Abstract

Three-arm non-inferiority (NI) trial including the experimental treatment, an active reference treatment, and a placebo where the outcome of interest is binary are considered. While the risk difference (RD) is the most common and well explored functional form for testing efficacy (or effectiveness), however, recent FDA guideline suggested measures such as relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), number needed to treat (NNT) among others, on the basis of which NI can be claimed for binary outcome. Albeit, developing test based on these different functions of binary outcome are challenging. This is because the construction and interpretation of NI margin for such functions are non-trivial extensions of RD based approach. A Frequentist test based on traditional fraction margin approach for RR, OR and NNT are proposed first. Furthermore a conditional testing approach is developed by incorporating assay sensitivity (AS) condition directly into NI testing. A detailed discussion of sample size/power calculation are also put forward which could be readily used while designing such trials in practice. A clinical trial data is reanalyzed to demonstrate the presented approach.

Keywords: Assay Sensitivity, Binary Outcome, Fraction Margin, Non-inferiority Margin, Odds/Risk Ratio/NNT, Three-arm Trial

1. Introduction

With the steady improvements in health care technologies, standard of care, and clinical outcomes, the incremental benefits of newly developed interventions may be only marginal over existing treatments. However, in the presence of established treatments/therapies, placebo-controlled Randomized Control Trials (RCTs) are neither ethical nor clinically justified. Active-controlled NI trial is an attractive alternative in such situations, particularly when a slightly less efficacious treatment may be preferable to a group of patients in view of lower toxicity, less intensive side effects, ease of delivery and other less incapacitating factors. NI trials are intended to show if the new intervention retains a substantial portion of the active control effect, dictated by a pre-specified margin, often termed as NI margin (δ). Such margin must be prospectively defined and should be so chosen to reflect maximum acceptable extent of clinical non-inferiority of an experimental treatment. Further detailed discussion on the construction and desirable properties of NI margin can be found in the regulatory guidelines(FDA (2016), ICHE9 (2009), ICHE10 (2009)) and references (e.g. Althunian et al. (2017), Schumi and Wittes (2011), Brown et al. (2006), Hung and Wang (2004)). NI trials may or may not include a placebo arm due to ethical reasons. Two-arm placebo-free NI trials make two important assumptions regarding Assay Sensitivity (ICHE9 (2009), ICHE10 (2009)) and Constancy and depends heavily on external validations (D’Agostino et al. (2003) and FDA (2016)) and several other limiting factors as specified in Kieser and Stucke (2016). To alleviate some of these issues and if ethically acceptable and practically feasible, it is recommended by EMA (2005) to include a placebo arm in the current trial, resulting in a three-arm “gold-standard” design that has greater confidence concerning AS and lesser concern related to external validity.

For three-arm trial in the Frequentist setup, Pigeot et al. (2003) first proposed the fraction margin approach, where NI margin is adaptively formulated as the pre-specified negative fraction of the unknown effect size of the reference treatment over placebo in the current three-arm trial. Kieser and Friede (2007) extended this approach for the binary outcome for risk difference (RD). While RD is the simplest functional form for binary outcomes, as mentioned in the recent FDA guidance (FDA (2016), Page 24) there are other functionals (e.g., risk ratio (RR), odds ratio (OR), number needed to treat (NNT), risk reduction etc.) which could also be used to test the treatment effect (Hashemi et al., 1997) and claim NI. Under the NI setup, there exists published work for odds ratio using Frequentist’s approach for two-arm trial, see for example Hilton (2010) and Rousson and Seifert (2008), but no work exists for three-arm trial. Also, to the best of our knowledge for RR and NNT (Keefe et al., 2013) type functional form, no work on NI testing exists for either two or three-arm trial. This motivates us to introduce such methods and develop NI test procedure under Frequentist approach in this article. Apart from extending popular tests based on fraction margin approach for such functionals, in this paper we also propose a new approach based on conditional principle which directly employs the AS condition under Frequentist setup. This approach shows additional gain in sample size to achieve a desired level of power under certain situations. Extensive tables are calculated for sample size for all three types of functionals.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we give the NI hypothesis and the details of NI margin. We show the non-uniqueness of the NI margin for different functionals. In Section 3, we discuss the existing method and propose a conditional Frequentist’s method for testing NI. In Section 4, we discuss the power and sample size calculation for the three functionals. Finally in Section 5, we apply our proposed methods on a published clinical trial data set. We conclude the article with discussions in Section 6. All proofs are provided in supplementary file for brevity purpose.

2. Non-inferiority Hypothesis Testing Setup

For a three-arm trial, fraction margin approach (Pigeot et al. (2003), Kieser and Friede (2007)) is popularly used for testing NI hypothesis and finding the corresponding decision rule. We begin our illustration borrowing the notations from Kieser and Friede (2007). Denote the primary end-points from the Placebo (P), Reference (R) and the Experimental (E) treatment in the current trial by XP, XR and XE respectively, each following Bin (nl, πl), where πl is the probability of success and nl is the sample size for the lth arm, l ∈ {P, R, E}. Without loss of generality, we assume that higher response probabilities indicate greater treatment benefits. Gamalo et al. (2011) used the two-arm fixed margin approach for NI testing considering the RD as the function of interest. Kieser and Friede (2007) formulated the three-arm NI hypothesis for binary outcome under fraction margin approach, where NI hypothesis for RD in terms of NI margin δ is given by

| (2.1) |

In the fraction margin approach, the construction of δ(< 0) can be mathematically expressed as δ = f (πR − πP ), where f is a negative fraction f ∈ [−1, 0] assuming the condition of assay sensitivity, that is, πR − πP > 0 holds. Figure 1(a) shows the NI region in the difference scale, which is directed to the right of πR + δ.

Figure 1:

Three-arm NI Trial for (a) RD Margin with δ, (b) RR Margin 1 with δ1 and (c) ϵ −substantial non-inferiority for NNT

Before discussing the NI testing for a three-arm NI trial in terms of (1) RR, (2) OR and (3) NNT, we first reformulate the NI hypothesis using a general functional form as

| (2.2) |

where the decision boundary g (δ) is some function of δ, such that |δ| ∈ [0, 1], which denotes an appropriate portion of the unknown effect size of the active-control over placebo. RD hypothesis expressed in equation (2.1) can be also seen as a special case of above. For example, consider ψ(πE, πR) = πE − πR, then the boundary is g(δ) = δ, which also happens to be the same as the NI margin itself. In the RR (or OR) scale, one can choose g (δ) = 1+δ, implying the NI margin is δ(< 0), which we term as Margin 1. Choosing a too restrictive δ, that is close to zero, would require large number of subjects to claim NI, whereas a too loose choice of δ may potentially approve a substantially inferior drug. In the RR (or OR) scale we construct δ = δ1 = f(1 − ψ(πP, πR)(< 0), where f ∈ [−1, 0] as in the RD case. Using this expression for δ1, we can write the hypothesis in (2.2) as

| (2.3) |

In practice, clinical considerations should drive the choice of f and some of the reasonable values are . For all testing (e.g. RD, RR, OR etc.) choosing f = 0 implies NI margin is zero, hence the hypothesis in (2.1) and (2.3) becomes the superiority test of πE over πR. While for f = −1 the active control loses its practical significance over placebo, hence the test reduces to the simple superiority test of πE over πP. This can be easily checked for all functional forms considered in this paper. Note that, construction of a margin must satisfy these two boundary conditions. However, there may be other possible mathematical form which can adhere to these, thus implying such a margin may not be unique. To elucidate this fact one can also formulate the NI hypothesis by taking g(δ) = δ and constructing δ = δ2 = (ψ(πP, πR))−f(> 0) where f ∈ [−1, 0] (see Wangge et al. (2013)). In this case the NI margin is 1 − g(δ) = 1 − δ2, which we term as Margin 2. Thus the NI hypothesis under Margin 2 becomes

| (2.4) |

The two NI margins satisfy both the boundary conditions for f = 0 and −1, however, lead to two slightly different NI testing. Next, we discuss the specific cases for RR, OR and NNT.

