Abstract

In this quantitative review, we specified the anatomical basis of brain activity reported in the Temporo‐Parietal Junction (TPJ) in Theory of Mind (ToM) research. Using probabilistic brain atlases, we labeled TPJ peak coordinates reported in the literature. This was carried out for four different atlas modalities: (i) gyral‐parcellation, (ii) sulco‐gyral parcellation, (iii) cytoarchitectonic parcellation and (iv) connectivity‐based parcellation. In addition, our review distinguished between two ToM task types (false belief and social animations) and a nonsocial task (attention reorienting). We estimated the mean probabilities of activation for each atlas label, and found that for all three task types part of TPJ activations fell into the same areas: (i) Angular Gyrus (AG) and Lateral Occpital Cortex (LOC) in terms of a gyral atlas, (ii) AG and Superior Temporal Sulcus (STS) in terms of a sulco‐gyral atlas, (iii) areas PGa and PGp in terms of cytoarchitecture and (iv) area TPJp in terms of a connectivity‐based parcellation atlas. Beside these commonalities, we also found that individual task types showed preferential activation for particular labels. Main findings for the right hemisphere were preferential activation for false belief tasks in AG/PGa, and in Supramarginal Gyrus (SMG)/PFm for attention reorienting. Social animations showed strongest selective activation in the left hemisphere, specifically in left Middle Temporal Gyrus (MTG). We discuss how our results (i.e., identified atlas structures) can provide a new reference for describing future findings, with the aim to integrate different labels and terminologies used for studying brain activity around the TPJ. Hum Brain Mapp 38:4788–4805, 2017. © 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: mentalizing, social cognition, attention reorienting, neuroanatomy, angular gyrus, superior temporal sulcus

INTRODUCTION

The TPJ

The term Temporo‐Parietal Junction (TPJ) is often used for labeling functional activations around the border of parietal and posterior temporal lobes in multiple fields of research. In the social cognitive neurosciences, TPJ activation is a prominent neural correlate of Theory of Mind (ToM), that is, the human ability to ascribe mental states like beliefs and desires to other people [see e.g., Molenberghs et al., 2016; Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003; Schurz et al., 2014; Spreng et al., 2009; Van Overwalle, 2009]. A crucial role of the right TPJ for mentalizing was found in transcranial magnetic stimulation studies, showing that a transient disruption of the area impairs reasoning about the beliefs of others [Krall et al., 2016; Young et al., 2010]. Moreover, imaging studies [for meta‐analysis, see Sugranyes et al., 2011] found TPJ dysfunction in clinical disorders that involve ToM impairments, as for example autism [Yirmiya et al., 1998] and schizophrenia [Sprong et al., 2007].

To date, there exists little consensus regarding microanatomical or macroanatomical landmarks that topographically define the TPJ area [c.f. Bzdok et al., 2013a,b; Geng and Vossel, 2013; Mars et al., 2011], hampering a precise comparison of theories and conclusions drawn about the neurocognitive processes underlying TPJ activity across different ToM studies, and across ToM and nonToM studies. Anatomical characterizations of the TPJ are found sporadically in the literature. We illustrate some of them in Figure 1A: Characterizations have been ranging from a focal area within one gyrus [Chambers et al., 2004] to an intersection area between different gyri/sulci [Mort et al., 2003] and a broader area comprising several gyri and sulci [Corbetta et al., 2008; Decety and Lamm, 2007]. Figure 1A also shows a historical example of an early mentioning of “temporo‐parietale” used to classify the locus of brain damage producing a certain form of behavioral, cognitive and motor dysfunctions [Krönlein, 1886; see also Stenger, 1881].

Figure 1.

(A) Example anatomical specifications of the TPJ. Colored areas show major gyri, according to a widely used macroscopic parcellation of the MNI brain [Tzourio‐Mazoyer et al., 2002]. LOC, Lateral Occipital Cortex (area labeled LOC for consistency with some TPJ definitions, actually corresponds to Middle Occipital Gyrus); AG, Angular Gyrus; SMG, Supramarginal Gyrus; IPL, Inferior Parietal Lobule; STG, Superior Temporal Gyrus; pSTS, posterior Superior Temporal Sulcus. Image A.6. from “Über die Trepanation bei Blutungen aus der A. meningea media und geschlossener Schädelkapsel” by R.U. Krünlein, 1886, Deutsche Zeitschrift für Chirurgie, p. 216. Adapted with permission of Springer. (B) Display of all TPJ relevant structures in different atlases. Structures from gyral, cytoarchitectonic and connectivity‐based parcellation atlases are shown in MNI space, sulco‐gyral atlas structures are shown in TAL space. For display purposes, we thresholded the probabilistic atlas maps of connectivity‐parcellations and cytoarchitectonics at 0.50, of gyral‐parcellations at 0.25 and of sulco‐gyral parcellations at 0.20. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Aims of the Present Review

This review aims to shed light on the relation between functional activations of the TPJ and underlying brain structure in ToM research. More specifically, we take a quantitative approach to test if functional activations of the TPJ are systematically related to specific brain structures, or unsystematically distributed across diverse cortical areas/lobes. We seek to advance knowledge regarding function‐structure correspondence in the TPJ for ToM by addressing three important issues surrounding the topic: (i) The anatomical level at which correspondence can be found (ii) The role of interindividual variability in brain anatomy (iii) The effects of stimuli and task‐instructions for probing ToM brain activation. In the following sections, we motivate each issue and lay out our approach for addressing it.

i. The Anatomical Level at which Correspondence Can be Found

The existence of a consistent relation between functional activations of the TPJ and anatomical structures commonly used for labeling is an open question for several reasons. First, TPJ activations may not fall into a gyrus or several gyri, but alternatively (or additionally) in sulci such as the posterior Superior Temporal Sulcus (pSTS). In fact, both the labels TPJ [e.g., Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003, Schaafsma et al., 2015; Spunt and Adolphs, 2014; Spunt et al., 2016] and pSTS [Carrington and Bailey, 2009; Frith and Frith, 2008, 2003; Lieberman, 2007; Singer, 2006] are highly popular for characterizing brain functions involved in social cognition and ToM. However, since most ToM research relied on volume‐based brain analyses and gyral parcellations, explicit distinctions between temporo‐parietal gyri and adjacent pSTS are rare [for a recent exception, see Deen et al., 2015]. Nevertheless, it is estimated that around 55% [Destrieux et al., 2010] to 60% [Van Essen, 2005; Zilles et al., 1997] of cortex are buried in sulci and lateral fossa. To address this issue in our review, we label functional activations not only with a gyral atlas, but also with a sulco‐gyral atlas based on freesurfer cortical surface analysis (using a 3D transformed version, see Methods).

Second, it is an open question if functional specialization of the TPJ area consistently relates to sulcal and gyral patterns at all. While functional specialization of an area is known to be strongly determined by cytoarchitectonic features [e.g., Luppino et al., 1991], the relationship between cytoarchitectonic borders and surrounding sulci and gyri is rather loose for most multimodal association areas such as the TPJ [e.g., Amunts et al., 1999; see also Amunts et al., 2007]. To address this issue, we will specify the anatomical basis of functional TPJ activations not only by gyral and sulco‐gyral atlases, but also in terms of a cytoarchitectonic atlas [Caspers et al., 2006, 2008].

In addition, our labeling based on a cytoarchitectonic atlas will be complemented by a recent connectivity‐based parcellation (CBP) atlas, grouping together voxels with a common connectivity pattern to the rest of the brain [Johansen‐Berg et al., 2004]. A consistent relation between single‐subject connectivity‐patterns and task‐based functional activations was shown in previous studies [e.g., Osher et al., 2016; Saygin et al., 2016; Tavor et al., 2016]. Furthermore, a recent study showed high correspondence between cytoarchitectonic and connectivity‐based parcellation areas [Henssen et al., 2016], which motivates the use of both types of atlases in our review for obtaining a robust and detailed characterization of brain anatomy of the TPJ.

ii. The Role of Interindividual Variability in Brain Anatomy

Another issue we address is that TPJ shows high interindividual variability in macroanatomy [e.g., Segal and Petrides, 2012; Zlatkina and Petrides, 2014], which is characteristic for multimodal association areas of the cortex [Van Essen, 2005]. This could obscure an accurate anatomical characterization of functional activations found in the area. The present review tackles this problem by using probabilistic atlases of the different imaging modalities we motivated above [Caspers et al., 2006, 2008; Desikan et al., 2006; Destrieux et al., 2010; Mars et al., 2012]. These atlases are probabilistic in the sense that they explicitly incorporate measurements of interindividual variability in structure at any coordinate [Devlin and Poldrack, 2007]. Concretely, this means that one coordinate can be probabilistically assigned to multiple areas, that is, probability values indicate in how many subjects the coordinate is referring to particular areas.1

iii. The Effects of Stimuli and Task‐Instructions for Probing ToM Brain Activation

The third issue we address is the role of stimulus‐type and task‐instructions in probing brain activity for ToM. We recently found in a voxel‐wise imaging meta‐analysis that activation in posterior temporo‐parietal areas is largely distinct for different ToM task types [Schurz et al., 2014]. In the present review, we follow up this finding by systematically studying the underlying anatomy. Comparing anatomy between different ToM task types adds a new level of detail to insights from earlier reviews [e.g., Bzdok et al., 2012; Decety and Lamm, 2007; Geng and Vossel, 2013], where different experimental paradigms have been pooled together to identify common activation across all ToM tasks.

