Abstract

The aim of this systematic review and meta‐analysis was to assess the efficacy on an intervention on breastfeeding self‐efficacy and perceived insufficient milk supply outcomes. The literature search was conducted among 6 databases (CINAHL, Medline, PsyncInfo, Scopus, Cochrane, and ProQuest) in between January 2000 to June 2016. Two reviewers independently assessed the articles for the following inclusion criteria: experimental or quasi‐experimental studies; healthy pregnant women participants intending to breastfeed or healthy breastfeeding women who gave birth to a term singleton and healthy baby; intervention administered could have been educational, support, psycho‐social, or breastfeeding self‐efficacy based, offered in prenatal or postnatal or both, in person, over the phone, or with the support of e‐technologies; breastfeeding self‐efficacy or perceived insufficient milk supply as outcomes. Seventeen studies were included in this review; 12 were randomized controlled trials. Most interventions were self‐efficacy based provided on 1‐to‐1 format. Meta‐analysis of RCTs revealed that interventions significantly improved breastfeeding self‐efficacy during the first 4 to 6 weeks (SMD = 0.40, 95% CI 0.11–0.69, p = 0.006). This further impact exclusive breastfeeding duration. Only 1 study reported data on perceived insufficient milk supply. Women who have made the choice to breastfeed should be offered breastfeeding self‐efficacy‐based interventions during the perinatal period. Although significant effect of the interventions in improving maternal breastfeeding self‐efficacy was revealed by this review, there is still a paucity of evidence on the mode, format, and intensity of interventions. Research on the modalities of breastfeeding self‐efficacy should be pursued.

Keywords: breastfeeding duration, breastfeeding self‐efficacy, exclusive breastfeeding, perceived insufficient milk supply, systematic review

Key messages.

Breastfeeding self‐efficacy is a key modifiable factor that could be enhanced.

Strong breastfeeding self‐efficacy decreases maternal perception of insufficient milk supply.

Strong breastfeeding self‐efficacy increases the duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

Women with confidence in their breastfeeding capacity are more likely to breastfeed exclusively for a longer period, thereby taking advantages of the numerous benefits associated with the practice of breastfeeding for both mother and child.

1. INTRODUCTION

Substantial evidence confirms maternal and child health benefits associated with breastfeeding (Victora et al., 2016). Breastmilk protects against diarrhoea, respiratory infections, otitis media among children (Victora et al., 2016), mortality associated with necrotizing enterocolitis, and sudden infant death syndrome (Victora et al., 2016). Furthermore, breastfeeding enhances child cognition (Rollins et al., 2016). Protective effects of breastfeeding practices on breast and ovarian cancer have also been documented in breastfeeding mothers (Bartick et al., 2017; Victora et al., 2016).

Despite these benefits, only 37% of mothers follow current international recommendation of 6 months exclusive breastfeeding (Victora et al., 2016) or achieve their intended breastfeeding duration (Flaherman, Beiler, Cabana, & Paul, 2016; Wagner, Chantry, Dewey, & Nommsen‐Rivers, 2013). Still, suboptimal breastfeeding in United States has been associated with an excess of premature maternal and child deaths and increased healthcare costs (Bartick et al., 2017).

The first 4 to 6 weeks after birth have been identified as a critical period for cessation of breastfeeding or its exclusivity, maternal milk supply concern being frequently reported for stopping breastfeeding earlier than intended (Balogun, Dagvadorj, Anigo, Ota, & Sasak, 2015; Flaherman et al., 2016; Gatti, 2008; Hauck, Fenwick, Dhaliwal, & Butt, 2011). It has been estimated that between 25% and 35% of mothers ceased breastfeeding because of milk supply concern (Gatti, 2008; Gionet, 2013). Maternal breastfeeding self‐efficacy has been identified as a key factor in maternal perception of insufficient milk supply and breastfeeding duration (Galipeau, Dumas, & Lepage, 2017; Gatti, 2008; Rollins et al., 2016). Breastfeeding self‐efficacy has been defined as maternal confidence in her ability to breastfeed (Dennis, 1999). Mother with strong breastfeeding self‐efficacy perceived less that their milk is insufficient to satisfy their infant, and breastfeed exclusively for a longer duration (Galipeau et al., 2017; Gatti, 2008; Otsuka, Dennis, Tatsuoka, & Jimba, 2008). It is therefore important to determine which intervention might be effective in helping women to be confident in their ability to breastfeed.

A recent systematic review reported increased breastfeeding duration and exclusivity after support intervention for healthy mothers and term babies but did not have breastfeeding self‐efficacy as secondary outcome (McFadden et al., 2017). Another recent systematic review reported significant effect of an intervention on breastfeeding self‐efficacy and duration but did not examine the effect on maternal perception of insufficient milk (Brockway, Benzies, & Hayden, 2017; Chan, 2014). Therefore, the aim of this review was to examine the effectiveness of an intervention either educational, support, or breastfeeding self‐efficacy‐based types on breastfeeding self‐efficacy and perceived insufficient milk in adult mothers during perinatal period, and when recorded on breastfeeding duration and exclusivity.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This review was done following guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009).

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in this review if they met all the following criteria.

Types of studies

Studies had to be published or unpublished experimental and quasi‐experimental studies in English or French.

Type of participants

Participants had to be healthy pregnant women, either primiparous or multiparous, who gave birth to a term singleton and healthy baby, and, intending to breastfeed or breastfeeding mothers of at term singleton and healthy baby.

Types of interventions

The interventions included were supplemental to the usual maternity care provided in the setting. The interventions were, according to their main intent, educational, support, or breastfeeding self‐efficacy‐based types, or a combination of all the above, offered to women/mothers in prenatal or postnatal or both, either by a professional or lay person. The intervention could have been administered once or at multiple time points, in person, over the phone, or with the support of e‐technologies. Educational‐type intervention included solely structured, organized, or goal‐oriented breastfeeding programme combining information and practical skills (Chan, 2014). Support intervention could have included a combination of elements such as reassurance, praise, information, or staff training (Renfrew, McCormick, Wade, Quinn, & Dowswell, 2012). Breastfeeding self‐efficacy‐based intervention included education and/or support and was developed according to breastfeeding self‐efficacy theory. This type of intervention is directed towards the four sources of influence of breastfeeding self‐efficacy such as performance accomplishments, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological reactions (Chan, Ip, & Choi, 2016; Dennis, 1999).

Types of outcomes measures

Data on the efficacy of an intervention on breastfeeding self‐efficacy or perceived insufficient milk supply primary outcomes should have been recorded in the first 4‐ to 6‐week postnatal. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy outcome could have been measured with the Breastfeeding Self‐efficacy short form (Dennis, 2003), a 14 statements, self‐report tool, with a 5‐point Likert scale, or with the 33 items version of Breastfeeding Self‐efficacy tool (Dennis & Faux, 1999). It could have also been measured with other self‐reported scale specifically designed for the study. Data on the modalities of the intervention such as types, timing, format, and mode of delivered were also recorded for subgroup analysis. Perceived insufficient milk supply could have been measured by the Perception of Insufficient Milk Questionnaire (McCarter‐Spaulding & Kearney, 2001), which measures maternal perception of infant satisfaction with five items using a 5‐point Likert scale. It could have also been measured with other self‐reported scale specifically designed for the study. When reported, breastfeeding duration and exclusivity were also outcomes of interest. Breastfeeding duration and exclusivity definitions should have been provided and recorded in the 4‐ to 6‐week postnatal or up to 6 months.

