Abstract

This paper studies the relationship between the “big five” personality traits and political ideology in a large US representative sample (N=14,672). In line with research in political psychology, “openness to experience” is found to predict liberal ideology and “conscientiousness” predicts conservative ideology. The availability of family clusters in the data is leveraged to show that these results are robust to a sibling fixed-effects specification. The way that personality might interact with environmental influences in the development of ideology is also explored. A variety of childhood experiences are studied that may have a differential effect on political ideology based on a respondent's personality profile. Childhood trauma is found to interact with “openness” in predicting ideology and this complex relationship is investigated using mediation analysis. These findings provide new evidence for the idea that differences in political ideology are deeply intertwined with variation in the nature and nurture of individual personalities.

1 Introduction

Research in political psychology has come to detail the powerful influence that personality traits exert on political ideology and behavior (Jost 2006, Block & Block 2006, Mondak & Halperin 2008, Sibley & Duckitt 2008, Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Dowling & Ha 2010, Mondak, Hibbing, Canache, Seligson & Anderson 2010, Verhulst, Hatemi & Martin 2010). The prominence of the “big five” personality traits model in the psychology literature has made it easier for other disciplines, such as political science, to adopt these measures of personality into applied research. Because of their predictive power and relative stability throughout the course of life, personality traits merit their inclusion into models of political ideology and allow us to better account for variance in ideology. Besides correctly distinguishing between correlation and causation (Verhulst, Eaves & Hatemi 2012), the challenge for political scientists thus far has been to collect data from samples which also include meaningful covariates for the study of political ideology and to collect samples large enough to probe beyond direct effects of personality on ideology to explore the way that personality might interact with known environmental influences in the development of ideology.

Making use of the Add Health Wave IV data (Harris, Halpern, Whitsel, Hussey, Tabor, Entzel & Udry 2009), which now includes measures for the big five traits, this paper performs large-N analyses on the influence of personality on political ideology. Corroborating prior findings in political psychology, it is found that “openness to experience” significantly predicts a higher self-reported score on liberal ideology and that “conscientiousness” significantly predicts a more conservative ideology.

The scope of the data enables this research to make two additional contributions to the study of political ideology. First, leveraging the family sampling structure in Add Health, the relationship between personality traits and political ideology is explored in a new and more robust way. The introduction of sibling fixed-effects leads us to discard the earlier results on “extraversion” and “neuroticism” obtained using standard regression analysis, and provides a new level of robustness to the effects of “openness” and “conscientiousness” on political ideology. Second, the longitudinal nature of the Add Health data allows for exploring the effects of various childhood exposures to better understand social and environmental contributions to the development of ideology. Work in psychology, political science, and behavior genetics suggests that factors related to childhood experience have profound implications on behaviors and attitudes later in life (Erikson 1968, Erikson 1963, Carver & Scheier 2000, Caspi, McClay, Moffitt, Mill, Martin, Craig, Taylor & Poulton 2002, Moran, Coffey, Chanen, Mann, Carlin & Patton 2011) that, in turn, could be related to political orientations (Campbell 2006). Childhood experience may have a direct impact on adult political outcomes (Settle, Bond & Levitt 2011), but may also interact with a person's traits to influence their ideology later in life (Settle, Dawes, Christakis & Fowler 2010). This paper interacts personality traits with a variety of childhood experiences and finds that childhood trauma moderates the influence of the “openness to experience” trait on political ideology.

It is increasingly understood that variation in political ideology is a result of both the social and environmental experiences throughout the course of life and the predispositions with which individuals are endowed from the start of life (Alford, Funk & Hibbing 2005, Hatemi, Hibbing, Medland, Keller, Alford, Martin & Eaves 2010, Hatemi, Gillespie, Eaves, Maher, Webb, Heath, Medland, Smyth, Beeby, Gordon, Montgomery, Zhu, Byrne & Martin 2011). As such, a comprehensive understanding of the development of political ideology requires the consideration of both of these fundamental influences.

2 Personality and Ideology

The “big five” traits model represents five dimensions or clusters of personality that jointly describe human personality (Digman 1990, McCrae & Costa 1999). These five major traits are (i) openness to experience; (ii) conscientiousness; (iii) extraversion; (iv) agreeableness; and (v) neuroticism. Openness relates to open-mindedness and the cognitive complexity associated with curiosity, imagination, and high-risk behavior. Conscientiousness relates to responsibility, order and organization, dutifulness, and the self control required to possibly satisfy a need for achievement. Agreeableness is associated with empathy and a willingness to compromise in order to foster cooperative interactions. Extraversion is related to being sociable, lively, and proactively asserting oneself. Neuroticism is viewed as emotional instability and a tendency to experience negative emotions. A comprehensive overview of the big five personality traits is developed elsewhere (Digman 1990, McCrae & Costa 1999, Mondak & Halperin 2008, Almlund, Duckworth, Heckman & Kautz 2011). Over time, the replication across myriad samples worldwide has led to the broad acceptance that personality is defined along the lines of these five core traits and the “big five” model emerged as a dominant model in the psychology literature (Mondak & Halperin 2008).

Several important early treaties in political science touched upon the influence of personality on political behaviors (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson & Sanford 1950, McClosky 1958, Campbell, Converse, Miller & Stokes 1960) and a handful more addressed the role of personality in political socialization (Froman 1961, Greenstein 1965) but the research agenda never gained significant momentum. While the role of personality traits on political behavior of the masses was essentially ignored for much of the second half of the 20th century, the study of the effects of personality thrived in other disciplines. The body of work written by John Jost and colleagues suggests that there is a core element to political ideology that is rooted in a person's underlying predispositions (Jost 2006), and that motivated social cognition reinforces these tendencies. A variety of psychological variables related to threat and uncertainty have been found to be related to political ideology (Jost, Glaser, Kruglanksi & Sulloway 2003, Jost, Napier, Thorisdottir, Gosling, Palfai & Ostafin 2007).

Recent developments and analyses of the role of personality in political behavior took place in political psychology (Heil, Kossowska & Mervielde 2000, Schoen & Schumann 2007, Carney, Jost, Gosling & Potter 2008) with a meta-analysis by Sibley & Duckitt (2008) showing that right-wing authoritarianism is correlated with “conscientiousness” and with low “openness”, whereas social dominance orientation is correlated with low “agreeableness” and low “openness”. The “big five” traits have now also received full consideration by political scientists (Mondak & Halperin 2008, Gerber et al. 2010, Mondak et al. 2010). These recent studies introduce the big five traits, suggest a framework for the study of personality and political behavior across economic and social policy domains, and investigate the structure of the relationship between genes, personality, and political outcomes. The most powerful and consistent result to come out of this literature is that individuals that score high on the “openness” trait are more likely to report a liberal ideology, whereas a high score on the “conscientiousness” trait is associated with more conservative political attitudes (Gerber et al. 2010).

The literature also suggests that, in addition to the direct effects of personality on ideology, it is important to consider the ways in which personality might affect the way we interpret life experiences, and thus the way that experience may have a differential effect on political ideology based on a respondent's personality profile. For example, Mondak et al. (2010) explore the role of political network size interacting with personality to affect exposure to disagreement, finding that extraversion positively interacts with network size to increase cross cutting exposures while the opposite is true for agreeableness. Digging even further into innate biological differences that precede personality, Settle et al. (2010) find that the number of friends in childhood is associated with increased liberalism as a young adult, but only for those respondents that have one or more alleles of a gene variant associated with openness to experience, the long allele of DRD4.

