Abstract

This paper applies an implementation framework, based on a behavior change model, to compare four case studies of complementary feeding programs. It aims to expand our understanding of how to design and implement behavior change interventions aimed at improving complementary feeding practices. Four programs met the selection criteria of scale and documented improvements: Bangladesh, Malawi, Peru, and Zambia. We examined commonalities and differences in the design and implementation of social and behavior change approaches, use of program delivery platforms, challenges encountered, and lessons learned. We conclude that complementary feeding practices, in particular dietary diversity, can be improved rapidly in a variety of settings using available program platforms if interventions focus on specific constraints to food access and use effective strategies to encourage caregivers to prepare and feed appropriate foods. A five‐step process is presented that can be applied across a range of complementary feeding programs to strengthen their impacts.

Keywords: behavior change, child nutrition, Complementary feeding, framework for scaling up, IYCF, program review

1. INTRODUCTION

Preventive nutrition approaches such as improving infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices, specifically complementary feeding have received attention (Caulfield, Huffman, & Piwoz, 1999, Victora, de Onis, Hallal, Blossner, & Shrimpton, 2010) and have been well defined and implemented since at least 2003 (PAHO, 2003). The use of behavior change strategies with or without the provision of food supplements to improve IYCF has been estimated to reduce child mortality and improve nutrition. Investments in scaling up these approaches have high payoffs according to the Lancet series of supplements (Lancet Child Survival supplement 2003, Lancet Nutrition supplement 2008, & Lancet Nutrition supplement 2013, Lancet 2016). Reviews of the efficacy and effectiveness of programs and evaluation studies have identified the need to address the determinant of IYCF practices (Dewey & Adu‐Afarwuah, 2008, Imdad, Yakoob, & Bhutta, 2011). However, there remains a dearth of lessons from field programs that were implemented in diverse settings and succeeded in improving complementary feeding using available program platforms. This paper aims to draw on actual field experiences to identify program elements that can be applied broadly.

Improving complementary feeding requires an understanding of what drives feeding behaviors and how to facilitate adoption of improved practices in a variety of cultural and economic settings (PAHO, 2003, WHO, 2008). To accelerate progress, we need to understand not only the design principles but also how to implement, monitor, scale up, and sustain delivery of interventions to address the determinants of complementary feeding. Specifically, we need to:

systematically review emerging experience and lessons learned in varied settings on how to address operational issues related to behavior change interventions for complementary feeding

identify useful tools to facilitate different steps in program implementation including capacity building, communication, advocacy, strategic use of data, use of media, and measurement and learning

document and disseminate lessons learned so they can provide a continuing stream of ideas and experiences for upcoming programs

Fabrizio, van Liere, and Pelto (2014) concluded that more detail was needed on how successful programs were designed and implemented, and identified as particularly important: (a) the use of formative research to focus program interventions on locally relevant barriers and motivations for improving specific complementary feeding practices, and (b) reliance on an explicit logic model or program impact pathway explaining how interventions would lead to results. This paper attempts to further extend this analysis based on programs intended for large‐scale implementation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We explored the unpublished grey literature to find examples of successful nutrition programs focusing specifically on complementary feeding. The approach for this study was to compare and contrast diverse programs having the common objective of improving complementary feeding practices. In this paper, we present four programs in detail that addressed the determinants of complementary feeding. We selected programs for which detailed documentation was available on processes, on the drivers of behaviors and steps taken to improve outcomes.

A search was conducted for published and unpublished reports that described interventions, operational steps, and results of programs. Implementing stakeholders were also contacted through the CORE Group agriculture and nutrition working groups, Helen Keller International (HKI), Save the Children, and the SPRING Project (U.S. Agency for International Development). In all, 16 programs were examined as potential candidates. Selection criteria included: documented evidence of improvements in complementary feeding practices using rigorous evaluation methods; detailed descriptions of intervention design and implementation processes; the use of varied program platforms such as agriculture and health, governmental and non‐governmental organization (NGO) programs; and representation from different regions of the world. Four programs located in Bangladesh, Malawi, Peru, and Zambia were selected. Exclusion criteria included lack of evidence of improved complementary feeding practices and lack of rigorous evaluation

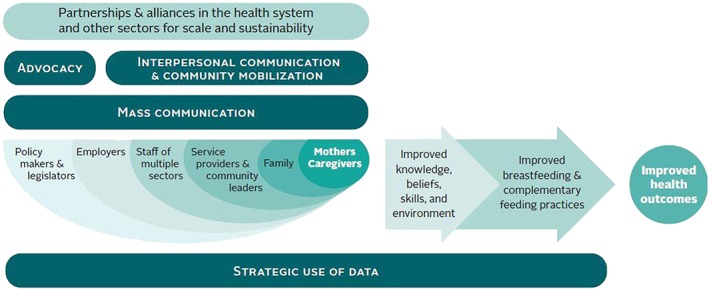

The primary sources of information included reports provided by NGOs, conference presentations, the published literature, and in‐depth interviews. We identified common elements and major variations across programs. Applying a widely recognized behavior change framework (Figure 1) that is based on the socio‐ecological model of behavior change (Stokols, 1996), we examined commonalities and differences in the design and implementation of behavior change strategies. Program delivery platforms, challenges and lessons learned were extracted. Qualitative and quantitative process assessments, and evaluations conducted by the four programs provided valuable insights regarding elements of program design and implementation.

Figure 1.

