Abstract

In this work we report the synthesis of five new nickel(II) complexes all coordinated to the tripodal ligand tris(1-ethyl-4-iPr-imidazolyl)phosphine (TlEt4iPrIP). They are [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(CH3CN)2(OTf)](OTf) (1), [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(OTf)2] (2), [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(H2O)(OTf)](OTf) (3), [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)Cl](OTf) (4), and [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)Cl2] (5). The complexes serve as bioinorganic structural model complexes for histidine-coordinated nickel proteins. The X-ray structures have been determine for all complexes which feature coordination numbers 4-6. We investigated the spectroscopic interconversions for these compound in dichloromethane solution and demonstrate interconversion between 1-3 and conversion of 2 to 4. Complex 5 can be spectroscopically converted to the cation of 4 by dissolving it in dichloromethane. Fits of variable temperature magnetic susceptibility data yielded the following parameters: g = 1.944, D = −0.327 cm−1, E/D = 3.706 for 1; g = 2.280, D = −0.365 cm−1, E/D = 22.178 for 2; g = 2.000, D = −7.402 cm−1, E/D = −0.272 for 3; g = 2.176, D = −0.128 cm−1, E/D = −0.783 for 4; g = 2.258, D = 14.288 cm−1, E/D = 0.095 for 5. DFT structure optimizations afforded HOMO and LUMO energies indicating that complex 1 is the most stable.

Keywords: Nickel(II), Magnetic Susceptibility, Imidazole Ligand, X-ray Crystallography, DFT

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Nickel is an essential cofactor in many microorganism [1]. The known nickel-dependent enzymes are urease, hydrogenase, carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (and CO dehydrogenase/acetyl-coenzyme A synthase), methyl-S-coenzyme M reductase, and one class of superoxide dismutase (SOD) [2]. For the metalloenzymes such as, urease and hydrogenase; nickel(II) is essential for the hydrolysis of urea into carbon dioxide and ammonia and for the consumption of nutrient hydrogen [1,3]. While many of these employ a dinuclear active site to facilitate their catalytic reactions [3], a variety of imidazole-containing ligands have been investigated to mimic these enzymatic structural features [4]. The molecular structures of NikR, from E. coll, NikZ-His from C. jejuni, and NiSOD have revealed N-histidine ligands (Fig. 1) [5,6]. The use of tris(imidazole) ligands which closely mimics the tris(histidine) binding site, have not been extensively explored in modeling nickel-containing active sites [7].

Fig. 1.

Metal binding site of NikR, NikZ-His, and the active site for NiSOD [5, 6].

In this work we report the synthesis and structural determination of five new nickel(II) complexes supported by tris(1-ethyl-4-iPr-imidazolyl)phosphine (T1Et4iPrIP) [8] are discussed. We demonstrate that the featured complexes can be generated by altering the solvent polarity, coordinating ability, solvent dryness, and nickel(II) source. Using this approach we have generated 4-, 5-, and 6-coordinate complexes. The complexes have been characterized by liquid and diffuse reflectance UV-vis spectroscopy, 31P NMR, FTIR, and variable temperature magnetic susceptibility. DFT calculations were also performed to characterize the electronic structure of these complexes.

2. Result and discussion

2.1. Synthesis

The ligand tris(1-ethyl-4-iPr-imidazolyl)phosphine (T1Et4iPrIP) [8] was employed for the synthesis of five new nickel(II) complexes. They are [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(NCCH3)2(OTf)](OTf) (1), [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)2] (2), [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(H2O)(OTf)](OTf) (3), [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(Cl)](OTf) (4) and [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(Cl)2] (5). The synthesis of 1 was accomplished by reacting one equiv of T1Et4iPrIP with Ni(OTf)2·2CH3CN in CH2Cl2 (Scheme 2). Heating this complex under vacuum resulted in loss of the CH3CN ligands and the formation of 2, a 5-ccordinate structure. Addition of one equiv water to 2 in CH2Cl2 yielded 3 whereas 5 was obtained from the reaction of NiCl2 and T1Et4iPrIP (1:1) in acetonitrile. Monochloro nickel(II) complex 4 was prepared either by the addition of one equiv Et4NCl to 2 in CH2Cl2 or addition of one equivalent Ag(OTf) to a dichloromethane solution of 5. Addition of two or more equiv Et4NCl to 2 or 4 in CH2Cl2 yields 4 but not 5.

Scheme 2.

Interconversion of [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)Ln]x+ complexes.

