Abstract

Identifying modifiable risk factor for exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) interruption is key for improving child health globally. There is no consensus about the effect of pacifier use on EBF interruption. Thus, the aim of this systematic review was to investigate the association between pacifier use and EBF interruption during the first six month. A search of CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science, LILACS and Medline; from inception through 30 December 2014 without restriction of language yielded 1,866 publications (PROSPERO protocol CRD42014014527). Predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria peer reviewed yielded 46 studies: two clinical trials, 20 longitudinal, and 24 cross‐sectional studies. Meta‐analysis was performed and meta‐regression explored heterogeneity across studies. The pooled effect of the association between pacifier use and EBF interruption was 2.48 OR (95% CI = 2.16–2.85). Heterogeneity was explained by the study design (40.2%), followed by differences in the measurement and categorization of pacifier use, the methodological quality of the studies and the socio‐economic context. Two RCT's with very limited external validity found a null association, but 44 observational studies, including 20 prospective cohort studies, did find a consistent association between pacifier use and risk of EBF interruption (OR = 2.28; 95% CI = 1.78–2.93). Our findings support the current WHO recommendation on pacifier use as it focuses on the risk of poor breastfeeding outcomes as a result of pacifier use. Future studies that take into account the risks and benefits of pacifier use are needed to clarify this recommendation.

Keywords: exclusive breastfeeding, meta‐analysis, meta‐regression, pacifiers, risk factors, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

The recommendation of the World Health Organization (WHO) is that exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) should be practiced until the sixth month of life of the infant because it prevents child mortality and promotes quality of life in the short and long‐term (Victora, Aluísio, Barros, França, et al., 2016; Grummer‐Strawn & Rollins, 2015; Sankar et al., 2015; Horta, Loret de Mola, & Victora, 2015; Lodge et al., 2015; Peres, Cascaes, Nascimento, & Victora, 2015; Horta, Bahl, Martines, & Victora, 2013). Unfortunately, EBF duration remains substantially lower around the world (Labbok, Wardlaw, Blanc, Clark, & Terreri, 2006; Cai, Wardlaw, & Brown, 2012; Victora et al., 2016) making the identification of modifiable risk factors for lack of EBF a high priority.

Key Messages

Pacifier use may be a risk factor for the premature interruption of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF). Mothers should be advised about this hazard.

Mothers should be taught techniques to soothe their babies that do not involve the use of pacifiers

Well‐designed prospective cohort studies in diverse socio‐economic and cultural settings are needed to rule out the possibility that pacifier use is simply a marker of either breastfeeding difficulties or maternal motivation to EBF interruption.

Qualitative studies are needed to gain an in‐depth understanding of the reasons behind the introduction of pacifier use in diverse populations.

Pacifier use recommendations need to be based on a benefit–risk approach focusing on the trade‐off between pacifier‐related breastfeeding outcomes and SIDS.

Pacifier use has been identified as a factor associated with shorter duration of EBF in observational studies (Vogel, Hutchison, & Mitchell, 2001; Hörnell, Aarts, Kylberg, Hofvander, & Gebre‐Medhin, 1999; Victora, Behague, Barros, Olinto, & Weiderpass, 1997). A recent cross‐sectional analysis conducted with data from two Brazilian surveys showed that pacifier use was inversely associated with EBF rates with this association remaining stable across time (Buccini, Perez‐Escamilla, & Venancio, 2016). However, because of potential confounding it is unknown if this relationship is indeed causal (Fein, 2009; Cunha, Leite, & Machado, 2009). While researchers have suggested that pacifier use might interfere with the establishment breastfeeding (Neifert, Lawrence, & Seacat, 1995; Righard, 1998; Kronborg & Vaeth, 2009) others have suggested that pacifier use is simply a marker of breastfeeding problems (Victora et al., 1997; Kramer et al., 2001). Consequently, the recommendations for pacifier use vary worldwide (Eidelman et al., 2012; Sexton & Natale, 2009; World Health Organization [WHO], 2008; Canadian Paediatric Society Community Paediatrics Committee, 2003). WHO strongly discourages the use of pacifiers in breastfed children (World Health Organization [WHO], 2008), with this recommendation being one of the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding upon which the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative is based (Perez‐Escamilla, Martinez, & Segura‐Perez, 2016; Passanha, Benicio, Venancio, & Reis, 2015; DiGirolamo, Grummer‐Strawn, & Fein, 2008). On the other hand, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends using pacifiers to prevent sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and there is a general recommendation that pacifiers can be introduced after breastfeeding is well established, at approximately 3 to 4 weeks of age (Eidelman et al., 2012). Accordingly, it has been a challenge for health professionals and parents to have a clear understanding of what to recommend or do in different contexts (e.g., a newborn at high risk of SIDS vs. a mom who is very concerned about following practices that may interfere with EBF).

Systematic reviews (O'Connor, Tanabe, Siadaty, & Hauck, 2009; Santos Neto, Oliveira, Zandonade, & Molina, 2008) and meta‐analyzes (Jaafar, Jahanfar, Angolkar, & Ho, 2012; Karabulut, Yalçin, Ozdemir‐Geyik, & Karaağaoğlu, 2009) examining the relationship between pacifier use and breastfeeding outcomes have found conflicting results. While reviews based on observational studies have concluded that pacifier use is a risk factor for a reduction in EBF duration (Santos Neto et al., 2008; Karabulut et al., 2009), those that have focused only on RCTs have reported no differences on the duration of EBF as a result of pacifier's interventions (O'Connor et al. 2009; Jaafar et al., 2012). Furthermore, the search and selection criteria used vary greatly across reviews, that is, very strict inclusion criteria leading to the inclusion of just two studies (Jaffar et al. 2012), date restriction (Santos Neto et al., 2008; O'Connor et al., 2009) or language restriction (O'Connor et al., 2009; Karabulut et al., 2009). These methodological variations across reviews call for a more comprehensive review approach that allows for capturing the whole body of evidence. Specifically, it's important to assess both observational and experimental studies without imposing date or language restriction. New reviews in this area also need to address effect modification related to study design characteristics (e.g., observational vs. experimental design, sample size, study socio‐economic setting, outcome and exposure measures, and study quality). Therefore, in order to support clinical practice and provide evidence for policies to promote and protect breastfeeding, this study aimed to perform a comprehensive systematic literature review and meta‐analysis to investigate the association between pacifier use and EBF interruption in infants less than 6 months of life, taking into account study design heterogeneity across studies.

2. METHOD

The protocol of this systematic review was registered on the PROSPERO registry prior to starting the literature search (CRD42014014527).

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included observational and experimental studies that evaluated the association between pacifier use and EBF interruption in infants younger than 6 months.

Our systematic review and meta‐analysis followed the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2009). We excluded studies that: (a) were not quantitative including review articles (systematic or not) and letters to the editor; (b) included premature babies or newborns with congenital anomalies; (c) combined pacifiers and bottle nipples in the same category; (d) did not report a statistical parameter documenting the size of the association between pacifier use and EBF interruption and lacked data to estimate the effect size of association. In the case that a study used the same sample for data analysis in different publications, we selected the study that provided the most detail pertinent to this review.

2.2. Exposure/intervention: Pacifier use

The key exposure was pacifier use defined as use versus non‐use in infants less than 6 months of age (<6 months).

2.3. Outcomes: Interruption of exclusive breastfeeding

We combined all studies that provided information about EBF interruption during the first 6 months of life, without any further age restrictions. EBF was defined as the infant receiving only breast milk (including expressed breast milk or breast milk from a wet nurse) allowing the infant to receive oral rehydration solutions (ORS), drops, syrups (vitamins, minerals, and medicines), but nothing else (WHO 2008).

2.4. Search strategy

We searched published literature with the following databases: CINAHL, SCOPUS, Web of Science, LILACS and MEDLINE without language restrictions and from inception through 30 December 2014.

The search terms used were: pacifier use, EBF, epidemiology, cross‐sectional, cohort, case–control, and trials. Descriptors for these terms were identified in English and Portuguese from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. Each MeSH term found, as well as its synonyms and variations were applied individually in the search to test the sensitivity of each term. This information was used to finalize the search strategy that was used with each database (Table S1). After excluding the duplicates, additional manual searches of the references' lists of the systematic reviews identified (Jaafar et al., 2012; O'Connor et al., 2009; Karabulut et al., 2009; Santos Neto et al., 2008) were performed to identify papers that might fulfill the inclusion criteria and that were not identified in the electronic databases.

2.5. Study selection

Three review authors (GSB, LMP, and CLA) that were previously standardized against each other (Kappa = agreement of 90%); screened the titles and abstracts independently to identify potentially relevant citations. The full texts of all potentially relevant articles were retrieve and independently assessed for eligibility using the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria defined above. Any disagreements were solved through a consensus process and, if necessary, by consulting the fourth reviewer with expertise in the area (SIV).

2.6. Assessment of study characteristics and data extraction

The information extracted from each study using a standardized protocol included: study reference (author/year of publication); country/year of study; study design, study quality score; sample size; study outcome (EBF interruption); classification and measurement of exposure (pacifier use), prevalence of EBF interruption; prevalence of pacifier use; OR effect size measure with respective 95% confidence interval (adjusted or crude).

