Abstract

Excess gestational weight gain has numerous negative health outcomes for women and children, including high blood pressure, diabetes, and cesarean section (maternal) and high birth weight, trauma at birth, and asphyxia (infants). Excess weight gain in pregnancy is associated with a higher risk of long‐term obesity in both mothers and children. Despite a concerted public health effort, the proportion of pregnant women gaining weight in excess of national guidelines continues to increase. To understand this phenomenon and offer suggestions for improving interventions, we conducted a systematic review of qualitative research on pregnant women's perceptions and experiences of weight gain in pregnancy. We used the methodology of qualitative meta‐synthesis to analyze 42 empirical qualitative research studies conducted in high‐income countries and published between 2005 and 2015. With this synthesis, we provide an account of the underlying factors and circumstances (barriers, facilitators, and motivators) that pregnant women identify as important for appropriate weight gain. We also offer a description of the strategies identified by pregnant women as acceptable and appropriate ways to promote healthy weight gain. Through our integrative analysis, we identify women's common perception on the struggle to enact health behaviors and physical, social, and environmental factors outside of their control. Effective and sensitive interventions to encourage healthy weight gain in pregnancy must consider the social environment in which decisions about weight take place.

Keywords: gestational weight gain, maternal nutrition, physical activity, qualitative meta‐synthesis, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

More than half of pregnant women exceed clinical practice guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy (Chung et al., 2013; Durie, Thornburg, & Glantz, 2011; Kowal, Kuk, & Tamim, 2012; Park et al., 2011; Simas et al., 2011), increasing the risk of negative health outcomes for women and infants (Cedergren, 2006; Gillman, 2012; Lucia Bergmann et al., 2007; Johnston, McNeil, Best, & MacLeod, 2011; Nohr et al., 2009; Rooney & Schauberger, 2002; Rooney, Schauberger, & Mathiason, 2005; Thorsdottir, Gunnarsdottir, Kvaran, & Gretarsson, 2005). There is international variation in clinical guidelines for gestational weight gain, with the most widely used guidelines published by the American Institutes of Medicine (Table 1) Alavi, Haley, Chow, & McDonald, 2013; (Institutes of Medicine, 2009). When pregnant women gain more than the recommended amount of weight, they face increased risk of high blood pressure (Cedergren, 2006; de la Torre et al., 2011), diabetes (Mamun et al., 2010; Thorsdottir et al., 2005), cesarean section (Crane, White, Murphy, Burrage, & Hutchens, 2009), postpartum weight retention (Mannan, Doi, & Mamun, 2013; Nehring, Schmoll, Beyerlein, Hauner, & von Kries, 2011; Siega‐Riz et al., 2009), and obesity (Rooney et al., 2005). When mothers gain more than the recommended amount of weight, infants are likely to be large for gestational age (Herring, Rose, Skouteris, & Oken, 2012b; Lucia Bergmann et al., 2007; Mamun et al., 2010; Nohr et al., 2009), which carries risks of trauma at birth, asphyxia (Nesbitt, Gilbert, & Herrchen, 1998), gastroschisis (Yang et al., 2012), pre‐term delivery (Han et al., 2011), and increases risk of metabolic disorders and higher weight later in life (Hinkle et al., 2012; Poston, 2012; Sridhar et al., 2014).

Table 1.

2009Institute of Medicine (IOM), recommendations for total weight gain during pregnancy, by pre‐pregnancy BMI

| Pre‐pregnancy BMI | BMI (kg/m2) | Total weight gain range (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 | 12.7–18 |

| Normal weight | 18.5–24.9 | 11.3–15.9 |

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 | 6.8–11.3 |

| Obese (all classes) | >30 | 5–9 |

Note. BMI = body mass index.

There are many potential relationships between excess weight gain during pregnancy and long‐term weight retention, including biological and socio‐environmental mechanisms. For example, excess nutrients in utero result in increased fetal fat mass (Martin, Hausman, & Hausman, 1998), both from the addition of new adipocytes and from increased size of existing ones (Lewis et al., 2013). High birth weight doubles the chances of being overweight and obese during adolescence and adulthood (Yu et al., 2013; Schellong, Schulz, Harder, & Plagemann, 2012). For women, those who gain more than the recommended amount of weight during pregnancy are two to three times more likely to remain at a higher weight after delivery, an important predictor for obesity in midlife (Gunderson, 2009; Rooney et al., 2005). Gestational weight gain above recommendations is more prevalent among women who started pregnancy with a higher body mass index (BMI). This may reflect the lower level of weight gain recommended by the American Institutes of Medicine (IOM) for women with higher pre‐pregnancy BMIs (Institutes of Medicine, 2009). It may also suggest that the social and structural factors that influence gestational weight gain also contribute to weight gain outside of pregnancy, for both mothers and children (Bennett, Wolin, & Duncan, 2008; Deputy, Sharma, Kim, & Hinkle, 2015). For example, living in poverty may encourage weight gain because living in a neighborhood where fresh food is not available, transportation options are restricted, and fresh, healthy food is expensive may result in a reliance on low‐cost, high‐calorie food (Bennett et al., 2008; Drewnowski & Specter, 2004; Power, 2005).

These social and structural factors may help explain why higher weight is disproportionately prevalent in people who are born in developed nations or who have become acculturated after a long duration of residence (Antecol & Bedard, 2006; McDonald & Kennedy, 2005; Tremblay, Katzmarzyk, Bryan, Perez, & Ardern, 2005), women with low income and low education levels (Manios, Panagiotakos, Pitsavos, Polychronopoulos, & Stefanadis, 2005; Mujahid, Roux, Borrell, & Nieto, 2005), those who live in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhood (Cubbin, Hadden, & Winkleby, 2000; Ellaway, Anderson, & Macintyre, 1997; Mujahid et al., 2005; Sundquist & Winkleby, 2000), those who experience chronic stress (Marniemi et al., 2002; Korkeila, Kaprio, Rissanen, Koskenvuo, & Sörensen, 1998), depression (Jorm et al., 2003; Kress, Peterson, & Hartzell, 2006), and low levels of social support (Räikkönen, Matthews, & Kuller, 1999; Lallukka, Laaksonen, Martikainen, Sarlio‐Lähteenkorva, & Lahelma, 2005).

Despite the recognized importance of healthy weight gain in pregnancy, the proportion of women continuing to exceed national guidelines for gestational weight gain continues to increase (Deputy et al., 2015; Fell et al., 2005). The success of interventions to prevent excess weight gain during pregnancy has varied (Muktabhant, Lawrie, Lumbiganon, & Laopaiboon, 2015; Thangaratinam et al., 2012; Kinnunen et al., 2007; Guelinckx, Devlieger, Mullie, & Vansant, 2010; Gray‐Donald et al., 2000). As a result, the format and intensity of effective interventions remains uncertain (Dodd, Grivell, Crowther, & Robinson, 2010). Given the intractability of the issue of gestational weight gain, we decided to examine women's perspectives through an analysis of existing qualitative evidence, asking the following questions: What do pregnant women identify as the underlying factors and circumstances (e.g., barriers, motivators, and facilitators) to appropriate weight gain? What do pregnant women identify as acceptable and appropriate strategies to promote healthy weight gain?

This systematic review and qualitative meta‐synthesis examines recent published qualitative research to compile evidence about women's understandings, perceptions, and values about weight gain in pregnancy. The evidence described in this review may inform clinical practice for health professionals counselling pregnant women about nutrition and weight, and may support the modification or development of future intervention programs.

Key messages

Women are highly motivated to change their behavior to improve fetal health, but may not recognize the link between excess gestational weight gain and negative fetal health outcomes.

Weight gain in pregnancy occurs within a complex social environment and is affected by intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, structural, and environmental factors. Women facing social disadvantage may face additional barriers to appropriate weight gain, and may not have access to mitigating resources.

