Abstract

Neuroimaging studies described brain structural changes that comprise the mechanisms underlying individual differences in migraine development and maintenance. However, whether such interindividual variability in migraine was observed in a pretreatment scan is a predisposition for subsequent hypoalgesia to placebo treatment that remains largely unclear. Using T1‐weighted imaging, we investigated this issue in 50 healthy controls (HC) and 196 patients with migraine without aura (MO). An 8‐week double‐blinded, randomized, placebo‐controlled acupuncture was used, and we only focused on the data from the sham acupuncture group. Eighty patients participated in an 8‐weeks sham acupuncture treatment, and were subdivided (50% change in migraine days from baseline) into recovering (MOr) and persisting (MOp) patients. Optimized voxel‐based morphometry (VBM) and functional connectivity analysis were performed to evaluate brain structural and functional changes. At baseline, MOp and MOr had similar migraine activity, anxiety and depression; reduced migraine days were accompanied by decreased anxiety in MOr. In our findings, the MOr group showed a smaller volume in the left medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and decreased mPFC‐related functional connectivity was found in the default mode network. Additionally, the reduction in migraine days after placebo treatment was significantly associated with the baseline gray matter volume of the mPFC which could also predict post‐treatment groups with high accuracy. It indicated that individual differences for the brain structure in the pain modulatory system at baseline served as a substrate on how an individual facilitated or diminished hypoalgesia responses to placebo treatment in migraineurs. Hum Brain Mapp 38:4386–4397, 2017. © 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: interindividual variability, migraine, placebo hypoalgesia, sham acupuncture

INTRODUCTION

Placebo effects are a powerful illustration of a learning phenomenon that can produce treatment outcome via verbally‐induced expectations and cued and contextual conditioning [Colloca and Benedetti, 2009; Eippert et al., 2009], which are mediated by a direct engagement of the brain in processing cognitive inputs [Büchel et al., 2014]. Animal and human studies pointed out the important role of the endogenous opiate system and dopaminergic‐reward circuitry in placebo hypoalgesia [Benedetti et al., 2005; Zubieta et al., 2005]. The individual differences in these systems may be directly related to individual variations in the biological effects of placebo hypoalgesia [Scott et al., 2007]. However, such interindividual variability in clinical populations is less clearly understood. Unexplained differences of placebo hypoalgesia in chronic pain patients make it challenging to develop more efficient clinical trials and capitalize placebo responses in clinical outcomes.

Migraine as a common and disabling condition characterized by recurrent moderate to severe headaches has been an important healthcare and social problem for its great influence on the quality of life [Borsook et al., 2012]. The effects of placebo treatment in migraine studies vary considerably in randomized controlled trials [Diener, 2009; Kong et al., 2013], which may be partly due to interindividual variability in pain relief with placebo treatment [Klaus et al., 2005]. Since most existing studies focused on individual differences in placebo responses, specifically in response only in healthy subjects [Lu et al., 2010; Kong et al., 2009; Watson et al., 2009], very little is known about the placebo mechanisms in migraine and even the brain responses underlying individual differences in psychologically induced hypoalgesia.

Recently, three studies have shown that baseline brain activity and functional connectivity provided a priori prediction of placebo hypoalgesia in chronic pain patients [Craggs et al., 2008; Hashmi et al., 2012; Javeria Ali et al., 2014]. Hashmi et al. [2012] found that baseline brain functional connections between placebo task‐activated regions predicted future placebo responses in a clinical trial in chronic back pain patients [Hashmi et al., 2012]. By using verbal suggestion and heat pain conditioning to enhance positive expectations for analgesic effects of acupuncture treatment, Hashmi et al. found that more efficient network topology in the resting network showed greater psychologically conditioned analgesic responses in chronic knee osteoarthritis pain patients [Javeria Ali et al., 2014]. However, chronic pain alters brain circuitry and induces maladaptive brain structural plasticity distinct in patients with different pain conditions [Baliki et al., 2011]. It is quite possible that brain response patterns for placebo hypoalgesia in migraine differ from other chronic pain conditions. Further investigations into the predictive role of brain structure and function to placebo response in migraine are warranted.

In this study, we used three‐dimensional T1‐weighted and resting fMRI imaging to investigate the brain structural and functional changes for migraine attacks between MO and matched healthy controls (HC), and we hypothesized that interindividual variability in the migraine brain could predict placebo hypoalgesia before starting clinical treatment. To test our hypothesis, verbal suggestion and heat pain conditioning were applied to build positive expectations for hypoalgesia effects of acupuncture treatment [Javeria Ali et al., 2014], and all patients then underwent 8‐week sham acupuncture treatment. Responders in preventive migraine were defined as patients with a reduction in migraine days of at least 50% [Linde et al., 2016; Tfelt‐Hansen et al., 2012].

METHODS

All research procedures were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of the Medical College in Xi'an Jiaotong University and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Inclusion criteria for the migraine patient group were according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition (beta version) (2013): (1) migraine attacks last 4 to 72 h (untreated or unsuccessfully treated); (2) featuring at least two of the following characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate to severe pain intensity and aggravation by causing avoidance of routine physical activity; and (3) there is nausea and/or vomiting, or photophobia and phonophobia during migraine. Exclusion criteria were: (1) any physical illness such as a brain tumors, hepatitis, or epilepsy as assessed according to clinical evaluations and medical records; (2) existence of other comorbid pain chronic conditions (e.g.: tension type headache, fibromyalgia, etc.); (3) existence of a neurological disease or psychiatric disorder; (4) pregnancy or menstrual period; (5) use of prescription medications within the last month; (6) alcohol, nicotine or drug abuse; and (7) claustrophobia.

