Abstract

In the United States, a significant proportion of human milk (HM) is now fed to infants from bottles. This mode of infant feeding is rarely measured or described in research studies or monitored by national surveillance systems. Consequently, little is known about expressed‐HM feeding as an infant feeding strategy. Our objective was to understand how mothers use HM expression and expressed‐HM feeding as a sole strategy or in combination with at‐the‐breast feeding to feed HM to their infants. We conducted semi‐structured interviews with 41 mothers with experience of HM expression and infants under three years of age. Data were analysed using a grounded theory approach for sub‐themes related to the pre‐selected major themes of maternal HM production and infant HM consumption. Within the major theme of maternal HM production, sub‐themes related to maternal over‐production of HM. Many mothers produced more HM than their infant was consuming and stored it in the freezer. This enabled some infants to consume HM weeks or months after it was expressed. Within the major theme of infant HM consumption, the most salient sub‐theme related to HM‐feeding strategies. Four basic HM‐feeding strategies emerged, ranging from predominant at‐the‐breast feeding to exclusive expressed‐HM feeding. The HM‐feeding strategies and trajectories highlighted by this study are complex, and most mothers fed HM both at‐the‐breast and from a bottle—information that is not collected by the current national breastfeeding survey questions. To understand health outcomes associated with expressed‐HM feeding, new terminology may be needed.

Keywords: breastfeeding, breast milk, human milk, infant feeding, infant feeding decisions, qualitative methods

Introduction

Human milk (HM) feeding rates have been rising consistently over the last decade (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014) as women endeavour to meet recommendations to exclusively breastfeed for six months, followed by the introduction of appropriate complementary foods and continuation of breastfeeding for one year or more (Kramer & Kakuma 2012; Eidelman et al. 2012). These recommendations are based on a large body of evidence associating sub‐optimal breastfeeding behaviour with poorer infant outcomes (Ip et al. 2007; Sankar et al. 2015; Chowdhury et al. 2015). However, formative studies providing evidence for these recommendations typically compared children who were fed HM directly at the breast with those who were fed a HM substitute from a bottle (Ip et al. 2007; Kramer et al. 2008). In the contemporary United States, these may no longer be the most appropriate infant feeding comparison categories.

Based on data from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II), a longitudinal US survey conducted between 2005 and 2007, most HM‐fed infants are no longer fed solely at the breast. The majority (85%) of HM‐feeding mothers in the IFPS II expressed HM when their infant was between 1.5 and 4.5 months old (Labiner‐Wolfe et al. 2008); this expressed HM was then offered to their child from a bottle. Six percent of HM‐feeding mothers in the IFPS II only fed HM from a bottle and never from the breast (Shealy et al. 2008). Although we have insufficient data to tell whether prevalence of HM expression and feeding has been increasing in the United States over time, in Australia (Binns et al. 2006) and Singapore (Hornbeak et al. 2010), countries where data from infants born in different years are available, prevalence of HM expression has increased. Given that reimbursement for breast pumps is now mandated by the Affordable Care Act, which was signed into law in 2010 in the United States (HealthCare.gov 2015), prevalence of HM expression is, at least, unlikely to decrease.

Despite this shift in HM‐feeding modes, the National Immunization Survey (NIS) questions (Table 1) that are used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to report prevalence of HM‐feeding are only about infant HM consumption, regardless of feeding mode. The NIS collects retrospective feeding data from the primary caregivers of a representative sample of children aged 19 – 35 months annually; it is the primary source of national breastfeeding prevalence data used by the CDC. This means that we do not collect information specifically about dyadic at‐the‐breast feeding. In spite of that, responses to these questions are routinely used to report prevalence of maternal‐infant breastfeeding behaviours (McGuire 2011).

Table 1.

National immunization survey HM‐feeding related questions

| Number | Question text | Indicator reported by CDC |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Was [child] ever breastfed or fed breast milk? | Breastfeeding initiation |

| 2 | How old was [child's name] when [child's name] completely stopped breastfeeding or being fed breast milk? | Breastfeeding duration |

| 3 | How old was [child's name] when (he/she) was first fed formula? | Breastfeeding exclusivity |

| 4 | This next question is about the first thing that [child] was given other than breast milk or formula. Please include juice, cow's milk, sugar water, baby food or anything else that [child] may have been given, even water. How old was [child's name] when (he/she) was first fed anything other than breast milk or formula? | Breastfeeding exclusivity |

HM expression and expressed‐HM feeding are of public health importance because, depending on the location and duration of storage, expressed HM loses important nutritional (Chang et al. 2012; Romeu‐Nadal et al. 2008) and functional (Hanna et al. 2004; Silvestre et al. 2006) components. Short‐term storage of HM reduces the concentration of vitamin C (Garza et al. 1982), with increased duration of storage in the freezer causing a more marked decrease. Storing HM in household freezers can result in the hydrolysis of triglycerides and the appearance of free fatty acids in the milk (Bitman et al. 1983), and the lysis of the cellular components of the milk (Lawrence 1999; Silvestre et al. 2006). In addition, expressed‐HM feeding as a behaviour may affect the duration of any HM feeding. This association has been only minimally studied and results to date have been inconsistent; some authors (Meehan et al. 2008) reported a positive association between use of a breast pump and duration of any HM feeding, while others (Schwartz et al. 2002) reported the opposite.

