethnicity |

| 30 | Race or ethnicity | |

| 32 | Neither | |

| Maternal age | 16 | Mean and SD |

| 7 | Limited | |

| 2 | Both above | |

| 37 | Not reported | |

| Maternal weight | 4 | BMI or weight, and other measure (fat%, weight gain during pregnancy) |

| 4 | Only BMI or weight | |

| 1 | Only “other measure” | |

| 48 | Not reported |

Table 2, results of the population description analysis (PDA). N = number of studies; SD = standard deviation; GA = gestational age; SES = socioeconomic status; IQ = intelligence quotient; BMI = body mass index. The category “SES measures” allows one article to fit multiple descriptions, as it describes all the metrics used to assess SES or a characteristic approximating it. All other characteristics were categorized such that every article only fits one description. The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation is an official government index used to identify areas of deprivation.

4.2. Infant characteristics

We included infant sex, age at scan, age at birth, and birth weight in the analysis. One intriguing juxtaposition that rose from the findings was the reporting of age at scan as either (1) from conception (15/67 articles, 22%), or (2) from birth (34/67 articles, 51%). Brain likely develops differently before and after birth (Habas et al., 2012; Kapellou et al., 2006). Therefore, the best option is to report both age from birth and from conception (9/67 articles, 13%), as it can help delineate effects of the age at birth. Overall, these basic characteristics were reported well in most studies, although we suggest they all should be reported in all future studies on the topic (Knickmeyer et al., 2016).

4.3. Chemical exposures

PAE was reported in 7/67 (10%) studies, for example as the number of participants exposed, as average amount of alcohol per week, or during which trimester exposure happened. Prenatal smoking exposure was reported in 11/67 (16%) studies, for example as either number of exposed participants or average number of cigarettes per day. Concerning illicit drug use, the 5/67 (7%) articles that reported the amount of drug use were mostly studies concerning either cocaine, methamphetamine, or prescribed methadone use. As polydrug use is common they also reported other used drugs to differentiate the effects of the drug in question. Exclusion criteria included PAE in 9/67 (13%), smoking in 5/67 (7%), and drug use in 16/67 (24%) studies. Some articles used “drug abuse” (or some other not unequivocal term) as a reason for exclusion, leaving undisclosed whether this includes alcohol and nicotine products, or only illicit drugs. They were categorized as “implied as a reason for exclusion” for alcohol and smoking. In summary, many studies did not report the use of alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs during pregnancy (Table 2). To avoid unreliable results, prenatal exposure to any drugs of abuse should either be used as a reason for exclusion or examined in detail, for example, by reporting the number of users, the amount of substance used, and the number of trimesters with any exposure, as in Chang et al. (2016). One study (May et al., 2013) compared the number of drinks used by mothers of children with different fetal alcohol spectrum disorders to mothers of normally developing controls with and without PAE. Children with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) were exposed to significantly larger amount of alcohol per week during pregnancy than controls. When examining trimesters separately, the difference in daily alcohol consumption between FAS and controls with PAE groups was only significant in the second trimester. Similarly, the extent of prenatal smoking exposure can affect brain function (Holz et al., 2014). Naturally, different substances cause different effects at different times during pregnancy; however, there is no reason to assume these basic principles of dose‐ and timing‐dependency are not universal, naturally with some variation. Furthermore, objective measures (e.g., from urine samples) would be more reliable than self‐report but are harder to acquire.

4.4. Maternal characteristics

Maternal age is an important background factor. Maternal age of 35 years or more is associated with increased risk for adverse outcomes (Lamminpää, Vehviläinen‐Julkunen, Gissler, & Heinonen, 2013; Kozuki et al., 2013). Maternal adiposity status is another important background factor, and the poor reporting of maternal weight should be considered a major deficiency in current literature. Quite a few studies excluded mothers with major medical and/or psychiatric disorders. However, it is not obvious whether this exclusion does more good by excluding possible confounding factors, or harm by making the sample not comparable to general population. Finally, many obstetric factors may also affect early brain development and brain imaging results (Knickmeyer et al., 2016). For example, delivery method was only reported in 9/67 (13%) articles, although vaginal delivery significantly increases the risk of incidental subdural hemorrhages within the first days of life (Rooks et al., 2008). However, obstetric factors are outside the scope of this review.

