Abstract

The prognostic significance of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in Wilms' tumor (WT) remains unclear. The present study identified differential lncRNA expression patterns between WT and normal tissues; and evaluated the prognostic value of these lncRNAs. Multidimensional data from 136 samples were retrieved from the Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) database. Computational data analyses were performed to detect survival-associated molecular signatures. Kaplan-Meier survival curves revealed the prognostic prediction values for three of these lncRNAs, namely DLGAP1 antisense RNA 2 (DLGAP1-AS2), RP11-93B14.6 and RP11554F20.1. Cox regression analysis revealed that the three-lncRNA signature was significantly associated with patient survival (P<0.01). Functional enrichment analyses suggested that the target genes of these three lncRNAs may be involved in known cancer-associated pathways. The present study revealed a three-lncRNA signature consisting of DLGAP1-AS2, RP11-93B14.6 and RP11554F20.1 that may be used as a prognostic marker for patients with WT.

Keywords: Wilms' tumor, long non-coding RNAs, survival

Introduction

Wilms tumor (WT) is the most common type of renal cancer in children between the ages 0 and 14 years, with an incidence rate of 9 in 1 million children, based on November 2017 SEER data submission (1,2). As such, close attention is being paid to this major global public health issue (3,4). The incidence of WT in children <15 years of age in the United States of America is ~7–8 cases per million, with ~500 new cases per year (5). Although the prognosis of children with WT has improved due to multimodal therapies, WT continue to recur even five years post-diagnosis (6–8). Thus, considering the disease's severity, the early diagnosis of WT and investigation of the molecular mechanisms associated with the development of the disease are of great importance. Effective biomarkers for the early detection of WT are urgently needed to improve the quality of life and survival of patients with WT.

Technological advances in genomic and transcriptomic analysis have led to the identification of various types of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) (9,10). Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which consist of >200 nucleotides, account for a large number of ncRNAs (11). Emerging evidence indicates that lncRNAs are important in genetic, post-transcriptional and epigenetic regulation (12,13). In addition, a growing number of studies suggest that lncRNAs are involved in cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis (14,15). Therefore, lncRNAs may serve as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for WT (16,17). However, knowledge of the association between lncRNAs and prognosis in patients with WT is limited (18). The present study investigated differential lncRNA expression patterns between WT and normal tissues, and revealed a three-lncRNA signature that may predict the survival time of patients with WT.

Materials and methods

Acquisition of therapeutically applicable research to generate effective treatments (TARGET) data

Raw lncRNA expression data and corresponding clinical information were downloaded from the TARGET database (ocg.cancer.gov/programs/target) Version: December, 2018. Samples obtained from patients with an overall survival (OS) of more than one month were included in the present study. Additionally, the patient clinical information, differentially expressed lncRNAs and prognosis information were downloaded. A total of 136 samples, including 130 WT tissues and six normal tissues, were investigated in the present study. The detailed clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table I. R language package (edgeR, Release 3.9; http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html) was used to interpret lncRNA sequencing data and the limma package (Release 3.9; http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) was used to analyze differentially expressed lncRNAs between WT and normal tissues. Fold-changes (FCs) in the expression of individual lncRNAs were calculated, and differentially expressed lncRNAs with log2|FC| >1.0 and P<0.05 were considered significant.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the subjects.

| All subjects (n=136) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | No. | % |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 76 | 55.9 |

| Male | 60 | 44.1 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| <4 | 62 | 45.6 |

| ≥4 | 74 | 54.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 98 | 72.1 |

| African-American | 20 | 14.7 |

| Not available | 18 | 13.2 |

| Stage | ||

| I+II | 73 | 53.7 |

| III+IV+V | 63 | 46.3 |

Patient prognosis and target gene prediction

Differentially expressed lncRNA profiles were normalized following log2 transformation. The Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test were used to evaluate the prognostic value of each differentially expressed lncRNA. Three lncRNAs that were significantly associated with OS were identified as prognostic lncRNAs and were subjected to receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and Cox regression analyses. The Cox model was used to investigate the association between the expression of each lncRNA and OS according to age, ethnicity, gender and disease stage. lncRNAs with hazard ratios (HRs) <1 were defined as protective, while those with HRs >1 were defined as high-risk. Eventually, a prognostic lncRNA signature was constructed, and patients with WT were classified into low- and high-risk groups using the median risk score as the cut-off value. Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test were used to evaluate differences in patient survival between the two groups. ROC analysis was performed to compare the sensitivity and specificity of the survival prediction based on the lncRNA risk score. Protein-coding genes (PCGs) genes correlated with the differentially expressed lncRNAs were identified using the co-expression method. The PCGs with a Pearson's correlation coefficient >0.40 and P<0.01 were considered to be associated with the lncRNAs. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) and Gene Ontology (GO; http://david.ncifcrf.gov/) enrichment analyses were subsequently performed for the target genes. P<0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Statistical analysis

