Abstract

Atomoxetine improves inhibitory control and visual processing in healthy volunteers and adults with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). However, little is known about the neural correlates of these two functions after chronic treatment with atomoxetine. This study aimed to use the counting Stroop task with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) to investigate the changes related to inhibitory control and visual processing in adults with ADHD. This study is an 8‐week, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, randomized clinical trial of atomoxetine in 24 drug‐naïve adults with ADHD. We investigated the changes of treatment with atomoxetine compared to placebo‐treated counterparts using the counting Stroop fMRI and two CANTAB tests: rapid visual information processing (RVP) for inhibitory control and delayed matching to sample (DMS) for visual processing. Atomoxetine decreased activations in the right inferior frontal gyrus and anterior cingulate cortex, which were correlated with the improvement in inhibitory control assessed by the RVP. Also, atomoxetine increased activation in the left precuneus, which was correlated with the improvement in the mean latency of correct responses assessed by the DMS. Moreover, anterior cingulate activation in the pre‐treatment was able to predict the improvements of clinical symptoms. Treatment with atomoxetine may improve inhibitory control to suppress interference and may enhance the visual processing to process numbers. In addition, the anterior cingulate cortex might play an important role as a biological marker for the treatment effectiveness of atomoxetine. Hum Brain Mapp 38:4850–4864, 2017. © 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: atomoxetine, counting Stroop fMRI, CANTAB, inhibitory control, visual processing

INTRODUCTION

Attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that may persist into adulthood [Kessler et al., 2005b; Lin et al., 2016; Treuer et al., 2013]. Atomoxetine, an inhibitor of the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing ADHD symptoms [Gau et al., 2007a], improving quality of life [Ni et al., 2017], and improving neuropsychological functions in children [Gau and Shang, 2007a, 2010a, 2010b] and adults [Ni et al., 2013, 2016] with ADHD.

Recent evidence supports that atomoxetine improved inhibitory control in healthy adults [Bush et al., 2013; Chamberlain et al., 2009] and ameliorated executive functions among adults with ADHD in an open‐label, head‐to‐head (atomoxetine versus methylphenidate) randomized trial [Ni et al., 2013]. However, no such study has been conducted to investigate the long‐term treatment effect of atomoxetine relative to placebo on neurocognition in adults with ADHD. Since clinical responses to atomoxetine may not maximally differentiate from those to placebo until 6 weeks of treatment [Montoya et al., 2009], we assessed its effect using neuropsychological tests and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) after an 8‐week treatment.

A meta‐analysis of imaging studies [Hart et al., 2013] revealed that altered inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) functions reduce the ability to optimally recruit subsidiary brain regions to perform cognitive tasks in ADHD [Fassbender and Schweitzer, 2006]. Particularly, the right IFG and ACC are thought to be involved in inhibitory control [Cortese et al., 2012; Hampshire et al., 2010]. Using the stop‐signal task, a single dose of atomoxetine improved inhibitory control and increased right IFG activation in healthy adults [Bush et al., 2013]. Using the GO/NOGO task, a single dose of atomoxetine increased the brain activity of the bilateral IFG and presupplementary motor area in healthy adults [Graf et al., 2011]. However, decreased ACC activation by acute use of atomoxetine was only found in boys with ADHD but not in adults with ADHD [Cubillo et al., 2014]. Moreover, parietal activation is involved in attention and visual processing [Fassbender and Schweitzer, 2006; Schneider et al., 2010]. Specifically, the left superior parietal lobule may be associated with number processing in healthy adults [Cavanna and Trimble, 2006; Dehaene et al., 2003]. Several studies showed robust activity in the left superior parietal lobule/precuneus (BA 7) during a counting Stroop task [Bush et al., 1998; Fan et al., 2014; Lévesque et al., 2006].

The Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) has been used to assess executive functions, including inhibitory control [Gau and Huang, 2014] and visual processing [Shang and Gau, 2011] which are suggested to be the endophenotypes for ADHD. Studies have examined drug‐related improvements on several domains of neuropsychological functions in a single study among children [Gau and Shang, 2010a; Shang and Gau, 2012] and adults [Ni et al., 2013, 2016] with ADHD; and have examined executive functions assessed by the CANTAB with microstructural integrity of frontostriatal fiber tracts in children with ADHD [Chiang et al., 2016; Shang et al., 2013]. Previous studies have showed that patients with ADHD demonstrated poorer performance of inhibitory control in the rapid visual information processing (RVP) test [Gau and Huang, 2014; Gau and Shang, 2010a; Ni et al., 2013] and visual processing in the delayed matching to sample (DMS) test [Shang and Gau, 2011, 2012], as compared to neurotypical children. Therefore, we used the RVP and DMS tests from CANTAB to assess the participants’ cognitive mechanisms of inhibitory control and visual processing load outside the scanner because both tests have been reported to be used to measure the endophenotypes for ADHD. Moreover, the counting Stroop task in the scanner can be used to evaluate the neural substrate of cognitive interference between number and meaning [Bush et al., 1998], and the visual properties of the numbers to evaluate visual processing [Fan et al., 2014]. Despite the striking nature of inhibitory control and visual processing impairment in ADHD, knowledge about its corresponding alterations in the brain is still evolving. Hence, combining the CANTAB and the counting Stroop fMRI offers a better understanding of these two processes.

Previous neurocognitive studies on atomoxetine are mainly limited by the acute treatment of a single dose of atomoxetine and the study subjects only including healthy adults [Chamberlain et al., 2009; Graf et al., 2011; Marquand et al., 2011] or treated children/adolescents with ADHD [Treuer et al., 2013]. There is a lack of data about the efficacy of chronic treatment with atomoxetine on brain activity in drug‐naïve adults with ADHD. Hence, we conducted this clinical trial using the counting Stroop fMRI and the CANTAB as outcome measures to examine the efficacy of atomoxetine in improving inhibitory control and visual processing as shown by the changes in brain activation related to inhibitory control and visual processing among drug‐naïve adults with ADHD. Based on previous fMRI studies in ADHD [Cortese et al., 2012], we hypothesize that atomoxetine might decrease activations in the right IFG and ACC, and increase activations in the left parietal regions in adults with ADHD. According to the hypothesis above, the involvements of the right IFG, ACC, and parietal regions may be related to inhibitory control (right IFG and ACC) and visual processing (parietal), which can be measured by the CANTAB.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Twenty‐four drug‐naïve adults (mean age ± standard deviation = 30.7 ± 8.9 years, 10 males) who had current and childhood ADHD diagnosis according to the DSM‐IV diagnostic criteria based on clinical assessment by the corresponding author (SSG), were recruited from the Department of Psychiatry, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, consecutively if they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The participants’ diagnosis of ADHD was confirmed with psychiatric interview by SSG using the Conners’ Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview [Lin et al., 2016; Macey, 2003] and the modified adult version of the ADHD supplement of the Chinese version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia–Epidemiological Version (K‐SADS‐E) [Chang et al., 2013; Ni et al., 2013] for childhood and current diagnosis of ADHD.

All participants were native Mandarin‐Chinese speakers, had standard scores of the IQ greater than 80 as assessed by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third version [Wechsler, 1997], with normal hearing and normal or corrected‐to‐normal vision. Participants, who had any systemic medical illness, a history of other psychiatric disorders or had been treated with any psychotropic agent, including medications for ADHD were excluded from this study.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan (IRB ID: 200903059M; http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00917371) before study implementation. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants who had received the detailed information of experimental purpose and administration.

