Abstract

Young children are at risk of iron deficiency and subsequent anaemia, resulting in long‐term consequences for cognitive, motor and behavioural development. This study aimed to describe the iron intakes, status and determinants of status in 2‐year‐old children. Data were collected prospectively in the mother–child Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study from 15 weeks' gestation throughout early childhood. At the 24‐month assessment, serum ferritin, haemoglobin and mean corpuscular volume were measured, and food/nutrient intake data were collected using a 2‐day weighed food diary. Iron status was assessed in 729 children (median [IQR] age: 2.1 [2.1, 2.2] years) and 468 completed a food diary. From the food diary, mean (SD) iron intakes were 6.8 (2.6) mg/day and 30% had intakes < UK Estimated Average Requirement (5.3 mg/day). Using WHO definitions, iron deficiency was observed in 4.6% (n = 31) and iron deficiency anaemia in five children (1.0%). Following an iron series workup, five more children were diagnosed with iron deficiency anaemia. Twenty‐one per cent had ferritin concentrations <15 µg/L. Inadequate iron intakes (OR [95% CI]: 1.94 [1.09, 3.48]) and unmodified cows' milk intakes ≥ 400 mL/day (1.95 [1.07, 3.56]) increased the risk of low iron status. Iron‐fortified formula consumption was associated with decreased risk (0.21 [0.11, 0.41] P < 0.05). In this, the largest study in toddlers in Europe, a lower prevalence of low iron status was observed than in previous reports. Compliance with dietary recommendations to limit cows' milk intakes in young children and consumption of iron‐fortified products appears to have contributed to improved iron status at two years.

Keywords: birth cohort, iron deficiency, anaemia, iron intakes, food fortification, cows' milk consumption

Introduction

Anaemia is estimated to affect 1.62 billion people worldwide, with roughly 50% of cases attributed to iron deficiency (World Health Organisation 2008). Infants and young children (aged 6–24 months) are at particular risk of iron deficiency and subsequent anaemia due to the increased requirements associated with this period of rapid growth. Term infants are born with iron reserves that can last for the first 4–6 months of life; however, after this the infant relies on dietary intakes. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in early childhood can have long‐term consequences for cognitive, motor and behavioural development (Lozoff et al. 2006; Georgieff 2011).

Risk factors for iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia include low birth weight, low socioeconomic status, presence of infection/illness and dietary factors (Burke et al. 2014). Dietary factors include adequate dietary iron intakes, the form of iron ingested (haem/non‐haem) and the presence of inhibitors and enhancers of iron absorption in meals. In particular, low intakes of iron‐rich foods, such as meat and the early introduction/high intakes of unmodified cows' milk can be detrimental to iron status (Thane et al. 2000; Gunnarsson et al. 2007).

There is wide variability in diagnostic criteria for both iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in young children (Domellof et al. 2002a), but it is estimated that approximately 25% of preschool‐age children have iron deficiency anaemia worldwide (Mclean et al. 2009). However, there is significant variability in prevalence rates. In developing countries, rates are very high; in rural India, 61.9% of 12–23 month olds had iron deficiency (serum ferritin < 12 µg/L) and 73% of these were anaemic (haemoglobin < 110 g/L) (Pasricha et al. 2010). The prevalence of iron deficiency ranged from 3 to 48% in young European children, while iron deficiency anaemia rates were typically below 5%, although increased rates of up to 40% have been reported in Eastern Europe (Eussen et al. 2015). Of British children aged 1.5–3 years 35.1% had iron deficiency and 5.2% had iron deficiency anaemia (Bates et al. 2014). Comparatively better iron status in the USA and iron deficiency of 8–9% and iron deficiency anaemia of 3% (Brotanek et al. 2007) could be a consequence of public health efforts to tackle poor iron status through food fortification and supplementation policies, targeted at vulnerable minority groups in particular.

The iron status of young children in Ireland was last explored in the late 1990s; 50% of 2‐year‐old had serum ferritin concentrations < 10 µg/L (Freeman et al. 1998). Since then, dietary recommendations have stipulated a 12‐month threshold prior to the introduction of unmodified cows' milk as a main drink (Food Safety Authority of Ireland 2011). Therefore, the aim of the current study was to determine the iron intakes (including dietary sources) and status of 2‐year‐old children from a large prospective birth cohort study in Ireland and to identify the important determinants of iron status.

Key messages.

Standardisation of the diagnostic criteria for iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in infants and young children is required.

Compliance with national recommendations to limit cows' milk intakes in young children appears to have made a major contribution to improved iron status.

Voluntary fortification of foods popular among young children with iron also appears to have contributed to improved iron status.

Materials and methods

Participants

The Cork BASELINE (Babies after SCOPE: Evaluating the Longitudinal Impact using Neurological and Nutritional Endpoints) Birth Cohort Study is a prospective birth cohort study, established in 2008 to investigate links between early nutrition and perinatal outcomes and physical and mental growth and development during childhood. The birth cohort is a follow‐on from the SCOPE (Screening for Pregnancy Endpoints) Ireland pregnancy study, an international multicentre study aimed at investigating early indicators of pregnancy complications. Detailed demographic, socioeconomic, anthropometric and clinical data and biological samples were collected for all SCOPE participants (North et al. 2011).

Written informed consent to the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study was provided by parents; 1537 recruited from the SCOPE study and an additional 600 recruited at birth through the postnatal wards of the Cork University Maternity Hospital (recruitment concluded November 2011). Participants were followed prospectively, beginning at day 2 and at 2, 6, 12 and 24 months, with assessments at five years on‐going. Detailed information on early life environment, diet, lifestyle, health, growth and development was gathered by interviewer‐led questionnaires and clinical assessments and entered at the time of appointment into an internet‐based, secure database developed by Medical Science Online (MedSciNet, Sweden), compliant with the US Food and Drug Administration and the Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act. A detailed methodology of the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study has been provided by O'Donovan et al. (2015a).

Research objectives and measurements in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study were conducted according to the guidelines laid down by the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was granted by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork teaching hospitals, ref ECM 5(9) 01/07/2008 and is registered at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials Registry (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov), ID: NCT01498965. The SCOPE study is registered at the Australian, New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (http://www.anzctr.org.au), ID: ACTRN12607000551493.

