Abstract

Antenatal calcium and iron‐folic acid (IFA) supplementation can reduce maternal mortality and morbidity. Yet, even when pregnant women have a stable supply of supplements, forgetting is often a barrier to adherence. We assessed the acceptability of adherence partners to support calcium and IFA supplementation among pregnant women in Kenya and Ethiopia. Adherence partners are a behaviour change strategy to improve adherence, where pregnant women are counselled to select a partner (e.g. spouse, relative) to remind them to take their supplements. We conducted trials of improved practices, a formative research method that follows participants over time as they try a new behaviour. We provided pregnant women in Ethiopia (n = 50) and Kenya (n = 35) with calcium and IFA supplements and counselling, and suggested selecting an adherence partner. For each participant, we conducted semi‐structured interviews about acceptability and adherence during four interviews over six weeks. We analysed interview transcripts thematically and tallied numerical data. In Kenya, 28 of 35 women agreed to try an adherence partner; almost all selected their husbands. In Ethiopia, 42 of 50 women agreed to try an adherence partner; half asked their husbands, others asked children or relatives. Most women who did not select adherence partners reported not needing help or not having anyone to ask. Participants reported adherence partners reminded and encouraged them, brought supplements, provided food and helped address side‐effects. Almost all women with adherence partners would recommend this strategy to others. Adherence partners are an acceptable, low‐cost strategy with the potential to support antenatal micronutrient supplementation adherence.

Introduction

Maternal and child mortality remain unacceptably high in many countries. Antenatal iron‐folic acid (IFA) and calcium supplementation are two interventions that could substantially reduce the risk of iron‐deficiency anaemia and preeclampsia, resulting in lower maternal and child morbidity and mortality (Imdad et al. 2011; Bhutta et al. 2013; Hofmeyr et al. 2010; Peña‐Rosas et al. 2012). However, there are many challenges to successfully implementing antenatal micronutrient supplementation programmes at the policy, health facility, community and individual levels (Yip 2002; Stoltzfus 2011; Galloway et al. 2002), which require health system strengthening and effective social and behaviour change interventions (Sanghvi et al. 2010). In countries with low habitual calcium intake, the recommended daily regimen is three to four calcium supplements and one IFA supplement throughout pregnancy (World Health Organization 2013), which could exacerbate existing supply, distribution and delivery challenges (Omotayo et al. 2016) and make adherence especially difficult (Hofmeyr et al. 2014). This complex regimen warrants the development and evaluation of interventions to support adherence (Hofmeyr et al. 2014; Baxter et al. 2014).

Lessons learned from IFA supplementation programmes can provide valuable insight into the design and delivery of calcium supplementation interventions (Martin et al. 2016). Supplement supply and distribution challenges substantially contribute to low levels of IFA uptake and adherence in many low‐resource settings (Sanghvi et al. 2010; Galloway et al. 2002). Yet, even when women have access to supplements, they often experience inadequate counselling (Galloway et al. 2002) and more proximal barriers to adherence such as family disapproval (Aguayo et al. 2005; Taye et al. 2015) and forgetting (Gebremedhin et al. 2014; Kulkarni et al. 2010; Zavaleta et al. 2014; Seck and Jackson 2008). Alternative strategies are needed to ensure that women and their families understand the importance of supplements and remembering to take them (Kulkarni et al. 2010).

In this paper we examine the role of adherence partners as a strategy to improve adherence to antenatal supplementation. The objective of our research was to assess the acceptability of adherence partners to support adherence to calcium and IFA supplements among pregnant women in Kenya and Ethiopia. Antenatal micronutrient supplementation occurs within the context of care‐seeking in pregnancy, which is often influenced by cultural and social constraints. An adherence partner is someone who is already part of a pregnant woman's social network who can address these constraints through support tailored to her context and individual needs. Social support influences micronutrient supplementation uptake and adherence (Taye et al. 2015; Seck and Jackson 2008; Aguayo et al. 2005; Kulkarni et al. 2010; Nagata et al. 2012). In formative research in Kenya and Ethiopia, some pregnant women reported being reminded and encouraged by husbands and family members to take IFA supplements, while others wished for additional support (Martin et al. 2016). Adherence partners are a low‐cost strategy that could leverage this support to increase adherence to antenatal micronutrient supplements. Partners, also called supporters or buddies, have been used to improve health behaviours such as medication adherence (Idoko et al. 2007; Remien et al. 2005; Taiwo et al. 2010; Unge et al. 2010) and infant feeding (Andreson et al. 2013); and peer “keepers” have been recommended for IFA (Willardson et al. 2013).

Key messages.

Forgetting is a common barrier to antenatal micronutrient supplementation adherence.

Adherence partners are members of a woman's social network who provide reminders and encouragement.

Pregnant women in Ethiopia and Kenya reported adherence partners were acceptable.

Adherence partners are a strategy to improve antenatal micronutrient supplement adherence.

Methods

The larger research project

This study is part of a larger research project in Kenya and Ethiopia, which investigated the acceptability and feasibility of integrating calcium supplements into antenatal IFA supplementation programmes (Omotayo et al. 2015). In both countries, we used trials of improved practices (TIPs) (Dickin et al. 1997) to compare the acceptability and feasibility of three different calcium and IFA supplement regimens, investigate the acceptability of two different types of calcium tablets (chewable vs. hard) and identify barriers and facilitators to calcium and IFA supplement uptake and adherence. Within the context of this TIPs research project on calcium and IFA supplementation in Kenya and Ethiopia, we explored the acceptability of adherence partners.