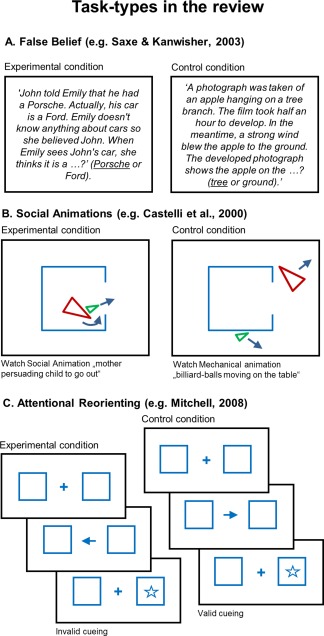

Concretely, we will compare findings from the ToM tasks false belief and social animations. Research shows that these tasks activate slightly different parts of the temporo‐parietal cortex [e.g., Bahnemann et al., 2010; Gobbini et al., 2007; Schurz et al., 2014], which was linked to conceptual differences between the tasks: False belief studies present stories about persons with incorrect assumptions or beliefs about a state of affairs. Such stories are thought to represent a prototypical and theoretically important test of ToM reasoning abilities [e.g., Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003; Saxe et al., 2004]. In contrast, social animations are intended [Castelli et al., 2000, 2002] as a low‐level alternative to the verbal stimuli used in many ToM tasks. In social animation tasks, a movie shows simple geometrical shapes (e.g., two triangles) moving across the display and portraying actions that are typical for an intentional or social interaction. Examples for both false belief and social animations tasks are given in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Examples for the three task types reviewed. (A). False belief tasks presenting written stories about false belief (left) versus false photo controls (right). (B). Social animations presenting movies of geometrical shapes that portray a social interaction (left: mother playing with child) or purely mechanical movements (right: billiard‐balls moving on the table). (C). In the critical experimental condition, attention reorienting tasks ask for redirecting attention towards a target stimulus after a breach of expectation (here: invalid cueing condition). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Finally, we not only seek to find out how well our labeling approach characterizes TPJ anatomy for ToM, but also in how far this characterization is distinct from what is found for nonsocial tasks. An important debate over the last decade regards the TPJ's role in attention versus socio‐cognitive processes [Decetyand Lamm, 2007; Igelström et al., 2016; Krall et al., 2015, 2016; Kubit and Jack, 2013; Lee and McCarthy, 2016; Mitchell, 2008; Özdem et al., 2017; Scholz et al., 2009; see also Carter and Huettel, 2013]. Therefore, we include attention reorienting tasks in our review, allowing us to contrast the anatomical characterization for ToM tasks to that found for a nonsocial task, which requires the redirection of attention toward a target stimulus after a breach of expectation. By specifying the anatomical basis of TPJ activations for ToM and attention reorienting, we provide a starting point for studying overlaps and differences in TPJ activation reported for ToM and many other research fields outside the scope of this review, such as reasoning about actions [e.g., Molenberghs et al., 2009; Spunt et al., 2016; Van Overwalle, 2009], empathy [e.g., Bzdok et al., 2012; Lamm et al., 2011; Singer and Lamm, 2009], episodic memory [e.g., Spreng et al., 2009], semantic processing [e.g., Binder et al., 2009], visuospatial navigation [e.g., Spreng et al., 2009], reading and comprehension [e.g., Seghier, 2013], bodily awareness [e.g., Blanke et al., 2002] or inhibition in go/no‐go tasks [e.g., Nee et al., 2007].

Questions and Hypotheses

We laid out outstanding issues for finding structure‐function correspondence in the TPJ, and presented how our review will address them by a multiple‐modality and probabilistic atlas labeling approach, focusing on two different ToM task types and a task type outside the social domain. Our review will cover functional activity for both left and right TPJ, although the right TPJ tends to be discussed more frequently in the Theory of Mind literature [e.g., Bzdok et al., 2013b; Corbetta et al., 2008; Decety and Lamm, 2007; Krall et al., 2015, 2016; Kubit and Jack, 2013; Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003]. Our main interest is to provide an evaluation of the following questions: (i) Within each task type, do activations labeled as “TPJ” fall reliably into individual anatomical structures, or are they distributed broadly and with high variance over the temporo‐parietal cortex? (ii) When comparing different task types, do activations labeled as “TPJ” fall in the same or into different anatomical structures?

METHODS

Atlases for Labeling

Gyral and sulco‐gyral anatomy

For labeling functional activations, we used two macroanatomical atlases. First, we used a standard macroanatomical (i.e., gyral parcellation) brain atlas (Harvard‐Oxford Cortical Structural Atlas) [Desikan et al., 2006]. Second, we used a sulco‐gyral parcellation atlas that is based on a freesurfer cortical surface analysis [Dale et al., 1999; Fischl et al., 1999]. The approach for this atlas [Destrieux et al., 2010] was to first define gyri based on a 3D reconstruction of the cortex, and then inflate this model to label sulci. As activation coordinates reported in this review have been generated by 3D volume‐based frameworks, we use a 3D transformed Talairach space version of the sulco‐gyral atlas, referred to as TT_desai_ddpmaps in AFNI (https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni/) and provided by R. Desai and colleagues [e.g., Liebenthal et al., 2014]. The map is shown Figure 1B.

Cytoarchitecture

We additionally used a cytoarchitectonic atlas, which is based on segregating cortical areas according to the type and organization of cells they contain. Cytoarchitectonics have been found to closely correspond to functional specialization of an area [e.g., Luppino et al., 1991]. At present, cytoarchitectonic maps do not cover the whole brain, and mapping is still in progress as it is a time‐consuming process [Amunts et al., 2007]. For currently available maps see the SPM Anatomy Toolbox [Eickhoff et al., 2005, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/ext/]. With respect to areas surrounding the TPJ, cytoarchitectonic maps are to date available for the Inferior Parietal Lobule (IPL), and not for posterior temporal lobe structures such as posterior superior temporal gyrus and sulcus. As shown in Figure 1B, the IPL can be divided into into seven subareas based on cytoarchitectonic features [Caspers et al., 2006, 2008]. In addition to differences in cytoarchitecture, these seven subareas of IPL also show different white‐matter connectivity fingerprints [Caspers et al., 2011], and have different patterns of neurotransmitter receptor densities [Caspers et al., 2013].

Connectivity‐based parcellations

Connectivity‐based parcellation analysis [CBP, Johansen‐Berg et al., 2004; for reviews see Eickhoff et al., 2015; Mars et al., 2016] groups voxels into an area if they show a common pattern of structural brain connectivity with the rest of the brain—distinct from that in neighboring voxels. In the present review, we use connectivity‐based parcellation atlases of TPJ and adjacent IPL that are based on diffusion weighted imaging data [Mars et al., 2011, 2012]. As illustrated in Figure 1B, the TPJ is divided into three subareas TPJa, TPJp and IPL, which are linked to distinct brain networks. Further connectivity‐based parcellations of the TPJ have been performed recently [Bzdok et al., 2013b; Igelström et al., 2015; Yeo et al., 2011, see also Uddin et al., 2010]. For example, Bzdok et al. [2013b] relied on resting‐state fMRI and meta‐analytic coactivation data for connectivity‐parcellation, and results are in good correspondence to Mars et al. [2012] with respect to an anterior/posterior division in the TPJ—Bzdok et al.'s [2013b] parcellation is shown in Figure 1A. All atlases used in the review were accessed with FSL (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslview/) or AFNI (https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni/) software.

Literature Samples

We analyzed the literature samples from our meta‐analysis on ToM [Schurz et al., 2014] and a meta‐analysis on attention reorienting [Kubitand Jack, 2013]. We included 15 studies using false belief tasks, 14 studies presenting social animations, and 15 studies presenting attention reorienting tasks [for further details see Kubit and Jack, 2013; Schurz et al., 2014]. All studies reported activation coordinates in standard space, and whenever necessary (different with each atlas we used for labeling), we converted from/to MNI or TAL space by using a matrix transformation by Lancaster et al. [2007].

For the ToM task types, literature samples were retrieved by a database search with the key words (i) “neuroimaging” or “fMRI” or “PET” and (ii) “theory‐of‐mind” or “mentalizing” or “mindreading,” and additionally by considering studies cited in earlier ToM reviews [e.g., Bzdok et al., 2012; Denny et al., 2012; Mar, 2011; Murray et al., 2012; Perner and Leekam, 2008; Spreng et al., 2009; Van Overwalle, 2009; Van Overwalle and Baetens, 2009].

Studies were included in the false belief sample if they presented written stories about a person's false belief (see Fig. 2A). Activation coordinates were only taken from contrasts between false belief versus false photo control stories. In this closely matched type of control condition, participants read stories where they have to represent the outdated content of a physical representation. Studies were included in the social animations category, if they presented movies with simple geometrical shapes (e.g., triangles) that portrayed a social or intentional interaction (Fig. 2B). Activation coordinates were taken from contrasts between movies showing movements that characterize social/intentional interactions and movies showing random or purely mechanical movements.