2.2. Information sources

Six electronic databases were searched, namely, CINAHL, Medline, PsyncInfo, Scopus, Cochrane, and ProQuest, from January 1, 2000, since breastfeeding self‐efficacy theory was developed around that time (Dennis, 1999) to June 30, 2016. Hand searches were conducted of the bibliographies of the manuscripts considered eligible for the study as well as of relevant background articles.

2.3. Search strategy

Literature searches were conducted by the main author (RG) after consultation with a librarian (SB) and verified by the second author (AB). The search strategy was developed using the following keywords and MeSH terms: “breast feeding,” “infant feeding,” “lactation,” education,” “support,” “intervention,” “promotion,” “program development,” “breastfeeding self‐efficacy,” and “insufficient milk supply.” Following, an example of a search strategy in EBSCO CINAHL and Medline which yielded 137 studies ([MH “Breast Feeding”) OR (MH “Infant Feeding”) OR (MH “Lactation”]) AND ([MH “education”) OR (MH “Self‐Efficacy”) OR (MH “Support, Psychosocial”) OR (MH “Promotion”]) AND ([TX “Intervention”) OR (MH “Program Development”]) AND ([TX “breastfeeding self efficacy”) OR (TX “insufficient milk supply”) OR (MH “breast feeding”]); Limits: peer reviewed; publication date: 2000‐01‐01 to 2016‐06‐30. The full search strategy is shown in Appendix S1.

2.4. Study selection

The resulted literature search was transferred to Endnote X7, where duplicates were removed. All article titles and abstracts, and then the full text of the remaining articles, were reviewed independently by the main author (RG), and research assistants, respectively (LC and CD). Disagreements were resolved by the second author (AB).

2.5. Data extraction and management

Data collection form was developed and piloted test for data extraction including characteristics of the population (e.g., age, parity, and mode of delivery); study design; characteristics of the intervention (e.g., type, format, mode, and timing); outcomes (e.g., breastfeeding self‐efficacy and perceived insufficient milk); and relevant outcomes (breastfeeding exclusivity and duration), tools used, and results (e.g., means, frequencies). For eligible studies, data were extracted by the third author (AT) and verified by the main author (RG). In case of discrepancies, the second author (AB) was consulted. When study results were unclear or missing data, the authors of the article were contacted once to provide further details.

2.6. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (RG and AT) independently assessed risk of bias for each included study, according to Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins & Green, 2011). The third author (AB) resolved any disagreement. Studies were assessed for risk bias as either high risk, low risk, or unclear risk considering sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data reporting, selective reporting bias, and any other sources of bias (Higgins & Green, 2011). We assessed the risk for attrition bias related to dropouts, withdrawals as followed: low risk, cut‐off rate of less than 25% of attrition rates (Renfrew et al., 2012); high risk, more than 25% of attrition rates; and unclear risk, insufficient reporting allowing to make a judgement about attrition rates (Higgins & Green, 2011). Complete details of the assessment of risk of bias are provided in Appendix S2.

2.7. Data analyses

Outcomes results of studies assessed as high risk of selection bias (quasi‐experimental studies) or attrition bias (≥25% attrition rate) or selective data reporting (no outcome result available after authors contacted) were not included in the meta‐analysis. Extracted data were entered in RevMan software (Review Manager, Computer programme for Mac Version 5.3, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, 2014). Continuous data (breastfeeding self‐efficacy outcome) were analysed using the inverse variance method and random effects model, because heterogeneity was expected in terms of interventions or populations studied. The mean difference with their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) was used when the measure of breastfeeding self‐efficacy was consistent across studies, and the standardized mean difference (SMD) with their corresponding 95% CI was used when the breastfeeding self‐efficacy outcome in the included studies was measured with different measurement scales as previously described. Subgroups analyses were also done on the modalities of the intervention such as type, timing, format, and mode of delivery using the SMD with their corresponding 95% CI. The test of overall effect was assessed using z statistics at p < .05. The I 2 statistics were used to quantify heterogeneity. When moderate or high heterogeneity was detected, I 2 greater than 50% (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, 2003), this was mentioned in the text as a limitation. Dichotomous data (breastfeeding duration and breastfeeding exclusivity) were analysed using Mantel–Haenszel method, and relative risks (RR) with 95% CI were calculated. Forest plots were produced.

3. RESULTS

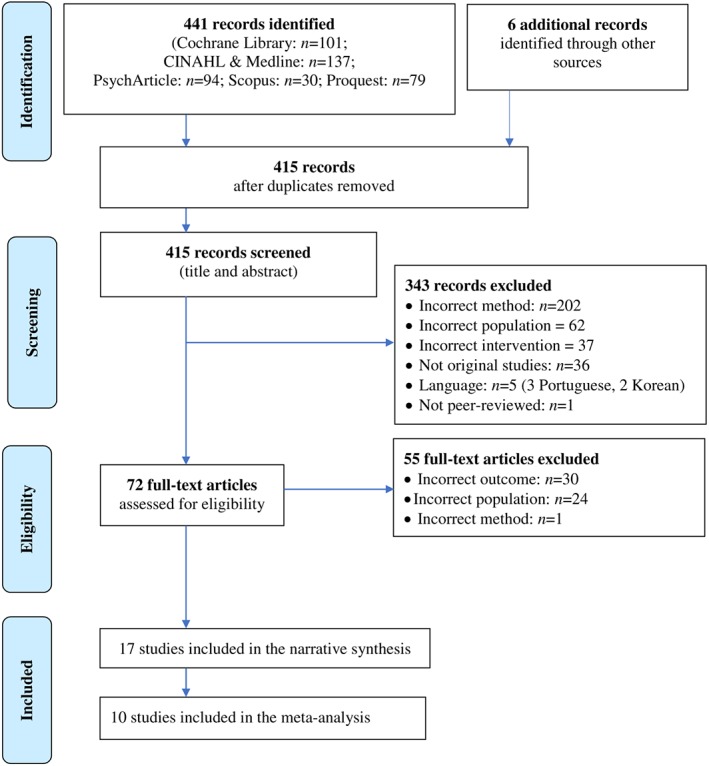

3.1. Study selection

The study selection process is described in Figure 1, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses flow diagram. In total, 447 records were identified through databases and reference lists. After removal of duplicates with EndNote X7, 415 records (titles and abstracts) were screened for inclusion criteria. Of these, 72 were found eligible for full‐text review. A further 55 records were excluded because of the absence of breastfeeding self‐efficacy outcome, or not meeting eligibility criteria for type of studies or participants as previously described. At the final stage, 17 studies were included in the narrative synthesis, and 10 were used in the meta‐analysis.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses flow chart of selection procedure

