Abstract

Background:

Trauma histories may increase risk of perinatal psychiatric episodes. We designed an epidemiological population-based cohort study to explore if adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in girls increases risk of later postpartum psychiatric episodes.

Methods:

Using Danish registers, we identified women born in Denmark between January 1980 and December 1998 (129,439 childbirths). Exposure variables were ACE between ages 0 and 15 including: (1) family disruption, (2) parental somatic illness, (3) parental labor market exclusion, (4) parental criminality, (5) parental death, (6) placement in out-of-home care, (7) parental psychopathology excluding substance use, and (8) parental substance use disorder. Primary outcome was first occurrence of in- or outpatient contact 0–6 months postpartum at a psychiatric treatment facility with any psychiatric diagnoses, ICD-10, F00-F99 (N = 651). We conducted survival analyses using Cox proportional hazard regressions of postpartum psychiatric episodes.

Results:

Approximately 52% of the sample experienced ACE, significantly increasing risk of any postpartum psychiatric diagnosis. Highest risks were observed among women who experienced out-of-home placement, hazard ratio (HR) 2.57 (95% CI: 1.90–3.48). Women experiencing two adverse life events had higher risks of postpartum psychiatric diagnosis HR: 1.88 (95% CI: 1.51–2.36), compared to those with one ACE, HR: 1.24 (95% CI: 1.03–49) and no ACE, HR: 1.00 (reference group).

Conclusions:

ACE primarily due to parental psychopathology and disability contributes to increased risk of postpartum psychiatric episodes; and greater numbers of ACE increases risk for postpartum psychiatric illness with an observed dose-response effect. Future work should explore genetic and environmental factors that increase risk and/or confer resilience.

Keywords: acute stress reaction, adverse life events, mood disorders, postpartum depression

1 |. BACKGROUND

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) are relatively common in the general population—more than half of adults report at least one adverse childhood event (Brown, Perera, Masho, Mezuk, & Cohen, 2015). ACE appears to play a vital role in the development of psychiatric morbidity in adulthood (Brown et al., 2015; Felitti et al., 1998), including major depression (MDD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse disorders, and others (Bergink et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2015; Chapman et al., 2004; Dahl et al., 2017; Edwards, Holden, Felitti, & Anda, 2003; Heim et al., 2002). Moreover, the number of early adverse events and MDD has a dose-response relationship (Dahl et al., 2017; Dunn, McLaughlin, Slopen, Rosand, & Smoller, 2013; Keyes et al., 2014) suggesting that the effect of ACE on depression risk in general is cumulative (Kessler et al., 2010). ACE is a critically important public health issue as negative events experienced in childhood or adolescence can confer an enduring deleterious effect on mental health across the entire lifespan (Gilman, Kawachi, Fitzmaurice, & Buka, 2003; Korkeila et al., 2005).

Women experience MDD at twice the rate of men across their lifetime including episodes of depression that occur outside of the perinatal period (Kessler, 2003; Pedersen et al., 2014; Seedat et al., 2009). However, women are particularly vulnerable to psychiatric illness in the postpartum period (Munk-Olsen, Laursen, Pedersen, Mors, & Mortensen, 2006; Munk-Olsen et al., 2016) for a range postpartum psychiatric disorders including postpartum depression (PPD) and postpartum psychosis. PPD in particular has a prevalence of 10–15% across the world and greater prevalence in high-risk populations of women (Gavin et al., 2005). ACE may be important risk factors for onset of depression during the perinatal period (Ansara, Cohen, Gallop, Kung, & Schei, 2005; Faisal-Cury, Menezes, d’Oliveira, Schraiber, & Lopes, 2013; Kendall-Tackett, 2007; Meltzer-Brody et al., 2013; Onoye, Goebert, Morland, Matsu, & Wright, 2009; Plaza et al., 2012; Records & Rice, 2009; Robertson-Blackmore et al., 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2010; Silverman & Loudon, 2010a, 2010b). Women who experience traumatic life events appear to have an increased risk of perinatal depression during pregnancy (antenatal depression), postpartum (PPD), or throughout the entire perinatal period (Meltzer-Brody et al., 2011, 2013; Plaza et al., 2012; Robertson-Blackmore et al., 2013). However, in some studies, history of trauma increased the risk of antenatal depression, but not PPD (Robertson-Blackmore et al., 2013), whereas in others, the risk of PPD was increased in women who experienced ACE (Plaza et al., 2012; Records & Rice, 2009).