TIPs is a mixed‐methods formative research method to assess the acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of new, recommended health behaviours by conducting a series of visits during which participants are counselled on and can choose to try a behaviour (Dickin et al. 1997; The Manoff Group 2005). Multiple visits allow researchers to explore participants' previous related experience, and assess their willingness to try the new behaviour, whether they actually tried the behaviour, and if they continued to practice the behaviour (Dickin et al. 1997).

Study setting

The Kenyan site was in Malava sub‐county, Kakamega County, in rural western Kenya, where most residents are Luhya. In the 2014 Demographic and Health Survey, 96% of women in Kakamega County received ANC from a trained provider at least once during pregnancy and 47% delivered in a health facility. Although 61% of women in Western Kenya took any iron supplements during pregnancy, only 7% took them for the recommended 90 or more days (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF International 2015). IFA supply and distribution barriers are common in Kenya (Maina‐Gathigi et al. 2013). Formative research confirmed frequent IFA shortages and stockouts in Malava sub‐county. In addition, many women and health workers reported women generally receive little support from their husbands during pregnancy, but some women reported husbands or female relatives reminded and encouraged them to take IFA (Martin et al. 2016).

The Ethiopian site included 10 communities in Ada'a Berga and Meta Robi districts, West Shewa zone, Oromia region, where most residents are Oromo. We selected small towns and rural communities with varying levels of accessibility by road. In the 2011 Demographic and Health Survey, 31% of women in Oromia received ANC from a skilled provider and 8% gave birth at a health facility. Only 12% of pregnant women took any iron supplements during pregnancy (Central Statistical Agency and ICF International 2012). These communities were part of a recently completed antenatal IFA supplementation programme that trained health workers to counsel women and provide supplements, and promoted adherence through community mobilization (Micronutrient Initiative 2015). Our formative research revealed that IFA was available at most health facilities, and women in these districts had high levels of social support during pregnancy, with several reporting that husbands and family members reminded them to take their IFA supplements.

Measures and data collection

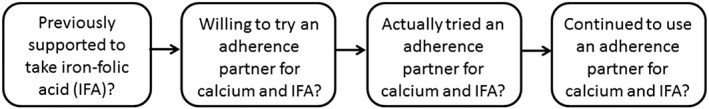

We conducted TIPs in Kenya from February to May 2014 and in Ethiopia from December 2014 to February 2015. In both countries, the TIPs research comprised four visits to pregnant women's homes; approximately one visit every two weeks for six weeks. After interviewers provided participants with calcium and IFA supplements, counselling and regimen calendars, they counselled participants on the potential benefits of asking someone they know (e.g. a spouse, other relative, friend) to support them to take calcium and IFA supplements throughout pregnancy. Although adherence partners is the term we use to describe this relationship, it was described to women as someone who can remind and encourage them to take their supplements. During the four interviews, participants were asked about previous social support received for IFA, if they were willing to try an adherence partner, if they actually tried an adherence partner, and if they continued to have an adherence partner (Fig. 1). Because participants made different choices about adherence partners at each visit and followed different trajectories related to the use of adherence partners, the timing of these questions varied by participant.

Figure 1.

Key questions guiding adherence partner acceptability data collection and analysis.

The study team developed structured interview guides for each TIPs visit, based on formative research (Martin et al. 2016), theoretical constructs (e.g. social support, self‐efficacy, motivation), and the adherence and antenatal micronutrient supplementation literature. The interview guides included open‐ended questions about adherence partners and social support, as well as closed‐ended questions about their choices and perceived social support that could be tallied. To measure participants' perceived general social support, we administered a general social support scale at the first interview. We adapted the Functional Social Support Scale, which has been used in Eastern and Southern Africa (Antelman et al. 2001; Tsai et al. 2012), using cognitive interviews in Kenya and Ethiopia. We categorized participants' social support as low if their mean social support score reflected receiving less support than they would like. We translated, back‐translated, pretested and revised the interview guides in both countries before administration.

Participants

Women in both sites were purposively sampled to represent diversity in age, parity, ANC use and educational level. Inclusion criteria were 15 years of age and older, inadequate calcium intake and planning to remain in the study area for the next six weeks. All women invited to participate in the study agreed. In Kenya, we recruited pregnant women (16–30 weeks gestation) from their homes within the catchment areas of six health facilities. In total, 38 pregnant women agreed to participate in the study and completed interview 1; 35 participants completed interview 2; 29 completed interview 3 and 24 completed all four study visits. This attrition is because of six women giving birth during the study period, four moving out of the study area and four withdrawing from the study. In Ethiopia, we recruited pregnant women (16–28 weeks gestation) from ANC clinics and health extension workers recruited women in their homes who were not attending ANC. Exclusion criteria in Ethiopia included women who were HIV‐positive or had developmental disabilities. In total, 50 pregnant women participated in the first two interviews; 49 completed all four visits and one participant withdrew.

Data analysis

We tallied participant choices at each study visit (Dickin and Seim, 2013), and qualitatively analysed translated interview transcripts. We created a matrix noting participant adherence partner choices and experiences as well as participants' perceived general social support levels based on their general social support scale score. We assessed adherence partner acceptability by documenting pregnant women's direct experience with the intervention over time (Proctor et al. 2011).