In‐depth studies specifically focusing on HM expression have not reported data about longitudinal HM‐feeding trajectories (Morse & Bottorff 1988; Clemons & Amir 2010; Flaherman et al. 2013). Of the studies published to date reporting longitudinal trajectories of HM feeding, most report only at‐the‐breast feeding (Butte et al. 1985; Kent et al. 2006; Sievers et al. 2002; Casiday et al. 2004). In one study, a retrospective survey, in which information on both maternal HM production and infant HM consumption were elicited, the authors (Geraghty et al. 2013) reported that these behaviours were not always synchronous within a dyad, that patterns of HM production and consumption were highly variable, and that infant HM consumption was an inappropriate proxy for maternal HM production.

We conducted this research with the a priori objective of exploring our belief that the word breastfeeding alone may be insufficient to fully describe HM‐feeding in the United States for the purposes of research or surveillance. We explored behaviors related to maternal HM production and infant HM consumption separately, as they are no longer a synchronous dyadic behaviour. This research goes beyond what has previously been published by exploring patterns of HM expression and HM feeding qualitatively. The objective of this paper is to identify routine behaviours related to maternal HM‐production and infant HM‐consumption, about which minimal data are collected in research studies or by national surveillance systems.

Key messages.

Many mothers in this study expressed more HM than their child was consuming at a given time and built up a stockpile of HM in the freezer. As a result, several infants were fed HM many weeks or months after it was expressed.

At any given time, all mother‐infant dyads in this sample could be categorized into one of four basic HM‐feeding strategies involving a combination of at‐the‐breastfeeding, and refrigerated or frozen expressed HM‐feeding to provide their infants with HM.

Maternal HM expression led to infant HM consumption behaviours that are currently not considered or captured by most research studies or national surveillance systems.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

We recruited 41 mothers from four counties in upstate New York who had experience with HM feeding and breast pump use or hand expression and whose child was between one and three years old. This age range was chosen to sample mothers similar in demographic characteristics to those sampled by the NIS, namely mothers of children aged 19 – 35 months. Mothers were recruited between August 2012 and June 2014 through notices in paediatric offices, cafés, stores that sold infant products, emails to parenting listservs and by snowball sampling. Notices indicated that we were interested in talking to mothers about HM expression, and we asked mothers who had ever expressed or pumped breast milk to contact the research team. Mothers then emailed or phoned the first author, and a brief screening questionnaire was conducted and an interview was arranged. The screening questionnaire was to ensure the mother was ≥18 years, had every pumped or expressed HM and had an infant ≤3 years of age. The cut‐off for infant age was chosen for two reasons: to mimic the NIS sample, and because recall of breastfeeding practices is reliable when recalled after a short period (Li et al. 2005). As we neared the end of recruitment, we stopped recruiting mothers >30 years and only interviewed those ≤30 years of age as this demographic was more difficult to recruit. Mothers were selected purposively for heterogeneity on characteristics associated with HM‐feeding: age, socioeconomic status, marital status, employment status and parity (Thulier & Mercer 2009), as this was likely to provide a sample that were heterogeneous for practices related to HM expression. We did not have a specific distribution of ideal sample demographic characteristics defined a priori; however, our intention was to recruit at least two to three mothers from each demographic group of interest (e.g. primiparous/multiparous, employed/unemployed, ≤ 30/> 30) to ensure the opinions of a range of mothers were represented.

Data collection

At the time data were collected, the first author was a doctoral student in her late twenties with no children and no personal experience of HM‐feeding—something that often came up during interviews. She was a registered dietitian with a strong interest in maternal and infant nutrition, particularly improving support for breastfeeding mothers. Using an interview guide, the first author conducted one qualitative, semi‐structured, in‐depth interview with each mother after she provided signed informed consent. Participants were informed that the interviewer was a graduate student in the Field of Nutrition who wanted to learn more about at‐the‐breast feeding and expressed‐HM feeding. Interviews occurred at a location of the mother's choice, usually her home or a local café. Interviews lasted an average of 58 min (range 26 – 121 min) and we provided a $10 gift card as compensation. The interview explored at‐the‐breast feeding, HM expression and expressed‐HM feeding behaviours. Mothers were probed for additional information but interviews were largely participant‐led, meaning that mothers were allowed spend more time talking about topics that were important to them. Demographic information was collected by questionnaire at the end of the interview. Interviews were audio‐recorded, transcribed verbatim and all were verified for accuracy by listening to the recording and checking that the transcript was accurate. Data collection continued until data saturation was reached—the point at which no new information was obtained (Saumure & Given 2008). This research was approved by Cornell University's Institutional Review Board.

Data analysis

To begin, we analysed the data with two predetermined codes in mind that reflected our a priori research objective of exploring HM production and HM consumption as distinct behaviours. We coded the transcripts using our two predetermined codes (maternal HM production and infant HM consumption), and these codes are shown in this analysis as major themes. We then used a grounded theory approach (Bryant & Charmaz 2007), to iteratively analyse the transcripts using emergent codes; these emergent codes are shown as sub‐themes in this analysis. Three researchers were involved in data analysis; the first author coded all transcripts, and two research assistants coded half the transcripts such that each interview was coded by two analysts. During the data analysis process, we created and iteratively updated a code book. We used ATLAS.ti software (version 7) to manage data analysis, and data analysis was discussed in weekly debriefing meetings. During these weekly meetings, any discrepancies in coding between the two analysts were discussed until a consensus was reached. All names in the text are pseudonyms.

