Abstract

Estrogen is an important sex steroid hormone which serves an important role in the regulation of a number of biological functions, including regulating bone density, brain function, cholesterol mobilization, electrolyte balance, skin physiology, the cardiovascular system, the central nervous system and female reproductive organs. Estrogen exhibits various functions through binding to its specific receptors, estrogen receptor α, estrogen receptor β and G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1. In recent years, researchers have demonstrated that estrogen and its receptors serve an important role in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and contribute to the progression of a number of GI diseases, including gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal cancer, peptic ulcers, gastric cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome and colon cancer. The aim of this review is to provide an overview of estrogen and its receptors in GI disease, and highlight potential avenues for the prevention and treatment of GI diseases.

Keywords: estrogen, estrogen receptors, estrogen receptor α, estrogen receptor β, G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1, gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophageal cancer, peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, colon cancer

1. Introduction

Estrogens, including estrone, estriol and the biologically active metabolite 17β-estradiol (E2), have long been considered important regulators of female reproductive functions and are primarily produced in the ovaries. In addition to the ovaries, several extragonadal tissues, such as the mesenchymal cells in the adipose tissue of the breast, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, aortic smooth muscle cells, vascular endothelium and numerous parts of the brain also produce estrogens (1). Estrogens have been demonstrated to serve functions outside of the female reproductive system, including in the cardiovascular system and the central nervous system, and function to regulate bone density, brain function, cholesterol mobilization and electrolyte balance (2,3). In contrast to women, men are largely dependent on the local synthesis of estrogens in extragonadal target tissues. This local production of estrogens encompasses the signaling modality from endocrine to paracrine, autocrine and intracrine signaling (4). Both estrogen and estrogen receptors have numerous effects on various organs and diseases specific to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. For example, estrogen and estrogen receptors have been demonstrated to serve pathophysiological roles in gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophageal cancer, peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer (5–7).

2. Estrogen receptor

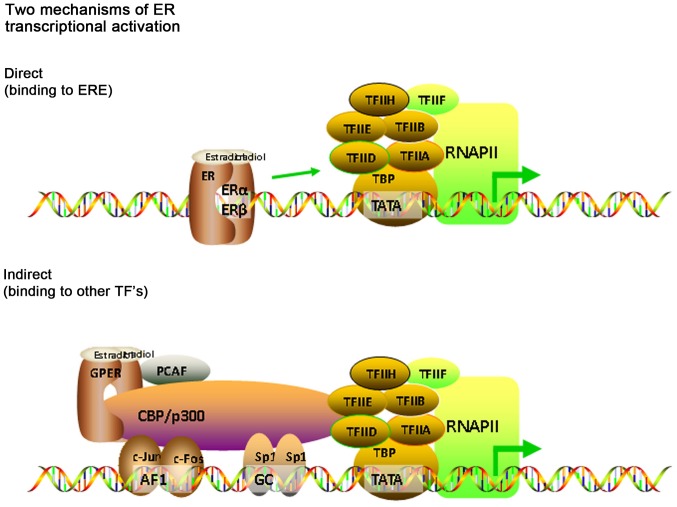

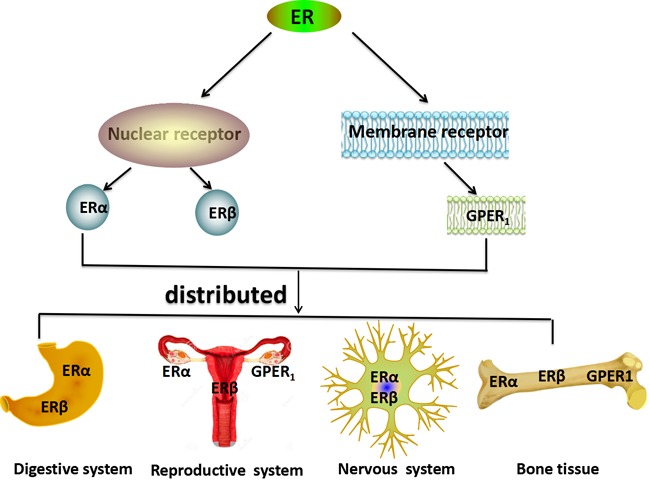

The estrogen receptor has three subtypes; estrogen receptor α (ERα), estrogen receptor β (ERβ), which belong to nuclear receptors and membrane receptors, such as G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1, also known as GPR30), which mediate all of estrogens effects, and the expression of each receptor is largely tissue-type specific (3) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of estrogen and ERs in the human body. ERs include two broad categories: Nuclear receptors, which includes ERα and ERβ and membrane receptors, which includes GPER1. ERα and ERβ are primarily expressed in the digestive system and the nervous system. ERβ, ERα and GPER1 are primarily expressed in bone tissue and the reproductive system. GPER1, G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1; ER, estrogen receptor.

