ABSTRACT

The therapeutic application of human–animal interaction has gained interest recently. One form this interest takes is the use of service dogs as complementary treatment for veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Many reports on the positive effect of PTSD Service Dogs (PSDs) on veterans exist, though most are indirect, anecdotal, or based on self-perceived welfare by veterans. They therefore only give a partial insight into PSD effect. To gain a more complete understanding of whether PSDs can be considered an effective complementary treatment for PTSD, a scoping literature review was performed on available studies of PSDs. The key search words were ‘dog’, ’canine’, ‘veteran’, and ‘PTSD’. This yielded 126 articles, of which 19 matched the inclusion criteria (six empirical studies). Recurrent themes in included articles were identified for discussion of methodology and/or results. It was found that results from most included studies were either applicable to human–animal interaction in general or other types of service animals. They therefore did not represent PSDs specifically. Studies which did discuss PSDs specifically only studied welfare experience in veterans, but used different methodologies. This lead us to conclude there is currently no undisputed empirical evidence that PSDs are an effective complementary treatment for veterans with PTSD other than reports on positive welfare experience. Additionally, the lack of development standardization and knowledge regarding welfare of PSDs creates risks for both human and animal welfare. It is therefore recommended that a study on the effect of PSDs be expanded to include evaluation methods besides self-perceived welfare of assisted humans. Future studies could include evaluations regarding human stress response and functioning, ideally conducted according to validated scientific methodologies using objective measurement techniques to identify the added value and mechanisms of using PSDs to assist treatment of PTSD in humans.

KEYWORDS: Dog, PTSD, canine, veteran, military, intervention, review

HIGHLIGHTS: • There is little empiric evidence on the influence of service dogs for veterans with PTSD. • Lack of evidence limits the application and development of PTSD service dogs. • The influence of service provision on the welfare of service dogs remains to be studied.

La aplicación terapéutica de la interacción humano-animal ha ganado interés en los últimos años. Una forma que toma este interés es el uso de perros de servicio como tratamiento complementario para veteranos con Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático (TEPT). Existen muchos reportes del efecto positivo de los Perros de Servicio en TEPT (PSDs, en su sigla en inglés) en los veteranos, aunque la mayoría son indirectos, anecdóticos o basados en la autopercepción de bienestar de los veteranos. Por lo tanto, sólo entregan una visión parcial sobre el efecto de los PSD. Para obtener una comprensión más completa sobre si los PSDs pueden ser considerados un tratamiento complementario efectivo para el TEPT, se realizó una revisión exploratoria de la literatura de los estudios disponibles de PSDs. Las palabras clave de búsqueda fueron ‘perro’, ‘canino’ ‘veterano’ y ‘TEPT’, lo que arrojó 126 artículos, de los cuales 19 cumplieron los criterios de inclusión (6 estudios empíricos). Los temas recurrentes en los artículos incluidos fueron identificados para discusión de la metodología y/o resultados. Se encontró que los resultados de la mayoría de los estudios incluídos eran aplicables a la interacción humano-animal en general o en otro tipo de animales de servicio. Por lo tanto, no representaban a los PSDs específicamente. Los estudios que discutían acerca de PSDs en forma específica solo estudiaron la experiencia de bienestar en los veteranos, aunque usaron diferentes metodologías entre ellos. Esto lleva a concluir que actualmente no hay evidencia empírica indiscutible de que los PSDs sean un tratamiento complementario efectivo para los veteranos con TEPT más allá de los reportes de una experiencia positiva de bienestar. Adicionalmente, la falta de estandarización del desarrollo y conocimiento acerca del bienestar de los PSDs genera riesgos para el bienestar de ambos, humano y animal. Por lo tanto es recomendable que el estudio del efecto de los PSDs sea ampliado para incluir métodos de evaluación mas allá del bienestar auto-percibido de los humanos asistidos. Estudios futuros podrían incluir evaluaciones en relación a la respuesta al estrés y funcionamiento humanos, idealmente conducidos de acuerdo a metodologías científicas validadas usando técnicas de medición objetivas para identificar el valor agregado, y mecanismos, del uso de PSDs para asistir el tratamiento del TEPT en humanos.

PALABRAS CLAVES: Perro, TEPT, Canino, Veterano, Militar, Intervención, Revisión

人-动物互动的治疗应用在过去几年中引起了人们的兴趣。这种兴趣的一种形式是使用服务犬作为创伤后应激障碍(PTSD)退伍军人的补充治疗。已经有许多PTSD服务犬(PSDs)对退伍军人有积极影响的报道,尽管大多数是间接的,传闻性质的,或者是退伍军人的自我感知获益。因此,它们只能对PSDs的效果给出部分证据。为了更全面地了解PSDs是否可作为创伤后应激障碍的有效补充治疗,我们对PSDs的现有研究进行了范围文献综述(scoping literature review)。使用关键搜索词‘狗’,‘犬类’,‘退伍军人’和‘PTSD’,共得到126篇论文,其中19篇符合纳入标准(6项实证研究)。为了便于讨论方法和/或结果,我们对所纳入文章中反复出现的主题进行了总结。结果发现,大多数纳入研究的结果要么适用于普遍的的人 - 动物互动,要么适用于其他类型的服务性动物。因此,它们没有具体代表PSDs。专门讨论PSDs的研究只研究了退伍军人的获益经验,还使用了不同的方法。最后结论是,目前除了对积极获益经验的报告之外,没有无可争议的实证证据支持,PSDs对于患有PTSD的退伍军人是一种有效的补充治疗方法。此外,PSDs福利发展标准化和相关知识的缺乏会给人类和动物福利带来风险。因此,我们建议扩大对PSDs影响的研究,纳入除了受助人的主观获益之外的其它评估方法。未来的研究在理想情况下可以根据经过验证的科学方法,使用客观测量技术对人类应激反应和功能进行评估,确定利用PSDs协助治疗人类创伤后应激障碍的附加价值和机制。

关键词: 狗, PTSD, 犬类, 老兵, 军队, 干预, 综述

1. Introduction

In The Netherlands, the first reports of dogs employed by the military date back to the First World War. In 1913, dogs were introduced as beasts of burden to pull military carts with weaponry, ammunition, or other equipment; a role they already fulfilled in civilian life. Dogs thus became the third animal species used in the Dutch army, alongside messenger pigeons and horses (Rijnberk, 2012; Smits, 1976). This was not the only role dogs fulfilled during their service, as they also had incidental and unofficial duties. Dogs functioned as unofficial guard animals, alerting soldiers to oncoming intruders, vehicles, or other dangers. More interestingly, dogs were also reported to fulfil the role of emotional companion, social support, or troop mascot to those same soldiers, keeping military morale high under difficult and stressful circumstances in times of war (Lenselink, 1996).

