Abstract

Pancreatic carcinoma is one of the most malignant diseases and is associated with a poor survival rate. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) is a neuropeptide that acts on three different G protein-coupled receptors: the specific PAC1 and the VPAC1/2 that also bind vasoactive intestinal peptide. PACAP is widely distributed in the body and has diverse physiological effects. Among other things, it acts as a trophic factor and influences proliferation and differentiation of several different cells both under normal circumstances and tumourous transformation. Changes of PACAP and its receptors have been shown in various tumour types. However, it is not known whether PACAP and its specific receptor are altered in pancreatic cancer. Perioperative data of patients with pancreas carcinoma was investigated over a five-year period. Histological results showed Grade 2 or Grade 3 adenocarcinoma in most cases. PACAP and PAC1 receptor expression were investigated by immunohistochemistry. Staining intensity of PAC1 receptor was strong in normal tissues both in the exocrine and endocrine parts of the pancreas, the receptor staining was markedly weaker in the adenocarcinoma. PACAP immunostaining was weak in the exocrine part and very strong in the islets and nerve elements in non-tumourous tissues. The PACAP immunostaining almost disappeared in the adenocarcinoma samples. Based on these findings a decrease or lack of the PAC1 receptor/PACAP signalling might have an influence on tumour growth and/or differentiation.

Keywords: PACAP, PAC1 receptor, pancreas, ductal carcinoma, tumour, expression

Introduction

Pancreas carcinoma is one of the most malignant diseases, associated with late and difficult diagnosis and really short survival after diagnosis. Although in most countries effective radiological and other examination methods can be reached, the early diagnosis of pancreas cancer is difficult (1–4). Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) was first isolated as a hypothalamic neuropeptide acting on the pituitary cAMP release (5,6). The peptide is composed of 38 amino acid residues (PACAP38) and has a shorter form, with only 27 amino acids (PACAP27) (7). Subsequent studies have shown that PACAP is distributed in the entire body, with highest concentrations in the central nervous system and endocrine glands, but it is also present in the cardiovascular, urogenital and gastrointestinal systems (8–13). PACAP has a diverse array of functions via specific PAC1 receptor and VPAC1 and 2 receptors shared with vasoactive intestinal peptide, as well as non-receptorial mechanisms (13,14).

PACAP and its receptors have also been shown in several exocrine glands. The lacrimal gland is innervated by a rich PACAP-ergic fiber plexus (15) and PAC1 receptors are responsible for the activation of tear secretion (16,17). Mammary and salivary glands are also innervated by PACAP-ergic nerves (18–20). In the salivary glands, PACAP induces secretion (21), and enhances protein production while inhibits Ca2+ channels (22–24). The exocrine pancreas is histologically similar to serous salivary glands, and the presence of PACAP has also been shown in the exocrine pancreas, where it stimulates acinar lipase secretion (25). Endocrine pancreas, composed of the islets of Langerhans, expresses very high levels of the peptide, similarly to other endocrine glands. Intrainsular PACAP plays a regulatory role in insulin and glucagon secretion and is implied in glucose homeostasis. Pancreatic PACAP has also been implicated in the regulation of beta cell proliferation (26).

Under pathological conditions, a few studies have dealt with changes in PACAP and receptor expression. Previous studies showed that pancreatic over-expression of PACAP increases in cerulein-induced inflammation leading to acute pancreatitis in a mouse model (27). PACAP, along with its receptors, has been shown to be involved in cell proliferation and differentiation both under normal circumstances and in tumourous transformation (28–33). For some tumour cells, PACAP acts as a growth factor (30), while it inhibits growth of others (34). Whether it stimulates growth of pancreatic tumour cells, it is not known at present, however, a PACAP-response gene associated with proliferation and stress response has been described in pancreatic carcinoma (35). Stimulative role of tumour genesis of PACAP is proven by stimulation of c-Fos as well as c-Jun transcription, and PACAP strongly induces proliferation of the rat pancreatic carcinoma cell line AR4-2J via interaction with the G-protein coupled type 1 PACAP/VIP (PV1) receptor (36). PACAP and PAC1 receptor display specific alterations in several different tumour types, such as thyroid papillary carcinoma and testicular cancer (37,38). It is not known how expression of the peptide and its specific receptor changes in pancreatic cancer. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate whether there is a change in the expression of PACAP and its PAC1 receptor in pancreas adenocarcinoma.