ERα and ERβ have similar structures, and were respectively identified and cloned in 1986 and 1996 (8). Both ERα and ERβ have distinct cellular distributions and regulate separate sets of genes (9). ERα is encoded by estrogen receptor 1 which is located on chromosome 6q25.1, and ERβ is encoded by estrogen receptor 2 or estrogen receptor 2, which is located on chromosome 14q22-24 (10). ERα is primarily expressed in female sex organs, such as the breast, uterus and ovaries. ERα has three known isoforms; two shorter ERα isoforms which lack the N-terminal domain, and a full-length ERα isoform. The truncated isoforms can heterodimerize with the full-length ERα isoform and repress ERα activity. ERβ is expressed in different types of tissues and cells, and to a higher degree in females compared with males (11). ERβ has at least five different isoforms; four shorter ERβ isoforms and a full-length ERβ isoform. The four shorter ERβ isoforms exhibit reduced ligand binding activity (12). The ERβ isoforms are neither homodimerizable nor transcriptionally active (12). However, they can preferentially dimerize with ERα. The ERα and ERβ isoforms have different effects on estrogen signaling and target gene regulation (12) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

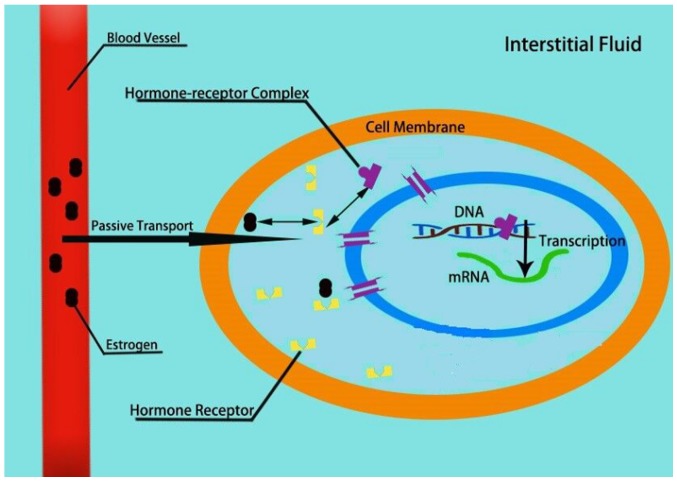

Mechanisms of estrogen signaling. Direct pathway: When estrogen binds to the nuclear receptor, it forms an estrogen-receptor complex, which changes the conformation of the receptor, forming a dipolymer and exposing the DNA binding region. The complex enters the nucleus through the nuclear pore in the form of a dipolymer. Activated ERα/β can directly combine with ERE and subsequently interacts with the target gene or with other transcription factors, forming a complex, which promotes activity of regulatory proteins located at the promoter sites of target genes. This results in an increase in the mRNA expression and thus potentially protein expression levels of the target gene. Indirect pathway: GPER is rapidly activated by intracellular PCAF combining with estrogen-like substances. Activated GPER directly associates with CBP/P300 and interacts with the target gene or with other transcription factors, forming complexes such as the proto-oncogene Fos/jun and SP-1, which promotes activity of regulatory proteins located at the promoter sites of target genes. ER, estrogen receptor; GPER, G protein-coupled estrogen receptor; CBP/P300, transcription complex auxiliary activation factor; PCAF, P300/CBP-related factors; ERE, estrogen response element.

GPER1 was first described in the 1990s (13) and it has been identified as one of the primary estrogen-sensitive receptors. Although GPER1 has a lower saturation, it possesses a high-affinity single binding site for estrogen, with a lower binding affinity for 17β-estradiol (14). The binding and decomposition of the receptor and its ligand are completed within a few minutes (15). GPER1 mediates estrogen-dependent rapid signaling events, independent of classical estrogen nuclear receptors (14). GPER1 activates multiple downstream signaling pathways, resulting in the activation of adenylate cyclase and increasing cyclic AMP levels, which promote intracellular calcium mobilization and synthesis of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate within the nucleus (16–18). GPER1 regulates a diverse range of biological processes, including bone and nervous system development, metabolism, cognition, male fertility and uterine function (19).

Although, ERα, ERβ and GPER1 possess a similar structure, they regulate divergent functions. In the present review, the role of estrogen and ERs in the physiology and pathology of the digestive system are explored.

