Abstract

Gentrification is a process in which formerly declining, under-resourced, neighborhoods experience reinvestment and in-migration of increasingly affluent new residents, with understudied implications for individual health and health-protective community resources for low-income and minority residents. Increased attention on urban health inequities have propelled research on the relationship between gentrification and health. Yet, there are significant challenges inherent in the study of gentrification given its non-linear process occurring at multiple levels and via various mechanisms in a complex web of urban systems. How then have empirical studies addressed questions regarding the relationship between gentrification and health and wellness from a conceptual and methodological standpoint? Applying key search terms to PubMed and Web of Science, we identified 546 papers published in the United States. This review is guided by three foundational premises informing the inclusion and exclusion of articles. These include: 1. a clear definition of gentrification and explicit health outcome; 2. identification of a specific geographic context (United States) in which gentrification occurs, and 3. use of a social determinants of health framework to identify potential health outcomes of interest. 17 papers met our inclusion criteria. Through systematic content analysis using MaxQDA software, we evaluated the included studies using three critical frames: 1. conceptualization of gentrification; 2. mechanisms linking gentrification and health; and 3. spatio-temporal considerations. Based on this analysis, we identify the strengths and limitations of existing research, and offer three methodological approaches to strengthen the current literature on gentrification and health. We recommend that future studies: 1. explicitly identify the mechanisms and levels at which processes can occur and systems are organized; 2. incorporate space and time into the analytical strategy and 3. articulate an epistemological standpoint driven by their conceptualization of the exposure and identification of the relevant mechanism and outcome of interest.

1. Introduction

Similar to the human body, the urban environment is an intricate web of social, political, physical and economic systems and diverse resources (Galea et al., 2005). The complexity of the urban environment is magnified during periods of urban change, such as during the process of gentrification. Gentrification is an interactive process in formerly declining, under-resourced, predominantly minority neighborhoods involving economic investment and increasing sources of capital infusion and in-migration of new residents, generally with a higher socio-economic status. The process is dynamic, uneven, and occurs in stages. (Clay, 1989; Helms, 2003; Hochstenbach and van Gent, 2015; Hwang and Sampson, 2014; Kerstein, 1990; Maloutas, 2012). The process of gentrification is a multi-level phenomenon linking social, political, and economic structures and conflict between blocks, neighborhoods, districts, cities and regions (Smith, 1996, p. 16). Simultaneously, it shapes a neighborhood’s social context, physical attributes, and other key resources and opportunities, which are critical to resident health outcomes (Hwang and Sampson, 2014b; Timberlake and Johns-Wolfe, 2017).

Efforts to reduce health inequities have propelled research on the relationship between gentrification and health. Yet, there are significant challenges inherent in the study of gentrification. Conceptually clear and methodologically rigorous research regarding the relationship between gentrification and health is challenging given the complex, multi-level, nuanced process of gentrification itself, as well as its potentially contradictory outcomes for different population groups. In addition, the specification of research questions concerning how and why urban change may affect health is of prime importance and requires consideration of systems spurring gentrification, from macrosocial forces such as limited federal government financial support to create new, affordable housing to local community factors such as the reliance of private developers to invest in housing and support business improvement districts (Galea and Schulz, 2006, p.278). Finally, given the spatially uneven process of gentrification and the ebbs and flows of gentrification through time, selection of relevant geographic scope of time periods of study are also essential considerations.

Confronting these challenges through explicit conceptualization and measurement of the phenomena itself and identification of potential mechanisms and relevant spatio-temporal scales can help illuminate how, for whom, and under what circumstances gentrification exacerbates or mitigates health inequities.

The aim of this review is to systematically evaluate how empirical studies have addressed questions regarding the relationship between gentrification and health and wellness conceptually and methodologically. Illuminating conceptual and methodological challenges can generate novel research approaches and methods for understanding and measuring the drivers of social exposures resulting in health inequities more generally. Specific to gentrification, it can facilitate unearthing plausible mechanisms linking gentrification and health and wellness, assisting in the production of a translational epidemiology linking research to policy and action.

Given the breadth of the literature on gentrification, this interdisciplinary review draws on research across the fields of public health, anthropology, sociology, environmental science, and criminology. We evaluate the included studies using three critical frames: 1. conceptualization of gentrification; 2. mechanisms linking gentrification and health; and 3. spatio-temporal considerations. Based on this analysis, we identify the strengths and limitations of existing research through these critical frames, and three methodological approaches to strengthen the current literature on gentrification and health. We recommend that future studies: 1. explicitly identify the mechanism(s) and levels (a construct that organizes systems and processes that can occur simultaneously but some of which may be more causally relevant than others) by which exposures are related to which outcomes, 2. incorporate space and time into the analytical strategy and 3. articulate an epistemological standpoint to improve methodological rigor driven by their conceptualization of the exposure and identification of the relevant mechanism and outcome of interest.

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Selected articles were empirical studies using either quantitative or qualitative data examining the relationship between gentrification and health. This review is guided by three foundational premises informing the inclusion and exclusion of articles. These include: 1. a clear definition of gentrification; 2. identification of a specific context (United States) in which gentrification occurs, and 3. use of a social determinants of health framework to identify potential health outcomes of interest. Each of these premises is described below.

First, we defined gentrification as a socio-economic process within neighborhoods where formerly declining disinvested neighborhoods experience reinvestment and in-migration of increasingly affluent new residents. In line with Maloutas’ call for conceptual clarity and theoretical rigor by exposing contextual assumptions within gentrification research, we specify the process of gentrification as operating in the United States geographic context (2012). This includes neighborhoods with a history of disinvestment and marginalization, neo-liberal regulation, commodification of housing, and restructuring of urban space which moves capital back to the city (Maloutas, 2012; Smith, 1979).

Second, given the varied trajectories and increasing globalization of gentrification, some argue that gentrification is now so generalized that the “concept captures no less than the fundamental state and market-driven ‘class-remake’ of cities throughout the world” (Shaw, 2008). Often gentrification, urban renewal and urban change are used interchangeably. For example, these terms are used to describe the process of gentrification or a completely distinct process, such as urban regeneration in the United Kingdom, which is led by government policies and not market forces, or in Paris where the urban core has never experienced disinvestment (Maloutas, 2012). For this systematic review, we incorporated a broad array of terms that may be associated with gentrification, and thoroughly reviewed the article to assess if words such as urban renewal were used in the context of gentrification in the United States.

Third, guided by a social determinants of health framework and by fundamental cause theory, we defined health and wellness broadly. The social determinants of health place importance on structural drivers and social, political, economic, and cultural conditions shaping a range of exposures and thus an array of health outcomes (Woolf and Braveman, 2011). Furthermore, the ability to control disease and death is mediated and moderated by access to fundamental flexible resources, including knowledge, money, power, prestige, and beneficial social connections, which may be shaped by gentrification (Link and Phelan, 1995). We therefore do not limit our search to direct health outcomes alone, but include a range of mediators and moderators to health status such as financial status and neighborhood crime, which research has shown to be a critical factor shaping mental and physical wellness (Giurgescu et al., 2015; Morrison Gutman et al., 2005; Nuru-Jeter et al., 2009, 2008; Theall et al., 2017). Financial hardship making housing unaffordable has been associated with anxiety, depression, and lower self-rated health (Burgard et al., 2012).

