Abstract

The right temporoparietal junction (rTPJ) has been associated with the ability to reorient attention to unexpected stimuli and the capacity to understand others' mental states (theory of mind [ToM]/false belief). Using activation likelihood estimation meta‐analysis we previously unraveled that the anterior rTPJ is involved in both, reorienting of attention and ToM, possibly indicating a more general role in attention shifting. Here, we used neuronavigated transcranial magnetic stimulation to directly probe the role of the rTPJ across attentional reorienting and false belief. Task performance in a visual cueing paradigm and false belief cartoon task was investigated after application of continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) over anterior rTPJ (versus vertex, for control). We found that attentional reorienting was significantly impaired after rTPJ cTBS compared with control. For the false belief task, error rates in trials demanding a shift in mental state significantly increased. Of note, a significant positive correlation indicated a close relation between the stimulation effect on attentional reorienting and false belief trials. Our findings extend previous neuroimaging evidence by indicating an essential overarching role of the anterior rTPJ for both cognitive functions, reorienting of attention and ToM. Hum Brain Mapp 37:796–807, 2016. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: attention shifting, reorienting of attention, false belief, ToM, TPJ, TMS

INTRODUCTION

The right temporoparietal junction (rTPJ) has been frequently identified to be activated during distinct cognitive tasks, such as spatial attention and social interaction [Decety and Lamm, 2007; Mars et al., 2012; Mitchell, 2008; Vogeley et al., 2001; Young et al., 2010a]. This common activation might stem from a mechanism underlying both spatial attention and social cognition tasks, i.e., a rather general shifting or reorienting of attention [Corbetta et al., 2008; Van Overwalle, 2009]. In particular, the rTPJ encodes unexpected, but potentially task‐relevant stimuli [Chang et al., 2013; Corbetta and Shulman, 2002; Diquattro et al., 2013; Hrabetova and Sacktor, 1997; Vossel et al., 2006]. This function may represent a “breach of expectation” [Corbetta et al., 2008] or a “where‐to‐shift” [Van Overwalle, 2009] in order to react to an unexpected, external event—as seen in attention tasks, including the Posner task or oddball task [Bledowski et al., 2004; Corbetta et al., 2008; Decety and Lamm, 2007; Vossel et al., 2008a]. A similar mechanism may be involved in responding to somebody else's mental state—as seen in social interaction tasks, i.e., in Theory of Mind (ToM), morality, or self‐other distinctions [Arrington et al., 2000; Blanke et al., 2005; Chistyakov et al., 2010; Corbetta et al., 2000; Jakobs et al., 2009; Macaluso et al., 2002; McAllister et al., 2009; Prado et al., 2005; Young et al., 2010b]. For example, in false belief tasks participants have to perform a shift between mental states and have to breach with their former expectation (true belief) to understand that others have a false belief about a certain situation [Krall et al., 2015]. Accordingly, it was proposed that a shift between mental states (as tested in false belief tasks) can be interpreted in terms of attention shifting implying a common cognitive function of the rTPJ for both spatial attention and social interaction tasks (see Mitchell [2008] for alternative hypotheses discussing a “belief formation” potentially involved in reorienting of attention).

Further support for an overarching cognitive role of the rTPJ stems from our recent activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta‐analysis [Krall et al., 2015]. Multiple neuroimaging studies investigating spatial attention and social interaction (using attention tasks or false belief tasks) were included. Our findings suggested that the anterior part of the rTPJ was involved in both, reorienting of attention and ToM. Hence, this overlap strongly encouraged the idea of a common attention shifting function of the anterior rTPJ underlying spatial attention and social interaction.

Lesion studies offer additional—albeit inconclusive—evidence regarding the concurrent involvement of the rTPJ in spatial attention and social interaction. While deficits in reorienting of attention and spatial neglect are known to be associated with lesions of the rTPJ [Gillebert et al., 2011; Mort et al., 2003], preliminary case studies suggest that unilateral rTPJ damage does not necessarily impair the ability to attribute a belief to another person [Leigh et al., 2013; Shamay‐Tsoory et al., 2003]. Thus, contrary to our and other meta‐analyses of imaging studies [Bzdok et al., 2013; Decety and Lamm, 2007], lesion data challenge the view of a causal role of the rTPJ (and a potential shared cognitive underlying function) common to both spatial attention and social interaction. However, limitations of lesion studies [i.e., large middle cerebral artery strokes impeding any conclusions on specific rTPJ functions; Corbetta et al., 2005] hinder final conclusions on a common role of the rTPJ.

Brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) are more suitable to investigate a direct involvement of the rTPJ across different cognitive tasks due to the creation of focal lesions in healthy subjects. Aforementioned studies raise the question whether inducing a virtual lesion in the anterior part of the rTPJ by means of repetitive TMS might differentially affect reorienting of attention [Posner et al., 1980] and attribution of false beliefs [Gallagher et al., 2000].

We, therefore, applied neuronavigated inhibitory continuous theta burst stimulation [cTBS; Huang et al., 2005] either over the anterior rTPJ (experimental site) or the parieto‐occipital vertex (control site) before the performance of a Posner task [Posner et al., 1980] and a false belief task, an adapted version of Gallagher's cartoon task [Gallagher et al., 2000] in 20 healthy, right‐handed subjects. These tasks fulfill the requirements for a breach of expectation [Corbetta et al., 2008] and mental state shifting [Van Overwalle, 2009] expected to form the basis of a common cognitive attention shifting mechanism potentially representing an overarching role of the anterior rTPJ. This is based on the assumption that attention shifting is needed after an invalid cue measured in the Posner task, reflecting a behaviorally relevant response to an unexpected event. For a false belief, the very same capacity is expected to be required during mental state shifting to further understand a false belief in the cartoon task. Thus, the main goal of this TMS study was to disentangle the direct involvement of the anterior rTPJ in attention shifting capacities associated with reorienting of spatial attention and false belief.

We hypothesized that an inhibition of the anterior rTPJ (compared with vertex stimulation) by means of cTBS would lead to (i) a higher validity effect in the Posner task (i.e., longer reaction times [RTs] and more errors in invalid trials), and (ii) an increase in error rates in false belief trials (involving a shift in mental states) in contrast to non‐false belief trials (not involving attribution of a false belief). Furthermore, assuming a common overarching mechanism of the anterior rTPJ to redirect attention in both tasks, we predicted (iii) a significant correlation between the effect of stimulation in the Posner task and the effect of stimulation in the false belief task. Confirming these hypotheses would not only provide support for a significant role of the anterior rTPJ in reorienting of spatial attention and false belief tasks but also strengthen the concept of an overarching role of the anterior rTPJ possibly reflecting a more general role of the rTPJ in attention shifting.