Literature from psychology, sociology, behavioral genetics, and political science suggests a multitude of other contextual effects that may act to mediate or moderate the effects of personality on political ideology. As Shanahan & Hofer (2005) note in reference to gene and environmental interactions, the environment can serve both to trigger or suppress innate tendencies. Notably, scholars have dedicated a considerable amount of attention to the influence of childhood experience (Erikson 1968, Erikson 1963, Carver & Scheier 2000, Sameroff, Lewis & Miller 2000). This paper takes advantage of the longitudinal nature of the Add Health data to explore the effects of various childhood exposures to better understand social and environmental contributions to the development of ideology. Childhood experience has a direct impact on adult political outcomes (Settle, Bond & Levitt 2011, Campbell 2006), but may also interact with a person's personality traits to influence their ideology later in life. Seminal work in behavior genetics on the influence of child maltreatment and life stress suggests that childhood trauma has the ability to interact with the innate component of personality and to leave lasting psychological and behavioral imprints (Caspi et al. 2002, Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig, Harrington, McClay, Mill, Martin, Braithwaite & Poulton 2003). In addition to measures of trauma, the data also capture other important aspects of the childhood experience including number of friends and the perception of feeling safe in one's school or neighborhood. In a recent contribution to political science, Campbell (2006) shows the importance of an adolescent's environment—schools and communities—for adult political behavior later in life. While this research does not propose an ex-ante hypothesis about the direction of a possible effect for the analyses involving childhood experience, it is anticipated that the lasting psychological and behavioral consequences of adolescence may have a significant influence on ideology and may potentially interact with personality traits to influence ideology.

3 Data and Analysis

3.1 Sample

Data is from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) (Harris et al. 2009). Add Health was started in 1994 in order to explore the health-related behavior of adolescents in grades 7 through 12. By now, 4 waves of data collection have taken place and participating subjects were around 30 years old in Wave IV (2008). The first wave of the Add Health study (1994–1995) selected 80 high schools from a sampling frame of 26,666. The schools were selected based on their size, school type, census region, level of urbanization, and percent of the population that was white. Participating high schools were asked to identify junior high or middle schools that served as feeder schools to their school. This resulted in the participation of 145 middle, junior high, and high schools. From those schools, 90,118 students completed a 45-minute questionnaire and each school was asked to complete at least one School Administrator questionnaire. This process generated descriptive information about each student, the educational setting, and the environment of the school. From these respondents, a core random sample of 12,105 adolescents in grades 7-12 were drawn plus several over-samples, totaling more than 27,000 adolescents. These students and their parents were administered in-home surveys in the first wave. Wave II (1996) was comprised of another set of in-home interviews of more than 14,738 students from the Wave I sample and a follow-up telephone survey of the school administrators. Wave III (2001–2002) consisted of an in-home interview of 15,170 Wave I participants. Finally, Wave IV (2008) consisted of an in-home interview of 15,701 Wave I participants. The result of this sampling design is that Add Health is a nationally representative study. Women make up 49% of the study's participants, Hispanics 12.2%, Blacks 16.0%, Asians 3.3%, and Native Americans 2.2%. Participants in Add Health also represent all regions of the United States.

In Wave IV only, subjects were asked a battery of questions to gauge their position on the “big five” personality traits. These traits were assessed using the 20-item IPIP survey developed by Donnellan, Oswald, Baird & Lucas (2006) building on the work of Costa & McCrae (1988). The specific questions and their descriptive statistics are given in Tables 7–8 in the Appendix. Participants were also asked in Wave IV about their political ideology on the general conservative-liberal scale. In the first three waves of the study, respondents were asked questions about a variety of experiences related to childhood experiences and contexts. Alternative answers to these questions, such as “refused” or “don't know,” were discarded for the purpose of this study (typically less than 1% of interviewees gave such a response). Details on these questions are also available in the Appendix.

Table 7.

Moderated mediation test: Liberal ideology (DV), Childhood trauma (IV + moderator), Openness (mediator). Normal theory estimation using the bootstrapping method (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes 2007).

| Moderated Mediation Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| “Openness to experience” | |||

| Moderator | Conditional indirect effect | Bootstrap SE | P-value |

| “Childhood trauma” | |||

| Mean - 1 Std. dev. | 0.010 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Mean | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Mean + 1 Std. dev. | 0.013 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Bootstrapped standard errors (SE) and P-values are also presented. Number of observations is 14,369. Analyses are bootstrapped (2,000 replications) to generate percentile and bias-corrected confidence intervals.

Table 8.

Moderated mediation test: Liberal ideology (DV), Openness (IV + moderator), Childhood trauma (mediator). Normal theory estimation using the bootstrapping method (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes 2007).

| Moderated Mediation Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| “Childhood trauma” | |||

| Moderator | Conditional indirect effect | Bootstrap SE | P-value |

| “Openness to experience” | |||

| Mean - 1 Std. dev. | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.131 |

| Mean | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.151 |

| Mean + 1 Std. dev. | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.178 |

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Bootstrapped standard errors (SE) and P-values are also presented. Number of observations is 14,369. Analyses are bootstrapped (2,000 replications) to generate percentile and bias-corrected confidence intervals.

In Wave I of the Add Health study, researchers screened for sibling pairs including all adolescents that were identified as twin pairs, full-siblings, half-siblings, or unrelated siblings raised together. The sibling-pairs sample is similar in demographic composition to the full Add Health sample (Jacobson & Rowe 1998). Consequently, all regression models cluster the standard errors of the estimates in order to better account for the fact that a subset of the observations are not independent. The structure of this data also allows for the comparison of siblings while holding the family environment constant, which reduces potential omitted variable bias in studying the relationship between personality, childhood context, and political ideology as an adult.

3.2 Analysis

The analysis proceeds in four parts. First, analyses are conducted on the direct effects of personality on political ideology. Previous work provides guidance in terms of the expected direction and significance of the effects of each trait on ideology but the large sample size used here and the available sibling clusters allow for more precise estimates than previous work. Second, the direct effects of various childhood experiences on political ideology as an adult are measured. Next, following the hypothesis that childhood factors may be more strongly related to political ideology for people of some personality types than others, analyses are performed that include interaction terms for personality and childhood experience variables. Finally, extending on the significant interaction effect that is found between childhood trauma and openness, mediation and moderated mediation analyses are run in order to better understand the nature of the relationship between these two contributing factors to ideology.

All models employ ordered probit regressions on a five-point scale of political ideology, where “very liberal” receives a score of “5”. A variety of controls plausibly related to political ideology are incorporated into the models, including age, gender, race, log of income, and education level. In models looking at the childhood experience variables an additional control variable is included for whether or not food stamps were allocated in that period, because the household socio-economic status of the childhood upbringing may bias childhood experience (about 24% of our participants recall being the recipient, or others in their household, of public assistance such as food stamps).

