Abstract

Undernutrition and low women's status persist as major development obstacles in South Asia and specifically, Nepal. Multi‐sectoral approaches, including nutrition‐sensitive agriculture, are potential avenues for further reductions in undernutrition. Although evidence is growing, many questions remain regarding how gender mediates the translation of agricultural production activities into nutritional benefit. In this study, we examined how gender influences the pathway from agricultural production to improved income and control of income, with a focus on five domains of empowerment: decision‐making power, freedom of mobility, social support, workload and time, and self‐efficacy. For this, we conducted a qualitative retrospective assessment (N = 10 FGDs) among 73 beneficiary women of a nutrition‐sensitive agriculture programme implemented from 2008 to 2012 in two districts of Nepal—Baitadi and Kailali. We found that women reported increased decision‐making power, new knowledge and skills, increased recognition by their family members of their new knowledge and contributions, and self‐efficacy as farmers and sellers, whereas workload and time were the most consistent constraints noted. We also found that each empowerment domain operated differently at different stages of the pathway, sometimes representing barriers and at other times, opportunities and that the interconnectedness of the domains made them difficult to disentangle in practice. Finally, there were major contextual differences for some domains (e.g., freedom of mobility) between the two districts. Future policies and programmes need to include in‐depth formative research to ensure that interventions address context‐specific gender and social norms to maximise programmatic opportunities to achieve desired results.

Keywords: homestead food production, Nepal, nutrition, nutrition‐sensitive agriculture, socio‐cultural analysis, women's empowerment

Key messages.

Women's empowerment can act as a barrier or facilitator at each step along the pathway for the translation of agricultural inputs into nutritional outcomes.

The role of gender in the agriculture to nutrition impact pathway may vary by location given variation in other social and contextual factors which each interact with gender in complex ways.

Nutrition‐sensitive agricultural programmes should invest in context‐specific formative research on how gender mediates planned pathways from agriculture to nutrition to ensure appropriate design of interventions.

1. INTRODUCTION

Agricultural labour is the primary means of income for 60–70% of the world's population (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2013; The World Bank, 2015). Women represent a significant part of the agricultural workforce in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs), but gender inequality presents barriers to inclusive agricultural development (The World Bank, The Food and Agricultura Organisation, & The International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2008). Agriculture is one of the most important sources of livelihood in South Asia (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2013), but limited decision‐making power, restricted freedom of movement/mobility, heavy workload burdens, and limited support systems are some of the barriers that prevent women from making their own choices in agriculture (Alkire et al., 2013; Bushamuka et al., 2005; Engle, Menon, & Haddad, 1999; Gurman, Ballard, Kerr, Walsh, & Petrocy, 2016; Gurung, Partap, & Choudhary, 2015; Malhotra & Boender 2002). Access to food is a major determinant of food security (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2008). Therefore, empowering women farmers has become a global goal to improve nutrition in the household, particularly for women and children (The Food and Agriculture Organization, The International Fund for Agricultural Development, & The World Food Programme, 2015). Living in traditionally gender‐restrictive societies makes it challenging for mothers to provide sufficient food and of adequate nutritional quality for themselves and their children (Engle, Menon, & Haddad, 1999; Smith, Ramakrishnan, Ndiaye, Haddad, & Martorell, 2003). Nearly half of the world's undernourished population lives in South Asia and the low status of women has been identified as a key contributing factor (Cunningham, Ruel, Ferguson, & Uauy, 2015; Ramalingaswami, Jonsson, & Rohde, 1996; World Bank, 2014).

Increases in agricultural production will not automatically translate into improved nutrition outcomes. There are multiple agriculture to nutrition pathways and how gender interacts along the pathways is complex (Kadiyala, Harris, Headey, Yosef, & Gillespie, 2014a, 2014b). Current evidence suggest that multi‐sectoral approaches, including nutrition‐sensitive agricultural development, are needed for further reductions in undernutrition (Black et al., 2013; Food and Agriculture Organization, 2013). Recent reviews have identified diverse factors that enhance or impede nutritional gain from agricultural investments and classified these into six pathways for how agriculture to nutrition pathways operate in South Asia specifically: (a) agricultural production for own consumption, (b) agricultural production to sell for income gain, (c) agricultural policies and food prices that influence production and technology decisions, (d) agricultural production as a means of empowering women farmers, (e) agricultural labour and related time requirements which trade‐off with childcare practices, (f) agricultural labour and associated risks for women farmers, which can contribute to intergenerational undernutrition (Kadiyala, Harris, Headey, Yosef & Gillespie, 2014a, 2014b; Yosef, Jones, Chakraborty, & Gillespie, 2015). Although each of these six pathways plays out differently for men and women, the last three pathways explicitly focus on the gendered dimensions of agriculture to nutrition linkages. Despite increasing recognition of the importance of these pathways, knowledge gaps remain as to how these pathways interact and particularly how women's empowerment and gender dynamics may influence each of the pathways (McDermott, Johnson, Kadiyala, Kennedy, & Wyatt, 2015; Ruel, Alderman, & Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group, 2013).

Recent research on gender and nutrition‐sensitive agriculture has been primarily quantitative, and little qualitative work has been done to understand how gender‐related dynamics operate to facilitate or impede predefined agriculture to nutrition pathways. This contextual understanding is particularly important for programmes, especially in South Asia where women's empowerment is known to be low, that aim to simultaneously improve women's status, agricultural production, and nutritional well‐being. In this study, we examine how gender dynamics influence the steps along the income‐related agriculture to nutrition pathway.

