Abstract

Abstract

We conducted 40 in‐depth interviews and eight focus groups among mothers and fathers (n = 91) of diverse ages in western Uganda to define the relevant domains of maternal capabilities and their relationship to infant and young child feeding practices. This study was directed by a developing theory of maternal capabilities that posits that the impact of health‐directed interventions may be limited by unmeasured and poorly understood maternal characteristics. Ugandan caregivers defined three major life events that constrain women's capabilities for childcare: early pregnancy, close child spacing, and polygamous marriage. Women describe major constraints in their decision‐making capabilities generally and specifically to procuring food for young children. Future nutrition programs may improve their impact through activities that model household decision‐making scenarios, and that strengthen women's social support networks. Findings suggest that efforts to transform gender norms may be one additional way to improve nutrition outcomes in communities with a generally low status of women relative to men. The willingness of younger fathers to challenge traditional gender norms suggests an opportunity in this context for continued work to strengthen resources for children's nutritional care.

Significance

Maternal factors such as autonomy are associated with child feeding practices and nutritional status, with varying degrees depending on the definition of maternal‐level constructs and context. This study describes the events and processes that constrain maternal capabilities—intrapersonal factors that shape mother's abilities to leverage resources to provide care to children—as they relate to nutrition and hygiene practices. We report community beliefs and understandings about which capabilities have meaning for child nutrition and hygiene, and develop a conceptual framework to describe how these capabilities are formed and describe implications for future nutrition programs in East Africa and similar settings.

1. INTRODUCTION

Aggressive efforts in nutrition interventions will be required to reach the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals under‐5 childhood mortality target of 25 per 1000 live births, especially in Sub‐Saharan Africa where the rate is 100 deaths per 1000 (UN IGME, 2015). Nutrition‐related factors contribute to 45% of these deaths (Black et al., 2013). Countries like Uganda have seen steady reductions in child mortality and the prevalence of stunting; however, the necessary child feeding practices to further reduce undernutrition have not improved in the past 10 years (Engebresten et al., 2007; Ickes, Hurst, & Flax, 2015).

Empowering women in the 34 countries that comprise over 90% of the global undernutrition burden is identified as a necessary strategy to further reduce under nutrition; however, understanding for how this cross‐cutting action will specifically translate to improving nutrition is still unclear (Ruel & Alderman, 2013). Empowerment is a process of expanding the assets and capabilities of poor people to negotiate with, influence, and hold accountable the institutions that affect their lives (Grootaert, 2003; Alkire & Ibrahim, 2007). Maternal capabilities, or the freedoms mothers experience within their social institutions, ultimately limit mother's abilities to leverage their resources and skills into child health (Sen, 1999).

Household and community‐level capabilities and the corresponding opportunity structure for women critically shape the stability of the food security, care, and health needed by mothers for adequate child feeding as well as mother's abilities to adopt essential interventions into the caregiving routine (Engle, Menon, & Haddad, 1999). For example, agency, a women's decision‐making power in household decisions, will affect her recruitment within the family for interventions that require lifestyle change. Cultural norms, when internalized, may create inaccurate self‐perceptions of mother's abilities to act (Malhotra, Schuler, & Boender, 2002).

A growing body of research links maternal agency or autonomy with child feeding, hygiene, and nutritional status, but we still lack a consistent definition of this construct (Carlson, Kordas, & Murray‐Kolb, 2015; Caruso, Stephenson, & Leon, 2010). In India, for example, a mother's position within her household is positively associated with children's nutritional status (Shroff et al., 2011; Sethuraman, Lansdown, & Sullivan, 2006). In Uganda, maternal mental health, literacy education, and health care access are linked to child feeding and nutritional status (Ashaba, Rukundo, Beinempaka, Ntaro, & LeBlanc, 2015; Ickes et al., 2015). Despite this, many nutrition programs overlook differences in the social contexts, responsibilities, and beliefs of the caregivers they serve (Kodish, Aburto, Hambayi, Kennedy, & Gittelsohn, 2015; Flax, 2015; Paul et al., 2011).

If social protection programs and policies can effectively modify unsupportive environments for girls and women, better understanding is needed of how women's caregiving capabilities influence nutrition and hygiene behaviors, and the processes that constrain these capabilities (Pelto, 1991). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to (a) define and understand the maternal capabilities in the Ugandan context that are relevant to the provision of child feeding and hygiene; and to (b) characterize how relationships and events in women's lives influence these capabilities and subsequent child care practices.

Key messages.

A guiding framework of maternal capabilities that describes how intrapersonal characteristics of mothers influence their abilities to provide nutritional care for children was understood by male and female Ugandan caregivers. Respondents explained the relationship between domains such as decision‐making and social support in relation to nutrition and hygiene care practices.

Early marriage, caring for closely spaced children, and being a co‐wife in a polygamous union are processes and life events that Ugandan caregivers describe as constraints to mother's capabilities of providing care to children.

Incorporating cultural knowledge about partner relationships and decision‐making patterns about reproductive health, food purchasing, and support for mothers by men and others in the community may be useful strategies for improving the impact of nutritional interventions.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study setting

The study was conducted in the Bundibugyo District of western Uganda. Bordered to the north by Lake Albert and to the west by the Democratic Republic of Congo, the 261,000‐person district remains one of the most remote and impoverished in the country. In 2010, the region was partially electrified, and the first paved road was constructed in 2013. These developments have ushered in a slow trend towards peri‐urbanization, though the majority of the population relies on subsistence farming and a small cash crop market for cocoa and matooke. The national fertility rate of 6.2 live births per woman is the highest of any country in the East and Southern African region. In the western region, women give birth to a mean of 6.4 children; over a fifth (22.6%) of women begins childrearing before the age of 20 years. The stunting prevalence (height‐for‐age Z score < −2) is highest in the western region at 43.9%, compared with 32% nationally (UBOS & ICF International Inc., 2012). Women's access to education is poor: 20% of women receive no formal education, and 80% do not proceed past primary school (UBOS & ICF International Inc., 2012). Child feeding is traditionally done by women. Following an early diet or porridges and soft‐starchy foods, children are fed family foods by around 18 months. Meals consist of starch‐based “foods” such as maize porridge and matooke, and protein and lipid‐rich sauces such as groundnuts, bean, and dried fish (Ickes et al., 2015).

Bundibugyo inhabited by the Babwisi and the Bakonjo people groups, who represent the Batooro and Bwamba Kingdoms, respectively. Both groups speak Bantu‐derived languages. The society is patrilineal and patrilocal: land is primarily owned by men and inherited through male lines. Following marriage, couples typically settle near men's families. A clan structure, led by men and based on location of residence and family origin, orders the society. Marriage is recognized culturally and religiously. Marriage traditionally involves a bride price paid to a woman's family. Traditionally, a garden hoe or digging stick is given at marriage ceremonies to signify the replacement of lost labor as a girl leaves her family. The process of marriage was done historically both through arrangement and elopement (called Kuhaiya Mukali), and negotiated between families through a middleman (Kibonabuko for the Bakonjo and Mukwenda for the Babwisi) (Uganda Travel Guide). Polygynous marriage is common. The majority of residents in Bundibugyo are Christians, mainly in the Anglican and Catholic churches. There is a small Muslim, and African tradition religious population (United States Department of State, 2009).