Dietary assessment

At the 24‐month assessment, food and nutrient intake data were collected in the form of a 2‐day weighed food diary, carried out over non‐consecutive days. Parents were instructed to record detailed information about the amount and types of all foods, beverages and supplements consumed during the diary period. Information on cooking methods, brand names of products, details of recipes and any leftovers were also recorded.

Consumption data were converted to nutrient intake data using the nutritional analysis software Weighed Intake Software Package WISP© (Tinuviel Software, Anglesey, UK), using food composition data from McCance and Widdowson's The Composition of Foods sixth (Food Standards Agency 2002) and fifth (Holland et al. 1995) editions. The food database was updated to incorporate composite dish recipes, nutritional supplements, fortified foods, new food products and food items specific to infants and young children. Food composition data from the Irish Food Composition Database (Black et al. 2011) and modifications made during the National Preschool Nutrition Survey (NPNS) (Irish Universities Nutrition Alliance 2012) were also incorporated. Each food code was manually checked to ensure that it accurately represented the amount of iron in products.

Energy under‐reporting was identified using minimum energy intake cut‐off points, calculated as multiples of Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR), with individuals below a certain cut‐off point classified as under‐reporters. BMR was calculated for all participants using equations developed by Schofield et al. (1985). The appropriate age‐specific cut‐off of 1.28 (based on principles of fundamental energy physiology) for children aged 1–5 years as suggested by Torun et al. (1996) was used. Data were analysed both including and excluding under‐reporters.

All food and drinks consumed by participants were assigned into 73 food groups, which were then aggregated into subgroups depending on the analysis. Mean daily intakes of iron for participants were calculated by averaging their intake over the diary recording period. The percentage contributions of food groups to iron intake were calculated using the population proportion method, by summing the amount of iron from a particular food group for all participants and dividing this by the sum of iron from all foods for all participants (Krebs‐Smith et al. 1989). Mean daily intakes were also calculated using the mean proportion method, taking an arithmetic mean of all individual mean intakes. For the analysis, participants were subdivided into consumer groups. Iron‐fortified products were identified by the presence of iron in the manufactured item that would have much less or no iron in it naturally, including infant formula and breakfast cereals. Participants that consumed at least one fortified product over the diary period were considered an iron‐fortified product consumer, while those that did not were non‐consumers. Participants that consumed any infant formula or growing‐up milk (GUM) products during the diary period were classified as formula consumers.

GUM products are described as formula/milk tailored to meet the nutritional requirements of 1–3 year old children, with two 150 mL beakers per day of the product recommended by manufacturers. In this study, GUM products are referred to as iron‐fortified formula to account for differences in terminology used for these products globally.

Additional data collected

At earlier study assessments at 2, 6 and 12 months, data on feeding and nutrition were collected, including early feeding methods, duration of breastfeeding (if applicable), formula use and timing of complementary feeding, which was used in the current analysis.

At the 24‐month assessment, all parents were asked if their child currently consumed any GUM products or if they were currently or had in the previous four weeks taken any iron supplements. These questions were in addition to information provided by the food diary if completed.

Biological samples and analytical methods

Venous blood was collected from all BASELINE study participants at the 24‐month assessment, with parental consent. After blood collection, samples were immediately stored at 5 °C and were then processed to serum for storage at −80 °C.

Whole blood collected at the 24‐month assessment was sent immediately to the Haematology Laboratory of Cork University Hospital for determination of haemoglobin concentrations and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) on the Sysmex XE 2100 Automated Hematology System (Sysmex America Inc., IL, USA). Ferritin and high sensitivity C‐reactive protein (CRP) were analysed in the laboratory of the Cork Centre for Vitamin D and Nutrition Research, University College Cork, by immunoturbidimetric assay on the RX Monaco Clinical Chemistry Analyser (Randox Laboratories Ltd., Co. Antrim, UK). As serum ferritin is an acute phase reactant, children with potential infections as indicated by an elevated CRP (CRP > 5 mg/L) were subsequently excluded from all analyses. An iron series workup (serum iron [abnormal < 10 µmol/L], serum transferrin [acceptable range: 1.8–3.2 g/L], transferrin saturation [abnormal < 10%]) was performed by the Biochemistry Laboratory of Cork University Hospital on selected participants' samples using the AU5800 Chemistry Analyser (Beckman Coulter Inc., CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS® for Windows™ version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data are presented using descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations (SD), medians, interquartile ranges (IQR) and percentages, where appropriate. Comparisons between categorical variables were made using Chi square (χ2) or Fisher's exact tests, while independent t‐tests or non‐parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U) were employed for continuous variables, depending on their distribution.

Due to the low numbers of participants with iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia, determinants of each iron status indicator (ferritin, MCV and haemoglobin) were explored individually. Serum ferritin concentrations were divided into quartiles. Logistic regression analysis was performed to model the associations of maternal and child characteristics (including gender, gestational age, mode of delivery, early feeding methods, dietary factors at two years and maternal age, relationship status, income, profession, education level, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), iron status and supplement use) with the risk of being in the lowest quartile of serum ferritin concentrations (≤15.5 µg/L; other three quartiles used as reference). From the univariate analysis, variables identified as significant at the 10% (P < 0.1) level were included in the adjusted multivariate analysis, with associations expressed as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Numbers of participants in models varied depending on data available for each participant, and method was repeated with haemoglobin concentrations < 110 g/L and MCV < 74 fL as the dependent variables in models.

