Abstract

The authors used data from the 1994, 2002, and 2012 General Social Survey (N = 1,450) to examine whether support for divorce has increased among adults aged 50 and older. Consistent with the rise in the gray divorce rate, today’s older adults were more accepting of divorce than their predecessors were two decades ago. Attitudinal change was modest between 1994 and 2002 but accelerated after 2002. The acceleration was primarily due to period rather than cohort change, signaling the role of broader shifts in the meaning of marriage as it has become deinstitutionalized. Older birth cohorts and individuals who were either divorced or remarried were especially likely to hold supportive attitudes toward divorce.

Until recently, divorce among older adults was uncommon. Less than one in ten individuals who got divorced in 1990 was aged 50 or older. Since then, the gray divorce rate, which refers to divorces among adults aged 50 and older, has increased twofold from 5 to 10 divorces per 1,000 marriages (Brown & Lin, 2012; Brown & Wright, 2017). The doubling of the gray divorce rate coupled with the aging of the U.S. population translates into a considerable rise in the share of divorcing individuals who are over age 50. In 2010, one in four individuals who got divorced was aged 50 or older (Brown & Lin, 2012).

This increase in gray divorce purportedly signals growing acceptance of divorce among middle-aged and older adults. Yet, few studies have investigated historical change in divorce attitudes and those that have tended to exclude older adults and are now somewhat dated, failing to capture prevailing attitudes of older adults during the gray divorce revolution period (Martin and Parashar, 2006; Thornton, 1989; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001).

We draw on data from the 1994, 2002, and 2012 General Social Survey (GSS) to examine nearly two decades of change in divorce attitudes of adults aged 50 and older. Given the doubling of the gray divorce rate, we anticipate that older adult attitudes toward divorce have become more favorable over time. Our goal is to examine this assertion from a social change perspective designed to evaluate whether the increase in support reflects cohort replacement or intracohort (i.e., period) change (Firebaugh, 1992, 1997; Ryder, 1965). We assess the relative importance of cohort and period net of factors known to be associated with gray divorce to extrapolate about expected future trends in gray divorce and the implications for policy.

Background

Explaining the Rise in Gray Divorce

The rapid growth in gray divorce reflects a confluence of factors, including some that foretell a shift in older adult attitudes toward divorce. Divorce is commonplace and thus individuals are likely to be more accepting of divorce as either they or the people in their networks experience divorce (Wu & Schimmele, 2007). A primary reason why gray divorce has increased is because a larger proportion of today’s older adults are in remarriages, which are at higher risk of divorce than first marriages (Brown & Lin, 2012). The Baby Boom generation experienced the divorce revolution of the 1970s as young adults and many have since remarried. The gray divorce rate is 2.5 times greater for remarriages than first marriages (Brown & Lin, 2012). Remarriages are less stable in part because they are of shorter duration, on average, and marital duration is negatively associated with divorce. Also, remarriages are more prone to divorce because spouses are typically less homogamous (Sweeney, 2010). Finally, the previously divorced are more willing to divorce again whereas in first marriages some of those who are unhappy are unwilling to call it quits (Uhlenberg & Myers, 1981).

More broadly, the meaning of marriage has shifted such that individuals of all ages hold high expectations for their unions. Today’s individualized marriages are predicated on self-fulfillment, open communication, and flexible roles (Cherlin, 2004). The deinstitutionalization of marriage has coincided with weakened norms of marriage as a lifelong institution (Wu & Schimmele, 2007). Marriages change and evolve over time, and many older couples appear to grow apart, spurring gray divorce (Bair, 2007). During an era of individualized marriage and lengthening life expectancies, couples are simply less willing to remain in empty shell marriages. The rise in wives’ labor force participation makes divorce a realistic option for many women (Amato, 2010; Uhlenberg & Myers, 1981). For prior generations, wives were typically economically dependent on their husbands which may have precluded many divorces. Together, these explanations for the rise in gray divorce suggest more supportive attitudes toward divorce among older adults in recent years, especially among those who have previously divorced.

Prior Research on Divorce Attitudes

These explanations for the rise in gray divorce coupled with the doubling of the gray divorce rate suggest more supportive attitudes toward divorce among older adults in recent years. Yet, few studies have investigated whether and how divorce attitudes have shifted over time and these studies have tended to exclude older adults. For example, Martin and Parashar (2006) tracked divorce attitudes from 1974-2002, but only for women ages 25-39. There was no appreciable variation in divorce attitudes by age net of other factors. Other research uncovered a notable rise in supportive attitudes toward divorce during the 1960s and 1970s, but support remained stable (and high) from the 1980s until about 2000 (Thornton, 1989; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001). Whether or how these trends differed by age group was not investigated. Moreover, these studies are dated and thus do not address the prevailing attitudes for today’s population, regardless of age.

An intergenerational study of mothers and their children revealed that mothers’ supportive attitudes toward divorce when children are involved rose between 1962 and 1980, but did not change appreciably thereafter (the latest time point was 1993). It is unclear whether this initial rise (1962-1980) in favorability was due to within cohort change or if it affected individuals of all ages since only this cohort was followed. Between 1980 and 1993, the young adult offspring of these mothers reported high levels of support for divorce, with favorability increasing modestly over the time period. Daughters more often expressed support for divorce than sons, underscoring a gender gap in divorce attitudes that has been documented in several studies (Kapinus & Flowers, 2008; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001). Asked in 1993 whether they believed couples should not stay married for the sake of the children, about 90% of daughters and 80% of mothers agreed, versus just 70% of sons.