2.2. Participants

We purposively sampled participants for in‐depth interviews and focus groups. We conducted four all‐female and four all‐male focus groups for a total of eight focus groups. To ensure that that the study sample had current or potential experience with providing child care, all participants were required to have a child under 3 years of age, or to be expecting child. To avoid potential conflict within households, we did not sample men and women from the same household. Participants were asked, if possible, to be interviewed in a private setting at their compounds or at the local health center (in the case of focus groups) to ensure protection. All participants were free to participate irrespective of their marital status. Participants were purposively sampled to achieve saturation of key themes (Ulin, Robinson, Tolley, & McNeil, 2002). As interviews progressed, we identified specific populations that were necessary to understand how cultural processes and factors affected capabilities (e.g., mothers who care for more than five children and younger mothers). Hence, we used the initial demographic questionnaire to ensure that study members reflected these groups.

2.3. Study procedures

Our study sampled households from three of the seven sub‐counties in Bundibugyo: Nyahuka, Busaru, and Ndugutu. The research team visited 10 villages and two peri‐urban centers. Participants were approached at their homes and at health centers by study staff, which included two researchers from the United States and three Ugandan research assistants. Participants were asked if they would be willing to participate in a study about men's and women's roles in caring for children in Bundibugyo. We explained that the study purpose was to “better understand social issues in the community and how they relate to children's nutrition, and to identify ways to improve the programs available for parents to care for children in this community.” Interviews ranged from 30 to 60 minutes; while the focus groups lasted approximately 75 minutes. To protect participant privacy, to build trust and rapport with study participants, confidentiality was provided to all participants (Baez, 2002). The interviewer ensured each caregiver that the information shared would be kept confidential, and that no names would be used in publishing the results, nor would anyone be able to determine who participated in the study based on the information shared and published. Caregivers in focus groups were encouraged to not to use individual names in their responses, and were instructed to not share the names of anyone in the focus group. Further participants were asked to share only the general topic of the discussion with others after the conclusion of the meeting. The consent process explained that if participants were uncomfortable at any time, we would stop the interview. We ensured all participants that their participation in the study would have no impact on future interactions with the health center, NGOs or any nutrition activity in the district. Each contributor was given a bag of dried beans (valued at $0.70 USD) for their participation. Interviews were conducted in English and translated to the preferred local language of the participant (Lubwisi or Lukonjo). Responses were back translated in English to the interviewer.

2.4. Data collection tools

All participants completed a demographic questionnaire, based on the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UBOS & ICF International Inc., 2012). Following the initial development of the interview and focus group guides, we spent 1 week revising and translating the guides in person as a research team in Uganda. This process involved discussions of ways to convey complex ideas and culturally‐constructed ideas such as empowerment, gender, and marriage. Semi‐structured interview questionnaires were iteratively revised following each day of interviews. The initial questions applied cognitive testing of terms used to understand the domains of maternal capacities of initial interest: women's social support; psychological capabilities; roles, priorities and time; decision‐making/agency; and empowerment. Following early findings, we began to use phrases to help describe concepts in future interviews and focus groups, such as “to take another wife” to describe polygyny and “to feel free” to introduce the topic of empowerment. These domains were identified with a working group that developed a framework to be tested and refined in multiple contexts (Matare et al., 2015). In later stage interviews, the interview guide examined men's and women's child caring practices and roles related to nutrition and hygiene. These individual interviews revealed cultural patterns and processes that were assessed through vignettes in focus groups. Table 1 presents a sample of representative in‐depth interview questions, and Table 2 presents the focus group scenarios.

Table 1.

Sample questions and responses from semi‐structured interview guides, based on the theoretical framework constructs

| Maternal capability construct | Code/theme | Interview or focus group question | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roles, priorities, and time | Women's roles | Tell me any ways that your daily responsibilities affect how you feed your children. | “[Following a divorce] the care really goes down. And because when the woman divorces she takes only the child who is breastfeeding and still very young and the other ones left home, their feeding, their hygiene goes gown because the husband may not care as much as the mother could.” (Women's Focus Group #4) |

| Breastfeeding practices | Are there any ways that your daily responsibilities affect how long you decide to breastfeed your child? | “If the mother‐in‐law wants to give a big thing like juice or porridge to the baby before the right age of feeding her other foods besides breast milk, I will refuse and challenge her not to give. I will tell her, ‘Do not give that to my baby.’ Except if she does it away from my presence [while] walking around with the baby, or I have gone somewhere and he begins crying, then she can make a decision to feed him something different.” (Mother's Interview #17) | |

| Hygiene behaviors and practices | How are things like washing children done in your household? | “…washing the baby, washing their clothes, making sure that the baby's bed is clean. When a child comes from the toilet you as a mother are supposed to tell that kid to wash her hands…sometimes it is hard for me to get soap, so what I do is to wash the baby with only water.” (Mother's Interview #13) | |

| Men's roles | Tell me about any of the ways that your husband's help to care for the children in terms of nutrition. | “You may get 10,000 [cut off] when you are in the field, then you decide to buy, say, fresh fish for the family, but most of the times it is the woman with the money to buy food at home. For us men, we keep moving up and down, the kids may want food when you are not around.” (Men's Interview #13) | |

| Intrapersonal influences on capabilities | Desired change from husbands | Is there anything else that you would wish your husband could help with in regards to caring for the children? | “Yes, because sometimes I get upset with the children's behaviors so I sort of think that if the children's dad was around and he talks to them he can easily be feared.” Mother's Interview #4 |

| Family planning | How is the decision made in your family about when you will have another child? | “I wanted to have 4 kids but because sometimes I would not properly use the injection plans, I would find myself pregnant again.”

Moderator: Was he supporting you in using family planning? Mother: “It was my own decision; he was not supporting.” (Mother's Interviews #23) |

|

| Polygyny, consequences of | Do you have any power to stop your husband from taking another wife? Why or why not? | “In the case of [wife who becomes a co‐wife after a husband takes second wife], the baby will stay looking bad, and malnourished though she admires to buy things ‐‐like soap, sugar, passion fruits and other things to feed the kid— she cannot buy because she does not have the money, but what she does though she knows the good things to feed her baby, she will not do it because she does not have the money to buy them.” (Mother's Focus Group #2)