2.1. Risk Ratio

Margin 1 : For RR the function and . Thus under Margin 1, the NI hypothesis testing in (2.3) becomes:

| (2.5) |

Margin 1, i.e. δ = δ1 is constructed as the fraction of the difference between the unity and ratio of placebo to active control (reference) treatment effect, in the current three-arm trial.

As can be seen from Figure 1 (b), the NI region is directed to the right side of the point (1+δ1). Clearly from (2.5) we see that for f = 0 and f = −1, the test satisfies two boundary conditions. Now putting θ = 1 + f and after simplification the hypothesis in equation (2.5) can be written as

| (2.6) |

where θ is the pre-specified fraction of the effect of the reference drug relative to the placebo. The test drug would be non-inferior if its efficacy relative to placebo achieves at least θ×100% of the efficacy of the reference drug compared to placebo. Although different values of θ (θ ∈ [0, 1]) are chosen for different purposes, specifically for the NI testing of the new drug, θ is restricted in [0.5,1), thus making sure that the new drug retains at least 50% effect of the active control.

Margin 2 : For and , the NI hypothesis testing in (2.4) under RR Margin 2 can be written by taking logarithm as

| (2.7) |

Taking θ = 1+f as before, the following hypothesis can be written after some simplification

| (2.8) |

Compared to the Margin 1 hypothesis in (2.6), Margin 2 hypothesis above represents the testing in the logarithm of each proportion (i.e. πl, l ∈ {P, R, E}). The interpretation of θ in terms of effect retention in the log scale is little more involved compared to Margin 1. Albeit, since all the Frequentist tests are asymptotic normal approximation, the log transformed version of Margin 2 is expected to perform better.

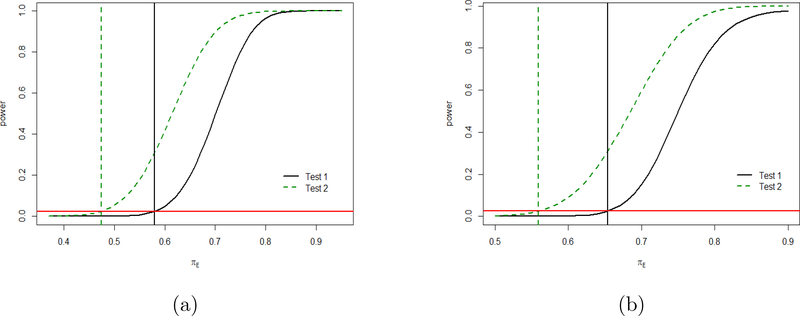

To compare the NI regions we plot the boundary g(δ) as function of θ ∈ [0, 1] for test 1 and test 2 respectively in Figure 2 (a) and observe that both are increasing functions of θ. The area above the two curves are the respective NI regions, which happen to be bounded within the unit square. The vertical line corresponds to θ = 0.5 and the region to its right corresponds to the values of θ chosen for NI testing. However, for all values of θ, the NI region for NI hypothesis testing 2 (2.8) is bigger than that for NI testing 1 (2.6), implying that the NI testing 2 is more powerful as compared to the NI testing 1. This is also depicted in Figure 3 (a) where we plot the power curves for θ = 0.8 and total sample size of N = 300 under equal allocation, keeping πR and πP fixed at 0.7 and 0.1 respectively. Details of the derivation for the power curves are given later in Section 3. The vertical lines represent the respective values of πE under the null hypothesis for the respective margins.

Figure 2:

Comparison of NI regions for RR tests in (a) and OR tests in (b).

Figure 3:

Comparison of power curves for two margins of RR in (a) and OR in (b).

Remark 1: Since Margin 2 is formulated in the logarithm scale, same value of θ will have different impact in terms of margin width, thus further affecting resulting NI test. One can show that under the same preservation level θ (or loss-of-effect f) of E and for fixed control effect in the RR scale , the ratio has to exceed a smaller quantity under Margin 2 as compared to Margin 1 for E to be non-inferior. This implies that the NI test based on Margin 2 gives a little more relaxed margin as compared to the test based on Margin 1, without compromising θ. This is equivalent to saying that if we fix the NI margin or equivalently the quantity that needs to exceed for E to be non-inferior, then θ under Margin 2 has to be larger than that under Margin 1 to achieve this. Denoting θ by θ1 under Margin 1 and by θ2 under Margin 2, we can express θ1 as a function of θ2 as . Although in this paper we calculate the power and sample size under Margin 2 across different θ for all functionals, the same will be true under Margin 1 for a slightly smaller θ which can be readily obtained from the above relation between θ1 and θ2. For example, when πR = 0.7 and πP = 0.5 giving , and taking θ2 = 0.8, we obtain the value of θ1 as 0.772.

Remark 2: Note that when the function of interest is Risk reduction, the function ψ(πE, πR) takes the form . From (2.5) we have . Hence the NI hypothesis and test procedures developed for risk ratio is exactly identical for risk reduction, and thus the latter does not need any separate derivation. Risk Reduction is another possible functional form mentioned in the FDA guidance (FDA, 2016).

2.2. Odds Ratio

Margin 1 : For OR the function , and similarly one can define ψ(πP, πR). Thus, under Margin 1, the NI testing in (2.3) becomes the following:

| (2.9) |

Clearly from (2.9) we see that for f = 0, the margin δ1 becomes 0 and hence the above test will be a superiority test of the experimental treatment (E) over the control (R) in the current trial since . Again for f = −1, we see that the test (2.9) becomes the simple superiority test of πE over πP. Now putting θ = 1 + f and after some simplification the above test becomes

| (2.10) |

where θ holds the similar interpretation as described in the context of RR before.

Margin 2 : The NI hypothesis testing in (2.4), under Margin 2, can be written by taking logarithm as

| (2.11) |

Taking θ = 1 + f the following test can be obtained from (2.7) after some simplification

| (2.12) |

Similar to RR, we plot NI regions and the power curves for OR under the two tests resulted from the respective NI margins in Figure 2 (b) and Figure 3 (b) respectively. We again observe that test 2 is more powerful compared to test 1 for OR since the former gives a more relaxed margin compared to the latter under fixed θ and fixed control effect in the OR scale. The relation between the two preservation levels under the respective margins in the OR scale becomes . Note that as in RR case the logarithm transformations make the data conform more closely to the Normal distribution giving better asymptotic performance.

2.3. NNT

As discussed for RD the NI hypothesis in (2.1) and (2.2) will be of the following form:

| (2.13) |

where the boundary g(δ) = δ, which is constructed as the negative fraction of the unknown difference between the control and placebo in the current trial (Kieser and Friede, 2007). Since NNT is the inverse of RD, one would want the value of NNT to be as small as possible. The higher the value of NNT, less effective is the treatment (Keefe et al., 2013). The ideal case would be when all patients in the treatment arm show improvement while none in the control arm has improved leading to the value of NNT to be 1. For treatments like pain killer for acute pain, an effective treatment is expected to have an NNT between 2–5. In other situations like using aspirin after heart attack, a quite higher NNT (40 +) would indicate an effective therapy, while NNT can be as low as 1 for treating a sensitive bacterial infection with antibiotics (Cook and Sackett, 1995). In the context of NI testing for RD, experimental intervention E is declared to be non-inferior over R if the treatment effect πE exceeds πR +δ, (δ < 0) (in Figure 1 (a)). Hence the NI hypothesis for NNT can be formulated from (2.13) by taking the reciprocal of both sides. However, to avoid taking the reciprocal of 0, one can formulate NI hypothesis, where E will be declared ϵ-substantially non-inferior over R if πE exceeds πR + δ + ϵ, where ϵ > 0 is a pre-chosen small integer. We write the ϵ-substantial NI hypothesis below:

| (2.14) |

Figure 1 (c) shows the ϵ-substantial non-inferiority region which is to the right of the point πR + δ + ϵ. Now we formulate the NI hypothesis for NNT from (2.14) in the following with the condition that πE > πR + δ

| (2.15) |

where D is a positive integer denoting the additional number of patients required to declare NI of E over R (Cook and Sackett, 1995). Note that in case πE < (πR + δ), NI testing of E over R does not have any practical meaning. After some simplification and putting θ = 1 + f, f ∈ [−1, 0] and δ = f (πR − πP ), the NI hypothesis for NNT in (2.15) takes the form:

| (2.16) |

This is exactly same as the hypothesis for RD when ϵ → 0. The interpretation of θ and f remain same as for the RD case.

