Abstract

Breastfeeding has known positive health benefits for babies and mothers, yet the UK has one of the lowest breastfeeding initiation rates in Europe. Despite national guidance that recommends provision of breastfeeding peer support, there is conflicting evidence regarding its effectiveness, especially in high‐income countries, and a lack of evidence among young mothers. This study evaluates the effectiveness of a breastfeeding peer support service (BPSS) in one UK city in increasing breastfeeding initiation and duration in young mothers. Routinely collected data were obtained on feeding method at birth, 2 and 6 weeks for all 5790 women aged <25 registered with a local general practitioner and who gave birth from April 2009 to September 2013. Segmented regression was used to quantify the impact of the introduction of the BPSS in September 2012 on the prevalence of breastfeeding at birth, 2 and 6 weeks, accounting for underlying trends. Results showed that breastfeeding prevalence at birth and 2 weeks began to increase month‐on‐month after the introduction of the BPSS, where previous figures had been static; prevalence at birth increased by 0.55 percentage points per month (95% CI 0.10–1.00, P = 0.018) and at 2 weeks by 0.50 percentage points (95% CI 0.15–0.86, P = 0.007). There was no change from an underlying marginally increasing trend in prevalence at 6 weeks. In conclusion, our findings suggest that a one‐to‐one BPSS provided by paid peer supporters and targeted at young mothers in the antenatal and post‐natal periods may be beneficial in increasing breastfeeding initiation and prevalence at 2 weeks.

Keywords: breastfeeding, peer support, health promotion, time series

Introduction

Breastfeeding promotes and protects the health of infants and mothers (Horta et al. 2007; Ip et al. 2007), and exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for the first 6 months of an infant's life (World Health Organisation 2003). Studies have also shown an association between breastfeeding and improved cognitive development and academic attainment in later childhood (Horta et al. 2007; Victora et al. 2015). A recent review concluded that investments into evidence‐based breastfeeding interventions could see a return on investment in as little as 1 year (Renfrew et al. 2012a).

Many European countries including Sweden, Norway and Denmark have breastfeeding initiation rates between 90% and 100% (Organisation for Economic Co‐Operation and Development 2009) compared with just 73.9% in England (Department of Health 2013). Just over a third of mothers in England are still breastfeeding at 6 months with the greatest drop in prevalence occurring during the first 2 weeks following birth (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2012a). Factors positively associated with breastfeeding prevalence at 6 weeks in the UK Infant Feeding Survey include being of non‐White ethnicity, being aged 30 or more and being a mother from a managerial or professional occupation (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2012b). Common reasons that mothers give for stopping breastfeeding during the first 2 weeks post‐partum include the baby not sucking and painful nipples (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2012a); these issues are likely to be due to poor positioning and attachment to the breast. Among teenage mothers, negative moral norms about breastfeeding and embarrassment of breastfeeding in public are key barriers to breastfeeding (Ingram et al. 2008; Dyson et al. 2010).

Improving breastfeeding rates is a national priority in the UK (Department of Health 2012), and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance recommends breastfeeding peer support (BPS) as an effective intervention for achieving this (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2008). BPS is defined as support with breastfeeding that is provided by trained peers rather than a health professional. The peer supporter is usually from the same area and/or socio‐economic background as the new mother and has breastfed herself (Dyson et al. 2005). Despite this recommendation to provide BPS, there is conflicting evidence regarding the effectiveness of the intervention and a lack of evidence for those women least likely to breastfeed, including young mothers (Britton et al. 2007).

A Cochrane systematic review found that mothers who received BPS were significantly less likely to stop breastfeeding before 6 months than those who had not received this intervention (Renfrew et al. 2012b); however, more than half of the studies included in this review were judged as having a high risk of bias because of inadequate or lack of blinding. A second systematic review and meta‐analysis concluded that although BPS increased duration of breastfeeding in low‐income or middle‐income countries, it had no significant impact in high‐income countries, including the UK (Jolly et al. 2012). However, the authors acknowledged that the effect of high‐intensity BPS (defined as five or more contacts) in the UK is unknown. The majority of published evaluations of BPS have been conducted in North America (Arlotti et al. 1998; Martens 2002; Kruske et al. 2007) so findings may not be transferable to the UK because of differences in what constitutes routine maternal care. An evaluation of BPS in Glasgow, Scotland found that women who had received support were almost twice as likely to breastfeed than those who did not receive support (McInnes et al. 2000). Other BPS evaluations undertaken within the UK generally conclude that BPS is beneficial, although sample sizes are small (Alexander et al. 2003; Ingram et al. 2005; Ingram 2013).