3. Estrogen and estrogen receptor in gastrointestinal disease

Estrogen and estrogen receptors in esophageal diseases

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

GERD is a spectrum of reflux diseases of the gastroesophageal junction (20). GERD is a recurrent disease that has been defined in the Montreal Consensus Report as a chronic disease, in which the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus in abnormal quantities causes clinical symptoms with or without mucosal erosions (21). GERD is influenced by multiple factors, including age, sex, and obesity, esophageal function (esophageal dysmotility), anatomical abnormalities (gastroesophageal hernias), Helicobacter pylori infection and environmental factors (including diet) (22). Epidemiological studies have shown that reflux esophagitis is more prevalent in males (23). Kim et al (5) found that men are more likely to develop GERD compared with that in women, and the prevalence of GERD in women is significantly increased with age, particularly in women >50 years old. It indicates that the prevalence of GERD is closely associated with sex differences and highlighting the potential involvement of estrogen. Asanuma et al (24) showed that the severity and the prevalence of GERD appear to be closely related to the reproductive hormone status of women. In the postmenopausal period, the prevalence of GERD rapidly increased, whereas it was lower compared with that in men in the reproductive period, which could be responsible for the increased prevalence of GERD in younger men compared with that in women, which reflects the level of the sex hormone estrogen. This potential effect of estrogen could delay the development of GERD via its anti-inflammatory function and acquisition of epithelial resistance in the esophagus against causative refluxate. Thus demonstrating that estrogen in women could be responsible for GERD being more common in men compared with that in women. In addition, Iijima and Shimosegawa (25) demonstrated the role of estrogen in attenuating the esophageal tissue damage in NO-related esophageal damage. Furthermore this research could explain the well-recognized male predominance in the GERD spectrum in humans. Moreover, in female rats, estrogen binds the estrogen receptor and attenuates esophageal tissue damage (26). Masaka et al (26) reached a similar conclusion from an acid-related reflux esophagitis model that was produced by surgical operation on male and female rats. Boeckxstaens et al (27) demonstrated that the increased prevalence and severity of reflux esophagitis in women is associated with reduced levels of estrogen after menopause. Together, these studies highlight the sex differences in the severity of esophageal mucosa damage in GERD in animal models, highlighting the role of estrogen in controlling GERD with the relevant esophageal epithelial tissue injury.

However, contradictory studies have shown that estrogen and estrogen receptor agonists are associated with an increased risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms (28–31). Female sex hormones can relax the lower esophageal sphincter and increase the risk of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (32). Previously, it has been demonstrated that there is a positive correlation between gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (31).

Furthermore, women whom have never taken postmenopausal hormone therapies, have a lower risk of reflux symptoms compared with women who have or are still taking estrogen replacement therapy (28). There is a positive correlation between the risk of reflux symptoms, increased estrogen dose and increased duration of estrogen use. Jacobson et al (28) showed an odds ratio of 1.39 for reflux symptoms that used a selective estrogen receptor modulator, and an odds ratio of 1.37 for women who used over-the-counter hormone preparations (28). Therefore, it is important to understand the role of estrogen and estrogen receptors in the pathogenesis of GERD.

Esophageal cancer (EC)

EC is one of the deadliest malignancies of the GI tract and causes >400,000 deaths each year. The two most common histological subtypes are esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) (33). The incidence of EAC was 6–10× lower in women compared with men, and that ESCC incidence was 2–3× lower (34). Mathieu et al (35) analyzed the prevalence of EC by histology and gender differences between 1973 and 2008 in nine population-related cancer studies, and the incidence of EAC increased in both males and females over this time period. Furthermore, the ratio of EAC in male vs. female was highest in individuals aged 50–54. The risk of EAC age-based incidence rate in postmenopausal females aged 80 increased significantly, and this trend was not seen in similarly aged males. Overall, estrogen-related endocrine milieu in premenopausal and perimenopausal females serves as a protective factor in the prevention of EAC, and with loss of estrogen in the body or an increase in time without estrogen-mediated maintenance, the prevalence of EAC incidence increases in older postmenopausal females. A total of 16 independent studies were analyzed by Wang et al (36), and the results showed that estrogen can lower the risk of EC. The relative risks were pooled and they showed a negative correlation between the risk of EC and hormone replacement therapy. In addition, menopausal women were at an increased risk of EAC compared with EC (36). The serum levels of estradiol in a healthy cohort from a high-incidence area (HIA) and a low-incidence area for esophageal cancer, as well as that of patients with ESCC from a HIA in Hena, China were assessed, and it showed that lower serum levels of estradiol were associated with a higher predisposition for developing ESCC (37). Furthermore, Zhang et al (38) demonstrated that 17β-E2, but not 17α-E2, decreased proliferation of human ESCC cells in a dose-dependent manner, and this was attenuated by ICI1 82780 (an estrogen receptor antagonist). 17β-E2 promotes intracellular calcium mobilization and extracellular calcium entry into ESCC cells, and estrogen exerted an antiproliferative effect on human ESCC cells, likely through an estrogen receptor-calcium signaling pathway. According to Hennessy et al (39), the antiproliferative effects of 17β-E2 may occur through the ERβ estrogen receptor. Zuguchi et al (40) examined the expression status of both ERα and ERβ in 90 Japanese patients with ESCC and demonstrated that both ERα and ERβ were upregulated in ECGI-10 cells (an ESCC cell line). Additionally, the status of ERβ in ESCC was closely associated with unfavorable outcomes, possibly through increasing proliferation of carcinoma cells.

Taken together, these results indicate that estrogen and estrogen receptors inhibit growth of esophageal cancer by estradiol (41). Furthermore, estrogen replacement in postmenopausal women serves as a protective factor against esophageal cancer by reducing the degree of damage to esophageal tissues caused by gastric acid (42). Estrogen can reduce the risk of esophageal cancer. Therefore, a reduction or lack of estrogen may be an important factor in the high incidence of esophageal cancer in men and postmenopausal women.