2. METHODS

2.1. Intervention description

Helen Keller International's (HKI) Enhanced Homestead Food Production (EHFP) programmes aim to improve nutritional well‐being for women and their children (Meinzen‐Dick, Behrman, Menon, & Quisumbing, 2012) and generally include three components: (a) physical inputs for homestead gardening and small livestock rearing, (b) behaviour change communication to promote awareness of essential nutrition actions and essential hygiene actions, and (c) strengthening of multi‐sectoral governance (Haselow, Stormer, & Pries, 2016). Evidence from HKI's EHFP programmes in Nepal, Bangladesh, and Cambodia has illustrated how these kinds of programmes can benefit dietary quality, food security, nutritional outcomes, and women's status, decision‐making, and income levels (Bushamuka et al., 2005; HKI, 2010; Talukder, Huq, Pee, Darnton‐Hill, & Bloem, 2000). Recent studies in Nepal have shown the complexity of agriculture, gender, and nutrition dynamics Cunningham et al., 2015; Malapit, Kadiyala, Quisumbing, Cunningham, & Tyagi, 2015), including the way that these integrated EHFP programmes can improve diets and nutrition‐related outcomes in women and their children (Cunningham et al., 2017; Dulal, Mundy, Sawal, Rana, & Cunningham, 2017).

Nepal suffers from one of the highest rates of food insecurity worldwide, affecting nearly half of the rural population (Population Division Ministry of Health and Population. Government of Nepal, 2011). Undernutrition remains a major public health problem in Nepal: 17% of women between 15 and 49 years of age are thin or undernourished (<18.5 kg/m2), and 27% of children under 5 years of age are stunted (weight‐for‐age; Nepal Ministry of Health, New ERA, & ICF, 2016). In rural Nepal, long‐standing discriminatory socio‐cultural practices limit women's access to opportunities (Department for International Development & The World Bank, 2006).

From 2008 to 2012, HKI‐Nepal led a programme titled Action Against Malnutrition through Agriculture (AAMA) in three Far‐Western districts of the country: Kailali, Baitadi, and Bajura (McNulty, Nielsen, Pandey & Sharma, 2013). AAMA sought to improve household‐level dietary diversity and reduce food and nutrition insecurity, particularly among pregnant and lactating women and children under 2 years of age, targeted as homestead food production beneficiaries (HFPBs), based on hypothesised programme impact pathways (Figure 1). Village model farmers (VMFs) were project volunteers and key resource persons at the ward‐level, the lowest administrative unit in Nepal. Each ward had one VMF, who was responsible for one or two groups of about 20 HFPBs each. The VMFs were given training, physical inputs (e.g., seeds and chicks), and ongoing supportive supervision to start model gardens and poultry raising. In turn, the VMFs provided training and technical support as well as distributed seeds and chicks to HFPBs to help them establish and improve their home gardens for vegetable production and facilities for poultry raising. The VMFs also organised monthly meetings with HFPBs to discuss essential nutrition actions and essential hygiene actions, as well as farming techniques and poultry rearing. An evaluation at the end of the programme, conducted in 2013, in Kailali and Baitadi, found that many beneficiaries continued to sell excess production to generate income (McNulty et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Programme impact pathways for Helen Keller International's action against malnutrition through agriculture

2.2. Study description

In this study, we used data from a qualitative study conducted to examine the factors that have influenced sustainable income generation activities 4 years after completion of AAMA. HKI's programme impact pathways framework guided conceptualisation for how AAMA activities should translate into outputs, outcomes, and impact. In this study, we assessed the role of gender dynamics along the agriculture to nutrition income pathway, specifically the translation of inputs into outputs and outcomes. Based on a review of the literature and discussions with experts on gender and Nepal, four predetermined empowerment domains were included a priori in this study and a fifth domain (perceived self‐efficacy) emerged during analysis:

women's decision‐making power, defined as “women's agency to make strategic life choices and affect outcomes of importance to themselves” (Kabeer, 1999) and operationalised to mean agency relating to household choices and control over resources related to farming, selling vegetables, and income;

workload and time allocation, defined as how “individuals spend or allocate their time over a specified period with an interest in paid and non‐paid work” (Alkire et al., 2013; Bardasi & Wodon, 2006) and considered in this study as the time required to engage in farming and other AAMA activities;

restricted mobility or the lack of freedom to be “exposed to public sphere” (Schuler, Hashemi, Cullum, & Hassan, 1996), operationally defined in this study as freedom to sell in markets, attend mother's group meetings and visit others without feeling restrictions from household members;

social support networks, defined as “access to networks of support on a household and community level” (Malhotra & Boender, 2002) and operationalised to include support from family members, women's groups, neighbours and government frontline workers which may influence women's investments in farming or participation in AAMA activities; and

perceived self‐efficacy, or “women's ability to define self‐interest and choice, and consider themselves as not only able, but entitled to make choices” (Bandura, 1982; Malhotra & Boender, 2002) and in this study related to a woman's level of confidence and interest in both agricultural production practices as well as, sharing of her knowledge with others in the household, or acting upon her gained knowledge and skills to make decisions.