A total of 196 MO patients were recruited from Xi'an Jiaotong University for the study of acupuncture hypoalgesia. All patients were right‐handed college students and naive to acupuncture treatment. Fifty, education‐ and gender‐matched, healthy, right‐handed HC were recruited. The controls neither had any headache days per year nor had family members who suffered regularly from migraine or other headaches.

Acupuncture Treatment

Acupuncture, as a traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of many pain conditions, is widely used for preventing migraine attack although its effectiveness has not yet been fully understood [Klaus et al., 2005; Melchart et al., 1999]. Because of the elaborate and impressive treatment rituals of acupuncture, patients may have greater expectation and inextricable placebo responses to the treatments [Diederich and Goetz, 2008; Pollo et al., 2001; Zubieta and Stohler, 2009].

In our study, verbal suggestion and heat pain conditioning were used to build positive expectations for hypoalgesia effects of acupuncture treatment [Javeria Ali et al., 2014]. All patients were told that this was a study about the effectiveness of acupuncture analgesia for pain and they would receive traditional acupuncture. Patients were psychologically conditioned to believe that if they were good acupuncture responders in a later heat pain test, they were also good responders for migraine treatment. In fact, all patients received sham acupuncture. By secretly reducing pain stimuli, we built up positive expectations for hypoalgesia effects of acupuncture treatment (see Supporting Information).

After applying verbal suggestion and heat pain conditioning, all patients were randomly assigned into the traditional acupuncture group and sham acupuncture group for 8‐week acupuncture treatment. Patients were blinded to which treatment they received. The duration of the study per patient was 16 weeks: 4 weeks before the MRI scan or at baseline; after 8 weeks of treatment; and 4 weeks after the follow‐up. During the 4 weeks before the MRI scans and after the acupuncture treatment, patients carefully rated the average pain intensity of the attacks (0–10 scale, 10 being the most intense pain imaginable), migraine days (days/month), and migraine attack duration (hours). The Zung self‐rating anxiety scale (SAS) and Zung self‐rating depression scale (SDS) were used to quantify anxiety/depression‐related symptoms of the patients.

Eight weeks of acupuncture treatment consisted of twenty‐four 30‐min sessions (three sessions per week), which followed a similar experimental model in Linde et al.'s [2005] study [Linde et al., 2005]. Specifically, all patients were treated bilaterally at what are called basic points, including gallbladder 20, 40, or 41 or 42, Du Mai governing vessel 20, liver 3, San Jiao 3 or 5, and extra point Taiyang [Linde et al., 2005]. Sham acupuncture was performed by using Streitberger needles [Streitberger and Kleinhenz, 1998] at nonacupoints located near real acupoints (approximately 2–3 cm laterally). The blunt Streitberger needle is retracted into its sheath when pressed against the skin surface, which has been well validated as a sham acupuncture device [Streitberger and Kleinhenz, 1998]. “De‐qi” or needling sensation, is the constellation of sensations a person feels during acupuncture needle manipulation, which is considered to be closely related to clinical efficacy in traditional Chinese medicine [Hui et al., 2005]. In our study, de‐qi was avoided in all 24 sessions of sham acupuncture treatment. After 8 weeks of acupuncture treatment, the success of blinding was tested by using a credibility questionnaire: “When you volunteered for the trial, you were informed that you had an equal chance of receiving traditional acupuncture or sham acupuncture. Which acupuncture do you think you received?”

The drugs used for the prophylaxis of migraine were stopped 4 weeks before the experiment; however, the patients were allowed to take pirprofen when their migraine was difficult to endure. Detailed information about the patients' drug intake was recorded. MO patients were subdivided (50% change in migraine days from baseline) into recovering (MOr) and persisting (MOp) patients after the whole experiment.

In the current study, we focused on the data from the sham acupuncture group (n = 98) to investigate the placebo hypoalgesia in migraineurs.

Imaging Acquisition

Before 8 weeks of acupuncture treatment, migraine subjects were imaged interictally and not within 72 h before or after an attack.

This experiment was carried out in a 3.0‐T Signa GE scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) with an eight‐channel phase array head coil at the Huaxi MR Research Center in Sichuan, China. For each subject, a high‐resolution structural image was acquired by using a three‐dimensional MRI sequence with a voxel size of 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 using an axial fast spoiled gradient recalled sequence (FSGPR) with the following parameters: repetition time = 1,900 ms; echo time = 2.26 ms; data matrix = 256 × 256; field of view = 256 × 256 mm2.

Functional images were obtained by means of a T2*‐weighted single‐shot gradient‐echo‐planar‐imaging sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (msec)/echo time (msec), 2,000/25; flip angle, 90°; 30 continuous slices with a slice thickness = 5 mm; data matrix, 64 × 64; field of view, 240 × 240 mm2; and voxel size, 3.75 × 3.75 × 5 mm3. For each subject, a total of 205 volumes were acquired resulting in a total scan time of 410 s. Subjects were instructed to rest with their eyes closed, not to think about anything in particular, and not to fall asleep. After the scan, the subjects were asked whether they remained awake during the whole procedure.