Results

A total of 41 mothers participated in this research; participants were aged 21–42 years, and 10 were ≤30 years old. Most (85%) were married, 78% had at least a college degree and 56% were multiparous. We did not collect information on race or ethnicity on our demographic questionnaires; however, the majority of participants were white. A small number of mothers (n = 3) described their experiences of providing HM to premature infants, but most infants were born at term. As required by the study inclusion criteria, all mothers had experience with HM expression, either by hand or with a breast pump and all had fed HM to their infants. Among our sample, duration of at‐the‐breast feeding ranged from zero days to 3.5 years; a small number of mothers put their infant to the breast a limited number of times and over half of mothers fed at the breast for 12 months or more. Duration of maternal HM expression ranged from a few days to 17 months and duration of expressed‐HM feeding ranged from a few days to 16 months. Our two major a priori themes were (i) maternal HM production, and (ii) infant HM consumption. Within each of these major themes, three sub‐themes related to HM expression and expressed‐HM feeding behaviours that deviate from the conventional use of the term ‘breastfeeding’ emerged from the data. An additional major theme emerged from these data during the iterative data analysis process: (iii) how mothers describe breastfeeding and expressed HM‐feeding.

Theme 1: Maternal HM production

Many mothers expressed more HM than their child was consuming at a given time, and this over‐production allowed them to build up a stockpile of HM in the freezer that was stored for long periods of time. Mothers put a lot of thought into how best to use this stored HM; some voiced concerns about feeding ‘old’ HM that had been stored for a while to their infants. Finally, maternal over‐production of HM also allowed some mothers to continue HM feeding after they stopped lactating. These three sub‐themes are described in detail below.

Maternal over‐production of HM

HM expression, and use of breast pumps specifically, enabled many mothers to extract more milk from their breasts than their infant was consuming at a given time. Several mothers began expressing HM early in their child's life purposefully to build up a stockpile of HM to be fed to their infant when they returned to work or for some other period of maternal‐infant separation. A few mothers expressed HM even though their infant refused to drink from a bottle, which created a stockpile of HM. The volumes of HM stored by mothers varied considerably, from a few ounces to thousands of ounces.

‘…there was slowly a stockpile building up and the stockpile really happened at 12 months, we went on vacation for a month. And um, she didn't have a bottle the whole time, and then when we came back, she refused to take a bottle ever again. But I still physically had to pump.’ ( Olive)

‘I just pumped like hell to store it and I have [at work] a giant walk‐in freezer. And so I went like crazy. And it was just like box after box after box. I would fill a diaper box and then my husband would bring it in…’ ( Colette)

Maternal practices and concerns around using stored HM

Most mothers who built up a stockpile of HM in their freezer typically placed very high value on the milk, often calling it ‘liquid gold,’ and they voiced strong desires not to waste any. Some mothers placed such high value on their stored HM as a product that they saved it in the freezer for a period of time after they had finished producing HM to offer it to their child at a time when they perceived it to be especially important, for example, when their child was sick:

‘I did save eh the milk for more than six months, 'cause … we would go to play dates and he'd get in contact with kids that was in daycare so he was getting a lot of colds and it's like “oh I wanna give him my breast milk to help” 'cause I thought like, you know, having more immune assistance will help him.’ (Wendy, stopped producing HM at four months)

In two extreme examples, mothers fed infant formula or introduced solid foods into the infant's diet earlier than desired because they felt like they were using up their stockpile of frozen HM too quickly and they wanted the HM to last longer:

‘That was also why we started him on solids a little earlier than we wanted. We started him on solids at about four months because we were trying to curb how much [stored breast] milk he was drinking’ (Fiona, continued producing and feeding HM until 12 months)

‘I didn't want to use up all my stored breast milk so maybe I would give her one bottle of formula so we could keep [the HM] for later…’ (Tanya, produced HM until eight months and continued feeding HM for ten months)

As a result of maternal stockpiling, several infants were fed HM many weeks or months after it was expressed. Some mothers voiced concerns about whether or not stored HM was appropriate for their infant given that the composition of HM changes over time:

‘Um, I don't know if it's a real great concern but I was, you know, developmentally just wondering if what I pumped for him when he was two months old, developmentally would that be the best option for him when he was ten months old.’ ( Krista)

‘…the later ones have more fat or have more something. Something … more related to what age he is, is what he needs … So there was a time when I was worried about that so, then I, I started taking the more current [bag of HM].’ ( Diana)

Difference between duration of maternal HM production and infant HM consumption

For a small number of mothers, their stockpiling behaviour allowed them to feed HM from the freezer for weeks or months after they had stopped lactating. Other mothers discussed friends doing this; it was generally considered a good idea:

‘I kept her on breast milk until about 8 months, I stopped pumping at 6 but I had almost 2 months uh worth. And that was great, was to walk into the freezer and go “that's awesome, that was me!”’ ( Colette)

‘…I have a friend who pumped lots of extra milk and still fed for a couple of months after she stopped breastfeeding, she still gave her bottles of her milk. But I only know of one person like that did that, it's a good idea.’ ( Orla)

Theme 2: Infant HM consumption

The second theme comprises sub‐themes related to HM‐feeding strategies employed by mothers to feed HM to their infants, infants ‘breastfeeding’ without their mother present and infants consuming another mother's HM.