4 Results

4.1 Direct Effects of Personality on Ideology

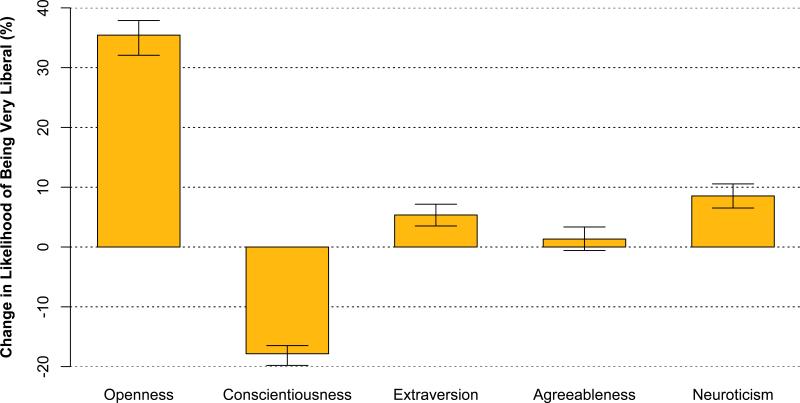

Based on previous work on the role of personality on ideology, it is expected that the openness and conscientiousness traits would be strongly associated with political ideology. Especially in the United States, liberalism is conceived of embracing change and pro-active policies, whereas conservatism is likened to personal responsibility, caution, and maintaining order (Mondak & Halperin 2008). The results align with such expectations. Figure 1 visualizes the marginal effects on ideology of each personality trait based on the ordered probit regression analysis reported in Table 1. Corroborating and extending the initial findings in political psychology, results indicate that “openness to experience” significantly predicts a higher self-reported score on liberal ideology (p≤0.000) and that “conscientiousness” significantly predicts a more conservative ideology (p≤0.000). Each personality trait is measured on a scale from 4 to 20. To illustrate the strength of the effects, consider increasing the “openness to experience” trait of an individual from a score of 12 (20th percentile) to a score of 16 (80th percentile); keeping all else constant, this would increase the likelihood of this person self-reporting to be very liberal by approximately 71%. Significant effects are also obtained for “neuroticism” (p≤0.000) and “extraversion” (p≤0.000) being positively associated with liberal ideology. Agreeableness (p=0.277) does not produce a significant effect on overall political ideology but this may be due to separate and contradicting tendencies on economic and social policies that are not captured on the aggregate conservative-liberal spectrum used here (Gerber et al. 2010, Verhulst, Hatemi & Martin 2010).

Figure 1.

Variation in the “big five” personality traits is associated with significant changes in political ideology. Marginal effects are presented, based on simulations of Table 1 model regression parameters, along with 95% confidence intervals. For each personality trait, all other traits and variables are held at their means. Outcome is set as the “very liberal” category. Change in outcome is based on a one standard deviation increase from the mean in the respective personality trait.

Table 1.

Ordered probit model of political ideology (1 = very conservative to 5 = very liberal) on the “big five” personality traits and control variables.

| Political ideology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | P-value | |

| Openness | 0.065 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.036 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Extraversion | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Agreeableness | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.277 |

| Neuroticism | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.019 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Male | −0.161 | 0.012 | 0.000 |

| Black | 0.084 | 0.020 | 0.000 |

| Hispanic | 0.101 | 0.073 | 0.000 |

| Asian | 0.075 | 0.081 | 0.351 |

| Income (log) | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Education | 0.035 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Intercept | 2.759 | 0.294 | 0.000 |

| N | 13,999 | ||

| PseudoR 2 | 0.019 | ||

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Standard errors (SE) and P-values are also presented.

Next, the sibling clusters in the Add Health data are used to compare siblings to each other by performing a type of matching procedure, in which the family environment is controlled for. An overall mean value is first constructed for each of the personality traits of all the siblings within each family, and then the difference between every individual's trait score and their family mean is calculated. This leads to two measures of variation in personality traits—that between families and that within families. By using the variation in within-family traits, it can be tested whether respondents who are, for example, more open than their siblings are also more likely to report being liberal. This family-based method specifies a variance-components based association analysis for sibling pairs and was first suggested in the behavioral genetics literature by Boehnke & Langefeld (1998) and Spielman & Ewens (1998). By decomposing personality trait scores into between-family (b) and within-family (w) components it is possible to control for spurious results due to population stratification because only the coefficient on the between-family variance (βb) will be affected by covariates such as the socio-economic status, race, and localization of the family. The association result is determined by the coefficient on the within-family variance (βw) which, in essence, shows whether variation in personality traits among siblings may be significantly associated with differences in political ideology between siblings. The following regression model is employed to perform this family-based association test:

where i and j index subject and family respectively. Tw is the within-family variance component of the individual's personality traits (measured as subject trait minus their family's mean trait score), Tb is the between-family variance component of the individual's traits (measured as their family's mean genotype score). Zk is a matrix of variables to control for individual sibling differences (age, gender, income, education), U is a family random effect that controls for potential genetic and environmental correlation among family members, and ε is an individual-specific error.

Family-based designs eliminate the problem of population stratification by using family members, such as siblings, as controls. While a family-based design is very powerful in minimizing Type I error (false positives) due to omitted variable bias, it reduces the power to detect true associations, and is thus more prone to Type II error or false negatives (Xu & Shete 2006). Of course, when data for siblings are available—as is the case in Add Health—then a family-based test produces the more robust results.

Table 2 reports the results of the family-based model for the influence of the big 5 personality traits on political ideology. The prior findings on openness to experience and conscientiousness are robust to this model specification. The results show that respondents who are more open than their siblings are more likely to report being liberal-minded and respondents that are more conscientious than their siblings are more likely to report being conservative-minded. The prior results on extraversion and neuroticism do not survive the family-based model specification and drop their statistical significance.

Table 2.

Ordered probit model of political ideology (1 = very conservative to 5 = very liberal) on the “big five” personality traits decomposed into within and between family variance components.

| Political ideology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | P-value | |

| Openness: within-family variance | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.031 |

| Openness: between-family variance | 0.079 | 0.011 | 0.000 |

| Conscientiousness: within-family variance | −0.029 | 0.008 | 0.001 |

| Conscientiousness: between-family variance | −0.036 | 0.010 | 0.000 |

| Extraversion: within-family variance | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.270 |

| Extraversion: between-family variance | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.212 |

| Agreeableness: within-family variance | 0.018 | 0.011 | 0.114 |

| Agreeableness: between-family variance | −0.003 | 0.012 | 0.792 |

| Neuroticism: within-family variance | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.296 |

| Neuroticism: between-family variance | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.022 |

| Age | −0.013 | 0.009 | 0.156 |

| Male | −0.172 | 0.038 | 0.000 |

| Income (log) | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.002 |

| Education | 0.025 | 0.009 | 0.006 |

| Intercept | 2.226 | 0.398 | 0.000 |

| N | 3,967 | ||

| PseudoR 2 | 0.018 | ||

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Standard errors (SE) and P-values are also presented.

4.2 Direct Effects of Childhood Experience on Ideology

A variety of childhood experiences that may affect political ideology later in life are considered next. The wording and distributions for each of the childhood variables can be found in the Appendix. These childhood variables are first considered in isolation using each in a separate regression, and are subsequently considered jointly.

Childhood trauma is considered first and was assessed retrospectively in Wave IV by using modified items from prior surveys (Finkelhor & Dziuba-Leatherman 1994, The Gallup Organization 1995). The maltreatment levels assessed in Add Health data are similar to other US estimates (Hussey, Chang & Kotch 2006). Following prior research (Goodwin & Stein 2004, Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod & Hamby 2009, Haydon, Hussey & Halpern 2011) responses were dichotomized and coded 1 if the specific type of maltreatment occurred at least once and were loaded in a childhood trauma index covering verbal, physical, and sexual abuse. Factor analysis suggests the existence of a single factor underlying these three abuse variables. About half of the sample population experienced some degree of maltreatment by a parent or adult caregiver before the age of 18. For the precise questions and descriptive statistics please refer to Tables 7–8 and 13 in the Appendix. The Add Health data set measures the age of first childhood abuse and, out of a total sample of N = 15,701, the mean first age of verbal abuse is 11.6 years (Std. dev. = 4.2; N cases = 6,722), the mean first age of physical abuse is 10.6 years (Std. dev. = 4.4; N cases = 2,687), and the mean first age of sexual abuse is 8.2 years (Std. dev. = 4.2; N cases = 796). This study does not suggest an ex-ante hypothesis about the direction of a possible effect but does anticipate that the lasting psychological and behavioral consequences of childhood trauma (Lam & Grossman 1997, Moran et al. 2011) may have a powerful influence on ideology.