VBM Analysis

All subjects' structural images were examined by two professional radiologists to exclude the possibility of clinically silent lesions. Structural data were analyzed with the FSL‐VBM protocol in the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) 4.1 software (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). Specifically, the brain extracting tool was first used to extract brain areas from all T1 images [Smith, 2002]. Second, tissue‐type segmentation was carried out using FMRIB's automated segmentation tool V4.1 [Zhang et al., 2001]. The resulting gray matter (GM) partial volume images were then aligned to MNI152 standard space using FMRIB's linear image registration tool [Jenkinson et al., 2002; Jenkinson and Smith, 2001], followed by nonlinear registration using FMRIB's nonlinear image registration tool. Third, the resulting images were averaged to create a study‐specific template to which the native GM images were nonlinearly re‐registered. The optimized protocol introduced a modulation for the contraction/enlargement caused by the nonlinear component of the transformation: each value of the voxel in the registered GM image was multiplied by the Jacobian of the warp field. Fourth, the modulated GM images were then smoothed with an isotropic Gaussian kernel with a sigma of 4 mm.

fMRI Data Preprocessing

Functional data were analyzed with both FSL and automated functional neuroimaging (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni) software. Scripts containing the processing commands used in the current study have been released as part of the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/fcon_1000) [Biswal et al., 2010]. A standard data preprocessing strategy was performed. Specifically, (1) the first five echo‐planar imaging volumes were discarded to allow subjects to get used to the scanning environment and eliminate nonequilibrium effects of magnetization; (2) the remaining images were corrected by slice timing, three‐dimensional head motion correction, time series despiking, spatial smoothing, and four‐dimensional mean based intensity normalization; (3) the time series from each voxel in the corrected images was temporally filtered with a band‐pass filter (0.01–0.08 Hz) which removed the linear and quadratic trends; (4) nuisance signals (WM, cerebrospinal fluid signals and 24 motion parameters) were regressed out; and (5) the remaining images were spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute 152 space and resampled to 2‐mm isotropic voxels.

Functional Connectivity (FC) Analysis

FC analysis was performed by using a method based on a seeding voxel correction approach. The individual seed connectivity map (Fisher's r‐to‐z transformation) was calculated by correlating the mean time course of an ROI with all other voxels in the brain. In our results, the region that exhibited between‐group differences in the VBM results between the MOr and MOp at baseline was only found in the mPFC (see Results). Hence, the mPFC was chosen as a region of interest (ROI), which was derived from the union of activated brain regions by creating 6‐mm diameter spheres around the activated center of mass coordinates in the between‐group difference results. On the other hand, a tendency toward a greater alteration in anxiety was observed in MOr patients compared with MOp patients before and after placebo treatment, and only MOp patients had a significantly higher GM density in the amygdala (see Results). Hence, the amygdala was chosen as the second ROI.

Statistical Analysis

To test the group differences in subjects' basic information (age, years of education, height, weight, temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate), we analyzed the data with one‐way ANOVAs. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were then performed using t‐tests. The gender data were analyzed using a χ 2 test. To investigate the group differences in patients' migraine activity before and after placebo treatment, two‐way ANOVAs were applied.

Considering the effect of the total intracranial volume, regional changes in GM were assessed using permutation‐based nonparametric testing with 5,000 random permutations. Age, gender, and education were considered as covariates. Correction for multiple comparisons was carried out using a cluster‐based thresholding method, with an initial cluster forming a threshold at t = 2.0. The threshold for statistical significance was P < 0.05 with family‐wise error (FWE) correction for multiple comparison corrections. For the between group analysis among HC, MOr, and MOp groups, we analyzed the data with one‐way ANOVAs. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were then performed using t‐tests.

For the FC analysis, a two‐sample t‐test was used to evaluate the between‐group differences. The threshold for statistical significance was P < 0.05 with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparison corrections.

To further characterize the structural and functional alterations found in MO, a regression analysis was performed for clinical variables. To assess the strength of predictability of the MOr and MOp groups from GM volume at baseline, the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) were calculated.

RESULTS

Subject Demographics

In the sham acupuncture group, 12 patients were dropped due to discomfort, technical failures, or scheduling issues. Another six patients were excluded for missing the data of the migraine diary. The remaining 80 patients completed the study. After the treatment sessions, patients rated the credibility of traditional acupuncture and sham acupuncture. Eleven (13.8%) in the sham group and eight (8.1%) in the traditional acupuncture group believed that they had received sham acupuncture, and the two proportions of unblinding were not significantly different (P > 0.05, χ 2 test).

At baseline, there were no between‐group differences between HC and MO patients (age, gender, years of education, height, weight, temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate, Table 1). No patients took drugs during the whole experiment based on their records (see Supporting Information). MO patients were subdivided (50% change in migraine days from baseline) into recovering (MOr, n = 21) and persisting (MOp, n = 59) patients. As shown in Table 1, MOp and MOr had similar migraine activity at baseline, including migraine duration, migraine days, pain intensity, and migraine attack duration (P > 0.05). Patients also showed similar anxiety and depression characteristics at baseline (P > 0.05). After 8 weeks of sham acupuncture treatment, MOr subjects showed decreases in most migraine‐related measures. Most importantly, recovery from migraine was accompanied by significantly decreased anxiety in the MOr group. It should be noted that no significantly decreased anxiety was found in the MOp group after placebo treatment.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and clinical variables

| Information | Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 2 > Visit 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC (n = 50) | all patients (n = 80) | MOr (n = 21) | MOp (n = 59) | MOr (n = 21) | MOp (n = 59) | MOr, t values | Mop, t values | (r2 – r1) vs. (p2 – p1), F values | |

