Abstract

There are limited data available about the prevalence of human milk (HM) sharing and selling in the general population. We aimed to describe attitudes toward HM selling among participants in a qualitative‐interview study and prevalence of HM sharing and selling among a national sample of U.S. mothers. Mothers (n = 41) in our qualitative‐interview study felt that sharing or donating HM was more common than selling; none had ever purchased or sold HM. Three themes related to HM selling emerged from this work: questioning the motives of those selling HM, HM selling limits access to HM to those with money, and HM selling is a legitimate way to make money. Some mothers had reservations about treating HM as a commodity and the intentions of those who profit from the sale of HM. Nearly all participants in our national survey of U.S. mothers (94%, n = 429) had heard of infants consuming another mother's HM. Approximately 12% had provided their milk to another; half provided it to someone they knew. Fewer mothers (6.8%) reported that their infant had consumed another mother's HM; most received this HM from someone they knew. A smaller proportion of respondents (1.3%) had ever purchased or sold HM. Among a national sample of U.S. mothers, purchasing and selling HM was less common than freely sharing HM. Together, these data highlight that HM sharing is not uncommon in the United States. Research is required to create guidelines for families considering HM sharing.

Keywords: breast milk sharing, human milk, human milk selling, human milk sharing, national survey, qualitative methods

Key messages.

Insights from our qualitative study suggest that mothers may have reservations about treating human milk (HM) as a commodity and the intentions of those who profit from the sale of HM.

The proportion of mothers who freely received or provided HM was considerably higher in our sample of U.S. mothers, at nearly 17%, than the 4% previously reported among a sample of mothers from Ohio. However, the prevalence of purchasing and selling HM among our sample (1.3%) was lower than the prevalence of freely providing or receiving HM.

The combinations of routes for providing and receiving HM outlined in this paper highlight that how mothers share HM is now considerably more complex than it has been historically.

The high prevalence of informal HM sharing observed in our sample of U.S. women is of interest given that the Food and Drug Administration recommends against the behaviour.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding is actively promoted by the World Health Organization as the optimal way to feed infants from birth to 6 months, with the introduction of complementary foods at 6 months and continued breastfeeding to 2 years or more (Kramer & Kakuma, 2012). Before infant formula became widely available in the early 20th century, women who could not—or did not want to—feed their infant at the breast could solicit the services of a wet‐nurse (Golden, 1996), which was often recommended or organized by a medical professional (Wolf, 1999). At present, wet‐nursing has fallen out of fashion (Golden, 1996), but infants are still consuming human milk (HM) from a woman other than their own mother.

Although the informal sharing of HM is not often openly discussed (Thorley, 2011), contemporary reports of women informally providing HM for infants who are not their own have been published in the scientific literature since the 1980s (Gribble, 2013; Gribble, 2014a; Krantz & Kupper, 1981; Long, 2003; Perrin, Goodell, Allen, & Fogleman, 2014; Shaw, 2007; Thorley, 2009; Thorley, 2011). Women have reported various motivations for providing and receiving HM. Motivations for providing HM are often altruistic and spring from a desire to help mothers or infants in need (O'Sullivan, Geraghty, & Rasmussen, 2016b). Motivations for receiving HM include having insufficient milk for their own child and wanting to avoid HM substitutes in the face of a short‐term challenge with at‐the‐breast feeding (O'Sullivan et al., 2016b). Milk sharing may not be discussed openly because of the negative “yuk” reaction that may be expected or received from members of the public (Shaw, 2004), or because mothers who need to obtain HM from others may perceive a sense of inadequacy at not being able to provide sufficient quantities of their own milk to their infant, as has been reported among mothers of preterm infants who received donor HM (Esquerra‐Zwiers et al., 2016).

Much of the recently published literature on HM‐sharing practices centres on mothers who have participated in the behaviour (Palmquist & Doehler, 2016; Perrin et al., 2016; Reyes‐Foster, Carter, & Hinojosa, 2015). There are limited data available about the prevalence of HM sharing in the general population. However, investigators who conducted a study among all mothers who delivered an infant at a specific hospital in Ohio over the course of 5 months in 2011 reported the awareness of and participation in HM sharing among this group of unselected women (Keim et al., 2014). Awareness of informal HM sharing was high among the 499 women who responded (approx. 77%), but participation was considerably lower—fewer than 4% of respondents (n = 19) had provided HM to another mother or received HM from another mother (Keim et al., 2014).

HM sharing has received substantial attention in the scientific literature and the media, with many scientific articles and commentaries highlighting the risks associated with the behaviour (Carter, Reyes‐Foster, & Rogers, 2015). For example, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends against informal HM sharing (US Food and Drug Administration, 2010), stating that when HM “is obtained directly from individuals or through the internet, the donor is unlikely to have been adequately screened for infectious disease or contamination risk. In addition, it is not likely that the human milk has been collected, processed, tested or stored in a way that reduces possible safety risks to the baby.”