We also identified the covariates included in adjusted models across studies. We quantified how many times each covariate was adjusted for and how many times it was significantly associated with EBF interruption across applicable studies. Then covariates were grouped into the following categories: (a) Mother and family characteristics; (b) Pregnancy and childbirth factors; (c) infant characteristics; (d) breastfeeding technique and family support; (e) breastfeeding assistance. This information was used to identify which covariates are more likely to mediate the relationship between pacifier use and EBF interruption. Table 1 shows the list of specific covariates by group category.

Table 1.

Covariates identified in adjusted models across studies of association between pacifier use on the interruption of EBF

| Category group (number of covariates) | Covariates |

|---|---|

| (a) Mother and family characteristics (n = 18) | Maternal education; maternal age; mother's occupation or job status; maternal race; maternal emotional distress; parity, had a child under 5 years; mother's BMI; maternal smoking habits or alcohol use; maternal marital status; father's age; working status or occupation of father; father's education; father smoking habits; area of residence; infant stay at the daycare; family income, social class; cohabitation with maternal/paternal grandmother; maternal oral contraceptive use. |

| (b) Pregnancy and childbirth factors (n = 6) | Type of delivery, cesarean planned; multiple births; if the pregnancy was planned; number of prenatal visits; quality of prenatal care; gestational age when mother started prenatal care. |

| (b) Infant characteristics (n = 7) | Infant's age; birth weight; sex of the baby; baby's behavior to feed; baby needed special care/ICU or hospitalization in the first months; weight gain during the follow‐up; gestational age at birth or prematurity. |

| (c) Breastfeeding technique and family support (n = 11) | Limiting the number of feedings at night/Breastfeeding during the night/ child sleeps more than six hours; use of formula (after hospital discharge); presence of nipple cracked; breastfeeding technique (maternal complaint/latch/positioning); maternal prior intention to breastfeed, maternal review of the optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding, length time of maternal decision on how to feed the child; breastfeeding pre‐established schedules; father's support and/or family's support; maternal grandmother did not have breastfed, mother did not breast fed, feeding preference of the grandmother; introduction of solid foods; Mother have plenty of milk supply; bed shared or sleep separately from parents; knowledge or prior experience with breastfeeding; pacifier use after the second week of life |

| (d) Breastfeeding assistance (n = 13) | Birth in Baby‐Friendly Hospital; rooming in; pacifier use in the hospital; use formula, supplemental or other liquid in the hospital; type of health service in follow‐up (health center with team or pediatrician trained in breastfeeding); place where gets immunization; hospital discharge of the mother and baby at different times; length of hospital stay; first feed the baby; breastfeeding in the first hour, skin‐to‐skin contact, early initiation of breastfeeding; to receive a counseling and breastfeeding management in the hospital; to receive medical visit at home, to receive nurse visit at home; conflicting guidelines for health professionals |

2.7. Quality assessment of studies

Bias risk was assessed with a modified version of the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (EPHPP) (http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html) (Armijo‐Olivo, Stiles, Hagen, Biondo, & Cummings, 2012). The following six items were classified as either “strong”, “moderate”, or “weak”: (a) selection bias; (b) study design; (c) confounding factors; (d) blinding; (e) data collection methods, and (f) withdrawals and dropouts. Blinding was assessed only in the RCTs included and follow‐up attrition did not apply to cross‐sectional studies. Regarding “study design”, cross‐sectional studies had lower initial scores than cohort studies and RCTs, due to their inherent limitations in relation to the establishment of temporality between exposure variable and the outcome. Study quality could then be upgraded or downgraded based on the internal validity of the studies. The articles were classified according to the final score of EPHPP as strong if none of the quality items were weak; moderate if one of the six items was classified as weak; and weak, for studies with more than one item identified as such.

2.8. Data analysis

2.8.1. Effect size measure

Effect measures were presented as pooled odds ratios. For studies that summarized the effect size with estimators other than ORs whenever possible, we converted the estimators to ORs as recommended by Deeks, Altman, and Bradburn (2001). For those that were not possible to convert because the necessary information was not provided, we were able to contact and receive the needed information for three studies (Warkentin, Viana, Zapana, & Taddei, 2012; Warkentin, Taddei, Viana, & Colugnati, 2013; Merten, Dratva, & Ackermann‐Liebrich, 2005). Thus, supplementary information was received that enabled the calculation of the OR. For one study, we had to use the RR as a proxy for the OR (Chaves, Lamounier, & César, 2007). Where adjusted estimators where available, they were included; otherwise, crude estimators were considered.

When studies presented two or more infant age categories for EBF interruption, the findings with the EBF measure closer to 6 months was considered for comparison in the meta‐analysis because the objective was to evaluate the outcome closer to the WHO recommendation for EBF (WHO 2008). With regards to pacifier use status, we included the findings from the earlier infant age measure based on biological plausibility considerations (Kronborg & Vaeth, 2009; Righard et al. 1998; Neifert et al., 1995) (i.e., if the study examined the association between EBF interruption with pacifier use at both 2 week and at 1 month, we included only the findings for pacifier use at 2 week).

2.8.2. Meta‐analysis

A meta‐analysis was performed by type of design of epidemiological studies (randomized clinical trial, prospective cohort, and cross‐sectional). We examined the impact of heterogeneity using a measure of the degree of inconsistency in the studies' results (I 2 statistic) and by its significance (p < 0.05) using a random‐effects model (Deeks et al., 2001). Funnel plots and Egger's test were used to evaluate the presence of publication bias (Sterne, Egger, & Smith, 2001).

Due to high heterogeneity across studies identified in the meta‐analysis (I 2 > 75%) meta‐regression was conducted (Higgins & Thompson, 2002; Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, 2003). Meta‐regression was specifically used to evaluate the contribution of study characteristics to the between‐study variability (Berkley, Hoaglin, Mosteller, & Colditz, 1995). Study characteristic tested were: Study design (RCT, longitudinal, and cross‐sectional); Sample size (≤300, 301–1000, >1000); Age of exposure measurement (pacifier) (use among infants: before the second week/hospital discharge, before sixth week, 2–4 month, under 4 or 6 month); Age of outcome measurement (EBF interruption) (among infants: hospital discharge, before the sixth week, between 2 and 4 month under 4 or 6 month); Setting (High income country/multicentric and Middle−/Low‐income country), Publication language (English, Portuguese, other), Effect size (adjusted and crude); Study quality score (Strong, Moderate, and Weak); Publication year, dichotomized into before (≤2009) and after (>2009) the publication of the previous reviews and meta‐analyses. Each methodological characteristic was included as a covariate in the meta‐regression and the percentage of heterogeneity explained by each was calculated (Sterne et al., 2001). All analyzes were conducted using Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

3. RESULTS

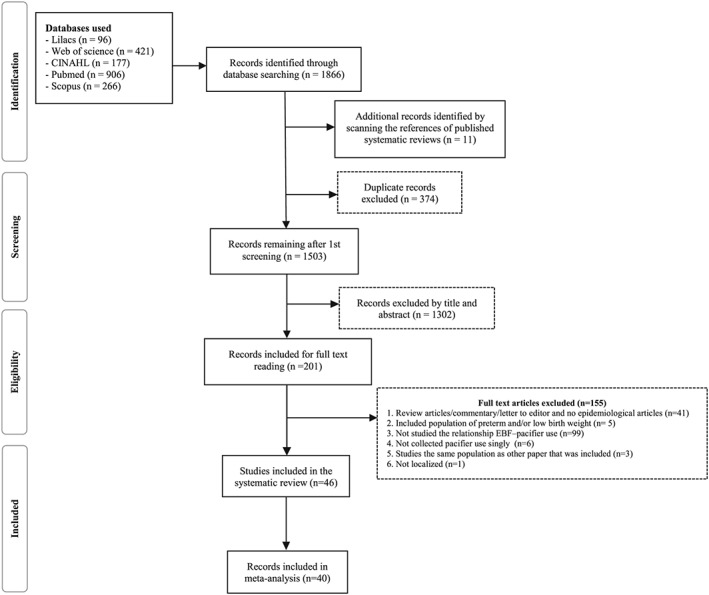

Initially, we identified 1,866 publications in the databases searched electronically, of which 374 were duplicates. The manual screening of the references of the systematic reviews identified yielded 11 additional publications. After screening the title and abstracts of the remaining 1,503 publications, 1,302 publications were excluded. Thus, a total of 201 articles were included for full text reading, and of these 155 articles were excluded resulting in the inclusion of 46 articles in the systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Pacifier use and interruption of exclusive breastfeeding

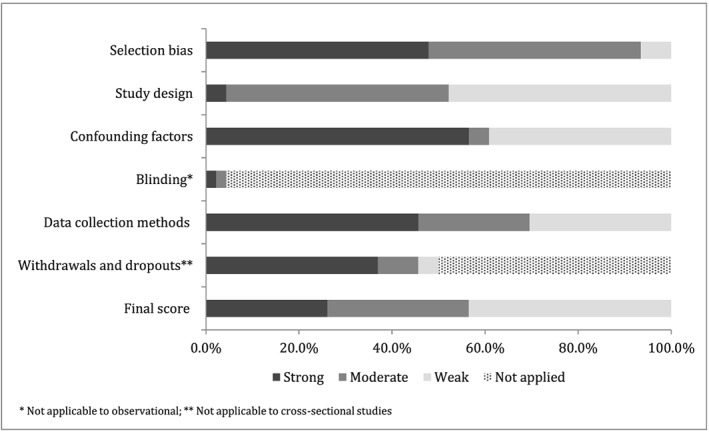

Of the 46 papers that met the inclusion criteria, 40 provided information for the meta‐analysis. Twelve studies were classified as having strong quality, 14 moderate quality and 20 weak quality. Figure 2 indicates that only 26.1% of the studies had strong quality. The quality items examine that had the more weaknesses were study design, adjusting for confounding factors, and data collection methods (Figure 2). Almost half of the observational studies used adjusted models to evaluate the association of interest. A total of 55 different covariates were adjusted for across studies (Table 1). Maternal and family characteristics were the covariates used more often in the adjusted models, especially socioeconomic factors and maternal smoking. Followed by covariates reflecting breastfeeding behaviors and intentions, including breastfeeding technique, prior experience breastfeeding and prior intention to breastfeed.