Materials and methods

Patients

A five-year-long period (September 2012-February 2017) was investigated. Preoperative and perioperative data of patients operated in our Department of Surgery because of pancreatic ductal carcinoma were collected. Operation type as well as histological findings, grading, and margin resection were investigated from the pathological tissue samples after diagnosis and treatments had been made (Ethical permission number: PTE/83069/2018).

Histology and immunhistology

After data collection new histological sections were made and prepared for further specific histological examination of PACAP and PAC1 receptor expression. Two-µm-thick paraffin sections fixed in 4% buffered formalin were processed for immunohistochemical staining. Sections were stained using standard immunohistochemistry with human anti-PACAP antibody (dilution of 1:200; Peninsula, CA, USA) and with human PAC1 receptor antibody raised in rabbit (dilution of 1:200; Sigma-Aldrich, Budapest, Hungary). Immunohistochemical staining was performed with EnVision FLEX Visualization Systems for Dako Omins (Dako, Denmark), similarly to our earlier descriptions (37). Liquid fast-red substrate kit (Abcam, UK) was used as a chromogen for the immunohistochemical staining. Pathological analysis was performed by an expert pathologist, using a semi-quantitative approach to evaluate the immunohistochemical staining intensity between no staining, weak, medium and strong staining. By omitting the primary antiserum, we performed a method control, which resulted in no staining. Well-identified structures, like insular cells, nerve elements of the myenteric plexus and intramural ganglia, served as positive control, as both PACAP and PAC1 receptor are known to be expressed in the insula and PACAP has been described in the nerve elements. Tumour cell staining intensity was compared to that of tumour-free tissue in the same pancreas tissue in a semi-quantitative way.

Results

Clinical data

Data of 19 patients (7 male, 12 female) were chosen to be investigated (mean age were 69.6 years; 54 to 74 years). Seven patients had Grade 2, 13 patients Grade 3 adenocarcinoma in the pancreas head, with icterus and significant weight loss. Five patients were operated by conventional Whipple operation, 14 patients underwent pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPD). In every case operation was followed by a three-day-long Intensive Care Unit (ICU) observation. After ICU observation and further care in normal surgery unit all patients were emitted. The histological result of the resected pancreas tissue showed Grade 2 adenocarcinoma in 11 patients, Grade 3 adenocarcinoma in 7 cases, and mucinous adenocarcinoma in 1 patient. Tumour staging in all cases was pT3. Lymph node staging was N0 in 5 cases, the other specimens showed N1 stage. Resection margin was not affected (R0 resection) in 9 cases, samples from 7 patients showed narrow resection margin, 1 sample showed perineural invasion on ductus choledochus, another sample showed tumour cell infiltration on the wall of veins. In case of one patient, the tumour involved the common hepatic artery and portal vein (R2 resection).