Until recently, the evidence for the risks outlined above was minimal, but in 2012, an empirical study was initiated to explore the safety of HM purchased online as an indicator of “risk to recipient infants” (Keim et al., 2013). Several publications from this study described that milk purchased contained significant bacterial contamination (Keim et al., 2013), tobacco metabolites and caffeine (Geraghty et al., 2015), and bovine DNA (Keim et al., 2015); the last indicates contamination of the HM with cow's milk. The press coverage of this study prompted concerned editorials from academics that highlighted the risks of milk‐sharing behaviours (Eidelman, 2015; Steele, Martyn, & Foell, 2015). However, this study focused solely on HM purchased online and shipped to an address provided by the investigators. Given the variety of possible routes of informal HM sharing (O'Sullivan et al., 2016b), it cannot be assumed that the risks of freely sharing HM are equivalent.

The significant concerns expressed in the literature about the safety of HM sharing, and specifically the known risks associated with purchasing HM online, make it important to understand maternal attitudes toward purchasing and selling HM. It is also important to determine the prevalence of milk‐sharing behaviours in the general population to understand the potential public health implications of the practice.

The aim of this paper is twofold: to describe maternal attitudes toward HM sharing and selling among a select sample of mothers who had previously participated in a qualitative‐interview study about HM‐feeding practices, and to describe the awareness and prevalence of HM sharing and selling among a national sample of U.S. mothers using questionnaire data.

2. METHODS

This is a mixed‐methods study and this manuscript describes data from both a qualitative‐interview study conducted in a single geographic location and a national, cross‐sectional questionnaire study.

2.1. Qualitative study: Semi‐structured interviews

Between August 2012 and June 2014, notices were placed in paediatrics offices, local baby‐goods stores, and cafés in a city in upstate New York, and emails were sent to parenting listservs indicating that we were interested in speaking to mothers with experience of breast milk expression. Women then contacted the first author and were screened for inclusion in the study. Mothers were eligible to participate if they were over 18 years of age, had ever pumped or expressed HM and had an infant ≤3 years of age. After screening, an interview was arranged with eligible mothers. We attempted to recruit participants heterogeneous on characteristics known to be associated with human‐milk feeding (e.g., age, marital status, employment status, parity). This study included 41 mothers from four counties in upstate New York, United States, and ethical approval was obtained from Cornell University's Institutional Review Board. More detailed methods have been previously published (O'Sullivan, Geraghty, & Rasmussen, 2016a; O'Sullivan et al., 2016b).

2.1.1. Qualitative data collection

Qualitative, in‐depth, semi‐structured interviews were conducted in mothers' homes or in local cafés, depending on the participant's preference. Before commencing the interview, the purpose of the research was explained to participants, they signed an informed consent form and completed a short demographic questionnaire. The interviews took on average 58 min to complete and focused on behaviours related to at‐the‐breast feeding, human‐milk expression, and expressed‐HM feeding. All mothers were asked their opinions of informal HM sharing and most of the conversations included brief discussions about purchasing and selling HM. Mothers were provided with a $ 10 gift card as compensation for their participation in the study.

2.1.2. Qualitative data analysis

A manuscript describing maternal experiences of and attitudes toward the free, informal sharing of HM among women in this dataset has been previously published (O'Sullivan et al., 2016b). Thus, the focus of this analysis was on the themes of HM purchasing and selling; we did not have a priori codes when data analysis commenced. Data were analysed using content analysis by the first author and a research assistant. Each interview transcript was analysed iteratively and coded on the basis of the emergent themes related to purchasing and selling HM. Data analysis was discussed in weekly debriefing meetings and discrepancies in coding were discussed. ATLAS.ti version 7 software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) was used to manage qualitative analysis. We discussed our findings with two mothers who had participated in the study to request their feedback; they felt that our analysis and interpretation of the qualitative data reflected their experiences.

2.2. Quantitative study: The Questionnaire on Infant Feeding

2.2.1. Data collection

Between March and July 2015, we administered the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding (O'Sullivan & Rasmussen, 2017), a cross‐sectional, self‐administered, online questionnaire. Participants were recruited through ResearchMatch, a national health volunteer registry that was created by several academic institutions and supported by the National Institutes of Health as part of the Clinical Translational Science Award program (Harris et al., 2012). We contacted all women in the registry aged between 18 and 50 years with a recruitment message indicating that we were recruiting mothers of children aged 19–35 months to complete a questionnaire about infant and child feeding. The first page of the questionnaire explained the purpose of the study in detail and respondents were informed that participation was voluntary and confidential. Respondents read the consent information and clicked a button to provide consent to participate. Participants were compensated with a $ 5 electronic gift card for their time, which was emailed to them within 24 hr of questionnaire completion. The questionnaire was only offered in English and took 10–15 min to complete. This protocol was approved by Cornell University's Institutional Review Board.

The Questionnaire on Infant Feeding was developed by the investigators to elicit information about HM‐feeding practices in general, particularly expressed‐HM feeding, and included five questions on the prevalence and routes of both HM sharing and selling (see Table S1). We asked mothers about their awareness of infants consuming another mother's milk and where they had heard about it. We asked mothers whether they had thought about providing HM to another mother and whether they ever provided HM to another mother. For respondents who reported ever providing their HM to another mother, we asked to whom they provided the HM. We asked mothers whether they had thought about receiving HM from another mother and whether they ever received HM from another mother. For respondents who reported ever receiving HM from another mother, we asked from whom they received the HM and for how long it was fed to their infant. Predefined response options were provided on the questionnaire, developed based on insights from our qualitative work. However, an option for “other” was always available to allow mothers to respond when the predefined response options were considered unsuitable. Respondents were offered the option to provide a text comment at the end if there was any information they wanted to add.