2.2. X-ray crystallography

Crystal parameters and selected bond lengths and angles for compounds 1-5 are given in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The structures for complexes 1-5 were determined by single crystal X-ray crystallography. Complex 1 and 2 crystallizes in the space group whereas complex 3, 4, and 5 crystallizes in P21/n, I213, and P21/c, respectively. The X-ray crystal structure of 1 (Fig. 2) reveal, that the nickel center is bound in a distorted octahedral geometry, where one imidazole nitrogen and one triflate oxygen occupy the axial positions and two imidazole nitrogens and two acetonitrile molecules are situated in the equatorial positions. The asymmetric unit contains two nickel cations, two triflate anions, and four co-crystallized dichloromethane molecules located in general positions. Modeled as disordered over two positions (50:50) are acetonitrile ligands, one coordinated triflate ligand (89:11), one non-coordinating triflate (50:50), and one dichloromethane (78:22). An additional disordered dichloromethane solvent molecule refined best over three positions (71:22:07). The disorder occupancy ratios were due to nearby crystallographic centers. An interaction between the fluorine (F3) of the coordinated triflate and C61 of a solvent dichloromethane is observed at 3.15 Å. An interaction between O2 (from the coordinated triflate) and the carbon atom (C17/C17[ISP]’) of a disordered dichloromethane is seen at 2.912 Å. Furthermore, the terminal carbon of a coordinated acetonitrile molecule (C28) is interacting (3.048 Å) with a disordered fluorine (F4/F4 ′) of a non-coordinating triflate. Complexes 2 (Fig. 3), 3 (Fig. 4), and 5 (Fig. 5) exhibits square pyramidal geometry (τ= 0.14, 0.19, and 0.18, respectively) [9]. The basal plane of the square pyramids are constructed with the two imidazole nitrogen atoms of T1Et4iPrIP and two triflate oxygens (2), two oxygens derived from triflate and water (3), and two chlorides (5). An imidazole nitrogen from T1Et4iPrIP occupies the apical position in all cases. The unit cell of 2 contains one molecule in a general position. A weak interaction between O3 of the coordinated triflate and C23 of an adjacent molecule is observed at 3.206 Å. For complex 3 the asymmetric unit contains one nickel complex, one triflate, and one co-crystallized solvent dichloromethane molecule all in general positions. The solvent molecule is modeled as disordered over two positions (92:08). H-bonding (See Table SI9) is observed featuring interactions between the C2 of the isopropyl substituent and F1 of a non-coordinating triflate (3.130 Å), C2 and the coordinated water O7 (3.200 Å), O7 and O2 of the coordinating triflate (2.704 Å), O7 and O4 of the non-coordinating triflate (2.659 Å), C10 of the isopropyl substituent and O1 of a coordinating triflate (3.166 Å), and O3 of a coordinating triflate and C27/C27’ of a dichloromethane molecule (3.162 Å /3.06 Å). Complex 4 (Fig. 6), on the other hand exhibits tetrahedral geometry with three nitrogen ligands derived from T1Et4iPrIP and one chloride. The asymmetric unit contains one-third of the nickel ions and one-third of the triflate counterions. Both species lie along a crystallographic three-fold axis that includes Ni1, Cl1, S1, and C9. No short range interactions are observed between the cations and anions. In complex 5, the atoms of the molecules in the unit cell are located in general positions. One of the ethyl moieties is modeled as disordered over two positions (80:20). A second site containing acetonitrile was found to be disordered over a crystallographic inversion center (50:50). The solvent in this site was also refined for occupancy and it was determined that this did not match the disorder so it is likely that there are small voids in the structure part of the time. The Ni–Cl bond length for 4 is 2.173 Å whereas the average Ni–Cl bond lenghth for distorted square pyramidal bis-chloro nickel complex (5) is 2.344 Å. These bond distances are in-line with other known Ni–Cl bond distances [10–15]. The Ni-NIm bond lengths for 1–5 falls in the range 1.999-2.153 Å, which is quite similar to the other reported nickel complexes coordinated with imidazole nitrogen [7, 9, 11, 13, 16–28]. The Ni-Owater bond distance in 3 is in accord with other nickel(II) complexes possessing a water ligand [7, 16, 22, 25, 27–29].

Table 1.

:Crystallographic data and refinement parameters for [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(NCCH3)2(OTf)](OTf) (1), [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)2] (2), [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(H2O)(OTf)][OTf](3), [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(Cl)](OTf) (4) and [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(Cl)2] (5)

| Compound | 1·2CH2Cl2 | 2 | 3·CH2Cl2 | 4 | 5·1.24(CH3CN) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Formula | C32H49Cl4F6N8NiO6PS2 | C26H39F6N6NiO6PS2 | C27H43Cl2F6N6NiO7PS2 | C25H39ClF3N6NiO3PS | C26.49 H42.74 C12N7.24 NiP | ||

| Formula weight | 1051.39 | 799.43 | 902.37 | 685.81 | 623.34 | ||

| Temp. [K] | 100.0(5) | 100.0(10) | 100.0(5) | 100.0(5) | 100.0(1) | ||

| Wavelength [Å] | 0.71073 | 1.54184 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | ||

| Cryst. System | Triclinic | Triclinic | Monoclinic | cubic | Monoclinic | ||

| Space group | P21/n | I213 | P21/c | ||||

| a [Å] | 12.5023(9) | 9.5027(10) | 14.4507(12) | 18.6158(17) | 16.0759(13) | ||

| b [Å] | 12.7779(9) | 9.9167(10) | 16.0144(14) | 18.6158(17) | 13.5765(11) | ||

| c [Å] | 30.466(2) | 18.2890(10) | 18.6223(16) | 18.6158(17) | 15.1139(12) | ||

| α [°] | 99.996(2) | 86.3170(10) | 90 | 90 | 90 | ||

| β [°] | 99.632(2) | 81.4240(10) | 112.3175(15) | 90 | 108.032 (2) | ||

| γ [°] | 98.901(2) | 88.0790(10) | 90 | 90 | 90 | ||

| Volume [Å3] | 4640.2(6) | 1700.18(3) | 3986.7(6) | 6451.3(18) | 3136.7(4) | ||

| Z | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | ||

| Dcalc [Mg/m3] | 1.505 | 1.562 | 1.503 | 1.412 | 1.320 | ||

| Cryst. Size[mm3] | 0.28 × 0.14 × 0.08 | 0.26 × 0.12 × 0.08 | 0.40 × 0.40 × 0.14 | 0.36 × 0.36 × 0.36 | 0.24 × 0.18 × 0.08 | ||

| Reflns. Collected | 73114 | 41890 | 102799 | 68364 | 58211 | ||

| Observed reflns. | 15062 | 6879 | 11272 | 4621 | 8123 | ||

| GOF | 1.029 | 1.071 | 1.010 | 1.038 | 1.037 | ||

| Final R | R1= 0.0598, | R1= 0.0299, | R1= 0.0441, | R1= 0.0428, | R1= 0.0577, | ||

| indices[I>2σ(I)] | wR2= 0.1274 | wR2= 0.0775 | wR2= 0.0934 | wR2= 0.0846 | wR2= 0.1232 | ||

Table 2.