We analysed interview transcripts thematically, using an inductive approach based on the principles of grounded theory and the constant comparative method (Strauss and Corbin 1990) using Atlas.ti qualitative analysis software (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany, version 7). Starting with the Kenya data, study team members developed an initial code list after the independent reading and coding of one participant's complete set of transcripts from all four visits. A draft codebook was created to facilitate coding consistency (Decuir‐Gunby et al. 2011; MacQueen et al. 1998), which included the code name, definition and inclusion and exclusion criteria (MacQueen et al. 1998). Two researchers (SLM, SEO) independently read and coded three participants' transcripts from all four TIPs visits. The two researchers merged the coded transcripts using Atlas.ti, which allowed codes and coded text from each interview transcript to be compared across researchers. The researchers then discussed emergent codes and any discrepancies, iteratively revising the codebook throughout the coding process. This approach continued with both researchers coding and comparing all transcripts, and meeting to discuss and revise the findings. Throughout coding, the two researchers noted common themes and key quotes and engaged in constant comparative analysis by examining similarities and differences across participants and between themes.

For the Ethiopia qualitative analysis, we followed a similar approach. A third researcher (GMC) joined the original two researchers to independently code interview transcripts for four participants using the existing codebook from Kenya and adding and revising codes as needed. The three interviewers merged and compared the coded transcripts in Atlas.ti. Once the three researchers agreed upon codes, two researchers (SEO, GMC) continued coding the remaining transcripts following the same process.

With the data from both countries, we used an inductive approach to identify emergent themes, summarizing across participants and comparing responses from different types of respondents (e.g. social support levels, adherence partner choices) and between countries. We met frequently for peer debriefings and shared findings across the study team. We deliberated about discrepancies until reaching consensus.

The Cornell University Institutional Review Board, Ethiopian Public Health Institute and Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Review Committee provided ethical approval of this study. In both countries, interviewers obtained written informed consent from all participants.

Results

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at the first adherence partner interview

| Background characteristics | Kenya (n = 35) | Ethiopia (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (range) | 24.0 (16–37) | 26.2 (18–38) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Luhya | 33 (94) | — |

| Luo | 2 (6) | — |

| Oromo | — | 50 (100) |

| Primigravid, n (%) | 5 (14) | 15 (30) |

| Gravidity, mean (range) | 2.6 (1–8) | 3.0 (1–11) |

| Education level, n (%) | ||

| None | 0 | 22 (44) |

| Did not complete primary | 12 (34) | 21 (42) |

| Completed primary | 15 (43) | 3 (6) |

| Completed secondary or higher | 8 (23) | 4 (8) |

| ANC use (at least 1 visit), n (%) | 18 (51) | 41 (82) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married/living together | 29 (83) | 47 (94) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 0 | 3 (6) |

| Never married | 6 (17) | 0 |

| Low perceived social support, n (%) | 15 (43) | 13 (26) |

Previous experience with social support for IFA supplementation

In Kenya, most participants (28/35) had not taken IFA prior to study enrollment. Among those who had taken IFA before, about half reported being supported or reminded by husbands or female relatives. In contrast, most participants in Ethiopia had taken IFA prior to study enrollment (38/50). Among those who had taken IFA before, almost all reported being encouraged to take IFA and about half reported being reminded by husbands, children, other family members or friends.

My husband usually reminded me every time. He said, ‘Take that medicine [IFA], it will help you.’

– 24‐year‐old primigravida, Kenya

A few women recognized the importance of having support based on their previous IFA experience, while a few others reported their previous IFA experience increased their confidence in their ability to adhere to the calcium and IFA regimen.

I can remember by myself. I now have a lot of experience taking iron. That is why I say I don't need help from others.

– 22‐year‐old multigravida, Ethiopia

Willingness to try an adherence partner

Most women in Kenya (28/35) and in Ethiopia (42/50) were willing to try an adherence partner.

I will ask my husband because this is our common concern; my health problem will have an effect on him. This baby belongs to both of us; I think he will remind me for the sake of the baby in the womb.

– 26‐year‐old primigravida, Ethiopia

However, in both countries, several participants declined to select an adherence partner. In Kenya, almost all who declined (7/35) stated they did not need help with their supplements; one reported not having anyone to ask. In Ethiopia, among the women who declined an adherence partner (8/50), half felt they did not need help or that others might discourage them and the other half reported they had no one to ask.

It is just me… My husband never bothers with these tablets. He just knows that I take medicine. Who will come to ask that you are taking which tablets? It's just me.

– 25‐year‐old multigravida, Kenya

Actually trying an adherence partner

Most women in Kenya (20/29) and Ethiopia (42/50) followed through and asked someone to be their adherence partner. In Kenya, most women asked their husbands, and the remaining few asked female relatives or children. In Ethiopia, half asked their husbands, one quarter asked their children, and most others asked female or male relatives. Several women in both countries asked multiple people to support them.

Many helped me, many encouraged me…I was happy that many were on my side. They were also happy to encourage me to continue.

– 21‐year‐old primigravida, Kenya

Some women only shared information about their supplements with their husbands.

I told my husband about the importance of the pills; how they are useful to my health and to my fetus…he reminds me to take them…My in‐laws don't know anything about the pills I am taking.