HM‐feeding strategies

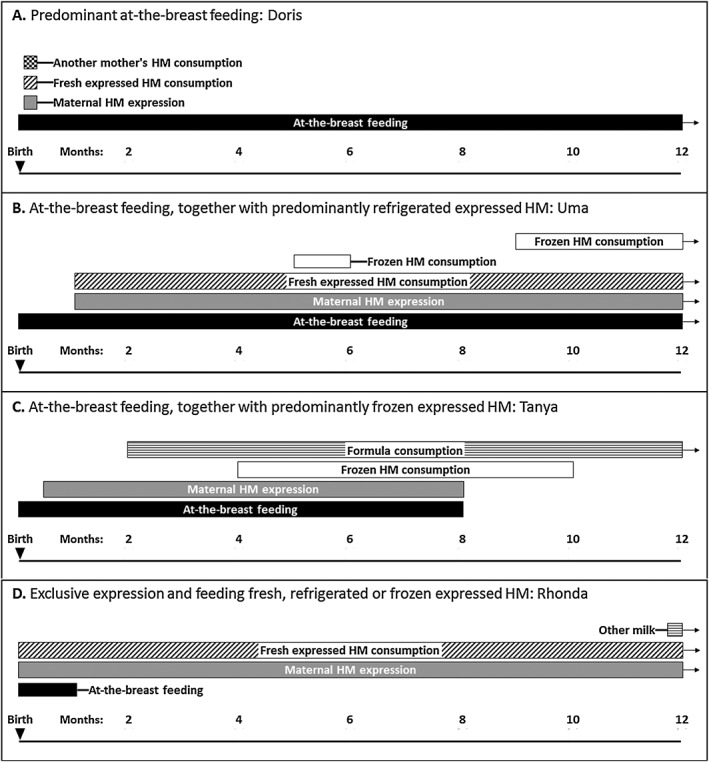

Each mother in this sample described a unique longitudinal infant feeding trajectory over the first year of her infant's life (Fig. 1). However, at any given time point along their trajectory, all mother–infant dyads in this sample could be categorized into one of four types of basic HM‐feeding strategies involving a combination of at‐the‐breast feeding, and refrigerated or frozen expressed‐HM feeding to provide their infants with HM. Infant feeding trajectories were complex as mothers moved in and out of the different HM‐feeding strategies over time depending on their circumstances. The four basic HM‐feeding strategies employed are described here in order of increasing reliance on HM expression and expressed‐HM feeding and, thus, deviation from at‐the‐breast feeding. A brief description of a representative mother is offered for each strategy. These mothers were specifically chosen because together they participated in all behaviours described across all sub‐themes presented in this paper.

Figure 1.

Examples of the four main human milk (HM)‐feeding strategies over the first 12 months of life of four mother–infant dyads. For clarity, only milk‐based feeds are included in these diagrams; infant consumption of solid foods is not pictured. Arrows indicate that some behaviours continued beyond 12 months.

Strategy 1, Predominant at‐the‐breast feeding: A few mothers only expressed HM occasionally and were able to predominantly feed directly at the breast. This infant feeding strategy was typical of mothers who did not return to full‐time employment outside the home. Mothers in this category used breast pumps to help their milk ‘come in’ early postpartum, to provide milk for their infant during a short‐short term separation or to relieve engorgement.

‘I pumped a little bit here and there but it was um, it was basically on demand.’ ( Xena)

A few mothers who predominantly fed at the breast intended to provide expressed HM for their infants either so the baby's father could feed or so the mother could return to work. However, their infants refused to take a bottle so they continued with at‐the‐breast feeding.

‘She never liked [bottles] so um, I think a couple of times my mom took her and my mom said she cried before she even took it because she just didn't want it. And um, then I realized I could never leave her.’ ( Irene)

For example: Doris (Fig. 1; Trajectory A) expressed HM because she experienced a delay in her milk coming in. Her infant was fed a small amount of Doris' expressed HM and another mother's HM for a week. Doris asked her midwife and lactation consultant if they knew any milk donors in their local area and they connected her with another mother who had milk in her freezer ready to donate to a milk bank; this mother then gave her milk to Doris instead. Once Doris' milk came in, she resumed at‐the‐breast feeding.

Strategy 2, At‐the‐breast feeding, together with predominantly refrigerated expressed HM: Some mothers expressed HM regularly and stored it in the refrigerator so that it could be fed the next day by a non‐maternal caregiver, typically a paid daycare provider or the infant's father. This strategy was common among working mothers who had access to a breast pump and had somewhere to pump in the workplace.

‘I just would put the milk in my fridge [at work] and bring it home at night, dump it into the bottles that [my husband] was gonna use the next day and wash out the pump bottles and pack everything up again and bring it back [to work].’ ( Adele)

Refrigerated milk was typically only stored for a day or two and most mothers labelled the bottles so that the oldest milk would be fed to the child first:

‘…most of the daily milk would come from the milk that I had pumped the previous day at work and we had a system of labelling and kind of order within the um, the refrigerator so that [husband] would know to use the oldest milk first.’ ( Uma)

For example: Uma (Fig. 1; Trajectory B) expressed HM to build up a stockpile of frozen HM and to feed HM while she was at work. Her infant was fed some freshly expressed HM before Uma went back to work to get used to bottle‐feeding. Her infant was fed a lot of frozen HM when Uma first returned to work and then the infant settled into a routine of consuming HM that had been expressed the previous day. Later in infancy, freshly expressed HM was topped‐up with HM from the freezer.