By the end of the Second World War, it seemed that dogs would be phased out of the Dutch military services. This was because both the pigeon and horse had been retired from service and replaced by mechanical inventions like telephones and vehicles (Lenselink, 1996). The dog persisted among the military however, likely helped by the diversity of its application. This followed international development, which saw dogs increasingly used in various tasks within various international military forces.

1.1. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

One such application was the role of the dog as a social or emotional companion. Developing beyond its original role as a troop mascot, the soothing and comforting aspects of human–dog interaction have gained interest in recent years. As a result, therapeutic applications and assisting treatment methods involving dogs are being developed for humans with various disabilities and disorders. One of these disorders is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD is a trauma- and stressor-related disorder caused by the experience of one or multiple traumatic events (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Individuals with PTSD generally suffer from negative mood, periods of depression, periods of anxiety, flashes of anger, reckless behaviour, and sleeplessness (APA, 2013). They are additionally susceptible to drug, alcohol, or tobacco abuse, or to become suicidal (Glintborg & Hansen, 2017; Smith, Goldstein, & Grant, 2016). This leads individuals with PTSD to become disengaged from relationships with others, avoid public places, avoid strangers, and detach themselves from society as a whole (APA, 2013).

1.2. The influence of dogs on PTSD

The use of dogs to help treat PTSD is a form of Animal Assisted Intervention (AAI). This means that interaction with an animal is considered as treatment augmentation within part of a person’s overall treatment plan (Kruger & Serpell, 2006). In veterans diagnosed with PTSD, interaction is often through the assignment of a PTSD Service Dog (PSD). A PSD is a specially bred and selected dog, trained to assist those with PTSD in their daily life (Krause-Parello, Sarni, & Padden, 2016). With its constant presence in the veteran’s life, the PSD is a continuous form of support and/or treatment augmentation for traditional forms of treatment. The PSD might further form a barrier reduction for individuals who are hesitant to undergo conventional treatment methods, or for those who have proven unreceptive to said methods.

The potential benefit of the PSD to veterans with PTSD is supported by a number of studies investigating the effect of human–animal interactions on self-perceived human welfare and quality of life. Positive interactions between humans and dogs, for example, have been proven to increase levels of oxytocin in both humans and dogs (Nagasawa et al., 2015). This has been found to cause a more positive mood, decreased negative emotions, and increased perceived welfare in humans (Beetz, Uvnäs-Moberg, Julius, & Kotrschal, 2012; Yount, Ritchie, St Laurent, Chumley, & Olmert, 2013). Moreover, companion animals act as social facilitators between humans, reducing the risk of social isolation (Banks & Banks, 2002; McNicholas & Collis, 2000; Wood, Giles-Corti, & Bulsara, 2005).

Another important feature of animal companionship is that the animal is largely dependent on the human for exercise, feeding, and grooming. This enables the human to express nurturing and protective behaviours. Activities related to animal care may therefore promote engagement with other individuals, responsibility, and self-efficacy (Tedeschi, Fine, & Helgeson, 2010). This in turn relates to behavioural activation, which has been shown to be an effective treatment for depression in humans (Jakupcak, Wagner, Paulson, Varra, & McFall, 2010; Kruger & Serpell, 2006). Because behavioural activation has also proven effective as treatment for PTSD (Jakupcak et al., 2010), the principles associated with behavioural activation may provide additional evidence of the positive influence human–animal interaction has on human welfare.

The interaction between veterans diagnosed with PTSD and their PSDs are consistent with the above. As stated, the interaction of humans with animals elicits positive emotions and feelings of affection, countering the emotional numbness and negative emotions individuals with PTSD might experience (Marr et al., 2000; O’Haire, 2013). Additionally, individuals with PTSD are often hyper aroused. PSDs may help reduce hyperarousal, because the presence of an animal is known to reduce anxiety (Barker, Pandurangi, & Best, 2003). A specific situation in which this might happen is when someone with PTSD is suffering a flashback of the event(s) that triggered the PTSD. While experiencing such flashbacks, the presence of a dog can help the person to focus on the present, reminding them that the danger is no longer there (Yount et al., 2013) The specialized training of a service dog may further strengthen this association, as it can be trained to actively seek its handler’s attention, strengthening the re-orienting effect.

Lastly, service dogs can be used by veterans with combat-sustained injuries to compensate for physical disabilities (Foreman & Crosson, 2012). Although not the primary function of a PSD, the assistance of a dog for small tasks may help to reduce costs for paid assistance, reduce embarrassment in public settings, and improve independence (Foreman & Crosson, 2012; Winkle, Crowe, & Hendrix, 2012). PSDs can therefore help improve the welfare of their handler by stimulating their engagement with their social and physical surroundings (Winkle et al., 2012).