For attention reorienting tasks, a database search with the key‐words (i) “fMRI” or “PET” and (ii) “reorienting” or “posner” was performed, and additionally studies cited in earlier attention reorienting reviews were considered [Corbettaand Shulman, 2002; Corbetta et al., 2008; Decety and Lamm, 2007].

Tasks were considered as attention reorienting, if participants had to redirect attention towards a target stimulus after a breach of expectation (see Fig. 2C). Activation coordinates were taken from contrasts that compared participants having to redirect attention after being misinformed about the location of an upcoming target stimulus versus participants being correctly informed about the location of the upcoming target.

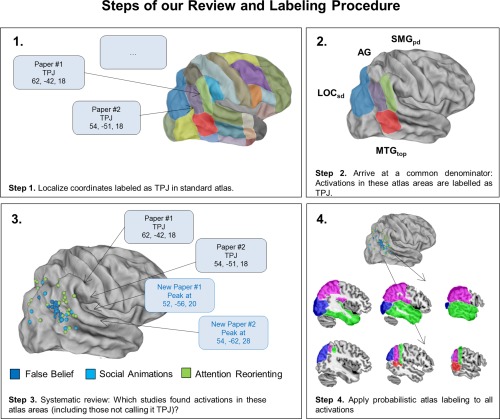

Procedure: Definition of TPJ and Steps for Labeling

Figure 3 illustrates the steps of our review. The first step was forming a “democratic” common denominator of the label TPJ. We went through results and discussion sections of individual papers and looked for coordinates of activations that were referred to as “Temporo‐Parietal Junction” or “TPJ.” We collected all these coordinates and labeled them with a standard macroanatomical brain atlas that is covering all temporal and parietal cortical territory (Harvard‐Oxford Cortical Structural Atlas) [Desikan et al., 2006]. That is, we assigned the most probable label to each coordinate, resulting in a list of all atlas structures referred to as “TPJ” (see Fig. 3—Step 2): Angular Gyrus (AG), posterior division of Supramarginal Gyrus (SMGpd), superior division of Lateral Occipital Cortex (LOCsd), and temporo‐occipital part of Middle Temporal Gyrus (MTGtop). In Step 3, we took into account that not all authors in the literature use the label “TPJ” for their findings, so some might be still missing. Therefore, in Step 3 we went back to all papers not mentioning the term “TPJ” and looked for additional coordinates that fell into the atlas structures defined in the step before (i.e., in Step 2). Taking together findings from Steps 2 and 3, we found 109 coordinates that could be labeled as “TPJ” (41 Left, 68 Right). These consisted of 36 coordinates from false belief tasks (18L, 18 R), 32 from social animations (17 L, 15 R) and 41 from attention reorienting tasks (6 L, 35 R). In Step 4, we started our actual probabilistic labeling procedure with the different atlases: For every coordinate, we determined the probability for falling into each area of our probabilistic atlases. This procedure produces multiple probabilities per coordinate—(i.e., one location can be linked to multiple atlas labels with varying probabilities, e.g., the MNI coordinate x = 45, y = 54, z =30 is 15% Angular Gyrus, 7% Supramarginal Gyrus, etc.)

Figure 3.

Illustration of the steps of our review. Step 1: Going through results and discussion sections of individual papers and collect coordinates that are referred to as “TPJ.” Step 2: Looking‐up all coordinates up in a standard gyral atlas (Harvard‐Oxford) and forming an outline of all targeted areas (common denominator of TPJ). Step 3: Going back to papers not mentioning the TPJ and looking for additional coordinates falling into the common denominator structures. Step 4: Carrying out probabilistic labeling with four different atlases. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Statistical Analysis

Atlas labeling

Separately for each task type, we estimated for each atlas area the mean probability of activation (and 95% confidence interval) using percentile bootstrapping analysis [see Efron and Tibshirani, 1993] with 1,000 replicates. Analysis was carried out with the IBM SPSS bootstrapping module (22.0). We used bootstrapping as it is robust in case of small samples and non‐normal data distributions. To evaluate the main questions we laid out in the Introduction, we carried out two analyses. First, we tested for the three task types separately if the mean probability of activation found for each label is different from 0%. This indicates if a label is systematically associated with the activations reported for a task type. The statistical criterion for significance we applied was that the 95% confidence interval of the mean does not include a probability value of 0 (all values were rounded off to whole numbers). This criterion for confidence intervals can be taken to provide the same evidential standard as null hypothesis testing at a 5% significance‐level [Tryon, 2001]. Second, we tested if mean probabilities are significantly different between any two task types which indicates that a label is more strongly associated with activations for one task‐type than the other. We carried out pairwise comparisons where we tested if the 95% confidence intervals of the means were overlapping or not.

Spatial variability

Additionally, we calculated for each coordinate the mean Euclidean distance to all neighbors within the same task type and hemisphere. To test whether the spatial variability differed significantly between the task types, we used the same bootstrap procedure and statistical parameters as for the previous analysis.

Neurosynth Custom Meta‐Analysis

For the discussion of our results, we also carried out neurosynth (http://www.neurosynth.org) custom meta‐analyses for the labels “TPJ,” “pSTS” and “Wernicke's area” (custom meta‐analyses were performed because the default neurosynth meta‐analysis database currently does not cover all of the three terms). We searched the pubmed database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed, October 2016) for all articles mentioning in their title or abstract the terms (i) “temporo‐parietal junction” AND “fmri,” (ii) “posterior superior temporal sulcus” AND “fmri” and (iii) “wernicke's area” AND “fmri.” For each pubmed results list, we searched for all corresponding study entries in the neurosynth database, and created custom meta‐analyses for all found matches. This resulted in (i) a TPJ meta‐analysis (85 studies, neurosynth ID: 24e0f983‐ede4–4c5c), (ii) a pSTS meta‐analysis (97 studies, neurosynth ID: 3d5b8bc7–4eed‐49b8) and (iii) a Wernicke's area meta‐analysis (19 studies, ID: 58aeb86a‐f112–4a17). For results we show reverse inference maps for the three terms (i.e., likelihood that label is used given presence of activity at a given voxel in the brain) at a thresholded of P < 0.01 FDR corrected. Note that for the term Wernicke's area we found considerably fewer studies, and therefore meta‐analytic results should be taken with caution.

RESULTS

For sake of brevity, we only mention findings in the text with an activation probability (or difference in activation probabilities) of 10% or more. However, detailed results are given in Table 1. An overview of all atlases and structures is given in Figure 1B.

Table 1.

Detailed probabilistic labeling results

| False Belief | Social Animations | Attention Reorienting | FB vs. SA | FB vs. AR | SA vs. AR | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | Label | M (%) | 95% CI | M (%) | 95% CI | M (%) | 95% CI | Md (%) | 95% CI | Md (%) | 95% CI | Md (%) | 95% CI |

| Harvard‐Oxford Gyral Atlas | |||||||||||||

| R | AG | 57.5 | [45; 68] | 17.6 | [8; 26] | 20.3 | [14; 27] | 39.9 | [27; 54] | 37.2 | [23; 48] | −2.7 | [‐14; 9] |

| SMG, pd | 1.5 | [1; 2] | 8.4 | [2; 17] | 13.9 | [9; 19] | −6.9 | [‐15; −1] | ‐12.4 | [‐18; −7] | −5.5 | [‐14; 4] | |

| LOC, sd | 13.8 | [5; 25] | 22.3 | [9; 38] | 16.4 | [9; 25] | −8.5 | [‐26; 9] | −2.5 | [‐14; 11] | 6.0 | [‐10; 23] | |

| MTG, top | 4.2 | [1; 8] | 14.5 | [5; 26] | 8.7 | [3; 15] | ‐10.2 | [‐23; −1] | −4.5 | [‐12; 2] | 5.8 | [‐6; 18] | |

| LOC, id | 1.3 | [0; 4] | 0.5 | [0; 1] | 1.6 | [0.4; 4] | 0.7 | [‐1; 0] | −0.3 | [‐3; 3] | −1.1 | [‐3; 0] | |

| STG, pd | 0.0 | 0.3 | [0; 0.7] | 0.3 | [0.3; 1] | −0.3 | [‐1; 0] | −0.3 | [‐1; 0] | 0.0 | [‐0.9; 1] | ||

| L | AG | 26.7 | [17; 37] | 15.1 | [7; 25] | 11.3 | [‐1; 25] | ||||||

| SMG, pd | 4.6 | [2; 9] | 13.3 | [5; 21] | −8.7 | [‐18; −1] | |||||||

| LOC, sd | 36.1 | [24; 49] | 22.4 | [8; 38] | 13.6 | [‐6; 34] | |||||||

| MTG, top | 0.3 | [0;1] | 12.1 | [3; 22] | ‐11.7 | [‐22; −3] | |||||||

| LOC, id | 0.6 | [1; 2] | 2.6 | [0; 6] | −2.0 | [‐5; 1] | |||||||

| STG, pd | 0.2 | [0; 1] | 2.0 | [0; 4] | −1.8 | [‐4; 0] | |||||||

| Sulco‐gyral Atlas in TAL space | |||||||||||||

| R | AG | 21.3 | [14; 29] | 12.8 | [3; 26] | 11.0 | [7; 15] | 8.4 | [‐7; 23] | 10.2 | [2; 19] | 1.8 | [‐8; 15] |

| SMG | 0.3 | [0; 1] | 0.9 | [0; 3] | 4.7 | [2; 8] | −0.6 | [‐2; 1] | −4.4 | [‐8; −2] | −3.8 | [‐8; −1] | |

| SPL | 0.0 | [0; 0] | 0.1 | [0; 0] | 2.5 | [1; 4] | −0.1 | [‐0.4; 0] | −2.5 | [‐5; −1] | −2.4 | [‐5; −1] | |

| STG, lat | 0.0 | [0; 0] | 0.7 | [0; 1] | 1.4 | [0; 3] | −0.7 | [‐1; 0] | −1.4 | [‐3; 0] | −0.7 | [‐2; 1] | |