The breastfeeding peer support service (BPSS) evaluated here launched in September 2012. The service serves an urban city, which is the 20th most deprived authority in England (Nottingham Insight 2014), where 68.9% of babies are breastfed at birth, lower than the England average of 73.9% (Department of Health 2013). In 2012/2013, the prevalence of breastfeeding at 6 weeks among Nottingham mothers was 46.4% (Department of Health 2013). Similar to the pattern seen nationally, younger mothers resident in this city are less likely to breastfeed than their older counterparts (Nottingham Insight 2012). The BPSS therefore targets young mothers less than 25 years of age, which distinguishes it from other interventions previously evaluated. The underlying philosophy of the service model is based on the social cognitive theory in that it aims to influence breastfeeding self‐efficacy through empowerment, role modelling and positive reinforcement (Bandura 2001). In order to be influential role models, peer supporters are recruited from and reflect the diversity of the community in which they work; they are women who have previously breastfed themselves. The supporters receive externally accredited BPS training prior to supporting women. Paid peer supporters offer intensive one‐to‐one support from 30–34 weeks gestation until 6 weeks post‐partum, with the highest intensity of support provided during the 2 weeks following birth (Fig. 1). Other characteristics of the Nottingham BPSS include the following: proactively contacting all eligible women; offering a home visit to new mothers within 24–48 h of their transfer home; offering ongoing, responsive support (face to face or telephone) according to women's individual needs; peer supporters having regular supervision and access to a health professional for consultation; integration with midwifery, health visiting and children's centres.

Figure 1.

An illustration of key contacts with pregnant and new mothers aged <25 provided by the breastfeeding peer support service.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the Nottingham BPSS in increasing breastfeeding initiation and duration in mothers under 25 years of age.

Key messages.

Increasing maternal age is positively associated with breastfeeding in the UK. BPS is recommended in national guidance. However, there is conflicting evidence on its effectiveness, particularly in high income countries, and a lack of evidence among mothers aged <25. Our time series analysis of routinely‐collected service monitoring data suggests that one‐to‐one BPS provided by paid peer supporters to mothers aged <25 may be beneficial in increasing breastfeeding initiation and breastfeeding at 2 weeks. Further analysis, potentially including a randomised controlled trial of the intervention, is now recommended.

Methods

Data sources

Data from the Nottingham Child Health Information System (routine data collected by the service provider) were obtained. This dataset comprised information for all women aged <25 years at the date of delivery registered with a Nottingham general practitioner who gave birth to a live baby from 1 April 2009 until 30 September 2013, with recorded data on feeding method at birth, 2 and 6 weeks. Health visitors collected data on infant feeding at birth by asking mothers retrospectively during a post‐natal home visit at 2 weeks post‐partum. Infant feeding data at 2 and 6 weeks were gathered from health visitor observation at the routine 2 and 6 week home visits.

Since 2008, all primary care trusts in England and now child health information system providers have been required to submit quarterly data on breastfeeding prevalence at 6 weeks to the Department of Health as part of the Vital Sign Monitoring Return (Department of Health 2013). These data have to meet quality assurance criteria, and validation checks are conducted. Nottingham data have consistently met these standards.

The primary outcome measures were breastfeeding prevalence at birth, 2 and 6 weeks post‐partum. As the aim of the BPSS is to increase any breastfeeding, outcome measures focus on this rather than on exclusive breastfeeding. A small amount of feeding data at birth, 2 and 6 weeks were missing (3.9%, 3.7% and 0.1%, respectively). Some of these missing values were imputed when there was high confidence in what those data were. For example, if a mother was breastfeeding at birth and 6 weeks but data were missing for 2 weeks, then it was assumed that she was breastfeeding at 2 weeks. Prior to September 2010, if an infant was fed any breast milk, then data were recorded as ‘Breast/Breast and Bottle’. This changed in September 2010, so that three feeding options were recorded (‘Breast’, ‘Bottle’ or ‘Mixed’). Thus, data that were recorded as either ‘Breast/Breast and Bottle’ or ‘mixed’ were replaced with ‘Breast’, as these infants were receiving some breast milk. This was deemed appropriate given the focus on any breastfeeding rather than exclusive breastfeeding. This variable was then converted to a binary variable in which ‘Breast’ was coded as ‘1’ and ‘Bottle’ as ‘0’. Breastfeeding prevalence was calculated for each feeding outcome at each month during the study period.