3.2. Studies characteristics

Study and participant characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of included studies

| Authors (year) | Country/setting | Primiparous (%) | Experimental group baseline n | Control group baseline n | Experimental group mean age (SD) | Control group mean age (SD) | BF outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized control trials | |||||||

| Bunik et al. (2010) | United States/ mother‐baby unit/ Hispanic population is more than 95% Mexican American | 100 | 161 | 180 | NR (NR) | NR (NR) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Chan et al. (2016) | China/ hospital with the highest birth rate among Hong Kong public hospitals | 100 | 35 | 36 | 32.6 (3.5) | 31.4 (4.2) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Edwards et al. (2013) | United States /in the process of obtaining the BFH certification | 100 | 7 | 8 | NR (NR) | NR (NR) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF) |

| Joshi et al. (2016) | United States | NA | 23 | 23 | NR (NR) | NR (NR) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF) |

| Kronborg et al. (2012) | Denmark / hospital had adopted most of the standards of the BFH initiative | NA | 603 | 590 | 28.9 (3.7) | 29.2 (3.7) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Kronborg et al. (2007) | Denmark/ 2/5 BFH certified, 5/5 had adopted the standards of the BFH initiative | 36 | 780 | 815 | NR (NR) | NR (NR) | BF self‐efficacy, perception of insufficient milk, BF rates |

| McQueen et al. (2011) | Canada | 100 | 69 | 81 | NR (NR) | NR (NR) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Nichols et al. (2009) | Australia | 53 | 45 | 45 | 29.0 (5.3) |

29.4 (5.9) |

BF self‐efficacy (BSES), BF rates |

| Noel‐Weiss et al. (2006) | Canada | 100 | 47 | 45 | NR (NR) | NR (NR) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Olenick (2006) | United States/ in private practices | 43 | 86 | 96 | 27.1 (5.1) | 25.8 (4.8) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Wilhelm et al. (2006) | United States | 100 | 37 | 36 | NR (NR) | NR (NR) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Wu et al. (2014) | China | 100 | 37 | 37 | 28.4 (2.8) | 27.8 (3.0) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Quasi‐experimental studies | |||||||

| Awano and Shimada (2010) | Japan/ 1/2 BFH certified/ lactation consultant accessible for all mothers during hospitalization | 100 | 55 | 62 | 30.3 (0.6) | 28.9 (0.4) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Coffey (2014) | United States/ hospital where it is policy for all breastfed infants to being BF within the first 1 to 2 hours after delivery | 100 | 10 | 10 | 29.9 (NR) 27,8 | 25.7 (NR) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

| Hatamleh (2012) | United States/ low‐income white women | 53 | 19 | 17 | 25.0 (NR) | 22.3 (NR) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES), BF rates |

| Hauck et al. (2007) | Australia/ participants were recruited within a highly motivated cohort of BF mothers | NA | 193 | 195 | 32.3 (NR) | 31.7 (NR) | BF self‐efficacy (BSES), BF rates |

| Otsuka et al. (2014) | Japan/ 2/4 BFH certified | 39 | 161 in BFH, 204 in non BFH | 158 in BFH, 312 in non BFH | 31.1 (4.2) in BFH, 30.5 (5.0) in non BFH | 30.1 (4.9) in BFH, 31.1 (4.6) in non BFH | BF self‐efficacy (BSES‐SF), BF rates |

Note. BF = breastfeeding; BFH = baby friendly hospital; BSES = breastfeeding self‐efficacy scale; BSES‐SF = Breastfeeding Self‐Efficacy Scale Short Form; NR = not reported.

This systematic review included 17 studies, 15 (88%) in published articles in a peer reviewed journal (Awano & Shimada, 2010; Bunik et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Edwards, Bickmore, Jenkins, Foley, & Manjourides, 2013; Hatamleh, 2012; Hauck, Hall, & Jones, 2007; Joshi, Amadi, Meza, Aguire, & Wilhelm, 2016; Kronborg, Maimburg, & Væth, 2012; Kronborg, Vaeth, Olsen, Iversen, & Harder, 2007; McQueen, Dennis, Stremler, & Norman, 2011; Nichols, Schutte, Brown, Dennis, & Price, 2009; Noel‐Weiss, Rupp, Cragg, Bassett, & Woodend, 2006; Otsuka et al., 2014; Wilhelm, Stepans, Hertzog, Rodehorst, & Gardner, 2006; Wu, Hu, McCoy, & Efird, 2014) and two (12%) in unpublished theses (Coffey, 2014; Olenick, 2006) between 2006 and 2016. Almost half of them (47%) were recent studies (≥2012). Of all the selected articles, 12 (70%) were randomized control trials (Bunik et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Wilhelm et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2014) and five (30%) were quasi‐experimental studies (Awano & Shimada, 2010; Coffey, 2014; Hatamleh, 2012; Hauck et al., 2007; Otsuka et al., 2014). The 5,408 participants were recruited across six countries, and seven (40%) studies were conducted in the United States.

3.3. Sample characteristics

The mean sample size was 309.7 participants, ranging from 15 to 1,595 participants per study. Participants were, for most of the studies (n = 9; 53%), first‐time mothers (Awano & Shimada, 2010; Bunik et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Coffey, 2014; Edwards et al., 2013; McQueen et al., 2011; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Wilhelm et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2014). The mean age of the women was 28.8 ± 3.7 years old. Although most of the studies were done in high‐income countries, three studies done in the USA were conducted among low‐economic Hispanic (Bunik et al., 2010; Joshi et al., 2016) and low‐economic White women (Hatamleh, 2012).

3.4. Tools used to assess relevant outcomes

All the studies included measured breastfeeding self‐efficacy (100%), 15 measured breastfeeding rates (88%), and only one measured the perception of insufficient milk production (6%). Breastfeeding self‐efficacy outcome was measured with the Breastfeeding Self‐efficacy short form (Dennis, 2003), a 14 statements, self‐report tool, with a 5‐point Likert scale in 13 studies (76.5%; Awano & Shimada, 2010; Bunik et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Coffey, 2014; Edwards et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Otsuka et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2014). The 33 items version of Breastfeeding Self‐efficacy tool (Dennis & Faux, 1999) was used in three studies (17.5%; Hatamleh, 2012; Hauck et al., 2007; Wilhelm et al., 2006), and one study (6%) used a tool designed for the study, a self‐report eight items with 4‐point Likert scale of agreement (Kronborg et al., 2007). All the studies measured breastfeeding self‐efficacy during the first 4 to 6 postnatal weeks.

The perceived insufficient milk supply outcome was measured with one item, 5‐point Likert scale degree of confidence in reading baby's cues.

Relevant breastfeeding outcomes reported in 15 of the included studies (88%) were breastfeeding duration and exclusivity. Two studies measured any breastfeeding up to 6 months (13%; Bunik et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2006), and five studies (33%) measured exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months (Bunik et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Hauck et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2007; Olenick, 2006; Otsuka et al., 2014). Three studies (20%) measured any breastfeeding up to 4 to 6 weeks (Bunik et al., 2010; Coffey, 2014; Hatamleh, 2012), and nine studies (60%) measured exclusive breastfeeding up to 4 to 6 weeks (Awano & Shimada, 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Otsuka et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2014).

