Abstract

Common mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety, affect approximately 16% of pregnant women in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Food insecurity (FI) has been shown to be associated with depressive symptoms. It has also been suggested that the association between FI and depressive symptoms is moderated by social support (SS); however, there is limited evidence of these associations among pregnant women living in low‐income and middle‐income countries. We studied the association between FI and depressive symptoms severity and assessed whether such an association varied among Ugandan pregnant women with low vs. high SS. Cross‐sectional data were collected among 403 pregnant women in northern Uganda. SS was assessed using an eight‐item version of the Duke‐UNC functional SS scale. FI and depressive symptoms were assessed by, respectively, the individually focused FI scale and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression scale. Women were categorized into two SS groups, based on scoring < or ≥ to the median SS value. Multivariate linear regression models indicated an independent association between FI and depressive symptoms severity. The association between FI and depressive symptoms severity was moderated by SS i.e. was stronger among women in the low SS category (adjusted beta (95%CI): 0.91 (0.55; 1.27)) than for women belonging to the high SS group (0.53 (0.28; 0.78)) (adjusted p value for interaction = 0.026). There is need for longitudinal or interventional studies among pregnant women living in northern Uganda or similar contexts to examine the temporal sequence of the associations among food insecurity, depressive symptoms severity and social support. © 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Keywords: food insecurity, depressive symptoms, social support, CES‐D, IFIAS, pregnant women, Uganda, Africa

Introduction

Common mental disorders, such as major depressive disorders and anxiety disorders, affect approximately 16% of pregnant women in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) (Fisher et al. 2012) and are associated with negative health consequences for the mother and her unborn child (Stewart 2007; Szegda et al. 2014). There is evidence, for example, that depression during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of preterm delivery (Rondó et al. 2003), low birth weight (Rondó et al. 2003; Rahman et al. 2004; Ferri et al. 2007; Nasreen et al. 2010), prolonged labour and delayed initiation of breastfeeding (Hanlon et al. 2009). Depression may also affect pregnant women's functionality, capacity to care for themselves or ability to utilize household‐level and community‐level resources. Indeed, depression during pregnancy is a well‐known risk factor for postnatal depression (Siu et al. 2012; Bolak Boratav et al. 2015; Yazici et al. 2015) and, thus, may have indirect impacts on mother–child interactions affecting infants' emotional and behavioural development during the postnatal period (Austin et al. 2005; DiPietro et al. 2006; Avan et al. 2010).

Food insecurity (FI) exists when people lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and for an active and healthy lifestyle (FAO 2012). FI is a modifiable risk factor for adverse health outcomes including poor mental health status in specific vulnerable populations including women (Olson 2005; Whitaker et al. 2006; Ivers & Cullen 2011), children (Cook et al. 2004; Whitaker et al. 2006) and/or persons infected with HIV (Ivers et al. 2009; Weiser et al. 2011; Tsai et al. 2012; Anema et al. 2014). In most societies, women are responsible for managing family feeding (Olson 2005) and other forms of caregiving, a situation that puts them at increased risk of FI or its consequences. The pregnancy period likely exacerbates the effects of FI on women's health given the expected increase in nutrient demands but also pregnant women's reduced capacity to procure and prepare food or engage in income‐generating activities. Studies conducted among US pregnant women show that, when faced with FI, pregnant women experience negative nutritional and psychosocial consequences including increased severity of depressive symptoms (Hromi‐Fiedler et al. 2010; Laraia et al. 2010). Limited data exist from LMIC contexts on the association between depression or depressive symptoms severity and FI during the pregnancy period.

Social support (SS) is the assistance and protection given to others (Langford et al. 1997) and takes three forms of informational (the provision of information to another during a time of stress), emotional (the provision of caring, empathy, love and trust) and tangible/instrumental (the provision of goods, services or financial support) SS (Langford et al. 1997). SS has been shown to mediate (Kapulsky et al. 2014) or moderate the association between FI and depressive symptoms severity (Tsai et al. 2010; Kollannoor‐Samuel et al. 2011). For example, data from Uganda (Tsai et al. 2012) indicate that SS, especially tangible SS (Langford et al. 1997), buffers the negative effects of household FI on depressive symptoms severity among HIV‐infected women. Similar findings on the associations among FI, SS and depressive symptoms severity have been reported in the US, for example, among Latinos with uncontrolled Type 2 diabetes (Kollannoor‐Samuel et al. 2011). There is limited evidence, however, of these associations among pregnant women, in high income countries or in LMICs. Understanding the association among FI, SS and depressive symptoms severity during pregnancy is of particular interest given the increased nutrient demands and changes in mood and anxiety surrounding this physiological period and, potentially, an even greater need for tangible and emotional support by the pregnant women, from the spouse, household or other community members.

