Key Points

Question

Is there an association between transplant center and the survival benefit associated with heart transplant in the United States?

Findings

In this registry-based observational study of 29 199 candidates for heart transplant in the United States, the 5-year survival benefit associated with heart transplant ranged from 30% to 55%. Estimated waiting list survival without transplant was significantly lower at centers with survival benefits significantly above the mean compared with those below the mean (29% at high survival benefit centers vs 39% at low survival benefit centers), but there was no significant difference in survival after the transplant (77.6% vs 77.1%, respectively).

Meaning

The 5-year survival benefit associated with heart transplant varied across transplant centers, and high survival benefit centers performed heart transplant for patients with lower estimated waiting list survival without transplant.

Abstract

Importance

In the United States, the number of deceased donor hearts available for transplant is limited. As a proxy for medical urgency, the US heart allocation system ranks heart transplant candidates largely according to the supportive therapy prescribed by transplant centers.

Objective

To determine if there is a significant association between transplant center and survival benefit in the US heart allocation system.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Observational study of 29 199 adult candidates for heart transplant listed on the national transplant registry from January 2006 through December 2015 with follow-up complete through August 2018.

Exposures

Transplant center.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The survival benefit associated with heart transplant as defined by the difference between survival after heart transplant and waiting list survival without transplant at 5 years. Each transplant center’s mean survival benefit was estimated using a mixed-effects proportional hazards model with transplant as a time-dependent covariate, adjusted for year of transplant, donor quality, ischemic time, and candidate status.

Results

Of 29 199 candidates (mean age, 52 years; 26% women) on the transplant waiting list at 113 centers, 19 815 (68%) underwent heart transplant. Among heart transplant recipients, 5389 (27%) died or underwent another transplant operation during the study period. Of the 9384 candidates who did not undergo heart transplant, 5669 (60%) died (2644 while on the waiting list and 3025 after being delisted). Estimated 5-year survival was 77% (interquartile range [IQR], 74% to 80%) among transplant recipients and 33% (IQR, 17% to 51%) among those who did not undergo heart transplant, which is a survival benefit of 44% (IQR, 27% to 59%). Survival benefit ranged from 30% to 55% across centers and 31 centers (27%) had significantly higher survival benefit than the mean and 30 centers (27%) had significantly lower survival benefit than the mean. Compared with low survival benefit centers, high survival benefit centers performed heart transplant for patients with lower estimated expected waiting list survival without transplant (29% at high survival benefit centers vs 39% at low survival benefit centers; survival difference, −10% [95% CI, −12% to −8.1%]), although the adjusted 5-year survival after transplant was not significantly different between high and low survival benefit centers (77.6% vs 77.1%, respectively; survival difference, 0.5% [95% CI, −1.3% to 2.3%]). Overall, for every 10% decrease in estimated transplant candidate waiting list survival at a given center, there was an increase of 6.2% (95% CI, 5.2% to 7.3%) in the 5-year survival benefit associated with heart transplant.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this registry-based study of US heart transplant candidates, transplant center was associated with the survival benefit of transplant. Although the adjusted 5-year survival after transplant was not significantly different between high and low survival benefit centers, compared with centers with survival benefit significantly below the mean, centers with survival benefit significantly above the mean performed heart transplant for recipients who had significantly lower estimated expected 5-year waiting list survival without transplant.

This study uses data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to investigate the association between transplant center and survival benefit among adult candidates for heart transplant adjusting for case mix and mortality estimates.

Introduction

Heart transplant remains the definitive treatment for end-stage heart failure. Demand greatly exceeds supply and the median waiting time is longer than 9 months.1 Federal regulations require the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) make the “best use” of donor hearts by ranking candidates from “most to least medically urgent.”2 Because a sufficiently accurate and objective physiological score has not been developed, the OPTN uses a status-based system that ranks candidates largely according to the supportive therapy prescribed by their transplant center.3 This therapy-based system uses treatment intensity as a surrogate for medical urgency, relying on centers to select candidates and use appropriate advanced therapies for heart failure.

In 2016, the OPTN thoracic committee identified “major problems” with the US heart allocation system.4 Driven by expanding use of high-dose inotrope and continuous-flow left ventricular assist device (LVAD) therapies,5,6 the majority of active adult heart transplant candidates were waiting at status 1A, which is a priority status intended for a small minority of the most critically ill candidates.1 In competitive organ markets, transplant centers more frequently use status 1A–qualifying high-dose inotropes and intra-aortic balloon pumps for candidates who are not in cardiogenic shock.7,8 In response, the OPTN updated the heart allocation system in October 2018, increasing the number of status levels from 3 to 6 and implementing a cardiogenic shock requirement to restrict access to the top priority status levels.9

Despite the major policy change, the association between transplant center candidate selection and management practices on the effectiveness of the original 3-tier heart allocation system has not been well studied. Furthermore, the potential benefits of the new 6-tier system have not been quantified. This registry cohort study estimated the survival benefit of heart transplant (defined as the difference between a patient’s expected survival with a transplant vs without a transplant) for each transplant center in the United States, comparing the 3-tier system with the new 6-tier allocation system of candidate rankings.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This study was a secondary analysis of deidentified data and was granted exemption status by the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division/University of Chicago Medical Center institutional review board to be performed without patient consent. This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR includes data submitted by OPTN on all (1) donors, (2) candidates who have been wait-listed, and (3) transplant recipients in the United States. The Health Resources and Services Administration, which is part of the US Department of Health and Human Services, oversees the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.