Results

Participants

Of the 2137 infants initially recruited to the study, 1537 attended the 24‐month assessment. Of those, 729 (47%) gave blood and 468 (30%) completed a 2‐day weighed food diary. A subgroup of 286 children had both a food diary and blood collected at two years of age. There were no significant differences in socio‐demographic characteristics between those with a completed food diary and blood sample and those with only a blood sample and the participants with a completed food diary were representative of the entire 24‐month cohort. Characteristics of the study participants that completed a food diary and/or gave blood for iron status analysis are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Maternal and child characteristics of participants of the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study with a completed food diary and/or blood sample at two years (n = 911)

| Median [IQR] or % | |

|---|---|

| Maternal | |

| Age at delivery (years) | 32.0 [29.0, 34.0] |

| Caucasian | 99 |

| Born in Ireland | 85 |

| Attended third level education | 86 |

| Relationship status, single | 5 |

| Iron supplement user (in pregnancy) | 73 |

| Child | |

| Gender, male | 53 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.5 [3.2, 3.8] |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 40.3 [39.3, 41.0] |

| Infant feeding | |

| Any breastfeeding (at hospital discharge) | 72 |

| Age first given solids (weeks) | 20.0 [17.0, 22.0] |

| 24‐month assessment | |

| Age (years) | 2.1 [2.1, 2.2] |

| Weight (kg) | 12.9 [12.0, 13.9] |

| Height (m) | 0.88 [0.86, 0.90] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.7 [15.9, 17.6] |

| Iron supplement user* | 2 |

| Iron‐fortified formula consumer* | 19 |

IQR: interquartile range; BMI: body mass index.

Prevalence data collected from participant questionnaires at 24‐month assessment.

Dietary intakes

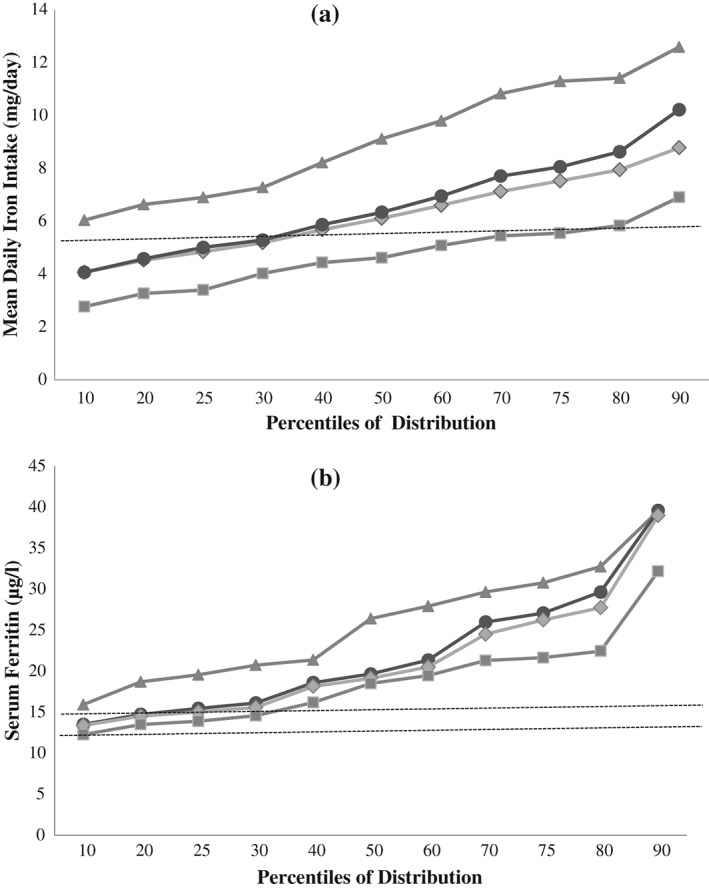

The mean percentage and actual (mg/day) contribution of food groups to iron intakes in those with a completed food diary are presented in Table 2. The mean (SD) daily iron intake of the total population was 6.8 (2.6) mg and 30% had intakes below the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR, UK EAR of 5.3 mg/day) (Department of Health 1991; Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition 2010). Twenty‐one per cent consumed any formula products during the two‐day diary period, with a mean (SD) daily iron intake of 9.3 (2.8) mg. Iron‐fortified formula contributed to 40% (3.7 mg) of iron intakes in consumers. Ninety per cent of children consumed iron‐fortified products during the diary period. Consumers had mean daily iron intakes 2.0 mg higher than non‐consumers, while only 26% of consumers had inadequate intakes compared to 65% of non‐consumers (P < 0.001). Intakes at the 97.5th centile in formula consumers and iron‐fortified product consumers were 17.1 and 12.7 mg/day, respectively. The prevalence of iron supplement use was low with seven participants (1%) using them during the diary period. Stratification of participants into food consumer groups depicted in Fig. 1(a) illustrated a clear difference in mean daily iron intakes between base diet (no iron‐fortified products) consumers and formula consumers especially.

Table 2.

Mean percentage and actual (mg/day) contribution of food groups to total iron intakes at two years (n = 468)

| Food groups | Total population | Iron‐fortified product consumers | Iron‐fortified product non‐consumers | Formula consumers | Formula non‐consumers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 468 | n = 422 | n = 46 | n = 96 | n = 372 | ||||||

| % | mg/day | % | mg/day | % | mg/day | % | mg/day | % | mg/day | |

| Breakfast cereals | 31 | 2.10 | 32 | 2.25 | 17 | 0.81 | 17 | 1.63 | 36 | 2.23 |

| Breads and grains | 14 | 0.93 | 13 | 0.94 | 18 | 0.89 | 10 | 0.97 | 15 | 0.92 |

| Iron‐fortified formula | 11 | 0.76 | 12 | 0.85 | — | — | 40 | 3.72 | — | — |

| Meat and meat products | 10 | 0.68 | 9 | 0.66 | 16 | 0.79 | 6 | 0.57 | 11 | 0.70 |

| Biscuits and cakes | 7 | 0.47 | 7 | 0.48 | 6 | 0.33 | 6 | 0.58 | 7 | 0.44 |

| Vegetables | 5 | 0.37 | 5 | 0.37 | 9 | 0.43 | 4 | 0.36 | 6 | 0.38 |

| Fruit | 6 | 0.40 | 6 | 0.40 | 7 | 0.35 | 4 | 0.38 | 6 | 0.40 |

| Milk, yoghurts, cheeses | 4 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.25 | 5 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.23 | 4 | 0.26 |

| Pulse incl. baked beans | 4 | 0.30 | 4 | 0.29 | 8 | 0.40 | 3 | 0.22 | 5 | 0.32 |

| Nutritional supplements | 1 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.04 | 5 | 0.26 | 1 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.06 |

| Other* | 7 | 0.48 | 7 | 0.47 | 9 | 0.51 | 7 | 0.60 | 9 | 0.48 |

| Mean (SD) Daily Intake (mg/day)† | 6.8 (2.6) | 7.0 (2.5) | 5.0 (2.2) | 9.3 (2.8) | 6.2 (2.1) | |||||

| % Below the EAR ‡ | 30 | 26 | 65 | 4 | 36 | |||||

SD: standard deviation; EAR: estimated average requirement.

