Abstract

Rates of breastfeeding uptake are lower after a caesarean birth than vaginal birth, despite caesarean rates increasing globally over the past 30 years, and many high‐income countries reporting overall caesarean rates of above 25%. A number of factors are likely to be associated with women's infant feeding decisions following a caesarean birth such as limited postoperative mobility, postoperative pain, and ongoing management of medical complications that may have triggered the need for a caesarean birth. The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate evidence of interventions on the initiation and duration of any and exclusive breastfeeding among women who had a planned or unplanned caesarean birth. Seven studies, presenting quantitative and qualitative evidence, published in the English language from January 1994 to February 2016 were included. A limited number of interventions were identified relevant to women who had had a caesarean birth. These included immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact, parent education, the provision of sidecar bassinets when rooming‐in, and use of breast pumps. Only one study, an intervention that included parent education and targeted breastfeeding support, increased initiation and continuation of breastfeeding, but due to methodological limitations, findings should be considered with caution. There is a need to better understand the impact of caesarean birth on maternal physiological, psychological, and physical recovery, the physiology of lactation and breastfeeding and infant feeding behaviors if effective interventions are to be implemented.

Keywords: breastfeeding duration, breastfeeding support, breast pumps, caesarean section, rooming‐in, skin‐to‐skin

1. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organisation (WHO) and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) recommends that infants are exclusively breastfed for a minimum of 6 months, with continued breastfeeding recommended until child age of 2 years or over to optimize growth, development, and health (WHO/UNICEF, 2003). Breastfeeding has many health benefits for infant and later child health including reduced risk of gastrointestinal infection, otitis media, respiratory tract infection, asthma, allergies, obesity, type I and 2 diabetes, and sudden infant death syndrome (Bowatte, Tham, Allen, et al., 2015; Giugliani, Horta, de Mola, Lisboa, & Victora, 2015; Horta & Victora, 2013; Horta, de Mola, & Victora, 2015; Lodge, Tan, Lau, et al., 2015; Ip, Chung, Raman, Trikalinos, & Lau, 2009; Victora et al., 2016). Benefits for the woman include lower rates of ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and type 2 diabetes (Aune, Norat, Romundstad, & Vatten, 2014; Chowdhury, Sinha, Sankar, et al., 2015; Ip et al., 2009; Victora et al., 2016). Breastfeeding has been associated with improved maternal/infant bonding (MacGregor & Hughes, 2010) and increased child intelligence (Victora et al., 2016). Despite breastfeeding being a priority public health intervention with robust evidence of benefit, duration of exclusive breast feeding is shorter in high‐income countries when compared with low income countries. Even so, in low and middle income countries, only 37% of infants younger than 6 months are exclusively breastfed (Victora et al., 2016).

Exclusive breastfeeding rates in European countries based on nationally collated data on infants at 6 months of age have been reported as 25% in Spain, 33% in Sweden, and 37% in Hungary (Cattaneo, Cogoy, Macaluso, & Tamburlini, 2012), although different definitions and methods used to collate data from each country limit comparisons. In the UK, breastfeeding initiation and duration to 6 months postnatally have increased during the last decade with an increase at 6 months from 25% in 2005 to 34% in 2010, although rates of exclusive breastfeeding remain persistently low compared with other European countries with only 1% exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months (McAndrew et al., 2012).

Decisions about infant feeding are informed by a range of complex factors including a woman's socio‐demographic background, age, ethnicity, and peer support network (McAndrew et al., 2012). It is also clear that medical interventions during labor and birth, including a caesarean section, impact on women's infant feeding decisions and are a cause for concern given increasing global caesarean birth rates, with woman who have a planned caesarean birth reported as less likely to intend to breastfeed than women who did not have a planned caesarean birth or had a vaginal birth (Hobbs, Mannion, McDonald, Brockway, & Tough, 2016; Prior et al., 2012). An overview of caesarean birth rates in 19 high‐income countries calculated an average rate of 27% in 2010 with rates in individual countries ranging from 14% to 33%, and rates have increased sharply in the majority of countries in the last 30 years (Ye, Betran, Guerrero, Souza, & Zhang, 2014). In England during 2013–2014, (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015) 26% of all births were by caesarean compared with 12% in 1990 (Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology, 2002).

There is a negative association between breastfeeding duration, birth complications, and medical interventions (Bai, Wu, & Tarrant, 2013; Brown & Jordan, 2013; Kozhimannil, Jou, Attanasio, Joarnt, & McGovern, 2014). McInnis and Chambers' (McInnes & Chambers, 2008) synthesis of qualitative research into mothers' and health professionals' experiences and perceptions of breastfeeding support noted that breastfeeding was adversely affected by interventions related to the birth or provision of inadequate postnatal pain relief. A critical review of qualitative data of women's and their supporters' perceptions of barriers and enablers to initiation and duration of breastfeeding included post‐caesarean birth pain and postoperative recovery amongst the barriers (MacKean & Spragins, 2012).

A systematic review and meta‐analysis of breastfeeding outcomes after caesarean birth (Prior et al., 2012) that synthesized data from 53 studies from 33 countries found rates of breastfeeding initiation were significantly lower after caesarean birth (pooled [odds ratio] OR: 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.76, 0.79.). Moreover, rates of any breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months were lower among women who had a caesarean birth (either planned or unplanned) compared with vaginal birth (normal or instrumental) (pooled OR for any breastfeeding: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.82, 0.91, pooled OR for exclusive breastfeeding: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.67, 0.98). Based on subgroup analysis, this review also concluded that although caesarean birth was associated with lower rates of initiation, those who initiated successfully were as likely to exclusively breastfeed at 6 months as women who had a vaginal birth, suggesting early interventions could be effective following caesarean birth.

A number of factors may influence breastfeeding experiences of women who have a caesarean birth, including maternal physical and emotional responses to surgery as well as infant health and behavior. McFadden, Baker, and Lavender (2009), in a small qualitative study involving 10 women from one UK maternity unit, noted that women underestimated the emotional and physical effects of surgery on commencing and continuing breastfeeding. Infrequent feeding (Tully & Ball, 2014) and women's limited mobility in the early days following surgery may impede efforts to provide basic infant care (Tully & Ball, 2012). High levels of postoperative pain, particularly in the first 24 hrs, were also found to have a negative impact on women's breastfeeding experiences (Karlström, Engström‐Olofsson, Norbergh, Sjöling, & Hildingsson, 2007; Tully & Ball, 2014). Surgery could impact on postpartum prolactin levels (Wang, Zhou, Zhu, Gao, & Gao, 2006) and delay lactation (Scott, Binns, & Oddy, 2007), with potential consequences for infant physiological behavior (Jain & Eaton, 2006). There is also potential for physical separation of mother and infant given higher risk of infant admission to neonatal intensive care as a consequence of respiratory disorders (Kolås, Saugstad, Daltveit, Nilsen, & Øian, 2006). Physical, psychological, and emotional support for women to breastfeed following caesarean birth was identified by McFadden et al. (2009) as essential to enable women to initiate and establish successful breastfeeding. Of note in this small study was that women whose babies were admitted to neonatal care appeared to require more psychological support, while women whose babies accompanied them to the postnatal ward described the need for more physical support.

