Abstract

Functional brain imaging studies reported activation of the left dorsal premotor cortex (PMd), that is, a main area in the writing network, in reading tasks. However, it remains unclear whether this area is causally relevant for written stimulus recognition or its activation simply results from a passive coactivation of reading and writing networks. Here, we used chronometric paired‐pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to address this issue by disrupting the activity of the PMd, the so‐called Exner's area, while participants performed a lexical decision task. Both words and pseudowords were presented in printed and handwritten characters. The latter was assumed to be closely associated with motor representations of handwriting gestures. We found that TMS over the PMd in relatively early time‐windows, i.e., between 60 and 160 ms after the stimulus onset, increased reaction times to pseudoword without affecting word recognition. Interestingly, this result pattern was found for both printed and handwritten characters, that is, regardless of whether the characters evoked motor representations of writing actions. Our result showed that under some circumstances the activation of the PMd does not simply result from passive association between reading and writing networks but has a functional role in the reading process. At least, at an early stage of written stimuli recognition, this role seems to depend on a common sublexical and serial process underlying writing and pseudoword reading rather than on an implicit evocation of writing actions during reading as typically assumed. Hum Brain Mapp 37:1531‐1543, 2016. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: transcranial magnetic stimulation, Exner's area, sublexical process, cortico‐spinal excitability, functional role

INTRODUCTION

Reading and writing are closely related. In terms of cognitive processes, writing could be considered as a reverse process of reading. While reading consists in extracting meaning and/or phonological information contained in a written code, writing transforms both kinds of information into sequences of characters. At the motor level, children learn to reproduce the form of written characters that they read, which allows them to create a motor memory of hand gesture associated with each character [Van Galen, 1991]. Behavioral data showed that such association is beneficial as it facilitates written word and letter recognition [Longcamp et al., 2005b].

A close link between reading and writing leads to an increase of functional connections between the brain areas within the visual and motor systems. Brain imaging studies reported not only activity within the visual system during writing [Beeson et al., 2003; Nakamura et al., 2002] but also activity within the writing network during reading [Dehaene et al., 2010; Monzalvo et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2012; Rapp and Lipka, 2011; Xu et al., 2005]. This latter result raises theoretical issues on the functional role of writing related‐knowledge in the reading process.

One of the areas within the writing network that has frequently been reported to be activated during reading is the left premotor cortex located within BA6. More commonly known as the “Exner's area” [Exner, 1881], it is considered as one of the main writing centers since it is consistently activated when writing is compared to other linguistic or peripheral sensori‐motor processes and its lesions lead to writing‐specific disorders [Anderson et al., 1990; Katanoda et al., 2001; Planton et al., 2013]. Although the involvement of this area in writing is well established, its functional role is still subject to debate. Traditionally, the area has been associated with the generation of motor commands in handwriting [Exner, 1881; Roux et al., 2009]. This view is nevertheless questioned by the observations that it was also activated during keyboard typing or mental writing, that is, when actual handwriting gestures were not required [Harrington et al., 2007; Purcell et al., 2011]. These findings have led to an alternative interpretation that the area may play a more central role in language processing.

More related to our purpose is the fact that the left premotor cortex, particularly in the dorsal portion (PMd), is also activated during reading [Dehaene et al., 2010; Monzalvo et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2005]. Yet, correlational data obtained in fMRI studies do not provide information regarding its functional role in the reading process. On the one hand, strong association between reading and writing established during literacy acquisition might lead to an automatic and passive activation of the writing network during reading without functional significance. However, writing may actively contribute to fluent reading. Here, we investigated this issue using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to disrupt the function of the PMd during an early stage of written word and pseudoword recognition. Two possible functional roles of this area were examined by manipulating the characteristics of written stimuli presented in a lexical decision task. First, in order to examine whether the contribution of the PMd to reading is due to implicit evocation of writing motor processes, we compared the TMS effects on stimuli written in printed and in handwritten character. If the contribution of the PMd to reading is mediated by the motoric representations associated with the written input as typically assumed [Anderson et al., 1990; Longcamp et al., 2005a; Nakamura et al., 2012], the disruptive effect of TMS should be restricted to (or stronger for) the stimuli presented in handwritten character since they are more closely associated with motor memories for hand gestures [Longcamp et al., 2011, 2006]. Alternatively, it is also possible that the contribution of this area to reading is due to shared cognitive components between these two activities. To test this assumption, we compared the performance on word and pseudoword reading. While reading words is typically performed through a global and parallel mechanism, the cognitive processes supporting pseudoword reading are more similar to those involved in writing since both rely on a serial, sublexical, mechanism [Coltheart et al., 2001]. Thus, if the involvement of the PMd in writing and reading is due to shared cognitive processes of these two activities, TMS effect should be stronger during pseudoword than word reading.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Fifteen monolingual French speakers participated in the study (11 females, 20–36 yrs, mean = 25). All participants were right‐handed and none reported any history of language or neurological disorders. The experiments were approved by the local ethics committee (Sud Méditerranée I). Participants were paid for their participation.

Structural MRI and TMS

A frameless stereotaxic system was used to position the TMS coil on the scalp in order to stimulate a precise anatomical region‐of‐interest. All volunteers participated in a separate MRI session where a high‐resolution anatomical scan was acquired (FOV 256 × 256 × 180 mm3, voxel size 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, TR 9.4 ms, TE 4.424 ms, α = 30°: 3T BRUKER MEDSPEC 30/80 AVANCE scanner running ParaVision 3.0.2). During the TMS session, a Polaris Spectra infrared camera (Northern Digital, Canada) tracked the participant's head and registered it to his/her MRI scan. The neuronavigation was used to both target and record stimulation sites (Navigation Brain System, Nexstim 2.3, Helsinki, Finland). Stimulation was performed using a Magstim 200 stimulator TMS system (Magstim, Whitland, UK) and a coplanar figure‐of‐eight coil with external loop diameter of 9 cm. The stimulation intensity was individually determined based on the threshold necessary to observe a visible right hand twitch when stimulating the hand area of the primary motor cortex in the left hemisphere (M1, Fig. 1). This area was identified anatomically according to the method of Yousry et al. [1997]. The initial stimulation intensity applied to M1 was adjusted to the depth of the PMd to equalize the induced electric field value within M1 at participant's active motor threshold and the PMd [see Spieser et al., 2013 for the equalization procedure]. The final intensity ranged from 30 to 55% of the maximum stimulator output (mean = 41%). During the lexical decision and control (image judgment) tasks, paired‐pulse stimulations were delivered in three time‐windows: at the stimulus onset and 40 ms poststimulus onset (0/40 ms), 60 and 100 post‐stimulus onset (60/100 ms) or 120 and 160 ms poststimulus onset (120/160 ms). The TMS delivered in the 0/40 time‐window acted as baseline. Existing EEG and MEG studies suggest that it is unlikely that high‐level processes, including, phonological, orthographic, semantic or writing‐related ones, could already take place in such an early time window [Cornelissen et al., 2009; Mainy et al., 2008; Pammer et al., 2004]. Additionally, a pair‐pulse stimulation applied at 0 and 40 ms from the stimulus onset was previously used as baseline in Duncan et al. [2010] study where TMS was applied on the occipito‐temporal cortex during a lexical decision task. The performance obtained in this condition and the one obtained during vertex stimulation were identical, which suggests that the stimulation applied in the 0/40 ms time window provides a valid baseline condition. We chose paired‐pulse TMS because of the summation properties of TMS pulses that offers longer perturbation period than single‐pulse TMS but still allows good temporal resolution defined by the temporal distance between the two pulses [Silvanto et al., 2005; Walsh et al., 2003]. Stimulation parameters were well within international safety guidelines [Rossi et al., 2009; Wassermann, 1998].