2.2.2. Sample size

We chose our sample size to estimate the population prevalence of a rare behaviour, feeding an infant another mother's HM. Based on previous research (Keim et al., 2014), we expected that the population prevalence of HM sharing would be ~4%. Using this as the assumed true prevalence, we calculated that we would need 464 subjects to estimate the prevalence of feeding infants another mother's HM with a confidence of 95% and precision of 5%.

2.2.3. Data analysis

We calculated the proportion of mothers who ever provided their HM to another mother and the proportion of mothers who ever received HM from another mother using descriptive statistics. We used counts (n, %) to report the routes of HM sharing among our sample. The duration of infants consuming another mother's HM was calculated by subtracting the first day the infant was fed another mother's HM from the last day the infant was fed another mother's HM, giving a total duration in days. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

The 41 mothers who participated in qualitative interviews were between 21 and 42 years old, 85% were married or had a partner, 51% had a postcollege education, and 44% were primiparous.

3.1. Maternal attitudes toward HM selling: Results from qualitative interviews

Nine of the 41 (22%) mothers in our qualitative study had either freely provided their HM to another mother or received another mother's HM free of charge for their child; however, no participants had purchased or sold HM. Participants were more aware of HM sharing than selling.

“I'm more familiar with the sharing. … I've never seen anyone selling.” (Olive, provided HM to another)

“… giving it away is more … It's much more common.” (Abby, non‐sharer)

In general, mothers felt that they would be more comfortable with the idea of sharing or donating HM than selling it.

“I would probably have felt more comfortable donating it than I would selling it.” (Layla, non‐sharer)

“Personally, I mean, and financially we're not doing well. Like that would be probably a good economic move, you know, to do something like that. But at the same time, I, I just, I don't know that I could wrap my head around that. I, I think that for me it would probably have to be, I'd probably have to donate it ….” (Nicole, non‐sharer)

Three distinct themes emerged from our qualitative work specifically related to HM selling: (a) questioning the motives of those selling HM, (b) selling HM limits access to HM to those with money, and (c) selling HM is a legitimate way to make money.

3.1.1. Theme 1: Questioning the motives of those selling HM

A couple of mothers felt that if HM was to be sold, then it should be “tested” and that potential recipients were entitled to ask more detailed questions of the HM provider if there was an exchange of money involved.

“… sometimes when money is exchanged over things it can make it feel a bit more credible, so … maybe that's helpful if you're doing it on Craigslist or something. I don't know, like that you're trying to sell it and then that person feels more entitled to … get more information from you about blood records or, you know, stuff like that. Which, if in terms of getting it from someone that you don't know, is probably helpful. Or is wise I guess ….” (Holly, provided HM to another)

One mother considered this practice for screening potential HM providers more important for those who do not already know the provider.

Some participants questioned the trustworthiness of sellers, specifically expressing concerns about whether mothers selling HM were depriving their own child of HM. These concerns were specific to selling HM, and were not expressed about mothers who were freely providing HM to others.

“I'd have some concerns about background and reputability, especially if there's profit involved too. Um, so that would give me some concern, like I would not want women who should be giving milk to their own children to think that they could get more money for it elsewhere.” (Zoe, non‐sharer)

“I guess I would be curious like who are these people selling milk. Are they not feeding their babies? … It just immediately seems like they are up to no good if they're selling their breast milk.” (Olive, provided HM to another)

“I think there are a lot of issues that come up with selling milk. Like, are you … not giving your milk to your baby ….” (Uma, non‐sharer)

3.1.2. Theme 2: Selling HM limits access to HM to those with money

Several mothers expressed concern that only affluent parents would be able to afford to purchase HM, and that less‐advantaged mothers might be exploited by more‐affluent families.

“… it could be a little exploitative like, you know like surrogates are, you know like kind of. It's usually a person with money that's paying a person without money to do it ….” (Megan, non‐sharer)

“I actually believe that food is a human right … I know we have to put value on things and it costs money to make food, you know. … I think if a mother really wants to give their child breast milk, you know, then they should be able to do that even if they can't pump or if they've adopted a child or fostered a child or whatever the circumstance is.” (Nicole, non‐sharer)

Selling HM was also considered a problem as some mothers felt that infants had the “right” to receive HM or that “milk from the breast is a gift” from a mother to a child.

3.1.3. Theme 3: Selling HM is a legitimate way to make money

There were also those who responded positively about selling HM. Several mothers recognised that expressing HM requires the mother to invest time, energy, and materials. Many felt that is was appropriate for that effort to be compensated financially.

“I think it's fine to sell it, and it is you know, it's, it's a lot of work to do and I think it's, you know, fine to ask for some money for that.” (Gaby, non‐sharer)

“I find that in the States, it's so hard when you have a child, to go um, back to work or something. You know that, any money you can generate, I think it's legitimate, you know, in this day and age, quite frankly ….” (Katie, non‐sharer)

“So, if they're willing to pay for it, and there's a mom who's sitting home investing her time and, you know, and a fortune in storage bags … a little bit of financial compensation for the supplies that she's using and the amount of time that she's spending, yeah, I think that's great.” (Louise, non‐sharer)

3.2. Results from the questionnaire on infant feeding

The reliability and construct validity of this questionnaire has been described previously (O'Sullivan & Rasmussen, 2017). The questionnaire reliably measured the incidence of infant consumption of another mother's HM (i.e., the response to the question “Was [child] ever fed another mother's breast milk, even one time?”; O'Sullivan & Rasmussen, 2017). Unfortunately, the sample size of the reliability study was too small to determine the reliability of all other questions related to HM sharing, donating, and selling.