3. Proposed Approach for NI Testing

For testing NI hypothesis we follow the general guideline developed by Pigeot et al. (2003) and Kieser and Friede (2007). The MLE of the Binomial proportion πl is and its variance is given by , l ∈ {E, R, P}. In the Frequentist’s approach the test statistics are based on the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) of the parametric function ψ (πE, πR) and ψ (πP, πR) and under asymptotic normality, the statistic is assumed to follow N (0, 1) under H0 in (2.2), where is some function of . Instead of MLE one may also consider the restricted maximum likelihood estimator (RMLE) of πl subject to the constraint ψ (πE, πR) = g (δ). More specifically for risk difference the test statistic for three-arm NI testing is , where, and . Though Pigeot et al. (2003) explicitly mentioned that superiority of the reference over placebo (i.e the AS condition) must be tested before one employs fraction-margin approach for testing NI hypothesis. However, in practice this key first step is often ignored. This may lead to somewhat over estimation of the sample size. Moreover the AS condition (either tested or assumed) is not used further in NI testing itself. In this article we first develop traditional Frequentist’s approach of NI testing for RR, OR and NNT closely following the marginal approach developed earlier for RD. It turns out as a common rule that the pretest of AS over NI is subordinated in the complete test procedure. As mentioned in Mielke and Munk (2009) the power of simply testing NI nearly coincides with the power of complete (or joint) test procedure for commonly used alternatives. Thus, the focus of testing non-inferiority is almost always on NI hypothesis itself, albeit AS condition must be verified first in all practical examples. We note that, for all the examples in the current manuscript we always ensured first that the AS condition is met. However, since the two test statistics used for AS and NI, respectively, are correlated, we put forward the fact that the hypothesis for NI testing must be tested conditionally based on the fact that the AS null hypothesis is rejected already. Next, we propose the conditional approach of NI testing, thus incorporating the AS condition πR − πP > 0 in the Frequentist’s statistic itself.

In the following two subsections we give the Frequentist’s approach of NI testing based on the marginal and conditional approach. We discuss NI testing for both Margin 1 and Margin 2. Note that all Frequentist’s tests are asymptotic approximate and the performance of such tests depend upon the accuracy of transformation for all the functions. We note that one can also perform score test or likelihood ratio test (Mielke, 2010; Tang et al., 2014) to conduct the NI testing. However, in our experience the performance of such tests are very close to that of normal approximation. This is not completely surprising given the large sample size, which, often is a general characteristic of many NI trials. Specifically, some additional results of score test in that direction are included in supplementary material. Albeit, as suggested by one reviewer these are all plausible alternatives and may enhance performance of the test in certain situations.

3.1. Test Procedure and Sample Size: Marginal Approach

Rather than developing separate tests for RR, OR and NNT, we first write the the NI hypotheses in (2.6), (2.8), (2.10) and (2.12) and (2.15) in a general form as

| (3.1) |

where ϵ ≥ 0. For RR and OR, ϵ = 0 while for NNT, ϵ > 0. For RR test 1: g(πl) = πl, for RR test 2: g(πl) = log(πl). For OR test 1: g(πl) = πl/(1 − πl) and for OR test 2: g(πl) = log(πl/(1 − πl)), and for NNT, g(πl) = πl, l ∈ {E, R, P}. Now consider the test statistic for testing the NI hypothesis in (3.1), being the MLE of πl, l ∈ {E, R, P}. The variance of T will be , where at , for l ∈ {E, R, P}. For g(πl) = πl, (RR test 1 and NNT); for g(πl) = log(πl) ; for g(πl) = πl/(1 − πl), ; and for g(πl) = log(πl/(1 − πl)), . Now under asymptotic normality we assume under H0, since μT = E(T) = g(πE) − θg(πR) – (1 − θ)g(πP) − ϵ = 0 under H0. So the rejection criteria will be Z > z1−α, where z1−α is the 100(1−α)% of the standard Normal distribution. The value of α is usually chosen to be 0.025.

3.1.1. Sample Size

For the sample size determination we first derive the power function of the above test procedure. We use the notation πl,1 to denote the proportion in the lth arm under the alternative hypothesis, and πl,0 to denote the same under H0. Borrowing notations from Kieser and Friede (2007), let ψ = g(πE) − θg(πR) – (1 − θ)g(πP) − ϵ and let ψ1 = g(πE,1) − θg(πR,1) − (1 − θ)g(πP,1) − ϵ for the alternative to be detected. The variance of the MLE under H1 will be , where is with πl replaced by πl,1 and the expression of for NNT and different RR and OR tests are described above. Now, for simplicity, we express the sample size in the reference (nR) and the experimental (nE) arms as the ratio r1 and r2 respectively of the sample size nP = n, say, in the placebo arm such that nP : nR : nE = 1 : nR/nP : nE/nP = 1 : r1 : r2. Here r1 and r2 are known positive quantities that determine the allocation ratio of the sample sizes in the arms R and E respectively, relative to the arm P. The total sample size, thus, would be N = n(1 + r1 + r2). Since involves nP, nR and nE we replace the latter two in terms of the ratios of nP and denote under H1. Analogously, ψ0 and τ0 denote the same expressions as ψ1 and τ1, replacing πl,1 by πl,0 under H0, satisfying the restriction g(πE,0) − θg(πR,0) – (1 − θ)g(πP,0) = ϵ and this implies ψ0 = 0. Under asymptotic normality and are assumed to follow N(0, 1) under H0 and H1 in (3.1) respectively. Hence, the asymptotic expression of power is given by

| (3.2) |

where Φ(·) denotes the cumulative distribution function of N(0, 1). For achieving a power of (1 − β) % the sample size nP can be obtained explicitly as

| (3.3) |

3.2. Test Procedure and Sample Size: Conditional Approach

We introduce our conditional approach for NI hypothesis testing given in (3.1) by incorporating the AS condition (i.e. πR > πP ). For finding the MLE we truncate the parameter space of (πE, πR, πP ) such that it belongs to {πE, πR, πP : πE ∈ [0, 1], πR ∈ [0, 1], πP ∈ [0, 1], πR > πP }. One may develop an LR-test based on the statistic

| (3.4) |

under null hypothesis subject to the imposed condition (πR > πP ) via Wald-type test. Following Mutze et al. (2015) one can improve the convergence via the restricted maximum likelihood (RML) which requires solving under H0

| (3.5) |

where logl(πE, πR, πP ) denotes the log-likelihood. This optimization problem can be solved numerically but no closed form expression is possible. One practical strategy to reduce computational burden, that is often recommended in practice, is to work with unrestricted MLE which is , however only considering the part restricted by , which is . This strategy (see Huang et al. (2011) and Kulldorff (1997)) is proved to be quite useful in many practical applications. Since working with product of random variables is little cumbersome, one can further show that . Since , are i.i.d. random variables, it is easy to prove which can be absorbed as a constant. Hence for all practical purpose one can consider the distribution of the test statistic, . For notational simplicity from now onwards we denote the ML estimate by , l ∈ {E, R, P}. Note that for the specific forms of g(πl) defined above for RR, OR and NNT, g(πl) is monotone in πl, l ∈ {E, R, P}. Hence imposing the restriction πR > πP is equivalent to g(πR) > g(πP ). This leads to the modified test statistic for NI testing: . We write W as (U – ψV – ψ|V > 0), where and are two correlated random variables. Under the asymptotic normality of W we have , where E[W] = μw and .

Lemma 3.2.1 Under conditional normal approximation, the mean μw and variance of , for ϵ ≥ 0 are given by

| (3.6) |

More specific values can be obtained for different tests as below,

Proof: See A.1 in the file of supplementary material.