In short, PTSD is a complex mental disorder, of which the cause and subsequent effect differ between individuals. It can be problematic to diagnose, and the exact number of affected individuals is unclear. Nonetheless, the consequences of PTSD can be severe, adversely affecting the health and welfare of those affected by it and those in their social support network. The provision of a PSD to people with PTSD has received anecdotal support as a new form of treatment augmentation. Veterans themselves have additionally reported the PSD to be a positive intervention. These reports only give a partial insight in PSD effect though, namely individual welfare experience, and do not provide a complete understanding of whether PSDs can be considered an effective complementary treatment for PTSD. They, for example, do not differentiate between PSDs and regular companion animals which, according to earlier described influence of human–animal interaction, can cause an increased experience of positive welfare. Current evidence can furthermore not account for potential report bias, as the presence or absence of a placebo effect is not known. Additional research seems therefore required to identify the effect a PSD has on a person with PTSD and whether the PSD can be regarded as a valid part of PTSD treatment. Before such research is performed, it would be wise to evaluate existing studies on PSD effectiveness and find out which aspects of human–animal interaction are described in them. In this scoping literature review it is therefore questioned which studies have already been performed regarding the effect PSDs have on veterans with PTSD, which aspects of human–animal interaction these studies discussed, and how their methodologies and results compare to one another. From this we hope to conclude whether an additional study of various aspects of the PSD–veteran relationship is needed.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search

This scoping literature review assessed existing and ongoing studies regarding the use of PSDs published up to September 2017. Relevant articles were identified by a computerized search in the following databases: Scopus Search, PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Retrieval and inclusion/exclusion of articles was performed by one researcher. No research protocol was used. The used query in the primary database (Scopus) was ‘Dog OR Canine AND PTSD OR Veteran’ in either the title, abstract, or keywords of an article. Queries in other databases matched these inclusion criteria. The full written spelling of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder were not included in the final search terms because the abbreviation is more commonly used in text. Test queries furthermore showed that these terms yielded only articles which would be excluded under criterion 3 of the following inclusion criteria:

The article was written in English as a primary language;

The article originated from a peer-reviewed journal, or a proposal for such an article;

The article mentions all of the following concepts: veterans, dogs, and PTSD;

The article focused on the influence of dogs on veterans with PTSD as a primary subject, not as part of an overall theme (for example, different AAI methods).

Criterion 1 was included to exclude any article which might not be (fully) interpretable to the authors in its original language. Criterion 2 was included to distinguish between relevant scientific literature concerning PSDs and non-scientific literature like general discussions or narratives. Criterion 3 was included to distinguish between articles discussing the effect of human–animal interaction on human mental welfare, and articles which discussed other aspects of human–animal relationship. Criterion 4 was included in this review to distinguish between articles speaking specifically about PSDs and those who discussed other forms of AAI or AAI as a whole.

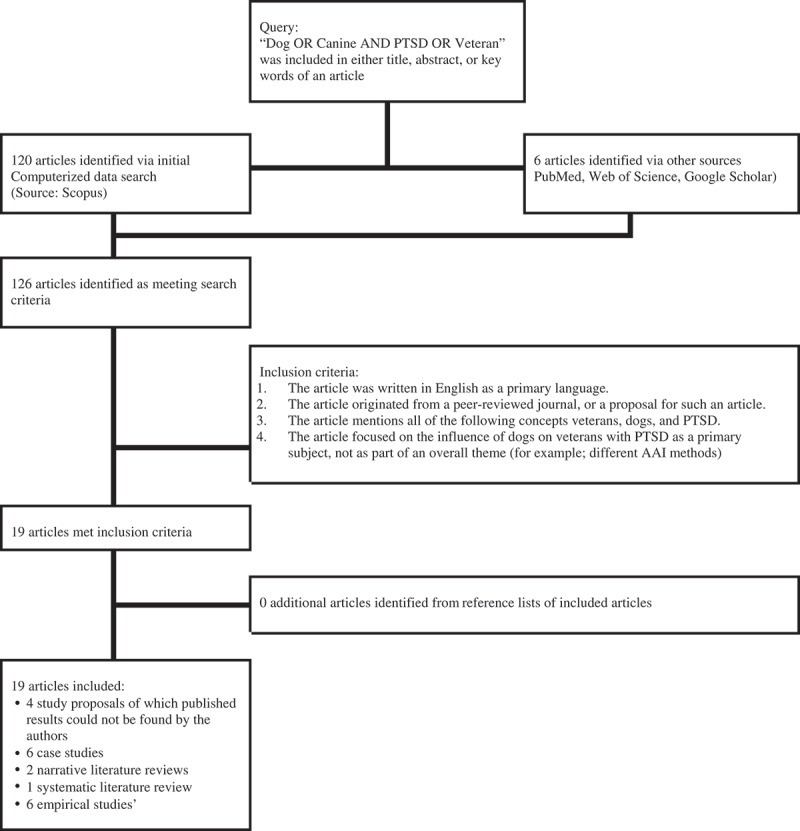

The initial query in the Scopus Search database yielded 120 articles (published up to 29 September 2017), which conformed to the proposed query. Of these 120, two articles were immediately excluded due to being duplicates of another article in the query. A total of 105 articles were subsequently excluded because they did not meet all inclusion criteria. More specifically, all articles met criterion 1, 10 articles did not meet criterion 2, 88 articles did not meet criterion 3, and seven articles did not meet criterion 4. This left 13 articles from the 120 retrieved through the initial database. Six articles matching the inclusion criteria were additionally retrieved from secondary databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar), resulting in a total of 19 articles included. These six additional articles included four study proposals, which were not catalogued by the primary database, and two articles which met all query criteria, yet for unknown reasons were absent from the primary database. No additional articles were identified from reference lists, leaving the final number of included articles at 19. An overview of the above process can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow chart of the literature review. Included are search criteria, inclusion criteria, and number of included articles at each stage. An overview of the 19 included articles can be found in Appendix 1.

Of the 19 included articles, six were case studies, two were narrative literature reviews, one was a systematic literature review, six were empirical studies, and four were study proposals of which published results could not be found by the authors of this review at the time of writing. Despite lacking clear results, these latter studies were included in the review, as they all proposed empirical studies regarding the influence of PSDs on military veterans. The authors therefore deemed the inclusion of these studies necessary for an inclusive discussion regarding developments in the study of PSDs. A complete list of all articles consulted during this review can be found in Appendix 1. Full text reading was subsequently performed to identify different themes and research questions in each article.