3.5. Types and modalities of interventions

All types of intervention in this review are presented in Table 2. Almost 60% of the interventions (n = 10) were self‐efficacy based (Awano & Shimada, 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Hatamleh, 2012; Hauck et al., 2007; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Otsuka et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2014); 24% (n = 4) were educational type (Coffey, 2014; Edwards et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2012); and 18% (n = 3) were support (Bunik et al., 2010; Kronborg et al., 2007; Wilhelm et al., 2006). Timing of the interventions was varied. Six studies (35%) reported interventions during prenatal period (Coffey, 2014; Kronborg et al., 2012; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Otsuka et al., 2014), four interventions (24%) included a prenatal and postnatal components (Chan et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2013; Hatamleh, 2012; Hauck et al., 2007), and seven studies (41%) reported administration of the intervention during the postnatal period (Awano & Shimada, 2010; Bunik et al., 2010; Joshi et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2007; McQueen et al., 2011; Wilhelm et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2014). The formats of the intervention also varied. Four studies (24%) were in groups such as workshop (Coffey, 2014; Kronborg et al., 2012; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006); 11 (65%) were at the individual level such as individualized informational session, workbook, or computer (Awano & Shimada, 2010; Bunik et al., 2010; Edwards et al., 2013; Hauck et al., 2007; Joshi et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2007; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Otsuka et al., 2014; Wilhelm et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2014); and, finally, two studies (11%) provided a combination of individual and group format (Chan et al., 2016; Hatamleh, 2012). Modes of delivery were face to face in seven of the studies (41%; Awano & Shimada, 2010; Coffey, 2014; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Wilhelm et al., 2006), by telephone in one study (5%; Bunik et al., 2010), in combination in four studies (24%; Chan et al., 2016; Hatamleh, 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2014) and in five studies (30%), there were no contact, as the intervention was provided through the use of a workbook or computer (Edwards et al., 2013; Hauck et al., 2007; Joshi et al., 2016; Nichols et al., 2009; Otsuka et al., 2014). As described in Table 2, length and frequency of the intervention varied and were reported in 12 studies (70%; Awano & Shimada, 2010; Bunik et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Coffey, 2014; Hatamleh, 2012; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Wilhelm et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2014). The studies that used workbook or computer format did not report the number of times the intervention was used by the participants (Edwards et al., 2013; Hauck et al., 2007; Joshi et al., 2016; Nichols et al., 2009; Otsuka et al., 2014).

Table 2.

Description of the interventions in included studies

| Authors (year) | Type of intervention | Primary aim | Format | Frequency, duration, and timing of provision | Content description of interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized control trials | |||||

| Bunik et al. (2010) | Support | To evaluate the effectiveness of a telephone‐based BF support and education intervention on duration and exclusivity of BF in low‐income, primarily Latina women. | Telephone counselling | Daily for 2 weeks postpartum. | Advantages of colostrum and importance of a good latch, engorgement, concerns about unnecessary formula supplementation, supply and demand, assessing milk supply, causes of infant crying, modesty, family support, violation of la cuerentena (i.e., 40‐day postpartum), support groups, mother's illness, baby blues versus postpartum depression, medications and diet, pumping and milk storage, return to work or school or time away from baby, growth spurts, and cluster feeding. |

| Chan et al. (2016) | Self‐efficacy based (education and support via telephone counselling) | To investigate the effectiveness of a self‐efficacy‐based BF educational programme in increasing BF self‐efficacy, BF duration and exclusive BF rates among Hong Kong mothers. | Workshop, telephone counselling | One 2.5‐hr prenatal workshop and one 30 to 60‐min follow‐up call 2‐week postpartum. | Group discussion, sharing of experience, evaluation of emotional/physiological condition and breastfeeding status. |

| Edwards et al. (2013) | Education and support | To develop and evaluate a first‐generation tablet laptop‐based computer agent designed to improve exclusive BF rates in mothers interested in BF. | Informational material on a tablet/laptop | Participants had access to the tablet or laptop based information from the third trimester until hospital discharge after birth. | Benefits of BF |

| Joshi et al. (2016) | Education and support | To explore the effect of a bilingual, interactive touch screen computer based BF educational programme on improving BF knowledge, BF self‐efficacy and predicting BF attrition among pregnant Hispanic rural women living in Scottsbluff, Nebraska. | Informational material on a tablet | Seven 30‐min postpartum interactive sessions on a tablet between hospital discharge and 6 months postpartum. | Baseline assessment was done on a tablet kiosk and participants received interactive tailored BF education |

| Kronborg et al. (2012) | Education | To assess the effect of an antenatal training programme on knowledge, self‐efficacy and problems related to BF, and the BF duration. | Workshop, informational material on paper, movie | Three hour prenatal sessions. | Instrumental guide (doll) in infant care and BF practice, delivery process, pain relief, coping strategies, infant care and BF, parental role, relationship between the woman and her partner. |

| Kronborg et al. (2007) | Psychosocial health education and support | To assess the impact of a supportive intervention on the duration of BF. | Individualized session at home, informational material on paper | One to three home visits in the first 5‐week postpartum. | Effective BF technique, learning to know the baby, self‐regulated BF, interpretation of baby cues, sufficient milk and interaction with the baby. |

| McQueen et al. (2011) | Self‐efficacy based (support) | To pilot test a newly developed BF self‐efficacy intervention. | Individualized sessions | Two postpartum sessions (within 24 hr of delivery and within 24 hr of the first session) and one follow‐up by phone 1‐week postpartum. | Assessment, strategies to increase breastfeeding self‐efficacy, and evaluation. |

| Nichols et al. (2009) | Self‐efficacy based | To examine the effect of a self‐efficacy‐based educational intervention on BF duration and exclusivity. | Workbook | Participants kept the workbook for a maximum of 2 weeks and they returned it before the birth of their baby. | Enhancing BF self‐efficacy |

| Noel‐Weiss et al. (2006) | Self‐efficacy based and education | To determine the effects of a prenatal BF workshop on maternal BF self‐efficacy and duration. | Workshop |

One 2.5‐hr prenatal workshop. |

Performance accomplishment, vicarious learning, social/verbal persuasion, and emotional/physiological arousal. |

| Olenick (2006) | Self‐efficacy based and education | To determine whether group prenatal education improves BF outcomes. | Class | One 2‐hour prenatal class. | Group exercises and take‐home handouts for later reference. |

| Wilhelm et al. (2006) | Motivational interview (support) | To explore the feasibility of using motivational interviewing to promote sustained BF by increasing a mother's intent to breastfeed for 6 months and increasing her BF self‐efficacy. | Individualized session | Three postpartum sessions (2‐ to 4‐day, 2‐week, and 6‐week postpartum). | The four principles used in motivational interviewing: express empathy and reflecting what the client is saying, create discrepancy, roll with resistance to hear the reasons for ambivalence and support self‐efficacy by emphasizing the client's abilities and resource availability. |

| Wu et al. (2014) | Self‐efficacy based | To evaluate the effects of a BF intervention on primiparous mothers' BF self‐efficacy, BF duration and exclusivity at 4‐ and 8‐week postpartum. | Individualized session | Two postpartum sessions (1‐ and 2‐day postpartum) and a follow‐up phone call 1 week after hospital discharge. | Assessment, self‐efficacy‐enhancing strategies and evaluation |