This study was an 8‐week open‐label, head‐to‐head randomized clinical trial. Participants were randomly assigned to either the atomoxetine or the placebo group at a 1:1 ratio, which was determined by a computer‐generated random sequence. All the 24 drug‐naïve adults with ADHD were randomized to two treatment groups: 12 with atomoxetine hydrochloride once daily and 12 with placebo once daily. They received the pre‐treatment and post‐treatment scans with an 8‐week interval. Twelve age‐, gender‐, and IQ‐matched healthy controls were recruited from the similar local community for comparison. After the first scan, ADHD participants started to take a placebo or atomoxetine (an initial dosage of 0.5 mg/kg for 7 days (1st week), followed by 1.2 mg/kg for another seven weeks). Drug dosage would be titrated in the post‐treatment depending on clinical response and adverse effects (maximum daily dosage of atomoxetine = 1.2 mg/kg). The side effects of medications were investigated at Weeks 4 to 5 and Weeks 8 to 10.

Clinical Global Impression‐ADHD Severity Scale

The Clinical Global Impression‐ADHD Severity Scale (CGI‐ADHD‐S) is a single item assessment of the global severity of ADHD symptoms in relation to the clinician's total experience with other ADHD patients. The severity is rated on a 7‐point scale (from 1 = normal, not at all ill, to 7 = among the most extremely ill). The CGI‐ADHD‐S was used for the assessments of the pre‐treatment and post‐treatment with an 8‐week interval. This scale has been widely used in the treatment studies on ADHD in Taiwan [Gau et al., 2007a, 2008; Gau and Shang, 2010a, 2010b; Shang et al., 2015, 2016].

Adult Self‐Report Scales

According to the DSM‐IV ADHD symptom criteria, the adult self‐report scales (ASRS) consists two subscales to evaluate the symptoms of Inattention (ASRS‐I, 9 items) and Hyperactivity‐Impulsivity (ASRS‐HI, 9 items) [Kessler et al., 2005a]. Each item asks how often a symptom occurred during the last 6 months on a 5‐point scale (from 0 = never, to 4 = very often). The psychometric property of the Chinese version of the ASRS had been established using an epidemiological sample of the adult population [Yeh et al., 2008]. The Chinese version of the ASRS was used for to assess ADHD symptoms at the pre‐treatment and post‐treatment with an 8‐week interval. This scale has been used widely in adult ADHD studies in Taiwan [Chao et al., 2008; Gau et al., 2007b; Lin et al., 2016; Ni et al., 2013, 2017; Yang et al., 2013].

Neuropsychological Measures

RVP and DMS were chosen from the CANTAB to assess inhibitory control [Gau and Huang, 2014; Sahakian et al., 1989] and visual processing [Shang and Gau, 2011, 2012], respectively.

The RVP test is designed to examine sustained attention capacity and inhibitory control [Sahakian et al., 1989]. In the RVP test, participants were asked to respond to the specific sequence of digits, when a white box was presented in the center of the screen with digits (ranging from 2 to 9) appearing one at a time (100 digits/minute) in a pseudo‐random order. Participants were instructed to respond to three specific number sequences of digits (i.e., 2‐4‐6, 3‐5‐7, 4‐6‐8) by pressing the touch pad. Four measures were recorded: (1) A’: a signal detection measure of sensitivity to the target, regardless of response tendency [Sahgal, 1987]; (2) mean latency: mean time taken to respond correctly; (3) probability of false alarms (if the participant responding inappropriately): total false alarms divided by the sum of total false alarms and total correct rejections; and (4) probability of hits (hit, the participant responding correctly): total hits divided by the sum of total hits and total misses.

The DMS assessed the participants’ visual processing and short‐term visual memory to remember the visual features of a complex target stimulus in a four‐choice delayed recognition memory paradigm [Égerházi et al., 2007]. At the beginning of each trial, a sample visual pattern, which was complex and abstract, appeared in the center of the screen for 4.5 sec. Then, the sample visual pattern disappeared. At the simultaneous matching condition, the participant was presented four‐choice patterns and had to select the pattern which exactly matched the sample. Participant had to make a choice until a correct choice was made. At the delayed matching condition, the duration between the sample and the choice patterns was randomized with a delay (0, 4, or 12 sec). This procedure ensured that the participant could not predict which task condition would follow. The mean latency was recorded as the average speed to make correct responses and the number of correct responses in the simultaneous and three delay trials.

Functional Activation Task

In the counting Stroop task [Fan et al., 2014], experimental stimuli were divided into congruent, incongruent, and control conditions, with 24 trials in each condition. In the “congruent” condition, the number of words was consistent with the meaning of the word such as “one,” two," “three,” or “four.” In the “incongruent” condition, the number of words was inconsistent with the meaning of the word. In the “control” condition, the Chinese words did not give any clue to number. All the words of the three conditions were matched for the number of syllables, visual complexity, and frequency. Participants were instructed to report the number of words in each set via button‐press with one, two, three, and four buttons from left to right on the keypad.

MRI Image Acquisition

Participants lay in the scanner with their head position secured. The head coil was positioned over the participants' head. Participants viewed visual stimuli projected onto a screen via a mirror attached to the inside of the head coil. Images were acquired using a 3 Tesla Siemens Tim‐Trio scanner. The functional and structural imaging parameters were the same as our prior study [Fan et al., 2014]. The task was administered in a pseudorandom order for all participants for event‐related designs [Burock et al., 1998].

Clinical and Neuropsychological Analysis

We used SPSS to conduct statistical analysis. The descriptive results were displayed as frequency and percentage for the categorical variables, and mean and SD for the continuous variables. We conducted a 2 visit (pre‐, post‐treatment) by 2 treatments (atomoxetine, placebo) ANOVA for neuropsychological measures and clinical symptoms. Moreover, two‐sample t‐tests were used to examine the differences in neuropsychological scores between groups (pre‐treatment atomoxetine vs. healthy control, post‐treatment atomoxetine vs. healthy control, pre‐treatment placebo vs. healthy control, and post‐treatment placebo vs. healthy control).

Image Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPM8 (Statistical Parametric Mapping). The preprocessing procedures were the same as our prior study [Fan et al., 2014]. The functional images were corrected for the differences in slice‐acquisition time to the middle volume and were realigned to the first volume in the scanning session using affine transformations. No participant had more than 3 mm of movement in any plane. Co‐registered images were normalized to the MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) average template. Statistical analyses were calculated on the smoothed data (10 mm isotropic Gaussian kernel), with a high pass filter (128 sec cutoff period) to remove low‐frequency artifacts. Data from each participant were entered into a general linear model using an event‐related analysis procedure [Josephs and Henson, 1999]. Stimuli were treated as individual events for analysis and modeled using a canonical HRF (Hemodynamic Response Function). Parameter estimates from contrasts of the canonical HRF in single subject models were entered into random‐effects analysis across all participants in a whole brain analysis. There were types of three events: congruent, incongruent, and control. To observe the neural correlates of inhibitory control, we compared the incongruent to the congruent condition. To further observe the neural correlates of visual processing, we compared the larger number of words (i.e., “three” and “four”) to the fewer number of words (i.e., “one” and “two”) in the incongruent condition and the congruent condition.