We identified all adult candidates (aged ≥18 years) for heart transplant only listed in the United States from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2015. This period follows the last major change in heart allocation policy10 and includes widespread use of modern continuous-flow LVAD implants.11 For each candidate, we constructed a time series with records for initial listing, changes in status or therapeutic support, transplant (if underwent a heart transplant), last follow-up visit, receipt of a second transplant, or death through August 2018. Death records were supplemented from the linked Social Security Death Master File to capture the outcomes of candidates who were delisted.

A second transplant operation was treated as a terminal event, which is standard practice when estimating the survival benefit of an organ transplant.12 Candidates were excluded if they had received multiple organ transplants, were listed at centers with less than 10 adult transplants during the entire study period, were never activated on the list for transplant, or had data-entry errors (included date of death or removal before listing date; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the Study Population and Outcomes.

Study follow-up extended until August 2018. Surviving patients in the cohort were followed up for a mean of 5.4 years before censoring. Of 5669 candidates who died without receiving a transplant, 2644 were on the waiting list and 3025 died after delisting. The deaths occurring after delisting were identified via linkage to the Social Security Death Master File.

aRefers to patients who were registered for heart transplant with an inactive status, but who were never converted to an active status (eg, 1A, 1B, or 2).

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was the survival benefit associated with heart transplant as quantified by the estimated improvement in absolute 5-year survival gained by undergoing heart transplant (described in detail below). Secondary outcomes were the characteristics of patients who received transplants at high vs low survival benefit centers, including status and the proportion of recipients treated with status 1A–qualifying intra-aortic balloon pumps or high-dose inotropes but who did not meet the hemodynamic requirements for cardiogenic shock. Additional secondary outcomes included age, sex, race, diagnosis, blood type, diabetes status, functional status measured using the Karnofsky Performance Scale,13 cardiac index, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, status 1A justification (acute mechanical circulatory support, mechanical circulatory support with complication, mechanical ventilation, high-dose inotropes and hemodynamic monitoring, or exception), and payer (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, or other).

Statistical Analysis

To estimate the primary outcome of survival benefit associated with heart transplant, we fit a mixed-effects Cox proportional hazard model with transplant treated as a time-dependent predictor variable.14,15,16,17 To allow candidate risk of mortality to vary by center both before and after transplant, the model used both a random intercept and a random transplant effect. Building on standard practices in hospital outcomes reporting,18,19 we generated case-mix, center-specific estimates of the 5-year survival benefit associated with heart transplant that were adjusted for candidate time-dependent status (1A, 1B, or 2), year of listing, and donor risk index (calculated using the method of Weiss et al20 and donor age, race, blood urea nitrogen level, creatinine level, and ischemic time [amount of time between donor heart procurement and the actual transplant]) to account for the significant variability in waiting time and donor quality across the country.1,6,21 Supplement 1 and Supplement 2 contain statistical analysis and coding information.

Fixed-category race variables (recorded by transplant providers in the SRTR data set) for candidates and donors were used in the study because racial mismatch is a known risk factor for posttransplant mortality.20 Because centers are responsible for listing candidates likely to experience a survival benefit from heart transplant and treating them with the appropriate supportive therapy, we deliberately chose not to add candidate covariates other than waiting list status into the model, instead allowing variation in candidate characteristics and pretransplant center treatment choices to be captured by the center random effects.

To identify centers with significantly higher or lower survival benefit associated with heart transplant, standard errors were calculated for each center estimate using the variance of the 5-year survival benefit distribution and the number of transplants performed at each center during the study period. A center with an estimate above or below the mean center at a P < .05 level was considered to have a significantly higher or lower survival benefit associated with transplant. To test for a violation of the proportional hazards assumption that could confound the association between center and survival benefit, we performed a Schoenfeld test on survival after transplant by center survival benefit level.

Secondary outcomes were described and compared between centers with significantly lower vs higher survival benefit. For continuous variables, means and SDs were calculated and the P values for group comparison testing were calculated using the t test. For categorical variables, numbers and percentages were calculated and the P values for group comparison testing were calculated using the Fisher exact test.

We also fit a second mixed-effects Cox model to estimate the between-center variation in survival benefit from heart transplant when using the 6-tier allocation system.3,9 The new 6-tier system splits status 1A–qualifying therapies into 3 groups (status 1, 2, or 3), distinguishes between severity of mechanical circulatory support complications, and imposes a recurrently verifiable cardiogenic shock requirement for a subset of candidates (eFigure 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 3).3 We coded each candidate according to the priority status he or she would have received under the current 6-tier system using each candidate’s most recent hemodynamic data for all time points after listing. Following previous approaches,7,22 we applied the cardiogenic shock requirement conservatively, assuming a patient met criteria for cardiogenic shock if hemodynamic data were missing. Absolute 5-year survival benefits were calculated using the same procedure described above.

Four sensitivity analyses were performed to test the underlying assumptions of our model. First, to test the assumption of gaussian random-center effects, we fit a fixed-effects model for which center waiting list and posttransplant risk were treated as fixed effects. Second, to ensure our modeling choices were not leading to confounding by temporal or donor factors, we fit a mixed-effects model with all donor variables (donor age, race, blood urea nitrogen level, creatinine level, and ischemic time in hours) modeled independently and using listing year instead of transplant year. Third, we added candidate demographic variables (age, sex, body mass index [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared], diagnosis, and blood type and cross-match requirement) to isolate the contribution of candidate demographic variation to the between-center variation in the survival benefit of transplant. Fourth, we added LVAD therapy as a bridge to transplant and United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) region to the model to quantify the contribution of variation in use of LVAD implants to the between-center variation in survival benefit.