Next, the broader context in which a respondent was raised is considered, and whether they felt safe in their school and neighborhood. It may be expected that these experiences will be less salient to an individual as compared to trauma in the home, but an adolescent's early orientation toward their community has been shown to affect other political attitudes and behaviors (Settle et al. 2010).

Finally, less traumatic experiences can also serve to shape a person's world view and thus their political ideology. A large body of work demonstrates that the attitudinal composition of friendships influence our political preferences (Huckfeldt, Johnson & Sprague 2004, Huck-feldt, Johnson & Sprague 2002, Parsons 2009, Mutz 2002). For some people, friendship itself may activate certain ideological positions (Settle et al. 2010) and the attitudes of the network in which one is embedded in high school affect later political behavior (Settle, Bond & Levitt 2011). This study therefore also considers the total number of friends that the individual has named—or is being named by—in Wave I of the Add Health data collection.

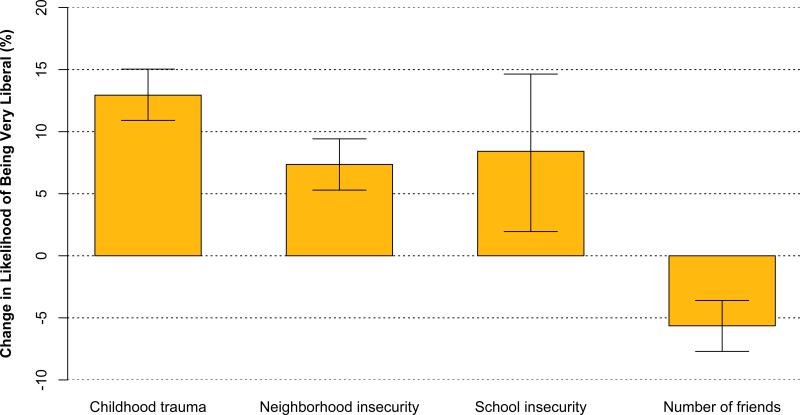

Table 3 shows the coefficients of these four variables and Figure 2 shows the simulated marginal effects with their confidence intervals. These traumatic, neighborhood, and social aspects of childhood all obtain significant main effects on political ideology later in life. Consistent with the small literature that exists on the topic (Lay, Gimpel & Schuknecht 2003, Campbell 2006), these results suggest that childhood experience matters for the way the political world is viewed as adults. To understand the relative effect of these childhood experiences in relation to each other, they are combined in a single regression. The results of this combined model are shown in Table 10 in Appendix. Childhood trauma and number of friends continue to come in significantly. However, the collinearity of the school and neighborhood insecurity measures weakens their individual effects in a joint analysis.

Table 3.

Ordered probit models of political ideology (1 = very conservative to 5 = very liberal) on the childhood environment variables. Coefficients are presented for regressions that considered these childhood variables separately controlling for gender, race, education, log of income, and whether food stamps were distributed in the childhood household.

| Political ideology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | P-value | N | R 2 | |

| Childhood trauma | 0.076 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 13,799 | 0.01 |

| Neighborhood insecurity | 0.032 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 9,526 | 0.01 |

| School insecurity | 0.035 | 0.017 | 0.034 | 9,519 | 0.01 |

| Number of friends | −0.007 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 9,993 | 0.01 |

Figure 2.

Variation in the childhood experience variables is associated with significant changes in political ideology. Marginal effects are presented, based on simulations of model regression parameters (Table 3), along with 95% confidence intervals. For each indicator, all other variables are held at their means. Outcome is set as the “very liberal” category. Change in outcome is based on a one standard deviation increase from the mean in the respective childhood indicator.

A theoretical interpretation of these observed effects of childhood experience on political ideology falls outside the scope if this paper but merits further research and discussion. A tentative logic would be that the experience of childhood trauma, as well as school and neighborhood insecurity, may instill a heightened sense of vulnerability in individuals. In turn, a sense of individual vulnerability is likely to incline people to political views that favor social programs and government intervention if a need arises. It could also be speculated that individuals who suffered childhood maltreatment will be wary of authority, while the added complexity of dealing with negative childhood emotions may draw them to a greater variety of experiences and less impulse control. Such psychological and behavioral consequences of childhood trauma may distance these individuals from conservative principles. However, prudence is required in interpreting these results and, ultimately, this research remains agnostic on the precise dynamics that link childhood experience to political ideology. This empirical work may serve to corroborate past research on the influence of childhood experience (Erikson 1968, Erikson 1963, Carver & Scheier 2000, Sameroff, Lewis & Miller 2000, Campbell 2006) and hopefully spur new research.

4.3 Interaction Effects of Childhood Experience and Personality on Ideology

Scholars theorize that the influence of personality may be related to the way that personality moderates the interpretation of the environmental influences around us (Lam & Grossman 1997, Shanahan & Hofer 2005). To address this question, the childhood environment variables are interacted with the five personality traits and their influence on ideology is estimated.

The interaction analyses with school and neighborhood insecurity, as well as number of friends, do not obtain statistical significance and this suggests that the influence of personality and these particular contextual variables are additive in nature. Only one interaction is significant. When interacting the personality traits with childhood trauma, the results indicate that childhood trauma intensifies the effect of the “openness to experience” trait on liberal political ideology for categories of higher openness. The interaction term for openness x childhood trauma in the regression analysis produces a positive and significant coefficient (p=0.002, see Table 4) that is robust to a Bonferroni correction of the significance threshold to account for the multiple testing with aforementioned childhood experience variables. The openness trait is more predictive of ideology for abused individual as compared to non-abused individuals.

Table 4.

Ordered probit model of political ideology (1 = v. conservative to 5 = v. liberal) on the “big five” personality traits, childhood trauma, their interaction terms, and control variables.

| Political ideology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | P-value | |

| Openness | 0.059 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.038 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Extraversion | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| Agreeableness | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.333 |

| Neuroticism | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.011 |

| Childhood trauma | −0.118 | 0.120 | 0.325 |

| Openness × trauma | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| Conscientiousness × trauma | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.172 |

| Extraversion × trauma | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.659 |

| Agreeableness × trauma | −0.004 | 0.005 | 0.483 |

| Neuroticism × trauma | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.573 |

| Age | −0.016 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Male | −0.173 | 0.012 | 0.000 |

| Black | 0.075 | 0.023 | 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.101 | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| Asian | 0.168 | 0.026 | 0.000 |

| Income (log) | −0.012 | 0.007 | 0.072 |

| Education | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Food stamps | −0.054 | 0.022 | 0.015 |

| Intercept | 2.515 | 0.368 | 0.000 |

| N | 12,852 | ||

| PseudoR 2 | 0.020 | ||

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Standard errors (SE) and P-values are also presented.

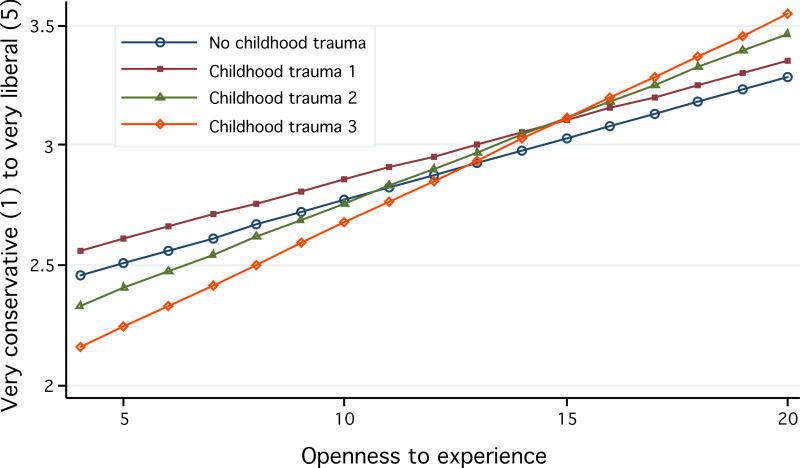

Figure 3 plots the regression output on the political ideology scale for each category of the openness trait, split between the varying degrees of childhood trauma (verbal, physical, and sexual abuse). Figure 3 illustrates the positive association between “openness to experience” and liberal political ideology, as well as the interaction effect of openness and childhood trauma. It is noted that childhood trauma intensifies the positive relationship between openness and liberal ideology. Given the novelty of this finding, the relationship between openness, childhood trauma, and political ideology is explored further in the next section.