Weight gain is a sensitive topic, and thorough counselling takes significant clinician time. Regular, forthright, sensitive counselling geared to individual circumstances was frequently mentioned as a strong facilitator of healthy weight gain in pregnancy.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

We conducted a literature search using OVID Medline, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and ISI Web of Science Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI). We limited the search to papers published since 2005 in order to capture literature that reflected recent evidence relevant to pregnant women's perspectives while maintaining a manageable amount of information for qualitative meta‐synthesis. Given the importance of socio‐environmental factors to weight gain (Bennett et al., 2008), we limited our search to high‐income countries for ease of comparison across regions. Included studies were performed in Canada, the United States, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. The search strategies combined multiple published filters for qualitative research (DeJean, Giacomini, Simeonov, & Smith, 2016) with a gestational weight gain search filter developed in collaboration with information scientists. Two authors read titles and abstracts. If consensus was not reached with a title and abstract review, the full text was reviewed for eligibility and discussed by three authors.

2.1. Inclusion criteria

We included studies that were published between January 1, 2005 and January 31, 2015. They consisted of primary, empirical qualitative research using any descriptive or interpretive qualitative methodology. Eligible publications studied a female adult patient population (>18 years of age) who were currently or had been pregnant. The studies addressed any aspect of the experience of weight gain, nutrition, food, or meals during pregnancy and were conducted in high‐income countries. Included studies were published in English and available either through the McMaster University library system or from the corresponding author.

We excluded studies when the topic of experiences of weight gain in pregnancy was not sufficiently prominent to merit mention in the title or abstract. We excluded studies that primarily addressed the experiences of people who were not pregnant women (e.g., health care providers), those not published in English, and those that did not use primary empirical data. We excluded quantitative research (e.g., studies that used statistical hypothesis testing, quantitative data and analyses, or those that expressed results in quantitative or statistical terms).

We did not limit our search by type of qualitative methodology; we included all published qualitative research relevant to our research questions. Consistent with our synthesis methodology, we excluded studies only when we could discern no data to support the findings (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003b). This approach looks for empirical evidence in support of the reported judgments as a way to evaluate the rigor of qualitative research. The decision not to exclude qualitative research on the basis of independently assessed quality is an epistemologically valid response to the ongoing debate among qualitative researchers about what constitutes methodological adherence and quality (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003a; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003b; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2006), and is common to multiple types of interpretive qualitative syntheses (Barnett‐Page & Thomas, 2009; Noblit & Hare, 1988; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003b; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003a; Saini & Shlonsky, 2012). This decision recognizes that procedural details are typically under‐reported and the quality of findings is less dependent on methodological processes and procedures than on the conceptual prowess of the researchers (Melia, 2010). It also recognizes that some hallmarks of independent quality assessments (e.g., theoretical sophistication) may be important for assessing whether a study makes a valuable contribution to social science academic disciplines, but that theoretically sophisticated findings are not necessary to contribute valuable information to a synthesis of multiple studies, or to inform applied health research questions. This study did not require research ethics approval, as all data were previously published.

2.2. ANALYTICAL METHOD

We used the integrative technique of qualitative meta‐synthesis (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003b; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2006). Qualitative meta‐synthesis combines the findings from multiple studies to produce evidence that retains both the original meaning of the authors while simultaneously offering a new description and interpretation of the phenomenon (Saini & Shlonsky, 2012). Consistent with this methodology, we started with a predefined research question developed by the team and knowledge user partners. This question guided the development of the search strategy, determination of relevance, and identification of findings extracted as data for analysis. The following are our research questions: What do pregnant women identify as the underlying factors and circumstances (e.g., barriers, motivators, or facilitators) to appropriate weight gain? What do pregnant women identify as acceptable and appropriate strategies to promote healthy weight gain?

We used the researchers' qualitative findings as data. Sandelowski defines findings as the “data‐driven and integrated discoveries, judgments, and/or pronouncements researchers offer about the phenomena, events, or cases under investigation” (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003b). At least two researchers extracted data, with discrepancies resolved through team consensus. After data extraction, we used a staged coding process similar to that used in grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006; Corbin, 2008) to break the studies' findings into their component parts (key themes, categories, concepts, etc.), which we then thematically re‐grouped across studies. Using inductive (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003a; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003b) and constant comparative (Corbin, 2008) approaches, we developed categories based on relevance to research question, prevalence, and coherence across a large number of studies. We also developed categories for findings that had potential for a significance or useful contribution across a smaller number of studies.

3. RESULTS

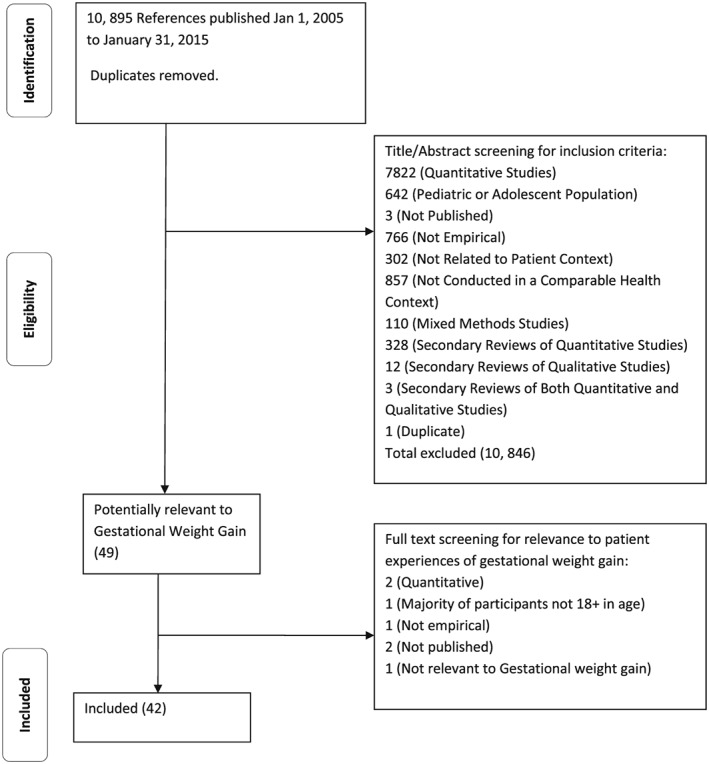

Figure 1 shows the search process, from which 42 papers were included representing qualitative data from 1,339 participants. Some of the papers included the same data set, and in this case, their participants were only counted once. Tables 2, 3, 4 describe the included studies, including geographic location, methodology, and forms of social marginalization studied, respectively. There was little consistency in the sampling and reporting strategies about stage of pregnancy or gestational age, with studies including women at all stages of pregnancy and those who are recently post‐partum. With the information provided about geographic location of the studies in Table 2, we have also included information about national gestational weight gain guidelines. Six of seven included countries (Canada, United States, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Australia) endorse the IOM weight gain recommendations (Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council, 2012; Expert Advisory Group on National Nutrition Pregnancy Guidelines, 2010; Institutes of Medicine, 2009; Norden, 2012). The seventh country, the United Kingdom, does not offer specific guidelines for recommended weight gain, instead emphasizing that that antenatal counselling should include individualized advice on nutrition and physical activity (Public Health Interventions Advisory Committee, 2010). Table 5 is a list of all included studies.

Figure 1.

Systematic review search process

Table 2.

Included studies, by location and applicable gestational weight gain guideline

| Study location | Current gestational weight gain guideline | Endorse IOM weight gain range? | Number of eligible studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council (2012) | Y | 4 (9.5%) |

| Canada | Health Canada (Expert Advisory Group on National Nutrition Pregnancy Guidelines, 2010) | Y | 4 (9.5%) |

| Europe | 18 (17%) | ||

| •UK | NICE (Public Health Interventions Advisory Committee, 2010) | N | 13 (30%) |

| •Denmark | Nordic Nutrit. Rec (Norden 2012) | Y | 1 (2%) |

| •Sweden | Nordic Nutrit. Rec (2012) | Y | 3 (7%) |

| •Norway | Nordic Nutrit. Rec (2012) | Y | 1 (2%) |

| United States | American Institutes of Medicine (IOM) (Institutes of Medicine 2009) | ‐ | 16 (38%) |

| Total | 42 (100%) | ||

Table 3.