“Having many wives on many shambas (gardens) of cocoa does not mean you will now become rich. Because the more wives you have the more children you will produce and the more money you will need to spend to take them to school and pay for their school fees. So many people are now realizing that they are now changing from having many wives or multiple wives to keeping up with only one.” (Father's Focus Group #3) |

|

| Social support | Help around the pregnancy period | What kind of help do people provide to you after you give birth to a baby? | “My husband provides beans and nuts, drinks like passion juice, some porridge, and some smoked fish. My husband provides those things for me because he knows I am pregnant and I need to eat those foods.” (Mother's Interview #16) |

| Care while away | What type of help do you receive in caring for your children if you are away from home? | “He [my husband] also helps to feed the baby when I am going [to do] some other activities.” (Mother's Interview #10) | |

| In‐law interactions | Tell me the reasons why the young mom has less power to disagree with the mother in‐law than the older mom. | “The young mom is always vulnerable to fear to disobey the suggestion the mother in law brings for the dependency she has upon the mother in‐law that is she does not adhere to what the mother in‐law says, she will be refused of other help that she may get from the mother‐in‐law.” (Mother's Focus Group #3) | |

| Changes from men | Are there any other ways that you think you could help your wife with child feeding or hygiene? | “By constructing good and clean toilets, improving on the sleeping accommodation for the children and even the diet should improve, and modern ways of doing things.” (Father's Interview #3) | |

| Paternal support, changes | What do you feel is your husband's most important role in taking care of your children? | “The most common thing here has always been for the man to be the one to decide what will be eaten and purchased. To me, these days with the modern world, the woman says this is what we shall buy if you don't want it you leave and sleep hungry for us we shall buy what we want to eat. So you as a man what you do you also submit and follow the decision made by her.” (Father's Focus Group #3) | |

| Autonomy and decision‐making | Maternal agency | “Did you have any power to stop him from taking another wife?” | “I did not know. People told me that he had taken another wife.” (Father's Interview #23) |

| Physical autonomy | How free does a woman feel to leave your home to visit a family member or friend? | “The husband will first ask for a reason for the sudden travel. If it is an emergency there is no problem. She has the freedom to travel but it is not common in most households

[because]: some women don't go where they say they are going!” (Father's Interview #8) |

|

| Financial autonomy | If he husband says ‘no we cannot buy those foods because of money’, can the wife say let me go look for that money and try to buy the food that I know they are the right ones for the baby to eat? | “I will humbly tell and ask him that ‘please husband because of what I told you about buying the right foods for our baby and you said you do not have money to buy the foods.’ But me I realize I cannot start my baby with hard foods then what I did was to go to our women group, got the money to go and buy the right food I wanted for my baby. Even when I have to go work in someone's garden for the money, I will still tell my husband so that he also knows how I have got the money and where I have got it from” (Mother's Interview #7) | |

| Empowerment | What does the word empowerment mean to you? How does the idea of empowerment relate to feeding children? | “Yes, I have ever heard about it, but in a way that women also can make decision on our own like women being the ones to decide for themselves whether to get married to someone or not which was not the case for women here for example the woman would be forced to get married to a man she doesn't want so long as they want the dowry but the women now are free to decide for themselves what they want or don't want.” (Women's Interview #16) | |

| Psychological health | Psychological health | How does a mother who gets left behind [in the situation of polygyny] feel? | “[Her] heart will always be sad because her husband is always bringing sugar half kilo, or a kilo, bread and she knows she is not getting, any of those things so she feels sad, bad and bitter inside her heart.” (Mother's Focus Group #2) |

| Treatment of women in the community | What would be some changes, if a woman would be treated better what would be some recommendations? | “I am insisting on a woman having business, she would have some authority and be respected and not be treated badly.” (Mother's Interview #6) |

Table 2.

Focus group discussion guide vignettes

| Scenario 1 | “This is a story about two couples. Both live in this community and are of average income and social standing. Assume they are the same in every way except for the following differences. In the first family, both the man and woman complete Senior 4, and get married at age 21. A year later, the woman becomes pregnant.”

“In the second couple, a girl loses her father when she is 14. Since her mom cannot pay her school fees, an older man of 28 years in community offers to pay. This girl soon becomes pregnant with his child and she becomes married to the older man, and stops schooling. The women in both couples are both pregnant for the first time.” |

|---|---|

| Scenario 1 questions | Tell me about how these two women are treated in this community? By their husbands?

What impact does this have on the decisions that they can make about caring for their children? |

| Scenario 2 | “Each couple has 10,000 Shillings to spend for the week on food. The husband would like to use this money to buy meat and rice, but the wife wishes to buy a variety of foods that are appropriate for her child.” |

| Scenario 2 questions | How would this disagreement resolve in each couple? Who has the final word? |

2.5. Development of the focus group narrative

Three distinct processes and events were identified that routinely constrained caring capabilities and compromised child nutrition: (a) Becoming pregnant and getting married as an adolescent; (b) Becoming pregnant while still caring for a very young child; and (c) Becoming a co‐wife in a polygamous marriage. The focus group narrative (Table 2) was orally presented in focus groups to gain collective responses from parents regarding the likely community response to two hypothetical scenarios that incorporated these concepts. Focus group findings were coded into two main themes that all examined the differences between young mothers who married older men and mothers who are married to men their same age: (a) decision‐making around money and (b) treatment by others and support from the community. Because of the interconnectedness of themes, focus group and interview findings were incorporated.

2.6. Data analysis

All interviews and focus groups were audio‐recorded, and then back‐translated to English and transcribed verbatim by translators who were trained regarding the study purpose and theoretical background. Revisions were then made to the English transcripts as needed to ensure clarity and accuracy. Transcripts were read and coded by two separate analysts using Dedoose (Dedoose Software, Los Angeles, CA, USA) qualitative research software. Interview codes were developed deductively from the interview guides and inductively from emergent themes from the interview data. After agreeing on preliminary codes, a minimum inter‐rater reliability of >0.9 was established by testing for mutual agreement of code assignment with a sample of 10 transcripts. Direct text quotes were extracted from transcripts with participant identification numbers in order to link quotes with demographic data. Data reduction was accomplished by organizing representative quotes within each theme into schematic matrices to provide a hierarchical visual display of themes. Related themes were grouped together under dimensions of the social ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Demographic data was tabulated into an electronic database and response frequencies were calculated in STATA version 12.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

2.7. Ethical approval

The study was approved by The College of William and Mary Protection of Human Subjects Committee (PHSC‐2013‐03‐13‐8583‐sbickes) and by the Ministry of Health at the Mbale Regional Hospital Institutional Review Committee (UG‐IRC‐012).

3. RESULTS

We interviewed a total of 91 participants, 53 women and 38 men (Table 3). A total of 25 women and 15 men participated in structured interviews. A total of 51 community members (n = 28 women, n = 23 men) participated in focus group discussions. All data collection was completed between June and July 2013.

Table 3.