A distinctive pattern emerged for a different measure of divorce attitudes. In 1993 about 60% of mothers supported the notion that “divorce is usually the best solution for couples that can’t seem to work out their marriage problems” versus 41% of daughters and 40% of sons, suggesting greater support for divorce among older than younger adults. Thornton and Young-DeMarco (2001, p. 1019) posited that this pattern could be indicative “more of a life cycle phenomenon for these young adults than a historical trend….these young adults may…become more like their mothers and may see the cost-benefit ratio associated with divorce as more positive than they did” when they were younger. Our study empirically tests this assertion by examining whether attitudinal change reflects within cohort change or inter-cohort differences for a contemporary sample of older adults.

Mothers may be more accepting of divorce than are their offspring because one’s own experience of divorce is highly predictive of attitudes toward divorce. Although divorce attitudes are not associated with subsequent divorce behavior, nearly all women who experienced divorce reported supportive divorce attitudes following their own divorces (Thornton, 1989). This finding is particularly relevant for the current study as the shares of middle-aged and older adults who have experienced divorce is pretty high. In 2009, 41% of individuals aged 50-59, 37% of those aged 60-69, and 22% of those aged 70 and older had ever divorced. By comparison, the proportions ever divorced in 1996 were considerably lower (Kreider & Ellis, 2011). These patterns point to growing acceptance of divorce among middle-aged and older adults.

The Present Study

The current investigation charts a nearly two decade long time trend in attitudes toward divorce among older adults. The rise of gray divorce coupled with the deinstitutionalization of marriage signal that today’s older adults may be more accepting and supportive of divorce as a solution for couples who are unable to work out their marital difficulties. Prior research on attitudes toward divorce is limited in at least three ways. First, research to date has typically focused on younger adults (Martin & Parasher, 2006) or a select group of middle-aged adults, such as mothers (Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001). Second, the existing work is rather dated now and thus does not capture the contemporary population of older adults during the era of rising gray divorce rates (Thornton, 1989; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001). Third, most studies on divorce attitudes have addressed whether divorce laws should be more stringent, not whether divorce itself is a good solution when a marriage does not work out (Kapinus & Flowers, 2008; Martin & Parasher, 2006). The deinstitutionalization of marriage argument aligns with the viewpoint that divorce is a viable option when couples do not get along.

Our study extends prior research by using recent data from 1994, 2002, and 2012 that coincides with the doubling of the gray divorce rate between 1990 and 2010 to appraise older adult attitudes toward the acceptability of divorce as an outcome for marriages that are no longer satisfactory. Our approach relies on a social change perspective which is designed to identify whether any shift in divorce attitudes is due to cohort replacement (also termed cohort succession) or within-cohort (also termed intracohort) change, or if both of these factors are operating (Firebaugh, 1992; Ryder, 1965).

Cohort versus Period Change

Cohort replacement refers to population turnover, which occurs as older birth cohorts die and are replaced by younger cohorts who age into the older adult population. A recent study showed that the growing support among older adults for cohabitation was due to cohort replacement. As the Baby Boomers, the first to cohabit en masse in young adulthood, moved into older adulthood and succeeded generations who lacked prior experience with cohabitation, support for cohabitation among the older adult population soared (Brown & Wright, 2016). These cohort effects reflect stability within the group (i.e., cohort) over time and shared experiences over the life course (e.g., widespread cohabitation as young adults). A similar logic could be applied to divorce attitudes because Baby Boomers were the generation that experienced the apex of the divorce boom, when the divorce rate accelerated in the 1970s and peaked in the early 1980s (Cherlin, 1992). Their divorce experience—whether firsthand or indirectly through their cohort—presumably nudged them to adopt supportive attitudes toward divorce during young adulthood. As cohort replacement unfolds with Baby Boomers moving into older adulthood, we can anticipate broader support for divorce.

Alternatively, within-cohort change indicates that the group’s attitudes are actually changing over time. Intracohort change often reflects alterations in the larger historical context or events that similarly affect all age groups, which are referred to as period effects (Ryder, 1965). When individuals within a given cohort experience a substantial change in their divorce attitudes that signals within-cohort change. Likewise, if support for divorce rises across time within all cohorts, that is evidence of within-cohort change. As the cultural meanings of marriage and divorce have evolved to favor individualized marriages in which personal happiness is paramount and divorce is widespread (Cherlin, 2009), the growth in favorable attitudes toward divorce may reflect this larger sociohistorical context that is permeating all cohorts and thus spurring within cohort change. By this logic, intracohort change is the driving factor in shifts in divorce attitudes among older adults. There is some speculative evidence for this explanation from Thornton and Young-DeMarco (2001), who pointed to a pattern of rising support for divorce with age which they attributed to a life cycle effect.