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression and Kaplan-Meier survival analyses with log-rank test were used to compare each lncRNA (low vs. high expression level) and their prognostic signatures (low vs. high risk). Hazard ratio (95% CI) was expressed in the Cox regression analysis. The data for categorical variables were presented as percentages (%). Pearson's correlation test and log-rank test were also used in this study. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.5.1; www.r-project.org) (19) and SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS Inc.).

Results

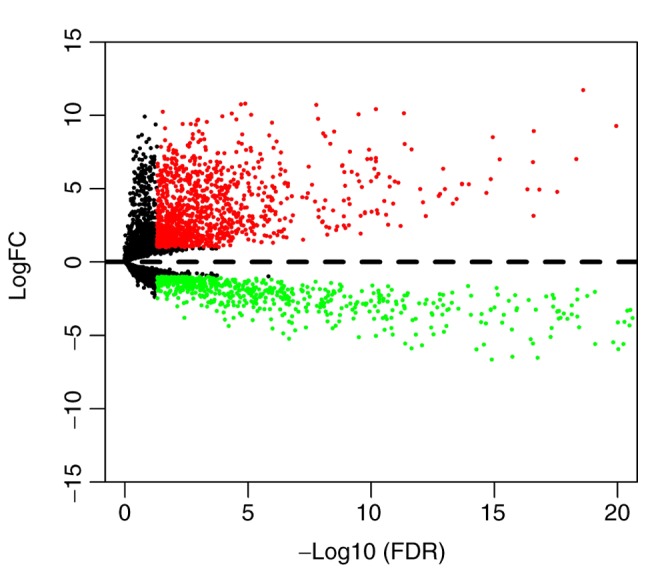

Characteristics of the differentially expressed lncRNAs

The present study investigated 136 samples, including 130 WT and 6 normal tissues. The detailed clinical characteristics, including gender, ethnicity, age at diagnosis and disease stage, are presented in Table I. A total of 1,833 differentially expressed lncRNAs, including 1,087 upregulated and 746 downregulated lncRNAs, were identified between WT and normal tissues (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Volcano plot of differentially expressed lncRNAs. Red and green dots represent upregulated and downregulated lncRNAs, respectively. Black dots represent lncRNAs with no differential expression (P>0.05) and dashed line represent logFC=0. lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; FC, fold-change; FDR, false discovery rate.