: Selected Bond distances (Å) and Angles (°) for [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(CH3CN)2(OTf)](OTf) (1), [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)2] (2), [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(H2O)(OTf)](OTf) (3), [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(Cl)](OTf) (4) and [Ni(TlEt4iPrIP)(Cl)2] (5)

| Distances | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| Ni(1)–N(1) | 2.106(3) [2.112] | Ni(1)–N(7) | 2.081(3) [2.080] |

| Ni(1)–N(2) | 2.086(3) [2.108] | Ni(1)–N(8) | 2.084(3) [2.081] |

| Ni(1)–N(3) | 2.099(3) [2.113] | Ni(1)–O(1) | 2.182(2) [2.099] |

| 2 | |||

| Ni(1)–N(1) | 2.0465(12) [2.071] | Ni(1)–O(1) | 2.0205(10) [2.170] |

| Ni(1)–N(3) | 2.0927(12) [2.154] | Ni(1)–O(4) | 2.1166(10) [2.060] |

| Ni(1)–N(5) | 2.0424(12) [2.070] | ||

| 3 | |||

| Ni(1)–N(1) | 2.0513(14) [2.031] | Ni(1)–O(1) | 2.0897(12) [1.986] |

| Ni(1)–N(3) | 2.0557(14) [2.075] | Ni(1)– O(7) | 2.0118(13) [2.066] |

| Ni(1)–N(5) | 2.0161(14) [2.019] | ||

| 4 | |||

| Ni(1)–N(1) | 1.9996(19) [1.989] | Ni(1)–N(1)#2 | 1.9997(19) [1.990] |

| Ni(1)–N(1)#1 | 1.9997(19) [1.990] | Ni(1)–Cl(1) C | 2.1731(11) [2.171] |

| 5 | |||

| Ni(1)–N(1) | 2.153(2) [2.296] | Ni(1)–Cl(1) | 2.3050(7) [2.259] |

| Ni(1)–N(2) | 2.026(2) [2.015] | Ni(1)–Cl(2) | 2.3830(7) [2.379] |

| Ni(1)–N(3) | 2.080(2) [2.045] | ||

| Angles | |||

| 1 | |||

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(2) | 89.16(10) [90.19] | N(2)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 178.26(10) [179.22] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(3) | 91.08(10) [90.22] | N(3)–Ni(1)–N(7) | 90.69(11) [91.97] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(7) | 177.77(11) [177.41] | N(3)–Ni(1)–N(8) | 173.68(11) [177.46] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(8) | 92.91(10) [91.65] | N(3)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 88.78(10) [90.13] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 89.44(10) [90.51] | N(7)–Ni(1)–N(8) | 85.22(11) [86.13] |

| N(2)–Ni(1)–N(3) | 90.22(11) [90.24] | N(7)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 89.24(10) [88.09] |

| N(2)–Ni(1)–N(7) | 92.20(11) [91.20] | N(8)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 86.36(10) [88.14] |

| N(2)–Ni(1)–N(8) | 94.74(11) [91.48] | ||

| 2 | |||

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(3) | 85.99(5) [86.09] | N(3)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 94.91(4) [97.37] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(5) | 103.27(5) [102.76] | N(3)–Ni(1)–O(4) | 175.89(4) [169.16] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 156.46(5) [162.30] | N(5)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 100.24(5) [94.84] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–O(4) | 90.15(4) [87.92] | N(5)–Ni(1)–O(4) | 88.99(4) [87.24] |

| N(3)–Ni(1)–N(5) | 90.51(5) [85.28] | O(l)–Ni(1)–O(4) | 89.20(4) [91.06] |

| 3 | |||

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(3) | 88.23(5) [88.80] | N(3)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 93.32(5) [92.67] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(5) | 96.64(6) [96.46] | N(3)–Ni(1)–O(7) | 169.66(6) [173.26] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 158.35(5) [145.02] | N(5)–Ni(1)–O(1) | 104.88(5) [118.39] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–O(7) | 89.53(6) [87.80] | N(5)–Ni(1)–O(7) | 98.43(6) [98.24] |

| N(3)–Ni(1)–N(5) | 91.85(50) [91.93] | O(1)–Ni(1)–O(7) | 85.09(6) [86.79] |

| 4 | |||

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(1)#1 | 92.77(7) [93.08] | N(1)#l–Ni(1)–N(1)#2 | 92.77(7) [92.96] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(1)#2 | 92.77(7) [92.92] | N(1)#1–Ni(1)–CL(1) | 123.28(5) [123.07] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–Cl(1) | 123.28(5) [123.11] | N(1)#2–Ni(1)–Cl(1) | 123.28(5) [123.19] |

| 5 | |||

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(2) | 91.90(9) [86.20] | N(2)–Ni(1)–Cl(1) | 104.13(6) [116.89] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–N(3) | 82.51(8) [81.48] | N(2)–Ni(1)–Cl(2) | 96.57(6) [90.49] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–Cl(1) | 93.14(6) [94.82] | N(3)–Ni(1)–Cl(1) | 160.39(6) [144.76] |

| N(1)–Ni(1)–Cl(2) | 169.18(6) [167.33] | N(3)–Ni(1)–Cl(2) | 90.01(6) [86.88] |

| N(2)–Ni(1)–N(3) | 95.15(8) [97.92] | Cl(1)–Ni(1)–Cl(2) | 91.31(2) [97.58] |

Fig. 2.

Thermal ellipsoid plot of [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(CH3CN)2(OTf)]+ (Cation of 1). H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Fig. 3.

Thermal ellipsoid plot of [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)2] (2). H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Fig. 4.

Thermal ellipsoid plot of [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)(H2O)]+ (Cation of 3). H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Fig. 5.

Thermal ellipsoid plot of [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)Cl2] (5). H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Fig. 6.

Thermal ellipsoid plot of [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)Cl]+ (Cation of 4). H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Complex 1 is the first example of an octahedral Ni complex where nickel is bonded with a tripodal imidazolyl ligand containing coordinated acetonitrile molecule and a triflate group. Kunz et al. [9] synthesized a tetrahedral nickel complexes with a different tripodal imidazolyl phosphine ligand (the phosphorus-carbon linkage is different compared to T1Et4iPrIP) and a chloride atom but they were unable to obtain a publishable crystal structure therefore we are the first to report the crystal structure tetrahedral nickel complex 4 supported by a trisimidazolylphosphine ligand. Complex 2 is also the first example of the distorted square pyramidal nickel complex supported by this type of ligand where two triflates ligands are satisfying the coordination sphere. Kunz et al. [9] was first to report the five coordinated distorted square pyramidal water and chloride coordinated nickel complexes whereas 3 is made with water, a triflate group, and T1Et4iPrIP. Complex 5 is also the first example of a distorted square pyramidal nickel complex with a tripodal imidazolylphosphine ligand where two chlorides are bonded to the nickel center.