Repeated measures ANOVA, with 2 visits (pre‐, post‐treatment) as the within‐subject factor and 2 treatments (atomoxetine, placebo) as the between‐subject factor, were conducted to reveal the significant difference of neural changes induced by the two medications. Also, a post hoc paired t‐test was used to examine the difference of post‐ vs. pre‐treatment within each group to reveal the within‐subject changes. Moreover, two‐sample t‐tests between groups (pre‐treatment atomoxetine vs. healthy control, post‐treatment atomoxetine vs. healthy control, pre‐treatment placebo vs. healthy control, and post‐treatment placebo vs. healthy control) were conducted to test for potential atomoxetine normalization effects. Reported areas of significant activations are P < 0.0005 uncorrected in a whole brain analysis. Furthermore, three anatomical masks (the WFU PickAtlas) of the right IFG, ACC, and left precuneus based on our a priori hypothesis were used to control for multiple comparisons at P < 0.05 FWE (familywise error) corrected at the voxel level. The WFU PickAtlas was integrated into the SPM software environment using the standard toolbox method, and this atlas provided a sort of ROI masks in MNI space. In addition, when a mask was applied, the SPM small volume correction was automatically implemented on the basis of the mask limiting the number of multiple statistical comparisons for more robust inference. Therefore, we used the WFU PickAtlas to define ROI masks with selecting the anatomical masks of the right IFG, ACC, and left precuneus, respectively [Chou et al., 2015; Fan et al, 2014].

Correlation Analyses for Neuropsychological Measures and Behavioral Performance

Two kinds of correlation analyses were performed: (1) the correlation between brain activation and neuropsychological measures, and (2) the correlation between brain activation and behavioral performance. For neuropsychological measures, either the RVP or DMS tasks had more than one testing scores. We utilized a multiple regression analysis provided in SPM to examine the correlations between the changes in neuropsychological performance (post‐ vs. pre‐treatment) and the changes of brain activation (post‐ vs. pre‐treatment), including ADHD symptoms (CGI‐ADHD‐S, ASRS‐I, and ASRS‐HI) as covariates, in a whole brain analysis. Specifically, we entered the continuous variables of the performance of the RVP task (four testing scores) with signal intensity changes for the incongruent versus congruent contrast, and the DMS task (two testing scores) with signal intensity changes for the larger number of words versus the fewer number of words contrast, respectively. This allowed us to examine atomoxetine‐related increases or decreases in activation that were independent of ADHD symptoms. Reported areas of significant activations are P < 0.005 uncorrected in a whole brain analysis. To visualize correlations, we extracted the beta values from the peak voxels of brain regions for these correlation analyses. For behavioral performance, correlation analysis was used to correlate the changes of reaction time obtained from the Stroop task (post‐ vs. pre‐treatment) and the changes of brain activation (post‐ vs. pre‐treatment), including ADHD symptoms as covariates, in a whole brain analysis.

Regression Analysis for Prediction

Linear regression analysis was used to examine how pre‐treatment signal intensity was predictive of a clinical improvement (CGI‐ADHD‐S, ASRS‐I, and ASRS‐HI of post‐ vs. pre‐treatment) in an ROI analysis. According to previous studies [Fan et al., 2014], inhibitory control and visual processing were related to activations in the right IFG, ACC, and parietal regions. Thus, these three regions were chosen to be predictive of clinical improvements. Therefore, beta values from the peak voxels of the right IFG, ACC, and left precuneus at the pre‐treatment were used as predictors, along with a clinical improvement (CGI‐ADHD‐S, ASRS‐I, and ASRS‐HI of post‐ vs. pre‐treatment) as the dependent variable, to determine whether regional activity was predictive of a clinical improvement.

RESULTS

Clinical and Neuropsychological Results

There were no significant differences in handedness, gender, age, and IQ profiles between the atomoxetine and placebo groups (Table 1). Table 2 summarizes the clinical performance of the CGI‐ADHD‐S and ASRS measures. A 2 visit (pre‐, post‐treatment) by 2 treatment (atomoxetine, placebo) ANOVA on the CGI‐ADHD‐S revealed a marginal interaction between visit and treatment (F(1,22) = 3.12, P = 0.09), and the post hoc t‐tests revealed that the atomoxetine group had a significant improvement in overall symptom severity in the post‐treatment than in the pre‐treatment (t(22) = −2.23, P < 0.05). Analysis on ASRS‐HI revealed a marginal interaction between visit and treatment (F(1,22) = 4.17, P = 0.054), and the post hoc t‐tests showed that the atomoxetine group had significant improvement in Hyperactivity‐Impulsivity symptoms in the post‐treatment than in the pre‐treatment (t(11) = 4.35, P < 0.05). The other effects were not significant (Ps > 0.05).

Table 1.

Gender, handedness, age, and intelligence quotient scores for the atomoxetine, placebo, and healthy control groups

| Attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder | Healthy control (n = 12) | P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomoxetine (n = 12) | Placebo (n = 12) | |||

| Handedness (left/right) | 1/11 | 1/11 | 1/11 | |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 5/7 | 5/7 | 5/7 | |

| Age (Mean ± S.D.) | 28.9 ± 7.8 | 32.5 ± 9.8 | 30.3 ± 7.7 | 0.377 |

| Age of onset (Mean ± S.D.) | 6.4 ± 1.5 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | N.A. | 0.837 |

| Intelligence quotient (IQ) | ||||

| Verbal IQ | 117.2 ± 12.9 | 116.7 ± 11.9 | 115.2 ±7.7 | 0.919 |

| Performance IQ | 111.3 ± 12.0 | 121.7 ± 16.2 | 119.3 ± 10.1 | 0.090 |

| Full‐scale IQ | 115.8 ± 13.5 | 119.9 ± 13.8 | 118.3 ± 8.6 | 0.454 |

| Height (cm) (Mean ± S.D.) | 165.19 ± 6.96 | 165.96 ± 9.75 | 165.08 ± 7.23 | 0.822 |

| Weight (kg) (Mean ± S.D.) | 69.85 ± 19.15 | 64.31 ± 12.77 | 64.50 ± 12.12 | 0.408 |

| ADHD symptomsa | ||||

| Inattention | 8.6 ± 0.7 | 8.8 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.482 |

| Hyperactivity | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 3.3 ± 2.0 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.561 |

| Impulsivity | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 1.000 |

| Total scores | 14.2 ± 2.9 | 14.5 ± 2.8 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0.777 |

Note: aAssessed by the Adult Self Report Scale; SD, standard deviation; IQ, intelligence quotient; *All P values > 0.05 for the comparisons between the atomoxetine and placebo groups.

Table 2.

The clinical performance in the atomoxetine and placebo groups

| Atomoxetine | Placebo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐medication | Post‐medication | Pre‐medication | Post‐medication | |

| Clinical Global Impression (CGI) | ||||

| CGI‐ADHD‐S | 5.83 ± 0.83 | 2.67 ± 0.98 | 6.08± 0.51 | 4.08 ± 1.93 |

| Adult Self‐Report Scales (ASRS) | ||||

| Inattentive total score | 26.83 ± 6.16 | 14.00 ± 5.83 | 27.67± 5.69 | 20.82 ± 9.81 |

| Hyperactive‐impulsive score | 20.17 ± 6.82 | 8.42 ± 6.16 | 20.67± 6.72 | 17.18 ± 11.23 |

Note: CGI‐ADHD‐S, the severity of illness.

