Dear Editor,

The type I-F CRISPR–Cas system from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA14) provides sequence-specific elimination of invading DNA1,2. Recently, a paper published in Cell Research reported that this system targets mRNA through a non-canonical mechanism3. Here, we implement the proposed design rules for generating CRISPR-RNA (crRNA)-guides that target RNA and test whether the proposed RNA-targeting activity provides immunity against RNA phage infection. Our experiments reveal that the type I-F CRISPR system provides protection from DNA, but not RNA phages.

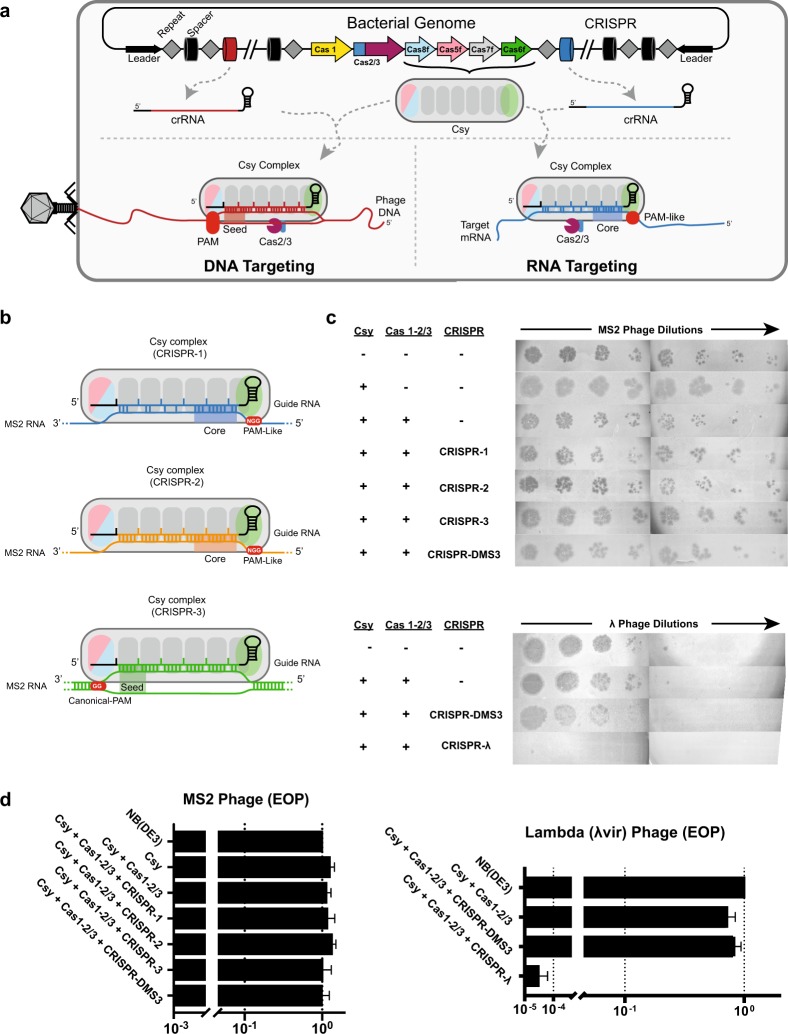

The proposed mechanism of RNA targeting is distinct from dsDNA targeting. Rather than detection of a dsDNA PAM via protein-mediated recognition of specific nucleobases4,5, Li et al.3 suggest that single-stranded RNA recognition proceeds via recognition of a “PAM-like” motif (5′-GGN-3′) on the opposite side of the complex and that this is followed by detection of a 12-nt “core” sequence (Fig. 1a). To assess the versatility of these RNA-targeting rules, we designed I-F CRISPRs to target the RNA genome of MS2 phage6.

Fig. 1. Testing the efficiency of type I-F CRISPR defense against RNA and DNA phages.

a The type I-F CRISPR–Cas system of P. aeruginosa (PA14) contains six cas genes flanked by two CRISPR loci. DNA binding by the crRNA-guided surveillance complex (Csy complex) relies on recognition of a double-stranded PAM followed by a complementary protospacer. Base pairing occurs in discrete increments of five. Every sixth nucleobase is covered by a beta-hairpin on Cas7 and these bases do not contribute to target interactions4,5. Target binding drives a conformational change in the Csy complex that recruits the Cas2/3 nuclease for target cleavage. In contrast to dsDNA binding, the proposed RNA-binding model requires the recognition of a single-stranded “PAM-like” sequence followed by a 12-nt core sequence. b Schematics of CRISPRs 1, 2, and 3. CRISPR-1 (top) represents the model proposed by Li et al.3 CRISPR-2 (middle) targets the same sequences as CRISPR-1, but the crRNA-guide is completely complementarity. CRISPR-3 (bottom) was designed using well-established rules for dsDNA-binding mechanism. c Tenfold of dilutions of MS2 phage (top) or lambda (λ) phage (bottom) on a lawn of wild-type E. coli NB(DE3) cells or NB(DE3) expressing the type I-F CRISPR system. d The efficiency of plaquing (EOP) of MS2 phage (left) and lambda phage (right). EOP was calculated as the ratio of plaque-forming units (PFUs) on I-F CRISPR expressing cells divided by the number of PFUs on control cells