| Quasi‐experimental studies | |||||

| Awano and Shimada (2010) | Education and support | To develop a self‐care programme for BF aimed at increasing mothers' BF confidence and to evaluate its effectiveness. | Informational material on paper, movie | One intervention 4‐ to 5‐day postpartum, before discharge. | Recommendations and supporting evidence, advantages and basics of BF, baby's feeding cue, positioning, latch‐on, positive signs of baby's feeding and self‐check list for BF. |

| Coffey (2014) | Education | To examine the level of self‐efficacy for new mothers attending a formal BF education compared to those that did not. | Class | One 2‐hr prenatal class. | NR |

| Hatamleh (2012) | Breastfeeding self‐efficacy based (education and support) | To test the efficacy of the Breastfeeding Self‐Efficacy Intervention Program to increase BF duration. | Class, movie, telephone counselling | One 2‐hr prenatal class where an informational video was shown and phone calls follow‐up until 6‐week postpartum | Normal physiological postpartum changes, evaluation of milk supply and infant cues. |

| Hauck et al. (2007) | Breastfeeding self‐efficacy based (education and self‐management) | To assess the effects of a BF journal on BF prevalence, and perceptions of conflicting advice, self‐management and BF self‐efficacy from birth to 12‐week postpartum. | Workbook (BF journal) | Participants had access to the BF journal before and after the birth of their infant. | Evidence‐based and standardized information, development of plans to deal with conflicting advice, identify solutions to problems and develop breastfeeding goals. |

| Otsuka et al. (2014) | Self‐efficacy based | To evaluate the effect of a self‐efficacy intervention on BF self‐efficacy and exclusive BF in two types of hospitals: a baby friendly certified hospital and a regular hospital. | Workbook | Participants received a workbook in their third trimester and were encouraged to complete it before deliver (completion time: About 30 minutes). | Exploring aspects of confidence (providing an explanation of the workbook), mastery (performance accomplishment), building confidence by learning from others (vicarious experiences), using encouragement (verbal persuasion), exploring how we respond to stress (physical responses) and keeping motivated (concluding the workbook). |

Note. BF = breastfeeding; NR = not reported.

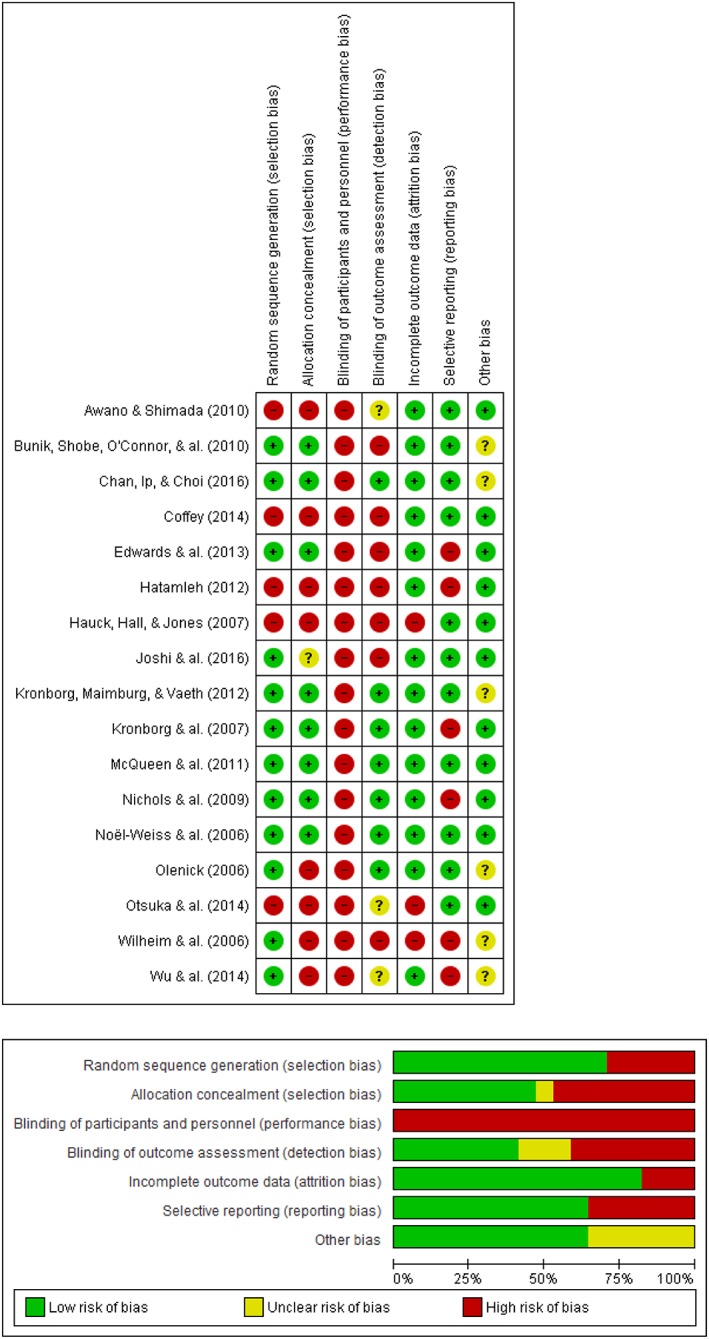

3.6. Risks of bias in included studies

The risks of bias in included studies are presented in Figure 2. Twelve out of 17 studies (70%) presented low risk of selection bias by using random sequence generation (Bunik et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Wilhelm et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2014), and eight of them (47%), by using allocation concealment (Bunik et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2013; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006). None of the studies was blinded to participants and personnel, which is not unusual considering the type of intervention (Renfrew et al., 2012). For the risk of detection bias, seven of the studies (41%) had blinding of outcome assessment (Chan et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006), and three of them (18%) had an unclear risk of bias (Awano & Shimada, 2010; Otsuka et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2014). Concerning the risk of attrition and reporting bias, three of the studies (18%) had incomplete outcome data (Hauck et al., 2007; Otsuka et al., 2014; Wilhelm et al., 2006), and six (35%) selective reporting (Edwards et al., 2013; Hatamleh, 2012; Kronborg et al., 2007; Nichols et al., 2009; Wilhelm et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2014).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary and graph of included studies

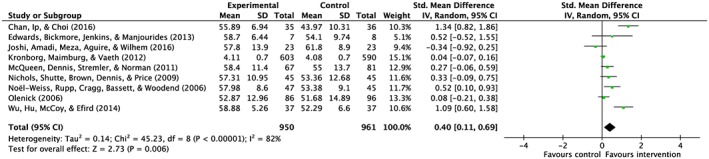

3.7. Effectiveness of intervention on maternal breastfeeding self‐efficacy: Meta‐analysis

Nine studies assessed the effectiveness of intervention on breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4 to 6 weeks as an outcome among 1,911 women (n experimental = 950; n control = 961; Chan et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Wu et al., 2014). Interventions had a significant effect on breastfeeding self‐efficacy (SMD = 0.40; 95% CI [0.11–0.69]; p = .006) as shown in Figure 3 compared with the control intervention with usual maternity care. Heterogeneity was high (I 2 = 82%). Heterogeneity could be qualified, respectively, as low when I 2 value is 25%, moderate at 50%, and high at 75% (Higgins et al., 2003).