2.2. Identified themes

In 2016, Krause-Parello et al. performed a literature review regarding PSDs for veterans. They included peer-reviewed literature on PSDs for veterans published up to October 2015. They identified the following overall themes: definition of a service dog, lack of consensus regarding PSD development, social/physiological benefits of a service dog, cost and availability barriers, and the welfare of service dogs. With the exception of service dog definition, these themes could also be identified in other reviewed papers. Several new themes were additionally identified in the literature published after October 2015. These themes were the expectations veterans have of a service dog (Crowe, Sánchez, Howard, Western, & Barger, 2017; Yarborough et al., 2017), reservations about service dogs (Finley, 2013; Glintborg & Hansen, 2017), the role of the service dog in the overall treatment plan (Furst, 2015; Glintborg & Hansen, 2017), and best practice regarding PSDs (Saunders et al., 2017). These themes are discussed below, with the exception of social/physiological benefits of a service dog as these have already been discussed.

3. Results

3.1. Definition of a service dog

In their review from 2016, Krause-Parello et al. gave the following definition of a service dog: ‘Service dogs (SDs) are considered working dogs. These dogs are exhaustively trained to respond precisely to specific disabilities of their owners and are typically allowed entry into public facilities under the protection of the Americans with Disabilities Act’ (Krause-Parello et al., 2016). By doing this, they combined several earlier statements about service dogs as presented by Taylor, Edwards, and Pooley (2013) into a single statement. This statement seems to be generally accepted in literature as the definition of a service dog, be it not directly quoted. This is possibly because it includes the most important aspects of a service dog, namely, its specialized training, commitment to a single handler, and its legal status. This definition also distinguishes between a service dog and other types of working dogs, such as therapy and emotional support dogs, and nonworking dogs, such as companion dogs. It does not outline the specific duties and tasks of a service dog, as these vary between dogs due to specific handler requirements.

3.2. Reservations about service dogs

The presented definition of a service dog does not outline the specific qualifications and training criteria to which a dog must conform in order to be recognized as an official service dog. In their review on alternative treatment methods for PTSD, Wynn (2015) described this issue as a constraint in AAI as a whole and thus by extension in the use of service dogs. They noted that, although promising, the best practice for using PSDs to facilitate socialization, provide companionship, decrease trauma-related symptoms, and encourage independence had not been established (Wynn, 2015). This hampers the measurement of the effectiveness of these dogs and prevents animal-assisted interventions from achieving their full potential. This statement was taken up by Krause-Parello et al. (2016) in their review, which drew a connection to remarks by Finley (2013). In an earlier study, Finley (2013) stated that the exact cause and effect of service dogs as a complementary treatment for PTSD are not known. Although recognizing that there is anecdotal and self-report support for the effectiveness of PSDs on human welfare, Finley (2013) voiced concerns about the precise tasks of PSDs, as effectiveness for, and reasoning behind, specific tasks were not always known. This concern is shared in the recent literature by Glintborg and Hansen (2017), who noted that certain interventions by a PSD could potentially hamper treatment of PTSD rather than support it. As an example, Glintborg and Hansen (2017) mention the ability of some PSDs to physically block strangers who approach their handler by placing themselves directly in front or behind the handler. This behaviour may provide a sense of safety for the handler and help them to cope with stress experienced from an approaching stranger or being in a public place. It may therefore by extension increase the social interaction of the handler and reduce isolation or detachment from society. Blocking could also be regarded as a negative effect. By blocking strangers from accessing the handler, the dog could indirectly reinforce the view of the handler that strangers pose a threat which needs to be kept at a distance. In this manner, the PSD would hamper the handler’s treatment for PTSD or its symptoms as they are no longer confronted by what causes them stress or discomfort, but avoid it.

Relatively little is known about long-term interaction effects, with Vincent et al. (2017) reporting the longest follow-up of nine months. The precise relationship between the PSD and different aspects of the handler’s welfare, especially in the long term, are therefore unknown. Definitive statements about the concerns of Finley (2013) and Glintborg and Hansen (2017) can therefore not be made at this point. Precise intervention methods and training furthermore differ between service dogs, creating differences between studies and observation groups. PSDs can nowadays be provided by multiple organizations in multiple countries, and are often trained to respond to the specific mannerisms of their handler. This results in a considerable variety between training methods and learned behaviours. Not every dog may perform the same behaviours/interventions for its handler, therefore not having the same effect on aspects of their welfare. This makes conclusive statements on effectiveness even more difficult, or at least not applicable to all PSDs.

This latter problem is in line with concerns voiced by Furst in 2015, who mentioned the growing number of organizations that provide PSDs for veterans in the US and how there was seemingly no governmental intervention, endorsement, funding, or quality control on them. They stated that the effectiveness of PSDs for veterans with PTSD is often justified through study of human–dog emotional interaction or the study of other forms of AAI. However, there was yet to be one standardized, scientifically recognized way to train PSDs or to pair a dog with a veteran with PTSD (Furst, 2015).

3.3. Service dogs and animal welfare

The lack of empirical evidence for, and standardization in, the selection and training of PSDs constitute a potential threat to animal welfare. The primary task of a service dog is to increase the welfare of the person it is assigned to. While a service dog can potentially increase not only the physiological but also the mental and social welfare of its handler, by personal interaction or by facilitating interactions with others, it is not always clear to what extent the improved welfare of the handler comes at the expense of the dog’s welfare. Dogs could be used for work which they are unsuited for, could be exposed to prolonged or unnecessary stress, animals could be unable to regulate the own (social) environment, and animals’ physical degradation with age could go unnoticed (Serpell, Coppinger, Fine, & Peralta, 2006). It can furthermore be asked what is exactly meant by both human and animal welfare, as there are various definitions of welfare. It is therefore not always clear what is meant by ‘good’ and ‘poor’ welfare, and how this difference should be measured. At present, no study seems to have specifically questioned the influence of service provision on the welfare of a PSD, or how good welfare should be defined in this specific group of animals. There is currently no single definition of welfare or welfare standard for PSDs, which makes it difficult to monitor their welfare.