Reductions in inpatient stay, which in UK hospitals are being informed by the rollout of “Enhanced Recovery Pathways” for planned major surgery (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2008), including caesarean sections (Wrench, Allison, Galimberti, Radley, & Wilson, 2015) that comprise preoperative assessment and standardized perioperative and postoperative management to facilitate even earlier hospital discharge could further impact on breastfeeding support needs. Evidence is needed of how maternity service providers could promote interventions to support breastfeeding in this population of women, some of whom will also have had medically complex pregnancies.

No previous systematic reviews have focused on support for breastfeeding following caesarean birth (Schmied, Beake, Sheehan, McCourt, & Dykes, 2009; Renfrew, McCormick, Wade, Quinn, & Dowswell, 2012). Given the evidence gap, the aim of this review was to evaluate evidence of interventions on the initiation and duration of any and exclusive breastfeeding among women who had a planned or unplanned caesarean birth. If appropriate data were available, the impact of such interventions on the views and experiences of women, their key supporters (e.g., partners and close family members), healthcare professionals, and healthcare resources were included. The review protocol was registered on the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO 2015:CRD42015015555).

Key messages

Few interventions to increase the uptake/duration of breastfeeding have been specifically considered following planned or unplanned caesarean birth.

The only intervention associated with higher breastfeeding rates following caesarean birth was a multicomponent intervention; however, methodological issues limit the generalizability of findings.

There is a need to better understand the impact of planned and unplanned caesarean birth on women's physiological, physical, and emotional health to better inform interventions to improve uptake and duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

Future research into the effectiveness of interventions should include sufficiently large sample sizes, clear definitions of breastfeeding uptake and duration, take account of planned and unplanned caesarean birth, and include appropriate longer term follow‐up.

Policy makers in settings with high rates of caesarean birth need to consider shorter and longer‐term consequences for maternal and infant health if breastfeeding support is not addressed as a priority, particularly for women giving birth who have physical and/or psychological comorbidity.

2. METHODS

The review protocol was developed using the process described by The Joanna Briggs Institute to consider and appraise all forms of available evidence relevant to interventions to support breastfeeding outcomes following caesarean birth. The Joanna Briggs Institute is an international research and development organization that encourages a broad, inclusive approach to evidence. This not only promotes systematic reviews of the meta‐analysis of data from randomized controlled trials but also research that uses other approaches, particularly qualitative, economic and policy research (see http://www.joannabriggs.org). The Joanna Briggs Institute levels of evidence are shown in Box 1:

BOX 1. The Joanna Briggs Institute levels of evidence

Levels of evidence for effectiveness

Level 1 Experimental designs (strongest evidence)

Level 1.a—Systematic review of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

Level 1.b—Systematic review of RCTs and other study designs

Level 1.c—RCT

Level 1.d—Pseudo‐RCTs

Level 2 Quasi‐experimental designs

Level 2.a—Systematic review of quasi‐experimental studies

Level 2.b—Systematic review of quasi‐experimental and other lower study designs

Level 2.c—Quasi‐experimental prospectively controlled study

Level 2.d—Pretest–post‐test or historic/retrospective control group study

Level 3 Observational–analytical designs

Level 3.a—Systematic review of comparable cohort studies

Level 3.b—Systematic review of comparable cohort and other lower study designs

Level 3.c—Cohort study with control group

Level 3.d—Case–controlled study

Level 3.e—Observational study without a control group

Level 4 Observational–Descriptive studies

Level 4.a—Systematic review of descriptive studies

Level 4.b—Cross‐sectional study

Level 4.c—Case series

Level 4.d—Case study

Level 5 Expert Opinion and Bench Research

Level 5.a—Systematic review of expert opinion

Level 5.b—Expert consensus

Level 5.c—Bench research/single expert opinion

Levels of evidence for meaningfulness

1. Qualitative or mixed‐methods systematic review

2. Qualitative or mixed‐methods synthesis

3. Single qualitative study

4. Systematic review of expert opinion

5. Expert opinion

2.1. Population/Participants

The review included studies involving women who had had a caesarean birth (planned or unplanned) and had healthy term babies. Participants also included those who provided breastfeeding interventions to these women, such as health professionals, breastfeeding specialists, and significant supporters if their experiences and perceptions in relation to the breastfeeding intervention were recorded.

2.2. Interventions/Phenomena of interest

Studies included were those with interventions aimed at improving the initiation and continuation of any or exclusive breastfeeding targeted at women who had experienced a caesarean birth. Interventions commencing from the time of birth and/or postnatal period were included but not those implemented in the antenatal period unless reported as part of a “package” of care, which included specific postnatal interventions. Interventions implemented by healthcare professionals, breastfeeding specialists, or peer supporters, which could include education, physical care, or use of equipment (such as support for breast pumping), were included as were interventions that addressed training needs of supporters.

2.3. Comparison/Context

Studies undertaken in acute and/or primary care settings in high‐income countries as defined by the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2014) were included. For experimental studies, comparison could involve usual care or a control group that was designed as a comparison to a study's proposed intervention.

2.4. Outcomes

Primary outcomes:

Rates of initiation of breastfeeding

Duration of exclusive breastfeeding

Duration of any breastfeeding

Secondary outcomes:

Maternal and infant physical and psychological health (e.g., readmission to hospital)

Women's confidence, knowledge, attitudes, and skills

Staff knowledge, attitudes, and skills

Women's experiences of support (professional and peer) for breastfeeding

Impact on healthcare resources

Breastfeeding problems

Barriers to provision of interventions

Views of women's key supporters, for example, partners and close family members

To examine the evidence regarding interventions to support breastfeeding outcomes following caesarean birth, specific review questions were developed:

2.5. Primary question

What interventions support initiation and duration of exclusive or any breastfeeding following a planned or unplanned caesarean birth?

2.6. Secondary questions

-

Can interventions to support breastfeeding following a caesarean birth

improve maternal and infant physical and psychological health including prevention of readmission to hospital following initial postnatal discharge?

enhance women's confidence, knowledge, attitudes, and skills in breastfeeding?

enhance staff knowledge, attitudes, and skills in breastfeeding?

enhance women's experiences of support (professional and peer) for breastfeeding?

impact on healthcare resources?

reduce breastfeeding problems?