The Questionnaire on Infant Feeding was completed online by a convenience sample of 496 mothers; 40 respondents were excluded from analyses as they provided implausible responses. Thus, the final analysis includes 456 participants. Respondents to the questionnaire were predominantly white, ≥30 years of age, married, had at least a bachelor's degree, and were from all four residence regions if the U.S. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants in the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding 2015, total n = 456

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age, y | |

| <30 | 127 (28) |

| ≥30 | 329 (72) |

| Maternal education a | |

| Less than bachelor's degree | 139 (31) |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 317 (69) |

| Maternal BMI a , b, kg/m2 | |

| < 18.5 (underweight) | 15 (3) |

| 18.5–24.9 (normal‐weight) | 193 (42) |

| 25–29.9 (overweight) | 131 (29) |

| ≥ 30 (obese) | 117 (26) |

| Race | |

| White | 386 (85) |

| Black or African American | 47 (10) |

| Other | 23 (5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 28 (6) |

| Non‐Hispanic | 428 (94) |

| U.S. residence region a | |

| Northeast | 54 (12) |

| Midwest | 164 (36) |

| South | 166 (37) |

| West | 69 (15) |

| Marital status a | |

| Married | 359 (79) |

| Not married | 97 (21) |

| Infant ever participated in WIC b | |

| Yes | 117 (26) |

| No | 339 (74) |

At survey completion.

BMI = body mass index; WIC = Women, Infants, and Children, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

3.3. Awareness of infants consuming another mother's HM

Most (n = 429, 94%) mothers in this sample had heard of infants consuming another mother's HM. Of those, most had heard of infants consuming another mother's HM from a parenting website, followed by through the media and then through friends or relatives (Table 2). Of those who heard of infants consuming another mother's HM through other sources, mothers mentioned sources such as blog posts, books and historical literature, lactation consultants, and their own experiences of providing HM for other children.

Table 2.

Awareness of and participation in human milk sharing among mothers in the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding, n = 456

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Ever heard of an infant being fed breast milk from another mother | 429 (94) |

| Where participants heard about infants being fed breast milk from another mother | |

| Doctor or healthcare provider | 88 (19) |

| Friend or relative | 188 (41) |

| News, TV, radio, magazine | 193 (42) |

| Website for parents | 206 (45) |

| Website specifically about breast milk sharing | 145 (32) |

| Social media (twitter, Facebook etc.) | 180 (39) |

| Other | 39 (9) |

| Considered providing breast milk to another mother | 239 (52) |

| Provided breast milk to another mother | 54 (12) |

| Considered receiving breast milk from another mother | 98 (21) |

| Received breast milk from another mother | 31 (7) |

| Provided breast milk to another mother and received breast milk from another mother | 8 (2) |

3.4. Prevalence of providing HM to another

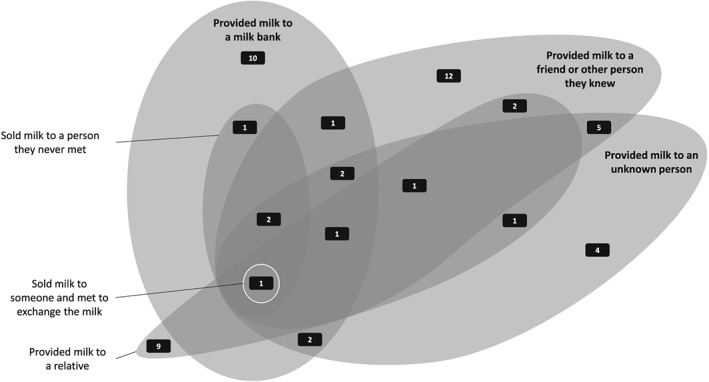

More mothers thought about providing their milk to another (52%) than considered receiving it (21%). Similarly, a higher proportion of the total sample of mothers (n = 54, 12%) provided their milk to another than received it (Table 2). Of those who provided their HM to another, most (n = 27, 60%) provided it to a friend or other person they knew, and a large proportion (n = 20, 37%) donated their HM to a milk bank (Table 3). Mothers could select more than one response option, and this revealed that several mothers provided their milk to several different people. Of the 27 mothers who provided their milk to a friend or other person they knew, 15 also provided their milk to others, including donating to a milk bank and providing milk to an unknown person (Figure 1). There was one participant who selected all response options, stating that she both freely provided her HM to several people, donated her milk to a milk bank, and sold her HM (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Routes of human milk sharing and donation among mothers in the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding who ever provided their human milk to another mother, n = 54 a

| Recipient | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Given to a friend or other person mother knew | 27 (49) |

| Donated to a milk bank | 20 (36) |

| Given to somebody mother did not know personally | 19 (35) |

| Given to a relative | 15 (27) |

| Sold milk to somebody she never met | 4 (7) |

| Sold milk and met with person to exchange | 1 (2) |

Mothers could choose more than one option.

Figure 1.