Estrogen and estrogen receptors in gastric diseases

Peptic ulcers

Peptic ulcers include both gastric and duodenal ulcers, and complications include upper GI bleeding, GI perforation and gastric outlet obstruction (43). Peptic ulcer disease is a multifactorial and complex digestive disease, and its pathogenesis is unclear (44). Gastric protective factors include mucous, endogenous bicarbonate, prostaglandins and antioxidant agents; whereas, pepsin, gastric acid, bile acids and endogenous oxidant agents are recognized as risk factors that could cause damage to the stomach (45). Acid secretion, and the pH values of the stomach and duodenum did not differ between males and females (46). Peptic ulcers are relatively rare during pregnancy, and estrogen exhibits a protective effect against the incidence and severity of peptic ulcers, and the risk of ulcers is lower in women compared with men (6,47). Okada et al (48) found that individuals >70 years in age, had an increased prevalence of ulcers and this was also true in postmenopausal women. The decrease in the serum levels of estrogen induced a reduction in gastric mucosal defenses. Additionally, another study suggested that estrogen exerts an antioxidant effect, which directly scavenges free oxygen radicals, activates antioxidant enzymes, represses the production of superoxides and reduces the formation of peptic ulcers (49).

Therefore, estrogen exhibits a protective effect from peptic ulcers, which may be achieved through its antioxidant effects. However, the specific mechanisms underlying its protective effects require further study.

Gastric cancer (GC)

GC is a malignant tumor and the fifth highest incidence and third highest mortality rates in the world (50). Epidemiological studies have suggested that the prevalence of gastric cancer is higher in men than women with a ratio of 1.2:1.0 male:female. However, the differences between male and females becomes negligible when compared with postmenopausal women (51). Tokunaga et al (52) first reported the relationship between hormone receptors and GC, and they highlighted the fact that estrogens may serve a protective role against gastric cancer. Lindblad et al (53) found that the probability of developing gastric cancer was not increased in patients with prostate cancer. In addition, Furukawa et al (54) found that female, castrated male and estrogen-treated male rats had a lower incidence of gastric cancer with lower histological differentiation compared with that in non-treated male rats after administration of the carcinogen, N-methyl-N0-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine, and untreated male rats had increased rates of morbidity as a result of gastric cancer compared with castrated or estrogen-treated male rats.

The expression of ERα and ERβ in gastric cancer has been previously demonstrated (55). It has been hypothesized that ERs serve an important role in the occurrence and development of gastric cancer (56). Studies have demonstrated that ERβ, but not ERα, is abundantly expressed in GC (57–61). However, other researchers have demonstrated the expression of both receptors in GC (62–64). Zhou et al (65) found that the expression of β-catenin was reduced when ERα was overexpressed, and this resulted in a decrease in growth and proliferation of GC cells, and an increase in the apoptotic rate by preventing entry into the G1/G0 phase. ER-α is considered a rare subtype of estrogen receptor ERα, which is associated with increased lymph node metastasis and invasion in GC. Non-genomic estrogen signaling mediated by ER-α was involved in the c-Src signaling pathway in SGC7901 GC cells (66). A recent study found that ERα expression in gastric cancer cells was increased by low concentrations of 17β-estradiol, which in turn resulted in increased proliferation by activating mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway (67). In addition, knock down of ERα did not affect the proliferation, migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells (67). Compared with expression of ERα, expression of ERβ in noncancerous tissues was significantly higher in female rats compared with male rats (68). Ryu et al (61) evaluated the presence of ERβ in gastric cancer and showed that ERβ was likely not a contributing factor for the invasiveness of gastric cancer.

Therefore, investigating the roles and mechanisms of ER and its receptors may highlight potential mechanisms to improve management of the disease (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Estrogen and the estrogen receptor-mediated signaling pathway. Estrogen is transported into the cell and combines with the estrogen receptor, forming a hormone-receptor complex. The combined complex enters the nucleus, and regulates the transcription process as described in Fig. 2. Nuclear estrogen receptor is a transcription factor that regulates the function of estrogen complexes and can modulate gene expression by interacting with other proteins and receptors.

Estrogen and estrogen receptors in intestinal diseases

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Irritable bowel syndrome is one of the most common GI disorders, and is typically characterized by disorderly bowel movements and chronic abdominal pain (69). Based on epidemiological studies (70–72), irritable bowel syndrome is more prevalent in women than men, with a ratio range of 2–4:1, highlighting the possibility of the involvement of estrogen serving a role in the pathophysiology of IBS (7). IBS symptoms were determined to be associated with hormonal status, and the role of sex steroid hormones in the pathophysiology of IBS is gaining increasing attention (73). Studies have demonstrated that estrogen participates in modulating visceral sensitivity and regulating motor and sensory functions in IBS animal models (74,75). Additionally, Jacenik et al (76) determined the estrogen receptor engagement in the IBS subtypes, constipation predominant IBS and diarrhea predominant IBS (IBS-D). The authors analyzed whether estrogen signaling was accompanied by alterations in the expression of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and microRNAs, which regulate genes associated with the immune response. Both ERα and GPER expression were upregulated in IBS. There was a correlation between the expression of GPER in patients with IBS-D and the severity of abdominal pain, and an association between the GPER-mediated estrogenic effects on IBS pathogenesis and activation of mast cells in the colon, thus highlighting a novel avenue for understanding the pathogenesis of sex differences in IBS (77). GPER-mediated estrogenic effects were involved in the regulation of visceral pain and GI motility (78).