Implementation framework for large scale behavior change programs

Interventions in the four case studies addressed the following determinants of complementary feeding practices:

At the mothers' level: knowledge, beliefs, skills and self‐efficacy or confidence, workload

‐At the household level: food/water/soap availability, family roles

At the community level: social norms, connectivity to media/markets/services/resources

At program delivery level: coverage/scale/quality of support and information

At the policy level: guidelines and incentives available in food and agriculture, cash transfer, health services programs.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Program characteristics

The programs selected were two to 5 years in duration, and program scale ranged from one district (Zambia) to the whole country (Bangladesh). Some were implemented through NGOs and others through government. See Table 1. All programs were evaluated through randomized controlled trials; one used a cohort design and three used pre‐ and post‐ cross‐sectional surveys. None of the evaluations has a pure control (or non intervention areas). The evaluations compare exposures to less intensive and more intensive interventions. Among the four programs, three used WHO‐recommended IYCF indicators as their behavioral objectives. The fourth (in Peru) was launched in 1999 and preceded the development of global IYCF indicators; it used similar indicators

Table 1.

Program context

| Contextual factors | Bangladesh | Malawi | Peru | Zambia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline | 2009–2014 | 2011–2016 | 1999–2001 | 2010–2015 |

| Sector and program platforms | NGO for service delivery Policy, strategy, planning & mass communication under Ministry of Health | Ministry of Health workers, Ministry of Agriculture extension workers and district coordinating bodies | Ministry of Health Facility‐based health managers and providers | Ministry of Health community workers,

Ministry of Agriculture extension workers and district coordinating bodies |

| Implementing partners for services delivery | BRAC Essential Health Care and MNCH programs, National IYCF Alliance under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (IPHN), advertising agencies | Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development (MoAIWD), and the Ministry of Health (MoH) | Ministry of Health, Trujillo Region: child health services; Instituto de Investigación Nutricional, Lima Peru, | Ministry of Agriculture & Livestock (MAL), Ministry of Health (MoH), Ministry of Community Development Mother & Child Health (MCDMCH) |

| Scale and location | National with intensified interventions in 60% of national rural areas | Two rural districts: Kasungu and Mzimba | Department of Trujillo, 6 of 12 health centers (6 controls) | Rural areas of Mumbwa District, Central Province |

| Funding and resources | Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, BRAC, IYCF alliance including UNICEF, USAID, and DFID | Government of Malawi, FAO, German Ministry of Food & Agriculture (BMEL) | Government of Peru (Trujillo), USAID | Government of Zambia, Irish Aid, Kerry Foundation |

3.2. Design processes

Among the selected programs, the design process included several rounds of quantitative and qualitative studies (PAHO, 2004). These involved identifying and prioritizing a few key behaviors and their determinants. They also identified constraints and opportunities at various levels, exposure to service delivery and information sources, and priority audiences. All the design work engaged mothers and family members directly on a one‐to‐one basis to understand their perceptions, motivations, barriers, and preferred channels of communication. Methods included individual in‐depth and semi‐structured interviews with mothers, observations, and dietary assessments. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were used less frequently (Table 2). For examples of formative research in Bangladesh see Rasheed et al. (2011) and Nizame et al. (2013). Formative research findings were used to select key audiences—including influentials in the family and community—and the phrasing of messages, channels of communication, and contact points where key audiences could be reached with the desired frequency. All programs utilized some form of materials testing, piloting, or trials before finalizing the interventions for full scale implementation. These ranged from 3 to 6 month long operational pilots of a comprehensive multi‐component program, to testing of specific intervention components such as recipes, messages, tools, and materials. Assessments were also conducted during implementation to test solutions to problems, enhance the scope of the interventions in response to new opportunities or issues, and monitor processes for rapid diagnosis and resolution of bottlenecks.

Table 2.

Assessments and formative research

| Design process | Bangladesh | Malawi | Peru | Zambia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topics | Urban/rural differences in IYCF; child illness; barriers and motivations for IYCF and handwashing; influencers; food/soap access; mother's employment; health care seeking; media habits; frontline worker knowledge and perceptions | Current practices, gaps, foods available, seasonality; feasibility and acceptability of enriched porridge recipes; functioning of health and agricultural extension workers; coordination mechanisms; coverage of food security and IYCF interventions | Mothers' perceptions/aspirations, feeding practices, difficulties, barriers, and motivations for IYCF, care seeking; food attributes, best buys, coverage & quality of IYCF service and counseling in health services, health provider knowledge, motivations for work; job aids/educational materials | Small farmer production practices; food costs; household food security; household dietary diversity; child illness; mother's IYCF knowledge; community health volunteer activities; coordination of community/government workers |

| Methods used | ||||

| 24‐h dietary recall | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Market survey/seasonality | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Mothers KAP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| In‐depth interviews | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Farm production | ✓ | |||

| Key informant interviews | ✓ | |||

| Health worker KAP | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Media habits, recall | ✓ | |||

| Rapid trials/pilots | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Empowerment index | ✓ | |||

| Observations | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Exit interviews | ✓ | |||

| Baseline/endline household surveys | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Longitudinal cohort | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Midline | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Monitoring | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Main findings at baseline | ||||

| All CF indicators were low at baseline; poor appetite a problem; similarities in urban/rural IYCF; food resources available in ¾ families; soap available; large gaps in maternal knowledge in complementary feeding, low self‐efficacy; local terms for unhealthy/healthy child, frontline worker knowledge gaps, high reach of mass media for all groups; high coverage of volunteers | Low diversity and meal frequency; too early introduction of food; watery porridge; low consumption of vegetables, fruit, fats, and animal source foods; feeding from family plate and not a separate child's plate; poor hygiene practices; women's workload high; seasonal food deficits; gaps in sector coordination | Poor appetite; thin consistency of foods; low intakes of critical micronutrients/feeding difficulties; low coverage and quality of counseling in 3 health services contacts (well child care, pediatrics, nutrition); inconsistency of messages by health facility/personnel, lack of teamwork in health services; opportunities for improvement in IYCF feeding practices and in delivery of IYCF in health services | Low household and child diet diversity; few families produced micronutrient rich foods; household production linked to child diet diversity; gender empowerment linked to child nutrition; most families had access to and utilized health and agricultural services; barriers identified for multi‐sectoral coordination | |