Figure 2.

Summary of the risk of bias of the studies included in the systematic review based on the checklist Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review. Most of the studies were conducted in Brazil (27 out of 46 studies) followed by Italy (3/46) and New Zealand (2/46). Pacifier use prevalence ranged from 21% (Carrascoza, Possobon Rde, Ambrosano, Costa Júnior, & Moraes, 2011) to 79.7% (Lindau et al., 2014) among children under 6 months. The highest pacifier use prevalence occurred in studies conducted in Brazil and Italy. Different classifications for pacifier use were reported, with the most common being dichotomous (use vs. non use). Other approaches to classify pacifier exposure were based on frequency of use (occasional, frequent, daily, intense, and partial) (Ford et al., 1994; Nelson et al., 2005; Aarts, Hörnell, Kylberg, Hofvander, & Gebre‐Medhin, 1999).

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review

| Author/publishing year | Country/year of study | Study design | Quality score | Sample size | Outcome (age group) | Exposure (age group) | Prevalence of EBF interruption € | Prevalence of pacifier use € | Effect size | Factors at baseline to match intervention and control groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jenik, 2009 | Argentina 2005–2006 | Randomized Clinical Trial | Strong | 1021 | EBF interruption at 4 months | Pacifier use at 4 months | 25.3% | 51.4% | OR* 1.04

(0.78–1.40) |

Birth weight(c); type of delivery(b); maternal age(a); maternal education(a); mother smoker(a); marital status (cohabiting with the father)(a); birth in BFH(e); early initiation of breastfeeding(e) | ||

| Kramer et al., 2001 | Canada 1998–1999 | Randomized Clinical Trial | Strong | 281 | EBF interruption at 3 months | Pacifier use at 3 months | 65.1% | 50.7% | RR 1.0

(0.8–1.1) OR* 1.12 (0.67–1.87) |

Mean maternal age(a); Mean maternal education(a); Mother smoking during pregnancy(a); maternal work status(a); marital status(a); Parity(a); prior experience maternal on breastfeeding(d); mean baby birth weight(c) | ||

| Effect size | Factors associated with outcome | |||||||||||

| Crude | Adjusted | Significance | Non‐ significance | |||||||||

| Lindau et al., 2014 | Italy

2000–2001 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 542 | EBF interruption at 4 months | Pacifier use before second week | 83.9% | 64.4% | OR 2.39

(1.38–4.14) |

OR 2.38

(1.35–4.20) |

Maternal emotional distress(a); type of delivery(b); attending prenatal classes(b) | Mother's age(a); mother's education(a); maternal smoking habits(a) |

| Vieira, Vieira, Oliveira, Mendes, & Giugliani, 2014, ** | Brazil

2004–2005 |

Longitudinal | Strong | 1344 | EBF interruption in the first 6 months | Pacifier use in each month | 88.7% | 44.8% | N/R | HR 1.40

(1.14–1.71) |

Mother's education(a); Maternal work status(a); number of prenatal visits(b); prenatal care in public service(b); birth in BFHI(e); breastfeeding counseling at the hospital(e); mother's partner support breastfeeding(d); limit the number of feedings at night(d); cracked nipples(d) | Ethnic group(a); mother's age(a); parity(a); previous experience with breastfeeding(d); marital status(a); normal birth; breastfeeding within 1 hour(e); baby's sex(c). |

| Carrascoza et al., 2011 | Brazil

2004 |

Longitudinal | Strong | 111 | EBF interruption at 6 months | Pacifier use in the follow‐up | 48.6% | 20.7% | N/R | OR 11.46

(3.09–42.37) |

Social class(a); maternal work status(a) | ‐ |

| Vieira, Martins, Vieira, Oliveira, & Silva, 2010 | Brazil

2004 |

Longitudinal | Weak | 1309 | EBF interruption at the end of the first month | Pacifier use at the end of the first month | 40.7% | 41.5% | OR 1.58

(1.39–1.80) |

OR 1.53

(1.34–1.76) |

Prior maternal experience with breastfeeding(d); pre‐established schedules for breastfeeding(d); cracked nipples(d) | ‐ |

| Barros et al., 2009 | Brazil

2006 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 104 | EBF interruption at 6 months | Pacifier use in the follow‐up | 91.7% | third month:

54% |

RR 0.9

(0.6–1.2) OR* 0.59 (0.12–3.07) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kronborg & Vaeth, 2009, ** | Denmark

2004 |

Longitudinal | Strong | 780 | EBF interruption between 1st and 26th week | Pacifier use during the first second week | N/R | 64.3% | HR 1.42

(1.19–1.69) |

HR 1.42

(1.18–1.72) |

Early breastfeeding problems(d) | Maternal education(a); prior maternal experience with breastfeeding(d); use of formula 5 days of life(d); effective breastfeeding technique (d) |

| Espirito‐Santo et al., 2007, ** | Brazil

2003 |

Longitudinal | Strong | 220 | EBF interruption in the first 6 months | Pacifier use during the first month | 93.4% | 63% | HR 1.70

(1.27–2.29) |

HR 1.53

(1.12–2.11) |

Mother's age(a); number of prenatal visits(b); incorrect breastfeeding technique (latch) in the first month(d) | Breastfeeding duration of the previous child(d); parity(a); mother cohabiting with her husband(a), with maternal grandmother(a), with paternal grandmother(a); breastfeeding difficulty (positioning) in the 1st month(AM |

| Chaves et al., 2007, # | Brazil

2003 |

Longitudinal | Strong | 246 | EBF interruption at 6 months | Pacifier use in the follow‐up | 94.7% | N/R | N/R | RR 1.49

(1.11–2.00) |

Prior maternal intention to breastfeed(d); birth weight(c) | Maternal incorrect answer about breastfeeding technique(d); mother being user of alcohol or tobacco(a) |

| Xu et al., 2007, ** | China

2003–2004 |

Longitudinal | Strong | 1219 | EBF interruption at 6 months | Pacifier use at second week | 97% | 60.2% | N/R | HR 1.57

(1.19–2.08) |

Maternal work status(a); maternal grandmother have not breastfeeding their children(d); length decision time of feeding method (d) | Mother's age(a); maternal work status(a); maternal education(a); parity(a); type of delivery(b); first feed of the baby(e); baby's behavior to feed(c); initiate breastfeeding within 30 min of birth (e); baby needed special care unit(c); prenatal care(b); grandmother or father do not support breastfeeding in two weeks(d); feeding preference of the grandmother(d); baby's sex(c); family income(a). |

| Mascarenhas, Albernaz, Silva, & Silveira, 2006 | Brazil

2002–2003 |

Longitudinal | Strong | 973 | EBF interruption before 3 months | Pacifier use at 3 months | 61% | 64% | OR 4.25

(3.19–4.27) |

OR 4.27

(3.19–5.72) |

Maternal work status(a); family income(a); father's education(a) | Materlnal education(a); maternal smoking habits during pregnancy(a); number of prenatal visits(b) |

| Cotrim, 2005 | Brazil

2004 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 89 | EBF interruption at 4 months | Pacifier use at the first week | 100% | 50.6% | OR* 2.53

(1.39–4.60) |

RR 3.75

(1.91–7.34) |

Breastfeeding during the night(d); had a child under 5 years(a) | ‐ |

| Merten et al., 2005 | Switzerland

2003 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 1547 | EBF interruption in the first 6 months | Pacifier use in the first week | 62.7% | 76.8% | OR* 1.86

(1.46–2.36) |

HR 1.38

(1.25–1.52) |

Rooming in(d); breastfeeding within first hour(e); breastfeeding on schedule(e); free use of formula supplements(e). | Medical problems before, during, and after delivery(e); type of delivery(b); maternal smoking(a); maternal age(a); ethnic group(a); region of residence(a); maternal education(a); work status(a)and income(a) |

| Nelson, 2005 | Multicentric

(17 countries) 1995–1997 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 5142 | EBF interruption at 10–14th week | Pacifier use most of the time between 10–14th week | 57%

(20–96%) |

49%

(12–71%) |

OR 1.95

(1.07–3.56) |

OR 1.85

(1.01–3.38) |

Mother intends to breastfeed after birth(d); multiple pregnancy(b); maternal age(a); pacifier use at some moment(d) | Maternal smoke(a); bed shared at the moment of household questionnaire(d); maternal education(a) |

| Butler, Williams, Tukuitonga, & Paterson, 2004 | New Zealand

2000 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 1398 | EBF interruption in sixth week | Pacifier use at sixth week | 38% | 23.8% | OR 2.58

