Abstract

Extraversion is a fundamental personality dimension closely related to an individual's life outcomes and mental health. Although an increasing number of studies have attempted to identify the neurostructural markers of extraversion, the results have been highly inconsistent. The current study aimed to achieve a comprehensive understanding of brain gray matter (GM) correlates of extraversion with a systematic review and meta‐analysis approach. Our review showed relatively high interstudy heterogeneity among previous findings. Our meta‐analysis of whole‐brain voxel‐based morphometry studies revealed that extraversion was stably associated with six core brain regions. Additionally, meta‐regression analyses identified brain regions where the associations of extraversion with GM volume were modulated by gender and age. The relationships between extraversion and GM structures were discussed based on three extraversion‐related functional systems. Furthermore, we explained the gender and age effects. Overall, our study is the first to reveal a comprehensive picture of brain GM correlates of extraversion, and the findings may be useful for the selection of targeted brain areas for extraversion interventions.

Keywords: extraversion, meta‐analysis, structural magnetic resonance imaging, systematic review, voxel‐based morphometry

1. INTRODUCTION

Extraversion is one of the fundamental dimensions of personality. As a stable and heritable higher order individual trait (van den Berg et al., 2016), extraversion is considered a core independent aspect of virtually all personality theories (Cattell, Eber, & Tatsuoka, 1970; Cloninger, Przybeck, & Svrakic, 1991; Depue & Collins, 1999; Eysenck, 1967; Goldberg, 1990; Gray, 1970; Tellegen, 1982) and has multiple related measurements. For instance, the most common assessments of extraversion are the Revised NEO Personality Inventory and the NEO Five‐Factor Inventory, two measures of the currently dominant Big Five factor model (Costa & McCrae, 1992a, 1992b). Another popular assessment of extraversion is the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, which was developed in Eysenck's three‐factor model (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975). The Behavioral Approach System Scale (Carver & White, 1994; Cooper, Gomez, & Aucote, 2007), Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (Cattell et al., 1970), and Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) (Tellegen & Waller, 2008) and its brief form (MPQ‐BF) (Patrick, Curtin, & Tellegen, 2002) are also used to measure extraversion.

The characteristics of extraversion include interpersonal engagement, activation, sensation seeking, and positive affections (Depue & Collins, 1999). Extraverts are generally described as cheerful, optimistic, enthusiastic, gregarious, sociable, ambitious, energetic, talkative, assertive, adventurous, and sensation seeking; in contrast, introverts are usually described as joyless, pessimistic, inhospitable, unsociable, bashful, lethargic, quiet, untalkative, and conservative (Depue & Collins, 1999; Goldberg, 1990). Numerous studies have commonly and reliably shown that extraversion plays an important role in an individual's life outcomes and mental health (Costa & McCrae, 1992a; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Ozer & Benet‐Martinez, 2006). For example, individuals with higher extraversion have been shown to have increased subjective well‐being (Costa & McCrae, 1980; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998), higher life satisfaction (Huebner, 1991; Schimmack, Oishi, Furr, & Funder, 2004), better social interaction (Berry & Hansen, 1996; Lopes, Salovey, Côté, Beers, & Petty, 2005), and a longer lifespan (Masui, Gondo, Inagaki, & Hirose, 2006; Terracciano, Löckenhoff, Zonderman, Ferrucci, & Costa, 2008). In contrast, individuals with lower extraversion are more likely to be susceptible to loneliness (Cheng & Furnham, 2002; Kong et al., 2015), interpersonal chronic life stress (Uliaszek et al., 2010), social anxiety (Naragon‐Gainey, Watson, & Markon, 2009), depression (Jylhä & Isometsä, 2006; Naragon‐Gainey et al., 2009), and internet addiction (Huang et al., 2010). Given the crucial role of extraversion in individuals' developmental outcomes and psychological health, identifying the neural markers underlying extraversion is extremely important, as the findings may be used by clinical and educational experts to develop corresponding intervention programs (e.g., neurofeedback training, Sitaram et al., 2017) to improve a person's quality of life.

With the rapid development of personality neuroscience over the past decade, an increasing number of neuroimaging studies have been conducted to uncover how extraversion may be related to individual differences in brain structure (DeYoung, 2010; DeYoung et al., 2010; DeYoung & Gray, 2009; Yarkoni, 2015). On the one hand, a large number of studies have used structural magnetic resonance imaging (S‐MRI) to investigate associations between extraversion and gray matter (GM) structures, including GM volume (GMV), cortical thickness (CT), cortical surface area (CSA), and cortical folding (CF) (e.g., Bjornebekk et al., 2013; Coutinho, Sampaio, Ferreira, Soares, & Goncalves, 2013; Cremers et al., 2011; Forsman, de Manzano, Karabanov, Madison, & Ullen, 2012; Grodin & White, 2015; Lu et al., 2014; Nostro, Muller, Reid, & Eickhoff, 2017; Omura, Todd Constable, & Canli, 2005; Privado, Roman, Saenz‐Urturi, Burgaleta, & Colom, 2017; Riccelli, Toschi, Nigro, Terracciano, & Passamonti, 2017; Wright et al., 2006; Wright, Feczko, Dickerson, & Williams, 2007). On the other hand, several investigations based on diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) have explored the white matter (WM) substrates of extraversion (Booth et al., 2014; Gurrera et al., 2007; McIntosh et al., 2013; Pang et al., 2018; Privado et al., 2017; Xu & Potenza, 2012). However, the findings are fairly inconsistent across studies. For instance, Coutinho et al. (2013) and Grodin and White (2015) both found a significant association between extraversion and GMV in the bilateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), but their results presented effects in the opposite directions. Moreover, while one study identified a negative association between extraversion and the bilateral amygdala volume (Lu et al., 2014), another study detected a positive association only in the right dorsal amygdala (Cremers et al., 2011). These inconsistent findings may be due to factors such as heterogeneity of sample characteristics and personality measurements and differences in statistical and methodological models (Hu et al., 2011; Nostro et al., 2017; Pell et al., 2008; Pereira, Nestor, & Williams, 2008). Therefore, a systematic review and analysis of previous findings are urgently needed to obtain a comprehensive and deep understanding of the structural brain basis underlying extraversion.

In the current systematic review and meta‐analysis, we focused on brain GM findings since WM findings are still limited. Additionally, only GM findings in healthy people were included since significant behavioral and brain morphometric differences exist between patients and healthy people. First, we performed a systematic review to summarize and categorize the results of brain GM correlates of extraversion. Then, we conducted an anisotropic effect‐size seed‐based d mapping (AES‐SDM) meta‐analysis to identify the stable and unbiased brain regions whose GM structures are significantly associated with extraversion. AES‐SDM is a helpful whole‐brain meta‐analytic method (Radua et al., 2012; Radua & Mataix‐Cols, 2009) that is widely used in neuroimaging meta‐analyses of patients (e.g., Pan et al., 2017; Radua & Mataix‐Cols, 2009; Yang et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2017) and healthy people (e.g., Han, Boachie, Garcia‐Garcia, Michaud, & Dagher, 2018; Peters et al., 2012). This method has been validated to have the prominent advantages of combining significant with nonsignificant findings and accounting for positive and negative peaks in the same brain map (Radua et al., 2012). Therefore, the meta‐analytic results obtained from AES‐SDM may be more precise and unbiased. Notably, our meta‐analysis was restricted to whole‐brain voxel‐based morphometry (VBM) studies investigating regional GMV associated with extraversion since other GM metrics are currently insufficient. Finally, we examined the effects of gender and age on the observed associations between extraversion and GMV.

2. METHODS

2.1. Literature search

To identify brain GM studies of extraversion up to December 25, 2018, a systematic literature search was performed in the PubMed, Web of Science, and ProQuest databases using the following search keywords: “extraversion” AND (“MRI” OR “magnetic resonance imaging” OR “gray matter” OR “VBM” OR “voxel‐based morphometry” OR “SBM” OR “surface‐based morphometry” OR “cortical thickness” OR “cortical surface area” OR “cortical folding” OR “brain structure” OR “neuroimaging” OR “brain imaging” OR “imaging”). In addition, we manually checked the references of relevant reviews and identified additional pertinent articles.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