All programs utilized secondary data in addition to new studies—most often demographic and health surveys (DHS) or other national surveys as a basis for designing interventions. Baseline surveys carried out for evaluation purposes often provided quantitative data for intervention design as well. The surveys and studies measured complementary feeding indicators, household resources, maternal and child attributes, and other factors that could influence how children in the 6–24 month age group were fed.

3.3. Interventions

The interventions focused on a limited number of complementary feeding practices. Dietary diversity of complementary foods was common across all four programs. All four identified animal source foods (egg, fish, chicken liver, and meat) as having potential for improvement. Among barriers to improving complementary feeding, mothers in Bangladesh and Peru reported their children had poor appetites. In Peru, the program identified watery soups and thin porridges as a problem and also emphasized responsive feeding. The use of sugary drinks, starchy products, and unhealthy snack foods were considered deterrents as mothers and caregivers struggled to feed the recommended nutrient dense family foods. Family members often brought home unhealthy foods, either mistakenly believing them to be growth promoting or “to please the child.”

Research in the countries showed that poor access to recommended foods and lack of convenience or time related to food preparation and feeding were barriers. Access to diverse foods was a limiting factor that required linking agriculture with health/nutrition in Malawi and Zambia. These two programs supported household food production strategies and provided associated inputs to families as a way to promote improved complementary feeding practices. In Bangladesh and Peru, food availability was not found to be a limitation for improving practices of the majority of households. In Bangladesh, lack of convenience in the location of a hand‐washing station close to where the child's food was prepared and fed was a barrier to hand‐washing. A common limitation among mothers and frontline workers was workload and it took considerable follow up to ensure adequate focus on feeding. Fathers and grandmothers were important influencers of mothers' work and infant feeding practices and the uptake of interventions in Bangladesh, Malawi, and Zambia.

3.4. Program delivery platforms

The choice of the main program delivery platforms was based in part on potential for providing multiple age‐specific contacts with mothers below 2 years. Each country aimed to combine program platforms for high coverage, greater frequency of contacts during defined periods of time (6 to 24 months of age), and for ensuring better quality of counseling (e.g., adherence to program content ensured through training, supervision, and monitoring feedback). This was a challenge in some programs and coverage data from Malawi and Zambia show that modest only levels of the planned contacts were actually completed. For details and background on Zambia's program see Stallkamp (2015) and Toure, Rawat, Harvey, Mwanamwenge, and Pelletier (2015). Peru achieved intermediate coverage and Bangladesh relatively high levels of coverage. Each program achieved some geographic expansion or scale in their complementary feeding interventions beyond the initial plans.

3.5. Channels of communication and program approaches

Approaches developed for reaching key audience segments in one or more of the programs included: interpersonal counseling, community mobilization, women's empowerment, mass communication, provision of handwashing stations, food production inputs, national and sub‐national advocacy, coalition/alliance building to harmonize messages, and cross‐sectoral coordination.

The use of different channels of communication to reach different categories of audiences was determined by media habits studies in Bangladesh, where mass media emerged as a major program component for achieving national scale rapidly, changing the household perceptions of social norms, reaching multiple key audiences, and as a way of reminding and lending credibility to frontline workers. Other programs did not utilize media habits data for designing their programs.

Interpersonal communication with mothers was the most common approach used by the four programs (see Tables 3 and 4). This included counseling/coaching/demonstrations by community volunteers, health workers, and agricultural extension workers. Feeding bowls with specific markings on quantity and diversity were given to families in Bangladesh.

Table 3.

Behavior change components

| Component | Bangladesh | Malawi | Peru | Zambia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Messages | Timely introduction of CF; use of animal food diversity; responsive feeding; age‐specific meals and amounts; no sugary drinks/snacks | Enriched porridge recipes; use six food groups; diversified food production (6 food groups) | Three key messages for mothers: feed thick puree first in the meal; add special ingredient(egg, chicken's liver or fish) to plate; Teach child to eat with love, patience, good humor | Increase household and child dietary diversity; meal frequency; more diversified food production; women's empowerment |

| Intervention approaches | BRAC community health workers and volunteers carry out home visits; mass media (TV); community mobilization; doctors trained/orientations | Agricultural extension workers through farm schools 1 and model farms; MOH nutrition workers (CNPs); printed materials (recipe books) | Health workers in 3 child health services (well child, sick child, nutrition) delivered intervention primarily at health facilities; emphasis on well child visits as aligned with prevention. Intervention included messages, job aids, printed recipe flyers, food preparation demonstrations, group well child checks/sessions | Health volunteers visits to community groups and at health facilities; agricultural extension at model farm schools 1 and groups |

| Strategies to improve convenience and physical access for changing behaviors | Handwashing stations relocated in the home for convenience of washing hands with soap; bowls given to specify amount of CF; home visits used for counseling for convenience of mothers and family members | Families/farmers given dairy cows, goats, sheep, pigs, chickens, fish; agricultural extension inputs and IYCF lessons from CNPs held in communities | IYCF counseling, Message delivery at all IYC health services contact at government health facilities where families bring their children for health care; improved coordination among IYC health services; food preparation demonstrations. No food supplements were given. | Food production inputs such as agricultural extension, seeds, and small livestock given to small farmers |