| MTG | 0.8 | [0; 2] | 2.2 | [0; 7] | 2.6 | [1; 5] | −1.4 | [‐6; 1] | −1.8 | [‐4; 0] | −0.3 | [‐4; 5] | |

| Jens. Sulc. | 1.4 | [1; 2] | 0.1 | [0; 0] | 2.5 | [1; 4] | 1.2 | [1; 2] | −1.1 | [‐3; −1] | −2.4 | [‐4; −1] | |

| IPS | 0.9 | [0; 1] | 3.7 | [0; 9] | 5.3 | [2; 9] | −2.8 | [‐9; 1] | −4.5 | [‐8; −1] | −1.6 | [‐7; 6] | |

| STS | 30.0 | [23; 37] | 27.2 | [13; 40] | 13.6 | [9; 19] | 2.8 | [‐12; 18] | 16.3 | [8; 25] | 13.6 | [‐1; 28] | |

| L | AG | 19.6 | [7; 13] | 11.5 | [5; 21] | 8.1 | [4; 19] | ||||||

| SMG | 2.4 | [1; 4] | 2.0 | [1; 4] | 0.3 | [‐2; 3] | |||||||

| SPL | 0.0 | [0; 0] | 1.8 | [0; 6] | −1.8 | [‐7; −1] | |||||||

| STG, lat | 0.1 | [0; 3] | 7.3 | [3; 13] | −7.2 | [‐13; −2] | |||||||

| MTG | 1.0 | [0; 2] | 15.4 | [6; 26] | ‐14.4 | [‐25; −5] | |||||||

| Jens. Sulc. | 4.3 | [2; 7] | 1.0 | [0; 2] | 3.3 | [1; 6] | |||||||

| IPS | 0.7 | [0; 1] | 0.2 | [0; 1] | 0.5 | [0; 1] | |||||||

| STS | 18.1 | [12; 24] | 7.5 | [4; 13] | 10.6 | [3; 18] | |||||||

| Juelich Histological Atlas | |||||||||||||

| R | PGa | 53.8 | [42; 65] | 12.5 | [5; 20] | 13.5 | [8; 20] | 41.2 | [26; 55] | 40.2 | [27; 54] | −1.0 | [‐10; 8] |

| PGp | 16.7 | [6; 30] | 16.3 | [4; 32] | 6.9 | [1; 14] | 0.3 | [‐18; 22] | 9.8 | [‐3; 24] | 9.5 | [‐5; 25] | |

| PFm | 1.1 | [0; 2] | 3.7 | [0; 11] | 15.7 | [8; 25] | −2.6 | [‐9; 1] | ‐14.6 | [‐23; −6] | ‐12.0 | [‐23; −1] | |

| hIP1 | 3.7 | [2; 6] | 1.3 | [1; 4] | 3.4 | [1; 6] | 2.5 | [‐1; 5] | 0.3 | [‐3; 3] | −2.1 | [‐5; 2] | |

| hIP2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | [1; 7] | 0.0 | −3.1 | [‐6; 0] | −3.1 | [‐6; −1] | ||||

| hIP3 | 0.0 | 2.3 | [2; 7] | 3.5 | [1; 7] | −2.3 | [‐9; −2] | −3.5 | [‐7; −1] | −1.2 | [‐6; 5] | ||

| PF | 0.0 | 0.9 | [1; 3] | 3.1 | [1; 7] | −0.9 | [‐3; −1] | −3.1 | [‐7; −1] | −2.2 | [‐6; 1] | ||

| L | PGa | 29.5 | [21; 38] | 10.5 | [4; 19] | 19.0 | [6; 31] | ||||||

| PGp | 22.2 | [12; 34] | 14.1 | [4; 26] | 8.2 | [‐8; 24] | |||||||

| PFm | 11.9 | [6; 18] | 5.7 | [2; 10] | 6.2 | [‐1; 14] | |||||||

| hIP1 | 1.4 | [0; 3] | 0.4 | [0; 1] | 1.0 | [0; 3] | |||||||

| hIP2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| hIP3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| PF | 2.8 | [0; 7] | 1.8 | [0; 5] | 1.0 | [‐4; 6] | |||||||

| Connectivity‐based parcellation Atlas | |||||||||||||

| R | TPJp | 39.6 | [19; 61] | 19.1 | [6; 40] | 14.2 | [5; 25] | 20.4 | [‐8; 50] | 25.3 | [3; 48] | 4.9 | [‐14; 29] |

| TPJa | 4.2 | [1; 9] | 5.8 | [4; 22] | 11.0 | [4; 20] | −1.6 | [‐15; 8] | −6.9 | [‐16; 2] | −5.2 | [‐18; 11] | |

| IPLB | 11.1 | [5; 18] | 0.0 | 5.7 | [2; 10] | 11.1 | [5; 18] | 5.4 | [‐3; 13] | −5.7 | [‐10; −2] | ||

| IPLC | 8.3 | [3; 14] | 1.7 | [1; 6] | 16.4 | [8; 25] | 6.7 | [0; 13] | −8.0 | [‐19; 2] | ‐14.7 | [‐24; −6] | |

| IPLD | 6.2 | [1; 12] | 6.7 | [3; 17] | 8.9 | [3; 16] | −0.4 | [‐12; 10] | −2.7 | [‐11; 6] | −2.2 | [‐12; 9] | |

| IPLE | 6.2 | [1; 15] | 8.3 | [2; 19] | 11.4 | [5; 19] | −2.1 | [‐14; 10] | −5.2 | [‐15; 7] | −3.0 | [‐14; 10] | |

| SPLA | 0.0 | 2.5 | [2; 9] | 3.9 | [1; 8] | −2.5 | [‐9; −2] | −3.9 | [‐8; −1] | −1.4 | [‐7; 5] | ||

| SPLC | 0.0 | 3.3 | [2; 13] | 5.7 | [1; 11] | −3.3 | [‐13; −2] | −5.7 | [‐11; −1] | −2.4 | [‐10; 7] | ||

| SPLD | 0.0 | 2.5 | [2; 9] | 9.6 | [3; 18] | −2.5 | [‐9; −2] | −9.6 | [‐17; −3] | −7.1 | [‐16; 2] | ||

| SPLE | 0.0 | 2.5 | [2; 9] | 5.0 | [2; 10] | −2.5 | [‐9; −2] | −5.0 | [‐9; −1] | −2.5 | [‐9; 5] | ||

M, Mean probability; CI, Confidence Interval; Md, Mean difference.

Underlined numbers probabilities are above chance level (i.e., confidence intervals do not include 0, rounded to whole numbers). Bold underlined numbers probabilities are above chance level and > 10%, corresponding to main findings reported in the manuscript.

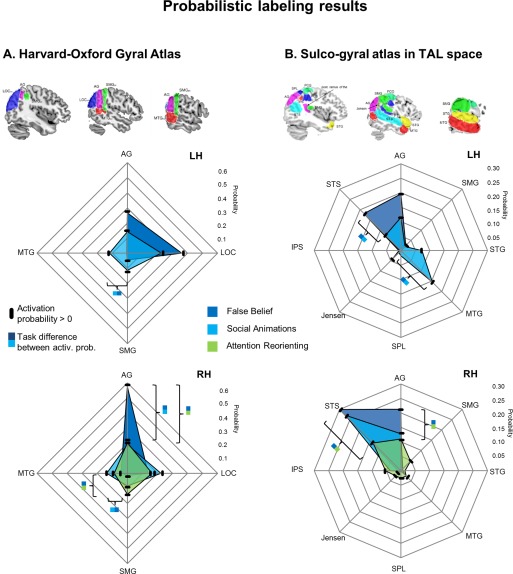

Gyral Anatomy

Results for task types separately

False belief

Dark blue areas in Figure 4A show that activation probabilities were highest in bilateral Angular Gyrus (AG) and bilateral Lateral Occipital Cortex, superior division (LOCsd), see Table 1 for details.

Figure 4.

Results of probabilistic labeling of TPJ activations based on (A) gyral anatomy and (B) sulco‐gyral anatomy. Polar plots show mean activation probabilities (%), that is, the chance that reported peaks are falling into a particular structure. Black dashes indicate that activation probability is significantly above chance for an area. Significant probability differences are only shown if exceeding 10%, for a more detailed report, see Table I. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Social animations

Light blue areas in Figure 4A show that in both hemispheres, activation probabilities were highest in AG, LOCsd and the Middle Temporal Gyrus, temporo‐occipital part (MTGtop). In the left hemisphere, activation probabilities were also high for the Supramarginal Gyrus, posterior division (SMGpd).