A detailed description of the statistical analysis appears in the eMethods in Supplement 3. All statistical testing was 2-sided with a P value threshold of <.05. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for the secondary and other analyses should be interpreted as exploratory. All analyses were performed using R version 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Study Population

During 2006-2015, there were 30 899 adult candidates for heart transplant listed on the national registry in the United States. We excluded 970 adults for multiple organ transplant, 200 for being wait-listed at 1 of 33 low-volume centers, 393 who were never activated on the list, and 137 with data-entry errors (Figure 1). The remaining 29 199 candidates (mean age, 52 years; 26% women) were wait-listed at 113 centers and 19 815 (68%) underwent heart transplant (Table). Among transplant recipients, 5389 (27%) died or underwent a second transplant operation during the study period and 14 426 (73%) remained alive at last follow-up. Of the 9384 candidates who did not undergo heart transplant, 5669 (60%) died (2644 while on the waiting list and 3025 after being delisted) and 3715 (40%) were alive but had not undergone transplant by the end of follow-up. Surviving patients were followed up for a mean of 5.4 years before censoring.

Table. Characteristics of US Adult Heart Transplant Candidates Listed From 2006-2015.

| Overall (N = 29 199) | Heart Transplant (n = 19 815) | No Heart Transplant (n = 9384) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at listing, mean (SD), y | 52.38 (12.52) | 52.39 (12.49) | 52.35 (12.58) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)a | 27.56 (5.12) | 27.19 (4.99) | 28.35 (5.30) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 21 741 (74.5) | 14 795 (74.7) | 6946 (74.0) |

| Female | 7458 (25.5) | 5020 (25.3) | 2438 (26.0) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |||

| White | 19 555 (67.0) | 13 362 (67.4) | 6193 (66.0) |

| Black | 6247 (21.4) | 4046 (20.4) | 2201 (23.5) |

| Hispanic | 2251 (7.7) | 1562 (7.9) | 689 (7.3) |

| Otherb | 1146 (3.9) | 845 (4.3) | 301 (3.2) |

| Diagnosis, No. (%) | |||

| Dilated cardiomyopathy, nonischemic | 12 339 (42.3) | 8688 (43.8) | 3651 (38.9) |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 10 881 (37.3) | 7382 (37.3) | 3499 (37.3) |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy | 2773 (9.5) | 1866 (9.4) | 907 (9.7) |

| Other | 3206 (11.0) | 1879 (9.5) | 1327 (14.1) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 8392 (28.7) | 5442 (27.5) | 2950 (31.4) |

| Kidney function, No. (%)c | |||

| GFR of <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1456 (5.0) | 623 (3.1) | 833 (8.9) |

| GFR of ≥30 but <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 11 603 (39.7) | 7811 (39.4) | 3792 (40.4) |

| GFR of ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 16 010 (54.8) | 11 306 (57.1) | 4704 (50.1) |

| Unknown | 130 (0.4) | 75 (0.4) | 55 (0.6) |

| Functional status, No. (%)d | |||

| Limited impairment (10%-30%) | 9577 (32.8) | 6374 (32.2) | 3203 (34.1) |

| Moderate impairment (40%-60%) | 10 137 (34.7) | 7044 (35.5) | 3093 (33.0) |

| Severe impairment (70%-100%) | 8818 (30.2) | 5990 (30.2) | 2828 (30.1) |

| Unknown | 667 (2.3) | 407 (2.1) | 260 (2.8) |

| Blood type, No. (%) | |||

| A | 11 073 (37.9) | 8067 (40.7) | 3006 (32.0) |

| AB | 1345 (4.6) | 1098 (5.5) | 247 (2.6) |

| B | 3957 (13.6) | 2899 (14.6) | 1058 (11.3) |

| O | 12 824 (43.9) | 7751 (39.1) | 5073 (54.1) |

| Primary payer, No. (%) | |||

| Private insurance | 15 513 (53.1) | 10 798 (54.5) | 4715 (50.2) |

| Medicare | 8971 (30.7) | 5816 (29.4) | 3155 (33.6) |

| Medicaid | 3457 (11.8) | 2333 (11.8) | 1124 (12.0) |

| Other | 1258 (4.3) | 868 (4.4) | 390 (4.2) |

| Status (justification) at initial listing using 3-tier system, No. (%) | |||

| 1A (mechanical circulatory support for shock) | 3359 (11.5) | 2394 (12.1) | 965 (10.3) |

| 1A (mechanical circulatory support complication) | 571 (2.0) | 426 (2.1) | 145 (1.5) |

| 1A (mechanical ventilation) | 209 (0.7) | 92 (0.5) | 117 (1.2) |

| 1A (high-dose inotropes) | 2616 (9.0) | 2021 (10.2) | 595 (6.3) |

| 1A (exception) | 374 (1.3) | 275 (1.4) | 99 (1.0) |

| 1B (low-dose inotropes) | 8315 (28.5) | 6064 (30.6) | 2251 (24.0) |

| 1B (stable ventricular assist device) | 3474 (11.9) | 2428 (12.3) | 1046 (11.1) |

| 1B (exception) | 325 (1.1) | 236 (1.2) | 89 (0.9) |

| 2 | 9956 (34.1) | 5879 (29.7) | 4077 (43.4) |

| Had LVAD implant in place at listing, No. (%) | 6327 (21.7) | 4617 (23.3) | 1710 (18.2) |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 20.12 (8.77) | 20.19 (8.73) | 19.97 (8.85) |

| Pulmonary artery pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 29.98 (10.41) | 29.85 (10.17) | 30.27 (10.90) |

| Cardiac index, mean (SD), L/min/m2 | 2.17 (0.65) | 2.16 (0.65) | 2.20 (0.66) |

Abbreviations: GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Included American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander, Arab, Middle Eastern, Indian subcontinent, and multiracial.