METHODS

Participants and Design

Twenty‐four right‐handed, native German‐speaking adults with no history of neurological or psychiatric disease participated and were reimbursed with money. Four subjects were excluded from analyses due to technical problems or performance at chance level in the reorienting of attention task, leaving a final data set of 20 participants (11 females, mean age = 27.7 years, standard deviation [SD] = 4.5). Before participation, written informed consent in accordance with the local ethical committee (RWTH Aachen, Germany) and with the principles of the revised Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Associations General Assembly 2008) was obtained from each subject.

Participants were asked to fill out self‐rating questionnaires on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; Selbstbeurteilungs—Skala zur Diagnostik der Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit‐/Hyperaktivitätsstörung im Erwachsenenalter [ADHS‐SB]) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD; German version of the Autism Spectrum Quotient), because both, ADHD and ASD, are frequently associated with attentional and social interaction disturbances [Baron‐Cohen et al., 2001; Rosler et al., 2008]. None of the participants showed abnormal scores on the ADHS‐SB (mean = 6.7, SD = 4.14) or the AQ (mean = 16.25, SD = 4.62).

A within‐subject design was employed with each participant undergoing stimulation of both the experimental (anterior rTPJ) and control (vertex) site on 2 consecutive days (with the exception of one participant being stimulated with 1 day apart) to avoid any potential TMS carryover effects. Sessions were scheduled at similar daytimes on both measurement days for each participant. Both the order of stimulation (nine subjects were vertex‐stimulated and eleven subject were anterior rTPJ‐stimulated on the first day) and task‐order (11 subjects started with the reorienting of spatial attention task and nine with the false belief task) were counterbalanced across participants.

TMS Navigation and Protocol

TMS sessions were performed in a neuronavigated fashion using structural T1‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans acquired on a 3 T Siemens Trio scanner with a 12‐channel phased‐array head coil. A three‐dimensional (3D) magnetization prepared, rapid acquisition gradient echo (MP‐RAGE) pulse sequence (TE = 3.03 ms, TR = 2,000 ms, TI = 900 ms, α = 9°, FOV = 256 mm, voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm³, matrix size = 256 × 256, 176 sagittal slices, slice thickness = 1 mm) was used to get individual T1‐weighted MRI scans. Image data were analyzed using SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8/). Standard normalization steps were performed involving realignment and normalization of structural MRI scans of each subject to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template brain. Thereafter, the activation cluster for the anterior rTPJ (peak MNI‐3D‐coordinate: x = 54, y = −44, z = 18) obtained in the previous ALE‐meta‐analysis [Krall et al., 2015] was transformed into each individual's space using the transformation matrix derived from the normalization of the inverted individual MRI to the MNI template brain (see Fig. 1 for an overview of individual stimulation peaks). Note, that the rTPJ is generally characterized by great inter‐individual variability in anatomical structure and cytoarchitecture [Caspers et al., 2006].

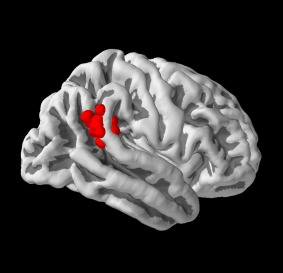

Figure 1.

Individual stimulation points in the anterior right temporoparietal junction for all subjects. Note that individual Brainsight coordinates had to be linearly transformed into MNI space for visualization which might have led to small deviations from original stimulation points (Pysurfer; http://pysurfer.github.io).

TMS‐coil placement was guided and recorded via a frameless stereotaxic neuronavigation system (Brainsight2, Rogue Research, Montreal, Canada). The stimulation target was defined by the overlay of the transformed rTPJ activation cluster on the individual (non‐normalized) structural MRI reconstruction. Appropriate stimulation targets for each participant were defined and preserved throughout the experiment (for both anterior rTPJ and vertex stimulation site). Real‐time monitoring ensured precise coil location and accurate stimulation throughout the experiment.

A Magstim SuperRapid stimulator (The Magstim Company, Whitland, UK) equipped with a 70 mm figure‐of‐eight coil was used to apply cTBS. A total of 600 pulses within 40 s were administered, involving three pulses at 50 Hz repeated every 200 ms [5 Hz; Huang et al., 2005]. The stimulation intensity was set to 30% of maximum stimulator output (MSO). A fixed stimulation protocol was chosen as individual resting motor thresholds are not representative of parietal thresholds [Chang et al., 2013; Stewart et al., 2001]. We used 30% MSO as higher intensities were not tolerated by the subjects according to our pre‐experimental tests due to painful co‐stimulation of the temporal muscles. Furthermore, a fixed intensity ensured a more consistent spatial spread of TMS effects in subjects' brains not influenced by differences in individual motor thresholds. For anterior rTPJ stimulation, the coil was oriented antero‐posteriorly with the handle pointing posteriorly, thereby inducing posterior‐anterior current in the human brain [Young et al., 2010a]. The parieto‐occipital vertex was chosen as control‐stimulation site [Herwig et al., 2010]. This control site ensured not only a low efficacy in stimulation and thus improbable stimulation effects on the subjects' brains, but also provided the characteristics of noise and sensation associated with the real stimulation. We opted for vertex control stimulation, as right or left parietal control regions would have introduced the danger of unspecific functional and/or structural connectivity effects infeasible to disentangle from experimental stimulation effects [see Bestmann et al., 2005 or Nettekoven et al., 2014 for TMS effects on associated neural networks]. The duration of cTBS effects in disrupting activity in the stimulated brain region was expected to last at least 25 to 45 min [Huang et al., 2005]. The total length of both tasks performed after the stimulation was restricted to a maximum length of 20 min based on a conservative estimation of the duration of the cTBS effects [Young et al., 2010a].