Included studies, by study design

| Study design | Number of eligible studies |

|---|---|

| Content analysis | 5 (12%) |

| Thematic analysis | 10 (24%) |

| Framework analysis | 4 (9%) |

| Discourse analysis | 2 (5%) |

| Qualitative description | 3 (7%) |

| Grounded theory/constant comparative analysis | 5 (12%) |

| Phenomenological | 3 (7%) |

| Qualitative but not otherwise specified | 7 (17%) |

| Other (ethnography, situational analysis, community‐based participatory research) | 3 (7%) |

| Total | 42 (100%) |

Table 4.

Included studies, by type of social marginalization

| Type of marginalization identified | Number of eligible studies |

|---|---|

| Minority ethnicity or culture | 13 (31%) |

| Immigrant | 1 (2%) |

| Non‐immigrant | 12 (29%) |

| Both | 0 (0%) |

| Low socioeconomic status | 13 (31%) |

| Rural dweller | 2 (5%) |

| Overweight/obese | 13 (31%) |

| Any type of social marginalizationa | 29 (69%) |

About 29/42 (69%) of studies mentioned at least one type of social marginalization, many mentioned more than one type of marginalization.

Table 5.

List of included studies

| Citation | Country | Design | Participant # | Type of marginalization | Research question/objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arden et al., 2014 | UK | Thematic analysis | 202 women | To explore women's perspectives about gestational weight gain guidance using spontaneous and naturally occurring comments made in posts on online public parenting forums. | |

| Black et al., 2008 | Canada | Ethnography | 13 women | ‐Low SES | To examine the determinants of excessive prenatal weight gain in First Nations women living on a reserve. |

| ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (First Nations) | |||||

| ‐Rural | |||||

| Duthie et al., 2013 | USA | Thematic analysis | 19 women | To describe (1) what obstetricians communicate about GWG to their patients, as well as what they communicate to their patients about weight loss in the postpartum period; (2) the experiences women have communicating with their obstetricians about GWG. | |

| 7 obstetricians | |||||

| Edvardsson et al., 2011 | Sweden | Qualitative manifest and latent content analysis | 12 couples | To explore Swedish first‐time parents' experiences of health promotion and lifestyle change during pregnancy and early parenthood. | |

| Evenson et al., 2009 | USA | Thematic analysis | 58 women | To understand pregnant women's perceptions of barriers to physical activity. | |

| Ferrari et al., 2013 | USA | Qualitative, not specified | 58 women | ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (African American, Hispanic) | To gather insights into pregnant women's experiences with provider advice about diet and physical activity. |

| Furber & McGowan, 2011 | UK | Framework analysis | 19 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To explore the experiences related to obesity in women with a body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2 during the childbearing process. |

| Furness et al., 2011 | UK | Thematic analysis | 6 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To explore women's experiences of managing weight in pregnancy and the perceptions of women, midwives and obstetricians of services to support obese pregnant women in managing their weight. |

| 7 midwives | |||||

| Garnweidner et al., 2013 | Norway | Interpretive phenomenology | 17 women | ‐Immigrant minority culture (different ethnic backgrounds) | To explore experiences with nutrition‐related information during routine antenatal care among women of different ethnic backgrounds. |

| Goodrich et al., 2013 | USA | Qualitative, not specified | 33 women | ‐Low SES | To better inform intervention messages by eliciting information on perceptions of appropriate weight gain, barriers to and enablers of exercise and healthy eating, and other influences on healthy weight gain during pregnancy in overweight or obese African American women. |

| ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (African American) | |||||

| ‐Overweight or obese | |||||

| Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013 | USA | Content analysis | 26 womena | ‐Low SES | To gain insight into how low‐income, pregnant, African American women viewed physical activity and approached nutrition during pregnancy. |

| ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (African American) | |||||

| Groth et al., 2012 | USA | Content analysis | 26 womena | ‐Low SES | To gain insight into how low‐income, pregnant African American women viewed their weight gain while pregnant and how they managed their weight during pregnancy. |

| ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (African American) | |||||

| Groth & Kearney, 2009 | USA | Content analysis | 49 women | ‐Low SES | To describe ethnically diverse new mothers' perceptions of gestational weight gain. |

| ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (different ethnic backgrounds) | |||||

| Harper & Rail, 2012 | Canada | Discourse analysis | 15 womenb | To explore how pregnant young women construct their subjectivities either within dominant discourse on health and obesity or possibly resistant discourses. | |

| Hearn et al., 2013 | Australia | Qualitative, not specified | 116 womenc | To determine what online information perinatal women and primary healthcare providers want, in what form, and how best it should be presented. | |

| 76 primary healthcare providers | |||||

| Hearn et al., 2014 | Australia | Qualitative, not specified | 120 womenc | To design and develop an online resource to promote healthy lifestyles during the perinatal period. | |

| 76 primary healthcare providers | |||||

| Heery et al., 2013 | UK | Thematic analysis | 21 women | To explore views about weight gain and lifestyle practices during pregnancy among women with a history of macrosomia. | |

| Herring et al., 2012a | USA | Grounded theory | 31 women | ‐Low SES | To understand the perceptions of urban, low‐income, pregnant African‐Americans about high weight gain in pregnancy, specifically focused on factors that contribute to higher gains, sources of weight gain advice, weight‐related health risks, and barriers and facilitators to gaining within recommended levels. |

| ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (African American) | |||||

| Huberty et al., 2010 | USA | Qualitative description | 32 women | ‐Low SES | To explore beliefs about health and body weight in young perinatal women. |

| Jette & Rail, 2014 | Canada | Discourse analysis | 15 womenb | ‐Low SES | To explore how low‐income women of diverse sociocultural location construct and experience health and weight gain during pregnancy, as well as how they position themselves in relation to messages pertaining to weight gain, femininity and motherhood that they encounter in their lives. |

| Keely et al., 2011 | UK | Qualitative, not specified | 8 women | To explore obese women's perceptions of obesity as a risk factor in pregnancy and their experiences of NHS maternity care. | |

| Keenan & Stapleton, 2010 | UK | Thematic analysis | 60 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To use longitudinal interview data from large‐bodied women in their transitions to motherhood, to explore how this powerful biomedical discourse plays out in women's reported interactions with maternity professionals in pregnancy, birth and the months that follow. |

| Khazaezadeh et al., 2011 | UK | Framework analysis | 12 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To interview obese pregnant women and obese women trying to conceive to identify and understand the healthcare needs of service users in Lambeth in south‐east London. |

| Krans & Chang, 2011 | USA | Grounded theory | 34 women | ‐Low SES | To identify pregnant, low‐income African American women's barriers and facilitators to exercise during pregnancy. |

| ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (African American) | |||||

| Lindhardt et al., 2013 | Denmark | Phenomenology | 16 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To examine the experience of women with a pre‐pregnant BMI > 30 kg/m2, in their encounters with healthcare professionals during pregnancy. |

| Mills et al., 2013 | Australia | Qualitative description | 14 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To explore the perceptions and experiences of overweight pregnant women attending two maternity units in Sydney, Australia. |

| Nash, 2012 | Australia | Situational analysis | 38 women | To draw on longitudinal narrative data to examine experiences of weight gain and ‘fatness’ in early periods of pregnancy among women in Melbourne, Australia. | |

| Nyman et al., 2010 | Sweden | Phenomenology | 10 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To describe obese women's experiences of encounters with midwives and physicians during pregnancy and childbirth. |

| Olander & Atkinson, 2013 | UK | Thematic analysis | 16 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To elicit the reasons why obese pregnant women decline to participate in weight management services and to identify their barriers to participation. |

| Olander et al., 2011 | UK | Thematic analysis | 23 womend | To explore the views of pre‐ and post‐natal women and health professionals regarding gestational weight gain which may inform the design of future interventions targeting gestational weight gain. | |

| 7 healthcare professionals | |||||

| Olander et al., 2012 | UK | Thematic analysis | 23 womend | To identify characteristics of the services and support women want to enable them to eat healthily during pregnancy to make a potential future service acceptable. | |

| Paul et al., 2013 | USA | Constant comparison | 26 women | ‐Low SES | To gain an in‐depth understanding of issues related to GWG including general health, diet, and physical activity among high and low income women and to elucidate socioecological and psychosocial risk factors that increase risk for excessive GWG. |