Other includes eggs and egg dishes, fish and fish dishes, beverages, confectionary, savoury snacks, soups and sauces.

Mean (SD) daily intake calculated using the population proportion (Krebs‐Smith et al. 1989) and mean proportion methods. Results were same for both methods.

Figure 1.

(a) Distributions of mean daily iron intakes (mg/day) among food group consumers. Total population (●, n = 461), iron‐fortified breakfast cereal only (excluding all formula) consumers (♦, n = 322), formula consumers (▲, n = 95) and base diet (excluding all iron‐fortified products) consumers (■, n = 44). Iron supplement users (n = 7) excluded. Dashed line indicates UK EAR (5.3 mg/day) (b) Distributions of serum ferritin concentrations (μg/L) among food group consumers. Total population (●, n = 257), iron‐fortified breakfast cereal only (excluding all formula) consumers (♦, n = 173), formula consumers (▲, n = 51) and base diet (excluding all iron‐fortified products) consumers (■, n = 33). Iron supplement users (n = 6) excluded. Serum ferritin cut‐offs of 12 and 15 μg/L are indicated on the chart by the dashed lines.

The main food groups contributing to iron intakes were breakfast cereals (31%), breads and grains (14%), iron‐fortified formula (11%) and meat and meat products/dishes (10%). Iron intakes from the base diet ranged from 0.3 to 0.7 mg/day. Ninety‐three per cent of total iron intakes were attributed to non‐haem iron sources and iron intakes at the 97.5th centile in the total population were 12.5 mg/day. The median [IQR] daily intakes of meat and fish (including from composite dishes) were 39.8 [22.9, 61.3] and 20.7 [11.6, 29.8] g, respectively. Of the 468 children with completed food diaries, 36% (n = 167) were classified as energy under‐reporters. With energy under‐reporters excluded, mean (SD) daily iron intakes increased to 7.5 (2.7) mg, although 19% still had intakes below the EAR and in under‐reporters (n = 167) alone, mean (SD) intakes were 5.7 (2.7) mg/day and 47% had intakes below the EAR.

There were no significant differences in socio‐demographic, anthropometric characteristics or macronutrient intakes between iron‐fortified product consumers and non‐consumers. Iron intakes from non‐fortified foods such as meat, breads and grains were also similar between consumers and non‐consumers (see Table 2). Formula consumers had a median [IQR] intake of iron‐fortified formula of 233 [150, 356] mL/day. There were no significant differences in socio‐demographic or anthropometric characteristics at two years between formula consumers and non‐consumers. Formula consumers had slightly higher daily intakes of energy (1055 [926, 1187] vs. 995 [867, 1144] kcal, P = 0.023) consistent with a higher carbohydrate intake (144.6 [119.1, 161.4] vs. 128.6 [106.2, 148.9] g, P < 0.001). Protein intakes were lower (37.7 [32.0, 45.8] vs. 40.6 [33.4, 47.5] g, P = 0.033) than non‐consumers and intakes of fat were the same between the groups. Intakes of foods and overall food groups were also similar, except for a higher intake of unmodified cows' milk in non‐consumers of formula (125.0 [68.4, 212.6] vs. 303.0 [175.4, 485.3] mL/day, P < 0.001).

Iron status

The distributions of haemoglobin (g/L), serum ferritin (µg/L) and MCV (fL) are presented in Table 3. Haemoglobin and MCV were measured in 606 children with mean concentrations of 120.5 g/L and 76.0 fL, respectively; 4.5% (n = 27) had haemoglobin concentrations < 110 g/L. Serum ferritin and high sensitivity CRP were measured in 706 children, however 37 children were excluded from the analysis (due to infection, CRP > 5 mg/L), leaving 669 children with valid serum ferritin measurements. In total, 555 children had both haemoglobin and a valid serum ferritin measurement. Females had significantly higher median [IQR] MCV (77.0 [75.0, 78.9] vs. 75.6 [73.4, 77.8] fL, P < 0.05) than males, with no differences in serum ferritin or haemoglobin concentrations.

Table 3.

Distribution of haematological indices in 2‐year‐olds from the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study

| n | Mean | SD | Median | 10th centile | 25th centile | 75th centile | 90th centile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 606 | 120.5 | 7.1 | 120.0 | 112.0 | 116.0 | 125.0 | 129.0 |

| Serum ferritin (µg/L) | 669 | 24.6 | 16.7 | 19.8 | 13.4 | 15.5 | 27.3 | 39.4 |

| MCV (fL) | 606 | 76.0 | 3.8 | 76.2 | 72.1 | 74.1 | 78.3 | 79.8 |

SD: standard deviation; MCV: mean corpuscular volume.

The prevalence of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia, using multiple cut‐off definitions, is presented in Table 4. Using WHO definitions, iron deficiency (serum ferritin < 12 µg/L) was observed in 4.6% (n = 31) of children, while iron deficiency anaemia (iron deficiency + haemoglobin < 110 g/L) was present in five children (1.0%). A further nine children presented with microcytic anaemia (indicated by MCV < 74 fL + haemoglobin < 110 g/L), but had serum ferritin concentrations > 12 µg/L. Following an iron series workup on these participants' serum samples, five were diagnosed with iron deficiency anaemia due to abnormal values on > 1 of the haematological indices measured. Therefore, 10 (2%) children in total had iron deficiency anaemia.

Table 4.