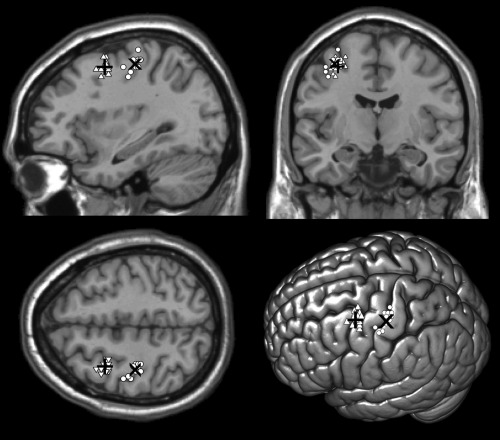

Figure 1.

Individual participants’ stimulation sites of the PMd (white triangles) and M1 (white circles) normalized in the MNI space and projected on a standard template. “+” and “×” showed the average MNI coordinates of PMd (−32 2 52) and M1 (−35 −22 55), respectively.

Localization of the Target Area

The target area was anatomically identified based on the MRI of each participant. We localized a specific site within BA6, at the rostral part of the dorsal premotor cortex. This corresponded to the posterior portion of the left middle frontal gyrus at the junction between the precentral sulcus and the superior frontal sulcus [Ahdab et al., 2013]. Studies on writing reported activation of this area when writing was compared to other language and motor‐related tasks [see Planton et al., 2013 for a review on this topic]. This area must be distinguished from the ventral part of the premotor cortex, which is anatomically and functionally closer to the Broca's area. Unlike the PMd, the activation of ventral premotor cortex is not writing‐specific and is more related to articulatory planning and phonological components of speech [Planton et al., 2013; Price, 2010; Vigneau et al., 2006].

Figure 1 illustrated the localization of the target area and M1 in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates. The MNI coordinates of these areas were obtained by normalizing participants’ T1 images to T1‐weighted images (MNI152) using the coregistration toolbox FLIRT provided with FSL (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FSL). The transformation matrix obtained by this procedure was applied to the target coordinates (in MRI coordinates system, from Navigation Brain System) to be converted into MNI space.

Lexical Decision Task

The stimuli presented in the lexical decision task consisted of 180 words and 180 pseudowords. Each word was used to generate a pseudoword having the same numbers of letters, phonemes, and syllables and closely matched for bigram frequency (http://www.lexique.org). All pseudowords were pronounceable. Each type of stimuli was equally separated into six subsets of 30 stimuli. Across the six subsets, words were matched for objective written and spoken frequencies, number of phonological and orthographic neighbors, number of phonemes, number of letters, number of syllables and phonological and orthographic uniqueness points [New et al., 2004] (ps > 0.25, see Table AI). Pseudowords were matched for number of letters, number of phonemes, number of syllables and bigram frequency (ps > 0.25). Within each participant, the stimuli from a subset were presented in either printed or handwritten character and were associated with one of the three stimulation time‐windows described above. The six subsets of words and of pseudowords were used to represent six experimental conditions (two types of character × three time‐windows). Thus, no stimulus was presented more than once within each participant. Across participants, each stimulus was equally presented in both printed and handwritten characters and was associated with the three stimulation time‐windows. Roman and Script fonts provided by E‐prime software were used as “printed” and “handwritten” characters, respectively.

To reduce the possibility that participants feel the different stimulation timings during the task, within a block of trials, the stimuli associated with different stimulation timings were pseudorandomly presented such that the same stimulation timing (e.g., 60/100 ms) was delivered in three consecutive trials whereas in the next three trials it either remained constant or was changed up (e.g., 120/160 ms) or down (e.g., 0/40 ms) by one window. This stimulation protocol was successfully used in previous chronometric TMS studies to dissociate the TMS effect in different time‐windows [Duncan et al., 2010; Pattamadilok et al., 2015; Sliwinska et al., 2012).

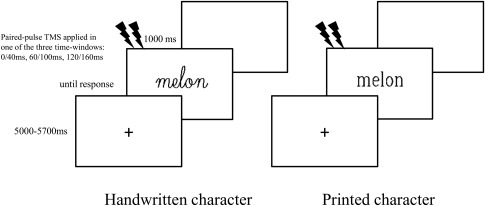

During the session, stimuli written in printed and handwritten character were presented in two separated blocks. Within each block, words and pseudowords were presented in a random order. The presentation order of the printed and handwritten blocks was counterbalanced across participants. A trial consisted of the following sequence of events: a fixation cross with the presentation duration varied between 5000 and 5700 ms. It was followed by a stimulus that remained on the screen until a response was given. After the response, the screen remained blank for 1000 ms (Fig. 2). This timeline guaranteed a total duration of at least 6000 ms between two paired‐pulse stimulations, which allowed us to avoid any carry‐over effect of TMS from one trial to another. Participants were instructed to indicate as early as possible whether the stimulus was a real French word or a pseudoword by pressing a button using either their left index or middle finger. By asking the participants to respond with their left hand, we avoided possible interferences of the stimulation with the movement of the right hand. The association between response and finger was counterbalanced across participants. Accuracy and reaction times (RTs) were recorded. Presentation, timing, and data collection were controlled by E‐prime 1.2 software. The session started with a practice block that allowed the participants to familiarize with the procedure and the task. Feedback was provided only during the practice trials.

Figure 2.

An illustration of the timeline of a trial in the lexical decision task. Trials began with a fixation cross, followed by a stimulus and a blank screen. The duration (in ms) of each segment is written next to the screen. In trials that included TMS, a paired‐pulse TMS was applied in one of the three time‐windows.