All data were anonymised by the service provider prior to transferring to the authors for analysis. The study was approved by the service provider's Information Governance Department and the University of Nottingham's Division of Epidemiology and Public Health Research Ethics Committee.

Statistical analyses

Following recognised procedures (Wagner et al. 2002; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group 2013), interrupted time series models using segmented regression were built for each of the three primary outcomes to quantify any immediate increase or decrease, or change in trend, in breastfeeding prevalence at the point the BPSS was introduced relative to beforehand, while controlling for the pre‐intervention trend and any underlying seasonal pattern. As the BPSS launched in September 2012, the start of October 2012 was considered to be the appropriate change point in the time series. This allowed 1 month for the service to start becoming embedded before we expected to see any changes in infant feeding outcomes.

A backward regression procedure using the likelihood ratio test was used to build a parsimonious model containing only parameters with statistically significant P‐values (<0.05) to ensure non‐significant variables were not impacting on the magnitude and significance of other variables in the model. Examination of the autocorrelation function of model residuals showed that autocorrelation had been adequately modelled in the data.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to verify that the imputation of some outcome data, as described earlier, had not altered the findings. Segmented regression analysis was conducted for each outcome using the original data prior to imputation. The results using the non‐imputed data were compared with the results when imputed data were used. The sensitivity analyses showed no difference in the findings and so, for conciseness, these results have not been presented.

All analyses were completed using STATA version 12.0 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Three hundred forty‐five women accessed the BPSS between October 2012 and September 2013, 29% of the eligible population. Access steadily increased throughout the study period from 4% of the eligible population in October 2012 to 61% by September 2013. The median number of contacts per client was six [Interquartile range (IQR) 3–9]. Table 1 details the characteristics of all women in the target age group during the study period (October 2009 to September 2013) and also those who accessed the BPSS after its introduction in October 2012.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all mothers aged <25 who gave birth to a live infant and those who accessed the BPSS

| Women who accessed the BPSS (October 2012–September 2013) n = 345 | All women who gave birth (April 2009–September 2013) n = 5790 | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Number (%) or median (IQR) | Number (%) or median (IQR) |

| Age | 23 (21–24) | 22 (20–23) |

| Deprivation | ||

| Quintile 1 (most deprived) | 234 (67.8) | 4189 (72.3) |

| Quintile 2 | 69 (20.0) | 1142 (19.7) |

| Quintile 3 | 22 (6.4) | 324 (5.6%) |

| Quintile 4 | 12 (3.5) | 82 (1.4) |

| Quintile 5 | 3 (0.9) | 36 (0.6) |

| Missing | 5 (1.4) | 17 (0.3) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 202 (58.6) | 3822 (67.2) |

| Asian | 43 (12.5) | 443 (7.8) |

| Black | 34 (9.9) | 503 (8.9) |

| Mixed | 38 (11.0) | 799 (14.1) |

| Other | 6 (1.7) | 119 (2.1) |

| Missing | 22 (6.4) | 104 (1.8) |

| Breastfeeding at birth | 308 (89.3) | 2855 (49.3) |

| Breastfeeding at 2 weeks | 240 (69.6) | 1959 (33.8) |

| Breastfeeding at 6 weeks | 191 (55.4) | 1483 (25.6) |

| Number of face to face contacts per mother | 2 (1–4) | n/a |

| Number of telephone contacts per mother | 2 (1–4) | n/a |

| Number of text contacts per mother | 0 (0–2) | n/a |

| Total number of all contacts per mother | 6 (3–9) | n/a |

n/a, not applicable; BPSS, breastfeeding peer support service.