| Reyes et al., 2013 | USA | Grounded theory | 21 women | ‐Low SES | To better understand the contextual factors that may influence low‐income African‐American mothers' diet quality during pregnancy. |

| ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (African American) | |||||

| Smith et al., 2013 | UK | Thematic analysis | 14 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To examine whether weight management guides designed for women with a BMI > 30 kg/m2, are accessible and appropriate for pregnant women with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2. |

| Stengel et al., 2012 | USA | Grounded theory | 24 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To use interview overweight and obese women after the birth of their first child to ascertain their experiences with GWG and to identify themes on provider advice received about GWG and physical activity during pregnancy. |

| Stringer et al., 2010 | UK | Framework analysis | 8 women | ‐Eating disorder | To explore the experiences of pregnant women with an eating disorder and during the early years of the child's life, including their views of healthcare provision. |

| Thomas et al., 2014 | USA | Qualitative, not specified | 59 women | ‐Low SES | To develop a mindfulness‐based stress reduction and nutrition intervention for low‐income, overweight and obese pregnant women, with healthy GWG as the primary outcome measure. |

| ‐Overweight or obese | |||||

| Thornton et al., 2006 | USA | Community‐based participatory research | 10 women and their support person (e.g. spouse) | ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (Hispanic) | To investigate the influence of social support on weight, diet, and physical activity‐related beliefs and behaviors among pregnant and postpartum Latinas. |

| Tovar et al., 2010 | USA | Qualitative, not specified | 29 women | ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (Hispanic) | To evaluate knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding weight gain during pregnancy among predominantly Puerto Rican women. |

| Vallianatos et al., 2006 | Canada | Qualitative description | 30 women | ‐Rural | To explore (1) Cree women's perceptions of weight gain in pregnancy and weight loss following pregnancy, (2) the barriers that women face in maintaining a healthy body weight, and (3) the sociocultural context of health. |

| ‐Non‐immigrant minority culture (First Nations) | |||||

| ‐Low SES | |||||

| Weir et al., 2010 | UK | Framework analysis | 14 women | ‐Overweight or obese | To explore the views and experiences of overweight and obese pregnant women; and to inform interventions which could promote the adoption of physical activity during pregnancy. |

| Wennberg et al., 2013 | Sweden | Qualitative content analysis | 23 women | To describe women's experiences of dietary information and the change of dietary habits during pregnancy. |

Note. GWG = gestational weight gain.

Our analysis of women's understandings of gestational weight gain indicates that while women are very motivated to make lifestyle changes to improve the health of their future child, they experience myriad barriers to achieving gestational weight gain within clinical guidelines. To understand existing qualitative evidence on the underlying factors and circumstances that influence gestational weight gain, we outline women's descriptions of general barriers and facilitators to weight gain, and then concentrate more specifically on barriers and facilitators related to eating habits and to physical activity. In each section, we describe selected barriers identified in each theme; a comprehensive list is available in Table 6. We conclude this section by highlighting strategies women describe as acceptable for preventing excess weight gain.

Table 6.

Barriers and related facilitators to appropriate gestational weight gain identified by pregnant women

| Barrier to: | Barrier category | Specific barrier | Related facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eating habits | Knowledge | Do not understand how to operationalize directive to “eat healthy” | Community‐based cooking and nutrition class geared to pregnancy and young families. |

| Lack of cooking skills | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Nutrition advice not culturally relevant | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Nutrition info contradictory, confusing, changing | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Beliefs | Assume quick postpartum weight loss | Experience of excess gestational weight gain from a previous pregnancy | |

| Pregnancy is a vacation from worrying about weight | Information about fetal and maternal health benefits of weight control | ||

| Pregnancy is a time to enjoy foods normally avoided | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Concern about providing enough nutrients for baby | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Pregnancy is a time to eat for two | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Quality, not quantity of food is what is important | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Cravings, aversions determined by baby, body's way of communicating what food to eat or avoid | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Physical | Intense hunger | No facilitators mentioned | |

| Nausea and aversions | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Sugar helps overcome fatigue | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Cravings | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Social | Frequently eating outside the home | No facilitators mentioned | |

| Encouragement from friends/family to overeat or gain weight | Education that includes friends/family | ||

| Family members have preference for unhealthy food | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Judgement about diet, weight gain from family members/friends | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Loneliness, isolation, lack of social support | |||

| Logistic | Lack of time for planning, shopping, cooking | Healthy recipes that are cheap and quick to prepare | |

| Emotional/psychosocial | Compensating for other deprivations (alcohol, cigarettes) with junk food | No facilitators mentioned | |

| Emotional eating as a reaction to stress, depression | Mindfulness and stress‐reduction interventions | ||

| Pleasure from junk food | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Structural | Accessibility, prevalence of fast food | No facilitators mentioned | |

| Financial | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Difficulty accessing healthy, fresh food | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Chronic stress | Mindfulness and stress‐reduction interventions | ||

| Physical Activity (PA) | Knowledge | Do not know suitable exercises, intensity, duration for pregnancy | Exercise classes for pregnant women |

| Do not know about importance of exercise in pregnancy | Counselling about PA from health care provider | ||

| Health care provider advises very conservative exercise regimen | Seeking alternative sources of information | ||

| Beliefs | Activity of everyday life is sufficient PA | Finding ways to include more activity in everyday routine | |

| PA can harm fetus | Counselling about PA from health care provider | ||

| Gentle exercise (e.g., walking or stretching) is sufficient | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Pregnancy is a time for rest | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Not motivated to exercise | Recognizing positive physical feelings after exercise | ||

| Physical | Fatigue | No facilitators mentioned | |

| Nausea | Exercise classes for pregnant women | ||

| Pregnancy‐related soreness, pain, mobility limitation | |||

| Shortness of breath | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Social | Stigma of exercising while obese/overweight | Exercise classes for overweight pregnant women | |

| Family/partner preventing activity, removing active tasks | Information aimed at family, partners | ||

| Loneliness, isolation, lack of social support that encourages activity | Exercise classes for pregnant women | ||

| Logistic | Childcare | Community‐based exercise programs that have childcare, exercise ideas for the whole family | |

| Lack of time | Finding ways to include more activity in everyday routine | ||

| Sedentary job | |||

| Weather prohibitive to outdoor activity | Free, safe, accessible indoor places for exercise | ||

| Structural | Finances | Free, safe, community‐based locations for exercise | |

| General | Knowledge | Do not understand importance of weight control | HCP forthcoming with sensitive advice about weight, regularly, starting early in pregnancy |

| Inconsistent messages about weight from health care providers | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Information received too late in pregnancy | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Do not understand how to achieve weight control | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Information alone not sufficient to motivate change | Other motivators: health of fetus, feeling good, maintaining function, easier postpartum weight loss | ||

| Beliefs | Disagree with health care provider advice about weight control in pregnancy | Build trust with HCP | |

| Health of baby determines appropriate weight gain | HCP forthcoming with evidence‐based, clear, sensitive advice about weight that takes individual circumstances into consideration | ||

| Big babies are healthy babies | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Lifestyle, listening to body is more important than scale | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Understanding of weight target inconsistent with Institute of Medicine guidelines | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Inaccurate understanding of pre‐pregnancy weight status | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Desire for individualized recommendations | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Weight gain and retention is uncontrollable | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Physical | Genetics | No facilitators mentioned | |

| Maternal age | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Medical conditions | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Social | Crude or cruel comments from others | Education opportunities that include family members | |

| Pressure to follow family advice over HCP advice | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Stigma of weight affects interactions with health care professionals | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Logistic | Rely on HCP to alert to a weight issue | HCP forthcoming with sensitive advice about weight, regularly, starting early in pregnancy | |

| No regular weight monitoring | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Struggle to maintain lifestyle changes over time | No facilitators mentioned | ||

| Emotional | Feelings of guilt and blame for weight lead to overeating | No facilitators mentioned | |

| Not ready to change lifestyle while pregnant | Recognizing positive effects of making change in pregnancy |

Note. HCP = health care providers.

