Abstract

Evidence supports the establishment of healthy feeding practices early in life to promote lifelong healthy eating patterns protective against chronic disease such as obesity. Current early childhood obesity prevention interventions are built on extant understandings of how feeding practices relate to infant's cues of hunger and satiety. Further insights regarding factors that influence feeding behaviors in early life may improve program designs and outcomes. Four electronic databases were searched for peer‐reviewed qualitative studies published between 2000 to 2014 with transitional infant feeding practice rationale from developed countries. Reporting transparency and potential bias was assessed using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research quality checklist. Thematic synthesis of 23 manuscripts identified three themes (and six sub‐themes): Theme 1. Infant (physical cues and behavioural cues) focuses on the perceived signs of readiness to start solids and the feeding to influence growth and “health happiness.” Theme 2. Mother (coping strategies and knowledge and skills) focuses on the early survival of the infant and the family and the feeding to satisfy hunger and influence infant contentment, and sleep. Theme 3. Community (pressure and inconsistent advice) highlights the importance of generational feeding and how conflicting feeding advice led many mothers to adopt valued familial or culturally established practices. Overall, mothers were pivotal to feeding decisions. Satisfying infant's needs to reach “good mothering” status as measured by societal expectations was highly valued but lacked consideration of nutrition, obesity, and long term health. Maternal interpretation of healthy infant feeding and successful parenting need attention when developing strategies to support new families.

Keywords: infant feeding, mother, obesity, qualitative, systematic review, transitional feeding decisions

1. INTRODUCTION

The first year of life provides the nutritional footprint for future dietary habits and health. Evidence suggests that eating habits are established as young as 2 years of age and like weight, have been shown to track into adulthood (Craigie, Lake, Kelly, Adamson, & Mathers, 2011; Nicklaus & Remy, 2013; Singh, Mulder, Twisk, van Mechelen, & Chinapaw, 2008). Innate food preferences, satiety regulation, and weight predispose of infants are malleable, and how they are expressed is dependent on the environment in which they are exposed (Scaglioni, Arrizza, Vecchi, & Tedeschi, 2011). Parents, in particular mothers, play an important role in what and how food is provided during the early years and focusing within this family environment may provide some answers to the current obesity crisis sweeping the world.

The challenges of changing established behavior and the limited impact of childhood healthy lifestyle and obesity prevention interventions (Waters et al. 2011) reinforce the current preventative investment by governments and academics in supporting healthy eating practices and addressing obesogenic factors within the first years of life (Hesketh & Campbell 2010). Interventions that focus on diet quality and parental responsiveness to feeding cues are promising strategies in reducing the risk of obesity in early life (Redsell et al. 2016). The relationship between child temperaments, maternal feeding (e.g., feeding to soothe), and weight gain should also be considered (Bergmeier, Skouteris, Horwood, Hooley, & Richardson, 2014).

Feeding choices (e.g., formula versus breastmilk), timing (e.g., early introduction of solids), and quantity have all been implicated as risk factors in the development of poor dietary habits and/or subsequent health issues such as obesity (Birch & Ventura, 2009; Pearce & Langley‐Evans, 2013; Pearce, Taylor, & Langley‐Evans, 2013). Parental infant feeding practices and styles which describe how food is provided have also been identified as detrimental to childhood development, specifically those practices and styles that are more controlling and unresponsive to infant feeding cues (Birch & Davison 2001). In contrast, parenting and feeding styles characterized by high demandingness and responsiveness around eating (e.g., authoritative) have been found to be associated with healthier dietary intakes (e.g., increased fruit and/or vegetable) and be protective of child overweight, while strict (e.g., authoritarian) or indulgent parenting are negatively associated with health outcomes (Vollmer & Mobley 2013).

Current early childhood nutrition interventions are frequently based on responsive feeding practices (Daniels et al., 2015; DiSantis, Hodges, Johnson, & Fisher, 2011; Hurley, Cross, & Hughes, 2011); however, recruitment and participation issues (Ciampa et al. 2010; Daniels et al. 2012) suggest a lack of appreciation of the context in which feeding behaviours develop and/or the needs of parents. The origins of feeding practices are inextricably intertwined with the social and cultural factors that govern family life (Warin, Turner, Moore, & Davies, 2008).

While for many, motherhood signals a time of celebration and excitement for the journey ahead, it is colored by family, cultural, and societal expectations. With the medicalization of motherhood, behaviors that deviate from expert guidance are deemed as risky by health practitioners and subsequently by mothers as a threat to their identity as good mothers (Knaak 2010). In an emotionally charged postpartum arena where infant feeding is a key element, mothers may be left to defend their choices if they are inconsistent with recommendations, such as the early use of formula or solids (Lee 2008). While the roots of scientific guidance to regulate motherhood are not new, maternal accounts suggest that practitioners fail to consider the full circumstances around infant feeding choices, resulting in many mothers feeling judged, withholding information and/or disregarding advice (Heinig et al. 2006; Lee 2007).

Infant feeding research to date has focused on measuring and understanding breastfeeding practices to meet policy guidelines. While some papers focus on the timing of introducing solids (Wijndaele, Lakshman, Landsbaugh, Ong, & Ogilvie, 2009), there is much less emphasis on understanding the factors that influence the timing, choices, and process of moving to family foods. Given that the transitional infant feeding period has been linked to the development of food preferences, dietary patterns, and obesity in childhood and later life (Birch & Ventura 2009; Grote & Theurich 2014), further research about this “feeding window” is required.

With the current attention on childhood obesity and the rise in early childhood strategies to support the development of healthy lifestyle behaviors, the aim of this systematic review is to collate qualitative insights of factors mothers' use to guide decisions about transitional infant feeding. The results from this systematic review will present practitioners and researchers with additional information to consider when developing interventions to support healthy family feeding in addition to identifying potential research gaps. The main objective of this review is to identify the rationale of maternal infant feeding practices when transitioning from milk feeds to family foods.

Key messages.

Mothers are pivotal to transitional feeding decisions however many struggle to interpret infant feeding cues.

Many mothers use food to influence infant growth, contentment and sleep.

Mothers choose ease of feeding over infant feeding recommendations.

Maternal identity and parenting success are associated with infant feeding practices.

Obesity and long term health rarely influence feeding decisions.

The rationale for transitional feeding practices is underreported in the literature and requires further research to identify best avenues for supporting healthy infant feeding practices.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy and study selection

PubMed, Embase, CINHAL, and PsycINFO were searched for papers published between January 2000 and June 2014 using key words, subject headings, and MeSH terms. This timeframe was chosen as it was thought it would capture the current social context around infant feeding. All search strategy results were entered into Endnote X7© (Thomason Reuters 2013). The reference lists of included papers were searched to identify further relevant papers. Papers were included if they were full text, English written, peer reviewed journal articles based on qualitative studies in developed countries investigating parental rationale on transitional feeding practices (i.e., transition from milk diet to family foods) in children less than 2 years of age. Reporting on children less than 2 years was chosen as this age was more relevant to the transition to family foods, and it was felt that parent recall would be more accurate when discussing infant feeding. Papers were excluded if they were solely quantitative studies, only contained health professional views, or if the parental feeding rationale was based on breastfeeding or formula feeding only, preterm infant feeding, food allergies or coping with feeding problems (e.g., disabilities).

The search strategy is outlined in Table 1. The lead author together with a librarian experienced in systematic reviews verified the search terms and review process. Titles and abstracts were reviewed and discarded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Two members of the research team reviewed the remaining full‐text articles.

Table 1.