Figure 3.

Childhood trauma interacts with the “openness” personality trait to influence political ideology. Regression output for political ideology (1 = very conservative; 5 = very liberal) is plotted for each category of the openness trait, split between the varying degrees of childhood trauma (verbal, physical, and sexual abuse). To obtain this figure, a linear regression instead of an ordered probit analysis is applied on the model specified in Table 4. For variable details see Tables 7–8 in Appendix.

4.4 Exploring the relationship between openness to experience, childhood trauma, and political ideology

The previous section showed that there exists a significant interaction between childhood trauma and openness on liberal ideology, in addition to the direct positive effects reported earlier (see Tables 1–4 and Figures 1–3, as well as Tables 10–13 in Appendix for empirical details). What is captured in a statistical interaction, however, represents a potentially complicated relationship. It is possible that childhood trauma (measured as an index of verbal, physical, and sexual abuse) is independent of the personality trait. Following past research, however, the relationship between trauma and openness is likely to run in both directions, with personality factors both influencing and being influenced by childhood abuse (Moran et al. 2011). The following analyses seek to gain some leverage on this question in its relation to political ideology.

First, the relationship between openness to experience and childhood maltreatment is looked at more closely. The openness trait is positively associated with such traumatic experience (r = 0.08, χ2=94, p≤0.000). Because of the timing in which the variables are measured, it is impossible to determine if being open makes a child more likely to be a victim of abuse, or if being a victim of abuse makes a child more likely to be open, but it is clear that the two variables are not independent of each other.

In order to get a better sense for the influence that the openness trait and childhood trauma variables may have on each other's respective influence on liberal political ideology this research performs mediation (Baron & Kenny 1986) and moderated mediation (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes 2007) tests. Because personality and childhood abuse are not independent from each other these mediation analyses do not infer causality and only serve to explore the data and stimulate further research. Although this research does consider personality traits to have a relatively stable component, as observed in longitudinal studies (Block & Block 2006), it is clear that personality is not fully developed before childhood experience and that childhood trauma has lasting impact on personality (Moran et al. 2011). Given the dynamic nature of the relationship between personality and childhood abuse these variables could be considered a mediator for one another if they carry some part of the influence that each has on political ideology.

Following the textbook approach to mediation analysis (Stata 2011), mediation would occur when (1) the independent variable (IV) significantly affects the mediator, (2) the IV significantly affects political ideology in the absence of the mediator, (3) the mediator has a significant unique effect on political ideology, and (4) the effect of the IV on political ideology shrinks upon the addition of the mediator to the model. Although Preacher & Hayes (2008) observe that among mediation methods it is recommended to use the bootstrapping approach, they note that the causal steps strategy and Sobel test employed here are valid provided that the sample is large so to provide sufficient statistical power while maintaining control of the Type I error rate (Preacher & Hayes (2008): p.880). Sobel-Goodman mediation tests are run for openness to experience as mediator (Table 5) as well as for childhood trauma as mediator (Table 6). The methodological extension by Preacher, Rucker & Hayes (2007) to moderated mediation analysis (Muller, Judd & Yzerbyt 2005) is also relevant for this research given that openness and childhood abuse are not independent and may act as a moderator for each others’ mediating influence. Preacher, Rucker & Hayes (2007) propose that the assumed independent variable itself can moderate the effect of the mediator on the outcome variable. From a theoretical perspective it is difficult to evaluate whether openness and childhood abuse would be either a moderator or a mediator (Baron & Kenny 1986, Kashy, Donnellan, Ackerman & Russell 2009) but the moderated mediation models allow for the added complexity of the independent variable also moderating the mediator and, as such, partially relax the constraints of a standard mediation model. All analyses are bootstrapped (2,000 replications) to generate percentile and bias-corrected confidence intervals.

Table 5.

Sobel-Goodman mediation tests for political ideology (1 = very conservative to 5 = very liberal) on childhood trauma mediated by the openness to experience trait.

| Sobel-Goodman Mediation Test: Liberal (DV), Trauma (IV), Openness (MV) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Z | P-value | |

| Sobel | 0.008 | 0.002 | 5.334 | 0.000 |

| Goodman-1 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 5.327 | 0.000 |

| Goodman-2 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 5.341 | 0.000 |

| Proportion of total effect that is mediated: 13.1% | ||||

| Percentile and Bias-corrected bootstrap results for Sobel (2,000 replications): | ||||

| Coefficient: 0.008 | ||||

| Percentile 95% confidence interval: 0.005 – 0.011 | ||||

| Bias-corrected 95% confidence interval: 0.005 – 0.011 | ||||

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Standard errors (SE) and Z and P-values are also presented.

Table 6.

Sobel-Goodman mediation tests for political ideology (1 = very conservative to 5 = very liberal) on the openness to experience trait mediated by childhood trauma.

| Sobel-Goodman Mediation Test: Liberal (DV), Openness (IV), Trauma (MV) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Z | P-value | |

| Sobel | 0.0008 | 0.0002 | 3.975 | 0.000 |

| Goodman-1 | 0.0008 | 0.0002 | 3.944 | 0.000 |

| Goodman-2 | 0.0008 | 0.0002 | 4.007 | 0.000 |

| Proportion of total effect that is mediated: 1.4% | ||||

| Percentile and Bias-corrected bootstrap results for Sobel (2,000 replications): | ||||

| Coefficient: 0.0008 | ||||

| Percentile 95% confidence interval: 0.0004 – 0.0012 | ||||

| Bias-corrected 95% confidence interval: 0.0005 – 0.0013 | ||||

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Standard errors (SE) and Z and P-values are also presented.

The results of the Sobel-Goodman mediation tests show that both trauma and openness are mediators for each others’ influence on political ideology. However, the mediation effect of openness is about ten times the size of the mediation effect of childhood trauma. This suggests that in a structural model the openness trait carries more of the traumatic influence across to political ideology than vice versa. As such, it could be understood that the openness to experience trait is the more dominant influence in this complex relationship. This inference is largely corroborated in the moderated mediation analyses with childhood trauma as the independent and moderating variable and openness as mediator (Table 7) and also with openness as the independent and moderating variable and trauma as mediator (Table 8). The conditional indirect effects on liberal ideology by way of openness to experience become larger with greater degrees of childhood trauma and are highly significant. When considering trauma as the potentially mediating variable in a moderated mediation analysis with openness to experience as both the independent and moderating variable there is no longer statistical significance. The conditional indirect effects obtained in these moderated mediation analyses could also be interpreted as giving a more important role to the openness trait.

These exploratory findings would align with recent work in behavioral genetics that show that the big five personality traits have a stable component with heritability estimates ranging around 50% (Verhulst, Eaves & Hatemi 2012, Verhulst, Hatemi & Martin 2010). This understanding that personality traits are developed early on is also shown (or assumed) in important contributions to the literature in political psychology (Block & Block 2006, Soldz & Vaillant 1999, Mondak et al. 2010, Gerber et al. 2010). It is important to highlight, however, that reverse causality can not be ruled out with childhood trauma most certainly also influencing the development of personality (Moran et al. 2011).