Therefore, the primary goals of the current study were to determine if, among pregnant women in northern Uganda, FI and depressive symptoms severity were associated with each other and whether SS moderated such an association. We hypothesized that the association between depressive symptoms severity and FI would differ by pregnant women's SS status.

Key messages.

In these cross‐sectional data, food insecurity was independently associated with depressive symptoms severity among pregnant women in northern Uganda.

The association between food insecurity and severe depressive symptoms was stronger among women who reported lower levels of social support than for women in the high social support category.

Further research is needed to examine the temporal sequence and the mechanisms that underlay the associations among food insecurity, social support and severe depressive symptoms among pregnant women.

Methods

We studied pregnant women recruited from the antenatal clinic (ANC) of Gulu Regional Referral Hospital (also known as Gulu Hospital), a primary care clinic that registers more than 400 initial ANC visits per month. Gulu Hospital is located in Gulu, northern Uganda and serves as the main regional referral hospital for lower level hospitals and clinics in Gulu and nearby districts. It is the main teaching hospital for the Faculty of Medicine at Gulu University.

Northern Uganda experienced about 20 years of conflict pitting the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) against the national army of Uganda. During the peak of the conflict and follow‐up years, many people were forced into internally displaced persons (IDP) camps to protect them from sporadic LRA attacks and abductions. Since 2006, however, the region has enjoyed relative stability. Most IDPs have since returned to their previously abandoned homes and communities.

Data were collected as part of the (Prenatal Nutrition and Psychosocial Health Outcomes) study PreNAPs, a longitudinal observational study designed to document the interrelationships between FI, nutritional, and psychosocial exposures and outcomes among HIV‐infected and HIV‐uninfected pregnant women in post‐conflict northern Uganda. The recruitment process, inclusion and exclusion criteria, response rates, and reasons for refusal to participate have been reported elsewhere (Natamba, Achan, et al. 2014; Natamba, Kilama, et al. 2015). Briefly, between October 2012 and August 2013, we approached 415 pregnant women, and 405 of them accepted to participate. Ten of the participants approached at the antenatal clinic of Gulu Hospital cited lack of time as the reason for refusing to participate. There were insufficient survey data (incomplete items on the questionnaire) on two participants and these were excluded from further analyses. Complete data on all the variables of interest for this analysis were available on 403 pregnant women.

Measurements

Assessment of food insecurity and prenatal depressive symptoms

Methods for assessing FI (Natamba, Kilama, et al. 2015) and depressive symptoms (Natamba, Achan, et al. 2014) within this study have been published elsewhere. In short, we used the nine‐item individually focused FI access scale (IFIAS: (Natamba, Kilama, et al. 2015) to assess perceived FI in the past 4 weeks and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression (CES‐D: (Radloff 1977; Natamba, Achan, et al. 2014)) scale to document participants perceived depressive symptoms in the past week.

The IFIAS is a modified version of the household FI access scale developed by Coates and colleagues (Coates et al. 2007); but, unlike the household FI access scale, which measures FI at household level, the IFIAS assesses FI at the level of the individual. Each of the nine items on the IFIAS is a negatively expressed question aimed at assessing respondents perceived FI. For each item, respondents choose among five possible responses on a Likert scale: never (scored 0); rarely or 1–2 times in the last 4 weeks (scored 1); sometimes or 3–10 times in the last 4 weeks (scored 2); often or more than 10 times in the last 4 weeks (scored 3); and don't know (not scored). Thus, a total score can be obtained by summing scores on each item such that a respondents score across the nine items ranges between 0 and 27. Assessment of the psychometric properties of the IFIAS indicated that this FI metric possessed a two factor structure: the first factor was indicative of mild to moderate forms of FI and the other factor suggested severe forms of FI (Natamba, Kilama, et al. 2015). The overall IFIAS and the two subscales within it had very good measures of reliability with Cronbach's alpha values ranging from 0.75 to 0.87 (Natamba, Kilama, et al. 2015).