Search terms used in the systematic literature review search

| infant* OR infant OR preschool* OR child, preschool: AND |

| parent* OR parents OR mother* OR mothers OR father* OR fathers OR caregiver* OR caregivers; AND |

| feeding behaviour* OR feeding behavior* OR feeding behavior OR diet* OR diet OR breastfeed* OR breast feed* OR bottlefeed* OR bottle feed* OR breastfeeding OR bottlefeeding OR wean* OR weaning OR “complementary feed*” OR “infant nutritional physiological phenomena” OR nutrition OR food* OR food; AND |

| perception* OR perception OR attitude OR attitude to health OR aware* OR awareness OR feeling* OR understand* OR knowledge* OR opinion* OR belief* OR view* OR perspective* OR “health knowledge, attitudes, practice OR practice*”; AND |

| qualitative OR focus group* OR interview* OR qualitative research* OR qualitative research OR “semi‐structured” OR semistructured OR unstructured OR informal OR “in‐depth” OR indepth OR “face‐to‐face” OR structured OR guide OR guides AND interview* OR discussion* OR questionnaire* OR “focus group” OR “focus groups” OR qualitative OR ethnograph* OR fieldwork OR “field work” OR “key informant” OR “interviews as topic” OR “focus groups” OR narration OR qualitative research |

2.2. Data extraction, analysis, and synthesis

Thematic analysis as described by Thomas and Harden (Thomas & Harden 2008) was used to identify emerging themes and sub‐themes across the data. This approach was chosen as it describes the synthesis of qualitative research explicitly used in systematic reviews. The level of analysis in this study was descriptive. The analysis process involved multiple readings by the lead author of the identified published papers followed by the manual line‐by‐line coding of the each study's findings. Coded text was then extracted and organized into related areas to construct descriptive themes. The text was then grouped into sub‐themes to best describe the maternal rationale around transitional feeding. Synthesis of data across studies was used to identify common concepts across settings and different ethnic groups. Any feeding practices predominant in particular settings or groups were noted. The final descriptive mapping of the main themes was subsequently discussed with the research team to reach consensus about the main constructs.

2.3. Data reporting and study quality assessment

Reporting of this systematic review follows the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) framework (Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, 2012) with each paper assessed using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007). The ENTREQ framework guides the reporting of findings into the domains of introduction, methods and methodology, literature search and selection, and appraisal and synthesis of findings. The 32 item checklist in the COREQ guides the reporting of the research team, study methods, context of the study, findings, analysis, and interpretations. These key reporting guidelines were identified through the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research Network (EQUATOR network 2015) and the Cochrane Collaboration (The Cochrane Collaboration 2015).

The COREQ assessment was used to identify completeness of reporting and potential of bias in the qualitative studies. Assessment of paper inclusion was based on the research team appraisal of this data as to whether studies provided sufficient information. The authors also subscribed to the belief that there is the risk of losing new insights if studies were excluded due to methodological or reporting shortfalls (Hannes 2011).

3. RESULTS

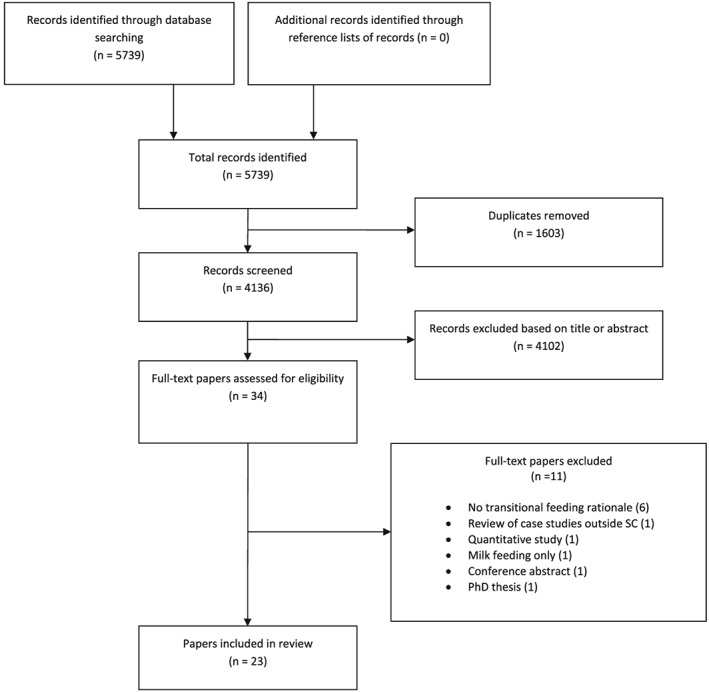

A total of 5739 papers were identified with the search strategy. The titles and abstracts were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 5705 references were discarded because they were duplicates and/or were outside the scope of this review. A total of 34 full‐text articles were reviewed, and a further 11 were discarded as they were outside the inclusion criteria, leaving 23 papers. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA (Panic, Leoncini, de Belvis, Ricciardi, & Boccia, 2013) flow diagram for this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection

The included papers were from the US (13), Europe (9), and Australia (1). Further details about the papers can be found in Table 2. Focus groups and interviews were used in equal proportions in the studies, with some studies using both methods and three using cross‐sectional qualitative survey data. The majority of participants were mothers, with fathers and extended family members included in six papers.

Table 2.

Study details of the journal papers used in the systematic literature review

| Author, Year published and Country | COREQ Score | Aim | Method and Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afflerback et al (Afflerback et al. 2013), 2013, US | 19 | To examine meanings attached to infant food and feeding‐related consumer items. | 14 in‐depth interviews—mostly white, middle class women with their first child 3–12 months old. | Intense mothering—baby led feeding; health driven product choices; convenience and price influence choices; good mother meets needs. |

| Anderson et al (Anderson et al. 2001), 2001, UK | 21 | To identify factors influencing weaning decisions. | 5 focus groups—29 mothers (mean 27 years of age) with babies (mean 13 weeks old), 10 feeding solids (mean 11.6 weeks old). | Solids timing baby led; feed to settle; trial and error; emotional journey; decisions made on child and not guidelines; inconsistent advise. |

| Arden (Arden 2010), 2010, UK | 14 | To examine the factors after the change in the recommendations to delay the introduction of solid foods until 6 months of age. | Open‐ended questions from a cross‐sectional electronic survey—105 mostly white, educated mothers, 22–45 years of age (mean 32.3) with child 26–155 weeks old (mean 80 weeks). | Baby‐led feeding; feed to settle; maternal instinct; weaning stressful; pressure from family; competition from peers; inconsistent advice. |

| Bramhagen et al (Bramhagen et al. 2006), 2006, Sweden | 20 | To describe parents' experiences concerning feeding situations. | 18 in‐depth interviews ‐ mothers of 1 year olds who differed in age, education, ethnicity and number of children. | Parent success based on child intake; positive feeding experience parent more responsive, negative parent more controlling. |

| Chaidez et al (Chaidez et al. 2011), 2011, US | 20 | To identify behaviours, influences and attitudes that reflects feeding styles in Latino parents with young children. | 18 in‐depth interviews—14 Mexican born mothers, 4 U.S. born, 21–36 years of age (mean 26 years) and toddlers, 12–46 months old (mean 20). | Indulgent baby‐led feeding; weight an indicator of successful parenting; poor guideline knowledge; follow family advice. |

| Corbett (Corbett 2000), 2000, US | 20 | To explore practices as well as the values, attitudes and beliefs associated with infant feeding of low income black women. | 8 interviews during infant's first year of life—10 low income black mothers (18–27 years) with infants enrolled in Medicaid and WIC program. | Baby‐led feeding; feed to settle; early weaning and adding cereal and strained foods to bottle feeds generational practices; poor support. |