Table 2 shows the final, parsimonious, segmented regression models fitted to identify whether the introduction of the Nottingham BPSS had either an immediate or longer term impact on breastfeeding prevalence at birth, 2 and 6 weeks.

Table 2.

Changes in the prevalence of breastfeeding pre‐introduction and post‐introduction of the BPSS (parameters with 95% confidence intervals and p values)

| Outcome | Baseline trend (% change per month) | Immediate change in level of breastfeeding prevalence (%) | Change in trend in post‐intervention period compared with baseline (%) | Post‐intervention trend (% change per month)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding at birth | n/s | n/s | 0.55 (0.10–1.00) P = 0.018 | 0.55 (0.10–1.00) P = 0.018 |

| Breastfeeding at 2 weeks | n/s | n/s | 0.50 (0.15–0.86) P = 0.007 | 0.50 (0.15–0.86) P = 0.007 |

| Breastfeeding at 6 weeks | 0.09 (0.02–0.17) p = 0.013 | n/s | n/s | 0.09 (0.02–0.17) P = 0.013 |

Post‐intervention trend = baseline trend + change in trend

n/s, parameter not significant in parsimonious model

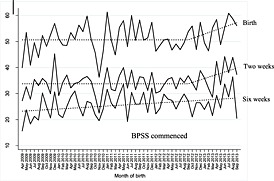

Prior to the introduction of the BPSS, the proportion of mothers giving birth each month who breastfed at birth and the proportion who were feeding at 2 weeks showed no month‐on‐month change; the baseline trend for breastfeeding at 6 weeks was increasing by 0.09% (95% CI 0.02–0.17) per month prior to the introduction of the BPSS. There was no immediate change in the proportion of women who breastfed at birth, 2 or 6 weeks following the introduction of the BPSS. However, the breastfeeding prevalence at birth and at 2 weeks begun to increase by 0.55% (95% CI 0.10–1.00) and 0.50% (95% CI 0.15–0.86) per month, respectively. By the end of the study period, this translated to an additional 6.6 women per 100 giving birth per month who initiated breastfeeding and an additional 6 per 100 who were breastfeeding at 2 weeks compared with the pre‐intervention period. There was no significant change in the pre‐intervention trend for breastfeeding at 6 weeks after the introduction of the BPSS. The original time series graphs, which include the fitted models for each outcome, are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Percentage of mothers aged <25 who breastfed at birth, 2 and 6 weeks post‐partum: original data (solid lines) and fitted model (dashed lines).

Discussion

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first quantitative evaluation using time series analysis of a BPSS targeted at younger women in the UK. Our results show that breastfeeding prevalence at birth and 2 weeks among mothers aged under 25 began to increase month‐on‐month after the introduction of the BPSS, where, previously, the prevalence had been static over time. However, there was no change from an underlying marginally increasing trend in breastfeeding prevalence at 6 weeks.

It is generally accepted that randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard of experimental designs. However, this study was a post‐hoc evaluation of the implementation of a new service where an RCT was not planned or conducted as part of the initial implementation. Segmented regression analyses of a time series is the strongest quasi‐experimental design for evaluating the impact of interventions and is ideal for evaluating non‐randomised community interventions (Wagner et al. 2002). The method is powerful as it accounts for the pre‐intervention magnitude and trend in the data (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group 2013). This study, therefore, provides stronger evidence on the effect of BPS on infant feeding outcomes than those previous studies that have compared breastfeeding prevalence before and after the intervention without considering secular trends. However, we acknowledge that there are some limitations with our data and analysis.

Feeding outcomes at birth were self‐reported, and thus, there was potential reporting bias in the data analysed; mothers who accessed the service may have been more likely to give socially‐desirable responses than women who had not accessed the service, resulting in an overestimation of the intervention effect at birth. However, as the BPSS only contacted mothers post‐natally who were reported by a midwife as having initiated breastfeeding, the risk of bias is considered to be minimal. The risk of bias in the recording of feeding outcomes at 2 and 6 weeks is lower as these are based on observation of feeding behaviour.