Within the studies we analyzed, women create a detailed picture of the challenges to limiting excess weight gain, which is often in contrast to the biomedical view of weight gain as a matter of controlling energy intake and output. Women “reported that the health care professionals think obesity is just an energy imbalance, without considering other medical, psychological, or social factors involved” (Arden, Duxbury, & Soltani, 2014 pg.5). Women in several studies discuss gestational weight gain as uncontrollable (Garnweidner, Pettersen, & Mosdol, 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Groth, Morrison‐Beedy, & Meng, 2012; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery, McConnon, Kelleher, Wall, & McAuliffe, 2013; Paul, Graham, & Olson, 2013; Vallianatos et al., 2006; Weir et al., 2010) or feeling that weight gain was at the mercy of the physical symptoms of pregnancy (e.g., nausea, fatigue, cravings and aversions, pain, and soreness) (Arden et al., 2014; Black, Raine, & Willows, 2008; Furness et al., 2011; Goodrich, Cregger, Wilcox, & Liu, 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring, Henry, Klotz, Foster, & Whitaker, 2012a; Olander, Atkinson, Edmunds, & French, 2011; Paul et al., 2013; Reyes, Klotz, & Herring, 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Tovar, Chasan‐Taber, Bermudez, Hyatt, & Must, 2010; Wennberg, Lundqvist, Hogberg, Sandstrom, & Hamberg, 2013) and the broader circumstances of their lives (e.g., work and family commitments, financial resources, and social pressures) (Black et al., 2008; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Groth et al., 2012; Jette & Rail, 2014; Krans & Chang, 2011; Reyes et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2014; Thornton et al., 2006; Vallianatos et al., 2006). Barriers to healthy weight gain were broad and varied, encompassing beliefs, knowledge, emotional, logistical, practical, social, and structural factors (see Table 6), whereas identified facilitators were typically focused on factors related to higher incomes, supportive families, and a trusting relationship with an informative health care provider (Black et al., 2008; Furness et al., 2011; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Goodrich et al., 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Khazaezadeh, Pheasant, Bewley, Mohiddin, & Oteng‐Ntim, 2011; Mills, Schmied, & Dahlen, 2013; Nyman, Prebensen, & Flensner, 2010; Paul et al., 2013; Stringer, Tierney, Fox, Butterfield, & Furber, 2010; Thornton et al., 2006).

3.1. General barriers and facilitators to appropriate gestational weight gain

3.1.1. Knowledge and beliefs

Participants in every study expressed concern and demonstrated great motivation to improve the health of their future child. This concern for fetal well‐being was described as the main motivation to make lifestyle changes in pregnancy (Arden et al., 2014; Edvardsson et al., 2011; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Kearney, 2009; Groth et al., 2012; Harper & Rail, 2012; Mills et al., 2013; Olander et al., 2011; Thomas et al., 2014), with many finding that “the higher perceived risk to the fetus, the easier the change” (Edvardsson et al., 2011) (p.7). Unfortunately, there was typically a lack of knowledge about the risk of excess gestational weight gain to fetal health (Edvardsson et al., 2011; Furness et al., 2011; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Groth et al., 2012; Groth & Kearney, 2009; Heery et al., 2013; Huberty et al., 2010; Keely, Gunning, & Denison, 2011; Mills et al., 2013; Stengel, Kraschnewski, Hwang, Kjerulff, & Chuang, 2012). Some women expressed worry for fetal health if not enough weight was gained (Groth & Kearney, 2009; Groth et al., 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Huberty et al., 2010; Jette & Rail, 2014; Reyes et al., 2013; Tovar et al., 2010), but few participants seemed to appreciate the link between fetal health outcomes and excessive gestational weight gain (Goodrich et al., 2013; Mills et al., 2013).

Even when asked explicitly, many women did not recognize the risks of excess gestational weight gain to fetal and maternal health (Edvardsson et al., 2011; Furness et al., 2011; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Groth & Kearney, 2009; Heery et al., 2013; Huberty et al., 2010; Keely et al., 2011; Mills et al., 2013; Paul et al., 2013; Stengel et al., 2012). Some studies further elaborated that women were more focused on healthy eating and a healthy lifestyle than weight gain, feeling that lifestyle was more important than a number on a scale (Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Keely et al., 2011; Paul et al., 2013) and “weight gain should only be a concern if a woman's diet is unhealthy”(Heery et al., 2013) (pg.6) (Groth et al., 2012; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Keely et al., 2011; Olander et al., 2011; Paul et al., 2013; Weir et al., 2010). This is consistent with the UK guidelines on gestational weight gain, but was ;a view shared by many women outside of the UK.

Many authors report that women did not know what healthy weight gain in pregnancy is (Arden et al., 2014; Black et al., 2008; Furness et al., 2011; Groth & Kearney, 2009; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Nash, 2012; Olander et al., 2011; Stengel et al., 2012; Tovar et al., 2010; Vallianatos et al., 2006), or reported targeted ranges significantly higher or lower than clinical guidelines used in their country (Arden et al., 2014; Goodrich et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Lindhardt, Rubak, Mogensen, Lamont, & Joergensen, 2013; Stengel et al., 2012; Tovar et al., 2010). Women who gained excessively were more likely to report not knowing how much they should gain, or to cite a figure higher than the guidelines (Black et al., 2008; Tovar et al., 2010; Vallianatos et al., 2006).

3.1.2. Role of health care professionals

Health care professionals play an important role providing information and support for healthy gestational weight gain, and the barriers and facilitators related to interacting with health professionals are relevant to knowledge, emotions, and social factors. Many women identified that they felt feelings of blame, guilt, and humiliation when health professionals discussed weight or weight‐related matters (Arden et al., 2014; Furber & McGowan, 2011; Harper & Rail, 2012; Keenan & Stapleton, 2010; Lindhardt et al., 2013; Mills et al., 2013; Nash, 2012; Nyman et al., 2010). These feelings sometimes reflected the woman's fear of judgment or cruel treatment and sometimes were the result of past insensitive comments from health care professionals, which women said made them less likely to trust the professional, and less invested in following that person's advice or instructions about weight (Arden et al., 2014; Furness et al., 2011; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Keely et al., 2011; Keenan & Stapleton, 2010; Nash, 2012; Nyman et al., 2010). This finding applied most commonly to women who were classified as overweight or obese before pregnancy. The sensitivity of discussing weight may contribute to the common finding that health professionals were unlikely to discuss weight consistently, with many women reporting that conversations about weight were contradictory, inconsistent, or absent (Arden et al., 2014; Duthie, Drew, & Flynn, 2013; Evenson, Moos, Carrier, & Siega‐Riz, 2009; Furness et al., 2011; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Huberty et al., 2010; Lindhardt et al., 2013; Mills et al., 2013; Nash, 2012; Stengel et al., 2012; Tovar et al., 2010; Weir et al., 2010).

The absence of clear, consistent messages about healthy weight gain was a huge barrier to limiting excess weight gain. Women interpreted this inconsistent messaging to mean that weight was not important, that she as an individual did not have an issue, and that the health professional would raise the topic if there was a problem (Arden et al., 2014; Duthie et al., 2013; Edvardsson et al., 2011; Furness et al., 2011; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Huberty et al., 2010; Jette & Rail, 2014; Lindhardt et al., 2013; Mills et al., 2013; Nash, 2012; Olander et al., 2011; Stengel et al., 2012; Tovar et al., 2010; Weir et al., 2010).

3.2. Healthy eating

3.2.1. Facilitators

The health of the fetus was the most commonly mentioned motivation to improve eating habits (Edvardsson et al., 2011; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Kearney, 2009; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Groth et al., 2012; Harper & Rail, 2012; Jette & Rail, 2014; Mills et al., 2013; Olander et al., 2011; Paul et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2014; Weir et al., 2010). Women were also motivated to improve their diet in order to prevent excess weight gain for aesthetic reasons, to facilitate postpartum weight loss, and to avoid diabetes, heart disease, and other negative maternal health outcomes (Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Kearney, 2009; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Groth et al., 2012; Herring et al., 2012a; Jette & Rail, 2014; Nash, 2012; Reyes et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2014; Thornton et al., 2006; Tovar et al., 2010; Vallianatos et al., 2006).

