Abstract

To elucidate the clinical outcomes of nonsurgical treatment for transcondylar fractures of the humerus.

From April 2010 to March 2018, 32 elbows with AO classification 13A-2.3 transcondylar fractures of the humerus (extra-articular fracture, metaphyseal simple, transverse, transmetaphyseal) in adult patients were treated in our hospital and related facilities. Fifteen of 32 elbows were treated nonsurgically by immobilization with a long-arm cast or splint. Of these, 14 elbows that were followed up for >3 months were investigated. The patients comprised 6 men and 8 women with a mean age at the time of injury of 78 years. We investigated the follow-up period, duration until bone union, complications at final follow-up, radiological evaluation, elbow range of motion (ROM), total elbow joint range (Arc), and clinical outcome (Mayo Elbow Performance Score [MEPS]).

The mean follow-up period was 8 months. The mean duration until bone union was 7 weeks. No significant complications were observed at the final examination. The ROM of the injured elbow joint was obtained in 13 patients. At the final follow-up, the mean extension and flexion of the injured elbow was −19.2° and 121.2°, respectively. The mean Arc of the injured elbow joint was 102.3°. Joint contracture (<120° flexion) was observed in 6 of the 13 elbows for which ROM was obtained. No patients complained of residual pain of the elbow joint. The mean MEPS was 93.1 points.

There is no objection to the fact that displaced transcondylar fractures of the humerus should be treated surgically. However, significant numbers of intraoperative and postoperative complications of plate osteosynthesis have been reported. Until recently, although few clinical reports regarding nonsurgical treatment for these fractures have been published, several studies have indicated that nonsurgical treatment might be an alternative option for these fractures caused by low-energy trauma. In this study, we presented the radiographic and clinical outcomes of nonsurgical treatment for transcondylar fractures of the humerus. Our study suggests that nonsurgical treatment can be a good option for transcondylar fractures of the humerus.

Keywords: adult, extra-articular fracture, humerus, nonoperative management, nonsurgical treatment, transcondylar fractures

1. Introduction

Distal humeral fractures are relatively uncommon injuries in adults with an incidence of 5.7 per 100,000 adults per year.[1,2] However, transcondylar fractures of the humerus occasionally occur secondary to low-energy trauma (e.g., falls) in patients of advanced age with osteoporotic bone. Transcondylar fractures of the humerus have a small contact area of the fracture surface and tend to be subject to rotational force to the distal bone fragment[3–6]; thus, surgical intervention is indicated in most cases to enable early postoperative mobilization and restore a pain-free and satisfactory level of elbow function.[1,7] Although various surgical procedures have been proposed, biomechanical studies indicate that double-plate osteosynthesis or single-plate osteosynthesis augmented a medial screw that provides adequate fracture stabilization.[8,9] Thus, open anatomic reduction of the displacement with plate osteosynthesis has been proposed as a standard treatment for transcondylar fractures of the humerus. However, significant numbers of intraoperative and postoperative complications associated with plate osteosynthesis have also been reported.[1,7] On the other hand, several studies have indicated that nonsurgical treatment might be an alternative option for displaced transcondylar fractures of the humerus caused by low-energy trauma.[1,10,11] In this study, we present the radiographic and clinical outcomes of nonsurgical treatment for transcondylar fractures of the humerus and discuss which cases can be preserved and treated.

2. Materials and methods

This retrospective case series was performed at our institute and related hospitals. The patients’ characteristics, medical history, imaging findings, and follow-up data were extracted from their medical records. This study was conducted in conformity with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki after approval was obtained from our institutional review board (Nos. 30-12-1048, 450-30-21). Informed consent for the treatment and publication was obtained from all patients in this study.