Estimated using the revised Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.

Measured using the Karnofsky Performance Scale.

Between-Center Variation in the Survival Benefit Associated With Heart Transplant

Compared with being on the waiting list without transplant, heart transplant was associated with a mean hazard ratio (HR) for death of 0.24 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.14-0.35). This risk reduction generated a mean absolute improvement in 5-year survival of 44% (IQR, 27%-59%), increasing from 33% (IQR, 17%- 51%) for waiting list survival without transplant to 77% (IQR, 74%-80%) for those who underwent transplant (full model results appear in eTable 2 in Supplement 3).

Adjusted for status, risk of death for candidates on the waiting list without transplant varied by center from an HR of 0.71 to 1.63, relative to the mean center. The reduction in mortality risk after heart transplant also varied significantly (HR range, 0.71 to 1.68) and was relative to the mean survival benefit of the center (eFigure 2 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 3). In combination, these center effects led to wide variation in the case-mix–adjusted survival benefit associated with heart transplant; the mean improvement in estimated 5-year survival ranged from 30% to 55% by center (IQR, 40% to 47%; Figure 2 and eFigure 4 in Supplement 3). For every 10% decrease in estimated transplant candidate waiting list survival at a given center, there was an increase of 6.2% (95% CI, 5.2% to 7.3%) in 5-year survival benefit associated with heart transplant (Figure 3A). In contrast, there was no significant relationship between the mean survival duration after transplant and center survival benefit (an increase in survival benefit for every 10% increase in survival after transplant of 1.5% [95% CI, −3.8% to 0.83%]; Figure 3B).

Figure 2. Between-Center Variation in the Adjusted 5-Year Survival Benefit Associated With Heart Transplant.

Caterpillar plot (left) of estimates of each center’s mean absolute 5-year survival benefit, case-mix adjusted for time from listing to transplant, waiting list status, year of listing, donor quality, and ischemic time. The 95% CIs were constructed using the variance of the distribution of 5-year survival estimates for the entire study population and the number of transplants performed at each center during the study period. Compared with the mean center, 31 centers (27%) had significantly higher survival benefit (orange) and 30 centers (27%) had lower survival benefit (blue). The adjusted 5-year survival benefit varied substantially by center, ranging from 30% to 55%, median of 43% (interquartile range [IQR], 40%-47%) (box plot, right). In the box plot, the middle line represents the median, the hinges represent the upper and lower bounds of the IQR, the whiskers represent the smallest and largest observations within 1.5 times the IQR of the hinges, and the points represent outliers beyond the whisker range. The mean is represented by the white circle.

Figure 3. Relationship Between Candidate Survival on the Waiting List, Posttransplant Outcomes, and the Benefit of Heart Transplant for Each US Heart Transplant Center.

There was a significant association between the status-adjusted medical urgency of candidates listed by each center (as measured by the risk of death on the waiting list) and the benefit of transplant measured by 5-year survival benefit (panel A). For every 10% decrease in expected candidate waiting list survival, there was an increase of 6.2% (95% CI, 5.2% to 7.3%) in estimated survival benefit associated with heart transplant. In contrast, there was no significant association between survival after transplant and center survival benefit (survival difference, 1.5% [95% CI, −3.8% to 0.83%]) (panel B).

Medical Urgency of Transplant Recipients at High vs Low Survival Benefit Centers

Compared with the mean center, 31 centers (27.4%) had significantly higher survival benefit and 30 centers (26.5%) had significantly lower survival benefit. At 5 years, status-adjusted survival after transplant was not significantly different between high survival benefit centers and low survival benefit centers (77.6% vs 77.1%, respectively; survival difference, 0.5% [95% CI, −1.3% to 2.3%]) and the Schoenfeld test for the proportional hazards assumption violation was not significant (P = .45). Compared with low survival benefit centers, high survival benefit centers performed heart transplant for patients with lower estimated expected waiting list survival without transplant (29% at high survival benefit centers vs 39% at low survival benefit centers; survival difference, −10% [95% CI, −12% to −8.1%]), leading to an absolute improvement in survival benefit of 10.6% (48.6% vs 38%; survival difference, 10.6% [95% CI, 9.3% to 12%]).

High survival benefit centers used status 1A–qualifying therapies less frequently vs low survival benefit centers (50% vs 63% of recipients, respectively; difference, −13% [95% CI, −15% to −11%]; eTable 3 in Supplement 3). High survival benefit centers were less likely to perform heart transplant for patients who did not meet hemodynamic requirements for cardiogenic shock and were treated with status 1A–qualifying intra-aortic balloon pumps or high-dose inotropes vs low survival benefit centers (25% vs 31% of recipients, respectively; difference, −5.1% [95% CI, −7.2% to −3%]). At the time of transplant, status 1A recipients treated at high survival benefit centers had higher pulmonary capillary wedge pressures vs low survival benefit centers (mean, 20.1 mm Hg vs 18.9 mm Hg, respectively; difference in pressures, 1.2 mm Hg [95% CI, 0.7 to 1.6 mm Hg]; percentage who had pressure <15 mm Hg, 25% vs 32%; difference in prevalence, −7.1% [95% CI, −9.2% to −4.9%]) and worse functional status requiring continuous hospitalization (55% vs 42%; difference in prevalence, 13% [95% CI, 11% to 15%]; eTable 4 in Supplement 3).