2.3. Electronic absorption spectroscopy and solvato-chromic effect

The UV-vis spectra for complexes 1-5 were measured in CH2Cl2. The complexes exhibit bands between 330 nm and 920 nm. The extinction coefficients of the bands support their respective d-d nature [3, 9, 26, 29]. According to Scheme 2, most compounds reported in this study can be derived from 2. To investigate the spectroscopic transformation of 2 into 1, 3, and 4, we titrated 2 with acetonitrile, water, and chloride, respectively. The results are displayed in Figs. 7–9. The optical spectrum of 2 in CH2Cl2 shows a band at 713 (25) and 864 nm (16) with shoulders at 470 (41) and 520 nm (16). Addition of 0.3 equiv CH3CN results in a shift of the 713 band to 691 and a decrease of intensity for the 864 band. Further addition of CH3CN resulted in a decrease of both and 691 and 864 nm bands. The species formed after the addition of one equiv CH3CN is predicted to be [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(CH3CN)(OTf)2] (Species A, Fig. 7). The continued addition of CH3CN results in the smooth conversion of the first species into a second species (B) with isosbestic points observed at 580 and 640 nm. These results may be explained as formulating species B to be [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(CH3CN)2(OTf)]+ (cation of 1) while species C results after the addition of excess CH3CN and is predicted to be [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(CH3CN)3]2+. The UV-vis spectrum of 1 in CH2Cl2 matches species B.

Fig. 7.

UV-vis spectrum of 2 in CH2Cl2 titrated with CH3CN at 0.3, 1.0, 2.0, 2.5, 5, and 13 equiv increments. Species A-C are predicted to be [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(CH3CN)(OTf)2], [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(CH3CN)2(OTf)]+, and [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(CH3CN)3]2+, respectively.

Fig. 9.

UV-vis spectrum of 2 in CH2Cl2 titrated with Et4NCl at 0.1 equiv increments.

The addition of 1.4 equiv of water to 2 in CH2Cl2 results in the initial formation of [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)(H2O)]+ (cation of 3, Fig. 8). Further addition of water results in a decrease in the absorption band intensity located at 697 nm with a slight shift to higher energy (686 nm). Such a behavior could be explained by additional coordination of water to yield [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)(H2O)2]+. The lower extinction coefficient is consistent with a more symmetrical coordination geometry. The last spectrum in the series contains 4.7 equiv of water so this suggests that OTf− is not displaced in the presence of excess water, a result that would lead to a more polar product [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(H2O)2]2+in a relatively low polarity solvent.

Fig. 8.

UV-vis spectrum of 2 in CH2Cl2 titrated with H2O at 1.4, 2.4, 3.5, 4.7 equiv increments.

We also spectroscopically followed the addition of chloride to 2 in CH2Cl2 to determine of complexes 4 and 5 could be sequentially generated (Fig. 9). In this study, 2 was titrated with Et4NCl dissolved in CH2Cl2. The addition of Et4NCl in 0.1 equiv increments (up to 1 equiv) to 2 is shown in Fig. 9. The addition of more than 1 equiv of chloride resulted in no further change to the spectrum indicating that further coordination of chloride to the nickel center is not observed. This result is consistent with the fact that the absorption spectrum of 5 in CH2Cl2 is identical to 4. The implications are that the distorted tetrahedral structure of 4 is more stable in solution. The stability of 5 compared to 4 was investigated using DFT (see below).

We have also performed diffuse reflectance UV-vis spectroscopy on complexes 1-5 and the results are shown in Fig. 10. The spectra clearly show different wavelength maxima for each of the different complexes. In particular, it should be noted that [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)Cl2] (5) exhibits a λmax at 600 nm and 384 nm with shoulders at 543 nm, 476 nm, and 340 nm. Since we observe that 5 is converted to 4 in CH2Cl2 solution, we do not have a solution spectrum to compare it with. Complex 4, on the other hand, exhibits bands similar to the solution spectrum but with different relative intensity. For instance, in powder form, 4 possesses bands at 350, 422, 518 (sh), 600 (sh), and 657 nm. In CH2Cl2 solution, 4 has bands at 378, 472, 551 (sh), 806, and 916 nm (sh) so there is some correspondence. The diffuse reflectance spectrum for the aqua complex, 3, exhibits bands at 350, 438 (sh), 551, and 786 nm. The band at 551 nm appears to match well in shape to the band at 697 nm in the CH2Cl2 solution spectrum of 3 (λ = 697 nm). The powder bands at 350 nm and 438 nm also match well with solution bands at 363 nm and 469 nm. The diffuse reflectance spectrum of 1 (λ = 354, 448 (sh), 507, 741, and 789 nm) matches nicely with the CH2Cl2 solution spectrum (λ = 396, 471 (sh, 28), 520 (sh), 691, and 864 nm). The diffuse reflectance spectrum of Complex 2 possesses bands at 348, 400 (sh), 449 (sh), 509 (sh), and 600 nm whereas the CH2Cl2 solution spectrum of 2 has bands at 358 (sh), 374 (sh), 404 (sh), 469 (sh), 520, 713, and 864 nm. This indicates a rough correspondence between the two spectra. Overall, it is clear that in powder form, all complexes exhibit distinct differences in their diffuse reflectance spectra and that the differences between 4 and 5, unlike the solution spectra, can be clearly observed.

Fig. 10.

Diffuse Reflectance UV-vis spectrum of 1-5 recorded at 25 °C under ambient atmosphere.