In some circumstances, family and friends strongly motivated women to control their weight gain. Sometimes, this was through negative comments about the woman's appearance (Thornton et al., 2006; Tovar et al., 2010), and sometimes through positive support such as procuring and preparing healthy food for the pregnant woman (Black et al., 2008; Evenson et al., 2009; Furness et al., 2011; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Krans & Chang, 2011; Thornton et al., 2006). Other facilitators included affordable, conveniently available healthy food, including traditional cultural foods (Goodrich et al., 2013; Paul et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Vallianatos et al., 2006).

3.2.2. Barriers

3.2.2.1. Physical barriers

Barriers to healthy eating encompassed all aspects of a woman's life. Physically, many women described nausea, aversions, and cravings for fattening food as barriers to healthy eating (Arden et al., 2014; Black et al., 2008; Furness et al., 2011; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Paul et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Wennberg et al., 2013; Olander et al., 2011; Tovar et al., 2010). Cravings were understood by some authors as a strategy women used to indulge in unhealthy but enjoyable foods (Furness et al., 2011; Groth & Kearney, 2009; Groth et al., 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Olander et al., 2011; Paul et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006). Cravings are described by some women as impossible to resist, but also as a way to listen to their bodies and to meet their baby's nutritional needs (Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Reyes et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006).

3.2.2.2. Knowledge and beliefs

The idea of cravings as an excuse to indulge is closely related to the widespread belief that pregnancy is a time when one is supposed to gain weight, and pregnant women are allowed to indulge in appealing foods as they enjoy “a break from dieting and weight monitoring regimes … a time of more positive body image and an albeit temporary reprieve from negative comments/gaze” (Keenan & Stapleton, 2010) (Furness et al., 2011; Groth & Kearney, 2009; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Groth et al., 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Keenan & Stapleton, 2010; Nyman et al., 2010; Olander & Atkinson, 2013; Olander et al., 2011; Paul et al., 2013; Weir et al., 2010; Thornton et al., 2006).

There were many knowledge and information barriers related to nutrition, including women who did not understand how to operationalize vague directives to “eat healthy” and women who lack basic cooking skills (Arden et al., 2014; Furness et al., 2011; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Reyes et al., 2013). Nutritional information received at healthcare appointments was described as confusing and constantly changing (Ferrari, Siega‐Riz, Evenson, Moos, & Carrier, 2013; Furness et al., 2011; Stringer et al., 2010; Tovar et al., 2010; Wennberg et al., 2013), not culturally relevant (Garnweidner et al., 2013; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Krans & Chang, 2011; Paul et al., 2013), overwhelming (Ferrari et al., 2013; Furness et al., 2011; Garnweidner et al., 2013) , or absent altogether (Duthie et al., 2013; Furness et al., 2011; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Heery et al., 2013; Jette & Rail, 2014; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Stringer et al., 2010; Wennberg et al., 2013). When nutritional advice was received, it rarely accommodated structural constraints of individual circumstances such as financial hardship or lack of transportation and limited availability of fresh food (Black et al., 2008; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Jette & Rail, 2014; Paul et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2014; Thornton et al., 2006; Vallianatos et al., 2006).

3.2.2.3. Logistics

Women described other practical and logistic constraints, including lack of time for cooking and shopping and limited access to healthy food for transportation reasons (Black et al., 2008; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Heery et al., 2013; Jette & Rail, 2014; Paul et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2014; Thornton et al., 2006; Tovar et al., 2010; Vallianatos et al., 2006). For women struggling against these constraints, the easy availability of fast food and junk food was a major barrier to healthy eating (Black et al., 2008; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Kearney, 2009; Paul et al., 2013; Tovar et al., 2010; Vallianatos et al., 2006). As described by one author, “planning and preparation of healthy meals was labor‐intensive, time‐consuming and expensive and it was simply easier to resort to store‐bought food” (Vallianatos et al., 2006) (p.115). Many authors also emphasized the pleasure associated with fast food, restaurants, and unhealthy food, perhaps particularly important at a time when women might be experiencing stress and focusing their self‐discipline on other areas (e.g., foregoing alcohol and cigarettes) (Heery et al., 2013; Paul et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2014; Tovar et al., 2010; Wennberg et al., 2013).

3.2.2.4. Social barriers

The food preferences of family members were often a main determinant of the type of food that was purchased, prepared, and consumed in the home. This barrier was more acute in households where financial resources were strained (Black et al., 2008; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Paul et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Tovar et al., 2010). Some women reported pressure from family members to gain weight, overeat, or eat unhealthily (Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Groth et al., 2012; Herring et al., 2012a; Paul et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2013; Tovar et al., 2010). This behavior from family members often coincided with a belief that weight gain was important for a healthy baby, that big babies are healthy babies (Groth & Kearney, 2009; Groth et al., 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Huberty et al., 2010; Jette & Rail, 2014; Reyes et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Tovar et al., 2010), and that pregnant women should be “eating for two”(Black et al., 2008; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Jette & Rail, 2014; Paul et al., 2013; Tovar et al., 2010). Women may favor the advice of friends because social pressure makes this advice difficult to resist, (Garnweidner et al., 2013) or because they do not trust health professionals (Arden et al., 2014; Evenson et al., 2009; Ferrari et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Mills et al., 2013).

3.3. Physical activity

3.3.1. Facilitators

Women were motivated to engage in physical activity in order to feel good, have an easier labor, improve their own health and the health of their fetus, limit gestational weight gain and facilitate post‐partum weight loss, and to maintain their existing quality of life and level of physical functioning (Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth et al., 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Krans & Chang, 2011; Paul et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Vallianatos et al., 2006; Weir et al., 2010)(Groth et al., 2012; Harper & Rail, 2012; Vallianatos et al., 2006). Verbal and instrumental support from another person was also highly motivating (Black et al., 2008; Evenson et al., 2009; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Thornton et al., 2006). Exercise was more likely to happen when a woman was already active before pregnancy, had access to safe places to exercise, and found ways to include movement in her everyday routine such as walking, doing household chores, being active with children (Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Paul et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Vallianatos et al., 2006; Weir et al., 2010).

3.3.2. Barriers

3.3.2.1. Knowledge

Knowledge about physical activity was identified by several authors as a barrier. For example, many women identified a perception that exercise could harm the fetus, that pregnancy is a time for rest, that the activities of daily life are enough physical activity during pregnancy, or that very gentle exercise (e.g., walking and stretching) is all that is needed (Evenson et al., 2009; Ferrari et al., 2013; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Heery et al., 2013; Jette & Rail, 2014; Paul et al., 2013; Stengel et al., 2012; Weir et al., 2010). Women who perceived aerobic exercise to be unnecessary in pregnancy were likely to indicate that their health care providers did not discuss exercise in pregnancy and they were not aware of appropriate exercises for pregnancy (Arden et al., 2014; Duthie et al., 2013; Evenson et al., 2009; Ferrari et al., 2013; Furness et al., 2011; Goodrich et al., 2013; Heery et al., 2013; Krans & Chang, 2011; Stengel et al., 2012; Stringer et al., 2010; Weir et al., 2010). Stengel identifies a common barrier: “Women were advised to be cautious and limit their exercise during pregnancy – Among the 14 (out of 24) women who did discuss exercise during pregnancy with their providers, the focus of the providers' counselling was on being cautious about exercise” (pg.6). This lack of advice or over cautious advice about exercise stymied the efforts of women who were motivated to exercise (Goodrich et al., 2013; Krans & Chang, 2011; Weir et al., 2010).