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

IBD is an intestinal inflammatory disease, which is incompletely understood. There is a lack of clear understanding of the pathogenesis of IBD and established effective treatments (79). Previously, patients with IBD were diagnosed primarily in North America and Europe (80). As lifestyle, environment and diets of individuals has changed overtime, the prevalence of IBD has increased worldwide, particularly in children and adult populations (81). IBD includes both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD). The differences in cancer risk between male and female mice were evaluated for patients with IBD, and the results showed that IBD conferred a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC) in males compared with females. Colitis is hypothesized to be associated with the development of IBD (82).

ERβ is the predominant ER subtype expressed in colon tissues, and it maintains a normal epithelial architecture protecting against chronic colitis (83–85). Men present with a higher risk of developing colitis than women, implicating estrogen as a protective factor against developing colitis. Armstrong et al (86) found that E2 treatment reduced inflammation in the colon in control mice. The expression of interleukins (ILs; particularly IL-6, IL-12 and IL-17), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interferon-γ, monocyte chemotactic proteins-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and tumor necrosis factor-α were not significantly increased in control mice following treatment with E2. The extent of damage was higher in the control ERβ knockout mice compared with the E2-treated ERβ knockout mice. Additionally, ERβ mRNA expression levels were decreased in a colitis mouse model of intestinal inflammation (87). ERβ knockout mice presented with colitis of increased severity compared with the wild-type group (88). Therefore, E2 may protect against acute colitis through the activation of ERβ.

Colon cancer

Colon cancer is one of the most common types of malignant tumor of the GI tract and the second leading cause of cancer-associated death worldwide. An epidemiological study of colon cancer prevalence found that females exhibited a higher prevalence of colon cancer. However, women aged 18–44 with colon cancer had an improved prognosis compared with men of the same age and women >50 years (89). Upregulated expression of ERβ1 in colon cancer is associated with an improved survival outcome (90). Similarly, downregulated expression of ERβ1 is associated with poorer survival outcome (90). Numerous studies have demonstrated that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in postmenopausal women did not serve a protective role (91,92), contradicting previous studies (93,94). The Women's Health Initiative showed that the prevalence of colon cancer decreased by 30% following treatment with HRT in postmenopausal women (95).

Interestingly, Bustos et al (89) found that estrogen receptors (ERα and GPER) are activated by 17β-E2 under anoxic conditions, when ERb expression was reduced/absent in patients with colon cancer. An E2-related gene (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) was inhibited in anoxic conditions through GPER signaling.

E2 treatment reinforced hypoxia-associated migration and proliferation of colon cancer cells, whereas in an aerobic environment, cell migration and proliferation were decreased by E2 treatment (89). The effects of E2 on the cellular responses in an aerobic environment and anoxic conditions were mediated by GPER. Therefore, in order to fully predict the estrogenic response in patients with colon cancer, it is necessary to understand not only the status of estrogen receptor expression in tumor cells, but also the aerobic/anoxic conditions of the local tumor microenvironment (89).

4. Conclusions

Estrogen is a sex hormone that regulates the development and function of the reproductive systems in all mammalian species, and increasing evidence demonstrates the multifaceted nature of its effects on non-reproductive organs during physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Understanding the effects of estrogen and estrogen receptor function may provide an important theoretical basis for improving clinical treatments of GI disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Biguang Tuo (Department of Gastroenterology, Affiliated Hospital to Zunyi Medical University) for suggestions for the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81660099 and 81770610).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to the present study, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Authors' contributions