Histology and immunhistology

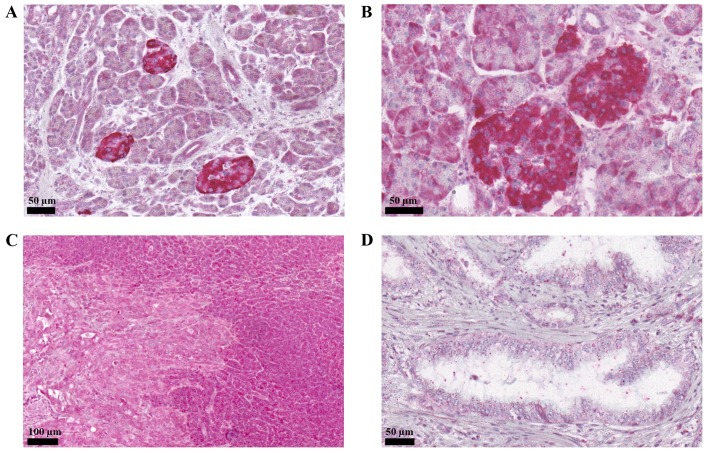

The immunohistochemical staining showed that PAC1 was expressed in both the exocrine and endocrine parts of the pancreas, in accordance with earlier descriptions. We also confirmed the particularly strong staining of the pancreatic islets (Fig. 1A and B). In the adenocarcinoma, receptor staining was markedly weaker. In tissue samples, the border between tumourous and normal pancreas was also shown by the different staining intensity for the PAC1 receptor (Fig. 1C and D). Nerve elements did not show receptor positivity.

Figure 1.

PAC1 receptor immunostaining in normal pancreas and ductal adenocarcinomas. (A and B) Strong staining of the pancreatic islets was observed. In the adenocarcinoma, receptor staining was markedly weaker (left side of C, and D). (C) The border between tumourous and normal pancreas was also shown by the different staining intensity for the PAC1 receptor.

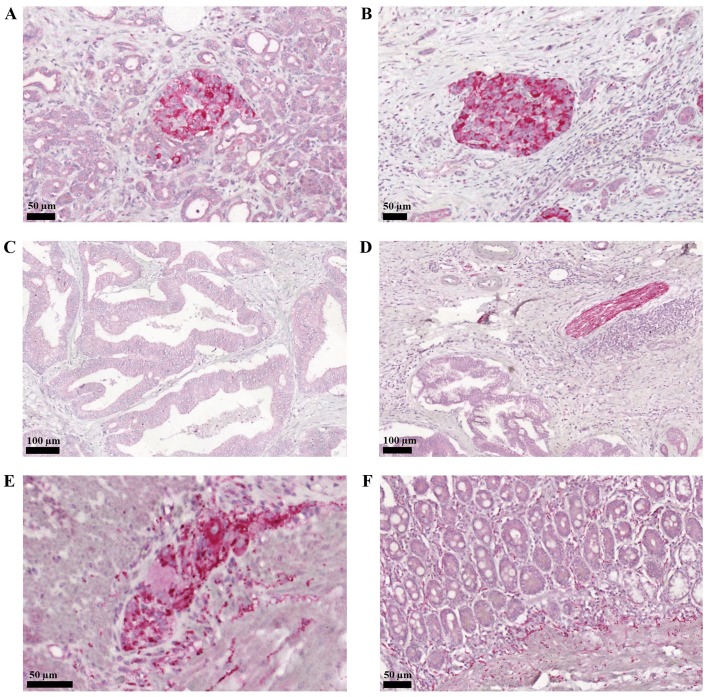

PACAP staining, on the other hand, was weaker in the exocrine part, and again very strong in the endocrine islets (Fig. 2A and B). Similarly to the PAC1 receptor staining, PACAP expression was also weaker in the adenocarcinoma parts of the tissue samples (Fig. 2C). Neither PACAP nor PAC1 receptor expression showed correlation with the tumour outcome. In contrast to the absence of PAC1 receptor, PACAP was also expressed in the intrapancreatic nerves (Fig. 2D) and ganglionic cells (Fig. 2E and H). Following Whipple operation, resected parts of the duodenum were also examined. We could confirm earlier descriptions regarding the presence of PACAP and its specific receptor in the duodenum. Myenteric and submucosal plexi were strongly stained for PACAP, including inter- and intramuscular as well as lamina propria nerve fibers and ganglionic cells in the myenteric plexus (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

PACAP immunostaining in normal pancreas and ductal adenocarcinomas. (A and B) Strong staining was observed in the endocrine islets. (C) PACAP expression was weaker in the adenocarcinoma parts of the tissue samples. PACAP was also expressed in the (D) intrapancreatic nerves and (E) ganglionic cells. (F) Duodenal lamina propria nerve fibers also stained for PACAP.