2.2. Search strategy

We conducted a literature search in April 2018 according to the 2009 PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). We used Web of Science and PubMed databases to identify empirical studies in the United States with no restrictions on publication date. Keywords related to the exposure included gentrification, gentrified, urban renewal, urban change, and socio-economic ascent. Keywords related to the outcome used in Web of Science given its interdisciplinary scope included health, disease, medical, medicine, and wellness. These key words were not used when searching the PubMed database, given PubMed’s exclusive focus on biomedical, science and health literature.

2.3. Identification and study selection

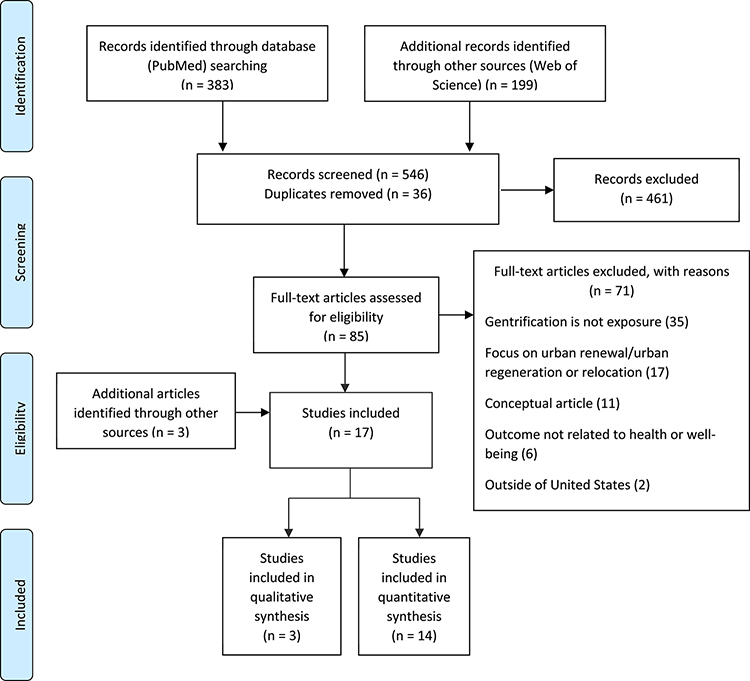

The search located 383 entries through PubMed and 199 through Web of Science, with 36 duplicate entries (Figure 1). A review of 546 titles and abstracts using the aforementioned eligibility criteria resulted in the exclusion of 461 articles. We examined the remaining 85 full-text articles based on our exclusion/inclusion criteria, and excluded an additional 71 articles. These 71 articles were excluded for the following reasons: 1. gentrification was not the primary exposure of interest or there was exclusive focus on assessing if displacement is induced by gentrification (35); 2. urban renewal/urban regeneration/relocation was the exclusive focus of the article and did not connect gentrification with health and wellness (17); 3. the article was theoretical in nature (11), and 4. outcomes were not related to health and wellness (6). A list of the 85 articles reviewed and the rationale for exclusion is provided in Appendix 1. Three additional articles were identified through other sources and reference lists. This resulted in the inclusion of 17 articles.

Figure 1:

Flow chart following guidelines in the PRISMA statement (Moher et al., 2010)

2.4. Data extraction and analytic approach

Using MaxQDA Pro 2018 software, for each study, we extracted the following information: author(s), title, year, conceptualization of gentrification, hypothesized mechanisms and levels of these mechanisms, spatial scale, frequency of measurement, measurement approach, frequency of gentrification measurement to capture change over time, spatial scale of data measuring gentrification, and health outcomes. To examine our main research question - how have empirical studies examined the relationship between gentrification and health and wellness from a conceptual and methodological standpoint – we conducted the following process. First, we identified categories of the ways gentrification was conceptualized through content analysis. These categories were defined in the codebook with examples to ensure consistent coding. Then, mechanisms were coded and grouped and included in the established codebook with examples. The level at which these mechanisms operated were also coded and analyzed concurrently with the mechanism itself using the Reports function in MaxQDA. Furthermore, we assessed the spatial and temporal characteristics of gentrification and outcome measures.

3. Results

Reflecting recent salience of gentrification processes in urban health research, all studies were published since 2011. Ten of the 17 articles were published after 2015. Of the 17 articles meeting our inclusion criteria, three used qualitative data in their analysis. Two qualitative studies used a case study approach to explore the experience of gentrification and exclusion of Latinos from health protective neighborhood resources and social fabric (Anguelovski, 2015; Betancur, 2011). The third qualitative study used semi-structured interviews to examine experiences of gentrification and structural drivers of food insecurity (Whittle et al., 2015).

The remaining 14 studies employed quantitative data. All of the quantitative studies used longitudinal data to measure exposure to the process of gentrification. Discordantly, 11 of these studies measured a health outcome at only one point in time (Abel and White, 2011; Anguelovski, 2015; Breyer and Voss-Andreae, 2013; Desmond and Gershenson, 2017; Ding et al., 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016a; Gibbons and Barton, 2016; Huynh and Maroko, 2014; Kreager et al., 2011; Linton et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018). Three remaining articles from all 14 studies employing quantitative data (two articles which focused on the outcomes of crime and violence) used longitudinal data for both the exposure and outcomes of interest (Lim et al., 2017; Papachristos et al., 2011; Smith, 2014).

The reviewed studies encompassed a broad range of outcomes related to health and wellness. These included: socio-spatial patterns of exclusion, mobility and industrial air toxic risk exposure (Abel and White, 2011; Anguelovski, 2015; Ding et al., 2016) access to healthy food and food insecurity (Breyer and Voss-Andreae, 2013; Whittle et al., 2015), housing instability (Desmond and Gershenson, 2017), financial health (Ding et al., 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016a), self-rated health (Gibbons and Barton, 2016; Smith et al., 2018), crime (Kreager et al., 2011), health care access (Lim et al., 2017), homelessness (Linton et al., 2014), preterm birth (Huynh and Maroko, 2014); robberies and homicide rates (Papachristos et al., 2011); gang homicides (Smith, 2014), and violent crime (Gibbons and Barton, 2016).

Fourteen studies acknowledged the potential impact of gentrification on marginalized and underserved populations (Abel and White, 2011; Anguelovski, 2015; Breyer and Voss-Andreae, 2013; Desmond and Gershenson, 2017; Ding et al., 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016b; Gibbons and Barton, 2016; Huynh and Maroko, 2014; Kreager et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2017; Linton et al., 2017; Smith, 2014) for example, with one study focusing on people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) (Whittle et al., 2015) and one focused on the elderly (Smith et al., 2018)

In the following section, we evaluate the included studies using three critical lenses: 1. conceptualization of gentrification; 2. mechanisms linking gentrification and health; and 3. spatio-temporal considerations. We provide examples of both strengths and limitations of current research through these lenses. Identifying how current studies are conceptualizing gentrification, the extent in which there is explicit articulation of mechanisms linking gentrification and health and wellness, and consideration of spatio-temporal scales will provide the foundation for a subsequent discussion illuminating opportunities to increase rigor in current research on gentrification and health and wellness.