From April 2010 to March 2019, 36 elbows with AO classification 13A-2 transcondylar fractures of the humerus (extra-articular fracture, metaphyseal simple) in adult patients were treated in our hospital and related facilities. Of these 36 elbows, 32 had AO classification 13-A2.3 fractures (transverse, transmetaphyseal). Seventeen elbows were treated by osteosynthesis with a locking plate, and 15 elbows were treated by immobilization with a long-arm cast or splint. The nonsurgically treated transcondylar fractures were investigated in this study. The inclusion criteria were nonsurgical treatment of an AO classification 13-A2.3, transverse, transmetaphyseal fracture and a follow-up period of >3 months. The exclusion criteria were skeletal immaturity, pathologic fractures, and a follow-up period of <2 months after the initial treatment. Fourteen patients were included in this study, and their data are shown in Table 1. All patients had sustained low-energy trauma, and the mechanism of injury was a fall while walking. The patients comprised 6 men and 8 women, and the mean age at the time of injury was 78 years (range, 46–98 years). Five left and 9 right elbows were injured.

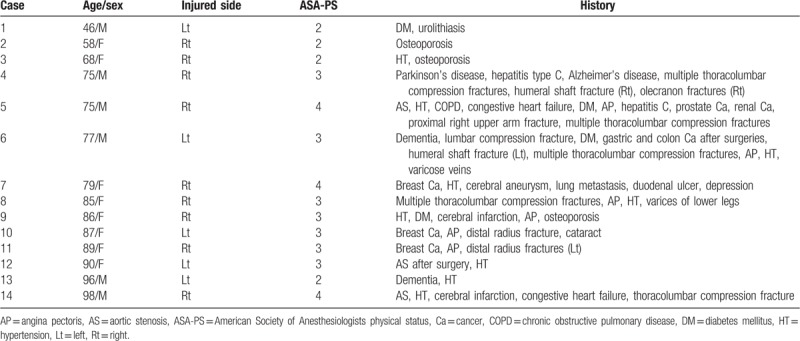

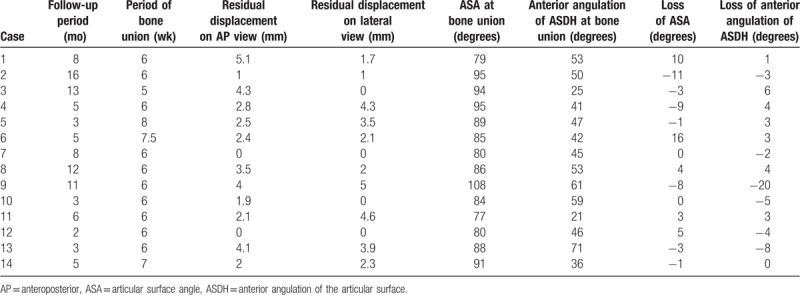

Table 1.

Data of adult patients with transcondylar fractures of the humerus.

Ten patients had cardiovascular complications, including aortic stenosis, angina pectoris, and cerebral infarction. Thirteen patients had osteoporosis, and 4 patients had dementia. According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system,[12,13] which is a system for assessing the physical status of patients into 1 of 6 categories before surgery, 4 patients were classified in category II, 7 in category III, and 3 in category IV.

At the initial diagnosis, the possibilities of complications of nonsurgical treatment, including nonunion, malunion, humerus deformity, and elbow joint contracture, were explained in detail, and surgical intervention was strongly recommended for all patients. However, all patients strongly desired nonsurgical treatment, and immobilization with long-arm splint or cast was performed.

Table 2 shows the period from injury to therapeutic intervention, direction of fracture displacement, initial displacement on radiographs, initial articular surface angle (ASA) on anteroposterior radiographs, and anterior angulation of the articular surface of the distal humerus (ASDH) on lateral radiographs.[14]

Table 2.

Period from injury to therapeutic intervention and findings of initial radiographic evaluation.

We investigated the follow-up period, duration until bone union (duration from application to removal of the cast or splint), complications, and radiological and clinical outcomes.

2.1. Nonsurgical treatment and rehabilitation

Nonsurgical treatment was performed for all patients at the outpatient clinic. A long-arm cast or splint with a sling was applied for fracture immobilization. The patient's arm was oriented with up to 90° of elbow flexion and a neutral forearm position. A fiberglass cast or splint was applied from immediately below the shoulder to the hand with restriction of forearm rotation. Between the initial immobilization and a month after the trauma, we have taken radiographs once a week and routinely exchanged the cast or splint every 2 weeks. From a month after the immobilization, we followed up and took radiographs every 2 weeks and the cast and splint was removed at 6 weeks after the immobilization. However, in 2 patients, a callus of the fracture site was not enough to remove the cast or splint and we have taken radiographs once a week and elongated the periods of the immobilization. The criteria for bone union were emergence of a callus on the anteroposterior and lateral radiographs and disappearance of tenderness at the fracture site. After confirmation of bone union, the cast or splint was removed and active range of motion exercises were encouraged.