Attention reorienting (RH only)

Similar to the pattern for social animations, activation probabilities were highest in right AG, SMGpd and LOCsd.

Task differences

Higher activation probabilities for false belief compared to social animations were found in right AG, see Table 1 for details. In contrast, activation probabilities were higher in bilateral MTGtop for social animations compared to false belief. Higher probabilities for false belief compared to attention reorienting were found in right AG, and the opposite pattern was found in right SMGpd.

Sulco‐Gyral Anatomy

Results for task types separately

False belief

Figure 4B shows that activation probabilities for this task were highest in bilateral Superior Temporal Sulcus (STS) and Angular Gyrus (AG). In the right hemisphere activation probability was slightly higher for the STS, and in the left hemisphere slightly higher for AG.

Social animations

In the right hemisphere, activation probabilities were highest in AG and STS. In the left hemisphere, they were highest in AG and Middle Temporal Gyrus (MTG).

Attention reorienting (RH only)

Activation probabilities were highest in AG and STS.

Task differences

Results of pairwise comparisons in Figure 4B show that false belief tasks had higher activation probability compared to social animations in left STS. The opposite pattern was found in left MTG. False belief compared to attention reorienting showed higher probabilities in right AG and right STS. No differences were found between social animations and attention reorienting.

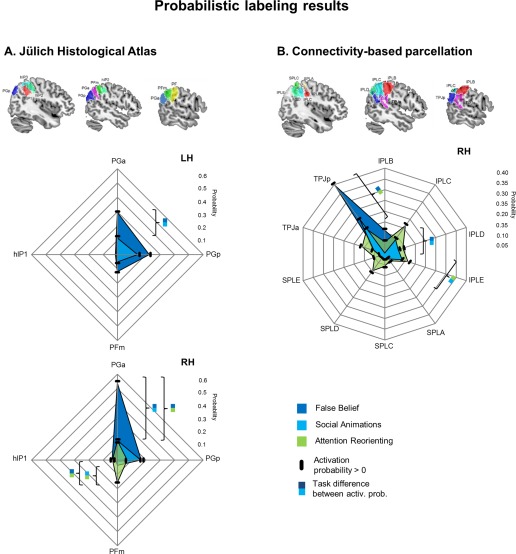

Cytoarchitecture

Figure 1B shows all parietal structures of the Juelich Histological Atlas where we found coordinates labeled as TPJ. To date, a Juelich Histological Atlas for the posterior temporal lobe has not yet been released, so we focus on parietal areas only.

Results for task types separately

False belief

As shown in Figure 5A, most prominent findings were bilateral activation in areas PGp and PGa. On the left side, activation probabilities were also high in area PFm.

Figure 5.

Results of probabilistic labeling of TPJ activations based on (A) cytoarchitecture and (B) a connectivity‐based parcellation. Black dashes indicate that activation probability is significantly above chance for an area. Significant probability differences are only shown if exceeding 10%, for a more detailed report, see Table I. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Social animations

For this task type, activation probabilities were highest in areas PGa and PGp bilaterally.

Attention reorienting

Highest probabilities for attention reorienting were found in PGa and PFm.

Task differences

Results of pairwise comparisons in Figure 5A show that activation probabilities were higher in right PGa for false belief compared to both social animations and attention reorienting. In contrast, attention reorienting had higher probabilities for activations in right PFm compared to both false belief and social animations. In the left hemisphere, probabilities in PGa were higher for false belief compared to social animations.

Connectivity‐Based Parcellation (RH Only)

Probabilistic atlases of white matter connectivity‐based parcellation of the right TPJ [Mars et al., 2012], right IPL and SPL [Mars et al., 2011] were used, see Figure 1B. Mars et al. [2012] defined the outlines of TPJ by the intra‐parietal sulcus (IPS) dorsally, STS ventrally, and MNI coordinates y = −32 and y = −64 on the anterior‐posterior axis. Similarly, the outline of lateral parietal cortex was also based on macroanatomical boundaries.

Results for task types separately

False belief

As shown in Figure 5B, activation probabilities for false belief tasks were highest for the posterior parcellation of TPJ – TPJp, and a more anterior parcellation of the inferior parietal lobule – IPL B.

Social animations

Activation probabilities were again highest for TPJp, see Figure 5B.

Attention reorienting

For this task type, probabilities were highest in TPJp, TPJa, IPL C and IPL E.

Task differences

For connectivity parcellations, we found higher activation probabilities in area TPJp for false belief compared to attention reorienting. Moreover, activation probabilities in IPL B were higher for false belief compared to social animations. Activation probabilities in IPL C were higher for attention reorienting compared to social animations.

Spatial Variability

The spatial variability within task type (mean of the Euclidian distances from each coordinate to all other coordinates in the same hemisphere) differed significantly between false belief, social animations and attention reorienting. The smallest variability was found bilaterally for false belief (RH: M = 9.9, CI = [8.56; 11.76], LH: M = 12.95, CI = [11.77; 14.12]). Social animations showed a significantly higher spatial variability compared to false belief for both left and right TPJ (RH: M = 23.45, CI = [20.68; 26.40], LH: M = 24.33, CI = [21.59; 27.47]). Largest variability was found for attention reorienting, differing significantly from both other task types (RH: M = 28.59, CI = [26.95; 30.27]). Details on spatial variability are given in Supporting Information Table I.

DISCUSSION

We used probabilistic brain atlases to characterize the anatomical basis of brain activation labeled as TPJ. These atlases [Caspers et al., 2006, 2008; Desikan et al., 2006; Destrieux et al., 2010; Mars et al., 2012] are taking into account interindividual variability in anatomy when labeling brain coordinates, which addresses the issue of high interindividual variability in macroanatomy of the TPJ.

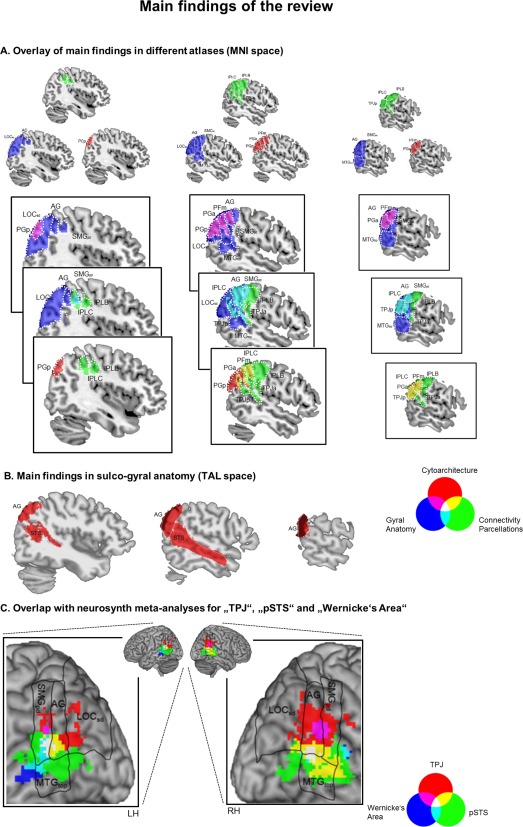

Main Findings of Probabilistic Atlas Labeling

Figure 6A shows right hemispheric areas where we found commonalities or differences in our review, and illustrates the overlap between them for the three MNI‐space atlases we used (gyral‐, cytoarchitecture‐, connectivity‐based parcellation). Figure 6B additionally illustrates main areas identified by the sulco‐gyral atlas (shown separately as provided in TAL space).

Figure 6.

(A) Illustration of the overlap of main findings in different atlases (MNI space). Three columns show overlaps for three different saggital sections. Within each column, areas in purple show the overlap between gyral anatomy (blue) and cytoarchitecture (red), areas in turquoise show the overlap between gyral anatomy (blue) and connectivity‐parcellations (green) and areas in yellow show the overlap between cytoarchitecture (red) and connectivity‐parcellations (green). (B) Main findings in the sulco‐gyral atlas, illustrated in red (TAL space). (C) Overlap between main findings from atlas review in gyral anatomy (black outlines) and neurosynth meta‐analyses for the labels “TPJ” (red), “pSTS” (green) and “Wernicke's Area” (blue). For display purposes, we thresholded the probabilistic atlas maps of connectivity‐parcellations and cytoarchitectonics at 0.50, of gyral‐parcellations at 0.25 and of sulco‐gyral parcellations at 0.20. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Main commonalities

In the gyral atlas, common TPJ activations were mainly assigned to bilateral Angular Gyrus (AG) and the Lateral Occipital Cortex, superior division (LOCsd). In the sulco‐gyral atlas, we found activation mainly in bilateral AG and Superior Temporal Sulcus (STS). The only exception to these findings was little activation in left STS for social animations. In terms of cytoarchitecture, common activation was found in bilateral areas PGp and PGa, in particular for ToM tasks (whereas relatively little activation was found in PGp for attention reorienting). For connectivity‐based parcellations, common activation fell into right TPJp for all task types.