Are there specific barriers to implementation of interventions to support breastfeeding outcomes after a caesarean birth?

What are the views of women's key supporters, for example, partners and close family members with respect to interventions to support breastfeeding following a caesarean birth?

Papers that incorporated evidence to address primary and/or secondary questions of interest were included in the review if they met all review criteria.

2.7. Search strategy

A search strategy was developed to identify published papers. Papers were restricted to those published in English. A three‐step strategy was utilized. In the first stage, optimal search terms were identified using CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Maternity and Infant Care. Keywords and index terms were then searched using the following databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Maternal & Infant Care, Scopus, PsycINFO, British Nursing Index, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. The third stage involved searching the reference list of identified papers for additional papers and unpublished research and reports published in grey literature from sources including British Library EThOS, Opendoar, Open Grey, NHS Evidence, ProQuest, and WorldCat. Websites of national breastfeeding organizations were also searched.

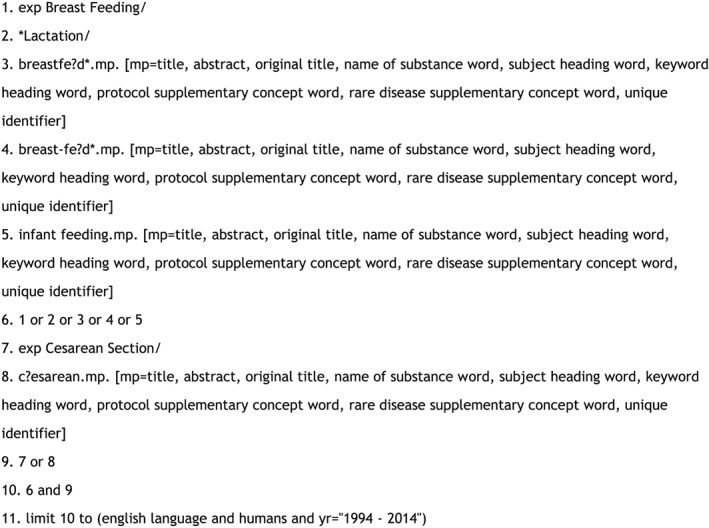

Initial keywords and index terms included breast feeding, lactation, infant feeding, breastmilk, and caesarean/cesarean. Studies published in the English language from January 1994 following introduction of the global UNICEF Baby Friendly Initiative to February 2016 were searched. Papers representing quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods research, and systematic/literature reviews were included. Studies contained within systematic reviews were not included separately as part of this review. Opinion pieces were excluded as were guidelines and policy papers as they were unlikely to report thoroughly the research design and/or outcomes of empirical research. Studies of breastfeeding support interventions for all women, irrespective of the mode of birth, were excluded unless outcomes for women who had a caesarean birth were reported separately. Studies that only focused on breastfeeding of babies who were premature or admitted to neonatal care were excluded. An example of an electronic search is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Electronic search strategy (Medline)

All identified papers were initially assessed for relevance based on the title and then further assessed from reading the abstract. Following the initial assessment, two reviewers (SB, Y‐SC) independently assessed the papers against the inclusion criteria and for methodological validity using standardized critical appraisal instruments. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (DB).

2.8. Quality appraisal

Critical appraisal tools developed by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme were used for quality assessment, using the appropriate checklist depending on the study methodology. There was no suitable Critical Appraisal Skills Programme appraisal checklist for one paper, and in this case, a checklist designed for quantitative observational studies based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement was used (Barley, Murray, Walters, & Tylee, 2011).

As papers that met the inclusion criteria used a range of research approaches and only a small number of relevant papers were identified, a decision was made to not exclude any following quality assessment. However, the quality assessment score for each paper is presented (Table 1) to demonstrate the strength of the quality for each paper. Following the Joanna Briggs Institute review development guidance, papers were assigned levels of evidence, based on the study design to provide an estimate of “trustworthiness” for the review (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014).

Table 1.

Summary of papers included in the review

| Study | Intervention type | Study sample | Aims of study | Methodology | Outcome measures | Important results | Critical appraisal scorea & level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brady et al., 2014 (USA) | Early SSC | All staff/eligible mother/infant couplets in a maternity unit of approximately 1,200 mother/infant couplets | To implement SSC for all eligible mother/infant couplets after CS in the operating room | Quality improvement project | SSC implemented in the operating room. | In first month, 43% of women undergoing a CS experienced SSC in the operating room; after 10 months >70% experienced this. In the year prior to implementation, 9% of infants born by CS were exclusively breastfeeding on discharge. After 10 months, 19% were exclusively breastfed on discharge. | Observational checklist (seven questions, Barley et al., 2011): 5/7 = Yes 1/7 = N/A 1/7 = No |

| Increase exclusive breastfeeding rates at discharge | Level of evidence for effectiveness: 4d | ||||||

| Chapman et al., 2001 (USA) | Breast pumping; electric pump for ×6 sessions each 10–15 mins | Intervention group: 30 women, control group: 30 women | 1. To measure impact of increased breast stimulation via breast pumping on breast milk transfer during the first 72 hrs after CS 2. To investigate potentially dormant effects of breast pumping before onset of lactation, including effects on milk transfer during first 2 weeks after birth and subsequent breastfeeding duration | RCT | Milk transfer (by test weighing) | Breast pumping between 24 and 72 hrs after CS did not improve milk transfer. Participants in the pumping group tended to have lower milk transfer than in the control group. Primipara in pumping group breastfed for 5 months less than their counterparts in the control group; however, this difference was not statistically significant. | *CASP RCT checklist of 11 questions: 5/11 = Yes 2/11 = Can't tell 4/11 = No |

| Level of evidence for effectiveness: 1c | |||||||

| Chertock, 2006 (Israel) | Post CS breastfeeding assistance and guidance along with early post‐CS maternal–infant contact | Intervention group: 306 women (Muslim 101 and Jewish 205) control group: 264 women (93 Muslim and 171 Jewish) | 1. To examine post‐CS breastfeeding rates at discharge, 10 and 16 weeks postpartum

2. To decrease the time lapsing from CS to maternal–infant contact, thereby increasing early post‐CS infant holding and breastfeeding initiation in the intervention group as compared with the control group 3. To increase post‐CS breastfeeding rates in the intervention group as compared with the control group |

Prospective population based, none randomized, evaluation | Hold infant early post‐CS period (0–4 hrs).