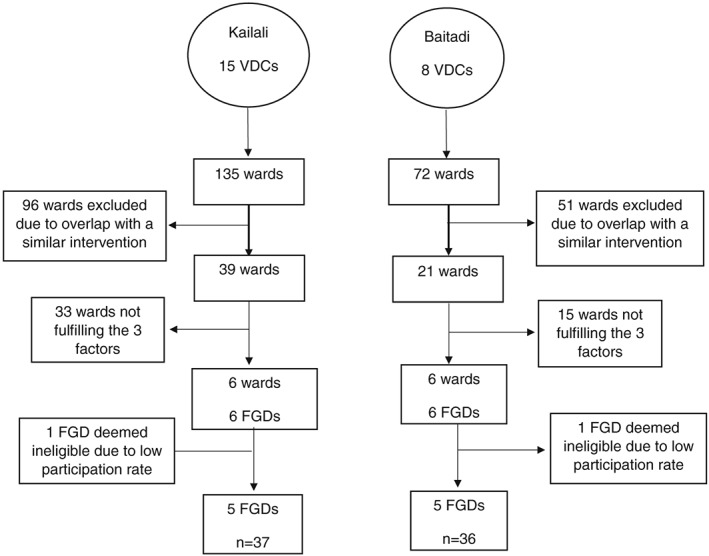

This study was carried out in two AAMA intervention districts—Kailali and Baitadi—selected because they were the early intervention districts and thus received the full package of AAMA inputs (Figure 2). All wards (n = 207) within the 15 village district committees in Kailali and 8 village district committees in Baitadi where AAMA was implemented were initially identified for recruitment of study participants. However, wards currently receiving a similar HKI intervention (32) were removed. The final sampling frame included 39 wards in Kailali and 21 wards in Baitadi. From these 60 remaining wards, six study wards in each district (n = 12) were purposively selected based on three criteria: (a) whether a regular market was easily accessible, (b) whether the ethnic and caste diversity within the ward resembled that of the district, and (c) whether the wards were easy for researchers to access. Within each ward, one focus group discussion (FGD) of at least six HFPBs was planned, but two FGDs (one in each district) were cancelled due to lack of sufficient HFPBs available to participate.

Figure 2.

Study sample design. FGD = focus group discussion; VDC = village district committee

As the overall study purpose was to look at continued HFP practices related to the income pathway (e.g., selling at markets), VMFs and researchers purposively recruited potential HFPB FGD participants into three categories: (A) HFPBs currently generating income from their home garden production; (B) HFPBs who had previously generated income from their home garden, in the past, but are no longer doing so; and (C) HFPBs who have never generated income from their gardens. Recruitment for participation involved a short survey to capture information on demographics, vegetable production, livestock ownership and market/selling practices, to place individuals into the appropriate FGD category. In total, 144 HFPBs were recruited. Within each ward, the category (A, B, or C) with the largest number of HFPBs was chosen as the FGD for that ward and 75 women who had been categorised into the selected group were invited to be FGD participants. In total, 73 HFPBs participated in the FGDs (n = 10): six Category A FGDs, one Category B FGD, and three Category C FGDs.

The HKI study team hired and trained local FGD facilitators, familiarising them with the FGD study guides and data collection techniques. The FGD tools included open‐ended questions on a wide range of topics related to agriculture to nutrition impact pathways, particularly the income pathway, and explicitly included questions and discussion prompts relating to the four gender and empowerment themes. The gender questions were the same across all three types of FGDs. The topic guide included an interview agenda with prompts to ensure consistency in coverage of themes in each FGD. An observer and facilitator was present at each FGD, ensuring that the topic guide was followed, all the planned topics were discussed and that detailed notes of the FGD were maintained. Each FGD was conducted in the local language (Tharu in Kailali and Doteli in Baitadi), lasted approximately 1 hr and was audio‐recorded. Professionals in each district transcribed the recordings verbatim and translated the text from local languages into Nepali. The Nepali transcripts were then translated into English.

Analysis of the FGD data was done using a thematic content approach. For this gender analysis, we focused exclusively on the gender‐related themes, which included analysing all data collected both in response to the specific gender‐related FGD questions as well as gender‐related responses to any of the other FGD questions. Two analysts created a priori code lists based on the four gender‐related themes: decision‐making power, mobility, workload, and social support. Three analysts read through the transcripts to become familiar with the data and created summary memos of each FGD. During this process, new themes and patterns were noted and the coding list was updated. Following the sampling design, transcripts were grouped into the three categories—A, B, and C—for coding and analysis. Each transcript was read and coded several times. An iterative approach was used to finalise the coding list and code the data, using QSR International's NVivo 10 Software. An additional gender‐related theme—self‐efficacy—emerged during this process. Seventeen subthemes were developed, and each code was then classified into the appropriate theme and subtheme. Coded transcripts were explored, patterns discovered, key findings structured under each of the five themes and ultimately along each step of the agriculture to nutrition income pathway. We show results for each domain of women's empowerment (five themes) and for how gender dynamics operate as a barrier and/or facilitating factor for women at each step along the agriculture to nutrition income pathway.

The overall study obtained ethical approval from the Nepal Health Research Council. For the gender analysis, ethical approval was also obtained from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Informed consent was obtained from each FGD participant, either by signature or by finger stamp, prior to the start of any data collection.