Demographics of study sample (n = 91)

| Mean or percent | |

|---|---|

| Female (n = 53) | 57% |

| Mean age in years (combined sample) | 30.0 |

| Men | 40.1 |

| Women | 26.0 |

| Mother's years of education (mean) | 4.9 |

| Father's years of education (mean) | 7.8 |

| Age at first birth of child (mothers) | 16.5 |

| Age at first birth of child (fathers) | 23.3 |

| Mean age of youngest child (months) | 18.6 |

| Marital status | |

| Married or living with partner | 80.0 |

| Separated or divorced | 7.0 |

| Widowed | 2.0 |

| Mean number of children | 4.6 |

| Mean number of wives for husband | 1.3 |

| Flooring material is dirt versus concrete | 97% |

| Improved roofing material with iron sheets | 96% |

| Received prior nutrition education | 75% |

| Primary water is from improved source | 57% |

| Mobile phone ownership | 45% |

| Mean distance to closest water sources (meters) | 601 |

The average years of education for mothers were 4.9 for mothers and 7.8 years for fathers. The mean maternal age was 26 years, and the mean paternal age was 40 years. Mothers were, on average, 16.5 years old when delivering their first child, compared with men who were 23.3 years when first becoming fathers. The mean of the youngest child cared for by the respondents was 18.6 months. The mean number of children per woman was 4.6. A total of 45% of the sample owned mobile phones, and 75% of the female sample has prior nutrition education.

Interview responses were hierarchically coded into 16 codes under five major themes: (a) Gender roles around child hygiene and feeding; (b) Cultural understanding of marriage; (c) Social support; (d) Autonomy and decision‐making processes; (e) Definitions of and expected outcomes of empowerment. We report findings under these five themes. Table 1 provides illustrative quotes for nodes within these themes.

3.1. Theme one: gender roles around child hygiene and feeding

Women were overwhelmingly identified, by both mothers and fathers, as the primary nutrition and hygiene care providers. The dominant role of women as caretakers was described in terms of cultural norms, and as a result of men being away from home for long periods of time to work:

“She is primarily responsible because for us men, we don't stay too much inside the homes. We go every day early in the morning and come back very late in the evening. So the rest of the care remains on the woman, and in fact they do a lot (Father's Interview 3, age 46, 8 children).”

The task of feeding children was understood to be “women's work,” although men are willing to help if their wives were busy. Women described the negative consequences of numerous conflicting responsibilities and the effect on their child care practices, citing the competing demand of agriculture and collecting water (Mother's Interviews 3, age 30, 5 children; Mother's Interview 5, age 18, 2 children).

In households where men felt better educated or informed than their spouses, they reported a larger role in child nutrition decisions:

“I am the one who decides [which foods to purchase] because my wife, [I] am sorry to say this, is not educated enough and she does not know the kinds of food that young children are supposed to eat except she is now learning by experience when am telling her the things children are to be fed on” (Father's Interview 4, age 28, 1 wife, 2 children).

Men were reported to have substantial indirect involvement through interaction with their wives, primarily as the main sources of income. According to one woman, the husband's most important role in taking care of children was “provision (in) money and his presence” (Mother's Interview 24, age 38, 6 children). Overall, men were not typically directly involved in the child feeding process, unless they had received some formal education on feeding small children. They often ceded these responsibilities to women as “she is the one who knows how the kids eat and what they like” (Father's Interview 11, age 59, 15 children). When men did know more about proper child feeding practices, they felt more responsibility toward ensuring that their children were fed well, and expressed this through increased support of their wives during the process. One father, for example, spent discretionary money on protein‐rich foods “because we know the size of the child depends on the way you feed him or her… if you feed the baby well, he or she will grow healthy and big; however, if she is poorly fed, the baby will grow unhealthy or be thin” (Father's Interview 4, age 28, 1 wife, 2 children).

When prompted to describe any desired changes in the care provided by their husbands, women reported a range of ideas, including taking over responsibilities that detract from feeding time, involving the wife more in decision making about food purchases, and assisting in child discipline. When asked whether she would like her husband to be more involved in household tasks, one woman responded, “yes, but nowadays I don't think that there is any man or husband who can bathe or cook for his children.” (Mother's Interview 5, age 18, 2 children). However, the majority of the women thought their husbands were capable of the changes they desired. Mothers saw increased paternal involvement in child nutrition as an important investment in the child's future and as a potential trend in the community. Men backed this up noting changing traditional nutrition and food procurement roles in “modern times.”

3.2. Theme two: cultural understandings of marriage

In response to questions about the presence of men in the household to provide care for children and a source of income for food procurement, the topic of marriage patterns and polygyny surfaced as a major theme. Polygyny was described in detail by participants as an historical cultural practice with general acceptance in the community. As one father noted, “it is culturally known that a man must marry as many wives as he wants” (Father's Interview 9, age 22, 1 wife, 2 children). Historically, polygyny served as a form of social protection, whereby a brother may marry his late brother's wife to provide for her and her children (i.e., levirate marriages). Contemporary reasons for polygynous marriage include family pressure (e.g., demonstration of success and prowess), a desire for a younger wife, increased support for household responsibilities, and a desire for more children. Polygyny was a more socially acceptable form of dealing with marriage difficulties than divorce whereby if a “man finds wife undesirable, he was more likely to find another wife than divorce her” (Father's Interview 16, age 60, 2 wives, 10 children). One man residing in a rural village described that he has “freedom and authority” to take another wife, even if his wife had equivalent education (Father's Interview 15, Age 60, two wives, 10 children).

Men described “a schedule” that required that they stay with all of their wives, even if they favor one wife more than another. When asked if taking another wife was like divorcing the first wife, one man said: CG: “No you stay with all of them as your wives and keep seeing all of them. For example, most polygamous men always allocate a specific number of days to spend with each woman. For instance, three days [with] each woman. And even if you do not see other women, they are aware of your schedule for them” (Father's Interview 4, age 28, 1 wife, two children).

Husbands acknowledged that some local churches discouraged polygamous marriage by openly advocating against men taking multiple wives. Within the context of a predominantly Christian district, religious norms in the district shape local beliefs about polygamous marriage; however, the influence of Christian marriage customs on marriage patterns and father's resulting child care involvement seems to have less to do with religious influence and more generally to do with changes in family size preferences and norms for male involvement among an increasingly educated population.

Mothers in polygynous marriages reported that a man's financial support decreased in the context of polygny (Mother's Interviews 18, 23, 25). Polygamous marriages negatively affected child feeding because husbands were less likely to help previous wives with tasks that detracted from time spent with the child. The male focus group of five men of mixed ages, including three in polygamous marriages, explained that a woman who has been “left” for a co‐wife is less likely to be able to “maintain order” in her compound. Participants noted that her appearance, and the growth and appearance of her children will suffer due to increased financial constraint and from becoming overworked. Cash allowances and tangible goods were likely to decrease when a new wife was attained. Even if a man did continue to financially provide for his wife, loss of time and access was a negative consequence with increasing number of wives. One male focus group confirmed this, saying care given to families by men was “less on many wives, rather than number of children” (Father's Focus Group 3).

Women's Focus Groups: “[When a man takes a second wife] child care goes down for both families because now the husband may not care much about the children and like even the medical care goes down like when the child is sick he will tell you the mother to struggle on your own for your child. Even stop giving the school fees for the child. The young one will suffer more because she is more dependent on the husband only but the older mother could have accumulated her own income and her gardens” (Mother's Focus Group 4).

In the context of the focus groups, care was most commonly understood as providing regular financial assistance to provide adequate food, housing, and clothing for a man's wives and children.