There is a risk of confounding in a time series analysis if other factors related to the outcome change at the time of the intervention. The United Nations Children's Fund Baby Friendly Initiative (UNICEF UK 2015) and Family Nurse Partnership (National Health Service 2015) commenced in the study area several years prior to the introduction of the BPSS and, therefore, the effects of these would likely have been accounted for in the baseline trend. The ‘Be A Star’ (Be A Star 2015) social marketing campaign, which aims to shift community norms around breastfeeding, was, however, launched in Nottingham in October 2012. It is possible that this intervention contributed to the effects found in this study. Unfortunately, we did not have the data to allow us to investigate further any effect of the ‘Be A Star’ campaign or other initiatives. Breastfeeding data were not available for other geographical locations where these initiatives were implemented but not the BPSS, and so there was no external control group for this analysis. Another approach might have been to conduct a time series analysis using data from women aged 25+ in the study area, effectively using these women as a control group – if changes in breastfeeding were evident in older as well as younger women, then this might suggest that external influences other than the BPSS intervention were responsible. However, group‐based peer‐support for women aged 25+ commenced at the same time (provided by unpaid volunteers) as the individual BPSS for younger women. It would thus not be possible to attribute any changes in breastfeeding at this time in the older age group to one or other of the social marketing campaign or the newly‐available group‐based peer support. However, we believe the contribution of the ‘Be A Star’ campaign is likely to be minimal as community cultural norms are unlikely to have changed quickly. Evidence suggests that there are complex, multifactorial influences on a mother's decision and ability to breastfeed (Dyson et al. 2005). The study design did not allow for the exploration of cultural influences and attitudes to breastfeeding and the impact these had on the outcomes of the intervention.

Intervention effects may have been underestimated as women who gave birth during the first 6 to 10 weeks of the study period would not have benefited from the full service offer as they would have already passed the gestation for an antenatal contact. Also, only 29% of the eligible population accessed the service during the study period, which may have limited the intervention effect. The gradual increase in reach over time was as expected as the service became embedded in the community, and newly recruited and trained peer supporters developed in skills and experience. Towards the end of the study period, reach became similar to that of the Bristol BPSS (47%), where peer supporters also directly contacted all pregnant women in the target group (Ingram 2013). Further analysis using time series analysis would be useful to identify the longer term impact once the service was fully embedded.

The statistically significant increase in breastfeeding prevalence at 2 weeks post‐partum demonstrates the success of the BPSS in supporting mothers during these most challenging 2 weeks. The UK Infant Feeding Survey found that when women experienced breastfeeding problems, those who did not receive help were more likely to have stopped breastfeeding within the first 2 weeks than those who received support (27% compared with 15%) (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2012a). This BPSS demonstrates this in practice, strengthening the evidence of effectiveness of BPS during the first 2 weeks post‐partum.

Given the month‐on‐month increase in breastfeeding prevalence at birth and 2 weeks following the introduction of the BPSS, one might expect there to also be some increase in the trend at 6 weeks, given that the greatest drop off occurs during the first 2 weeks post‐partum. One potential explanation for not finding this is that, as breastfeeding prevalence gradually reduces from the time of birth, any impact on breastfeeding at 6 weeks might be smaller than that at 2 weeks. It is, therefore, possible that the study was not sufficiently powered to detect changes at 6 weeks. Secondly, as the service aims to provide the most intense support during the 2 weeks after birth, it is plausible that the intervention was not of sufficient intensity to impact breastfeeding prevalence following this time point. This positive effect on breastfeeding outcomes at birth and 2 weeks, yet lack of effect at 6 weeks is similar to that found by other studies (McInnes et al. 2000; Agboado et al. 2010). The programmes in these studies also included antenatal and post‐natal support and were of higher intensity during the first 2 weeks post‐partum.

The findings from this study are interesting given the consistent negative findings of UK‐based RCTs of the effectiveness of BPS (Jolly et al. 2012). This may be because of the heterogeneous nature of BPS interventions. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the effect of setting (low‐income, middle‐income or high‐income country), intensity and timing of BPS found that low intensity BPS (defined as less than five contacts) was found to have little effect. Three of the four UK trials in this review were interventions of low intensity. However, the Nottingham BPSS was of higher intensity, which might explain the tentatively positive findings. The Nottingham BPSS is contracted to deliver a service based on best practice guidance and alignment with Baby Friendly Initiative standards (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2008). The proactive approach, the provision of a face to face contact within 48 h of the birth, ongoing needs‐led support and successful integrated working with midwifery and health visiting are all important best practice features of the intervention, which might help explain its apparent positive impact.