– 28‐year‐old multigravida, Ethiopia

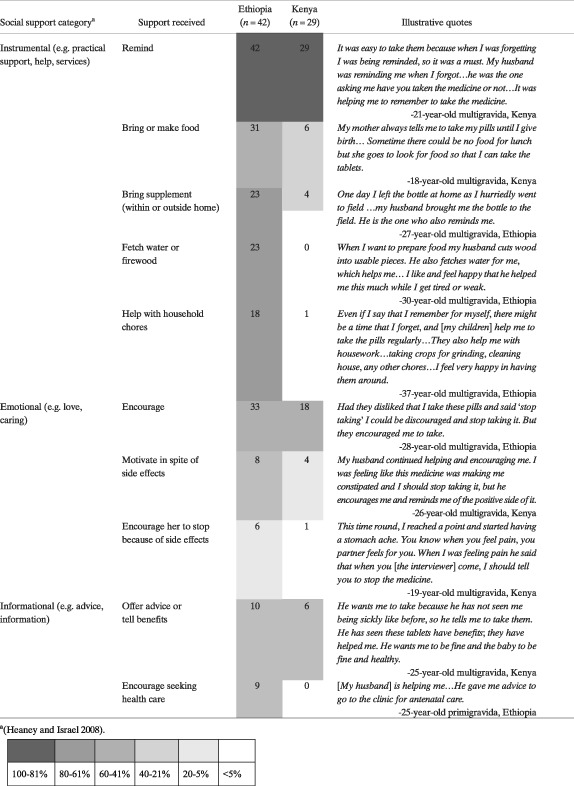

In both Kenya and Ethiopia, the majority of participants reported that their adherence partners reminded and encouraged them to adhere to their supplements. Participants spontaneously reported that adherence partners provided a variety of types of support, which we classified as instrumental, emotional and informational (Heaney and Israel 2008), and we compared support received across countries (Table 2). The most frequently mentioned examples were of instrumental support, but women also received some informational and emotional support.

Table 2.

Types of social support received by women with adherence partners in Kenya and Ethiopia

(Heaney and Israel 2008).

Most women with adherence partners reported being satisfied with the support their adherence partners provided and wanting them to continue.

I liked having my husband help me. I could have forgotten had he not been helping me.

– 22‐year‐old multigravida, Ethiopia

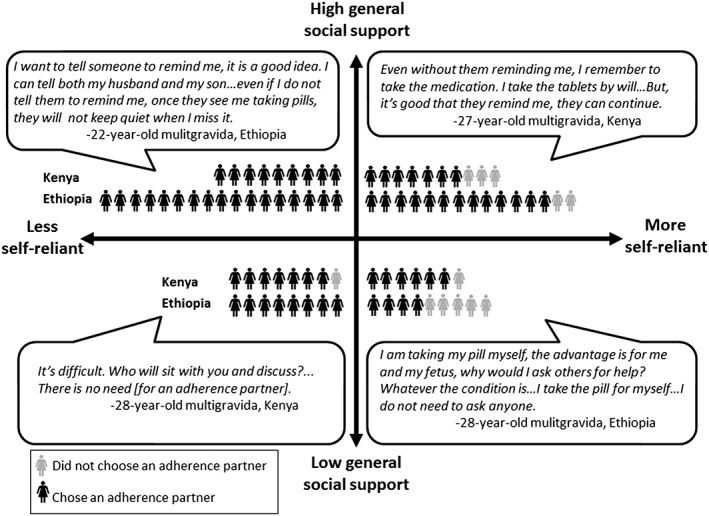

Self‐reliance and adherence partner uptake

One theme that emerged among several women in Kenya and Ethiopia was their feeling that they did not need support to take supplements; we used the term self‐reliant to describe these women. For some women, this self‐reliance resulted in not choosing an adherence partner. For some others, despite feeling self‐reliant, they still reported receiving and appreciating support. To understand the relationship between participants' feelings of self‐reliance and perceived social support, we used participants' general social support scale scores from the first interview to categorize participants' perceived social support (i.e. high or low) and their expressed feelings of self‐reliance (i.e. more or less) at any of the visits, which was coded in the qualitative analysis. We then used these categories to examine participants' adherence partner decisions (Fig. 2). Participants who appeared more self‐reliant had adherence partners less often than participants who appeared less self‐reliant; this was especially the case for women in Ethiopia with low perceived social support.

Figure 2.

Participants' adherence partner decision by levels of perceived social support and expressed feelings of self‐reliance.

Sustaining the use of an adherence partner

At the final interview, most participants reported they continued to have an adherence partner (Kenya 20/24 and Ethiopia 41/49) and most participants with adherence partners appreciated the support they received.

I want my husband to continue…He reminds me if I have forgotten, brings them to me, gives me heart, and when he sees I have given up, gives me morale to continue…You know if someone loves and cares, he will help remind you about something concerning your life.

– 26‐year‐old multigravida, Kenya

However, for some participants, the support received and its value changed over time. In Ethiopia, a few women reported no longer needing support as they had become accustomed to the supplements. In both countries, a few reported their adherence partners stopped reminding them as time passed, either because they were no longer living together or the partner discontinued support.

I am already adapted with pill taking. I don't want support. Previously, during the first two weeks, my husband was reminding me…but he has already forgotten and has not said anything to me.

– 20‐year‐old multigravida, Ethiopia

One woman in Ethiopia reported the support she received increased over time.

Initially I took it independently without others help. I remembered to take them myself. My family encouraged me after they saw my health improve.

– 27‐year‐old multigravida, Ethiopia

Several participants highlighted the importance of having adherence partners nearby and available at key times.