To further characterize the solution behavior of complexes 1-5 we performed 31P NMR (162 MHz, 85% H3PO4) on the complexes (Fig. 11) taking advantage of the NMR active-phosphorous nuclei located on the T1Et4iPrIP ligand. The 31P NMR resonance position can provide us with insight regarding the Lewis acidity of the nickel(II) centers which would be modulated by the ancillary ligands which differentiate the complexes. Complexes 4 and 5 appear at identical resonances (41.0 ppm) consistent with the observation that 5 is converted to 4 in solution. The phosphorous in this case is the most deshielded due to the electron withdrawing nature of the chloride ligand. Complex 2 has a resonance that appears at 22.2 ppm. Since the triflate ligands are poor Lewis donors, they do not have a strong influence on the resonance position of the phosphorous. The water ligand in 3, however, is a better donor so more electron density can be delocalized onto the phosphorous thus providing some shielding. In this case, the 31P NMR resonance is observed at 6.2 ppm. Complex 1, contains CH3CN ligands which are better donors compared to water so this complex resonates the furthest upfield (0.2 ppm) in the set.

Fig. 11.

31P NMR (162 MHz) of 1-5 at 25 °C. H3PO4 (85%) and T1Et4iPrIP are included. Solvent: CDCl3.

2.4. Magnetic Studies

The direct current (dc) magnetic susceptibility (χM) of complexes 1–5 between 2-300 K under an applied magnetic field of 1000 G are given in Fig. 12 as χMT versus T plots. The values for χMT at 300 K are 0.94, 1.30, 1.02, 1.13, and 1.26 cm3mol−1K for 1–5, respectively, which are anticipated for ground state S = 1 [28]. Upon lowering the temperature, the χMT value for the complexes remain approximately constant until ~20 K where there is a sharp drop as 2 K is approached. The final values at 2 K are 0.84, 0.35, 0.71, 0.59, and 0.26 cm3mol−1K for 1-5, respectively. Zero-field splitting in the ground state and/or possible weak intermolecular interactions are believe to be responsible for the drop in χMT value as 2 K is approached [30]. In light of this, the magnetic susceptibility data have been examined theoretically using the program Julx [31]. The best fit of the experimental data to the theoretical equation resulted in the following parameters: g = 1.944, D = −0.327 cm−1, E/D = 3.706 for 3; g = 2.280, D = −0.365 cm−1, E/D = 22.178 for 2; g = 2.000, D = −7.402 cm−1, E/D = −0.272 for 3; g = 2.176, D = −0.128 cm−1, E/D = −0.783 for 4; g = 2.258, D = 14.288 cm−1, E/D = 0.095 for 5.

Fig. 12.

Temperature dependence of χMT for complexes 1-5. Solid lines represent the best fits to the Hamiltonian.

2.5. Computational Studies

DFT calculations were performed for compounds 1–5 in the gas phase to fully optimize the ground-state structures. The Energies were calculated by using PBE0/6-31G* methods. A comparison between the theoretical and experimental bond lengths indicates that optimized bond lengths (Table 2) are very close to experimental values. The largest differences between the experimental and calculated metal-ligand bond lengths are 0.08, 0.15, 0.10, 0.01 and 0.14 Å for 1-5, respectively. The calculated and experimental bond angles are also in good agreement. Despite slight deviations, the calculated parameters represent good approximations, and therefore, the electronic properties of the molecules can be inferred.

For both complexes 1 and 2 (Fig. 13(a) and 13(b)), the HOMOs (α193 and α208, respectively) appears to be mainly associated with the ligand imidazole π bonds. The LUMOs (β192 and α207, respectively), on the other hand, contains delocalization between the phosphorous and imidazole carbon p orbitals. Complex 3 (Fig. 13(c)) similarly has a HOMO (αl76) that is composed mainly of imidazole p orbitals, however, the LUMO (β175) is primarily associated with a Ni d orbital along with imidazole and P p orbitals. The HOMO (αl43) for 4 (Fig. 14(a)) depicts electron density distributed in the imidazole π orbitals while the LUMO (β143) possesses Ni d and imidazole p character. For complex 5 (Fig. 14(b)), the HOMO (αl52) consists of Ni and Cl d orbitals interacting in an antibonding fashion. The LUMO (β151) is associated with imidazole and P p orbitals and to a lesser extent a Ni d orbital. The HOMO-LUMO gap energy for 1-5 are 5.47, 5.28, 4.76, 5.12, and 4.29 eV suggesting that 1 is the most stable [32–34],

Fig. 13.

Plots of molecular orbitals: HOMO and LUMO for (a) the cationic of [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(CH3CN)2(OTf)](OTf) (1), [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)2] (2), and (c) the cationic of [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)(H2O)](OTf) (3). Oribital energies (eV) are indicated.

Fig. 14.

Plots of molecular orbitals HOMO and LUMO for (a) the cationic of [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)Cl](OTf) (4) and (b) [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)Cl2] (5). Oribital energies (eV) are indicated.

3. Conclusions

In this study we report the synthesis and characterization of five nickel(II) complexes supported by a tris(imidazolyl)phosphine ligand (tris(1-ethyl-4-iPr-imidazolyl)phosphine. Complex 2 can serve as the precursor to the other complexes reported. For example, adding 2 equiv CH3CN to 2 in CH2Cl2 regenerates 1 while adding 1 equiv water to 2 generates 3. It appears, however, that addition of excess Cl− to 2 only affords 4 in CH2Cl2. Complex 5 can be furnished by reacting T1Et4iPrIP with NiCl2 in CH3CN. The cation of 4 can be spectroscopically generated by dissolving 5 in CH2Cl2. This has been confirmed by UV-vis and 31P NMR spectroscopy. In addition, 4 can be isolated by the addition of Ag(OTf) to 5 in CH2Cl2. Complex 4 is the first example of a 4-coordinate nickel(II) complex derived from a tris(imidazolyl)phosphine ligand. Magnetic studies revealed nickel(II) ground state with S = 1. The data was fitted to a theoretical model which allowed zero-field splitting parameters to be determined. The electronic structure of the complexes were investigated using DFT revealing complex 1 to be the most stable. Overall these studies demonstrate that subtle changes in reaction conditions (solvent, nickel source, trace water) can afford a variety of nickel(II) complexes varying in structure and coordination number.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Materials and methods

The ligand T1Et4iPrIP was synthesized according to a literature method [35]. Anhydrous NiCl2 was prepared by heating NiCl2·6H2O ( Fisher Scientific) under vacuum. Ni(OTf)2 and Me3Si(OTf) was purchased from Alfa Aesar. Ni(OTf)2·2CH3CN was synthesized according to the literature procedure for Fe(OTf)2·2CH3CN [36]. All solvents were dried and distilled by Innovative Technologies Inc. Solvent Purification System. Elemental analysis was performed on pulverized crystalline samples (Atlantic Microlabs, Inc., Norcross GA).