3.4. The role of the service dog in the treatment plan

Glintborg and Hansen (2017) questioned the role of a PSD in the overall PTSD treatment plan of its handler. In a single case study, they determined that there were multiple obstacles to the integration of PSDs into existing treatment plans. Main issues were a lack of communication and collaboration between healthcare professionals, combined with a perceived lack of knowledge of the function of the PSD. As an example, it was recalled that a healthcare provider had shown interest in the PSD, yet did not actively involve it in therapy sessions. Although this could have been inherent to the therapy given at the time, it could also have been a lack of knowledge on the part of the healthcare provider. The authors did not question which explanation was applicable though, leaving the mechanisms behind the above example ambiguous. Nonetheless, there is the perception that healthcare providers are lacking knowledge of the potential of PSDs. Whether this perception is correct remains to be established. How this perceived lack should be countered also remains unclear. Healthcare providers or their educators may be rightfully hesitant to accept available anecdotal and self-report evidence as definitive proof of the effectiveness of PSDs, out of fear of potentially harming patients with non-evidence-based treatment methods. This observation would be in line with concerns voiced by Owen, Finton, Gibbons, and DeLeon (2016), when they addressed nurse practitioners about the potential of PSDs in treating PTSD. They argued that although empirical evidence of the PSD effect was still lacking, PSDs and AAI are a promising field of PTSD treatment. They therefore urged nurse practitioners and health policy experts to see PSDs and AAI as a potential form of complementary treatment for PTSD and disorders arising from combat experience, especially considering the growing prevalence in the US.

3.5. What to expect from a service dog

Among the reviewed literature, two studies specifically questioned the expectations and requests veterans might have of service dogs. Yarborough et al. (2017) questioned a total of 78 veterans with PTSD about their expectations of, and needs for, a PSD. Of the respondents, 24 already had a service dog while 54 were on a waiting list to receive one. An additional 22 veterans received a dog during the study, resulting in a final total of 46 veterans with a dog at the end of the study and 30 still waiting to receive one. The most important feature of a PSD, as reported by the veterans who had one, was its behaviours towards its handler. Specifically appreciated were the dogs attention seeking behaviours such as licking or nudging the veterans. It was reported that these behaviours helped the veterans ‘to remain focused on the present’ (Yarborough et al., 2017) and thus helped them take their mind off negative thoughts, emotions, or memories they might be experiencing. This was combined with the ability of the dog to function as a physical barrier between the veteran and strangers, reducing the stress or arousal the veteran experienced from such encounters (Yarborough et al., 2017). Overall, the dog was thus considered as a calming catalyst of the veterans mental/emotional state in potentially stressful situations, and therefore improved the veteran’s experienced welfare.

The other study which questioned the needs and expectations veterans have of a service dog was Crowe et al. from 2017. In their study, they questioned nine veterans with PTSD about the most appreciated feature of their PSDs. The veterans appreciated that the dog was a facilitator of behaviour and experiences, helping its handler to reconnect with society, opening opportunities in daily life, facilitating social contact, and reclaiming life/sense of worth. Again, the overall theme herein was the function of the dog as a calming catalyst in stressful situations, and its ability to alert its handler to the development of stress or panic (Crowe et al., 2017). Because this conclusion is similar to that of Yarborough et al. (2017), this would seem to be the most appreciated feature of PSDs. This is consistent with the purpose for which a PSD is mostly provided, as they are not meant to act fully autonomously. Instead, PSDs are meant to facilitate insight into the handler’s own behaviours and emotions to help them manage said emotions or behaviours. As found by Yarborough et al. (2017), it was also appreciated if the dog creates space for this reflection.

3.6. Best practice for PSD study

The lack of empirical evidence regarding the effectiveness of PSDs seems to be caused by a lack of consensus on best practice or standardized methodology for the study type. Saunders et al. addressed this issue in 2017, as they spoke about recommended methodology and study constraints regarding PSDs. They referred to the same discussion currently taking place in literature regarding AAI in general, and mentioned recommendations to improve best practice. Kamioka et al. (2014) and Stern and Chur-Hansen (2013), for example, have made multiple recommendations to improve study design regarding AAI, such as careful description of methodology to improve replication. They also expressed concern about a trend to only use one group of animals, one data point, one measurement method, or one provider of animals in the study of AAI, an observation which seems applicable to the study of PSDs as well.

The use of only one source of information makes found results less relevant to the population of AAI or PSDs as a whole, and also reduces reproducibility of studies between subject groups. Looking at the studies discussed in this review, however, the use of singular information sources might be a necessity in PSD study as developed PSDs are often incomparable between different providers. Using more than one would cause additional variation to appear, complicating the formation of methodology and result. Using only one information source still has its constraints though as, in addition to those mentioned above, it limits the number of PSDs and handlers which can be studied at one time. This was noted by Herzog in 2014 when they observed that studies on AAI generally had inadequate sample sizes to properly measure effect, a lack of randomization, and no control group among research subjects. Looking at current literature regarding PSDs, this statement holds true, as many studies on the effectiveness of PSDs show small sample sizes, a lack of control group, and no true randomization of research subjects. Some mention this lack as a constraint in their reporting, and Kloep, Hunter, and Kertz (2017) even names it as inherent to the research type. These factors are often absent because studies of PSDs necessarily depend on the availability of subjects with established PTSD, their willingness to participate, and the availability of service dogs. Some studies have attempted to account for this lack of standardization by using the natural variation within the available population to their benefit. This was done by comparing people waiting for a PSD (Yarborough et al., 2017) or people with an emotional support dog (Saunders et al., 2017) to people who had received a PSD. Others have opted to assume a baseline model (Vincent et al., 2017), in which change is measured within an individual rather than between treatment and control groups to reduce variation.