High survival benefit centers performed heart transplant for more recipients with acute hemodynamic decompensation requiring mechanical support vs low survival benefit centers (38% vs 31%, respectively; difference, 7% [95% CI, 5% to 9%]) and used the device-related complication justification less often (20% vs 37%, respectively; difference, −17% [95% CI, −19% to −15%]). At high survival benefit centers, 35% of status 1A recipients had an LVAD implant at the time of heart transplant compared with 48% of recipients at low survival benefit centers (difference, −14% [95% CI, −16% to −12%]). Across all centers, transplant volume was weakly associated with survival after transplant (increase of 0.59% [95% CI, 0.074% to 1.1%] per 100 transplants); however, transplant volume was not associated with either candidate urgency (increase of 0.49% [95% CI, −0.29% to 1.3%] per 100 transplants) or survival benefit (increase of 0.099% [95% CI, −0.56% to 0.75%] per 100 transplants; eFigure 5 in Supplement 3).

Association of Status and Survival Benefit in 3-Tier vs 6-Tier Heart Allocation Systems

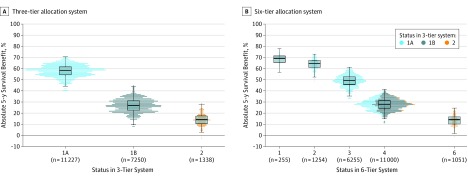

Under the prior 3-tier heart allocation system, the most common status at transplant was 1A (n = 11 227; 57%). A heart transplant for a status 1A candidate was associated with a mean 5-year survival benefit of 58% (IQR, 54%-62%). A heart transplant for a status 1B candidate, which was the next most common status (n = 7250; 37%), was associated with a mean 5-year survival benefit of 27% (IQR, 23%-31%). The least common was a status 2 candidate (n = 1338; 7%), and heart transplant was associated with a mean 5-year survival benefit of 14% (IQR, 10%-17%; Figure 4A). Overall, within a given priority status at transplant, the SD for the 5-year survival benefit associated with transplant was 5.5%; and the majority (76%) of variation among recipients was attributable to center-level effects and the remaining variation (24%) was attributable to transplant year, waiting time, donor quality, and ischemic time.

Figure 4. Distribution of 5-Year Survival Benefit Associated With Heart Transplant by Status for the 3-Tier and 6-Tier Heart Allocation Systems.

Dot and box plots of estimated 5-year survival benefit associated with heart transplant for adult recipients by status at transplant between 2006-2015. In the box plots, the middle line represents the median, the hinges represent the upper and lower bounds of the interquartile range (IQR), the whiskers represent the smallest and largest observations within 1.5 times the IQR of the hinges, and the points represent outliers beyond the whisker range. In A (distribution of 5-year survival benefit associated with heart transplant for the 3-tier system), there were 11 227 transplant recipients with status 1A and the median benefit from transplant was 59% (IQR, 54%-62%); 7250 transplant recipients with status 1B and the median benefit from transplant was 27% (IQR, 23%-31%); and 1338 transplant recipients with status 2 and the median benefit from transplant was 14% (IQR, 10%-17%). In B (distribution of 5-year survival benefit associated with heart transplant for the 6-tier system), there would have been 255 transplant recipients with status 1 and a median benefit from transplant of 69% (IQR, 65%-71%); 1254 transplant recipients with status 2 and a median benefit from transplant of 65% (IQR, 61%-67%); 6255 transplant recipients with status 3 and a median benefit from transplant of 49% (IQR, 46%-53%); 11 000 transplant recipients with status 4 and a median benefit from transplant of 28% (IQR, 24%-31%); and 1051 transplant recipients with status 6 and a median benefit from transplant of 14% (IQR, 10%-17%). Overall, within a given priority status, the SD for the 5-year survival benefit associated with transplant was 5.5%; and the majority (76%) of variation among recipients was attributable to center-level effects and the remaining variation (24%) was attributable to transplant year, waiting time, donor quality, and ischemic time. When reclassifying recipients from 2006-2015 based on the new 6-tier system, 6255 (56%) transplant recipients with status 1A in the 3-tier system met status 3 criteria; 1254 transplant recipients met status 2 criteria (11%); and 255 transplant recipients met status 1 criteria (2%). A total of 3462 (31%) transplant recipients with status 1A would have been downgraded to status 4 because of the cardiogenic shock requirement at the time of transplant. All 7250 transplant recipients with status 1B were reassigned to status 4. The 228 (22%) transplant recipients with status 2 in the 3-tier system (low priority) would have been assigned to the higher status of 4 because of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or amyloidosis. The transplant recipients are the same in both the 3-tier and 6-tier models; however, the increased number of tiers in the 6-tier model allows for wider variation in estimated survival benefits. Compared with the 3-tier system, the within-status SD for 5-year survival benefit associated with transplant decreased from 5.5% to 4.9%. The majority (66%) of within-status variation in survival benefit was still attributable to centers, and the remaining variation (34%) was attributable to transplant year, waiting time, donor quality, and ischemic time. Status 5 candidates (multiple organ transplant candidates) were excluded from the analysis.