We used the CES‐D scale (Radloff 1977) to assess women's report of perceived depressive symptoms over a period of 1 week preceding the interview date. Unlike the original CES‐D, which is meant to be self‐administered (Radloff 1977), we used the CES‐D scale in an interviewer‐administered format (Natamba, Achan, et al. 2014). The CES‐D consists of 20 items covering all the common symptoms of major depression including depressive mood, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite and sleep disturbance. On the CES‐D, participants chose among four response options: rarely or none of the times (less than 1 day; scored 0); some or a little of the time (1–2 days; scored 1); occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3–4 days; scored 2); and most or all of the time (5–7 of the time; scored 3). Four items on the CES‐D are positively worded and need to be reverse scored. A total score is computed by summing the 20 items such that the overall scores ranges between 0 and 60. In this study, the entire CES‐D was strongly reliable with a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.92; and, the optimal CES‐D cutoff score of 17 or higher had a specificity of 78.5%, 72.7% sensitivity and 76.5% positive predictive value for detecting Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al. 1998)‐defined major depressive disorder (Natamba, Achan, et al. 2014).

Assessment of social support

We assessed women's perceived SS using an eight‐item Duke‐UNC functional SS instrument (Broadhead et al. 1988; Antelman et al. 2007; Tsai et al. 2012) (Supplementary file 1). On this SS scale, participants chose among three response options: much less than you would like or never (scored 1); less than they would like (scored 2); and as much as they would like (scored 3). A total score across all items was computed to derive the overall score per woman. In the original scale, higher scores reflect lower levels of SS, but for ease of interpretation, we inverted the individual items on the scale before administration such that high scores reflect higher levels of SS. Before calculating total scores on the SS scale, we conducted exploratory factor analyses of the SS items. Indeed, our analyses indicated that items on the SS scale appropriately represented the three SS subscales of informational, emotional and tangible SS (Langford et al. 1997).

Health information

At enrollment into this study, the gestational age of the women's index pregnancy was determined using women's recall of the first date of their last menstrual period. Prior to enrollment into this study, all women were tested for HIV at the ANC clinic of Gulu hospital per Government of Uganda (GoU) guidelines (MoH 2012). All HIV‐infected pregnant women in this study were participating in a GoU antiretroviral treatment programme to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV. Antiretroviral drugs were provided to all HIV‐infected pregnant women following the GoU (MoH 2012) and World Health Organisation guidelines (WHO 2012).

Other covariates

We documented participants' socio‐demographic and economic variables including women's age, parity (nulliparous vs. other), marital status (separated, divorced or widowed vs. other) and education level (primary level or lower vs. higher than primary level). Women were also asked about possession of 20 household assets contained in the socio‐economic module of the 2009–10 Uganda National Panel Survey Questionnaire (UBOS 2010). An asset index was generated using principal components analysis methodology (Filmer & Pritchett 2001). Accordingly, households with higher values on the asset index represent greater household wealth relative to other households in the sample. We assessed other contextual factors likely to be associated with women's experience of prenatal depressive symptoms and/or FI, including past history of domestic violence (“In the last year, has anyone in your household pinched, hit, slapped, kicked, shaken, punched or done anything else to hurt you physically or sexually?” yes vs. no), previous history of stay in an IDP camp (yes vs. no) or experience of any abduction related to the 1986–2006 LRA–Ugandan army war (yes vs. no).

Language adaptation of study instruments

Before administration, study questionnaires were translated into Acholi and/or Langi, the two similar Luo languages predominantly spoken in the study communities. Questionnaires were back translated into English by a team involving local research assistants (a nutritionist, midwife and a psychiatrist assistant) and a medical psychiatrist and approved for use by the Gulu University institutional review committee. All translators and research assistants involved in data collection were fluent in Acholi and/or Langi.

Statistical analysis

The main objective of this study was to determine whether the association between FI and depressive symptoms severity differred by pregnant women's SS status. Low SS status was defined as SS scores below the median score and high SS as SS scores at or above the median score.

We used conventional means, standard deviations and proportions to describe participant characteristics. Participants' differences in FI (IFIAS), depressive symptoms (CES‐D) severity and other characteristics by SS status were assessed using chi‐square tests for categorical variables and t‐tests for continuous variables.

Then, we examined the unadjusted and adjusted association between FI and depressive symptoms severity using multivariate linear regression models. Potential confounding variables (such as age, marital status, education level, parity, and previous history of internal displacement or abduction) were included in the adjusted models if they were associated with both FI (IFIAS) and depressive symptoms (CES‐D) scores at p < 0.05.