Control Task

To ascertain that the TMS effects observed in the lexical decision task did not result from non‐specific artifacts, image judgment was included in the protocol as a control task. Participants had to judge whether the picture presented on the screen represented a natural or manmade object. Given that neither the task nor the stimuli evoked writing, drawing or any activity related to hand movement, no TMS effect was expected.

The stimuli consisted of 45 black and white pictures of manmade objects and 45 of natural objects. Each type of object was equally separated into three subsets, corresponding to the three stimulation timings described above. The association between image and stimulation timing was counterbalanced across participants. All manmade and natural objects were presented in a random order within a single block. The presentation timeline and the response mode were identical to the lexical decision task.

RESULTS

Lexical Decision Task

Preliminary inspection of the RTs obtained in the lexical decision task led us to discard from further analyses deviant RTs, that is, those longer or shorter than the mean RT observed on correct trials plus or minus 2.5 SD (2.4% of the data). Three‐way repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted by subjects with lexicality (words vs. pseudowords), character (printed vs. handwritten) and TMS (baseline, 60/100 ms, 120/160 ms) as within‐subject factors. RT and accuracy were the two dependent measures.

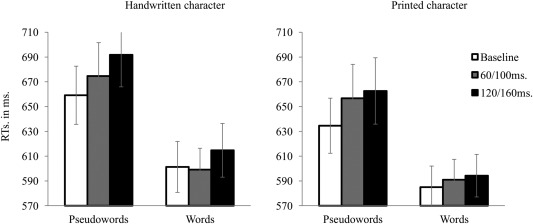

The RT data showed significant main effects of lexicality [F(1,14) = 17.6, P = 0.0009], character [F(1,14) = 5.9, P = 0.03], TMS [F(2,28) = 7.1, P = 0.003] and a significant interaction between Lexicality and TMS [F(2,28) = 3.4, P = 0.04]. No other interaction showed a significant effect (all Fs ≤ 1). Further analyses investigating the effect of TMS separately on words and pseudowords showed that only pseudoword [F(2,28) = 10.3, P = 0.0004] but not word recognition [F(2,28) = 1.6, P = 0.23] was affected by the stimulation. As illustrated in Figure 3, longer RTs on pseudowords were obtained when the stimulation was applied in both 60/100 ms (676 ms, P = 0.01 using Bonferroni correction) and 120/160 ms time‐windows (681 ms, P = 0.002 using Bonferroni correction) compared with baseline (650 ms).1

Figure 3.

The RTs obtained for handwritten pseudowords, handwritten words, printed pseudowords and printed words in the lexical decision task. White, gray, and black bars indicate the trials in which TMS was applied in the 0/40 ms (baseline), 60/100 ms, and 120/160 ms time‐window, respectively. The vertical bars represent standard errors.

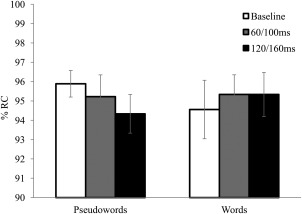

The same analyses performed on the accuracy scores (Fig. 4) showed that only the effect of character almost reached significance [F(1,14) = 4, P = 0.07], with printed character (95.8%) leading to a higher score than handwritten characters (94.4%). No other main effect or interaction significantly affected performance (all Fs < 1 except lexicality × TMS: F(2,28) = 1.4, P = 0.26] and lexicality × character × TMS: F(2,28) = 1.7, P = 0.19].

Figure 4.

The percentages of correct responses (%RC) obtained for words and pseudowords in the lexical decision task. White, gray, and black bars indicate the trials in which TMS was applied in the 0/40 ms (baseline), 60/100 ms, and 120/160 ms time‐window, respectively. The vertical bars represent standard errors.

Control Task

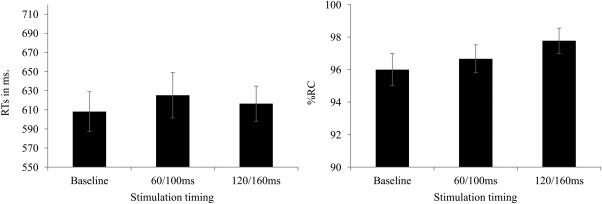

Preliminary inspection of the RTs obtained in the image judgment task led us to discard from further analyses deviant RTs, that is, those longer or shorter than the mean RT observed on correct trials plus or minus 2.5 SD (2.5% of the data). One‐way repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted by subjects with TMS (baseline, 60/100 ms, 120/160 ms) as a within‐subject factor. The data on both categories of object were collapsed. RT and accuracy were the two dependent measures (Fig. 5). As expected, neither the RT nor the accuracy showed a significant effect of TMS [F(2,28) = 1.9, P = 0.16 and F(2,28) = 1, P = 0.38 for the RT and the accuracy, respectively]. This result further suggests that the TMS effect obtained in the lexical decision task was specific to both type of stimulus (pseudowords) and task and thus did not result from general artifacts of TMS.2

Figure 5.

The RTs and percentages of correct responses (%RC) obtained in the control task when TMS was applied in the 0/40 ms (baseline), 60/100 ms, and 120/160 ms time windows. The vertical bars represent standard errors.

Interim Discussion

Chronometric paired‐pulse TMS was used to investigate the functional role of the PMd in a lexical decision task. In addition to the classic effect of lexicality, we found a significant effect of character with handwritten character leading to lower performance than printed character. This could be due to the fact that the handwritten character that we used here was not subject's own handwriting and might be less familiar to them than the character used in the printed condition. Additionally, some subjects reported that some letters in the handwritten condition (e.g., “p” and “q”) were difficult to distinguish. However, this significant effect of character did not interact with TMS. The most important result is a significant interaction between TMS and lexicality: TMS over the PMd in both stimulation time‐windows slowed down pseudoword but not word recognition. Neither this interaction nor the main effect of TMS was modulated by type of character. This result is in favor of a functional role of the PMd in early reading process and suggests that its contribution might be due to shared cognitive processes in writing and reading rather than an implicit evocation of writing motor processes during reading.

Nevertheless, before discarding the idea that the contribution of the premotor cortex to reading is mediated by the motor representations associated with the written input, one must consider an alternative explanation for the absence of TMS effect specifically on the stimuli presented in handwritten character. It was possible that the handwritten character used here failed to elicit motor representations because it did not correspond to participants’ own handwriting. Alternatively, it might also be the case that both printed and handwritten characters activated motor representations to the same extent. To verify these hypotheses, we ran an additional experiment to examine whether reading this kind of handwritten character, but not the printed one, could induce changes in cortico‐spinal excitability of hand muscles that are involved in writing gestures as we assumed. Activations of the neurons in the cortical motor system have been observed during the observation of objects in the absence of any movement, and thought to reflect internal representation of actions related to the objects [Grèzes et al., 2003; Rizzolatti and Luppino, 2001]. In this situation, the participants were exposed to handwritten characters, which are traces of writing gesture and could be translated into a potential motor action. Indeed, Nakatsuka et al., (2012) showed that viewing handwritten characters was sufficient to modify the excitability of the primary motor cortex (M1). A similar result was reported in Papathanasiou et al. [2004] study showing an increased of motor‐evoked potentials (MEPs) in first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscles of the dominant hand during visual searching/matching tasks, particularly when targets were letters or geometric shapes. Longcamp et al. [2011, 2006] also reported a stronger activation of M1 during observing handwritten compared with printed character.