Socioeconomic status was most commonly measured using maternal education as a proxy, the second most common being household income. Seven articles reported Hollingshead Index of Social status which combines educational and occupational status of the parents to estimate their social status (Hollingshead, 1975). Furthermore, some studies reported class, maternal intelligence quotient (IQ), or marital status. One surprising finding is the low frequency of marital status reporting (2/67 articles, 3%), as children from two‐parent households have on average better developmental outcomes (Brown, 2010). Lower SES has been associated with lower GM volumes in several studies (Betancourt et al., 2016; Hanson et al., 2013; Jednoróg et al., 2012), lower CT in prefrontal and anterior cingulate areas in school‐age children and adolescents (Lawson, Duda, Avants, Wu, & Farah, 2013), and one study has found indirect effects on prenatal growth and GA at birth, mediated by alcohol, smoking, and cocaine use (Janisse et al., 2014). There is no clear consensus on the most useful SES measures, but we recommend reporting at least education and income, as they are the most commonly used measures and have been shown to have relevance (Betancourt et al., 2016; Hanson et al., 2013).

Race and ethnicity were both reported in 5/67 (7%) articles. These articles used the categories Hispanic and non‐Hispanic for ethnicity, and varying categories for race. Variability in used classifications complicates comparisons between studies. Differences between racial and ethnic groups have been found in feeding‐related behavior (Perrin et al., 2014), talking interactions (Cho, Holditch‐Davis, & Belyea, 2007), and marginally significant differences in brain volumes (Knickmeyer et al., 2016). Furthermore, same SNPs in certain genes have been associated with opposing neurobehavioral outcomes in groups of different ethnic background (Domschke et al., 2007). Therefore, we conclude that reporting race/ethnicity is important.

5. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REPORTING OF BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Based on these observations, we suggest that all infant neuroimaging studies report age at MRI scan (both from birth and from conception), GA at birth, sex, birth weight, maternal age, maternal weight status (BMI), race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, and either report drug, alcohol, and tobacco use during pregnancy or mention them as exclusion criteria.

6. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this review highlights that infant neuroimaging studies regarding effects of prenatal factors are scarce, especially replication studies. We identified numerous shortcomings in current approach to population description in infant MRI studies and proposed a recommendation of the minimum background information that should be reported in future studies. This would hopefully lead to a more systematic approach to future studies, and therefore allow the neuroimaging field to move more swiftly toward reliable identification of biomarkers for both desired and undesired developmental outcomes.

Finally, we must point out that this review is not exhaustive, but we believe this comprises a methodologically comparable set of studies representative of the infant neuroimaging field at large and can be used to assess the shortcomings in population descriptions of recent studies and to highlight the importance of prenatal period to brain development.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

HM was supported by Sigrid Jusélius Foundation. LK was supported by Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation. NMS was supported by the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation and the Hospital District of Southwest Finland (State research grant). HK was supported by the Academy of Finland, Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, Hospital District of Southwest Finland (State research grant). JJT was supported by the Hospital District of Southwest Finland (State research grant), Emil Aaltonen foundation and Alfred Kordelin foundation.

Pulli EP, Kumpulainen V, Kasurinen JH, et al. Prenatal exposures and infant brain: Review of magnetic resonance imaging studies and a population description analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:1987–2000. 10.1002/hbm.24480

Funding information Alfred Kordelin foundation; Emil Aaltonen foundation; Hospital District of Southwest Finland; Hospital District of Southwest Finland; Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation; Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation; Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation; Academy of Finland; Hospital District of Southwest Finland; Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation; Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation; Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation; Sigrid Jusélius Foundation