3.1. Conceptualization of gentrification

A conceptual framework transforms experiential knowledge, prior theory, and research into a system of constructs and presumed interrelationships among them that supports or informs one’s research (Maxwell, 2012, p. 39; Miles and Huberman, 1994, p. 18). Additionally, conceptual frameworks help identify the most critical variables to include in research design and the ways in which they influence one another (Ravitch and Riggan, 2012, p. 6).

We identified three key ways in which authors themselves articulated their conceptualization of gentrification in guiding their research. These categories do not reflect the expansive literature on the multitude of ways gentrification is conceptualized and are not mutually exclusive; categories of how gentrification is conceptualized in these research articles are the following: 1. socio-economic upgrading; 2. political conflict and urban restructuring, and 3: stages of gentrification. Identifying how research conceptualizes gentrification shapes the research questions posed, the facets of the complex construct of gentrification that are interrogated, the variables employed or groups given voice, and relevant methods utilized, as illustrated in the following examples. The majority of studies (14/17) described gentrification as a process of socio-economic upgrading. For example, Huhyn et al., state: “little work has examined the influence of social and economic change over time (i.e., gentrification) on health” (2014). Three of these studies considered the racial dimensions of gentrification by explicitly examining, either quantitatively or qualitatively, differences in the relationship between gentrification and health among individuals or communities identifying as distinct racial and ethnic identities (Anguelovski, 2015; Barton, 2016; Papachristos et al., 2011). Three articles also included residential displacement as potentially part of the process of gentrification (Desmond and Gershenson, 2017; Ding and Hwang, 2016b; Gibbons and Barton, 2016) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Categories of conceptualization and associated mechanisms

| Author(s) and Year | Study Aim(s) | Mechanism and Level | Category of Conceptualization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abel and White, 2011 | Examine Seattle’s sources of air toxic exposure and related uneven pollution risk and its relationship to inequitable development in gentrified areas. | Neighborhood attributes (infrastructure) | Socio-economic upgrading |

| Anguelovski, 2015 | Socio-spatial patterns and exclusion are produced through decreasing access to resources and supermarket greenling, which are generally unwanted by local residents. This study aims to understand how these places establish new forms of exclusion and privilege. | Sense of community/exclusion | Urban restructuring and political conflict |

| Barton, 2016 | Assess if changes in violent crime rates were associated with gentrification. | Neighborhood attributes (economic) | Socio-economic upgrading |

| Betancur, 2011 | Explore if the experience of gentrification of Latinos is one of invasion, succession, or forceful relocation. | Sense of community/exclusi on | Urban restructuring and political conflict |

| Breyer and Voss-Andrae, 2013 | Assess if food mirages (numerous food outlets but with high priced foods, preventing healthy food consumption among low-income residents) converge with gentrified areas. | Individual health protective resources | Socio-economic upgrading |

| Desmond and Gershenson, 2017 | Examine 3 mechanisms (1. discrimination; 2. life shock, and 3. concentrated disadvantage and gentrification, which is the focus of this matrix, and social isolation) that may be associated with disparities in eviction among low-income families. | Neighborhood attributes (economic) | Socio-economic upgrading/Displace ment |

| Ding and Hwang, 2016 | Examine the relationship between financial status changes and gentrification, in relation to mobility of residents and stage of gentrification. | Individual resources; Neighborhood attributes (economic) | Socio-economic upgrading/Displace ment/and Stages of gentrification |

| Ding et al., 2016 | Examine mobility patterns based on stage of gentrification, which neighborhoods residents move to, if it differs for the most vulnerable, and time at which gentrification commenced in the neighborhood. | Neighborhood attributes (economic) | Socio-economic upgrading/Displace ment/and Stages of gentrification |

| Gibbons and Barton, 2016 | Determine the relationship between gentrification and self-rated health. Assess if the relationship differs depending if gentrification results in an influx of white or black residents. | Neighborhood attributes (economic) Sense of community/exclusion | Socio-economic upgrading/Displace ment |

| Huynh and Marako, 2014 | Assess the association between gentrification and preterm birth (PTB). | Neighborhood attributes (economic); Individual health protective resources | Socio-economic upgrading |

| Kreager, 2011 | Examine the relationship between crime and gentrification in the city of Seattle in the 1980s and 1990s. | Neighborhood attributes (economic and social cohesion) | Stages of gentrification |

| Lim et al., 2017 | Compare rates of health care access and mental health status between those who remained in gentrifying neighborhoods and those who were displaced (individuals who moved from gentrifying to non-gentrifying areas). | Neighborhood attributes (economic); Individual health protective resources | Socio-economic upgrading |

| Linton et al., 2017 | Examine the association between local-level housing and economic conditions with homelessness among persons who inject drugs (PWID). | Neighborhood attributes (economic) | Socio-economic upgrading |

| Papachristos, 2011 | Examine the relationship between gentrification and neighborhood crime rates (homicides and street robbery) in Chicago from 1995 – 2005. | Neighborhood attributes (economic) Sense of community/exclusion | Socio-economic upgrading |

| Smith, 2014 | Examine the effects of three forms of gentrification—demographic shifts, private investment, and state intervention—on gang-motivated homicides in Chicago from 1994 to 2005. | Neighborhood attributes (economic) Sense of communit/exclusion | Socio-economic upgrading/Urban restructuring and political conflict/Stages of Gentrification |

| Smith et al., 2018 | Examine the relationship between gentrification and older adults’ self-rated health and mental health, with a particular focus on those that are economically vulnerable. | Individual resources; Neighborhood attributes (economic) | Socio-economic upgrading |

| Whittle et al., 2015 | Explore the experiences and structural drivers of urban policies shaping gentrification among food insecure people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in San Francisco. | Political and economic institutions | Socio-economic upgrading |

The second conceptualization of gentrification is based on theories of power, race and political conflict. One study (Smith, 2014) conceptualized gentrification and incorporated socio-economic upgrading and political conflict within a staged process. Two articles explicitly conceptualized gentrification as a process interwoven with urban restructuring and political conflict (Anguelovski, 2015; Betancur, 2011). For example, Anguelovski indicates gentrification includes changes in the socio-economic and demographic composition of a neighborhood, while also employing language concerning gentrification’s inherent power and racial dynamics.

Anguelovski writes:

when supermarket greenlining occurs, it produces new socio-spatial patterns and experiences of environmental inequality and exclusion, transforming these amenities into new locally unwanted land uses (LULUs) for vulnerable residents. LULUs comprise not only toxic sites and industries, as highlighted by much of the traditional EJ literature, but can also include green amenities. Protests against current urban redevelopment dynamics highlight the multiple forms of exclusion and displacement produced by food gentrification, and by the manipulation of health and sustainability discourses about food.” (2011).

Here, gentrification is an unjust process where the right to land, ownership and power over key decisions is appropriated by new, predominately white residents with higher incomes.

Two studies conceptualized gentrification as a staged process along with it triggering socio-economic upgrading and displacement (Ding et al., 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016b). Incorporating a staged model implies outcomes may differ for individuals depending on the extent in which gentrification has advanced in the neighborhood (Ding et al., 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016b). Hypothesized stages of gentrification differ across studies. For example, two studies classified gentrified tracts that started gentrifying in 2000 as either experiencing weak, moderate or intense gentrification (Ding et al., 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016b). Kreager also identified gentrification as a staged process, with crime rates being moderated during the most advanced stages of gentrification (2011). In the next section we identify the mechanisms explicitly articulated in the reviewed studies. These conceptualizations have implications for spatio-temporal scales employed for measuring exposures and outcomes, along with the types of data collected. These implications are presented in the discussion section below.