| Strengthening mothers' and families' beliefs | Emotionally appealing TV spots featuring doctors; doctors mobilized to promote IYCF benefits | Messages shared with fathers and grandmothers; key messages presented in the local languages with culturally appropriate illustrations of good childcare and feeding practices | Endorsement by all health workers (doctors, nurses, nutritionists, assistants) at the health facilities, improved mothers awareness of, and self‐efficacy for, improved child feeding behaviors. Everyone from doorman to medical director expected to know key messages and be supportive | Group counseling to share positive experiences among mothers; visible increases in food produced |

| Creating a perception of new IYCF social norms | Showing mothers practicing recommended practices on TV; family support, multiple community mobilization forums and events showing visuals and videos on mothers practicing IYCF | CNPs worked with peer groups; fathers, local leaders, and grandparents encouraged; government certificate during a graduation ceremony by district staff, sensitized the community on nutrition issues | Teach child to eat with ‘love, patience, and good humor’ aligned with cultural norms/mothers' concerns; built rapport with health providers; demonstrate and repeat same key messages at all contact points by all levels of workers | Group work with peers, cooking sessions and postcards helped in repeating the information about recommended practices; use of theater; workers from 2 sectors repeating same messages |

| Building mothers' confidence | Hands on practice in feeding young children by mothers guided by frontline workers in home visits, simple solutions to common problems shown in TVCs, mothers given 250 ml bowls for CF | Joint training of mothers engaged in agriculture and nutrition communication activities, practical sessions on food selection and preparation, support for food production of diverse foods timed to coincide with IYCF messages; recipe booklets as reminders | Improved motivational counseling technique and content to engage mothers, address mothers' concerns;

Hands‐on practice with food and feeding demonstrations, group well baby sessions in health facilities; use of well tested methods and materials ensured that mothers could practice the behaviors |

Women's empowerment—engaging women in food production to build confidence and ability to take decisions; use wife‐husband teams during training and field practice in farming |

| Strengthening frontline worker performance | Training videos, hands‐on practice in training, twice monthly supportive supervision, monthly group meetings of frontline workers; incentives for mothers' behavior change; use of bowls given to families | IEC materials contained teaching tools and instructions; frontline workers to backstop CNP and support from district staff; performance monitoring | Simplification of messages, job aids; team training (all personnel in contact with IYC trained together); hands‐on practice; regular feedback by research team with committee of health workers formed in each center, accreditation process including supportive supervision; positive feedback from families and health workers especially when Teach child to eat with “love, patience and good humor” was promoted | Trainers are small holder model farmers themselves, they have experience and respect from the community; incentives (bicycle, seeds, T‐shirt); monthly refresher trainings for volunteers; selected follow up to low performing CHVs |

| Using data to address coverage and quality gaps | Triple layer of monitoring and monthly/quarterly feedback to and from BRAC; media studies on exposure and recall of messages | Supervision, follow up, and monitoring integrated in the services delivery systems of agriculture and health | High levels of quality standards set for health facilities by MOH authorities; accreditation by external evaluators using record reviews, observation of IYC consultations, exit interviews, and home visits | Tracked the number of nutrition trainings; number of community health volunteers attending refresher trainings plus follow up |

1 Farm schools are an alternative to didactic, top‐down training and supervision visits for agricultural extension. They usually involve groups of farmers demonstrating and trying out improved farming methods for the purpose of participatory and collective learning what works in their local settings.

Table 4.

Activities and channels used for services and information by level

| Activities & channels | Bangladesh | Malawi | Peru | Zambia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers/caregivers level | Home visits to coach mothers; mothers health education groups; 6 TV spots placed to reach mothers, 5 TV spots developed to appeal to mothers; registers maintained for each mother/child by village and worker | Ten nutrition education sessions with groups of 15 caregivers with children aged 6–18 months; a weekly or bi‐weekly meeting for approximately 2 h. With the completion of each IYCF group, caregivers received a government certificate during a graduation ceremony | Improved IYCF message delivery/counseling, demonstrations, improved anthropometry and group well child sessions added to existing visits to health facilities; age‐specific IYCF guidelines provided in printed materials and job aids, all health center staff involved | A set number of visits or group meetings were held (e.g., women's groups met biweekly) |

| Household level | 2 TV spots for fathers, village forums targeted to fathers; family featured in TV spots; water and soap located for handwashing before feeding | Fathers, local leaders, and grandparents encouraged to attend education sessions; farmers and families trained, inputs to diversity production (e.g., giving dairy cows, goats, sheep, pigs, chickens, fish) | All caregivers accompanying the child to health centers included in counseling/demonstrations; fliers with recipes were taken home from health centers | Families trained and supported by model farmers to produce diverse foods and feed young children |

| Community level | Community mobilization forums; crowd events with videos & quiz; local doctors and opinion leader meetings and materials; children's animated film on CF | FFS and JFFLS curricula covered nutrition topics including the 6 food groups; seasonal food availability calendar; dietary diversification, community action planning for food security; and food processing and preparation | Health centers are located close to or in communities; intervention concentrated in health center but work extends into some community activities | Agricultural training (around production diversity) with small model farmers; drama groups emphasized certain behaviors in the broader community audiences |