Experimental Stimuli and Tasks

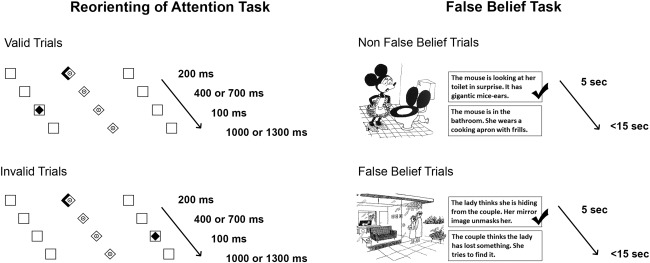

Reorienting of spatial attention task

Reorienting of spatial attention was investigated using an adapted version of Posner's location‐cueing task [see Fig. 2; an adapted version of Vossel et al., 2008b; Posner and Petersen, 1990]. Participants sat in a dimly lit room approximately 70 cm from a Samsung Sync‐Master 2233 video monitor (Seoul, South Korea) with their head position stabilized by a chin‐ and headrest. The spatial resolution of the monitor was set to 800 × 600 pixels at a refresh rate of 60 Hz. All responses were made with the right hand via a LUMItouch response keypad (Photon Control Inc., Burnaby, Canada). Participants were presented with two horizontally arranged boxes (1.6° wide and 7.1° eccentric in each visual field). A central diamond (0.8° eccentric in each visual field) was placed in between the two boxes serving as fixation point. Central predictive cues were shown to indicate whether a target appeared on the right or left side of the screen [Dayan and Cohen, 2011; Giessing et al., 2004; Mayer et al., 2004; Posner and Petersen, 1990]. These cues consisted of a 200 ms long brightening of one side of the diamond depicting an arrowhead pointing to one of the two peripheral boxes. After a variable cue‐target stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) of 600 or 900 ms, the cue was followed by the presentation of the target (a black diamond) appearing for 100 ms in one of the two lateral boxes. The actual target was presented on the cued side (valid trials) on 80% of the trials, and on the remaining 20% of trials the target appeared on the opposite position (invalid trials). The target‐cue SOA was either 1,100 ms or 1,400 ms (depending on cue‐target interval), leading to a repetition of randomly presented trials every 2,000 ms. Participants were instructed to respond as quickly and accurate as possible by a button press with the index (target on the left side) or middle finger (target on the right side) of their right hand. Subtraction of invalid minus valid trials depicted the validity (reorienting) effect, displaying the costs (measured by RTs and amount of errors) to shift attention from a cued to an uncued target.

Figure 2.

Illustration of experimental tasks.

In total, the reorienting of spatial attention task consisted of 200 trials including 160 valid (with 80 targets on left side and 80 targets on right side) and 40 invalid trials (with 20 targets on left side and 20 targets on right side), and lasted for about 7 min. Fixation was controlled by online eye‐tracking (EyeLink 2000 system, SR Research). Unfortunately, technical errors (i.e., the eye‐tracking system failed to detect the pupil) caused the loss of eye‐tracking data after vertex stimulation for one participant. The system detected a start and an end of a saccade when eye velocity exceeded or fell below 22 deg/s2 and acceleration was above or below 4,000 deg/s2. Artifacts related to eye‐blinks were filtered out. Fixation zone was defined as a region of interest subtending 2° of the cue‐target distance from the center. For each participant, each validity condition and each stimulation site the number of saccades were calculated. Note that in addition to online eye‐tracking by the EyeLink 2000 system (SR Research) subjects' fixation was monitored by visual inspection throughout the task. Before performing the task on the first measurement day, participants were informed about the cue validity and completed a practice session of 20 trials (16 valid; 4 invalid). The task was repeated on both measurement days after either anterior rTPJ or vertex stimulation.

For statistical analyses, inverse efficiency scores (IES) for each participant per condition (invalid and valid trials) and per stimulation site (anterior rTPJ and vertex) were calculated to generate a combined, reliable measure of mean RTs and error rates into a single measure [Townsend and Ashby 1983]. IES have repeatedly been employed as a standard, robust measure of participant's performance in multiple studies testing spatial attention [Bauer et al., 2012; Kristjansson et al., 2010; Murphy and Klein, 1998; Wykowska et al., 2014]. Hereby, mean RTs were divided by the proportion of correct trials responded to in a specific condition. Since RTs and accuracy (percentage correct) showed signs of differential trade‐offs across conditions (valid versus invalid trials), the calculation of IES provided a way to process efficiency independent of eventual criterion shifts or speed‐accuracy trade‐offs [Lange‐Malecki and Treue, 2012; Spence et al., 2001; Teufel et al., 2010]. Thereby, valid reflection of subjects' performance in the Posner task was ensured. Furthermore, all raw RTs below 100 ms were dismissed to exclude unintentional startle responses.

False belief task

False belief was tested by an adapted version of Gallagher's cartoon task [see Fig. 2; Gallagher et al., 2000]. In the present study two types of pictures were presented, “false belief cartoons” (originally referred to as “theory of mind cartoons”) and “non‐false belief cartoons” (originally referred to as non‐theory of mind cartoons). Cartoons were considered as involving a “false belief” if either a false belief or ignorance had to be attributed to at least one of the cartoon‐characters for comprehension. Non‐false belief cartoon stimuli did not necessitate a mental state attribution to understand the meaning, but required a situational description. Cartoon stimuli were validated in a previous study performed by Gallagher et al. [2000]. This was done in accordance with (i) the understanding of the content of the cartoon (either false belief or non‐false belief), and (ii) the degree to what extent cartoon stimuli were considered as funny. No significant differences were identified in any of the measures between the two types of pictures.

During each TMS session 15 false belief and 15 non‐false belief cartoon stimuli were presented centrally on the computer screen. In total, the participants were confronted with 30 false belief and 30 non‐false belief stimuli across both stimulation days. The cartoon stimuli were randomized across participants and stimulation days. The general experimental set‐up was identical as described for the reorienting of spatial attention task. None of the stimuli were depicted on both measurement days. Due to a programming error, the first two subjects only saw 14 false belief and 14 non‐false belief stimuli on the second day of measurement, leading to a reduced number of trials in these participants for the false belief task. Furthermore, individual object stimuli were investigated, identifying those cartoon pictures being answered below chance level, suggesting consistent misinterpretation. Accordingly, one object stimulus of the false belief condition and two object stimuli of the non‐false belief condition were excluded from further analyses.

Subjects were instructed to look at the depicted cartoon for 5 s and to consider the meaning of the stimuli silently. Afterwards two sentences were visually added underneath the cartoon picture and horizontally positioned next to each other for a total length of 15 s, involving (i) the correct inference and (ii) an incorrect/inappropriate inference (Fig. 2). Before the experiment, participants were asked to keep the following question in mind when responding to the answering options: “Which of the two sentences describes the humor of the cartoon better?” The phrasing of this question prevented that attention was specifically drawn to false belief/non‐false belief aspects of the task, but still required active examination of what was seen on the cartoon stimuli. Participants were instructed to respond as fast and accurate as possible with their index or middle finger of their right hand via LUMItouch button press (Photon Control Inc., Burnaby, Canada). The side for the correct response (right vs. left) was randomized across conditions (false belief vs. non‐false belief).