Discussion

In the present study we analysed normal and tumourous pancreas tissues within the same samples for PACAP and PAC1 receptor immunostaining. We observed a diminished expression for both the peptide and its specific receptor in the adenocarcinoma compared to the normal tissue, independent from tumour grade.

Several growth factors play an important role in pancreatic organogenesis and are also involved later in tumourgenesis. Among others, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) has been shown to be involved in the regulation of tumourous cell growth and differentiation in the pancreas (39). FGF receptor IIIb and IIIc play critical roles in the epithelio-mesenchymal transition in spite of no expression in the ductal cells but showing very high expression levels in the islets (40,41). It has been demonstrated that increased nerve growth factor (NGF) expression correlates with poorer prognosis, increased inflammation and pain (42). The involvement of transforming growth factor beta (TGF beta) is unquestionable in tumour growth, including that of the pancreas (43). Overexpression of epidermal growth factor (EGF) occurs in the majority of ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas and is associated with poorer prognosis (44–46). The increased insulin-like growth factor expression has been found to be correlated with increased risk of pancreatic cancer (47). There is a continuous, urgent need for novel diagnostic markers for pancreatic cancer (48). The currently available markers have low sensitivity and specificity. Personalized treatment approaches call for more prognostic and treatment-predictive biomarkers (48–50).

PACAP, as a growth factor, plays an important role in the development of the nervous system and several peripheral organs (51–53). It is not surprising, therefore, that certain tumour types also express alterations in PACAP and/or receptor expression. Certain tumours show overexpression of the PACAP-ergic system, while others lack PACAP signalling. In vitro studies have demonstrated that PACAP is able to stimulate or inhibit tumour growth, depending on various factors, such as tumour type, differentiation stage, origin or environmental circumstances (54). For example, PACAP inhibits cell survival in retinoblastoma cells (34), reduces invasiveness in glioblastoma cells (55) and inhibits tumour growth in cervical carcinoma (56). On the other hand, it stimulates cell proliferation in an osteosarcoma cell line (57) and increases the number of viable cells in a colon tumour cell line (58). Even within the same cell line, different effects can be observed depending on exposure time, concentration and other circumstances. This dual effect has been described in a prostate cancer cell line, where short exposure to PACAP induces cell proliferation, while long-term exposure induces proliferation arrest (59). In a human retinoblastoma cell line, nanomolar concentrations of PACAP do not affect cell viability, while higher concentrations decrease cell survival (34).

PACAP/VIP receptors are known to play a leading role in cancer genesis and the VIP/PACAP receptors are expressed in the most frequently occurring human tumours (breast, prostate, ductal carcinoma of the pancreas, lung, colon, stomach, liver, and urinary bladder, lymphomas and meningioma). In these cases the receptors are predominantly VPAC1 type. On the other hand leiomyomas predominantly express VPAC2 receptors, whereas paraganglioma, pheochromocytoma, and endometrial carcinomas preferentially express PAC1 receptors (60). Recent studies have shown that VIP/PACAP-receptor expression can be found in only 65% of pancreatic ductal carcinomas (30). Both VPAC1 and 2 receptors have been identified in pancreatic tumour samples (30). Overexpression of these receptors (61) explains the attempts for the clinical use of radiolabelled VIP-analogues in various cancer types, including pancreas adenocarcinoma (30,62,63). However, contradictory data have also been published, as according to the observations of Hessenius and coworkers (62), no imaging was seen with radiolabeled-VIP-analogues in pancreatic cancer patients, and in vitro binding studies in these tumours did not confirm overexpression of VPAC1. We found PAC1 receptor expression in the exocrine pancreas in nearly all cases, but very weak expression in the tumourous parts. Changes in PACAP expression have been shown in a few tumours by radioimmunoassay and immunohistochemistry (64). In earlier studies, we described lower PACAP tissue levels in lung, kidney and colon cancer, but higher levels in prostate cancer (64,65). A changed staining pattern has been described in different human testicular cancers (38) and in human thyroid papillary carcinoma (37). In the present study we observed that PACAP expression was weak in normal tissues in the exocrine pancreas, and nearly absent in the adenocarcinoma parts of the tissue samples. The limitation of our study is that we cannot draw final conclusion at the moment whether the reduction of PACAP and PAC1 receptor expression is a consequence of the adenocarcinoma development or the reduced PACAP signaling plays a role in pancreatic carcinogenesis. This should be further explored in future studies.