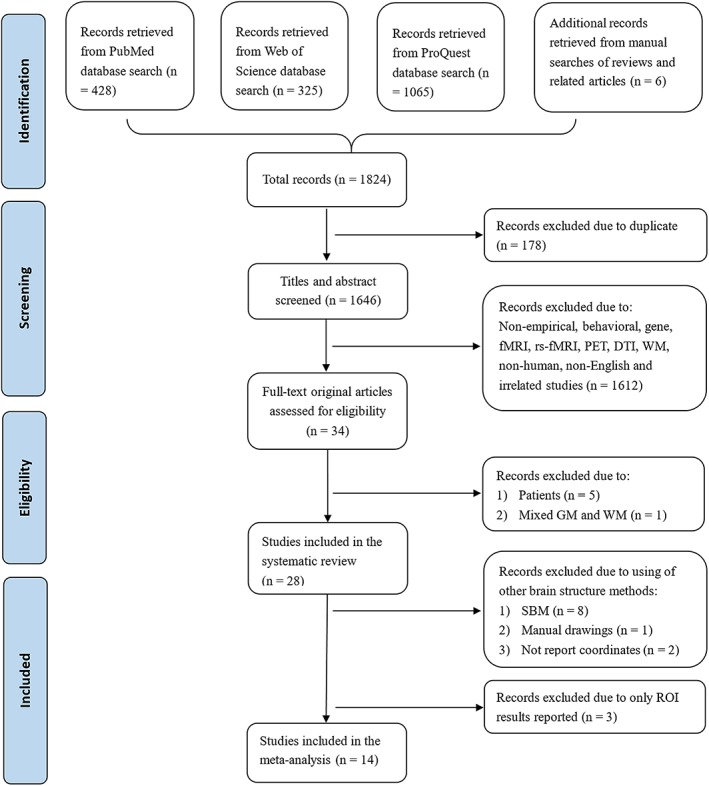

A total of 1,824 candidate articles were retrieved from the abovementioned searches (see Figure 1). Studies were selected for the systematic review when they (a) enrolled healthy people as participants; (b) used extraversion as the research variable; (c) used brain structure morphometric measures as the research method; and (d) reported GM correlates of extraversion. Studies were excluded from the systematic review if they (a) were not empirical studies (e.g., reviews, meta‐analyses, and meeting abstracts); (b) used patients or animals as participants; (c) were not published in English; or (d) did not have the full text available. For the meta‐analysis, the included studies not only met all the above criteria but were also required to (a) use VBM as a research method; (b) report whole‐brain GMV correlates of extraversion (including nonsignificant results); and (c) present peak coordinates in the Talairach or Montreal Neurological Institute space. For studies that did not specify the whole‐brain results or peaks in stereotaxic coordinate space, we contacted the corresponding authors to obtain the necessary details. Two authors (H.L. and S.W.) were responsible for assessing each article and extracting the coordinates separately. The third author (Q.G.) was responsible for resolving divergences. Figure 1 illustrates the integrated data selection steps according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses statement (Liberati et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses flow diagram of data selection in the current systematic review and meta‐analysis. DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; GM, gray matter; PET, positron emission tomography; rs‐fMRI, resting‐state fMRI; SBM, surface‐based morphometry; WM, white matter [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.3. Data analysis

2.3.1. Descriptive analysis

The basic information for each identified study was described, including the sample size, gender ratio, mean age, extraversion measurements, GM measurements, statistical thresholds, and main findings. In addition, we summarized and categorized the results from studies using region of interest (ROI) and whole‐brain analysis methods.

2.3.2. Meta‐analysis of VBM studies

To detect brain regions where the GMV was stably correlated with extraversion, a meta‐analysis was conducted using AES‐SDM software (version 5.15) (https://www.sdmproject.com/software/). Based on the methods proposed by Radua and Mataix‐Cols (2009); Radua et al. (2012), the meta‐analysis included the following steps. First, we extracted peak coordinates and their corresponding t statistics from each included study and created an SDM table to collect raw data. Then, the original effect‐size brain maps of each included study were recreated to generate voxel‐level Monte Carlo brain maps. Finally, a mean map was obtained using a voxelwise calculation in a random‐effects model, which was weighted by sample size, intrastudy variance, and interstudy heterogeneity. To obtain more stable and reliable results from the meta‐analysis, we set the permutation at 20 (Yao et al., 2017) and used standard SDM thresholds (voxelwise p < .005, SDM‐Z > 1, and cluster size >10 voxels), which have been verified to effectively balance false positives and negatives (Han et al., 2018; Pan et al., 2017; Radua et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2016).

Moreover, to examine the reliability of the findings, we performed jackknife sensitivity analyses, which repeat the same meta‐analysis with omission of one study (including studies reporting nonsignificant results) each time (Radua et al., 2012; Radua & Mataix‐Cols, 2009). We also constructed funnel plots and conducted Egger's test in the identified regions to assess possible publication bias (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, 1997; Sterne & Egger, 2001). Publication bias is considered to be absent if the funnel plot is symmetrical and the p‐value of Egger's test is greater than .05 (Egger et al., 1997; Sterne & Egger, 2001).

Additionally, heterogeneity analyses with Q statistics were performed to examine interstudy heterogeneity (Radua et al., 2012; Radua & Mataix‐Cols, 2009). Heterogeneous brain regions were determined using a standard SDM threshold (voxelwise p < .005, SDM‐Z > 1, and cluster size >10 voxels) (Pan et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2016). To explain heterogeneity across studies, we carried out meta‐regression analyses (Radua et al., 2012; Radua & Mataix‐Cols, 2009) to investigate the potential effects of gender and age on the association between extraversion and GMV. Because the meta‐regression analysis is a kind of exploratory analysis method, we used a more stringent threshold (voxelwise p < .0005, SDM‐Z > 1, and cluster size >10 voxels) to decrease the probability of false findings (Pan et al., 2017).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Included studies and sample characteristics

As shown in Figure 1, 178 duplicates were initially rejected from the 1,824 candidate articles, and 1,612 studies were excluded from the remaining 1,646 studies after screening the titles and abstracts. Subsequently, 34 full‐text original articles were evaluated for eligibility. Of these articles, five studies were excluded from the systematic review due to the use of patients as participants (Benedict et al., 2008; Li et al., 2018; Mahoney, Rohrer, Omar, Rossor, & Warren, 2011; Nickson et al., 2016; Sollberger et al., 2009), and one study was excluded for not segmenting GM and WM (DeYoung et al., 2010). As a consequence, a total of 28 studies met the criteria and were included in the systematic review (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of the studies included in the systematic review and meta‐analysis

| Study | Sample size | Ratio F/M | Mean age (SD) or range | Scale | Scanner/FWHM (mm) | Measure of GM | Areas of interest | Nuisance covariate | Statistical analysis/p‐value corr | Main findings about E‐GM associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andari, Schneider, Mottolese, Vindras, and Sirigu (2014)a,1,III, * | 30 | 13/17 | 23.57 (3.70) | NEO PI‐R | 1.5 T/8 | VBM: GMV | AMYG, hippocampus | Gender, age, TGMV | GLM/ROI: p < .05, FWE corr; WBA: p < .05, nonstationary corr. | ROI: Negative E‐GMV: left hippocampus; right AMYG and AMYG/hippocampus complex. WBA: Negative E‐GMV: bilateral MTG; right PHG, AMYG/hippocampus, ITG, LG, precuneus. |

| Bjornebekk et al. (2013)a,2,III | 265 | 150/115 | 49.8 (17.4) | NEO‐PI‐R | 1.5 T/15 | SBM: GMV, CT and CSA | AMYG, accumbens, caudate, and putamen | Gender, age, TIV, the remaining four traits | GLM/ROI: p < .05, Bonf corr; WBA: p < .05, Monte Carlo corr. | ROI: 1. E‐TBV: NS. WBA: 1. Negative E‐CT: left IFGt. 2. E‐CSA: NS. |

| Blankstein, Chen, Mincic, McGrath, and Davis (2009)b,1,2,I | 35 | 20/15 | 16–17 | NEO‐FFI | 3 T/10 | VBM: GMV;SBM: CT | MFG, mPFC, sgACC | Gender, TIV | ANCOVA/p < .05, FDR corr | 1. Positive E‐GMV: left MFG. 2. Positive E‐GMV modulated by gender: left mPFC (positive in males, negative in females). 3. E‐CT: NS. |

| Coutinho et al. (2013)a,1,II, * | 52 | 29/23 | 25.0 (5.1) | NEO‐FFI | 1.5 T/10 | VBM: GMV | – | Gender, age, TIV | GLM/p < .05, Monte Carlo corr | Negative E‐GMV: bilateral MFG and OFC; right SFG and IFG. |

| Cremers et al. (2011)a,1,III, * | 65 | 42/23 | 40.5 (9.7) | NEO‐FFI | 3 T/8 | VBM: GMV | AMYG, OFC, ACC | Gender, age, scan center, TGMV | GLM/ROI: p < .05, FWE(SVC) corr and p < .001, uncorr; WBA: p < .05, FWE corr and p < .001, uncorr | ROI: 1. Positive E‐GMV (p < .05, corr): Right mOFC and mAMYG. 2. Positive E‐GMV (p < .001, uncorr): left OFC. 3. Males showed positive E‐GMV in ACC whereas females showed negative correlation. WBA: 1. E‐GMV (at p < .05, corr): only found in ROIs. 2. Positive E‐GMV (at p < .001, uncorr): bilateral OFC; left ptCG and cerebellar pt lobe; right AMYG and SPL. 3. Negative E‐GMV (at p < .001, uncorr): left IFG, SPL, and CalcS; right PG. |

| Forsman et al. (2012)a,1,II, * | 32 | 0/32 | 33.2 (7.8) | 16PF | 1.5 T/12 | VBM: GMV | – | Age | GLM/p < .05, FDR, corr | Negative E‐GMV: bilateral SFG, MFG, and SMG; left vlPFC, IPS, IOG, thalamus; right SFS, IFG, MTG, AG, caudate nucleus. |

| Gray, Owens, Hyatt, and Miller (2018)c,2,I | 1,105 | 600/505 | 28.8 (3.7) | NEO‐FFI | 3 T/− | SBM: GMV | Hippocampus, AMYG | Gender, age, TIV | GLM/p < .05, FDR, corr | E‐GMV: NS. |

| Grodin and White (2015)a,1,III, * | 83 | 46/37 | 24.9 (7.7) | MPQ‐BF | 3 T/12 | VBM: GMV | Nucleus accumbens, OFC | Gender, age, alternate extraversion traits | GLM/ROI: p < .05, Bonf corr. WBA: p < .05, FDR, corr&p < .001, uncorr. | ROI: 1. Positive Agentic E‐GMV and affiliative E‐GMV: bilateral OFC. 2. Gende × Agentic E and gender × affiliative E: NS. WBA: 1. Positive Agentic E‐GMV: Left PG, PHG, CG, caudate at p < .05, corr; right SFG, hippocampus, FG and cuneus at p < .001, uncorr. 2. Positive affiliative E‐GMV (p < .001, uncorr): right mPFC, MFG, PG, CG, TL, and SPL. 3. Negative affiliative E‐GMV (p < .001, uncorr): Left MTG and PosG; right IPL. 4. Gender × agentic E and gender × affiliative E (p < .05, corr): NS. |