Routes through which mothers in the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding (total n = 456) provided their human milk to another

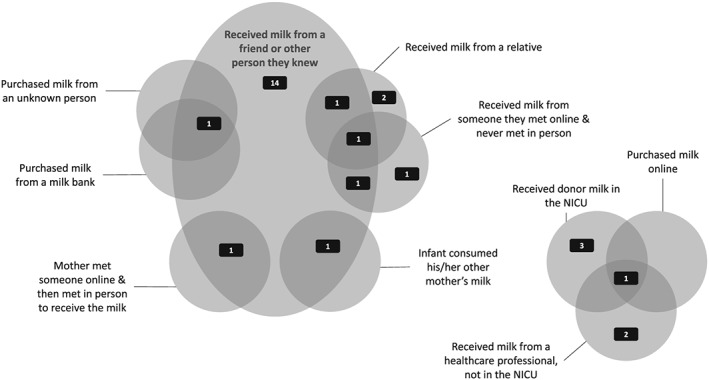

3.5. Prevalence of receiving HM from another

Nearly 7% of respondents (n = 31) had ever fed their child another mother's HM (Table 2). Of those who fed their infant another mother's HM, most (n = 20, 65%) received milk from a friend or other person the mother knew (Table 4). Mothers could select more than one response option, and this revealed that several mothers received milk from more than one source. Of the 20 who received milk from a friend or other person they knew, six received milk from another source also, including from a relative and from someone they met online but never met in person (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Source of other mother's human milk that was fed to infants in the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding, among those who ever fed their child another mother's human milk, n = 31 a

| Source | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Given by a friend or other person mother knew | 19 (59) |

| Given donor breast milk while in the NICU b | 4 (13) |

| Given by a relative | 4 (13) |

| Given by a health professional or breastfeeding support specialist (e.g., midwife, lactation consultant, nurse, breastfeeding peer counsellor) when mother and baby were home after giving birth | 3 (9) |

| Given by somebody mother met online that she never met in person | 3 (9) |

| Given by somebody mother met online that she met in person to exchange the milk c | 1 (3) |

| Given by infant's other mother who was also lactating c | 1 (3) |

| Purchased from somebody that mother did not know personally | 1 (3) |

| Purchased breast milk from somebody mother met online that she never met in person | 1 (3) |

| Purchased from milk bank c | 1 (3) |

Mothers could choose more than one option.

NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

Response volunteered by participant, not an investigator‐initiated option.

Figure 2.

Routes through which mothers in the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding (total n = 456) received human milk from another. NICU = neonatal intensive care unit

Among those who reported that their child was ever fed another mother's HM, one mother was still feeding her child another mother's HM at the time of the questionnaire. Of the remaining 30 mothers whose infants consumed another mother's HM, the median duration of infants consuming another mother's HM was 12 days (interquartile range: 77). The option to provide additional text comments at the end of the questionnaire provided some insight into the milk‐sharing behaviours of the mothers in this study. For example, there were two women who were married to each other. Both women were pregnant at the same time and their infants were born about 2 weeks apart. Both women provided HM to their biological baby and the baby of their wife. One of the women provided this perspective:

“I have two children, 16 days apart. I delivered my daughter, and my wife delivered my son 2 weeks later. We both feed both kids.”

Other mothers also provided additional text information about feeding their infant another mothers' HM:

“… my son was provided pumped breast milk from myself and a close friend with a baby the same age, as he was experiencing milk transfer issues and poor weight gain. He was diagnosed with a severe lip and tongue tie, had those revised, and within 2 weeks was off of pumped milk and back at the breast exclusively”

“I used a friend's milk mixed with cereal [because] she couldn't find anywhere to donate it locally and didn't want it to go to waste.”

“[Child] was adopted at birth when I was 5 1/2 months pregnant so I was unable to breastfeed him at first. … When my daughter was born, I was able to breast feed [Child] some as well. One of my friends donated her milk so [Child] was able to have some breast milk from her up until the point where I could give him some of my milk.”

3.6. Prevalence of both providing and receiving HM

Although 54 mothers provided their milk to another and 31 mothers received milk from another, the total number of distinct mothers who provided or received HM was 77. This is because there were eight participants who both received and provided HM. One of these was the mother mentioned above who fed both her biological child and her child her wife delivered. Additional text information provided insight into the HM‐sharing behaviours of the mothers who both received and provided HM:

“I fed [Child] my best friend's breast milk from a bottle one time. I gave 40 oz of my milk to a different friend who needed surgery and would be unable to breastfeed for 24 hours, and did not have any milk stored.”

“We were on an international trip with a friend who was pumping to keep up her supply as her babies were not on the trip. [Child] was 13 months old and drank her pumped milk as well as nursing from me —for about 1 week while we were on this trip. I gave some breastmilk in response to a request for a newly adopted baby. I didn't know the new mother but she picked it up when my son was a couple weeks old.”

3.7. Prevalence of purchasing and selling HM

Four respondents reported selling their milk to somebody they never met; one of these mothers also reported selling her milk and meeting the recipient in person to exchange the milk (Table 4). Given the wording of the questions asked (see Table S1), we cannot exclude the possibility that infants were not always the recipients of HM that was sold. Only two mothers reported purchasing milk directly from another mother who they did not know, and one of these two mothers also reported purchasing milk from a milk bank. Thus, of the 456 respondents to the questionnaire, six (1.3%) had sold or purchased HM.