Figure 3.

Breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4–6 weeks

3.8. Subgroup analysis

3.8.1. Types of interventions

Six studies among 657 women (n experimental = 317; n control = 340) assessed the effectiveness on breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4 to 6 weeks when the intervention was breastfeeding self‐efficacy based (Chan et al., 2016; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Wu et al., 2014), and three studies among 1,254 women (n experimental = 633; n control = 621) when the intervention was educational type (Edwards et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2012), and none of the included studies was of support type. As shown in Appendix S3, the interventions were significant only when they were self‐efficacy‐based type (SMD = 0.57; 95% CI [0.20–0.93]; Z = 3.06; p = .002).

3.8.2. Timing of the interventions

Four studies among 1,557 women (n experimental = 781; n control = 776) assessed the effectiveness on breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4 to 6 weeks when the intervention was provided during the prenatal period (Kronborg et al., 2012; Nichols et al., 2009; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006); two studies among 86 women (n experimental = 42; n control = 44) when the intervention provided during both prenatal and postnatal period (Chan et al., 2016; Edwards et al., 2013); and three studies among 268 women (n experimental = 127; n control = 141) when provided during postnatal period only (Joshi et al., 2016; McQueen et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2014). The effect of the intervention was significant only when the intervention was provided during both prenatal and postnatal (SMD = 1.06; 95% CI [0.29–1.82]; Z = 2.70; p = .007; Appendix S4).

3.8.3. Format of interventions

Three studies among 1,467 women (n experimental = 736; n control = 731) assessed the effect when the intervention was provided in a group format (Kronborg et al., 2012; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006); five studies among 373 women (n experimental = 179; n control = 194) used an individual format (Edwards et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2016; McQueen et al., 2011; Nichols et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2014), and only one study among 71 women (n experimental = 35; n control = 36) used combined format (individual and group; Chan et al., 2016). Only the combined format was found to be effective (SMD = 1.34; 95% CI [0.82–1.86]; Z = 5.07; p < .00001; Appendix S5).

3.8.4. Mode of interventions

Three studies among 1,477 women (n experimental = 736; n control = 731) used face‐to‐face mode of intervention (Kronborg et al., 2012; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006); three studies among 293 women (n experimental = 139; n control = 154) used a combined mode that included face‐to‐face and telephone contacts (Chan et al., 2016; McQueen et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2014), and three studies among 151 women (n experimental = 75; n control = 76) provided the intervention using a computer or workbook/journal that meant no contact (Edwards et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2016; Nichols et al., 2009). The only one significant effect found was when the intervention used a combined mode of intervention (face to face and telephone; SMD = 0.88; 95% CI [0.18–1.58]; Z = 2.46, p < .0005; Appendix S6).

3.9. Efficacy of intervention on perceived insufficient milk supply

Only one study assessed the effect of an intervention (support by health professionals during postnatal period) on perception of insufficient milk supply among 1,597 breastfeeding mothers (n experimental = 75; n control = 76; Kronborg et al., 2007). Mothers in the intervention group were less likely to perceive insufficient milk supply and were more confident in not knowing the exact amount of milk their baby had received as measured on a 5‐point Likert scale (median, 3.3), compared with the comparison group (median: 2.9; rank‐sum test, p < .001).

3.10. Efficacy of interventions on related breastfeeding outcomes: Meta‐analysis

3.10.1. Findings for breastfeeding duration

Seven studies assessed the effect of the intervention on breastfeeding cessation under 6 months among 3,355 women (Chan et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006; Wu et al., 2014). As shown in Appendix S7, interventions had a significant effect on breastfeeding cessation under 6 months (RR = 0.82; 95% CI [0.72–0.93] Z = 3.01; p < .003). Interventions among 1,662 women (Chan et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Olenick, 2006; Wu et al., 2014) had no significant effect on breastfeeding cessation up to 4 to 6 weeks (RR = 0.85; 95% CI [0.67–1.08]; Z = 1.30; p < .20; Appendix S8).

3.10.2. Findings for breastfeeding exclusivity

Six studies among 3,267 women (Chan et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Noel‐Weiss et al., 2006; Olenick, 2006) assessed the effect of the interventions on exclusive breastfeeding cessation under 6 months. As shown in Appendix S9, interventions had a significant effect on exclusive breastfeeding cessation under 6 months (RR = 0.97; 95% CI [0.95–0.99]; Z = 2.52; p < .01). The five studies done among 3,183 women (Chan et al., 2016; Kronborg et al., 2007; Kronborg et al., 2012; McQueen et al., 2011; Olenick, 2006) revealed a significant effect of the interventions on exclusive breastfeeding cessation up to 4 to 6 weeks (RR = 0.80; 95% CI [0.71–0.90]; Z = 3.63; p < .003; Appendix S10).

4. DISCUSSION

This review examined the efficacy of an intervention either educational, support, or psychosocial on breastfeeding self‐efficacy and perceived insufficient milk in adult mothers during perinatal period and their related breastfeeding outcomes of duration and exclusivity.

The review included 17 studies published between 2006 and 2016, 10 of which contributed to the meta‐analysis of mixed methodological quality. These studies totalling 5,408 women were recruited across six countries, Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Japan, and United States, mainly high income. The interventions were diverse in type, format, and timing of administration. The meta‐analysis revealed that interventions significantly improved breastfeeding self‐efficacy with a small effect size (0.4) during the first 4 to 6 weeks. This result parallels recent systematic review and meta‐analysis that reported positive effect on breastfeeding self‐efficacy outcome (Brockway et al., 2017). Breastfeeding self‐efficacy‐based type of intervention were significantly more effective compared with educational type, which focused solely on education such as workshop or class. However, this result is in contrast with same previous systematic review and meta‐analysis, which reported educational‐type intervention efficacy over support type (Brockway et al., 2017). But it should be interpreted with caution, because both RCT's and quasi‐experimental studies, therefore studies of lower quality, were included in the systematic and meta‐analysis mentioned (Brockway et al., 2017). The breastfeeding self‐efficacy‐based interventions administered in the included studies of this review combined educational and support types, which might explain the high heterogeneity revealed by the subgroup analysis. The interventions were theory based, directed to inform the four sources of influence of breastfeeding self‐efficacy, which are the performance of the behaviour itself (breastfeeding); the vicarious experience (seeing others breastfeed); verbal persuasion (encouragement and praise from important women's referents); and finally, the physiological reactions that could impact the practice of breastfeeding (pain, anxiety, etc.; Bandura, 2007; Dennis, 1999). This might explain the key active ingredients of the efficacy of the intervention.

Interventions that were administered during both prenatal and postnatal period were significantly more effective in improving breastfeeding self‐efficacy compared with interventions administered only in prenatal or postnatal. However, the evidence is low in this regard, because it reflects the results of two studies among 86 participants. Similarly, interventions were more effective when combined format were used such as individual (phone contact) and group (workshop), but again, it should be used with caution because it reflects the results of only one study among 71 participants.