REFERENCES

- Anderson, M. E. , Johnson, D. C. , & Batal, H. A. (2005). Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and prenatal maternal smoking: Rising attributed risk in the Back to Sleep era. BMC Medicine, 3, 4 10.1186/1741-7015-3-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, S. L. , Fennema‐Notestine, C. , Gamst, A. , Riley, E. P. , Mattson, S. N. , & Jernigan, T. L. (2001). Brain dysmorphology in individuals with severe prenatal alcohol exposure. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 43(3), 148–154. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2001.tb00179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas, D. , Aleman, A. , & Kahn, R. S. (2004). Lateralization of amygdala activation: A systematic review of functional neuroimaging studies. Brain Research Reviews, 45(2), 96–103. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard, V. L. , Williams, L. M. , & Siegel, J. A. (2001). The long‐term mental health consequences of child sexual abuse: An exploratory study of the impact of multiple traumas in a sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14(4), 697–715. 10.1023/A:1013085904337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basatemur, E. , Gardiner, J. , Williams, C. , Melhuish, E. , Barnes, J. , & Sutcliffe, A. (2013). Maternal prepregnancy BMI and child cognition: A longitudinal cohort study. Pediatrics, 131(1), 56–63. 10.1542/peds.2012-0788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, L. J. , Appleyard, K. , & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82(1), 162–176. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, L. M. , Avants, B. , Farah, M. J. , Brodsky, N. L. , Wu, J. , Ashtari, M. , & Hurt, H. (2016). Effect of socioeconomic status (SES) disparity on neural development in female African‐American infants at age 1 month. Developmental Science, 19(6), 947–956. 10.1111/desc.12344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, R. E. , Victora, C. G. , Walker, S. P. , Bhutta, Z. A. , Christian, P. , de Onis, M. , … Uauy, R. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low‐income and middle‐income countries. The Lancet, 382(9890), 427–451. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock, J. , Wainstock, T. , Braun, K. , & Segal, M. (2015). Stress in utero: Prenatal programming of brain plasticity and cognition. Biological Psychiatry, 78(5), 315–326. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J. D. , Randall, P. , Vermetten, E. , Staib, L. , Bronen, R. A. , Mazure, C. , … Charney, D. S. (1997). Magnetic resonance imaging‐based measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood physical and sexual abuse—a preliminary report. Biological Psychiatry, 41(1), 23–32. 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00162-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. L. (2010). Marriage and child well‐being: Research and policy perspectives. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72(5), 1059–1077. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00750.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion, V. G. , Weems, C. F. , & Reiss, A. L. (2007). Stress predicts brain changes in children: A pilot longitudinal study on youth stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, and the hippocampus. Pediatrics, 119(3), 509–516. 10.1542/peds.2006-2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L. , Oishi, K. , Skranes, J. , Buchthal, S. , Cunningham, E. , Yamakawa, R. , … Ernst, T. (2016). Sex‐specific alterations of white matter developmental trajectories in infants with prenatal exposure to methamphetamine and tobacco. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(12), 1217–1227. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J. , Holditch‐Davis, D. , & Belyea, M. (2007). Gender and racial differences in the looking and talking behaviors of mothers and their 3‐year‐old prematurely born children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 22(5), 356–367. 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. , Joseph, L. , & Pilote, L. (2013). Obesity and C‐reactive protein in various populations: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 14(3), 232–244. 10.1111/obr.12003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor, J. R. , & Menzies, S. L. (1996). Relationship of iron to oligondendrocytes and myelination. Glia, 17(2), 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domschke, K. , Deckert, J. , O'Donovan, M. C. , & Glatt, S. J. (2007). Meta‐analysis of COMT val158met in panic disorder: Ethnic heterogeneity and gender specificity. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 144B(5), 667–673. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald, K. A. , Eastman, E. , Howells, F. M. , Adnams, C. , Riley, E. P. , Woods, R. P. , … Stein, D. J. (2015). Neuroimaging effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the developing human brain: A magnetic resonance imaging review. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 27(05), 251–269. 10.1017/neu.2015.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald, K. A. , Fouche, J. P. , Roos, A. , Koen, N. , Howells, F. M. , Riley, E. P. , … Stein, D. J. (2016). Alcohol exposure in utero is associated with decreased gray matter volume in neonates. Metabolic Brain Disease, 31(1), 81–91. 10.1007/s11011-015-9771-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald, K. A. , Ipser, J. C. , Howells, F. M. , Roos, A. , Fouche, J.‐P. , Riley, E. P. , … Stein, D. J. (2016). Interhemispheric functional brain connectivity in neonates with prenatal alcohol exposure: Preliminary findings. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(1), 113–121. 10.1111/acer.12930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald, K. A. , Roos, A. , Fouche, J.‐P. , Koen, N. , Howells, F. M. , Woods, R. P. , … Stein, D. J. (2015). A study of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on white matter microstructural integrity at birth. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 27(04), 197–205. 10.1017/neu.2015.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, J. , Kulikova, S. , Poupon, C. , & Hu, P. S. (2014). The early development of brain white matter: A review of imaging studies in fetuses, newborns and infants. Neuroscience, 276, 48–71. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikenes, L. , Martinussen, M. P. , Lund, L. K. , Løhaugen, G. C. , Indredavik, M. S. , Jacobsen, G. W. , … Håberg, A. K. (2012). Being born small for gestational age reduces white matter integrity in adulthood: A prospective cohort study. Pediatric Research, 72(6), 649–654. 10.1038/pr.2012.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertem, I. O. , Leventhal, J. M. , & Dobbs, S. (2000). Intergenerational continuity of child physical abuse: How good is the evidence? The Lancet, 356(9232), 814–819. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02656-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes, M. L. , & McAllister, A. K. (2016). Maternal immune activation: Implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science (New York, N.Y.), 353(6301), 772–777. 10.1126/science.aag3194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W. , Grewen, K. , Knickmeyer, R. C. , Qiu, A. , Salzwedel, A. , Lin, W. , & Gilmore, J. H. (2018). A review on neuroimaging studies of genetic and environmental influences on early brain development. NeuroImage, in press. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2018.04.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, A. M. , Rasmussen, J. M. , Rudolph, M. D. , Heim, C. M. , Gilmore, J. H. , Styner, M. , … Buss, C. (2018). Maternal systemic interleukin‐6 during pregnancy is associated with newborn amygdala phenotypes and subsequent behavior at 2 years of age. Biological Psychiatry, 83(2), 109–119. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, K. S. , Petroff, R. , Isoherranen, N. , Stella, N. , & Burbacher, T. M. (2017). Cannabis use during pregnancy: Pharmacokinetics and effects on child development. Pharmacology & Therapeutics., 182, 133–151. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, B. B. , Kappil, M. , Lambertini, L. , Armstrong, D. A. , Guerin, D. J. , Sharp, A. J. , … Marsit, C. J. (2015). Expression of imprinted genes in placenta is associated with infant neurobehavioral development. Epigenetics, 10(9), 834–841. 10.1080/15592294.2015.1073880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewen, K. , Burchinal, M. , Vachet, C. , Gouttard, S. , Gilmore, J. H. , Lin, W. , … Gerig, G. (2014). Prenatal cocaine effects on brain structure in early infancy. NeuroImage, 101, 114–123. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habas, P. A. , Scott, J. A. , Roosta, A. , Rajagopalan, V. , Kim, K. , Rousseau, F. , … Studholme, C. (2012). Early folding patterns and asymmetries of the normal human brain detected from in utero MRI. Cerebral Cortex, 22(1), 13–25. Retrieved from. 10.1093/cercor/bhr053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanieh, S. , Ha, T. T. , Simpson, J. A. , Thuy, T. T. , Khuong, N. C. , Thoang, D. D. , … Biggs, B.‐A. (2014). Maternal vitamin d status and infant outcomes in rural Vietnam: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One, 9(6), e99005 10.1371/journal.pone.0099005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J. L. , Hair, N. , Shen, D. G. , Shi, F. , Gilmore, J. H. , Wolfe, B. L. , & Pollak, S. D. (2013). Family poverty affects the rate of human infant brain growth. PLoS One, 8(12), e80954 10.1371/journal.pone.0080954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim, C. , Shugart, M. , Craighead, W. E. , & Nemeroff, C. B. (2010). Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychobiology, 52(7), 671–690. 10.1002/dev.20494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead, A. (1975). Four factor index of social status. Yale Journal of Sociology, 8, 21–52. [Google Scholar]