Sociodemographic Factors and Divorce

In addition to establishing the extent to which cohort replacement versus intracohort change accounts for the shifts in older adult attitudes toward divorce over the past two decades, we also investigate the sociodemographic correlates of supportive divorce attitudes. Our assessment draws on prior research on divorce attitudes as well as the predictors of gray divorce to identify the factors that are likely to be related to older adult support for divorce. The general trend should be in the direction of greater support over time (Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001). Whether older cohorts are more supportive than younger cohorts is uncertain. If cohort replacement is driving attitudinal change, then younger cohorts are more supportive. However, if intracohort change is operating, then it is possible that older cohorts are as likely to express favorable attitudes toward divorce as their younger counterparts.

Marital status is arguably a key determinant of support for divorce. Those who have experienced divorce themselves are nearly uniform in their support for divorce (Thornton, 1989). Also, those in remarriages have a much higher risk of divorce, including gray divorce, than those in first marriages (Amato, 2010; Brown & Lin, 2012; Sweeney, 2010). Thus, we anticipate that older individuals who are either divorced or remarried are more likely to express support for divorce than first married individuals. Those who are widowed may not appreciably differ from the first married. Never married individuals are known to be more supportive than marrieds of divorce (Stokes & Ellison, 2010).

Other demographic characteristics are relevant. Women are more supportive of divorce than are men, on average (Kapinus & Flowers, 2008; Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001). Nonwhites are more likely than Whites to experience gray divorce (Brown & Lin, 2012) and they are more often opposed to more stringent divorce laws (Stokes & Ellison, 2010). Economic resources, including education, employment, and income, are protective against divorce (Amato, 2010) and gray divorce in particular (Brown & Lin, 2012), suggesting lower levels of support for divorce among the economically advantaged. However, there is actually a positive association between resources and liberal family attitudes (Powell, Bolzendahl, Geist, & Steelman, 2010). One study of women’s divorce attitudes reveals that individuals with lower levels of education tend to espouse more permissive attitudes toward divorce (Martin & Parashar, 2006). Finally, social ties could be related to divorce attitudes. For example, religiosity is associated with greater support for strict divorce laws (Stokes & Ellison, 2010). Children also may serve as a barrier to divorce and tend to be related to more conservative divorce attitudes (Martin & Parashar, 2006).

This study expands our limited knowledge about the gray divorce revolution by establishing how supportive of divorce older adults have become over the past two decades. Moreover, it contributes to the literature on divorce attitudes, which is dated and has focused narrowly on younger adults, emphasizing their attitudes about divorce laws. Beyond establishing the trend in older adult support for divorce during an era of rising gray divorce, we also decipher the extent to which this trend is due to cohort (i.e., cohort replacement) versus period (i.e., intracohort) change. And we identify which demographic subgroups of older adults are most likely to express support for divorce. Establishing the trend and correlates of older adult attitudes toward divorce informs our understanding of the potential for future growth in gray divorce.

Method

We used data from the 1994, 2002, and 2012 General Social Survey (GSS) because these rounds included a measure of support for divorce. The GSS, collected by the National Opinion Research Center, is a compilation of cross-sectional survey data dating back to 1972 (Smith, Marsden, Hout, & Kim, 2013). Data were collected via face-to-face interviews from nationally representative samples of adults aged 18 and older. The data were suitable for the current study because a central theme of the GSS has been opinions on social issues and respondents’ views toward divorce have been tapped over the past two decades.

The three GSS rounds contained 7,731 respondents. Only a random sample of respondents was asked their opinion on divorce and thus the 3,811 who were not asked were eliminated. Respondents were removed from the analytic sample if they were missing on the dependent variable (n = 114), birth year (n = 8), or the sample weight (n = 1), leaving 3,797 respondents. Of the remaining respondents, 1,450 were aged 50 or older. We used age 50 as the cut point because gray divorce is a phenomenon confined to those aged 50 and older (Brown & Lin, 2012). An initial descriptive analysis relied on the full sample (aged 18 and older) to establish whether divorce attitudes of individuals aged 50 and older differed from those of people aged 18-49. Missing data were minimal as fewer than 1% of analytic sample cases were missing on the independent measures (the only exception was income, which was missing for 12% of the cases as explained in the next section).

Measures

Dependent variable.

During each of the three years, the GSS asked respondents, “Do you agree or disagree that divorce is usually the best solution when a couple can’t seem to work out their marriage problems?” To track change in levels of support for divorce, divorce attitude was measured as a dichotomous variable with respondents who strongly agreed or agreed coded as 1 and those who neither agreed nor disagreed, disagreed, or strongly disagreed were coded as 0.

Focal independent variables.

Birth cohort was a categorical variable that classified respondents according to their year of birth: 1905-1914, 1915-1924, 1925-1934, 1935-1944, 1945-1954, and 1955-1964 (reference). Period, the year of the survey was included as a series of dichotomous indicators, with each respective year (1994 [reference], 2002, and 2012) coded as 1.

Demographic characteristics.

Marital status was a categorical variable distinguishing among those in a first marriage (reference), remarried, widowed, divorced, and never married. Gender was coded as 1 for man and 0 for woman. Race was coded White = 1 and Nonwhite = 0.

Economic resources.