If my family was far, I could have forgotten to take the tablets. It helped that they were always by my side. They give me a lot of support to take the tablets.

– 27‐year‐old multigravida, Kenya

However, others had problems with partners' schedules.

I asked my husband. Mostly he reminded me to take my pills…especially in the evening. But the problem was that he works early in the morning and comes home in the evening…So, it is difficult to always get him due to the nature of his job.

– 27‐year‐old multigravida, Ethiopia

Some women relied on their adherence partners at times when they needed the most support (e.g. when they were busy, tired, or away from home), which varied by participant.

I told both my children to remind me to take the evening pills. I can remember the other. [The evening is] difficult because I could forget as we sit together and talk during the night.

– 38‐year‐old multigravida, Ethiopia

One participant reported that her husband focused his support based on side‐effects she attributed to IFA.

I am comfortable taking the white pill [calcium]. I do not need encouragement and reinforcement. I do not forget and never miss the time. But, I hate the red pill [IFA]. That is why he is checking the red pill only; he knows I do not miss the white pill.

– 19‐year‐old primigravida, Ethiopia

Recommending adherence partners to others

Almost all participants said they would recommend an adherence partner to other pregnant women.

I can tell my close friends…‘Have someone remind you to take the pills on time’…Yes, it is good to have this kind of person because it is common to forget pill‐taking time.

– 19‐year‐old primigravida, Ethiopia

Some participants suggested they could serve in this role. A few participants in Ethiopia said they would not recommend adherence partners to other pregnant women; they did not want to talk with others because pill taking was associated with HIV, and they did not want to be stigmatized.

I would not recommend others have someone remind them because people say different things about it… I personally do not share anything with anyone about the pill I am taking.

– 28‐year‐old multigravida, Ethiopia

Adherence partners and reported influence on adherence

Most participants reported that having an adherence partner helped them adhere to their calcium and IFA regimen. In Ethiopia, participants identified being reminded as the most important adherence facilitator, and in Kenya, it was one of the most important.

They all encouraged me to take [the supplements] and that is why it was hard for me to forget. Because they reminded me every time, I never missed taking them.

– 34‐year‐old multigravida, Kenya

Discussion

This study assessed the acceptability of adherence partners by examining pregnant women's decisions to try an adherence partner in the context of receiving and trying calcium and IFA supplements, and describing their experiences over time. Our results suggest a high level of acceptance for adherence partners.

Adherence partner acceptability

In Kenya and Ethiopia, most participants agreed to try, actually tried and continued to have an adherence partner throughout the study. In addition, participants reported appreciating the support they received and wanting it to continue. Participants usually chose their husbands, but children and adult female family members also served as adherence partners. Other studies examining the use of partners found participants often selected family members (Andreson et al. 2013; Nachega et al. 2006). Family members influence antenatal IFA adherence (Aguayo et al. 2005; Nagata et al. 2012) and the importance of engaging them for improved health and nutrition practices is well documented (Aubel 2012; Affleck and Pelto 2012; Birmeta et al. 2013; Mukuria et al. 2016; Pelto and Armar‐Klemesu 2015). Adherence partners are a potential strategy to engage family members to support antenatal micronutrient supplementation.

Participants received a range of instrumental, emotional and informational support from their adherence partners; reminders and encouragement were the most common. This is similar to other studies in sub‐Saharan Africa that report ‘treatment partners,’ ‘treatment supporters’ or ‘buddies’ provide reminders (O'Laughlin et al. 2012; Nachega et al. 2006) and encouragement (Nachega et al. 2006; Andreson et al. 2013). Participants noted that it was important for adherence partners to be available and nearby, which is consistent with results from similar studies (Andreson et al. 2013; Nachega et al. 2006; Idoko et al. 2007). Women also reported their adherence partner's support helped them adhere to the calcium and IFA regimen and overcome perceived side‐effects.

Although adherence partners were acceptable to most participants, this research identified potential issues that should be considered before implementation. Some participants did not select an adherence partner; several of these women cited not needing adherence support and a few others reported not having anyone to ask. When counselling women about the adherence partner strategy, it will be important to consider their levels of self‐reliance and access to social support. Women lacking social support will need targeted, comprehensive strategies because they are likely to be more vulnerable and socially isolated (Peterson et al. 2002). Self‐reliance, even more than available social support, appeared to influence the decision to have an adherence partner. The relationship between self‐reliance and adherence to antenatal micronutrient supplements requires further examination. One study of medication adherence found self‐reliance predicted lower adherence (Insel et al. 2006). Understanding how self‐reliance influences antenatal micronutrient adherence could help inform tailored adherence strategies.

When initially offered an adherence partner, a few women declined because they understood the concept to suggest asking someone outside of their immediate family. In the future, giving pregnant women printed materials that describe and illustrate this role or identifying an appropriate term could increase understanding. We endeavoured to identify an idiomatic term for adherence partners during interviews in both study sites; however no terms in Afan Oromo or Kiswahili were discovered. Even though referring to this strategy as ‘someone who could remind and encourage’ was clear for most participants, it may be important to find an idiomatic term in other contexts.