4.2. Synthesis

4.2.1. [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(NCCH3)2(OTf)](OTf)·2CH2Cl2 (1·2CH2Cl2)

To a stirring slurry of Ni(OTf)2·2CH3CN (92 mg, 0.210 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (3 mL) was added dropwise a solution of T1Et4iPrIP (105 mg, 0.238 mmol) also in dichloromethane (2 mL) in a nitrogen filled glovebox. After 2 h stirring the bluish green solution was filtered. On crystallization of the filtrate in a pentane diffusion chamber a light greenish blue crystalline solid was obtained. Yield: 141 mg (76%). 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm) 0.19. FTIR (cm−1, intensive bands only): 3372 (w), 3135 (w), 2970 (m), 2937 (w), 2874 (w), 2316 (m), 2290 (m), 1660 (w), 1552 (m), 1474 (m), 1450 (m), 1420 (w), 1386 (m), 1364 (w), 1335 (m), 1256 (m), 1220 (m), 1153 (m), 1078 (m), 1029 (m), 1022 (m), 964 (w), 938 (w), 886 (w), 810 (w), 756 (s), 731 (s), 701 (w), 680 (w), 638 (s), 573 (m), 541 (m), 516 (m). UV-vis [CH2Cl2; λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1)]: 396 (130), 471 (sh, 28), 520 (sh, 13), 691 (20), 864 (12). Anal. Calcd for 1·CH2Cl2 is C31H47N8F6NiO6S2PCl2: C, 38.53; H, 4.90; N, 11.59. Found: C, 38.11; H, 4.97; N, 11.17.

4.2.2. [Ni(T1Et4PrIP)(OTf)2] (2)

Complex 2 was synthesized from complex 1. Placement of 141 mg of 1 under vacuum at 40 °C for 24 h afforded a light orange-yellow solid. Recrystallization of the solid from dry dichloromethane/diethyl ether at −30 °C yielded light orange-yellow X-ray quality crystals. Yield: 102 mg (95%). 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm) 22.15. FTIR (cm−1, intensive bands only): 3345 (w), 3139 (w), 2970 (m), 1655 (m), 1554 (w), 1475 (m), 1450 (m), 1420 (m), 1385 (m), 1365 (w), 1275 (m), 1242 (m), 1223 (m), 1029 (s), 968 (w), 786 (m), 757 (m), 732 (s), 675 (w), 635 (m), 572 (m), 541 (m), 516 (m). UV-vis [CH2Cl2; λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1)]: 358 (sh, 154), 374 (sh, 140), 404 (sh, 109), 469 (sh, 42), 520 (16), 713 (25), 864 (16). Anal. Calcd for C26H39N6F6NiO6S2P: C, 39.06; H, 4.92; N, 10.51. Found: C, 38.78; H, 5.12; N, 10.41.

4.2.3. [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(H2O)(OTf)](OTf)·CH2Cl2 (3·CH2Cl2)

T1Et4iPrIP (103.1 mg, 0.23 mmol) dissolved in dichloromethane (2 mL) was added to a stirring slurry of Ni(OTf)2·2CH3CN (96.4 mg, 0.22 mmol) in dichloromethane (2 mL) was added dropwise a solution of in a nitrogen filled glovebox. After 1 h of stirring 1 drop (20 mg, 1.1 mmol) of water was added and stirred for an additional 1 h. The light green solution was filtered and pentane diffusion at −30 °C afforded the green crystals. Yield: 81.2 mg (45%). 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm) 6.24. FTIR (cm−1, intensive bands only): 3351 (w), 3141 (w), 2970 (m), 2876 (w), 2316 (m), 1656 (m), 1554 (w), 1472 (m), 1386 (m), 1358 (w), 1278 (m), 1227 (m), 1027 (s), 968 (w), 786 (m), 730 (s), 670 (w), 633 (s), 572 (m), 541 (m), 515 (m). UV-vis [CH2Cl2; λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1)]: 363 (148), 407 (sh, 102), 469 (sh, 42), 697 (36). Anal. Calcd for C26H41N6F6NiO7S2P: C, 38.20; H, 5.06; N, 10.28. Found: C, 38.46; H, 5.08; N, 10.15.

4.2.4. [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(Cl)](OTf) (4)

Complex 4 was synthesized in two different way. In one way Complex 4 was synthesized from complex 2. One equivalent Et4NCl in dichloromethane was added to the orange-yellow solution of complex 2 in dry dichloromethane. The color of the solution was changes from yellow to red. After 1 h of stirring the solution was filtered and crystallization from dry dichloromethane/diethyl ether at −30 °C yielded X-ray quality crystals (yield: 74%). In alternative procedure complex 4 was isolated by the removal of one chloride ion from complex 5 by using one equivalent Ag(OTf) in dichloromethane and crystallization was done from dry dichloromethane/diethyl ether at −30 °C (Yield: 82%). 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCL3): δ (ppm) 41.02. FTIR (cm−1, intensive bands only): 3153 (w), 2967 (m), 2931 (m), 2876 (m), 1556 (m), 1479 (m), 1445 (w), 1413 (m), 1384 (m), 1356 (m), 1331 (m), 1270 (w), 1225 (s), 1195 (s), 1156 (w), 1084 (m), 1028 (s), 967 (w), 932 (w), 888 (w), 786 (m), 755 (m), 734 (m) 672 (s), 635 (m), 611 (m), 571 (s), 540 (s), 516 (s), 478 (m). UV-vis [CH2Cl2; λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1)]: 378 (268), 472 (333), 551 (sh, 75), 806 (91), 916 (123). Anal. Calcd for C25H39N6F3NiO3SPCl: C, 43.78; H, 5.73; N, 12.25. Found: C, 43.93; H, 5.62; N, 12.04.