Table 3 summarizes the performance of the RVP and DMS tasks of the CANTAB. For inhibitory control, a 2 visit (pre‐, post‐treatment) by 2 treatment (atomoxetine, placebo) ANOVA on the A' (target sensitivity) in RVP revealed an interaction between visit and treatment (F(1,22) = 4.79, P < 0.05), and the post hoc t‐tests revealed that the atomoxetine group was more accurate in the post‐treatment than the pre‐treatment (t(11) = −4.88, P < 0.05). The same 2 by 2 ANOVA on the probability of hits in RVP showed an interaction between visit and treatment (F(1,22) = 4.56, P < 0.05), and the post hoc t‐tests revealed that the atomoxetine group was more accurate in the post‐treatment than the pre‐treatment (t(11) = −4.66, P < 0.05). As compared to the healthy control group, two‐sample t‐tests on the pre‐treatment revealed poor performance in the A' (target sensitivity) and the probability of hits in RVP for either the atomoxetine group (t(22) = −2.36, P < 0.05; t(22) = −2.37, P < 0.05, respectively) or the placebo group (t(22) = −2.33, P < 0.05; t(22) = −2.40, P < 0.05, respectively). As to the post‐treatment, two‐sample t‐tests revealed no significant difference in the A' (target sensitivity) and the probability of hits in RVP between the atomoxetine group and the healthy control group (t(22) = 0.49, P = 0.63; t(22) = 0.48, P = 0.63, respectively), but significantly poorer performance on the A' (target sensitivity) and the probability of hits in RVP for the placebo group (t(22) = −2.10, P < 0.05; t(22) = −2.13, P < 0.05, respectively) relative to the healthy control group.

Table 3.

The performance in the rapid visual information processing (RVP) and delayed matching to sample (DMS) for the atomoxetine and placebo groups

| Atomoxetine | Placebo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐medication | Post‐medication | Pre‐medication | Post‐medication | |

| Rapid Visual Information Processing | ||||

| A' | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 0.93± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.04 |

| Mean Latency | 441 ± 100 | 399 ± 60 | 427 ± 32 | 395 ± 46 |

| Probability of false alarm | 0.003 ± 0.004 | 0.002 ± 0.003 | 0.001 ± 0.002 | 0.002 ± 0.002 |

| Probability of hit | 0.698 ± 0.010 | 0.833 ± 0.118 | 0.704 ± 0.152 | 0.738 ± 0.170 |

| Delayed Matching to Sample | ||||

| Mean correct latency | 2636.3 ± 320.8 | 2120.4 ± 342.0 | 2453.3 ± 649.2 | 2430.1 ± 991.3 |

| Number of correct (%) | 96.7 ± 4.3 | 98.9 ± 2.8 | 99.2 ± 2.9 | 97.3 ± 4.5 |

Note: ADHD, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder; SD, standard deviation; A', signal detection measure of sensitivity to the target.

Regarding visual processing, the DMS task, the same 2 by 2 ANOVA on the mean correct latency of simultaneous trials showed an interaction between visit and treatment (F(1,22) = 6.01, P < 0.05), and the post hoc t‐tests showed that the atomoxetine group was faster in the post‐treatment than in the pre‐treatment (t(11) = 3.34, P < 0.05). Relative to the healthy control group, two‐sample t‐tests on the pre‐treatment revealed poorer performance in the mean correct latency of simultaneous trials in DMS for either the atomoxetine (t(22) = 4.26, P < 0.05) or the placebo group (t(22) = 2.28, P < 0.05). As to the post‐treatment, two‐sample t‐tests revealed no significant difference in the mean correct latency of simultaneous trials between the atomoxetine group and the healthy control group (t(22) = −1.03, P = 0.31), but significantly poorer performance for the placebo group (t(22) = 2.10, P < 0.05) relative to the healthy control group.

Behavioral Performance of the Counting Stroop

Table 4 presents the reaction time and accuracy of the counting Stroop test for the three groups. A 2 visit (pre‐, post‐treatment) by 2 treatment (atomoxetine, placebo) ANOVA on the reaction time of the incongruent versus congruent condition revealed an interaction between visit and treatment (F(1,22) = 4.68, P < 0.05), and the post hoc t‐tests showed that the atomoxetine group was faster in the post‐treatment than in the pre‐treatment (t(11) = 4.73, P < 0.05). Regarding accuracy, there were no significant differences in either the pre‐ versus post‐treatment or between the two treatment groups (Ps > 0.05).

Table 4.

Comparison of reaction time and accuracy of the counting Stroop test in three conditions for the atomoxetine, placebo, and healthy control groups

| Attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomoxetine | Placebo | ||||

| Pre‐medication | Post‐medication | Pre‐medication | Post‐medication | Healthy control | |

| Reaction time (ms) | |||||

| Congruent | 743 ± 117 | 763 ± 193 | 775 ± 146 | 819 ± 182 | 734 ± 143 |

| Incongruent | 819 ± 130 | 822 ± 191 | 859 ± 127 | 885 ± 194 | 769 ± 131 |

| Control | 731 ± 92 | 792 ± 208 | 784 ± 121 | 813 ± 162 | 725 ± 123 |

| Accuracy (%) | |||||

| Congruent | 100 ± 0% | 100 ± 0% | 99 ± 2% | 100 ± 1% | 98 ± 4% |

| Incongruent | 99 ± 2% | 98 ± 3% | 98 ± 3% | 97 ± 3% | 95 ± 7% |

| Control | 99 ± 2% | 99 ± 3% | 99 ± 2% | 99 ± 5% | 97 ± 5% |

Regarding reaction time of the incongruent versus congruent condition on the pre‐treatment, two‐sample t‐tests revealed poorer performance for either the atomoxetine (t(22) = 2.41, P < 0.05) or the placebo group (t(22) = 2.38, P < 0.05) relative to the healthy control group. As to reaction time on the post‐treatment, two‐sample t‐tests revealed no significant difference between the atomoxetine group and the healthy control group (t(22) = 1.12, P = 0.28), but significantly poorer performance for the placebo group (t(22) = 2.15, P < 0.05) relative to the healthy control group. Regarding the accuracy of the incongruent versus congruent condition, there were no significant differences between the atomoxetine and the healthy control group in both the pre‐ and post‐treatments (Ps > 0.05).

fMRI Results

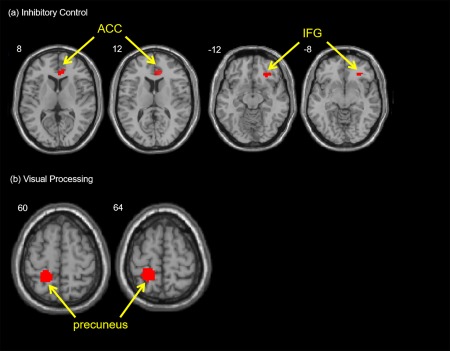

For inhibitory control, the 2 visit by 2 treatment ANOVA revealed an interaction with greater activation in the right IFG (BA 47) and right ACC (BA 32) for the incongruent versus congruent condition (Table 5 and Fig. 1a). A post‐hoc paired t‐test on the post‐ versus pre‐treatment revealed less activation in the right IFG in the atomoxetine group and was not significant in the placebo group (Table 6).

Table 5.

Brain regions for the treatment by visit interactions, main effect of treatment, and main effect of visit on activation

| Cortical regions | H | BA | Voxels | Z test | MNI coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Inhibitory Control: the Incongruent versus the Congruent conditions | |||||||

| Treatment by Visit Interactions | |||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrusa | R | 47 | 22 | 2.01 | 30 | 35 | −11 |

| Anterior cingulate cortexa | R | 32 | 96 | 2.33 | 9 | 35 | 7 |

| Main Effects of Treatment | |||||||

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | 21 | 27 | 3.07 | −39 | 8 | −20 |

| R | 21 | 11 | 2.86 | 66 | −16 | −17 | |

| Cingulate gyrus | L | 24 | 86 | 2.95 | −3 | −7 | 37 |

| Main Effects of Visit | |||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | 44/45 | 132 | 3.27 | −60 | 8 | 10 |

| L | 47 | 55 | 2.87 | −51 | 29 | −2 | |

| Superior frontal gyrus | R | 9 | 26 | 2.99 | 15 | 62 | 34 |

| Superior temporal gyrus | L | 22 | 17 | 2.72 | −51 | −40 | 10 |

| R | 22 | 25 | 2.55 | 66 | −19 | 1 | |

| Visual Processing: the Larger Number of Words versus the Fewer Number of Words | |||||||

| Treatment by Visit Interactions | |||||||

| Precuneusa | L | 7 | 14 | 2.32 | −15 | −50 | 64 |

| Main Effects of Treatment | |||||||

| Medial frontal gyrus | L | 6 | 51 | 3.71 | −3 | −19 | 58 |

| Main Effects of Visit | |||||||

| Middle frontal gyrus | L | 6 | 51 | 4.24 | −48 | −7 | 55 |

| L | 10 | 14 | 3.69 | −39 | 50 | 19 | |

| Medial frontal gyrus | L | 6 | 55 | 3.81 | 0 | 5 | 52 |

Note: H, hemisphere; L, left; R, right; BA, Brodmann's area; Voxels, number of voxels in cluster at P < 0.0005 uncorrected; Coordinates of activation peak(s) within a region based on a z test are given in the MNI stereotactic space (x, y, z).