Breastfeeding initiation. Breast feeding early post‐CS period (0–4 hrs) |

Timing of post‐CS maternal–infant contact and breastfeeding initiation outcomes for Jewish and Muslim women statistically significantly improved following the intervention. | CASP cohort study checklist of 10 questions: 4/10 = Yes 4/10 = Can't tell 2/10 = No |

| Level of evidence for effectiveness: 3c | |||||||

| Chertock & Shoham‐Vardi, 2004 (Israel) | 1. Breastfeeding education prior to elective CS when possible

2. Bringing the infant to interested and non‐sedated mother in the post‐CS recovery room for immediate post‐CS holding and/or breastfeeding 3. Providing support and assistance with positioning and latching 4. Continuing follow‐up breastfeeding support throughout the hospital stay. A goal for the intervention was to bring infants to their mothers during the first 4 hrs |

Intervention group: 306 women (Muslim 101 and Jewish 205) control group: 264 women (93 Muslim and 171 Jewish) | 1. To examine post‐CS breastfeeding rates at discharge, 10 and 16 weeks postpartum

2. To decrease time lapsing from CS to maternal–infant contact, thereby increasing early post‐CS infant holding and breastfeeding initiation in the intervention group as compared with the control group, 3. To increase post‐CS breastfeeding rates in the intervention group as compared with the control group |

Prospective population based, none randomized, evaluation | Overall and exclusive breastfeeding at 10 weeks.

Overall and exclusive breastfeeding at 16 weeks |

Overall and exclusive 4‐month breastfeeding duration rates were statistically significantly higher for the intervention group as compared with the control group for the Jewish women at 10 and 16 weeks postpartum. Because few Muslim women ceased breastfeeding, only exclusive breastfeeding rates were evaluated. At 10 and 16 weeks, significantly more Muslim women in the intervention group were exclusively breastfeeding as compared with the control group, although rates dramatically declined by 16 weeks. | CASP cohort study checklist of 10 questions: 7/10 = Yes 3/10 = No |

| Level of evidence for effectiveness: 3c | |||||||

| Moran‐Peters et al., 2014 (USA) | SSC | six women | To evaluate the implications of unavailability of SSC following a CS and to identify perceptions of women who performed SSC after their second CS, particularly related to facilitation of breastfeeding in order to compare CS experiences in which SSC was and was not present | A Quality Improvement project. (Qualitative) | Not applicable | Two main themes from analysis: (a) Mothers' relationships with their newborns and (b) mothers' experiences with breastfeeding.

Overall, the women reported a better experience with the most recent CS because of contact with the baby. They also had a better breastfeeding experience. |

CASP qualitative research checklist of 10 questions:

9/10 = Yes 1/10 = Can't tell |

| Level of evidence for meaningfulness: 3 | |||||||

| Stevens et al., 2014 (USA & Europe) | Early SSC | Seven papers included, small sample sizes in individual papers | To evaluate existing evidence on the facilitation of immediate or early (within 1 hr) SSC following CS for healthy term newborns and identify facilitators, barriers, and associated maternal and newborn outcomes | Literature review | Implementation of immediate or early SSC in operating theatre, mother/newborn emotional well‐being, parent/newborn communication, maternal pain, and newborn feeding outcomes. | With appropriate collaboration SSC during CS, surgery can be implemented. Limited evidence that immediate or early SSC after CS may increase breastfeeding initiation, decrease time to the first breastfeed, reduce formula supplement in hospital, increase bonding and maternal satisfaction, maintain the temperature of newborns, and reduce newborn stress. | CASP systematic review checklist of 10 questions:

9/10 = Yes 1/10 = Can't tell |

| Level of evidence for effectiveness: 1b | |||||||

| Tully & Ball, 2012 (UK) | Sidecar bassinet on postnatal unit | 20 dyads allocated to sidecar bassinet, 15 dyads allocated stand alone. | To test the effect of the sidecar bassinet on postnatal unit breastfeeding frequency and other maternal–infant behaviors compared with the stand‐alone bassinet following CS | Randomized trial with a parallel design | Infant location, bassinet acceptability, breastfeeding frequency, breastfeeding effort, maternal–infant contact, sleep states, midwife presence, and infant risk | Differences in breastfeeding frequency, maternal–infant sleep overlap, and midwife presence not statistically significant. The 20 dyads allocated to sidecar bassinets breastfed a median of 0.6 bouts per hour compared with 0.4 bouts per hour for the 15 stand‐alone bassinet dyads. Participants in the intervention group expressed overwhelming preference for the sidecar bassinets. Bed sharing was equivalent between the groups, although the motivation for this practice may have differed. Infant handling was compromised with stand‐alone bassinet use, including infants positioned on pillows while bed sharing with their sleeping mothers. | CASP RCT checklist of 11 questions: 6/11 = Yes 2/11 = Can't tell 3/11 = No |

| Level of evidence for effectiveness: 1c |

Highest level of quality met when “Yes” answered for all included questions.

CASP = Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; CS = caesarean birth; SCC = skin‐to‐skin contact; RCT = randomized controlled trials.

Only two included studies were randomized controlled trials (RCT), which considered different interventions, meaning data could not be statistically combined for a meta‐analysis. Data were therefore synthesized into a narrative summary, with main data extracted and presented in Table 1, by one reviewer (SB) and checked by a second (Y‐SC).

3. RESULTS

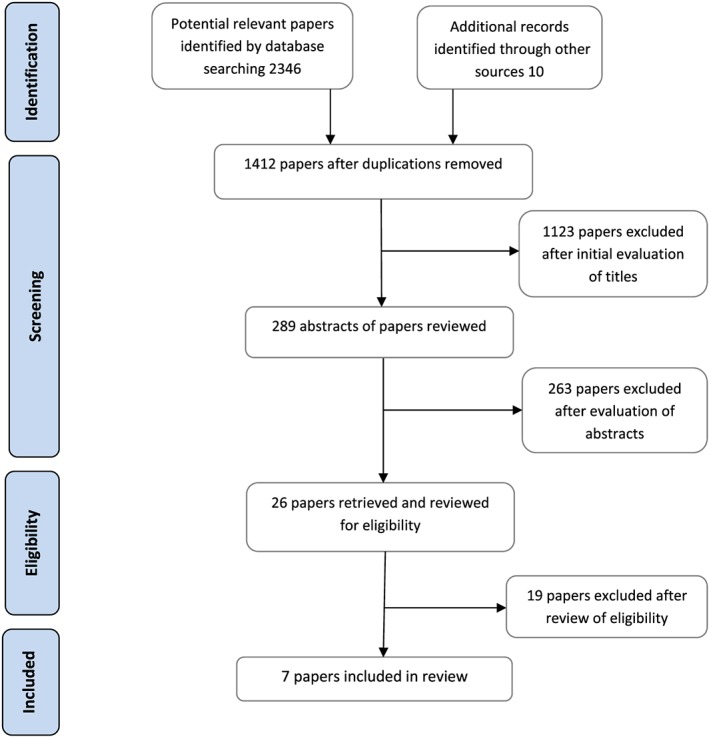

A total of 2,346 papers were identified from the initial search. After removing duplicates, 1,412 papers remained. The titles of these papers were assessed for relevance after which 289 papers were initially considered (Figure 2). Abstracts were independently assessed by two reviewers (SB and Y‐SC) to see if they met review inclusion criteria. The full texts of 26 papers were retrieved and assessed further to confirm if they were eligible for inclusion, following which 19 papers were excluded that did not address any of the primary or secondary questions or were incorporated in an included review paper (n = 3) (Stevens, Schmied, Burns, & Dahlen, 2014). The reference lists of retrieved papers were searched for possible further relevant papers; however, no further papers were identified. The remaining seven papers were appraised using the appropriate checklist for the type of study under consideration. The number of possible criteria to meet varied depending on the study design checklist, with most scoring 8 or 9 out of a possible 10 or 11 criteria (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of stages of searching