Prevalence of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in 2‐year‐olds from the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study, according to international definitions

| Definition | % (n)* | Studies (country) using definition |

|---|---|---|

| Iron deficiency | ||

| SF <10 µg/L | 1.8 (12) | NHANES (USA), NDNS (UK), Zhou et al. 2012 (Australia) |

| SF <12 µg/L | 4.6 (31) | World Health Organisation/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004, Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition 2010 (UK) |

| SF <15 µg/L | 20.8 (139) | Hay et al. 2004 (Norway), Capozzi et al. 2010 (Italy) |

| SF <12 µg/L + MCV <74 fL | 2.6 (15) | Michaelsen et al. 1995 (Denmark), Gunnarsson et al. 2004 (Iceland) |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | ||

| Hb <110 g/L + SF <10 µg/L | 0.2 (1) | NHANES (USA), NDNS (UK), |

| Hb <110 g/L + SF <12 µg/L | 1.0 (5) | World Health Organisation/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004, Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition 2010 (UK) |

| Hb <110 g/L + SF <15 µg/L | 1.3 (7) | Hay et al. 2004 (Norway) |

| Hb <105 g/L + SF <10 µg/L | 0.2 (1) | Zhou et al. 2012 (Australia) |

| Hb <105 g/L + SF <12 µg/L + MCV <74 fL | 0.4 (2) | Michaelsen et al. 1995 (Denmark), Gunnarsson et al. 2004 (Iceland) |

SF: serum ferritin; MCV: mean corpuscular volume; Hb: haemoglobin; NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NDNS: National Diet and Nutrition Survey; SACN: Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition.

Prevalence (% and n) in the current study, according to each definition.

There was a small but significant association between mean daily iron intakes and serum ferritin concentrations (Spearman r = 0.183, P = 0.003) and MCV (r = 0.172, P = 0.005). There was no significant association between mean daily iron intakes and haemoglobin concentrations. A clear differentiation in serum ferritin concentrations among different food group consumers is illustrated in Fig. 1(b). Iron‐fortified product consumers had significantly higher serum ferritin concentrations compared to non‐consumers (20.1 [15.7, 27.6] vs. 18.5 [13.6, 21.6] µg/L, P = 0.027). Formula consumers had higher ferritin concentrations (25.5 [19.6, 33.1] vs. 18.9 [15.1, 26.0] µg/L, P < 0.001) and MCV (77.0 [74.7, 78.7] vs. 76.0 [73.9, 78.2] fL, P = 0.012) than non‐consumers.

Cows' milk consumption

From the food diary, unmodified cows' milk (liquid milk only) intakes were stratified at < 400 mL/day and ≥ 400 mL/day. The cut‐off of 400 mL/day (two beakers of 150 mL each plus ~100 mL serving with breakfast cereal) was chosen based on a preliminary analysis of the current data to identify a threshold that may increase the risk of low iron status as well as the outcomes of previous research (Thane et al. 2000; Uijterschout et al. 2014) indicating relatively high intakes in this age group. During the recording period, 91% (n = 424) of children consumed cows' milk with a median [IQR] daily intake of 260 [114, 452] mL. Among consumers, 31% (n = 130) drank ≥ 400 mL/day, with a median [IQR] intake of 528 [468, 604] mL/day. Children that consumed < 400 mL/day had a median [IQR] intake of 190 [105, 272] mL/day (P < 0.001). Consumers of ≥ 400 mL/day of cows' milk had significantly lower mean daily iron intakes (6.2 vs. 6.9 mg/day, P = 0.016), median [IQR] serum ferritin concentrations (18.3 [13.9, 21.8] vs. 20.5 [16.1, 27.6] µg/L) and MCV (75.3 [72.5, 77.6] vs. 76.5 [74.3, 78.5] fL) than those that consumed < 400 mL/day (all P < 0.01).

Determinants of status

Following adjustment for gender and birth weight, mean daily iron intakes were a significant determinant of serum ferritin concentrations at two years; participants with intakes < EAR had an increased risk of low ferritin concentrations (OR [95% CI]: 1.94 [1.09, 3.48], P = 0.025). Current consumption of iron‐fortified formula was protective against low serum ferritin concentrations at two years (0.21 [0.11, 0.41], P < 0.001), while the consumption of cows' milk at volumes ≥ 400 mL/day was associated with an increased risk of low serum ferritin concentrations, after adjustment for daily iron intakes (1.95 [1.07, 3.56], P = 0.03).

In a separate regression, males were three times more likely to present with a MCV < 74 fL (3.05 [2.01, 4.63], P < 0.001). Iron intakes < EAR were associated with an increased risk of a MCV < 74 fL (3.03 [1.62, 5.65], P < 0.001) and iron‐fortified formula consumption was associated with a reduced risk of a low MCV (0.43 [0.23, 0.79], P = 0.007, adjusted for gender and birth weight). After adjustment for gender and birth weight, cow's milk intakes ≥ 400 mL/day were associated with an increased risk of a low MCV (2.01 [1.09, 3.70], P = 0.025), although this was no longer significant after adjustment for daily iron intakes (1.77 [0.95, 3.32], P = 0.073). No dietary factors were significant determinants of haemoglobin concentrations < 110 g/L at two years. There were no associations between early feeding methods or any other dietary factors at two years including meat/fish consumption, with any of the iron status indicators assessed in this study. All results remained the same both including and excluding energy under‐reporters (from the food diary) in the analysis.

Discussion

This study, the largest study in toddlers in Europe to date, has described the iron intakes and status of 2‐year‐old children in Ireland.

Using WHO definitions, 5% of children had iron deficiency and 1% had iron deficiency anaemia; these rates are lower than contemporary data reported in other European countries (Eussen et al. 2015) and in the USA (Brotanek et al. 2007). However, variable diagnostic criteria for infants and young children make it difficult to draw accurate comparisons (Domellof et al. 2002a). Some of the variability may also be explained by differences in the study populations assessed (in demographics and age) and in the analytical methods used to assess haematological indices, especially in the case of immunoassays used to measure ferritin concentrations (World Health Organisation/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004).