3.3. Theme three: social support sources, and variations

3.3.1. In‐law interactions

Mothers described a range of relationships and instances where they received support from others. This support was emotional (e.g. receiving empathy from others about the hard work of mothering), informational (e.g. offering advice in the case of a sick child), and instrumental (e.g. help with household chores). Mothers‐in‐law were described to be a major provider of support to mothers. Generally, “most of the responsibility when I have given birth is on my mother‐in‐law” (Mother's Interview 18, age 25, expecting first child).

As a patrilocal society, the mother‐in‐law's social support is generally accepted and expected. Mothers commonly leave their infants and small children with their mothers‐in‐law. The timing of support ranges in frequency, from critical periods such as post‐childbirth, to daily care of young children, depending on other available forms of support and women's other responsibilities. For instance, “on the day of delivering the baby when both my mom and mother‐in‐law are together at the same place and I need help, I will easily rush to my real mother for better comfort but for the other help besides that I can go to the mother‐in‐law” (Mother's Interview 16, age 18, expecting first child). Fathers‐in‐law were described to provide more basic tangible goods such as food, soap, and medication.

Whether a mother resides with the husband's family influences types of support, interactions between support providers, and restrictions on social support received. If a mother lives with her husband's family, the mother‐in‐law takes on a prominent role in support through passing on personal education and experience.

As one mother noted, “The husband's side is the one that usually provides the most care…the reason is that come to be living with the family of the husband and the one who impregnated you, and the child you have is more of the family of the father than mother” (Mother's Interview 24, age 38, 6 children).

Social support was referenced directly in response to the focus group narrative. Participants noted that the younger, more vulnerable mother would provide less healthy nutrition and general care for her children because of lack of support, experiences, and resources.

“There is a big difference in taking care of the children between the one of a young age and the one of mature age. For example, the woman who got a baby at a young age may delay feeding the baby or not doing it the right way because she has no experience she was not ready for taking care of other children. Until somebody else comes in and educated her on how to do it because she is still using childish behaviors. So a young mother needs more support” (Men's Focus Group #4).

However, younger mothers were perceived to be less open to receiving informational support from older mothers. A group of older mothers noted: “Yes, we all agree together that young moms despise our teaching about how to feed children. For example, if you are advising someone please feed your child well” and she says, “Why do you always come to direct me about feeding my kid? Will I come back again? I will not.” (Mother's Focus Group #2).

3.3.2. Help around the pregnancy and lactation period

The Primary Care Giver is highly dependent on emotional, financial, tangible goods, and actionable support during the time initially after childbirth. Husbands, in‐laws, family, and friends were all cited as providing varying amounts of additional social support during this time, with husbands and mothers‐in‐law most often cited as providing additional care.

Female Care Giver: “She [the mother‐in‐law] will come and stay for some days, and when I become a bit ok and able to do some simple work myself, then she will go back to her place, at least one to two months… the first days of the first week after I deliver she will stay and the next weeks or months she will be helping me from her home and if she is tired my family of my side will also take over” (Mother's Interview 16, age 18, expecting first child).

Men typically recognize the time during and around pregnancy as one marked by special needs of the woman. “Women are always weak when they just give birth,” noted one father, and thus require additional food and supplies (Father's Interview 4, age 28, one wife, 2 children). One woman said her husband “gave (her) food and some drinks… beans and nuts, drinks like passion juice, some porridge and some smoked fish… because he knows (she is) pregnant and she needs to eat those foods” (Mother's Interview 16, age 18, expecting first child).

Mothers discussed breastfeeding as central to the topic of nutritional care, and related to maternal capabilities: In a follow up question about whether younger mothers had better social support and could, by extension, provide better care, a focus group of mothers responded: “It depends. You can be a young mother, have a child, and be able to breastfeed well but you could have an older mother who could be unable to breastfeed. It [the quality of the care a mother can provide] may all depend on the ability of this mother to breastfeed for this child to grow well.” (Mother's Focus Group #4).

Mothers felt that most mother‐in‐laws understood that feeding juice and other foods during the early months when breastfeeding was “not good for the child” but that situations did arise where in‐laws and mothers disagreed about whether it was appropriate to feed other foods to nursing babies. A discussion followed about whether women could “challenge” their mother‐in‐law's if they had opposing views about breastfeeding, or tried to interfere by giving juice or glucose before the appropriate age. Mother's noted that they could challenge their in‐law's position, but that they may not be able to control whether a breastfed child is fed other foods when they are away. “Yes. If I am around seeing what is going to happen, if the mother‐in‐law wants to give a big thing like juice or porridge to the baby before the right age of feeding her other foods besides breast milk, I will refuse and challenge her not to give. I will tell her, ‘Do not give that to my baby.’ Except if she does it away from my presence… walking around with the baby… or I have gone somewhere and he begins crying, then she can make a decision to feed him something different. But when I am there I will stop her, I can't accept.” Another mother chimed in “I am free to say no to my mother in law for the sake of the life of my baby, whether she feels bad about it, I can still stop her to do it.” (Mother's Focus Group #2).

Women noted that the ability of mother's to object to their mother‐in‐law's decisions was dependent on a mother's situational capabilities (influenced, for example, by the age and manner in which she marries): “Mostly the young mother is vulnerable of following the decision of the mother‐in‐law of feeding tea or juice to her baby before she is ready for it. Because of being young she feels that she has to follow the decisions of the mother in‐law. Then the older mother who will be able to refuse to follow everything the mother‐in‐law says because of her age and the education she may be knowing the information about when it is ready to feed the child and she will do it without fear.” (Women's Focus Group #3).

3.3.3. Care for children while mothers are away

While away, mothers reported several sources of child care, including husbands, co‐wives, and in‐laws (Mother's Interviews 7, 10, 18). Mothers desired proper care for their child, demonstrated by precautions taken before leaving. For example, one mother knew she could trust a co‐wife to care for her children because “I told her how to cook for the little sick one and she does exactly as I told her” (Mother's Interview 9, age 28, 4 children). These precautions were more likely to be taken with husbands and co‐wives than with mothers‐in‐law. Women demonstrated trust and appreciation for the care provided for their children by their mothers: “She [my mother] does a great job‐the way I would do it if I was the one” (Mother's Interview 11, age 38, 7 children).

3.3.4. Treatment by others and support from the community

Respondents describe the older mother in the focus group vignette as possessing greater decision‐making abilities compared with the younger mother who was forced to marry after becoming pregnant. Both men and women describe that the younger mother has a greater loss of social support from her birth mother following the sudden marriage. Participants also note that social support for a woman from her birth mother declines after marriage when women become de facto members of the husband's family.

While it was recognized that younger mothers face greater challenges, women had equally strong statements about polygyny's negative consequences:

“Generally the young mom suffers much because for her she had depended totally on the husband to provide for everything. So when the man changes, then it becomes a problem to her when he gets another woman. But in both circumstances—whether you are young or old—when your husband brings in a new wife, then you know suffering has come to both of you, for you both face abandonment and the sharing of your resources with another woman” (Mother's Focus Group 3).