| Hu et al. (2011)a,1,II, * | 62 | 31/31 | 26.6 (4.5) | NEO‐FFI | 1.5 T/8 | VBM: GMV | – | Different combinations (gender, age, TGMV) | GLM/p < .05, FWE corr | NS E‐GMV found in any brain regions. |

| Jackson, Balota, and Head (2011)c,2,I | 79 | 59/20 | 66 (12.5) | NEO‐FFI | 1.5 T/− | SBM: GMV | GM, WM,SFG,VLPFC/DLPFC, OFC, PHG, hippocampus and AMYG | Age, TIV, years of education, SES | GLM/p < .05, uncorr | 1. E‐TGMV: NS. 2. E‐rGMV: NS. |

| Kapogiannis, Sutin, Davatzikos, Costa, and Resnick (2013)a,1,II, * | 87 | 42/45 | 72 (7.7) | NEO‐PI‐R | 1.5 T /12 | VBM: GMV | – | Gender, age, TIV, years of education | GLM/p < .05, FWE corr | 1. Positive E‐GMV: bilateral MFG; left SFG, STG extending into the MTG, ITG and PHG, aCG, SMA, and IOG; right insular. 2. Negative E‐GMV: left SPL and IOG; right PHG. |

| Koelsch, Skouras, and Jentschke (2013)a,1,II, * | 59 | 34/25 | 24.15 (2.40) | NEO‐FFI&NEO‐PI‐R | 3 T/4 | VBM: GMV | – | Gender, age, TIV | Correlation/p < .05, FWE corr | NS E‐GMV found in any brain regions. |

| Kong, Hu, Xue, Song, and Liu (2015)a,1,I | 294 | 157/137 | 21.57 (1.01) | NEO‐PI‐R | 3 T/8 | VBM: GMV | Left mid‐DLPFC (SFG) | Gender, age, TGMV | Correlation/p < .05, Bonf corr | Negative E‐GMV: left mid‐DLPFC (SFG). |

| Kong, Wei, et al. (2015)a,1,I | 308 | 167/141 | 19.94 (1.27) | EPQ | 3 T/10 | VBM: GMV | Left DLPFC | Gender, age, TGMV | Correlation/p < .05, uncorr | Negative E‐GMV: left DLPFC. |

| Kunz, Reuter, Axmacher, and Montag (2017)c,1,2,II | 105 | 55/50 | 18–30 | NEO‐FFI | 3 T/− | VBM/SBM: TGMV | – | Gender, age | GLM/p < .05, Bonf corr | Positive E‐TGMV. |

| Liu et al. (2013)a,1,II, * | 227 | 168/59 | 25.8 (8.35) | NEO–FFI | 1.5 T/3 T/8 | VBM: GMV&WMV | – | Gender, age, scanner type, other 4 traits | GLM/p < .05, FWE corr | NS E‐GMV found in any brain regions. |

| Lu et al. (2014)a,1,II, * | 71 | 37/34 | 22.35 (1.5) | EPQ‐RSC | 3 T/8 | VBM: GMV | – | Gender, age, TIV | GLM/p < .05, AlphaSim corr | Negative E‐GMV: bilateral AMYG and PHG; left SFG; right MTG. |

| Montag et al. (2013)c,3,I | 267 | 191/76 | 25.78 (8.33) | EPQ‐R | 1.5 T/3 T/− | VHR: GMV | – | Gender, age, scanner type | Correlation/p < .05, Bonf corr | Positive E‐VHRGM (left/right) was found in males but not females. |

| Nostro et al. (2017)a,1,2,II, * | 364 | 182/182 | 29.1 (3.45) | NEO‐FFI | 3 T/8 | VBM: GMV;SBM: CT and CSA | – | Gender, age, TIV | GLM/p < .05, FWE corr | 1. E‐GMV, E‐CT, and E‐CSA across entire sample: NS. 2. Only positive E‐GMV in males but not in females: bilateral precuneus/POS and thalamus; left FG/cerebellum; right cerebellum. |

| Omura et al. (2005)a,1,III, * | 41 | 22/19 | 23.8 (5.4) | NEO‐PI‐R | 3 T/12 | VBM: GM concentration | AMYG | Gender, age | GLM/ROI: p < .05, FWE(SVC) corr. WBA: p < .001, uncorr. | ROI: Positive E‐GMC: left AMYG at p < .05, corr; right AMYG (trend significant). WBA: 1. Positve E‐GMC: bilateral OFC; left PHG and FG; right STG and CalcS. 2. Negative E‐GMC: bilateral PG. |

| Onitsuka et al. (2005)c,5,I | 26 | 0/26 | 43 (7.1) | NEO–FFI | 1.5 T/− | Manual drawings: GMV | FG | – | Spearman's correlation/p < .05, Bonf corr | NS relationships found in bilateral FG. |

| Privado et al. (2017)a,4,II | 56 | 56/0 | 18.29 (1.09) | NEO‐FFI | 3 T/30(CT)/40 (GMV and CSA) | SBM: GMV,CT and CSA | – | AGE, TGMV, TCSA or mean CT | Pearson's correlation/p < .001, uncorr | Positive E‐GMV and E‐CSA: left occipital area. |

| Rauch et al. (2005)b,2,I | 14 | 6/8 | 21–34 | NEO‐FFI | 1.5 T/13 | SBM: CT | mOFC | – | Correlation/p < .05, uncorr | Positive E‐CT: right mOFC. |

| Riccelli et al. (2017)a,2,II | 507 | 300/207 | 22–36 | NEO‐FFI | 3 T/− | SBM: GMV, CT, CSA, CF | – | Gender, age, TIV, other 4 traits | GLM/p < .05, Monte Carlo corr | 1. Negative E‐GMV: left STG and entorhinal cortex. 2. Positive E‐CT: left precuneus. 3. Negative E‐CSA: right STG. 4. Positive E‐CF: right FG. |

| Taki et al. (2013)a,1,II, * | 274 | 161/113 | 51.2(11.8) | NEO‐PI‐R | 0.5 T/8 | VBM: GMV | – | Gender, age, TIV | GLM/p < .05, FWE corr | NS E‐GMV found in any brain regions. |

| Wright et al. (2007)b,2,III | 29 | 17/12 | 70.3 (6.6) | NEO–FFI | 1.5 T/13 | SBM: CT; manual tracing: AMYG volumes | PFC, AMYG | Gender, age, TIV | GLM and partial correlation/PFC: p < .001, uncorr; outside of PFC: p < .0001, uncorr; AMYG: p < .05, Bonf corr | ROI: 1. NS E‐AMYG volume. 2. Positive E‐CT: left MFC; right SFC. WBA:NS E‐CT were found in regions outside of PFC. |

| Wright et al. (2006)b,2,III | CT: 28,AMYG:20 | CT: 17/11,AMYG: 12/8 | CT: 24 (2.9),AMYG: 24 (2.1) | NEO–FFI | 1.5 T/18.4 | SBM: CT; manual tracing: AMYG volume | PFC, AMYG | Gender, age, TIV | GLM and partial correlation/PFC: p < .00031, uncorr; outside of PFC: p < .00013, uncorr; AMYG: p < .05, Bonf corr | ROI: 1. NS E‐AMYG volume. 2. Negative E‐CT: right IFC. WBA: only one region outside of PFC (right FG) was found to have negative E‐CT. |

| Zou, Su, Qi, Zheng, and Wang (2018)a,1,II, * | 100 | 50/50 | 21.91 (2.29) | EPQ–RSC | 3 T/6 | VBM: GMV | – | Gender, age | GLM/p < .05, FWE corr | Negative E‐GMV: bilateral putamen. |

Note. For studies including both ROI and whole‐brain results, only the whole‐brain results were included in the meta‐analysis. In addition, for studies including both patients and healthy controls, only the healthy control groups were included. Superscript letters a, b, and c represent peak coordinates reported in MNI space, reported in Talairach space, or not reported, respectively. Superscript numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 represent images processed using the VBM toolbox within SPM, using FreeSurfer, using FSL FMRIB, using CIVET, or not specified, respectively. Superscript roman numerals I, II, and III represent data analysis performed using the ROI approach, the whole‐brain approach, or both, respectively.

Abbreviations: 16PF, Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire; a, anterior; ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; AG, angular gyrus; AMYG, amygdala; Bonf, Bonferroni; CalcS, calcarine sulcus. m, medial; CF, cortical folding; CG, cingulate gyrus; corr, correction; CSA, cortical surface area; CT, cortical thickness; dl, dorsal‐lateral; E, extraversion; EPQ‐RSC, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire‐Revised Short Scale for Chinese; F, female; FDR, false discovery rate; FG, fusiform gyrus; FWE, family‐wise error; FWHM, full width at half maximum; GLM, general linear model; GMV, gray matter volume; IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; IOG, inferior occipital gyrus; IPL, inferior parietal lobule; IPS, intraparietal sulcus; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; LG, lingual gyrus; M, male; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; mid, middle; mPFG, medial prefrontal cortex; MPQ‐BF, Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire Brief Form; MTG, middle temporal gyrus; NEO‐FFI, NEO Five Factor Inventory; NEO‐PI‐R, Revised NEO Personality Inventory; NS, not significant; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; PFC, prefrontal cortex; PG, precentral gyrus; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; POS, parieto‐occipital sulcus; PosG, postcentral gyrus; pt, posterior; ROI, region of interest; SBM, surface‐based morphometry; SD, standard deviation; SES, socioeconomic status; SFG, superior frontal gyrus; sg, subgenual; SMG, supramarginal gyrus; SPL, superior parietal lobule; STG, superior temporal gyrus; SVC, small volume correction; t, triangularis; TBV, total brain volume; TCSA, total CSA; TGMV, total GMV; TIV, total intracranial volumes; TL, temporal pole; uncorr, uncorrection; VBM, voxel‐based morphometry; VHRGM, gray matter volumetric hemispheric ratio; vl, ventral‐lateral; WBA, whole‐brain analysis; WMV, white matter volume.