P < 0.05 for FWE (familywise error) corrected with the use of an anatomical mask.

Figure 1.

(a) Inhibitory Control: The interaction of treatment by visit elicited greater activation in the right IFG (BA 47) and right ACC (BA32) from pre‐treatment to post‐treatment with atomoxetine in adults with ADHD for the incongruent condition versus the congruent condition.(b) Visual Processing: The interaction of treatment by visit elicited greater activation in the left precuneus from post‐treatment to pre‐treatment with atomoxetine in adults with ADHD for the larger versus the fewer number of words. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 6.

Inhibitory control: greater activation for the incongruent compared to the congruent conditions for each visit (pre‐, post‐treatment), and the comparison between pre‐ and post‐treatments within each group (atomoxetine, placebo)

| Cortical regions | H | BA | Voxels | Z test | MNI coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| ADHD treated with atomoxetine | |||||||

| Pre‐treatment | |||||||

| Supramarginal gyrus | L | 40 | 24 | 4.02 | −45 | −42 | 33 |

| R | 40 | 3 | 3.35 | 42 | −45 | 36 | |

| Middle frontal gyrus | L | 9/10 | 55 | 3.96 | −45 | 42 | 15 |

| R | 9/10 | 14 | 3.62 | 57 | 21 | 30 | |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | 47 | 26 | 3.53 | −36 | 24 | −6 |

| R | 45/47 | 55 | 2.91 | 42 | 33 | 3 | |

| Post‐treatment | |||||||

| Cingulate gyrus | L | 32 | 3 | 3.59 | −9 | −21 | 33 |

| R | 32 | 5 | 3.53 | 9 | 18 | 36 | |

| Pre > post‐treatment | |||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus a | R | 47 | 50 | 2.86 | 36 | 18 | −6 |

| Post‐ > pre‐treatment | |||||||

| None | |||||||

| ADHD treated with placebo | |||||||

| Pre‐treatment | |||||||

| Precuneus | L | 19 | 3 | 3.35 | −33 | −66 | 39 |

| Post‐treatment | |||||||

| Medial frontal gyrus | L | 11 | 4 | 3.69 | −6 | 48 | −18 |

| Pre‐ > post‐treatment | |||||||

| None | |||||||

| Post‐ > pre‐treatment | |||||||

| None | |||||||

| Healthy control group | |||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | 45 | 7 | 4.04 | −48 | 36 | 15 |

| Postcentral gyrus | L | 6 | 60 | 3.99 | −60 | −21 | 30 |

| R | 6 | 18 | 3.60 | 63 | −21 | 27 | |

| Supramarginal gyrus | L | 40 | 17 | 3.86 | −48 | −36 | 33 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | L | 10 | 23 | 3.73 | −15 | 66 | 15 |

Note: H, hemisphere; L, left; R, right; BA, Brodmann's area; Voxels, number of voxels in cluster at P < 0.0005 uncorrected; Coordinates of activation peak(s) within a region based on a z test are given in the MNI stereotactic space (x, y, z).

P < 0.05 for FWE (familywise error) corrected with the use of an anatomical mask.

For visual processing, the 2 visit by 2 treatment ANOVA revealed an interaction with greater activation in the left precuneus (BA 7) for the larger number of words versus the fewer number of words (Table 5 and Fig. 1b). A post‐hoc paired t‐test on the post‐ versus pre‐treatment revealed greater activation in the left precuneus in the atomoxetine group and no significant change in the placebo group (Table 7).

Table 7.

Visual processing: greater activation for the larger number of words compared to the fewer number of words for each visit (pre‐, post‐treatment), and the comparison between pre‐ and post‐treatments within each group (atomoxetine, placebo)

| Cortical regions | H | BA | Voxels | Z test | MNI coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| ADHD treated with atomoxetine | |||||||

| Pre‐treatment | |||||||

| Lingual gyrus | R | 18 | 13 | 3.49 | 18 | −78 | −12 |

| L | 18 | 7 | 3.61 | −12 | −81 | −12 | |

| Precentral gyrus | L | 4 | 59 | 3.99 | −36 | −27 | 51 |

| Post‐treatment | |||||||

| Lingual gyrus | R | 18 | 163 | 5.29 | 12 | −90 | −3 |

| L | 18 | 207 | 4.62 | −15 | −81 | −15 | |

| Precentral gyrus | L | 4 | 815 | 4.41 | −36 | −21 | 54 |

| Insula | L | 13 | 70 | 4.19 | −33 | −12 | 15 |

| Precuneus | L | 7 | 57 | 3.50 | −21 | −66 | 63 |

| Pre‐ > post‐treatment | |||||||

| None | |||||||

| Post‐ > pre‐treatment | |||||||

| Precuneus a | L | 7 | 32 | 2.25 | −15 | −54 | 45 |

| ADHD treated with placebo | |||||||

| Pre‐treatment | |||||||

| Lingual gyrus | R | 18 | 165 | 4.70 | 15 | −81 | −9 |

| L | 18 | 16 | 3.73 | −12 | −81 | −9 | |

| Postcentral gyrus | L | 3 | 645 | 4.28 | −51 | −21 | 51 |

| Post‐treatment | |||||||

| Precentral gyrus | L | 4 | 1455 | 5.40 | −27 | −30 | 69 |

| Lingual gyrus | R | 18 | 585 | 5.00 | 15 | −81 | −6 |

| L | 18 | 84 | 4.17 | −12 | −90 | −9 | |

| Pre > post‐treatment | |||||||

| None | |||||||

| Post > pre‐treatment | |||||||

| None | |||||||

| Healthy control group | |||||||

| Lingual gyrus | R | 18 | 304 | 5.03 | 15 | −81 | −9 |

| Precentral gyrus | L | 4 | 600 | 5.01 | −33 | −21 | 60 |

| Precuneus | L | 7 | 9 | 3.71 | −21 | −63 | 51 |

Note: H, hemisphere; L, left; R, right; BA, Brodmann's area; Voxels, number of voxels in cluster at P < 0.0005 uncorrected; Coordinates of activation peak(s) within a region based on a z test are given in the MNI stereotactic space (x, y, z).

P < 0.05 for FWE (familywise error) corrected with the use of an anatomical mask.