| Food/health systems level | Health volunteers through workload allocation, training, supervision, refresher training, monthly meetings, monitoring, incentives; trained monitors and ‘organizers’ allocated to support/manage frontline workers; WHO/UNICEF training manual adapted | Joint coordination meetings at district level; IEC materials jointly developed; joint agricultural and health extension trainings; Africa regional UNICEF counseling package used | Team training; nutrition counseling integrated within child health services; key messages mandatory for all points of contact; doctors, nurses, and health assistants trained jointly as a team; accreditation certificates for meeting standards | Coordination across the government ministries to improve diversity in food availability and consumption; training frontline workers through cascade training; incentives (e.g., bicycle, seeds, T‐shirts); monthly refresher trainings; monitoring; National GOZ materials used, adapted from UNICEF |

| Program/policy level | Harmonizing messages and tools among implementing stakeholders in the country through an alliance; preparing a GOB national framework and plan for IYCF communication | Project data shared to advocate for multi‐sectoral approaches, IYCF counselling booklet integrated into the national standardized counselling card collection | Advocacy and engagement of Trujillo Health Department for uptake of key activities; sharing evidence and tools for national uptake; incorporation of complementary feeding demonstrations in well child sessions into national policy; messages and educational materials disseminated by central MOH | Example of Mumbwa district given to national authorities; site visits and sharing tools with SUN Initiative for scaling up |

In three of the programs, interactions with mothers and family members took place during home visits or places close to the homes of families with young children. In Peru, interactions took place at primary health care centers. Substantial efforts in all programs went into building the capacity and motivation of frontline workers to engage mothers directly. Malawi and Peru gave priority to team training to strengthen consistency of messages among different categories of workers. Peru initially faced the problem of inconsistent, incomplete or confusing messages delivered by workers associated with three separate child health services (well‐baby care, pediatric care for sick children, and nutrition). Malawi faced the challenge of coordinating and aligning activities by the agricultural and nutrition workers in health. Joint health/nutrition and agricultural extension worker trainings were conducted with government and NGO community workers in Malawi and Zambia.

Community mobilization received major emphasis in three of the four programs. Bangladesh, Malawi, and Zambia designed activities and developed materials to engage key members of the family and the wider community in supporting improved complementary feeding. Fathers were found to play a key role in gaining access to diverse foods for children and mothers felt they needed the endorsement of new practices by grandmothers (Malawi, Zambia, and Bangladesh).

3.6. Strengthening frontline worker performance

Several novel approaches were used to motivate workers to improve interpersonal counseling and service quality. The Peru program set up an accreditation system for health centers to emphasize quality and consistency of nutrition messages and acknowledged centers that met the established criteria. A new system of joint training for staff in three types of services was established. For more details on the Peru program see Penny et al. (2005) and Robert et al. (2006). In Bangladesh, BRAC (NGO) workers were supervised using observation checklists; an additional set of mentors was hired at one per 10 volunteers to fill coverage and quality gaps. BRAC hired additional monitors to conduct sample surveys and compiled data from service registers. Cash incentives (ranging from US$ 6–8/month) were given to the volunteers based on the number of mothers practicing recommended IYCF behaviors. More details on the BRAC approach are available in BRAC (2014).

In Zambia, studies showed that agricultural extension workers and health outreach workers had the potential coverage to reach intended beneficiaries. However, knowledge and skills gaps among frontline workers were widespread in Zambia and other countries.

3.7. Policy advocacy

Policy interventions included data and advocacy efforts for shifting the focus of nutrition activities in health services to prevention (all countries), efforts to coordinate across health and agriculture sectors (Malawi and Zambia), utilizing experiences on cross‐sectoral coordination from district coordinating committees to influence national policies (Zambia), and providing proof or evidence that large scale improvement in complementary feeding is possible (all countries). For details on the Malawi program see FAO (2016).

3.8. Outcomes related to complementary feeding practices

All four programs documented improvements in dietary diversity attributable to their respective interventions. In Bangladesh, the greatest improvements took place in areas where coverage was above 90% for home visits combined with 60% for mass media. Changes were also documented in the timely introduction of specific foods, number of meals, and in reduced consumption of unhealthy snacks (Menon et al., 2015). In Malawi, a comparison of baseline and endline surveys showed that dietary diversity in children improved in the food production plus behavior change communication intervention areas but not in food production areas with no behavior change. Qualitative results from focus group discussions with grandmothers and caregivers in Malawi suggested that improved complementary feeding was facilitated through: (a) increased maternal knowledge; (b) children enjoying the taste of enriched porridges; (c) perception of improvements in the child's health; and (d) having supportive grandmothers, fathers, and other community members. In Peru, the evaluation showed that improved counseling at government health centers was effective in changing behaviors; 52% of caregivers in intervention areas reported receiving nutrition advice from the government health service as compared with 24% of caregivers in control health facilities. A significantly higher proportion of children in the intervention group received chicken liver, fish, or egg than did controls at both 6 months and 8 months of age. More children in intervention areas met their dietary requirements for energy, iron, and zinc than did controls. More mothers in the intervention area were able to name three important foods (i.e., chicken liver, eggs, and fish). In Zambia, a comparison of baseline indicators in 2011 and results of a process evaluation survey in 2014 found that dietary diversity rose from 25–30% at baseline to 75–80% in intervention areas; the control areas also improved to 50%. At endline (Harris et al., 2016) the knowledge of timely introduction of complementary foods was significantly higher in the areas where agriculture plus nutrition communication was implemented, compared to the control arm; this was most notable for animal source foods (flesh foods and eggs, where there was an approximate 20 pp greater knowledge regarding the appropriateness of feeding these foods to children 6–8 months of age). The consumption of legumes/nuts was higher in both intervention arms (agriculture alone and agriculture plus nutrition communication) compared to control.