4. DISCUSSION

Mothers in our qualitative study had concerns about the trustworthiness of those selling HM. Although they also expressed concerns about freely sharing HM (O'Sullivan et al., 2016b), the most salient concerns about freely sharing HM related to whether the mother's own infant had enough HM and whether the HM provider had an appropriate diet; concerns about trustworthiness of HM providers were unique to those selling HM. The concerns outlined by mothers in our qualitative study may explain why the prevalence of HM selling and purchasing was considerably lower than freely providing or receiving HM among respondents to the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding. Although there were mothers in our qualitative study who felt that women who expend the effort to express excess milk should be compensated for it, and these mothers had no problem with the idea of a mother selling HM, none of these mothers had purchased HM and it is unclear whether they would be willing to feed their infant purchased HM. It is noteworthy that this qualitative study was conducted among mothers who had experience with HM expression, and it is possible that this select group of women are more understanding than most of the time and effort involved in HM expression. Additionally, a high proportion of mothers in our qualitative sample (9/41) had experience with HM sharing, which may relate to the geographic location where interviews were conducted, and may mean that their opinions do not reflect the experiences of the general population.

It remains important that the concerns expressed by mothers about purchasing and selling HM may not necessarily be the same as those expressed by public health officials and academics, who often express concern about the potential for disease transmission (Eisenhauer, 2016). When they questioned the motivations of mothers selling their HM, mothers in this study were most concerned that mothers selling their HM might not be providing it to their own infant. They did not express concern that the milk might be contaminated or may have been mixed with another substance to inflate the volume for financial gain. The dilution of HM with cow's milk to boost the volume—and thus, the potential profit—has been proposed as an explanation for the previously described cow's milk contamination of HM purchased online (Keim et al., 2015).

Among a national sample of U.S. mothers who responded to the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding, >90% were aware of infants consuming another mother's HM; this is higher than previously reported among mothers from Ohio (Keim et al., 2014). Participation in HM sharing (the proportion of mothers receiving or providing HM) was considerably higher in this sample, at nearly 17%, than the 4% previously reported (Keim et al., 2014). Participation in informal HM sharing among this national sample of mothers remained high at 14% (n = 64) even when we exclude those who only provided HM to a milk bank (n = 10, 2.2% of all respondents) and those who only received donor HM while their infant was in the neonatal intensive care unit (n = 3, 0.7% of all respondents). The proportion of mothers who purchased or sold HM was much smaller, at just over 1%, which is in accord with previous research (Palmquist & Doehler, 2016; Reyes‐Foster et al., 2015) conducted among women who participated in HM sharing; these authors also described freely sharing HM as more common than purchasing or selling HM.

The combinations of routes for providing and receiving HM outlined in this paper highlight that how mothers share HM is now considerably more complex than it was when the use of wet nurses was common. Although infants have been consuming other mother's milk through direct at‐the‐breast feeding since time immemorial (Fildes, 1987), technological innovations such as refrigeration and high‐efficiency breast pumps now enable infants to consume another mother's expressed HM from a bottle. These innovations have the potential to increase the number of mothers and possible geographic locations from which shared HM is sourced (Boyer, 2010), which may be further enabled by websites for HM sharing.

The low prevalence of HM selling and purchasing observed in the sample of mothers who responded to the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding may be encouraging to public health officials, as this is often considered the practice of greatest concern. However, the high prevalence of informal HM sharing will likely be of public health interest given that the FDA recommends against the behaviour (US Food and Drug Administration, 2010). It is also of interest because—although there are limited scientific data available about the risks of HM sharing—the potential risks are often cited in the scientific literature (Eidelman, 2015; Steele et al., 2015) and in articles published in magazines targeted at healthcare professionals (Bond, 2008; Nelson, 2012). Despite the concerns expressed in such publications, mothers are informally providing and receiving HM, and they are currently doing so with minimal guidance from healthcare professionals. The emphasis placed on the risks associated with HM sharing has previously been described as problematic (Gribble & Hausman, 2012) as there are also risks associated with feeding infant formula, but organizations like the FDA do not recommend against feeding infant formula. Instead, parents are provided with guidance on how to manage the risks associated with formula feeding. Gribble and Hausman (2012) recommend that healthcare professionals also provide families with information on strategies for minimizing the risks associated with HM sharing, instead of simply advising against this infant‐feeding strategy, although they admit much more research needs to be done before such guidelines can be developed.

It is likely that families would be receptive to information about reducing the risks associated with HM sharing, as many mothers involved in HM sharing are already engaging in risk‐minimization strategies. Risk management among women recruited through Facebook who had participated in online HM sharing has been explored (Gribble, 2014b); of the mothers in this study who informally received HM online, all took at least some action to mitigate the risk of receiving HM through the internet. Purported risk‐minimization strategies included asking questions of the HM providers, seeking medical records, and getting to know the provider (Gribble, 2014b). A similar type of screening of potential HM providers was also reported by investigators who conducted a large online questionnaire among mothers who had either provided or received HM (Palmquist & Doehler, 2016). Among mothers who completed this questionnaire, perceptions of risk, and thus, the extent to which milk providers were screened, were lower when potential HM providers had a social connection to the recipient (Palmquist & Doehler, 2016). This is reflected in our own qualitative work (O'Sullivan et al., 2016b), as mothers reported that they would be more likely to participate in HM sharing with a relative or friend.