When retrospectively reclassifying status 1A recipients from 2006-2015 based on new 6-tier allocation system, 6255 met status 3 criteria (56%), 1254 met status 2 criteria (11%), and 255 met status 1 criteria (2%). A total of 3462 (31%) transplant recipients with status 1A (using the 3-tier allocation system) would have been downgraded to status 4 because of not meeting the cardiogenic shock requirement at the time of transplant. All transplant recipients with status 1B (n = 7250) were reassigned to status 4. A total of 228 (22%) transplant recipients with status 2 (low priority) would have been assigned to the higher status category of 4 because of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or amyloidosis (eTable 5 in Supplement 3). The estimated 5-year survival benefit associated with heart transplant ranged from 68% (status 1) to 14% (status 6) (Figure 4B).

Compared with the 3-tier allocation system, the within-status SD for 5-year survival benefit associated with transplant decreased from 5.5% to 4.9%. The majority (66%) of within-status variation in survival benefit was still attributable to the centers. The between-center variance in the survival benefit associated with transplant on the log HR scale decreased from 0.161 to 0.115, corresponding to a reduction from 23% to 16% in the between-center variance of absolute 5-year survival benefit (eTable 6 in Supplement 3).

Sensitivity Analyses

The full results of the fixed-effects analysis appear in eTable 7 in Supplement 3. To achieve convergence, the model was constrained to centers with at least 20 observed deaths, which resulted in the exclusion of 9 centers and 260 patients. The distribution of center-specific survival benefit associated with transplant appeared roughly Gaussian (eFigure 6 in Supplement 3) and the Shapiro-Wilk test for nonnormality was not significant (P = .18). The Spearman correlation between random-effect and fixed-center estimates was very high (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.97; eFigure 7 in Supplement 3). In addition, there was a strong association between center waiting list risk and transplant survival benefit similar in magnitude to the random-effects model (eFigure 8 in Supplement 3).

In the model containing expanded donor factors and listing year, the between-center variance in survival benefit associated with transplant was 0.15 on the log HR scale compared with 0.16 in the original 3-tier allocation model (eTable 8 in Supplement 3). In the model containing expanded donor factors, listing year, and candidate demographic variables, the between-center variance in the survival benefit of transplant was 0.14 on the log HR scale (eTable 9 in Supplement 3).

In the model including use of an LVAD implant and UNOS region vs no LVAD implant, the presence of an LVAD implant was associated with lower risk of death for candidates on the waiting list without transplant (log HR for LVAD implant vs no LVAD implant, −0.49 [95% CI, −0.55 to −0.42]) and lower survival benefit associated with heart transplant (log HR for heart transplant × LVAD implant interaction, 0.68 [95% CI, 0.59 to 0.77]; eTable 10 in Supplement 3). In contrast, no UNOS region had a significantly different survival benefit from the mean. The between-center variance in the survival benefit associated with transplant was 0.12 on the log HR scale compared with 0.16 in the original model.

Discussion

In this registry cohort study of 29 199 adult heart transplant candidates, wide between-center variability was observed in the survival benefit associated with heart transplant. High survival benefit centers had an estimated absolute 5-year survival benefit that was 10.6% higher than low survival benefit centers by achieving good posttransplant outcomes for patients with lower cardiac indices, higher pulmonary capillary wedge pressures, worse functional status, and lower estimated candidate waiting list 5-year survival. The new 6-tier allocation system was associated with less variation in survival benefit across centers.

Previous estimates of heart transplant survival benefit12,23,24 have not considered transplant candidate listing and the management practices of individual transplant centers, implicitly assuming that candidates are the same at each center and receive equivalent survival benefit from transplant. The novel mixed-effects approach identified a large group of low survival benefit centers that prioritized less medically urgent candidates who had a lower risk of death without transplant and less potential survival benefit than the statistical mean recipient. The specific management practices these centers use support the explanation that these centers are more likely to select stable candidates and escalate supportive therapies as needed to achieve status 1A. Low survival benefit centers frequently treated candidates with high-dose inotropes and intra-aortic balloon pumps despite the absence of cardiogenic shock. Low survival benefit centers also used the device-related complication indication for candidates with LVAD implants (who have low medical urgency without transplant25). These results suggest that the between-center practice variation in the 3-tier allocation system may not have been consistent with the final rule requirement2 to “avoid grouping together patients with substantially different medical urgency.”

The study results also suggest that the priority reassignments in the new 6-tier allocation system may reduce the variability in survival benefit, potentially through the limited incorporation of objective medical acuity criteria and disease-specific status adjustments. There were relatively few candidates who would have been assigned to the top status of 1 or 2, which theoretically would alleviate waiting times for the most medically urgent heart transplant candidates. However, there are reasons the new system may not produce dramatic improvements. There was still significant within-status variation in survival benefit attributable to center practices, implying the 6-tier allocation system still does not meet guidelines2 that call for “a sufficient number of categories … to avoid grouping together patients with substantially different medical urgency.”

Furthermore, even this limited improvement in status categorization is contingent on consistent use by transplant centers of current advanced heart failure therapies. After the last major heart allocation policy change in 2006, there were major national and regional shifts in transplant center practices attributed to increased competition for donor hearts and new technology.5,10,26 If one applies the new cardiogenic shock criteria conservatively in the 6-tier allocation system, one-third of status 1A recipients would not qualify for status 1, 2, or 3. The cardiogenic shock criterion will increase heart allocation to those with the most urgent need only if these more stable candidates are actually listed at the lower status 4 designation. Adding more tiers and complexity to the therapy-based system may simply create more loopholes and inefficiencies.

In other organ allocation systems, the final rule requirements have been met with the implementation of scores based on objective clinical measurements. For liver transplant, transitioning from a therapy-based system to the model for end-stage liver disease system eliminated unnecessary intensive care unit stays27 and allowed identification and transplant for the sickest candidates based on objective medical criteria,28 likely saving thousands of lives since its implementation in 2002. Whether the new 6-tier system properly allocates organs in the current era of highly effective LVAD implant devices as a bridge or alternative to heart transplant29,30 remains to be determined.