2.2. Radiographic evaluation

Standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of each patient were taken at each consecutive examination. The patients’ forearms were always held in neutral rotation with the shoulders flexed or abducted and the elbows flexed to 90° while obtaining the anteroposterior and lateral radiographs. The radiographic evaluation involved measurement of the direction of fracture displacement, the degree of displacement, and deformity of the distal humerus. The direction of fracture displacement was classified into three types: nondisplacement (<2 mm), flexion-type displacement, and extension-type displacement. The degree of displacement was measured on anteroposterior and lateral radiographs at two time points: at the initial visit and at the time of bone union. To evaluate deformity of the distal humerus, the ASA and anterior angulation of the ASDH were measured on anteroposterior and lateral radiographs, respectively (Fig. 1a and b).[14] Both angles were measured at two time points: at the initial visit and at the time of bone union. The angle variation was calculated by subtracting the ASA and articular angulation of the ASDH at the time of bone union from those at the initial visit.

Figure 1.

Radiographic parameters on anteroposterior and lateral view of radiographs. (a) Articular surface angle (ASA). (b) Anterior angulation of articular surface of distal humerus (ASDH).

2.3. Clinical evaluation

The follow-up evaluation included measurement of range of motion (ROM) (measured with a goniometer), total elbow joint range (Arc), and clinical evaluation score (i.e., Mayo Elbow Performance Score [MEPS]).[15] The MEPS includes pain, Arc, stability of the elbow joint, and function related to activities of daily life (ADL). Elbow pain was classified as severe (presence of pain affecting ADL), moderate (presence of pain not affecting ADL), mild (absence of pain but presence of clicks), or absent (absence of pain).

3. Results

The mean follow-up period was 7.1 months (range, 3–16 months). No patients developed nonunion or delayed union, heterotopic ossification, neurovascular deficits, or skin complications.

3.1. Radiographic results

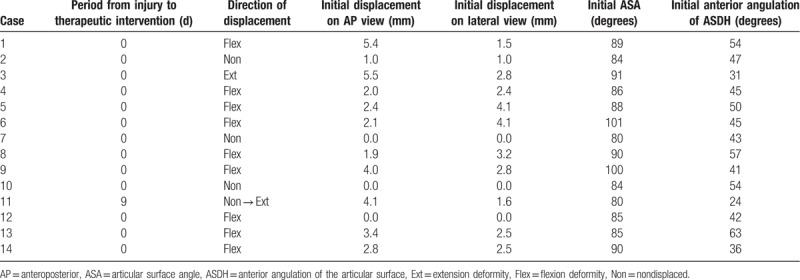

Table 3 shows the radiographically measured degree of residual displacement (mm) of the fractures at bone union, initial ASA and anterior angulation of the ASDH, and loss of the ASA and anterior angulation of the ASDH at the bone union. The representative case (Case 8) was shown in Figures 2 and 3. Bone union of the fracture site was obtained in all patients, and the mean period of bone union (duration of immobilization) was 6.3 weeks (range, 5.0–8 weeks) from the injury. The mean residual displacement on the anteroposterior and lateral view was 2.6 mm (range, 0.0–5.1 mm) and 2.2 mm (range, 0.0–5.0 mm), respectively. No patients developed remarkable deterioration of the fracture displacement necessitating a salvage operation. The mean ASA and anterior angulation of the ASDH at the first visit were 88.1° (range, 80–101°) and 45.1° (range, 24–63°), respectively. The mean ASA and anterior angulation of the ASDH at the bone union were 87.9° (range, 77–108°) and 46.4° (range, 21–71°), respectively. The mean variation of the ASA and anterior angulation of the ASDH was −0.1° (range, −11° to 16°) and −1.3° (range, −20° to 6°), respectively. Varus deformity of the distal humerus (ASA of <85°) was observed in 5 patients, and flexion deformity of the distal humerus (anterior angulation of the ASDH of <45°) was observed in 6 patients. Only 1 patient (Case 1) complained of the varus deformity of the distal humerus.