Education was coded: less than high school, high school education (reference), some college, and college educated. Employment consisted of: full time employment (reference); part time employment; and other work, including the retired, those in school, respondents searching for work, and people temporarily away from work (e.g., for health reasons). Income captured the total family income in the survey year. We constructed income quartiles to accommodate the varied number of response categories across survey years and to account for inflation. The first quartile included earnings under $1,000 to $17,499 in 1994, under $1,000 to $19,999 in 2002, and under $1,000 to $22,499 in 2012. The second quartile was $17,500-$34,999 in 1994, $20,000-$39,999 in 2002, and $22,500-$49,999 in 2012. The third quartile was $35,000-$59,999 in 1994, $40,000-$74,999 in 2002, and from $50,000-$89,999 in 2012. The fourth quartile was at least: $60,000 in 1994, $75,000 in 2002, and $90,000 in 2012. Those with missing data (12% of the sample) on income were coded to the second quartile (the modal category). The multivariate analyses included a missing income flag (1= missing, 0 = not missing). Income was missing at random as none of the other independent variables in the analyses were associated with the log odds of missing income data (logistic regression results not shown).

Social ties.

Children was coded 0 = childless and 1 = one or more children. Attendance at religious services ranged from 0 = never to 8 = more than once a week.

Analytic Strategy

We began by documenting the trend between 1994 and 2012 in older adults’ attitudes toward divorce, comparing it to the attitudinal pattern for younger adults aged 18-49. Then, we gauged the relative contributions of period and cohort change for divorce attitude shifts between 1994-2002 and 2002-2012 by constructing a period-by-cohort table for older adults. This social change perspective was explicated by Firebaugh (1992, 1997) and also used by Norpoth (1987). Next, we tracked levels of support for divorce across the three survey years by demographic characteristics, economic resources, and social ties to evaluate how divorce attitudes changed over time for these subgroups. Finally, a multivariate logistic regression model was estimated for the full sample of older adults to determine how much of the change in divorce attitudes was due to cohort replacement (i.e., a cohort effect) versus intracohort change (i.e., a period effect). Consistent with prior research, this approach relied on a two-factor model that assumed age effects were null given the average age of the population changed little over the 18-year time period, (Brown & Wright, 2016; Alwin & McCammon, 2003; Glenn, 2003). Indeed, the mean age of the samples remained largely stable at 64.1 in 1994, 62.7 in 2002, and 63.4 in 2012. Our two mechanisms of interest were population change arising from the changing cohort composition (cohort replacement) and the role of period factors that contribute to change within cohorts (intracohort change). Analyses were conducted using the svy procedure in Stata to correct for the GSS’s complex sample design.

Results

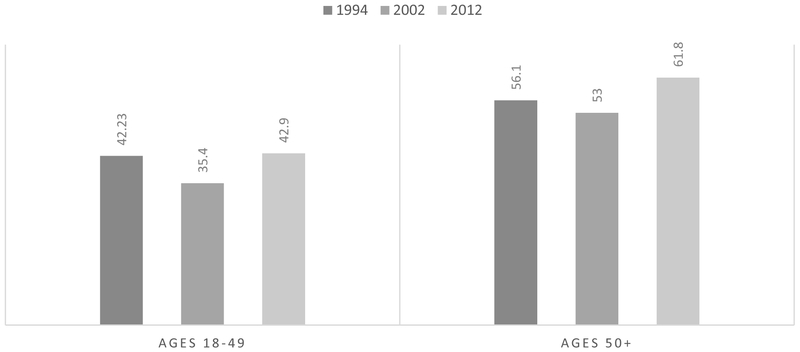

Across the 18 year time period, adults aged 50 and older more often expressed supportive attitudes toward divorce than did their counterparts aged 18-49, as shown in Figure 1. The gap between the two age groups widened from about 14 to 19 percentage points between 1994 and 2012. In 1994, about 42% of 18-49 year olds and 56% of those aged 50 and older supported divorce. By 2012, the share expressing favorable attitudes was substantively unchanged for 18-49 year olds at 43% but had risen to 62% for older adults. The age differentials in support for divorce were statistically significant at all three time points.

FIGURE 1.

SUPPORTIVE DIVORCE ATTITUDES BY AGE GROUP, 1994-2012

Note: Support for divorce is significantly higher for ages 50+ than ages 18-49 at all three time points, p < .001.

Table 1 depicts within cohort and total change in the percentages supporting divorce by cohort and period. The “%” columns represent the percentages of the cohort that expressed support for divorce. The “N” columns are the total numbers of respondents in the cohorts at a given time point. The change columns indicate the differences between values for 1994-2002 and 2002-2012, respectively. The row labeled “Total” reports the overall average percentage of respondents supporting divorce at each time point. Finally, the average within-cohort change row is a weighted average of the summed changes (1994-2002 or 2002-2012) across the cohorts. The rows in the table indicate that within cohort change during 1994-2002 was small, averaging only about 1.5 percentage points across the cohorts. Total change was a bit larger at −3 percentage points, signaling modest intercohort change, although the patterns within cohorts varied from - 7.9 to 16.4, suggesting greater heterogeneity during the 1994-2002 period. In contrast, within cohort change played a sizeable role during 2002-2012, when the shift in attitudes averaged 16 percentage points. Total change was lower at 9 percentage points, indicating that attitudinal shifts were mainly due to intracohort change. Older cohorts became increasingly favorable towards divorce during the 2002-2012 period. This pattern was evident for those cohorts born 1925-34, 1935-44, and 1944-54 as support grew from about 50% in 2002 to 66-77% in 2012. The oldest cohort (1915-24) remained quite supportive at about 75%, which was comparable to its support level in 2002 (73%). On balance, it seems that intracohort change was driving the recent growth in support for divorce among older adults, primarily during the 2002-2012 period.