Studying sensitive topics such as early life stress and mental health is challenging, and many of the prior studies referenced above had relatively small sample sizes or relied on self-reported data with possible recall bias, underreporting, misclassification, and subsequent biased results. We designed an epidemiological population-based cohort study to explore if women experiencing early adverse life events during their childhood/adolescence are at risk of postpartum psychiatric episodes following childbirth. In particular, we focused on early adverse life events that mainly, but not exclusively, involved parental psychopathology and disability. Further, we assessed a range of disorders observed postpartum, including postpartum psychosis, depression, and acute stress reactions specifically. Using information from nationally inclusive registers, the aims of this present work were to (a) describe the associations between early childhood adversity and postpartum psychiatric episodes and (b) to investigate the impact of number of events to assess for a dose-response effect on onset of postpartum psychiatric episodes.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Study design

We designed an epidemiological population-based cohort study to examine if girls experiencing adverse life events in childhood and adolescence are at increased risk of postpartum psychiatric episodes after they become mothers. For this purpose, 482,295 women born in Denmark to Danish-born parents between January 1980 and December 1998 were found. Of these, 387,763 did not give birth, 31 had their first child before age 15, and 9,421 were diagnosed with a psychiatric illness before having their first child. Among the remaining 85,080 women, we identified 129,439 childbirths between 1995 and 2012. The follow-up time started at time of childbirth and follow-up ended 182 days later, at date of first recorded postpartum mental disorder (any diagnoses between 0 and 182 days/6 months postpartum, at date of emigration, or date of death, whichever came first. Women who gave birth before age 15 years were excluded from the study. Childbirths with records of psychiatric diagnoses before the birth where also excluded from the study to ensure that postpartum psychiatric episodes were incident episodes (first-time psychiatric diagnoses).

Linkage of relevant population register data was ensured through a personal identification number assigned to all citizens in Denmark. For the present study, we linked each child to legal parents through The Central Registration System, a register that holds updated information on vital status, migration, and links to family members. All diagnoses are recorded using ICD-8 codes until 1994, and ICD-10 codes from 1994 and onwards. For the present study the included information came from a range of data sources/population registers. Note, as various population registers were initiated at different time points, we defined our study population by including women born 1980 or later, to ensure as complete exposure information as possible.

2.2 |. Exposure definition: Early adverse life events

We defined the main exposure variables as a panel of various early life events in children from 0 to 15 years. Using the Danish population registers, the selected various early adverse life events were mainly those that involved parental psychopathology and disability and included the following: (1) family disruption, (2) parental somatic illness, (3) parental labor market exclusion, (4) parental criminality, (5) parental death, (6) placement in out-of-home care, and (7).parental psychopathology excluding substance use disorders, and (8) parental substance use disorder as in previous studies from our group (Bergink et al., 2016; Dahl et al., 2017). For all identified adversities we used information on specific dates for each adversity and focused on the first record of any of the adversities/exposures in each child in the cohort.

Familial disruption was considered to be any other household composition than the cohort member living with both legal parents (Pedersen, 2011). Please note that records of other included adversities such as placement in out-of-home care, parental death, or parental imprisonment per definition meant that the individual cohort member was not sharing an address with both legal parents, and consequently these were not included in the definition of familial disruption in particular to avoid any misclassification.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) composed the underlying basis for assessing parental chronic somatic disorders (Thygesen, Christiansen, Christensen, Lash, & Sorensen, 2011). Only diagnosis assigned point values according to the CCI were defined as an exposure. Furthermore, we excluded all parental psychiatric diagnoses used in the CCI since these were already encompassed in records of parental psychopathology. First registered admission as either in- or outpatient with any CCI diagnosis in The National Patient Register (Lynge, Sandegaard, & Rebolj, 2011) was regarded an exposure.

Using data from the register on Integrated Database for Labour Market Research (IDA) (Petersson, Baadsgaard, & Thygesen, 2011) we assessed parental labor market exclusion. Exposure was first record of the parent being excluded from the workforce. Note our definition only included variables indicating a permanent exclusion from the work force, which mainly were records of disability pension.

Parental imprisonment was assessed through The National Crime Register held by Statistics Denmark. Unconditional sentences according to The Danish Penal Law, the Law on Psychedelic Drugs, the Offensive Weapons Act, and the Law on Drink Driving was included as an exposure of adversity.

Records on parental death, including both natural and unnatural cause of death were obtained through The Danish Civil Registration System (Pedersen, 2011).

Records on placements in out-of-home care during upbringing were obtained through the register on Support for Marginalized Children and Adolescents, and included information on placement among others in family foster care, network foster family, 24-hr care center, and boarding schools.

Parental psychopathology was defined as a parent’s first registered admission as an in- or outpatient with any psychiatric diagnosis (ICD-8: 290–315; ICD-10: F00-F99) in The Psychiatric Central Research Register (Mors, Perto, & Mortensen, 2011). Further subgroups were defined to explore possible effects of substance use specifically: Parental psychopathology excluding substance use (ICD-8: 291.x9, 294.39, 303.x9, 303.20, 303.28, 303.90, 304.x9, ICD-10: F10-F19, and substance use as a separate category (Mors et al., 2011).