After each participant's response to one of the sentences, subjects were asked to evaluate the difficulty of assigning one of the two sentences to the cartoon picture (“How difficult was it to rate the humor?”). For this purpose, the words “easy” and “difficult” appeared on the computer screen until participants responded. Subjects were asked to respond by button press with their right index finger for “easy” and their right middle finger for “difficult.” This ensured the identification of those participants generally perceiving the task as easy versus difficult, potentially leading to a lesser or greater amount of errors, respectively. Accuracy in the false belief task was generally expected to be high as seen in previous studies investigating false belief [Fletcher et al., 1995; Rothmayr et al., 2011; van der Meer et al., 2011]. Therefore, including an overall difficulty rating per subject as a covariate in our statistical analyses decreased the influential risk of false positives and/or ceiling effects in performance. The combination of accuracies and difficulty ratings consequently reflects a measure of subjects' subjective and objective performance, thereby leading to a better estimation of actual performances. Statistical analyses did not include RT as dependent variable as individual reading speed can vary in subjects across false belief and non‐false belief trials [Saxe and Powell, 2006] and hence does not represent a reliable measure of performance differences. In our adapted version of Gallagher's cartoon task [Gallagher et al., 2000], subjects needed more time to answer false belief cartoons (mean = 6.8 s, SD = 1.4) than non‐false belief cartoons (mean = 6.4 s, SD = 1.2) which was investigated in a 2 (condition: false belief vs. non‐false belief) × 2 (stimulation: anterior rTPJ vs. vertex) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) showing a significant main effect of condition [F (1,19) = 4.44, P = 0.003]. Note, that there was no main effect of stimulation and no interaction between condition and stimulation for RT (all P > 0.49). To exclude premature responses or “guessing,” i.e., late responses merely made to avoid non‐responsiveness, RTs were used to identify those trials where participants needed significantly less or more time than on average (±2 SD from mean). These trials were further counted as error. Across all subjects, in the false belief conditions after vertex stimulation 1.7% of the trials were counted as errors and after anterior rTPJ stimulation 2.8% of the trials were counted as errors. In the non‐false belief conditions after vertex stimulation 2.8% of the trials were counted as errors and after anterior rTPJ stimulation 2.2% of the trials were counted as errors. Note that there were no trials where participants had a RT below 2 SD from the mean. Furthermore, there was no significant Spearman ρ correlation between RT and difficulty rating in none of the conditions. This indicates that long RTs per condition per stimulation were not related to perceived difficulty, but rather indeed reflect difficulties in understanding the (non‐) false belief in the cartoons. Mean duration of the false belief task was approximately 10 min. Before performing the task on the first measurement day, participants saw two examples of a false belief and a non‐false belief cartoon and were familiarized with the task.

Combined measure of reorienting of spatial attention and false belief

To finally examine whether stimulation effects in trials testing “attention shifting” were related, (i) IES in invalid trials in the reorienting of spatial attention task (IES for invalid trials after anterior rTPJ stimulation minus IES for invalid trials after vertex stimulation), and (ii) error rates in false belief trials in the false belief task (error rates for false belief trials after anterior rTPJ stimulation minus error rates for false belief trials after vertex stimulation) were investigated. These trials implied the capacity to shift attention, either to unexpected targets (invalid trials in the reorienting of spatial attention task) or to another person's false belief (false belief trials in the false belief task). The magnitude of stimulation effects was estimated by subtracting performance scores after vertex stimulation from performance scores after anterior rTPJ stimulation. Worse performance (longer RT and/or more errors) was expected following anterior rTPJ stimulation compared with vertex stimulation.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics version 21. Please find all details on statistical analyses in the following Results section.

RESULTS

Reorienting of Spatial Attention Task

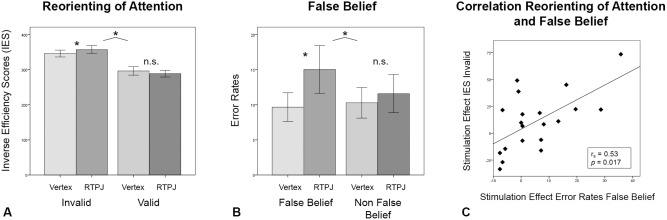

The effects of stimulation on participants' IES in the reorienting of attention task were analyzed in a 2 (condition: invalid vs. valid trials) × 2 (stimulation: anterior rTPJ vs. vertex) repeated measures ANOVA. There was a significant main effect of condition [F (1,19) = 53.49, P = 0.00, r = 0.86], indicating that mean IES for invalid trials (mean = 351.4, SE = 10.1) were significantly higher than IES for valid trials (mean = 292.5, SE = 10.4). In addition, an interaction effect between condition and stimulation (F (1,19) = 5.3, P = 0.03, r = 0.47] was found which was due to increased IES in the invalid condition (mean = 357, SD = 51) compared with the valid condition (mean = 288.6, SD = 42.7) following cTBS to the anterior rTPJ (Fig. 3). The mean validity effects were calculated by subtracting IES in valid trials from IES in invalid trials. Therefore, this interaction effect reflects a significant modulation of the validity effect after experimental stimulation compared with vertex stimulation. Participants thus showed a significant increase in mean validity effect IES after anterior rTPJ stimulation (mean = 68.4, SD = 46.1) compared with vertex stimulation (mean = 49.5, SD = 34).

Figure 3.

(A) Results for reorienting of spatial attention task. Significant interaction of condition (invalid and valid trials) and stimulation (vertex [light bars] vs. anterior rTPJ [dark bars]). Mean IES was significantly increased in invalid trials after anterior rTPJ stimulation compared with vertex stimulation. (B) Results for false belief task. Significant interaction of condition (false belief and non‐false belief trials) and stimulation (vertex [light bars] versus anterior rTPJ [dark bars]). Mean error rate (in percentages) was significantly increased in false belief trials after anterior rTPJ stimulation compared with vertex stimulation. (C) Result for correlation of reorienting of spatial attention and false belief tasks. The stimulation effect for error rates in false belief trials and for IES in invalid trials correlated significantly. Bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05.

Further investigation of effects in paired‐sampled t‐tests for invalid and valid trials separately showed that only IES in invalid trials were significantly increased after experimental stimulation in contrast to control stimulation [T (19) = −1.83, P = 0.04, d = 0.41, one‐tailed]. IES for valid trials did not differ between experimental and control stimulation [T (19) = 1.2, P = 0.25].

No interactions or correlations were found between condition, stimulation, and order of stimulation site (that is whether the anterior rTPJ or vertex was stimulated on day 1 or 2) or order of tasks (that is whether the false belief or Posner task was first) as investigated in a 2 (condition: invalid vs. valid trials) × 2 (stimulation: anterior rTPJ vs. vertex) repeated measures ANOVA with order of stimulation and order of tasks as between‐subject factors. Additionally, the side of stimulus‐presentation (right vs. left visual field) did not lead to an interaction effect or correlation with conditions or stimulation sites as investigated by a three‐way ANOVA (condition × stimulation × side of stimuli‐presentation; all P > 0.05). However, a main effect of side of stimulus‐presentation [F (1,19) = 8.79, P = 0.008, r = 0.56], indicating that subjects had higher IES when the target was presented on the left side compared with the right side, was detected.

A 2 (condition: invalid vs. valid trials) × 2 (stimulation: anterior rTPJ vs. vertex) repeated measures ANOVA on eye movement data showed that there were no significant main or interaction effects regarding the number of saccades between conditions and stimulation sites (anterior rTPJ stimulation: valid trials: mean = 8.2, SD = 9.8; invalid trials: mean = 10.3, SD = 15.8; vertex stimulation: valid trials: mean = 5.8, SD = 6.4; invalid trials: mean = 7.5, SD = 8.7; all P > 0.1). This clearly indicates that cTBS effects investigated in the reorienting of spatial attention task were not influenced by any differences in participants' eye movements.