The above-mentioned methods still cannot account for all possible variation, however, as it cannot be excluded that factors such as habituation with measurement method, will to please the researchers, or placebo effect could have affected findings. Findings of positive PSD effects in the studies by Stern et al. (2013), Kloep et al. (2017), Vincent et al. (2017), and Yarborough et al. (2017) are furthermore solely based on self-perceived welfare of assisted humans which, though an important measurement tool, is poorly reproducible, poorly translatable to different study groups, and poorly comparable between different studies. Among the 19 studies included in this review, only six provided observational evidence of the effect of PSDs on the impact of PTSD between groups or within an individual over time. Four of these studies (Kloep et al., 2017; Stern et al., 2013; Vincent et al., 2017; Yarborough et al., 2017) used multiple questionnaires among veterans to do so, one used interviews, and one used media response analysis. The four questionnaire-based studies made use of a total of 19 questionnaires (Table 1). Of these 19, only two were used more than once. These were the Beck Depression Index (BDI-II) and the PTSD checklist (PCL; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993). The BDI-II was used in two studies and the PCL was used in all four. The PCL unfortunately has three different versions; civilian, military, and (event) specific. All three were used between the reviewed studies. This complicated comparison of results, as similarity of answer models could not be assumed. Additionally, measurements were performed in different time frames. Because of this, data similarity could not be assumed and comprehensive meta-analysis of the PCL scores reported by the four studies could not be performed. Finally, data pooling for various questionnaires measuring similar parameters was considered. This was also deemed not possible, due to the same reasons.

Table 1.

The following are questionnaires used in either one or multiple of the six identified observational studies (Appendix 1).

| Questionnaire | Study | Measures |

|---|---|---|

| PTSD Checklist, Specific (PCL-S) | Kloep et al., 2017 | PTSD. Situation specific |

| PTSD Checklist, Military (PCL-M) | Vincent et al., 2017 Stern et al., 2013 |

PTSD. Military specific |

| PTSD Checklist, Civilian (PCL-C) | Yarborough et al., 2017 | PTSD. Civilian specific |

| Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS) | Kloep et al., 2017 | Depression |

| Post deployment Social Support Scale (PSSS) | Kloep et al., 2017 | Social support after deployment |

| Quality Of Life Scale (QOLS) | Kloep et al., 2017 | Quality of life |

| Dimensions of Anger Reactions Scale-5 (DAR-5) | Kloep et al., 2017 | Anger |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | Vincent et al., 2017 | Sleep quality |

| Beck Depression Index (BDI-II) | Stern et al., 2013 Vincent et al., 2017 |

Depression |

| World Health Organization Quality Of Life (WHOQOL BREF) | Vincent et al., 2017 | Quality of life (physical, psychological, social, environmental health) |

| Life Space Assessment (LSA) | Vincent et al., 2017 | Mobility |

| Veterans Rand 12-item Health Survey (VR-12) | Yarborough et al., 2017 | Physical and mental health |

| Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI) | Yarborough et al., 2017 | PTSD. Military specific |

| Behaviour and Symptom Identification scale (BASIS-24) | Yarborough et al., 2017 | Depression, social interaction, emotional state, psychosis, substance abuse |

| Wisconsin quality of life index | Yarborough et al., 2017 | Quality of life measurement tool |

| Activity level | Yarborough et al., 2017 | Activity |

| General social survey | Yarborough et al., 2017 | General happiness index |

| Short form survey instrument (SF-36) | Stern et al., 2013 | Patient health |

| Lexington attachment to pet scale | Stern et al., 2013 | Attachment to pets |

4. Conclusion

This review demonstrated that there is relatively little empiric evidence available which supports the effectiveness of PSDs in the treatment of PTSD symptoms. Although it has been found that PSDs can positively influence perceived welfare and quality of life of those with PTSD (Kloep et al., 2017; Stern et al., 2013; Vincent et al., 2017; Yarborough et al., 2017), this evidence is mostly based on anecdotal reports and subject self-report, making validity disputable. It does not explain to what extent the observed effect is influenced by the actual trained behaviour of the PSD, and to what extent by the inherent effects of human–animal interaction. Placebo effect is similarly unaccounted for, and it is possible that respondents gave socially desirable answers when studied. In addition to this, many studies only monitored the effect of PSDs on the symptoms of PTSD over a short time span, making long-term effects largely unknown. In conclusion, the current constraints and differences between the design and methodology of available studies hamper comparison, verification, and reproduction of results concerning the effectiveness of PSDs as a complementary treatment for PTSD.

As a consequence of limited evidence on working mechanisms, there is still discussion about what the specific tasks of PSDs are or should be, and to what extent PSDs benefit the welfare of individuals with PTSD. This is also caused by the lack of standardization in the development of PSDs, as there is no uniform methodology to do so. Although similarities exist, and a general definition seems to be maintained, different criteria are used between organizations to select and train potential PSDs. These differences lead to methodology currently being incomparable between providers and may affect the eventual effect PSDs have on individuals with PTSD.

This leads us to conclude that, despite considerable anecdotal and indirect evidence, there is currently a lack of empirical evidence for the effectiveness of PSDs for veterans with PTSD. Definitive placement and integration of PSDs in existing treatment plans is therefore quite problematic as the cause and effect relation currently observed in PSD–human interaction is insufficiently validated. Lastly, the potential consequences of service provision to the welfare of the PSD itself remain to be studied. It is therefore recommended that a study on the effect of PSDs be expanded to include evaluation methods besides self-perceived welfare of assisted humans. Future studies could include evaluations regarding human stress response and functioning, ideally conducted according to validated scientific methodologies using objective measurement techniques to identify the added value, and mechanisms, of using PSDs to assist treatment of PTSD in humans. It is finally desirable that the training of PSDs becomes more standardized, to provide future studies with more participants and to make study results relevant to a wider range of individuals.