(1.92–3.46) |

OR 2.48

(1.79–3.44) |

Maternal work status(a); mother was working at 6 weeks(a); child attend daycare(a); parity(a); maternal smoking habits(a); to receive medical visit at home(e); to receive visiting nurse(e); baby sleep separated from their parents(d); hospital discharge of the mother and baby at different times(e). | ‐ |

| Giovannini et al., 2004, ** | Italy

1999–2000 |

Longitudinal | Strong | 2450 | EBF interruption at 6 months | Pacifier use at first month | 95.3% | N/R | N/R | HRadj 1.28

(1.13–1.45) |

Mother's body mass index(a); Infant's body weight at age 1 mo.(c); early introduction of solid foods(d) | Mother's age(a); education level(a); social class(a); maternal smoking habits(a); type of delivery(b); mothers having been breastfed themselves(d); infant's gender(c); bodyweight and length at birth(c); pacifier use at hospital discharge(e); parity(a); time at introduction of formula or solid foods(d); formula promotion at discharge(e); time at initiation of breastfeeding(e). |

| Santiago, Bettiol, Barbieri, Guttierrez, & Del Ciampo, 2003 | Brazil

2002 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 101 | EBF interruption at 4 months | Pacifier use at 4 months | 39.6% | 40.6% |

EBF interruption:

OR* 4.69 (1.99–11.05) |

EBF duration: OR 0.23

(0.08–0.60) |

Maternal education(a); Follow‐up with medical or team expert in breastfeeding(e) | Parity(a); use of oral contraceptive(a); planned pregnancy(b); birth weight(c); weight gain in the months of follow‐up(c); child sleeps more than 6 hr(d) |

| Ingram et al., 2002, *** | England

1996–1998 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 1400 | EBF interruption at second week

EBF interruption at sixth week |

Pacifier use at the second week

Pacifier use at the sixth week |

N/R | N/R | N/R | 2ª week:

ORadj 3.07 6ª week: OR adj 4.52 |

6th week:

Mother have plenty of milk supply(d); not provide other liquid to the child in the hospital(e); have sufficient support in the hospital(e); maternal age(a); breastfeeding problems(d); family support(d); health professionals advice and support(e) |

6th week:

child's sex(c); birth weight(c); gestational age(c); parity(a); type of delivery(b); to receive conflicting advice from health professionals(e); mother has enough help at home(d); days in hospital(e) |

| Aarts et al., 1999 | Sweden 1989–1992 | Longitudinal | Moderate | 506 | EBF interruption at 4 months | Pacifier use at the first month | 60% | 15.4% | OR*1.82

(1.20–2.76) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Riva et al., 1999 | Italy

1995 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 1365 | EBF interruption at 6 months | Pacifier use at the first month | 91.9% | 73.0% | RR 1.42

(1.24–1.62) |

RRadj 1.35

(1.18–1.55) OR$ 1.35 (1.18–1.55) |

Maternal education(a); supplemental use in the hospital(e) | Maternal age(a); mother's BMI(a) |

| Barros et al., 1995 | Brazil

1993 |

Longitudinal | Moderate | 605 | EBF interruption at 4 months | Pacifier use at the first month | 66.7% | 54.8% | OR* 4.53

(3.12–6.58) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Alves, Oliveira, & Moraes, 2013 | Brazil

2003–2006 |

Cross‐sectional | Strong | 2003: 589

2006: 707 |

EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr | 2003: 30.2%

2006: 46.7% |

2003: 50.9%

2006: 43.6% |

EBF interruption:

OR* 3.12 (2.48–3.93) |

EBF duration:

RPadj 0.59 (0.50–0.70) |

Maternal education(a); type of delivery(b); infant's age(c); infant follow‐up in a breastfeeding baby‐friendly unit care(e) | Maternal work status(a); birth in BFH(e); sex of the child(c); birth weight(c); immunization center(e). |

| Demitto, Bercini, & Rossi, 2013 | Brazil

2010–2011 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 362 | EBF interruption before 6 months | Pacifier use (yes/no) | N/R | N/R | OR 3.2

(1.94–5.24) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Siti, 2013 | Malaysia

2006 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 2167 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | N/R | 33.6% | OR 9.02

(3.35–25.27) |

ORadj 8.3

(3.02–22.97) |

Area of residence(a) | Sex of the child(c); race(a) |

| Warkentin et al., 2013 | Brazil

2006 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 1704 | EBF interruption before 6 months | Pacifier use (yes/no) | N/R | 39% | HR 1.14

OR* 2.33 (1.76–3.09) |

HRadj 1.53

(1.37–1.71) |

Area of residence(a); social class (a); maternal age (a) | Number of prenatal visits(b); Gestation planned(b); maternal education(a); skin‐to‐skin(e); sex of child(c); breast‐feeding within 1 hour(e) |

| Campagnolo, Louzada, Silveira, & Vitolo, 2012 | Brazil

2008 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 573 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | 0–4 month: 52.9%

4–6 month: 78.6% |

N/R | OR 3.05

(2.11–4.41) |

ORadj 2.85

(1.94–4.18) |

Maternal work status(a); Parity(a) | ‐ |

| Leone, 2012 | Brazil

2008 |

Cross‐sectional | Moderate | 724 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | 60.9% | 47.2% | N/R | ORadj 3.02

(2.10–4.36) |

Baby age(c); weight birth(c); maternal work(a) | ‐ |

| Queluz, Pereira, Santos, Leite, & Ricco, 2012 | Brazil

2009 |

Cross‐sectional | Moderate | 275 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | 70.2% | 51.6% | OR 1.50

(0.89–2.52) |

ORadj 1.06

(0.61–1.86) |

Maternal work status(a) | Maternal age(a) |

| Salustiano, Diniz, Abdallah, & Pinto, 2012 | Brazil

2008 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 667 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | 60.3% | 34.3% | OR 4.2

(2.8–6.3) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Souza, Migoto, Rossetto, & Mello, 2012 | Brazil

2008 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 325 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | 66.2% | 50.5% | OR 1.94

(1.15–3.28) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Warkentin et al., 2012 | Brazil

2007–2010 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 636 | EBF interruption before 6 months | Pacifier use before 3 months | N/R | 79.8% | OR* 1.66

(1.09–2.52) |

HR 1.87

(1.57–2.24) |

Prematurity(c); maternal age(a) | |

| Bouanene, ElMhamdi, Sriha, Bouslah, & Soltani, 2010 | Tunisia

2008 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 354 | EBF interruption at 3 months | Pacifier use before 3 months | 84.7% | 78.9% |

EBF duration:

OR 0.17 0.08–0.36 EBF interruption: OR* 4.07 (1.58–10.50) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nascimento et al., 2010 | Brazil

2005 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 839 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | 56.3% | 49.8% | OR* 2.18

(1.67–2.84) |

RP 1.69

(1.37–2.09) |

Infant's age(c); Maternal education(a). | Maternal work status(a) |

| Parizoto, Parada, Venancio, & Carvalhaes, 2009 | Brazil

1999–2003‐2006 |

Cross‐sectional | Strong | 1999: 496

2003: 674 2006: 509 |

EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months)) | 1999: 91.5%; 2003: 82.4%; 2006: 75.8% | 1999: 65.8%

2003: 57.7% 2006: 54.0% |

OR* 2.44

(1.61–3.71) |

RP 2.03

(1.44–2.84) |

‐ | Maternal education(a); parity(a); type of delivery(b). |

| Kacho, Yadollah, & Pooya, 2007 | Iran

2003–2004 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 220 | EBF interruption at 6 months | Pacifier use (yes/no) | 51.4% | 45.5% | OR* 4.18

(2.37–7.37) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Franca, Brunken, Silva, Escuder, & Venancio, 2007 | Brazil

2004 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 275 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | 65.5% | 43.3% | OR 3.27

(1.08–3.24) |

OR 3.26

(1.64–6.50) |

Mother's age(a); parity(a); Maternal education(a) | ‐ |

| Carvalhaes et al., 2007 | Brazil

2004 |

Cross‐sectional | Moderate | 380 | EBF interruption among child under 4 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 4 months) | 62.0% | 53.9% | OR 2.69

(1.76–4.11) |

OR 2.63

(1.70–4.06) |

Maternal difficulty or complaint on breastfeeding(d) | Maternal work status(a); parity(a); maternal age(a). |

| Mikiel‐Kostyra 2005a | Poland

1995 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 11422 | EBF interruption at hospital discharge | Pacifier use while in hospital | 31.1% | 2.8% | OR 4.97

(3.83–6.45) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mikiel‐Kostyra 2005b | Poland

1997 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 10156 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | sixth month

91.0% |

51.0% | OR 2.49

(2.28–2.71) |

OR 2.38

(2.17–2.61) |

Maternal education(a); maternal occupation(a); Mother smoking habits(a); maternal age(a); parity(a); maternal opinion about optimal duration of BF and EBF(d); father's education(a); father's occupation(a). | Maternal marital status(a); father's age(a); working sector of the mother and father(a); father being a smoker(a); sex of the child(c); birth weight(c). |

| Franco, Nascimento, Reis, Issler, & Grisi, 2008 | Brazil

2005 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 514 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | 56.4% | 49.3% | OR* 4.04

(2.73–5.97) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Vieira, Almeida, Silva, Cabral, & Netto, 2004 | Brazil