To explore potential atomoxetine normalization effects, Supporting Information Tables I and II present the neural correlates of inhibitory control and visual processing between the atomoxetine, the placebo, and healthy control groups. For inhibitory control with the pre‐treatment, a two‐sample t‐test revealed greater activation in the right IFG and ACC for either the atomoxetine group or the placebo group relative to the healthy control group. As to inhibitory control with the post‐treatment, a two‐sample t‐test revealed no significant difference in brain activation between the atomoxetine group and the healthy control group, but significantly greater activation in the right IFG and ACC for the placebo group relative to the healthy control group (Supporting Information Table I). For visual processing with the pre‐treatment, a two‐sample t‐test revealed less activation in the left precuneus for either the atomoxetine group or the placebo group relative to the healthy control group. As to visual processing with the post‐treatment, a two‐sample t‐test revealed no significant difference in the left precuneus activation between the atomoxetine group and the healthy control group, but significantly less activation in the left precuneus for the placebo group relative to the healthy control group (Supporting Information Table II).

Correlation Results for Neuropsychological Measures and Behavioral Performance

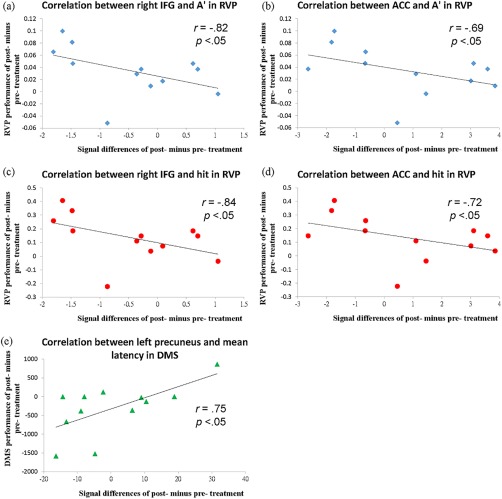

We conducted the correlations between the changes in neuropsychological performance and the changes in brain activation, partialing out ADHD symptoms of CGI‐ADHD‐S, ASRS‐I, and ASRS‐HI as covariates (Table 8). For inhibitory control, improved performance in the RVP was negatively correlated with increasing activation for the incongruent minus congruent condition in the right IFG (BA 47) and right ACC (BA 32) in the atomoxetine group (Table 8). For descriptive purposes, we visualized the results by correlating the performance of the RVP task with beta values of the peak voxels from the post‐treatment to the pre‐treatment for the A' in the IFG and ACC (r = −0.82 and r = −0.69, respectively), as well as for the probability of hit in the IFG and ACC (r = −0.84 and r = −0.72, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Table 8.

Increasing brain activation with the neuropsychological performance (RVP and DMS) between pre‐treatment and post‐treatment, partialing out ADHD symptoms (CGI‐ADHD‐S and ASRS scores)

| Cortical regions | H | BA | Voxels | Z test | MNI coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Inhibitory Control: the Incongruent versus the Congruent conditions | |||||||

| Increase with A' (sensitivity to the target) in RVP | |||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 47 | 75 | 3.42 | 30 | 38 | −11 |

| R | 47 | 19 | 2.20 | 42 | 26 | −8 | |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | R | 32 | 10 | 2.30 | 3 | 32 | 28 |

| Increase with the probability of hit in RVP | |||||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 47 | 55 | 3.07 | 39 | 35 | −8 |

| R | 47 | 18 | 2.34 | 42 | 23 | −8 | |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | R | 32 | 10 | 2.30 | 3 | 32 | 28 |

| Visual Processing: the Larger Number of Words versus the Fewer Number of Words | |||||||

| Increase with the mean correct latency in DMS | |||||||

| Precuneus/Superior parietal lobule | L | 7 | 12 | 2.70 | −12 | −67 | 64 |

Note: H, hemisphere; L, left; R, right; BA, Brodmann's area; Voxels, number of voxels in cluster at P < 0.005 uncorrected; Coordinates of activation peak(s) within a region based on a z test are given in the MNI stereotactic space (x, y, z).

Figure 2.

The correlations between neuropsychological measures and brain activation, partialing out ADHD symptoms (CGI‐ADHD‐S and ASRS scores), in the atomoxetine group. (a) A negative correlation between decreasing activation in the right IFG (from post‐treatment to pre‐treatment) and A' of the RVP [r = −0.82, P < 0.05]. (b) A negative correlation between decreasing activation in the ACC (from post‐treatment to pre‐treatment) and A' of the RVP [r = −0.69, P < 0.05]. (c) A negative correlation between decreasing activation in the right IFG (from post‐treatment to pre‐treatment) and probability of hit of the RVP [r = −0.84, P < 0.05]. (d) A negative correlation between decreasing activation in the ACC (from post‐treatment to pre‐treatment) and probability of hit of the RVP [r = −0.72, P < 0.05]. (e) A positive correlation between increasing activation in the left precuneus (from post‐treatment to pre‐treatment) and mean correct latency of the DMS [r = 0.75, P < 0.05]. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

For visual processing, increasing activation in the left precuneus from post‐treatment to pre‐treatment was positively correlated with the mean correct latency of the DMS for the larger minus fewer number of words in the atomoxetine group (Table 8). For descriptive purposes, we visualized the results by correlating the performance of the DMS task with beta values of the peak voxels from the post‐treatment to the pre‐treatment in the left precuneus (r = 0.75) (Fig. 2). There were no significant correlations between brain activations and neuropsychological measures in the placebo group.

We conducted the correlations between the changes in behavioral performance and the changes in brain activation, partialing out ADHD symptoms of CGI‐ADHD‐S, ASRS‐I, and ASRS‐HI as covariates. For inhibitory control, there were significant correlations between the reaction times of the counting Stroop task and beta values of the peak voxels in the IFG and ACC from the post‐treatment to the pre‐treatment in the atomoxetine group (r = −0.63 and r = −0.70, respectively). No other correlations were significant in the placebo group. For visual processing, there were no significant correlations in either the atomoxetine group or the placebo group.

Regression Results for Prediction

For inhibitory control, the pre‐treatment ACC activation of the contrast of incongruent versus congruent condition in the atomoxetine group was predictive of the reduction of ADHD symptoms severity as assessed by the investigators' ratings on the CGI‐ADHD‐S, ASRS‐I, and ASRS‐HI (ß = −2.71, P = 0.02; ß = −15.61, P = 0.04; ß = −13.62, P = 0.07, respectively) after the 8‐week treatment with atomoxetine. There were no other significant findings in the placebo group. For visual processing, there were no significant findings in either the atomoxetine group or the placebo group.

DISCUSSION

The current study is the first double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomized clinical trial combining fMRI and the CANTAB to examine the efficacy of an 8‐week treatment with atomoxetine in improving inhibitory control and visual processing in drug‐naïve adults with ADHD. In contrast to no placebo effects on brain activation, atomoxetine decreased activation in the right IFG and ACC for inhibitory control; and increased activation in the left precuneus for visual processing. In addition, decreasing right IFG activation was correlated with the score of A', the probability of false alarm, and the probability of hit (RVP); decreasing right ACC activation was correlated with the score of A', the mean latency, the probability of false alarm, and the probability of hit; and increasing left precuneus activation was correlated with the latency of correct responses (DMS) in the atomoxetine group. Moreover, the ACC might play an important role as a treatment indicator of atomoxetine.