In summary, we found that both PACAP and PAC1 receptor expression is markedly decreased in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tissue samples, while staining remained strong in the endocrine islets. This suggests that decrease or lack of the PAC1 receptor/PACAP signalling may contribute to tumour growth and/or differentiation, details of which must be further explored.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the following grants (grant nos. GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00050 ‘PEPSYS’, MTA-TKI14016; NKFIH K119759, Bolyai Scholarship, EFOP-3.6.3-VEKOP-16-2017-00009, EFOP-3.6.1.-16-2016-00004 Comprehensive Development for Implementing Smart Specialization Strategies at the University of Pécs; New Excellence Program, UNKP-16-4-IV, TAMOP 4.2.4.A/2-11-1-2012-0001, EFOP-3.6.2-VEKOP-16-15 2017-00008, ‘The role of neuro-inflammation in neurodegeneration: from molecules to clinics’, and Higher Education Institutional Excellence Programme of the Ministry of Human Capacities in Hungary, within the framework of the 20765-3/2018/FEKUTSTRAT FIKPII; NAP2017-1.2.1-NKP-2017-00002).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

The patients' data collection was performed by SF, ZV, VV, OK and DK. The histological sections were produced by BK, which were subsequently stained and examined by DR, OK, DT and AB. Figures were produced by DT. The manuscript was written by SF, DR, OK and DK.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Data collection was permitted by Local Ethic Committee of University Pecs (use of patient data system of the Clinical Centre of University Pecs) (Permission number PTE/83069/2018).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Research UK, corp-author. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/pancreatic-cancer. [Mar 21;2019 ];