Table 3.

Follow-up periods, periods of bone union, and radiographic evaluations.

Figure 2.

Plain radiographs of a patient, 85-year-old female (Case 8), who had fallen down and injured her right arm. (A) Anteroposterior and (B) lateral radiographs of the right elbow at the initial visit to our hospital, showing the transcondylar fracture of the humerus. Initial displacement of the fracture was 1.9 mm on anteroposterior view and 3.2 mm on lateral view. Initial ASA and ASDH were 90 and 57 degrees, respectively.

Figure 3.

Plain radiographs at the final follow-up (Case 8). (A) Anteroposterior and (B) lateral radiographs of the right elbow, showing the established bone union. At the bone union, ASA and ASDH were 86 and 53 degrees, respectively.

3.2. Clinical results

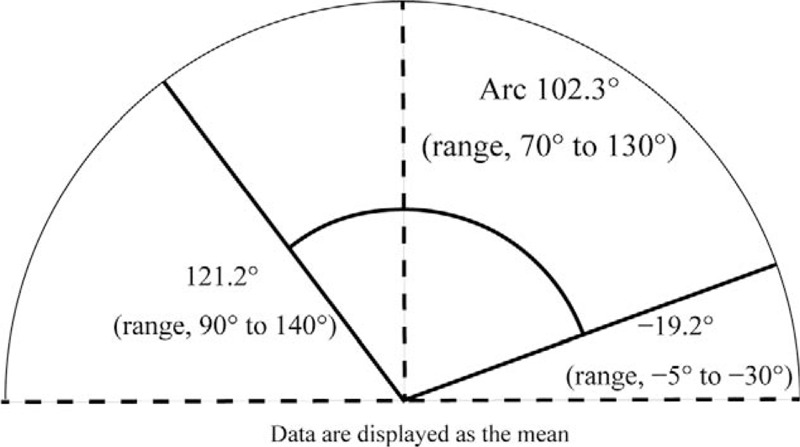

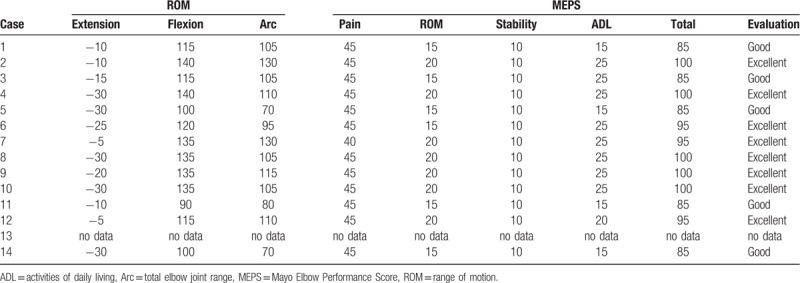

The ROM of the injured elbow joint was obtained in 13 patients. One patient (Case 11) showed remarkable flexion restriction. This patient's fracture was initially overlooked, and extension displacement of the fracture occurred. The extension deformity resulted in restriction of elbow flexion. At the bone union, the mean extension and flexion of the injured elbow was −19.2° (range, −5° to −30°) and 121.2° (range, 90–140°), respectively. The mean Arc of the injured elbow joint was 102.3° (range, 70–130°) (Fig. 4). Restriction of flexion (<120° flexion) was observed in 6 of the 13 elbows in which the ROM of the elbow joint was obtained. Although the restriction of elbow flexion resulted in disabilities of ADL, ADL were not severely deteriorated. No patients complained of residual pain of the elbow joint. The mean MEPS was 93.1 points (range, 85–100) (excellent in 8 elbows, good in 5 elbows) (Table 4).

Figure 4.

The range of motion and Arc of the injured elbow joint in 13 patients at the final follow-up. The mean extension and flexion of the injured elbow was −19.2° (range, −5° to −30°) and 121.2° (range, 90–140°), respectively. The mean Arc of the injured elbow joint was 102.3° (range, 70–130°).

Table 4.