3.2. Mechanisms linking gentrification and health

The context of gentrification influences the operation of mechanisms; these mechanisms indicate how and why macrosocial factors, such as gentrification, impact population health (Ng and Muntaner, 2014). Mechanisms operate at various levels (i.e. individual, interpersonal, community, institutional) simultaneously; the extent in which each level is causally relevant to the outcome of interest is determined by the conceptualization of the phenomenon of interest (Krieger, 2008).

We identified four categories of mechanisms, operating at distinct levels across studies, linking gentrification to health. First, the majority of studies identified neighborhood attributes and specified the following neighborhood-level sub-categories: either in terms of altered infrastructure, economic opportunities/development, or social cohesion as the main attribute linking gentrification and health and wellness (Abel and White, 2011; Barton, 2016; Desmond and Gershenson, 2017; Ding et al., 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016b; Gibbons and Barton, 2016; Huynh and Maroko, 2014; Kreager et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2017; Linton et al., 2015; Papachristos et al., 2011; Smith, 2014; Smith et al., 2018). Second, four studies identified individual mechanisms of change via individual health protective resources within a neighborhood experiencing gentrification (Breyer and Voss-Andreae, 2013; Ding and Hwang, 2016b; Huynh and Maroko, 2014; Lim et al., 2017). Third, three of these studies identified both neighborhood and individual level mechanisms such as economic opportunities and growth and individual health protective resources such as financial status (Ding and Hwang, 2016b; Huynh and Maroko, 2014; Lim et al., 2017). Fourth, one study focused on the role of political and economic institutions in shaping the relationship between gentrification and health (Whittle et al., 2015).

Linking findings concerning the conceptualization of research with mechanisms employed, the mechanisms of neighborhood attributes or individual level resources were associated with conceptualizing gentrification as a process of socio-economic upgrading (Abel and White, 2011; Barton, 2016; Breyer and Voss-Andreae, 2013; Desmond and Gershenson, 2017; Ding et al., 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016b; Gibbons and Barton, 2016; Huynh and Maroko, 2014; Kreager et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2017; Linton et al., 2015; Papachristos et al., 2011; Smith, 2014; Smith et al., 2018). Three studies related to sense of community/exclusion conceptualized gentrification as a process combining urban restructuring and political conflict (Anguelovski, 2015; Betancur, 2009; Smith, 2014).

3.3. Spatiotemporal considerations for rigorous research

A third challenge in the literature on gentrification and health outcomes is the ability to adequately capture the spatial and temporal dimensions of processes of neighborhood change. Gentrification is driven by varying dynamics across community, city, regional and national scales with urban neighborhood impacts, but it can also start on a single city block; it can be rapid, or the process can take decades to unfold (Beauregard, 1990; Brown-Saracino, 2017; Hwang and Sampson, 2014; Shaw, 2008; Smith, 2002). As Hwang and Sampson point out, traditional data sources do not capture multi-level political and economic forces, such as the nature of global capital flows, nor do census tracts allow us to assess gentrification’s uneven nature within neighborhoods (2014). However, the scale and time periods at which gentrification is measured matters. As such, we assessed the scale and time period each article used to understand how and to what extent are the various spatial and temporal attributes relevant to gentrification reflected in current research (Table 2).

Table 2:

Temporal and spatial considerations and concordance with health outcomes

| Author(s) and Year | Health Outcomes | Scale/Unit of Analysis | Data on Timing of Exposure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abel and White, 2011 | Air toxic exposure risk measured from 1990 – 2007 | Census Block Groups | Two timepoints: 1990 – 2000 |

| Anguelovski, 2015 | Socio-spatial patterns of exclusion from 2011 to 2014 | Neighborhood | Over time |

| Barton, 2016 | Crime | 55 sub-boroughs (40 census tracts with approximately 100,000 residents each) | Three timepoints: 1980, 1990, 2000 |

| Betancur, 2011 | Neighborhood based support and advancement over a period of 10 years | Neighborhood | Over time |

| Breyer and Voss-Andrae, 2013 | Decreasing access to healthy food; food prices were collected in 2011 | 140 census tracts in Portland | Change between 2000 and 2010 |

| Desmond and Gershenson, 2017 | Nature of inequality, housing instability among low-income renters; eviction data was drawn from 2009 – 2011 | Census Tracts | Two timepoints: 2000 and 2010 |

| Ding and Hwang, 2016 | Changes in financial health of residents; credit scores from 2002 – 2014 | Census Tracts | Change between 2000 and 2010 |

| Ding et al., 2016 | Residential mobility patterns from 2002 – 2014 | Census Tracts | 1980, 1990, and 2000 and ACS estimates for 2009–2013 |

| Gibbons and Barton, 2016 | Self-rated health measured in 2008 | Census Tracts | Two timepoints: 2000 and ACS estimates 2005 – 2009 |

| Huynh and Marako, 2014 | Preterm birth from 2008 – 2010 | 59 community districts (ranging in population between 35,000 and 200,000) | Two timepoints: 1990 and ACS estimates 20052009 |

| Kreager, 2011 | Crime, as measured by difference in crime indexes in 1990 (averaged across 1989–1991) and measured in 2000 (averaged across the three years spanning 1999–2001) crime indexes | Census Tracts | Two timepoints: 1990 and 2000 |

| Lim et al., 2017 | Emergency department visits and hospitalizations of recurring patients from 2006 – 2014 | Neighborhoods were defined using Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) boundaries (n = 55, median population in each PUMA = 149,447 according to 2014 ACS) | 5 years post displacement for each individual |

| Linton et al., 2017 | Homelessness within one year of 2009 | Zip Code | Two timepoints; 1990 and 2009 |

| Papachristos, 2011 | Crime (homicide and robbery) | 341 neighborhood clusters, which contain Chicago’s 847 census tracts | Five time periods (3 year average between 1991 and 2000) |

| Smith, 2014 | Crime (gang-motivated homicide) | Metropolitan Neighborhoods | Two timepoints; 2000 and 2010 |

| Smith et al., 2017 | Self-rated health and mental health among elderly and economically vulnerable population in 2011 | Census Tracts | Two timepoints; 2000 and 2010 |

| Whittle et al., 2015 | Food insecurity; qualitative data collected in 2014 | 34 semistructured interviews | One point in time in 2014 |

We focus first on spatial scale. Ten quantitative studies used census tracts as the unit of analysis (Abel and White, 2011; Breyer and Voss-Andreae, 2013; Desmond and Gershenson, 2017; Ding et al., 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016b; Gibbons and Barton, 2016; Kreager et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2018). One analyzed data at the zip code level (Linton, 2017), one used Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) boundaries (n = 55, median population in each PUMA = 149,447) (Huynh and Maroko, 2014), and three analyzed data at the neighborhood cluster or sub-borough level (Barton, 2016; Papachristos et al., 2011; Smith, 2014). Two qualitative studies used study participant and author perceptions of place to identify gentrifying neighborhoods (Anguelovski, 2015; Betancur, 2011).