We designed three synthetic CRISPR arrays that each contains spacers designed to target six different regions in the MS2 RNA phage genome (Supplementary Fig. S1). Spacers in the first CRISPR (CRISPR-1) were designed to target sequences with a “PAM-like” NGG motif, a “core” sequence, and mismatches along the target sequence identical to those identified by Li et al.3 (Fig. 1b). Spacers in the second CRISPR (CRISPR-2), were designed to target the same RNA sequences, but the crRNA-guide is 100% complementary to the RNA target (i.e., no mismatches). Spacers in the third CRISPR (CRISPR-3) were designed according to established dsDNA targeting rules. Secondary structures in the MS2 genome are likely to be important for RNA targeting, so the six spacers included in each CRISPR were designed to target locations with varying degrees of predicted secondary structure. These structures are similar to secondary structures predicted for the LasR mRNA, which is purported to be targeted for degradation by the type I-F CRISPR system in PA143.

To measure the efficiency of phage defense, we performed a series of plaque assays (Fig. 1c). None of the CRISPRs designed to target MS2 provided protection. To confirm that our experimental system is functional, we replaced the MS2 targeting CRISPR, with a CRISPR designed to target lambda (λ) phage (CRISPR-λ). Cells that express Csy, Cas2/3, and a synthetic CRISPR designed to target λ-phage, resulted in a 5-log reduction of plaques, as compared to non-targeting controls (i.e., CRISPR-DMS3) (Fig. 1c, d).

Importantly, the work presented here was not designed to replicate the previously published work by Li et al., but rather our intention was to determine if the non-canonical crRNA-guided recognition rules described by these authors could be generally applied for programable defense against RNA phages. Unlike the type III CRISPR systems described by Silas et al.7, the type I-F systems do not contain a reverse transcriptase, which would be necessary to incorporate new spacers from RNA-based parasites. Here, we by-pass new spacer acquisition, by creating synthetic CRISPRs designed to target the MS2 genome. Regardless of the design rule (canonical or non-conical), none of the MS2 targeting CRISPRs were capable of knocking down RNA phage infection. This biological result is supported by recent structural, biochemical, and biological assays which all show that Cas2/3 nuclease recruitment requires a conformational change in the Csy complex that is dependent on displacement of a non-complementary strand during crRNA-guided base pairing to the target DNA4. We acknowledge that CRISPR mechanisms are remarkably diverse and we remain open to alternative mechanisms for target recognition and Cas2/3 recruitment, however, Høyland-Kroghsbo et al.8 recently repeated the work by Li et al. but did not find evidence for RNA targeting in PA14. Collectively, these results suggest that type I-F CRISPR systems are capable of crRNA-guided detection and destruction of dsDNA, but not RNA.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Wiedenheft laboratory for comments, suggestions, and critical feedback. Research in the Wiedenheft laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health (P20GM103500, P30GM110732-03, R01GM110270, and R01GM108888), National Science Foundation (EPSCoR EPS-110134), the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust, and the Montana Agricultural Experimental Station.

Author contributions

M.B. and B.W. designed research and wrote the manuscript. M.B. performed the experiments of type I-F RNA-guided DNA-targeting and RNA-targeting plaque assays. B.W. supervised experiments. All authors contributed to data analysis and editing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

B.W. is the founder of SurGene, LLC, and is an inventor on patent applications related to CRISPR–Cas systems and applications thereof. The remaining author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper at (10.1038/s41421-019-0123-9).

References

- 1.Rollins MF, et al. Cas1 and the Csy complex are opposing regulators of Cas2/3 nuclease activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E5113–E5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620722114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong B, et al. Molecular insights into DNA interference by CRISPR-associated nuclease-helicase Cas3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:16359–16364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410806111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li R, et al. Type I CRISPR-Cas targets endogenous genes and regulates virulence to evade mammalian host immunity. Cell Res. 2016;26:1273–1287. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rollins MF, et al. Structure reveals a mechanism of CRISPR-RNA-guided nuclease recruitment and anti-CRISPR viral mimicry. Mol. Cell. 2019;74:132–142.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo TW, et al. Cryo-EM structures reveal mechanism and inhibition of DNA targeting by a CRISPR-Cas surveillance complex. Cell. 2017;171:414–426.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai X, et al. In situ structures of the genome and genome-delivery apparatus in a single-stranded RNA virus. Nature. 2017;541:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature20589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silas S, et al. Direct CRISPR spacer acquisition from RNA by a natural reverse transcriptase-Cas1 fusion protein. Science. 2016;351:aad4234. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Høyland-Kroghsbo NM, Muñoz KA, Bassler BL. Temperature, by controlling growth rate, regulates CRISPR-Cas activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio. 2018;9:e02184-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02184-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.