| Age (yr) | 22.6 ± 0.2 | 22.8 ± 0.3 | 22.1 ± 0.55 | 21.6 ± 0.37 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Height (cm) | 160.1 ± 0.9 | 159.9 ± 0.99 | 162.0 ± 2.03 | 158.8 ± 1.04 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Weight (kg) | 51.6 ± 1.1 | 52.5 ± 1.07 | 54.1 ± 1.80 | 51.6 ± 1.32 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Temperature | 36.8 ± 0.0.04 | 36.6 ± 0.05 | 36.7 ± 0.09 | 36.8 ± 0.07 | 36.7 ± 0.10 | 36.8 ± 0.06 | 1.68 (NS) | −0.97 (NS) | — |

| Blood pressure | 106.1 ± 0.97/79.3 ± 1.01 | 104.9 ± 0.85/78.3 ± 0.91 | 107.6 ± 1.69/71.3 ± 1.46 | 108.2 ± 1.08/72.9 ± 1.05 | 110.8 ± 1.9/73.9 ± 1.2 | 109.1 ± 1.49/73.4 ± 0.87 | 2.40 (NS)/1.71 (NS) | 1.4 (NS)/0.58 (NS) | — |

| Heart rate | 78 ± 0.53 | 77.3 ± 0.64 | 78.2 ± 1.08 | 76.9 ± 0.80 | 78.5 ± 1.10 | 77.0 ± 0.64 | 0.20 (NS) | −0.03 (NS) | — |

| Disease duration (mh) | — | 59.8 ± 4.7 | 47.7 ± 5.09 | 66.1 ± 6.39 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Headache days | — | 6.3 ± 0.81 | 8.8 ± 1.94 | 7.0 ± 0.55 | 3.1 ± 0.75 | 6.2 ± 0.67** | –2.75 * | 1.35 | 9.5** |

| VAS | — | 5.8 ± 0.17 | 5.5 ± 0.27 | 5.6 ± 0.50 | 3.15 ± 0.40 | 4.1 ± 0.30 | –4.7*** | –2.63 * | 0.8 (NS) |

| Average duration of a migraine attack (h) | — | 7.3 ± 0.7 | 8.6 ± 1.6 | 6.6 ± 0.79 | 4.0 ± 0.95 | 4.9 ± 0.69 | –2.4 * | −1.54 | 2.3 (NS) |

| SAS | — | 44.6.8 ± 1.03 | 44.4 ± 2.16 | 44.0 ± 1.22 | 35.0 ± 1.56 | 42.1 ± 1.58** | –3.89*** | −0.98 | 6.3 * |

| SDS | — | 43.7 ± 1.4 | 40.9 ± 2.57 | 44.1 ± 1.94 | 37.0 ± 2.69 | 41.6 ± 1.79 | −1.13 | −0.96 | 0.15 (NS) |

Values are mean ± SEM. Data show the headache activity and mood characteristics before (visit 1) and after (visit 2) sham acupuncture treatment, for MOr and MOp, respectively. MOp and MOr had similar headache activity at baseline, including migraine duration, attack frequency, pain intensity, and migraine attack duration. Patients also showed similar anxiety and depression characteristics at baseline. At visit 2, MOr patients showed decreases in most migraine‐related measures. The recovery from headache was accompanied by significantly decreased anxiety in MOr. The normal range of the SAS and SDS is 20 to 44.

MOr, migraine without aura, recovering; MOP, migraine without aura, persisting; NS, not significant; VAS, visual analogue scale; SAS, self‐rating anxiety scale; SDS, self‐rating depression scale; NS, nonsignificant.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

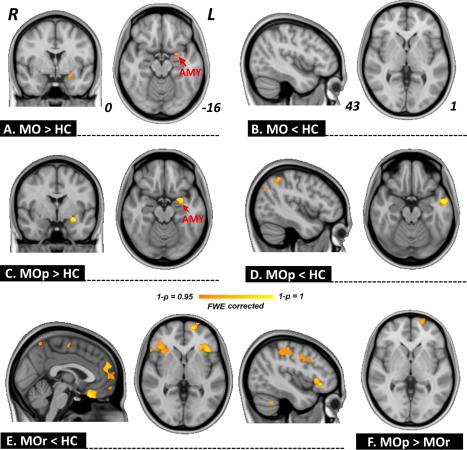

Whole‐Brain Comparison for GM Volume

In this study, we sought to investigate individual differences for hypoalgesia associated with placebo treatment, and all brain imaging scans were done before the start of the treatment. As compared with the HC group at baseline (Table 2), migraine patients exhibited a larger volume of the amygdala (P < 0.05, FWE corrected, Fig. 1A), and no smaller volume was found (Fig. 1B). For the between group comparisons among HC, MOp, and MOr groups, MOp patients had a significantly larger GM volume in the amygdala (P < 0.05, FWE corrected, Fig. 1C), and smaller GM volume in the inferior parietal, angular, and middle temporal gyri (P < 0.05, FWE corrected, Fig. 1D); MOr patients exhibited a significantly smaller volume in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), insula, orbitofrontal cortex, precentral gyrus, postcentral gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, and occipital cortices (P < 0.05, FWE corrected, Fig. 1E), and no significantly larger volume was found. It was important to note that a significant between‐group difference was only found in the mPFC as compared between the MOp and MOr groups (P < 0.05, FWE corrected, Fig. 1F, controlling the treatment credibility, SAS, SDS, and disease duration).

Table 2.