- Holz, N. E. , Boecker, R. , Baumeister, S. , Hohm, E. , Zohsel, K. , Buchmann, A. F. , … Laucht, M. (2014). Effect of prenatal exposure to tobacco smoke on inhibitory control. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(7), 786–796. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton, M. K. , Margolis, A. E. , Tang, C. , & Wright, R. (2014). Neuroimaging is a novel tool to understand the impact of environmental chemicals on neurodevelopment. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 26(2), 230–236. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inder, T. E. , Warfield, S. K. , Wang, H. , Hüppi, P. S. , & Volpe, J. J. (2005). Abnormal cerebral structure is present at term in premature infants. Pediatrics, 115(2), 286–294. 10.1542/peds.2004-0326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, S. W. , Jacobson, J. L. , Molteno, C. D. , Warton, C. M. R. , Wintermark, P. , Hoyme, H. E. , … Meintjes, E. M. (2017). Heavy prenatal alcohol exposure is related to smaller corpus callosum in newborn MRI scans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(5), 965–975. 10.1111/acer.13363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janisse, J. J. , Bailey, B. A. , Ager, J. , & Sokol, R. J. (2014). Alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, and marijuana use: Relative contributions to preterm delivery and fetal growth restriction. Substance Abuse, 35(1), 60–67. 10.1080/08897077.2013.804483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jednoróg, K. , Altarelli, I. , Monzalvo, K. , Fluss, J. , Dubois, J. , Billard, C. , … Ramus, F. (2012). The influence of socioeconomic status on children's brain structure. PLoS One, 7(8), e42486 10.1371/journal.pone.0042486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha, S. C. , Meltzer‐Brody, S. , Steiner, R. J. , Cornea, E. , Woolson, S. , Ahn, M. , … Knickmeyer, R. C. (2016). Antenatal depression, treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and neonatal brain structure: A propensity‐matched cohort study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 253, 43–53. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha, S. C. , Xia, K. , Ahn, M. , Girault, J. B. , Li, G. , Wang, L. , … Knickmeyer, R. C. (2018). Environmental influences on infant cortical thickness and surface area. Cerebral Cortex, in press. 10.1093/cercor/bhy020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapellou, O. , Counsell, S. J. , Kennea, N. , Dyet, L. , Saeed, N. , Stark, J. , … Edwards, A. D. (2006). Abnormal cortical development after premature birth shown by altered allometric scaling of brain growth. PLoS Medicine, 3(8), e265 Retrieved from. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, L. , Tolvanen, M. , Scheinin, N. M. , Uusitupa, H.‐M. , Korja, R. , Ekholm, E. , … Karlsson, H. (2018). Cohort profile: The FinnBrain birth cohort study (FinnBrain). International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(1), 15–16. 10.1093/ije/dyx173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickmeyer, R. C. , Gouttard, S. , Kang, C. , Evans, D. , Wilber, K. , Smith, J. K. , … Gilmore, J. H. (2008). A structural MRI study of human brain development from birth to 2 years. The Journal of neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 28(47), 12176–12182. 10.1523/jneurosci.3479-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickmeyer, R. C. , Xia, K. , Lu, Z. , Ahn, M. , Jha, S. C. , Zou, F. , … Gilmore, J. H. (2016). impact of demographic and obstetric factors on infant brain volumes: A population neuroscience study. Cerebral Cortex, 27, 331 10.1093/cercor/bhw331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolschijn, P. C. M. P. , van IJzendoorn, M. H. , Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M. J. , & Crone, E. A. (2013). Hippocampal volume and internalizing behavior problems in adolescence. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(7), 622–628. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozuki, N. , Lee, A. C. , Silveira, M. F. , Sania, A. , Vogel, J. P. , Adair, L. , … Katz, J. (2013). The associations of parity and maternal age with small‐for‐gestational‐age, preterm, and neonatal and infant mortality: A meta‐analysis. BMC Public Health, 13(Suppl 3), S2 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers, D. S. , & Clark, K. E. (1996). The maternal and fetal physiologic effects of nicotine. Seminars in Perinatology, 20(2), 115–126. 