Main differences

Main differences between ToM tasks

In the left hemisphere, TPJ activation for false belief compared to social animations was more strongly linked to area STS in the sulco‐gyral atlas and area PGa in the cytoarchitectonic atlas. In the gyral atlas, we only observed nonsignificant trend in left AG and LOCsd. In the right hemisphere, activation for false belief > social animations was linked to the AG in the gyral atlas, area PGa in the cytoarchitectonic atlas, and IPL B in the connectivity‐based parcellation atlas. In the sulco‐gyral atlas, AG was found for this comparison only as a nonsignificant trend.

In contrast, activation for social animations compared to false belief was linked to right MTG in the gyral atlas, and left MTG in both the gyral and the sulco‐gyral atlas. No such corresponding differences were detected in the other two atlases, which could be due to the facts that (i) both atlases are not covering (all) posterior temporal structures and (ii) the connectivity‐parcellation atlas is only covering the right hemisphere.

Main differences between ToM and attention

TPJ activation for false belief compared to attention reorienting fell more strongly into right AG (gyral and sulco‐gyral atlas) and right STS (sulco‐gyral atlas only). In terms of cytoarchitecture, stronger activations for false belief > attention reorienting fell into right area PGa, and in terms of connectivity‐parcellations to right TPJp. On the other hand, activation for attention reorienting was more closely linked to right SMG in terms of gyral anatomy (compared to false belief), in right area PFm in terms of cytoarchitecture (compared to false belief and social animations) and in right IPLC in terms of connectivity parcellations (compared to social animations).

Sulco‐Gyral Atlas

Our sulco‐gyral atlas findings are of interest, as in ToM research the two labels “TPJ” [e.g., Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003; Schaafsma et al., 2015; Spunt and Adolphs, 2014; Spunt et al., 2016] and “pSTS” [Carringtonand Bailey, 2009; Frith and Frith, 2008, 2003; Lieberman, 2007; Singer, 2006] have been prominently linked to social cognition. In some accounts, TPJ and pSTS were defined as two distinct areas of the ToM/social‐cognition network [see e.g., Adolphs, 2009; Carrington and Bailey, 2009; Gobbini et al., 2007; Koster‐Hale and Saxe, 2013; Saxe et al., 2004; Van Overwalle and Baetens, 2009], while other accounts made a less strong distinction [e.g., Carter and Huettel, 2013; Corbetta et al., 2008; Decety and Lamm, 2007; Heyes and Frith, 2014].

Since most ToM studies used gyral brain parcellations for labeling, they did not distinguish between the pSTS and surrounding gyri. One recent exception is a study by Deen et al. [2015], where a surface‐based analysis of single‐subject fMRI data was performed. The authors could show an anterior–posterior organization of the STS for different social tasks. The most posterior part of STS, adjacent to the IPL, showed selective activation for a ToM task (false belief) compared to other social but non‐ToM tasks studied. Results from our review are consistent with this aspect of Deen et al.'s [2015] findings, as we also show that a considerable part of activation coordinates for false belief tasks fall into STS bilaterally.

With respect to the two ToM tasks we analyzed in our review, previous researchers linked activity for social animations to “pSTS” and activity for false belief to “TPJ” [Bahnemann et al., 2010; Gobbini et al., 2007; Saxe, 2010]. Interestingly, we found equally high probabilities of activation in right STS for both tasks, and only a nonsignificant trend was found in right Angular Gyrus (AG) for false belief > social animations (in the sulco‐gyral atlas). However, when considering a gyral atlas (i.e., leaving out sulcal information), this difference in right AG reached significance. In the left hemisphere, we found higher activation probability for false belief compared to social animations in the STS. However, the opposite task‐difference was found in left middle temporal gyrus (MTG), an area lying just lateral/ventral to the STS in the sulco‐gyral atlas.

Cytoarchitecture and Connectivity‐Based Parcellation Atlases

Cytoarchitectonic and connectivity‐based parcellation atlases provide additional information about the functional organization of the TPJ, as both modalities have been found to closely reflect regional information processing. With respect to cytoarchitecture, combined electrophysiological and architectonic studies with experimental animals found that response properties of neurons change at the border between cytoarchitectonic areas [e.g., Luppino et al., 1991]. With respect to connectivity, studies showed that single‐subject connectivity patterns from diffusion weighted imaging [Osher et al., 2016; Saygin et al., 2012, 2016] and resting‐state fMRI [Tavor et al., 2016] predict if an area is activated during task‐based fMRI on a voxel‐by‐voxel level; this finding that was replicated across several cognitive (task) domains. Connectivity‐based parcellations have been found recently not only within the TPJ [Bzdok et al., 2013b; Mars et al., 2012, 2013], but also within several other areas of the social brain, such as the medial prefrontal cortex [Bzdok et al., 2013a; Eickhoff et al., 2016; Neubert et al., 2015; Sallet et al., 2013], posterior medial cortex/precuneus [Bzdok et al., 2015; Margulies et al., 2009], and the inferior parietal lobule [Bzdok et al., 2016; Wang, et al., 2016, 2017].

In terms of cytoarchitectonics and connectivity‐based parcellations, we found that right PGa/TPJp was particularly strongly linked to false belief tasks, whereas attention reorienting was more strongly linked to right PFm/IPLC. Mars et al. [2012] and Bzdok et al. [2013b] found that TPJp is primarily connected to inferior parietal areas, precuneus, medial prefrontal cortex and middle temporal gyrus. Using meta‐analytic decoding, Bzdok et al. [2013b] further showed that TPJp's connectivity network is mainly engaged in the cognitive domains ToM, memory encoding and episodic memory retrieval. This supports the idea that part of TPJ's functioning in ToM builds on a process shared with episodic memory retrieval, as put forward in accounts of the areas function in terms of self‐projection [Bucknerand Carroll, 2007; Spreng et al., 2009] or processing of internally generated information [Bzdok et al., 2013b; see also Kanske et al., 2015]. Results from the present review suggest that this common process hosted by TPJp is more strongly linked to false belief tasks than the other tasks in our review (attention reorienting and social animations—although only as a nonsignificant trend for the latter).

Relation to Other Labels for Parietal and Posterior Temporal Activations

In Figure 6C we illustrate the relation between key areas found in our review (for the gyral atlas) and neurosynth meta‐analysis maps for the labels “TPJ,” “pSTS” and “Wernicke's area.” For the neurosynth map of TPJ, we focus on results in the right hemisphere.2 Outlines of the four atlas labels identified in our review (black lines in Figure 6C) are in good correspondence to neuroynth maps for the label TPJ (red) and the intersection of labels TPJ and pSTS (yellow). This shows how findings from our review generalize beyond the studied task types, as neurosynth meta‐analyses cover functional imaging studies of all topics that contain the terms “TPJ” or “pSTS” in their abstract/title. However, our labeling review found that only AG and LOCsd were characterized by common activation for all task types, whereas SMGpd and MTGtop showed task related activity differences (right SMGpd: attention > false belief, bilateral MTGtop: social animations > false belief).

Furthermore, we explored the neurosynth map for the term “Wernicke's area,” which is another important functional label for lateral posterior activations. For this term, the left hemisphere is of central interest.3 Figure 6C shows that activation for Wernicke's area overlapped with activation for pSTS alone (shown in turquoise) as well as activation for both TPJ and pSTS (which is shown in white). These findings are in line with results from a recent meta‐analytic coactivation and connectivity‐parcellation analysis [Bzdok et al., 2016], which found that two ventral subareas of the left inferior parietal lobule show convergent activation for social cognition and language tasks. Furthermore, functional decoding of these findings suggested a potential common role of complex semantic processing in the two cognitive domains.

CONCLUSION

Our analysis found that brain activity labeled by the term “TPJ” is linked to specific atlas areas in both hemispheres—and not randomly or unsystematically distributed across parietal and posterior temporal lobes. To illustrate with an example, in a gyral atlas [Desikan et al., 2006] the majority of reported “TPJ” activations fall either in Angular Gyrus or the superior division of the Lateral Occipital Cortex. Moreover, we found that “TPJ” activations systematically fall in distinct atlas areas for different task types. Taken together, these findings suggest that adding neuroanatomical labels to functional activations under the broad term “TPJ” (for both hemispheres) can reveal systematic and meaningful differences, not only in terms of brain macroanatomy, but also connectivity‐based parcellations and cytoarchitecture. As these areal properties are important determinants of functional specialization [e.g., connectivity‐patterns: Osher et al., 2016; Saygin et al., 2016, cytoarchitecture: Luppino et al., 1991], we conclude that using such atlas information for labeling and discussing findings around the TPJ is a powerful tool for refining functional accounts of the area—both within and across different study fields. The present atlas mappings of functional activations found for ToM can serve as a reference for future imaging studies, enabling a comparison of new imaging findings to a neuroanatomical description of ToM. The atlases used for the present review are freely available in FSL (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslview/) and AFNI (https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni/) software.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rutvik Desai for supporting us in using the 3D transformed sulco‐gyral atlas TT_desai_ddpmaps, and Benjamin Kubit and Anthony Jack for sharing the coordinate data underlying the meta‐analysis of attention reorienting reported in Kubit and Jack [2013].