Between‐group differences in brain gray matter volume (P < 0.05, FWE corrected)

| Brain region | Side | Cluster sizes | Voxels with maximum effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talairach | ||||||

| x | y | z | P | |||

| MO > HC | ||||||

| Amygdala | L | 37 | −24 | −1 | −15 | 0.02 |

| MO < HC No significant between‐group differences | ||||||

| MOP > HC | ||||||

| Amygdala | L | 109 | −26 | −3 | −12 | 0.009 |

| MOP < HC | ||||||

| Angular gyrus | L | 23 | −48 | −68 | 31 | 0.046 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | L | 132 | −44 | −46 | 50 | 0.029 |

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 114 | −51 | −5 | −17 | 0.012 |

| MOr < HC | ||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | 106 | −36 | 29 | −6 | 0.027 |

| R | 117 | 34 | 19 | −8 | 0.031 | |

| Medial frontal gyrus | L | 193 | −14 | 56 | 1 | 0.008 |

| R | 50 | 4 | 23 | −15 | 0.029 | |

| Middle frontal gyrus | L | 104 | −22 | 52 | 21 | 0.012 |

| R | 92 | 18 | 40 | −19 | 0.03 | |

| Superior frontal gyrus | L | 163 | −20 | 52 | 21 | 0.008 |

| Precentral gyrus | L | 155 | −36 | −23 | 49 | 0.037 |

| R | 21 | 38 | 0 | 35 | 0.032 | |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | L | 36 | −2 | 54 | −1 | 0.042 |

| R | ||||||

| Inferior parietal lobule | L | 67 | −57 | −32 | 29 | 0.043 |

| Superior parietal lobule | L | 53 | −18 | −53 | 60 | 0.032 |

| R | 53 | 22 | 40 | −20 | 0.031 | |

| Postcentral gyrus | L | 160 | −55 | −18 | 32 | 0.034 |

| Insula | L | 24 | −36 | 21 | 1 | 0.03 |

| R | 27 | 28 | 19 | −3 | 0.031 | |

| MOP > MOr | ||||||

| Medial frontal gyrus | L | 17 | −14 | 58 | 1 | 0.004 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | L | 39 | −18 | 64 | −1 | 0.004 |

Figure 1.

Gray matter volume analysis. As compared with healthy controls (HC), patients with migraine without aura (MO) exhibited larger amygdala volume (A), and no significantly smaller volume was found (B). As compared with HC, migraine persistent patients (MOp) showed a larger volume of the amygdala (C) and smaller volume of the inferior parietal, angular, and middle temporal gyri (D); placebo responsive patients (MOr) exhibited a smaller volume in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), insula, orbitofrontal cortex, precentral gyrus, postcentral gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, and occipital cortices (E). Between‐group difference was only found in the mPFC as compared between the MOp and MOr groups (F). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

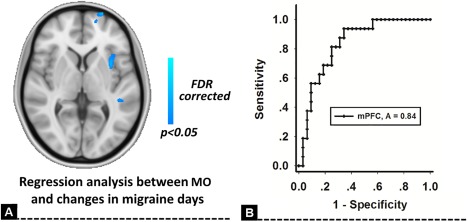

Regression Analysis Between Changes in Migraine Days and GM Volume

In our findings, the changes in migraine days after placebo treatment was significantly associated with the baseline GM volume of the mPFC in patients (P < 0.05, FDR corrected), and this significant correlation still hold even the treatment credibility, SAS, SDS, and disease duration were ruled out (Fig. 2A). The ROC for discriminating between MOp and MOr groups was 0.84 (P < 0.01) for the GM volume of the mPFC at baseline (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Regression analysis for changes in migraine days. The changes in migraine days after placebo treatment were significantly associated with the baseline GM volume of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) in MO patients (A). The GM volume of the mPFC at baseline could discriminate persistent patients (MOp) and placebo responsive patients (MOr) with high accuracy (B). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

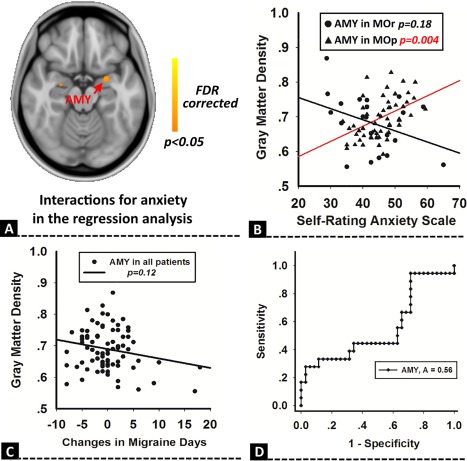

Given the interesting results regarding anxiety, between‐group differences in correlation between GM volume and anxiety were performed by using the regression analysis in the MOp and MOr groups. In our results, the amygdala showed a significant interactive effect between different patient groups (P < 0.05, FDR corrected, Fig. 3A). Additionally, a significantly positive association between GM volume of the amygdala and SAS was found in the MOp group (r = 0.49, P = 0.004, Fig. 3C), and there was no correlation in the MOr group (r = −0.23, P = 0.18, Fig. 3C). No significant association was found between the baseline GM volume of the amygdala and the changes in migraine days (Fig. 3C). The ROC for discriminating between MOp and MOr groups was 0.56 for the amygdala (Fig. 3D), which suggested that the GM volume of the amygdala at baseline could not predict future outcomes of migraine patients.

Figure 3.