4. DISCUSSION

Behavior change interventions aimed at addressing the determinants of key practices are considered essential components of complementary feeding approaches—including programs that provide food and/or fortificants or use home foods (WHO Global Strategy, 2003). The four case studies presented here and others identified during our search for case studies provide insights into how complementary feeding programs can be designed, implemented, and taken to scale in health and agricultural extension programs. We also learned what problems programs encounter when aiming to improve complementary feeding practices. For example, challenges faced included, the need for health systems strengthening in Peru, need to reach doctors in addition to community‐based workers in Bangladesh, and the need for greater advocacy and closer coordination between agriculture and health/nutrition in Malawi and Zambia.

The case studies identified commonalities and major differences in program design and implementation steps and confirmed that “one‐size‐fits‐all” strategies are particularly unhelpful for complementary feeding, that require addressing different types of barriers and opportunities in varying contexts. However, a set of critical steps was identified that can be used in the process of contextualizing behavior change program design to improve the relevance of solutions.

Five steps for strengthening behavior change interventions are: (a). Select a few priority complementary feeding behaviors. (b). Focus on underlying determinants (including food access) and key influencers of those behaviors. (c). Test concepts, recipes, messages, tools for feasibility/acceptability and clarity. (d). Select program channels to achieve desired coverage, intensity, and scale. (e). Sustain exposure for at least 2 years while continually monitoring and adjusting the program.

4.1. Selecting priority complementary feeding behaviors

An initial step in designing context‐specific complementary feeding programs is to map out the existing practices and prioritize the largest gaps that are amenabe to change. Strategies may also need to specifically address problem behaviors. In Bangladesh, discouraging the use of sugary drinks and unhealthy snacks was part of the strategy for addressing mothers' concerns about children's poor appetite. This is a growing problem (Champeny et al., 2016).

4.2. Focusing on underlying determinants (including food access) and people who influence those behaviors

All programs used data to systematically plan intervention strategies based on determinants of the behaviors and audience perspectives. Among resources for designing complementary feeding programs, Designing by Dialogue (Manoff Group), ProPAN tools, COMBI, the Behave Framework (CORE Group/FHI 360), and barrier analysis methods (Zambia) were highlighted by the program teams. In Ethiopia's ENGINE Project formative research showed that men were the most important stakeholder group because of their control of resources; mothers looked to their husbands for advice. There the strategy focused on promoting specific actions for husbands to support mothers in improving complementary feeding. Emotional appeal is as important as rational messages; the Peru program designed a multi‐channel campaign based on the slogan, ‘Feed your child with love, patience, and humor.’ The emotional appeal of this message was reinforced through many channels and helped to establish rapport between health workers and influential family members.

4.3. Testing concepts, recipes, messages, and tools

Testing was done to address feasibility and logistical issues, to streamline implementation, ensure clarity and comprehension of the materials and messages, and finalize training, supervision and monitoring tools and mechanisms. All programs began with a situational analysis or review of existing data, including gap‐filling new research/assessments and rapid trials and/or pilot testing before launching at scale.

4.4. Selecting program channels for intensity and scale

Lack of adequate intensity during implementation to bring about behavior change can undermine even well designed programs. We found examples of how intensity was increased, for example, by reinforcing the same messages through different media in addition to direct face to face contacts (Bangladesh); engaging multiple levels and types of health services that reach mothers/parents to deliver consistent IYCF messages (Peru); utilizing frontline workers from multiple sectors to deliver IYCF messages (Malawi and Zambia); and reinforcing desirable practices through women's empowerment activities (Zambia). An analysis of the results in Bangladesh showed that the likelihood of improving dietary diversity and meal frequency increased several‐fold when more than one channel was used to deliver messages (Menon et al., 2015); we now recommend at least 5 to 7 different channels of communication to reach mothers with the same reinforcing messages, and 3 to 5 channels for reaching influential people.

To achieve intensity, the Peru program focused on timely and repeated contact with mothers of children 6 months to 24 months of age. To carry out multiple direct contacts with mothers and families required reaching and maintaining adequate coverage by skilled and motivated frontline workers who maintained individual listings of mothers and children. Malawi and Zambia programs mobilized multiple sectors and types of workers, registering individual eligible families and following them up in a timely way, tracking each catchment area, building teamwork among multiple workers and across administrative levels, recognizing good performance to sustain intensity, and maintaining frequent contact with frontline workers through field visits and monthly meetings with managers. Mass media and community mobilization to reinforce interpersonal contacts with individual families accelerated and heightened the impact of programs. Bangladesh used TV spots to emphasize specific practices and to motivate fathers. Ethiopia's ENGINE project used recorded voices to facilitate group discussions. Participant groups in rural communities engaged in “Enhanced Community Conversations” featuring games, role plays, and music on topics that covered complementary feeding and handwashing. Alive & Thrive and ENGINE have also been working with religious leaders in Ethiopia to sensitize them to the importance of dietary diversity, particularly for children under two, and providing support to they can communicate with families about desirable child feeding practices even during community fasting days.