Footnotes

Note that while all atlases in our review are “probabilistic” in the sense that they explicitly measured interindividual variability in brain structure, they are based on different sources of neurobiological evidence and analysis approaches for generating underlying maps in individuals (e.g., observer independent microstructural analysis for cytoarchitectonic maps; see Schleicher et al., 1999; for review Amunts et al., 2007).

Note that the term TPJ commonly refers to activation in the right hemisphere, and thus contralateral (i.e., LH) activations found in the neurosynth map may reflect coactivations reported in studies that focused on right TPJ (and not “left TPJ”).

While neurosynth meta‐analyses show bilateral activation for the terms TPJ, pSTS and Wernicke's area, we focus on the RH for TPJ and the LH for Wernicke's area. pSTS can be linked to both hemispheres.

REFERENCES

- Adolphs R (2009): The social brain: neural basis of social knowledge. Annu Rev Psychol 60:693–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Schleicher A, Bürgel U, Mohlberg H, Uylings HBM, Zilles K (1999): Broca's region revisited: Cytoarchitecture and inter‐subject variability. J Comp Neurol 412:319–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Schleicher A, Zilles K (2007): Cytoarchitecture of the cerebral cortex–more than localization. NeuroImage 37:1061–1065. discussion 1066–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahnemann M, Dziobek I, Prehn K, Wolf I, Heekeren HR (2010): Sociotopy in the temporoparietal cortex: Common versus distinct processes. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 5:48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Desai RH, Graves WW, Conant LL (2009): Where is the semantic system? A critical review and meta‐analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex 19:2767–2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanke O, Ortigue S, Landis T, Seeck M (2002): Stimulating illusory own‐body perceptions. Nature 419:269–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Carroll DC (2007): Self‐projection and the brain. Trends Cogn Sci 11:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdok D, Schilbach L, Vogeley K, Schneider K, Laird AR, Langner R, Eickhoff SB (2012): Parsing the neural correlates of moral cognition: ALE meta‐analysis on morality, theory of mind, and empathy. Brain Struct Funct 217:783–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdok D, Langner R, Schilbach L, Engemann DA, Laird AR, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB (2013a): Segregation of the human medial prefrontal cortex in social cognition. Front Hum Neurosci 7:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdok D, Langner R, Schilbach L, Jakobs O, Roski C, Caspers S, Laird AR, Fox PT, Zilles K, Eickhoff SB (2013b): Characterization of the temporo‐parietal junction by combining data‐driven parcellation, complementary connectivity analyses, and functional decoding. NeuroImage 81:381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdok D, Heeger A, Langner R, Laird AR, Fox PT, Palomero‐Gallagher N, Vogt BA, Zilles K, Eickhoff SB (2015): Subspecialization in the human posterior medial cortex. NeuroImage 106:55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdok D, Hartwigsen G, Reid A, Laird AR, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB (2016): Left inferior parietal lobe engagement in social cognition and language. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 68:319–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington SJ, Bailey AJ (2009): Are there theory of mind regions in the brain? A review of the neuroimaging literature. Hum Brain Mapp 30:2313–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RM, Huettel SA (2013): A nexus model of the temporal‐parietal junction. Trends Cogn Sci 17:328–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S, Geyer S, Schleicher A, Mohlberg H, Amunts K, Zilles K (2006): The human inferior parietal cortex: Cytoarchitectonic parcellation and interindividual variability. NeuroImage 33:430–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S, Eickhoff SB, Geyer S, Scheperjans F, Mohlberg H, Zilles K, Amunts K (2008): The human inferior parietal lobule in stereotaxic space. Brain Struct Funct 212:481–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S, Eickhoff SB, Rick T, von Kapri A, Kuhlen T, Huang R, Shah NJ, Zilles K (2011): Probabilistic fibre tract analysis of cytoarchitectonically defined human inferior parietal lobule areas reveals similarities to macaques. NeuroImage 58:362–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S, Schleicher A, Bacha‐Trams M, Palomero‐Gallagher N, Amunts K, Zilles K (2013): Organization of the human inferior parietal lobule based on receptor architectonics. Cereb Cortex 23:615–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli F, Happé F, Frith U, Frith C (2000): Movement and mind: a functional imaging study of perception and interpretation of complex intentional movement patterns. Neuroimage 12:314–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CD, Stokes MG, Mattingley JB (2004): Modality‐specific control of strategic spatial attention in parietal cortex. Neuron 44:925–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Shulman GL (2002): Control of goal‐directed and stimulus‐driven attention in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 3:201–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Patel G, Shulman GL (2008): The reorienting system of the human brain: From environment to theory of mind. Neuron 58:306–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI (1999): Cortical surface‐based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage 9:179–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Lamm C (2007): The role of the right temporoparietal junction in social interaction: How low‐level computational processes contribute to meta‐cognition. Neuroscientist 13:580–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deen B, Koldewyn K, Kanwisher N, Saxe R (2015): Functional Organization of Social Perception and Cognition in the Superior Temporal Sulcus. Cereb Cortex 25:4596–4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny BT, Kober H, Wager TD, Ochsner KN (2012): A meta‐analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of self‐ and other judgments reveals a spatial gradient for mentalizing in medial prefrontal cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 24:1742–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Killiany RJ (2006): An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage 31:968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destrieux C, Fischl B, Dale A, Halgren E (2010): Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. NeuroImage 53:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JT, Poldrack RA (2007): In praise of tedious anatomy. NeuroImage 37:1033–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B. , Tibshirani, R. (1993) An Introduction to the Bootstrap. London: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Stephan KE, Mohlberg H, Grefkes C, Fink GR, Amunts K, Zilles K (2005): A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. NeuroImage 25:1325–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Thirion B, Varoquaux G, Bzdok D (2015): Connectivity‐based parcellation: Critique and implications. Hum Brain Mapp 36:4771–4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Fox PT, Bzdok D, Hensel L (2016): Functional segregation of the human dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 26:304–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM (1999): Cortical surface‐based analysis. II: Inflation, flattening, and a surface‐based coordinate system. NeuroImage 9:195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD, Frith U (2008): Implicit and explicit processes in social cognition. Neuron 60:503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U, Frith CD (2003): Development and neurophysiology of mentalizing. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B Biol Sci 358:459–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng JJ, Vossel S (2013): Re‐evaluating the role of TPJ in attentional control: Contextual updating? Neurosc Biobehav Rev 37:2608–2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbini MI, Koralek AC, Bryan RE, Montgomery KJ, Haxby JV (2007): Two takes on the social brain: A comparison of theory of mind tasks. J Cogn Neurosci 19:1803–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henssen A, Zilles K, Palomero‐Gallagher N, Schleicher A, Mohlberg H, Gerboga F, Eickhoff SB, Bludau S, Amunts K (2016): Cytoarchitecture and probability maps of the human medial orbitofrontal cortex. Cortex 75:87–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes CM, Frith CD (2014): The cultural evolution of mind reading. Science 344:1243091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igelström, KM , Webb TW, Graziano MS (2015): Neural processes in the human temporoparietal cortex separated by localized independent component analysis. J Neurosci 35:9432–9445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igelström KM, Webb TW, Kelly YT, Graziano MS (2016): Topographical organization of attentional, social, and memory processes in the human temporoparietal cortex. eNeuro 3:e0060–e16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen‐Berg H, Behrens TE, Robson MD, Drobnjak I, Rushworth MF, Brady JM, Smith SM, Higham DJ, Matthews PM (2004): Changes in connectivity profiles define functionally distinct regions in human medial frontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:13335–13340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanske P, Böckler A, Trautwein FM, Singer T (2015): Dissecting the social brain: Introducing the EmpaToM to reveal distinct neural networks and brain‐behavior relations for empathy and theory of mind. NeuroImage 122:6–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster‐Hale J, Saxe R (2013): Theory of mind: A neural prediction problem. Neuron 79:836–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krall SC, Rottschy C, Oberwelland E, Bzdok D, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB, Fink GR, Konrad K (2015): The role of the right temporoparietal junction in attention and social interaction as revealed by ALE meta‐analysis. Brain Struct Funct 220:587–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krall SC, Volz LJ, Oberwelland E, Grefkes C, Fink GR, Konrad K (2016): The right temporoparietal junction in attention and social interaction: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Hum Brain Mapp 37:796–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krönlein, R. U. (1886). Über die Trepanation bei Blutungen aus der A. meningea media und geschlossener Schädelkapsel. Deutsch Zeitschr f Chir 23(3–4):209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kubit B, Jack AI (2013): Rethinking the role of the rTPJ in attention and social cognition in light of the opposing domains hypothesis: Findings from an ALE‐based meta‐analysis and resting‐state functional connectivity. Front Hum Neurosci 7:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm C, Decety J, Singer T (2011): Meta‐analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. NeuroImage 54:2492–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster JL, Tordesillas‐Gutierrez D, Martinez M, Salinas F, Evans A, Zilles K, Mazziotta JC, Fox PT (2007): Bias between MNI and Talairach coordinates analyzed using the ICBM‐152 brain template. Hum Brain Mapp 28:1194–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, McCarthy G (2016): Functional heterogeneity and convergence in the right temporoparietal junction. Cereb Cortex 26:1108–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebenthal E, Desai RH, Humphries C, Sabri M, Desai A (2014): The functional organization of the left STS: A large scale meta‐analysis of PET and fMRI studies of healthy adults. Front Neurosci 8:289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD (2007): Social cognitive neuroscience: A review of core processes. Annu Rev Psychol 