Regression analysis for anxiety. Between‐group differences in the correlation between GM volume and anxiety had a significantly interactive effect in the amygdala (A). The GM volume of the amygdala was positively associated with anxiety in MOp, but not in the placebo responsive patients (MOr) group (B). The GM volume of the amygdala was not associated with the changes in migraine days (C), and could not predict future placebo outcomes of migraine patients (D). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

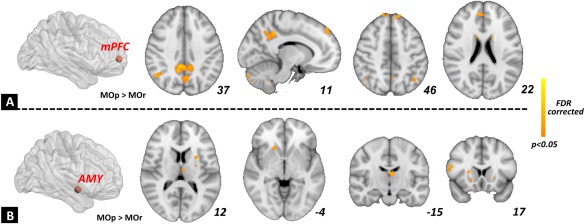

Interindividual Differences for FC Intensity in Patients

In this study, the mPFC and amygdala were selected as the seed regions for the FC analysis. For the intensity of mPFC‐related connections, significant between group differences (MOP > MOr) were mainly located in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC)/precuneus, the medial part of the superior frontal gyrus (SFG), orbital part of the SFG, and the putamen (P < 0.05, FDR corrected, Fig. 4A). For the intensity of amygdala‐related connections, significant between group differences were found in the thalamus, putamen, caudate, and the opercular part of the inferior frontal gyrus (P < 0.05, FDR corrected, Fig. 4B). We did not find any significant higher level of FC in the MOr group as compared with the MOp group.

Figure 4.

Functional connectivity analysis for the individual differences in migraine patients. The mPFC (A) and amygdala (B) were selected as the seed regions. For the between‐group differences (MOp vs. MOr), the MOp group exhibited a higher intensity of FC in the mPFC‐default mode network and amygdala‐striatum connections. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DISCUSSION

In our study, we demonstrated that psychological factors could induce the reduction of migraine days in MO patients, and baseline brain GM volume of the mPFC could predict future placebo responses in migraineurs. Our results also suggested that anxiety had an important influence on placebo hypoalgesia in migraineurs. It indicated that structural properties of a migraine brain may preface the extent of placebo treatment.

The major finding of our study is that significant between‐group difference of the GM volume in the mPFC was found between MOp and MOr groups. The role of the mPFC in chronic pain has been established in several recent morphological studies, including subjects with migraine [Liu et al., 2013], chronic back pain [Apkarian et al., 2011], irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia [May, 2010]. Schmitz et al. investigated cortical structure and executive function in patients with migraine, and they found decreased GM density in the mPFC in migraine patients, which was also correlated with delayed response time to the set‐shifting task [Schmitz et al., 2008]. Building on these growing studies of mPFC abnormalities in chronic pain, our findings were consistent with previous studies and found a significantly lower GM volume of the mPFC in migraineurs. Additionally, we found the association between anatomical properties of the mPFC in migraine patients at baseline and the analgesic effects of placebo treatment. As the GM volume of the mPFC was reported to be closely associated with decision making, memory, and planning, our findings supported the inference that the mPFC may integrate prior experience and drive the top–down modulation for future placebo responses [Tetreault et al., 2016].

In our results, between groups differences of mPFC‐related FC were mainly located in the default mode network (DMN) as compared between the MOr and MOp groups. Initial neuroimaging studies suggested that the DMN, mainly comprised of the PCC/precuneus and mPFC, was the primary network related to chronic pain. The mPFC is a key node whose functional connectivity is related to pain‐attention interactions and may act as an “exchange hinge” for distributing pain‐related information to the brain connectome [Kucyi and Davis, 2015]. Several studies pointed out that dysregulated functional connectivity of the mPFC with other brain regions in the DMN was related to chronic pain patients' degree of rumination and intensity about their pain [Aaron et al., 2014; Loggia et al., 2013]. While a diffusion MRI study revealed a structural connection between the mPFC and periaqueductal gray (PAG) (a hub region in the descending pain modulatory system), Kucyi et al. [2013] found that increased mPFC‐PAG functional connectivity dynamically tracked spontaneous attention away from pain in healthy individuals [Kucyi et al., 2013], indicating mPFC mediated DMN interactions with the descending pain modulatory system [Aaron et al., 2014]. Additionally, the salience network, having a close relationship with the function of the ascending pain system [Kucyi and Davis, 2015; Kucyi et al., 2013], had abnormal functional connectivity with the mPFC in several cases of chronic pain conditions [Baliki et al., 2014]. Thus, the mPFC via its frequent communication with multiple levels of pain‐related brain circuits may be in a unique position, which can reflect individual differences for the level of pain that can be perceived subsequently. Recently, wager et al. found that baseline brain activation of the mPFC predicted analgesic responses to placebo conditioning in healthy subjects [Wager et al., 2011]. Hashmi et al. and TeÂtreault et al. reported the significant association between the functional connectivity of the mPFC at rest and placebo analgesic response in chronic knee pain patients [Javeria Ali et al., 2014; Tetreault et al., 2016]. Our study builds on this growing literature by showing an aberrant resting state mPFC connectivity that could differentiate placebo responders and nonresponders in migraine. It provided evidence for brain‐based placebo prediction in migraine patients, and indicated that the placebo response could be predicted and mediated by functional connections of the mPFC.