| Heinig et al (Heinig et al. 2006), 2006, US | 17 | To understand why non optimal infant‐feeding practices occur among low‐income women despite WIC support. | 8 focus groups—28 English‐speaking and 37 Spanish‐speaking WIC program mothers with infants 4–12 months old. | Baby‐led feeding; feed to modify behavior; feed to fill; higher infant weight sign of health; mixed support; advice not always followed. |

| Higgins (Higgins 2000), 2000, US | 22 | To examine the cultural beliefs and practices that influence feeding practices. | Observation followed by 3 interviews over a year—10 Puerto Rican participants (5 mothers, 2 grandmothers, and 3 fathers) with infant under 4 months old. | Big is beautiful; thinness a reflection of poor parenting; overfeeding common; food added to bottle to boost weight; family taught feeding. |

| Hodges et al (Hodges et al. 2008), 2008, US | 13 | To examine responsiveness of maternal feeding to infant cues and other factors in initiation and termination of feeding. | Open‐ended questions from a cross‐sectional observational study—71 ethnically diverse mothers of infants at 3, 6 or 12 months old. | Infant cues guide feeding decisions; less salient as child ages; overt cues mostly used with risk of over/underfeeding. |

| Horodynski et al (Horodynski, M et al. 2007), 2007, US | 23 | To assess low income mothers knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and family norms about infant feeding. | 6 focus groups—23 low income mothers (12 Caucasian, 9 Black, 2 biracial), 17–41 years of age (mean 28 years) with infants 3 weeks–12 months old. | Healthy infant when happy and eating well; feed to settle; skeptical of guidelines harm/exceptions; family pressure to feed early. |

| Horodynski et al (Horodynski, MA et al. 2009), 2009, US | 21 | To ascertain expectations and experiences with mealtimes and feeding of toddlers of low income African American mothers. | 2 focus groups—27 low income African American mothers (19–50 years of age) of toddlers (12–36 months old). | Healthy when eat well and happy; feed to fill not for health; cost a barrier to healthy foods. |

| Kahlor et al (Kahlor et al. 2011), 2011, US | 17 | To explore the nutritional challenges parents face in raising their children. | 6 focus groups—African American (7 mothers and 9 fathers) , Hispanic (8 mothers and 6 fathers), and Caucasian (7 mothers and 6 fathers). | Cultural, family, time and money challenges to raising healthy children; need strategies to maintain traditions and build food preparation skills. |

| Kaufman et al (Kaufman & Karpati 2007), 2007, US | 18 | To understand the childhood obesity epidemic among Latino sub‐group. | Individual and group interviews and participant observation—12 mothers, 3 fathers/boyfriends, and extended members from 12 families. | Overweight acceptable if health OK; heavier child safer; feed to settle and keep happy; family intimacy expressed through food. |

| Lovelace et al (Lovelace & Rabiee‐Khan 2013), 2013, UK | 17 | Investigated influences on the diets of young children in families on a low income. | 11 in‐depth interviews ‐ mothers 19–25 years of age of pre‐school children (mean age 22 months). | Early feeding driven by infant hunger; insufficient knowledge or skill to translate healthy eating into practice; trust commercial produce aimed at infants. |

| McDougall (McDougall 2003), 2003, UK | 13 | To determine factors or influences predisposed to early weaning and principle sources of advice on weaning. | 5 focus groups, 10 individual in‐depth interviews and self‐reported questionnaires with open ended questions—first time mothers (16‐41 years of age) of infants. | Unrealistic expectations of sleep; feed to settle; family pressure to wean early; conflicting advice. |

| McGarvey et al (McGarvey et al. 2006), 2006, US | 14 | To determine parental perceptions, attitudes, knowledge, beliefs and barriers to infant and child feeding practices and preferred information sources. | 4 focus groups—6 African American, 8 Caucasian, 6 Hispanic, and 5 Vietnamese mothers from either WIC or Head Start programs. | Immediate health/appetite more important than weight issues; food used to shape behavior; solids introduced early and overfeeding common; family taught feeding. |

| Nielsen et al (Nielsen et al. 2013), 2013, Denmark | 16 | To investigate parental concerns, attitudes and practices during earlier and later phases of complementary and young child feeding. | 8 focus group—45 mothers of children 7–13 months old, groups were segmented according to the child age and maternal educational level. | Immediate health feeding focus; feed to satisfy hunger and promote sleep; guidelines used for safety early, less relevant as child ages. |

| Omar et al (Omar et al. 2001), 2001, US | 18 | To assess nutritional needs and barriers in establishing healthy eating habits in toddlers. | 3 focus groups were conducted with rural, low‐income caregivers—12 men 17–42 years of age (mean 27 years) and 8 women 22–48 years of age (mean 30 yrs), mostly Caucasian. | Time challenges to food preparation; food consumption focused on quantity and not quality; limited nutrition knowledge; family beliefs reign; early feeding endorsed. |

| Redsell et al (Redsell et al. 2010), 2010, UK | 21 | To explore parental beliefs concerning infant size, growth and feeding behavior. | 6 focus groups in different demographic areas—36 women and 2 men, 19–45 years (mean 30.1 years) with infants 1–11 months old (mean 5.51 months). | Bigger baby is healthier; feed to settle; unconvinced by 6 months solids guideline; family pressure to top up feeds and wean early. |

| Schwartz et al (Schwartz et al. 2013), 2013, France | 19 | To describe practices, attitudes and experiences of French mothers in relation to weaning with a focus on vegetables. | 4 focus groups and 3 individual in‐depth interviews—18 mothers 32.2 ± 4 years from mainly higher socio‐economic groups. | Baby‐led feeding over inconsistent advice; food used for pleasure and to develop palate; cultural practice of adding food to bottle. |

| Synnott et al (Synnott et al. 2007), 2007, Germany, Italy, Scotland, Spain and Sweden | 16 | To gain insight into parental perceptions of infant feeding practices in five European countries. | 15 focus groups (3 per centre/country)—108 parents with infants up to 12 months old. | Baby‐led feeding; formula and early solids to influence behavior; convenience over healthier food options; variable guideline acceptance, variable health and lay influence. |

| Waller et al (Waller et al. 2013), 2013, US | 18 | To explore interactions between mothers and infants that may influence development of feeding practices. | 15 in‐depth phone interviews—low income, primiparous mothers in their mid‐20s with infants <12 months old (mean 5.2 months). | Guessing game initially based on positive responses to feeding (e.g., growth, sleep) which overshadow guidelines; overfeeding risk. |

| Zehle et al (Zehle et al. 2007), 2007, Australia | 15 | To explore childhood obesity through mothers' perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours. | 16 in‐depth interviews ‐ primiparous mothers 25–36 years of age, range of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, 9 ethnic groups, mostly university educated with children 0–2 years old. | Baby‐led feeding; immediate health and child contentment focus; unconcerned obesity risk; salience of guidelines; culturally loaded advice; health advice early helpful, later prescriptive. |

Note: COREQ = Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research; WIC = Women, Infants and Children.

Table 3 outlines the completeness of reporting and potential bias in the 23 papers based on the COREQ checklist (Tong et al. 2007). Overall the papers captured between 13 and 23 of the 32 checklist items, with 78% (18) reporting on at least half of the checklist (Table 2). Most papers identified the researcher but failed to provide details of their experience or relationship with the participants. Research method and sample were clarified; however, theoretical base and non‐participation were rarely reported. The theoretical base provides a guide to interpreting the data, and reasons for non‐participation provide further weight to statements made. Description of the analysis was reported in the majority of the papers. No major flaws in the studies were detected, and all papers were included given that they provided sufficient detail of the research undertaken.

Table 3.