Studies included in the meta‐analysis.

Among the identified studies included in the review, 11 studies were excluded from the meta‐analysis due to the use of other brain structure analysis methods, such as surface‐based morphometry (SBM) (Bjornebekk et al., 2013; Gray et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2011; Privado et al., 2017; Rauch et al., 2005; Riccelli et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2006; Wright et al., 2007) and manual drawing (Onitsuka et al., 2005), and failure to report peak coordinates (Kunz et al., 2017; Montag et al., 2013). Additionally, three VBM studies were excluded for reporting only ROI results (Blankstein et al., 2009; Kong, Hu, et al., 2015; Kong, Wei, et al., 2015). Finally, a total of 14 studies meeting the criteria, which included 1,547 healthy subjects (857 females; 33.8 ± 7.3 years old) and covered 100 peaks of stereotaxic coordinates, were entered into the meta‐analysis (see Table 1).

3.2. Systematic review of GM correlates

Only three studies examined the association between extraversion and global GMV, but they exhibited heterogeneous findings (see Table 1). One study showed a positive association (Kunz et al., 2017) unlike the other two studies that did not reveal a significant correlation (Jackson et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2013). In addition, a study focusing on volumetric hemispheric ratios for GM (VHRgm, left GMV/right GMV) found a gender‐by‐extraversion interaction effect, and the positive extraversion–VHRgm association existed only in males and not in females (Montag et al., 2013).

More importantly, a considerable number of studies examined the association between extraversion and regional GM structures. The findings suggested that extraversion is mainly associated with the GM structures in the prefrontal (e.g., the OFC, middle frontal gyrus [MFG], superior frontal gyrus [SFG], inferior frontal gyrus, and anterior cingulate cortex/medial prefrontal cortex [mPFC]), temporal–parietal–occipital (e.g., the superior temporal gyrus [STG], supramarginal gyrus [SMG], and angular gyrus [AG]), and subcortical (e.g., the amygdala, hippocampus, and parahippocampus [PHG]) regions, although these findings showed relatively high heterogeneity (see Table 1). The findings related to the extraversion‐regional GM associations are described in detail in the Supplemental Material.

3.3. Meta‐analysis of GMV

3.3.1. Core brain regions correlated with extraversion

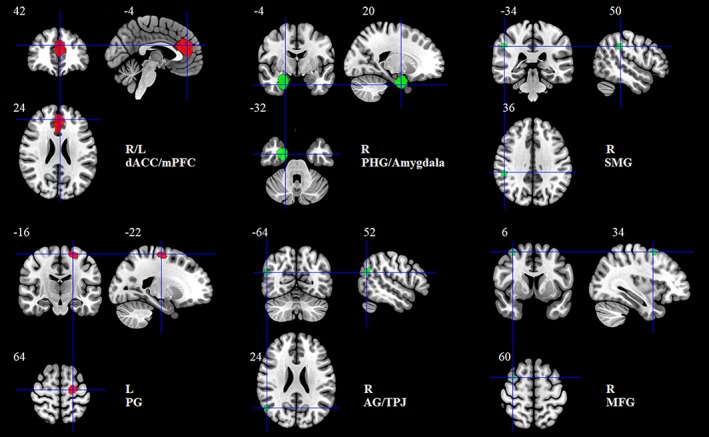

To obtain reliable brain regions where the GMV was associated with extraversion, we conducted a meta‐analysis using the AES‐SDM approach. The results revealed that extraversion was positively correlated with two clusters, including the bilateral dorsal ACC extending to the mPFC (dACC/mPFC) and the left precentral gyrus (PG). In contrast, a negative association was reported between extraversion and the GMV in four clusters, including the right PHG extending to the amygdala (PHG/amygdala), right SMG, right AG/temporoparietal junction (AG/TPJ), and right MFG (see Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2.

Brain regions where GM volume was significantly correlated with extraversion in the meta‐analysis

| Clusters | R/L | BA | of peaks | Number of voxels | Local peaks MNI coordinates (X, Y, Z) | SDM‐Z | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive correlation | |||||||

| dACC/mPFC | R/L | 32 | 2 | 973 | −4,42,24 | 1.342 | .0002 |

| −2,44,12 | 1.197 | .0007 | |||||

| PG | L | 6 | 2 | 149 | −22,‐16,64 | 1.21 | .0007 |

| −26,‐16,60 | 1.157 | .0009 | |||||

| Negative correlation | |||||||

| PHG/amygdala | R | 28/34/35/36 | 2 | 672 | 20,‐4,‐32 | −1.383 | .0003 |

| 24,‐4,‐24 | −1.378 | .0003 | |||||

| SMG | R | 40 | 1 | 68 | 50,‐34,36 | −1.181 | .0011 |

| AG/TPJ | R | 39 | 1 | 53 | 52,‐64,24 | −1.002 | .0030 |

| MFG | R | 8 | 1 | 28 | 34,6,60 | −1.088 | .0018 |

Note. Clusters were identified at voxelwise p < .005, SDM‐Z > 1, and cluster size >10 voxels.

Abbreviations: AG, angular gyrus; BA, brodmann area; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; GM, gray matter; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; MNI, montreal neurological institute; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; L, left; PG, precentral gyrus; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; R, right; SMG, supramarginal gyrus; TPJ, temporoparietal junction.

Figure 2.

Brain regions showing positive (red) and negative (green) correlation with extraversion in the meta‐analysis. Clusters were displayed at voxelwise p < .005, z > 1, and cluster size >10 voxels [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3.2. Reliability of the main findings

The jackknife sensitivity analyses revealed that the results observed in the main meta‐analysis were highly consistent, and all six brain clusters were repeatedly identified in no fewer than 12 combinations (see Table 3). Notably, Liu et al. (2013) treated neuroticism as one nuisance covariate to control for other confounding effects, but we obtained the same results in the meta‐analysis without the study of Liu et al. (2013).

Table 3.

Jackknife sensitivity analyses of the studies included in the meta‐analysis

| Discarded study | Positive correlation | Negative correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R/L dACC/mPFC | L PG | R PHG/amygdala | R SMG | R AG/TPJ | R MFG | |

| Andari et al. (2014) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Coutinho et al. (2013) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Cremers et al. (2011) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Forsman et al. (2012) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Grodin and White (2015) | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Kapogiannis et al. (2013) | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lu et al. (2014) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Nostro et al. (2017)a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Omura et al. (2005) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hu et al. (2011)a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Koelsch et al. (2013)a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Liu et al. (2013)a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Taki et al. (2013)a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zou et al. (2018) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Total | 12/14 | 12/14 | 12/14 | 12/14 | 12/14 | 12/14 |

Abbreviations: AG, angular gyrus; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; L, left; PG, precentral gyrus; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; R, right; SMG, supramarginal gyrus; TPJ, temporoparietal junction.

Studies reporting nonsignificant results.

Furthermore, we used a funnel plot and Egger's test to assess potential publication biases for the brain regions identified in the meta‐analysis. In all six clusters, the funnel plots were found to be roughly symmetric, and Egger's tests did not detect significant differences, suggesting that there was no publication bias in our main findings.

3.3.3. Heterogeneity and meta‐regression analyses

Heterogeneity analyses with Q statistics exhibited significant interstudy variability in several brain regions, including the left dACC/mPFC, right MFG/PG, right MFG/dorsolateral SFG, right MFG, left STG, left middle temporal gyrus, right AG/TPJ, right lingual gyrus, left inferior occipital gyrus, left anterior thalamus, left amygdala, right amygdala/PHG, right caudate nucleus, and right putamen, which is consistent with the heterogeneous findings in the systematic review.

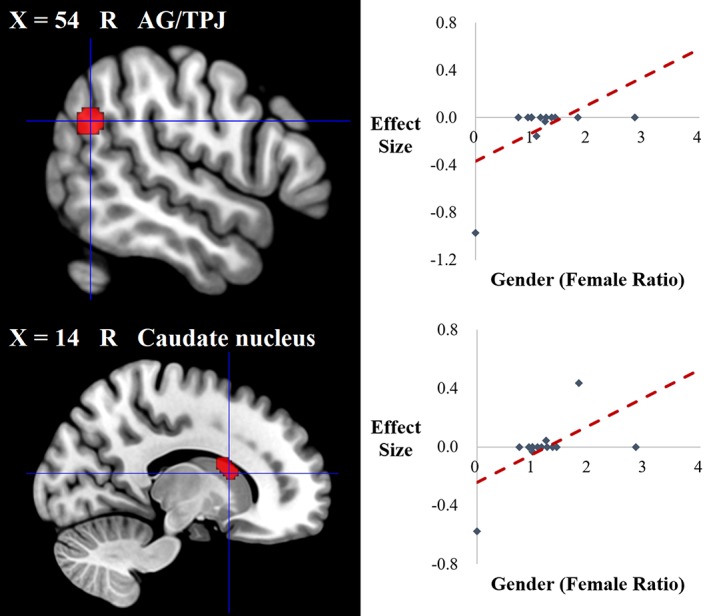

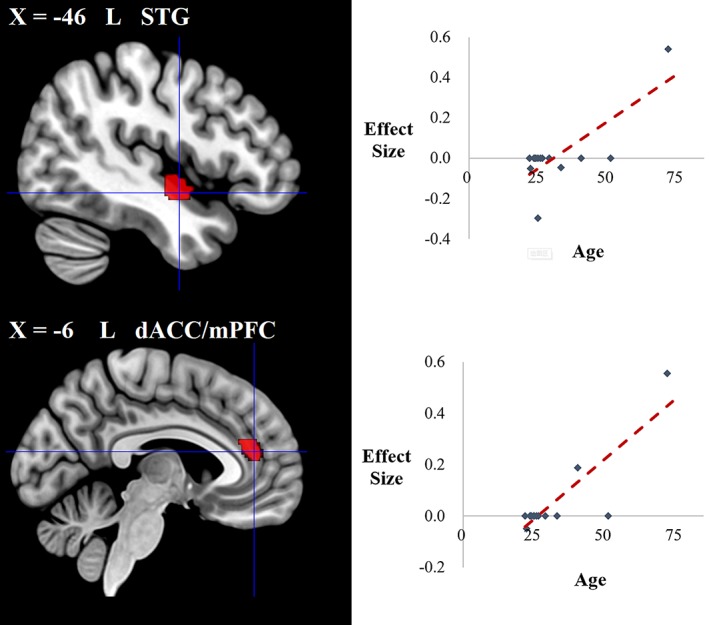

To account for the heterogeneity between studies, we performed meta‐regression analyses to explore the potential effects of gender and age. The association of extraversion with GMV in two clusters (i.e., the right AG/TPJ and caudate nucleus) was modulated by the female ratio (see Table 4 and Figure 3). The association of extraversion with GMV in another two clusters (i.e., the left STG and dACC/mPFC) was shown to be modulated by age (see Table 4 and Figure 4).