The seven papers included one narrative literature review (Stevens et al., 2014), four primary research papers (Chertock, 2006; Chertock & Shoham‐Vardi, 2004; Tully & Ball, 2012; Chapman, Young, & Pere‐Escamilla, 2001), and two quality improvement projects (Brady, Bulpitt, & Chiarelli, 2014; Moran‐Peters, Zauderer, Goldman, Baierlein, & Smith, 2014). All referred to care in high‐income country settings.

The papers were assessed for levels of evidence (Box 1) to consider the effectiveness of interventions or meaningfulness of qualitative studies based on the study design rather than the quality that was assessed during the critical appraisal process. Three of the papers (Chapman et al., 2001; Stevens et al., 2014; Tully & Ball, 2012) were assessed as level one studies (the highest level of evidence), although one (Chapman et al., 2001) scored poorly during the critical appraisal process, and in another paper, (Tully & Ball, 2012) the results were underpowered as a substantial number of women were excluded following recruitment. Three further papers (Chertock, 2006; Chertock & Shoham‐Vardi, 2004; Moran‐Peters et al., 2014) were assessed as level three and one as level four (Brady et al., 2014) (Table 1).

Few postnatal interventions specifically targeted women who had a caesarean birth with the primary aim of increasing breastfeeding and/or duration of any or exclusive breastfeeding. Interventions identified included immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact (Brady et al., 2014; Moran‐Peters et al., 2014; Stevens et al., 2014), education and breastfeeding support (Chertock, 2006; Chertock & Shoham‐Vardi, 2004), the use of sidecar bassinets when rooming‐in, (Tully & Ball, 2012) and use of breast pumps (Chapman et al., 2001). A summary of included papers is included in Table 1.

The results presented below reflect interventions investigated in each included paper relevant to the primary and/or secondary questions of this review.

3.1. Immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact after a caesarean birth

A narrative literature review (Stevens et al., 2014) and two quality improvement (QI) projects (Brady et al., 2014 and Moran‐Peters et al., 2014), both implemented in North American settings, considered immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact (SSC) after a caesarean birth. The main focus of these papers was the feasibility of introducing immediate or early SSC following surgery with data on breastfeeding outcomes also included.

Stevens et al.'s (2014) narrative literature review included seven papers published from 2003 to 2013 (Gouchon et al., 2010; Nolan & Lawrence, 2009; Velandia, Matthisen, Uvnäs‐Moberg, & Nissen, 2010; Crenshaw et al., 2012; Finigan & Davies, 2004; Hung & Berg, 2011; Velandia, Uvnäs‐Moberg, & Nissen 2012). Three of these studies were from the USA and the remaining four from Europe. There was wide study heterogeneity. Individual studies were methodologically poor, and most had small sample sizes (ranging from 6 to 50). Although the majority of papers provided some data on breastfeeding and formula feeding outcomes (which generally showed an increase in breastfeeding initiation and reduced formula supplementation), evidence of benefit was inconclusive. There was some evidence that it was possible to commence SSC immediately following a caesarean section but limited evidence that SSC increased bonding and maternal satisfaction, maintained the temperature of new born babies, or reduced infant stress.

Brady et al.'s QI project (Brady et al., 2014) was conducted in a community teaching and referral unit in the USA, which provided care for around 1,200 women and their babies each year. It was unclear from the data presented what percentage of these women had a caesarean birth. Prior to the QI project, usual practice at the study site was for SSC to be initiated in a post anaesthesia care unit. The plan, do, study, act approach was used to implement an intervention to assess the introduction of SSC in the operating theatre during the surgery. SSC was successfully implemented with an increase from the first month of full implementation from 43% of women to over 70% of women 10 months later. The increase in exclusive breastfeeding rates during the same period varied month by month from under 10% to just over 20%. In the year before implementation of SSC, the exclusive breastfeeding rate on discharge from hospital was 9%.

Moran‐Peters et al. (2014) carried out a QI project also in the USA, in a 400‐bed general community hospital with approximately 1,500 births a year and a high caesarean rate (42%). This project focused on women's perceptions of the benefits of SSC and included a purposive sample of six women who had at least one previous caesarean birth who were asked to compare their previous caesarean birth experience with their index pregnancy and birth by caesarean, which included early SSC (defined as contact within 2 hr of birth). Previous standard practice at this hospital had been for babies born by caesarean to be separated from their mothers and taken to the nursery for assessment and bathing, following which they were transferred back to their mothers on the postnatal ward. Two main themes were identified: women's relationships with their infants and women's experiences with breastfeeding. Overall, the women reported a more positive breastfeeding experience due to earlier contact with their baby and a calmer, more relaxed approach to breastfeeding enabling the baby to “latch” better. Study limitations included potential recall bias in terms of comparison of previous experiences, reasons for having a first caesarean birth, timing of questions, and the very small sample size. The authors also acknowledged the limitations of only including women who had had two caesarean births meaning that few women met the study inclusion criteria, although they reported that data saturation was achieved.

3.2. Education and breastfeeding support in the early postnatal period

Two papers presented data from the same study on initiation and duration of breastfeeding to 4 hr postnatally following caesarean birth (Chertock, 2006; Chertock & Shoham‐Vardi, 2004). The intervention implemented included four components: (a) antenatal education on breastfeeding where possible prior to a planned caesarean, (b) early contact and/or breastfeeding in the recovery room (during the first 4 hr), (c) support and assistance with positioning and attachment of the infant on the breast, and (d) continued follow‐up breastfeeding support throughout the hospital stay. The study, a prospective non‐randomized evaluation, took place in a university medical centre in Israel with approximately 12,000 births a year and included 306 women in the intervention (101 Muslim and 205 Jewish) and 264 in the control group (93 Muslim and 171 Jewish). Due to the difference in availability of research assistants from the two communities, a higher number of Jewish women were approached on the ward than Muslim women, potentially explaining why a higher number of Jewish women were included, although the overall refusal rate was actually higher for Jewish women (12%) than Muslim women (1%). As breastfeeding practices are influenced by social and cultural influences, outcomes among these two groups were presented separately. Interviews were conducted in hospital prior to inpatient discharge and follow‐up phone calls were made at 10 and 16 weeks postnatally.