Decreasing right IFG and ACC activation correlating with improved RVP performance lends evidence to support our hypothesis that atomoxetine may enhance the performance of inhibitory control, a primary neuropsychological deficit in ADHD [Gau and Huang, 2014]. Our findings are in line with a recent clinical trial that atomoxetine improves the performance of inhibitory control in children with ADHD after a 12‐week treatment [Gau and Shang, 2010a]. In addition, our findings are supported by a recent head‐to‐head comparison study on executive functions in adults with ADHD, which reported drug‐specific improvement in attention with atomoxetine treatment for 8–10 weeks [Ni et al., 2013, 2017]. As the right IFG plays an important role in executive control and inhibition response [Cortese et al., 2012; Vaidya and Stollstorff, 2008], increased activity in this region may correspond to impaired response inhibition in children with ADHD in the counting Stroop task [Fan et al., 2014]. The ACC is also associated with inhibitory capacity [Chamberlain et al., 2009; Cortese et al., 2012], increased activity in this region may be correlated with inhibition failure in children with ADHD in the counting Stroop task [Fan et al., 2014]. Our results of the right IFG and ACC activation are consistent with those of single‐challenge doses of atomoxetine in healthy adults and treated children with ADHD [Chamberlain et al., 2009; Cubillo et al., 2014; Schulz et al., 2012]. Greater right IFG and ACC activation before atomoxetine treatment suggests that drug‐naïve adults with ADHD might need more inhibitory control to suppress interference between number and meaning. Therefore, decreased activation in the right IFG and ACC with post‐treatment suggests that atomoxetine might modulate activation in the right IFG and ACC to improve inhibitory control ability. In addition, the ACC activation in the pre‐treatment was predictive of the improvement of the clinical symptoms severity (CGI‐ADHD‐S).

Consistent with Schulz et al.'s [2012] study, we found the involvement of the right IFG related to atomoxetine treatment, suggesting that this region may play an important role in the therapeutic actions of long‐term atomoxetine treatment (6 to 8 week). In contrast, Schulz et al.'s [2012] used the go/no‐go task to examine response inhibition between two treatments (Methylphenidate versus Atomoxetine) in youths with ADHD. They found greater activation of the right IFG after 8‐week treatment with atomoxetine in youths with ADHD, suggesting that gains in this region may contribute to the improvements in response inhibition with atomoxetine treatment. As to the present study, we used the counting Stroop fMRI to examine inhibitory control in drug‐naïve adults with ADHD as compared to the placebo and the healthy control group. In our finding, atomoxetine decreased activation in the right IFG and ACC for inhibitory control after an 8‐week treatment with atomoxetine. The difference in right IFG activation between Schulz et al.'s [2012] study and the present study may be due to different control groups (Methylphenidate vs. placebo/healthy). Also, Schulz et al.'s [2012] study used youth participants, whereas the present study used adult participants.

Impaired visual processing is noted in children with ADHD [Shang and Gau, 2011, 2012] and less activation in the left parietal region may be involved in their impaired visual processing [Fan et al., 2014; Silk et al., 2008]. Our finding of the correlation between increasing left precuneus activation and increasing mean correct latency of the DMS after atomoxetine treatment suggests that treatment with atomoxetine may enhance the visual processing in drug‐naïve adults with ADHD. The finding of the effectiveness of atomoxetine in improving visual processing is consistent with our previous results in drug‐naïve boys [Shang and Gau, 2012] and adults [Ni et al., 2013] with ADHD using the CANTAB to assess visual processing; and a recent report that a 6‐week treatment with atomoxetine was associated with increased activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, parietal cortex, caudate, and cerebellum in adults with ADHD during the multi‐source interference task [Bush et al., 2013]. Taken together, our findings lend important evidence to support that atomoxetine might have influences on the left precuneus to improve visual processing of numbers during performing the counting Stroop task [Fan et al., 2014; Silk et al., 2008].

The performance IQ had a trend of difference with a P‐value of 0.09 between different groups. To determine whether IQ scores contributed to the clinical improvement (CGI‐ADHD‐S of post‐ vs. pre‐treatment) or the changes in brain activation, we examined the correlations between the performance IQ and the clinical improvement in the CGI‐ADHD‐S (post‐ vs. pre‐treatment) as well as activation differences. There were no significant correlations between the performance IQ and the clinical improvement or brain activations in the right IFG, ACC, and left precuneus. No significant correlations were also found in the verbal IQ or full‐scale IQ.

Several features of this study constitute its originality and significance: double‐blind, placebo‐control, longer treatment duration (8 weeks), drug‐naïve adults with ADHD, and the combination of the neuropsychological tests (CANTAB) and the counting Stroop task in the fMRI assessments to examine inhibitory control and visual processing. However, our findings should be interpreted with caution due to the methodological limitation that the small sample size of this study may result in a lack of enough power to demonstrate the superiority of atomoxetine in inhibitory control and visual processing. It warrants further investigations with larger samples and different experimental designs to validate our results of improving inhibitory control and visual processing with atomoxetine treatment. In addition, CGI may have limited value for assessing the severity of ADHD symptoms although CGI‐ADHD‐S has been widely used in clinical practice and studies. In this study, we also used the Chinese ASRS to assess the ADHD symptom changes pre‐ and post‐treatment. However, further studies will need to use other more comprehensive clinical assessments administered by the investigators to evaluate changes in clinical ADHD symptoms.

In conclusion, this study has three key findings. First, an 8‐week treatment with atomoxetine improved inhibitory control by decreasing the activation in the right IFG and ACC. The differential changes in brain activation of the two regions were correlated with the improvement of inhibitory control assessed by the RVP. Second, a positive correlation between increasing left precuneus activation, and increasing mean latency of correct response assessed by the DMS with treatment in the atomoxetine group implies that atomoxetine may enhance visual processing by increasing left precuneus activation to process the numbers. Most importantly, our findings of anterior cingulate activation in the pre‐treatment were predictive of the improvements of clinical symptoms. Taken together, our findings might expand the understanding of the effects of atomoxetine medication on the neural circuitry of inhibitory control and visual processing. Our results clearly contribute to knowledge about the efficacy of chronic treatments with atomoxetine in adults with ADHD on improving inhibitory control and visual processing beyond the clinically observable or neuropsychologically assessable.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Role of the sponsors: The supporters had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or publication of this study. Potential conflicts of interest: Dr. Gau serves on the advisory boards of Novartis Pharma AG on Glasgow, UK, Wednesday 27th May 2015 and has no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. This work is supported by National Health Research Institute, Taiwan. Dr. Fan and Dr. Chou have no conflicts of interest to be disclosed.