Some of our results suggest it could be beneficial to directly target adherence partners. While the social support provided by adherence partners generally promoted adherence and helped women continue despite perceived side‐effects, for a few women in both settings who perceived severe side‐effects, their adherence partners' support resulted in discouraging supplement use. In addition, a few participants reported support from their adherence partner waned over time, similar to a trial in Nigeria that reported ‘treatment partner fatigue’ (Taiwo et al. 2010). Both of these issues could potentially be addressed by engaging adherence partners directly to familiarize them with ways to support pregnant women to overcome perceived side effects and the importance of continued support throughout pregnancy. Other partner interventions have included training or orientation for partners (Idoko et al. 2007; Andreson et al. 2013; Nachega et al. 2010). While this could make adherence partners more successful, the additional resources required would limit the potential for scaling up adherence partner programmes and complicate implementation. Adherence partners offer a low‐resource strategy that leverages existing social support to overcome challenges to adherence. Our results suggest that allowing women to select partners from their social networks who are nearby and available increases the acceptability and sustainability of this strategy. Adherence partners are a promising intervention found to be acceptable to and valued by most women in two different contexts.

Differences between Kenya and Ethiopia

Adherence partners were acceptable for most participants in Kenya and Ethiopia, but there were differences between participants' experiences in these two sites. The cultural context influenced the types and amounts of support that pregnant women received, independent of the adherence partner intervention. While all participants with adherence partners reported being reminded and most reported being encouraged, pregnant women in Ethiopia received a wider variety of social support than pregnant women in Kenya. Women in Ethiopia reported high levels of instrumental support (e.g. help with chores, receiving food) from their adherence partners that extended beyond support for adherence. Traditionally, Oromo women are well supported during the perinatal period (Hussein 2004), which was confirmed in our formative research. Although women in Kenya reported being encouraged and reminded to take their supplements, they did not report receiving similar levels of additional support. Some women in Kenya reported receiving food, but only one received help with chores. In our formative research in Kenya, health workers and women reported low levels of support for pregnant women (Martin et al. 2016). In Tanzania, one study of a treatment partner intervention to increase adherence to antiretroviral therapy reported partners provided additional support beyond adherence (O'Laughlin et al. 2012). Ideally, adherence partners would provide increased support for women in several aspects of their pregnancy; however, we only found this in Ethiopia, a context where pregnant women tend to be better supported. Expectations of social support in pregnancy may affect the types of support adherence partners provide.

Another difference between the two sites was the selection of children as adherence partners. In Ethiopia it was much more common for participants to ask their school‐aged children; children offered reminders, brought supplements, and helped with chores, whereas nearly all women in Kenya chose their husbands. Children appeared to be acceptable adherence partners for women in Ethiopia. There are examples of programmes successfully engaging school‐aged children to share health messages and promote health practices within families (Onyango‐Ouma et al. 2005; Christensen 2004).

This study was designed to explore emergent themes related to the acceptability of adherence partners to support antenatal micronutrient supplementation. We documented women's social support and experiences with adherence partners for six weeks, comparing across two contexts and using quantitative data for triangulation; however, it is possible this did not capture related changes that occurred during the remaining weeks of pregnancy. While some participants in Kenya were lost to follow‐up, primarily because of giving birth before completing final interviews, the majority of participants completed two follow‐up visits and almost all completed at least one. The remaining participants in Kenya reflected the characteristics of our purposive sampling scheme and provided diverse responses suggesting we achieved sample extensiveness (Sobal 2001). There was almost no loss to follow‐up in Ethiopia. Delivering calcium and IFA supplements and counselling through multiple home visits facilitated collection of in‐depth data on women's experiences and perceptions; a next step will be assessing the acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness of delivering this strategy through facility‐based ANC throughout pregnancy.

Conclusion

Acceptable, low‐cost, scalable social and behaviour change strategies to support adherence to antenatal micronutrient supplements are needed to reduce maternal and child morbidity and mortality. Adherence partners are one potential strategy to increase adherence to antenatal calcium and IFA supplements. Adherence partners were acceptable for most women in these two settings, even in the context of limited family support in Kenya and low ANC attendance in Ethiopia. Given the high levels of acceptability among pregnant women in Kenya and Ethiopia, the effectiveness of adherence partners to improve adherence to antenatal micronutrient supplements should be explored further in future research embedded in routine health services. Adherence partners would be most effective as part of a comprehensive programme that addresses the multilevel and multifaceted barriers to antenatal micronutrient supplementation, offering a low‐cost strategy with the potential to support a variety of maternal and child nutrition interventions.

Source of funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Micronutrient Initiative and the Sackler Institute for Nutrition Science at the New York Academy of Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributions

KLD, RJS, SLM, MOO, GMC, ZB and GP contributed to study design; MOO and ZB oversaw data collection; SLM, SEO, GMC and KLD conducted data analysis; SLM drafted the manuscript. All co‐authors participated in data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the women in Ethiopia and Kenya who participated in this study and shared their experiences with us. We appreciate the commitment of the data collectors and the support of the Malava Sub‐county Health Management Team in Kenya and local administrators and health authorities in Ethiopia, as well as implementation support from Girma Mamo and Jacqueline Kung'u (Micronutrient Initiative). Conversations with Kiersten Israel‐Ballard (PATH) about infant feeding buddies influenced the adherence partner concept. Comments from Elizabeth Fox, Kathleen Rasmussen, Roseanne Schuster, Jeffery Sobal and Djeinam Toure (Cornell University); and Brie Reid (University of Minnesota) improved this manuscript.