CMC, XG, XXY, XHS, QD, QSL and RX conceived, wrote and revised the paper. YSC and JYX wrote and revised the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Simpson ER. Sources of estrogen and their importance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86:225–230. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guyton AC, Hall J. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. 2011:957–999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors: Therapies targeted to receptor subtypes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:44–55. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labrie F. Extragonadal synthesis of sex steroids: Intracrinology. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2003;64:95–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YS, Kim N, Kim GH. Sex and gender differences in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:575–588. doi: 10.5056/jnm16138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurt D, Saruhan BG, Kanay Z, Yokus B, Kanay BE, Unver O, Hatipoglu S. Effect of ovariectomy and female sex hormones administration upon gastric ulceration induced by cold and immobility restraint stress. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:1021–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meleine M, Matricon J. Gender-related differences in irritable bowel syndrome: Potential mechanisms of sex hormones. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6725–6743. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batistatou A, Stefanou D, Goussia A, Arkoumani E, Papavassiliou AG, Agnantis NJ. Estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) is expressed in brain astrocytic tumors and declines with dedifferentiation of the neoplasm. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:405–410. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Sukocheva OA, Hussey DJ, Watson DI. Estrogen, male dominance and esophageal adenocarcinoma: Is there a link? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:393–400. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i5.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K, Lagercrantz S, Lagercrantz J, Fried G, Nordenskjold M, Gustafsson JA. Human estrogen receptor beta-gene structure, chromosomal localization, and expression pattern. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4258–4265. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rochira V, Granata AR, Madeo B, Zirilli L, Rossi G, Carani C. Estrogens in males: What have we learned in the last 10 years? Asian J Androl. 2005;7:3–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2005.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heldring N, Pike A, Andersson S, Matthews J, Cheng G, Hartman J, Tujague M, Strom A, Treuter E, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors: How do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:905–931. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmeci C, Thompson DA, Ring HZ, Francke U, Weigel RJ. Identification of a gene (GPR30) with homology to the G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily associated with estrogen receptor expression in breast cancer. Genomics. 1997;45:607–617. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filardo EJ, Thomas P. Minireview: G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-1, GPER-1: Its mechanism of action and role in female reproductive cancer, renal and vascular physiology. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2953–2962. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanden C, Broselid S, Cornmark L, Andersson K, Daszkiewicz-Nilsson J, Martensson UE, Olde B, Leeb-Lundberg LM. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1/G protein-coupled receptor 30 localizes in the plasma membrane and traffics intracellularly on cytokeratin intermediate filaments. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:400–410. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.069500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton AR., Jr Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1649–1660. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.10.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307:1625–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:624–632. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma G, Prossnitz ER. G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) and sex-specific metabolic homeostasis. Adv Exp Med Boil. 2017;1043:427–453. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-70178-3_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Globale Konsensusgruppe The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A global, evidence-based consensus paper. Z Gastroenterol. 2007;45:1125–1140. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-963633. (Article in German) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katzka DA, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Phenotypes of gastroesophageal reflux disease: Where rome, lyon, and montreal meet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jul 15; doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.015. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nam SY, Choi IJ, Ryu KH, Park BJ, Kim YW, Kim HB, Kim JS. The effect of abdominal visceral fat, circulating inflammatory cytokines, and leptin levels on reflux esophagitis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21:247–254. doi: 10.5056/jnm14114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pohl H, Wrobel K, Bojarski C, Voderholzer W, Sonnenberg A, Rosch T, Baumgart DC. Risk factors in the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:200–207. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asanuma K, Iijima K, Shimosegawa T. Gender difference in gastro-esophageal reflux diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1800–1810. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i5.1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iijima K, Shimosegawa T. Involvement of luminal nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of the gastroesophageal reflux disease spectrum. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:898–905. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masaka T, Iijima K, Endo H, Asanuma K, Ara N, Ishiyama F, Asano N, Koike T, Imatani A, Shimosegawa T. Gender differences in oesophageal mucosal injury in a reflux oesophagitis model of rats. Gut. 2013;62:6–14. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boeckxstaens G, El-Serag HB, Smout AJ, Kahrilas PJ. Symptomatic reflux disease: The present, the past and the future. Gut. 2014;63:1185–1193. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson BC, Moy B, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS. Postmenopausal hormone use and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1798–1804. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS, Stremple J. Lower esophageal sphincter pressure in women using sequential oral contraceptives. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:232–234. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(76)80193-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilsson M, Lundegardh G, Carling L, Ye W, Lagergren J. Body mass and reflux oesophagitis: An oestrogen-dependent association? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:626–630. doi: 10.1080/00365520212502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Obesity and estrogen as risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. JAMA. 2003;290:66–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordenstedt H, Zheng Z, Cameron AJ, Ye W, Pedersen NL, Lagergren J. Postmenopausal hormone therapy as a risk factor for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms among female twins. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:921–928. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.el-Serag HB. The epidemic of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31(viii):421–440. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8553(02)00016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vizcaino AP, Moreno V, Lambert R, Parkin DM. Time trends incidence of both major histologic types of esophageal carcinomas in selected countries, 1973–1995. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:860–868. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathieu LN, Kanarek NF, Tsai HL, Rudin CM, Brock MV. Age and sex differences in the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma: Results from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) registry (1973–2008) Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:757–763. doi: 10.1111/dote.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang BJ, Zhang B, Yan SS, Li ZC, Jiang T, Hua CJ, Lu L, Liu XZ, Zhang DH, Zhang RS, Wang X. Hormonal and reproductive factors and risk of esophageal cancer in women: A meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:448–454. doi: 10.1111/dote.12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang QM, Qi YJ, Jiang Q, Ma YF, Wang LD. Relevance of serum estradiol and estrogen receptor beta expression from a high-incidence area for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in China. Med Oncol. 2011;28:188–193. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z, He Q, Fu S, Zheng Z. Estrogen receptors in regulating cell proliferation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Involvement of intracellular Ca(2+) signaling. Pathol Oncol Res. 2017;23:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s12253-016-0105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hennessy BA, Harvey BJ, Healy V. 17beta-Estradiol rapidly stimulates c-fos expression via the MAPK pathway in T84 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;229:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuguchi M, Miki Y, Onodera Y, Fujishima F, Takeyama D, Okamoto H, Miyata G, Sato A, Satomi S, Sasano H. Estrogen receptor α and β in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1348–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueo H, Matsuoka H, Sugimachi K, Kuwano H, Mori M, Akiyoshi T. Inhibitory effects of estrogen on the growth of a human esophageal carcinoma cell line. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7212–7215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Menon S, Nightingale P, Trudgill N. Is hormone replacement therapy in post-menopausal women associated with a reduced risk of oesophageal cancer? United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2:374–382. doi: 10.1177/2050640614543736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lanas A, Chan FKL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2017;390:613–624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32404-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanotra R, Ahmed M, Patel N, Thakkar B, Solanki S, Tareen S, Fasullo MJ, Kesavan M, Nalluri N, Khan A, et al. Seasonal variations and trends in hospitalization for peptic ulcer disease in the United States: A 12-year analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample. Cureus. 2016;8:e854. doi: 10.7759/cureus.854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suleyman H, Albayrak A, Bilici M, Cadirci E, Halici Z. Different mechanisms in formation and prevention of indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers. Inflammation. 2010;33:224–234. doi: 10.1007/s10753-009-9176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feldman M, Richardson CT, Walsh JH. Sex-related differences in gastrin release and parietal cell sensitivity to gastrin in healthy human beings. J Clin Invest. 1983;71:715–720. doi: 10.1172/JCI110818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sangma TK, Jain S, Mediratta PK. Effect of ovarian sex hormones on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastric lesions in female rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2014;46:113–116. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.125191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okada K, Inamori M, Imajyo K, Chiba H, Nonaka T, Shiba T, Sakaguchi T, Atsukawa K, Takahashi H, Hoshino E, Nakajima A. Gender differences of low-dose aspirin-associated gastroduodenal ulcer in Japanese patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1896–1900. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i15.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Speir E, Yu ZX, Takeda K, Ferrans VJ, Cannon RO., III Antioxidant effect of estrogen on cytomegalovirus-induced gene expression in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2000;102:2990–2996. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.24.2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang F, Shen X. Current prevalence status of gastric cancer and recent studies on the roles of circular RNAs and methods used to investigate circular RNAs. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2019;24:53. doi: 10.1186/s11658-019-0178-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung HW, Noh SH, Lim JB. Analysis of demographic characteristics in 3242 young age gastric cancer patients in Korea. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:256–263. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tokunaga A, Kojima N, Andoh T, Matsukura N, Yoshiyasu M, Tanaka N, Ohkawa K, Shirota A, Asano G, Hayashi K. Hormone receptors in gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1983;19:687–689. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(83)90186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindblad M, Ye W, Rubio C, Lagergren J. Estrogen and risk of gastric cancer: A protective effect in a nationwide cohort study of patients with prostate cancer in Sweden. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2203–2207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Furukawa H, Iwanaga T, Koyama H, Taniguchi H. Effect of sex hormones on the experimental induction of cancer in rat stomach-a preliminary study. Digestion. 1982;23:151–155. doi: 10.1159/000198722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim MJ, Cho SI, Lee KO, Han HJ, Song TJ, Park SH. Effects of 17β-estradiol and estrogen receptor antagonists on the proliferation of gastric cancer cell lines. J Gastric Cancer. 2013;13:172–178. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2013.13.3.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chandanos E, Lagergren J. Oestrogen and the enigmatic male predominance of gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2397–2403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sunakawa Y, Cao S, Berger MD, Matsusaka S, Yang D, Zhang W, Ning Y, Parekh A, Stremitzer S, Mendez A, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta genetic variations and overall survival in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. Pharmacogenomics J. 2017;17:36–41. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2015.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsuyama S, Ohkura Y, Eguchi H, Kobayashi Y, Akagi K, Uchida K, Nakachi K, Gustafsson JA, Hayashi S. Estrogen receptor beta is expressed in human stomach adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128:319–324. doi: 10.1007/s00432-002-0336-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takano N, Iizuka N, Hazama S, Yoshino S, Tangoku A, Oka M. Expression of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNAs in human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2002;176:129–135. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00739-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang M, Pan JY, Song GR, Chen HB, An LJ, Qu SX. Altered expression of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: Correlation with prothymosin alpha and clinicopathological parameters. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ryu WS, Kim JH, Jang YJ, Park SS, Um JW, Park SH, Kim SJ, Mok YJ, Kim CS. Expression of estrogen receptors in gastric cancer and their clinical significance. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:456–461. doi: 10.1002/jso.23097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qin J, Liu M, Ding Q, Ji X, Hao Y, Wu X, Xiong J. The direct effect of estrogen on cell viability and apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;395:99–107. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang BG, Du T, Zang MD, Chang Q, Fan ZY, Li JF, Yu BQ, Su LP, Li C, Yan C, et al. Androgen receptor promotes gastric cancer cell migration and invasion via AKT-phosphorylation dependent upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9. Oncotarget. 2014;5:10584–10595. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wesolowska M, Pawlik P, Jagodzinski PP. The clinicopathologic significance of estrogen receptors in human gastric carcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;83:314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou J, Teng R, Xu C, Wang Q, Guo J, Xu C, Li Z, Xie S, Shen J, Wang L. Overexpression of ERα inhibits proliferation and invasion of MKN28 gastric cancer cells by suppressing β-catenin. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:1622–1630. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X, Deng H, Zou F, Fu Z, Chen Y, Wang Z, Liu L. ER-α36-mediated gastric cancer cell proliferation via the c-Src pathway. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:329–335. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tang W, Liu R, Yan Y, Pan X, Wang M, Han X, Ren H, Zhang Z. Expression of estrogen receptors and androgen receptor and their clinical significance in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:40765–40777. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wakui S, Motohashi M, Muto T, Takahashi H, Hano H, Jutabha P, Anzai N, Wempe MF, Endou H. Sex-associated difference in estrogen receptor β expression in N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-induced gastric cancers in rats. Comp Med. 2011;61:412–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choung RS, Locke GR., III Epidemiology of IBS. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heitkemper M, Jarrett M, Bond EF, Chang L. Impact of sex and gender on irritable bowel syndrome. Biol Res Nurs. 2003;5:56–65. doi: 10.1177/1099800403005001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Longstreth GF, Wolde-Tsadik G. Irritable bowel-type symptoms in HMO examinees. Prevalence, demographics, and clinical correlates. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1581–1589. doi: 10.1007/BF01303163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Toner BB, Akman D. Gender role and irritable bowel syndrome: Literature review and hypothesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heitkemper MM, Chang L. Do fluctuations in ovarian hormones affect gastrointestinal symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome? Gender Med. 2009;2(Suppl 6):152–167. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chaloner A, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. Sexually dimorphic effects of unpredictable early life adversity on visceral pain behavior in a rodent model. J Pain. 2013;14:270–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cao DY, Ji Y, Tang B, Traub RJ. Estrogen receptor β activation is antinociceptive in a model of visceral pain in the rat. J Pain. 2012;13:685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jacenik D, Cygankiewicz AI, Fichna J, Mokrowiecka A, Malecka-Panas E, Krajewska WM. Estrogen signaling deregulation related with local immune response modulation in irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;471:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qin B, Dong L, Guo X, Jiang J, He Y, Wang X, Li L, Zhao J. Expression of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor in irritable bowel syndrome and its clinical significance. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:2238–2246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zielinska M, Fichna J, Bashashati M, Habibi S, Sibaev A, Timmermans JP, Storr M. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor and estrogen receptor ligands regulate colonic motility and visceral pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29 doi: 10.1111/nmo.13025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mizoguchi A, Takeuchi T, Himuro H, Okada T, Mizoguchi E. Genetically engineered mouse models for studying inflammatory bowel disease. J Pathol. 2016;238:205–219. doi: 10.1002/path.4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, Kaplan GG. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54.e42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cook LC, Hillhouse AE, Myles MH, Lubahn DB, Bryda EC, Davis JW, Franklin CL. The role of estrogen signaling in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease: A Helicobacter hepaticus model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barzi A, Lenz AM, Labonte MJ, Lenz HJ. Molecular pathways: Estrogen pathway in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5842–5848. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Principi M, Barone M, Pricci M, De Tullio N, Losurdo G, Ierardi E, Di Leo A. Ulcerative colitis: From inflammation to cancer. Do estrogen receptors have a role? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11496–11504. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pierdominici M, Maselli A, Varano B, Barbati C, Cesaro P, Spada C, Zullo A, Lorenzetti R, Rosati M, Rainaldi G, et al. Linking estrogen receptor β expression with inflammatory bowel disease activity. Oncotarget. 2015;6:40443–40451. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Armstrong CM, Allred KF, Weeks BR, Chapkin RS, Allred CD. Estradiol has differential effects on acute colonic inflammation in the presence and absence of estrogen receptor β expression. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1977–1984. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4631-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Looijer-van Langen M, Hotte N, Dieleman LA, Albert E, Mulder C, Madsen KL. Estrogen receptor-β signaling modulates epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G621–G626. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00274.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saleiro D, Murillo G, Benya RV, Bissonnette M, Hart J, Mehta RG. Estrogen receptor-β protects against colitis-associated neoplasia in mice. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2553–2561. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bustos V, Nolan AM, Nijhuis A, Harvey H, Parker A, Poulsom R, McBryan J, Thomas W, Silver A, Harvey BJ. GPER mediates differential effects of estrogen on colon cancer cell proliferation and migration under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Oncotarget. 2017;8:84258–84275. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Konstantinopoulos PA, Kominea A, Vandoros G, Sykiotis GP, Andricopoulos P, Varakis I, Sotiropoulou-Bonikou G, Papavassiliou AG. Oestrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) is abundantly expressed in normal colonic mucosa, but declines in colon adenocarcinoma paralleling the tumour's dedifferentiation. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Delellis Henderson K, Duan L, Sullivan-Halley J, Ma H, Clarke CA, Neuhausen SL, Templeman C, Bernstein L. Menopausal hormone therapy use and risk of invasive colon cancer: The california teachers study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:415–425. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Anderson G, Howard BV, Thomson CA, LaCroix AZ, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353–1368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women's Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Calle EE, Miracle-McMahill HL, Thun MJ, Heath CW., Jr Estrogen replacement therapy and risk of fatal colon cancer in a prospective cohort of postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:517–523. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.7.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Simon MS, Chlebowski RT, Wactawski-Wende J, Johnson KC, Muskovitz A, Kato I, Young A, Hubbell FA, Prentice RL. Estrogen plus progestin and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3983–3990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.7732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to the present study, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.