In their recent article ‘Quaternary prevention: a balanced approach to demedicalisation’,1 Norman and Tesser (N&T) presented Kuehlein et al’s original definition of quaternary prevention as:

‘An action taken to identify a patient at risk of over-medicalization, to protect him from new medical invasion, and to suggest to him interventions which are ethically acceptable.’ 2

They concluded that this definition is more comprehensive than a new definition recently proposed by Brodersen et al:

‘Action taken to protect individuals (persons/patients) from medical interventions that are likely to cause more harm than good.’ 3

Here we elaborate further on this new definition that we strongly support and have already put into a general practice setting.4

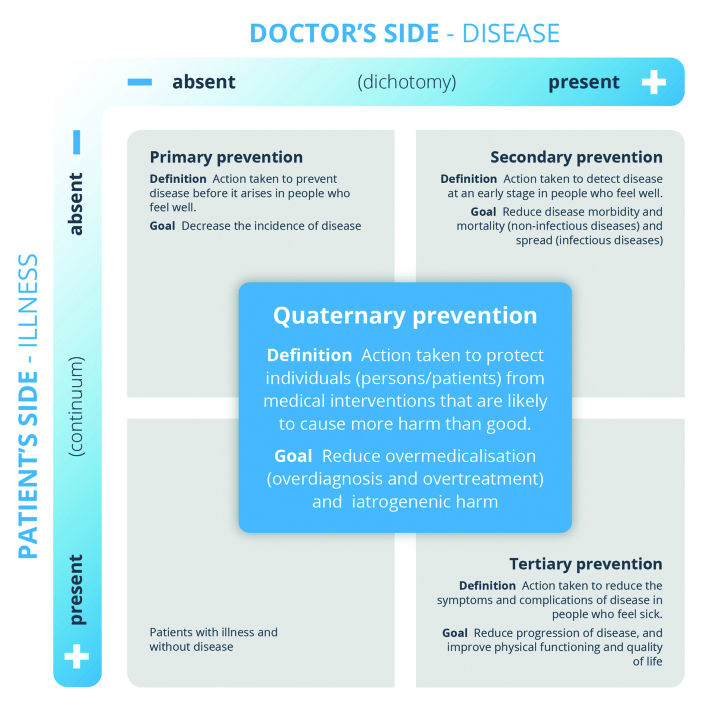

First of all, we agree that quaternary prevention needs to be globally disseminated and that further research may contribute to such dissemination. The two aforementioned definitions give different perspectives on the concept. Both of them address the risk of overmedicalisation. In contrast to the original definition,2 the one we support puts forward the idea that preventing medical harm must be present in all aspects of clinical activity (primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary prevention) more explicit. That is why in the visual representation of the definition, ‘quaternary prevention’ was moved from quadrant 4 to the centre of the figure.

We also think that the definition by Brodersen et al, places more emphasis on clinicians always considering the current best available evidence about the benefits and harms of an intervention. We believe this to be superior because it depicts the relationship between quaternary prevention and the evidence-based practice movement. In addition, considering a favourable ratio of benefits and harms, it also ensures that clinicians ‘protect’ people from unnecessary or harmful medical procedures and respect the ethical principles of non-maleficence and beneficence — although this is less explicit than in the original definition of quaternary prevention.

IT’S MORE THAN DEMEDICALISATION

In their defence of the original concept, N&T focus on the need for demedicalisation as the main feature of quaternary prevention. However, in our view, this is one of the main problems of the original quaternary prevention definition.

Demedicalisation is often not a science-based concept. There might be some medicalisation that may be needed and prove effective for patients, just as there is some medicalisation that is not needed and might potentially bring more harm than good to patients.

More important than preventing an excess of medical procedures (for example, treatments and diagnostic tests) is to prevent medical interventions that are likely to cause more harm than good based on high-quality scientific evidence.

By putting the focus on demedicalisation, we increase the risk of removing some medical interventions that could be more beneficial than harmful for patients, and by doing so we would indeed harm patients.

In quaternary prevention’s new definition,3 the focus is to prevent medical interventions likely to cause more harm than good. This definition incorporates the need for evidence-based clinical practice and implies that each medical intervention must be analysed according to this paradigm.5

LIMITATIONS OF THE FRAMEWORK

N&T’s framework is slightly different to Jamoulle’s original framework5 because a column referring to ‘demedicalisation’ has been added and also the beginning of the central clockwise arrow has been moved to the inside of the quaternary prevention field. N&T’s new framework presents two main problems: First, quaternary prevention level is still confined to the quadrant with patients that feel ill and do not have a disease. Second, visually, the central arrow could cause some confusion as it may be interpreted as indicating the sequence of prevention levels starting with quaternary prevention, then continuing to primary prevention, secondary prevention and, finally, tertiary prevention.

From our perspective, whichever quadrant patients may be in, they could benefit from quaternary prevention since they are all at risk of suffering harm from medical interventions. The quaternary prevention field has therefore been moved into the centre of the axes of illness and disease (Figure 1). In this way, understanding of the new definition is increased.

Figure 1.

Quaternary prevention: the new definition and the new Framework

CONCLUSION

To sum up, it’s not the medicalisation that has to be prevented, but medical interventions that are likely to cause more harm than good to patients. We believe that this new definition will support understanding and awareness of quaternary prevention, and encourage clinicians and patients to keep it in mind in all aspects of health care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Norman AH, Tesser CD. Quaternary prevention: a balanced approach to demedicalisation. Br J Gen Pract. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Kuehlein T, Sghedoni D, Visentin G, et al. Quaternary prevention: a task of the general practitioner. Prim Care. 2010;10(18):350–354. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodersen J, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosis: how cancer screening can turn indolent pathology into illness. APMIS. 2014;122(8):683–689. doi: 10.1111/apm.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martins C, Godycki-Cwirko M, Heleno B, Brodersen J. Quaternary prevention: reviewing the concept. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):106–111. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1422177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade MO, Cook DJ, editors. Users’ guides to the medical literature: essentials of evidence-based clinical practice. 3rd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015. [Google Scholar]