Study reporting assessment based on COREQ checklist

| Reporting criteria | Number of studies reporting criteria |

|---|---|

| Research team and reflexivity | |

| Interviewer identification | 21 |

| Credentials | 21 |

| Occupation | 8 |

| Gender | 17 |

| Experience and training | 3 |

| Relationship established | 2 |

| Participant knowledge of interviewer | 1 |

| Interviewer characteristics | 4 |

| Study design | |

| Methodological theory identified | 10 |

| Sampling method | 23 |

| Method of approach | 22 |

| Sample size | 23 |

| Number/reasons for non‐participation | 3 |

| Setting of data collection | 15 |

| Presence of non‐participants | 6 |

| Description of sample | 23 |

| Interview guide | 15 |

| Repeat interviews | 2 |

| Audio/visual recording | 3 |

| Field notes | 10 |

| Duration | 14 |

| Data saturation | 2 |

| Transcripts returned to participants | 0 |

| Analysis and findings | |

| Number of data coders | 20 |

| Description of coding tree | 16 |

| Derivation of themes | 23 |

| Software | 9 |

| Participant checking | 1 |

| Participant quotations presented | 22 |

| Data and findings consistent | 23 |

| Clarity of major themes | 23 |

| Clarity of minor themes | 14 |

Note: COREQ = Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research.

Overall, the studies provided a few insights into the drivers of mothers' choices when moving from milk feeds to family foods because of two key reasons. First, many of the papers focused on milk feeding determinants, with the transitional diet captured mainly in the timing of introducing solids and to a lesser degree, the food choices made. Second, not all papers clearly described the basis for infant feeding choices or clarified the predominant influencing factors of infant feeding practices.

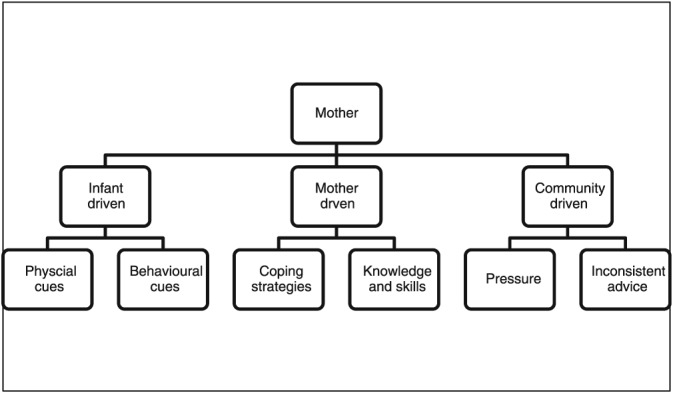

Despite the limited data available, it was possible to identify three major themes that represented the main focus of the drivers of mothers' infant feeding practices: (1) Infant driven transitional feeding practices; (2) Mother driven transitional feeding practices; and (3) Community driven transitional feeding practices. These themes are consistent with the dimensions identified in Birch and Venture's ecological model for childhood obesity etiology (Birch & Ventura 2009) which shows how a child's weight is influenced by the child's behavior that is embedded within the family and community context. Two minor sub‐themes were identified for each major theme: (1) physical cues and behavioural cues; (2) coping strategies and knowledge and skills; and (3) pressure and inconsistent advice. The relationships between the mothers and the themes are presented in Figure 2, highlighting that all data is captured and translated through the mother.

Figure 2.

Systematic review themes and sub‐themes relationships

3.1. Infant driven transitional feeding practices

This theme covers infant's signs of readiness for solids and how these are interpreted by the mother.

3.1.1. Physical cues

It was common for mothers to identify introduction of solids as an important developmental milestone (Horodynski et al., 2007; Schwartz et al., 2013). With infant survival at the forefront of mothers' minds in the early feeding stages (Waller, Bower, Spence, & Kavanagh, 2013), the introduction of solids was guided by the perceived physical signs of readiness such as the ability to sit, the presence of teeth and being able to control swallowing (Anderson et al. 2001; Schwartz et al. 2013). Age and size were also reported to be markers for timing of the introduction of solids (Anderson et al. 2001).

Growth was viewed as a measure of health (Anderson et al. 2001; Corbett 2000), with insufficient growth being a source of concern for many mothers (Heinig et al. 2006) leading to supplementation with infant formula and/or early weaning to solids (Arden 2010; Higgins 2000; Redsell et al. 2010; Waller et al. 2013). Weight was seen a safety net as illustrated in Kaufman and Karpati's study (“He should be fatter. He's so fragile.”) (Kaufman & Karpati 2007, p2186). Inappropriate feeding was used to influence growth (“I gave the baby cereal for the first time when the baby was 3 months, because the baby was very skinny and I wanted to see the baby a little fat.”) (Heinig et al. 2006, p32) and to negate concerns of underweight.

Bigger, chubbier babies tended to be viewed as healthier, normalized in the family context and fed accordingly to achieve this status through adding formula, early solids and/or cereal to bottles (Chaidez, Townsend, & Kaiser, 2011; Higgins, 2000; Kaufman & Karpati, 2007; Redsell et al., 2010). The cultural value of heavier children and feeding practices was portrayed in Higgins's study of Puerto Rican families in New York where “mothers often feed babies until they spit up….Lots of mothers feed babies extra milk and put extra sugar and baby foods in a bottle with a big hole in the nipple” (Higgins 2000, p24).

A heavier infant was seen as safer (Kaufman & Karpati 2007) and a sign of good parenting (Higgins 2000). Overall, obesity concern was not evident, with weight seen as a problem for childhood post infancy, something the infant can grow out of, and only addressed if there is an associated health problem (Kaufman & Karpati 2007; McGarvey et al. 2006; Redsell et al. 2010). While preference for heavier babies was more apparent in overweight parents and/or cultural groups such as Latino‐Americans (Chaidez et al. 2011), Redsell et al. reported this predisposition in mothers from both affluent and deprived localities in the UK as reflected in the quote “I was quite happy that he was getting a little bit podgy” (Redsell et al. 2010, p6).

3.1.2. Behavioural cues

The infant showing interest in food, expressed by looking or reaching for food, was a common reason for starting solids (Anderson et al., 2001; Arden, 2010; Heinig et al., 2006; Hodges, Hughes, Hopkinson, & Fisher, 2008; Synnott et al., 2007; Waller et al., 2013; Zehle, Wen, Orr, & Rissel, 2007). As captured in Heinig et al's (Heinig et al. 2006) study, mothers had no preconceived plans around when to introduce solids (“I didn't really know exactly when [to introduce solids] or I really didn't know. I thought I'd just go off it when she gave me the cue.”) (p31) and were led by their infants (“I think they let you know themselves. They kind of know. They kind of, like, grab: ‘Can I have some of that too?’”) (p35).

Facial expressions and oral behavior such as chewing also prompted mothers to introduce solids (Anderson et al. 2001; Arden 2010; Heinig et al. 2006; Hodges et al. 2008). Happiness and contentment were identified as measures of health which supported maternal decisions to introduce solids early, and in some cases overfeed (Anderson et al., 2001; Corbett, 2000; Horodynski et al., 2007; Horodynski, Brophy‐Herb, Henry, Smith, & Weatherspoon, 2009; Waller et al., 2013).

Absence of acute disease or distress was used as markers for safe early feeding (Anderson et al. 2001; Corbett 2000) with adverse long‐term health outcomes being difficult for mothers to conceptualize (Anderson et al. 2001). Satisfying immediate concerns of the infant reinforced parenting abilities (Hodges et al. 2008). In this context, mothers fed based on infant cues of food enjoyment or perceived enjoyment. Crying, while also a physical cue and related to contentment, has been categorized in the subtheme ‘coping strategies’ under the theme ‘mother driven’ due to the relationship with behavior change beyond hunger.