3. RESULTS

In this section, we will present our findings by theme (decision‐making, freedom of mobility, social support networks, workload and time use, and self‐efficacy). We will first show our overall findings and then also highlight similarities and differences among the FGD categories (A, B, or C) that emerged.

3.1. Decision‐making

Almost all women from the FGDs reported being able to decide which crops to grow, what techniques to apply, and which fertilisers to use. And in Kailali, most women pointed out during the FGDs that they made many of the decisions on selling vegetables: “We do [decide to sell] ourselves. We select and pick the vegetables and take [them to the market] to sell ourselves” (Kailali, FGD 4). In Kailali, women from most FGDs also decided over market and selling activities and explained how the shift to becoming income holders gave them a new position of authority in the household: “If we discuss [a topic] in the meetings we can share the information with the family, which supports the family. We talk to other family members about the knowledge we gained from the meeting and they become happy” (Kailali, FGD 4). These HFPB women noted in the FGDs that open communication improved within their families, creating an environment for joint decision‐making. In contrast, in most FGDs in Baitadi, women reported not being able to make final decisions about whether to engage in EHFP group meetings or in selling produce from their home gardens: “Head of the family [decides to sell]. It also is discussed among other family members too. And when there is no head of the family at home, we ask with village leaders” (Baitadi, FGD 6).

Variation was found regarding decision‐making in the farming activities among the three categories of FGDs: Almost all women in category A FGDs reported making independent decisions regarding farming activities, such as which crops to plant and which fertiliser to use, as illustrated from the FGD 4 quote above. However, all Category B and C FGD participants reported that decisions are made jointly or by the head of household: “Everyone at home discuss, if they learn that doing this will give high yield. We all used to decide together sir” (Baitadi, FGD 10).

3.2. Freedom of mobility

During FGDs in both districts women described that they often discussed market‐related activities and obstacles and how to overcome them. What contrasted between the two districts was that few women in FGDs in Kailali reported discussing selling matters with other family members, whereas this was reported to be a common practice in Baitadi where all women in FGDs noted the need to get permission before leaving the house because travel to the market was done as a family and not alone. However, most noted that the requirement to get permission did not hinder women from going: “In the beginning, it used to be hard [to go on our own]. But these days, people do not get angry or scold right away” (Baitadi, FGD 9). In the FGDs in Baitadi, women also reported that family members often restrict women from attending women's groups or visiting friends/relatives: “There are jobs at home. We have to ask for money from family members. This creates difficulties” (Baitadi, FGD 10). This was not mentioned as a barrier in Kailali.

Variation was not found regarding freedom of movement among the three categories of FGDs: in all three categories, all women reported being able to go to markets and most to participate in women's group, whereas only a few in each category were able to visit others freely.

3.3. Social support networks

In both districts, a barrier experienced by most women in the FGDs was the limited support received from family members for their domestic work and childcare, making greater participation in EHFP activities and household agricultural activities challenging. There was a clear distinction between what was perceived as women's and men's work; women reported that men rarely participated in childcare or domestic work. A typical comment was, “husbands cooking? No, I cook” (Baitadi, FGD 10). Most women in the FGDs in Baitadi noted that family members did not always support their attendance at group meetings due to the importance given to domestic chores: “I still get scared thinking that my mother‐in‐law will get angry, if I'm late. She gets angry and asks, what did you do for this long? Why did you go?’” (Baitadi, FGD 9).

Women in the FGDs in Kailali revealed that family members supported their attendance at EHFP group meetings, as they recognised their importance: “earlier they used to question us on how many and what types of groups we attended. These days, they encourage us to know about new groups” (Kailali, FGD 5). Women revealed during the FGDs that prior to AAMA, women felt restricted by their household duties, with limited or no permission to go to markets, which they felt impacted on their domestic work: “they used to say we are shameless people to sell vegetables. But [they don't say that] anymore these days. Even my husband used to … now, he doesn't say anything as I have learned many things” (Kailali, FGD 5).

Some variation was found regarding social support network among the three categories of FGDs: Family support was consistent for all three categories, whereas group support was only reported by most women in Category A FGDs and very few women in Category B and C FGDs. It seemed that women in Category A FGDs had different sources of social support, whereas nearly all women in Category B and C FGDs either reported poor support, family, or group support but not both.

3.4. Workload and time use

Single responsibility for childcare and domestic work as well as lack of resources (e.g., water and poor irrigation) were discussed as factors that affect women's total work burden and in turn, prevented the full uptake of AAMA‐promoted agricultural activities in both districts. It was commonly revealed by HFPB women during FGDs that AAMA placed additional time burdens on them as it required attendance at HFPB group meetings, promoted participation in market activities, and use of new techniques to increase the production of nutritionally rich crops. A woman from one FGD explained how this was not feasible for her: “I don't have time to try new things, such as starting to grow new things. Overall, I have a very high workload” (Baitadi, FGD 7).