2001 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 1216 | EBF interruption at 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months | 61.5% | 59.2% | RP 1.60

(1.39–1.84) OR* 2.18 (1.72–2.76) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Audi, Correa, & Latorre, 2003 | Brazil

1999 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 346 | EBF interruption among child under 6 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 6 months) | 4‐6 months 90.4% | 43.4% | OR 4.19

(2.38–7.41) |

OR 4.41

(2.57–7.59) |

Type of delivery(b) | ‐ |

| Cotrim, Venancio, & Escuder, 2002 | Brazil

1999 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 22188 | EBF interruption in under 4 months | Pacifier use in the last 24 hr (under 4 months) | 80.8% | 61.3% | OR 3.26

(3.00–3.50) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kelmanson, 1999 | Russia

1998 |

Cross‐sectional | Weak | 192 | EBF interruption between 2 and 4 months | Pacifier use between 2 and 4 months | 50.5% | 60.9% | OR* 1.81

(1.00–3.26) |

N/R | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ford et al., 1994 | New Zealand | Cross‐sectional | Weak | 1592 | EBF interruption at fourth week | Frequent pacifier use in the last two weeks | 39.0% | 18.3% | OR 2.00

(1.39–2.40) |

OR 1.96

(1.35–2.84) |

Multiple pregnancy(b); infant needed hospitalization in the NICU(c); Maternal marital status(a); Occasional use of pacifiers in the last two weeks(d) | Maternal work status(a); sex of the child(c); maternal race (a); Maternal age(a); parity(a); gestational age when mother started prenatal care(b); Pre‐natal care(b); bed sharing(d); infant birth weight(c); Maternal smoke habits(a) |

Prevalence provided by publication or calculated from data provided in the paper. The prevalence corresponded to the age group as defined in the outcome and intervention.

OR adjusted calculated from data provided by the study.

OR unadjusted calculated from data provided by the study.

Not included in the meta‐analysis because it was not possible to calculate the OR with the data available.

Not included in the meta‐analysis because it was not possible to calculate the IC with the data available.

Relative Risk (RR) was considered in the meta‐analysis as a proxy of OR

N/R – Not reported

a,b – Mikael‐Kostyra et al (2005) published the results from two surveys in the same paper, so the results are presented by survey (a) 1995 and (b)1997

Category variable group:(a) Mother and family characteristics; (b) Pregnancy and childbirth factors; (c) Infant characteristics; (d) Breastfeeding technique and family support; (e) Breastfeeding assistance

It is noteworthy that regardless of the design of the study, there was no standard infant age at which pacifier use was measured in prospective studies (hospital, second week, 1 month, sixth week, third month, less than 4 month or 6 month). Most cross‐sectional studies assessed pacifier use status in the last 24 hr. All studies defined EBF according to WHO (WHO, 2008). Of the 46 selected studies, only two were RCTs, 20 were longitudinal and 24 cross‐sectional. The RCTs (Jenik et al., 2009; Kramer et al., 2001) found no relationship between pacifier use and the duration of EBF in the third month of life. Both included only women highly motivated to breastfeed. Both studies used different interventions to test the hypothesis that use of pacifier influences EBF duration. Jenik et al. (2009) randomized participants to the intervention (pacifier use) or control group. Parents of intervention group infants were given a pacifier, a type that was not typically used in the country, and they were advised to start using it only after breastfeeding had been established and the baby was gaining weight at 15 days. By contrast, Kramer et al. (2001) randomly assigned participants to avoiding using pacifiers (intervention group) or to the control group. The intervention group was explained the pros and cons of pacifier use and discussed strategies to soothe the baby without using a pacifier. Although the intervention led to a reduction in pacifier use or prevented the early introduction of it, the intervention was not associated with EBF duration.

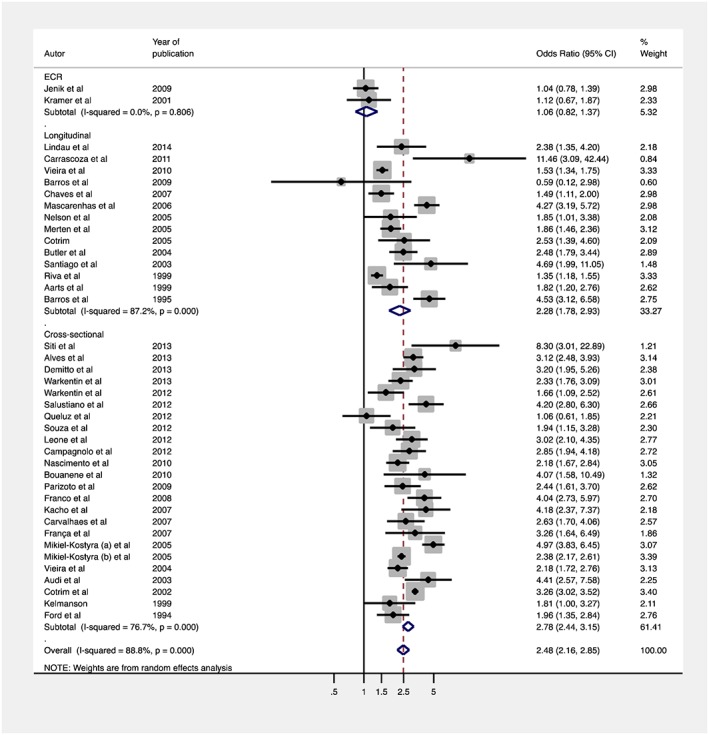

Findings were mixed across study designs (Figure 3). The OR summarizing the pooled random effects for the association between pacifier use and interruption of EBF was 2.48 OR (95% CI, 2.16–2.85), although heterogeneity was high (I 2 = 88.8%). Stratifying results by study design showed that the pooled random effects OR for RCTs was 1.6 (95% CI, 0.82–1.37), for longitudinal studies it was 2.28 (95% CI, 1.78–2.93) and for cross‐sectional studies it was 2.78 (95% CI, 2.44–3.15). Heterogeneity was high among observational studies but not among RCTs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Random effects of meta‐analysis of studies evaluating the association between pacifier use and EBF interruption

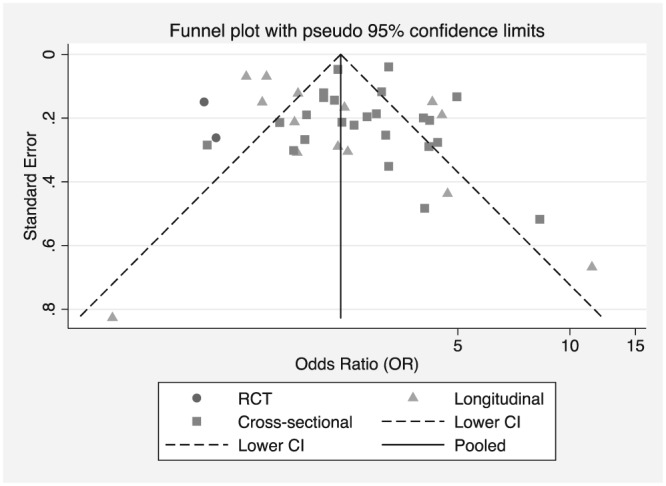

Egger's test suggests the absence of publication bias (p = 0.958). However, the asymmetrical plot observed in the funnel plot (Figure 4) may be due to low methodological quality of small studies and can indicate others sources of heterogeneity of smaller studies (Sterne et al., 2001).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot estimates from studies evaluating pacifier use and interruption of EBF versus the standard error of measurement by study design

In the subgroup analyses, the higher pooled effects were observed in observational versus RCTs, studies with infants who were younger at assessment of pacifier use, studies with low methodological quality, and studies carried out in middle‐ and low‐income countries (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate meta‐regression and pooled odds ratio estimates of association between pacifier use on the interruption of EBF based on 40 studies

| n* | Pooled OR (CI 95%) | Meta‐regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p‐value† | % Explained heterogeneity‡ | ||||

| Study design | |||||

| RCT | 2 | 1.06 (0.82–1.36) | index | 40.2 | |

| Longitudinal | 14 | 2.28 (1.78–2.93) | 0.025 | ||

| Cross‐sectional | 24 | 2.78 (2.44–3.15) | 0.003 | ||

| Sample size | |||||

| >1000 | 15 | 2.30(1.83–2.88) | index | 1.5 | |

| 301–1000 | 15 | 2.96 (2.46–3.55) | 0.116 | ||

| ≤ 300 | 10 | 2.18(1.47–3.22) | 0.001 | ||

| Exposure measurement (pacifier) | |||||

| Use among children under 4 or 6 months | 24 | 2.62 (2.30 ‐ 2.99) | index | 31.7 | |

| Use of 2–4 months | 8 | 2.10 (1.30–3.40) | 0.183 | ||

| Use before 6th week | 5 | 2.05 (1.47–2.86) | 0.221 | ||

| Use before the second week / hospital discharge | 3 | 3.27(1.90–5.64) | 0.414 | ||

| Outcome measurement (EBF interruption) | |||||

| Among those younger than 4 or 6 months | 25 | 2.54 (2.17–2.97) | index | 8.4 | |