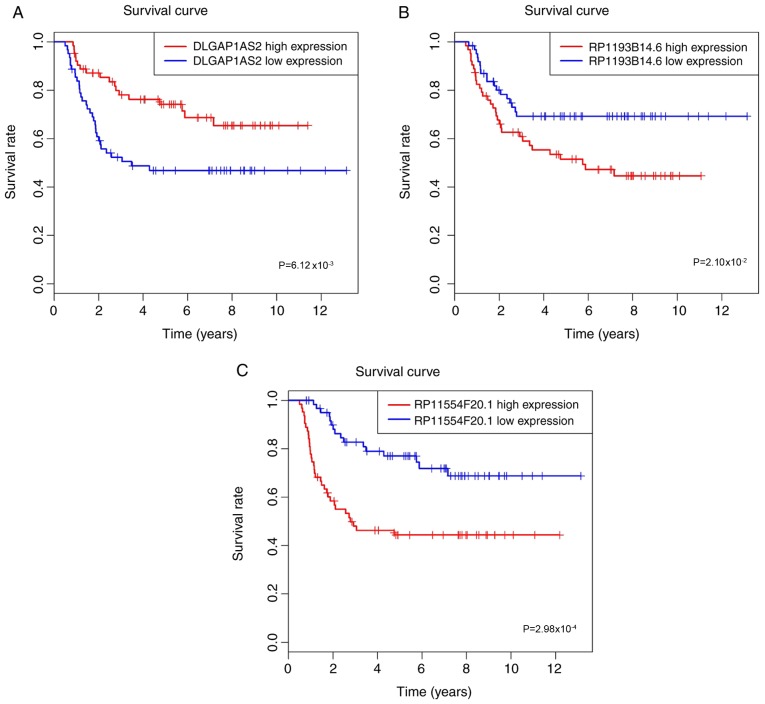

Association between the three lncRNAs and OS in patients with WT

The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to evaluate the association between OS and lncRNA expression patterns. As depicted in Fig. 2, two upregulated lncRNAs (RP11-93B14.6 and RP11554F20.1) and one downregulated lncRNA (DLGAP1-AS2), were significantly associated with OS rate (all P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test revealed that three lncRNAs were associated with overall survival in patients with Wilms' tumor. The patients were divided into low and high expression levels group according to the median value. (A) DLGAP1-AS2, (B) RP11-93B14.6 and (C) RP11554F20.1. DLGAP1-AS2, DLGAP1 antisense RNA 2.

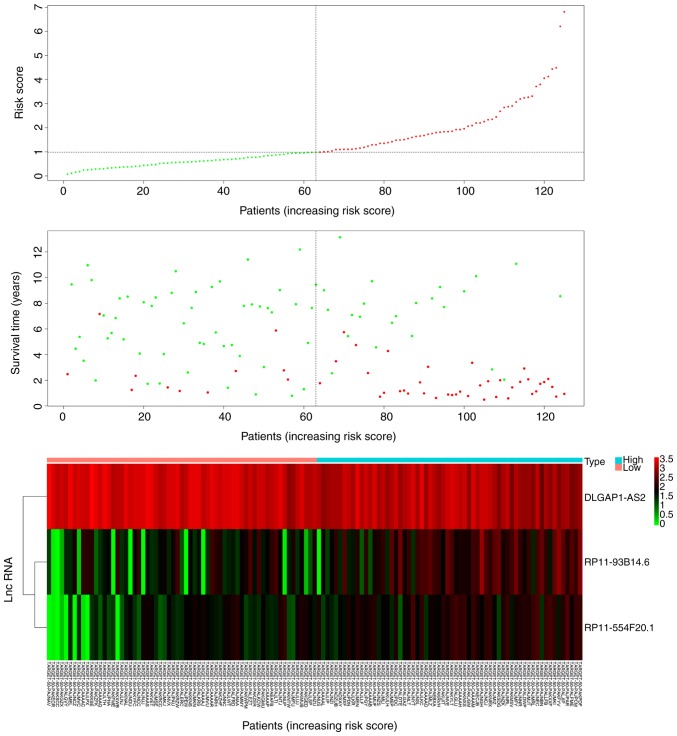

Prognostic value of the three-lncRNA signature risk scores for WT

A prognostic signature was identified by integrating three lncRNA expression profiles and the corresponding estimated regression coefficient. The 130 patients investigated in the present study were subsequently divided into high- and low-risk groups (n=65 per group) according to the median risk score. Patients in the high-risk group had a significantly worse OS than those in the low-risk group (P<0.001; Fig. S1). The prognostic ability of the three-lncRNA signature was evaluated using ROC curve analysis. Results revealed that the area under the ROC curve of the three-lncRNA signature was 0.80 (Fig. S2).

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to determine the effects of the three-lncRNA signature (high vs. low risk) on OS (Tables II and III). In univariate models, gender (HR=1.94; P=0.015), disease stage (HR=2.65; P<0.001), DLGAP1-AS2 signature (HR=0.60; P<0.001), RP11-93B14.6 signature (HR=1.37; P<0.001) and RP11-554F20.1 signature (HR=1.92; P<0.001) were all independent factors associated with OS in patients with WT. In multivariate models, gender (HR=3.10; P<0.001), stage (HR=3.36; P<0.001), DLGAP1-AS2 signature (HR=0.60; P=0.001), RP11-93B14.6 signature (HR=1.30; P=0.006) and RP11-554F20.1 signature (HR=2.26; P<0.001) were associated with OS in patients with WT.