Beyond the spatial, gentrification possesses temporal attributes requiring consideration when assessing the effect gentrification may have on health. It is a staged process that can occur over time, in quick succession, or with varying levels of intensity. As such, we analyze the literature through these three different lenses. First, gentrification itself is a process and to reflect its temporal nature changes over time should be clearly articulated and reflected in both the conceptualization and measurement of variables. As shown in Table 2, all quantitative studies examined in this review except for three articles focusing on crime (as a result of the widespread availability of crime data over time), lacked measurement of change of both the exposure and outcome of interest (Macintyre et al., 2002). For example, Gibbons and Barton used self-rated health to assess how gentrification – a process inherently reproducing change – only at one point in time (2008).

Second, gentrification is a staged process which can occur in quick succession. To capture its health effects, it is necessary to design studies selecting outcomes where the exposure time of gentrification can theoretically trigger a change in health outcomes, employing multiple data points to capture any shifts in health outcomes, and allowing for adequate lag-time between the stage of gentrification and measurement of outcomes of interest. Particular outcomes can plausibly change within the finite period of time during the stages of gentrification; examples of these outcomes in the reviewed literature include crime, financial health, self-rated health, emergency department visits, and homelessness (Barton, 2016; Ding and Hwang, 2016b; Gibbons and Barton, 2016; Kreager et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2017; Linton et al., 2015; Papachristos et al., 2011; Smith, 2014; Smith et al., 2018). Diseases with a long pre-clinical phase or health outcomes resulting from stressful, severe life events causing weathering could be overlooked if the hypothesized exposure period is inadequate to theoretically induce the specific health outcome, if data collection is infrequent, or if lag-time between the exposure and outcome is absent thereby not permitting enough time for the disease to progress. As an example, a health outcome of interest that theoretically requires exposure over the life course is preterm birth (Luet al., 2010). This outcome, employed by Huynh and Marako’s 2013 article was collected at one point in time between 2008 – 2010, which overlaps with the time period included in estimating gentrification as the community district level (population between 35,000 and 200,000). The large scale for measuring gentrification, selection of a health outcome that requires an extended exposure period, measurement of the outcome at one point in time, and overlapping time periods between health outcome and exposure increase the risk of misestimating the relationship between gentrification and health.

The inconsistent pace of gentrification over time, and the differential impacts pace may have on health outcomes requires longitudinal data for both the exposure and outcome. Regarding hypotheses of the varying intensity of gentrification over time, two studies explicitly mentioned the pace of gentrification (Ding et al., 2016; Kreager et al., 2011). As an example, Kreager hypothesizes that gentrification in 1980’s Seattle was “spotty” and contributed to increases in crime yet with a more complete gentrification in the 1990s, gentrification was associated with decreases in crime (2011).

4. Discussion

Our results indicate a surge of gentrification and health research since 2015 within the United States context. A broad number of health and wellness outcomes are employed in studies, ranging from crime rates to pre-term birth, with health outcomes generally measured at one point in time. The majority of studies conceptualized gentrification as a socio-economic process, primarily occurring at the individual level. Only three studies identified neighborhood and individual level mechanisms as integral factors in identifying the connection between gentrification and health and wellness. This is despite evidence that both individual, neighborhood level change (i.e. people and place policies) are intertwined and reinforce one another (Galster, 2017; Katz, 2004). Further, gentrification itself is a political and economic process spanning communities, regions, and institution, requiring examination of mechanisms across scales and levels.

Furthermore, while gentrification results from forces at various scales, the process can occur on a block by block or neighborhood basis. In the reviewed studies, the smallest unit of analysis was the census tract, with four studies using data of a larger spatial scale. Regarding temporality, only three studies studied the process of urban change by incorporating data for more than one point in time for both the exposure and outcome.

Narrowing the context to the United States allows for specification of the urban context, reflecting the history of formerly declining, under-resourced urban areas inhabited by marginalized populations. Through this lens we can assess the literature on gentrification and health while beginning to understand how health equity is reflected in current research. Implications of the findings and suggested avenues to advance the field are discussed below.

4.1. Conceptualization of gentrification and linkages to mechanisms

Integral to understanding the relationship between gentrification and health is developing conceptual clarity around gentrification itself and explicit articulation of the guiding principles for its conceptualization within each research study. With competing definitions, it is imperative to specify the aspect of gentrification guiding conceptualization of research. The majority of studies identified the broad term of socio-economic upgrading as the defining feature of gentrification. Only one study focused on the role of political and economic institutions, providing evidence of the rejection of critical perspectives of gentrification as evidenced by a pre-occupation with ideological differences in the literature and dominance of neoliberalism (Slater, 2006). Absent or muddled in the literature are the power dynamics inherent in gentrification, the differential valuing of individuals based on class and race, in addition to the upstream structural factors that drive gentrification and engender class and racial conflict. This prevents identification of who is responsible if negative health impacts are associated with gentrification, and the potential points of intervention (Krieger, 2001).

Social epidemiology’s increasing focus on causality and policy-related research to guide action on how to improve population health (translational social epidemiology) requires clarity and rigor around the logical propositions linking conceptualization of a modifiable exposure to mechanisms that link exposures to outcomes (Oakes et al., 2015). Clear conceptualization of the exposure and mechanisms linking the exposure to the outcome of interest are critical from both policy development and causal inference perspectives. For example, conceptualizing gentrification as a socio-economic process, as identified in the reviewed literature, is related to various mechanisms of neighborhood and individual level attributes. It spans levels and is connected with political, economic, and social institutions and community resources. As such, articulation of the mechanisms, associated levels, and measurement of these variables is necessary to understand the mechanisms that can be intervened upon to modify the relationship between the exposure of gentrification for instance and the outcome of interest. In terms of causality, violation of the consistency assumption threatens causality but is avoided when whichever facet of socio-economic upgrading is altered, the outcome is the same (Rehkopf et al., 2016). The “treatment” of gentrification encompasses various forms of socio-economic upgrading (such as business developments, employment opportunities, social networks, etc.) and the lack of specificity stemming from the conceptualization of the treatment can threaten causal inference (Rehkopf et al., 2016) and validity more generally.

Regarding explicit identification of the mechanisms linking exposures to outcomes to support a translational epidemiology, analyses indicate a lack of rigor in connecting the conceptualization of gentrification to the hypothesized mechanisms that influence health. First, we highlight three studies providing strong examples of concordance between the conceptualization of gentrification and the mechanisms and levels identified in research on gentrification and health. Breyer and Voss-Andrae (2013) conceptualize gentrification as a process that changes neighborhood food resources. They thus measure outcomes as the cost and availability of healthy food at the neighborhood level. This study provides a clear conceptualization between the process (gentrification), the mechanism (changing the types of grocery stores in a neighborhood), and its impacts on low-income populations (increased cost of food which may go against the goal of expanding access to healthy food). Kreager stipulates gentrification as a process changing both population and property characteristics such as high-end residential development and improving an area’s real estate and local infrastructure (2011). According to Kreager, gentrification is a form of urban restructuring that occurs when infrastructure development and real estate enhancement change area-level characteristics, which in turn results in area-level shifts in crime. This is different from a study that conceptualizes gentrification as a process that displaces low-income households. This too may lead to a reduction in crime, but in this case, area level investment in infrastructure would not be the appropriate mechanism.