ADDITIONAL EXPERIMENT

An independent group of participants was required to perform a lexical decision task as in the previous experiment. Once again, the same printed and handwritten characters were used. Here, chronometric TMS provided a tool to probe a modulation of cortico‐spinal excitability of digit muscles during reading. Therefore, only single‐pulse stimulation, which allows us to minimize artifacts on electric muscle responses, was applied. If the handwritten character used here was able to elicit the motor representations of writing gestures as we assumed, this type of character but not the printed one should induce changes in MEPs in digit muscles as previously reported in the literature [Nakatsuka et al., 2012].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Thirteen monolingual French speakers participated in the study (7 females, 18–30 y old, mean = 24). All participants were right‐handed and none reported any history of language or neurological disorders. The experiments were approved by the local ethics committee (Sud Méditerranée I). Participants were paid for their participation.

Structural MRI and TMS

As in the above experiment, individual MRI scans were used to localize the site of stimulation, that is, an area within primary motor cortex of the left hemisphere that controls the FDI muscles of the right hand [Bonnard et al., 2007]. The FDI muscles were chosen because they are strongly involved in writing gestures. The resting motor threshold of the FDI muscles was individually determined based on the minimal intensity capable of evoking MEPs in 5 out of 10 consecutive trials with amplitude of at least 50 µV. The final stimulation intensity was adjusted to 110% of the resting motor threshold. The values ranged from 44 to 71% of the maximum stimulator output (mean = 52%). The stimulation protocol applied during the lexical decision task was similar to the previous experiment. However, given that in this experiment we were interested in TMS‐induced changes in cortico‐spinal excitability rather than in TMS disruptive effect on task performance, the paired‐pulse stimulations were replaced by single‐pulse stimulations, which were delivered at three time‐points (at the stimulus onset, 60 and 120 ms poststimulus onset). This allowed us to follow the progression of the excitability of the FDI muscles during stimulus processing.

Electromyography (EMG)

During the lexical decision task, Ag ± AgCl surface electrodes were used to record MEPs from the right FDI with ground reference electrode placed on ulnar styloid. Participants were required to keep their right elbow flexed at 90° and their right hand half pronated in a totally relaxed position. On‐line visual monitoring of the EMG signal allowed us to verify the complete muscle relaxation before TMS. The remaining procedure was identical to the previous experiment, although the instruction did not stress response speed.

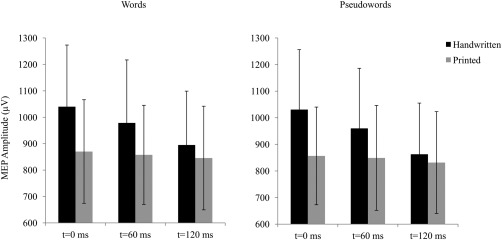

RESULTS

Peak‐to‐peak MEP amplitudes of FDI muscles were measured for each experimental condition. Error trials were discarded from further analyses (5.7%). Three‐way repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted by subjects with lexicality (words vs. pseudowords), character (printed vs. handwritten) and time‐points (0, 60, and 120 ms) as within‐subject factors. The analyses showed significant effects of time‐point [F(2,24) = 3.3, P = 0.05] and its interaction with character [F(2,24) = 3.6, P = 0.04]. No other main effect or interactions was significant (Fs > 1). Analyses performed separately on printed and handwritten stimuli showed that the MEP amplitudes remained stable across the different time‐points when participants processed printed character (F < 1). Importantly, it decreased significantly from t = 0 ms to t = 120 ms when they processed handwritten character [F(2,24) = 4.2, P = 0.03]. Direct comparisons of the MEP amplitudes observed in printed and handwritten character conditions at the different time‐points clearly showed that at the stimulus onset (0 ms), handwritten character induced higher MEP amplitude compared to printed character (P = 0.0007). As shown in Figure 6, the difference in MEP amplitude decreased but remained significant at 60 ms (P = 0.04) and disappeared at 120 ms (P > 0.95).

Figure 6.

Peak‐to‐peak MEP amplitudes of the FDI muscles measured when a single‐pulse TMS was applied on M1 at 0, 60, and 120 ms poststimulus onset, during the lexical decision task. Black and gray bars indicate responses to handwritten and printed characters, respectively. The vertical bars represent standard errors.

The finding clearly showed that although the handwritten character used here did not correspond to the participants’ own handwriting, they induced changes in cortico‐spinal excitability of the hand muscles that are involved in writing gestures while the hand remained completely relaxed, whereas printed character failed to do so. In our study where the two types of character were presented in separated blocks, the participants knew in advance which type of character would be presented. Preparing to process handwritten character seems to increase the excitability of the FDI as shown by an increased of MEP amplitude already at stimulus onset. However, this task‐irrelevant and automatic activity was rapidly suppressed within 120 ms, that is, the time‐point where MEP amplitudes obtained on printed and handwritten stimuli became statistically equivalent.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Previous fMRI studies showed activation of the PMd, i.e., a main region in the writing network, during reading (Dehaene, et al. 2010; Monzalvo, et al. 2012; Nakamura, et al. 2012; Xu, et al. 2005). Using TMS to explore its contribution to reading, we found that under some circumstances the activation of the PMd did not simply result from passive association between reading and writing networks but had a functional role in the reading process. Stimulation over this area in relatively early time‐windows, that is, between 60 and 160 ms poststimulus onset, increased RTs to pseudoword without affecting word recognition. Interestingly, this result pattern was found for both printed and handwritten characters, that is, regardless of whether or not the characters evoked motor representations of handwriting gesture.

The observation that stimulation over the PMd only affected pseudoword but not word recognition might seem puzzling given that brain imaging studies showed activation of this area during word recognition and passive viewing of letters [Longcamp et al., 2003; Monzalvo et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2012]. Based on the traditional view that the PMd plays a role in the planning of motor commands in handwriting, observing its activation in reading tasks has naturally led to the interpretation that reading involves the gesture decoding system assumed to be located within this area [Longcamp et al., 2003; Pegado et al., 2014]. According to Nakamura et al. [2012], this system supports the dynamic motor representations of writing actions that could facilitate visual perception of letters.