- 2.Klaiber U, Leonhardt CS, Strobel O, Tjaden C, Hackert T, Neoptolemos JP. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2018;403:917–932. doi: 10.1007/s00423-018-1724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling S, Feng T, Jia K, Tian Y, Li Y. Inflammation to cancer: The molecular biology in the pancreas (Review) Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1747–1754. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frampas E, David A, Regenet N, Touchefeu Y, Meyer J, Merla O. Pancreatic carcinoma: Key-points from diagnosis to treatment. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016;97:1207–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirabayashi T, Nakamachi T, Shioda S. Discovery of PACAP and its receptors in the brain. J Headache Pain. 2018;19:28. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0855-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyata A, Arimura A, Dahl RR, Minamino N, Uehara A, Jiang L, Culler MD, Coy DH. Isolation of a novel 38 residue-hypothalamic polypeptide which stimulates adenylate cyclase in pituitary cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;164:567–574. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(89)91757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyata A, Jiang L, Dahl RD, Kitada C, Kubo K, Fujino M, Minamino N, Arimura A. Isolation of a neuropeptide corresponding to the N-terminal 27 residues of the pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide with 38 residues (PACAP38) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;170:643–648. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(90)92140-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ojala J, Tooke K, Hsiang H, Girard BM, May V, Vizzard MA. PACAP/PAC1 expression and function in micturition pathways. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;68:357–367. doi: 10.1007/s12031-018-1170-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reglodi D, Illes A, Opper B, Schafer E, Tamas A, Horvath G. Presence and effects of pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide under physiological and pathological conditions in the stomach. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:90. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lajko A, Meggyes M, Fulop BD, Gede N, Reglodi D, Szereday L. Comparative analysis of decidual and peripheral immune cells and immune-checkpoint molecules during pregnancy in wild-type and PACAP-deficient mice. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2018;80:e13035. doi: 10.1111/aji.13035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons RL, May V. PACAP-induced PAC1 receptor internalization and recruitment of endosomal signaling regulate cardiac neuron excitability. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;68:340–347. doi: 10.1007/s12031-018-1127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarszegi Z, Szabo D, Gaszner B, Konyi A, Reglodi D, Nemeth J, Lelesz B, Polgar B, Jungling A, Tamas A. Examination of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) as a potential biomarker in heart failure patients. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;68:368–376. doi: 10.1007/s12031-017-1025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reglodi D, Tamas A, editors. Curr Topics Neurotox Springer Int. Switzerland: 2016. Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase Activating Polypeptide-PACAP; pp. 1–840. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaudry D, Falluel-Morel A, Bourgault S, Basille M, Burel D, Wurtz O, Fournier A, Chow BK, Hashimoto H, Galas L, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: 20 years after the discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:283–357. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elsås T, Uddman R, Sundler F. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide-immunoreactive nerve fibers in the cat eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1996;234:573–580. doi: 10.1007/BF00448802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaal V, Mark L, Kiss P, Kustos I, Tamas A, Kocsis B, Lubics A, Nemeth V, Nemeth A, Lujber L, et al. Investigation of the effects of PACAP on the composition of tear and endolymph proteins. J Mol Neurosci. 2008;36:321–329. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamachi T, Ohtaki H, Seki T, Yofu S, Kagami N, Hashimoto H, Shintani N, Baba A, Mark L, Lanekoff I, et al. PACAP suppresses dry eye signs by stimulating tear secretion. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12034. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen AM, Dissing S, Fahrenkrug J, Hannibal J, Reibel J, Nauntofte B. Innervation pattern and Ca2+ signalling in labial salivary glands of healthy individuals and patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) J Oral Pathol Med. 2000;29:97–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.290301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skakkebaek M, Hannibal J, Fahrenkrug J. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the rat mammary gland. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;298:153–159. doi: 10.1007/s004419900086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobin G, Asztély A, Edwards AV, Ekström J, Håkanson R, Sundler F. Presence and effects of pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide in the submandibular gland of the ferret. Neuroscience. 1995;66:227–235. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00622-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matoba Y, Nonaka N, Takagi Y, Imamura E, Narukawa M, Nakamachi T, Shioda S, Banks WA, Nakamura M. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide enhances saliva secretion via direct binding to PACAP receptors of major salivary glands in mice. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2016;299:1293–1299. doi: 10.1002/ar.23388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calvert PA, Heck PM, Edwards AV. Autonomic control of submandibular protein secretion in the anaesthetized calf. Exp Physiol. 1998;83:545–556. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamaishi H, Endoh T, Suzuki T. Multiple signal pathways coupling VIP and PACAP receptors to calcium channels in hamster submandibular ganglion neurons. Auton Neurosci. 