Ding et al., examines how stage of gentrification, which alters affordability, moderates mobility patterns (2016). Among vulnerable residents living in neighborhoods of moderate or intense levels of gentrification are more likely to move to lower-income neighborhoods, shedding light on the importance of the outcome of residential moves (Ding, et al., 2016). Critical to the strength of this study’s research design is their clear conceptualization of gentrification as socio-economic upgrading within central urban areas in previously low-income neighborhoods whereby incoming residents are of a higher socio-economic status (2016). The authors also clearly state that while this conceptualization implies displacement, evidence is inconclusive. Given this, mechanisms linking gentrification and mobility (rather than displacement via eviction for instance) relate to affordability of the neighborhood. Affordability, an economic mechanism at the neighborhood level then directly is reflected in their research aim to “examine mobility patterns based on stage of gentrification, which neighborhoods residents move to, if it differs for the most vulnerable, and time at which gentrification commenced in the neighborhood” (Ding et al., 2016).

To illustrate ramifications of discordance and/or lack of clarity between conceptualization and mechanisms, we use one case example. To be sure, data constraints are a critical barrier, but it is instructive to identify theory to help reveal ideal research designs and considerations to drive methodological decisions. Huynh and Marako test the association between gentrification and pre-term birth (2013). In this study, gentrification is conceptualized as socio-economic upgrading, resulting in higher income residents and housing investment. This may cause changes in neighborhood economic attributes by providing additional opportunities or material resources, while also potentially resulting in increased stress and susceptibility to disease due to the displacement of health protective social networks and key community institutions, for example. This broad conceptualization of gentrification and potential mechanisms however does not specify the chronic or acute exposure to gentrification that can plausibly be linked to pre-term birth. Given this broad conceptualization of gentrification and lack of specificity and measurement regarding the hypothesized mechanisms that result in pre-term birth, the opportunity to develop policy recommendations to reduce health inequity as a result of this work is lost. In this case, a theoretical framework to identify what we know and assume would anchor firm hypotheses. For example, employing life course theory would lead to questions regarding length of time and intensity of exposure to gentrification, changes in material resources prior to and within the period of exposure, and distinctions between levels of exposure, timing and embodiment. This would then require a shift in mechanisms, measurements, and considerations of spatiotemporal scale.

4.2. Linking conceptualization, mechanisms and epistemology

The conceptualization of an exposure can reflect the worldview or epistemology of the researcher. Epistemology is not solely a way of knowing but systems of knowing and this knowledge is generated through the subjective experiences of individuals (Creswell, 2014, p. 20). Worldviews, tied to these systems, are influenced by the conditions in which people live and learn, and these can be formed by their gender, race, class, sexuality, language and other forms of difference (Ladson-Billings, 2000).

The scarcity of research focused on political conflict, despite substantial literature on gentrification acknowledging conflicts and tensions around race, class, and displacement provides an opportunity for developing research that is suited to uncovering these experiences and social meanings via interpretive methods. Analyses of two papers (Betancur, 2009; Anguelovski, 2015) employing political conflict as their conceptual frame and sense of community/exclusion as the mechanism of interest illustrates the manner in which conceptualization and identification of mechanism highlights epistemological standpoints. Explicit identification of these three facets of research can lead to identification of research methods best suited to answer the area of inquiry.

First, Betancur’s aim was to identify if gentrification was an invasion, succession, or forceful relocation for a group of long-term Latino residents. He captures shifts in resident experiences, elucidating how intensifying gentrification resulted in transitioning from efforts around community building to a community defense. In addition, Anguelovski, explicitly identifies the powerful elite and articulates their goal of shifting ownership of the community, from lower-income residents to outside sources of capital. This is illustrated by clear identification of investors developing properties for higher-income residents and municipal leaders labeling areas of reinvestment as “sites for revitalization and tourism” (Anguelovski, 2015). The author does not employ the conceptualization of gentrification as a form of socio-economic upgrading, unlike the majority of the other studies reviewed. Rather, conceptualization of gentrification as a political conflict incites a social justice framework and moves away from a positivist epistemology. Because of this framing, he focuses on “new socio-spatial patterns and experiences of exclusion, transforming amenities into locally unwanted land uses (LULUS)” (Anguelovski, 2015). Therefore, experiences of community and exclusion are the factors tying gentrification to health. By extension, the level of interest is the community-level, which aligns with the study aim to understand how gentrifying places establish new forms of exclusion and privilege.

Betancur and Anguelovski’s worldview focusing on conflict, experience, and justice lend itself to interpretive methods. It places priority on generating detailed rich description and using systematic procedures to uncover new knowledge that is situated within the context of the knower who is producing this knowledge (Yanow and Schwartz-Shea, 2015, p. 10). Interpretive methods emphasize a deeper understanding of how does one know and that distancing in fact compromises a deeper understanding acknowledgement of the “messiness that is part of being human” (Yanow and Schwartz-Shea, 2015, p. 430). These two papers use a case study design, centered on qualitative data collection that allows for redefining main research questions during data collection, unearthing and contextualizing experiences and meanings, and giving voice to individuals (Keene, 2018, pp. 194–195). Furthermore, moving away from generalizability acknowledges the heterogeneity of neighborhoods and supports employing case studies of extreme cases (Small et al., 2018). In addition, it allows for hypothesizing and examining distinct effects of gentrification across subpopulations (Small and Feldman, 2012).

4.3. Considerations of spatio-temporal scale

Analyses of these research studies through the lens of spatio-temporal scale reveal limited consideration of the implications of large scales, spatial dependencies, and research design implications resulting from the unevenness of gentrification itself. These considerations can be helpful in guiding clear, rigorous research. First, studies of gentrification employing large areal units such as PUMA boundaries, will likely face the modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) where artificial units of spatial reporting of continuous geographical phenomena results in artificial spatial patterns; this issue is akin to ecological fallacy (Heywood et al., 1998, p. 8). Aggregated values will vary depending on which boundaries we use. For example, analysis of data aggregated at the county level will offer distinct conclusions in comparison to data collected at the census tract level. At smaller spatial scales, ranges or variations in data are more apparent. A larger spatial scale may obscure important extremes. Gentrification is often conceptualized as an uneven urban phenomenon. As such, larger areal units, such as PUMA boundaries and potentially census tracts, which range in population size between 1,800 and 8,000 individuals, with the optimal size being 4,000 individuals, may not capture the unevenness of gentrification. In early stage gentrifying areas, gentrification may not occur within a tract as a whole but on a block by block basis. Understanding both the stage of gentrification and the density of the urban environment in which it is taking place will be helpful in identifying the most appropriate scale. Though the lens of density for example, the measurement scale of gentrification in Los Angeles may be distinct in comparison to the dense, older structural environment of New York City. Similarly, smaller scale measurement at the onset of gentrification may be able to signal incoming shifts of gentrification processes in comparison to larger whole-neighborhood changes.

Moreover, all census tracts do not have the same probability of being gentrified. Those census tracts that are least likely to gentrify due to continued lack of investment and marginalization may be clustered. Being surrounded by multiple disinvested tracts may have distinct implications for residents than living close to clustered resource rich census tracts (Diez Roux and Mair, 2010). This lack of independence, or spatial dependency between census tracts, may induce spillover effects beyond the imposed census tract boundaries and affect health outcomes (Diez Roux and Mair, 2010). None of the studies but one study by Ding et al., discussed spatial dependencies as a limitation in research or acknowledged the varying spatial contexts relevant to the gentrification process. Ding et al., both acknowledged and incorporated statistical analysis reflecting spatial dependencies by restricting their sample to residents of nongentrifying or gentrifying areas that are .5 miles away from gentrifying neighborhoods, assuming the amenities in gentrifying areas may confound the relationship between the exposure and outcome variables of interest.