To test whether the adjusted association between FI and depressive symptoms severity was significantly moderated by SS, we took depressive symptoms (CES‐D) score as the outcome variable and tested the significance of the main effect of FI and SS and the interaction term between FI and SS. The model including interaction terms was adjusted for confounding variables established in the model without interaction terms. Upon finding that SS significantly moderated the association between depressive symptoms severity and FI, we re‐run all our analyses, separately, by women's SS status. Within each SS category, we assessed the unadjusted and adjusted association between depressive symptoms severity and FI. The stratified analyses were adjusted for confounding variables established in the pooled analysis.

Data were analyzed using stata statistical software program (version 14; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All statistical tests were two sided, and the level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics

Characteristics of participants recruited into this study, overall and by SS category, are summarized in Table 1. Of the 403 pregnant recruited into this study, 178 (44.2%) had SS scores that were below the median score, and the rest (n = 225) had SS scores that were equal to the median score or higher. There were significant differences between the two SS groups but also some similarities. For example, a higher proportion of pregnant women in the high SS group were HIV infected, widowed, separated or divorced, or had ever lived in an IDP camp. However, fewer women in the low SS group reported having ever experiencing abduction during the 1986–2006 civil war. Women in the low SS group reported higher CES‐D and IFIAS scores but lower measures of wealth than the higher SS group. We did not find significant differences in gestational age, attained age in years or parity between women in the two SS groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnant women enrolled in the PreNAPs study in northern Uganda overall and by social support category (n = 403)

| Variable | Overall (n = 403) | Low social support (A, n = 178) | High social support (B, n = 225) | A vs. B p‐valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestation age, weeks | 19.3 ± 3.8a | 19.1 ± 3.7 | 19.6 ± 3.8 | 0.195 |

| HIV infected | 133 (33%)a | 72 (40.5%) | 61 (27.1%) | 0.005 |

| Depressive Symptoms (CES‐D) score | 20.8 ± 13.2 | 28.1 ± 12.4 | 15.0 ± 10.6 | <0.0001 |

| Food insecurity (IFIAS) score | 9.6 ± 5.8 | 11.5 ± 5.3 | 8.1 ± 5.7 | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 24.7 ± 5.0 | 24.9 ± 5.2 | 24.4 ± 4.9 | 0.296 |

| Nulliparous | 108 (26.8%) | 65 (28.9%) | 43 (24.2%) | 0.287 |

| Widowed, separated or divorced | 31 (7.7%) | 23 (12.9%) | 8 (3.6%) | <0.001 |

| Only primary or less education | 221 (54.8%) | 112 (62.9%) | 109 (48.4%) | 0.004 |

| Asset Index | 0.0 ± 1.6 | −0.365 ± 1.3 | 0.288 ± 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Domestic violence in the past year | 109 (27.1%) | 64 (36%) | 45 (20%) | <0.001 |

| Ever lived in an IDP camp | 208 (51.6%) | 116 (65.2%) | 92 (40.9%) | <0.001 |

| Ever been abducted | 69 (17.1%) | 30 (13.3%) | 39 (21.9%) | 0.009 |

PreNAPs, Prenatal Nutrition and Psychosocial Health Outcomes study; CES‐D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression; IFIAS, individually focused food insecurity access scale; IDP, internally displaced persons.

Values are mean ± SD or n(%n).

p‐value derived from t‐tests (continuous) or chi‐squared tests (dichotomous) comparing the low vs. high social support groups.

Correlates of food insecurity (IFIAS) and depressive symptoms (CES‐D) scores

Table 2 summarizes variables associated with FI (IFIAS) and depressive symptoms (CES‐D) scores. Similar variables were positively and negatively associated with both IFIAS and CES‐D scores. Variables positively associated with both IFIAS and CES‐D scores were as follows: older age, lower asset index, being HIV infected, and being separated, divorced or widowed. Participants with lower education level, who reported domestic violence, previous history of stay in an IDP camp or past experience of abduction, were more likely to have higher IFIAS or CES‐D scores. Nulliparous women reported lower IFIAS as well as CES‐D scores. Participants' gestation age at recruitment was not associated with IFIAS or CES‐D scores.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlates of food insecurity (IFIAS) and depressive symptoms (CES‐D) scores by social support category (n = 403)

| Variable | Food insecurity (IFIAS) score | Depressive symptoms (CES‐D) score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables | r statistic | P value | r statistic | P value |