Martin, S. L. , Omotayo, M. O. , Chapleau, G. M. , Stoltzfus, R. J. , Birhanu, Z. , Ortolano, S. E. , Pelto, G. H. , and Dickin, K. L. (2017) Adherence partners are an acceptable behaviour change strategy to support calcium and iron‐folic acid supplementation among pregnant women in Ethiopia and Kenya. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13: e12331. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12331.

References

- Affleck W. & Pelto G. (2012) Caregivers' responses to an intervention to improve young child feeding behaviors in rural Bangladesh: a mixed method study of the facilitators and barriers to change. Social Science & Medicine 75, 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo V.M., Koné D., Bamba S.I., Diallo B., Sidibé Y., Traoré D. et al. (2005) Acceptability of multiple micronutrient supplements by pregnant and lactating women in Mali. Public Health Nutrition 8, 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreson J., Dana N., Hepfer B., King'ori E., Oketch J., Wojnar D. et al. (2013) Infant feeding buddies: a strategy to support safe infant feeding for HIV‐positive mothers. Journal of Human Lactation 29, 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antelman G., Fawzi M.C.S., Kaaya S., Mbwambo J., Msamanga G.I., Hunter D.J. et al. (2001) Predictors of HIV‐1 serostatus disclosure: a prospective study among HIV‐infected pregnant women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS 15, 1865–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubel J. (2012) The role and influence of grandmothers on child nutrition: culturally designated advisors and caregivers. Maternal & Child Nutrition 8, 19–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter J.‐A.B., Roth D.E., Al Mahmud A., Ahmed T., Islam M. & Zlotkin S.H. (2014) Tablets are preferred and more acceptable than powdered prenatal calcium supplements among pregnant women in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Journal of Nutrition 144, 1106–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta Z.A., Das J.K., Rizvi A., Gaffey M.F., Walker N., Horton S. et al. (2013) Evidence‐based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? The Lancet 382, 452–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmeta K., Dibaba Y. & Woldeyohannes D. (2013) Determinants of maternal health care utilization in Holeta town, central Ethiopia. BMC Health Services Research 13, 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Agency & ICF International (2012) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Central Statistical Agency and ICF International: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen P. (2004) The health‐promoting family: a conceptual framework for future research. Social Science & Medicine 59, 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decuir‐Gunby J.T., Marshall P.L. & Mcculloch A.W. (2011) Developing and using a codebook for the analysis of interview data: an example from a professional development research project. Field Methods 23, 136–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dickin K., Griffiths M. & Piwoz E. (1997) Designing by Dialogue: A Program planners' Guide to Consultative Research for Improving Young Child Feeding. Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Dickin K.L. & Seim G. (2013) Adapting the trials of improved practices (TIPs) approach to explore the acceptability and feasibility of nutrition and parenting recommendations: what works for low‐income families? Maternal & Child Nutrition 11, 897–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway R., Dusch E., Elder L., Achadi E., Grajeda R., Hurtado E. et al. (2002) Women's perceptions of iron deficiency and anemia prevention and control in eight developing countries. Social Science & Medicine 55, 529–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebremedhin S., Samuel A., Mamo G., Moges T. & Assefa T. (2014) Coverage, compliance and factors associated with utilization of iron supplementation during pregnancy in eight rural districts of Ethiopia: a cross‐sectional study. BMC Public Health 14, 607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney C.A. & Israel B.A. (2008) Social networks and social support In: Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice (eds Glanz K., Rimer B.K. & Viswanath K.), pp. 189–210. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeyr G.J., Belizán J.M., Von Dadelszen P. & Calcium Pre‐Eclampsia Study Group (2014) Low‐dose calcium supplementation for preventing pre‐eclampsia: a systematic review and commentary. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 121, 951–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeyr G.J., Lawrie T.A., Atallah A.N. & Duley L. (2010) Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8, CD001059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein J.W. (2004) A cultural representation of women in the Oromo society. African Study Monographs 25, 103–147. [Google Scholar]

- Idoko J., Agbaji O., Agaba P., Akolo C., Inuwa B., Hassan Z. et al. (2007) Direct observation therapy‐highly active antiretroviral therapy in a resource‐limited setting: the use of community treatment support can be effective. International Journal of STD & AIDS 18, 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imdad A., Jabeen A. & Bhutta Z.A. (2011) Role of calcium supplementation during pregnancy in reducing risk of developing gestational hypertensive disorders: a meta‐analysis of studies from developing countries. BMC Public Health 11, S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel K.C., Reminger S.L. & Hsiao C.P. (2006) The negative association of independent personality and medication adherence. Journal of Aging and Health 18, 407–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics & ICF International (2015) Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Nairobi: Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni B., Christian P., Leclerq S.C. & Khatry S.K. (2010) Determinants of compliance to antenatal micronutrient supplementation and women's perceptions of supplement use in rural Nepal. Public Health Nutrition 13, 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen K.M., Mclellan E., Kay K. & Milstein B. (1998) Codebook development for team‐based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods 10, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Maina‐Gathigi L., Omolo J., Wanzala P., Lindan C. & Makokha A. (2013) Utilization of folic acid and iron supplementation services by pregnant women attending an antenatal clinic at a regional referral hospital in Kenya. Maternal and Child Health Journal 17, 1236–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S.L., Seim G.L., Wawire S., Chapleau G.M., Young S.L. & Dickin K.L. (2016) Translating Formative Research Findings into a Behaviour Change Strategy to Promote Antenatal Calciumand Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation in Western Kenya. Maternal & Child Nutrition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Initiative Micronutrient. (2015) Integrated nutrition solutions: The Micronutrient Initiative's community‐based maternal and newborn health and nutrition project in sub‐Saharan Africa. Available at: http://micronutrient.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Integrated-Nutrition-Solutions-CBMNHN-web.pdf (Accessed January 12, 2016).