Third, gentrification is a dynamic process that occurs in stages (Clay, 1979, p. 57; Helms, 2003; Hwang and Sampson, 2014). Health outcome data was collected and analyzed at only one point in time for the 12 quantitative studies that focused on non-crime related outcomes. This may increase selection bias, which occurs when the subjects identified are not representative of the target population. For example, collecting data at only one point in time during the advanced stages of gentrification may capture low-income residents who were not displaced, for example, because they owned their home or had strong family support networks; these households may not be representative of the population, therefore distorting any measure of association. Furthermore, collecting outcome data at one point in time prohibits accounting for past effects of the process of gentrification on health and identification of an appropriate latency period. Given gentrification’s dynamic, staged process, one should consider the following: 1. the number of not only exposure data points to quantify urban change but importantly outcome data points used in the study and 2. hypotheses regarding whether gentrification is constant or accelerates at certain points in time and the resultant timepoints necessary to capture those changes.

5. Limitations and Conclusions

This is the first systematic review, to our knowledge, which provides an account of the conceptualization of current research related to gentrification and health, mechanisms identified across studies, and offers opportunities to strengthen current research as a result of this analysis. This review is limited by the search terms selected and the review protocol implemented. We conceptualized health and wellness broadly, aiming to include as many articles as possible. Although we used a combination of search strategies to find published articles that met our eligibility criteria, it is possible that our search strategy missed some articles that would have been eligible.

Research on gentrification can pave the way to developing a process for understanding the influence of complex macrosocial phenomena on health. Debates may ensue regarding whether gentrification is a powerful determinant of urban poverty. Regardless, conceptual clarity, clear linkages to mechanisms, and intentional research design that responds to the methodological challenges of understanding gentrification and city and regional transformation are necessary to begin the process of illuminating social exposures magnifying health inequities. Furthermore, understanding linkages between gentrification and other processes of neighborhood change contributing to health inequity will encourage methodical and careful thinking and research about gentrification itself and economic shifts within cities (Brown-Saracino, 2016). It is by wrestling with this complexity that we will move from medical advancements for individuals to understanding how to advance population level health equity.

Highlights.

An array of health outcomes was examined, ranging from crime rates to pre-term birth

Health outcomes were generally only measured at one point in time

The majority of studies conceptualized gentrification as socio-economic upgrading, overlooking power dynamics and structural factors

Few studies consider small scales for analysis, spatial dependencies, and unevenness of gentrification itself

We recommend studies explicitly identify the mechanism and associated levels linking gentrification and health, incorporate space and time and articulate an epistemological standpoint driven by their conceptualization of the exposure

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Dr. Danya Keene for helpful comments and suggestions. Dr. Tulier received support from the Yale University Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (#T32MH02003).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: None

References

- Abel TD, White J, 2011. Skewed riskscapes and gentrified inequities: environmental exposure disparities in Seattle, Washington. Am. J. Public Health 101 Suppl, S246–54. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski I, 2015. Healthy Food Stores, Greenlining and Food Gentrification: Contesting New Forms of Privilege, Displacement and Locally Unwanted Land Uses in Racially Mixed Neighborhoods. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res 39, 1209–1230. 10.1111/1468-2427.12299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton M, 2016. An exploration of the importance of the strategy used to identify gentrification. Urban Stud 53, 92–111. 10.1177/0042098014561723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard RA, 1990. Trajectories of Neighborhood Change: The Case of Gentrification. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Sp 22, 855–874. 10.1068/a220855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur J, 2011. Gentrification and community fabric in Chicago. Urban Stud 48, 383–406. 10.1177/0042098009360680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breyer B, Voss-Andreae A, 2013. Food mirages: Geographic and economic barriers to healthful food access in Portland, Oregon. Health Place 24, 131–139. 10.1016/J.HEALTHPLACE.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Saracino J, 2017. Explicating Divided Approaches to Gentrification and Growing Income Inequality. Annu. Rev. Sociol 43, 515–539. 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Saracino J, 2016. An Agenda for the Next Decade of Gentrification Scholarship. City Community 15, 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, Seefeldt KS, Zelner S, 2012. Housing instability and health: Findings from the Michigan recession and recovery study. Soc. Sci. Med 75, 2215–2224. 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2012.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay PL, 1989. Choosing Urban Futures: The Transformation of American Cities. Stanford Law Pol. Rev 1. [Google Scholar]

- Clay PL, 1979. Neighborhood renewal: middle-class resettlement and incumbent upgrading in American neighborhoods Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, 2014. Research design : qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches SAGE Publications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M, Gershenson C, 2017. Who gets evicted? Assessing individual, neighborhood, and network factors. Soc. Sci. Res 62, 362–377. 10.1016/J.SSRESEARCH.2016.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Roux AV, Mair C, 2010. Neighborhoods and health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1186, 125–145. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Hwang J, 2016a. The Consequences of Gentrification: A Focus on Residents’ Financial Health in Philadelphia

- Ding L, Hwang J, 2016b. The Consequences of Gentrification: A Focus on Residents’ Financial Health in Philadelphia. CITYSCAPE 18, 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Hwang J, Divringi E, 2016. Gentrification and Residential Mobility in Philadelphia. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ 61, 38–51. 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Freudenberg N, Vlahov D, 2005. Cities and population health. Soc. Sci. Med 60, 1017–1033. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Schulz A, 2006. Methodological considerations in the study of urban health

- Galster G, 2017. People Versus Place, People and Place, or More? New Directions for Housing Policy. Hous. Policy Debate 27, 261–265. 10.1080/10511482.2016.1174432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons J, Barton MS, 2016. The Association of Minority Self-Rated Health with Black versus White Gentrification. J. Urban Health 93, 909–922. 10.1007/s11524-016-0087-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giurgescu C, Misra DP, Sealy-Jefferson S, Caldwell CH, Templin TN, Slaughter-Acey JC, Osypuk TL, 2015. The impact of neighborhood quality, perceived stress, and social support on depressive symptoms during pregnancy in African American women. Soc. Sci. Med 130, 172–180. 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms AC, 2003. Understanding gentrification: an empirical analysis of the determinants of urban housing renovation. J. Urban Econ 54, 474–498. 10.1016/S0094-1190(03)00081-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heywood I, Cornelius S, Carver S, 1998. An Introduction to Geographical Information Systems Addison Wesley Longman Ltd

- Hochstenbach C, van Gent WP, 2015. An anatomy of gentrification processes: variegating causes of neighbourhood change. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Sp 47, 1480–1501. 10.1177/0308518X15595771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh M, Maroko AR, 2014. Gentrification and preterm birth in New York City, 2008–2010. J. Urban Health 91, 211–220. 10.1007/s11524-013-9823-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J, Sampson RJ, 2014. Divergent Pathways of Gentrification. Am. Sociol. Rev 79, 726–751. 10.1177/0003122414535774 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, 2004. Neighbourhoods of choice and connection [Google Scholar]