3.3.2.2. Other barriers: logistical, physical, structural, and social

Other major barriers to physical activity include logistical factors such as poor weather (Black et al., 2008; Evenson et al., 2009; Vallianatos et al., 2006; Weir et al., 2010), lack of time due to work, childcare responsibilities and household chores (Arden et al., 2014; Black et al., 2008; Evenson et al., 2009; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Jette & Rail, 2014; Krans & Chang, 2011; Olander & Atkinson, 2013; Reyes et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Tovar et al., 2010; Vallianatos et al., 2006); physical factors such as fatigue (Arden et al., 2014; Evenson et al., 2009; Ferrari et al., 2013; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Jette & Rail, 2014; Krans & Chang, 2011; Paul et al., 2013; Weir et al., 2010), nausea or heartburn, and pregnancy‐related pain, shortness of breath and limitation of mobility (Evenson et al., 2009; Goodrich et al., 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Krans & Chang, 2011; Olander & Atkinson, 2013; Paul et al., 2013; Weir et al., 2010); structural factors such as a lack of safe, accessible places to exercise (Black et al., 2008; Evenson et al., 2009; Krans & Chang, 2011; Weir et al., 2010), and the cost of exercise (transportation, equipment, and programs) (Evenson et al., 2009; Krans & Chang, 2011; Thomas et al., 2014; Thornton et al., 2006; Vallianatos et al., 2006; Weir et al., 2010). Women also mentioned social barriers to exercise, such as family members who restricted a woman's level of physical activity, either out of concern that exercise may harm the fetus, or because they were trying to help by relieving her of household tasks (Black et al., 2008; Evenson et al., 2009; Ferrari et al., 2013; Goodrich et al., 2013; Groth & Morrison‐Beedy, 2013; Heery et al., 2013; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Thornton et al., 2006; Weir et al., 2010). Women who were overweight or obese before pregnancy might avoid exercise because of embarrassment or stigma (Furber & McGowan, 2011; Furness et al., 2011; Krans & Chang, 2011; Weir et al., 2010).

3.4. Acceptable and appropriate strategies for intervention

Women identified a wide variety of factors that would increase the acceptability and appropriateness of intervention strategies to prevent excess gestational weight gain. Pregnancy was widely recognized as a time to make positive lifestyle changes, so women consider lifestyle interventions during pregnancy to be appropriate and more helpful than post‐partum interventions (Harper & Rail, 2012; Weir et al., 2010).

3.4.1. Healthy eating

Regarding improved nutrition and eating habits, women identified increasing access to healthy, fresh, and affordable food close to home as a facilitator of healthy eating (Goodrich et al., 2013; Krans & Chang, 2011; Paul et al., 2013). Group‐based cooking classes and nutritional education sessions were mentioned as a way to increase motivation and social support (Evenson et al., 2009; Ferrari et al., 2013; Furness et al., 2011; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Krans & Chang, 2011; Olander, Atkinson, Edmunds, & French, 2012; Smith, Ward, Forbes, Reynolds, & Denison, 2013; Thomas et al., 2014; Vallianatos et al., 2006). Learning from peers, especially women with multiple children, was cited as a way to increase social connection while gaining practical tips about how to cook quick, inexpensive, healthy meals (Furness et al., 2011; Hearn, Miller, & Fletcher, 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Olander et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Vallianatos et al., 2006). Strategies to eat healthy throughout the day were important, such as packing a lunch, or learning how to decrease impulse food decisions through planning ahead (Paul et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2013). The ability to individualize nutritional advice to incorporate allergies, preferences, and traditional foods was also appreciated (Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Vallianatos et al., 2006).

3.4.2. Physical activity

Regarding exercise, women identified a need for accessible and safe places to exercise (Black et al., 2008; Evenson et al., 2009; Furness et al., 2011; Goodrich et al., 2013; Vallianatos et al., 2006), and financial assistance to access these programs (Krans & Chang, 2011; Paul et al., 2013). Women with children desired exercise opportunities that do not require additional time away from family or the need for childcare (Evenson et al., 2009; Olander et al., 2011; Vallianatos et al., 2006). This includes strategies to fit physical activity into a woman's everyday routine, exercise opportunities during break times at work, or physical activities that children and other family members can participate in (Groth et al., 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Vallianatos et al., 2006; Weir et al., 2010). Several papers mentioned the acceptability of exercise classes geared to pregnant women, as participants could be sure that the exercise was safe for pregnancy and make motivating social connections with peers (Evenson et al., 2009; Ferrari et al., 2013; Furness et al., 2011; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Krans & Chang, 2011; Olander et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2014; Vallianatos et al., 2006). These social connections are an important form of external motivation for initiating and maintaining an exercise routine (Black et al., 2008; Evenson et al., 2009; Goodrich et al., 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Thornton et al., 2006) .

3.4.3. Acceptable strategies for receiving information

Women want clear, timely, credible, and evidence‐based information and see health professionals as well positioned to provide that information (Ferrari et al., 2013; Hearn et al., 2013; Hearn, Miller, & Lester, 2014; Jette & Rail, 2014; Olander et al., 2012; Stengel et al., 2012; Weir et al., 2010), particularly when a trusting relationship exists with that clinician (Furness et al., 2011; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Mills et al., 2013; Nyman et al., 2010; Stringer et al., 2010). Women wished that their health care professionals would proactively offer sensitive, nonjudgmental counselling about weight gain, nutrition, physical activity, and associated health outcomes (Arden et al., 2014; Duthie et al., 2013; Ferrari et al., 2013; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Huberty et al., 2010; Jette & Rail, 2014; Keenan & Stapleton, 2010; Mills et al., 2013; Stengel et al., 2012; Tovar et al., 2010; Herring et al., 2012a; Heery et al., 2013; Olander et al., 2011; Thomas et al., 2014). Individualized counselling about diet and weight management would help women apply this information to their personal circumstances (Arden et al., 2014; Ferrari et al., 2013; Garnweidner et al., 2013; Hearn et al., 2013; Mills et al., 2013; Stengel et al., 2012; Tovar et al., 2010). Psychological support was an important aspect of effective counselling mentioned by women who were overweight prior to pregnancy (Khazaezadeh et al., 2011; Thomas et al., 2014).

Educational support resources are considered acceptable if they supplement other strategies and are not the sole source of information (Ferrari et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011). Information is most desirable when it is received early in pregnancy (Garnweidner et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Olander et al., 2012; Stringer et al., 2010), is communicated in an interactive format (Hearn et al., 2013; Hearn et al., 2014; Khazaezadeh et al., 2011), conveys practical strategies and tips (Arden et al., 2014; Furness et al., 2011; Goodrich et al., 2013; Olander et al., 2011; Stengel et al., 2012), and depicts women like them—of all races and body sizes (Smith et al., 2013). Online or text‐message information was acceptable as long as it was from a trustworthy, authoritative source (Hearn et al., 2013; Hearn et al., 2014; Olander et al., 2012; Reyes et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2013; Stringer et al., 2010). Given the importance of social support from family members, educational programs aimed at a woman's spouse and family could help those individuals understand the importance of assisting the pregnant woman achieve a healthy level of weight gain (Black et al., 2008; Goodrich et al., 2013; Harper & Rail, 2012; Heery et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2012a; Krans & Chang, 2011; Reyes et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2013; Thornton et al., 2006; Tovar et al., 2010).

4. DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate significant consistency in the way women emphasize the importance of social location and resources (e.g., family situation, neighborhood, and financial resources) when they describe their perceptions of the factors (barriers and facilitators) that lead to gestational weight gain. Many of these barriers highlight the relationship between weight and a woman's social environment, helping to explain the wealth of literature that has identified an association between low socioeconomic status and higher rates of gestational weight gain (Mujahid et al., 2005; Manios et al., 2005; Kowal, Kuk, & Tamim, 2012). For instance, participants identified low income as a barrier to appropriate gestational weight gain because of the difficulty affording fresh food, residence in a neighborhood where fresh food is not easily available, and lack of affordability of exercise programs or resources. The importance of socio‐environmental determinants of weight gain is evident not just in the social and structural categories of our findings, but in nearly all categories. For example, many logistical problems (e.g. lack of time for food shopping, lack of childcare, weather prohibitive to exercise) can be exacerbated or eased through the availability of social, environmental, and financial resources. Similarly, the education and information available to the pregnant woman and her friends and family is influenced by the social environment, including literacy levels, access to nutrition information and education, ease of discussion with health professionals, and ability to understand and operationalize information (Ball & Crawford, 2006; Campbell et al., 2016). Emotional barriers such as stress, anxiety, and depression have been found to be higher in people living in poverty or material deprivation (Ritter, Hobfoll, Lavin, Cameron, & Hulsizer, 2000; Santiago, Wadsworth, & Stump, 2011; Ennis, Hobfoll, & Schröder, 2000).