Our finding raises two issues related to the above assumption. First, although the PMd is truly activated during letter or visual word recognition, it might not necessarily have a functional role. The activation of this area could be explained by automatic coactivation of the neural networks that support reading and writing due to the associations formed by extensive learning to read and write during childhood. Second, when this area plays a functional role in reading, it seems to be unrelated to implicit evocation of the motor representations that correspond to handwriting gestures. Although reading can sometimes implicitly evoke writing motor processes as illustrated in our additional experiment (i.e., when the stimuli were presented in handwritten character) and the brain activity within the PMd could be stronger in the presence of handwritten compared with printed character [Nakamura et al., 2012], these motor‐related processes could not explain the functional role of this area, at least in the task and at the early stage of written stimulus recognition explored here.

The Contribution of the Dorsal Premotor Cortex to Pseudoword Reading

As mentioned in the Introduction, writing and pseudoword reading are both assumed to rely on sublexical and serial processes. However, before further elaborating this assumption, some alternative accounts must be considered. One explanation is that pseudoword reading relies more on subvocal articulation or phonological information than word reading. Although an involvement of the phonologic‐motor coordination network could not be ruled out based on the present finding, the precise localization of our target area does not support this interpretation. In fact, the rostral part of the PMd targeted here corresponds to the portion of the premotor cortex just anterior to the precentral gyrus and roughly adjacent to the hand area in the primary motor cortex: M1 in Figure 1 [Ahdab et al., 2013]. The latter is well above the articulator area for speech production. PMd is ∼38 mm to the inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis [BA 44, MNI coordinates: −44 14 18, as defined by Amunts et al., 2004], known to be involved in the overt/covert articulation and phonological processes in speech production [Amunts et al., 2004; Price, 2012]. Although their border is not known in human brain [de Graaf et al., 2009; Rizzolatti et al., 1998], the dorsal area seems to be functionally distinguished from the premotor area involved in speech production and preparation, that is, located more ventrally and closer to the Broca's area [Dogil et al., 2002; Dronkers, 1996; Wilson et al., 2004]. Longcamp et al. [2003] also found the dorsal area to be activated when their participants were writing the pseudoletters, which could not be transcoded phonologically. Thus, even though the subvocal articulation or phonological processes might also take place during writing and/or pseudoword reading, it seems unlikely that these processes occur in the PMd where the TMS was applied. Further studies that allow dissociation between the role of the ventral and dorsal premotor cortices in both reading and writing are needed to shed light in this issue.

Another plausible explanation relies on the fact that processing pseudowords is more difficult than processing words. This general increase in task difficulty and processing time might allow top‐down information from other sources to play a role. For instance, previous studies showed that the influence of orthographic or semantic information on spoken word recognition was amplified in the situations where speech intelligibility was compromised [Davis et al., 2005; Mattys et al., 2012; Obleser et al., 2007; Pattamadilok et al., 2011]. The contribution of high‐level or cross‐modal information is associated with an increase of activity in brain areas that are remote from the primary cortex where the input information is initially processed [Dehaene et al., 2010; Obleser et al., 2007; Yoncheva et al., 2010]. The same mechanism could explain the contribution of writing‐related knowledge as an additional source of information during pseudoword recognition. Although it seems unlikely that such top‐down influence occurs already in the earliest time‐window (60/100 ms) investigated here, it might somehow contribute to the effect observed in the later time‐window (120/160 ms) [Wheat et al., 2010; Woodhead et al., 2014].

To our view, a more parsimonious account is that writing related‐knowledge systematically contributes to early stages of written word and pseudoword recognition but its contribution would be particularly relevant for pseudowords, due to shared cognitive processes underlying writing and pseudoword reading. In the reading domain, monosyllable or disyllable words, as those used in this study, are generally recognized by the lexical or global mechanism. On the contrary, pseudoword reading is more likely to rely on the sublexical mechanism by which letters are processed serially (Coltheart, et al. 2001). Still, one may argue that making lexical decision is not totally similar to reading. Additionally, the mechanism underlying pseudoword decision is still subject to debate [e.g., Dufau et al., 2012; Grainger and Jacobs, 1996; Murray and Forster, 2004; Perea et al., 2005; Ratcliff et al., 2004; Wagenmakers et al., 2008, 2004; Yap et al., 2015]. For instance, while some studies showed that pseudoword decision depended on factors like number of letters which suggests an implication of serial processes [Balota et al., 2004; Whaley, 1978], others argued that pseudowords are rejected on the basis of time‐out or default mechanism [Dufau et al., 2012; Grainger and Jacobs, 1996]. In this study, pseudoword processing was assumed to engage the serial, sublexical, process. This assumption was supported by correlation analyses between stimulus length (as measured by the number of letters) and the RTs obtained in the baseline condition. The results showed that the correlation was significant only for pseudowords (r = 0.18, P = 0.017) and totally absent for words (r = 0.017, P = 0.83). This provided evidence in favor of the assumption that pseudowords had been processed serially while words had been processed globally.

The serial mechanism also occurs during writing. Regardless of the support or type of character, writing in alphabetic systems requires an ability to segment words or pseudowords into sequences of letters and to produce them one by one. Based on the performance of an acquired dyslexic and dysgraphic patient, Caramazza [1996] claimed that both writing and pseudoword reading place a fair amount of cognitive demands on an orthographic working memory system [see also Tainturier and Rapp, 2003 for a similar observation]. Although this idea of “graphemic buffer” remains controversial both in terms of its common role in reading and writing and its underlying brain structure [Cloutman et al., 2011; Hanley and Kay, 1998], it provides an interesting theoretical framework that deserves further attention.

The hypothesis that the PMd contributes to sublexical or serial reading is coherent with findings that damages to this area does not always affect visual word recognition [Anderson et al., 1990; Roeltgen, 1993] and that its contribution to reading is more important in reading disable populations. Monzalvo et al. [2012] compared brain activities of dyslexic and normal reader children. They found a strong reduction of activity within the left ventral occipito‐temporal cortex, at the site of the Visual Word Form Area, in dyslexic compared with normal readers. Interestingly, this activation was associated with a greater reliance on the PMd. The authors interpreted their finding as reflecting a reliance on manual gestures to compensate their reading deficits. Yet, the assumption that the difficulties to have fast access to lexical orthographic representations might push the participants to resort to more laborious reading mechanisms remains valid. Several pieces of evidence suggesting that the role of PMd might not be restricted to the motor component but could also be related to more central processes of language processing have been reported. For instance, activity within this area was found regardless of the format of letters and effectors [Rijntjes et al., 1999; Roux et al., 2009]. Keyboard typing also increased its activity compared with a control task [Longcamp et al., 2008; Purcell et al., 2011]. More direct evidence in favor of PMd's contribution to sublexical processes was provided by Rapp and Dufor [2011]. They found that during writing to dictation the activity within the superior premotor region near the posterior end of the superior frontal sulcus, which corresponded to our target area, was sensitive to word length but not to word frequency, which suggests a sensitivity of the area to a sublexical factor. Given these observations, it seems plausible that the contribution of the left PMd may not be restricted to pseudoword reading but could also generalize to other kinds of material that rely on sublexical or serial reading processes such as polysyllabic words or words presented in unusual orientations that block fast access to their lexical representations [Vinckier, et al. 2006].