| Gestation age, weeks | −0.0038 | 0.9401 | −0.0016 | 0.9737 |

| Age, years | 0.1686 | 0.001 | 0.1750 | 0.000 |

| Asset Index | −0.3144 | <0.001 | −0.1650 | 0.001 |

| Categorical variables | MD ± SEd | P value | MD ± SE | P value |

| HIV infected | 2.66 ± 0.60 | <0.001 | 5.15 ± 1.37 | <0.001 |

| Nulliparous | −3.56 ± 0.62 | <0.001 | −4.56 ± 1.47 | 0.002 |

| Widowed, separated or divorced | 3.05 ± 1.07 | 0.005 | 6.71 ± 2.44 | 0.006 |

| Only primary or less education | 2.40 ± 0.56 | <0.001 | 3.06 ± 1.31 | 0.020 |

| Domestic violence in the past year | 1.27 ± 0.64 | 0.049 | 8.31 ± 1.42 | <0.001 |

| Ever lived in an IDP camp | 3.08 ± 0.55 | <0.001 | 5.72 ± 1.28 | <0.001 |

| Ever been abducted | 3.88 ± 0.74 | <0.001 | 4.59 ± 1.73 | 0.008 |

IFIAS, individually focused food insecurity scale; CES‐D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression; IDP, internally displaced person; MD ± SE: mean difference ± standard error.

Unadjusted and adjusted linear associations among food insecurity, depressive symptoms (CES‐D) scores and social support

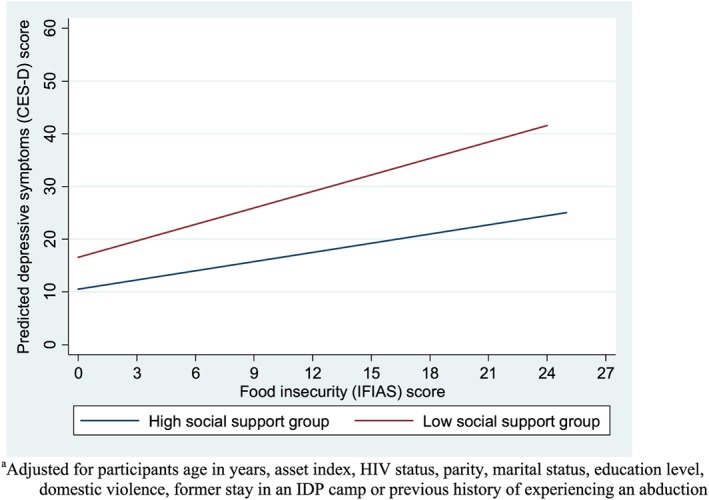

In Table 3, significant unadjusted and adjusted positive associations between depressive symptoms (CES‐D) and FI scores were observed. Further, a statistically significant interaction between FI and SS was observed in both the unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 3; p‐value for interaction = 0.026). The association between IFIAS scores and CES‐D score was stronger among women in the low SS group than in women belonging to the high SS category (Table 4 and Fig. 1). Further sensitivity analyses did not indicate that the moderating effect of SS on the association between FI and depressive symptoms severity differed depending on the type of SS (whether tangible, emotional or informational SS) being assessed (data not shown).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted linear regression coefficients (95%CIs) for the associations among depressive symptoms (CES‐Da) severity, food insecurity (IFIASb) score and social support category

| Variable | Unadjusted coefficient (95%CI): p‐value | Adjustedc coefficient (95%CI): p‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without interaction term | With interaction term | Without interaction term | With interaction term | |

| Food insecurity (FI) | 0.77 (0.58; 0.96): <0.001 | 0.58 (0.33; 0.83): <0.001 | 0.66 (0.45; 0.86): <0.001 | 0.49 (0.23; 0.74): <0.001 |

| Low social support (SS) | 10.53 (8.34; 12.72): <0.001 | 5.76 (1.32; 10.20): 0.011 | 9.17 (6.93; 11.40): <0.001 | 4.89 (0.51; 9.27): 0.029 |

| FI*SS | — | 0.47 (0.09; 0.86): 0.016 | — | 0.42 (0.05; 0.80): 0.026 |

CES‐D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression;

IFIAS, Individually‐focused Food Insecurity Access Scale;

Adjusted for participants age in years, asset index, HIV status, parity, marital status, education level, domestic violence, former stay in an IDP camp or previous history of experiencing an abduction.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted linear regression coefficients (95%CIs) between depressive symptoms (CES‐D) severity and food insecurity (IFIAS) score by social support category

| Low social support | High social support | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted coefficient (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted coefficienta (95%CI) | P value | Unadjusted coefficient (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted coefficienta (95%CI) | P value | |

| Food insecurity (FI) score | 1.05 (0.74; 1.36) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.55; 1.27) | <0.001 | 0.58 (0.34; 0.82) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.28; 0.78) | <0.001 |

CES‐D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression; IFIAS, individually focused food insecurity access scale.