These findings emphasize the socially embedded nature of weight gain; while diet and physical activity choices are made by the individual, these choices are made within the social context of the individual's life (Bennett et al., 2008). This is well documented in the epidemiological literature on obesity, which demonstrates that higher weight is socially distributed, and disproportionately prevalent in particular groups, for example, among women with low income and low education levels (Mujahid et al., 2005; Manios et al., 2005; Kowal et al., 2012).

Given that weight gain is closely associated with social and environmental disadvantage, it is insufficient and unethical to target weight gain interventions at individual choice alone: “those most vulnerable to obesity as it is framed in health and public health are the least able to rectify it. Individualization of responsibility is thus an ethically bad idea: it burdens the already burdened” (Reiheld, 2015 pg 239). This caution is particularly relevant to those working with socially marginalized women, as our analysis shows they may face multiple socio‐environmental barriers to healthy weight gain and have fewer resources to mitigate these challenges. For example, family preferences were identified as the main determinant of food purchased and consumed at home, with several authors identifying that this barrier was more acute when financial resources were limited and had to be stretched to accommodate as many people as possible—extra money and time was not available to buy special food for the pregnant woman that other family members would or could not eat. The public health concern with maternal weight gain is analogous to the concern with breastfeeding rates (Centers for Disease Control, 2013). Both are backed by strong evidence that they have important biological and physiological health outcomes for both mothers and infants. Both are framed in public discourse as matters of maternal choice, overlooking the role of social environments in which those choices are made (Kukla, 2006; De Brún, McCarthy, McKenzie, & McGloin, 2013). As Kukla (2006) has written, focusing on maternal responsibility fails to address “how maternal duties and responsibilities for health care intersect with social and environmental determinants of child health, such as race, income, and social support networks” (Kukla, 2006 pg.158). Our synthesis finds that women feel a personal responsibility to do whatever they can to improve the health of their child, but that they make these efforts within social environments that may make healthy choices very difficult. The World Health Organization provides an example of a strategy that ethical public health campaigns about maternal weight gain might emulate, recognizing that weight gain is a social and environmental disease, and focusing less on individual responsibility and more on “making healthy choices easy choices” (World Health Organization, 2014) by addressing environmental, systemic, policy, and social factors that stymie individual choices around healthy weight.

Women's suggestions for acceptable interventions highlight the need for interventions that target broader factors influencing excess weight gain. Beyond education, women in the studies we synthesized request interventions that promote social support, include childcare, and accommodate the structures of their busy lives. They require improved access to fresh, healthy foods through lowered financial, distance, and transportation barriers. Beyond access to healthy food, women desire culturally appropriate nutritional information and community‐based opportunities to learn ways to prepare food that is nutritious in a quick and simple way. Above all, women emphasize the importance of including family members as active partners in meal planning, preparation, and physical activity. These findings were reinforced in a recent study of women participating in a free community‐based, group intervention to encourage healthy gestational weight gain (Harden et al., 2014).

These suggestions relate to social and structural inequities, which are important but difficult to change as they transcend public health programs and patient–health care provider relationships. Health care providers who wish to take action to help their pregnant patients achieve optimal levels of gestational weight gain might focus on the findings related to the patient–clinician relationship. Women in these studies emphasized the importance of a mutually respectful and trusting relationship with their health care provider. They hoped that their health care provider would alert them to potential issues related to weight, and be able to provide individualized, practical advice about healthy weight gain through nutrition and physical activity. This practical advice might include strategies to divert cravings for junk food, recipes for healthy food that can be quickly, for a low cost, and techniques to cope with stress, depression, and other negative emotions that may lead to emotional eating. Referrals to authoritative educational or informational sources would be welcome, so long as they are a supplement and not a replacement for clinician counselling. Recent trials that have taken this approach have demonstrated success. For instance, home visits from a “healthy weight advisor” who provided individualized, practical advice and support were rated very highly by obese pregnant women (Atkinson, Olander, & French, 2016). It is important that clinicians understand that supportive, individualized counselling can affect change; a recent review concluded that when clinicians do not believe they can make a difference in women's behavior, they are less motivated to offer information and support (Heslehurst et al., 2014).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This study provides a comprehensive synthesis of qualitative evidence about women's understandings of excess gestational weight gain, the first that we know of. The 42 studies represent over a thousand women's perceptions and experiences, allowing for strong consistency across themes and categories. Our findings reflect what has been reported in the literature, and some emerging topics in other types of literature may be absent, for example, intrapersonal, psychological determinants of gestational weight gain (Skouteris et al., 2010; Kapadia et al., 2015). Because few authors consistently sampled by or reported gestational age of their participants, we are not able to compare our findings to stage of pregnancy, which has been indicated by others to be a significant factor of women's perceptions about gestational weight gain (Park et al., 2015; McDonald et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2016).

Because the review focused only on high‐income nations, findings may not be transferable to low‐ and middle‐income countries. Additionally, gestational weight gain guidelines differ across nations. This synthesis included data from seven countries, six of which endorse the gestational weight gain guidelines published by the American Institutes of Medicine; one included country, the United Kingdom, provides no specific weight gain targets. Additionally, the IOM guidelines changed in 2009, with other national guidelines following suit 2010–2012. Our systematic review included studies published as early as 2005. The differences in clinical practice guidelines may affect the way that clinicians discuss gestational weight gain and the understanding that women had about optimal weight gain.

5. CONCLUSION

Excess gestational weight gain can have many negative health outcomes for women and infants. As a result, there is significant public health interest in promoting healthy weight gain during pregnancy. Despite this interest, excess gestational weight gain is becoming more common, and effective interventions are lacking. This study synthesized 42 published qualitative research studies on women's perspectives and understandings about weight gain in pregnancy. Effective and sensitive healthy weight gain interventions will recognize the social environment in which decisions about weight take place, and make efforts to ensure that healthy choices are easy choices.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

This work was funded by the Government of Ontario. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be taken to represent the views of the Government of Ontario. S. D. M. is supported by a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Maternal and Infant Obesity Prevention and Intervention.

CONTRIBUTIONS

This study was designed by MV, MG, DD, and SDM. Data collection was performed by MV, SK, and DD with input from MG and SDM when consensus was needed. All authors contributed to analysis. The draft was written by MV with assistance from SK. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Toronto Public Health's Healthiest Babies Possible Program in the development of the research question. We acknowledge the assistance of Jaya Raghubir in sorting references.

Vanstone M, Kandasamy S, Giacomini M, DeJean D, McDonald SD. Pregnant women's perceptions of gestational weight gain: A systematic review and meta‐synthesis of qualitative research. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13:e12374 10.1111/mcn.12374

REFERENCES

- Alavi, N. , Haley, S. , Chow, K. , & McDonald, S. (2013). Comparison of national gestational weight gain guidelines and energy intake recommendations. Obesity Reviews, 14, 68–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antecol, H. , & Bedard, K. (2006). Unhealthy assimilation: why do immigrants converge to American health status levels? Demography, 43, 337–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arden, M. A. , Duxbury, A. M. S. , & Soltani, H. (2014). Responses to gestational weight management guidance: A thematic analysis of comments made by women in online parenting forums. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, L. , Olander, E. K. , & French, D. P. (2016). Acceptability of a weight management intervention for pregnant and postpartum women with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2: A qualitative evaluation of an individualized, home‐based service. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20, 88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council (2012). Clinical practice guidelines: Antenatal care‐ module 2. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, K. , & Crawford, D. (2006). Socio‐economic factors in obesity: A case of slim chance in a fat world? Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 15, 15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett‐Page, E. , & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, 59, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, G. G. , Wolin, K. Y. , & Duncan, D. T. (2008). Social determinants of obesity (pp. 342–376). Methods and Applications: Obesity Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- Black, T. L. , Raine, K. , & Willows, N. D. (2008). Understanding prenatal weight gain in First Nations women. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 32, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, E. E. , Dworatzek, P. D. , Penava, D. , de Vrijer, B. , Gilliland, J. , Matthews, J. I. , Seabrook, J. A. (2016). Factors that influence excessive gestational weight gain: Moving beyond assessment and counselling. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedergren, M. (2006). Effects of gestational weight gain and body mass index on obstetric outcome in Sweden. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 93, 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]