False Belief Task

The effects of the stimulation on participants' error rates (note that all values reflect error percentages) were investigated by a 2 (condition: false belief vs. non‐false belief) × 2 (stimulation: anterior rTPJ vs. vertex) repeated measures ANCOVA including mean difficulty rating (across both conditions) per subject as covariate (Fig. 3). A significant interaction effect between condition and stimulation was found [F (1,18) = 4.44, P = 0.05, r = 0.45]. The investigation of simple effects (paired sample t‐tests) showed that errors after anterior rTPJ stimulation (mean = 15, SD =15.2) compared with vertex stimulation (mean = 9.7, SD = 9.1) were only increased for the false belief condition [T (19) = −1.98, P = 0.03, d = .44, one‐tailed]. By contrast, there was no significant difference between experimental (mean = 11.6, SD = 12.2) and control stimulation (mean = 10.3, SD = 9.1) for the non‐false belief condition [T (19) = −0.44, P = 0.66). Again, there was no interaction regarding order of stimulation as investigated by a 2 (condition: false belief vs. non‐false belief) × 2 (stimulation: anterior rTPJ vs. vertex) repeated measures ANCOVA (difficulty as covariate) with order of stimulation as between‐subject factor [F (1,17) = 3.63, P = 0.07]. An additional 2 × 2 repeated measures ANOVA on difficulty ratings showed no main and no interaction effects (all P > 0.13). Perceived difficulty (in percentages) for false belief tasks after anterior rTPJ stimulation (m = 17.4, SD = 11.27) was not significantly higher than after vertex stimulation (m = 13.5, SD = 10.4), just as there was no difference in difficulty ratings in the non‐false belief condition after vertex (m = 21.3; SD = 15.6) and anterior rTPJ stimulation (m = 18.9; SD = 13.2) as investigated in paired sample t‐tests (all P > 0.31).

Correlation between reorienting of attention and false belief tasks

To analyze the relation of stimulation effects, we performed bivariate Spearman ρ correlation analyses on (i) the difference IES in invalid trials calculated by subtracting vertex from anterior rTPJ stimulation in the reorienting of spatial attention task, and (ii) on the difference in error rates in false belief trials calculated by subtracting vertex from anterior rTPJ stimulation in the false belief task. The inclusion of stimulation effect scores on invalid IES and false belief error scores insured that solely those trials were included in the correlation analyses assumed to involve attentional shifting. A significant positive correlation was evident between the stimulation effects of anterior rTPJ stimulation in IES in invalid trials and the stimulation effect of anterior rTPJ stimulation in error scores in the false belief trials [r s(20) = 0.53, P = 0.017; Fig. 3]. Thus, the extent of stimulation effect in each participant was significantly related between both tasks, meaning those participants who showed worse performance after anterior rTPJ stimulation compared with vertex stimulation in invalid trials also displayed worse performance in false belief trials (and vice versa). Overall, seven subjects showed a positive stimulation effect in both IES in invalid trials in the reorienting of attention task and in error rates in false belief trials in the false belief task (see also Fig. 3C). In contrast, two subjects in the spatial reorienting task, six subjects in the false belief task, and five subjects in both tasks did not show a stimulation effect. The correlation was not due to unspecific individual modulation capabilities since the correlation between IES in invalid trials and error scores in false belief trials after vertex stimulation was not significant [r s(20) = 0.25, P = 0.297], as investigated using an additional bivariate Spearman ρ correlation analysis. Therefore, the significant positive correlation of stimulation effects (worse performance) between invalid trials and false belief trials was solely attributable to the experimental cTBS stimulation.

DISCUSSION

The current cTBS‐study tested the influence of the anterior part of the rTPJ on the performance in a reorienting of spatial attention and false belief task. Results indicate that an inhibition of the anterior rTPJ (compared with vertex stimulation) led to behavioral dysfunction in both tasks as reflected in a significantly higher validity effect in the reorienting of spatial attention task and a significantly higher error rate in false belief trials in the false belief task. Of note, cTBS‐induced behavioral deficits were significantly correlated across both tasks implying a common mechanism underlying these behavioral changes. Thus, these findings suggest a strong involvement of the anterior rTPJ in spatial attention and social interaction abilities, indicating an overarching role of the anterior rTPJ.

This might be interpreted in support of the concept of a more general, cognitive role of the anterior rTPJ in attention shifting. Such a common cognitive attention shifting mechanism of the anterior rTPJ underlying both reorienting of spatial attention and false belief tasks might be based upon the idea of a bottom‐up “circuit breaker” function of the rTPJ [Corbetta et al., 2008]. Accordingly, in response to the appearance of an invalidly cued target or a switch in former expectations to understand another person's false belief, a breach in expectation/attention shift is initialized by the rTPJ. Stimulus‐driven/bottom‐up reorienting might be elicited through peoples' reactions to unexpected events or targets. These unexpected events might indicate a specific event boundary marking discrepancies in expectancy and thereby require an update of the current model. This concept is supported by a repetitive (r) TMS—electroencephalography (EEG)—study by Capotosto et al. [2012]: disturbance of the right intraparietal sulcus during the presentation of a central arrow cue in a Posner spatial cueing task via rTMS led to impaired detection of invalid but not valid targets. Accordingly, we here also found a specific stimulation effect on invalid trials, reflected by higher IES solely for invalid trials and not valid trials. Likewise, for the false belief task, an effect of anterior rTPJ stimulation was uniquely observed for false belief trials and not non‐false belief trials. An explanation for these findings might be that in contrast to invalid trials and false‐belief trials, valid trials and non‐false belief trials demanded focused attention and evaluation of a specific situation depicted in the cartoons, but did not require an attention‐shift. Hence, both findings corroborate the view that the anterior rTPJ is crucially involved in modulating attention. Here, a ‘circuit break’ signal may interrupt the dorsal attention network (associated with focused attention) and trigger the ventral attention network (linked to shifting attention) after the appearance of an invalid target or another's false belief [Greene and Soto, 2014; Kucyi et al., 2012; Vossel et al., 2014, 2012]. Note, however, that this interpretation remains speculative since our TMS findings per se do not allow clear inferences on the detailed and potentially multifactorial cognitive mechanisms of the rTPJ.