Table 4.

The results of the meta‐regression analyses showing that gender and age modulate the extraversion–GMV relationship

| Meta‐regression | Clusters | R/L | BA | Number of peaks | Number of voxels | Local peaks MNI coordinate (X, Y, Z) | SDM‐Z | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of gender | Female ratio was associated with extraversion‐related GMV | |||||||

| AG/TPJ | R | 39 | 1 | 62 | 54, −58, 28 | 1.531 | .0001 | |

| Caudate nucleus | R | – | 1 | 57 | 14, 12, 14 | 1.535 | .0001 | |

| Effect of age | Mean age was associated with extraversion‐related GMV | |||||||

| STG | L | 48/22 | 1 | 156 | −46, −6, −10 | 3.323 | .0000 | |

| dACC/mPFC | L | 32 | 1 | 83 | −6, 42, 16 | 3.341 | .0000 | |

Note. Clusters were identified at voxelwise p < .0005, SDM‐Z > 1, and cluster size >10 voxels.

Abbreviations: AG, angular gyrus; BA, brodmann area; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; MNI, montreal neurological institute; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; L, left; R, right; STG, superior temporal gyrus; TPJ, temporoparietal junction.

Figure 3.

Brain regions where the associations of extraversion with GMV were modulated by gender in the meta‐regression analysis. Clusters were displayed at voxelwise p < .0005, z > 1, and cluster size >10 voxels [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 4.

Brain regions where the associations of extraversion with GMV were modulated by age in the meta‐regression analysis. Clusters were displayed at voxelwise p < .0005, z > 1, and cluster size >10 voxels [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

The present systematic review revealed that extraversion was linked with brain GM differences widely distributed across cortical and subcortical regions, providing a preliminary outline of the brain GM substrates underlying extraversion, although relatively high levels of heterogeneity and inconsistency were evident in the previous findings. Furthermore, the meta‐analysis of the whole‐brain VBM studies identified six core brain regions related to extraversion, with two clusters showing positive associations (i.e., the bilateral dACC/mPFC and left PG) and four clusters showing negative associations (i.e., the right PHG/amygdala, right SMG, right AG/TPJ, and right MFG). The jackknife sensitivity analyses and publication bias analyses demonstrated the robustness and reliability of these findings. Additionally, our study found that gender and age modulated the associations between extraversion and regional GMV, which may have been factors leading to interstudy heterogeneity. To our knowledge, this study is the first to reveal a comprehensive picture of brain GM correlates of extraversion.

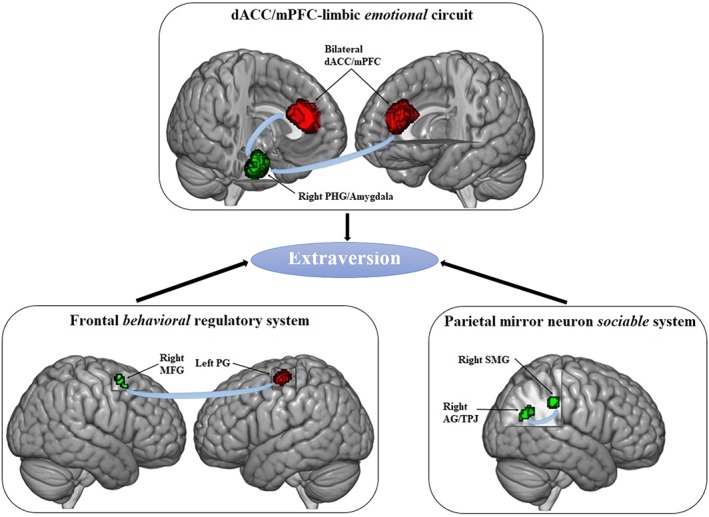

In the following sections, we will first discuss the relationships between extraversion and its corresponding stable brain GMV correlates based on three extraversion‐related functional systems, including the dACC/mPFC‐limbic emotional circuit, frontal behavioral regulatory system and parietal mirror neuron sociable system (see Figure 5). Furthermore, we will offer an explanation for the interstudy heterogeneity caused by gender and age that hints at the importance of covariate selection for statistical models.

Figure 5.

Three functional neural circuits underlying extraversion. Positive and negative extraversion‐related clusters were displayed in red and green, respectively [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4.1. The dACC/mPFC‐limbic emotional circuit

One of the core neural circuits exhibiting extraversion‐related brain GMV alterations was the dACC/mPFC‐limbic circuit, where the bilateral dACC/mPFC had a positive association with extraversion, and the right PHG/amygdala had a negative association with extraversion. These findings were surmised to be related to the positive emotional characteristics of extraversion.

The amygdala and PHG are both substantial parts of the limbic system (Catani, Dell'Acqua, & De Schotten, 2013). Previous studies have shown that the right amygdala is responsible for emotional perception based on its activation in response to emotional stimuli (Costafreda, Brammer, David, & Fu, 2008) and, in particular, to fear‐provoking, threatening, or anxiogenic conditions (Morris, Öhman, & Dolan, 1999; Öhman, 2005; Stein, Simmons, Feinstein, & Paulus, 2007). The adjacent PHG is considered to be related to emotional memory and valence (Fenker, Schott, Richardson‐Klavehn, Heinze, & Düzel, 2005; Medford et al., 2005; Murty, Ritchey, Adcock, & LaBar, 2010) and has been shown to have strong functional connectivity with the amygdala in negative emotional processing (Kilpatrick & Cahill, 2003; Ritchey, Dolcos, & Cabeza, 2008). When experiencing negative events, the amygdala is activated to perceive negative emotions; meanwhile, the amygdala increases its influence on the PHG, which engages in emotional memory‐related activities, to intensify negative emotion perception (Kilpatrick & Cahill, 2003; Ritchey et al., 2008), reflecting these regions' roles in processing negative emotions. Numerous studies have found that morphometric abnormalities in the right amygdala and PHG are probably related to emotion‐related disorders such as major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder (Bora, Fornito, Pantelis, & Yücel, 2012; Romanczuk‐Seiferth et al., 2014). Thus, extraverts, who are known to experience less negative emotions than introverts (Costa & McCrae, 1980; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998), may have smaller brain GMVs in these two negative emotion‐related regions. Consistent with two studies reporting lower activation of the amygdala in response to fearful facial expressions among extraverts versus introverts (Swartz, Waller, et al., 2017; Swartz, Knodt, Radtke, & Hariri, 2017), our findings suggest that the GMV differences in the right amygdala and PHG may be a foundation of the emotional differences between extraverts and introverts.

Another cluster detected in the emotional circuit was the bilateral dACC/mPFC, which showed a positive association with extraversion. This finding fits well with a previous study revealing that GM loss in this region causes a decrease in extraversion (Mahoney et al., 2011). A considerable number of studies have demonstrated that the bilateral dACC/mPFC is an important brain area exhibiting strong functional connectivity with the amygdala during emotional processing (Etkin, Egner, & Peraza, 2006; Kim, Gee, Loucks, Davis, & Whalen, 2010; Quirk, Likhtik, Pelletier, & Paré, 2003). When encountering emotional conflicts, the bilateral dACC and dorsal mPFC are activated to detect emotional distress and downregulate the amygdala's activity with emotion regulation strategies such as reappraisal, which is a kind of top‐down cognitive emotion regulation strategy (Etkin, Egner, & Kalisch, 2011; Giuliani, Drabant, & Gross, 2011; Kalisch, 2009; Ochsner & Gross, 2005), to maintain emotional stability. Therefore, our findings showing that extraverts have greater GMV in the bilateral dACC/mPFC than introverts may reflect differing emotional conflict detection and regulation abilities between extraverts and introverts. Specifically, on the one hand, extraverts who are sensitive to rewarding stimuli (Saklofske, Eysenck, Eysenck, Stelmack, & Revelle, 2012) may perceive more happiness in the condition triggering positive emotion and consequently need more emotional regulation. Thus, a larger GMV in the bilateral dACC/mPFC in extraverts may benefit their emotion regulation abilities, which is consistent with previous findings demonstrating that extraverted individuals exhibited greater activation in the ACC when viewing positive stimuli (Haas, Omura, Amin, Constable, & Canli, 2006; Hooker, Verosky, Miyakawa, Knight, & D'Esposito, 2008). On the other hand, a larger GMV in these two brain regions may increase extraverts' sensitivity to emotional conflicts and their likelihood of adopting a cognitive emotional reappraisal strategy to regulate negative emotional conflicts to remain positive.