In addition, it is appropriate for an allocation system to incentivize programs to list and perform transplants for candidates whom the system predicts will have good posttransplant outcomes. The finding that posttransplant outcomes were not significantly different between high and low survival benefit centers could be interpreted to mean that regulation of these end points by the OPTN and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services31,32 has been successful.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, increased candidate waiting list mortality risk at a center may be reflective of suboptimal care management prior to transplant rather than the severity of illness within the center’s population. However, this is unlikely because high survival benefit centers performed heart transplant for recipients with objectively worse physiological data at the time of transplant. Furthermore, high survival benefit centers had no significant difference in outcomes after transplant compared with low survival benefit centers despite the worse clinical and physiological profiles of candidates at time of transplant, suggesting the medical care of the transplant recipient at high survival benefit centers is not significantly below average.

Second, the benefit associated with heart transplant extends beyond a 5-year survival improvement. Five-year survival benefit was chosen because of the duration of follow-up available for the candidates listed during the study period and the restrictions of the semiparametric Cox proportional hazards model approach for survival. Different time frames or survival benefit HRs relative to the mean center may be more appropriate for use in the actual regulation of transplant programs.

Third, the efforts to adjust each center’s survival benefit estimate may be inadequate, potentially biasing the results of individual centers. Specifically, the models may not be fully capturing donor quality because the donor risk index has limited accuracy20 or lacks complete accounting for the temporal effects of changing technologies and treatments. However, the sensitivity analysis performed with individual donor factors and a more granular listing year variable had similar between-center variation for survival benefit with transplant (eTable 8 in Supplement 3), suggesting these factors are not significantly confounding the results of the principal analysis.

Fourth, the between-center variation in survival benefit observed in this study may be attributable more to geographic variation in candidate demographics, rather than center selection and treatment practices. However, the minimal reduction in the between-center variation in survival benefit observed after the inclusion of several important demographic variables (eTable 9 in Supplement 3) suggests that the results cannot be attributed simply to variability in potential heart transplant candidates across the country.

Fifth, support with LVAD implants was associated with lower estimated waiting list mortality and lower survival benefit from heart transplant (eTable 10 in Supplement 3). This finding is consistent with the low waiting list mortality risk for candidates with LVAD implants observed in the French national transplant registry.33

These results suggest that, along with practices like the use of high-dose inotropes and intra-aortic balloon pumps in candidates without cardiogenic shock, between-center variation in the use of LVAD implants may explain part of the association between transplant center and survival benefit. The allocation system may have to be altered to properly account for LVAD implant support and to maximize the survival benefit gains from heart transplant.

Conclusions

In this registry-based study of US heart transplant candidates, transplant center was associated with the survival benefit of transplant. Although the adjusted 5-year survival after transplant was not significantly different between high and low survival benefit centers, compared with centers with survival benefit significantly below the mean, centers with survival benefit significantly above the mean performed heart transplant for recipients who had significantly lower estimated expected 5-year waiting list survival without transplant.

Data preparation

Model fitting and analysis

eMethods

eFigure 1. Details of prior and current heart allocation system

eFigure 2. Center-specific survival benefit framework

eFigure 3. Smoothed baseline hazard function from time of listing

eFigure 4. Distribution of five-year survival benefit at the highest and lowest benefit center, 2006-2015

eFigure 5. Association of center transplant volume with wait-list survival, post-transplant survival, and survival benefit from heart transplantation

eFigure 6. Histogram of center-specific survival benefits of heart transplantation as estimated by a fixed-effects model

eFigure 7. Relationship between fixed-effect and random-effect center estimates of survival benefit from heart transplantation

eFigure 8. Association of center waitlist risk with survival benefit from transplantation in fixed-effects model

eTable 1. Detailed cardiogenic shock requirements for intra-aortic balloon pumps and multiple inotropes or a single high dose inotrope and hemodynamic monitoring

eTable 2. Three-status model results

eTable 3. Status at heart transplantation by center level of benefit

eTable 4. Status 1A candidate characteristics at time of transplant by center benefit

eTable 5. Classification of heart transplant recipients from 2006-2015 based on the new status 1-6 system

eTable 6. Six-status model results

eTable 7. Fixed-effects model results

eTable 8. Three-status + expanded donor factors and listing year

eTable 9. Three-status + expanded donor factors and listing year + candidate variables model results

eTable 10. Three-status + LVAD + UNOS region results

eReferences

References

- 1.Colvin M, Smith JM, Hadley N, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2016 annual data report: heart. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(suppl 1):291-362. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Electronic Code of Federal Regulations Title 42: public health. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/ECFR?page=browse. Accessed December 23, 2015.

- 3.US Dept of Health and Human Services; Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Policies. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/policies/. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- 4.US Dept of Health and Human Services; Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Proposal to modify the adult heart allocation system. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2006/thoracic_brief_201612.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2016.

- 5.Parker WF, Garrity ER Jr, Fedson S, Churpek MM. Trends in the use of inotropes to list adult heart transplant candidates at status 1A. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(12):e004483. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dardas T, Mokadam NA, Pagani F, Aaronson K, Levy WC. Transplant registrants with implanted left ventricular assist devices have insufficient risk to justify elective organ procurement and transplantation network status 1A time. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(1):36-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker WF, Anderson AS, Hedeker D, et al. Geographic variation in the treatment of US adult heart transplant candidates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1715-1725. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Dept of Health and Human Services; Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network White paper on manipulating waitlist priority. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/public-comment/white-paper-on-manipulating-waitlist-priority/. Accessed February 1, 2018.