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models in patients with Wilm's tumor.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Gender | ||||

| Male vs. female | 1.94 (1.14–3.31) | 0.015 | 3.10 (1.71–5.60) | <0.001 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| ≥4 vs. <4 | 1.09 (0.64–1.86) | 0.749 | 0.61 (0.33–1.14) | 0.122 |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian vs. othersa | 0.90 (0.50–1.61) | 0.717 | 0.68 (0.36–1.28) | 0.233 |

| Stage | ||||

| III+IV+V vs. I+II | 2.65 (1.53–4.59) | <0.001 | 3.36 (1.89–5.96) | <0.001 |

| DLGAP1-AS2 signature | ||||

| High risk vs. low risk | 0.60 (0.46–0.78) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.45–0.80) | 0.001 |

| RP11-93B14.6 signature | ||||

| High risk vs. low risk | 1.37 (1.15–1.64) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.08–1.56) | 0.006 |

| RP11-554F20.1 signature | ||||

| High risk vs. low risk | 1.92 (1.39–2.66) | <0.001 | 2.26 (1.60–3.18) | <0.001 |

African descent and unknown. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table III.

Three lncRNA signatures in unadjusted and adjusted models.

| Unadjusted | Mode 1 | Mode 2 | Mode 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| DLGAP1-AS2 signature | 0.60 (0.46–0.78) | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.46–0.80) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.46–0.80) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.45–0.80) | 0.001 |

| RP11-93B14.6 signature | 1.37 (1.15–1.64) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.04–1.49) | 0.017 | 1.27 (1.05–1.52) | 0.012 | 1.30 (1.08–1.56) | 0.006 |

| RP11-554F20.1 signature | 1.92 (1.39–2.66) | <0.001 | 2.42 (1.67–3.49) | <0.001 | 2.38 (1.65–3.44) | <0.001 | 2.26 (1.60–3.18) | <0.001 |

Mode 1, adjusted for age and gender; mode 2; adjusted for age, gender and race; mode 3, adjusted for age, gender, race and stage; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Patients in the low-risk group expressed increased levels of the protective lncRNA (DLGAP1-AS2) compared with patients in the high-risk group (P<0.05; Fig. 3). Patients in the high-risk group expressed increased levels of RP11-93B14.6 and RP11-554F20.1 compared with the low-risk group (P<0.05; Fig. 3). In addition, patients in the low-risk group had a significantly longer survival time than those in the high-risk group (P<0.05; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Three lncRNAs based risk score distribution, patients' event-free survival time and a heatmap of the expression profiles of the three lncRNA. Red dots represent the high-risk group and green dots represent the low-risk group.

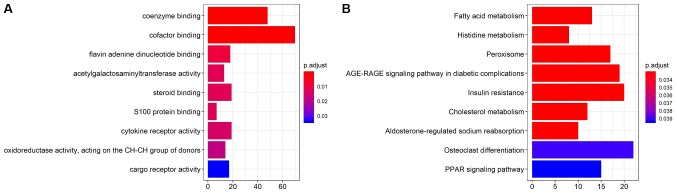

lncRNA target prediction and functional GO and KEGG analysis

A co-expression method was used to predict the potential target of the three lncRNAs of interest. GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses were performed to elucidate the biological functions of the associated target genes (Fig. 4). GO biological process, molecular function and cellular component terms were mainly enriched in ‘coenzyme binding’, ‘cofactor binding’, ‘flavin adenine dinucleotide binding’, ‘acetylgalactosaminyltransferase activity’ and ‘steroid binding’ (P<0.05). In addition, KEGG pathways were significantly enriched in ‘fatty acid metabolism’, ‘histidine metabolism’, ‘peroxisome’, ‘AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complication’ and ‘insulin resistance’ (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

(A) The Gene Ontology and (B) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analyses.

Discussion

WT is currently the most common primary malignant renal tumor in children (20). Although outcomes have improved due to multidisciplinary treatments, chemotherapeutic drugs and radiotherapy, the incidence and recurrence of WT remains high, and presents a heavy burden for patients, families and medical institutions (21–23). The prognosis of patients with WT may be considerably improved if the characteristics of the tumor, including clinical symptoms and genetic phenotypes, are reliably predicted at the time of initial diagnosis (18). Therefore, there is a requirement for the identification of prognostic biomarkers as well as the investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of WT.