In both Kailali and Baitadi, workload and time constraints influenced women's choice of crops. In some FGDs, women reported that HFPBs chose simple, less time‐demanding crops and sometimes decided to limit the amount of production given the anticipated time involved in market‐related activities: “Who would go to sell? The market is far, so I only plant for what we will eat at home” (Kailali, FGD 3). Distance to markets and poor infrastructure and transportation created an additional time burden, reported in both districts. “If there was market access or they came to our doorstep to buy the vegetables, why wouldn't we do it? It [production] is sufficient for household consumption. As I am alone at home, I also have other household chores. Who would go that far to sell?” (Kailali, FGD 3). However, women from most FGDs reported that although AAMA activities required additional time and labour for agriculture and group activities, the additional income was a benefit that outweighed these negative effects of the programme: “We used to only produce for household consumption. We didn't think of selling... Now we can earn money from selling. I feel happy. We have to work harder, though” (Kailali, FGD 1).

Variation regarding the workload and time themes among Category A, B, and C FGDs was limited. Furthermore, all women from all FGDs expressed limited time for leisure; high workload may have been the main reason for why some HFPBs stopped selling their produce and were in the particular FGD category. Although participants in Category C FGDs do not sell vegetables, they also emphasised their very high workload already due to their engagement in vegetable production for home consumption, household chores, and childcare as well as group meeting attendance.

3.5. Self‐efficacy

The trainings on farming techniques, physical inputs, and ongoing support given by VMFs seemed to provide the HFPBs with the skills, knowledge, and agency to take control of and make independent farming decisions: “At first, we didn't know anything. Later, through training, we learned about vegetable production and the use of fertiliser. We came to know about hybrid seeds and that higher yields would generate greater income” (Baitadi, FGD 8). HFPBs in FGDs across both districts reported that, prior to AAMA, they felt shy and were unaware of their skills and knowledge, making their participation in household decisions limited. However, a perceived increase in self‐efficacy was commonly expressed by HFPBs during the FGDs, as they now had rich knowledge on both agriculture and nutrition, as well as how optimal dietary practices can prevent malnutrition, as described by a woman in one FGD: “We could not even speak this much earlier. We used to quiver while speaking. Now the fear is gone” (Kailali, FGD 2). Their deep discomfort when expressing themselves publicly, low self‐esteem, and lack of belief in themselves were no longer major barriers.

The opportunity for open dialogue created by the women's groups was noted by HFPBs from all FGDs in Kailali as a reason for the changes they experienced. “We speak in front of people. Before going to the group meeting, I could not even introduce myself and now we can because of being involved in this mothers group. We used to feel afraid to talk. We used to only smile with the project staff” (Kailali, FGD 4). In contrast, in some FGDs in Baitadi, women emphasised that the group meetings were not an appropriate space for them to express themselves. One woman from one FGD noted how she needed to keep her thoughts to herself: “because of the social mindset that women should not go alone, [I attend to] the load of housework [instead]. I face problems like this” (Baitadi, FGD 7). The benefits of discussions with other women were not commonly expressed in FGDs; the need to return home quickly and attend to household chores was commonly expressed as a reason for this.

No variation was found regarding perceived self‐efficacy among women who participated in the three categories of FGDs.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study explores the role of gender dynamics as barriers and facilitators along the agriculture to nutrition income pathway, focusing on five key themes: decision‐making power, freedom of mobility, social support, workload and time, and self‐efficacy. Overall, during the FGDs, mothers revealed a perception of increased self‐efficacy as farmers and sellers, following from new knowledge and skills gained from AAMA. Workload and time were the most consistent constraints mentioned by women in most FGDs. However, these various gender domains may operate differently at various steps along the agricultural to nutrition income pathway, sometimes representing barriers and at other times, opportunities. Thus, in this section, we link our empirical findings from the thematic analysis of gender dynamics to each step along the agriculture to nutrition income pathway: inputs to outcomes, outcomes to outputs, and outputs to impact.

The first step of the agriculture to nutrition income‐related pathway involves the translation of inputs from a nutrition‐sensitive agricultural intervention into nutrition‐sensitive agricultural practices. The fact that women in almost all FGDs expressed an ability to make household‐level farming decisions, and not be restricted from movement related to household‐level farming activities, served as gender‐related facilitating factors. Women in these FGDs commonly reported a change in perceived self‐efficacy as farm holders, although the lack of social support and workload were two prominent interrelated barriers to the translation of inputs to outputs.

The second step of the agriculture to nutrition income‐related pathway involves converting nutrition‐sensitive agricultural practices into income generating activities. The perception of self‐efficacy and confidence to sell agricultural products in markets served as a facilitator, whereas workload and time constraints were nearly universally noted as major barriers to selling and earning additional money from their produce. Some gender‐related facilitating factors differed between Kailali and Baitadi. Although women in FGDs in Kailali revealed a common perception that HFPBs could make decisions about their own participation in HFPB groups and selling of produce, they were not restricted from travelling to group meetings and markets and they had support from family members to participate in AAMA activities and were confident to speak up. This was not the case in Baitadi, where the FGDs revealed perceptions of significant gender barriers at this point in the pathway. Workload and time constraints were both barriers.

The third step of the agriculture to nutrition income‐related pathway involves moving from income‐generation to household income‐related decisions. In both districts, joint financial decision‐making and self‐efficacy as income earners and holders of new knowledge were key facilitating factors at this stage, whereas the lack of social support among household members remained a barrier. In Baitadi, lack of self‐efficacy as knowledge holders remained a barrier at this stage. The perception that knowledge and power have a linear relationship was apparent as was the way in which women in the FGDs revealed synergies between new knowledge and skills, joint decision‐making, and self‐efficacy.