4.2.5. [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(Cl)2]·1.24CH3CN (5·1.24CH3CN)

To a stirring slurry of NiCl2 (29.1 mg, 0.22 mmol) in dry acetonitrile (2 mL) was added dropwise a solution of T1Et4iPrIP (103.1 mg, 0.23 mmol) also in acetonitrile (2 mL) under dry nitrogen. After stirring for 30 min the orange solution was filtered. On crystallization of the filtrate in an ether diffusion chamber a yellow crystalline solid was obtained. Yield: 80.7 mg (56%). 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 40.98. FTIR (cm−1, intensive bands only): 3122 (w), 3106 (w), 2962 (s), 2931 (m), 2867 (m), 1631 (w, br), 1553 (m), 1473 (m), 1429 (w), 1381 (m), 1358 (m), 1263 (w), 1249 (w), 1201 (m), 1150 (w), 1094 (m), 1010 (m), 964 (w), 886 (w), 814 (w), 788 (w), 733 (m), 672 (m), 618 (m), 545 (m). UV-vis [CH2Cl2; λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1)]: 377 (251), 472 (313), 552 (sh, 84), 806 (91), 914 (122). Anal. Calcd for C24H39N6PNiCl2: C, 50.38; H, 6.87; N, 14.69. Found: C, 50.37; H, 6.84; N, 14.57.

4.3. Physical Measurements

1H NMR (referenced to TMS) and 31P NMR (referenced to 85% H3PO4) spectra were obtained on a Bruker 400 MHz Avance NMR Spectrophotometers. FT-IR spectra were measured on BioRad FTS 175C spectrometer. Optical spectra were collected on a Cary-100 UV-vis spectrophotometer. Diffuse reflectance UV-vis spectra were collected on a Jasco V-570 UV/Vis/NIR spectrometer fitted with an integrating sphere. Variable temperature magnetic susceptibilities were measured using a Quantum Design MPMS SQUID instrument calibrated with a 765-Palladium standard purchased from NIST (formally NSB). Powdered samples of 1-5 were placed in plastic bags. Samples were measured in the temperature range 2-300 K with H = 1000 G. The magnetic contribution of the bags were determined in a 1000 G field between 2-300 K and subtracted from the sample. All samples were placed in plastic drinking straws for measurements. The molar magnetic susceptibilities were corrected for the diamagnetism of the complexes using tabulated values of Pascal’s constants to obtain a corrected molar susceptibility. The program julX written by E. Bill was used for the simulation and analysis of magnetic susceptibility data [31]. The Hamilton operator () was

| (1) |

where g is the average electronic g value, D the axial zero-field splitting parameter, and E/D is the rhombicity parameter. Magnetic moments were obtained from numerically generated derivatives of the eigenvalues of Eq. 1, and summed up over 16 field orientations along a 16-point Lebedev grid to account for the powder distribution of the sample. Intermolecular interactions were considered by using a Weiss temperature, θw, as perturbation of the temperature scale, kT′ = k(T – θw).

4.4. X-Ray Crystallography

Compound 1 and 3 were crystallized by diffusion of pentane into dichloromethane solution of the respective compounds, while compound 2 and 4 were crystallized by diffusion of ether. On the other hand acetonitrile/ether was used for the crystallization for 5. Each crystal was attached to a glass fiber and mounted on a SMART APEX II CCD diffractometer for data collection at 100.0(1) K [37]. The data collection was carried out using MoKα radiation (graphite monochromator). The structure was solved using SIR97 [38] and refined using SHELXL-97 [39]. A direct-methods solution was calculated which provided most non-hydrogen atoms from the E-map. Full-matrix least squares/difference Fourier cycles were performed which located the remaining non-hydrogen atoms. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. All hydrogen atoms were placed in ideal positions and refined as riding atoms with relative isotopic displacement parameters.

4.5. Computational Details

Quantum chemical calculations providing energy minimized molecular geometries, molecular orbitals (HOMO-LUMO), and vibrational spectra for compounds 1-5 were carried out using density functional theory (DFT) as implemented in the GAUSSIAN09 (Rev. D.01) program [40]. We employed the hybrid functional PBE0 [41] containing 25% of exact exchange. We also employed the basis set 6-31G(d) [42]. Full ground state geometry optimization was carried out without any symmetry constraints. Only the default convergence criteria were used during the geometry optimizations. The initial geometry was taken from the crystal structure coordinates in the quartet state. Optimized structures were confirmed to be local minima (no imaginary frequencies for both cases). Experimental and theoretical geometric parameters are summarized in Table 2. Molecular Orbitals were generated using Avogadro [43] (an open-source molecular builder and visualization tool, Versionl.1.0. http://avogadro.openmolecules.net/).

Supplementary Material

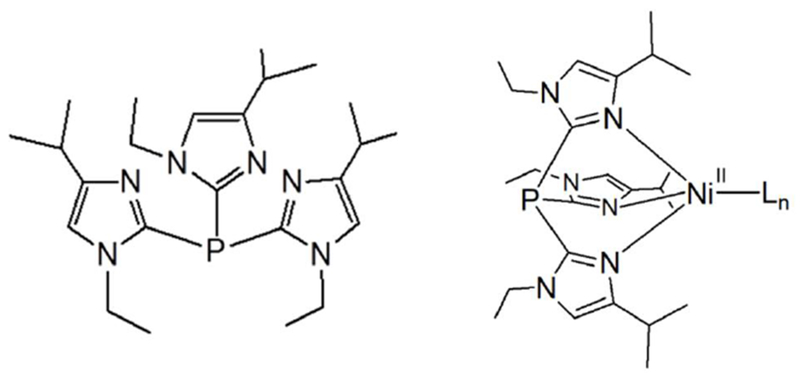

Scheme 1.

Structure of T1Et4PrIP and [NiII(T1Et4PrIP)Ln]x+ (Ln = ancillary ligands).