Most Muslim women (94%) had a general anesthetic for their caesarean birth compared with just over half (59%) of the Jewish women. A third (28%) of caesarean births among Muslim women were planned, compared with just under half (46%) for Jewish women. Reasons for these differences were not described. Breastfeeding initiation rates (initiation was described as “ever breastfed the infant”) were statistically significantly higher in the intervention groups than control groups (Muslim women p < 0.05 [100% vs. 95%], Jewish women p < 0.01[98% vs. 90%]). The overall breastfeeding rates at 10 and 16 weeks for Jewish women in the intervention group were significantly higher than in the control group (p = 0.04 [68% vs. 57%] and p = 0.002 [59% vs. 42%], respectively), with no differences in overall breastfeeding rates found between Muslim women in the intervention and control groups at either follow‐up time, due to the high percentage of women in the control group who continued to breastfeed (97% and 96%, respectively). There were statistically significant differences in exclusive breastfeeding rates at 10 and 16 weeks in the intervention groups; Jewish women (p = 0.001 [49% vs. 32%] at 10 and p = 0.001 [34% vs. 18%] at 16 weeks) and in Muslim women (p = 0.046 [49% vs. 31%] at 10 weeks and p = 0.001 [31% vs. 7%] at 16 weeks). Muslim women in the control group introduced formula supplements significantly earlier than the other groups. Of note was the higher study dropout rate among Muslim women (56% were followed up to 16 weeks compared with 94% of Jewish women). Reasons postulated for this included women's lack of access to a telephone and phone disconnected or not answered.

3.3. The use of sidecar bassinets during inpatient rooming‐in

Tully and Ball (2012) in a randomized trial looked at the use of sidecars (three‐sided bassinets that locked onto the woman's bed) after a planned caesarean birth. The trial took place in a tertiary maternity unit in the north of England with approximately 5,400 births a year. Mother and baby interactions were filmed on the second postpartum night and semi‐structured interviews with women conducted before and after the filming. Main outcome measures included infant location, acceptability of the bassinet to women, and breastfeeding frequency. Women were recruited antenatally and randomized into either a sidecar or stand‐alone bassinet, with a sample size of 72 required to detect a group difference in breastfeeding frequency. A total of 86 women were recruited, but sufficient video observations to analyze were only collected from 35 maternal and baby interactions. There was no significant difference between breastfeeding frequency, maternal–infant sleepover and midwifery presence, although more women allocated to the sidecar bassinet group expressed a preference for this model of bassinet than the women allocated to the stand alone bassinet. Reasons included that it was easier to get to and visualize their infants and they would not have managed to breastfeed without it.

3.4. Use of breast pumping

A small trial from the USA (Chapman et al., 2001) investigated the impact of breast pumping between 24 and 72 hrs after a planned or unplanned caesarean birth using a double electric breast pump three times a day, for 10 to 15 min after a breast feed, over 2 days. Study objectives were to measure the impact of increased breast stimulation on milk transfer during the first 72 hrs and investigate the potentially dormant effects of breast pumping prior to the onset of lactation on milk transfer during the first 2 weeks postnatally and duration of subsequent breastfeeding. To assess if there was additional milk transfer as a result of breast pumping, babies were test weighed before and after three breastfeeds each day.

Sixty women were randomly assigned to either the pumping intervention group or the control group. Those in the control group (n = 30) held the pump to their breasts, without the suction under the constant supervision of research staff, for the same amount of time as the intervention group (n = 30). Randomization was stratified by parity and planned or unplanned caesarean to ensure an even distribution between the two groups. Breast pumping did not improve milk transfer with women in the pumping group tending to have lower milk transfer than those in the control group, and no significant difference in exclusive or any breastfeeding outcomes at seven to 10 days or at 5 months. The authors proposed several hypotheses for this, including a possible increase in stress hormones for those pumping and a lack of evidence of whether the hormonal response to breast pumping resembles breastfeeding stimulation during first 72 hrs postnatally. Other hypothesis considered included that pumping could reduce the frequency and duration of breastfeeding, although the authors did not report that this was a finding in their sample. Given the small amounts of milk “re‐fed” and that test weighing for consecutive feeds was avoided, it was considered unlikely that this could have decreased later milk intake. Another possibility considered by the authors was whether by delaying pumping until 24 hrs postnatally they had missed a crucial time for breast stimulation, although evidence of this was not collected as part of the study.

4. DISCUSSION

Breastfeeding initiation and rates of exclusive or any breastfeeding at 6 months are lower in women who have a caesarean birth, indicating the importance of robustly evaluated interventions to support women who want to breastfeed (Prior et al., 2012). This review identified very few interventions to specifically support breastfeeding among women who had a caesarean birth, despite this being a population with a potentially greater risk of poorer longer‐term maternal and infant health outcomes. The lack of evidence was particularly surprising given the high proportion of woman in high‐income countries who have a caesarean birth and availability of international and national policy and guidance on interventions to support successful breastfeeding (World Health Organisation/UNICEF, 2003; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006; Kramer & Kakuma, 2012). Apart from early SSC, few other interventions were identified. Most studies were small with data collected from a single study site, and none included longer‐term follow‐up beyond 4 months of the birth. Only two studies were randomized trials, neither of which was of high quality. One (Chapman et al., 2001) had a small sample size, and the other (Tully & Ball, 2012) was not powered to detect differences in outcomes of interest.

Three of the four interventions considered in this review comprised studies that included findings on initiation or duration of breastfeeding. Most studies showed no statistically significant increase in the outcomes of interest. Only Chertock's study (Chertock & Shoham‐Vardi, 2004; Chertock, 2006), which compared a “package” of interventions with usual care, showed any significant improvement in breastfeeding outcomes but was limited by methodological issues. Nevertheless, plans for infant‐feeding women may make during pregnancy (if a planned caesarean birth) and after giving birth are likely to be influenced by a range of complex factors (McAndrew et al., 2012). As such intervention, “packages” that reflect planned or unplanned caesarean birth (Hobbs et al., 2016) may be more likely to have an influence on breastfeeding outcomes following a caesarean birth rather than a single intervention.