2.3 |. Outcome definition: Postpartum psychiatric disorders

The outcome of interest in this study was first occurrence of an in- or outpatient contact 0–6 months (0–182 days) postpartum at a psychiatric treatment facility with any psychiatric diagnoses, ICD-8 290–315 or ICD-10 F00-F99. We further examined subtypes of postpartum psychiatric disorder based on three groups: PPD (ICD-10: F32–F33 excluding F32.3), postpartum psychosis (ICD-10: F20, F23, F25, F28–F31, and F32.3), and postpartum acute stress reaction (ICD-10: F43). Data on diagnoses were obtained through The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (Mors, Perto, & Mortensen, 2011).

2.4 |. Statistical analyses

We conducted survival analyses using Cox proportional hazard regression and estimated the main outcome measure with hazard ratios (HRs). Time since childbirth was treated as the underlying time axis, and all estimates were adjusted for age as a time-dependent variable in 5-year intervals and birth number (first birth, second, or higher birth). Further adjustments were made for clustering (individual women giving birth multiple times during the study period). We also examined the association of early adverse life event by subtype of postpartum psychiatric disorder based on three groups: PPD, postpartum psychosis, and postpartum acute stress reaction. For all analyses the reference group was mothers not exposed to any of the defined early life events during upbringing. To evaluate the effect of an increasing number of different adversities on disease risk, cohort members were grouped according to number of adversities experienced. Each adversity was assessed at first date of the adversity of interest and the analyses of numbers of adversities subsequently described the effect of experiencing 0, 1, 2, or 3+ different adversities until age 15. To present absolute risks of postpartum psychiatric episodes, we calculated cumulative incidences for disease onset for number of early life adversities by competing risk regression with death as the competing event. All analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software, version 13 (StataCorp, 2013).

3 |. RESULTS

Using the Danish population registers, we examined all women who were born in Denmark from 1980 to 1998 and gave birth in Denmark between January 1995 and December 2012. There were 129,439 childbirths by 85,080 women (Table 1), and the mean age at birth of first child for these women was 23.95 (SD = 3.51).

TABLE 1.

Number and percentages of childbirths and cases exposed to each type of adversity

| Total | Any Postpartum Psychiatric Diagnosis | Postpartum Depression | Postpartum Psychosis |

Postpartum Acute Stress Reaction |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 129,439 | N = 651 | N = 264 | N = 31 | N = 234 | ||||||

| Childbirths | Childbirths | Childbirths | Childbirths | Childbirths | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Exposure to adverse event | ||||||||||

| Any adverse event | 68,351 | 52.81 | 412 | 63.29 | 160 | 60.61 | 17 | 54.84 | 152 | 64.96 |

| Family disruption | 46,840 | 36.19 | 285 | 43.78 | 106 | 40.15 | 104 | 44.44 | ||

| Parental somatic illness | 19,545 | 15.10 | 128 | 19.66 | 51 | 19.32 | 45 | 19.23 | ||

| Parental labor market exclusion | 12,323 | 9.52 | 86 | 13.21 | 26 | 9.85 | 32 | 13.68 | ||

| Parental imprisonment | 9,991 | 7.72 | 62 | 9.52 | 19 | 7.20 | 23 | 9.83 | ||

| Parental death | 4,361 | 3.37 | 23 | 3.53 | 7 | 2.65 | 9 | 3.85 | ||

| Placement in out-of-home care | 4,950 | 3.82 | 56 | 8.60 | 17 | 6.44 | 26 | 11.11 | ||

| Parental psychopathology excl.SUD | 8,227 | 6.36 | 67 | 10.29 | 23 | 8.71 | 23 | 9.83 | ||

| Parental substance use disorder | 4,107 | 3.17 | 26 | 3.99 | 10 | 3.79 | 7 | 2.99 | ||

| Number of adverse events | ||||||||||

| 0 | 61,088 | 47.19 | 239 | 36.71 | 104 | 39.39 | 14 | 45.16 | 82 | 35.04 |

| 1 | 42,681 | 32.97 | 217 | 33.33 | 91 | 34.47 | 79 | 33.76 | ||

| 2 | 15,398 | 11.90 | 123 | 18.89 | 52 | 19.70 | 47 | 20.09 | ||

| 3 or more | 10,272 | 7.94 | 72 | 11.06 | 17 | 6.44 | 26 | 11.11 | ||

Out of the 651 postpartum psychiatrics diagnoses, 122 were diagnosed with disorders not included in the three postpartum subcategories.