2004;111:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirfendereski S, Tobin G, Håkanson R, Ekström J. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide (PACAP) in salivary glands of the rat: Origin, and secretory and vascular effects. Acta Physiol Scand. 1997;160:15–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1997.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt WE, Seebeck J, Höcker M, Schwarzhoff R, Schäfer H, Fornefeld H, Morys-Wortmann C, Fölsch UR, Creutzfeldt W. PACAP and VIP stimulate enzyme secretion in rat pancreatic acini via interaction with VIP/PACAP-2 receptors: Additive augmentation of CCK/carbachol-induced enzyme release. Pancreas. 1993;8:476–487. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199307000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakurai Y, Shintani N, Hayata A, Hashimoto H, Baba A. Trophic effects of PACAP on pancreatic islets: A mini-review. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;43:3–7. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9424-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamagami K, Sakurai Y, Shintani N, Higuchi N, Ikeda K, Hashimoto H, Suzuki A, Kiyama H, Baba A. Over-expression of pancreatic pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) aggravates cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;110:451–458. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09119FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung S, Yi L, Jeong D, Kim J, An S, Oh TJ, Kim CH, Kim CJ, Yang Y, Kim KI, Lim JS, Lee MS. The role of ADCYAP1, adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide, as a methylation biomarker for the early detection of cervical cancer. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:245–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moody TW, Chan D, Fahrenkrug J, Jensen RT. Neuropeptides as autocrine growth factors in cancer cells. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:495–509. doi: 10.2174/1381612033391621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moody TW, Nuche-Berenguer B, Jensen RT. Vasoactive intestinal peptide/pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide, and their receptors and cancer. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:38–47. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moody TW, Jensen RT. PACAP and cancer. In: Reglodi D, Tamas A, editors. Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase Activating Polypeptide-PACAP. Springer Int.; Switzerland: 2016. pp. 795–814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz S, Röcken C, Mawrin C, Weise W, Höllt V, Schulz S. Immunocytochemical identification of VPAC1, VPAC2, and PAC1 receptors in normal and neoplastic human tissues with subtype-specific antibodies. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8235–8242. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulz S, Mann A, Novakhov B, Piggins HD, Lupp A. VPAC2 receptor expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues: Evaluation of the novel MAB SP235. Endocr Connect. 2015;4:18–26. doi: 10.1530/EC-14-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wojcieszak J, Zawilska JB. PACAP38 and PACAP6-38 exert cytotoxic activity against human retinoblastoma Y79 cells. J Mol Neurosci. 2014;54:463–468. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0248-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schäfer H, Lettau P, Trauzold A, Banasch M, Schmidt WE. Human PACAP response gene 1 (p22/PRG1): Proliferation-associated expression in pancreatic carcinoma cells. Pancreas. 1999;18:378–384. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schäfer H, Zheng J, Gundlach F, Günther R, Schmidt WE. PACAP stimulates transcription of c-Fos and c-Jun and activates the AP-1 transcription factor in rat pancreatic carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;221:111–116. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bardosi S, Bardosi A, Nagy Z, Reglodi D. Expression of PACAP and PAC1 receptor in normal human thyroid gland and in thyroid papillary carcinoma. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;60:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s12031-016-0823-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura K, Nakamachi T, Endo K, Ito K, Machida T, Oka T, Hori M, Ishizaka K, Shioda S. Distribution of pituitary adenilate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the human testis and in testicular germ cell tumours. Andrologia. 2014;46:465–471. doi: 10.1111/and.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ndlovu R, Deng LC, Wu J, Li XK, Zhang JS. Fibroblast growth factor 10 in pancreas development and pancreatic cancer. Front Genet. 2018;9:482. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishiwata T. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptor-2 splicing in normal and cancer cells. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2018;23:626–639. doi: 10.2741/4609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu G, Xiong D, Xiao R, Huang Z. Prognostic role of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 in human solid tumours: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317707424. doi: 10.1177/1010428317707424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saloman JL, Singhi AD, Hartman DJ, Normolle DP, Albers KM, Davis BM. Systemic depletion of nerve growth factor inhibits disease progression in a genetically engineered model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2018;47:856–863. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melzer C, Hass R, von der Ohe J, Lehnert H, Ungefroren H. The role of TGF-β and its crosstalk with RAC1/RAC1b signaling in breast and pancreas carcinoma. Cell Commun Signal. 2107;15:19. doi: 10.1186/s12964-017-0175-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiramel J, Backen AC, Pihlak R, Lamarca A, Frizziero M, Tariq NU, Hubner RA, Valle JW, Amir E, McNamara MG. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor in addition to chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E909. doi: 10.3390/ijms18050909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiss GA, Rossi MR, Khushalani NI, Lo K, Gibbs JF, Bharthuar A, Cowell JK, Iyer R. Evaluation of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase catalytic subunit (PIK3CA) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene mutations in pancreaticobiliary adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Onco. 2013;4:20–29. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luo G, Long J, Qiu L, Liu C, Xu J, Yu X. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor expression on patient survival in pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2011;11:595–600. doi: 10.1159/000334465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gong Y, Zhang B, Liao Y, Tang Y, Mai C, Chen T, Tang H. Serum insulin-like growth factor axis and the risk of pancreatic cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9:E394. doi: 10.3390/nu9040394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loosen SH, Neumann UP, Trautwein C, Roderburg C, Luedde T. Current and future biomarkers for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317692231. doi: 10.1177/1010428317692231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamaoka T, Ohba M, Ohmori T. Molecular-targeted therapies for epidermal growth factor receptor and its resistance mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E2420. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le N, Sund M, Vinci A, GEMS collaborating group of Pancreas 2000 Prognostic and predictive markers in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fulop BD, Sandor B, Szentleleky E, Karanyicz E, Reglodi D, Gaszner B, Zakany R, Hashimoto H, Juhasz T, Tamas A. Altered notch signaling in developing molar teeth of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)-deficient mice. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;68:377–388. doi: 10.1007/s12031-018-1146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu Z, Ohtaki H, Watanabe J, Miyamoto K, Murai N, Sasaki S, Matsumoto M, Hashimoto H, Hiraizumi Y, Numazawa S, Shioda S. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) contributes to the proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells in murine bone marrow via PACAP-specific receptor. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22373. doi: 10.1038/srep22373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandor B, Fintor K, Reglodi D, Fulop DB, Helyes Z, Szanto I, Nagy P, Hashimoto H, Tamas A. Structural and morphometric comparison of lower incisors in PACAP-deficient and wild-type mice. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;59:300–308. doi: 10.1007/s12031-016-0765-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zibara K, Zeidan A, Mallah K, Kassem N, Awad A, Mazurier F, Badran B, El-Zein N. Signaling pathways activated by PACAP in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2018;50:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maugeri G, D'Amico AG, Reitano R, Magro G, Cavallaro S, Salomone S, D'Agata V. PACAP and VIP inhibit the invasiveness of glioblastoma cells exposed to hypoxia through the regulation of HIFs and EGFR expression. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:139. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee JH, Lee JY, Rho SB, Choi JS, Lee DG, An S, Oh T, Choi DC, Lee SH. PACAP inhibits tumour growth and interferes with clusterin in cervical carcinomas. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4730–4739. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Juhász T, Matta C, Katona É, Somogyi C, Takács R, Hajdú T, Helgadottir SL, Fodor J, Csernoch L, Tóth G, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) signalling enhances osteogenesis in UMR-106 cell line. J Mol Neurosci. 2014;54:555–573. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Le SV, Yamaguchi DJ, McArdle CA, Tachiki K, Pisegna JR, Germano P. PAC1 and PACAP expression, signaling, and effect on the growth of HCT8, human colonic tumour cells. Regul Pept. 2002;109:115–125. doi: 10.1016/S0167-0115(02)00194-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farini D, Puglianiello A, Mammi C, Siracusa G, Moretti C. Dual effect of pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide on prostate tumour LNCaP cells: Short- and long-term exposure affect proliferation and neuroendocrine differentiation. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1631–1643. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reubi JC, Läderach U, Waser B, Gebbers JO, Robberecht P, Laissue JA. Vasoactive intestinal peptide/pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide receptor subtypes in human tumours and their tissues of origin. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3105–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hessenius C, Bäder M, Meinhold H, Böhmig M, Faiss S, Reubi JC, Wiedenmann B. Vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor scintigraphy in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinomas or neuroendocrine tumours. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:1684–1693. doi: 10.1007/s002590000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raderer M, Kurtaran A, Yang Q, Meghdadi S, Vorbeck F, Hejna M, Angelberger P, Kornek G, Pidlich J, Scheithauer W, Virgolini I. Iodine-123-vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor scanning in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:1570–1575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang C, Biemond I, Offerhaus GJ, Verspaget W, Lamers CB. Expression of receptors for gut peptides in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma and tumour-free pancreas. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tamas A, Javorhazy A, Reglodi D, Sarlos DP, Banyai D, Semjen D, Nemeth J, Lelesz B, Fulop DB, Szanto Z. Examination of PACAP-like immunoreactivity in urogenital tumour samples. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;59:177–183. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Szanto Z, Sarszegi Z, Reglodi D, Nemeth J, Szabadfi K, Kiss P, Varga A, Banki E, Csanaky K, Gaszner B, et al. PACAP immunoreactivity in human malignant tumour samples and cardiac diseases. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;48:667–673. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9815-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.