Although the effect size found in this meta‐analysis is small (0.4), it appears to be sufficient in included studies, providing a booster to maintain breastfeeding exclusivity in early postnatal weeks and up to 6 months. Indeed, the meta‐analysis results showed that the interventions were more effective on breastfeeding duration and exclusivity up to 6 months, and breastfeeding exclusivity up to 4 to 6 weeks. This corroborates other studies that report on the importance of breastfeeding confidence for persistence of breastfeeding and its exclusivity (Dennis, 1999, 2003, 2006; Kingston, Dennis, & Sword, 2007; Rollins et al., 2016; Semenic, Loiselle, & Gottlieb, 2008). Surprisingly, the meta‐analysis revealed no significant effect on any breastfeeding cessation up to 4 to 6 weeks. It is possible that the improvement in maternal breastfeeding self‐efficacy was not enough to overcome milk supply concerns in early weeks, which may have led to breastfeeding cessation. Maternal response to insufficient milk concern might be supplementation which may in turns impact breastmilk supply and leads to breastfeeding cessation (Flaherman et al., 2016; Kent, Prime, & Garbin, 2012). In fact, maternal perception of insufficient milk is a well‐known leading cause of breastfeeding cessation (Gatti, 2008; Rollins et al., 2016). It is noteworthy that only one study did address outcome of maternal perception of insufficient milk supply, which reported positive impact on both sufficient milk perception and exclusive breastfeeding duration (Kronborg et al., 2007).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

The principal strength of this systematic review is the rigorous process followed such as the screening of numerous data bases, the multiple reviewers involved in data extraction, and assessment of methodological quality of the studies. One of the limitation is that only studies published in English or French were considered. Another limitation is that both primiparous and multiparous participants were considered, which may present different breastfeeding self‐efficacy levels and breastfeeding needs and support. High heterogeneity despite subgroups analyses might be explained by diversity in the intensity, format, mode, and timing of the interventions provided. Breastfeeding‐related outcomes reflect the results of the studies that used breastfeeding self‐efficacy as primary outcome and, therefore, might not be reflective of interventions designed to increase breastfeeding duration and exclusivity. Publication bias is another limitation because studies without significant results might not have been published. Finally, most of the participants were from high‐income country, which may preclude application of the results towards less advantaged population.

4.2. Implications for future research

Although significant effect of the interventions in improving maternal breastfeeding self‐efficacy was revealed by this review, there is still a paucity of evidence on the mode, format, and intensity of interventions. Research on the modalities of breastfeeding self‐efficacy should be pursued. Intervention designed to improve maternal breastfeeding self‐efficacy should also document their effect on maternal perception of insufficient milk supply. Although most of the studies reported that milk supply concerns are a leading cause of breastfeeding, only one study reported the effect of interventions on this important outcome. Development and validation of interventions regarding maternal perception of milk supply should be pursued. Also, validation of breastfeeding self‐efficacy interventions should be pursued among a diversity of population either from high‐ or low‐income countries.

4.3. Clinical implications

Women who have made the choice to breastfeed should be offered breastfeeding self‐efficacy‐based interventions during the perinatal continuum combining varied format and mode. Mothers with stronger confidence in their breastfeeding capacity are more likely to breastfeed exclusively for a longer period, thereby taking advantages of the numerous benefits associated with the practice of breastfeeding for both mother and child.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

RG designed the systematic review protocol. She conducted the literature searches, articles selection, and analysis; interpreted the results; and drafted the article. AB collaborated to the design of the systematic review protocol and reviewed the literature searches. She acted as a consultant when discrepancies were present in data extraction between reviewers. She collaborated in the interpretation of the results and in drafting the article. AT did data extraction and collaborated in the drafting of the article. LL participated in the interpretation of the results and reviewed the final version of the paper.

Supporting information

Supplementary Appendix S1. Search strategy

Supplementary Appendix S2. Description of the assessment of risk of bias.

Supplementary Appendix S3. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4–6 weeks – Types of interventions

Supplementary Appendix S4. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4‐6 weeks – Timing of Intervention

Supplementary Appendix S5. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4–6 weeks – Format of intervention

Supplementary Appendix S6. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4–6 weeks – Mode of intervention

Supplementary Appendix S7. Breastfeeding cessation under six months

Supplementary Appendix S8. Breastfeeding cessation up to four to six weeks

Supplementary Appendix S9. Exclusive breastfeeding cessation under six months

Supplementary Appendix S10. Exclusive breastfeeding cessation up to four to six weeks

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Louiselle Carignan, nursing student at the Université du Québec en Outaouais, and Catherine Dubé, accounting student at Université de Montréal, for their participation in articles selection.

Galipeau R, Baillot A, Trottier A, Lemire L. Effectiveness of interventions on breastfeeding self‐efficacy and perceived insufficient milk supply: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14:e12607 10.1111/mcn.12607

REFERENCES

- Awano, M. , & Shimada, K. (2010). Development and evaluation of a self care program on breastfeeding in Japan: A quasi‐experimental study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 5, 9–18. 10.1186/1746-4358-5-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogun, O. O. , Dagvadorj, A. , Anigo, K. M. , Ota, E. , & Sasak, S. (2015). Factors influencing breastfeeding exclusivity during the first 6 months of life in developing countries: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 11, 433–451. 10.1111/mcn.12180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2007). Auto‐efficacité: Le sentiment d'efficacité personnelle (2nd ed.). Bruxelles: De Boeck Universite. [Google Scholar]

- Bartick, M. C. , Schwarz, E. B. , Green, B. D. , Jegier, B. J. , Reinhold, A. G. , Colaizy, T. T. , … Stuebe, A. M. (2017). Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: Maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13, e12366 10.1111/mcn.12366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockway, M. , Benzies, K. , & Hayden, K. A. (2017). Interventions to improve breastfeeding self‐efficacy and resultant breastfeeding rates: A systematic review and meta‐Analysis. Journal of Human Lactation, 33(3), 486–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunik, M. , Shobe, P. , O'Connor, M. E. , Beaty, B. , Langendoerfer, S. , Crane, L. , & Kempe, A. (2010). Are 2 weeks of daily breastfeeding support insufficient to overcome the influences of formula? Academic Pediatrics, 1, 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M. Y. (2014). The effectiveness of breastfeeding education on maternal breastfeeding self‐efficacy and breastfeeding duration. Hong Kong, China: Thesis. Nursing. University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M. Y. , Ip, W. Y. , & Choi, K. C. (2016). The effect of a self‐efficacy‐based educational programme on maternal breast feeding self‐efficacy, breast feeding duration and exclusive breast feeding rates: A longitudinal study. Midwifery, 36, 92–98. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, R. (2014). Breastfeeding education: Improving initiation and duration of breastfeeding. (1571757 M.S.N.), Gardner‐Webb University, Ann Arbor. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.‐L. (1999). Theoretical underpinnings of breastfeeding confidence: A self‐efficacy framework. Journal of Human Lactation, 15, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.‐L. (2003). The breastfeeding self‐efficacy scale : Psychometric assessment of the short form. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecology and Neonatal Nursing, 32(6), 734–744. 10.1177/0884217503258459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.‐L. (2006). Identifying predictors of breastfeeding self‐efficacy scale in the immediate postpartum period. Research in Nursing & Health, 29, 256–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.‐L. , & Faux, S. (1999). Development and psychometric testing of the breastfeeding self‐efficacy scale. Research in Nursing and Health, 22(5), 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R. A. , Bickmore, T. , Jenkins, L. , Foley, M. , & Manjourides, J. (2013). Use of an interactive computer agent to support breastfeeding. Maternal & Child Health Journal, 17(10), 1961‐1968 1968 p. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1222-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherman, V. J. , Beiler, J. S. , Cabana, M. D. , & Paul, I. M. (2016). Relationship of newborn weight loss to milk supply concern and anxiety: The impact on breastfeeding duration. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12(3), 463–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galipeau, R. , Dumas, L. , & Lepage, M. (2017). Perception of not having enough milk and actual milk production of first time breastfeeding mothers: Is there a difference? Breastfeeding Medicine, 12(4), 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, L. (2008). Maternal perceptions of insufficient milk supply in breastfeeding. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 40(4), 355–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gionet, L. (2013). Breastfeeding trends in Canada. Health at a glance. [Google Scholar]