It is possible that the personal attributes of the peer supporters, including the fact that they were local women of similar socio‐economic backgrounds to those they were supporting, contributed to the impact of the intervention. It would be useful to explore this further through qualitative research to understand the specific elements of the intervention that contributed to its effectiveness.

Conclusion

This study makes an important contribution to the evidence base on the effectiveness of BPS, using a novel methodology. Findings have shown that an intensive one‐to‐one BPSS provided by paid peer supporters in both the antenatal and post‐natal periods may be beneficial in increasing breastfeeding initiation and duration until 2 weeks among younger mothers. The lack of impact on breastfeeding prevalence at 6 weeks suggests that intensive BPS may need to continue beyond 2 weeks in order to see longer‐term effects on breastfeeding prevalence, although this requires further exploration. Further analysis using time series methods would be useful to identify the longer‐term impact once the service is fully embedded, and a process evaluation would help to determine the mechanism of action of the intervention and to identify any implementation issues. An RCT might be considered in the longer term to formally evaluate the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of the BPSS.

Source of funding

This study was undertaken as part of a Master of Public Health dissertation. Nottingham City Public Health (Nottingham City Primary Care Trust and Nottingham City Council) funded the lead author to complete this MPH programme. No further funding was secured for this study.

Conflicts of interest

Sarah Scott, in her professional role with Nottingham City Council, is the commissioner of the BPSS evaluated in this study. Catherine Pritchard and Lisa Szatkowski have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributions

SS conceptualised and helped design the study, carried out the data analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, contributed to subsequent versions and approved the final manuscript as submitted. CP conceptualised and helped design the study, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. LS helped design the study, supported the data analysis, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed with the support of Nottingham City Council and Nottingham CityCare Partnership. We thank Nottingham CityCare Partnership for providing the infant feeding data required for this study.

Scott S., Pritchard C., and Szatkowski L. (2017) The impact of breastfeeding peer support for mothers aged under 25: a time series analysis, Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13, e12241. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12241.

References

- Agboado G., Michel E., Jackson E. & Verma A. (2010) Factors associated with breastfeeding cessation in nursing mothers in a peer support programme in Eastern Lancashire. BMC Pediatrics 10, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J., Anderson T., Grant M., Sanghera J., Jackson D. (2003) An evaluation of a support group for breast‐feeding women in Salisbury, UK. Midwifery 19, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlotti J.P., Cottrell B.H., Lee S.H. & Curtin J.J. (1998) Breastfeeding among low‐income women with and without peer support. Journal of Community Health Nursing 15, 163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (2001) Cultivate self‐efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness In: Handbook of Principles of Organization Behaviour (ed. Locke E.A.), pp 120–136. Blackwell: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Be A Star (2015) Breastfeed: be a star. Available at: http://www.beastar.org.uk/ (Accessed 19 March 2015).

- Britton C., McCormick F.M., Renfrew M.J., Wade A. & King S.E. (2007) Support for breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1), CD001141. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (2013) Interrupted time series (ITS) analyses, Available at: http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/21%20Interrupted%20time%20series%20analyses%202013%2008%2012.pdf (Accessed 19 March 2015).

- Department of Health (2013) Breastfeeding statistics: Q4, 2012–2013. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/breastfeeding-statistics-q4-2012-to-2013 (Accessed 19 March 2015).

- Department of Health (2012) Public Health Outcomes Framework 2013 to 2016, London: Department of Health; Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_132358 (Accessed 19 March 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Dyson L., Green J.M., Renfrew M.J., McMillan B. & Woolridge M. (2010) Factors influencing the infant feeding decision for socioeconomically deprived pregnant teenagers: the moral dimension. Birth 37, 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson L., Renfrew M.J., McFadden A., McCormick F., Herbert G., Thomas J. (2005) Promotion of Breastfeeding Initiation and Duration: Evidence into Practice Briefing. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: London: Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/proxy/?sourceUrl=http%3a%2f%2fwww.nice.org.uk%2fnicemedia%2fpdf%2fEAB_Breastfeeding_final_version.pdf (Accessed 19 March 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Health and Social Care Information Centre (2012a) Infant feeding survey 2010 Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB08694 (Accessed 15 March 2015).