Table 1.

Within-Cohort and Total Change in the Percentages of Older Adults with Supportive Divorce Attitudes, 1994-2012

| 1994 | 2002 | 2012 | Change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | % | N | % | N | % | N | 1994-2002 | 2002-2012 |

| 1905-1914 | 68.3 | 46 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 1915-1924 | 56.2 | 130 | 72.6 | 35 | 75.0 | 12 | 16.4 | 2.4 |

| 1925-1934 | 52.6 | 137 | 56.0 | 100 | 77.2 | 59 | 3.4 | 21.2 |

| 1935-1944 | 56.2 | 180 | 48.3 | 132 | 64.1 | 125 | −7.9 | 15.8 |

| 1945-1954 | --- | --- | 51.0 | 140 | 66.6 | 171 | --- | 15.6 |

| 1955-1964 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 52.4 | 178 | --- | --- |

| Total (all cohorts) | 56.3 | 493 | 53.2 | 407 | 62.7 | 545 | −3.1 | 9.1 |

| Average within-cohort change (weighted by size) | 1.5 | 16.0 | ||||||

Note: The calculations in this table exclude 5 cases in the 1905-1914 cohort for 2002 due to inadequate sample size. Percentages are weighted to correct for the complex sampling design of the GSS.

Table 2 illustrates how older adult divorce attitudes have shifted over time for various subgroups. Support for divorce varied by marital status with never marrieds at the low end and remarrieds at the high end. The attitudes of first marrieds and widoweds were stable, hovering around 52% and 63%, respectively. In both 1994 and 2012, about 44% of never-married older adults reported favorable attitudes toward divorce. Older divorced individuals experienced a nonsignificant increase in their acceptance of divorce, which grew from 62% to 73%. Support among remarried older adults rose significantly from 63% to 78% over this period. In 1994, about 56% of older women and men expressed support for divorce. By 2012, the level of support among women was largely unchanged at 58% whereas men’s support rose significantly to 66%. Support among White older adults grew significantly from 54% in 1994 to 63% in 2012 whereas Nonwhites exhibited a nonsignificant decrease in their support (from 68% to 54%).

Table 2.

Weighted Percentages of Older Adults Who Support Divorce by Year (n=1,450)

| Variable | 1994 (n=493) |

2002 (n=412) |

2012 (n=545) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Marital Status | |||

| First married | 52.3 | 48.6 | 52.3 |

| Remarried | 62.8 | 56.9 | 78.3 |

| Divorced | 61.9 | 55.3 | 73.0 |

| Widowed | 62.6 | 61.0 | 63.9 |

| Never married | 44.1 | 48.7 | 44.0 |

| Gender | |||

| Women | 56.3 | 47.3 | 58.0 |

| Men | 55.7 | 60.9 | 65.8 |

| Race and Ethnicity | |||

| White | 54.4 | 52.0 | 63.4 |

| Nonwhite | 67.6 | 59.6 | 53.6 |

| Economic Resources | |||

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 63.4 | 71.3 | 78.4 |

| High school graduate | 53.7 | 49.4 | 66.7 |

| Some college | 63.8 | 46.5 | 53.5 |

| College | 46.3 | 52.4 | 54.0 |

| Employment | |||

| Full time employment | 53.8 | 56.4 | 59.9 |

| Part time employment | 48.4 | 62.7 | 45.2 |

| Other work | 58.6 | 49.1 | 66.1 |

| Income | |||

| Quartile 1 | 56.2 | 61.0 | 65.8 |

| Quartile 2 | 61.0 | 52.0 | 58.4 |

| Quartile 3 | 46.9 | 49.3 | 66.1 |

| Quartile 4 | 55.6 | 50.3 | 60.4 |

| Social Ties | |||

| Religious attendance (median = 4) | 78.5 | 85.2 | 53.5 |

| Children | 57.0 | 52.9 | 61.3 |

| No children | 44.9 | 54.0 | 64.0 |

Analyses are weighted to correct for the complex sampling design of the GSS. Bolded coefficients are significantly different from the 2012 values, p < 0.05.

Variation in support for divorce was evident across some of the economic indicators, but consistent patterns were less apparent. The gains between 1994 and 2012 for those with either less than a high school diploma or only a high school diploma were large and statistically significant, rising from 63% to 78% and 54% to 67%, respectively. The college educated experienced a nonsignificant rise from 46% to 54%. Among those with some college, there was a nonsignificant decline in support, from 64% to 54%. Support grew modestly among the full time employed, rising from 54% to 60%. Likewise, those engaged in other work witnessed a significant increase from 59% to 66%. Support dropped slightly (not significant) for the part-time employed, from 48% in 1994 to 45% in 2012. Across the income scale, the variation in support narrowed over time such that by 2012, the range was from 58% to 66%, suggesting few differences by income group (although quartile 3 experienced significant change).