In brief, the dACC/mPFC‐limbic circuit, where extraversion‐related brain morphometric alterations may result in emotional differences, may be tightly connected to the salient positive emotional features of extraversion and probably supports extraversion to exert a protective effect against affective disorders.

4.2. The frontal behavioral regulatory system

Another important neural circuit that displayed extraversion‐related brain GMV variation was the frontal behavioral regulatory system, where we observed a positive association in the left PG and a negative association in the right MFG. We hypothesize that these findings may account for the behavioral characteristics of extraversion.

Extraverts have been shown to behave differently from introverts. They are more energetic and prefer to explore the external world to seek novelty and fun; therefore, extraverts more frequently engage in movement, exercise and social activities, initiate conversations, and talk with other people (Saklofske et al., 2012). Previous studies have revealed neurofunctional differences between extraverts and introverts in the left PG, a well‐studied motor area located in the motor cortex that is largely activated during a series of motion‐related tasks, such as movement preparation (Thoenissen, Zilles, & Toni, 2002), speech production (Behroozmand et al., 2015), and even listening to speech (Wilson, Saygin, Sereno, & Iacoboni, 2004). Moreover, evidence from positron emission tomography (PET) studies with healthy adults has shown that higher levels of extraversion were correlated with increased dopaminergic receptor availability and regional brain metabolism in the left PG (Baik, Yoon, Kim, & Kim, 2012; Volkow et al., 2011), reflecting a role for the left PG in functional motor expression in extraverts. Therefore, our finding of a positive association between extraversion and left PG volume may expand the previous results and may suggest that the GM volumetric diversity in the left PG probably results in divergent functional motor expression between extraverts and introverts contributing to differing styles of motor‐related activities.

Additionally, we uncovered a negative association of extraversion with the GMV in the right MFG, which is another key region of the behavioral regulatory system. The right MFG has been demonstrated to be an essential region responsible for behavioral and inhibitory control (Fassbender et al., 2006; Garavan, Ross, Murphy, Roche, & Stein, 2002; Garavan, Ross, & Stein, 1999; Milham et al., 2001). For example, this region is considered to be linked to cognitive response inhibition, which refers to individuals who inhibit their responses or impulsiveness in a deliberate manner (Garavan et al., 2002). Moreover, decreased activation in the right MFG in response to No‐go trials has been associated with lower response inhibition (Batterink, Yokum, & Stice, 2010). Compared with introverts, extraverts have been suggested to less frequently and less effectively suppress behavioral impulses and control for cogitative behaviors (Saklofske et al., 2012). More generally, extraverts are inclined to behave in a behavior‐driven manner rather than a behavior‐inhibition manner (Carver & White, 1994). In our study, we found that extraverts have a smaller GMV in the right MFG than introverts, suggesting that GM variation in this region may be one of the neural bases underlying the differences in behavioral inhibitory control between the two kinds of people.

In short, the frontal behavioral regulatory system may be related to the behavioral characteristics of extraversion and probably plays an important role in the motor and behavioral style differences between extraverts and introverts.

4.3. The parietal mirror neuron sociable system

The last crucial neural circuit that showed extraversion‐related volumetric GM alterations was the parietal mirror neuron system, where we detected two clusters, including the right SMG and AG/TPJ. These findings are thought to be connected to the sociable characteristics of extraversion.

The right SMG and AG/TPJ are both crucial parts of the parietal mirror neuron system, an important neural structure for social cognition (Chong, Cunnington, Williams, Kanwisher, & Mattingley, 2008; Rizzolatti & Fabbri‐Destro, 2008). Specifically, the mirror neurons found in these structures allow people to imitate and learn others' behaviors during observation to develop the ability to “read” others' minds (Chong et al., 2008; Rizzolatti & Fabbri‐Destro, 2008). Many neuroimaging studies have consistently shown activation in the right SMG and AG/TPJ during tasks of self‐other distinction, perspective‐taking, empathy, and theory‐of‐mind (Carrington & Bailey, 2009; David et al., 2006; Decety & Lamm, 2007; Hoffmann, Koehne, Steinbeis, Dziobek, & Singer, 2016). Moreover, abnormalities in these regions can cause impairments in understanding other people's minds and social cognition skills (Foster et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). Extraversion is a socially relevant concept and is thought to be associated with an individual's sociability (Saklofske et al., 2012). Extraverts, who are known to be more outgoing and sociable, prefer to participate in social activities and enjoy more social interactions with others (Selfhout et al., 2010), where they can have more opportunities to practice their social cognition skill of predicting other people's behavior. Therefore, as our findings showed, the GM volumetric differences in the right SMG and AG/TPJ in the parietal mirror neuron system may partly account for sociability differences between extraverts and introverts.

Interestingly, we found that the decreased GMV in the right SMG and AG/TPJ was linked with increased levels of extraversion. These decreased GM morphological alterations have been related to improvements in social information processing efficiency (Wang et al., 2018). Recent functional neuroimaging studies with healthy adults have shown different patterns of brain activation between extraverts and introverts (Lei, Zhao, & Chen, 2013; Volkow et al., 2011). For example, a PET study found higher baseline metabolism in the bilateral SMG in extraverted individuals (Volkow et al., 2011), and a recent resting‐state functional MRI (fMRI) study indicated that extraverts have more efficient online information processing connections in the right frontoparietal network, which includes the right IPL and AG (Lei et al., 2013). Therefore, the decreased GMV in the right SMG and AG/TPJ may be associated with increased efficiency in social cognition‐related processing, which further leads to higher levels of extraversion.

In other words, the parietal mirror neuron system is likely closely related to the sociable characteristics of extraversion, and the GM volumetric alterations may be beneficial for extraverts' social interactions.

4.4. Gender and age differences

We observed that gender could modulate the association of extraversion with the GMV of the right AG/TPJ and caudate nucleus. These findings are an extension of previous VBM studies that detected an interaction of extraversion with gender in the left mPFC (Blankstein et al., 2009) and the right pregenual ACC (Cremers et al., 2011).

Specifically, in healthy male adults, extraversion was found to be negatively associated with the GMV of the right AG/TPJ (Forsman et al., 2012), while in studies of healthy adults with a higher number of women, this negative correlation was diminished (Grodin & White, 2015; Lu et al., 2014). As mentioned previously, the right AG/TPJ is an important brain GM correlate of extraversion that may reflect the sociable characteristics of extraversion. Previous studies have indicated different brain activation patterns between males and females during social cognition tasks; for example, males show stronger neural responses in the right TPJ when completing emotional perspective‐thinking tasks, while females more strongly recruit the right AG in empathy‐related emotional recognition tasks (Derntl et al., 2010). Therefore, our finding of gender modulation of the association between extraversion and the GMV of the right AG/TPJ may reflect the role of the AG/TPJ in the different patterns of social cognition between male and female extraverts.

We also observed that gender could modulate the association of extraversion with the GMV of the right caudate nucleus. Specifically, in healthy male adults, extraversion was negatively associated with the GMV of the right caudate nucleus (Forsman et al., 2012), while in studies of healthy adults with a growing number of women, this negative correlation was diminished and even changed to the inverse relationship (Cremers et al., 2011). The caudate is well known to be involved in reward‐related processing (Cohen, Young, Baek, Kessler, & Ranganath, 2005; Delgado, Miller, Inati, & Phelps, 2005). Neuroimaging studies have indicated that extraverts who are known to be reward motivated may recruit the reward‐sensitive regions more strongly during tasks that most likely trigger rewarding experiences (Canli et al., 2001). Importantly, previous studies have found that males and females have distinct neural activation patterns in response to different types of reward; that is, males exhibited significant neural activation in the right caudate nucleus in response to a monetary reward, while females exhibited stronger activation in this region in response to a social reward (Spreckelmeyer et al., 2009). Therefore, our finding in the right caudate nucleus may support the distinct neural response patterns in reward processing between male and female extraverts.

In addition, we found that age can modulate the association of extraversion with the GMV in the left STG and dACC/mPFC. First, in the left STG, the association of extraversion with the GMV was found to vary at different ages. Specifically, in early adulthood, extraversion was negatively associated with the GMV in the left STG (Grodin & White, 2015); however, this negative correlation diminished with age (Forsman et al., 2012) and finally changed to a positive correlation at an elderly age (Kapogiannis et al., 2013). The left STG, a crucial region not only in language but also in social cognition development (Bigler et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007; Robins, Hunyadi, & Schultz, 2009), has been shown to exhibit greater activation in extraverts during social cognition‐related tasks (Mobbs, Hagan, Azim, Menon, & Reiss, 2005). Therefore, our finding for the left STG probably reflects differential development of social cognition between extraverts and introverts at different ages. More concretely, developmental neuroscience has delineated a trajectory of GM development in the cerebral cortex. Prominent cortical GM losses between puberty and adolescence have been consistently observed across studies as a sign of brain maturation (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006; Paus, 2005; Shaw et al., 2006). When entering into early adulthood, GM losses of neural architecture continually (Giorgio et al., 2010) induce specific changes to promote social and cognitive development. Later, the GM across cortical regions gradually atrophies with aging, causing a decline in social and cognitive functions (Bergfield et al., 2010). Thus, our findings for the left STG may suggest earlier neural maturation and greater development in this region in extraverts than in introverts between puberty and young adulthood and consequently benefit extraverts' social cognition. Moreover, in elderly adulthood, extraverts may have a slower GM decline in this region than introverts, allowing conservation of more social cognitive abilities, which is consistent with behavioral findings that older extraverts have a greater ability to identify the emotional valence of a neutral face than introverts (Keightley, Winocur, Burianova, Hongwanishkul, & Grady, 2006).