As before, we denote under H0, πE by and under H1, πE by as point alternative. Under H0, the expression of can be obtained by solving . Under H1, satisfies . Note πE is involved in the expression of the mean and variance of W. Hence under asymptotic normality, we have the following

The critical region of the test is given by W > k∗, where k∗ is obtained by assuming a test of size , implying , where z1−α is the 100(1 − α)% percentile point of the N (0, 1) distribution.

3.2.1. Sample Size

Using our proposed approach we can calculate sample size for the assessment of NI to attain a desired power. We give the expression of the power of the test for a point alternative . Now to obtain the power function of the test we fix πR, πP and θ and vary . The sample size nP = n (of the arm P) is calculated from the following equation so that the power achieved is at least 100(1 − β)%:

| (3.7) |

For example, setting β at 20%, or the power at 80%, n is determined from equation (3.7). In our sample size calculation we fix πR and πP and vary under H1 satisfying . Under H0, is obtained from . We obtain the power function by varying . Thus, we obtain nP from (3.3) for each and obtain the sample size in the other arms and hence the total sample size as a function of the allocation ratios.

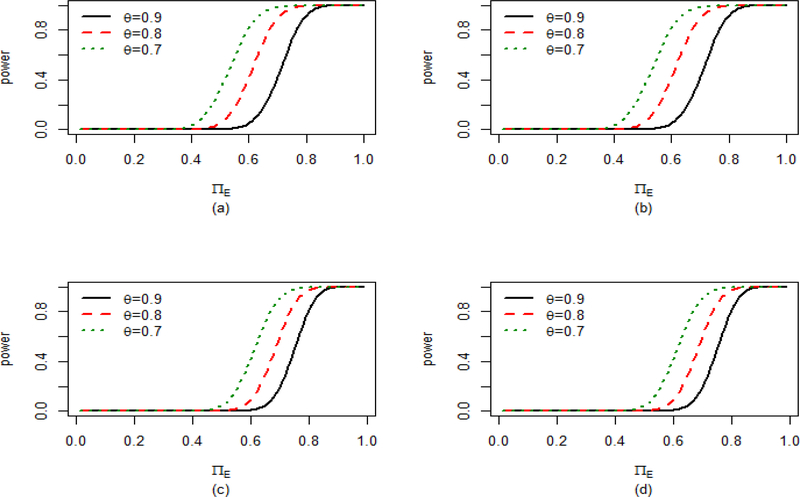

4. Sample Size Tables for the Non-Inferiority Testing

Before going to the sample size calculation we generate the power curves under both the conditional and marginal approaches to get an idea about the operating characteristics of the proposed methods. In Figure 4, we plot the power curves corresponding to three different values of θ : 0.9, 0.8 and 0.7 for RR and OR. The power curves for NNT can be similarly obtained but not shown. The three values of θ correspond to f = −0.1, −0.2 and −0.3 respectively, which correspond to the three choices of the NI margin. This implies that the experimental drug, in comparison to placebo, must achieve at least 90%, 80% and 70% respectively of the effect of the active control with respect to the placebo in order to be noninferior. From Figure 4, we observe that as θ decreases, the power curve becomes steeper which means for smaller θ the proposed test is more powerful than that for higher θ. This makes sense as for smaller θ (or larger f) it is easier to declare NI of the experimental drug over the reference, since in that case the new drug has to preserve smaller proportion of the control drug in the current trial in order to be non-inferior.

Figure 4:

Power curves for different θ under (a) RR Conditional, (b) RR marginal, (c) OR Conditional and (d) OR Marginal approaches keeping πR = 0.7 and πP = 0.1

Next we refer to the Sections 3.1.1 and 3.2.1 for the sample size determination under our proposed marginal and the conditional approach respectively. As discussed earlier, sample sizes in the placebo, reference and the experimental arms are denoted by n, r1n and r2n respectively, with r1, r2 ≥ 1. To compute (nE, nR, nP ), we consider three possible allocations for (P, R, E): (1 : 1 : 1), (1 : 2 : 2) and (1 : 2 : 3) of the total sample size N. Hence, for the allocation (1 : 1 : 1), r1 = r2 = 1, for (1 : 2 : 2), r1 = r2 = 2 and for (1 : 2 : 3) the values are r1 = 2 and r2 = 3. The power expression of the proposed conditional approach does not give an explicit solution for nP and hence an iterative process is needed. We determine the sample size under the two approaches for θ = 0.8 and 0.7 for (πR = 0.7, πP = 0.1) and (πR = 0.6, πP = 0.55). For NNT since we are considering ϵ −substantial non-inferiority, we choose ϵ = 0.05 which is equivalent to treating an additional 20 patients in order to see the benefit of the experimental drug; that is, to declare NI of E over R. We present the sample size for RR in Table 1, for OR in Table 2 and for NNT in Table 3.

Table 1:

Sample Size for RR to Achieve a Power of 80 % for θ = 0.8 and θ = 0.7, α = 0.025 and πE ϵ [0.65, 0.9] under Three Different Allocations. The simulated power (SimP) is also reported to show that calculated sample size is adequate to guarantee 80% power except for minor numerical fluctuation.

| Allocation | πR = 0.7, πP = 0.1 | πR = 0.6, πP = 0.55 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional | Marginal | Conditional | Marginal | |||||||||||||

| P | R | E | θ | πE | nP | N | SimP | nP | N | SimP | nP | N | SimP | nP | N | SimP |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 27 | 81 | 0.874 | 27 | 81 | 0.876 | 40 | 120 | 0.977 | 43 | 129 | 0.909 |

| 0.85 | 33 | 99 | 0.874 | 33 | 99 | 0.883 | 55 | 165 | 0.958 | 58 | 174 | 0.873 | ||||

| 0.8 | 42 | 126 | 0.877 | 42 | 126 | 0.870 | 82 | 246 | 0.944 | 86 | 258 | 0.857 | ||||

| 0.75 | 56 | 168 | 0.879 | 56 | 168 | 0.869 | 136 | 408 | 0.927 | 141 | 423 | 0.836 | ||||

| 0.7 | 79 | 237 | 0.878 | 79 | 237 | 0.857 | 278 | 834 | 0.899 | 286 | 858 | 0.812 | ||||

| 0.65 | 124 | 372 | 0.882 | 124 | 372 | 0.846 | 909 | 2727 | 0.877 | 915 | 2745 | 0.808 | ||||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 24 | 72 | 0.865 | 24 | 72 | 0.887 | 38 | 114 | 0.969 | 39 | 117 | 0.904 | |||

| 0.85 | 28 | 84 | 0.854 | 28 | 84 | 0.898 | 52 | 156 | 0.949 | 53 | 159 | 0.870 | ||||

| 0.8 | 33 | 99 | 0.857 | 33 | 99 | 0.894 | 76 | 228 | 0.934 | 77 | 231 | 0.848 | ||||

| 0.75 | 40 | 120 | 0.862 | 40 | 120 | 0.888 | 124 | 372 | 0.912 | 125 | 375 | 0.838 | ||||

| 0.7 | 51 | 153 | 0.873 | 51 | 153 | 0.884 | 245 | 735 | 0.894 | 247 | 741 | 0.813 | ||||

| 0.65 | 68 | 204 | 0.875 | 68 | 204 | 0.872 | 734 | 2202 | 0.871 | 737 | 2211 | 0.813 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 17 | 85 | 0.807 | 17 | 85 | 0.788 | 22 | 110 | 0.977 | 22 | 110 | 0.906 |

| 0.85 | 21 | 105 | 0.830 | 21 | 105 | 0.827 | 30 | 150 | 0.961 | 30 | 150 | 0.874 | ||||

| 0.8 | 27 | 135 | 0.854 | 27 | 135 | 0.863 | 44 | 220 | 0.935 | 44 | 220 | 0.852 | ||||

| 0.75 | 35 | 175 | 0.859 | 35 | 175 | 0.879 | 73 | 365 | 0.923 | 73 | 365 | 0.841 | ||||

| 0.7 | 49 | 245 | 0.871 | 49 | 245 | 0.873 | 147 | 735 | 0.906 | 148 | 740 | 0.833 | ||||