- Hatamleh, W. (2012). Prenatal breastfeeding intervention program to increase breastfeeding duration among low income women. Health, 4(3), 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, Y. , Fenwick, J. , Dhaliwal, S. , & Butt, J. A. (2011). Western Australian survey of breastfeeding initiation, prevalenace and early cessation patterns. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(2), 260–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, Y. , Hall, W. A. , & Jones, C. (2007). Prevalence, self‐efficacy and perceptions of conflicting advice and self‐management: effects of a breastfeeding journal. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 57(3), 306–317. 312p. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04136.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. T. , & Green, S . (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Retrieved from http://handbook.cochrane.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. T. , Thompson, S. G. , Deeks, J. J. , & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring Inconsistency In Meta‐Analyses. British Medical Journa, 327(7414), 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A. , Amadi, C. , Meza, J. , Aguire, T. , & Wilhelm, S. (2016). Evaluation of a computer‐based bilingual breastfeeding educational program on breastfeeding knowledge, self‐efficacy and intent to breastfeed among rural Hispanic women. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 91, 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent, J. C. , Prime, D. K. , & Garbin, C. P. (2012). Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production. Journal of Obstetrical, gynecological and Neonatal Nursing, 41(1), 114–121. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, D. , Dennis, C.‐L. , & Sword, W. (2007). Exploring breast‐feeding self‐efficacy. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing, 21, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronborg, H. , Maimburg, R. D. , & Væth, M. (2012). Antenatal training to improve breast feeding: A randomised trial. Midwifery, 28(6), 784–790. 10.1016/j.midw.2011.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronborg, H. , Vaeth, M. , Olsen, J. , Iversen, L. , & Harder, I. (2007). Effect of early postnatal breastfeeding support: a cluster‐randomized community based trial. Acta Paediatrica, 7, 1064–1070. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarter‐Spaulding, D. E. , & Kearney, M. H. (2001). Parenting self‐efficacy and perception of insufficient milk supply. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, 30(5), 515–522. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01571.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, A. , Gavine, A. , Renfrew, M. J. , Wade, A. , Buchanan, P. , Taylor, J. L. , … . 10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub5, D. (2017). Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. (2). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McQueen, K. A. , Dennis, C. , Stremler, R. , & Norman, C. D. (2011). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a breastfeeding self‐efficacy intervention with primiparous mothers. JOGNN: Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 40(1), 35‐46 12p. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7). e1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, J. , Schutte, N. S. , Brown, R. F. , Dennis, C. , & Price, I. (2009). The impact of a self‐efficacy intervention on short‐term breast‐feeding outcomes. Health Education & Behaviour, 36(2), 250‐258 259 p. doi: 10.1177/1090198107303362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel‐Weiss, J. , Rupp, A. , Cragg, B. , Bassett, V. , & Woodend, A. K. (2006). Randomized controlled trial to determine effects of prenatal breastfeeding workshop on maternal breastfeeding self‐efficacy and breastfeeding duration. JOGNN: Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 35(5), 616‐624 619p. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olenick, P. L. (2006). The effect of structured group prenatal education on breastfeeding confidence, duration and exclusivity to twelve weeks postpartum. (3242239 Ph.D.), Touro University International, Ann Arbor. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, K. , Dennis, C.‐L. , Tatsuoka, H. , & Jimba, M. (2008). The relationship between breastfeeding self‐efficacy and perceived insufficient milk supply. Journal of Obstetrical, Gynecological and Neonatal Nursing, 37(5), 546–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, K. , Taguri, M. , Dennis, C.‐L. , Wakutani, K. , Awano, M. , Yamaguchi, T. , & Jimba, M. (2014). Effectiveness of a Breastfeeding Self-efficacy Intervention. Do Hospital Practices Make a Difference? Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(1), 296–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, M. J. , McCormick, F. M. , Wade, A. , Quinn, B. , & Dowswell, T. (2012). Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5. Retrieved from doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, N. C. , Bhandari, N. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Horton, S. , Lutter, C. K. , Martines, J. C. , … Victora, C. G. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet, 387, 491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenic, S. , Loiselle, C. , & Gottlieb, L. (2008). Predictors of the duration of exclusive breastfeeding among first‐time mothers. Research in Nursing & Health, 31, 428–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. D. , França, G. V. A. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding int the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387, 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, E. A. , Chantry, C. J. , Dewey, K. G. , & Nommsen‐Rivers, L. A. (2013). Breastfeeding concerns at 3 and 7 days postpartum and feeding status at 2 months. Pediatrics, 132(4), e865–e875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, S. L. , Stepans, M. B. F. , Hertzog, M. , Rodehorst, T. K. C. , & Gardner, P. (2006). Motivational Interviewing to Promote Sustained Breastfeeding. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing: Clinical Scholarship for the Care of Women, Childbearing Families, & Newborns, 35(3), 340–348. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D. S. , Hu, J. , McCoy, T. P. , & Efird, J. T. (2014). The effects of a breastfeeding self‐efficacy intervention on short‐term breastfeeding outcomes among primiparous mothers in Wuhan, China. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(8), 1867‐1879 1813p. doi: 10.1111/jan.12349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Appendix S1. Search strategy

Supplementary Appendix S2. Description of the assessment of risk of bias.

Supplementary Appendix S3. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4–6 weeks – Types of interventions

Supplementary Appendix S4. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4‐6 weeks – Timing of Intervention

Supplementary Appendix S5. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4–6 weeks – Format of intervention

Supplementary Appendix S6. Breastfeeding self‐efficacy up to 4–6 weeks – Mode of intervention

Supplementary Appendix S7. Breastfeeding cessation under six months

Supplementary Appendix S8. Breastfeeding cessation up to four to six weeks

Supplementary Appendix S9. Exclusive breastfeeding cessation under six months

Supplementary Appendix S10. Exclusive breastfeeding cessation up to four to six weeks