3.2. Mother driven transitional feeding practices

This theme reflects maternal personal capacity to manage infant feeding.

3.2.1. Coping strategies

The use of formula and early solid feeding to manage negative aspects of infant behavior was highlighted in many of the papers. This was especially evident in the relationship between hunger, crying and sleep, where mothers identified crying and/or inadequate sleep as markers of hunger (Anderson et al., 2001; Heinig et al., 2006; Horodynski et al., 2007; Lovelace & Rabiee‐Khan, 2013; McDougall, 2003; Nielsen, Michaelsen, & Holm, 2013; Redsell et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2013; Synnott et al., 2007; Waller et al., 2013).

Some mothers used feeding practices such as topping up with formula feeds or introducing solids as coping strategies to settle the child (“like comfort food. If you give a baby food they will eat it”) (Anderson et al. 2001, p475) (Corbett 2000; Redsell et al. 2010; Synnott et al. 2007) or to avoid perceptions of spoiling by frequently picking up the unsettled child (Corbett 2000) rather than to relieve hunger. These practices were reinforced by positive responses such as adequate infant sleep (“I started to wean her because she started to wake up at night”) (Redsell et al. 2010, p5). The addition of cereal to bottle‐feeds to reduce feeding frequency and increase length of sleep was also reported (“I do it to help her sleep through the night”) (Horodynski, M et al. 2007, p109). Feeding to fill, measured in some cases by infant spitting up, was a common practice amongst mothers, particularly African Americans and Latino Americans (Heinig et al., 2006; Higgins, 2000; Horodynski et al., 2009; McGarvey et al., 2006) as summed up by a mother in Heinig et al's study “If he didn't finish the jar of baby food, I put it in his night‐time bottle” (Heinig et al. 2006, p32).

Maternal coping strategies were also affected by time stresses and financial resources. Infants were often fed separately from the family in a variety of locations so that their needs could be met while fitting into family life (e.g., in a car seat and in the bathroom while bathing other children) (Horodynski et al. 2007; Kaufman & Karpati 2007). Convenience and time pressure also influenced food choices, with quick meal choices that satisfied hunger winning out over healthier options (Omar, Coleman, & Hoerr, 2001; Synnott et al., 2007). While cost was found to influence food choices especially in low income families (Afflerback, Carter, Anthony, & Grauerholz, 2013; Kahlor, Mackert, Junker, & Tyler, 2011; Kaufman & Karpati, 2007; Lovelace & Rabiee‐Khan, 2013; Omar et al., 2001), food was also seen as a relatively inexpensive commodity that had immediate satiety effects (Horodynski et al. 2007). “Eating right” for many mothers meant satisfying needs (generally not nutritional), with food an accessible commodity used by families to gratify their children (Horodynski et al. 2007; Kaufman & Karpati 2007).

Feeding was found to be an emotional journey, described by a range of feelings and related to many of the strategies outlined earlier to pacify the child. Some mothers were eager to start feeding solids and expressed pride in this achievement (Anderson et al. 2001; Corbett 2000; Synnott et al. 2007), while others found the transition to solids a stressful experience (Schwartz et al. 2013). Many mothers were concerned about their infant eating sufficient food with overfeeding as a common solution (Heinig et al. 2006; Higgins 2000; Kaufman & Karpati 2007). Inappropriate feeding such as starting solids early, while associated in some cases with guilt, was justified by positive infant behavior of enjoyment and contentment (Anderson et al. 2001). In fact, success in feeding was measured by some mothers by the amount of food eaten and weight gained (Chaidez et al. 2011; McGarvey et al. 2006; Redsell et al. 2010). Parenting skills were found to be judged by both family and the parents themselves on feeding choices and consumption with “good parents” seen to satisfy infant needs (Afflerback et al., 2013; Bramhagen, Axelsson, & Hallström, 2006; Higgins, 2000; Kaufman & Karpati, 2007) as illustrated by the quote “that's probably the worst feeling in the world, for a mom to think that your baby is not properly nourished or full” (Heinig et al. 2006, p32).

3.2.2. Knowledge and skills

Despite good awareness of the infant feeding guideline around when to introduce solids, meeting the infant's immediate needs took priority (Anderson et al. 2001; Synnott et al. 2007; Waller et al. 2013). This is embodied in comments from the work of Synnott et al (“The guidelines are good, but it's important that you listen to your child”) (Synnott et al. 2007, p951) and Arden (“Try and be guided by when your baby seems ready. Guidelines are just guidelines and every baby is different…Your baby knows best!”) ((Arden 2010, p165) where mothers advocate for an infant led feeding approach to introducing solids.

Certainly maternal acceptance of the guidelines varied with many not convinced of potential harm of feeding practices out of step with recommendations (Horodynski et al. 2007; McDougall 2003). Some described the guidelines as too rigid, declaring that every infant was different, and the guidelines did not apply to all infants such as those that did not sleep through the night (Anderson et al. 2001; Arden 2010; Heinig et al. 2006; Horodynski et al. 2007). The guidelines were seen as early safety rules that lose relevance as the infant transitions to family foods (“more to tell you what they may become sick from”) (Nielsen et al. 2013, p1159).

While there was an awareness of the need for healthy foods, many mothers lacked the knowledge and skills to translate this into feeding practices beyond fruit and vegetable consumption (Lovelace & Rabiee‐Khan 2013; Schwartz et al. 2013). It was common practice for semisolids such as cereal, yoghurt, and strained foods to be fed early by bottle, particularly by mothers from the US and France (Anderson et al. 2001; Corbett 2000; Heinig et al. 2006; Schwartz et al. 2013). These foods were not considered as solids by the mothers (Anderson et al. 2001; Heinig et al. 2006; Horodynski et al. 2007), and feeding by bottle was an acceptable cultural practice to make feeding time easier and assisted transition to spoon‐feeding and family foods (Higgins 2000; Schwartz et al. 2013). The health of the infant was considered by those who chose organic foods despite poverty in some cases (Afflerback et al. 2013; Anderson et al. 2001) or those seeking to reduce allergy or gut problems (Afflerback et al. 2013; Arden 2010). Reducing the risk of obesity was not considered a high priority in feeding practices, with unhealthy foods only restricted if the child was accepted as overweight (Zehle et al. 2007).

Food preparation skills also influenced the variety of food offered with some mothers doubting their cooking ability. Younger parents, especially the more vulnerable ones, were unable to cook meals at home (“My parents cooked, they cooked really nice home meals but I don't know how to do them”) (Redsell et al. 2010, p8). Many trusted commercial infant foods to be nutritionally sound and cheaper than family food and were confused about the role of family food in the infant's diet (“I didn't realise I could put her straight on to normal food”) (Lovelace & Rabiee‐Khan 2013, p5).

3.3. Community driven transitional feeding practices

Information under this theme includes influence by those external to the mother and infant and how it is interpreted by the mother.

3.3.1. Pressure

The main pressure parents experienced on infant feeding practices was from the family. Feeding practices were found to be generational and mainly family taught with unsupportive breastfeeding environments and the endorsement of formula, early feeding of solids, and overfeeding apparent in many of the studies (Anderson et al. 2001; Higgins 2000; Omar et al. 2001; Zehle et al. 2007). For example, this pressure was related to the insufficiency of milk (“My grandmother, she tell me to give the baby cereal. She said she needed it and would sleep longer. She say ‘she hungry cause she just drinking milk and that milk can't fill her up that much.’”) (Corbett 2000, p78) or solids (“I'm worried about the amount he eats, but mum always tells me to give him more”) (Zehle et al. 2007, p40). Pressure was also found to be non‐verbal in nature (“’Well yeah you know in the books now it doesn't say to start weaning until six months anyway’, but she looked at me gone out, like ‘oh no she's only been milk, she's only been fed by milk’”) (Redsell et al. 2010).