Although the two districts seemed to react similarly to programmatic inputs, there were more barriers in Baitadi, than in Kailali, for the later stages of the income pathway. This highlights an important point: gender barriers and facilitating factors may vary by location as gender is intertwined with other socio‐cultural dynamics. Households in Baitadi are generally more remote than in Kailali. Therefore, Baitadi has poorer transportation and communication facilities, less access to markets, and sometimes less beneficial climate and terrain for farming, which are all contributing factors to high transaction costs and risks in marketing of their produce (Thapa, 2009). Other social issues, such as caste and ethnicity, could also contribute to these findings. The Tharu community is settled throughout the Terai in the Far West (Lynn, Dahal, & Govindasamy, 2008). Women from Tharu communities are relatively empowered, reflecting a gender equal social norm in their communities that has been deeply integrated in their culture for centuries (Verma, 2009). The AAMA programme may have entered an already enabling environment for change in Kailali, particularly for decision‐making and mobility, making them more receptive to new knowledge and practices (Maslak, 2003). On the other hand, in the Hills of Nepal, the higher caste group of Chhetris is one of the most prominent ethnic groups; the strict hierarchical Hindu structure is still deeply embedded in the Chhetri daily lives (Lynn, Dahal, & Govindasamy, 2008). The men have traditionally dominated high ranks in the army, police, and government positions, possibly reflecting strict and conservative ideals, whereas women were expected to take care of the household and be good wives (Department for International Development & The World Bank, 2006). These traditions are still commonly practiced in the hills (Population Division Ministry of Health and Population. Government of Nepal, 2011) and could partly describe how Chhetri women in this study emphasised their strong sense of responsibility for domestic work and great dependence in their families compared to the Tharu women in Kailali (Maslak, 2003).

Workload and time constraints, as well as lack of support in household chores, were barriers expressed by women during FGDs throughout all stages of the project. Women in LMICs often already face a heavy work burden by holding primary responsibility for both domestic work and childcare, and the additional demand of agricultural labour may carry nutritional risks if the mother is forced to make trade‐offs between time for agricultural work and childcare (McGuire & Popkin, 1990). Further, in Nepal, migrating for work is common: About 60% of households had at least one migrated family member at some point within the past 10 years (Nepal Ministry of Health, 2016). These emigration trends are changing demographics in Nepal and particularly, gender‐related household roles and responsibilities. For example, women's decision‐making power may increase, as it is often men who migrates for work, but women's workload may also increase as women take on additional responsibilities (HKI, 2010). Programmes will need to address these specific workload and time‐related barriers to achieve the full possible positive impact for beneficiaries.

Self‐efficacy emerged as the most constant facilitating factor across all stages: It helped to translate inputs into both outputs and outcomes. Evidence has illustrated the strong relationship between self‐efficacy and behaviour change (Strecher, McEvoy DeVellis, Becker, & Rosenstock, 1986). In our setting, programme participants successfully adopted new behaviours, demonstrating gains in knowledge and translation into improved agriculture and nutrition‐related practices. Bandura discovered that achieving desired behaviour changes often results partly from people judging their own capabilities (Bandura, 1982). AAMA's trainings and follow‐up interactions with mothers, primarily via VMFs, seem to have raised their level of self‐efficacy. Their personal farming practices and structured observations of people from a similar background succeeding in these new practices likely helped to generate the strong sense of self‐efficacy reported by mothers in this study (Brown & Dillon, 1978). The findings in Baitadi showed that despite increased self‐efficacy, women's financial authority in the household was limited, and this may indicate the need for agriculture and nutrition programmes to have explicit gender‐related goals and strategies for overcoming gender‐related barriers. Although the AAMA programme did not have a gender component to it (McNulty et al., 2013), HKI has since then incorporated gender as an essential component of EHFP programmes (United States Agency for International Development, 2015).

As the first qualitative study to assess how gender dynamics operate throughout the agriculture to nutrition income pathway, this study's unique contribution is evident. However, several study limitations should be noted. First, the use of only FGDs for this study means that the findings are likely shaped by social response bias (Goffman, 2008). Each individual may not have authentically shared their experiences, particularly if the experience deviates from socially accepted norms. However, we think that the findings remain valid and are still useful for understanding culture and key behaviours and beliefs related to the study in this context. Second, given purposive selection of study respondents based on three predetermined FGD categories, we did not have an equal number of respondents per category. With only one FGD in Category B and three in Category C, it is unclear how representative these individual's responses were of others who would have also fit into these categories. Third, one researcher conducted all the coding and data analysis which increases the subjective biases from this person's work but avoided issues of coding fidelity. Finally, we found each of the gender themes to be interlinked and difficult to disentangle in practice, but realised that analysis by these somewhat artificial groupings was important to create structure to the analysis and be consistent with an emerging literature base in which these themes are common.