Rostral Dorsal Premotor Cortex as an Interface between Cognitive and Motor Networks

Interestingly, Hanakawa [2011] proposed that the rostral part of the PMd acts as a gateway between cognitive and motor networks. Accordingly, this area may mediate the information flows between the two networks, making them operating interactively. In this perspective, a basic function of the area would be spatial information processing or “supramodal” spatial imagery that can be used for both motor planning and cognitive manipulation [Hanakawa et al., 2004]. Rather than being a “gateway”, the rostral PMd could also be considered as part of a larger cortical network interfacing cognitive and motor networks and underlying manual dexterity (including writing gestures). This larger network comprises dorsal and ventral premotor cortex and supplementary motor area [Galléa et al., 2005; Kuhtz‐Buschbeck et al., 2001].

No matter the status of the rostral PMd, the idea that this area acts as an interface between cognitive and motor networks can nicely explains our finding: While TMS over PMd affected more pseudoword than word reading regardless of whether or not the characters were similar to handwriting, TMS over M1, that is, an area that is more strongly involved in motor executive processes, evoked a greater MEP for handwritten than printed character regardless of stimulus’ lexicality. Moreover, this increase in excitability of the digit muscles that occurred already at stimulus onset, immediately followed by a reduction of excitability suggests that the cortico‐spinal activation of hand muscles result from an automatic rather than intentional process. The contrast between the results obtained during PMd and M1 stimulation suggests a possible transition from cognitive to motor component of writing activity and, therefore, their respective contribution to reading.

Conclusion and Perspective

In line with the idea of multimodality of language processing, we provided evidence for a functional role of a key area in the writing network, the so‐called Exner's area, in reading. This study showed that the relationship between reading and writing goes beyond a simple coactivation between the motor and visual regions previously reported in the literature. In the lexical decision task used here, our finding suggests that the contribution of the PMd to reading reflects shared cognitive processes in writing and reading rather than an evocation of writing‐related motor representations during reading. We argued that the serial, sublexical process seem to support both activities and could explain the present finding. More research is nevertheless needed to confirm this interpretation. In addition, the idea of shared cognitive processes does not rule out a possible contribution of the motor component under different circumstances. The relative contribution of different components of writing activity may depend on factors such as time‐course and location of the target area or the context in which its functional role is assessed [Silvanto et al., 2008]. Future experiments manipulating these factors would provide a more complete picture of the dynamic of language processing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests. They also warmly thank Pr. Patrick Chauvel and Dr. Agnès Trébuchon for taking medical responsibility during the study.

Table AI.

Characteristics of the words used in the lexical decision task

| Variables | Average |

|---|---|

| Written lexical frequency (number of occurrences per million) | 15,7 |

| Spoken lexical frequency (number of occurrences per million) | 12,7 |

| Bigram frequency (token) | 6692 |

| Number of phonlogical neighbours | 9,4 |

| Number of orthographic neighbours | 3,9 |

| Number of phonemes | 4,0 |

| Number of letters | 5,3 |

| Number of syllables | 1,5 |

| Phonological uniqueness point | 3,9 |

| Orthographic uniqueness point | 5,1 |

Footnotes

The presence of the TMS effect on pseudowords but not on words could simply be due to longer RTs obtained on pseudowords. To rule out this interpretation, we ran an additional analysis that grouped the stimuli according to their RTs obtained in the baseline condition. Words and pseudowords were separated into two groups, one with short RTs (RT < mean RT of all stimuli of the same type) and one with long RTs (RT > mean RT of all stimuli of the same type). Then, we compared the TMS effect obtained on “short RTs pseudowords” (mean RT = 613 ms) to the TMS effect obtained on “long RTs words” (mean RT = 670 ms). A disruptive effect of TMS, that is, an increase in RT compared with the baseline condition, was found only on pseudowords (P < 0.0001, Baseline = 613 ms; 60/100 ms = 688 ms; 120/160 ms = 700 ms). A facilitatory effect was found on words, probably due to a nonspecific intersensory facilitation [Terao et al., 1997] (Baseline = 670 ms; 60/100 ms = 626 ms; 120/160 ms = 643 ms). However, this result should be considered with caution given that running the analysis on a restricted set of material considerably reduced the number of observations.

To compare the TMS effects obtained in the lexical decision and image judgment tasks in a single analysis, we ran an ANOVA with stimulus type (pseudowords, words and images) and TMS (Baseline, 60/100 ms, 120/160 ms) as within subject factors. The analysis showed that the interaction between TMS and stimulus type almost reached significance [F(4,56) = 2.21, P = 0.08]. A decomposition of the interaction showed that the TMS effect was highly significant for pseudowords [F(2,28) = 10.1, P = 0.0005] but nonsignificant for words [F(2,28) = 1.7, P = 0.20] and images [F(2,28) = 1.9, P = 0.16].

REFERENCES

- Ahdab R, Ayache SS, Farhat WH, Mylius V, Schmidt S, Brugieres P, Lefaucheur JP (2013): Reappraisal of the anatomical landmarks of motor and premotor cortical regions for image‐guided brain navigation in TMS practice. Hum Brain Mapp 35:2435–2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts K, Weiss PH, Mohlberg H, Pieperhoff P, Eickhoff S, Gurd JM, Marshall JC, Shah NJ, Fink GR, Zilles K (2004): Analysis of neural mechanisms underlying verbal fluency in cytoarchitectonically defined stereotaxic space‐The roles of Brodmann areas 44 and 45. Neuroimage 22:42–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SW, Damasio AR, Damasio H (1990): Troubled letters but not numbers: Domain specific cognitive impairments following focal damage in frontal cortex. Brain 113:749–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Cortese MJ, Sergent‐Marshall SD, Spieler DH, Yap M (2004): Visual word recognition of single‐syllable words. J Exp Psychol Gen 133:283–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson P, Rapcsak S, Plante E, Chargualaf J, Chung A, Johnson S, Trouard T (2003): The neural substrates of writing: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Aphasiology 17:647–665. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnard M, Galléa C, De Graaf JB, Pailhous J (2007): Corticospinal control of the thumb‐index grip depends on precision of force control: A transcranial magnetic stimulation and functional magnetic resonance imagery study in humans. Eur J Neurosci 25:872–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza A (1996): The role of the graphemic buffer in reading. Cogn Neuropsychol 13:673–698. [Google Scholar]