While many mothers adhered to family advice, it was viewed by some, especially older mothers, as being outdated and thus disregarded (Arden 2010; McDougall 2003; Synnott et al. 2007). Food provided by family was also not always healthy (Kaufman & Karpati 2007; Omar et al. 2001), and the pressure to adhere to family norms was reflected in healthy eating being viewed as a rejection of family and ethnic heritage (Kahlor et al. 2011).

Despite mothers' groups being valued for their diversity of experiences in raising a child (Zehle et al. 2007), peer pressure to introduce solids as a signal of advanced development was evident (“It seems to be a competition among new mums who can get their baby onto solids the quickest”) (Arden 2010, p164). It was clear that advice from family and friends, while not always sought, was influential on infant feeding practices (Afflerback et al. 2013; Bramhagen et al. 2006; Corbett 2000).

3.3.2. Inconsistent advice

Sources of information around infant feeding were identified as professional (e.g., nursing, medical, and allied health) and lay (e.g., family and friends), as well as industry (e.g., food labels) (Anderson et al. 2001; Arden 2010; McDougall 2003). While some advice was influential in feeding, for example, food label age range around when to start solids (Lovelace & Rabiee‐Khan 2013), conflicting advice was detrimental in many cases, for example, breastfeeding cession (Zehle et al. 2007).

With differences in opinions about optimum infant feeding, many mothers were left confused and chose to learn by personal experience (Heinig et al. 2006; Synnott et al. 2007). Some found this process easier (“A lot of information available on infant feeding is contradictory. Each child is a world in himself and it is better to learn from one's own experience with the infant”) (Synnott et al. 2007, p951) than others (“You get a lot of conflicting advice even from different health visitors…I know all babies are different and they can't give strict guidelines, but it's very confusing”) (McDougall 2003, p26).

In summary, mothers stated that health professional advice was not always consistent with infant feeding guidelines, with formula given in hospital and formula supplementation, and early solids endorsed by some practitioners (Arden 2010; Corbett 2000; McDougall 2003; Redsell et al. 2010). Mixed messages left some mothers choosing the advice which suited them (Bramhagen et al. 2006), disregarding advice if they did not like it, they did not find it useful or it conflicted with family beliefs (Heinig et al. 2006; McDougall 2003) as summed up by two mothers “We do what works for us … how it fits in with our ideas.” “You take what's right for you and use it.” (Zehle et al. 2007, p40).

4. DISCUSSION

This review aimed to identify insights into maternal feeding practices in the transition from milk feeding to family foods. A total of 23 papers from nine countries that met the inclusion criteria were identified. The studies were generally well described to provide a good understanding of the target group, the sampling method, the research approach, and the analysis framework. They provided insights into the rationale that informs mother's decisions around transitional feeding in infancy.

Many mothers embraced an infant led approach to feeding solids, using developmental signs of readiness such as age, size, ability to sit, and interest in food to guide their feeding approaches, including when and how much to feed. The inappropriate use of food to promote development and contentment in this review would suggest a misuse of these cues and/or a possible lack of knowledge around infant readiness for solids and transitional feeding, an area yet to be explored in the literature. How mothers approached initial transitional feeding may reflect future feeding styles associated with poor food choices and obesity (Nicklaus & Remy, 2013; Vollmer & Mobley, 2013). Feeding to influence growth and behavior overrides infant cues and is consistent with a controlling unresponsive authoritarian approach whereas basing all feeding decisions on infant cues may result in mothers moving to an indulgent feeding style whereby the child has total control. This is in stark contrast to Satter's division of responsibility principle that suggests that parents should provide food, and it is up to the child to decide whether to eat or not (Satter 2004).

Infant happiness was at the forefront of the feeding decisions of many mothers, with happiness and contentment equated to good health and hearty eating. This pursuit of happiness resulted in some mothers disregarding feeding guidelines, introducing solids early and feeding to keep the infant happy while ignoring infant satiety cues. These practices were also evident in the feeding strategies used by some mothers to achieve a heavier infant, with bigger being regarded as synonymous with health. Insufficient growth, as assessed by the mother, resulted in the addition of formula or early solids, including cereal added to bottles (primarily in the US studies and notably in African American and Latino American populations). Underweight concern and inappropriate feeding strategies have been described in other studies of young children (Baughcum, Burklow, Deeks, Powers, & Whitaker, 1998; Gregory, Paxton, & Brozovic, 2010; Sherry et al., 2004).

Overweight was normalized and justified in the family context, with heavier weight status a reflection of parenting success. Poor recognition of child overweight status by parents and preference for “chubbier” children has been well reported in the literature (Baughcum, Chamberlin, Deeks, Powers, & Whitaker, 2000; Doolen, Alpert, & Miller, 2009; Goodell, Pierce, Bravo, & Ferris, 2008). An overall lack of parental concern about obesity and future health in this review is a concern given the early origins of obesity (Birch 2006; World Health Organization 2016). While it was clear that parents were more concerned with the “here and now”, further research to tease out this phenomenon in an effort to support parents to also consider long term health is important. Indeed, identifying the social, cultural, and familial contextualization of infant feeding will provide many answers to the practices observed.

Differentiating between infant‐driven and mother‐driven feeding responses in this review was challenging. While infant cues were used to guide maternal actions, many feeding practices were found to be built on the valued responses of growth, contentment and sleep as described in the review by Dattilo et al. on modifiable risk factors associated with early childhood obesity (Dattilo et al. 2012). It was apparent that sometimes feeding practices were coping strategies for the parents with feeding not always being used to relieve hunger potentially leading to overfeeding. While responsive infant feeding practices are measured by recognition and timely interactions to signs of hunger and fullness, overriding infant cues to influence behavior may lead to the development of childhood obesity and future health problems (Bergmeier, Skouteris, & Hetherington, 2015; Dattilo et al., 2012; DiSantis et al., 2011; Rhee, 2008).

Emotions were also found to play a significant role in the feeding practices documented, with the need for parents to enjoy feeding influencing choices made. In many cases, this is gauged by the quantity of food eaten, with successful parenting measured by satisfying infant needs. Indeed, the importance of good mothering (Marshall, Godfrey, & Renfrew, 2007) was highlighted in many of the papers with feeding behaviors that deviated from medical or cultural expectations justified through maternal coping strategies. This behavior is viewed as risky under the current medicalized lens of infant feeding with mothers left to morally defend their choices (Knaak 2010; Lee 2007, 2008; Murphy 2000). It may also be argued that “professionalisation” of infant feeding has reduced the confidence of mothers around their feeding practices and promoted the move away from the use of non‐expert help (Barclay et al. 2012).

Maternal beliefs about how to respond to infant feeding were prioritized over knowledge, with many mothers choosing inappropriate feeding practices that appeared to settle their child despite knowing these deviate from recommendations. Variable acceptance of these recommendations and belief that exceptions to their use exist, may partially explain these responses. Health risk aversion for some is secondary to ease of feeding (Lee 2007). Inquiry into elevating long‐term health considerations into maternal feeding practices is warranted. Apart from their early safety relevance, it was felt the recommendations fail to address the context in which they are embedded, with intake dependent on parental, social, and cultural constructs and their capacity to adjust to the additional demands of feeding. Insufficient knowledge and skills to translate healthy eating into action, against a back drop of time and money barriers, were also identified.