5 Discussion

A growing body of evidence suggests that there are inherent differences between people that affect their political ideology and behavior (Alford, Funk & Hibbing 2005, Fowler, Baker & Dawes 2008, Oxley, Smith, Hibbing, Miller, Alford, Hatemi & Hibbing 2008, Hatemi et al. 2010, Hatemi et al. 2011, Verhulst, Hatemi & Martin 2010). The most recent release of the Add Health data provides an excellent opportunity to explore how differences in the “big five” personality traits affect political ideology. In line with prior research in political psychology, it is found that “openness to experience” predicts liberal ideology and that “conscientiousness” predicts conservative ideology. The availability of sibling clusters in the data was leveraged to show that these results are also robust to the inclusion of family fixed effects.

Personality traits do not impact ideology in isolation from experience and environmental influences and it is therefore important to also consider the way in which personality traits may make people differentially responsive to aspects of their environment that shape political beliefs. The longitudinal nature of the data is especially well suited to examine how personality interacts with a variety of life course events in childhood. Research across literatures suggests that childhood experience has the ability to leave lasting psychological imprints as well as to interact with personality (Erikson 1968, Erikson 1963, Carver & Scheier 2000, Sameroff, Lewis & Miller 2000, Caspi et al. 2002, Caspi et al. 2003, Moran et al. 2011), with particular relevance to political ideology (Campbell 2006). This research considered a variety of childhood experiences such as childhood trauma, the perception of feeling safe in one's school or neighborhood, and number of friends. All of these childhood variables showed significant direct effects on later political ideology, but only childhood trauma was found to interact with “openness” in predicting ideology. This triangular relationship between openness, trauma, and ideology was further explored using mediation analysis which showed that the openness to experience trait is likely the dominant influence in this complex relationship. This result aligns well with the understanding that personality traits are relatively stable throughout the life course and partially developed prior to environmental influences such as childhood experience and network size (Mondak et al. 2010, Gerber et al. 2010), although the reverse influence of childhood experience on personality development needs to be emphasized (Moran et al. 2011).

Despite the richness of the data in certain regards, it is important to highlight four limitations of the data. First, the Add Health sample is restricted to individuals who are about 30 years old, though the distribution of answers is typical of other political ideology and personality surveys and may suggest some degree of generalizability. The age limitation is unlikely to substantially distort the results, but should be acknowledged. Second, recent work has noted that using the standard liberal-conservative ideological spectrum does not allow for more precise relationships between personality and, for example, social and economic policy dimensions (Gerber et al. 2010, Verhulst, Hatemi & Martin 2010). This may explain why the agreeableness trait does not appear to be associated with overall political ideology but does influence more specific political attitudes (Gerber et al. 2010). Third, the childhood trauma index captures the period prior to age 18. This is a relatively broad period of time and abuse may have a differential impact whether it happened in early childhood or adolescence. Finally, the personality measures are collected in Wave IV in early adulthood simultaneously with the political ideology measures. While personality has been shown to be relatively stable over the life course (Soldz & Vaillant 1999, Costa & McCrae 1988), we are measuring personality after the exposure to the childhood context. This makes it difficult to disentangle whether the personality factors are entirely independent of the specific contexts measured, contribute to the contextual exposure, or are in part a product of the contextual exposure. Our usage of the family-structure of the data and the mediation analyses helps disentangle this relationship, but it is clear that we cannot fully do so.

The results presented here may inform the growing literature on personality and ideology by extending the investigation into the mechanics of their relationship. There remains, however, much ground to cover in developing the theory behind why these individual differences should matter. For the study of the relationship between personality and ideology, this means developing stronger theories which explain how the particular components of the personality traits should influence political thinking and how it could make people differentially responsive to the environmental exposures we know also affect the development of ideology.

The literature on political ideology has benefitted greatly from incorporating a broader notion of what contributes to the development of ideology, including factors derived both from personality traits and from our environments. The findings of this study provide new evidence for the idea that differences in political ideology are deeply intertwined with variation in the nature and nurture of individual personalities.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Appendix

Table 9.

Survey questions and variable components.

| Questions and variable components |

|---|

| Political ideology |

| In terms of politics, do you consider yourself very conservative, conservative, middle-of-the-road, liberal, or very liberal? (1=v. conservative to 5=v. liberal) |

| Personality traits: |

| Additive indices for the “big 5” personality traits by loading their 4 component questions (Donnellan et al. 2006). |

| Openness |

| (1) I have a vivid imagination (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) |

| (2) I am not interested in abstract ideas (reversed) |

| (3) I have difficulty understanding abstract ideas (reversed) |

| (4) I do not have a good imagination (reversed) |

| Conscientiousness |

| (1) I get chores done right away |

| (2) I often forget to put things back in their proper place (reversed) |

| (3) I like order |

| (4) I make a mess of things (reversed) |

| Extraversion |

| (1) I am the life of the party |

| (2) I don't talk a lot (reversed) |

| (3) I talk to a lot of different people at parties |

| (4) I keep in the background (reversed) |

| Agreeableness |

| (1) I sympathize with others’ feelings |

| (2) I am not interested in other people's problems (reversed) |

| (3) I feel others’ emotions |

| (4) I am not really interested in others (reversed) |

| Neuroticism |

| (1) I have frequent mood swings |

| (2) I am relaxed most of the time (reversed) |

| (3) I get upset easily |

| (1) Before your 18th birthday, how often did a parent or other adult caregiver say things that really hurt your feelings or made you feel like you were not wanted or loved? (from 0=“this has never happened” to 5=“more than ten times”; asked in Wave IV, 2008) |

| (2) Before your 18th birthday, how often did a parent or adult caregiver hit you with a fist, kick you, or throw you down on the floor, into a wall, or down stairs? |

| (3) How often did a parent or other adult caregiver touch you in a sexual way, force you to touch him or her in a sexual way, or force you to have sexual relations? |

| Neighborhood insecurity |

| I feel safe in my neighborhood (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree; asked in Wave I, 1994-95) |

| School insecurity |

| I feel safe in my neighborhood (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree; asked in Wave I, 1994-95) |

| Number of friends |

| Individuals were asked about their social network in the in-school survey as part of Wave I. They were allowed to nominate up to five female and five male friends. This measure adds the number of friends that were named as well as the number of times the respondent was named as a friend. |

Table 10.

Sample means.

| Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political ideology | 3.04 | 0.93 | 1 | 5 |

| Openness | 14.50 | 2.45 | 4 | 20 |

| Conscientiousness | 14.64 | 2.70 | 4 | 20 |

| Extraversion | 13.22 | 3.06 | 4 | 20 |

| Agreeableness | 15.24 | 2.41 | 4 | 20 |

| Neuroticism | 10.45 | 2.74 | 4 | 20 |

| Childhood trauma | 0.71 | 0.82 | 0 | 3 |

| Neighborhood insecurity | 2.04 | 1.07 | 1 | 5 |

| School insecurity | 2.32 | 1.20 | 0 | 5 |

| Number of friends | 7.23 | 4.67 | 1 | 37 |

| Age | 29.15 | 1.74 | 25 | 34 |

| Male | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| White | 0.71 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Black | 0.19 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

| Asian | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 |

| Income | 34,632 | 38,284 | 0 | 920,000 |

| Education | 5.67 | 2.20 | 1 | 13 |

| Food stamps | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 |

Table 11.

Correlation table between political ideology (1= v. conservative to 5= v. liberal), childhood trauma, and the big five personality traits.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Political ideology | 1 | ||||||

| (2) Childhood trauma | 0.07 | 1 | |||||

| (3) Openness | 0.15 | 0.08 | 1 | ||||

| (4) Conscientiousness | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 1 | |||

| (5) Extraversion | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 1 | ||

| (6) Agreeableness | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 1 | |

| (7) Neuroticism | 0.02 | 0.17 | −0.15 | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.06 | 1 |

Table 12.