- Cloutman LL, Newhart M, Davis CL, Heidler‐Gary J, Hillis AE (2011): Neuroanatomical correlates of oral reading in acute left hemispheric stroke. Brain Lang 116:14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M, Rastle K, Perry C, Langdon R, Ziegler J (2001): DRC: A dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychol Rev 108:204–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen PL, Kringelbach ML, Ellis AW, Whitney C, Holliday IE, Hansen PC (2009): Activation of the left inferior frontal gyrus in the first 200 ms of reading: evidence from magnetoencephalography (MEG). PloS One 4:e5359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH, Johnsrude IS, Hervais‐Adelman A, Taylor K, McGettigan C (2005): Lexical information drives perceptual learning of distorted speech: Evidence from the comprehension of noise‐vocoded sentences. J Exp Psychol Gen 134:222–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf JB, Frolov A, Fiocchi M, Nazarian B, Anton JL, Pailhous J, Bonnard M (2009): Preparing for a motor perturbation: Early implication of primary motor and somatosensory cortices. Hum Brain Mapp 30:575–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Pegado F, Braga LW, Ventura P, Nunes Filho G, Jobert A, Dehaene‐Lambertz G, Kolinsky R, Morais J, Cohen L (2010): How Learning to Read Changes the Cortical Networks for Vision and Language. Science 330:1359–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogil G, Ackermann H, Grodd W, Haider H, Kamp H, Mayer J, Riecker A, Wildgruber D (2002): The speaking brain: A tutorial introduction to fMRI experiments in the production of speech, prosody and syntax. J Neurolinguistics 15:59–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dronkers NF (1996): A new brain region for coordinating speech production. Nature 384:14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufau S, Grainger J, Ziegler JC (2012): How to say “no” to a nonword: A leaky competing accumulator model of lexical decision. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 38:1117–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan KJ, Pattamadilok C, Devlin JT (2010): Investigating Occipito‐temporal Contributions to Reading with TMS. J Cogn Neurosci 22:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner S. 1881. Untersuchungen über die Localisation der Functionen in der Grosshirnrinde des. Menschen: Wilhelm Braumüller.

- Galléa C, de Graaf JB, Bonnard M, Pailhous J (2005): High level of dexterity: Differential contributions of frontal and parietal areas. Neuroreport 16:1271–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger J, Jacobs AM (1996): Orthographic processing in visual word recognition: A multiple read‐out model. Psychol Rev 103:518–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grèzes J, Armony JL, Rowe J, Passingham RE (2003): Activations related to “mirror” and “canonical” neurones in the human brain: An fMRI study. Neuroimage 18:928–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanakawa T (2011): Rostral premotor cortex as a gateway between motor and cognitive networks. Neurosci Res 70:144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanakawa T, Honda M, Hallett M (2004): Amodal imagery in rostral premotor areas. Behav Brain Sci 27:406–407. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JR, Kay J (1998): Note: Does the graphemic buffer play a role in reading? Cogn Neuropsychol 15:313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington GS, Farias D, Davis CH, Buonocore MH (2007): Comparison of the neural basis for imagined writing and drawing. Hum Brain Mapp 28:450–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katanoda K, Yoshikawa K, Sugishita M (2001): A functional MRI study on the neural substrates for writing. Hum Brain Mapp 13:34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhtz‐Buschbeck JP, Ehrsson HH, Forssberg H (2001): Human brain activity in the control of fine static precision grip forces: an fMRI study. Eur J Neurosci 14:382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longcamp M, Anton J‐L, Roth M, Velay J‐L (2005a): Premotor activations in response to visually presented single letters depend on the hand used to write: A study on left‐handers. Neuropsychologia 43:1801–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longcamp M, Anton JL, Roth M, Velay JL (2003): Visual presentation of single letters activates a premotor area involved in writing. Neuroimage 19:1492–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longcamp M, Boucard C, Gilhodes J‐C, Anton J‐L, Roth M, Nazarian B, Velay J‐L (2008): Learning through hand‐or typewriting influences visual recognition of new graphic shapes: Behavioral and functional imaging evidence. J Cogn Neurosci 20:802–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longcamp M, Hlushchuk Y, Hari R (2011): What differs in visual recognition of handwritten vs. printed letters? An fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 32:1250–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longcamp M, Tanskanen T, Hari R (2006): The imprint of action: Motor cortex involvement in visual perception of handwritten letters. Neuroimage 33:681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longcamp M, Zerbato‐Poudou M‐T, Velay J‐L (2005b): The influence of writing practice on letter recognition in preschool children: A comparison between handwriting and typing. Acta Psychol 119:67–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainy N, Jung J, Baciu M, Kahane P, Schoendorff B, Minotti L, Hoffmann D, Bertrand O, Lachaux JP (2008): Cortical dynamics of word recognition. Hum Brain Mapp 29:1215–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattys SL, Davis MH, Bradlow AR, Scott SK (2012): Speech recognition in adverse conditions: A review. Lang Cogn Process 27:953–978. [Google Scholar]