58:259–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppino G, Matelli M, Camarda RM, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G (1991): Multiple representations of body movements in mesial area 6 and the adjacent cingulate cortex: An intracortical microstimulation study in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol 311:463–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar RA (2011): The neural bases of social cognition and story comprehension. Annu Rev Psychol 62:103–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies DS, Vincent JL, Kelly C, Lohmann G, Uddin LQ, Biswal BB, Villringer A, Castellanos FX, Milham MP, Petrides M (2009): Precuneus shares intrinsic functional architecture in humans and monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:20069–20074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars RB, Jbabdi S, Sallet J, O'Reilly JX, Croxson PL, Olivier E, Noonan MP, Bergmann C, Mitchell AS, Baxter MG, Behrens TE, Johansen‐Berg H, Tomassini V, Miller KL, Rushworth MF (2011): Diffusion‐weighted imaging tractography‐based parcellation of the human parietal cortex and comparison with human and macaque resting‐state functional connectivity. J Neurosci 31:4087–4100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars RB, Sallet J, Schuffelgen U, Jbabdi S, Toni I, Rushworth MF (2012): Connectivity‐based subdivisions of the human right “temporoparietal junction area”: Evidence for different areas participating in different cortical networks. Cereb Cortex 22:1894–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars RB, Sallet J, Neubert FX, Rushworth MF (2013): Connectivity profiles reveal the relationship between brain areas for social cognition in human and monkey temporoparietal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:10806–10811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars RB, Verhagen L, Gladwin TE, Neubert FX, Sallet J, Rushworth MF (2016): Comparing brains by matching connectivity profiles. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 60:90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JP (2008): Activity in right temporo‐parietal junction is not selective for theory‐of‐mind. Cereb Cortex 18:262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenberghs P, Cunnington R, Mattingley JB (2009): Is the mirror neuron system involved in imitation? A short review and meta‐analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33:975–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenberghs P, Johnson H, Henry JD, Mattingley JB (2016): Understanding the minds of others: A neuroimaging meta‐analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 65:276–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mort DJ, Malhotra P, Mannan SK, Rorden C, Pambakian A, Kennard C, Husain M (2003): The anatomy of visual neglect. Brain 126:1986–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RJ, Schaer M, Debbané M (2012): Degrees of separation: A quantitative neuroimaging meta‐analysis investigating self‐specificity and shared neural activation between self‐ and other‐reflection. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 36:1043–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nee DE, Wager TD, Jonides J (2007): Interference resolution: Insights from a meta‐analysis of neuroimaging tasks. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 7:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubert FX, Mars RB, Sallet J, Rushworth MF (2015): Connectivity reveals relationship of brain areas for reward‐guided learning and decision making in human and monkey frontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:E2695–E2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osher DE, Saxe RR, Koldewyn K, Gabrieli JD, Kanwisher N, Saygin ZM (2016): Structural connectivity fingerprints predict cortical selectivity for multiple visual categories across cortex. Cereb Cortex 26:1668–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özdem C, Brass M, Van der Cruyssen L, Van Overwalle F (2017): The overlap between false belief and spatial reorientation in the temporo‐parietal junction: The role of input modality and task. Soc Neurosci 12:207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perner J, Leekam S (2008): The curious incident of the photo that was accused of being false: Issues of domain specificity in development, autism, and brain imaging. Q J Exp Psychol 61:76–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallet J, Mars RB, Noonan MP, Neubert FX, Jbabdi S, O'Reilly JX, Filippini N, Thomas AG, Rushworth MF (2013): The organization of dorsal frontal cortex in humans and macaques. J Neurosci 33:12255–12274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R (2010): The right temporo‐parietal junction: A specific brain region for thinking about thoughts In Leslie A, German T, editors. Handbook of Theory of Mind. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Kanwisher N (2003): People thinking about thinking people. The role of the temporo‐parietal junction in “theory of mind.” NeuroImage 19:1835–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Carey S, Kanwisher N (2004): Understanding other minds: Linking developmental psychology and functional neuroimaging. Annu Rev Psychol 55:87–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saygin ZM, Osher DE, Koldewyn K, Reynolds G, Gabrieli JD, Saxe RR (2012): Anatomical connectivity patterns predict face selectivity in the fusiform gyrus. Nat Neurosci 15:321–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saygin ZM, Osher DE, Norton ES, Youssoufian DA, Beach SD, Feather J, Gaab N, Gabrieli JD, Kanwisher N (2016): Connectivity precedes function in the development of the visual word form area. Nat Neurosci 19:1205–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma SM, Pfaff DW, Spunt RP, Adolphs R (2015): Deconstructing and reconstructing theory of mind. Trends Cogn Sci 19:65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher A, Amunts K, Geyer S, Morosan P, Zilles K (1999): Observer‐independent method for microstructural parcellation of cerebral cortex: A quantitative approach to cytoarchitectonics. NeuroImage 9:165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz J, Triantafyllou C, Whitfield‐Gabrieli S, Brown EN, Saxe R (2009): Distinct regions of right temporo‐parietal junction are selective for theory of mind and exogenous attention. PLoS One 4:e4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurz M, Radua J, Aichhorn M, Richlan F, Perner J (2014): Fractionating theory of mind: A meta‐analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 42:9–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, Petrides M (2012): The morphology and variability of the caudal rami of the superior temporal sulcus. Eur J Neurosci 36:2035–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghier ML (2013): The angular gyrus: Multiple functions and multiple subdivisions. Neuroscientist 19:43–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T (2006): The neuronal basis and ontogeny of empathy and mind reading: Review of literature and implications for future research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30:855–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Lamm C (2009): The social neuroscience of empathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1156:81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim AS (2009): The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: A quantitative meta‐analysis. J Cogn Neurosci 21:489–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprong M, Schothorst P, Vos E, Hox J, van Engeland H (2007): Theory of mind in schizophrenia: Meta‐analysis. Br J Psychiatry 191:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spunt RP, Adolphs R (2014): Validating the Why/How contrast for functional MRI studies of Theory of Mind. NeuroImage 99:301–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spunt RP, Kemmerer D, Adolphs R (2016): The neural basis of conceptualizing the same action at different levels of abstraction. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 11:1141–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenger C (1881): Syphilom des linken Centrum ovale, der rechten Ponshälfte. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 11:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sugranyes G, Kyriakopoulos M, Corrigall R, Taylor E, Frangou S (2011): Autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia: Meta‐analysis of the neural correlates of social cognition. PLoS One 6:e25322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavor I, P, Jones O, Mars RB, Smith SM, Behrens TE, Jbabdi S (2016): Task‐free MRI predicts individual differences in brain activity during task performance. Science 352:216–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryon WW (2001): Evaluating statistical difference, equivalence, and indeterminacy using inferential confidence intervals: An integrated alternative method of conducting null hypothesis statistical tests. Psychol Methods 6:371–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio‐Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M (2002): Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single‐subject brain. NeuroImage 15:273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ, Supekar K, Amin H, Rykhlevskaia E, Nguyen DA, Greicius MD, Menon V (2010): Dissociable connectivity within human angular gyrus and intraparietal sulcus: Evidence from functional and structural connectivity. Cereb Cortex 20:2636–2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC (2005): A population‐average, landmark‐ and surface‐based (PALS) atlas of human cerebral cortex. NeuroImage 28:635–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Overwalle F (2009): Social cognition and the brain: A meta‐analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 30:829–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Overwalle F, Baetens K (2009): Understanding others' actions and goals by mirror and mentalizing systems: A meta‐analysis. NeuroImage 48:564–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang J, Rong M, Wei X, Zheng D, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB, Jiang T (2016): Functional topography of the right inferior parietal lobule structured by anatomical connectivity profiles. Hum Brain Mapp 37:4316–4332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Xie S, Guo X, Becker B, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB, Jiang T (2017): Correspondent functional topography of the human left inferior parietal lobule at rest and under task revealed using resting‐state fMRI and coactivation based parcellation. Hum Brain Mapp 38:1659–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo BT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, Roffman JL, Smoller JW, Zollei L, Polimeni JR, Fischl B, Liu H, Buckner RL (2011): The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 106:1125–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya N, Erel O, Shaked M, Solomonica‐Levi D (1998): Meta‐analyses comparing theory of mind abilities of individuals with autism, individuals with mental retardation, and normally developing individuals. Psychol Bull 124:283–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Camprodon JA, Hauser M, Pascual‐Leone A, Saxe R (2010): Disruption of the right temporoparietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:6753–6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Schleicher A, Langemann C, Amunts K, Morosan P, Palomero‐Gallagher N, Schormann T, Mohlberg H, Burgel U, Steinmetz H, Schlaug G, Roland PE (1997): Quantitative analysis of sulci in the human cerebral cortex: Development, regional heterogeneity, gender difference, asymmetry, intersubject variability and cortical architecture. Hum Brain Mapp 5:218–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlatkina V, Petrides M (2014): Morphological patterns of the intraparietal sulcus and the anterior intermediate parietal sulcus of Jensen in the human brain. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B 281:493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information