- Health and Social Care Information Centre (2012b) Infant Feeding Survey, 2010. Appendix C: logistic regression nalysis. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB08694/ifs-uk-2010-apxc-log-reg-analy.pdf (Accessed 19 March 2015).

- Horta B.L., Bahl R., Martines J.C., Victora C.G. (2007) Evidence on the Long‐term Effects of Breastfeeding: Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses. World Health Organisation: Geneva: Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595230_eng.pdf (Accessed 19 March 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J. (2013) A mixed methods evaluation of peer support in Bristol, UK: mothers', midwives' and peer supporters' views and the effects on breastfeeding. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 13, 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J., Cann K., Peacock J., Potter B. (2008) Exploring the barriers to exclusive breastfeeding in black and minority ethnic groups and young mothers in the UK. Maternal & Child Nutrition 4, 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J., Rosser J. & Jackson D. (2005) Breastfeeding peer supporters and a community support group: evaluating their effectiveness. Maternal & Child Nutrition 1, 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip S., Chung M., Raman G., Chew P., Magula N., DeVine D. et al (2007) Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health outcomes in Developed Countries. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD: Available at: http://archive.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/brfout/brfout.pdf (Accessed 19 March 2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly K., Ingram L., Khan K., Deeks J., Freemantle N. & MacArthur C. (2012) Systematic review of peer support for breastfeeding continuation: metaregression analysis of the effect of setting, intensity, and timing. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 344, d8287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruske S., Schmied V. & Cook M. (2007) The “Earlybird” gets the breastmilk: findings from an evaluation of combined professional and peer support groups to improve breastfeeding duration in the first eight weeks after birth. Maternal & Child Nutrition 3, 108–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens P.J. (2002) Increasing breastfeeding initiation and duration at a community level: an evaluation of Sagkeeng First Nation's community health nurse and peer counselor programs. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association 18, 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes R.J., Love J.G. & Stone D.H. (2000) Evaluation of a community‐based intervention to increase breastfeeding prevalence. Journal of Public Health Medicine 22, 138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service (2015) Family nurse partnership. Available at: http://fnp.nhs.uk/ (Accessed 19 March 2015).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2008) NICE guidelines [PH11] maternal and child nutrition, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph11/chapter/key-priorities (Accessed 19 March 2015).

- Nottingham Insight (2012) Breastfeeding strategies for Nottingham city and Nottinghamshire county. Available at: http://www.nottinghaminsight.org.uk/d/74554 (Accessed 19 March 2015).

- Nottingham Insight (2014) Nottingham city joint strategic needs assessment February 2014: demographic context. Available at: http://www.nottinghaminsight.org.uk/insight/handler/downloadHandler.ashx?node=91518 (Accessed 19 March 2015).

- Organisation for Economic Co‐Operation and Development (2009) Breastfeeding rates, 2009. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/els/family/43136964.pdf (Accessed 19 March 2015).

- Renfrew M.J., Pokhrel S., Quigley M., McCormick F., Fox-Rushby J., Dodds R. et al. (2012a) Preventing Disease and Saving Resources: The Potential Contribution of Increasing Breastfeeding Rates in the UK. UNICEF: UK: Available at: http://www.unicef.org.uk/.../Baby.../Preventing_disease_saving_resources.pdf (Accessed 19 March 2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew M.J., McCormick F.M., Wade A., Quinn B. & Dowswell T. (2012b) Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5, CD001141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF UK (2015) Welcome to the Baby Friendly Initiative. Available at: http://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/ (Accessed 15 March 2015).

- Victora C.G., Horta B.L., Loret de Mola C., Quevedo L., Pinheiro R.T., Gigante D.P. et al. (2015) Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. The Lancet. Global Health 3, e199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A.K., Soumerai S.B., Zhang F. & Ross‐Degnan D. (2002) Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 27, 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (2003) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health Organisation: Geneva: Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42590/1/9241562218.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (Accessed 10 April 2015). [Google Scholar]