Social ties were related to divorce attitudes among older adults. Those who reported the median level of religious service attendance (i.e., several times a year) exhibited a significant shrinking of support for divorce, falling from 79% to 54% between 1994 and 2012. In the past, older adults with children more often supported divorce than their childless counterparts (57% versus 45%), but the pattern reversed such that in 2012 the childless were slightly more supportive at 64% than were those with children at 61%. The change over time was only significant for those without children, not with children.

Consistent with the period-by-cohort table (Table 1), the multivariate logistic regression model depicted in Table 3 showed that both cohort and period were related to the likelihood of reporting supportive attitudes toward divorce among older adults. Older cohorts were more likely to be supportive than younger cohorts. Notably, early Baby Boomers (born 1945-54) had higher odds of supportive attitudes than later Baby Boomers (born 1955-64). Although not all of the cohorts significantly differed from one another (significant differences are denoted using superscripts in Table 3), the overall pattern was robust to alternative specifications (results not shown), including a linear measure of birth year (which was negatively associated with support for divorce at the p < .001 level). In addition to these cohort effects, there was also evidence for period effects. The odds of supporting divorce in 2012 were nearly twice as high as they were in 1994. As expected, the likelihood of expressing supportive divorce attitudes varied by marital status with remarried and divorced individuals more likely to report favorable attitudes than those in a first marriage. Few other factors were associated with older adult divorce attitudes. Individuals who did not complete high school were more likely to hold favorable attitudes toward divorce than their counterparts who earned a high school diploma. Those with a college degree were marginally (p < .10) less likely to support divorce than individuals who completed high school. More frequent religious service attendance was negatively associated with the likelihood of reporting favorable attitudes toward divorce.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Model Predicting Supportive Divorce Attitudes (N=1,450)

| Odds Ratio | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort | ||

| 1905-1914 | 3.86**a | 1.53-9.77 |

| 1915-1924 | 2.90**a | 1.47-5.71 |

| 1925-1934 | 2.58** | 1.45-4.59 |

| 1935-1944 | 2.05** | 1.31-3.20 |

| 1945-1954 | 1.79**b | 1.18-2.71 |

| 1955-1964 (ref) | ||

| Year | ||

| 1994 (ref) | ||

| 2002 | 1.02 | 0.74 – 1.39 |

| 2012 | 1.94** | 1.30 – 2.90 |

| Marital Status | ||

| First married (ref) | ||

| Remarried | 1.86** | 1.28 – 2.72 |

| Divorced | 1.65** | 1.17 – 2.32 |

| Widowed | 1.42+ | 0.99 – 2.03 |

| Never married | 0.65 | 0.38 – 1.11 |

| Gender | ||

| Women (ref) | ||

| Men | 1.20 | 0.92 – 1.57 |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||

| White | 0.86 | 0.61 – 1.22 |

| Nonwhite (ref) | ||

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 1.67** | 1.17 – 2.38 |

| High school grad (ref) | ||

| Some college | 0.83 | 0.59 – 1.17 |

| College | 0.76+ | 0.55 – 1.05 |

| Employment | ||

| Full time (ref) | ||

| Part time | 0.75 | 0.47 – 1.19 |

| Other work | 0.85 | 0.63 – 1.16 |

| Income | ||

| Quartile 1 (ref) | ||

| Quartile 2 | 1.10 | 0.76 – 1.59 |

| Quartile 3 | 1.13 | 0.74 – 1.72 |

| Quartile 4 | 1.36 | 0.87 – 2.11 |

| Income Flag | 0.98 | 0.62 – 1.54 |

| Relig. attendance | 0.90*** | 0.86 – 0.94 |

| Children | 0.85 | 0.57 – 1.26 |

| No children (ref) | ||

| Constant | 0.83 | 0.38 – 1.82 |

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Significantly different from 1945-1954, p < .10;

Significantly different from 1905-1914, p < .10

Analyses are weighted to correct for the complex sampling design of the GSS.

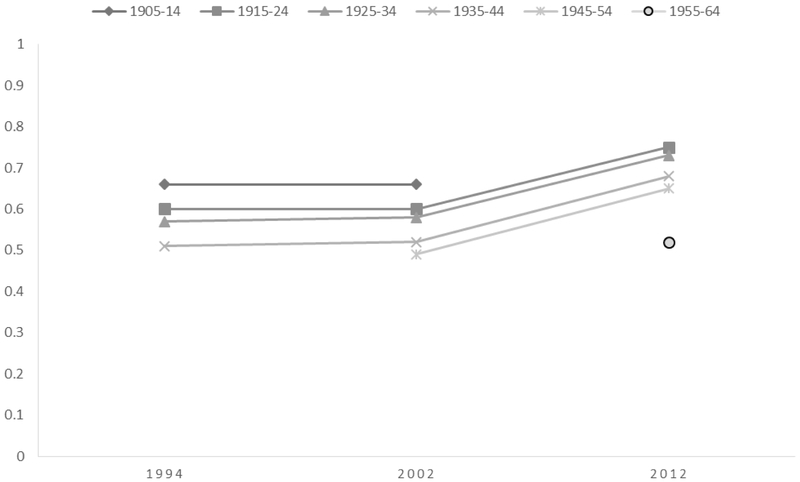

Figure 2 shows these cohort and period effects by graphing the predicted probabilities of divorce support for each ten year birth cohort at the three time points. There was a modest cohort replacement effect operating during the 1994-2002 period as indicated by the essentially flat lines (i.e., negligible period effects) that are stacked such that older cohorts were more likely to be favorable towards divorce. The upward slopes of the lines for the 2002-2012 period are consistent with period effects or intracohort change. Evidence of cohort replacement is also apparent because the array of the birth cohort slopes persists.