Despite a low prevalence of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia using WHO definitions, 21% of participants had serum ferritin concentrations < 15 µg/L, a cut‐off used by some (Hay et al. 2004; Capozzi et al. 2010) to indicate low iron stores and risk of deficiency. In the clinical setting, serum ferritin cut‐offs of 17–18 µg/L are used, along with a combination of haematological indices including haemoglobin, MCV, serum iron and transferrin saturation. This approach was utilised in the current study for nine children that presented with microcytic anaemia, with serum ferritin concentrations > 12 µg/L; following further investigations, an additional five children were diagnosed with iron deficiency anaemia. Therefore, using both standard definitions and more detailed investigations, ten children in the current study had iron deficiency anaemia. These findings highlight the need for standardisation of the diagnostic criteria in young children, with a need to assess iron status using multiple haematological indices to ensure no ‘at risk’ children are inadvertently undiagnosed.

The prevalence of iron deficiency/depleted stores in the current study is in particular contrast to the last study in Ireland (Freeman et al. 1998), where 50% of two year olds had serum ferritin < 10 µg/L, compared to 2% in the present study. Rates of iron deficiency anaemia were also reported as higher, at 9.2%. This diversity can be explained in part by differing sample sizes and socio‐demographic profiles, with a much larger, more educated sample included in the current study. However, changes in cows' milk consumption patterns may be another explanation.

The cows' milk consumption patterns of young children in Ireland have changed significantly in accordance with national recommendations to wait until a child is one year before cows' milk is given as a main drink (Food Safety Authority of Ireland 2011). Intakes of unmodified cows' milk are now lower; evident as mean intakes of cows' milk in 1‐year‐old from the NPNS were 302 mL/day (Irish Universities Nutrition Alliance 2012) in comparison to 524 mL/day in 1‐year‐old in the Freeman study (Freeman et al. 1998). Also important is the early introduction of cows' milk as a drink (at age two months) in the Freeman study, in contrast to the current study where no child was given cows' milk as a drink before six months. Fifteen per cent of participants in the BASELINE cohort consumed cows' milk as their main drink after their first birthday (O'Donovan et al. 2015b), while 18% of 9‐month‐old in the Euro‐Growth study of the late 1990s (Freeman et al. 2000) were already habitual cows' milk consumers. In the UK, cows' milk was consumed as a main beverage in 79% of 12–18 month olds, in line with UK recommendations to move directly to cows' milk at one year (Lennox et al. 2011).

Similarly to other studies (Thane et al. 2000; Gunnarsson et al. 2004), high intakes of cows' milk were associated with lower serum ferritin concentrations at two years. The exact mechanisms behind the effect of cows' milk on iron status are still somewhat unclear; however possible explanations are its low iron content (~0.5 mg/L), the presence of components in it that inhibit iron absorption or it may cause occult intestinal blood loss (Ziegler 2011). It has been suggested that high intakes of cows' milk may displace iron‐rich solid food sources from the diet (Thane et al. 2000); however, our data do not support this suggestion as the negative influence of high cows' milk intakes remained significant after adjustment for mean daily iron intakes. Due to its influence on iron status, the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition recently advised that intakes of cows' milk in young children should not exceed 500 mL/day (Domellof et al. 2014). However, our findings, in line with findings in the UK (Thane et al. 2000) and Netherlands (Uijterschout et al. 2014) suggest that intakes in young children should not exceed 400 mL/day. It may be timely to re‐examine dietary recommendations in the second year of life.

Dietary iron intakes, in particular inadequate intakes, were a significant determinant of iron status in the current study. No association between dietary iron intakes and status was observed in British and Icelandic children previously (Thane et al. 2000; Gunnarsson et al. 2004). However, a Swedish study displayed age‐dependent associations; serum ferritin concentrations were associated with iron intakes at 18 months of age but not at 12 months, while haemoglobin was associated with iron intakes before 12 months but not after (Lind et al. 2004). These findings suggest that before 12 months of age, dietary iron is directed towards erythropoiesis and after 12 months, it is directed towards iron storage. This dynamic regulation may also provide an explanation for the lack of dietary determinants of haemoglobin concentrations at two years in this study.

Iron‐fortified product consumption had a positive impact on iron status in this study, with iron‐fortified formula consumption an independent determinant of serum ferritin and MCV. Follow‐on formula and iron‐fortified infant cereals have previously been identified as significant determinants of iron status in infancy (Krebs et al. 2013; Thorisdottir et al. 2013). Our study is one of the first to report on the positive impact of iron‐fortified formula specifically in toddlers. Most iron‐fortified formula, targeted at 1–3 year olds, are fortified at a level of 1.2 mg iron/100 mL feed, significantly higher than the iron content of unmodified cows' milk (~0.5 mg/L). The European Food Safety Authority have described such formula as one method of increasing intakes of certain micronutrients but concluded that there was ‘no unique role’ for them in the diet of young children in Europe (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies 2013). Among consumers, formula contributed to increased iron intakes and reduced inadequate intakes, similar to previous observations (Ghisolfi et al. 2013; Walton & Flynn 2013). While energy intakes were higher (~60 kcal/day, attributable probably to the increased carbohydrate contribution of ~16 g/day from the formula) in consumers, we did not observe major differences in dietary intakes or any differences in growth patterns of participants in the current study. As iron‐fortified products were the main dietary sources of iron in our study, the positive impact of these products on iron status points to a potentially important role of fortified products in the diets of young children. Further investigations are required to establish whether improving iron status in the second year of life (over and above prevention of iron deficiency) is linked to favourable growth and development outcomes in early and middle childhood.

Similar to a study in Norwegian children (Hay et al. 2004), males had significantly lower MCV compared to females. These gender differences have been observed in infants previously (Domellof et al. 2002b; Thorsdottir et al. 2003), although other studies have observed no differences in early childhood (Sherriff et al. 1999; Gunnarsson et al. 2004). Explanations for these differences are limited, although suggestions include genetic or hormonal factors, altered growth rates, smaller iron stores at birth in males or even increased intestinal losses in males (Domellof et al. 2002b).