| 0.65 | 76 | 380 | 0.884 | 76 | 380 | 0.862 | 470 | 2350 | 0.876 | 471 | 2355 | 0.818 | ||||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 17 | 85 | 0.809 | 17 | 85 | 0.813 | 21 | 105 | 0.957 | 21 | 105 | 0.905 | |||

| 0.85 | 19 | 95 | 0.805 | 19 | 95 | 0.835 | 29 | 145 | 0.943 | 29 | 145 | 0.886 | ||||

| 0.8 | 23 | 115 | 0.835 | 23 | 115 | 0.868 | 42 | 210 | 0.922 | 42 | 210 | 0.864 | ||||

| 0.75 | 28 | 140 | 0.825 | 28 | 140 | 0.889 | 68 | 340 | 0.906 | 68 | 340 | 0.839 | ||||

| 0.7 | 35 | 175 | 0.845 | 35 | 175 | 0.898 | 133 | 665 | 0.888 | 133 | 665 | 0.824 | ||||

| 0.65 | 47 | 235 | 0.866 | 47 | 235 | 0.898 | 395 | 1975 | 0.877 | 395 | 1975 | 0.814 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 15 | 90 | 0.787 | 15 | 90 | 0.771 | 18 | 108 | 0.983 | 19 | 114 | 0.934 |

| 0.85 | 18 | 108 | 0.822 | 18 | 108 | 0.807 | 25 | 150 | 0.974 | 25 | 150 | 0.890 | ||||

| 0.8 | 23 | 138 | 0.849 | 23 | 138 | 0.848 | 36 | 216 | 0.959 | 37 | 222 | 0.872 | ||||

| 0.75 | 30 | 180 | 0.854 | 30 | 180 | 0.867 | 60 | 360 | 0.952 | 60 | 360 | 0.839 | ||||

| 0.7 | 42 | 252 | 0.874 | 42 | 252 | 0.884 | 120 | 720 | 0.937 | 121 | 726 | 0.832 | ||||

| 0.65 | 64 | 384 | 0.894 | 64 | 384 | 0.875 | 381 | 2286 | 0.914 | 382 | 2292 | 0.817 | ||||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 14 | 84 | 0.767 | 14 | 84 | 0.760 | 18 | 108 | 0.976 | 18 | 108 | 0.929 | |||

| 0.85 | 17 | 102 | 0.813 | 17 | 102 | 0.818 | 24 | 144 | 0.963 | 24 | 144 | 0.894 | ||||

| 0.8 | 20 | 120 | 0.820 | 20 | 120 | 0.852 | 34 | 204 | 0.941 | 34 | 204 | 0.872 | ||||

| 0.75 | 24 | 144 | 0.807 | 24 | 144 | 0.878 | 55 | 330 | 0.928 | 55 | 330 | 0.851 | ||||

| 0.7 | 31 | 186 | 0.829 | 31 | 186 | 0.899 | 108 | 648 | 0.913 | 108 | 648 | 0.830 | ||||

| 0.65 | 41 | 246 | 0.868 | 41 | 246 | 0.914 | 318 | 1908 | 0.897 | 318 | 1908 | 0.817 | ||||

Table 2:

Sample Size for OR to Achieve a Power of 80 % for θ = 0.8 and θ = 0.7, α = 0.025 and πE ϵ [0.65, 0.9] under Three Different Allocations. The simulated power (SimP) is also reported to show that calculated sample size is adequate to guarantee 80% power except for minor numerical fluctuation.

| Allocation | πR = 0.7, πP = 0.1 | πR = 0.6, πP = 0.55 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional | Marginal | Conditional | Marginal | |||||||||||||

| P | R | E | θ | πE | nP | N | SimP | nP | N | SimP | nP | N | SimP | nP | N | SimP |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 20 | 60 | 0.801 | 20 | 60 | 0.801 | 20 | 60 | 0.862 | 21 | 63 | 0.819 |

| 0.85 | 31 | 93 | 0.794 | 31 | 93 | 0.794 | 32 | 96 | 0.838 | 34 | 102 | 0.793 | ||||

| 0.8 | 49 | 147 | 0.796 | 49 | 147 | 0.796 | 54 | 162 | 0.824 | 57 | 171 | 0.782 | ||||

| 0.75 | 85 | 255 | 0.804 | 85 | 255 | 0.804 | 102 | 306 | 0.824 | 107 | 321 | 0.783 | ||||

| 0.7 | 165 | 495 | 0.809 | 165 | 495 | 0.809 | 232 | 696 | 0.819 | 241 | 723 | 0.788 | ||||

| 0.65 | 415 | 1245 | 0.8054 | 415 | 1245 | 0.805 | 844 | 2532 | 0.809 | 853 | 2559 | 0.798 | ||||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 15 | 45 | 0.800 | 15 | 45 | 0.800 | 19 | 57 | 0.858 | 20 | 60 | 0.831 | |||

| 0.85 | 21 | 63 | 0.791 | 21 | 63 | 0.791 | 30 | 90 | 0.836 | 31 | 93 | 0.805 | ||||

| 0.8 | 30 | 90 | 0.807 | 30 | 90 | 0.808 | 51 | 153 | 0.828 | 52 | 156 | 0.795 | ||||

| 0.75 | 45 | 135 | 0.800 | 45 | 135 | 0.801 | 93 | 279 | 0.819 | 95 | 285 | 0.790 | ||||

| 0.7 | 72 | 216 | 0.806 | 72 | 216 | 0.806 | 205 | 615 | 0.816 | 209 | 627 | 0.792 | ||||

| 0.65 | 125 | 375 | 0.805 | 125 | 375 | 0.805 | 681 | 2043 | 0.806 | 686 | 2058 | 0.796 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 11 | 55 | 0.808 | 11 | 55 | 0.808 | 11 | 55 | 0.849 | 11 | 55 | 0.829 |

| 0.85 | 16 | 80 | 0.808 | 16 | 80 | 0.808 | 17 | 85 | 0.834 | 18 | 90 | 0.809 | ||||

| 0.8 | 26 | 130 | 0.804 | 26 | 130 | 0.804 | 29 | 145 | 0.826 | 30 | 150 | 0.796 | ||||

| 0.75 | 45 | 225 | 0.801 | 45 | 225 | 0.801 | 54 | 270 | 0.823 | 55 | 275 | 0.798 | ||||

| 0.7 | 87 | 435 | 0.803 | 87 | 435 | 0.803 | 122 | 610 | 0.815 | 124 | 620 | 0.792 | ||||

| 0.65 | 220 | 1100 | 0.806 | 220 | 1100 | 0.806 | 434 | 2170 | 0.801 | 437 | 2185 | 0.790 | ||||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 8 | 40 | 0.801 | 8 | 40 | 0.799 | 10 | 50 | 0.830 | 10 | 50 | 0.827 | |||

| 0.85 | 12 | 60 | 0.818 | 12 | 60 | 0.818 | 17 | 85 | 0.829 | 17 | 85 | 0.825 | ||||

| 0.8 | 17 | 85 | 0.809 | 17 | 85 | 0.809 | 28 | 140 | 0.822 | 28 | 140 | 0.817 | ||||

| 0.75 | 26 | 130 | 0.789 | 26 | 130 | 0.789 | 50 | 250 | 0.807 | 50 | 250 | 0.801 | ||||

| 0.7 | 41 | 205 | 0.817 | 41 | 205 | 0.817 | 110 | 550 | 0.803 | 110 | 550 | 0.797 | ||||

| 0.65 | 71 | 355 | 0.810 | 71 | 355 | 0.810 | 362 | 1810 | 0.799 | 362 | 1810 | 0.796 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 9 | 54 | 0.809 | 9 | 54 | 0.809 | 9 | 54 | 0.859 | 9 | 54 | 0.837 |

| 0.85 | 13 | 78 | 0.831 | 13 | 78 | 0.831 | 14 | 84 | 0.831 | 14 | 84 | 0.803 | ||||