FIGURE 2.

PREDICTED PROBABILITY OF DIVORCE SUPPORT BY COHORT

Note: Predicted probabilities are derived from the model shown in Table 3.

Additional analyses were conducted to test whether the effects of cohort differed across period, but no significant interactions emerged. Likewise, the covariates operated similarly on divorce attitudes by gender and marital status.

Discussion

Divorce is now common across the adult life course, and actually on the rise among older adults (Kennedy & Ruggles, 2014). Consistent with our expectations, older adult support for divorce has increased. In 2012, nearly two-thirds agreed that divorce was the best solution for couples who could not work out their problems whereas support hovered at 56% in 1994. Older adults were more supportive of divorce than were younger adults, and this gap grew over time.

Drawing on a social change perspective (Firebaugh, 1992, 1997; Ryder, 1987), we assessed the extent to which this change was due to cohort replacement versus intracohort change. Initially, the growth in supportive divorce attitudes was quite modest in magnitude and was driven primarily by cohort replacement. During the more recent period, intracohort change was the main reason why there was an increase in favorable divorce attitudes. The 2002-2012 period was marked by a steep ascent in support across all ten year birth cohorts, signaling broader period-based change in attitudes that was consistent with the deinstitutionalization of marriage and the run-up in gray divorce. In fact, the groups that experienced pronounced increases in support were the divorced and remarried, who themselves might have experienced a gray divorce (unfortunately, this information cannot be ascertained from the GSS, which does not include marital history measures). Although most of these individuals probably have not had a gray divorce, this possibility certainly became more likely over the 18 year time period.

Our findings revealed that support for divorce was highest among the oldest cohorts. This pattern aligned with that from prior research on childbearing-aged adults showing that attitudes toward divorce become more favorable with age (Daugherty & Copen, 2016). It may seem counterintuitive because the rate of divorce remains lower for older than younger adults, but this association is consistent with the recent growth in the gray divorce rate. As older adults either experience divorce themselves or observe others in their social networks get divorced, their attitudes toward divorce could become more accepting (Uhlenberg & Myers, 1981; Wu & Schimmele, 2007).

The rise in divorce support since 2002 indicates that a growing share of older adults views divorce as an acceptable solution for couples who are unable to work out their problems, which coincides with the emergence of individualized marriage (Cherlin, 2009) and the demise of the norm of lifelong marriage (Wu & Schimmele, 2007). These forces may have been emergent during the earlier period of 1994-2002, but then intensified and became widespread during the later period of 2002-2012. Contemporary shifts in the meaning of marriage and divorce are often described as altering the family behaviors of young adults, but our study suggests that these shifts have implications for older adults, too. The retreat from marriage is evident across the life course; one in three Baby Boomers is unmarried (Lin & Brown, 2012). Marriage is less obligatory now for all age groups, and the results uncovered here indicate sweeping change for older adults who are most likely to express support for divorce as a solution for couples who cannot resolve their marital problems. Unlike their younger counterparts, older adults are embracing divorce as indicated both by the doubling of the gray divorce rate and the rise in supportive attitudes toward divorce.

The rise in gray divorce coupled with the increasing acceptance of divorce among older adults signals the mounting salience of divorce during the second half of life. The policy implications are uncertain, although we can expect a growing number of older adults will experience divorce after age 50 even if the gray divorce rate remains stable, reflecting the aging of the U.S. population and underscoring the urgency of new research on the consequences of gray divorce for individuals, their families, and society (Brown & Lin, 2012; Brown & Wright, 2017). Moreover, little is known about whether gray divorce is trending upward in other countries. Only a few scholars in Europe (Bildtgard & Oberg, 2019; Perrig-Chiello, Hutchison, & Morselli, 2015) have examined later life divorce. Cherlin (2017) recently noted that the global demographics of divorce are changing and we posit that these shifts likely encompass cross-national variation in levels and acceptance of divorce in the second half of life. An important direction for future research is to examine international patterns of gray divorce.

This study breaks new ground by tracking the divorce attitudes of older adults, but it nonetheless has some limitations. First, the sample size is adequate although the oldest (1905-1914) birth cohort is small (n = 51), potentially undermining statistical power and impeding our ability to accurately detect significant differences across groups. Second, information about respondents’ divorce histories as well as whether close relatives or friends have experienced divorce are not available. This information might be predictive of an individual’s attitudes toward divorce. Third, the social change approach emphasized period versus cohort effects, assuming null age effects given the stable age range across the three time periods. This approach is consistent with prior research (e.g., Brown & Wright, 2016; Alwin & McCammon, 2003; Glenn, 2003), but we acknowledge that it is possible the effects we attribute to cohort could be driven in part by age. Age is positively associated with increased wisdom and corresponding flexibility (Gluck, 2017; Owens et al., 2016), which could account for the growing acceptance of divorce among older adults as they age. We estimated our models using age in lieu of cohort and found comparable results, that is, age was positively associated with support for divorce (results not shown). This is equivalent to using birth year, a linear measure of cohort.