The structures of [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(CH3CN)2(OTf)](OTf) (1), [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)2(OTf)2] (2), [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(H2O)(OTf)](OTf) (3), [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(Cl)](OTf) (4), and [Ni(T1Et4iPrIP)(Cl)2] (5) (T1Et4iPrIP = tris(1-ethyl-4-iPr-imidazolyl)phosphine) are reported.

Complex 2 can be reversibly converted to all other reported compounds by altering the solvent and/or treating with the appropriate reagent.

Complexes 5 is converted to 4 when dissolved in dichloromethane solvent.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. M. M. Szczęśniak for assistance with the DFT calculations. FAC acknowledges the receipt of an OU-REF grant. NIH Grant No. R15GM112395 and NSF Grants No. CHE-0748607, CHE-0821487, and CHE-1213440 are gratefully acknowledged. WWB acknowledges an NSF MRI grant (CHE-1725028). We acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Cassandra Ward in the diffuse reflectance spectroscopy measurements at the Wayne State University Lumigen Instrument Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

X-ray crystallographic data in CIF format, and X-ray diffraction data. CCDC 1864529-1864533 (1-5) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/?.

References

- [1].Benini S, Cianci M and Ciurli S, Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 12938–12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hausinger RP, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 2, 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lee WZ, Tseng HS and Kuo TS, Dalton Trans. 2007, 2563–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Torok I, Surdy P, Rockenbauer A, Korecz L, Koolhaas GJAA and Gajda T, J. Inorg. Biochem. 1998, 71, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jenkins RM, Singleton ML, Almaraz E, Reibenspies JH and Darensbourg MY, Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 7280–7293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lebrette H, Brochier-Armanet C, Zambelli B, de Reuse H, Borezee-Durant E, Ciurli S and Cavazza C, Structure 2014, 22, 1421–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Seneque O, Campion M, Giorgi M, Le Mest Y and Reinaud O, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 1817–1826. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li J, Banerjee A, Pawlak PL, Brennessel WW and Chavez FA, Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 5414–5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kunz PC, Borgardts M and Mohr F, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2012, 380, 392–398. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bienko A, Suracka K, Mrozinski J, Kruszynski R and Bienko DC, J. Mol. Struct. 2012, 1019, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Boudier A, Breuil PAR, Magna L, Olivier-Bourbigou H and Braunstein P, J. Organomet. Chem. 2012, 718, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hadadzadeh H, Maghami M, Simpson J, Khalaji AD and Abdi K, J. Chem. Crystallogr. 2012, 42, 656–667. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liu P, Liu QX, Zhao N, An CX, and Lian ZX, Z. Kristallogr.-New Cryst. Struct. 2017, 232, 194–195. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Singh UP, Aggarwal V, Kashyap S and Upreti S, Trans. Metal Chem. 2009, 34, 513–520. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Takayama T, Nakazawa J and Hikichi S, Acta Cryst. C 2016, 72, 842–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].An Y, Li XF, Zhang YL, Yin YS, Sun JJ, Tong SF, Yang H and Yang SP, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2013, 38, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bisht KK, Rachuri Y, Parmar B and Suresh E, J. Solid State Chem. 2014, 213, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Burns PJ, Cox JM and Morrow JR, Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 4545–4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chang HN, Liu YG, Hao ZC, Cui GH and Wang SC, Trans. Metal Chem. 2016, 41, 693–699. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Deng JH, Zhong DC, Wang KJ, Luo XZ and Lu WG, J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1035, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Greiner BA, Marshall NM, Sarjeant AAN and McLauchlan CC, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2007, 360, 3132–3140. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Holczbauer T, Domjan A and Fodor C, Acta Cryst. E-Crystallogr. Commun. 2016, 72, 374–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hu JM, Zhao YQ, Yu BY, Van Hecke K and Cui GH, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2016, 642, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kowalkowska D, Dolega A, Nedelko N, Hnatejko Z, Ponikiewski L, Matracka A, Slawska-Waniewska A, Stragowska A, Slowy K, Gazda M and Pladzyk A, Crystengcomm 2017, 19, 3506–3518. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu GX, Zhou H and Wang XF, J. Chem. Crystallogr. 2013, 43, 335–341. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Paul S, Barik AK, Butcher RJ and Kar SK, Polyhedron 2000, 19, 2661–2666. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang XL, Qu Y, Liu GC, Luan J, Lin HY and Kan XM, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2014, 412, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wojciechowska A, Daszkiewicz M, Staszak Z, Trusz-Zdybek A, Bienko A and Ozarowski A, Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 11532–11542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yang H, Gao H, Wang K and Zhang ZH, Trans. Metal Chem. 2006, 31, 958–963. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pawlak PL, Malkhasian AYS, Sjlivic B, Tiza MJ, Kucera BE and Chavez FA, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2008, 11, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar]

- [31].jul X, http://www.mpibac.mpg.de/bac/index_en.php/logins/bill/julX_en.php.

- [32].Nath P, Bharty MK, Kushawaha SK and Maiti B, Polyhedron 2018, 151, 503–509. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bakr EA, Al-Hefnawy GB, Awad MK, Abd-Elatty HH and Youssef MS, Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2018, 32: e4104. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sahki FA, Messaadia L, Merazig H, Chibani A, Bouraiou A and Bouacida S, J. Chem. Sci. 2017, 129, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lynch WE, Kurtz DM Jr., Wang S and Scott RA, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 11030–11038. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hagen KS, Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 5867–5869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].APEX2 version 2010. 7-0; Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems, Madison, WI: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Altomare A, Burla MC, Camalli M, Cascarano G, Giacovazzo C, Guarliardi A, Moliterni AGG, Polidori G and Spagna R, J. Appl. Cryst. 1999, 32, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sheldrick GM, Acta Cryst. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA Jr., Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Keith T, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J and Fox DJ, Gaussian 09, Revision D.01, Gaussian, Inc, Wallingford, CT, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Adamo C and Barone V, J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Petersson GA and Al-Laham MA, J. Chem. Phys. 1991, 94, 6081–6090. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hanwell M, Curtis D, Lonie D, Vandermeersch T, Zurek E and Hutchison G, J. Cheminformatics 2012, 4, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.