Clinical evaluations, ROM, and MEPS.

4. Discussion

There is no objection to the fact that displaced transcondylar fractures of the humerus should be treated surgically.[1,7,16] During the last two decades, many reports have described satisfactory outcomes of transcondylar fractures of the humerus, and plate osteosynthesis with a locking plate system has become an accepted standard method in the treatment of these fractures in adults.[1,7,16] However, significant numbers of intraoperative and postoperative complications of plate osteosynthesis have also been reported.[1,7,16] Until recently, few clinical reports regarding nonsurgical treatment for these fractures have been published.[1–3,11,17] Nonsurgical treatment is not recommended for these fractures because immobilization with a long-arm splint or cast would be required for several months to achieve bone union. Moreover, nonsurgical treatment for transcondylar fractures of the humerus is associated with a high rate of complications and low possibility of bone union.[1–3,17] However, nonsurgical treatment with a cast or splint has several advantages. The patients do not require anesthesia and are treated as outpatients. Moreover, there is no risk of infection or neurovascular deficits.[11] However, little mention has been made of the radiographic and clinical outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical treatment for transcondylar fractures of the humerus.

Our results show that nonsurgical treatment for these fractures can be an alternative option for patients who do not desire surgery or have life-threatening complications. In our study, no significant complications of nonsurgical treatment were observed. With respect to radiological outcomes, all patients obtained bone union with a long-arm splint or cast, although immobilization for 6 or 8 weeks was required. In addition, although deterioration of the fracture displacement was observed on radiographs in most cases, no patients required a salvage operation. Moreover, although varus deformity of the distal humerus (ASA of <85°) was observed in 5 patients and flexion deformity of the distal humerus (anterior angulation of the ASDH of <45°) was observed in 6 patients, only 1 patient (Case 1) complained of the deformity.

With regard to clinical outcomes, no patients had residual elbow pain. However, restriction of elbow flexion to <120° was observed in 6 of 13 elbows. Basic research involving joint contracture models has shown that in cases of joint contracture due to immobilization, irreversible histological changes occur in the joints as the joint fixation period is prolonged.[18–21] However, the severity of joint contracture depends on several factors, such as the species of animal, the method of joint immobilization/temporary fixation, the fracture site, and the duration of immobilization.[19–23] In the present study, 14 elbows that underwent nonsurgical treatment were immobilized for 6 to 8 weeks, and an average ROM restriction of 35° to 40° occurred. Thus, elbow joint contracture is inevitable when transcondylar fractures of the humerus are treated nonsurgically. The restriction of flexion resulted in some disabilities of ADL, including combing hair and feeding oneself, in 6 patients of our study. The cause of this restriction was the hypertrophic callus on the fracture line, which inhibited elbow flexion. On the other hand, restriction of elbow extension had little negative impact on ADL. Thus, restriction of elbow extension, which results from flexion deformity of the distal humerus, would be tolerable to some extent. Conversely, restriction of elbow flexion, which results from extension deformity of the distal humerus, would not be tolerable.

In our study, no severely displaced fractures characterized by lack of contact with the fracture site were treated nonsurgically. Thus, the clinical outcomes of nonsurgical treatment for severely displaced transcondylar fractures of the humerus remain unknown. However, most patients in our study restored a pain-free and satisfactory level of elbow function and did not desire to pursue a salvage operation. Although the degree of displacement or complexity of the fracture may significantly influence the outcome, nonsurgical treatment is an effective option for most fractures with <6 mm of displacement on radiographs.

Our study has several limitations that are primarily associated with the inherent weaknesses of retrospective studies. The major limitations of this study are the small sample size and the lack of data regarding the outcomes of patients with severely displaced fractures characterized by no contact with the fracture site. In addition, the indication for surgical or nonsurgical treatment was at the surgeon's discretion. Thus, a further prospective randomized study is required to elucidate the clinical outcomes of nonsurgical treatment for transcondylar fractures of the humerus.

5. Conclusion

We have herein described the clinical outcomes of 14 elbows that underwent nonsurgical treatment for transcondylar fractures of the humerus. Our study showed that nonsurgical treatment is an effective option for most fractures with <6 mm of displacement on radiographs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Angela Morben, DVM, ELS, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac), for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yuji Tomori.