Appendix 1. Literature overview

| Authors | Year | Country | Study type | Purpose | N | Subject | Method | Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crowe et al. | 2017 | US | Observational study | Gathering the opinions about service dogs of veterans with a history of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and/or traumatic brain injury | N = 9 | Veterans with PTSD | Interview and focus group | - |

| Glintborg& Hansen | 2017 | Denmark | Case study | How do medical professionals react to the inclusion of a service dog in a PTSD treatment programme | N = 1 | Person with PTSD | Interviews | - |

| Kloep et al. | 2017 | US | Observational study | Investigate the effects of a new programme for people with PTSD |

N = 7 N = 5 |

Veterans with PTSD | PCL-S, QIDS, PSSS, DAR-5, QOLS | 1 month before treatment (baseline), at the start of treatment, each week during treatment (3x), 1 month after treatment, 6 months after treatment |

| Saunders et al. | 2017 | US | Study proposal | Difference between provision of service dogs and emotional support dogs to veterans with PTSD | N.A. | Veterans with PTSD | Assigned a service or support dog. WHO-DAS II, VR-12, physical component score, mental component score, PCL-5, PSQI, PHQ-9, DAR, WPAI:GHP, C-SSRS |

18 months observation; Check-ups at 1 & 2 weeks, 1 & 2 months; Study appointment at 3, 9, 15 months; Home visit at 6, 12, 18 months |

| Scotland-Coogan et al. | 2017 | US | Study proposal | Investigate veterans experiences during a training programme with PTSD Service Dogs and programme effect | N.A. | Veterans with PTSD | - | - |

| Vincent et al. | 2017 | Canada | Observational study | Evaluate the effectiveness of PTSD Service Dogs for veterans with PTSD | N = 15 | Veterans with PTSD, on a service dog waiting list |

PSQI, PCL-M, BDI-II, WHOQOL BREF, LSA | 6,3,0 months before receiving a service dog; 3 months after receiving a service dog |

| Yarborough et al. | 2017 | US | Observational study | Examining needs related to PTSD, service dogs, and feasibility of data collection |

N = 54 N = 24 N = 22 |

Veterans with PTSD | VR-12, DRRI, BASIS-24, PCL-C, Activity meter, WQOLI, GSS | 1 measurement |

| Krause-Parello | 2016 | US | Systematic literature review | To examine the current knowledge of canine assistance for veterans diagnosed with PTSD to synthesize current empirical knowledge on the subject | N = 6 | Peer reviewed subject specific articles published up to October 2015. | Review | - |

| Owen | 2016 | US | Narrative literature review | Describing recent developments in integrating specialty trained dogs in military veterans’ health care | - | Integration of the PTSD Service Dog in existing PTSD treatment programmes | Narrative | - |

| Furst | 2015 | US | Case study | Discussing the way in which society treats military veterans with PTSD and how treatment could influence them | −. | Role of society and healthcare in treating those with PTSD | Narrative | - |

| Weinmeyer | 2015 | US | Case study | Outline the difficulties surrounding the provision of PTSD Service Dogs to those with PTSD | - | Political struggle surrounding the provision of PTSD Service Dogs | Narrative | - |

| Gillett & Weldrick | 2014 | Canada | Study proposal | The use of canine-assisted interventions for veterans diagnosed with PTSD | -N.A. | Military veterans with PTSD | Three levels of analysis: biological, physiological, social. Assessment per level (medical records, assessment tools for mental health, in-depth interviews) |

- |

| Yount et al. | 2013 | US | Review and case study | Discussing the potential of the PTSD Service Dog in reducing the negative influence of PTSD in military veterans | - | - | Narrative | - |

| Stern et al. | 2013 | US | Observational study | Investigate the comforting and supporting effect the presence of an animal (dog) on individuals with PTSD | N = 30 | Military veterans with PTSD having benefitted from living with a dog (companion/pet dog) | PCL-M, BDI-II, SF-36, Dog information sheet, Dog relationship questionnaire, Lexington attachment to pets scale | 1 measurement |

| Taylor et al. | 2013 | Australia | Observational study | Provide insights into the post-war dog–owner relationship experiences of contemporary veterans |

N = 19 N = 81 |

Media accounts of veterans with PTSD and public comments | Triangulated three phase content analysis | - |

| Finley | 2013 | US | Narrative literature review | How do authorities on veteran affairs respond to new treatments for veterans with PTSD? | - | PTSD Service Dogs | Review | - |

| Krol | 2012 | US | Case study | The history, philosophy, and methodology behind America’s VetDogs program | - | America’s VetDogs program | Review | - |

| Yount et al. | 2012 | US | Case study | The history, philosophy, and methodology behind the Warrior Canine Connection (WCC) | - | Warrior Canine Connection | Review | - |

| Love & Esnayra | 2009 | US | Study proposal | - | N.A. | Soldiers returning to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC) | Behavioural assessments of general mental health and PTSD symptom manifestations, biological markers associated with anxiety/stress/depression | - |

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Stichting Karel Doorman Fonds; Utrecht University Fund; Triodos Foundation; Royal Canin Nederland.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this study would like to thank everyone who contributed to the realization of this review. Special thanks go out to the employees of the Department of Animals in Science and Society department of Utrecht University for providing expertise and advise in various stages of this review.

Disclosure statement

This literature study was performed at Utrecht University as part of a larger research to the influence of PTSD Service Dogs on military veterans with PTSD in The Netherlands. The overall project is performed with support of Stichting Hulphond Nederland and the Dutch Ministry of Defence, with financial support of the Karel Doorman Fund, the Utrecht University Fund, Royal Canin, and the Triodos Foundation. None of these stakeholders were part of the conception of this review. The authors therefore report that there were no conflicting interests involved in the conception of this review, and that they did not gain any direct commercial, financial, or political benefit from this publication.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, TX, USA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Banks M. R., & Banks W. A. (2002). The effects of animal-assisted therapy on loneliness in an elderly population in long-term care facilities. The journals of gerontology series A. Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 57, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker S. B., Pandurangi A. K., & Best A. M. (2003). Effects of animal-assisted therapy on patients’ anxiety, fear, and depression before ECT. Journal of ECT, 19, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beetz A., Uvnäs-Moberg K., Julius H., & Kotrschal K. (2012). Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human–animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe T. K., Sánchez V., Howard A., Western B., & Barger S. (2017). Veterans transitioning from Isolation to Integration: A look at veteran/service dog partnerships. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley E. P. (2013). Empowering veterans with PTSD in the recovery era: Advancing dialogue and integrating services. Annals of Anthropological Practice, 37(2), 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman K., & Crosson C. (2012). Canines for combat veterans: The national education for assistance dog services. US Army Medical Department Journal April–June, 61–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furst G. (2015). Prisoners, pups, and PTSD: The grass roots response to veterans with PTSD. Contemporary Justice Review, 18(4), 449–466. [Google Scholar]