A number of previously studies have revealed that genetic factors may contribute to the development of WT (2,18). Furthermore, studies have indicated that altered lncRNA expression levels are associated with disease development; however, their prognostic values have not been thoroughly investigated (18,24). Therefore, the present study identified three differentially expressed lncRNAs, which were correlated with OS in patients with WT. The lncRNAs, including DLGAP1-AS2, RP11-93B14.6 and RP11554F20.1, were validated as independent prognostic factors for patients with WT. Additionally, the target genes of the three lncRNAs, as well as their enrichment pathways and biological functions, were investigated using bioinformatics. The results suggested that these three lncRNAs may participate in the molecular pathogenesis, clinical progression and prognosis of WT, highlighting the potential of lncRNA profiling to improve the clinical prognosis in patients with WT.

Previous studies have demonstrated that functional lncRNA expression plays an important role in carcinogenesis and strongly correlates with gene expression and pathway regulation (25,26). lncRNAs promote tumor formation, progression and metastasis by regulating various major pathways, including cancer cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, differentiation, adhesion, migration, invasion and survival (27,28). Zhu et al (24) reported that upregulated expression of long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 473 was associated with the molecular pathogenesis of WT via the miR-195/IKK complex α signaling pathway. However, the sample size, sample types and number of lncRNAs assessed were limited.

The present study analyzed high-throughput data and identified two upregulated lncRNAs (RP11-93B14.6 and RP11554F20.1) and one downregulated lncRNA (DLGAP1-AS2) associated with the clinical outcomes of patients with WT. Therefore, the expression levels of these three lncRNAs may serve as prognostic markers for WT. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, the functions of these lncRNAs have not been previously investigated. The results of the present study revealed that RP11-93B14.6, RP11554F20.1 and DLGAP1-AS2 were enriched in ‘coenzyme binding’, ‘cofactor binding’, ‘fatty acid metabolism’, ‘histidine metabolism’, ‘peroxisome’, ‘AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complication’ and ‘insulin resistance’, all of which are classical signaling pathways closely associated with tumorigenesis and the progression of malignancies (29,30). However, further molecular investigations in patients with WT are required to validate these results and to inform new therapeutic interventions.

The present study had several limitations. Firstly, the mechanisms underlying the prognostic values of the three lncRNAs were not investigated and warrant experimental studies. Secondly, a single published dataset with a small sample size was used. Therefore, the results obtained may differ from the general population. Thirdly, this study is not an intervention and treatment experiment, therefore data on the therapeutic effect of WT cannot be obtained. Finally, the WT cohort had a relatively high censor rate, which may have affected the reliability of the Kaplan-Meier estimates. Thus, a larger and multicenter clinical cohort study is required to validate the results obtained in the present study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- lncRNAs

long non-coding RNAs

- WT

Wilms' tumor

- TARGET

Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments

- ncRNAs

non-coding RNAs

- PCGs

protein-coding genes

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- AGE-RAGE

advanced glycation end product-receptor of advanced glycation end product

- OS

overall survival

- FC

fold-change

- HR

hazard ratio

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GO

Gene Ontology

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available in the TARGET repository, https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/target.

Authors' contributions

PR contributed to the conception, design and final approval of the submitted version. MH contributed to the interpretation of data and completion of figures and tables. Both authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participant