- Monzalvo K, Fluss J, Billard C, Dehaene S, Dehaene‐Lambertz G (2012): Cortical networks for vision and language in dyslexic and normal children of variable socio‐economic status. Neuroimage 61:258–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray WS, Forster KI (2004): Serial mechanisms in lexical access: The rank hypothesis. Psychol Rev 111:721–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Honda M, Hirano S, Oga T, Sawamoto N, Hanakawa T, Inoue H, Ito J, Matsuda T, Fukuyama H (2002): Modulation of the visual word retrieval system in writing: a functional MRI study on the Japanese orthographies. J Cogn Neurosci 14:104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kuo WJ, Pegado F, Cohen L, Tzeng OJL, Dehaene S (2012): Universal brain systems for recognizing word shapes and handwriting gestures during reading. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:20762–20767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka M, Thabit MN, Koganemaru S, Nojima I, Fukuyama H, Mima T (2012): Writing's shadow: Corticospinal activation during letter observation. J Cogn Neurosci 24:1138–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New B, Pallier C, Brysbaert M, Ferrand L (2004): Lexique 2: A new French lexical database. Behav Res Methods 36:516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obleser J, Wise RJS, Alex Dresner M, Scott SK (2007): Functional integration across brain regions improves speech perception under adverse listening conditions. J Neurosci 27:2283–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pammer K, Hansen PC, Kringelbach ML, Holliday I, Barnes G, Hillebrand A, Singh KD, Cornelissen PL (2004): Visual word recognition: the first half second. Neuroimage 22:1819–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papathanasiou I, Filipovic SR, Whurr R, Rothwell JC, Jahanshahi M (2004): Changes in corticospinal motor excitability induced by non‐motor linguistic tasks. Exp Brain Res 154:218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattamadilok C, Morais J, Kolinsky R (2011): Naming in Noise: The Contribution of Orthographic Knowledge to Speech Repetition. Front Psychol 2:316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattamadilok C, Bulnes LC, Devlin JT, Bourguignon M, Morais J, Goldman S, Kolinsky R (2015): How Early Does the Brain Distinguish between Regular Words, Irregular Words, and Pseudowords during the Reading Process? Evidence from Neurochronometric TMS. J Cogn Neurosci 27:1259–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegado F, Nakamura K, Hannagan T (2014): How does literacy break mirror invariance in the visual system? Front Psychol 5:703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea M, Rosa E, Gomez C (2005): The frequency effect for pseudowords in the lexical decision task. Percept Psychophys 67:301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planton S, Jucla M, Roux F‐E, Démonet J‐F (2013): The “handwriting brain”: a meta‐analysis of neuroimaging studies of motor versus orthographic processes. Cortex 49:2772–2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ (2010): The anatomy of language: A review of 100 fmri studies published in 2009. Ann N Y Acad Sci 197:335–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ (2012): A review and synthesis of the first 20 years of PET and fMRI studies of heard speech, spoken language and reading. Neuroimage 62:816–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell JJ, Napoliello EM, Eden GF (2011): A combined fMRI study of typed spelling and reading. Neuroimage 55:750–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp B, Dufor O (2011): The neurotopography of written word production: an FMRI investigation of the distribution of sensitivity to length and frequency. J Cogn Neurosci 23:4067–4081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp B, Lipka K (2011): The literate brain: The relationship between spelling and reading. J Cogn Neurosci 23:1180–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Gomez P, McKoon G (2004): A diffusion model account of the lexical decision task. Psychol Rev 111:159–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijntjes M, Dettmers C, Büchel C, Kiebel S, Frackowiak RSJ, Weiller C (1999): A blueprint for movement: Functional and anatomical representations in the human motor system. J Neurosci 19:8043–8048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Luppino G (2001): The cortical motor system. Neuron 31:889–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Luppino G, Matelli M (1998): The organization of the cortical motor system: New concepts. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 106:283–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeltgen DP. 1993. Agraphia In: Heilman KM, Valenstein E, editors. Clinical Neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press; p 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, Pascual‐Leone A (2009): Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol 120:2008–2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux F‐E, Dufor O, Giussani C, Wamain Y, Draper L, Longcamp M, Démonet J‐F (2009): The graphemic/motor frontal area Exner's area revisited. Ann Neurol 66:537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvanto J, Lavie N, Walsh V (2005): Double dissociation of V1 and V5/MT activity in visual awareness. Cereb Cortex 15:1736–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvanto J, Muggleton N, Walsh V (2008): State‐dependency in brain stimulation studies of perception and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci 12:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinska MW, Khadilkar M, Campbell‐Ratcliffe J, Quevenco F, Devlin JT (2012): Early and sustained supramarginal gyrus contributions to phonological processing. Front Psychol 3:161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieser L, Aubert S, Bonnard M (2013): Involvement of SMAp in the intention‐related long latency stretch reflex modulation: a TMS study. Neuroscience 246:329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tainturier M‐J, Rapp B (2003): Is a single graphemic buffer used in reading and spelling? Aphasiology 17:537–562. [Google Scholar]

- Terao Y, Ugawa Y, Suzuki M, Sakai K, Hanajima R, Gemba‐Shimizu K, Kanazawa I (1997): Shortening of simple reaction time by peripheral electrical and submotor‐threshold magnetic cortical stimulation. Exp Brain Res 115:541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Galen GP (1991): Handwriting: Issues for a psychomotor theory. Hum Movement Sci 10:165–191. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneau M, Beaucousin V, Herve P‐Y, Duffau H, Crivello F, Houde O, Mazoyer B, Tzourio‐Mazoyer N (2006): Meta‐analyzing left hemisphere language areas: phonology, semantics, and sentence processing. Neuroimage 30:1414–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinckier F, Naccache L, Papeix C, Forget J, Hahn‐Barma V, Dehaene S, Cohen L (2006): “What” and “Where” in Word Reading: Ventral Coding of Written Words Revealed by Parietal Atrophy. J Cogn Neurosci 18:1998–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmakers E‐J, Ratcliff R, Gomez P, McKoon G (2008): A diffusion model account of criterion shifts in the lexical decision task. J Memory Lang 58:140–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmakers E‐J, Steyvers M, Raaijmakers JGW, Shiffrin RM, Van Rijn H, Zeelenberg R (2004): A model for evidence accumulation in the lexical decision task. Cogn Psychol 48:332–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh V, Pascual‐Leone A, Kosslyn SM. 2003. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: A neurochronometrics of mind. MIT press: Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Wassermann EM (1998): Risk and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: report and suggested guidelines from the International Workshop on the Safety of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, June 5–7, 1996. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 108:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley CP (1978): Word‐nonword classification time. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav 17:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wheat KL, Cornelissen PL, Frost SJ, Hansen PC (2010): During visual word recognition, phonology is accessed within 100 ms and may be mediated by a speech production code: Evidence from magnetoencephalography. J Neurosci 30:5229–5233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Saygin AP, Sereno MI, Iacoboni M (2004): Listening to speech activates motor areas involved in speech production. Nat Neurosci 7:701–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead ZVJ, Barnes GR, Penny W, Moran R, Teki S, Price CJ, Leff AP (2014): Reading front to back: MEG evidence for early feedback effects during word recognition. Cerebral Cortex 24:817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Kemeny S, Park G, Frattali C, Braun A (2005): Language in context: Emergent features of word, sentence, and narrative comprehension. Neuroimage 25:1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MJ, Sibley DE, Balota DA, Ratcliff R, Rueckl J (2015): Responding to nonwords in the lexical decision task: Insights from the English Lexicon Project. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 41:597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoncheva YN, Zevin JD, Maurer U, McCandliss BD (2010): Auditory selective attention to speech modulates activity in the visual word form area. Cerebral Cortex 20:622–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousry TA, Schmid UD, Alkadhi H, Schmidt D, Peraud A, Buettner A, Winkler P (1997): Localization of the motor hand area to a knob on the precentral gyrus. A new landmark. Brain 120:141–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]