- Glintborg C., & Hansen T. G. (2017). How are service dogs for adults with post traumatic stress disorder integrated with rehabilitation in denmark? A case study. Animals, 7(5), 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog H. (2014, November). Does animal-assisted therapy really work. What clinical trials reveal about the effectiveness of four-legged therapists [Available online at psychology today, blogpost, animas and us]. Last accessed: 02 October 2017 Retrieved from www.psychologytoday.com/blog/animals-and-us/201411/does-animal-assisted-therapy-really-work

- Jakupcak M., Wagner A., Paulson A., Varra A., & McFall M. (2010). Behavioral activation as a primary care-based treatment for PTSD and depression among returning veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23, 491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamioka H., Okada S., Tsutani K., Park H., Okuizumi H., Handa S., … Mutoh Y. (2014). Effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 22(2), 371–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloep M. L., Hunter R. H., & Kertz S. J. (2017). Examining the effects of a novel training program and use of psychiatric service dogs for military-related PTSD and associated symptoms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(4), 425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Parello C. A., Sarni S., & Padden E. (2016). Military veterans and canine assistance for post-traumatic stress disorder: A narrative review of the literature. Nurse Education Today, 47, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger K. A., & Serpell J. A. (2006). Animal-assisted interventions in mental health: Definitions and theoretical foundations In Fine A. H. (Ed.), Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice (2nd ed., pp. 21–38). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Lenselink J. (1996). De berichtenhond in het nederlandse Leger: Een bescheiden experiment. Armamentaria, 31, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marr C. A., French L., Thompson D., Drum L., Greening G., & Mormon J. (2000). Animal-assisted therapy in psychiatric rehabilitation. Anthrozoos, 13, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas J., & Collis G. M. (2000). Dogs as catalysts for social interaction: Robustness of the effect. British Journal of Psychology, 91, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa M., Mitsui S., En S., Ohtani N., Ohta M., Sakuma Y., … Kikusui T. (2015). Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human–dog bonds. Science, 348(6232), 333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Haire M. E. (2013). Animal-assisted intervention for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1606–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen R. P., Finton B. J., Gibbons S. W., & DeLeon P. H. (2016). Canine-assisted adjunct therapy in the military: An intriguing alternative modality. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 12(2), 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Rijnberk A. (2012). Honden in nederlandse krijgsdienst - I. Mitrailleurtractie. Argos, 7, 224–241. Series 5. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders G. H., Biswas K., Serpi T., McGovern S., Grour S., Stock E. M., … Fallon M. T. (2017). Design and challenges for a randomized, multi-site clinical trial comparing the use of service dogs and Emotional support dogs in Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Contemporary Clinical Trials, 62, 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell J. A., Coppinger R., Fine A. H., & Peralta J. M. (2006). Welfare considerations in therapy and assistance animals In Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice (2nd ed., pp. 481–502). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M., Goldstein R. B., & Grant B. F. (2016). The association between post-traumatic stress disorder and lifetime DSM-5 psychiatric disorders among veterans: Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey On Alcohol And Related Conditions-III (NESARCIII). Journal of Psychiatric Research, 82, 16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits F. J. H. T. (1976). Hondentractie in het Nederlandse leger. Armamentaria, 11, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Stern C., & Chur-Hansen A. (2013). Methodological considerations in designing and evaluating animal-assisted interventions. Animals, 3(1), 127–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern S. L., Donahue D. A., Allison S., Hatch J. P., Lancaster C. L., Benson T. A., … Peterson A. L. (2013). Potential benefits of canine companionship for military veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Society & Animals, 21(6), 568–581. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. F., Edwards M. E., & Pooley J. A. (2013). “Nudging them back to reality”: Toward a growing public acceptance of the role dogs fulfill in ameliorating contemporary veterans’ PTSD symptoms. Anthrozoös, 26(4), 593–611. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi P., Fine A. H., & Helgeson J. I. (2010). Assistance animals: Their evolving role in psychiatric service applications In Handbook on animal-assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice (3rd ed., pp. 421–438). New York, NY: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent C., Belleville G., Gagnon D. H., Dumont F., Auger E., Lavoie V., … Lessart G. (2017). Effectiveness of service dogs for veterans with PTSD: Preliminary Outcomes. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 242, 130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F. W., Litz B., Herman D., Huska J., & Keane T. (1993, November October). The PTSD checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies , San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Winkle M., Crowe T. K., & Hendrix I. (2012). Service dogs and people with physical disabilities partnerships: A systematic review. Occupational Therapy International, 19, 54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood L., Giles-Corti B., & Bulsara M. (2005). The pet connection. Pets as a Conduit for Social Capital? Social Science & Medicine, 61, 1159–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn G. H. (2015). Complementary and alternative medicine approaches in the treatment of PTSD. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(8), 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarborough B. J. H., Owen-Smith A. A., Stumbo S. P., Yarborough M. T., Perrin N. A., & Green C. A. (2017). An observational study of service dogs for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services, 68, 730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yount R., Ritchie E. C., St Laurent M., Chumley P., & Olmert M. D. (2013). The role of service dog training in the treatment of combat-related PTSD. Psychiatric Annals, 43(6), 292–295. [Google Scholar]

- Yount R. A, Olmert M. D, & Lee M. R. (2012). Service dog training program for treatment of posttraumatic stress in service members. US Army Medical Department Journal, April–June, 63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]