Stevens et al's narrative review (Stevens et al., 2014) and Brady et al's QI project (Brady et al., 2014) found limited evidence that immediate or early SSC after a caesarean birth increased breastfeeding initiation. The main aim of the review by Stevens' et al. was facilitation of immediate or early SSC, with some evidence from the included studies to support the value of SSC, with findings supported by Brady et al.’s (2014) QI project. The women in Moran‐Peter et al's (Moran‐Peters et al., 2014) QI project reported better breastfeeding experiences following an intervention to support SSC, although the study was very small (n = 6) and patient inclusion criteria was restrictive, limiting the generalizability of the findings.

In terms of a supportive physical environment to enable women to breastfeed, despite the women in the study by Tully and Ball (2012) reporting that they liked the sidecar attached to their beds, impacts on breastfeeding frequency outcomes were not statistically significant. The use of breast pumping (Chapman et al., 2001) did not impact on outcomes of exclusive or any breastfeeding, and although not statistically significant at 5 months postnatally, fewer primiparous women in the pumping group were still breastfeeding compared with the control group. The study authors suggested that better understanding of the hormonal impact of breast pumping on milk transfer was needed. However, these studies lacked power to show any statistically significant difference in outcomes and further research is needed.

Robust evidence of the impact of a caesarean birth on lactogenesis and on women's postoperative physical and psychological recovery and ability to care for their infants is also urgently needed. There is a move now for women to be discharged earlier from inpatient care, with an inpatient duration of around 48 hr following a caesarean birth among women in the UK not uncommon (Wrench et al., 2015), following policy recommendations for management of planned surgery (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2008). The impacts of earlier hospital discharge on women's ability to breastfeed especially with the increased use of medication to expedite postoperative recovery in an environment where support for breastfeeding may not be offered consistently is as yet unknown.

In conclusion, despite increases in caesarean birth rates in high‐income countries, very few interventions were identified that specifically targeted additional support for women who wished to breast feed. Of interventions which were assessed, poor study methods, small sample sizes, and lack of longer‐term follow‐up limit the generalizability of findings. Given the lack of robust evidence, there is a need for large scale randomized controlled trials of interventions to support this group of women. However, before future trials are conducted, we need evidence of what interventions or package of interventions could potentially provide the most benefit for women undergoing planned or unplanned caesarean birth.

4.1. LIMITATIONS

Limitations of the review process include exclusion of non‐English language studies and studies from low and middle‐income countries, which could have introduced selection bias. The poor quality of studies and lack of “gold standard” randomized controlled trials also means that potential risk of bias with particular respect to selection, attrition, and reporting of outcomes cannot be excluded. The paucity of well‐conducted, large primary studies, with planned longer‐term follow‐up and assessment, limits the generalizability of the review findings. Strengths of the review include a comprehensive search strategy that was developed and implemented to identify all relevant evidence to address our primary and secondary questions. Relevant studies were included that used quantitative and qualitative approaches to data capture, which were subject to rigorous critical review and appraisal in order to meet planned aims and objectives.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

The research was supported by a Transitional Research Grant from Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust. CN was supported by King's Experience 2014 scheme awarded by King's College London as an Undergraduate Research Fellow. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

CN, DB and Y‐SC developed the review questions. CN and SB conducted the search. SB and Y‐SC assessed all the selected text papers for eligibility. SB produced the initial draft of the paper and revised the paper following feedback from DB and Y‐SC. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their thanks to Professor Virginia Schmied and Dr Elsa Montgomery who commented on the review protocol. Y‐SC and DB are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Beake S, Bick D, Narracott C, Chang Y‐S. Interventions for women who have a caesarean birth to increase uptake and duration of breastfeeding: A systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2017;13:e12390 10.1111/mcn.12390

REFERENCES

- Aune, D. , Norat, T. , Romundstad, P. , & Vatten, L. J. (2014). Breastfeeding and the maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose‐response meta‐analysis of cohort studies. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases, 24, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, D. L. , Wu, K. M. , & Tarrant, M. (2013). Association between intrapartum interventions and breastfeeding duration. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 58(1), 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barley, E. A. , Murray, J. , Walters, P. , & Tylee, A. (2011). Managing depression in primary care: A meta‐synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research from the UK to identify barriers and facilitators. BMC Family Practice, 12(47). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowatte, G. , Tham, R. , Allen, K. J. , et al. (2015). Breastfeeding and childhood acute otitis media: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica. Supplement, 104, 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady, K. , Bulpitt, D. , & Chiarelli, C. (2014). An interprofessional quality improvement project to implement maternal/infant skin‐to‐skin contact during cesarean delivery. JOGNN, 43(4), 488–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. , & Jordan, S. (2013). Impact of birth complications on breastfeeding duration: An internet survey. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(4), 828–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo A., Cogoy L., Macaluso A. & Tamburlini G. (2012) Child health in the European Union . WHO Collaborating Centre for Maternal and Child Health, Trieste, Italy.

- Chapman, D. J. , Young, S. A. M. , & Pere‐Escamilla, R. (2001). Impact of breast pumping on lactogenesis stage II after Cesarean Delivery: A randomised control trial. Pediatrics, 107, e94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chertock, I. R. (2006). Breast‐feeding initiation among post‐caesarean women of the Negev, Israel. British Journal of Nursing, 15(4), 205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chertock, I. R. , & Shoham‐Vardi, I. (2004). Four‐month breastfeeding duration in post cesarean women of different cultures in the Israeli Negev. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 18(2), 145–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, R. , Sinha, B. , Sankar, M. J. , Taneja, S. , Bhandari, N. , Rollins, N. , … Martines, J. (2015). Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica. Supplement, 104, 96–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, J. , Cadwell, K. , Brimdyr, K. , Widström, A. , Svensson, K. , Champion, J. , … Winslow, E. (2012). Use of a video‐ethnographic intervention (PRECESS Immersion Method) to improve skin‐to‐skin care and breastfeeding rates. Breastfeeding Medicine, 7, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finigan, V. , & Davies, S. (2004). ‘I just wanted to love, hold him forever’: Women's lived experience of skin‐to‐skin contact with their baby immediately after birth. Evidence Based Midwifery, 2, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Giugliani, E. J. , Horta, B. L. , de Mola, C. L. , Lisboa, B. O. , & Victora, C. G. (2015). Effect of breastfeeding promotion interventions on child growth: A systematic review and meta‐analyses. Acta Paediatrica. Supplement, 104, 20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouchon, S. , Gregori, D. , Picotto, A. , Patrucco, G. , Nangeroni, M. , & Di Giulio, P. (2010). Skin‐to‐skin contact after cesarean delivery: An experimental study. Nursing Research, 59, 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Social Care Information Centre . (2015). NHS Maternity Statistics—England, 2013–2015. Available at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB16725/nhs-mate-eng-2013-14-summ-repo-rep.pdf (accessed 21 October 2015).