Conferring to Danish legislation cell sizes below 3 are not permitted, hence the empty cells: SUD, substance use disorders.

More than half of the entire study sample (~52%) experienced some form of an early adverse life event, mainly in the form of parental psychopathology and disability. The types of childhood adverse life events and risk for any type of postpartum psychiatric disorders are presented in Table 2. The greatest risks for any type of postpartum psychiatric episodes were observed with history of placement in out-of-home care (HR = 2.57; 95% CI: 1.90–3.48), parental psychopathology excluding substance abuse (HR = 1.90; CI: 1.44–2.50), parental labor market exclusion (HR = 1.63; 95% CI 1.26–2.10, and parental somatic illness (HR = 1.56; 95% CI 1.26–1.94).

TABLE 2.

Hazard Ratios (HR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for postpartum psychiatric episodes for each type of adversity

| Any Postpartum Psychiatric Diagnosis |

Postpartum Depression |

Postpartum Psychosis |

Postpartum Acute Stress Reaction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR(95%CI) | HR(95%CI) | HR(95%CI) | HR(95%CI) | |

| Exposure to adverse event | ||||

| Family disruption | 1.44 (1.21–1.72) | 1.34 (1.02–1.77) | .99 (.41–2.37) | 1.42 (1.06–1.90) |

| Parental somatic illness | 1.56 (1.26–1.94) | 1.54 (1.10–2.17) | 1.00 (.35–2.86) | 1.51 (1.05–2.17) |

| Parental labor market exclusion | 1.63 (1.26–2.10) | 1.27 (.81–1.98) | 1.56 (.52–4.63) | 1.60 (1.05–2.42) |

| Parental criminality | 1.43 (1.07–1.90) | 1.14 (.70–1.87) | .37 (.05–2.85) | 1.38 (.86–2.22) |

| Parental death | 1.25 (.82–1.93) | .95 (.44–2.06) | N/A | 1.34 (.67–2.67) |

| Placement in out-of-home care | 2.57 (1.90–3.48) | 2.15 (1.27–3.64) | 1.48 (.31–7.12) | 3.02 (1.89–4.81) |

| Parental psychopathology excl.SUD | 1.90 (1.44–2.50) | 1.67 (1.06–2.65) | .91 (.20–4.10) | 1.72 (1.08–2.76) |

| Parental substance use disorder | 1.47 (.97–2.21) | 1.46 (.76–2.82) | N/A | 1.04 (.48–2.26) |

| Number of adverse events | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1 | 1.24 (1.03–1.49) | 1.26 (.95–1.67) | .84 (.35–2.05) | 1.25 (.92–1.71) |

| 2 | 1.88 (1.51–2.36) | 2.02 (1.44–2.83) | 1.49 (.53–4.17) | 1.92 (1.33–2.77) |

| 3 or more | 1.62 (1.23–2.12) | 1.00 (.59–1.71) | .72 (.16–3.32) | 1.51 (.97–2.37) |

The comparison group is persons who were not exposed to any adversity. Adjusted for time since childbirth, age in 5-year intervals and birth number (first birth, second, or higher birth). Out of the 651 postpartum psychiatrics diagnoses, 122 were diagnosed with disorders not included in the three postpartum subcategories.

For postpartum psychosis there were too few exposed cases in four of the adversity categories to reliably estimate hazard ratios.

The findings by specific subtype of postpartum psychiatric illness were similar to those observed for the overall group of any type of postpartum psychiatric disorder (Table 2). For example, a history of placement in out-of-home care was associated with the greatest risk for both developing PPD HR = 2.15; 95% CI: 1.27–3.64 and postpartum acute stress reaction HR = 3.02; 95% CI: 1.89–4.81. Adverse life history of parental psychopathology excluding substance abuse was associated with the second greatest risk for the subtypes of PPD HR = 1.67; CI: 1.06–2.65, and postpartum acute stress HR = 1.72; 95% CI: 1.08–2.76. Across all studied adversities, we did not observe an increased risk of postpartum psychosis.

In addition, we also mutually adjusted results for early life adversity and subsequent risk of postpartum psychiatric episodes. These results are presented in Table 3, and take into account the potential correlation of individual effects of the single adversities, adjusted for any additional effects of correlated adversities. As expected all results were attenuated when compared to the effect sizes presented in Table 2, which suggests at least some of the adversities are correlated.

TABLE 3.