Furthermore, at different ages, we detected a difference in the association of extraversion with the GMV of the left dACC/mPFC (Cremers et al., 2011; Kapogiannis et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2014), a critical extraversion‐related brain region mentioned previously. Unlike the left STG, the associations between extraversion and the GMV of the left dACC/mPFC change faster to the positive direction with age (see Figure 4), likely suggesting faster neural maturation and developmental difference between extraverts and introverts in this region from puberty to late adulthood. These differences may be one of the reasons that we observed a notable positive association of extraversion with this region in the current broad healthy adult samples.

In summary, our findings from the meta‐regression analyses suggest that gender and age are both important covariates when examining the structural brain correlates of extraversion. Previous studies have indicated that the brain GMV correlates of personality traits were influenced by the inclusion of different nuisance covariates in the computational model (Hu et al., 2011). Therefore, gender and age should be fully considered when exploring the brain GMV correlates of extraversion, and additional analyses are suggested to explore how gender and age affect the association of extraversion with GMV.

5. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Several limitations of this study should be taken into consideration. First, we focused on only the brain GM correlates of extraversion without considering the brain WM due to a limited number of relevant studies (Booth et al., 2014; Gurrera et al., 2007; McIntosh et al., 2013; Pang et al., 2018; Privado et al., 2017; Xu & Potenza, 2012). However, with additional DTI studies in the future, a systematic review and meta‐analysis of these studies will be necessary to locate the stable brain WM correlates of extraversion, thus contributing to a more comprehensive neuroanatomical basis underlying extraversion from a multimodal perspective.

Second, only whole‐brain VBM studies were included in our meta‐analysis, and studies using other GM morphometric measurements (CT, CSA, and CF) were not included due to the limited number of relevant studies at present. Interestingly, some researchers have claimed that CT and SA are two unrelated, distinct morphometric indicators and that the GMV is determined by the combination of these two parameters (Panizzon et al., 2009; Winkler et al., 2010). Therefore, whether our meta‐analysis findings are the result of morphometric changes in CT or SA is difficult to discern. Future studies specifying the alterations in these identified extraversion‐related regions by means of a meta‐analysis based on an SBM method are warranted.

Third, considering that extraversion and positive emotionality are two closely related personality constructs (Markon, Krueger, & Watson, 2005; Watson & Clark, 1997) and that positive emotionality has been found to be a superordinate structure of extraversion (Markon et al., 2005), the brain GM correlates of positive emotionality must be investigated in the future to help achieve a better understanding of the neuroanatomical substrates of extraversion. Additionally, future studies examining the impact of neuroticism on the neuroanatomical substrates underlying extraversion are recommended considering that a theoretical anticorrelation may exist between neuroticism and extraversion (Markon et al., 2005); however, only one study in the current meta‐analysis treated neuroticism as a nuisance covariate.

Finally, in the current study, we emphasized three functional neural circuits underlying extraversion. Several studies have adopted fMRI to investigate associations of extraversion with brain activation patterns during social and emotional processing (e.g., Bruhl, Viebke, Baumgartner, Kaffenberger, & Herwig, 2011; Canli, Amin, Haas, Omura, & Constable, 2004; Hooker et al., 2008; Kennis, Rademaker, & Geuze, 2013; Saggar, Vrticka, & Reiss, 2016). Therefore, in future studies, a meta‐analysis of related fMRI studies will be essential to obtain the neurofunctional correlates of extraversion, the findings of which can be compared with our neuroanatomical findings to validate these extraversion‐related functional circuits.

6. CONCLUSION

Taken together, based on a systematic review and meta‐analysis, the current study provided a preliminary brain GM map of extraversion, identified six core regions stably linked to extraversion and showed gender and age effects on extraversion–GMV associations. To our knowledge, this study is the first to reveal a comprehensive picture of brain GM correlates of extraversion. Our study may have educational implications, as the findings may be useful for the selection of targeted brain areas for extraversion interventions. Future studies are encouraged for the development of corresponding training programs (e.g., neurofeedback training, Sitaram et al., 2017) to foster extraversion to help people remain positive, improve sociability, and finally reduce susceptibility to social anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric disorders. Additionally, the current findings may contribute to the development of psychoradiology (https://radiopaedia.org/articles/psychoradiology), which is a new field of radiology with the purpose of not only investigating the abnormal neural mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders, but also being primed to play the clinical role in guiding diagnostic and treatment planning decisions in psychiatric patients (Kressel, 2016; Lui, Zhou, Sweeney, & Gong, 2016; Port, 2018; Sun et al., 2017).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81621003, 81820108018 and 31800963), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (PCSIRT, Grant No. IRT16R52) of China, the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2019M653421), and the Post‐Doctor Interdisciplinary Research Project of Sichuan University. Dr Q.G. would also like to acknowledge the support from his Changjiang Scholar Professorship Award (Award No. T2014190) of China and the American CMB Distinguished Professorship Award (Award No. F510000/G16916411) administered by the Institute of International Education, USA.

Lai H, Wang S, Zhao Y, Zhang L, Yang C, Gong Q. Brain gray matter correlates of extraversion: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of voxel‐based morphometry studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:4038–4057. 10.1002/hbm.24684

Han Lai and Song Wang contributed equally to this study.

Funding information American CMB Distinguished Professorship Award, Grant/Award Number: F510000/G16916411; Changjiang Scholar Professorship Award of China, Grant/Award Number: T2014190; China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: 2019M653421; National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Numbers: 81621003, 81820108018 and 31800963; Post‐Doctor Interdisciplinary Research Project of Sichuan University; Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University, Grant/Award Number: IRT16R52

REFERENCES

- Andari, E. , Schneider, F. C. , Mottolese, R. , Vindras, P. , & Sirigu, A. (2014). Oxytocin's fingerprint in personality traits and regional brain volume. Cerebral Cortex, 24(2), 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik, S. H. , Yoon, H. S. , Kim, S. E. , & Kim, S. H. (2012). Extraversion and striatal dopaminergic receptor availability in young adults: An [18F]fallypride PET study. NeuroReport, 23(4), 251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterink, L. , Yokum, S. , & Stice, E. (2010). Body mass correlates inversely with inhibitory control in response to food among adolescent girls: An fMRI study. NeuroImage, 52(4), 1696–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behroozmand, R. , Shebek, R. , Hansen, D. R. , Oya, H. , Robin, D. A. , Howard, M. A., III , & Greenlee, J. D. (2015). Sensory–motor networks involved in speech production and motor control: An fMRI study. NeuroImage, 109, 418–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict, R. H. , Hussein, S. , Englert, J. , Dwyer, M. G. , Abdelrahman, N. , Cox, J. L. , … Zivadinov, R. (2008). Cortical atrophy and personality in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology, 22(4), 432–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergfield, K. L. , Hanson, K. D. , Chen, K. , Teipel, S. J. , Hampel, H. , Rapoport, S. I. , … Alexander, G. E. (2010). Age‐related networks of regional covariance in MRI gray matter: Reproducible multivariate patterns in healthy aging. NeuroImage, 49(2), 1750–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry, D. S. , & Hansen, J. S. (1996). Positive affect, negative affect, and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(4), 796–809. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler, E. D. , Mortensen, S. , Neeley, E. S. , Ozonoff, S. , Krasny, L. , Johnson, M. , … Lainhart, J. E. (2007). Superior temporal gyrus, language function, and autism. Developmental Neuropsychology, 31(2), 217–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornebekk, A. , Fjell, A. M. , Walhovd, K. B. , Grydeland, H. , Torgersen, S. , & Westlye, L. T. (2013). Neuronal correlates of the five factor model (FFM) of human personality: Multimodal imaging in a large healthy sample. NeuroImage, 65, 194–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore, S. J. , & Choudhury, S. (2006). Development of the adolescent brain: Implications for executive function and social cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 296–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankstein, U. , Chen, J. Y. , Mincic, A. M. , McGrath, P. A. , & Davis, K. D. (2009). The complex minds of teenagers: Neuroanatomy of personality differs between sexes. Neuropsychologia, 47(2), 599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth, T. , Mottus, R. , Corley, J. , Gow, A. J. , Henderson, R. D. , Maniega, S. M. , … Deary, I. J. (2014). Personality, health, and brain integrity: The Lothian birth cohort study 1936. Health Psychology, 33(12), 1477–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora, E. , Fornito, A. , Pantelis, C. , & Yücel, M. (2012). Gray matter abnormalities in major depressive disorder: A meta‐analysis of voxel based morphometry studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 138(1–2), 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhl, A. B. , Viebke, M. C. , Baumgartner, T. , Kaffenberger, T. , & Herwig, U. (2011). Neural correlates of personality dimensions and affective measures during the anticipation of emotional stimuli. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 5(2), 86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli, T. , Amin, Z. , Haas, B. , Omura, K. , & Constable, R. T. (2004). A double dissociation between mood states and personality traits in the anterior cingulate. Behavioral Neuroscience, 118(5), 897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli, T. , Zhao, Z. , Desmond, J. E. , Kang, E. , Gross, J. , & Gabrieli, J. D. (2001). An fMRI study of personality influences on brain reactivity to emotional stimuli. Behavioral Neuroscience, 115(1), 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, S. J. , & Bailey, A. J. (2009). Are there theory of mind regions in the brain? A review of the neuroimaging literature. Human Brain Mapping, 30(8), 2313–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C. S. , & White, T. L. (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Catani, M. , Dell'Acqua, F. , & De Schotten, M. T. (2013). A revised limbic system model for memory, emotion and behaviour. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1724–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, R. B. , Eber, H. W. , & Tatsuoka, M. M. (1970). The handbook for the sixteen personality factor questionnaire. Champaign, IL: Institute for personality and ability testing. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. , & Furnham, A. (2002). Personality, peer relations, and self‐confidence as predictors of happiness and loneliness. Journal of Adolescence, 25(3), 327–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong, T. T.‐J. , Cunnington, R. , Williams, M. A. , Kanwisher, N. , & Mattingley, J. B. (2008). fMRI adaptation reveals mirror neurons in human inferior parietal cortex. Current Biology, 18(20), 1576–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger, C. R. , Przybeck, T. R. , & Svrakic, D. M. (1991). The tridimensional personality questionnaire: US normative data. Psychological Reports, 69(3), 1047–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. X. , Young, J. , Baek, J. M. , Kessler, C. , & Ranganath, C. (2005). Individual differences in extraversion and dopamine genetics predict neural reward responses. Brain Research. Cognitive Brain Research, 25(3), 851–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A. , Gomez, R. , & Aucote, H. (2007). The behavioural inhibition system and behavioural approach system (BIS/BAS) scales: Measurement and structural invariance across adults and adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(2), 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. T. , & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well‐being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(4), 668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. T. , & McCrae, R. R. (1992a). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO personality inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. T. , & McCrae, R. R. (1992b). Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO‐PI‐R) and NEO five‐factor (NEO‐FFI) inventory professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Costafreda, S. G. , Brammer, M. J. , David, A. S. , & Fu, C. H. (2008). Predictors of amygdala activation during the processing of emotional stimuli: A meta‐analysis of 385 PET and fMRI studies. Brain Research Reviews, 58(1), 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, J. F. , Sampaio, A. , Ferreira, M. , Soares, J. M. , & Goncalves, O. F. (2013). Brain correlates of pro‐social personality traits: A voxel‐based morphometry study. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 7(3), 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremers, H. , van Tol, M. J. , Roelofs, K. , Aleman, A. , Zitman, F. G. , van Buchem, M. A. , … van der Wee, N. J. (2011). Extraversion is linked to volume of the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala. PLoS One, 6(12), e28421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David, N. , Bewernick, B. H. , Cohen, M. X. , Newen, A. , Lux, S. , Fink, G. R. , … Vogeley, K. (2006). Neural representations of self versus other: Visual‐spatial perspective taking and agency in a virtual ball‐tossing game. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18(6), 898–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety, J. , & Lamm, C. (2007). The role of the right temporoparietal junction in social interaction: How low‐level computational processes contribute to meta‐cognition. The Neuroscientist, 13(6), 580–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M. R. , Miller, M. M. , Inati, S. , & Phelps, E. A. (2005). An fMRI study of reward‐related probability learning. NeuroImage, 24(3), 862–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNeve, K. M. , & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta‐analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well‐being. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 197–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue, R. A. , & Collins, P. F. (1999). Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22(3), 491–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derntl, B. , Finkelmeyer, A. , Eickhoff, S. , Kellermann, T. , Falkenberg, D. I. , Schneider, F. , & Habel, U. (2010). Multidimensional assessment of empathic abilities: Neural correlates and gender differences. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(1), 67–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, C. G. (2010). Personality neuroscience and the biology of traits. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(12), 1165–1180. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, C. G. , & Gray, J. R. (2009). Personality neuroscience: Explaining individual differences in affect, behavior, and cognition In Corr P. J. & Matthews G. (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personality psychology (pp. 323–346). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, C. G. , Hirsh, J. B. , Shane, M. S. , Papademetris, X. , Rajeevan, N. , & Gray, J. R. (2010). Testing predictions from personality neuroscience: Brain structure and the big five. Psychological Science, 21(6), 820–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M. , Smith, G. D. , Schneider, M. , & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin, A. , Egner, T. , & Kalisch, R. (2011). Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(2), 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin, A. , Egner, T. , & Peraza, D. M. (2006). Resolving emotional conflict: A role for the rostral anterior cingulate cortex in modulating activity in the amygdala. Neuron, 51, 871–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, H. J. (1967). The biological basis of personality. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, H. J. , & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. London, England: Hodder & Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Fassbender, C. , Simoes‐Franklin, C. , Murphy, K. , Hester, R. , Meaney, J. , Robertson, I. , & Garavan, H. (2006). The role of a right fronto‐parietal network in cognitive control. Journal of Psychophysiology, 20(4), 286–296. [Google Scholar]