This study has highlighted the importance of these household gender dynamics as critical factors in nutrition‐sensitive agricultural programmes seeking to increase women's involvement in production and their access to markets. However, knowledge gaps on how gender plays into agriculture to nutrition pathways persist. Further studies are needed to have a better understanding of how geographic location, ethnicity, caste, socio‐economic status, and gender dynamics interact. Additional research, both qualitative and quantitative, is needed to truly understand the nature of the agriculture to nutrition income pathway and how gender dynamics mediate these pathways (and/or operate as independent pathways) in different locations throughout South Asia. In addition to rigorous research studies needed on these topics, this study highlights the importance of similar formative research studies that are needed to ensure appropriate design of interventions, given the variations found between the two districts in how women's empowerment operated along the agriculture to nutrition pathway studied. Once barriers are understood, targeted approaches that address locally, culturally specific subnational contexts are possible.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

DD was the only author who had worked for Helen Keller International's AAMA program, but the program had ended by the time of this retrospective study. Thus, the authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest for this study.

CONTRIBUTIONS

CK led the data analysis and drafting of the paper, with guidance and feedback from co‐authors throughout. All authors participated in study and tool design, selection of the manuscript topic, framing the analysis and write‐up, and reviewing of drafts. All co‐authors have read and approved of the final version of the paper and its submission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to colleagues at HKI, specifically Ame Stormer, and at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, particularly Shari Krishnaratne who provided intellectual support throughout the project. The authors are also grateful for the funding from Mickey Leland International Hunger Fellowship, that funded one author's contributions to the study.

Kjeldsberg C, Shrestha N, Patel M, Davis D, Mundy G, Cunningham K. Nutrition‐sensitive agricultural interventions and gender dynamics: A qualitative study in Nepal. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14:e12593 10.1111/mcn.12593

REFERENCES

- Alkire, S. , Meinzen‐Dick, R. , Peterman, A. , Quisumbing, A. , Seymour, G. , & Vaz, A. (2013). The women's empowerment in agriculture index. World Development, 52, 71–91. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self‐efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bardasi, E. , & Wodon, Q. (2006). Measuring time poverty and analyzing its determinants: concepts and application to Guinea. Gender, time use, and poverty in Sub‐Saharan Africa, 73, 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Black, R. E. , Victora, G. , Walker, S. P. , Bhutta, Z. A. , Christian, P. , De Onis, M. , … Martorell, R. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low‐income and middle‐income countries. The Lancet, 382(9890), 427–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, I. , & Dillon, I. K. (1978). Learned helplessness through modeling: The role of perceived similarity in competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(8), 900–908. [Google Scholar]

- Bushamuka, V. N. , de Pee, S. , Talukder, A. , Kiess, L. , Panagides, D. , Taher, A. , & Bloem, M. (2005). Impact of a homestead gardening program on household food security and empowerment of women in Bangladesh. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 26(1), 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, K. , Ploubidis, G. B. , Menon, P. , Ruel, M. , Kadiyala, S. , Uauy, R. , & Ferguson, E. (2015). Women's empowerment in agriculture and child nutritional status in rural Nepal. Public Health Nutrition, 18(17), 3134–3145. 10.1017/s1368980015000683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, K. , Ruel, M. , Ferguson, E. , & Uauy, R. (2015). Women's empowerment and child nutritional status in South Asia: A synthesis of the literature. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 11(1), 1–19. 10.1111/mcn.12125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, K. , Singh, A. , Pandey Rana, P. , Brye, L. , Alayon, S. , Lapping, K. , & Klemm, R. D. (2017). Suaahara in Nepal: An at‐scale, multi‐sectoral nutrition program influences knowledge and practices while enhancing equity. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 1–13. 10.1111/mcn.12415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department for International Development, & The World Bank (2006). Unequal citizens ()Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Nepal: Retrieved from Kathmandu: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/745031468324021366/Executive-summary [Google Scholar]

- Dulal, B. , Mundy, G. , Sawal, R. , Rana, P. P. , & Cunningham, K. (2017). Homestead food production and maternal and child dietary diversity in Nepal: Variations in association by season and agroecological zone. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle, P. L. , Menon, P. , & Haddad, L. (1999). Care and nutrition: Concepts and measurement. World Development, 27(8), 1309–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2008). Introduction to the basic concepts of food security. Italy: Retrieved from Rome; http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/al936e/al936e00.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2013). Synthesis of guiding principles on agriculture programming for nutrition. Italy: Retrieved from Rome; http://www.fao.org/docrep/017/aq194e/aq194e00.htm [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. (2008). Behavior in public places. Simon and Schuster: London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Gurman, A. T. , Ballard, A. , Kerr, S. , Walsh, J. , & Petrocy, A. (2016). Waking up the mind: Qualitative study findings about the process through which programs combining income generation and health education can empower indigenous Guatemalan women. Health Care for Women International, 37(3), 325–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung, M. B. , Partap, U. , & Choudhary, D. (2015). Empowering mountain women through community‐based high value product value chain promotion in Nepal. International Journal of Agricultural Resources, Governance and Ecology, 11, 330–345. [Google Scholar]

- Haselow, N. J. , Stormer, A. , & Pries, A. (2016). Evidence‐based evolution of an integrated nutrition‐focused agriculture approach to address the underlying determinants of stunting. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12(S1), 155–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helen Keller International . (2010). Homestead food production model contributes to improved household food security, nutrition and female empowerment: Experience from scaling‐up programs in Asia Retrieved from Phnom Penh, Cambodia: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/wa_workshop/docs/Homestead_Food_Production_Nutrition_HKI.pdf

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency and achievements: Reflections on measurement of women's empowerment. Development of Change, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar]