Hazard Ratios (HR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) with mutually adjusted results for early life adversity and risk of postpartum psychiatric episodes

| Any Postpartum Psychiatric Diagnosis |

Postpartum Depression |

Postpartum Psychosis |

Postpartum Acute Stress Reaction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR(95%CI) | HR(95%CI) | HR(95%CI) | HR(95%CI) | |

| Exposure to adverse event | ||||

| Family disruption | 1.23 (1.05–1.44) | 1.14 (.89–1.48) | .98 (.43–2.23) | 1.20 (.92–1.56) |

| Parental somatic illness | 1.26 (1.03–1.55) | 1.38 (.99–1.91) | 1.04 (.35–3.06) | 1.19 (.84–1.66) |

| Parental labor market exclusion | 1.10 (.86–1.41) | .87 (.56–1.36) | 1.98 (.70–5.63) | 1.09 (.73–1.63) |

| Parental criminality | .99 (.74–1.32) | .83 (.49–1.38) | .36 (.05–2.37) | .95 (.58–1.54) |

| Parental death | .82 (.53–1.26) | .64 (.30–1.39) | N/A | .89 (.44–1.79) |

| Placement in out-of-homecare | 1.94 (1.42–2.63) | 1.82 (1.05–3.15) | 1.94 (.45–8.35) | 2.49 (1.54–4.03) |

| Parental psychopathology excl.SUD | 1.41 (1.05–1.89) | 1.33 (79–2.23) | 1.11 (.26–4.67) | 1.32 (.82–2.13) |

| Parental substance use disorder | .76 (.48–1.20) | .95 (.44–2.09) | N/A | .52 (.23–1.20) |

The comparison group is persons who were not exposed to any adversity. The results are mutually adjusted and adjusted for time since childbirth, age in 5-year intervals and birth number (first birth, second, or higher birth).

Out of the 651 postpartum psychiatrics diagnoses, 122 were diagnosed with disorders not included in the three postpartum subcategories.

For postpartum psychosis there were too few exposed cases in four of the adversity categories to reliably estimate hazard ratios.

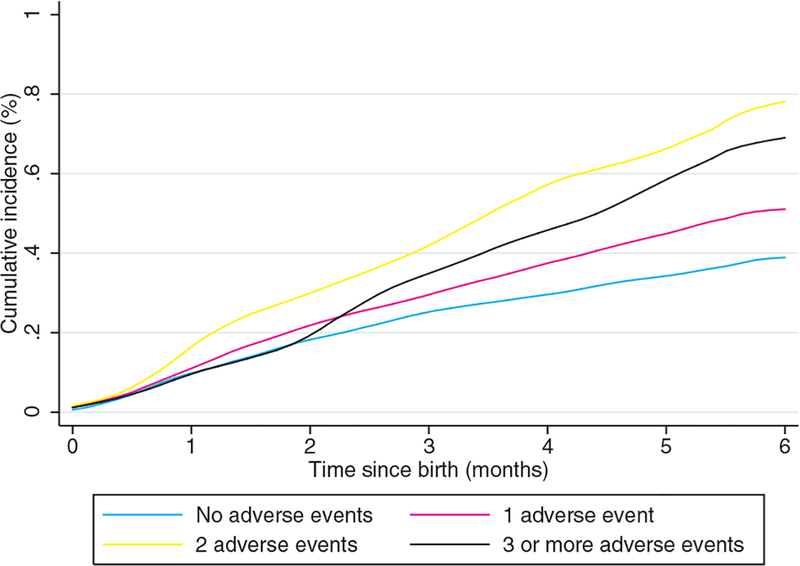

We also observed a cumulative effect (ranging from .4 to .8%) whereby the number of childhood adverse events was associated with increased risk of postpartum psychiatric episodes jointly with a threshold effect (Fig. 1). Women who experienced two adverse life events had the greatest risk for onset of overall postpartum psychiatric episodes (HR = 1.88; 95% CI 1.51–2.36) as well as by subtype of postpartum psychiatric disorder for both PPD (HR = 2.02; 95% CI = 1.44–2.83) and postpartum acute stress reaction (HR = 1.92; 95% CI = 1.33–2.77, Table 2). This risk was markedly higher than having zero or one adverse life event for overall postpartum psychiatric episodes (HR = 1.24; 95% CI 1.03–1.49), which was also observed by subtype of disorder.

FIGURE 1.

Cumulative incidence of any postpartum psychiatric diagnosis by number of different adversities experienced at age 0–15 years

4 |. DISCUSSION

In the Danish population-based registers, we examined if girls experiencing adverse life events in childhood and adolescence due to parental psychopathology and disability are at increased risk of postpartum psychiatric episodes following childbirth. To our knowledge, this study is the largest to date that has examined this question, and our findings suggest significant associations between various childhood adverse life events and the development of postpartum psychiatric episodes.