Ordered probit model of political ideology (1 = very conservative to 5 = very liberal) on childhood environment indicators and control variables.

| Political ideology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | P-value | |

| Childhood trauma | 0.076 | 0.012 | 0.000 |

| Neighborhood insecurity | 0.034 | 0.022 | 0.116 |

| School insecurity | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.714 |

| Number of friends | −0.006 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.034 | 0.004 | 0.000 |

| Male | −0.101 | 0.014 | 0.000 |

| Black | 0.073 | 0.023 | 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.096 | 0.036 | 0.008 |

| Asian | 0.167 | 0.028 | 0.000 |

| Income (log) | 0.019 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Education | 0.061 | 0.004 | 0.000 |

| Food stamps | −0.039 | 0.030 | 0.202 |

| Intercept | 3.192 | 0.412 | 0.000 |

| N | 7,642 | ||

| PseudoR2 | 0.012 | ||

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Standard errors (SE) and P-values are also presented.

Online appendix or for review purposes only

Table 13.

Cross-tabs for ideology and the “openness to experience” personality trait

| Political ideology | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | v. cons. | conservative | middle | liberal | v. liberal | Total |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| 6 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 7 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 25 |

| 8 | 12 | 27 | 45 | 21 | 6 | 111 |

| 9 | 9 | 53 | 67 | 27 | 9 | 165 |

| 10 | 29 | 109 | 196 | 57 | 19 | 410 |

| 11 | 46 | 151 | 308 | 112 | 39 | 656 |

| 12 | 99 | 369 | 789 | 250 | 80 | 1,587 |

| 13 | 70 | 405 | 906 | 296 | 77 | 1,754 |

| 14 | 121 | 539 | 1,228 | 494 | 105 | 2,487 |

| 15 | 81 | 452 | 972 | 460 | 88 | 2,053 |

| 16 | 84 | 490 | 1,123 | 671 | 155 | 2,523 |

| 17 | 47 | 209 | 500 | 323 | 110 | 1,189 |

| 18 | 31 | 146 | 338 | 223 | 83 | 821 |

| 19 | 19 | 65 | 149 | 134 | 65 | 432 |

| 20 | 16 | 43 | 137 | 120 | 81 | 397 |

| Total | 672 | 3,073 | 6,773 | 3,190 | 920 | 14,628 |

Pearson chi-squared = 642.6; Pr = 0.000

Table 14.

Cross-tabs for ideology and the “conscientiousness” personality trait

| Political ideology | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscientiousness | v. cons. | conservative | middle | liberal | v. liberal | Total |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 15 |

| 6 | 3 | 2 | 18 | 7 | 5 | 35 |

| 7 | 0 | 10 | 25 | 16 | 8 | 59 |

| 8 | 6 | 29 | 71 | 46 | 23 | 175 |

| 9 | 5 | 38 | 103 | 68 | 20 | 234 |

| 10 | 20 | 85 | 220 | 132 | 40 | 497 |

| 11 | 25 | 122 | 344 | 165 | 56 | 712 |

| 12 | 66 | 235 | 639 | 303 | 110 | 1,353 |

| 13 | 60 | 286 | 669 | 291 | 104 | 1,410 |

| 14 | 108 | 468 | 991 | 438 | 119 | 2,124 |

| 15 | 95 | 397 | 954 | 436 | 116 | 1,998 |

| 16 | 92 | 636 | 1,243 | 599 | 128 | 2,698 |

| 17 | 67 | 322 | 612 | 288 | 70 | 1,359 |

| 18 | 46 | 213 | 411 | 185 | 49 | 904 |

| 19 | 40 | 151 | 283 | 140 | 33 | 647 |

| 20 | 42 | 97 | 209 | 88 | 42 | 478 |

| Total | 676 | 3,092 | 6,798 | 3,302 | 926 | 14,701 |

Pearson chi-squared = 187.9; Pr = 0.000

Table 15.

Cross-tabs for ideology and childhood trauma

| Political ideology | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood trauma | v. cons. | conservative | middle | liberal | v. liberal | Total |

| 0 | 354 | 1,630 | 3,289 | 1,414 | 406 | 7,093 |

| 1 | 194 | 931 | 2,224 | 1,123 | 327 | 4,799 |

| 2 | 82 | 424 | 1,010 | 534 | 150 | 2,200 |

| 3 | 23 | 65 | 155 | 87 | 25 | 355 |

| Total | 653 | 3,050 | 6,678 | 3,158 | 908 | 14,447 |

Pearson chi-squared = 67.05; Pr = 0.000

Table 16.

Ordered probit model of political ideology (1 = v. conservative to 5 = v. liberal) on childhood trauma and control variables.

| Political ideology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | P-value | |

| Childhood trauma | 0.076 | 0.007 | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.026 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Male | −0.110 | 0.010 | 0.000 |

| Black | 0.083 | 0.022 | 0.003 |

| Hispanic | 0.091 | 0.021 | 0.000 |

| Asian | 0.140 | 0.024 | 0.000 |

| Income (log) | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Education | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Food stamps | −0.024 | 0.021 | 0.261 |

| Intercept | 3.22 | 0.251 | 0.000 |

| N | 13,799 | ||

| PseudoR2 | 0.008 | ||

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Standard errors (SE) and P-values are also presented.

Table 17.

Ordered probit model of political ideology (1 = v. conservative to 5 = v. liberal) on the “big five” personality traits, childhood trauma, and control variables.

| Political ideology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | P-value | |

| Openness | 0.064 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.036 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Extraversion | −0.009 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Agreeableness | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.451 |

| Neuroticism | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Childhood trauma | 0.048 | 0.007 | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.019 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Male | −0.161 | 0.011 | 0.000 |

| Black | 0.091 | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| Hispanic | 0.097 | 0.023 | 0.000 |

| Asian | 0.169 | 0.024 | 0.000 |

| Income (log) | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Education | 0.035 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Food stamps | −0.036 | 0.021 | 0.096 |

| Intercept | 2.582 | 0.298 | 0.000 |

| N | 13,770 | ||

| PseudoR2 | 0.019 | ||

Descriptive statistics are provided in the Appendix. Standard errors (SE) and P-values are also presented.

Footnotes

The author is indebted to Jaime Settle for help and inspiration along the way and also thanks James Fowler, Simon Hix, Chris Dawes, Piero Stanig, Slava Mikhaylov, and Brad Verhulst. The usual disclaimer applies. An earlier version of this research entitled “The Nature and Nurture of the Influence of Personality on Political Ideology and Electoral Turnout” was distributed as an APSA 2010 Annual Meeting paper.