4.5. Sustaining exposure at scale with monitoring and continually adjusting the program

National leadership, partnerships (including a national alliance of nutrition funders and implementers) and mass communication were important for scaling up in Bangladesh. Where mass media has sufficient reach and represents a cost‐effective option, scale can be expanded rapidly. Bangladesh was the only program reviewed here to use mass media as part of its intervention package even though mass media has proven valuable in many public health programs (Wakefield, Loken, & Hornik, 2010). Audiences for mass media were not only mothers but also family members, community influentials, workers, doctors, and national/district decision makers and managers. The total expenditure on mass media was half that of interpersonal communication, and mass media reached an estimated five to eight times more mothers and families of young children. Once designed and tested, television spots can also reach nationwide within a month or two as compared to a much longer period required to scale up interpersonal communication (e.g., 8 months in Bangladesh.)

Following the initial launch, programs continued to evolve, with adjustments made throughout the implementation period. Supplementary studies (Bangladesh, Malawi, and Zambia), program monitoring/quality assurance data in all countries, and midline surveys (Malawi, Zambia, and Bangladesh) were utilized to identify and resolve barriers to behavior change. The need for health system strengthening in Peru came from early monitoring feedback. Team training and accreditation was a part of systems strengthening and helped raise the priority given to preventive nutrition services. Incentives for front line workers linked directly to mothers' adoption of behaviors were effective in Bangladesh. Government services sometimes required reinforcement through NGOs. Some programs relied on NGOs either initially or continuously and primarily to deliver services. In Bangladesh, the program was first launched through BRAC and then scaled up and expanded to government and other partners. In Nepal, the Suaahara program works with 41 local NGOs at the district and community levels. Eight hundred workers, called Suaahara Field Supervisors (SFS), are employed by the local NGOs to extend the implementation capacity of government agencies.

5. CONCLUSION

Complementary feeding practices, in particular dietary diversity, can be improved rapidly in a variety of settings using available program platforms if interventions focus on specific constraints to food access and enable families to prepare and feed appropriate foods. The selection of a few priority behaviors to focus the interventions helped to achieve the desired intensity required for behavior change.

The analysis shows substantial similarities across programs but also some differences. In the programs studied, mothers and caregivers were willing to go outside community norms for the benefit of their child's health and brain development, particularly if recommendations were perceived as being convenient for mothers and caregivers, aligned with family and community norms, and the child appeared to like the food and feeding experience.

The framework based on the well‐known socio‐ecological model provides a useful structure for conducting future comparative analyses and more comprehensive program reviews.

The process of effective program design, implementation and rigorous evaluation outlined here requires resources. A clear, evidence‐based rationale for investing in complementary feeding is needed for decision‐makers to make such investments. Effective strategies and tools can help convince those in the agriculture sector and others to participate in complementary feeding programs, if the tasks are perceived as do‐able. Epidemiological studies have shown that growth in children declines rapidly during the period of complementary feeding from 6 to 24 months of age (Victora et al., 2013). Lassi, Das, Zahid, Imdad, and Bhutta (2013) note that nutritional status has a strong and consistent relation to death from respiratory infections. The association between complementary feeding and diarrheal disease morbidity and mortality is especially strong and has been documented (Islam et al., 2012). Additionally, we now have insights about how to implement the programs. Nutrition program implementers can build on this evidence further.

While we have shown that results are possible in diverse settings, additional human resources, prioritization of nutrition (particularly preventive nutrition), and realistic planning are needed for coordination and alignment across health, agriculture, and sanitation/hygiene sectors. Within the health sector in particular, setting standards of quality and monitoring them, ensuring consistency in IYCF communication across health services, and making time for adequate counseling by health providers can lead to improvements in complementary feeding indicators. Promotion of harmful foods needs to be limited (Champeny et al., 2016).

6. LIMITATIONS

Only a small number of programs met the criteria for case studies included in this study. Programs included here are based on home foods and do not cover programs that distribute cash, food, or nutrient supplements, though asset transfers were involved in the agriculture linked programs. Program impact results on complementary feeding practices that are noted in this paper have been published in the peer review literature for only one case study (Peru) so far. Each program was unique—in terms of context and program approaches—so it was not possible to generalize findings to any great extent. Much of the information on lessons learned, “what works,” and what recommendations might be pertinent to other situations was based on qualitative findings. While the comparison of case studies highlighted some specific areas for improving the quality and coverage of complementary feeding programs, these lessons learned will be further strengthened as additional complementary feeding programs are implemented, evaluated, and documented.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

TS conceptualized and drafted the paper, RS conducted research on country case studies and edited the document, JB and AJ provided technical inputs for the theoretical basis and interpretation of findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Kathryn Reider of World Vision for mobilizing the CORE Group agriculture‐nutrition network (Ag2Nut) to search for complementary feeding program experiences. The following implementing teams provided valuable information and documentation for the four case studies: Alive & Thrive Bangladesh; Ellen Muelhoff and Stacia Noordin of FAO; Rebecca Robert, Mary Penny, and Hilary Creed‐Kaneshiro of the Peru project; Marjolein Mwanamwenge, Danny Harvey, and Gudrun Stallkamp of Concern Worldwide from Zambia's RAIN project and Concern headquarters. The following helped expand the scope of the lessons learned and insights from other program experiences: Karin Lapping and Liz Drummond of Save the Children; Saskia Depee and Dominic Schofield of GAIN; Laura Brye, Pooja Pandey, Nancy Haselow, and Ame Stormer of Helen Keller International; Kristina Beall and Peggy Koniz‐Booher of SPRING; Dennis Lesnick of HARVEST Cambodia.