Our findings demonstrated that a greater number of early adverse life events is associated with increased risk of postpartum episodes with an observed dose-response effect, from 0 to 1 and 2 records of adversities, which has been shown for MDD in general, but rarely for postpartum psychiatric episodes (Perry et al., 2016). This finding was observed for any type of postpartum psychiatric as a group and by subtype of disorder, except for three or more adversities, which may be due to limited statistical power based on few observations. Our findings also demonstrate that some of the adversities are correlated, since our results were attenuated when comparing to the effect sizes presented in Table 2 versus the mutually adjusted results in Table 3. Nonetheless, we did observe a persistent effect of ACE on risk of postpartum psychiatric episodes with a dose-response effect and believe this is the first paper to report on this finding in perinatal mood disorders using a large population-based cohort. The negative experience of sustaining multiple adverse life events throughout childhood could result in multiple biologic changes by increasing allostatic load, or the cumulative stress on the body that is a sum of lifetime stress exposure (Geronimus, Hicken, Keene, & Bound, 2006). Possible explanations for this could be lasting alterations of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal stress axis reactivity (Wilkinson & Goodyer, 2011), and other biologic changes including epigenetic modification (Perroud et al., 2011), persistent alterations in transcriptional control of stress-responsive pathways (Schwaiger et al., 2016), and shortened telomere length (Vincent et al., 2017).

For 68,351 childbirths in the entire cohort and more than half of the study population the mothers giving birth had records of at least one childhood adversity during childhood and adolescence, demonstrating the high prevalence of early adverse life events in the general population. Among these 651 women subsequently developed a postpartum psychiatric episode, which confirms previous findings that childhood adversity is a risk factor for postpartum psychiatric illness (Plaza et al., 2012; Records & Rice, 2009). Since the experience of childhood adversity is unfortunately relatively common, a history of a childhood adversity has a low positive predictive value for the later onset of a postpartum psychiatric episode. Before our findings and those from previous work identifying risk factors for postpartum psychiatric disorders can be translated into any routine clinical practice recommendations for screening purposes, we need to increase our understanding of why some women develop psychiatric illness following childbirth, whereas others do not. Current knowledge suggests a two-hit model whereby underlying genetic vulnerability in combination with environmental stressors triggers the onset of psychiatric illness (Lesse, Rether, Groger, Braun, & Bock, 2017). Future work that integrates epidemiological and genetic risk will lead to greater clarification of etiology, nosology, and risk status that may in the future lead to meaningful prediction tools for application in clinical settings.

In particular, our results indicate that parental psychopathology and disability have a significant contribution on whether a woman will develop a postpartum psychiatric episode. This is likely due to both the genetic loading that comes from having a parent with mental illness, in addition to the environmental exposure associated from living with a parent with psychopathology and disability. Thus, parental history of onset of psychopathology following childbirth supports the genetic hypothesis for psychiatric illness in general. But, it is also consistent with recent work demonstrating increased heritability of perinatal mood disorders in particular (Viktorin et al., 2016). Consequently, the growing literature on using polygenic risk scores to construct a diathesis-stress model are of great interest to increasing our understanding the vulnerability or risk of developing depression or other psychiatric disorders. For example, recent work demonstrates an extra risk for individuals with combined genetic vulnerability and high number of reported personal life stressors beyond what would be expected from the additive contributions of these factors to the liability for depression, supporting the multiplicative diathesis-stress model for depression in general. Further, this work suggests that the underlying causes of depression may differ for men versus women (Colodro-Conde et al., 2017). Therefore, while parental psychopathology serves as marker for a genetic vulnerability to psychiatric disorders and depression in general, it is also an important marker of environmental stress for the individual girl who likely was raised in a more stressful environment. In addition, women may have increased vulnerability for depression in general due to genetic risk. Therefore, future work will need to tease apart these contributions and will require both robust genetic and environmental data to examine polygenic risk in postpartum psychiatric disorders.

As for all studies, our results should be considered in the light of the following limitations: First, our study does not include childhood adverse life events of sexual and physical abuse as the numbers of reported cases in the Danish registers were too small to include and there are specific restrictions under Danish law, to report results only when no individuals can be recognized. Second, as we have described, the adverse events identified using the Danish registers are primarily those associated with parental psychopathology and disability. Third, The register data does not allow for determination of precise timing of when any particular adversity may have negatively influenced the lives of the individual children. Fourth, we had limited power to explore differences of all specific types of postpartum psychiatric episodes; specifically for postpartum psychosis, which has been shown to have distinctly lower prevalence but is relatively rare and is often considered part of a bipolar spectrum (Bergink et al., 2012; Di Florio et al., 2013). Our definition of postpartum psychiatric episodes was based on records of in- or outpatient hospital psychiatric treatment by a specialist. Primary care visits were not included in this analysis. Therefore, our results may not directly translate to milder forms of postpartum psychiatric episodes, including, for example, mild to moderate episodes of PPD that would have initially presented to a primary care provider. It is important to note that the prevalence of postpartum episodes in register based data is markedly less than reported in general prevalence studies of postpartum women using patient self-report forms such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987). Fifth, we did not examine comorbidity with PTSD. However, in contrast to the limitations mentioned above, our study is the biggest to date on this topic, and does not rely on self-report of adverse life events but rather is population register-based information, thereby limiting bias and confounding.