3.4. Theme four: autonomy and decision‐making processes

3.4.1. Financial autonomy

Men were described (by themselves and by women) as the primary earners in the community. Participants described that men make the majority of financial decisions, although they may delegate certain financial responsibilities to their wives. When asked about community practices, most men said men in the community tend to spend money on themselves first.

Male Care Giver: “Here in Bundibugyo, according to our culture, what the man decides is always final. We take ourselves to be superior over women, but me personally I do not use that kind of force to take the money for whatever I want to buy as other men do” (Father's Interview 11, age 59, 1 wife, 15 children).

Following the husband's initial draw of earned income, the remaining money may then be allocated to the mother to purchase the food that she needs to feed the children. Wives with financial freedom were likely to buy the foods they believe their child needed. Women saw financial autonomy as a requisite to properly care for their children; when one woman was asked if there was anything that she wished her husband could be involved in, she replied, “I would wish he gave me some money to keep in my pocket so that at any time I want to buy something I can go and buy it” (Mother's Interview 8, age 17, 1 child). Older women tended to have more financial autonomy than younger women, partially due to increased income generating capacity (Mother's Focus Group 4). Too much financial independence was viewed as a threat by men: when women do not make too much money, “men look at it as a good thing. The problem comes when a woman owns a big shop and has a lot of money… she becomes proud and disrespecting” (Father's Interview 16, age 60, 10 children). It is possible that a man may override delegated financial responsibility if he questions a financial decision.

Despite a general recognition that men control financial resources and an agreement that the hypothetical scenarios of financial disagreement are common in the community, male focus group respondents report that financial freedom for women is strong when it comes to food purchases.

“That [the disagreement described in the narrative] is how it is [in Bundibugyo]. If you don't just submit to what the woman says about what to buy for the family food. You will end up in a fight. So the only resolution is to just submit to her decision for what she wants to buy” (Men's Focus Group 3).

However, mothers noted that the social position of wives to their husbands (based on age and the manner by which they became married) influences their decision‐making power. Compared with a younger mother, “in general, with an older mother, her decisions or opinions can be heard because of her income generating capacity… generally the older mother has an upper hand in making decisions” (Mother's Focus Group 4). Participants also noted maternal agency was influenced by whether a woman believes her husband respects her decisions.

Mother's Focus Group: “Generally this girl [in the narrative] who is married at a young age, her ideas are not respected because they look at her as inexperienced but an older mother's decisions and opinions are more respected that as a grown up person she has experience, she knows about marriage and she can make her own decisions” (Mother's Focus Group 4).

Despite differences between women, men described themselves as willing to concede to women given their expertise in cooking and knowing family preferences:

“To me, these days with the modern world the woman says ‘This is what we shall buy. If you don't want it, you leave and sleep hungry. For us we shall buy what we want to eat.’ So you as a man, what you do you also submit and follow the decision made by her. What I also know when you stay with a woman for a long period of years the woman becomes experienced of what to buy for the care of the food that the family likes.” (Men's Focus Group 3).

With regard to leveraging available resources and knowledge to help in the case of child illness, participants felt that the older mother was more suited due to experience, decision‐making confidence, and financial resources.

“So basically the advantage that this older mother not being dependent on the mother‐in‐law is important because whenever she gets any problem she is able to respond quickly on her own, without first consultations from where … to get some help. She just wakes up when there is an emergency and solves it by herself, without waiting or delay because she is capable than the one that depends on another person to come and help financially” (Women's Focus Group 3).

Men felt that it was important for both caregivers to attend educational programs about nutrition together in order to reach shared decisions about spending money:

“For me I think there are women who are hard to handle, according to how she doesn't know what you the husband learned, from the program, it will require you another day to go with that woman to that program so that she can hear by herself” (Men's Focus Group 3).

3.4.2. Reproductive decision‐making

Family planning was a common discussion between wives and husbands. Mothers largely described men as having the ultimate authority in determining family size. When asked about child spacing, one mother said, “(the husband) is the one who makes the decision when he wants me to become pregnant again.” (Mother's Interview 16, age 18, expecting first child). When asked about the normal family planning process, one man said, “[It is] mostly me, the man depending, on my income and ability to take care of those I already have” (Father's Interview 16, age 60, 2 wives, 10 children). PCG's who had similar levels of education compared with their husbands experienced greater decision‐making capability in family planning, as both had similar understandings of birth control, child spacing, and family size.

MCG: “First of all, for them [a husband and wife with similar education] easily know how to plan for the family like spacing since they have the same level of education. Those who have differences in the education level, it is hard for them to make one decision about family planning.” (Father's Interview 9, age 22, 1 wife, 2 children).

Although a historically higher number of children was associated with prosperity, the importance of having many children as a way to continue the family line is in decline. Men cited ability to financially support the family as a factor in family planning. “It is no use producing many children when you are not taking care of them well,” said one father (Father's Interview 4, age 28, 2 children). Majorities of both genders reported use and support of contraceptives, though freedom to use contraceptives by mothers varied.

3.5. Theme five: definitions of and expected outcomes of empowerment

Women's described meanings of empowerment were diverse. Some had not heard the term, or could not define it, while others had complex definitions and described their own experiences with becoming empowered. Most commonly women associated empowerment with education, financial independence, and “giving women freedom to make their own choices” (Mother's Interview 2, age 17, one child). Several women defined the word as independence: “doing something that your heart desires to do” or “having the freedom from my husband to do what I want” (Mother's Interviews 9 and 14). The word “empowerment” was sometimes framed in the context of gender, defined as “being supportive to each other as women, and also men and women being supportive of each other (Mother's Interview 9, age 28, 4 children).”

One mother described the term: “I only know it as a way of stopping men from stepping on women.” (Mother's Interview 10, age 19, two children).

Women consistently defined empowerment in terms of economic access. A woman is considered empowered if she is able to own her own business, earn income “as a woman” and financially support the family. Women would feel more empowered if there were a credit system to support businesses (Mother's Interview 2, age 17, one child).

Women also defined empowerment as the ability to decide who they want to marry and when.

FCG: “Yes I have ever heard about it, but in a way that women also can make decisions on our own. Like women being the ones to decide for themselves whether to get married to someone or not which was not the case for women here. For example, the woman would be forced to get married to a man she doesn't want, so long as they want the dowry. But the women now are free to decide for themselves what they want or don't want” (Mother's Interview 16, age 18, expecting first child). Some women suggested that they would feel more empowered if their husbands “did not take multiple wives” (Mother's Interview 1, age 20, two children).