| 0.8 | 22 | 132 | 0.809 | 22 | 132 | 0.809 | 23 | 138 | 0.822 | 24 | 144 | 0.795 | ||||

| 0.75 | 37 | 222 | 0.792 | 37 | 222 | 0.792 | 43 | 258 | 0.816 | 44 | 264 | 0.789 | ||||

| 0.7 | 72 | 432 | 0.806 | 72 | 432 | 0.806 | 98 | 588 | 0.819 | 99 | 594 | 0.793 | ||||

| 0.65 | 182 | 1092 | 0.804 | 182 | 1092 | 0.804 | 349 | 2094 | 0.808 | 352 | 2112 | 0.796 | ||||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 7 | 42 | 0.811 | 7 | 42 | 0.811 | 8 | 48 | 0.804 | 8 | 48 | 0.806 | |||

| 0.85 | 10 | 60 | 0.797 | 10 | 60 | 0.797 | 13 | 78 | 0.804 | 13 | 78 | 0.803 | ||||

| 0.8 | 14 | 84 | 0.803 | 14 | 84 | 0.803 | 22 | 132 | 0.806 | 22 | 132 | 0.799 | ||||

| 0.75 | 22 | 132 | 0.807 | 22 | 132 | 0.807 | 40 | 240 | 0.809 | 40 | 240 | 0.804 | ||||

| 0.7 | 34 | 204 | 0.807 | 34 | 204 | 0.807 | 88 | 528 | 0.809 | 88 | 528 | 0.804 | ||||

| 0.65 | 60 | 360 | 0.827 | 60 | 360 | 0.827 | 289 | 1734 | 0.801 | 289 | 1734 | 0.796 | ||||

Table 3:

Sample Size for NNT to Achieve a Power of 80 % for θ = 0.8 and θ = 0.7, ϵ = 0.05, α = 0.025 and πE ϵ [0.65, 0.9] under Three Different Allocations. The simulated power (SimP) is also reported to show that calculated sample size is adequate to guarantee 80% power except for minor numerical fluctuation.

| Allocation | πR = 0.7, πP = 0.1 | πR = 0.6, πP = 0.55 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional | Marginal | Conditional | Marginal | |||||||||||||

| P | R | E | θ | πE | nP | N | SimP | nP | N | SimP | nP | N | SimP | nP | N | SimP |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 35 | 105 | 0.809 | 35 | 105 | 0.809 | 38 | 114 | 0.858 | 41 | 123 | 0.829 |

| 0.85 | 55 | 165 | 0.820 | 55 | 165 | 0.820 | 61 | 183 | 0.844 | 65 | 195 | 0.820 | ||||

| 0.8 | 95 | 285 | 0.812 | 95 | 285 | 0.812 | 109 | 327 | 0.833 | 115 | 345 | 0.804 | ||||

| 0.75 | 195 | 585 | 0.812 | 195 | 585 | 0.812 | 238 | 714 | 0.823 | 247 | 741 | 0.807 | ||||

| 0.7 | 584 | 1752 | 0.802 | 584 | 1752 | 0.802 | 837 | 2511 | 0.807 | 846 | 2538 | 0.800 | ||||

| 0.65 | 7248 | > 104 | 0.804 | 7248 | > 104 | 0.804 | > 104 | > 104 | - | > 104 | > 104 | - | ||||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 22 | 66 | 0.800 | 22 | 66 | 0.800 | 36 | 108 | 0.870 | 37 | 111 | 0.832 | |||

| 0.85 | 32 | 96 | 0.793 | 32 | 96 | 0.793 | 56 | 168 | 0.843 | 58 | 174 | 0.818 | ||||

| 0.8 | 49 | 147 | 0.799 | 49 | 147 | 0.799 | 99 | 297 | 0.831 | 101 | 303 | 0.804 | ||||

| 0.75 | 82 | 246 | 0.813 | 82 | 246 | 0.813 | 209 | 627 | 0.820 | 213 | 639 | 0.812 | ||||

| 0.7 | 161 | 483 | 0.806 | 161 | 483 | 0.806 | 674 | 2022 | 0.805 | 679 | 2037 | 0.798 | ||||

| 0.65 | 431 | 1293 | 0.799 | 431 | 1293 | 0.799 | > 104 | > 104 | - | > 104 | > 104 | - | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 18 | 90 | 0.813 | 18 | 90 | 0.813 | 21 | 105 | 0.866 | 21 | 105 | 0.825 |

| 0.85 | 28 | 140 | 0.800 | 28 | 140 | 0.800 | 33 | 165 | 0.852 | 34 | 170 | 0.832 | ||||

| 0.8 | 48 | 240 | 0.808 | 48 | 240 | 0.808 | 58 | 290 | 0.831 | 59 | 295 | 0.811 | ||||

| 0.75 | 99 | 495 | 0.813 | 99 | 495 | 0.813 | 126 | 630 | 0.823 | 127 | 635 | 0.807 | ||||

| 0.7 | 295 | 1475 | 0.813 | 295 | 1475 | 0.813 | 432 | 2160 | 0.806 | 434 | 2170 | 0.795 | ||||

| 0.65 | 3660 | > 104 | 0.799 | 3660 | > 104 | 0.799 | > 104 | > 104 | - | > 104 | > 104 | - | ||||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 12 | 60 | 0.791 | 12 | 60 | 0.791 | 20 | 100 | 0.856 | 20 | 100 | 0.834 | |||

| 0.85 | 17 | 85 | 0.798 | 17 | 85 | 0.798 | 31 | 155 | 0.832 | 31 | 155 | 0.822 | ||||

| 0.8 | 26 | 130 | 0.797 | 26 | 130 | 0.797 | 54 | 270 | 0.824 | 54 | 270 | 0.815 | ||||

| 0.75 | 42 | 210 | 0.801 | 42 | 210 | 0.801 | 113 | 565 | 0.811 | 113 | 565 | 0.806 | ||||

| 0.7 | 83 | 415 | 0.8173 | 83 | 415 | 0.817 | 360 | 1800 | 0.807 | 360 | 1800 | 0.803 | ||||

| 0.65 | 221 | 1105 | 0.805 | 221 | 1105 | 0.805 | 6848 | > 104 | 0.799 | 6848 | > 104 | 0.799 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 15 | 90 | 0.803 | 15 | 90 | 0.803 | 17 | 102 | 0.860 | 18 | 108 | 0.841 |

| 0.85 | 23 | 138 | 0.806 | 23 | 138 | 0.806 | 27 | 162 | 0.856 | 28 | 168 | 0.833 | ||||

| 0.8 | 39 | 234 | 0.823 | 39 | 234 | 0.823 | 48 | 288 | 0.849 | 48 | 288 | 0.818 | ||||

| 0.75 | 79 | 474 | 0.821 | 79 | 474 | 0.821 | 102 | 612 | 0.815 | 104 | 624 | 0.807 | ||||

| 0.7 | 235 | 1410 | 0.809 | 235 | 1410 | 0.809 | 350 | 2100 | 0.811 | 352 | 2112 | 0.805 | ||||

| 0.65 | 2903 | > 104 | 0.794 | 2903 | > 104 | 0.794 | 12809 | > 104 | 0.801 | 12809 | > 104 | 0.801 | ||||

| 0.7 | 0.9 | 9 | 54 | 0.803 | 9 | 54 | 0.803 | 16 | 96 | 0.844 | 17 | 102 | 0.852 | |||

| 0.85 | 13 | 78 | 0.812 | 13 | 78 | 0.812 | 26 | 156 | 0.849 | 26 | 156 | 0.833 | ||||

| 0.8 | 20 | 120 | 0.820 | 20 | 120 | 0.820 | 44 | 264 | 0.821 | 44 | 264 | 0.812 | ||||

| 0.75 | 33 | 198 | 0.806 | 33 | 198 | 0.806 | 92 | 552 | 0.819 | 92 | 552 | 0.811 | ||||

| 0.7 | 64 | 384 | 0.808 | 64 | 384 | 0.808 | 290 | 1740 | 0.800 | 291 | 1746 | 0.805 | ||||

| 0.65 | 172 | 1032 | 0.801 | 172 | 1032 | 0.801 | 5508 | > 104 | 0.794 | 5508 | > 104 | 0.795 | ||||

We present the sample sizes for the placebo arm only in the tables, however those for the arms R and E can be obtained by multiplying it with the allocation ratios. The total sample size for the allocation (1 : 1 : 1) is ; that for (1 : 2 : 2) is ; while for (1 : 2 : 3) it is , where , and are the respective sample size for the placebo arm under the three different allocations. From all three tables we observe that the sample size under the conditional approach is smaller or at most equal to that calculated under the marginal approach to achieve a power of 80%. It is clear from Tables 1, 2 and 3 that the two approaches behave nearly identically when πR >> πP. However, when their difference is smaller, conditional approach tends to improve power for fixed sample size. Also we observe that the sample size requirement decreases with decrease in θ for a fixed power, which is consistent to the power curve plots. For NNT we observe that the sample size requirement is bigger as compared to those for RR and OR since we test for ϵ-substantial non-inferiority (ϵ > 0) and hence for fixed θ, the margin allowance for NNT is smaller than that for RR and OR.