| Between 2 and 4 months | 11 | 2.35(1.59–3.46) | 0.593 | ||

| Before the 6 week | 3 | 1.90 (1.39–2.60) | 0.303 | ||

| Hospital discharge | 1 | 4.97 (3.83–6.45) | 0.134 | ||

| Setting | |||||

| High income country/multicentric | 12 | 1.93 (1.50–2.48) | index | 2.8 | |

| Middle−/Low‐income country | 28 | 2.79 (2.37–3.29) | 0.020 | ||

| Publication year | |||||

| ≤2009 | 22 | 2.57 (2.15–3.08) | index | 0.04 | |

| >2009 | 18 | 2.36 (1.89–2.95) | 0.567 | ||

| Publication language | |||||

| English | 17 | 2.25 (1.82–2.77) | index | −2.5 | |

| Portuguese | 22 | 2.66 (2.21–3.21) | 0.275 | ||

| Other | 1 | 4.07(1.58–10.49) | 0.383 | ||

| Effect size | |||||

| Adjusted | 17 | 2.50 (2.06–3.03) | index | −11.0 | |

| Crude | 23 | 2.45 (1.99–2.99) | 0.812 | ||

| Quality score | |||||

| Strong | 7 | 2.25 (1.40–3.61) | index | 5.3 | |

| Moderate | 13 | 2.19 (1.69–2.83) | 0.966 | ||

| Weak | 20 | 2.77 (2.34–3.28) | 0.230 | ||

| Total | 40 | 2.48 (2.16–2.85) | |||

number of studies;

p‐value of the meta‐regression;

R2 adj (proportion of variance between studies)

Meta‐regressions showed that the study design contributed 40.2% of the global heterogeneity. Others study characteristics such as the age of assessment of pacifier use; the age of assessment of EBF interruption; study quality score and setting explained 31.7%, 8.4%, 5.3%, and 2.8% of the global heterogeneity, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

We found a positive association between pacifier use and EBF interruption in observational studies (longitudinal and cross‐sectional) and no association in the RCTs, which were of strong quality but had very limited external validity. Previous systematic reviews (O'Connor et al., 2009; Santos Neto et al., 2008) and meta‐analyzes (Jaafar et al., 2012; Karabulut et al., 2009) examining the influence of pacifier use in breastfeeding outcomes were published between 2008 and 2009; despite divergences in the search and selection criteria and possible bias inherent in each of them, collectively both reviews and meta‐analyzes found results consistent with our review.

Our meta‐analysis and meta‐regression quantified for the first time the high level of heterogeneity across studies examining the association between pacifier use and EBF. This heterogeneity was explained mainly by the study design, sample size, and socio‐economic setting as well as differences in the infants' age of assessment of pacifier use and a lack of a standard definition of “pacifier use” (i.e., age of introduction, frequency, and intensity of use).

Strengths and weaknesses inherent to designs of the studies, such as, randomization and bias risk should be considered for determining the internal and external validity and thus the likelihood for a causal relationship between pacifier use and early interruption of EBF. The impact on EBF may vary accordingly to the effectiveness of implementation of the pacifier use intervention. Both RCTs found that compliance with the pacifier use or avoidance intervention was low, so the impact of the intervention on EBF might have been strongly diluted especially when using intent‐to‐treat analyses. To address this issue, observational analyses of RCTs have been recommended (Victora, Habicht, & Bryce, 2004). Indeed, when pooling the data from both the intervention and control groups, Kramer et al. (2001) found an association between pacifier use and EBF interruption. Besides, both RCTs included only women who were highly motivated to breastfeed (Kramer et al., 2001; Jenik et al., 2009) and one of them also had as inclusion criteria for breastfeeding to be established and for the infant to be gaining weight at 15 days of life before recommending the introduction of the pacifier (Jenik et al., 2009). This may explain why in our meta‐analysis, the RCTs provided an indication of minimal effect, or no effect, while observational studies provided an estimate of the maximal effect (Black, 1996). Indeed, the literature has shown that women's lack of motivation or intention to breastfeed (Victora et al., 1997; Chaves et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2005; Mikiel‐Kostyra, Mazur, & Wojdan‐Godek, 2005; Xu et al., 2007; Boccolini, Carvalho, & Oliveira, 2015) as well as the initial difficulties in breastfeeding (Victora et al., 1997; Carvalhaes, Parada, & Costa, 2007; Kronborg & Vaeth, 2009; Espirito‐Santo, de Oliveira, & Giugliani, 2007; Boccolini et al., 2015) are strong predictor of EBF interruption. These predictors can also determine both the likelihood of introduction of pacifiers as the patterns of their use (daily, partial, and intense) (Victora et al., 1997; Kramer et al., 2001; Aarts et al., 1999). Thus, despite their relatively stronger internal validity, RCTs can have major external validity limitations (Black, 1996; Victora et al., 2004), preventing the extrapolation of findings from RCT's to the general population, that is, women who are less motivated to breastfeed or to the context when the pacifier is introduced before breastfeeding is established as mentioned by Jenik et al. (2009).

A possible advantage of the prospective studies reviewed (vs. RCT's and cross‐sectional) is that the influence of age of introduction of pacifiers (Aarts et al., 1999) as well as pacifier use pattern (e.g., frequent user, often user, and occasional user) (Aarts et al., 1999) on breastfeeding behaviors can be investigated. Although these analyses could be key to better understand the relationship between pacifier use and EBF interruption most prospective studies reviewed did not conduct them. This is relevant for understanding if and how age of introduction of pacifiers and their pattern of use mediate or modify the relationship between pacifier use and EBF interruption (Vogel et al., 2001; Kronborg & Vaeth, 2009; Buccini et al., 2016, Howard et al., 1999). A possible strategy for better standardizing studies in this area is to categorize pacifier use as dichotomous based on its introduction before the second week or not (Kronborg & Vaeth, 2009; Lindau et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2007; Ingram, Johnson, & Greenwood, 2002), or use in the first month (Espirito‐Santo et al., 2007; Giovannini et al., 2004, Aarts et al., 1999; Barros et al., 1995; Riva et al., 1999) by the time breastfeeding is more likely to be established. This study design standardization attempt may be highly relevant as our review found that pacifier use definition and infant age at which it was assessed – was the second characteristic that best explained the heterogeneity across studies included in the meta‐analysis. Whereas analyses from prospective studies can be adjusted for wide variation in potential confounders, RCT's are designed to equalize confounders between groups at baseline, once again, limiting their external validity (Victora et al., 2004).

An important question that our review raises is: Which would be the best study design to further test and explain the complexity of the relationship between pacifier use and the EBF interruption? This question is not simple to answer as it involves not just measuring and understanding biological but also behavioral pathways (Grimes & Schulz, 2002). In this case, the causal pathway can happen at least through three paths: (a) pacifier introduction leading to EBF interruption where the effect of pacifier use and the pattern of use (frequency and intensity) can lead to “nipple confusion” (Neifert et al., 1995; Righard et al. 1998); (b) EBF interruption or breastfeeding problems leading to pacifier introduction (i.e., reverse causality meaning that breastfeeding problems or interruption leads to the introduction of pacifier rather than the reverse); where pacifier use could be a marker of breastfeeding difficulties or reduced motivation to breastfeed (i.e., both pacifier introduction and interruption of EBF based on maternal preference) (Victora et al., 1997; Kramer et al., 2001) ; (c) mothers (families) who follow the recommendation of avoiding pacifier may also try to follow other recommendations to breastfeed exclusively for longer such as breastfeeding on demand (Feldens, Ardenghi, Cruz, Scalco, & Vitolo, 2013).

Prospective studies that evaluated the effect of very early pacifier use on later breastfeeding outcomes (DiGirolamo et al., 2008; Soares et al., 2003; Howard et al., 2003; Vogel et al., 2001; Hörnell et al., 1999; Victora et al., 1997) as well as the studies that separated the effects of early breastfeeding problems from the effects of pacifier use (Kronborg & Vaeth, 2009) support conducting further research to find out if the associations between pacifier use and poor breastfeeding outcomes is causal or not. Future studies need to take into account in their designs ways to deal with the possibility of reverse causality (Grimes & Schulz, 2002). For example, Vogel et al. (2001) found in a prospective longitudinal study that in almost all cases, the pacifier was introduced prior to complete weaning from breast milk, and not the other way around. Also, cohort studies need to carefully measure the level of motivation that mothers have to breastfeed and the way they use the pacifier. Ultimately, better‐designed prospective cohort studies and RCT's are needed to confirm or refute the hypothesis that pacifier use increases the risk of the premature discontinuation of EBF.

Crude and adjusted ORs were not significantly different, probably because of the wide variety of covariates used across the included studies. However, based on our heterogeneity analyses, we recommend for future observational studies to apply multivariable analyses that adjust for and test for effect modification by maternal age and education, intention to breastfeed during pregnancy, onset and nature of breastfeeding difficulties, and family support (Victora et al., 2016; Boccolini e al. 2015; Buccini, Benício, & Venancio, 2014). Furthermore, future studies in this area should standardize the age at which pacifier use is assessed and also provide a clear definition of “pacifier use” including age of introduction, frequency, and intensity of use. Because the level of economic development of the countries modified the relationship between pacifier use and EBF it's strongly recommended to conduct studies in this area in different world regions using the standard methodologies recommended above.