Sanghvi T, Seidel R, Baker J, Jimerson A. Using behavior change approaches to improve complementary feeding practices. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(S2):e12406 10.1111/mcn.12406

REFERENCES

- BRAC (2014) Scaling up and sustaining support for improved infant and young child feeding: BRAC's experience through the alive & thrive initiative in Bangladesh. Available from: http://aliveandthrive.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/BRAC-Final-report-8.28.2014.pdf

- Caulfield, L. E. , Huffman, S. L. , & Piwoz, E. G. (1999). Interventions to improve intake of complementary foods by infants 6 to 12 months of age in developing countries: Impact on growth and on the prevalence of malnutrition and potential contribution to child survival. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 20(2), 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Champeny M, Pereira C, Sweet L, Khin M, Ndiaye Coly A, Sy Gueye NY, … Huffman, S. L. (2016). Point‐of‐sale promotion of breastmilk substitutes and commercially produced complementary foods in Cambodia, Nepal, Senegal and Tanzania. Maternal & Child Nutrition 12 Suppl 2:126–39. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, K. G. , & Adu‐Afarwuah, S. (2008). Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 4, 24–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2016). IFSN and IMCF project. Dissemination meeting Report. 18th February 2015. Improving food security and nutrition policies and programme outreach (IFSN) and Improving the dietary intakes and nutritional status of infants and young children through improved food security and complementary feeding counselling (IMCF). http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/iycf/malawi/en. Accessed April 19, 2016.

- Fabrizio, C. S. , van Liere, M. , & Pelto, G. (2014). Determinants of effective complementary feeding behaviour change interventions in developing countries. MATERNAL & CHILD NUTRITION, 10(4), 575–592. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Phuong Hong Nguyen, John Maluccio, Adam Rosenberg, Lan Tran Mai, Wahid Quabili, Rahul Rawat. RAIN project impact evaluation report. IFPRI and Concern Worldwide. 2016.

- Imdad, A. , Yakoob, M. Y. , & Bhutta, Z. A. (2011). Impact of maternal education about complementary feeding and provision of complementary foods on child growth in developing countries. BMC Public Health, 11(Suppl 3), S25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M. A. , Ahmed, T. , Faruque, A. S. G. , Rahman, S. , Das, S. K. , Ahmed, D. , … Cravioto, A. (2012). Microbiological quality of complementary foods and its association with diarrhoeal morbidity and nutritional status of Bangladeshi children. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66, 1242–1246. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet series of supplements : 2003. on Child Survival; 2008 and 2013 on nutrition.

- Lassi, Z. S. , Das, J. K. , Zahid, G. , Imdad, A. , & Bhutta, Z. A. (2013). Impact of education and provision of complementary feeding on growth and morbidity in children less than 2 years of age in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, Suppl 3, S13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S13. Epub 2013 Sep 17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon, P. , Saha, K. , Kennedy, A. , Khaled, A. , Tyagi, T. , Sanghvi, T. , … Rawat, R. (2015). Social and behavioral change interventions delivered at scale have large impacts on infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices in Bangladesh. The FASEB Journal, 29(1) Supplement 584. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Nizame, F. A. , Unicomb, L. , Sanghvi, T. , Roy, S. , Nuruzzaman, M. , Ghosh, P. K. , … Luby, S. (2013). Handwashing before food preparation and child feeding: A missed opportunity for hygiene promotion. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 89(6), 1179–1185. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAHO (2003). Guiding principles for complementary feeding of the breastfed child. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guiding_principles_compfeeding_breastfed.pdf

- PAHO (2004). ProPAN: Process for the promotion of child feeding. Washington, D.C: PAHO, © 2004. ISBN: ISBN 92 75 12469. [Google Scholar]

- Penny, M. E. , Creed‐Kanashiro, H. M. , Robert, R. C. , Narro, R. , Caulfield, L. E. , & Black, R. E. (2005). Effectiveness of an educational intervention to improve young child nutrition: A cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 365, 1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert, R. C. , Gittlesohn, J. , Creed‐Kanashiro, H. M. , Penny, M. E. , Caulfield, L. E. , Rocio, N. M. , & Black, R. E. (2006). Process evaluation determines the pathway of success for a health center–delivered, nutrition education intervention for infants in Trujillo, Peru. The Journal of Nutrition, March 2006136(3), 634–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, S. , Haider, R. , Hassan, N. , Pachón, H. , Islam, S. , Jalal, C. S. , … Sanghvi, T. G. (2011). Why does nutrition deteriorate rapidly among children under 2 years of age? Using qualitative methods to understand community perspectives on complementary feeding practices in Bangladesh. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 32(3), 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallkamp G. (2015). Concern worldwide. improving young child feeding through behavior change in realigning agriculture to improve nutrition (RAIN) project in Mumbwa District, Zambia. PowerPoint presentation, presented at: FAO/JLU Technical Meeting: ‘Linking agriculture and nutrition education for improved young child feeding’, July 2015.

- Stokols, D. (1996). Translating social ecological theory in guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10(4), 282–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toure, D. , Rawat, R. , Harvey, D. , Mwanamwenge, M. , & Pelletier, D. (2015). The effects of a nutrition‐sensitive agricultural intervention on social support, food security and maternal self‐efficacy in complementary feeding. April 2015The FASEB Journal, 29(1) Supplement 898. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , de Onis, M. , Hallal, P. C. , Blossner, M. , & Shrimpton, R. (2010). Worldwide timing of growth faltering: revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics, 125, e473–e480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, M. A. , Loken, B. , & Hornik, R. C. (2010). Use of mass media campaigns to change health behavior. Lancet, 376, 1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2003). Global strategy on infant and young child feeding. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/ infantfeeding/9241562218/en [PubMed]

- WHO . (2008). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices, part 1 definitions. Conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6‐8 November 2007 in Washington DC.