An alternative interpretation of rTPJ function is proposed by a review suggesting that the rTPJ might encode expectations regarding the exact relationship between the sensory stimulus and the context‐appropriate response [cf. Geng and Vossel, 2013]. Accordingly, the rTPJ may initiate a conceptual update when needed due to a top‐down re‐evaluation of the context instead of a bottom‐up response. This hypothesis implies a broader, more unspecific involvement of the rTPJ impacting on both invalid and valid trials in the reorienting task due to a general top‐down modulation by the rTPJ. Support for this hypothesis stems from a recent fMRI study showing a more general involvement of the rTPJ both in invalid and valid trials [Diquattro et al., 2013]. However, Diquattro et al. [2013] also found that the involvement of the rTPJ was greater in the invalid condition (target‐color distractor condition) compared with valid and neutral conditions. Unfortunately, direct comparison to (our) classic reorienting task (involving 80% valid and 20% invalid trials) is limited due to the equal distribution of conditions in their study. Generally, the authors assumed that the rTPJ rather plays a contextual updating role than being a circuit‐breaker. This conclusion was additionally built on their dynamic causal modeling analysis indicating that the right frontal eye fields (rFEF) had a causal effect (negative modulation) on the rTPJ, and not vice‐versa. Still, although DiQuattro et al. [2013] assign a more contextual role to the rTPJ instead of an interrupting role as proposed by the “circuit breaker” account, both results indicate that the rTPJ is specifically associated with trials requesting an update whenever responses deviate from expectations.

Alternatively, rTPJ might be involved in both bottom‐up (early) and top‐down (later) reorienting. For example, Chambers et al. [2004] found that a post‐cue disruption of the right angular gyrus via TMS in a cued attention task specifically reduced the accuracy in invalid trials but not valid trials. Of note, stimulation during bottom‐up processing, i.e., early after the cue (at 90–120 ms) and interference of top‐down computation (stimulating at 210–240 ms) both resulted in altered invalid trial performance. Hence, taken together, data suggest that the rTPJ is significantly involved in the processing of invalid trials and the initiation of a breach of expectation [Corbetta et al., 2008], but is not necessarily implicated in valid trials. This view does not entirely rule out the possibility that there still might be some form of top‐down modulation through a conceptual update in the rTPJ [Geng and Vossel, 2013], but it clearly indicates that the effect is not globally influencing invalid and valid trials. Future TMS studies may specifically address this issue by using online stimulation [cf. Chambers et al., 2004] and adapted versions of spatial attentional and socio‐cognitive tasks with comparable task stimuli and timing aspects.

Besides the spatial attention task, we here used a false belief task to test whether the anterior rTPJ might represent “attention shifting” in a more general way, i.e., not only with regard to spatial attention but also the inference of mental states. In accordance to spatial attention shifting, our results indeed indicated that rTPJ cTBS specifically impaired performance in those trials where a maximal shift of attention to another's mental state was needed (false belief trials). One might argue that a “low‐level” attention shifting function generally guides the ability to switch between representations of the self and others irrespective of whether these representations involve taking another person's perspective or mental state [Costa et al., 2008], evaluating morality [Yoder and Decety, 2014; Young et al., 2010a], control of imitation [Sowden and Catmur, 2015], self‐other distinctions [Heinisch et al., 2012], attribution of awareness to oneself and others [Kelly et al., 2014], estimation of another's bodily size [Cazzato et al., 2015], or false belief as investigated in this cTBS study. Overall, the detection of unexpected targets or the recognition of another person's state of mind (regardless of the exact representation) might rely on a common “low‐level” attention shifting function as fast processing is highly important for survival [Gruber et al., 2010] both in the context of spatial attention and social interaction. To this end, we here observed a significant correlation between the effects of stimulation on both tasks. This positive correlation reflects the fact that participants performing worse in invalid trials (higher IES) after experimental stimulation also made more errors in the false belief trials after anterior cTBS (and vice versa). Hence, our results indicate a common underlying neural mechanism and strongly support the idea of a common attention shifting function of rTPJ involved in both types of tasks.

Limitations

Given the limited spatial precision of cTBS, we cannot rule out that the anterior rTPJ stimulation may at least in part have affected posterior rTPJ. In our previous ALE‐meta analysis, the posterior rTPJ was identified to show higher convergence for false belief tasks in contrast to reorienting of spatial attention tasks [Krall et al., 2015]. Thus a partial spill‐over of the stimulation (or a transmission of the effect via anatomical connections) might have additionally influenced performance in the false belief task through posterior rTPJ activation. Note, however, that the spatial spread of direct TMS stimulation is approximately 3 to 4 mm [spatial resolution of 10–15 mm2; Valero‐Cabre et al., 2005, 2007]. Furthermore, evidence from animal and modeling studies suggests that the neuromodulatory effects of TMS are maximal in the targeted region [Valero‐Cabre et al., 2005]. In our ALE meta‐analyses the two peak activation convergences for reorienting of attention (anterior rTPJ) and false‐belief processing (posterior rTPJ) were located 16.64 mm apart from each other. Therefore, we consider direct effects on posterior rTPJ as minor [Krall et al., 2015; see also Fig. 1 for individual stimulation points]. However, indirect effects on regions associated with the ventral and dorsal attention network and the social network were certainly expected as it has been shown that TMS‐induced activity spreads to remote regions which are strongly connected to the targeted region [Valero‐Cabre et al., 2005]. Further, the effect of stimulation in invalid trials and false belief trials correlated significantly, indicating a common nature of this effect, which renders a prominent impact of a possibly ‘co‐stimulated’ posterior rTPJ highly unlikely. Although we maximized the effect on the anterior rTPJ, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the observed effects on reorienting and false belief performance are influenced by two distinct neural networks. Such distinct neural networks may even both be located within the anterior rTPJ thus rendering a selective stimulation of either network technically impossible given the spatial resolution of TMS. The combination of multivariate pattern analyses and TMS might be another interesting option for the future to unravel these network‐specific effects within the anterior rTPJ. Hereby, one might be able to identify intermingled neural populations within the anterior rTPJ that subserve distinct functions but are similarly affected by TMS.

Recently, several groups reported that cTBS might not result in an inhibition of cortical excitability in all subjects [Hamada et al., 2013; Hinder et al., 2014]. Indeed, some of our participants did not feature altered task performance following cTBS applied to the rTPJ (see Fig. 3C). Although our data may thus involve non‐responders of cTBS, we nevertheless found significant behavioral influences on the performance in reorienting of spatial attention and false belief tasks corroborating the significance of our findings. If stimulation had caused inhibition in all participants, we would have possibly unraveled even stronger effects of the anterior rTPJ stimulation on task performance.

CONCLUSION

In sum, the effects of cTBS specifically found in invalid trials and false belief trials might be explained by an stimulation‐induced absence of the breach of expectation, consequently leading to a missing conceptual update of learned expectations and a general miss in attentional shifting [Corbetta et al., 2008, Geng and Vossel, 2013]. Furthermore, the significant correlation between the stimulation‐effects across both trials supports the assumption of a common underlying cognitive mechanism of the rTPJ. Future studies should investigate the exact functioning within the rTPJ (i.e., drawing upon aspects of timing) associated with reorienting of spatial attention and false belief tasks. Additionally, it would also be interesting to know whether other attention and social interaction tasks may also rely on the same neural mechanisms as reorienting of spatial attention and false belief tasks or whether these are more dependent on e.g. posterior rTPJ activation, and thus distinct cognitive processes. Investigating these hypotheses and theories will eventually enable a broader perspective on a more domain‐specific or domain‐general role of the rTPJ in attention and social interaction tasks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Helen L. Gallagher (School of Health and Life Sciences, Glasgow Caledonian University, Scotland) and Dr. Simone Vossel (Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine (INM‐3), Jülich Research Center, Germany) for their provision of task stimuli. Special thanks go to Dr. Mario Ortega (Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine) for technical support.