Strategy 3, At‐the‐breast feeding, together with predominantly frozen expressed HM: Similar to strategy 2, this strategy was often employed by working mothers. However, mothers who used frozen HM either worked to build up a large stockpile of frozen HM before returning to work or they regularly produced too much HM to store in the refrigerator for a short amount of time, resulting in a stockpile building up in the freezer. Mothers employing this strategy also typically labelled their milk with the date it was expressed and often had complicated strategies for storing milk in their freezer(s) and rotating it so that they used the oldest milk first. In some cases, mothers were expressing milk freshly each day, putting the fresh milk in the freezer and feeding their infant milk from the freezer that had been stored for months:

‘I freeze it in five‐ounce quantities and I typically use the oldest milk that I've pumped … so everyday I'm freezing and then pulling out the older milk so that it can thaw and use so that it doesn't get too old. So it's like a constant full time job washing all the parts and setting up the pump’ ( Pilar)

For example: Tanya (Fig. 1; Trajectory C) expressed HM to build up a stockpile of frozen HM and to feed HM while she was at work. Tanya was not confident in her ability to exclusively provide HM so she introduced infant formula at two months. She had HM stored in the freezer, and her infant went to daycare with half HM and half infant formula. After stopping at‐the‐breast feeding, Tanya still had HM in the freezer and her child was fed half HM and half infant formula for another two months until her child transitioned to consuming only infant formula.

Strategy 4, Exclusive expression and feeding fresh, refrigerated or frozen expressed HM: The reliance on HM expression associated with this strategy was typically incompatible with full‐time employment. Mothers in this study who used this strategy primarily employed it because their infant was not well and could not suckle at the breast or their infant refused the breast after several months of successful at‐the‐breast feeding:

‘…at 8 months he started biting me. …So, I actually had to switch and I couldn't breastfeed anymore and I had to really express all of his milk … I was pumping four or five times a day to meet his needs and it was exhausting. So at ten months, I think I stopped pumping at least one of those four times a day and started giving formula 'cause I just couldn't [continue pumping so much].’ ( Bridget)

However, there were a small number of mothers who said that they preferred being in control of their own schedule and felt that exclusive expression and expressed‐HM feeding allowed them to manage their time better:

‘What I liked was that I was in control of the schedule. …I liked that I had direct control of when I can do it.’ ( Violet)

For example: Rhonda (Fig. 1; Trajectory D) expressed HM because of a medical problem with at‐the‐breast feeding. Her infant consumed HM that had been expressed the previous day. Rhonda was expressing extra HM and storing it in her freezer hoping she could stop lactating at six months postpartum and continue feeding HM until her infant was one. However, Rhonda tasted her frozen HM at six months postpartum and felt it had expired; she discarded it all. Rhonda then continued to express and feed HM that had only been stored in the refrigerator until her infant was one.

These infant feeding strategies describe how infants were fed at a given time and were not static across infancy. Most mother–infant dyads switched between strategies throughout infancy depending on life events, resulting in distinct trajectories for each dyad. Some mothers began with predominant at‐the‐breast feeding and switched to incorporate expressed‐HM feeding when they returned to work. A couple of mothers switched from predominant at‐the‐breast feeding to exclusive expressed‐HM feeding when their child refused the breast. Several mothers stopped expressing HM when their child was over one year of age and reverted back to providing all HM at the breast because they felt they were able to provide sufficient food and other milk to supplement at‐the‐breast feeding when they were separated from their infant.

Infants ‘breastfeeding’ without the mother present

For many mothers, regardless of which HM‐feeding strategies they used, predominant at‐the‐breast feeding was preferred. Many mothers fed only at the breast when they were with their baby and when infants consumed expressed HM, it was most often fed by someone other than their mother. An exception to this general rule was mothers who exclusively expressed and fed expressed HM (strategy 4); these mothers often fed expressed HM. Non‐maternal caregivers who fed HM included the infant's father, grandparent, some other relative or a paid daycare provider:

‘I'll grab, you know, up to 10 to take to the sitter, where she freezes it and then she would thaw it out when she was ready to use it (okay). Or my husband would if I were gone.’ ( Fiona)

In one instance, an infant was able to consume HM and not require any formula or other milk‐based supplements for an entire week in the absence of her mother:

‘And then beginning of May, so she was 11 months, my husband took a trip for a week, and took the kids, and took my milk.’ ( Sadie)

Infants consuming shared HM

For some mothers, HM feeding was valued above all other forms of infant feeding. This led a small number of mothers to procure another mother's HM to feed to their infant when they could not provide their own. For the most part, infants who received shared HM consumed it from a bottle and were not fed at another mother's breast. Mothers were typically motivated to use shared HM because they were experiencing a short‐term problem with at‐the‐breast feeding. In these instances, shared HM bridged a gap until the infant's mother could provide her own HM (e.g. Fig. 1; Trajectory A).

Theme 3: How mothers describe breastfeeding and expressed HM‐feeding

Throughout interviews, mothers described their experiences with at‐the‐breast feeding and expressed HM‐feeding. Although we did not ask what mothers considered breastfeeding to mean to them, some used language that suggested equivalence between the two behaviours:

‘I breastfed all my children for the first year. They only received breast milk, as far as I know … so I pumped when I went back to work and everything and my [daycare] providers fed them milk I guess.’ ( Eve)

‘It wasn't different for [baby] … there's separation but he's still getting the same food.’ ( Fiona)

Conversely, other mothers used language that clearly described at‐the‐breast feeding and expressed HM‐feeding as different behaviours, for them and their infant:

‘…it's not an intimate experience when you're sitting there with a pump and you know, looking through magazines or waiting to be drained…’ ( Xena)

‘…when [my husband] tried to hold her like you would hold a baby when you're breastfeeding, like [baby] was not at all interested in anything that was sort of like breastfeeding but not breastfeeding.’ ( Olive)

Discussion

By analysing infant feeding qualitatively from the maternal perspective, we found that the majority of mothers in this sample used many different HM‐feeding strategies, incorporating HM expression and expressed HM‐feeding. This is of interest because studies describing the benefits of breastfeeding typically do not distinguish between at‐the‐breast feeding and expressed‐HM feeding. Thus, policy statements relating to breastfeeding, such as that of the American Academy of Pediatrics (Eidelman et al. 2012), have no section describing maternal or infant health outcomes by mode of HM delivery.