- Fenker, D. B. , Schott, B. H. , Richardson‐Klavehn, A. , Heinze, H. J. , & Düzel, E. (2005). Recapitulating emotional context: Activity of amygdala, hippocampus and fusiform cortex during recollection and familiarity. European Journal of Neuroscience, 21(7), 1993–1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsman, L. J. , de Manzano, O. , Karabanov, A. , Madison, G. , & Ullen, F. (2012). Differences in regional brain volume related to the extraversion‐introversion dimension‐‐a voxel based morphometry study. Neuroscience Research, 72(1), 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, N. E. , Doyle‐Thomas, K. A. , Tryfon, A. , Ouimet, T. , Anagnostou, E. , Evans, A. C. , … Hyde, K. L. (2015). Structural gray matter differences during childhood development in autism spectrum disorder: A multimetric approach. Pediatric Neurology, 53(4), 350–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan, H. , Ross, T. J. , Murphy, K. , Roche, R. A. , & Stein, E. A. (2002). Dissociable executive functions in the dynamic control of behavior: Inhibition, error detection, and correction. NeuroImage, 17(4), 1820–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan, H. , Ross, T. J. , & Stein, E. A. (1999). Right hemispheric dominance of inhibitory control: An event‐related functional MRI study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96(14), 8301–8306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgio, A. , Santelli, L. , Tomassini, V. , Bosnell, R. , Smith, S. , De Stefano, N. , & Johansen‐Berg, H. (2010). Age‐related changes in grey and white matter structure throughout adulthood. NeuroImage, 51(3), 943–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, N. R. , Drabant, E. M. , & Gross, J. J. (2011). Anterior cingulate cortex volume and emotion regulation: Is bigger better? Biological Psychology, 86(3), 379–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative "description of personality": The big‐five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J. A. (1970). The psychophysiological basis of introversion‐extraversion. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 8(3), 249–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J. C. , Owens, M. M. , Hyatt, C. S. , & Miller, J. D. (2018). No evidence for morphometric associations of the amygdala and hippocampus with the five‐factor model personality traits in relatively healthy young adults. PLoS One, 13(9), e0204011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodin, E. N. , & White, T. L. (2015). The neuroanatomical delineation of agentic and affiliative extraversion. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 15(2), 321–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurrera, R. J. , Nakamura, M. , Kubicki, M. , Dickey, C. C. , Niznikiewicz, M. A. , Voglmaier, M. M. , … Seidman, L. J. (2007). The uncinate fasciculus and extraversion in schizotypal personality disorder: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Schizophrenia Research, 90(1–3), 360–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas, B. W. , Omura, K. , Amin, Z. , Constable, R. T. , & Canli, T. (2006). Functional connectivity with the anterior cingulate is associated with extraversion during the emotional Stroop task. Social Neuroscience, 1(1), 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, J. E. , Boachie, N. , Garcia‐Garcia, I. , Michaud, A. , & Dagher, A. (2018). Neural correlates of dietary self‐control in healthy adults: A meta‐analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Physiology & Behavior, 192, 98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, F. , Koehne, S. , Steinbeis, N. , Dziobek, I. , & Singer, T. (2016). Preserved self‐other distinction during empathy in autism is linked to network integrity of right supramarginal gyrus. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(2), 637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker, C. I. , Verosky, S. C. , Miyakawa, A. , Knight, R. T. , & D'Esposito, M. (2008). The influence of personality on neural mechanisms of observational fear and reward learning. Neuropsychologia, 46(11), 2709–2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X. , Erb, M. , Ackermann, H. , Martin, J. A. , Grodd, W. , & Reiterer, S. M. (2011). Voxel‐based morphometry studies of personality: Issue of statistical model specification‐‐effect of nuisance covariates. NeuroImage, 54(3), 1994–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. , Huimin, Z. , Mengchen, L. , Jinan, W. , Ying, Z. , & Ran, T. (2010). Mental health, personality, and parental rearing styles of adolescents with internet addiction disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 13(4), 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner, E. S. (1991). Correlates of life satisfaction in children. School Psychology Quarterly, 6(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. , Balota, D. A. , & Head, D. (2011). Exploring the relationship between personality and regional brain volume in healthy aging. Neurobiology of Aging, 32(12), 2162–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä, P. , & Isometsä, E. (2006). The relationship of neuroticism and extraversion to symptoms of anxiety and depression in the general population. Depression and Anxiety, 23(5), 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch, R. (2009). The functional neuroanatomy of reappraisal: Time matters. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 33(8), 1215–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapogiannis, D. , Sutin, A. , Davatzikos, C. , Costa, P. , & Resnick, S. (2013). The five factors of personality and regional cortical variability in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Human Brain Mapping, 34(11), 2829–2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley, M. L. , Winocur, G. , Burianova, H. , Hongwanishkul, D. , & Grady, C. L. (2006). Age effects on social cognition: Faces tell a different story. Psychology and Aging, 21(3), 558–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennis, M. , Rademaker, A. R. , & Geuze, E. (2013). Neural correlates of personality: An integrative review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(1), 73–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, L. , & Cahill, L. (2003). Amygdala modulation of parahippocampal and frontal regions during emotionally influenced memory storage. NeuroImage, 20(4), 2091–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. J. , Gee, D. G. , Loucks, R. A. , Davis, F. C. , & Whalen, P. J. (2010). Anxiety dissociates dorsal and ventral medial prefrontal cortex functional connectivity with the amygdala at rest. Cerebral Cortex, 21(7), 1667–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch, S. , Skouras, S. , & Jentschke, S. (2013). Neural correlates of emotional personality: A structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging study. PLoS One, 8(11), e77196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]