With infant feeding practices entwined in generational experience, the pressure for parents to conform to family traditions is immense. Confused by inconsistent advice, it is not surprising that many mothers adhered to trusted family customs despite their inconsistencies with infant feeding recommendations. With health professionals also providing conflicting advice, it is a little wonder that mothers are left confused and doing what works best for them and their infant. No matter the etiology of these feeding practices, many mothers found it difficult to measure up to health professional expectations, leaving some to lie about their feeding and in many cases to align with family beliefs. This behavior is consistent with Lee's study of UK mothers' infant feeding experiences with many left struggling with their maternal identity and “opting to go it alone” (Lee 2008).

4.1. Limitations and strengths

This review incorporated the views of many low income mothers representing cultural groups primarily from the US suggesting a limitation to the generalizability of the findings reported. The papers were primarily focused on milk feeding choices and the timing of solids providing limited insights into the navigation of transitional feeding process or the food choices made. Nonetheless, the common themes reported across the included papers would suggest that all mothers face similar challenges in balancing family life and feeding their infants. The use of a peer reviewed methodology for qualitative thematic synthesis assessment and reporting, in addition to the use of a multidisciplinary team of investigators to undertake this synthesis is seen as strength of this review.

5. CONCLUSION

Many new mothers struggle to identify the best approach to transitioning from milk feeds to family foods. With the ultimate goal of doing what is best for their child, mothers were found to use a variety of cues to guide their infant feeding practices. While these prompts were sourced from either their infant or externally from an array of community supports, the ultimate decision sat with the mother, with feeding practices built on the favorable responses of growth, sleep, and happiness.

In this systematic review, familial and cultural influences were the basis of many infant feeding decisions. “Good mothering” as measured through cultural and societal expectations was also clearly demonstrated to have a profound effect on feeding. Given that these contextual factors are so much more prominent than a nutritional focus in feeding practices, it is imperative that practitioners acknowledge the emotional challenges and decision making influences faced by all mothers in this feeding window. Research to further investigate parental measures of infant feeding success to better understand feeding decisions and to strengthen early childhood obesity prevention interventions is recommended.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

MH is funded by the Commonwealth Government of Australia through an Australian Postgraduate Award (APA).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

MH conceived the paper including the scope of the manuscript. MH searched the literature, identified the articles that met the inclusion criteria, led the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. WB verified the literature search and along with MH identified the full‐text articles for analysis. WB and JH contributed to the development of the data analysis framework and interpretation of the analyzed results. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the submitted copy for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Mr Lars Eriksson, librarian from the University of Queensland, for his assistance in developing and verifying the search strategy.

Harrison M, Brodribb W, Hepworth J. A qualitative systematic review of maternal infant feeding practices in transitioning from milk feeds to family foods. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13:e12360 10.1111/mcn.12360

REFERENCES

- Afflerback, S. , Carter, S. K. , Anthony, A. K. , & Grauerholz, L. (2013). Infant‐feeding consumerism in the age of intensive mothering and risk society. Journal of Consumer Culture, 13(3), 387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A. S. , Guthrie, C. A. , Alder, E. M. , Forsyth, S. , Howie, P. W. , & Williams, F. L. (2001). Rattling the plate‐‐reasons and rationales for early weaning. Health Education Research, 16(4), 471–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arden, M. A. (2010). Conflicting influences on UK mothers' decisions to introduce solid foods to their infants. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 6(2), 159–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, L. , Longman, J. , Schmied, V. , Sheehan, A. , Rolfe, M. , Burns, E. , et al. (2012). The professionalising of breast feeding‐‐where are we a decade on? Midwifery, 28(3), 281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughcum, A. E. , Burklow, K. A. , Deeks, C. M. , Powers, S. W. , & Whitaker, R. C. (1998). Maternal feeding practices and childhood obesity: A focus group study of low‐income mothers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 152(10), 1010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughcum, A. E. , Chamberlin, L. A. , Deeks, C. M. , Powers, S. W. , & Whitaker, R. C. (2000). Maternal perceptions of overweight preschool children. Pediatrics, 106(6), 1380–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeier, H. , Skouteris, H. , & Hetherington, M. (2015). Systematic research review of observational approaches used to evaluate mother–child mealtime interactions during preschool years. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 101(1), 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeier, H. , Skouteris, H. , Horwood, S. , Hooley, M. , & Richardson, B. (2014). Associations between child temperament, maternal feeding practices and child body mass index during the preschool years: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Reviews, 15(1), 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch, L. L. (2006). Child feeding practices and the etiology of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring), 14(3), 343–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch, L. L. , & Davison, K. K. (2001). Family environmental factors influencing the developing behavioral controls of food intake and childhood overweight. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 48(4), 893–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch, L. L. , & Ventura, A. K. (2009). Preventing childhood obesity: What works? International Journal of Obesity (2005), 33(Suppl 1), S74–S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramhagen, A. , Axelsson, I. , & Hallström, I. (2006). Mothers' experiences of feeding situations ‐‐ an interview study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(1), 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaidez, V. , Townsend, M. , & Kaiser, L. L. (2011). Toddler‐feeding practices among Mexican American mothers. A qualitative study. Appetite, 56(3), 629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciampa, P. J. , Kumar, D. , Barkin, S. L. , Sanders, L. M. , Yin, H. S. , Perrin, E. M. , et al. (2010). Interventions aimed at decreasing obesity in children younger than 2 years: A systematic review. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164(12), 1098–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, K. S. (2000). Explaining infant feeding style of low‐income black women. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 15(2), 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigie, A. M. , Lake, A. A. , Kelly, S. A. , Adamson, A. J. , & Mathers, J. C. (2011). Tracking of obesity‐related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas, 70(3), 266–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, L. A. , Mallan, K. M. , Nicholson, J. M. , Thorpe, K. , Nambiar, S. , Mauch, C. E. , et al. (2015). An early feeding practices intervention for obesity prevention. Pediatrics, 136(1), e40–e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, L. A. , Wilson, J. L. , Mallan, K. M. , Mihrshahi, S. , Perry, R. , Nicholson, J. M. , et al. (2012). Recruiting and engaging new mothers in nutrition research studies: Lessons from the Australian NOURISH randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dattilo, A. M. , Birch, L. , Krebs, N. F. , Lake, A. , Taveras, E. M. , & Saavedra, J. M. (2012). Need for early interventions in the prevention of pediatric overweight: a review and upcoming directions. Journal of Obesity, 2012, 123023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiSantis, K. I. , Hodges, E. A. , Johnson, S. L. , & Fisher, J. O. (2011). The role of responsive feeding in overweight during infancy and toddlerhood: A systematic review. International Journal of Obesity (2005), 35(4), 480–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolen, J. , Alpert, P. T. , & Miller, S. K. (2009). Parental disconnect between perceived and actual weight status of children: A metasynthesis of the current research. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 21(3), 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EQUATOR network 2015, Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research, viewed September 2015, http://www.equator-network.org/%3e.