Of the infant feeding trajectories presented, mother–infant dyads in three of the trajectories would be classified as breastfeeding for 12 months by the NIS questions even though the mode of HM feeding ranged from predominantly feeding directly at the breast to predominantly feeding expressed HM from a bottle. One mother–infant dyad would be classified as breastfeeding for ten months even though the mother stopped producing HM at eight months postpartum. Our novel findings, and their unique pictorial representation, highlight that contemporary HM‐feeding strategies in the United States differ from how most health professionals and researchers talk about, recommend and measure breastfeeding.

As these data show, transfer of HM to an infant, as measured by the NIS questions, is not always the same as ‘breastfeeding,’ as reported by the CDC. Considering the infant feeding strategies and trajectories described by mothers in this study, the current breast feeding surveillance questions are insufficient to report prevalence and intensity of either at‐the‐breast feeding or expressed‐HM feeding. Thus, reports based on these questions oversimplify contemporary infant feeding practices.

The strategies for transferring HM to infants described in this paper raise several important questions: If an infant is being fed HM that has been stored, is that considered breastfeeding? If an infant is consuming HM after his/her mother has stopped lactating, is that considered breastfeeding? If an infant is being fed HM by a non‐maternal caregiver, is that considered breastfeeding? If an infant is consuming another mother's milk, is that considered breastfeeding? These questions are important because the current national breastfeeding surveillance questions in the United States are infant‐centric and consider any transfer of HM to the infant ‘breastfeeding.’ This may be an appropriate use of the word for some mothers, who used the term breastfeeding to have broad and multifaceted meanings that included expressed HM‐feeding. However, use of the word breastfeeding may be problematic for mothers who spoke about at‐the‐breast feeding and expressed HM‐feeding as different behaviours. Use of the word breastfeeding by researchers and public health officials is also problematic as it does not fully describe the complex HM‐feeding behaviours described in this paper. This is important because the behaviours described in this paper have four public health implications for both mothers and their infants.

First, health professionals and those involved in promoting optimum infant feeding should be aware that mothers may not be interpreting infant feeding recommendations as they expect. For example, saving stored HM and meting it out slowly to avoid using up stored HM too quickly implies that some mothers in this study traded ‘breastfeeding’ exclusivity for prolonged ‘breastfeeding’ duration. This prioritization of ‘breastfeeding’ duration over exclusivity may reflect how mothers internalize breastfeeding promotion messages. This is supported by research conducted in Australia (Berry et al. 2012) in which fewer parents were aware of the recommendation to exclusively breastfeed for six months than were aware of the recommendation to continue any breastfeeding to 12 months.

Second, labelling the duration of infant HM intake as ‘breastfeeding’ duration is problematic because the duration of infant HM consumption is not an appropriate proxy for intensity and duration of maternal HM production. There is a growing body of research in which associations between duration of maternal lactation and maternal health outcomes are reported. Thus, maternal lactation is an exposure of epidemiological importance. The focus on infant HM consumption in the US national ‘breastfeeding’ surveillance questions is of concern because it limits our ability to measure intensity and duration of maternal lactation. Greater intensity of breastfeeding is associated with less postpartum weight retention, and full breastfeeding has a greater effect than breastfeeding in combination with formula‐feeding (Krause et al. 2010, Brandhagen et al. 2013). The greater effect seen with full breastfeeding suggests that the volume of milk removed from the breasts is important in the association between lactation and postpartum weight retention. Recent research also described an association between increased duration of lactation and a reduction in risk factors for maternal cardiovascular disease (Schwarz 2015). The associations between lactation duration and postpartum weight retention and maternal outcomes related to cardiovascular disease warrant continued study. Accurate measurement of lactation intensity and duration is essential to such research.

Third, insufficient research has been published about the health outcomes associated with HM expression and expressed‐HM feeding. Both the altered composition of stored HM and bottle‐feeding HM have implications for infant health. Through the enteromammary pathway, mothers who feed at the breast can launch an immune response specific to a child's exposure to pathogens at a given time (Newburg & Walker 2007). Feeding HM that has been stored in the freezer exposes the child to immunoglobulins specific to the pathogens in their environment at the time of HM expression, not the time of consumption. This is important because some mothers in this study saved frozen HM for a time when their infant was sick. Whether or not frozen HM would be beneficial for a sick child months after expression is unknown. Studying health outcomes associated with expressed‐HM feeding is difficult because few researchers measure HM‐feeding mode. However, publications based on IFPS II data have described associations between expressed‐HM feeding and greater growth velocity (Li et al. 2012) and increased risk of coughing and wheezing episodes in the first year of life (Soto‐Ramírez et al. 2013). Measurement of HM‐feeding mode is essential to expand our understanding of the health outcomes associated with feeding expressed HM.