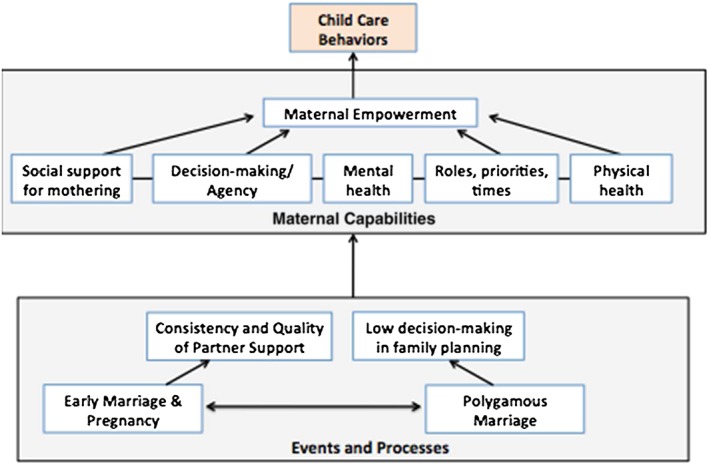

3.6. Development of conceptual framework

The initial framework used to guide this study was developed by a working group led by Professor Rebecca Stoltzfus at Cornell University. This working group developed the maternal capabilities framework, which proposes that mother's abilities to leverage care to children are influenced by intrinsic capabilities, which include social support, psychological health, maternal roles and time, and women's decision‐making/agency. The framework is still under development, and a number of studies are currently underway to continue the development process in multiple contexts. The members of the working group are listed in the acknowledgements section. Figure 1 builds on this framework to illustrate how cultural events and processes shape maternal capabilities. Key themes were compared with the initial theoretical framework to visually depict the events and processes that shaped maternal capabilities. Early marriage and pregnancy both influenced the consistency and quality of support received by women from their partners. Polygamous marriage often resulted in limited decision‐making in family planning, and the consistency of material and interpersonal support available for women. Collectively, these common events constrained maternal capabilities for child caring, and negatively influenced child caring behavioral patterns and roles in Ugandan households.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of life events and cultural processes that shape maternal capabilities and influence child nutrition and hygiene care behaviors

4. DISCUSSION

This study examined the relevant maternal capabilities for nutrition and hygiene care in a world region where nearly 50% of children are malnourished, and with one of the highest fertility rates globally. We accessed community knowledge from male and female participants of a wide age range, and garnered insights from the community members about sensitive topics from cultural marriage patterns, intrahousehold decision‐making, and perceptions and treatment of women based on different trajectories of becoming mothers. Against a backdrop of a growing public health narrative of “male involvement” and “women's empowerment,” the processes that create patriarchal contexts and the consequences of such contexts are important to understand when developing effective approaches to improve child health (Bhatta, 2013; Mamane et al., 2015).

4.1. Key findings

Both mothers and fathers, young and old, express consistent desires to provide quality nutrition and hygiene care to children. Within genders, the acceptability of the cultural practice of polygyny varied, although most participants pointed to this tradition as a cultural institution that often placed women and children at risk for poor health outcomes due to inconsistent male support. While mothers are the primary caretakers for both hygiene and nutrition, men in this community function to purchase food and participate in some of the child caring routine. Moreover, men express an interest in becoming more involved in nutritional care for children, and in providing better general support for child care.

Current work in the area of maternal capabilities is ongoing, and the applicability of this domain will soon become more clear across a variety of contexts. A Caregiver Capabilities Working Group defines maternal capabilities as having “good physical health, low levels of depressive symptoms, less stress and more social support, high levels of mothering self‐efficacy, and being more autonomous” (Matare et al., 2015). The constructs of social support, decision‐making, and confidence (self‐efficacy) are the most recognizable in this context, while the more abstract concept of mental health was less discussed. Ugandan mothers in this semi‐rural and remote context readily drew connections between general “capabilities” and more immediate child caring practices (that resulted from capabilities) and relevant events and processes (that shaped these capabilities). For example, early marriage was readily connected to a loss of social support, and less specific knowledge and decision‐making freedom to feed children. The experience of discussing these concepts was described by mothers as “empowering” and important for the community, and men shared the opinion that open conversations about how household decisions are made, and how partners can better work together to care for children in the community were helpful. The use a de‐personalized vignette in the focus group discussions was an effective method of stimulating discussion about a potentially taboo subject. Moreover, this allowed participants to collectively improve upon the narrative, to make the experience more realistic to the normative cultural practice.

4.2. Comparison with other studies

A growing literature provides rich qualitative evidence to inform the development of behavior change communication strategies to promote child health in East and Southern Africa (Flax, 2015; Degefie, Amare, & Mulligan, 2014). These studies emphasize a need to define and understand the dimensions of women's empowerment and the sources of constraint (Permunta & Fubah, 2015), as well as cultural beliefs about the care‐related causes of malnutrition in local communities (Flax, 2015).

The importance of maternal agency in the decision to become pregnant remains a critical child health and nutrition challenge, within and outside of the sub‐Saharan African context (Rousham & Khandakar, 2016). Early marriage and the corresponding process of becoming a daughter‐in‐law and taking up residence at the compound of a husband's family has been shown to limit women's autonomy and increase her dependence on other household members (Cunningham, Ruel, Ferguson, & Uauy, 2015; Rousham & Khandakar, 2016).

Community mobilization approaches are a promising method for transforming gender norms to reduce disease incidence and have been developed and tested to address HIV in sub‐Saharan Africa (Barker, Ricardo, Nascimento, Olukoya, & Santos, 2010; Pettifor et al., 2015). These efforts extend traditional group education models to more participatory, discussion‐based approaches and require deep cultural knowledge to be contextually‐relevant. With a growing evidence base that links gender inequity to poor child nutrition, the nutrition community may be well‐guided by these approaches to address gender inequities.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

Through our use of trusted local translators, and because the research team had experience living and working in the Bundibugyo community, we were able to establish rapport with the participants. Our study sample was comprised of mothers and fathers from diverse age ranges and experience with caring for young children. Hence, we recruited a sample that was representative of the life experiences we sought to understand.

The nature of the study does not allow us to rule out the possibility that certain constructs have merit. While questions about mental health produced relatively limited discussion, we cannot conclude that this construct is irrelevant in the community, only that it was less directly linked as a constraint to child nutrition in caregiver minds. Linking qualitative findings with indicators of child feeding and nutritional status would provide additional evidence to clarify patterns of responses by behaviors and nutrition outcomes, but was beyond the scope of this study.

4.4. Implications and conclusions

The applicability and meaning of each of the domains explored in this study, and the measurement and eventual attempts to strengthen maternal capabilities for child nutrition, rests on bringing community‐informed meaning to the critical social constructs for providing nutrition care, and the events and processes that shape those constructs. In the Ugandan context, early marriage, being a co‐wife in a polygamous marriage, and caring for closely spaced children are commonly described events that constrain caregiver capabilities, especially social support for mothers, and further challenge adequate child feeding and hygienic care. Engaging the next generation of fathers to become more involved in nutrition care needs to be carefully implemented with clear knowledge of the complex and changing relationships between partners and cultural values in which these relationships exist.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

This study was funded by the Schroeder Center for Health Policy, and the Borgenicht Fund for Health Sciences research at the College of William and Mary.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

SI designed the study, sought ethical approval, developed the study questionnaires, analyzed findings and wrote the study paper. TW and BC developed the study questionnaires, conducted interviews, and analyzed study findings. GH analyzed the data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the study translators, Tusiime Annet, Kyalimpa Bonifice, and Bonifice Biihwa for translating and transcription of the interviews. We thank the study participants for sharing their time and experiences. We acknowledge the assistance of Ashley Booth, Maggie Gutierrez, Sarah Martin, Carolyn Hartley, Alexandra Court, and Scott Gemmel‐Davis for help with interview coding and analysis. This work was conceptualized with the Maternal Capabilities Working Group at Cornell University, led by Rebecca Stoltzfus. This working group includes Mark Constas, Kate Dickin, Jean‐Pierre Habicht, Cynthia Matare, Gretel Pelto, and Amanda Zongrone.