Adjusted for participants age in years, asset index, HIV status, parity, marital status, education level, domestic violence, former stay in an IDP camp or previous history of experiencing an abduction

Figure 1.

The association between depressive symptoms severity and food insecurity by social support group.a

Discussion

Based on previous literature indicating that SS moderates the association between FI and depressive symptoms severity (Kollannoor‐Samuel et al. 2011; Tsai et al. 2012), we studied the associations among FI, depressive symptoms (CES‐D) severity and SS among pregnant women in northern Uganda. In summary, adjusted analyses indicated an independent positive association between FI and depressive symptoms severity. Further, our results show that the association between FI and depressive symptoms severity was moderated by SS, i.e. it was stronger among women with low SS than among women with greater SS (adjusted p‐value for interaction = 0.026).

Our results concur with findings from non‐pregnant HIV‐infected women in Uganda (Tsai et al. 2012) and with results from Latinos with type 2 diabetes in the USA (Kollannoor‐Samuel et al. 2011). Importantly, this is the first study to document the associations among FI, depressive symptoms severity and SS in pregnant women in Uganda, an LMIC environment. Furthermore, this study shows, for the first time that, among pregnant women in northern Uganda, the association between FI and depressive symptoms severity was moderated by SS. Findings from this study, whose temporal sequence needs to be confirmed in follow‐up longitudinal or interventional studies, may have major public health implications. These may include, for example, highlighting the beneficial role that SS plays in the development of FI‐induced antepartum depression. Also, our results suggest the need integrating mental health services that incorporate SS and food security components into antenatal care programmes in northern Uganda and other similar contexts.

This is a cross‐sectional study, and thus, it is not possible to infer causality or the directionality of the studied associations. That said, previous cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies have shown similar results among non‐pregnant women (Kollannoor‐Samuel et al. 2011; Tsai et al. 2012). Therefore, our results can be interpreted in the context of accumulating evidence indicating that SS moderates the association between FI and depressive symptoms severity. Indeed, it has been suggested that SS acts as a buffer (Cobb 1976; Cohen & Wills 1985), i.e. having access to SS buffers or protects against harmful effects of psychosocial stressors such as FI, economic deprivation and substance abuse. A combination of resources such as money, food or emotional support provided by family members and/or friends may protect against FI as well as its negative ramifications. Further qualitative and quantitative longitudinal and interventional studies to unpack these mechanisms among pregnant women in this study setting (northern Uganda) or other LMIC contexts are needed.

Our study has several strengths. In addition to being the first to examine the association among FI, SS and depressive symptoms among pregnant women in Uganda, this study used reliable and validated metrics for FI and depressive symptoms (Natamba, Achan, et al. 2014; Natamba, Kilama, et al. 2015). In terms of limitations, this is a cross‐sectional analysis and these findings do not demonstrate the causality or the temporal nature of the studied associations. It is also possible that there remains unmeasured confounding that might affect the significance and strength of the studied associations. These limitations need to be taken into account when generalizing findings from this study.

In conclusion, our results indicate that food insecurity and depressive symptoms severity are associated with each other; and the association is stronger among women belonging to the low social support group than among women in the high social support category. Longitudinal and/or interventional studies are needed to further elucidate the temporal nature of the studied associations. Also, to guide intervention development and evaluation, there is need for qualitative studies to unpack the mechanisms of how social support moderates the association between food insecurity and depressive symptoms severity. Lastly, there is need, also, to integrate mental health services that take into account food security and social support components into antenatal care services in northern Uganda or similar contexts.

Ethical considerations

Cornell University's Institutional Review Board and Gulu University Institutional Review Committee approved the study protocol. Permission to conduct the study in Uganda was obtained from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects before enrollment.

Source of funding

USAID Feed the Future Innovations Laboratory for Collaborative Research in Nutrition for Africa funded this study (Award Number AID‐OAA‐L‐10‐00006). SLY was supported by K01 MH098902 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The content in this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of USAID, or NIMH.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

BKN, SLY and JKG secured funding for the study. BKN, SM, JA, RJS, SLY and JKG conceived and designed the study. BKN supervised all the field activities, performed the data analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors, BKN, JA, SM, SLY, RJS and JKG, interpreted the findings, contributed to revising the manuscript critically and approved submission of this version.