- Hobbs, A. J. , Mannion, C. A. , McDonald, S. W. , Brockway, M. , & Tough, S. C. (2016). The impact of caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-016-0876-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta, B. L. , & Victora, C. G. (2013). Short‐term effects of breastfeeding: A systematic review of the benefits of breastfeeding on diarrhoea and pneumonia mortality. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, B. L. , de Mola, C. L. , & Victora, C. G. (2015). Long‐term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure, and type‐2 diabetes: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica. Supplement, 104, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung, K. , & Berg, O. (2011). Early skin‐to‐skin after cesarean to improve breastfeeding. MCN. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 36, 318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip, S. , Chung, M. , Raman, G. , Trikalinos, T. A. , & Lau, J. (2009). A summary of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Evidence Report on Breastfeeding in Developed Countries. Breastfeeding Medicine, 4(Supp 1), S17–S30. DOI: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain, L. , & Eaton, D. C. (2006). Physiology of fetal lung fluid clearance and the effect of labor. Seminars in Perinatology, 30(1), 34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanna Briggs Institute . (2014). Reviewer's manual. Joanna Briggs Institute. Available at http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/ReviewersManual-2014.pdf (accessed 11 July 2016)

- Karlström, A. , Engström‐Olofsson, R. , Norbergh, K. G. , Sjöling, M. , & Hildingsson, I. (2007). Postoperative pain after cesarean birth affects breastfeeding and infant care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 36(5), 430–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolås, T. , Saugstad, O. D. , Daltveit, A. K. , Nilsen, S. T. , & Øian, P. (2006). Planned cesarean versus planned vaginal delivery at term: Comparison of newborn infant outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 195(6), 1538–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil, K. B. , Jou, J. , Attanasio, L. B. , Joarnt, L. K. , & McGovern, P. (2014). Medically complex pregnancies and early breastfeeding behaviours: A Retrospective Analysis. PloS One, 9(8), e104820 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M. S. , & Kakuma, R. (2012). Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (8) Art. No.: CD003517. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge, C. J. , Tan, D. J. , Lau, M. , Dai, X. , Tham, R. , Lowe, A.J. , Dharmage, S.C. (2015). Breastfeeding and asthma and allergies: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica. Supplement, 104, 38–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, E. , & Hughes, M. (2010). Breastfeeding experiences of mothers from disadvantaged groups: A review. Community Practitioner, 83(7), 30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKean G. & Spragins W. (2012). The challenges of breastfeeding in a complex world . A critical review of the qualitative literature on women and their partners'/supporters' perceptions about breastfeeding . Available at http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/ps-1029951-pregnancy-2012-breastfeeding-lit-review.pdf (accessed 05 September 2014)

- McAndrew F., Thompson J., Fellows L., Large A., Speed M. & Renfrew M. (2012). Infant feeding survey 2010: Summary . Health and Social Care Information Centre. Available at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB08694 (accessed 03 September 2014).

- McFadden, C. , Baker, L. , & Lavender, T. (2009). Exploration of factors influencing women's breastfeeding experiences following a caesarean section. Evidence Based Midwifery, 7(2), 64. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, R. J. , & Chambers, J. A. (2008). Supporting breastfeeding mothers: Qualitative synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(4), 407–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran‐Peters, J. A. , Zauderer, C. R. , Goldman, S. , Baierlein, J. , & Smith, A. E. (2014). A quality improvement project focused on women's perceptions of skin‐to‐skin contact after cesarean birth. Nursing for Women's Health, 18(4), 296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . (2006). Routine postnatal care of women and their babies. London: NICE. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement . (2008). Enhanced recovery programme . Available at http://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/quality_and_service_improvement_tools/enhanced_recovery_programme.html (accessed 22 July 2016).

- Nolan, A. , & Lawrence, C. (2009). A pilot study of a nursing intervention protocol to minimize maternal–infant separation after cesarean birth. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 38, 430–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology . (2002). Caesarean Sections . Available at http://www.parliament.uk/documents/post/pn184.pdf (accessed 28 September 2016).

- Prior, E. , Santhakumaran, S. , Gale, C. , Philipps, L. H. , Modi, N. , & Hyde, M. J. (2012). Breastfeeding after cesarean delivery: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of world literature. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 95(5), 1113–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, M. J. , McCormick, F. M. , Wade, A. , Quinn, B. , & Dowswell, T. (2012). Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (5) Art. No.: CD001141. DOI: 10.1002/1465188.CD001141.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmied, V. , Beake, S. , Sheehan, A. , McCourt, C. , & Dykes, F. (2009). A meta‐synthesis of women's perceptions and experiences of breastfeeding support. JBI Library of Systematic Reviews, 7(14), 583–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. A. , Binns, C. W. , & Oddy, W. H. (2007). Predictors of delayed onset of lactation. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 3(3), 186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J. , Schmied, V. , Burns, E. , & Dahlen, H. (2014). Immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact after a Caesarean section: A review of the literature. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 10, 456–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully, K. P. , & Ball, H. (2012). Postnatal unit bassinet types when rooming‐in after cesarean birth: Implications for breastfeeding and infant safety. Journal of Human Lactation, 28(4), 495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully, K. P. , & Ball, H. (2014). Maternal accounts of their breast‐feeding intent and early challenges after caesarean childbirth. Midwifery, 30(6), 712–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velandia, M. , Matthisen, A. , Uvnäs‐Moberg, K. , & Nissen, E. (2010). Onset of vocal interaction between parents and newborns in skin‐to‐skin contact immediately after elective cesarean section. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, 37, 192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velandia, M. , Uvnäs‐Moberg, K. , & Nissen, E. (2012). Sex differences in newborn interaction with mother or father during skin‐to‐skin contact after caesarean section. Acta Paediatrica, 101, 360–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. D. , França, G. V. A. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Rollins, N.C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. S. , Zhou, L. F. , Zhu, L. P. , Gao, X. L. , & Gao, E. S. (2006). Prospective observational study on the effects of caesarean section on breastfeeding. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi, 41(4), 246–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . (2014). World Development Indicators. World Bank, Washington DC.

- World Health Organisation / UNICEF . (2003). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: Available at http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/global_strategy/en/ World health Organisation; (accessed 03 September 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wrench, I. J. , Allison, A. , Galimberti, A. , Radley, S. , & Wilson, M. J. (2015). Introduction of enhanced recovery for elective caesarean section enabling next day discharge: A tertiary centre experience. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia, 24, 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J. , Betran, A. P. , Guerrero, V. M. , Souza, J. P. , & Zhang, J. (2014). Searching for the optimal rate of medically necessary caesarean delivery. Birth, 41(3), 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]