REFERENCES

- Arrington CM, Carr TH, Mayer AR, Rao SM (2000): Neural mechanisms of visual attention: Object‐based selection of a region in space. J Cognit Neurosci 12:106–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E (2001): The autism‐spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high‐functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord 31:5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, Kluge C, Bach D, Bradbury D, Heinze HJ, Dolan RJ, Driver J (2012): Cholinergic enhancement of visual attention and neural oscillations in the human brain. Curr Biol 22:397–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestmann S, Baudewig J, Siebner HR, Rothwell JC, Frahm J (2005): BOLD MRI responses to repetitive TMS over human dorsal premotor cortex. Neuroimage 28:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanke O, Mohr C, Michel CM, Pascual‐Leone A, Brugger P, Seeck M, Landis T, Thut G (2005): Linking out‐of‐body experience and self processing to mental own‐body imagery at the temporoparietal junction. J Neurosci 25:550–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledowski C, Prvulovic D, Goebel R, Zanella FE, Linden DE (2004): Attentional systems in target and distractor processing: A combined ERP and fMRI study. Neuroimage 22:530–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdok D, Langner R, Schilbach L, Jakobs O, Roski C, Caspers S, Laird AR, Fox PT, Zilles K, Eickhoff SB (2013): Characterization of the temporo‐parietal junction by combining data‐driven parcellation, complementary connectivity analyses, and functional decoding. Neuroimage 81:381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S, Geyer S, Schleicher A, Mohlberg H, Amunts K, Zilles K (2006): The human inferior parietal cortex: Cytoarchitectonic parcellation and interindividual variability. Neuroimage 33:430–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzato V, Mian E, Serino A, Mele S, Urgesi C (2015): Distinct contributions of extrastriate body area and temporoparietal junction in perceiving one's own and others' body. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 15:211–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers CD, Payne JM, Stokes MG, Mattingley JB (2004): Fast and slow parietal pathways mediate spatial attention. Nat Neurosci 7:217–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CF, Hsu TY, Tseng P, Liang WK, Tzeng OJ, Hung DL, Juan CH (2013): Right temporoparietal junction and attentional reorienting. Hum Brain Map 34:869–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chistyakov AV, Rubicsek O, Kaplan B, Zaaroor M, Klein E (2010): Safety, tolerability and preliminary evidence for antidepressant efficacy of theta‐burst transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with major depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 13:387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Kincade MJ, Lewis C, Snyder AZ, Sapir A (2005): Neural basis and recovery of spatial attention deficits in spatial neglect. Nat Neurosci 8:1603–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Kincade JM, Ollinger JM, Mcavoy MP, Shulman GL (2000): Nat Neurosci 3:292–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Patel G, Shulman GL (2008): The reorienting system of the human brain: From environment to theory of mind. Neuron 58:306–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Shulman GL (2002): Control of goal‐directed and stimulus‐driven attention in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 3:201–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Torriero S, Oliveri M, Caltagirone C (2008): Prefrontal and temporo‐parietal involvement in taking others' perspective: TMS evidence. Behav Neurol 19:71–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan E, Cohen LG (2011): Neuroplasticity subserving motor skill learning. Neuron 72:443–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Lamm C (2007): The role of the right temporoparietal junction in social interaction: How low‐level computational processes contribute to meta‐cognition. Neuroscientist 13:580–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diquattro NE, Sawaki R, Geng JJ (2013): Effective connectivity during feature‐based attentional capture: Evidence against the attentional reorienting hypothesis of TPJ. Cereb Cortex 24:3131–3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PC, Happe F, Frith U, Baker SC, Dolan RJ, Frackowiak RS, Frith CD (1995): Other minds in the brain: A functional imaging study of “theory of mind” in story comprehension. Cognition 57:109–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HL, Happe F, Brunswick N, Fletcher PC, Frith U, Frith CD (2000): Reading the mind in cartoons and stories: An fMRI study of 'theory of mind' in verbal and nonverbal tasks. Neuropsychologia 38:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng JJ, Vossel S (2013): Re‐evaluating the role of TPJ in attentional control: Contextual updating? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37:2608–2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giessing C, Thiel CM, Stephan KE, Rosler F, Fink GR (2004): Visuospatial attention: How to measure effects of infrequent, unattended events in a blocked stimulus design. Neuroimage 23:1370–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillebert CR, Mantini D, Thijs V, Sunaert S, Dupont P, Vandenberghe R (2011): Lesion evidence for the critical role of the intraparietal sulcus in spatial attention. Brain 134:1694–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene CM, Soto D (2014): Functional connectivity between ventral and dorsal frontoparietal networks underlies stimulus‐driven and working memory‐driven sources of visual distraction. Neuroimage 84:290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber O, Diekhof EK, Kirchenbauer L, Goschke T (2010): A neural system for evaluating the behavioural relevance of salient events outside the current focus of attention. Brain Res 1351:212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M, Murase N, Hasan A, Balaratnam M, Rothwell JC, (2013): The role of interneuron networks in driving human motor cortical plasticity. Cereb Cortex 23:1593–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinisch C, Kruger MC, Brune M (2012): Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over the temporoparietal junction influences distinction of self from famous but not unfamiliar others. Behav Neurosci 126:792–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig U, Cardenas‐Morales L, Connemann BJ, Kammer T, Schonfeldt‐Lecuona C (2010): Sham or real–post hoc estimation of stimulation condition in a randomized transcranial magnetic stimulation trial. Neurosci Lett 471:30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinder MR, Goss EL, Fujiyama H, Canty AJ, Garry MI, Rodger J, Summers JJ (2014): Inter‐ and intra‐individual variability following intermittent theta burst stimulation: implications for rehabilitation and recovery. Brain Stimul 7:365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrabetova S, Sacktor TC (1997): Long‐term potentiation and long‐term depression are induced through pharmacologically distinct NMDA receptors. Neurosci Lett 226:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC (2005): Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 45:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobs O, Wang LE, Dafotakis M, Grefkes C, Zilles K, Eickhoff SB (2009): Effects of timing and movement uncertainty implicate the temporo‐parietal junction in the prediction of forthcoming motor actions. Neuroimage 47:667–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly YT, Webb TW, Meier JD, Arcaro MJ, Graziano MS (2014): Attributing awareness to oneself and to others. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:5012–5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krall SC, Rottschy C, Oberwelland E, Bzdok D, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB, Fink GR, Konrad K (2015): The role of the right temporoparietal junction in attention and social interaction as revealed by ALE meta‐analysis. Brain Struct Funct 220:587–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansson A, Sigurjonsdottir O, Driver J (2010): Fortune and reversals of fortune in visual search: Reward contingencies for pop‐out targets affect search efficiency and target repetition effects. Atten Percept Psychophys 72:1229–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucyi A, Hodaie M, Davis KD (2012): Lateralization in intrinsic functional connectivity of the temporoparietal junction with salience‐ and attention‐related brain networks. J Neurophysiol 108:3382–3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange‐Malecki B, Treue S (2012): A flanker effect for moving visual stimuli. Vis Res 62:134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh R, Oishi K, Hsu J, Lindquist M, Gottesman RF, Jarso S, Crainiceanu C, Mori S, Hillis AE (2013): Acute lesions that impair affective empathy. Brain 136:2539–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso E, Frith CD, Driver J (2002): Supramodal effects of covert spatial orienting triggered by visual or tactile events. J Cogn Neurosci 14:389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars RB, Sallet J, Schuffelgen U, Jbabdi S, Toni I, Rushworth MF (2012): Connectivity‐based subdivisions of the human right “temporoparietal junction area”: Evidence for different areas participating in different cortical networks. Cereb Cortex 22:1894–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer AR, Dorflinger JM, Rao SM, Seidenberg M (2004): Neural networks underlying endogenous and exogenous visual‐spatial orienting. Neuroimage 23:534–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcallister SM, Rothwell JC, Ridding MC (2009): Selective modulation of intracortical inhibition by low‐intensity theta burst stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 120:820–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JP (2008): Activity in right temporo‐parietal junction is not selective for theory‐of‐mind. Cereb Cortex 18:262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mort DJ, Malhotra P, Mannan SK, Rorden C, Pambakian A, Kennard C, Husain M (2003): The anatomy of visual neglect. Brain 126:1986–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy FC, Klein RM (1998): The effects of nicotine on spatial and non‐spatial expectancies in a covert orienting task. Neuropsychologia 36:1103–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettekoven Volz LJ, Kutscha M, Pool EM, Rehme AK, Eickhoff SB, Fink GR Grefkes C (2014): Dose‐dependent effects of theta burst rTMS on cortical excitability and resting‐state connectivity of the human motor system. J Neurosci 34:6849–6859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Petersen SE (1990): The attention system of the human brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 13:25–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Snyder CR, Davidson BJ (1980): Attention and the detection of signals. J Exp Psychol 109:160–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado J, Clavagnier S, Otzenberger H, Scheiber C, Kennedy H, Perenin MT (2005): Two cortical systems for reaching in central and peripheral vision. Neuron 48:849–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosler M, Retz W, Retz‐Junginger P, Stieglitz RD, Kessler H, Reimherr F, Wender PH (2008): Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Benchmarking diagnosis using the Wender‐Reimherr adult rating scale. Nervenarzt 79:320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothmayr C, Sodian B, Hajak G, Dohnel K, Meinhardt J, Sommer M (2011): Common and distinct neural networks for false‐belief reasoning and inhibitory control. Neuroimage 56:1705–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Powell LJ (2006): It's the thought that counts: specific brain regions for one component of theory of mind. Psychol Sci 17:692–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay‐Tsoory SG, Tomer R, Berger BD, Aharon‐Peretz J (2003): Characterization of empathy deficits following prefrontal brain damage: The role of the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 15:324–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowden S, Catmur C (2015): The role of the right temporoparietal junction in the control of imitation. Cereb Cortex 25:1107–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence C, Mcglone FP, Kettenmann B, Kobal G (2001): Attention to olfaction. A psychophysical investigation. Exp Brain Res 138:432–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LM, Walsh V, Rothwell JC (2001): Motor and phosphene thresholds magnetic stimulation correlation study. Neuropsycholgia 39:415–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel C, Alexis DM, Clayton NS, Davis G (2010): Mental‐state attribution drives rapid, reflexive gaze following. Atten Percept Psychophys 72:695–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend JT, Ashby FG (1983): The Stochastic Modelling of Elementary Psychological Processes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valero‐Cabre A, Payne BR, Rushmore J, Lomber SG, Pascual‐Leone A (2005): Impact of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the parietal cortex on metabolic brain activity: A 14C‐2DG tracing study in the cat. Exp Brain Res 163:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero‐Cabre A, Payne BR, Pascual‐Leone A (2007): Opposite impact on 14C‐2‐deoxyglucose brain metabolism following patterns of high and low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the posterior parietal cortex. Exp Brain Res 176:603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Meer L, Groenewold NA, Nolen WA, Pijnenborg M, Aleman A (2011): Inhibit yourself and understand the other: Neural basis of distinct processes underlying theory of mind. Neuroimage 56:2364–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Overwalle F (2009): Social cognition and the brain: A meta‐analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 30:829–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogeley K, Bussfeld P, Newen A, Herrmann S, Happe F, Falkai P, Maier W, Shah NJ, Fink GR, Zilles K (2001): Mind reading: Neural mechanisms of theory of mind and self‐perspective. Neuroimage 14:170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossel S, Geng JJ, Fink GR (2014): Dorsal and ventral attention systems: Distinct neural circuits but collaborative roles. Neuroscientist 20:150–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossel S, Thiel CM, Fink GR (2006): Cue validity modulates the neural correlates of covert endogenous orienting of attention in parietal and frontal cortex. Neuroimage 32:1257–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossel S, Thiel CM, Fink GR (2008a): Behavioral and neural effects of nicotine on visuospatial attentional reorienting in non‐smoking subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossel S, Weidner R, Thiel CM, Fink GR (2008b): What is “odd” in Posner's location‐cuing paradigm? Neural responses to unexpected location and feature changes compared. J Neurosci 21:30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossel S, Weidner R, Driver J, Friston KJ, Fink GR (2012): Deconstructing the architecture of dorsal and ventral attention systems with dynamic causal modeling. J Neurosci 32:10637–10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykowska A, Wiese E, Prosser A, Muller HJ (2014): Beliefs about the minds of others influence how we process sensory information. PLoS One 9:e94339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KJ, Decety J (2014): The Good, the bad, and the just: Justice sensitivity predicts neural response during moral evaluation of actions performed by others. J Neurosci 34:4161–4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Camprodon JA, Hauser M, Pascual‐Leone A, Saxe R (2010a): Disruption of the right temporoparietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:6753–6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Dodell‐Feder D, Saxe R (2010b): What gets the attention of the temporo‐parietal junction? An fMRI investigation of attention and theory of mind. Neuropsychologia 48:2658–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]