Mean daily iron intakes in the current study were similar to intakes observed in other European national surveys (Ocké et al. 2008; Kyttala et al. 2010; Bates et al. 2014), however slightly lower than those reported by the NPNS of Ireland (6.8 vs. 7.6 mg/day) (Irish Universities Nutrition Alliance 2012). The differing age profiles of these two studies may contribute to this variation, as all children in the current study were aged 23–25 months while the age of those in the NPNS ranged from 24 to 35 months. Only 7% of intakes were attributed to haem iron sources; intakes from meat/meat products were low, a possible explanation as to the lack of association observed between meat consumption and iron status in this study. This diet of predominately non‐haem iron sources appears to be typical of young children in other countries also (Fox et al. 2006; Domellof et al. 2014).

The main strengths of the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study are its prospective, longitudinal design, with its multidisciplinary approach to research. The use of validated, detailed assessments and standard operating procedures are other strengths. Dietary data were collected prospectively, although all forms of self‐reported dietary assessment are subject to error (Livingstone et al. 2004). The generalizability of our results to the rest of Ireland may be somewhat limited, due to the region‐based recruitment and high proportion of educated women in the study, although other socio‐demographic characteristics of the cohort compare well with national reports (O'Donovan et al. 2015a).

We have presented the prevalence of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in young children in Ireland, using a variety of definitions. Compliance with a clear, simple national recommendation to limit cows' milk intakes in young children appears to have made a major contribution to the improved iron status observed in this study. Voluntary fortification of foods popular among young children appears to increase iron status but further studies are required to assess the public health significance of this in a high‐resource setting with a low prevalence of iron deficiency. At risk subgroups of young children should continue to be targeted with policies to improve iron status.

Sources of funding

The National Children's Research Centre is the primary funding source for the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study. Additional support came from a grant from the UK Food Standards Agency to JO'BH, ADI and DMM and from Danone Nutricia Early Life Nutrition to MK The SCOPE Ireland Study was funded by the Health Research Board of Ireland (CSA 02/2007). LCK, MK and DMM are Principal Investigators (PI) in the Science Foundation Ireland funded INFANT Research Centre (grant no. 12/RC/2272). No funding agencies had any role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributions

EKM carried out data collection, database construction and data analysis. MK designed the study and EKM and MK drafted the manuscript. MK had responsibility for the final content. CnC. carried out data collection. DMM is the overall PI of the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study and JO'BH, LCK, ADI and MK are co‐PIs and specialist leads. LCK is the PI of the SCOPE Ireland pregnancy cohort study. All authors reviewed and approved the final submission.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families for their continued support and the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study research team.

McCarthy, E. K. , ní Chaoimh, C. , Hourihane, J. O. B. , Kenny, L. C. , Irvine, A. D. , Murray, D. M. , and Kiely, M. (2017) Iron intakes and status of 2‐year‐old children in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13: e12320. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12320.

References

- Bates B., Lennox A., Prentice A., Bates C., Page P., Nicholson S. et al (2014) National Diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2008/2009 – 2011/2012), The Department of Health and Food Standards Agency.

- Black L.J., Ireland J., Møller A., Roe M., Walton J., Flynn A. et al. (2011) Development of an on‐line Irish food composition database for nutrients. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 24 (7), 1017–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Brotanek J.M., Gosz J., Weitzman M. & Flores G. (2007) Iron deficiency in early childhood in the United States: risk factors and racial/ethnic disparities. Pediatrics 120 (3), 568–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke R.M., Leon J.S. & Suchdev P.S. (2014) Identification, prevention and treatment of iron deficiency during the first 1000 days. Nutrients 6 (10), 4093–4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capozzi L., Russo R., Bertocco F., Ferrara D. & Ferrara M. (2010) Diet and iron deficiency in the first year of life: a retrospective study. Hematology 15 (6), 410–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (1991) Dietary Reference Values for Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom. The Stationary Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Domellof M., Braegger C., Campoy C., Colomb V., Decsi T., Fewtrell M. et al. (2014) Iron requirements of infants and toddlers. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 58 (1), 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domellof M., Dewey K.G., Lonnerdal B., Cohen R.J. & Hernell O. (2002a) The diagnostic criteria for iron deficiency in infants should be reevaluated. Journal of Nutrition 132 (12), 3680–3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domellof M., Lonnerdal B., Dewey K.G., Cohen R.J., Rivera L.L. & Hernell O. (2002b) Sex differences in iron status during infancy. Pediatrics 110 (3), 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies (2013) Scientific Opinion on nutrient requirements and dietary intakes of infants and young children in the European Union. EFSA Journal 2013 11 (10), 3408. [Google Scholar]

- Eussen S., Alles M., Uijterschout L., Brus F. & Van Der Horst‐Graat J. (2015) Iron intake and status of children aged 6–36 months in Europe: a systematic review. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 66 (2–3), 80–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food Safety Authority of Ireland (2011) Scientific Recommendations for a National Infant Feeding Policy [Online]. Dublin, Ireland: FSAI. Available at https://www.fsai.ie/search-results.html?searchString=infant%20feeding [Accessed 8th January 2015].

- Food Standards Agency (2002) McCance and Widdowson's The Composition of Foods, Sixth, summary edn. Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Fox M.K., Reidy K., Novak T. & Ziegler P. (2006) Sources of energy and nutrients in the diets of infants and toddlers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 106 (1, Supplement), 28.e1–28.e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman V., Van't Hof M. & Haschke F. (2000) Patterns of milk and food intake in infants from birth to age 36 months: the Euro‐growth study. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 31 (Suppl 1), S76–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman V.E., Mulder J., Van't Hof M.A., Hoey H.M. & Gibney M.J. (1998) A longitudinal study of iron status in children at 12, 24 and 36 months. Public Health Nutrition 1 (2), 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieff M.K. (2011) Long‐term brain and behavioral consequences of early iron deficiency. Nutrition Reviews 69 (Suppl 1), S43–S48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisolfi J., Fantino M., Turck D., De Courcy G.P. & Vidailhet M. (2013) Nutrient intakes of children aged 1–2 years as a function of milk consumption, cows' milk or growing‐up milk. Public Health Nutrition 16 (3), 524–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson B.S., Thorsdottir I. & Palsson G. (2004) Iron status in 2‐year‐old Icelandic children and associations with dietary intake and growth. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 58 (6), 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsson B.S., Thorsdottir I. & Palsson G. (2007) Associations of iron status with dietary and other factors in 6‐year‐old children. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 61 (3), 398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay G., Sandstad B., Whitelaw A. & Borch‐Iohnsen B. (2004) Iron status in a group of Norwegian children aged 6–24 months. Acta Paediatrica 93 (5), 592–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland B., Welch A., Unwin I.D., Buss D.H., Paul A. & Southgate D. (1995) McCance and Widdowson's The Composition of Foods, 5th edn. HMSO: London. [Google Scholar]

- Irish Universities Nutrition Alliance (2012) National Pre‐School Nutrition Survey [Online]. Available at http://www.iuna.net [Accessed 25th March 2014].