Fourth, until we know more about why, how and how many women are participating in HM sharing, we will be unable to provide families with evidence‐based, best‐practice advice about their infant feeding choices. The consequences of feeding an infant another mother's HM are unknown. The extent to which this behaviour is of public health concern depends on the prevalence of HM sharing, something that is not currently measured nationally. Research about HM sharing to date has mainly focused on women who have participated in the behaviour (Palmquist & Doehler 2014, Perrin et al. 2014). However, recent research suggests that awareness of this behaviour is high among a broad sample of mothers (Keim et al. 2014).

The main strength of this study is its use of qualitative methods. Qualitative research allows the researcher to explore ideas in more detail than a survey (Britten 1995) and may reduce investigator‐introduced bias by allowing data collection to be participant‐led (Britten 1995). Additionally, we recruited a large sample of mothers and purposively recruited to ensure diversity in our sample. However, we only recruited mothers who had experience of HM expression. This means that the voices of mothers who never expressed HM are not represented in this analysis. It is also possible that mothers who perceived their infant feeding experiences to have been more positive were more likely to respond to advertisements to participate in this study. This study is limited by the geographic location from which the mothers were recruited; it is unclear whether findings from this sample are transferable to other populations. The majority of our participants were older and more educated than the general population of mothers. However, this demographic breakdown is not surprising as it reflects the population of HM‐feeding women in the United States (Jones et al. 2011). Finally, it is worth noting that the characteristics of the interviewer—specifically that she had no personal experience of HM‐feeding—may have impacted the amount of information shared by participants. This may have been a strength if participants felt empowered by having more practical knowledge of infant feeding, leading them to share more. However, this may have been a weakness if participants did not divulge some details because they felt they were talking to an outsider, someone who would not understand their situation in the same way another mother might.

Conclusion

The HM‐feeding strategies and trajectories described by mothers in this study are far more complex than the behaviours described by the data that is collected by the current national breastfeeding survey questions. Although many mothers in this study voiced a preference for direct at‐the‐breast feeding, their personal circumstances (e.g. returning to paid employment) led them to employ alternative HM‐feeding strategies. Consequently, in an attempt to meet national or personal ‘breastfeeding’ goals, many mothers practiced their own variation of ‘breastfeeding’ by incorporating HM expression and expressed‐HM feeding. If researchers, public health professionals and clinicians are interested in obtaining information solely about infant HM consumption, then questions that do not distinguish between at‐the‐breast feeding and expressed HM‐feeding are likely sufficient. However, the HM‐feeding strategies described in this paper have public health implications and warrant further study. Thus, future research and national surveillance should use survey questions that appropriately delineate modes of infant feeding and allow reporting of maternal duration of lactation, infant duration of HM consumption at the breast and infant duration of HM consumption from a bottle as the distinct behaviours that this study has shown they are. Such data would enable us to compare maternal and infant health outcomes across HM‐feeding strategies and advise families about optimal infant feeding practices.

Source of funding

EJOS was funded by a Fulbright International Science and Technology Award.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributions

EJOS designed the research, collected and analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. SRG and KMR designed the research, contributed to data analysis and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Josephine Engreitz and So Young Park for assistance with qualitative data coding and analysis.

O'Sullivan, E. J. , Geraghty, S. R. , and Rasmussen, K. M. (2017) Human milk expression as a sole or ancillary strategy for infant feeding: a qualitative study. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13: e12332. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12332.

References

- Berry N.J., Jones S.C. & Iverson D. (2012) It's not the contents, it's the container: Australian parents' awareness and acceptance of infant and young child feeding recommendations. Breastfeeding Review 20, 31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binns C.W., Win N.N., Zhao Y. & Scott J.A. (2006) Trends in the expression of breastmilk 1993–2003. Breastfeeding Review 14, 5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitman J., Wood D.L., Mehta N.R., Hamosh P. & Hamosh M. (1983) Lipolysis of triglycerides of human milk during storage at low temperatures—a note of caution. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2, 521–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandhagen M., Lissner L., Brantsaeter A.L., Meltzer H.M., Haggkvist A.P., Haugen M. et al. (2013) Breast‐feeding in relation to weight retention up to 36 months postpartum in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study: modification by socio‐economic status? Public Health Nutrition, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten N. (1995) Qualitative interviews in medical research. BMJ 311, 251–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant A. & Charmaz K. (2007) The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory. SAGE: Los Angeles, Calif.; London. [Google Scholar]

- Butte N.F., Wills C., Jean C.A., Smith E.O. & Garza C. (1985) Feeding patterns of exclusively breast‐fed infants during the first four months of life. Early Human Development 12, 291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiday R.E., Wright C.M., Panter‐Brick C. & Parkinson K.N. (2004) Do early infant feeding patterns relate to breast‐feeding continuation and weight gain? Data from a longitudinal cohort study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 58, 1290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2014) Breastfeeding Report Card [Online]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2014breastfeedingreportcard.pdf [Accessed April 25th 2015].