- Kadiyala, S. , Harris, J. , Headey, D. , Yosef, S. , & Gillespie, S. (2014a). Agriculture and nutrition in India: Mapping evidence to pathways. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1331(1), 43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadiyala, S. , Harris, J. , Headey, D. , Yosef, S. , & Gillespie, S. (2014b). Agriculture and nutrition in India: Mapping evidence to pathways. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1331, 43–56. 10.1111/nyas.12477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, B. , Dahal, D. R. , & Govindasamy, P. (2008). Caste, ethnic and regional identity in Nepal: Further analysis of the 2006 Nepal demographic and health survey. Maryland, USA: Retrieved from Calverton; http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadm638.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Malapit, H. J. L. , Kadiyala, S. , Quisumbing, A. R. , Cunningham, K. , & Tyagi, P. (2015). Women's empowerment mitigates the negative effects of low production diversity on maternal and child nutrition in Nepal. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(8), 1097–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, A. S. , S. R., & Boender, C. (2002). Measuring women's empowerment as a variable in international development. DC: Retrieved from Washington; https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGENDER/Resources/MalhotraSchulerBoender.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Maslak, M. A. (2003). Daughters of the Tharu: Gender, ethnicity, religion, and the education of Nepali girls. ( pp. 108–128). New York, USA: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, J. , Johnson, N. , Kadiyala, S. , Kennedy, G. , & Wyatt, A. J. (2015). Agricultural research for nutrition outcomes—Rethinking the agenda. Food Security, 7(3), 593–607. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, J. , & Popkin, B. M. (1990). Beating the zero‐sum game: Women and nutrition in the third world. Food & Nutrition Bulletin, 12, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty, J. , Nielsen, P. , Pandey, P. , & Sharma, N. (2013). Action against malnutrition through agriculture, final evaluation report. Nepal: Retrieved from Kathmandu; http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00KMDV.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Meinzen‐Dick, R. , Behrman, J. , Menon, P. , & Quisumbing, A. (2012). Gender: A key dimension linking agricultural programs to improved nutrition and health In Reshaping agriculture for nutrition and health (pp. 135–144). International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal Ministry of Health (2016). Demographic and health survey. Nepal: Retrieved from Kathmandu. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal Ministry of Health, New ERA, & ICF . (2016). Nepal demographic and health survey 2016: Key indicators retrieved from Kathmandu, Nepal: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR88/PR88.pdf

- Population Division Ministry of Health and Population. Government of Nepal (2011). Nepal demographic and health survey. Nepal: Retrieved from Kathmandu; http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr257/fr257%5B13april2012%5D.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingaswami, V. , Jonsson, U. , & Rohde, J. (1996). Commentary: The Asian enigma. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/pon96/nuenigma.htm

- Ruel, M. T. , Alderman, H. , & Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group (2013). Nutrition‐sensitive interventions and programmes: How can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? The Lancet, 382(9891), 536–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, S. R. , Hashemi, S. M. , Cullum, A. , & Hassan, M. (1996). The advent of family planning as a social norm in Bangladesh: Women's experiences. Reproductive Health Matters, 4(7), 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. C. , Ramakrishnan, U. , Ndiaye, A. , Haddad, L. , & Martorell, R. (2003). The importance of women's status for child nutrition in developing countries. Retrieved from http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/16526/1/rr030131.pdf

- Strecher, V. J. , McEvoy DeVellis, B. , Becker, M. H. , & Rosenstock, I. M. (1986). The role of self‐efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Education Quarterly, 13(1), 73–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talukder, A. , K. L., Huq, N. , de Pee, S. , Darnton‐Hill, I. , & Bloem, M. W. (2000). Increasing the production and consumption of vitamin A–rich fruits and vegetables: Lessons learned in taking the Bangladesh homestead gardening programme to a national scale. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 21(2). [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, G. (2009). Smallholder farming in transforming economies of Asia and the Pacific: Challenges and opportunities. Italy: Retrieved from Rome; https://www.ifad.org/documents/10180/a194177c-54b7-43d0-a82e-9bad64b76e82 [Google Scholar]

- The Food and Agriculture Organization, The International Fund for Agricultural Development, & The World Food Programme (2015). The state of food insecurity in the world. Italy: Retrieved from Rome; http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4646e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank . (2015). Agriculture & Rural Development. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/topic/agriculture-and-rural-development

- The World Bank , The Food and Agricultura Organization , & The International Fund for Agricultural Development (2008). Gender in agriculture sourcebook. Retrieved from Washington D.C. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGENAGRLIVSOUBOOK/Resources/CompleteBook.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United States Agency for International Development . (2015). SUAAHARA, AID‐367‐A‐11‐00004 . Process Evaluation. Results from Frontline Worker and Household Surveys Retrieved from Washington D.C: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00KWXG.pdf

- Verma, S. C. (2009). Amazing Tharu women: Empowered and in control. Retrieved from http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue22/verma.htm

- World Bank . (2014). World development indicators. Retrieved from Washington D.C: [Google Scholar]

- Yosef, S. , Jones, A. D. , Chakraborty, B. , & Gillespie, S. (2015). Agriculture and nutrition in Bangladesh: Mapping evidence to pathways. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 36(4), 387–404. 10.1177/0379572115609195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]