- 9.US Dept of Health and Human Services; Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Modify adult heart allocation: 2nd round. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/public-comment/modify-adult-heart-allocation-2016-2nd-round/. Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 10.Schulze PC, Kitada S, Clerkin K, Jin Z, Mancini DM. Regional differences in recipient waitlist time and pre- and post-transplant mortality after the 2006 United Network for Organ Sharing policy changes in the donor heart allocation algorithm. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(2):166-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, et al. ; HeartMate II Investigators . Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(23):2241-2251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnitzler MA, Whiting JF, Brennan DC, et al. The life-years saved by a deceased organ donor. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(9):2289-2296. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karnofsky D, Burchenal J. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer In: MacLeod CM, ed. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1949:196. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ripatti S, Palmgren J. Estimation of multivariate frailty models using penalized partial likelihood. Biometrics. 2000;56(4):1016-1022. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.01016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin PC. A tutorial on multilevel survival analysis: methods, models and applications. Int Stat Rev. 2017;85(2):185-203. doi: 10.1111/insr.12214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM, Pankratz VS. Penalized survival models and frailty. J Comput Graph Stat. 2003;12(1):156-175. doi: 10.1198/1061860031365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Therneau TM. Coxme: mixed effects Cox models. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=coxme. Accessed September 26, 2018.

- 18.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Keenan PS, et al. Relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(6):587-593. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahian DM, Torchiana DF, Shemin RJ, Rawn JD, Normand S-LT. Massachusetts cardiac surgery report card: implications of statistical methodology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(6):2106-2113. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.06.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss ES, Allen JG, Kilic A, et al. Development of a quantitative donor risk index to predict short-term mortality in orthotopic heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(3):266-273. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dardas TF, Kim M, Bansal A, et al. Agreement between risk and priority for heart transplant: effects of the geographic allocation rule and status assignment. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36(6):666-672. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker WF, Garrity ER Jr, Fedson S, Churpek MM. Potential impact of a shock requirement on adult heart allocation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36(9):1013-1016. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh TP, Milliren CE, Almond CS, Graham D. Survival benefit from transplantation in patients listed for heart transplantation in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(12):1169-1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smits JM, de Vries E, De Pauw M, et al. Is it time for a cardiac allocation score? first results from the Eurotransplant pilot study on a survival benefit-based heart allocation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(9):873-880. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wever-Pinzon O, Drakos SG, Kfoury AG, et al. Morbidity and mortality in heart transplant candidates supported with mechanical circulatory support: is reappraisal of the current United network for organ sharing thoracic organ allocation policy justified? Circulation. 2013;127(4):452-462. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.100123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nativi JN, Kfoury AG, Myrick C, et al. Effects of the 2006 US thoracic organ allocation change: analysis of local impact on organ procurement and heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(3):235-239. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snyder J. Gaming the liver transplant market. J Law Econ Organ. 2010;26(3):546-568. doi: 10.1093/jleo/ewq003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merion RM, Schaubel DE, Dykstra DM, Freeman RB, Port FK, Wolfe RA. The survival benefit of liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(2):307-313. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krim SR, Vivo RP, Campbell P, et al. Regional differences in use and outcomes of left ventricular assist devices: insights from the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34(7):912-920. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Truby LK, Garan AR, Givens RC, et al. Ventricular assist device utilization in heart transplant candidates: nationwide variability and impact on waitlist outcomes. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(4):e004586. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare C for Baltimore, Maryland: transplant laws and regulations. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/GuidanceforLawsAndRegulations/Transplant-Laws-and-Regulations.html. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS Medicare program; hospital conditions of participation: requirements for approval and re-approval of transplant centers to perform organ transplants: final rule. Fed Regist. 2007;72(61):15197-15280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jasseron C, Legeai C, Jacquelinet C, et al. Prediction of waitlist mortality in adult heart transplant candidates: the candidate risk score. Transplantation. 2017;101(9):2175-2182. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data preparation

Model fitting and analysis

eMethods

eFigure 1. Details of prior and current heart allocation system

eFigure 2. Center-specific survival benefit framework

eFigure 3. Smoothed baseline hazard function from time of listing

eFigure 4. Distribution of five-year survival benefit at the highest and lowest benefit center, 2006-2015

eFigure 5. Association of center transplant volume with wait-list survival, post-transplant survival, and survival benefit from heart transplantation

eFigure 6. Histogram of center-specific survival benefits of heart transplantation as estimated by a fixed-effects model

eFigure 7. Relationship between fixed-effect and random-effect center estimates of survival benefit from heart transplantation

eFigure 8. Association of center waitlist risk with survival benefit from transplantation in fixed-effects model

eTable 1. Detailed cardiogenic shock requirements for intra-aortic balloon pumps and multiple inotropes or a single high dose inotrope and hemodynamic monitoring

eTable 2. Three-status model results

eTable 3. Status at heart transplantation by center level of benefit

eTable 4. Status 1A candidate characteristics at time of transplant by center benefit

eTable 5. Classification of heart transplant recipients from 2006-2015 based on the new status 1-6 system

eTable 6. Six-status model results

eTable 7. Fixed-effects model results

eTable 8. Three-status + expanded donor factors and listing year

eTable 9. Three-status + expanded donor factors and listing year + candidate variables model results

eTable 10. Three-status + LVAD + UNOS region results

eReferences