Data curation: Yuji Tomori.

Investigation: Yuji Tomori.

Methodology: Yuji Tomori.

Project administration: Yuji Tomori.

Supervision: Mitsuhiko Nanno, Shinro Takai.

Writing – original draft: Yuji Tomori.

Writing – review and editing: Mitsuhiko Nanno.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ADL = activities of daily life, Arc = total elbow joint range, ASA = articular surface angle, ASDH = anterior angulation of the articular surface of the distal humerus, MEPS = Mayo Elbow Performance Score, ROM = range of motion.

How to cite this article: Tomori Y, Nanno M, Takai S. Outcomes of nonsurgical treatment for transcondylar humeral fractures in adults. Medicine. 2019;98:46(e17973).

The authors have no funding to disclose.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1975 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards after obtaining approval from our institutional review board (Nos. 30-12-1048, 450-30-21).

Informed consent for the treatment and publication was obtained from all patients in this study.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Nauth A, McKee MD, Ristevski B, et al. Distal humeral fractures in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93:686–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Robinson CM, Hill RM, Jacobs N, et al. Adult distal humeral metaphyseal fractures: epidemiology and results of treatment. J Orthop Trauma 2003;17:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Perry CR, Gibson CT, Kowalski MF. Transcondylar fractures of the distal humerus. J Orthop Trauma 1989;3:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].John H, Rosso R, Neff U, et al. Operative treatment of distal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994;76:793–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Obert L, Ferrier M, Jacquot A, et al. Distal humerus fractures in patients over 65: complications. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2013;99:909–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Clavert P, Ducrot G, Sirveaux F, et al. Outcomes of distal humerus fractures in patients above 65 years of age treated by plate fixation. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2013;99:771–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang Y, Zhuo Q, Tang P, et al. Surgical interventions for treating distal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;CD009890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shimamura Y, Nishida K, Imatani J, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of the fixation methods for transcondylar fracture of the humerus: ONI plate versus conventional plates and screws. Acta Med Okayama 2010;64:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Korner J, Lill H, Müller LP, et al. The LCP-concept in the operative treatment of distal humerus fractures – biological, biomechanical and surgical aspects. Injury 2003;34Suppl 2:B20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zagorski JB, Jennings JJ, Burkhalter WE, et al. Comminuted intraarticular fractures of the distal humeral condyles. Surgical vs. nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Brown RF, Morgan RG. Intercondylar T-shaped fractures of the humerus. Results in ten cases treated by early mobilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1971;53:425–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Knuf KM, Maani CV, Cummings AK. Clinical agreement in the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification. Perioper Med (Lond) 2018;7:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE. The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA 1961;178:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Goldfarb CA, Patterson JM, Sutter M, et al. Elbow radiographic anatomy: measurement techniques and normative data. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012;21:1236–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Broberg MA, Morrey BF. Results of treatment of fracture-dislocations of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987;109–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Strauss EJ, Alaia M, Egol KA. Management of distal humeral fractures in the elderly. Injury 2007;38Suppl 3:S10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Srinivasan K, Agarwal M, Matthews SJ, et al. Fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly: is internal fixation the treatment of choice? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;222–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Trudel G, Uhthoff HK. Contractures secondary to immobility: is the restriction articular or muscular? An experimental longitudinal study in the rat knee. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Trudel G, Zhou J, Uhthoff HK, et al. Four weeks of mobility after 8 weeks of immobility fails to restore normal motion: a preliminary study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:1239–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ando A, Suda H, Hagiwara Y, et al. Remobilization does not restore immobilization-induced adhesion of capsule and restricted joint motion in rat knee joints. Tohoku J Exp Med 2012;227:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Trudel G, Uhthoff HK, Goudreau L, et al. Quantitative analysis of the reversibility of knee flexion contractures with time: an experimental study using the rat model. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wong K, Trudel G, Laneuville O. Noninflammatory joint contractures arising from immobility: animal models to future treatments. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:848290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Akeson WH, Woo SL, Amiel D, et al. Rapid recovery from contracture in rabbit hindlimb. A correlative biomechanical and biochemical study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977;359–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]