A previous study suggested that the placebo response would be altered in chronic pain due to each patient's particular emotionally‐associated learning and behavior [Hashmi et al., 2012]. As shown by our results, MOp groups exhibited a larger GM volume in the amygdala with higher anxiety scores even after placebo treatment. The amygdala consists of several functionally distinct nuclei, including the lateral (LA), basolateral (BLA), and central nuclei (CE) [Sah et al., 2003]. The interaction between LA‐BLA was associated with processed emotional significance to sensory stimuli, and affect‐related information was then transmitted to the CE which directly mediates aspects of fear learning and facilitates fear memory operations [LaBar and Cabeza, 2006]. One human imaging study showed that the amygdala was a key region in rapid, automatic and non‐conscious processing of emotional stimuli and memory [Pessoa and Adolphs, 2010]. Its role may be related to the high levels of fear and anxiety in patients with migraine [Casucci et al., 2010], particularly in those suffering from chronic daily migraine [Dodick, 2009]. In our findings, as compared between MOr and MOp groups, significant differences were found in the amygdala‐striatum connections which were involved in the emotional/affective and cognitive dimension of pain and pain modulation [Iii, 2009]. Hence, variability of treatment outcomes across the MOp and MOr group, in part, may be due to differences in GM volume of the amygdala at baseline and a larger amygdala may act as a moderating variable of placebo effects.

There are several issues that should be addressed. First, sham acupuncture treatment has been previously reported to be effective in migraine prophylaxis, even superior to oral placebo medications [Klaus et al., 2005]. It suggests that sham acupuncture could be an effective treatment, and not just a “pure placebo.” Some studies suggested that part of the enhanced placebo effect may be due to the physiological effects of skin injury during the stimulation [Lund and Lundeberg, 2006]. In our study, to make sham acupuncture be a “pure placebo,” sham acupuncture was performed by using Streitberger needles at nonacupoints located near real acupoints. Based on our findings, this indicated that the effectiveness of sham acupuncture was closely related to individual ability of emotional processing. However, this needs to be proved further. Second, all of the patients in our study were enrolled from the local university, and they were much younger and were all episodic migraine patients. Although patients were allowed to take pirprofen when their migraine was difficult to endure, no patients took drugs during the whole experiment based on their records. Whether this would affect our findings needs further study. Third, it is a limit of the study that anxiety was not assessed in the control subjects. A better interpretation of the anxiety‐related brain results would be possible if we knew whether the patients had high anxiety levels at baseline/after treatment.

In our study, we reported that interindividual variability in the brain structure could predict future placebo responses in migraine patients. This indicated that individual differences of migraineurs were reflected in the structure of brain circuits at baseline, which served as a substrate on how an individual facilitated or diminished analgesic responses to psychological signals. Our findings are insights for a potential useful predictor of analgesic responses, and have implications for developing personalized therapies for migraine patients.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Contributor Information

Ming Zhang, Email: profzmmri@gmail.com.

Jie Tian, Email: tian@ieee.org.