Although appealing at first glance, one may not want to use a balanced study design in the NI context from two aspects: (i) due to ethical reasons in case an effective treatment exists, the number of patients receiving the placebo should be kept as small as possible, and (ii) as pointed out by Koch and Tangen (1999), the difference between E and R should be expected to be much smaller than the difference of both of them relative to placebo so that the latter ones are easier to detect. As observed by Pigeot et al. (2003) for continuous outcome, the necessary sample size required for the unbalanced allocations is remarkably smaller compared to the balanced one. We observe similar results for the sample size under NNT from Table 3. From Table 2 for OR we notice that the necessary sample size is remarkably smaller for the unbalanced allocation (1 : 2 : 2) as compared to a balanced design (1 : 1 : 1) and a minor reduction is again obtained for the unbalanced allocation (1 : 2 : 3) as compared to (1 : 2 : 2). However, for RR the sample sizes do not follow the same pattern, particularly when the difference between πR and πP is large, with respect to the allocation, as can be seen from Table 1. Apart from the difference in the functional form, this might also be due to the fact that even after logarithmic transformation of RR it still yields a somewhat skewed distribution that do not conform to the normal approximation quite well as compared to OR or NNT.

5. Application

We illustrate our proposed Frequentist methods for RR, OR and NNT with a published dataset from a three-arm comparative study on major depressive disorder. This dataset is described in Higuchi et al. (2009). Hida and Tango (2011) as well as Ghosh et al. (2016) also considered this specific dataset in their paper. Hida and Tango (2013) proposed a Frequentist’s version of the problem for binary outcomes and Ghosh et al. (2018) considered the Bayesian version of the same for risk difference. The objective of the depression trial was to compare the efficacy and safety of duloxetine (E) with those of paroxetine (R) and placebo (P). This study was a double-blinded, randomized, parallel-group active-controlled study of a six-week treatment with the following number of patients in each arm: duloxetine (nE = 147), paroxetine (nR = 148) and placebo (nP = 145). The primary endpoint was continuous type which is the change in HAMD-17 total score from baseline at the end of sixth week. Hida and Tango (2011) considered two binary outcomes for their Frequentist approach namely, Response and Remission. Response is the primary outcome defined as the reduction of more than 50% total. Remission is the secondary outcome which is defined as maintaining HAMD-17 score of ≤ 17 at the end of 6 weeks. We present the data in Table 2, in terms of Response and Remission. We analyze both the Response and Remission outcomes separately using our proposed approach. To make a meaningful interpretation of the effect of the experimental drug, a clinically acceptable margin reflecting the largest loss of effect is chosen to determine non-inferiority of the experimental drug over the control. Here, we vary θ in the range [0.5, 0.8] to explore different possibilities. For the marginal approach the p−value of the test for NNT and for Margin 2 of both RR and OR is calculated as

| (5.1) |

where is the Frequentist’s statistic under the existing approach and under null hypothesis. The quantity ϵ is chosen to be 0.05 for the analysis under NNT, while ϵ = 0 for RR and OR. For the conditional Frequentist approach we calculate the p−value as

| (5.2) |

where is the Frequentist’s test statistic for the conditional testing and and are the mean and variance of W under null hypothesis as given in Section 3. The Frequentist p−values are reported in Table 5 and Table 6 for RR, OR and NNT for the Response and the Remission data respectively.

Table 5:

Frequentist p-values for the Response Data

| RR | OR | NNT (ϵ = 0.05) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ | Conditional | Marginal | Conditional | Marginal | Conditional | Marginal |

| 0.5 | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.227 | 0.227 |

| 0.55 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.272 | 0.272 |

| 0.6 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0.072 | 0.073 | 0.320 | 0.321 |

| 0.65 | 0.094 | 0.094 | 0.094 | 0.095 | 0.372 | 0.374 |

| 0.7 | 0.119 | 0.119 | 0.122 | 0.123 | 0.426 | 0.428 |

| 0.75 | 0.149 | 0.150 | 0.155 | 0.157 | 0.479 | 0.482 |

| 0.8 | 0.186 | 0.187 | 0.193 | 0.195 | 0.532 | 0.535 |

Table 6:

Frequentist p-values for the Remission Data

| RR | OR | NNT (ϵ = 0.05) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ | Conditional | Marginal | Conditional | Marginal | Conditional | Marginal |

| 0.5 | 0.085 | 0.085 | 0.080 | 0.080 | 0.379 | 0.38 |

| 0.55 | 0.101 | 0.101 | 0.099 | 0.099 | 0.424 | 0.426 |

| 0.6 | 0.121 | 0.121 | 0.121 | 0.121 | 0.470 | 0.473 |

| 0.65 | 0.146 | 0.146 | 0.147 | 0.148 | 0.516 | 0.519 |

| 0.7 | 0.174 | 0.175 | 0.177 | 0.179 | 0.559 | 0.564 |

| 0.75 | 0.207 | 0.209 | 0.212 | 0.215 | 0.601 | 0.606 |

| 0.8 | 0.245 | 0.248 | 0.245 | 0.254 | 0.640 | 0.645 |

The respective p−values are compared with α = 0.025 to deduce the final decision. From both Table 5 and Table 6, we observe that p−values decrease as θ decreases implying greater chance of declaring NI for smaller values of θ, since p − value < α implies rejection of NI. Also we observe that the p−values under the conditional approach is smaller or at most equal to that under the marginal approach which is consistent to the sample size calculation under all three functionals. However, since none of the p−values is smaller that α = 0.025 NI null hypothesis can not be rejected and hence NI can not be claimed for any of the tests across any θ for all the functionals.

6. Discussion

In this paper we have presented fraction margin based Frequentist test procedures for the “gold standard” three-arm NI trial which includes a placebo arm for binary endpoints with RR, OR and NNT type functionals. This is an important methodological contribution in view of the recent FDA guideline. We also introduced a conditional test of NI. For both RR and OR, we showed the non-uniqueness of the NI margin and constructed two examples of that. We made a comparison among them to identify the one yielding better operating characteristic. Additional guidance is required from regulators if one plans to choose a unique NI margin for all situation. We also note that NI testing for NNT can be regarded as the -substantial NI testing under the risk difference case. We tabulated the sample size under three different types of allocation for RR, OR and NNT, which should provide a good starting point for accessing sample size when designing such trials. We also note that the tests based on asymptotic approximation perform favorably since usually in NI testing the number of patients in each treatment arm is moderately large. In case of small sample size exact method of NI testing can be developed using Fisher’s exact test following Wellek (2005), Hasselblad and Lokhnygina (2007) and Zaslavsky (2013). However, all of these articles presented the exact approach for two-arm NI testing and most of them considered NI testing for rate difference as the function of interest only. To the best of our knowledge there exists no published work on exact testing approach for three-arm NI trial and hence this should be considered as an important future work. Also as suggested by one reviewer, likelihood ratio test or score test are potential alternatives to the asymptotic tests.