10.1016/S0146-0005(96)80079-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamminpää, R. , Vehviläinen‐Julkunen, K. , Gissler, M. , & Heinonen, S. (2013). Smoking among older childbearing women ‐ a marker of risky health behaviour a registry‐based study in Finland. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1179 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, G. M. , Duda, J. T. , Avants, B. B. , Wu, J. , & Farah, M. J. (2013). Associations between children's socioeconomic status and prefrontal cortical thickness. Developmental Science, 16(5), 641–652. 10.1111/desc.12096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.‐M. , Ou, J.‐J. , Liu, L. , Zhang, D. , Zhao, J.‐P. , & Tang, S.‐Y. (2016). Association between maternal obesity and autism spectrum disorder in offspring: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 95–102. 10.1007/s10803-015-2549-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsell, L. , Malouf, R. , Morris, J. , Kurinczuk, J. J. , & Marlow, N. (2015). Prognostic factors for poor cognitive development in children born very preterm or with very low birth weight: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(12), 1162–1172. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lövblad, K.‐O. , Ramelli, G. , Remonda, L. , Nirkko, A. C. , Ozdoba, C. , & Schroth, G. (1997). Retardation of myelination due to dietary vitamin B12 deficiency: Cranial MRI findings. Pediatric Radiology, 27(2), 155–158. 10.1007/s002470050090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques, A. H. , Bjørke‐Monsen, A.‐L. , Teixeira, A. L. , & Silverman, M. N. (2015). Maternal stress, nutrition and physical activity: Impact on immune function, CNS development and psychopathology. Brain Research, 1617, 28–46. 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May, P. A. , Blankenship, J. , Marais, A.‐S. , Gossage, J. P. , Kalberg, W. O. , Joubert, B. , … Seedat, S. (2013). Maternal alcohol consumption producing fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD): Quantity, frequency, and timing of drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 133(2), 502–512. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, A. S. d. O. , Aguiar, R. S. , Amorim, M. M. R. , Arruda, M. B. , Melo, F. d. O. , Ribeiro, S. T. C. , … Tanuri, A. (2016). Congenital Zika virus infection: Beyond neonatal microcephaly. JAMA Neurology, 73(12), 1407 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minozzi, S. , Amato, L. , Bellisario, C. , Ferri, M. , & Davoli, M. (2013). Maintenance agonist treatments for opiate‐dependent pregnant women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD006318 10.1002/14651858.CD006318.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk, C. , Georgieff, M. K. , Xu, D. , Hao, X. , Bansal, R. , Gustafsson, H. , … Peterson, B. S. (2016). Maternal prenatal iron status and tissue organization in the neonatal brain. Pediatric Research, 79(3), 482–488. 10.1038/pr.2015.248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnelly, V. J. , Anblagan, D. , Quigley, A. , Cabez, M. B. , Cooper, E. S. , Mactier, H. , … Boardman, J. P. (2018). Prenatal methadone exposure is associated with altered neonatal brain development. NeuroImage: Clinical, 18, 9–14. 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moog, N. K. , Entringer, S. , Rasmussen, J. M. , Styner, M. , Gilmore, J. H. , Kathmann, N. , … Buss, C. (2018). Intergenerational effect of maternal exposure to childhood maltreatment on newborn brain anatomy. Biological Psychiatry, 83(2), 120–127. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, K. U. , Mennigen, E. , Ripke, S. , Banaschewski, T. , Barker, G. J. , Büchel, C. , … Smolka, M. N. (2013). Altered reward processing in adolescents with prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(8), 847–856. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardelli, A. , Lebel, C. , Rasmussen, C. , Andrew, G. , & Beaulieu, C. (2011). Extensive deep gray matter volume reductions in children and adolescents with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 35(8), 1404–1417. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01476.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou, X. , Thakali, K. M. , Shankar, K. , Andres, A. , & Badger, T. M. (2015). Maternal adiposity negatively influences infant brain white matter development: Maternal obesity and infant brain. Obesity, 23(5), 1047–1054. 10.1002/oby.21055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, N. , Junqué, C. , Figueras, F. , Sanz‐Cortes, M. , Bargalló, N. , Arranz, A. , … Gratacos, E. (2014). Differential vulnerability of gray matter and white matter to intrauterine growth restriction in preterm infants at 12 months corrected age. Brain Research, 1545, 1–11. 