REFERENCES

- Aaron K, Massieh M, Irit WF, Goldberg MB, Freeman BV, Tenenbaum HC, Davis KD (2014): Enhanced medial prefrontal‐default mode network functional connectivity in chronic pain and its association with pain rumination. J Neurosci 34:3969–3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkarian AV, Hashmi JA, Baliki MN (2011): Pain and the brain: Specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain 152:S49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchel C, Geuter S, Sprenger C, Eippert F (2014): Placebo analgesia: A predictive coding perspective. Neuron 81:1223–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliki MN, Mansour AR, Baria AT, Apkarian AV (2014): Functional reorganization of the default mode network across chronic pain conditions. PLoS One 9:e106133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliki MN, Schnitzer TJ, Bauer WR, Apkarian AV (2011): Brain morphological signatures for chronic pain. PLos One 6:e26010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F, Mayberg HS, Wager TD, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK (2005): Neurobiological mechanisms of the placebo effect. J Neurosci 25:10390–10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal BB, Mennes M, Zuo X‐N, Gohel S, Kelly C, Smith SM, Beckmann CF, Adelstein JS, Buckner RL, Colcombe S (2010): Toward discovery science of human brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:4734–4739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsook D, Maleki N, Becerra L, Mcewen B (2012): Understanding migraine through the lens of maladaptive stress responses: A model disease of allostatic load. Neuron 73:219–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casucci G, Villani V, Finocchi C (2010): Therapeutic strategies in migraine patients with mood and anxiety disorders: Physiopathological basis. Neurol Sci 31:99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colloca L, Benedetti F (2009): Placebo analgesia induced by social observational learning. Pain 144:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craggs JG, Price DD, Perlstein WM, Verne GN, Robinson ME (2008): The dynamic mechanisms of placebo induced analgesia: Evidence of sustained and transient regional involvement. Pain 139:660–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederich NJ, Goetz CG (2008): The placebo treatments in neurosciences. New insights from clinical and neuroimaging studies. Neurology 71:677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener H‐C (2009): Migraine: Is acupuncture clinically viable for treating acute migraine? Nat Rev Neurol 5:469–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodick D (2009): Review of comorbidities and risk factors for the development of migraine complications (infarct and chronic migraine). Cephalalgia 29:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eippert F, Bingel U, Schoell ED, Yacubian J, Klinger R, Lorenz J, Büchel C (2009): Activation of the opioidergic descending pain control system underlies placebo analgesia. Neuron 63:533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi JA, Baria AT, Baliki MN, Huang L, Schnitzer TJ, Apkarian AV (2012): Brain networks predicting placebo analgesia in a clinical trial for chronic back pain. Pain 153:2393–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HC Lu, JC Hsieh, Lu CL, Niddam DM, Wu YT, Yeh TC, Cheng CM, Chang FY, Lee SD (2010): Neuronal correlates in the modulation of placebo analgesia in experimentally‐induced esophageal pain: A 3T‐fMRI study. Pain 148:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KK, Liu J, Marina O, Napadow V, Haselgrove C, Kwong KK, Kennedy DN, Makris N (2005): The integrated response of the human cerebro‐cerebellar and limbic systems to acupuncture stimulation at ST 36 as evidenced by fMRI. Neuroimage 27:479–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iii AEL (2009): Chronic headaches: Biology, psychology, and behavioral treatment. Cephalalgia 29:1344–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Javeria Ali H, Jian K, Rosa S, Sheraz K, Kaptchuk TJ, Gollub RL (2014): Functional network architecture predicts psychologically mediated analgesia related to treatment in chronic knee pain patients. J Neurosci 34:3924–3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S (2002): Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 17:825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S (2001): A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 5:143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus L, Andrea S, Susanne J, Andrea H, Benno B, Claudia W, Stephan W, Volker P, Hammes MG, Wolfgang W (2005): Acupuncture for patients with migraine: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 106:2118–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Kaptchuk TJ, Polich G, Kirsch I, Vangel M, Zyloney C, Rosen B, Gollub R (2009): Expectancy and treatment interactions: A dissociation between acupuncture analgesia and expectancy evoked placebo analgesia. Neuroimage 45:940–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Spaeth R, Cook A, Kirsch I, Claggett B, Vangel M, Gollub RL, Smoller JW, Kaptchuk TJ (2013): Are all placebo effects equal? Placebo pills, sham acupuncture, cue conditioning and their association. PLoS One 8:e67485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucyi A, Davis KD (2015): The dynamic pain connectome. Trends Neurosci 38:86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucyi A, Salomons T, Davis KD (2013): Mind wandering away from pain dynamically engages antinociceptive and default mode brain networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:18692–18697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBar KS, Cabeza R (2006): Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nat Rev Neurosci 7:54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, Fei Y, Mehring M, Vertosick EA, Vickers A, White AR (2016): Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD001218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde K, Streng A, Jürgens S, Hoppe A, Brinkhaus B, Witt C, Wagenpfeil S, Pfaffenrath V, Hammes MG, Weidenhammer W (2005): Acupuncture for patients with migraine: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293:2118–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lan L, Li G, Yan X, Nan J, Xiong S, Yin Q, von Deneen KM, Gong Q, Liang F (2013): Migraine‐related gray matter and white matter changes at a 1‐year follow‐up evaluation. J Pain 14:1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loggia ML, Kim J, Gollub RL, Vangel MG, Kirsch I, Kong J, Wasan AD, Napadow V (2013): Default mode network connectivity encodes clinical pain: An arterial spin labeling study. Pain 154:24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund I, Lundeberg T (2006): Are minimal, superficial or sham acupuncture procedures acceptable as inert placebo controls? Acupunct Med 24:13–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May A (2010): Chronic pain may change the structure of the brain. Pain 137:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchart D, Linde K, Fischer P, White A, Allais G, Vickers A, Berman B (1999): Acupuncture for recurrent headaches: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Cephalalgia 19:779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Adolphs R (2010): Emotion processing and the amygdala: From a ‘low road’ to ‘many roads’ of evaluating biological significance. Nat Rev Neursci 11:773–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollo A, Amanzio M, Arslanian A, Casadio C, Maggi G, Benedetti F (2001): Response expectancies in placebo analgesia and their clinical relevance. Pain 93:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Faber EL, De Armentia ML, Power J (2003): The amygdaloid complex: Anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev 83:803–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz N, Arkink EB, Mulder M, Rubia K, Admiraal‐Behloul F, Schoonman GG, Kruit MC, Ferrari MD, van Buchem MA (2008): Frontal lobe structure and executive function in migraine patients. Neurosci Lett 440:92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Stohler CS, Egnatuk CM, Wang H, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK (2007): Individual differences in reward responding explain placebo‐induced expectations and effects. Neuron 55:325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM (2002): Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp 17:143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streitberger K, Kleinhenz J (1998): Introducing a placebo needle into acupuncture research. Lancet 352:364–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetreault P, Mansour A, Vachon‐Presseau E, Schnitzer TJ, Apkarian AV, Baliki MN (2016): Brain connectivity predicts placebo response across chronic pain clinical trials. PLoS Biol 14:e1002570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tfelt‐Hansen P, Pascual J, Ramadan N, Dahlöf C, D'Amico D, Diener HC, Hansen JM, Lanteri‐Minet M, Loder E, Mccrory D (2012): Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: Third edition. A guide for investigators. Cephalalgia 32:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Atlas LY, Leotti LA, Rilling JK (2011): Predicting individual differences in placebo analgesia: Contributions of brain activity during anticipation and pain experience. J Neurosci 31:439–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson A, El‐Deredy W, Iannetti GD, Lloyd D, Tracey I, Vogt BA, Nadeau V, Jones AKP (2009): Placebo conditioning and placebo analgesia modulate a common brain network during pain anticipation and perception. Pain 145:24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S (2001): Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation‐maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 20:45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Bueller JA, Jackson LR, Scott DJ, Xu Y, Koeppe RA, Nichols TE, Stohler CS (2005): Placebo effects mediated byendogenous opioid activity on μ‐opioid receptors. J Neurosci 25:7754–7762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Stohler CS (2009): Neurobiological mechanisms of placebo responses. Ann NY Acad Sci 1156:198–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information