- Krebs‐Smith S.M., Kott P.S. & Guenther P.M. (1989) Mean proportion and population proportion: two answers to the same question? Journal of the American Dietetic Association 89 (5), 671–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs N.F., Sherlock L.G., Westcott J., Culbertson D., Hambidge K.M., Feazel L.M. et al. (2013) Effects of different complementary feeding regimens on iron status and enteric microbiota in breastfed infants. Journal of Pediatrics 163 (2), 416–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyttala P., Erkkola M., Kronberg‐Kippila C., Tapanainen H., Veijola R., Simell O. et al. (2010) Food consumption and nutrient intake in Finnish 1–6‐year‐old children. Public Health Nutrition 13 (6a), 947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennox A., Sommerville J., Ong K., Henderson H. & Allen R. (2011) Diet and Nutrition Survey of Infants and Young Children, 2011, The Department of Health and Food Standards Agency.

- Lind T., Hernell O., Lonnerdal B., Stenlund H., Domellof M. & Persson L.A. (2004) Dietary iron intake is positively associated with hemoglobin concentration during infancy but not during the second year of life. Journal of Nutrition 134 (5), 1064–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone M.B., Robson P.J. & Wallace J.M. (2004) Issues in dietary intake assessment of children and adolescents. British Journal of Nutrition 92 (Suppl 2), S213–S222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozoff B., Beard J., Connor J., Barbara F., Georgieff M. & Schallert T. (2006) Long‐lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutrition Reviews 64 (5 Pt 2), S34–43 discussion S72–S91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclean E., Cogswell M., Egli I., Wojdyla D. & De Benoist B. (2009) Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993–2005. Public Health Nutrition 12 (4), 444–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelsen K.F., Milman N. & Samuelson G. (1995) A longitudinal study of iron status in healthy Danish infants: effects of early iron status, growth velocity and dietary factors. Acta Paediatrica 84 (9), 1035–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North R.A., Mccowan L.M., Dekker G.A., Poston L., Chan E.H., Stewart A.W. et al. (2011) Clinical risk prediction for pre‐eclampsia in nulliparous women: development of model in international prospective cohort. British Medical Journal 342, d1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan S.M., Murray D.M., Hourihane J.O., Kenny L.C., Irvine A.D. & Kiely M. (2015a) Cohort profile: The Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study: Babies after SCOPE: Evaluating the Longitudinal Impact on Neurological and Nutritional Endpoints. International Journal of Epidemiology 44, 764–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donovan S.M., Murray D.M., Hourihane J.O., Kenny L.C., Irvine A.D. & Kiely M. (2015b) Adherence with early infant feeding and complementary feeding guidelines in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study. Public Health Nutrition 18, 2864–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocké M.C., Van Rossum C.T.M., Fransen H.P., Buurma‐Rethans E.J.M., De Boer E.J., Brants H.a.M. et al. (2008) Dutch National Food Consumption Survey—Young Children 2005/2006. RIVM: Bilthoven. [Google Scholar]

- Pasricha S.R., Black J., Muthayya S., Shet A., Bhat V., Nagaraj S. et al. (2010) Determinants of anemia among young children in rural India. Pediatrics 126 (1), e140–e149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield W.N., Schofield C. & James W.P.T. (1985) Basal metabolic rate. Human Nutrition. Clinical Nutrition 39C, 5–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (2010) Iron and Health. The Stationary Office: London. [Google Scholar]

- Sherriff A., Emond A., Hawkins N. & Golding J. (1999) Haemoglobin and ferritin concentrations in children aged 12 and 18 months. ALSPAC Children in Focus Study Team. Archives of Disease in Childhood 80 (2), 153–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thane C.W., Walmsley C.M., Bates C.J., Prentice A. & Cole T.J. (2000) Risk factors for poor iron status in British toddlers: further analysis of data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of children aged 1.5–4.5 years. Public Health Nutrition 3 (4), 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorisdottir A.V., Ramel A., Palsson G.I., Tomassson H. & Thorsdottir I. (2013) Iron status of one‐year‐olds and association with breast milk, cow's milk or formula in late infancy. European Journal of Nutrition 52 (6), 1661–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsdottir I., Gunnarsson B.S., Atladottir H., Michaelsen K.F. & Palsson G. (2003) Iron status at 12 months of age—effects of body size, growth and diet in a population with high birth weight. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57 (4), 505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torun B., Davies P.S., Livingstone M.B., Paolisso M., Sackett R. & Spurr G.B. (1996) Energy requirements and dietary energy recommendations for children and adolescents 1 to 18 years old. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50, S37–S80 discussion S80–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uijterschout L., Vloemans J., Vos R., Teunisse P.P., Hudig C., Bubbers S. et al. (2014) Prevalence and risk factors of iron deficiency in healthy young children in the southwestern Netherlands. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 58 (2), 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton J. & Flynn A. (2013) Nutritional adequacy of diets containing growing up milks or unfortified cow's milk in Irish children (aged 12–24 months). Food and Nutrition Research 57, 21836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (2008) Worldwide Prevalence of Anaemia 1993–2005 WHO Global Database on Anaemia. WHO: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004) Assessing the Iron Status of Populations. WHO: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.J., Gibson R.A., Gibson R.S. & Makrides M. (2012) Nutrient intakes and status of preschool children in Adelaide, South Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 196 (11), 696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler E.E. (2011) Consumption of cow's milk as a cause of iron deficiency in infants and toddlers. Nutrition Reviews 69 (Suppl 1), S37–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]