References

- Adorno Theodor W., Frenkel-Brunswik Else, Levinson Daniel, Sanford Nevitt. The Authoritarian Personality. Harper and Row; New York: 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Alford JR, Funk CL, Hibbing JR. Are Political Orientations Genetically Transmitted? American Political Science Review. 2005;99(2):153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Almlund Mathilde, Duckworth Angela, Heckman James, Kautz Tim. Personality Psychology and Economics. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5500. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block Jack, Block Jeanne H. Nursery school personality and political orientation two decades later. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:734–749. [Google Scholar]

- Boehnke M, Langefeld CD. Genetic association mapping based on discordant sib pairs: the discordant-alleles test. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1998;62:950–961. doi: 10.1086/301787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Angus, Converse Philip, Miller Warren, Stokes Donald. The American Voter. Wiley; New York: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell David. Why We Vote: How Schools and Communities Shape Our Civic Life. Princeton University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carney Dana, Jost John, Gosling Samuel, Potter Jeff. The Secret Lives of Liberals and Conservatives: Personality Profiles, Interaction Styles, and the Things They Leave Behind. Political Psychology. 2008;29:807–840. [Google Scholar]

- Carver Charles S., Scheier Michael F. Perspectives on Personality. Allyn Bacon; Needham Heights, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt T, Mill J, Martin J, Craig I, Taylor A, Poulton R. Role of Genotype in the Cycle of Violence in Maltreated Children. Science. 2002;297(5582):851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt T, Taylor A, Craig I, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R. Influence of Life Stress on Depression: Moderation by a Polymorphism in the 5-HTT Gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Paul T., McCrae Robert R. Personality in adulthood: A six-year longitudinal study of self-reports and spouse ratings on the NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(5):853–863. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology. 1990;41:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Oswald FL, Baird BM, Lucas RE. The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:192–203. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson Erik H. Childhood and Society. Norton; New York, NY: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson Erik H. Identity: Youth and Crisis. Norton; New York, NY: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Dziuba-Leatherman J. Children as victims of violence—a national survey. Pediatrics. 1994;94(4):413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor David, Turner Heather, Ormrod Richard, Hamby Sherry L. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1411–1423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler James H., Baker Laura A., Dawes Christopher T. Genetic Variation in Political Participation. American Political Science Review. 2008;101(2):233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Froman Lewis A. Personality and Political Socialization. Journal of Politics. 1961;23(2):341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber Alan, Huber Gregory, Doherty David, Dowling Conor M., Ha Shang. Personality and Political Attitudes: Relationships across Issue Domains and Political Contexts. American Political Science Review. 2010;104(1):111–150. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Stein MB. Association between childhood trauma and physical disorders among adults in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34(3):509–520. doi: 10.1017/s003329170300134x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein Fred I. Personality and Political Socialization: The Theories of Authoritarian and Democratic Character. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1965;361:81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. 2009 http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Hatemi PK, Gillespie NA, Eaves LJ, Maher BS, Webb BT, Heath AC, Medland SE, Smyth DC, Beeby HN, Gordon SD, Montgomery GW, Zhu G, Byrne EM, Martin NG. A Genome-Wide Analysis of Liberal and Conservative Political Attitudes. Journal of Politics. 2011;73(1):271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hatemi PK, Hibbing P, Medland SE, Keller MC, Alford JR, Martin NG, Eaves LJ. Not by Twins Alone: Using the Extended Twin Family Design to Investigate the Genetic Basis of Political Beliefs. American Journal of Political Science. 2010;54(3):798–814. [Google Scholar]

- Haydon Abigail A., Hussey Jon M., Halpern Carolyn T. Childhood Abuse and Neglect and the Risk of STDs in Early Adulthood. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011;43(1):16–22. doi: 10.1363/4301611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil Alain Van, Kossowska Malgorzata, Mervielde Ivan. The Relationship Between Openness to Experience and Political Ideology. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;28:741–51. [Google Scholar]

- Huckfeldt Robert, Johnson Paul, Sprague John. Political Environments, Political Dynamics, and the Survival of Disagreement. Journal of Politics. 2002;64(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huckfeldt Robert, Johnson Paul, Sprague John. Political Disagreement: The Survival of Diverse Opinions within Communication Networks. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KC, Rowe DC. Genetic and Shared Environmental Influences on Adolescent BMI: Interactions with Race and Sex. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28(4):265–278. doi: 10.1023/a:1021619329904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost John. The end of the end of ideology. American Psychologist. 2006;61(7):651–670. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost John, Glaser Jack, Kruglanksi Arie, Sulloway Frank. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;192(3):339–375. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost John, Napier Jaime L., Thorisdottir Hulda, Gosling Samuel D., Palfai Tibor P., Ostafin Brian. Are Needs to Manage Uncertainty and Threat Associated With Political Conservatism or Ideological Extremity? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33(7):989–1007. doi: 10.1177/0146167207301028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Donnellan MB, Ackerman RA, Russell DW. Reporting and Interpreting Research in PSPB: Practices, Principles, and Pragmatics. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:1131–1142. doi: 10.1177/0146167208331253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam JN, Grossman FK. Resiliency and adult adaptation in women with and without self-reported histories of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:175–196. doi: 10.1023/a:1024821927574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay J. Celeste, Gimpel James G., Schuknecht Jason E. Cultivating Democracy. Brookings Institution Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McClosky Herbert. Conservatism and Personality. American Political Science Review. 1958;52:27–45. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae Robert, Costa Paul. Handbook of Personality Research: Theory and Research. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 139–53. chapter A Five-factor Theory of Personality. [Google Scholar]

- Mondak Jeffery, Halperin Karen. A Framework for the Study of Personality and Political Behaviour. British Journal of Political Science. 2008;38:335–362. [Google Scholar]

- Mondak Jeffery, Hibbing Matthew, Canache Damarys, Seligson Mitchell, Anderson Mary. Personality and Civic Engagement: An Integrative Framework for the Study of Trait Effects on Political Behavior. American Political Science Review. 2010;104(1):85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Moran P, Coffey C, Chanen A, Mann A, Carlin JB, Patton GC. Childhood sexual abuse and abnormal personality: a population-based study. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1311–1318. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutz Diana C. The consequences of cross-cutting networks for political participation. American Journal of Political Science. 2002;46(4):838–855. [Google Scholar]

- Oxley DR, Smith KB, Hibbing MV, Miller JL, Alford JR, Hatemi PK, Hibbing JR. Political Attitudes are predicted by Physiological Traits. Science. 2008;54(3):798–814. doi: 10.1126/science.1157627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons Bryan M. Social Networks and the Affective Impact of Political Disagreement. Political Behavior. 2009;32(2):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher Kristopher, Hayes Andrew. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff Arnold J., Lewis Michael, Miller Suzanne M. Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. 2nd ed. Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen Harald, Schumann Siegfried. Personality Traits, Partisan Attitudes, and Voting Behavior: Evidence from Germany. Political Psychology. 2007;28(4):471–98. [Google Scholar]

- Settle Jaime, Dawes Christopher T., Christakis Nicholas A., Fowler James H. Friendships Moderate an Association Between a Dopamine Gene Variant and Political Ideology. Journal of Politics. 2010;72(4):1189–1198. doi: 10.1017/S0022381610000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settle Jaime, Bond Robert, Levitt Justin. The Social Origins of Adult Political Behavior. American Politics Research. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan Michael J., Hofer Scott M. Social Context in Gene-Environment Interactions: Retrospect and Prospect. Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2005;60B:65–76. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley Chris G., Duckitt John. Personality and Prejudice: A Meta-Analysis and Theoretical Review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2008;12(3):248–279. doi: 10.1177/1088868308319226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldz Stephen, Vaillant George E. The Big Five Personality Traits and the Life Course: A 45-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Research in Personality. 1999;33(2):208–232. [Google Scholar]

- Spielman RS, Ewens WJ. A sibship test for linkage in the presence of association: the sib transmission/disequilibrium test. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1998;62:450–458. doi: 10.1086/301714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Sobel-Goodman mediation tests. 2011 http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/ado/analysis/sgmediatio%n.hlp.htm.

- The Gallup Organization . Disciplining Children in America: A Gallup Poll Report. Technical report. The Gallup Organization; Princeton, NJ: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst Bradley, Eaves Lindon, Hatemi Peter K. Correlation not Causation: The Relationship between Personality Traits and Political Ideologies. American Journal of Political Science. 2012;56(1):34–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00568.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst Bradley, Hatemi Peter K., Martin Nicholas G. The Nature of the Relationship Between Personality Traits and Political Attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;49(4):306–310. [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Shete S. Mixed-effects Logistic Approach for Association Following Linkage Scan for Complex Disorders. Annals of Human Genetics. 2006;71(2):230–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]