REFERENCES

- Burock MA, Buckner RL, Woldorff MG, Rosen BR, Dale AM (1998): Randomized event‐related experimental designs allow for extremely rapid presentation rates using functional MRI. Neuroreport 9:3735–3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Whalen PJ, Rosen BR, Jenike MA, McInerney SC, Rauch SL (1998): The Counting Stroop: An interference task specialized for functional neuroimaging—validation study with functional MRI. Hum Brain Mapp 6:270–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Holmes J, Shin LM, Surman C, Makris N, Mick E, Seidman LJ, Biederman J (2013): Atomoxetine increases fronto‐parietal functional MRI activation inattention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A pilot study. Psychiatry Res 211:88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna AE, Trimble MR (2006): The precuneus: A review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain 129:564–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Hampshire A, Müller U, Rubia K, Campo ND, Craig K, Regenthal R, Suckling J, Roiser JP, Grant JE, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2009): Atomoxetine modulates right inferior frontal activation during inhibitory control: A pharmacological functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry 65:550–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LR, Chiu YN, Wu YY, Gau SSF (2013): Father's parenting and father‐child relationship among children and adolescents with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Compr Psychiat 54:128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CY, Gau SS, Mao WC, Shyu JF, Chen YC, Yeh CB (2008): Relationship of attention‐deficit‐hyperactivity disorder symptoms, depressive/anxiety symptoms, and life quality in young men. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 62:421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HL, Chen YJ, Shang CY, Tseng WY, Gau SS (2016): Different neural substrates for executive functions in youths with ADHD: A diffusion spectrum imaging tractography study. Psychol Med 46:1225–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TL, Chia S, Shang CY, Gau SSF (2015): Differential therapeutic effects of 12‐week treatment of atomoxetine and methylphenidate on drug‐naïve children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A counting Stroop functional MRI study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25:2300–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S, Kelly C, Chabernaud C, Proal E, Martino AD, Milham MP, Castellanos FX (2012): Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: A meta‐analysis of 55 fMRI studies. Am J Psychiatry 169:1038–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubillo A, Smith AB, Barrett N, Giampietro V, Brammer MJ, Simmons A, Rubia K (2014): Shared and drug‐specific effects of atomoxetine and methylphenidate on inhibitory brain dysfunction in medication‐naive ADHD boys. Cereb Cortex 24:174–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Piazza M, Pinel P, Cohen L (2003): Three parietal circuits for number processing. Cogn Neuropsychol 20:487–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Égerházi A, Berecz R, Bartók E, Degrell I (2007): Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB) in mild cognitive impairment and in Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 31:746–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan LY, Gau SSF, Chou TL (2014): Neural correlates of inhibitory control and visual processing in youths with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A counting Stroop functional MRI study. Psychol Med 44:2661–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassbender C, Schweitzer JB (2006): Is there evidence for neural compensation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder? A review of the functional neuroimaging literature. Clin Psychol Rev 26:445–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SSF, Shang CY (2010a): Executive functions as endophenotypes in ADHD: Evidence from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB). J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51:838–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SSF, Shang CY (2010b): Improvement of executive functions in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: An open‐label follow‐up study with once‐daily atomoxetine. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 13:243–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SSF, Huang WL (2014): Rapid visual information processing as a cognitive endophenotype for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychol Med 44:435–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SSF, Huang YS, Soong WT, Chou MC, Chou WJ, Shang CY, Tseng WL, Allen AJ, Lee P (2007a): A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial on once‐daily atomoxetine in Taiwanese children and adolescents with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 17:447–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Kessler RC, Tseng WL, Wu YY, Chiu YN, Yeh CB, Hwu HG (2007b): Association between sleep problems and symptoms of attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder in young adults. Sleep 30:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SSF, Chen SJ, Chou WJ, Cheng H, Tang CS, Chang HL, Tzang RF, Wu YY, Huang YF, Chou MC, Liang HY, Hsu YC, Lu HH, Huang YS (2008): National survey of adherence, efficacy, and side effects of methylphenidate in children with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Taiwan. J Clin Psychiatry 69:131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf H, Abler B, Freudenmann R, Beschoner P, Schaeffeler E, Spitzer M, Schwab M, Grön G (2011): Neural correlates of error monitoring modulated by atomoxetine in healthy volunteers. Biol Psychiatry 69:890–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire A, Chamberlain SR, Monti MM, Duncan J, Owen AM (2010): The role of the right inferior frontal gyrus: Inhibition and attentional control. Neuroimage 50:1313–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix‐Cols D, Rubia K (2013): Meta‐analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Exploring task‐specific, stimulant medication, and age effects. JAMA Psychiatry 70:185–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs O, Henson RN (1999): Event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging: Modelling, inference and optimization. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 354:1215–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Jin R, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustun TB, Walters EE (2005a): The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self‐Report Scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med 35:245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler LA, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Faraone SV, Greenhill LL, Jaeger S, Secnik K, Spencer T, Üstün TB, Zaslavskya AM (2005b): Patterns and predictors of attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder persistence into adulthood: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 57:1442–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque J, Beauregard M, Mensour B (2006): Effect of neurofeedback training on the neural substrates of selective attention in children with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurosci Lett 394:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YJ, Yang LK, Gau SS (2016): Psychiatric comorbidities of adults with early‐ and late‐onset attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 50:548–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macey KD (2003): Conners' adult ADHD rating scales (CAARS). Arch Clin Neuropsych 18:431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Marquand AF, Simoni SD, O'Daly OG, Williams SC, Mouraõ‐Miranda J, Mehta MA (2011): Pattern classification of working memory networks reveals differential effects of methylphenidate, atomoxetine, and placebo in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 36:1237–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya A, Hervas A, Cardo E, Artigas J, Mardomingo MJ, Alda JA, Gastaminz X, García‐Polavieja MJ, Gilaberte I, Escobar R (2009): Evaluation of atomoxetine for first‐line treatment of newly diagnosed, treatment‐naïve children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Med Res Opin 25:2745–2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni HC, Shang CY, Gau SSF, Lin YJ, Huang HC, Yang LK (2013): A head‐to‐head randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate and atomoxetine treatment for executive function in adults with attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16:1959–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni HC, Hwang Gu SL, Lin HY, Lin YJ, Yang LK, Huang HC, Gau SS (2016): Atomoxetine could improve intra‐individual variability in drug‐naive adults with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder comparably with methylphenidate: A head‐to‐head randomized clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol 30:459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni HC, Lin YJ, Gau SS, Huang HC, Yang LK (2017): An open‐label, randomized trial of methylphenidate and atomoxetine treatment in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 21:27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakian B, Jones G, Levy R, Gray J, Warburton D (1989): The effects of nicotine on attention, information processing, and short‐term memory in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Br J Psychiatry 154:797–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahgal A (1987): Some limitations of indices derived from signal detection theory: Evaluation of an alternative index for measuring bias in memory tasks. Psychopharmacology 91:517–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MF, Krick CM, Retz W, Hengesch G, Retz‐Junginger P, Reith W, Rösler M (2010): Impairment of fronto‐striatal and parietal cerebral networks correlates with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) psychopathology in adults — A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study. Psychiatry Res 183:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KP, Fan J, Bédard ACV, Clerkin SM, Iliyan I, Tang CY, Halperin JM, Newcorn JH (2012): Common and unique therapeutic mechanisms of stimulant and nonstimulant treatments for attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69:952–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang CY, Gau SSF (2011): Visual memory as a potential cognitive endophenotype of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychol Med 41:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang CY, Gau SSF (2012): Improving visual memory, attention, and school function with atomoxetine in boys with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 22:353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang CY, Wu YH, Gau SSF, Tseng WY (2013): Disturbed microstructural integrity of the frontostriatal fiber pathways and executive dysfunction in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychol Med 43:1093–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang CY, Pan YL, Lin HY, Huang LW, Gau SS (2015): An open‐Label, randomized trial of methylphenidate and atomoxetine treatment in children with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 25:566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang CY, Yan CG, Lin HY, Tseng WY, Castellanos FX, Gau SS (2016): Differential effects of methylphenidate and atomoxetine on intrinsic brain activity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychol Med 30:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk TJ, Vance A, Rinehart N, Bradshaw JL, Cunnington R (2008): Dysfunction in the fronto‐parietal network in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): An fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav 2:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Treuer T, Gau SSF, Mendez L, Montgomery W, Monk JA, Altin M, Wu SH, Lin CCH, Duenas HJ (2013): A systematic review of combination therapy with stimulants and atomoxetine for attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, including patient characteristics, treatment strategies, effectiveness, and tolerability. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 23:179–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya CJ, Stollstorff M (2008): Cognitive neuroscience of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Current status and working hypotheses. Dev Disabil Res Rev 14:261–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (1997): WAIS‐III Nederlandstalige bewerking, technische handleiding. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. [Google Scholar]

- Yang HN, Tai YM, Yang LK, Gau SS (2013): Prediction of childhood ADHD symptoms to quality of life in young adults: Adult ADHD and anxiety/depression as mediators. Res Dev Disabil 34:3168–3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh CB, Gau SS, Kessler RC, Wu YY (2008): Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the adult ADHD Self‐report scale. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 17:45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information