Although the limited data we do have about the risks associated with infants consuming another mother's HM come from a study reporting the composition of HM purchased online—which reflects the “worst‐case scenario” (Steube, Gribble, & Palmquist, 2014) for HM sharing—it is the only study currently available that has reported on the risks of infants consuming another mother's HM, and it only explored HM that was purchased. Given the description of the contamination of HM in the study by Keim and colleagues, knowing the provider or asking them personal questions to get to know them may be an insufficient strategy to minimize risk, particularly if HM is being purchased from an unknown person. Investigators have reported that practices for hygienic handling of milk when expressing and storing it are suboptimal among the general population as 30% never sterilized their pump collection kit (Labiner‐Wolfe & Fein, 2013), and among mothers who provide their HM to others as about 60% reported at least one unsafe milk‐handling practice (Reyes‐Foster, Carter, & Hinojosa, 2017), reflecting the observations made in the general population. However, it is unclear how often these practices lead to infant illness. Unfortunately, the benefits and risks of freely sharing HM—which is more common than purchasing and selling HM—have not yet been explored, which represents a significant gap in the literature.

5. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The use of both qualitative and quantitative methods is a strength of this study. Awareness and prevalence of HM sharing was high in both our qualitative and quantitative studies, which indicates that this is a widespread practice. The questionnaire we conducted was also the first questionnaire completed by a national, although not nationally representative, sample of mothers who were not specifically recruited based on their previous experience of HM sharing. Our report adds to the literature by providing additional information on the prevalence of HM sharing among a large, national sample of mothers.

It is likely that some degree of selection bias limits both our qualitative and quantitative studies. We only recruited mothers with experience with HM expression for our qualitative study. Thus, we cannot comment on the opinions about or attitudes toward HM sharing and selling among mothers who never expressed HM. Thus, the opinions and attitudes of formula‐feeding mothers, and those who never expressed HM, are not included in these findings. Additionally, our survey sample was a convenience sample recruited through http://researchmatch.org. This is a limitation because ResearchMatch volunteers are not representative of the US population; for example, Hispanics are underrepresented. Given this limitation of ResearchMatch, and the fact that our final sample was 85% White, our results may not be generalizable to a more ethnically diverse population. The mode of questionnaire administration is one of the primary limitations of this study. Because we administered this questionnaire online to a convenience sample of mothers recruited through http://researchmatch.org, we have no way to ensure our respondents were mothers of infants aged between 19 and 35 months old. Although we have made every attempt to reduce the errors associated with fabricated responses to our questionnaire, we cannot guarantee that the noise in our data created by inclusion of potentially implausible responses has been eliminated. Additionally, given that the primary purpose of this questionnaire was to understand more about infant‐feeding practices in general, we were limited in the number of questions we could ask. Thus, we did not include questions about risk‐minimization strategies employed by mothers who responded to the questionnaire.

6. CONCLUSION

Insights from our qualitative data highlight that mothers feel that freely sharing HM is more common than purchasing or selling HM. Mothers in our qualitative study had reservations about the commodification of HM and the intentions of those who profit from the sale of HM. Among a national sample of mothers, the prevalence of freely providing and receiving HM was considerably higher than purchasing or selling HM. Although the FDA recommends against HM sharing (US Food and Drug Administration, 2010), this practice is occurring nonetheless. Therefore, healthcare professionals should be aware of this and prepared to answer questions from families about HM sharing. Additional research is required regarding the optimal strategies for limiting the risks of HM sharing so that guidelines can be created for families considering participating in HM sharing.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

EJOS designed the research, collected and analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. SRG and KMR designed the research, contributed to data analysis, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the mothers who participated in both the qualitative and quantitative portions of this study. EJOS was funded by a grant from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation.

O'Sullivan EJ, Geraghty SR, Rasmussen KM. Awareness and prevalence of human milk sharing and selling in the United States. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(S6):e12567 10.1111/mcn.12567