Ickes SB, Heymsfield GA, Wright TW, Baguma C. “Generally the young mom suffers much:” Socio‐cultural influences of maternal capabilities and nutrition care in Uganda. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13:e12365 10.1111/mcn.12365

REFERENCES

- Alkire, S. , & Ibrahim, S. (2007). Agency and empowerment: A proposal for internationally comparable indicators. Oxford Development Studies, 35, 379–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ashaba, S. , Rukundo, G. Z. , Beinempaka, F. , Ntaro, M. , & LeBlanc, J. C. (2015). Maternal depression and malnutrition in children in southwestern Uganda: A case control study. BMC Public Health, 15, 1303–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baez, B. (2002). Confidentiality in qualitative research: Reflections on secrets, power and agency. Qualitative Research., 2, 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, G. , Ricardo, C. , Nascimento, M. , Olukoya, A. , & Santos, C. (2010). Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: Evidence of impact. Global Public Health, 5, 539–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, R. E. , Victora, C. G. , Walker, S. P. , Bhutta, Z. A. , Christian, P. , de Onis, M. , et al. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low‐income and middle‐income countries. Lancet, 382, 427–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta, D. N. (2013). Involvement of males in antenatal care, birth preparedness, exclusive breast feeding and immunizations for children in Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13, 14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, C. J. , Kordas, K. , & Murray‐Kolb, L. (2015). Associations between women's autonomy and child nutritional status: A review of the literature. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 11, 452–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, B. , Stephenson, R. , & Leon, J. S. (2010). Maternal behavior and experience, care access, and agency as determinants of child diarrhea in Bolivia. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 28, 429–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, K. , Ruel, M. , Ferguson, E. , & Uauy, R. (2015). Women's empowerment and child nutritional status in South Asia: A synthesis of the literature. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 1, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degefie, T. , Amare, Y. , & Mulligan, B. (2014). Local understandings of care during delivery and postnatal period to inform home based package of newborn care interventions in rural Ethiopia: A qualitative study. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 14, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engebresten, I. M. S. , Wamani, H. , Karamagi, C. , Semiyaga, N. , Tumwine, J. , & Tylleskar, T. (2007). Low adherence to exclusive breastfeeding in Eastern Uganda: A community‐based cross‐sectional study comparing dietary recall since birth with 24‐hour recall. BMC Pediatrics, 7, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle, P. , Menon, P. , & Haddad, L. (1999). Care and nutrition: Concepts and measurement. World Development, 27, 1309–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Grootaert, C (2003).On the relationship between empowerment, social capital and community‐driven development. World Bank. Working Paper no. 33074. [Online] http://go.worldbank.org/EYUP8R7IC0 [accessed 10 Janaury 2016]

- Ickes, S. B. , Hurst, T. E. , & Flax, V. (2015). Maternal literacy, facility birth, and education are positively associated with better infant and young child feeding practices and nutritional status among Ugandan Children. Journal of Nutrition, 145, 2578–2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flax, V. (2015). It was caused by the carelessness of the parents’: Cultural models of child malnutrition in southern Malawi. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 11, 104–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodish, S. , Aburto, N. , Hambayi, M. N. , Kennedy, C. , & Gittelsohn, J. (2015). Identifying the sociocultural barriers and facilitating factors to nutrition‐related behavior change: Formative research for a stunting prevention program in Ntchisi, Malawi. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 36, 138–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, A. , Schuler, S. , & Boender, C. (2002). Measuring women's empowerment as a variable in international development In Narayan D. (Ed.), Measuring empowerment: cross‐ disciplinary perspectives (). (pp. 71–88). Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Mamane, S. , Kajula, L. , Balvanz, P. , Kilonzo, M. , Mulawa, M. , & Yamanis, T. (2015). Leveraging strong social ties among young men in Dar es Salaam: A pilot intervention of microfinance and peer leadership for HIV and gender‐based violence prevention. Global Public Health, 20, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matare C., Mbuya M.N., Pelto G., Dickin K.L., & Stoltzfus R.J: Sanitation, Hygiene, Infant Nutrition Efficacy (SHINE) Trial Team . (2015) Assessing maternal capabilities in the SHINE trial: Highlighting a hidden link in the causal pathway to child Health. Clinical Infectious Diseases 15 (S7),S745–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, K. H. , Muti, M. , Khalfan, S. S. , Humphrey, J. H. , Caffarella, R. , & Stoltzfus, R. J. (2011). Beyond food insecurity: how context can improve complementary feeding interventions. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 32(3), 244–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelto, G. H. (1991). The role of behavioral research in the prevention and management of invasive diarrheas. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 13(suppl 4), S255–S258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor, A. , Lippman, S. A. , Sellin, A. M. , Peacock, D. , Goddert, A. , Maman, S. , et al. (2015). A cluster‐randomized A cluster randomized‐controlled trial of a community mobilization intervention to change gender norms and reduce HIV risk in rural South Africa: Study design and intervention. BMC Public Health, 15, 752–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Permunta, N. V. , & Fubah, M. A. (2015). Socio‐cultural determinants of infant malnutrition in Cameroon. Journal of Biosocial Science, 47(4), 423–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousham, E. K. , & Khandakar, I. U. (2016). Reducing health inequalities among girls and adolescent women living in poverty: The success of Bangladesh. Annals of Human Biology, 14, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel, M. , & Alderman, H. (2013). Nutrition‐sensitive interventions and programmes: How can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet, 561, 536–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman, K. , Lansdown, R. , & Sullivan, K. (2006). Women's empowerment and domestic violence: The role of sociocultural determinants in maternal and child undernutrition in tribal and rural communities in South India. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 27, 128–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shroff, M. R. , Griffiths, P. L. , Suchindran, C. , Nagalla, B. , Vazir, S. , & Bentley, M. E. (2011). Does maternal autonomy influence feeding practices and infant growth in rural India? Social Science and Medicine, 73, 447–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugandan Travel Guide . “Batooro people and culture” Retrieved from http://www.ugandatravelguide.com/tooro-kingdom-culture.html on May 10, 2016.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF International Inc (2012). Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011 In Kampala, Uganda: UBOS and Calverton. Maryland: ICF International Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ulin, P. R. , Robinson, E. T. , Tolley, E. E. , & McNeil, E. T. (2002). Qualitative methods: A field guide for applied research in sexual and reproductive health Family Health International: Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Inter‐agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) (2015). Levels and trends in child mortality: Report 2015 New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of State . International Religious Freedom Report 2009. Retrieved at http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2009/127261.htm on Janaury 22, 2016.