4.1 |. Conclusion

The experience of childhood adverse life events primarily due to parental psychopathology and disability contributes to increased risk for onset of postpartum psychiatric episodes. Further, the experience of greater numbers of adverse events increases the risk for postpartum psychiatric illness with an observed dose-response effect. Future work in the area of early adverse life events and postpartum psychiatric episodes should focus on the interaction between genetic and environmental factors that increase risk and/or confer resilience.

Funding information

Contract grant sponsor: NIH; Contract grant number: 1R01MH104468-01; Contract grant sponsor: Lundbeck Foundation: R155-2014-1724.

REFERENCES

- Ansara D, Cohen MM, Gallop R, Kung R, & Schei B (2005). Predictors of women’s physical health problems after childbirth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 26(2), 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergink V, Bouvy PF, Vervoort JS, Koorengevel KM, Steegers EA, & Kushner SA (2012). Prevention of postpartum psychosis and mania in women at high risk. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(6), 609–615. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11071047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergink V, Larsen JT, Hillegers MH, Dahl SK, Stevens H, Mortensen PB, … Munk-Olsen T (2016). Childhood adverse life events and parental psychopathology as risk factors for bipolar disorder. Translational Psychiatry, 6(10), e929 10.1038/tp.2016.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MJ, Perera RA, Masho SW, Mezuk B, & Cohen SA (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner aggression in the US: Sex differences and similarities in psychosocial mediation. Social Science & Medicine, 131, 48–57. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, & Anda RF (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(2), 217–225. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colodro-Conde L, Couvy-Duchesne B, Zhu G, Coventry WL, Byrne EM, Gordon S, … Martin NG (2017). A direct test of the diathesis-stress model for depression. Molecular Psychiatry 10.1038/mp.2017.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, & Sagovsky R (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl SK, Larsen JT, Petersen L, Ubbesen MB, Mortensen PB, Munk-Olsen T, & Musliner KL (2017). Early adversity and risk for moderate to severe unipolar depressive disorder in adolescence and adulthood: A register-based study of 978,647 individuals. Journal of Affective Disorders, 214, 122–129. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio A, Forty L, Gordon-Smith K, Heron J, Jones L, Craddock N, & Jones I (2013). Perinatal episodes across the mood disorder spectrum. Journal of the American Medical Association: Psychiatry, 70(2), 168–175. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N, Rosand J, &Smoller JW (2013). Developmental timing of child maltreatment and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation in young adulthood: Results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Depression and Anxiety, 30(10), 955–964. 10.1002/da.22102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, & Anda RF (2003). Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the adverse childhood experiences study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 1453–1460. https://doi.Org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal-Cury A, Menezes PR, d’Oliveira AFPL, Schraiber LB, & Lopes CS (2013). Temporal relationship between intimate partner violence and postpartum depression in a sample of low income women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17(7), 1297–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V,… Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, & Swinson T (2005). Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 106(5 Pt 1), 1071–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, & Bound J (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826–833. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, & Buka SL (2003). Family disruption in childhood and risk of adult depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(5), 939–946. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Wagner D, Wilcox MM, Miller AH, & Nemeroff CB (2002). The role of early adverse experience and adulthood stress in the prediction of neuroendocrine stress reactivity in women: A multiple regression analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 15(3), 117–125. 10.1002/da.10015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett KA (2007). Violence against women and the perinatal period: The impact of lifetime violence and abuse on pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding. Trauma Violence Abuse, 8(3), 344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC (2003). Epidemiology of women and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 74(1), 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, … Williams DR (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 378–385. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Pratt C, Galea S, McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, & Shear MK (2014). The burden of loss: Unexpected death of a loved one and psychiatric disorders across the life course in a National Study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(8), 864–871. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkeila K, Korkeila J, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M, Kivela SL, Sil-lanmaki L, & Koskenvuo M (2005). Childhood adversities, adult risk factors and depressiveness: A population study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(9), 700–706. 10.1007/s00127-005-0969-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesse A, Rether K, Groger N, Braun K, & Bock J (2017). Chronic postnatal stress induces depressive-like behavior in male mice and programs second-hit stress-induced gene expression patterns of OxtR and AvpR1a in adulthood. Molecular Neurobiology, 54(6), 4813–4819. 10.1007/sl2035-016-0043-8. Epub 2016 Aug 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, & Rebolj M (2011). The Danish National Patient Register. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(7 Suppl), 30–33. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Brody S, Bledsoe-Mansori SE, Johnson N, Killian C, Hamer RM, Jackson C, … Thorp J (2013). A prospective study of perinatal depression and trauma history in pregnant minority adolescents. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 208(3), 211 e211–217. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Brody S, Zerwas S, Leserman J, Holle AV, Regis T, & Bulik C (2011). Eating disorders and trauma history in women with perinatal depression. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(6), 863–870. 10.1089/jwh.2010.2360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mors O, Perto GP, & Mortensen PB (2011). The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(7 Suppl), 54–57. 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Mors O, & Mortensen PB (2006). New parents and mental disorders: A population-based register study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 296(21), 2582–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk-Olsen T, Maegbaek ML, Johannsen BM, Liu X, Howard LM, di Florio A, … Meltzer-Brody S (2016). Perinatal psychiatric episodes: A population-based study on treatment incidence and prevalence. Translational Psychiatry, 6(10), e919 10.1038/tp.2016.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoye JM, Goebert D, Morland L, Matsu C, & Wright T (2009). PTSD and postpartum mental health in a sample of Caucasian, Asian, and Pacific Islander women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 12(6), 393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB (2011). The Danish Civil Registration System. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(7 Suppl), 22–25. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, Waltoft BL, Agerbo E, McGrath JJ,… Eaton WW (2014). A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(5), 573–581. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud N, Paoloni-Giacobino A, Prada P, Olie E, Salzmann A, Nicastro R,… Malafosse A (2011). Increased methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) in adults with a history of childhood maltreatment: A link with the severity and type of trauma. Translational Psychiatry, 1, e59 10.1038/tp.2011.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Gordon-Smith K, Di Florio A, Forty L, Craddock N, Jones L, & Jones I (2016). Adverse childhood life events and postpartum psychosis in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 205, 69–72. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, &Thygesen LC (2011). Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(7 Suppl), 95–98. 10.1177/1403494811408483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaza A, Garcia-Esteve L, Torres A, Ascaso C, Gelabert E, Luisa Imaz M,… Martin-Santos R (2012). Childhood physical abuse as a common risk factor for depression and thyroid dysfunction in the earlier postpartum. Psychiatry Research, 200(2–3), 329–335. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Records K, & Rice MJ (2009). Lifetime physical and sexual abuse and the risk for depression symptoms in the first 8 months after birth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 30(3), 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson-Blackmore E, Putnam FW, Rubinow DR, Matthieu M, Hunn JE, Putnam KT,… O’Connor TG (2013). Antecedent trauma exposure and risk of depression in the perinatal period. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(10),e942–948. 10.4088/JCP.13m08364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MA, Valentine J, Ahmed SR, Eisenman DP, Sumner LA, Heilemann MV, & Liu H (2010). Intimate partner violence and maternal depression during the perinatal period: A longitudinal investigation of Latinas. Violence Against Women, 16(5), 543–559. 10.1177/1077801210366959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaiger M, Grinberg M, Moser D, Zang JC, Heinrichs M, Hengstler JG, … Kumsta R (2016). Altered stress-induced regulation of genes in monocytes in adults with a history of childhood adversity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(10), 2530–2540. 10.1038/npp.2016.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, Berglund P, Bromet EJ, Brugha TS,… Kessler RC (2009). Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(7), 785–795. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman ME, & Loudon H (2010a). Antenatal reports of pre-pregnancy abuse is associated with symptoms of depression in the postpartum period. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13(5), 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman ME, & Loudon H (2010b). Antenatal reports of pre-pregnancy abuse is associated with symptoms of depression in the postpartum period. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13(5), 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2013). Stata Statistical Software: Release 13 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Lash TL, & Sorensen HT (2011). The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 83 10.1186/1471-2288-11-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viktorin A, Meltzer-Brody S, Kuja-Halkola R, Sullivan PF, Landen M, Lichtenstein P, & Magnusson PK (2016). Heritability of perinatal depression and genetic overlap with nonperinatal depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(2), 158–165. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent J, Hovatta I, Frissa S, Goodwin L, Hotopf M, Hatch SL, … Powell TR (2017). Assessing the contributions of childhood maltreatment subtypes and depression case-control status on telomere length reveals a specific role of physical neglect. Journal of Affective Disorders, 213, 16–22. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson PO, & Goodyer IM (2011). Childhood adversity and allostatic overload of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: A vulnerability model for depressive disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 23(4), 1017–1037. 10.1017/S0954579411000472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]