In recent years, older adults have become much more accepting of divorce. This shift primarily reflects within cohort change as period factors such as the shifting meaning of marriage have contributed to increasing acceptance of divorce across all cohorts of older adults. The rapid increase in support for divorce has unfolded within the larger context of the doubling of the gray divorce rate and the rise of individualized marriage. Clearly, older adults are open to divorce. The share of adults who support divorce is highest among those aged 50 and older and this differential has only widened in recent years, which aligns with the ongoing gray divorce revolution and foretells a sustained upward trend in divorce among older adults.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank I-Fen Lin for her valuable feedback on earlier versions of the paper. The research for this paper was supported in part by the Center for Family and Demographic Research, Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD050959).

Contributor Information

Susan L. Brown, Department of Sociology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH 43403, (419) 372-9521, brownsl@bgsu.edu

Matthew R. Wright, Department of Criminology, Sociology, and Geography, Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, AR 72467, (870) 972-3276, mawright@astate.edu

References

- Alwin DF, & McCammon RJ (2003). Generations, cohorts, and social change In Mortimer JT & Shanahan MJ (Eds.), Handbook of the lifecourse (pp. 23–49). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 650–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bair D (2007). Calling it quits: Late life divorce and starting over. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Bildtgard T, & Oberg P (2019). Intimacy and ageing: New relationships in later life. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Lin I-F (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 731–741. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Wright MR (2016). Older adults’ attitudes toward cohabitation: Two decades of change. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 755–764. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Wright MR (2017). Marriage, cohabitation, and divorce in later life. Innovation in Aging, 1(2), 1–11. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igx015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A (1992). Marriage, divorce, remarriage. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 848–861. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00058.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ (2009). The marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and the family in America today. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ (2017). Separation, divorce, repartnering, and remarriage around the world. Demographic Research, 38, 1275–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty J, & Copen C (2016). Trends in attitudes about marriage, childbearing, and sexual behavior: United States, 2002, 2006-2010, and 2011-2013. National Health Statistics Reports, 92, 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firebaugh G (1997). Analyzing repeated surveys (No. 115). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Firebaugh G (1992). Where does social change come from? Population Research and Policy Review, 11, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00136392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn ND (2003). Distinguishing age, period, and cohort effects In Mortimer JT & Shanahan MJ (Eds.), Handbook of the lifecourse (pp. 465–476). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gluck J (2018). Measuring wisdom: Existing approaches, continuing challenges, and new developments. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73, 1393–1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapinus CA, & Flowers DR (2008). An examination of gender differences in attitudes toward divorce. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 49, 239–257. doi: 10.1080/10502550802222469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, & Ruggles S (2014). Breaking up is hard to count: The rise of divorce in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography, 51, 587–598. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0270-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, & Ellis R (2011). Number, timing, and duration of marriages and divorces: 2009 Current Population Reports, P70–125, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lin IF, & Brown SL (2012). Unmarried boomers confront old age: A national portrait. The Gerontologist, 52(2), 153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis R, & Verdery AM (2017). Older adults without close kin the United States. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72, 688–693. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP, & Parashar S (2006). Women’s changing attitudes toward divorce, 1974–2002: Evidence for an educational crossover. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 29–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00231.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norpoth H (1987). Under way and here to stay: Party realignment in the 1980s? Public Opinion Quarterly, 51, 376–391. doi: 10.1086/269042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JE, Menard M, Plews-Ogan M, Calhoun LG, & Ardelt M (2016). Stories of growth and wisdom: a mixed-methods study of people living well with pain. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 5, 16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrig-Chiello P, Hutchison S, & Morselli D (2015). Patterns of psychological adaptation to divorce after a long-term marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 32, 386–405. 10.1177/0265407514533769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B, Bolzehdahl C, Geist C, & Steelman LC (2010). Counted out: Same-sex relations and Americans ‘ definitions of family. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder NB (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30, 843–861. doi: 10.2307/2090964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Marsden P, Hout M, & Kim J (2013). General Social Surveys, 1972-2012 [machine-readable data file] Principal Investigator, Tom W. Smith; Co-Principal Investigator, Peter V. Marsden; Co-Principal Investigator, Michael Hout; Sponsored by National Science Foundation. (NORC ed.) Chicago: National Opinion Research Center [producer]; Storrs, CT: The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut [distributor]. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes CE, & Ellison CG (2010). Religion and attitudes toward divorce laws among U.S. adults. Journal of Family Issues, 31, 1279–1304. doi: 10.1177/0192513X10363887 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM (2010). Remarriage and stepfamilies: Strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 667–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00724.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A (1989). Changing attitudes toward family issues in the United States. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51, 873–893. doi: 10.2307/353202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, & Young-DeMarco L (2001). Four decades of trends in attitudes toward family issues in the United States: The 1960s through the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1009–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01009.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenberg P, & Myers MAP (1981). Divorce and the elderly. The Gerontologist, 21, 276–282. doi: 10.1093/geront/21.3.276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, & Schimmele C (2007). Uncoupling in late life. Generations, 31, 41–46. [Google Scholar]