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A. , Prakash, A. A. , Das, P. K. , Gupta, S. , Pusdekar, Y. V. , & Hibberd, P. L. (2018). Maternal anemia and underweight as determinants of pregnancy outcomes: Cohort study in eastern rural Maharashtra, India. BMJ Open, 8(8), e021623 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, E. M. , Rothman, R. L. , Sanders, L. M. , Skinner, A. C. , Eden, S. K. , Shintani, A. , … Yin, H. S. (2014). Racial and ethnic differences associated with feeding‐ and activity‐related behaviors in infants. Pediatrics, 133(4), e857–e867. 10.1542/peds.2013-1326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, A. , Rifkin‐Graboi, A. , Chen, H. , Chong, Y.‐S. , Kwek, K. , Gluckman, P. D. , … Meaney, M. J. (2013). Maternal anxiety and infants' hippocampal development: Timing matters. Translational Psychiatry, 3, e306 10.1038/tp.2013.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, A. , Shen, M. , Buss, C. , Chong, Y.‐S. , Kwek, K. , Saw, S.‐M. , … Meaney, M. J. (2017). Effects of antenatal maternal depressive symptoms and socio‐economic status on neonatal brain development are modulated by genetic risk. Cerebral Cortex, 27(5), 3080–3092. 10.1093/cercor/bhx065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, A. , Tuan, T. A. , Ong, M. L. , Li, Y. , Chen, H. , Rifkin‐Graboi, A. , … Meaney, M. J. (2014). COMT haplotypes modulate associations of antenatal maternal anxiety and neonatal cortical morphology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(2), 163–172. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooks, V. J. , Eaton, J. P. , Ruess, L. , Petermann, G. W. , Keck‐Wherley, J. , & Pedersen, R. C. (2008). Prevalence and evolution of intracranial hemorrhage in asymptomatic term infants. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 29(6), 1082–1089. 10.3174/ajnr.A1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotem‐Kohavi, N. , & Oberlander, T. F. (2017). Variations in neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with prenatal ssri antidepressant exposure. Birth Defects Research, 109(12), 909–923. 10.1002/bdr2.1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch, B. D. , Abercrombie, H. C. , Oakes, T. R. , Schaefer, S. M. , & Davidson, R. J. (2001). Hippocampal morphometry in depressed patients and control subjects: Relations to anxiety symptoms. Biological Psychiatry, 50(12), 960–964. 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01248-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzwedel, A. P. , Grewen, K. M. , Goldman, B. D. , & Gao, W. (2016). Thalamocortical functional connectivity and behavioral disruptions in neonates with prenatal cocaine exposure. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 56, 16–25. 10.1016/j.ntt.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA . (2016, September). Reports and Detailed Tables From the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/samhsa-data-outcomes-quality/major-data-collections/reports-detailed-tables-2015-NSDUH

- Shaw, P. , Greenstein, D. , Lerch, J. , Clasen, L. , Lenroot, R. , Gogtay, N. , … Giedd, J. (2006). Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature, 440(7084), 676–679. 10.1038/nature04513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirnes, E. , Griffiths, S. T. , Aukland, S. M. , Eide, G. E. , Elgen, I. B. , & Gundersen, H. (2018). Functional MRI in prenatally opioid‐exposed children during a working memory‐selective attention task. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 66, 46–54. 10.1016/j.ntt.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirnes, E. , Oltedal, L. , Bartsch, H. , Eide, G. E. , Elgen, I. B. , & Aukland, S. M. (2017). Brain morphology in school‐aged children with prenatal opioid exposure: A structural MRI study. Early Human Development, 106–107, 33–39. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin, T. A. (1998). Fetal nicotine or cocaine exposure: Which one is worse? The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 285(3), 931–945. Retrieved from. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9618392 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell, E. R. , Thompson, P. M. , Leonard, C. M. , Welcome, S. E. , Kan, E. , & Toga, A. W. (2004). Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and brain growth in normal children. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(38), 8223–8231. 10.1523/jneurosci.1798-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]