- Chang Y.C., Chen C.H. & Lin M.C. (2012) The macronutrients in human milk change after storage in various containers. Pediatrics and Neonatology 53, 205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury R., Sinha B., Sankar M.J., Taneja S., Bhandari N., Rollins N. et al. (2015) Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica 104, 96–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons S.N. & Amir L.H. (2010) Breastfeeding women's experience of expressing: a descriptive study. Journal of Human Lactation 26, 258–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelman A.I., Schanler R.J., Johnston M., Landers S., Noble L., Szucs K. et al. (2012) Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 129, E827–E841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherman V.J., Gay B., Scott C., Aby J., Stewart A.L. & Lee K.A. (2013) Development of the breast milk expression experience measure. Maternal and Child Nutrition 9, 425–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza C., Johnson C.A., Harrist R. & Nichols B.L. (1982) Effects of methods of collection and storage on nutrients in human milk. Early Human Development 6, 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty S.R., Sucharew H. & Rasmussen K.M. (2013) Trends in breastfeeding: it is not only at the breast anymore. Maternal and Child Nutrition 9, 180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna N., Ahmed K., Anwar M., Petrova A., Hiatt M. & Hegyi T. (2004) Effect of storage on breast milk antioxidant activity. Archives of Disease in Childhood—Fetal and Neonatal Edition 89, F518–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare.Gov. (2015) Breastfeeding benefits [Online]. Available: https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/breast-feeding-benefits/. [Accessed April 25th 2015].

- Hornbeak D.M., Dirani M., Sham W.K., Li J., Young T.L., Wong T.Y. et al. (2010) Emerging trends in breastfeeding practices in Singaporean Chinese women: findings from a population‐based study. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore 39, 88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip S., Chung M., Raman G., Chew P., Magula N., Devine D. et al (2007) Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evididence Report/Technology Assessment (Full Rep), 1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jones J.R., Kogan M.D., Singh G.K., Dee D.L. & Grummer‐Strawn L.M. (2011) Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in the United States. Pediatrics 128, 1117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim S.A., McNamara K.A., Dillon C.E., Strafford K., Ronau R., Mckenzie L.B. et al. (2014) Breastmilk sharing: awareness and participation among women in the Moms2Moms study. Breastfeeding Medicine 9, 398–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent J.C., Mitoulas L.R., Cregan M.D., Ramsay D.T., Doherty D.A. & Hartmann P.E. (2006) Volume and frequency of breastfeedings and fat content of breast milk throughout the day. Pediatrics 117, e387–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M.S., Aboud F., Mironova E., Vanilovich I., Platt R.W., Matush L. et al. (2008) Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: new evidence from a large randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 65, 578–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M.S. & Kakuma R. (2012) Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8, p. CD003517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause K.M., Lovelady C.A., Peterson B.L., Chowdhury N. & Ostbye T. (2010) Effect of breast‐feeding on weight retention at 3 and 6 months postpartum: data from the north Carolina WIC programme. Public Health Nutrition 13, 2019–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labiner‐Wolfe J., Fein S.B., Shealy K.R. & Wang C. (2008) Prevalence of breast milk expression and associated factors. Pediatrics 122 (Suppl 2), S63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R.A. (1999) Storage of human milk and the influence of procedures on immunological components of human milk. Acta Paediatrica. Supplement 88, 14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Magadia J., Fein S.B. & Grummer‐Strawn L.M. (2012) Risk of bottle‐feeding for rapid weight gain during the first year of life. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 166, 431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Scanlon K.S. & Serdula M.K. (2005) The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutrition Reviews 63, 103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire S. (2011) x. Advances in Nutrition 2, 523–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan K., Harrison G.G., Afifi A.A., Nickel N., Jenks E. & Ramirez A. (2008) The association between an electric pump loan program and the timing of requests for formula by working mothers in WIC. Journal of Human Lactation 24, 150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J.M. & Bottorff J.L. (1988) The emotional experience of breast expression. Journal of Nurse‐Midwifery 33, 165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newburg D.S. & Walker W.A. (2007) Protection of the neonate by the innate immune system of developing gut and of human milk. Pediatric Research 61, 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmquist A.E.L. & Doehler K. (2014) Contextualizing online human milk sharing: structural factors and lactation disparity among middle income women in the US. Social Science and Medicine 122, 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin M.T., Goodell L.S., Allen J.C. & Fogleman A. (2014) A mixed‐methods observational study of human milk sharing communities on Facebook. Breastfeeding Medicine 9, 128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeu‐Nadal M., Castellote A.I. & López‐Sabater M.C. (2008) Effect of cold storage on vitamins C and E and fatty acids in human milk. Food Chemistry 106, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sankar M.J., Sinha B., Chowdhury R., Bhandari N., Taneja S., Martines J. et al. (2015) Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatrica 104, 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saumure K. & Given L. (2008) Data Saturation. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc. SAGE Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz K., D'arcy H.J., Gillespie B., Bobo J., Longeway M. & Foxman B. (2002) Factors associated with weaning in the first 3 months postpartum. The Journal of Family Practice 51, 439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz E.B. (2015) Invited commentary: breastfeeding and maternal cardiovascular health—weighing the evidence. American Journal of Epidemiology 181, 940–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shealy K.R., Scanion K.S., Labiner‐Wolfe J., Fein S.B. & Grummer‐Strawn L.M. (2008) Characteristics of breastfeeding practices among US mothers. Pediatrics 122, S50–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers E., Oldigs H.D., Santer R. & Schaub J. (2002) Feeding patterns in breast‐fed and formula‐fed infants. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 46, 243–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre D., López M.C., March L., Plaza A. & Martínez‐Costa C. (2006) Bactericidal activity of human milk: stability during storage. British Journal of Biomedical Science 63, 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto‐Ramírez N., Karmaus W., Zhang H., Davis S., Agarwal S. & Albergottie A. (2013) Modes of infant feeding and the occurrence of coughing/wheezing in the first year of life. Journal of Human Lactation 29, 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulier D. & Mercer J. (2009) Variables associated with breastfeeding duration. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 38, 259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]