This meta‐analysis should be interpreted considering some possible limitations. First, all systematic reviews and meta‐analyses are subject to publication bias. In order to minimize this limitation, this study was based on a comprehensive and sensitive search. Studies were included regardless of methodological quality and the electronic search strategy was supplemented by a manual search of studies. In addition, we tested formally for publication bias and did not find it. Second, to minimize selection bias the protocol for this systematic review was registered a priori (CRD42014014527 PROSPERO). Third, there was strong statistical heterogeneity across studies as it was expected because we included studies with different methodologies as well as different definitions for pacifier use (intervention or exposure). To address the high level of heterogeneity, we used the random effect option for summarizing the effect size of the association. Also, one of the RCT's included (Jenik et al., 2009) is likely to have a conflict of interest related to the funding source (Di Mario, Cattaneo, Basevi, & Magrini, 2011). Because all these potential limitations were taken into account in the design of this systematic review and meta‐analysis, we conclude that our systematic review findings are indeed robust.

In view of the available evidence, given the limitations of the RCT's included, it can be concluded that despite the lack of association found in the RCT's, observational studies strongly suggest that pacifier use may be a risk factor for the premature discontinuation of EBF. A recent robust Brazilian study published after the search was completed supports this conclusion (Buccini et al., 2016). The trade‐off between a potentially strong benefits that may result from improved breastfeeding outcomes resulting from reducing pacifier use (Buccini et al., 2016), as well as the protection of EBF against SIDS (Hauck, Thompson, Tanabe, Moon, & Vennemann, 2011) vis‐à‐vis the possible protection of pacifiers against SIDS (Hauck, Omojokun, & Siadaty, 2005), should be considered when making recommendations about pacifier use and EBF practices on a large‐scale. The current WHO recommendation on pacifier use is supported by our findings as it focuses on the risk of poor breastfeeding outcomes as a likely result of pacifier use. Future benefit–risk analyses studies should examine if the trade‐off between pacifier‐related breastfeeding outcomes and SIDS justifies maintaining the current recommendation or if it needs to be expanded to offer more context‐specific options.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

This study was funded by the Brazilian government through the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Level Personnel— CAPES Foundation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

CONTRIBUTIONS

GSB has designed the systematic review project. She conducted all steps of bibliography searches and paper selection also conducted the analysis, interpreted the results and drafted the paper. RP‐E has interpreted the results and drafted the paper. LMP has participated in the steps of paper selection and reviewed the final version of the paper. CLA has participated in the steps of paper selection and reviewed the final version of the paper. SIV has designed the systematic review project also interpreted the results and drafted the paper.

Supporting information

Table S1. Searches strategies for each database

Supporting info item

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Dr. Mariana Minatel Braga Fraga from Dental School of University of São Paulo, Brazil, for her comments on the methodology of the review.

Buccini GdS, Pérez‐Escamilla R, Paulino LM, Araújo CL, Venancio SI. Pacifier use and interruption of exclusive breastfeeding: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13:e12384 10.1111/mcn.12384

REFERENCES

- Aarts, C. , Hörnell, A. , Kylberg, E. , Hofvander, Y. , & Gebre‐Medhin, M. (1999). Breastfeeding patterns in relation to thumb sucking and pacifier use. Pediatrics, 104(4), e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves, A. L. , Oliveira, M. I. , & Moraes, J. R. (2013). Breastfeeding‐Friendly Primary Care Unit Initiative and the relationship with exclusive breastfeeding. Revista de Saúde Pública, 47(6), 1130–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armijo‐Olivo, S. , Stiles, C. R. , Hagen, N. A. , Biondo, P. D. , & Cummings, G. G. (2012). Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment tool: Methodological research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(1), 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audi, C. A. F. , Correa, A. M. S. , & Latorre, M. R. D. O. (2003). Complementary feeding and factors associated to breast‐feeding and exclusive breast‐feeding among infant up to 12 months of age, Itapira, São Paulo, 1999. Rev. Bras. Saude Mater. Infant, 3(1), 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, F. C. , Victora, C. G. , Semer, T. C. , Tonioli Filho, S. , Tomasi, E. , & Weiderpass, E. (1995). Use of pacifiers is associated with decreased breast‐feeding duration. Pediatrics, 95(4), 497–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros, V. O. , Cardoso, M. A. A. , Carvalho, D. F. , Gomes, M. M. R. , Ferraz, N. V. A. , & Medeiros, C. C. M. (2009). Maternal breastfeeding and factors associated to early weaning in infants assisted by the family health program. Nutrire Rev. Soc. Bras. Aliment. Nutr, 34(2), 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Berkley, C. S. , Hoaglin, D. C. , Mosteller, F. , & Colditz, G. A. (1995). A random‐effects regression model for meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 14(4), 395–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, N. (1996). Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ, 312(7040), 1215–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccolini, C. S. , Carvalho, M. L. , & Oliveira, M. I. (2015). Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life in Brazil: A systematic review. Revista de Saúde Pública, 49, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouanene, I. , ElMhamdi, S. , Sriha, A. , Bouslah, A. , & Soltani, M. (2010). Knowledge and practices of women in Monastir, Tunisia regarding breastfeeding. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 16(8), 879–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccini, G. S. , Benício, M. H. , & Venancio, S. I. (2014). Determinants of using pacifier and bottle‐feeding. Revista de Saúde Pública, 48(4), 571–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccini, G. S. , Perez‐Escamilla, R. , & Venancio, S. I. (2016). Pacifier use and exclusive breastfeeding in Brazil. Journal of Human Lactation, 32(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, S. , Williams, M. , Tukuitonga, C. , & Paterson, J. (2004). Factors associated with not breastfeeding exclusively among mothers of a cohort of Pacific infants in New Zealand. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 117(1195), U908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X. , Wardlaw, T. , & Brown, D. W. (2012). Global trends in exclusive breastfeeding. International Breastfeeding Journal, 7(1), 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnolo, P. D. B. , Louzada, M. L. C. , Silveira, E. L. , & Vitolo, M. R. P. (2012). Feeding practices and associated factors in the first year of life in a representative sample of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul. Brazil. Rev. Nutr, 25(4), 431–439. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Paediatric Society Community Paediatrics Committee (2003). Recommendations for the use of pacifiers. Paediatrics & Child Health, 8, 515–519.20019941 [Google Scholar]

- Carrascoza, K. C. , Possobon Rde, F. , Ambrosano, G. M. , Costa Júnior, A. L. , & Moraes, A. B. (2011). Determinants of the exclusive breastfeeding abandonment in children assisted by interdisciplinary program on breast feeding promotion. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 16(10), 4139–4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalhaes, M. A. B. L. , Parada, C. M. G. L. , & Costa, M. P. (2007). Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in children under four months old in Botucatu‐SP. Brazil. Rev. Latino‐Am. Enfermagem, 15(1), 62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, R. G. , Lamounier, J. A. , & César, C. C. (2007). Factors associated with duration of breastfeeding. Jornal de Pediatria, 83(3), 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotrim LC (2005) Exclusive breast‐feeding and pacifier use in the first four months of life thesis in Portuguese. Available at: http://saudepublica.bvs.br/pesquisa/resource/pt/sus-19210 (Accessed 27 May 2016)

- Cotrim, L. C. , Venancio, S. I. , & Escuder, M. M. L. (2002). Pacifier use and breast‐feeding in children under four months old in the State of São Paulo. Rev. Bras. Saúde Matern. Infant, 2(3), 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, J. L. A. , Leite, A. M. , & Machado, M. M. (2009). Breastfeeding and pacifier use: implications for healthy policy. JPediatr (Rio J), 85(5), 462–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks, J. J. , Altman, D. G. , & Bradburn, M. J. (2001). Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta‐analysis In Egger M., Davey Smith G., & Altman D. G. (Eds.), Systematic reviews in health care: meta‐analysis in context (2nd ed.). (pp. 285–311). London: BMJ Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Demitto, M. O. , Bercini, L. O. , & Rossi, R. M. (2013). Use of pacifier and exclusive breastfeeding. Esc Anna Nery, 17(2), 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Di Mario S, Cattaneo A, Basevi V, Magrini N. (2011). Feedback 1 In: Effect of restricted pacifier use in breastfeeding term infants for increasing durantion of breastfeeding (authors, Jaafar SH, Jahanfar S, Angolkar M, Ho JJ.) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11:7: CD007202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGirolamo, A. M. , Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. , & Fein, S. B. (2008). Effect of maternitycare practices on breastfeeding. Pediatrics, 122, S2–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelman, A. I. , Schanler, R. J. , Johnston, M. , Landers, S. , Noble, L. , Szucs, K. , & Viehmann, L. (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129(3), e827–e841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espirito‐Santo, L. C. , de Oliveira, L. D. , & Giugliani, E. R. (2007). Factors associated with low incidence of exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months. Birth, 34(3), 212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein, S. B. (2009). Exclusive breastfeeding for under‐6‐month‐old children. Jornal de Pediatria, 85(3), 181–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldens, C. A. , Ardenghi, T. M. , Cruz, L. N. , Scalco, G. , & Vitolo, M. R. (2013). Advising mothers about breastfeeding and weaning reduced pacifier use in the first year of life: A randomized trial. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 41(4), 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, R. P. , Mitchell, E. A. , Scragg, R. , Stewart, A. W. , Taylor, B. J. , & Allen, E. M. (1994). Factors adversely associated with breastfeeding in New Zealand. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 30(6), 483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franca, G. V. A. , Brunken, G. S. , Silva, S. M. , Escuder, M. M. , & Venancio, S. I. (2007). Breast‐feeding determinants on the first year of life of children in a city of Midwestern Brazil. Revista de Saúde Pública, 41(5), 711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco, S. C. , Nascimento, M. B. R. , Reis, M. A. M. , Issler, H. , & Grisi, S. J. F. E. (2008). Exclusive breastfeeding in infants attending public health care units in the municipality of Joinville, State of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant, 8(3), 291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini, M. , Riva, E. , Banderali, G. , Scaglioni, S. , Veehof, S. H. , Sala, M. , … Agostoni, C. (2004). Feeding practices of infants through the first year of life in Italy. Acta Paediatrica, 93(4), 492–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, D. A. , & Schulz, K. F. (2002). Cohort studies: Marching towards outcomes. Lancet, 359(9303), 341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grummer‐Strawn, L. , & Rollins, N. (2015). Summarizing the health effects of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatrica, 104(467), 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, F. R. , Omojokun, O. O. , & Siadaty, M. S. (2005). Do pacifiers reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? A meta‐analysis. Pediatrics, 116, e716–e723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, F. R. , Thompson, J. M. D. , Tanabe, K. O. , Moon, R. Y. , & Vennemann, M. M. (2011). Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: A meta‐analysis. Pediatrics, 128(1), 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. , & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21, 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. , Thompson, S. G. , Deeks, J. J. , & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ, 327, 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörnell, A. , Aarts, C. , Kylberg, E. , Hofvander, Y. , & Gebre‐Medhin, M. (1999). Breastfeeding patterns in exclusively breastfed infants: A longitudinal prospective study in Uppsala, Sweden. Acta Paediatrica, 88(2), 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta BL, Bahl R, Martines JC, Victora CG (2013) Evidence on the long‐term effects of breastfeeding: Systematic review and meta‐analyses. World Health Organization. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/79198/1/9789241505307_eng.pdf (Accessed 27 May 2016)