- Keene DE, 2018. Qualitative Methods and Neighborhood Health Research. Neighborhoods Heal 193. [Google Scholar]

- Kerstein R, 1990. Stage models of gentrification: an examination. Urban Aff. Q 25, 620–639. 10.1177/004208169002500406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreager DA, Lyons CJ, Hays ZR, 2011. Urban Revitalization and Seattle Crime, 1982–2000. Soc. Probl 58, 615–639. 10.1525/sp.2011.58.4.615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, 2008. Proximal, distal, and the politics of causation: what’s level got to do with it? Am. J. Public Health 98, 221–30. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, 2001. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int. J. Epidemiol 30, 668–677. 10.1093/ije/30.4.668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings G, 2000. Racialized discourses and ethnic epistemologies. Handb. Qual. Res 2, 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Chan PY, Walters S, Culp G, Huynh M, Gould LH, 2017. Impact of residential displacement on healthcare access and mental health among original residents of gentrifying neighborhoods in New York City. PLoS One 12, e0190139 10.1371/journal.pone.0190139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J, 1995. Social Conditions As Fundamental Causes of Disease. J. Health Soc. Behav 35, 80 10.2307/2626958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton SL, Cooper HL, Kelley ME, Karnes CC, Ross Z, Wolfe ME, Friedman SR, Jarlais D. Des, Semaan S, Tempalski B, Sionean C, DiNenno E, Wejnert C, Paz-Bailey G, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Study Group, 2017. Cross-sectional association between ZIP code-level gentrification and homelessness among a large community-based sample of people who inject drugs in 19 US cities. BMJ Open 7, e013823 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton SL, Cooper HLF, Kelley ME, Karnes CC, Ross Z, Wolfe ME, Jarlais D. Des, Semaan S, Tempalski B, DiNenno E, Finlayson T, Sionean C, Wejnert C, Paz-Bailey G, Group, for the N.H.B.S.S., 2015. HIV Infection Among People Who Inject Drugs in the United States: Geographically Explained Variance Across Racial and Ethnic Groups. Am. J. Public Health 105, 2457–2465. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton SL, Jennings JM, Latkin CA, Kirk GD, Mehta SH, 2014. The association between neighborhood residential rehabilitation and injection drug use in Baltimore, Maryland, 2000–2011. Health Place 28, 142–149. 10.1016/J.HEALTHPLACE.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Hogan V, Jones L, Wright K, Halfon N, 2010. Closing the Black-White gap in birth outcomes: a life-course approach. Ethn. Dis 20, S2–62–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S, 2002. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them?, Social Science & Medicine [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloutas T, 2012. Contextual diversity in gentrification research. Crit. Sociol 38, 33–48. 10.1177/0896920510380950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA, 2012. Qualitative research design: An interactive approach Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook sage, Thousand Oaks (Cal.) [etc.]. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med 151, 264 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison Gutman L, McLoyd VC, Tokoyawa T, 2005. Financial Strain, Neighborhood Stress, Parenting Behaviors, and Adolescent Adjustment in Urban African American Families. J. Res. Adolesc 15, 425–449. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00106.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng E, Muntaner C, 2014. A Critical Approach to Macrosocial Determinants of Population Health: Engaging Scientific Realism and Incorporating Social Conflict. Curr. Epidemiol. Reports 1, 27–37. 10.1007/s40471-013-0002-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nuru-Jeter A, Dominguez TP, Hammond WP, Leu J, Skaff M, Egerter S, Jones CP, Braveman P, 2009. “It’s The Skin You’re In”: African-American Women Talk About Their Experiences of Racism. An Exploratory Study to Develop Measures of Racism for Birth Outcome Studies. Matern. Child Health J 13, 29–39. 10.1007/s10995-008-0357-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuru-Jeter A, Williams CT, LaVeist TA, 2008. A methodological note on modeling the effects of race: the case of psychological distress. Stress Heal 24, 337–350. 10.1002/smi.1215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes JM, Andrade KE, Biyoow IM, Cowan LT, 2015. Twenty Years of Neighborhood Effect Research: An Assessment. Curr. Epidemiol. Reports 2, 80–87. 10.1007/s40471-015-0035-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristos AV, Smith CM, Scherer ML, Fugiero MA, 2011. More Coffee, Less Crime? The Relationship between Gentrification and Neighborhood Crime Rates in Chicago, 1991 to 2005. City Community 10, 215–240. 10.1111/j.1540-6040.2011.01371.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravitch SM, Riggan M, 2012. Reason and rigor

- Rehkopf DH, Glymour MM, Osypuk TL, 2016. The Consistency Assumption for Causal Inference in Social Epidemiology: When a Rose Is Not a Rose. Curr. Epidemiol. Reports 3, 63–71. 10.1007/s40471-016-0069-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw K, 2008. Gentrification: What It Is, Why It Is, and What Can Be Done about It. Geogr. Compass 2, 1697–1728. 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00156.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slater T, 2006. The Eviction of Critical Perspectives from Gentrification Research. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res 30, 737–757. 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00689.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small ML, Feldman J, 2012. Ethnographic Evidence, Heterogeneity, and Neighbourhood Effects After Moving to Opportunity, Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht 10.1007/978-94-007-2309-2_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small ML, Manduca RA, Johnston WR, 2018. Ethnography, Neighborhood Effects, and the Rising Heterogeneity of Poor Neighborhoods across Cities. City Community 17, 565–589. 10.1111/cico.12316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CM, 2014. The Influence of Gentrification on Gang Homicides in Chicago Neighborhoods, 1994 to 2005. Crime Delinq 60, 569–591. 10.1177/0011128712446052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N, 2002. New Globalism, New Urbanism: Gentrification as Global Urban Strategy. Antipode 34, 427–450. 10.1111/1467-8330.00249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N, 1996. The New Urban Frontier Routledge; 10.4324/9780203975640 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N, 1979. Toward a Theory of Gentrification A Back to the City Movement by Capital, not People. J. Am. Plan. Assoc 45, 538–548. 10.1080/01944367908977002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, Lehning AJ, Kim K, 2018. Aging in Place in Gentrifying Neighborhoods: Implications for Physical and Mental Health. Gerontologist 58, 26–35. 10.1093/geront/gnx105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theall KP, Shirtcliff EA, Dismukes AR, Wallace M, Drury SS, 2017. Association Between Neighborhood Violence and Biological Stress in Children. JAMA Pediatr 171, 53 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake JM, Johns-Wolfe E, 2017. Neighborhood Ethnoracial Composition and Gentrification in Chicago and New York, 1980 to 2010. Urban Aff. Rev 53, 236–272. 10.1177/1078087416636483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle HJ, Palar K, Hufstedler LL, Seligman HK, Frongillo EA, Weiser SD, 2015. Food insecurity, chronic illness, and gentrification in the San Francisco Bay Area: An example of structural violence in United States public policy. Soc. Sci. Med 143, 154–161. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SH, Braveman P, 2011. Where Health Disparities Begin: The Role Of Social And Economic Determinants--And Why Current Policies May Make Matters Worse. Health Aff 30, 1852–1859. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanow D, Schwartz-Shea P, 2015. Interpretation and method: Empirical research methods and the interpretive turn Routledge. [Google Scholar]