Historical information plays substantial role in the design and analysis of NI trial. Hence NI trial has to be reflected in several substantive aspects, for e.g. the choice of δ, the question of whether a placebo can be included as an additional arm of the study, assay sensitivity, etc. From the sample size tables we have observed that the proposed conditional test yields identical power and hence sample size as that of the marginal test when the active control is substantially superior to placebo. However, when the control is marginally superior to placebo, the proposed conditional approach yields smaller sample size as compared to the marginal approach for a fixed power. Also analysis of our clinical trial data suggest that both the methods perform comparably in all situations, however, the p−values under the conditional approach are always found to be smaller or at most equal to that obtained under the marginal one. This essentially supports the observation we made in the difference of sample size quantification between the two methods. Also we note that although in this article we considered sample size allocation motivated by Pigeot et al. (2003) and Koch and Tangen (1999), one may also consider optimal allocation to treatment arms following the line of Singer (2001) and Pigeot et al. (2003) for continuous outcome. However, when the outcome is binary, derivation of optimal allocation formula for various functional forms still remains an open problem.

We note that under the fraction margin approach the fraction “f” is pre-specified, while the NI margin δ is unknown. Hence the value of δ can vary greatly depending on the estimated effect size of the reference treatment, i.e. as a function of . As evident, the information gained from the historical trial/s may play a significant role in NI trial design and hierarchical Bayesian approach may provide an attractive framework to achieve this. In this article we restricted ourselves to the Frequentist approach only, but that is definitely an avenue worth exploring in future. On the other hand in the fixed margin approach (see Hida and Tango (2013) and Ghosh et al. (2018)), with three-arms, the joint testing of NI and AS may be performed which needs additional care since it may produce conservative test with restrictive type-I error (Chuang-Stein et al., 2007; Dmitrienko et al., 2009) under intersection-union test. Albeit development of such procedure for RR, OR and NNT under alternative definition of type-I error (e.g. average testing error of Chuang-Stein et al. (2007)) is another interesting open problem.

Supplementary Material

Table 4:

Remission and Response as Outcome in the Depression Trial of Higuchi et al. (2009)

| Outcome | Duloxetine | Paroxetine | Placebo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remission | 50 | 49 | 32 |

| Response | 80 | 78 | 56 |

| Total | nE = 147 | nR = 148 | nP = 145 |

Acknowledgements

The research of last author is partly supported by PCORI contract number ME-1409–21410 and NIH grant number P30-ES020957.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

For proofs and additional results please see the supplementary material.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.(2005). Guideline on the choice of the noninferiority margin (Doc. Ref. EMEA/CPMP/EWP/215). EMA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(2016). Non-Inferiority Clinical Trials to Establish Effectiveness Guidance for Industry. FDA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Althunian TA, de Boer A, Klungel OH, Insani WN, and Groenwold RH (2017). Methods of defining the non-inferiority margin in randomized, double-blind controlled trials: a systematic review. Trials, 18(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown D, Volkers P, and Day S (2006). An introductory note to chmp guidelines: choice of the non-inferiority margin and data monitoring committees. Statistics in Medicine, 25(10):1623–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuang-Stein C, Stryszak P, Dmitrienko A, and Offen W (2007). Challenge of multiple co-primary endpoints: a new approach. Statistics in Medicine, 26(6):1181–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook R and Sackett DL (1995). The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. Biometrical Journal, 310(6977):452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Agostino RB, Massaro JM, and Sullivan LM (2003). Noninferiority trials: Design concepts and issues-the encounters of academic consultants in statistics. Statistics in Medicine, 22(2):169–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dmitrienko A, Tamhane AC, and Bretz F (2009). Multiple testing problems in pharmaceutical statistics. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamalo MA, Wu R, and Tiwari RC (2011). Bayesian approach to noninferiority trials for proportions. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 21(5):902–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh S, Ghosh S, and Tiwari RC (2016). Bayesian approach for assessing non-inferirity in a three-arm trial with pre-specified margin. Statistics in Medicine, 35(5):695–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh S, Tiwari RC, and Ghosh S (2018). Bayesian approach for assessing noninferiority in a three-arm trial with binary endpoint. Pharmaceutical statistics, 17(4):342–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashemi L, Nandram B, and Goldberg R (1997). Bayesian analysis for a single 2× 2 table. Statistics in Medicine, 16:1311–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasselblad V and Lokhnygina Y (2007). Tests for 2 × 2 tables in clinical trials. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 6(2):456–468. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hida E and Tango T (2011). On the three-arm noninferiority trial including a placebo with a prespecified margin. Statistics in Medicine, 30(3):224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hida E and Tango T (2013). Three-arm noninferiority trials with a prespecified margin for inference of the difference in the proportions of binary endpoints. Journal of biopharmaceutical statistics, 23(4):774–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higuchi T, Murasaki M, and Kamijima K (2009). Clinical evaluation of duloxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder-placebo and paroxetine-controlled double-blinded comparative study. Japaneese Journ of Clinical Psychopharmocology, 12:1613–1634. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilton JF (2010). Noninferiority trial designs for odds ratios and risk differences. Statistics in Medicine, 29:982–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang L, Zalkikar J, and Tiwari RC (2011). A likelihood ratio test based method for signal detection with application to fda’s drug safety data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 106(496):1230–1241. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung HMJ and Wang SJ (2004). Multiple testing of noninferiority hypotheses in active controlled trials. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 14(2):327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ICHE10 (2009). ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Choice of Control Group and Related Issues in Clinical Trials. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. [Google Scholar]

- 21.ICHE9 (2009). ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keefe R, Kraemer HC, Epstein RS, Frank E, Ginger H, Laughren TP, Mcnulty J, Reed SD, Sanchez J, and Leon AC (2013). Defining a clinically meaningful effect for the design and interpretation of randomized controlled trials. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(5–6 Suppl A):4S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kieser M and Friede T (2007). Planning and analysis of three-arm non-inferiority trials with binary endpoints. Statistics in medicine, 26(2):253–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kieser M and Stucke K (2016). Assessing additional benefit in noninferiority trials. Biometrical Journal. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koch GG and Tangen CM (1999). Non parametrc analysis of covaiance and its role in non-inferiority clinical trials. Drug Information Journal, 33:1145–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulldorff M (1997). A spatial scan statistic. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, 26(6):1481–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mielke M (2010). Maximum Likelihood Theory for Retention of Effect Non-Inferiority Trials. PhD thesis, Niedersächsische Staats-und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mielke M and Munk A (2009). The assessment and planning of non-inferiority trials for retention of effect hypotheses-towards a general approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:0912.4169.

- 29.Mutze T, Munk A, and Friede T (2015). Design and analysis of three-arm trials with negative binomially distributed endpoints. Statistics in Medicine, 35(4):505–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pigeot I, Schafer J, Rohmel J, and Hauschke D (2003). Assessing noninferiority of a new treatment in a three-arm clinical trial including a placebo. Statistics in Medicine, 22(6):883–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rousson V and Seifert B (2008). A mixed approach for proving non-inferiority in clinical trials with binary endpoints. Biometrical Journal, 2:190–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schumi J and Wittes JT (2011). Through the looking glass: understanding non-inferiority. Trials, 12(2):106–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer J (2001). A simple procedure to compute the sample size needed to compare two independent groups when the population variances are unequal. Statistics in medicine, 20(7):1089–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang N-S, Yu B, and Tang M-L (2014). Testing non-inferiority of a new treatment in three-arm clinical trials with binary endpoints. BMC medical research methodology, 14(1):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wangge G, Roes KC, de Boer A, Hoes AW, and Knol MJ (2013). The challenges of determining noninferiority margins: a case study of noninferiority randomized controlled trials of novel oral anticoagulants. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 185(3):222–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wellek S (2005). Statistical methods for the analysis of two-arm non-inferiority trials with binary outcomes. Biometrical Journal: Journal of Mathematical Methods in Biosciences, 47(1):48–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaslavsky BG (2013). Bayesian hypothess testing in two-arm trials with dichotomous outcomes. Biometrics, 69(1):157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.