- Mukuria A.G., Martin S.L., Egondi T., Bingham A. & Thuita F.M. (2016) The role of social support in improving child feeding practices in western Kenya: a quasi‐experimental study. Global Health: Science and Practice 4, 55–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachega J.B., Chaisson R.E., Goliath R., Efron A., Chaudhary M.A., Ram M. et al. (2010) Randomized controlled trial of trained patient‐nominated treatment supporters providing partial directly observed antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 24, 1273–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachega J.B., Knowlton A.R., Deluca A., Schoeman J.H., Watkinson L., Efron A. et al. (2006) Treatment supporter to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV‐infected South African adults: a qualitative study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 43, S127–S133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata J.M., Gatti L.R. & Barg F.K. (2012) Social determinants of iron supplementation among women of reproductive age: a systematic review of qualitative data. Maternal & Child Nutrition 8, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Laughlin K., Wyatt M., Kaaya S., Bangsberg D. & Ware N. (2012) How treatment partners help: social analysis of an African adherence support intervention. AIDS and Behavior 16, 1308–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omotayo M., Dickin K., O'Brien K., Neufeld L., De‐Regil L. & Stoltzfus R. (2016) Calcium supplementation to prevent preeclampsia: translating guidelines into practice in low‐income countries. Advances in Nutrition 7, 275–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omotayo M.O., Dickin K.L., Chapleau G.M., Martin S.L., Chang C., Mwanga E.O. et al. (2015) Cluster‐randomized non‐inferiority trial to compare supplement consumption and adherence to different dosing regimens for antenatal calcium and iron‐folic acid supplementation to prevent preeclampsia and anaemia: rationale and design of the Micronutrient Initiative study. Journal of Public Health Research 4 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyango‐Ouma W., Aagaard‐Hansen J. & Jensen B. (2005) The potential of schoolchildren as health change agents in rural western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine 61, 1711–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelto G.H. & Armar‐Klemesu M. (2015) Identifying interventions to help rural Kenyan mothers cope with food insecurity: results of a focused ethnographic study. Maternal & Child Nutrition 11, 21–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña‐Rosas J., De‐Regil L., Dowswell T. & Viteri F. (2012) Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 12 CD004736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson K., Sorensen G., Pearson M., Hebert J.R., Gottlieb B. & Mccormick M. (2002) Design of an intervention addressing multiple levels of influence on dietary and activity patterns of low‐income, postpartum women. Health Education Research 17, 531–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A. et al. (2011) Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 38, 65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remien R.H., Stirratt M.J., Dolezal C., Dognin J.S., Wagner G.J., Carballo‐Dieguez A. et al. (2005) Couple‐focused support to improve HIV medication adherence: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS 19, 807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi T.G., Harvey P.W. & Wainwright E. (2010) Maternal iron–folic acid supplementation programs: evidence of impact and implementation. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 31, 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seck B.C. & Jackson R.T. (2008) Determinants of compliance with iron supplementation among pregnant women in Senegal. Public Health Nutrition 11, 596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J. (2001) Sample extensiveness in qualitative nutrition education research. Journal of Nutrition Education 33 (4), 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltzfus R.J. (2011) Iron interventions for women and children in low‐income countries. Journal of Nutrition 141, 756S–762S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A.L. & Corbin J.M. (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwo B.O., Idoko J.A., Welty L.J., Otoh I., Job G., Iyaji P.G. et al. (2010) Assessing the viorologic and adherence benefits of patient‐selected HIV treatment partners in a resource‐limited setting. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 54, 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taye B., Abeje G. & Mekonen A. (2015) Factors associated with compliance of prenatal iron folate supplementation among women in Mecha district, Western Amhara: a cross‐sectional study. The Pan African Medical Journal 20, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Manoff Group . (2005) Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs): Giving Participants a Voice in Program Design. Washington, DC: Available at: http://www.manoffgroup.com/resources/ summarytips.pdf (Accessed on January 29, 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Tsai A.C., Bangsberg D.R., Frongillo E.A., Hunt P.W., Muzoora C., Martin J.N. et al. (2012) Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine 74, 2012–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unge C., Sodergard B., Marrone G., Thorson A., Lukhwaro A., Carter J. et al. (2010) Long‐term adherence to antiretroviral treatment and program drop‐out in a high‐risk urban setting in sub‐Saharan Africa: a prospective cohort study. PloS One 5 e13613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willardson S.L., Dickerson T.T., Stucki Wilson J., Ansong D., Bueler E., Boakye I. et al (2013) Forming a supplement intervention using a multi‐theoretical behavior model. American Journal of Health Behavior 37, 831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2013) Guideline: Calcium Supplementation in Pregnant Women. World Health Organization: Geneva. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip R. (2002) Iron supplementation: country level experiences and lessons learned. Journal of Nutrition 132, 859S–861S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavaleta N., Caulfield L.E., Figueroa A. & Chen P. (2014) Patterns of compliance with prenatal iron supplementation among Peruvian women. Maternal & Child Nutrition 10, 198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]