The study was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the TARGET publication guidelines.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Noone A, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2015, based on November 2017 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website, April 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott RH, Stiller CA, Walker L, Rahman N. Syndromes and constitutional chromosomal abnormalities associated with Wilms tumour. J Med Genet. 2006;43:705–715. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dome JS, Graf N, Geller JI, Fernandez CV, Mullen EA, Spreafico F, Van den Heuvel-Eibrink M, Pritchard-Jones K. Advances in Wilms tumor treatment and biology: Progress through international collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2999–3007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Angelo P, Di Cataldo A, Terenziani M, Bisogno G, Collini P, Di Martino M, Melchionda F, Mosa C, Nantron M, Perotti D, et al. Factors possibly affecting prognosis in children with Wilms' tumor diagnosed before 24 months of age: A report from the Associazione Italiana Ematologia Oncologia Pediatrica (AIEOP) Wilms tumor working group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017:64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26644. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein L, Linet M, Smith M. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1999. Renal tumors; pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell C, Pritchard-Jones K, Shannon R, Hutton C, Stevens S, Machin D, Imeson J, Kelsey A, Vujanic GM, Gornall P, et al. Immediate nephrectomy versus preoperative chemotherapy in the management of non-metastatic Wilms' tumour: Results of a randomised trial (UKW3) by the UK Children's Cancer Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2554–2562. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malogolowkin M, Spreafico F, Dome JS, van Tinteren H, Pritchard-Jones K, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Bergeron C, de Kraker J, Graf N, COG Renal Tumors Committee and the SIOP Renal Tumor Study Group Incidence and outcomes of patients with late recurrence of Wilms' tumor. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;6:1612–1615. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkatramani R, Chi YY, Coppes MJ, Malogolowkin M, Kalapurakal JA, Tian J, Dome JS. Outcome of patients with intracranial relapse enrolled on national Wilms tumor study group clinical trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017:64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26406. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark MB, Johnston RL, Inostroza-Ponta M, Fox AH, Fortini E, Moscato P, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Genome-wide analysis of long noncoding RNA stability. Genome Res. 2012;22:885–898. doi: 10.1101/gr.131037.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tani H, Imamachi N, Mizutani R, Imamura K, Kwon Y, Miyazaki S, Maekawa S, Suzuki Y, Akimitsu N. Genome-wide analysis of long noncoding RNA turnover. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1262:305–320. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2253-6_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter S. Long noncoding RNA: Novel links between gene expression and innate immunity. Virus Res. 2016;212:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li CH, Chen Y. Insight into the role of long noncoding RNA in cancer development and progression. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2016;326:33–65. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran VA, Perera RJ, Khalil AM. Emerging functional and mechanistic paradigms of mammalian long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6391–6400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong X, Chen R, Lin H, Lin T, Pan S. LncRNA BG981369 inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and promotes cell apoptosis by SRY-related high-mobility group box 4 (SOX4) signaling pathway in human gastric cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:718–726. doi: 10.12659/MSM.905965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lian Y, Xiao C, Yan C, Chen D, Huang Q, Fan Y, Li Z, Xu H. Knockdown of pseudogene derived from LncRNA DUXAP10 inhibits cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and promotes apoptosis in pancreatic cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:3671–3682. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin MT, Song HJ, Ding XY. Long non-coding RNAs involved in metastasis of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3724–3737. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i33.3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rönnau CG, Verhaegh GW, Luna-Velez MV, Schalken JA. Noncoding RNAs as novel biomarkers in prostate cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:591703. doi: 10.1155/2014/591703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu KR, Sun QF, Zhang YQ. Long non-coding RNA LINP1 induces tumorigenesis of Wilms' tumor by affecting Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:5691–5698. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201907_18306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Core Team, corp-author. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivera MN, Haber DA. Wilms' tumour: Connecting tumorigenesis and organ development in the kidney. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:699–712. doi: 10.1038/nrc1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton TE, Shamberger RC. Wilms tumor: Recent advances in clinical care and biology. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012;21:15–20. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irtan S, Ehrlich PF, Pritchard-Jones K. Wilms tumor: ‘State-of-the-art’ update, 2016. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2016;25:250–256. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakayama DK, Bonasso PC. The history of multimodal treatment of Wilms' tumor. Am Surg. 2016;82:487–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu S, Fu W, Zhang L, Fu K, Hu J, Jia W, Liu G. LINC00473 antagonizes the tumour suppressor miR-195 to mediate the pathogenesis of Wilms tumour via IKKα. Cell Prolif. 2018:51. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12416. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitra SA, Mitra AP, Triche TJ. A central role for long non-coding RNA in cancer. Front Genet. 2012;3:17. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prensner JR, Chinnaiyan AM. The emergence of lncRNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:391–407. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martens-Uzunova ES, Böttcher R, Croce CM, Jenster G, Visakorpi T, Calin GA. Long noncoding RNA in prostate, bladder, and kidney cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1140–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang M, Zhou L, Yu F, Zhang Y, Li P, Wang K. The functional roles of exosomal long non-coding RNAs in cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76:2059–2076. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03018-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Fatima Silva F, Ortiz-Silva M, Galia WBS, Cassolla P, de Silva FG, Graciano MFR, Carpinelli AR, de Souza HM. Effects of metformin on insulin resistance and metabolic disorders in tumor-bearing rats with advanced cachexia. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;96:498–505. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2017-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hage-Sleiman R, Herveau S, Matera EL, Laurier JF, Dumontet C. Tubulin binding cofactor C (TBCC) suppresses tumor growth and enhances chemosensitivity in human breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available in the TARGET repository, https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/target.