REFERENCES

- Bond, A. (2008). Got breast milk? Buying human milk online from strangers or even sharing among friends puts babies at risk of disease. AAP News, 29(9), 24. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, K. (2010). Of care and commodities: Breast milk and the new politics of mobile biosubstances. Progress in Human Geography, 34(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S. K. , Reyes‐Foster, B. , & Rogers, T. L. (2015). Liquid gold or Russian roulette? Risk and human milk sharing in the US news media. Health, Risk & Society, 17(1), 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Eidelman, A. I. (2015). The ultimate social network: Breastmilk sharing via the internet. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(5), 231–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer, L. (2016). A call for FDA Regulation of human milk sharing. Journal of Human Lactation, 32(2), 389–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquerra‐Zwiers, A. , Rossman, B. , Meier, P. , Engstrom, J. , Janes, J. , & Patel, A. (2016). “It's somebody else's milk”: Unraveling the tension in mothers of preterm infants who provide consent for pasteurized donor human milk. Journal of Human Lactation, 32(1), 95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fildes, V. A. (1987). Breasts, bottles and babies: A history of infant feeding Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty, S. R. , McNamara, K. , Kwiek, J. J. , Rogers, L. , Klebanoff, M. A. , Augustine, M. , & Keim, S. A. (2015). Tobacco metabolites and caffeine in human milk purchased via the internet. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(9), 419–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden, J. (1996). A social history of wet nursing in America: From breast to bottle Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gribble, K. D. (2013). Peer‐to‐peer milk donors' and recipients' experiences and perceptions of donor milk banks. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 42(4), 451–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble, K. D. (2014a). “I am happy to be able to help”: Why women donate milk to a peer via Internet‐based milk sharing networks. Breastfeeding Medicine, 9(5), 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble, K. D. (2014b). Perception and management of risk in Internet‐based peer‐to‐peer milk‐sharing. Early Child Development and Care, 184(1), 84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gribble, K. D. , & Hausman, B. L. (2012). Milk sharing and formula feeding: Infant feeding risks in comparative perspective? The Australasian Medical Journal, 5(5), 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. A. , Scott, K. W. , Lebo, L. , Hassan, N. , Lightner, C. , & Pulley, J. (2012). ResearchMatch: A national registry to recruit volunteers for clinical research. Academic Medicine, 87(1), 66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim, S. A. , Hogan, J. S. , McNamara, K. A. , Gudimetla, V. , Dillon, C. E. , Kwiek, J. J. , & Geraghty, S. R. (2013). Microbial contamination of human milk purchased via the Internet. Pediatrics, 132(5), e1227–e1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim, S. A. , Kulkarni, M. M. , McNamara, K. , Geraghty, S. R. , Billock, R. M. , Ronau, R. , … Kwiek, J. J. (2015). Cow's milk contamination of human milk purchased via the Internet. Pediatrics, 135(5), e1157–e1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim, S. A. , McNamara, K. A. , Dillon, C. E. , Strafford, K. , Ronau, R. , McKenzie, L. B. , & Geraghty, S. R. (2014). Breastmilk sharing: Awareness and participation among women in the Moms2Moms study. Breastfeeding Medicine, 9(8), 398–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M. S. , & Kakuma, R. (2012). Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8. CD003517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz, J. Z. , & Kupper, N. S. (1981). Cross‐nursing: Wet‐nursing in a contemporary context. Pediatrics, 67(5), 715–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labiner‐Wolfe, J. , & Fein, S. B. (2013). How US mothers store and handle their expressed breast milk. Journal of Human Lactation, 29(1), 54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, D. (2003). Breast sharing: Cross‐feeding among Australian women. Health Sociology Review, 12(2), 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R. (2012). Breast milk sharing is making a comeback, but should it? The American Journal of Nursing, 112(6), 19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan, E. J. , Geraghty, S. R. , & Rasmussen, K. M. (2016a). Human milk expression as a sole or ancillary strategy for infant feeding: A qualitative study. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan, E. J. , Geraghty, S. R. , & Rasmussen, K. M. (2016b). Informal human milk sharing: A qualitative exploration of the attitudes and experiences of mothers. Journal of Human Lactation, 32(3), 416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan, E. J. , & Rasmussen, K. M. (2017). Development, construct validity, and reliability of the Questionnaire on Infant Feeding: A tool for measuring contemporary infant‐feeding behaviors. The Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmquist, A. E. L. , & Doehler, K. (2016). Human milk sharing practices in the U.S. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12(2), 278–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, M. T. , Goodell, L. S. , Allen, J. C. , & Fogleman, A. (2014). A mixed‐methods observational study of human milk sharing communities on Facebook. Breastfeeding Medicine, 9(3), 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, M. T. , Goodell, L. S. , Fogleman, A. , Pettus, H. , Bodenheimer, A. L. , & Palmquist, A. E. (2016). Expanding the supply of pasteurized donor milk: Understanding why peer‐to‐peer milk sharers in the United States do not donate to milk banks. Journal of Human Lactation, 32(2), 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes‐Foster, B. M. , Carter, S. K. , & Hinojosa, M. S. (2015). Milk sharing in practice: A descriptive analysis of peer breastmilk sharing. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(5), 263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes‐Foster, B. M. , Carter, S. K. , & Hinojosa, M. S. (2017). Human milk handling and storage practices among peer milk‐sharing mothers. Journal of Human Lactation, 33(1), 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, R. (2004). The virtues of cross‐nursing and the ‘yuk’ factor. Australian Feminist Studies, 19(45), 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, R. (2007). Cross‐nursing, ethics, and giving breast milk in the contemporary context. Women's Studies International Forum, 30(5), 439–450. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, S. , Martyn, J. , & Foell, J. (2015). Risks of the unregulated market in human breast milk. The BMJ. h1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steube, A. M. , Gribble, K. D. , & Palmquist, A. E. (2014). Differences between online milk sales and peer‐to‐peer milk sharing. Pediatrics e‐Letter. Retrieved April, 25. (2015) [Google Scholar]

- Thorley, V. (2009). Mothers' experiences of sharig breastfeeding or breastmilk co‐feeding in Australia 1978–2008. Breastfeeding Review, 17(1), 9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorley, V. (2011). Mothers' experiences of sharing breastfeeding or breastmilk, part 2: The early 21st century. Nursing Reports, 2(1). [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration . (2010). Use of Donor Human Milk [Online]. Available: http://www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/PediatricTherapeuticsResearch/ucm235203.htm [Accessed June 1st 2017].

- Wolf, J. H. (1999). “Mercenary Hirelings “or” A Great Blessing”?: Doctors' and mothers' conflicted perceptions of wet nurses and the ramifications for infant feeding in Chicago, 1871–1961. Journal of Social History, 33(1), 97–120. [Google Scholar]