- Horta, B. L. , Loret de Mola, C. , & Victora, C. G. (2015). Long‐term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, 104(467), 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, C. R. , Howard, F. M. , Lanphear, B. , deBlieck, E. A. , Eberly, S. , & Lawrence, R. A. (1999). The effects of early pacifier use on breastfeeding duration. Pediatrics, 103(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, C. R. , Howard, F. M. , Lanphear, B. , Eberly, S. , deBlieck, E. A. , Oakes, D. , & Lawrence, R. A. (2003). Randomized clinical trial of pacifier use and bottle‐feeding or cupfeeding and their effect on breastfeeding. Pediatrics, 111(3), 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, J. , Johnson, D. , & Greenwood, R. (2002). Breastfeeding in Bristol: Teaching good positioning, and support from fathers and families. Midwifery, 18(2), 87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, S. H. , Jahanfar, S. , Angolkar, M. , & Ho, J. J. (2012). Effect of restricted pacifier use in breastfeeding term infants for increasing durantion of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11(7), CD007202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenik, A. G. , Vain, N. E. , Gorestein, A. N. , Jacobi, N. E. , & Pacifier and Breastfeeding Trial Group (2009). Does the recommendation to use a pacifier influence the prevalence of breastfeeding? The Journal of Pediatrics, 155(3), 350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacho, M. A. , Yadollah, Z. , & Pooya, E. (2007). Comparison of exclusively breast‐feeding rate between pacifier suckers and non‐suckers infants. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics, 17, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Karabulut, E. , Yalçin, S. S. , Ozdemir‐Geyik, P. , & Karaağaoğlu, E. (2009). Effect of pacifier use on exclusive and any breastfeeding: A meta‐analysis. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 51, 35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelmanson, I. A. (1999). Use of a pacifier and behavioral features in 2‐4‐month‐old infants. Acta Paediatrica, 88(11), 1258–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M. S. , Barr, R. G. , Dagenais, S. , Yang, H. , Jones, P. , Ciofani, L. , & Frederick, J. (2001). Pacifier use, early weaning, and cry/fuss behavior: A randomized controlled. JAMA, 286(3), 322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronborg, H. , & Vaeth, M. (2009). How are effective breastfeeding technique and pacifier use related to breastfeeding problems and breastfeeding duration? Birth, 36, 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbok, M. H. , Wardlaw, T. , Blanc, A. , Clark, D. , & Terreri, N. (2006). Trends in exclusive breastfeeding: Findings from the 1990s. Journal of Human Lactation, 22(3), 272–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone, C. R. , Sadeck, L. S. R. , & Programa Rede de Proteção a Mãe Paulistana (2012). Risk factors associated to weaning from breastfeeding until six months of age in São Paulo city. Rev Paul Pediatr, 30(1), 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lindau, J. F. , Mastroeni, S. , Gaddini, A. , Lallo, D. D. , Nastro, P. F. , Patanè, M. , … Fortes, C. (2014). Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding cessation: Identifying an “at risk population” for special support. European Journal of Pediatrics, 174(4), 533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge, C. J. , Tan, D. J. , Lau, M. X. , Dai, X. , Tham, R. , Lowe, A. J. , … Dharmage, S. C. (2015). Breastfeeding and asthma and allergies: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, 104(467), 38–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, M. L. W. , Albernaz, E. P. , Silva, M. B. , & Silveira, R. B. (2006). Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and its determiners in the first 3 months of life in the South of Brazil. Jornal de Pediatria, 82(4), 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten, S. , Dratva, J. , & Ackermann‐Liebrich, U. (2005). Do baby‐friendly hospitals influence breastfeeding duration on a national level? Pediatrics, 116(5), e702–e708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikiel‐Kostyra, K 1., Mazur, J. , & Wojdan‐Godek, E. (2005). Factors affecting exclusive breastfeeding in Poland: Cross‐sectional survey of population‐based samples. Soz Praventiv Med, 50(1), 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , Altman, D. G. , & The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, M. B. , Reis, M. A. , Franco, S. C. , Issler, H. , Ferraro, A. A. , & Grisi, S. J. (2010). Exclusive breastfeeding in southern Brazil: Prevalence and associated factors. Breastfeeding Medicine, 5(2), 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neifert, M. , Lawrence, R. , & Seacat, J. (1995). Nipple confusion: Toward a formal definition. The Journal of Pediatrics, 126(6), S125–S129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, E. A. S. , Ly‐Mee, Y. , Williams, S. , & Internacional Child Care Practices Study Group Members (2005). International child care practices study: Breastfeeding and pacifier use. Journal of Human Lactation, 21(3), 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor, N. R. , Tanabe, K. O. , Siadaty, M. S. , & Hauck, F. R. (2009). Pacifiers and breastfeeding: A systematic review. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163, 378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parizoto, G. M. , Parada, C. M. G. L. , Venancio, S. I. , & Carvalhaes, M. A. B. L. (2009). Trends and patterns of exclusive breastfeeding for under‐6‐month‐old children. JPediatr (Rio J), 85(3), 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passanha, A. , Benicio, M. H. D. A. , Venancio, S. I. , & Reis, M. C. G. (2015). Influence of the support offered to breastfeeding by maternity hospitals. Rev. Saúde Pública, 49(85). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peres, K. G. , Cascaes, A. M. , Nascimento, G. G. , & Victora, C. G. (2015). Effect of breastfeeding on malocclusions: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, 104(467), 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez‐Escamilla, R. , Martinez, J. L. , & Segura‐Perez, S. (2016). Impact of the Baby‐friendly Hospital Initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: A systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition, [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queluz, M. C. , Pereira, M. J. B. , Santos, C. B. , Leite, A. M. , & Ricco, R. G. (2012). Prevalence and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in the city of Serrana, São Paulo, Brazil. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da U.S.P., 46(3), 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righard, L. (1998). Are breastfeeding problems related to incorrect breastfeeding technique and the use of pacifier and bottles? Birth, 25(1), 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva, E. , Banderali, G. , Agostoni, C. , Silano, M. , Radaelli, G. , & Giovannini, M. (1999). Factors associated with initiation and duration of breastfeeding in Italy. Acta Paediatrica, 88(4), 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salustiano, L. P. Q. , Diniz, A. L. D. , Abdallah, V. O. S. , & Pinto, R. M. C. (2012). Factors associated with duration of breastfeeding in children under six months. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia, 34(1), 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar, M. J. , Sinha, B. , Chowdhury, R. , Bhandari, N. , Taneja, S. , Martines, J. , & Bahl, R. (2015). Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality, a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica, 104(467), 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, L. B. , Bettiol, H. , Barbieri, M. A. , Guttierrez, M. R. P. , & Del Ciampo, L. A. (2003). Promotion of breastfeeding: The importance of pediatricians with specific training. Jornal de Pediatria, 79(6), 504–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos Neto, E. T. , Oliveira, A. E. , Zandonade, E. , & Molina, M. C. B. (2008). Pacifier use as a risk factor for reduction in breastfeeding duration: A systematic review. Rev Bras Saúde Materno Infantil, 8(4), 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, S. , & Natale, R. (2009). Risks and benefits of pacifiers. American Family Physician, 79(8), 681–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siti, Z. M. S J, J KN, M N B, A T (2013). Pacifier use and its association with breastfeeding and Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) in children below 2 years old. The Medical Journal of Malaysia, 68(2), 125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]