Supporting information

Supplementary file 1

Supporting info item

Acknowledgment

This study was conceived, designed and data collected when the first author (BKN) was a graduate student at Cornell University; but, data analysis, results interpretation and manuscript drafting took place while he was a Yerby postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University. We gratefully acknowledge Patsy Brannon of Cornell University for her comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We acknowledge the support of Gulu Regional Referral Hospital administration for allowing us to access study participants and for providing space to the study within the hospital buildings. We thank the following research assistants who participated in this study: Sophie Becky Ajok, Hillary Kilama, Winifred Achoko, Daniel Acidri and Joe Cord Ojok. Last, but not least, we strongly appreciate the pregnant women that participated in this study.

Natamba, B. K. , Mehta, S. , Achan, J. , Stoltzfus, R. J. , Griffiths, J. K. , and Young, S. L. (2017) The association between food insecurity and depressive symptoms severity among pregnant women differs by social support category: a cross‐sectional study. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13: e12351. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12351.

References

- Anema A., Fielden S.J., Castleman T., Grede N., Heap A. & Bloem M. (2014) Food security in the context of HIV: towards harmonized definitions and indicators. AIDS and Behavior 18 (Suppl 5), S476–S489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antelman G., Kaaya S., Wei R., Mbwambo J., Msamanga G. I., Fawzi W. W. et al. (2007) Depressive symptoms increase risk of HIV disease progression and mortality among women in Tanzania. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 44 (4), 470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin M.P., Hadzi‐Pavlovic D., Leader L., Saint K. & Parker G. (2005) Maternal trait anxiety, depression and life event stress in pregnancy: relationships with infant temperament. Early Human Development 81 (2), 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avan B., Richter L.M., Ramchandani P.G., Norris S.A. & Stein A. (2010) Maternal postnatal depression and children's growth and behaviour during the early years of life: exploring the interaction between physical and mental health. Archives of Disease in Childhood 95 (9), 690–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolak Boratav H., Toker Ö. & Küey L. (2015) Postpartum depression and its psychosocial correlates: a longitudinal study among a group of women in Turkey. Women & Health, pp. 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead, W.E. , Gehlbach, S.H. , De Gruy, F.V. & Kaplan, B.H. (1988). The Duke‐UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire: Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Medical care, 709–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates J., Swindale A. & Bilinsky P. (2007) Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide (v.3) Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project. Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. (1976) Presidential Address‐1976. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine 38 (5), 300–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. & Wills T.A. (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin 98 (2), 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J.T.J., Frank D.A., Berkowitz C., Black M.M., Casey P.H., Cutts D.B. et al. (2004) Food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. The Journal of Nutrition 134 (6), 1432–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro J.A., Novak M.F., Costigan K.A., Atella L.D. & Reusing S.P. (2006) Maternal psychological distress during pregnancy in relation to child development at age two. Child Development 77 (3), 573–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri C.P., Mitsuhiro S.S., Barros M.C., Chalem E., Guinsburg R., Patel V. et al. (2007) The impact of maternal experience of violence and common mental disorders on neonatal outcomes: a survey of adolescent mothers in Sao Paulo, Brazil. BMC Public Health 7 (1), 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmer D.D. & Pritchett L.H.L. (2001) Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data‐‐or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography 38 (1), 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J., Mello M.C.D., Patel V., Rahman A., Tran T., Holton S. et al. (2012) Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low‐ and lower‐middle‐income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90 (2), 139G–149G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2012) World Food Program International Fund for Agricultural Development In: The State of Food Insecurity in the World: Economic Growth is Necessary but not Sufficient to Accelerare Reduction of Hunger and Malnutrition. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon C., Medhin G., Alem A., Tesfaye F., Lakew Z., Worku B. et al. (2009) Impact of antenatal common mental disorders upon perinatal outcomes in Ethiopia: the P‐MaMiE population‐based cohort study. Tropical Medicine & International Health 14 (2), 156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hromi‐Fiedler A., Bermúdez‐Millán A., Segura‐Pérez S. & Pérez‐Escamilla R. (2010) Household food insecurity is associated with depressive symptoms among low‐income pregnant Latinas. Maternal & Child Nutrition 7 (4), 421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivers L.C. & Cullen K.A. (2011) Food insecurity: special considerations for women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 94 (6), 1740S–1744S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivers L.C., Cullen K.A., Freedberg K.A., Block S., Coates J., Webb P. et al. (2009) HIV/AIDS, undernutrition, and food insecurity. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 49 (7), 1096–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapulsky L., Tang A. & Forrester J. (2014) Food insecurity, depression, and social support in HIV‐infected Hispanic individuals. Journal of immigrant and minority health 17 (2), 408–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollannoor‐Samuel G., Wagner J., Damio G., Segura‐Pérez S., Chhabra J., Vega‐López S. et al. (2011) Social support modifies the association between household food insecurity and depression among Latinos with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 13 (6), 982–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford, C.P. , Bowsher J., Maloney J.P. & Lillis P.P. (1997). Social support: a conceptual analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 25(1), 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraia, B.A. , Siega‐Riz, A.M. & Gundersen, C. (2010). Household food insecurity is associated with self‐reported pregravid weight status, gestational weight gain, and pregnancy complications. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 110(5), 692–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MoH (2012) The Integrated National Guidelines on Antiretroviral Therapy, Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV, and Infant and Young Child Feeding. Uganda Ministry of Health: Kampala. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreen H.E., Kabir Z.N., Forsell Y. & Edhborg M. (2010) Low birth weight in offspring of women with depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy: results from a population based study in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 10, 515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natamba B.K., Achan J., Arbach A., Oyok T.O., Ghosh S., Mehta S. et al. (2014) Reliability and validity of the center for epidemiologic studies‐depression scale in screening for depression among HIV‐infected and ‐uninfected pregnant women attending antenatal services in northern Uganda: a cross‐sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 14, 303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natamba B.K., Kilama H., Arbach A., Achan J., Griffiths J.K., Young S.L. et al. (2015) Reliability and validity of an individually focused food insecurity access scale for assessing inadequate access to food among pregnant Ugandan women of mixed HIV status. Public health nutrition 18 (16), 2895–2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson C.M. (2005) Food insecurity in women: a recipe for unhealthy trade‐offs. Topics in Clinical Nutrition 20 (4), 321. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L.S. (1977) The CES‐D scale: a self‐report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1 (3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A., Iqbal Z., Bunn J., Lovel H. & Harrington R. (2004) Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness: a cohort study. Archives of General Psychiatry 61 (9), 946–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondó P.H.C., Ferreira R.F., Nogueira F., Ribeiro M.C.N., Lobert H. & Artes R. (2003) Maternal psychological stress and distress as predictors of low birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57 (2), 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y. & Sheehan K.H. (1998) The Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM‐IV and ICD‐10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 5 (20), 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu B.W., Leung S.S., Ip P., Hung S.F. & O'Hara M.W. (2012) Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a prospective study of Chinese women at maternal and child health centres. BMC Psychiatry 12 (1), 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R.C. (2007) Maternal depression and infant growth: a review of recent evidence. Maternal & Child Nutrition 3 (2), 94–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szegda K., Markenson G., Bertone‐Johnson E.R. & Chasan‐Taber L. (2014) Depression during pregnancy: a risk factor for adverse neonatal outcomes? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 27 (9), 960–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai A.C., Weiser S.D., Petersen M.L., Ragland K., Kushel M.B., Bangsberg D. R. (2010) A marginal structural model to estimate the causal effect of antidepressant medication treatment on viral suppression among homeless and marginally housed persons with HIV. Archives of General Psychiatry 67 (12), 1282–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, A.C. , Bangsberg D.R., Frongillo E.A., Hunt P.W., Muzoora C., Martin J.N. et al. (2012). Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine 74(12), pp.2012–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UBOS (2010) The Uganda National Panel Survey 2009/10: Household Questionnaire. Uganda Bureau of Statistics: Kampala. [Google Scholar]

- Weiser S.D., Young S.L., Cohen C.R., Kushel M.B., Tsai A.C., Tien P.C. et al. (2011) Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 94 (6), 1729–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker R.C., Phillips S.M. & Orzol S.M. (2006) Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool‐aged children. Pediatrics 118 (3), e859–e868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO , (2012). Programmatic update: use of antiretroviras drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants. World Health Organization: Geneva. [PubMed]

- Yazici E., Kirkan T.S., Aslan P.A., Aydin N. & Yazici A.B. (2015) Untreated depression in the first trimester of pregnancy leads to postpartum depression: high rates from a natural follow‐up study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 11, 405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file 1

Supporting info item