- Goodell, S. L. , Pierce, M. B. , Bravo, C. M. , & Ferris, A. M. (2008). Parental perceptions of overweight during early childhood. Qualitative Health Research, 18(11), 1548–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, J. E. , Paxton, S. J. , & Brozovic, A. M. (2010). Pressure to eat and restriction are associated with child eating behaviours and maternal concern about child weight, but not child body mass index, in 2‐ to 4‐year‐old children. Appetite, 54(3), 550–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote, V. , & Theurich, M. (2014). Complementary feeding and obesity risk. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 17(3), 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannes, K. (2011). Chapter 4: Critical appraisal of qualitative research In Noyes J., Booth A., Hannes K., Harden A., Harris J., Lewin S., & Lockwood C. (Eds.), Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 1 (updated August 2011). Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, viewed August 2016, http://cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance%3e. [Google Scholar]

- Heinig, M. J. , Follett, J. R. , Ishii, K. D. , Kavanagh‐Prochaska, K. , Cohen, R. , & Panchula, J. (2006). Barriers to compliance with infant‐feeding recommendations among low‐income women. Journal of Human Lactation, 22(1), 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh, K. D. , & Campbell, K. J. (2010). Interventions to prevent obesity in 0‐5 year olds: An updated systematic review of the literature. Obesity (Silver Spring), 18(Suppl 1), S27–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, B. (2000). Puerto Rican cultural beliefs: Influence on infant feeding practices in western New York. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 11(1), 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, E. A. , Hughes, S. O. , Hopkinson, J. , & Fisher, J. O. (2008). Maternal decisions about the initiation and termination of infant feeding. Appetite, 50(2–3), 333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horodynski, M. , Olson, B. , Arndt, M. J. , Brophy‐Herb, H. , Shirer, K. , & Shemanski, R. (2007). Low‐income mothers’ decisions regarding when and why to introduce solid foods to their infants: influencing factors. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 24(2), 101–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horodynski, M. A. , Brophy‐Herb, H. , Henry, M. , Smith, K. A. , & Weatherspoon, L. (2009). Toddler feeding: Expectations and experiences of low‐income African American mothers. Health Education Journal, 68(1), 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, K. M. , Cross, M. B. , & Hughes, S. O. (2011). A systematic review of responsive feeding and child obesity in high‐income countries. Journal of Nutrition, 141(3), 495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlor, L. , Mackert, M. , Junker, D. , & Tyler, D. (2011). Ensuring children eat a healthy diet: A theory‐driven focus group study to inform communication aimed at parents. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 26(1), 13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, L. , & Karpati, A. (2007). Understanding the sociocultural roots of childhood obesity: Food practices among Latino families of Bushwick, Brooklyn. Social Science and Medicine, 64(11), 2177–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaak, S. J. (2010). Contextualising risk, constructing choice: Breastfeeding and good mothering in risk society. Health, risk & society, 12(4), 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. J. (2007). Infant feeding in risk society. Health, risk & society, 9(3), 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. J. (2008). Living with risk in the age of “intensive motherhood”: Maternal identity and infant feeding. Health, risk & society, 10(5), 467–477. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelace, S. , & Rabiee‐Khan, F. (2013). Food Choices Made by Low‐Income Households when Feeding their Pre‐School Children: A Qualitative Study. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11(4), 870–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, J. L. , Godfrey, M. , & Renfrew, M. J. (2007). Being a ‘good mother’: Managing breastfeeding and merging identities. Social Science and Medicine, 65(10), 2147–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, P. (2003). Weaning: Parents' perceptions and practices. Community Practitioner, 76(1), 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey, E. , Collie, K. , Fraser, G. , Shufflebarger, C. , Lloyd, B. , & Norman Oliver, M. (2006). Using focus group results to inform preschool childhood obesity prevention programming. Ethnicity and Health, 11(3), 265–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, E. (2000). Risk, responsibility and rhetoric in infant feeding. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 29(3), 291–325. [Google Scholar]

- Nicklaus, S. R. , & Remy, E. (2013). Early origins of overesting:Tracking between early food habits and later eating patterns. Current Obesity Reports, 2(2), 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, A. , Michaelsen, K. F. , & Holm, L. (2013). Parental concerns about complementary feeding: Differences according to interviews with mothers with children of 7 and 13 months of age. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 67(11), 1157–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omar, M. A. , Coleman, G. , & Hoerr, S. (2001). Healthy eating for rural low‐income toddlers: Caregivers' perceptions. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 18(2), 93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panic, N. , Leoncini, E. , de Belvis, G. , Ricciardi, W. , & Boccia, S. (2013). Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta‐analyses. PloS One, 8(12), e83138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J. , & Langley‐Evans, S. C. (2013). The types of food introduced during complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: A systematic review. International Journal of Obesity (2005), 37(4), 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J. , Taylor, M. A. , & Langley‐Evans, S. C. (2013). Timing of the introduction of complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: A systematic review. International Journal of Obesity (2005), 37(10), 1295–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redsell, S. A. , Atkinson, P. , Nathan, D. , Siriwardena, A. N. , Swift, J. A. , & Glazebrook, C. (2010). Parents' beliefs about appropriate infant size, growth and feeding behavior: implications for the prevention of childhood obesity. BMC Public Health, 10, 711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redsell, S. A. , Edmonds, B. , Swift, J. A. , Siriwardena, A. N. , Weng, S. , Nathan, D. , et al. (2016). Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions that aim to reduce the risk, either directly or indirectly, of overweight and obesity in infancy and early childhood. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12(1), 24–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, K. (2008). Childhood overweight and the relationship between parent behaviors, parenting style, and family functioning. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 615(1), 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Satter, E. (2004). Children, the feeding relationship, and weight. Maryland Medicine, 5(3), 26–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaglioni, S. , Arrizza, C. , Vecchi, F. , & Tedeschi, S. (2011). Determinants of children's eating behavior. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 94(6 Suppl), 2006S–2011S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, C. , Madrelle, J. , Vereijken, C. M. , Weenen, H. , Nicklaus, S. , & Hetherington, M. M. (2013). Complementary feeding and “donner les bases du gout” (providing the foundation of taste). A qualitative approach to understand weaning practices, attitudes and experiences by French mothers. Appetite, 71, 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry, B. , McDivitt, J. , Birch, L. L. , Cook, F. H. , Sanders, S. , Prish, J. L. , et al. (2004). Attitudes, practices, and concerns about child feeding and child weight status among socioeconomically diverse white, Hispanic, and African‐American mothers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 104(2), 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. S. , Mulder, C. , Twisk, J. W. , van Mechelen, W. , & Chinapaw, M. J. (2008). Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Reviews, 9(5), 474–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synnott, K. , Bogue, J. , Edwards, C. A. , Scott, J. A. , Higgins, S. , Norin, E. , et al. (2007). Parental perceptions of feeding practices in five European countries: An exploratory study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 61(8), 946–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cochrane Collaboration (2015). Reporting guidelines, The Cochrane Collaboration, viewed. September, 2015, .http://community.cochrane.org/about-us/evidence-based-health-care/webliography/books/reporting%3e [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. , & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason Reuters (2013). Endnote, X7. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Flemming, K. , McInnes, E. , Oliver, S. , & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12, 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer, R. L. , & Mobley, A. R. (2013). Parenting styles, feeding styles, and their influence on child obesogenic behaviors and body weight. A review. Appetite, 71, 232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller, J. , Bower, K. M. , Spence, M. , & Kavanagh, K. F. (2013). Using grounded theory methodology to conceptualize the mother‐infant communication dynamic: Potential application to compliance with infant feeding recommendations. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11(4), 749–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warin, M. , Turner, K. , Moore, V. , & Davies, M. (2008). Bodies, mothers and identities: rethinking obesity and the BMI. Sociology of Health and Illness, 30(1), 97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters, E. , de Silva‐Sanigorski, A. , Hall, B. J. , Brown, T. , Campbell, K. J. , Gao, Y. , et al. (2011). Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, CD001871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijndaele, K. , Lakshman, R. , Landsbaugh, J. R. , Ong, K. K. , & Ogilvie, D. (2009). Determinants of early weaning and use of unmodified cow's milk in infants: a systematic review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(12), 2017–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2016). Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, viewed 3 August 2016, http://www.who.int/end-childhood-obesity/publications/echo-report/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Zehle, K. , Wen, L. M. , Orr, N. , & Rissel, C. (2007). “It's not an issue at the moment”: A qualitative study of mothers about childhood obesity. MCN: American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 32(1), 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]