Abstract

Individual control over learning leads to better memory outcomes, yet it is still unclear which aspects of control matter. One’s sense of agency may be a key component, but it can be challenging to dissociate it from its consequences on the environment. Here, we use a paradigm in which participants in one condition have the opportunity to choose between cues (choice condition) and in another are instructed which cue to select (fixed condition). Because the cues have no effect on the memoranda, we can isolate the effect of choice on memory. Participants also rated the cues for preference before and after encoding, allowing us to test how the number of times a cue was chosen affected its preference. By pooling multiple behavioral studies, we were able to use an individual differences approach to examine the relationship between choice effects on preference and memory. Replicating previous work, we found that immediate and delayed (24-hour) recognition memory was higher for items encountered in the choice condition. We also found that cues that were selected more often increased their preference in the choice condition, but actually decreased their preference in the fixed condition, suggesting that choice engaged value-related processes. Critically, we found a positive across-subjects relationship between choice memory enhancements and choice-induced preference change for delayed but not immediate memory. These data suggest that a shared value-based mechanism enhances preference for choice cues and memory consolidation of choice outcomes. Thus, the value of choice may play an important role in learning enhancements.

Introduction

Imbuing individuals with agency—providing individuals with the opportunity to actively engage with their experiences—enhances learning and memory. For example, when individuals make choices about what they are learning, they acquire information faster and show better episodic memory (Gureckis & Markant, 2012; Markant, DuBrow, Davachi, & Gureckis, 2014; Murty, DuBrow, & Davachi, 2015, 2018; Rotem-Turchinski, Ramaty, & Mendelsohn, 2018). Accordingly, there is growing interest in manipulating choice opportunities to enhance learning, particularly in academic contexts. However, in fully self-directed settings, it is unclear which of a number of processes may lead to various types of learning enhancements. Characterizing these processes at both behavioral and neurobiological levels will be necessary in order to tailor effective interventions.

Across a number of studies, multiple aspects of active learning, involving individuals directly in the learning process (e.g., through agency), have been proposed to drive choice-related learning enhancements (Kornell & Metcalfe, 2006; Kornell & Son, 2009; Markant et al., 2014; Voss, Gonsalves, Federmeier, Tranel, & Cohen, 2011; Voss, Warren, et al., 2011), including strategically deploying attention, adaptively controlling study time, and making restudy and self-testing decisions. Interestingly, subsequent studies have shown that giving individuals the opportunity to make choices, even inconsequential choices, is sufficient to enhance memory (Murty et al., 2015; Rotem-Turchinski et al., 2018). For example, we recently found that when given the opportunity to select an occluder screen to reveal a to-be-remembered object underneath, memory was greater for items that participants actively chose to reveal despite there being no relationship between their choice of occluder and which items were revealed. Thus, choice can enhance memory even when it has no effect on the content of the learning experience. While the majority of research in this domain has focused on which specific features of control are related to memory enhancements (Markant et al., 2014; Voss, Warren, et al., 2011), how inconsequential choices can enhance memory remains unclear.

One mechanism by which choice may improve memory is by enhancing value-related processes when individuals have a sense of agency over their environment. A large body of literature shows that episodic memory is enhanced for items associated with high value, e.g., in the form of monetary rewards (Miendlarzewska, Bavelier, & Schwartz, 2016; Murty & Adcock, 2017), intrinsic curiosity (Gruber, Ritchey, Wang, Doss, & Ranganath, 2016; Kang et al., 2009; Marvin & Shohamy, 2016), and even survival (Nairne, Pandeirada, & Thompson, 2008; Nairne, Thompson, & Pandeirada, 2007). Critically, choice may also be inherently valuable -- the choice-induced preference literature has shown that individuals prefer items that they actively chose over their unselected counterparts (Ariely & Norton, 2008; Leotti, Iyengar, & Ochsner, 2010), and will forgo monetary rewards in order to have more choices (Fujiwara et al., 2013). Research has also shown that individuals prefer neutral cues that indicate the opportunity to make their own choice compared to cues that indicate someone else would make a choice for them (Leotti & Delgado, 2011, 2014). These findings suggest that learning may also be preferable when given the opportunity to choose. This increased value for learning environments associated with choice may in turn drive memory enhancements.

In the current study, we characterized how the opportunity to choose influences memory and value-related processes, respectively, as well as the relationship between them. Participants performed a choice memory task in which to-be-encoded object images were hidden behind occluder screens. We manipulated whether individuals were able to actively select which occluder screen to remove (choice trials) or whether the occluder screen had been pre-selected (fixed trials). Both conditions required the same motor action, and in neither case did the selection actually affect which object image was revealed. To characterize the effect of perceived choice on memory, we tested recognition for the object images immediately and at a 24-hour delay. To characterize value-related processes, we administered a rating task to assess preference for the Hiragana characters appearing on occluder screens before and after encoding, computed preference change (post-encoding minus pre-encoding), and for each screen, related its preference change to the number of times it was selected during encoding (selection-induced preference measure). Finally, we compared how these measures differed across the choice and fixed conditions and tested whether individual differences in memory and preference change were related. Given that value-related effects on memory have been shown to be more pronounced after a 24-hour delay (Murayama & Kitagami, 2014; Murayama & Kuhbandner, 2011; Patil, Murty, Dunsmoor, Phelps, & Davachi, 2017), we hypothesized that the relationship between preference and memory would be stronger for the 24-hour versus immediate memory test.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the New York University and New York City communities across three separate cohorts from separate studies. Informed consent was obtained from each participant in a manner approved by the University Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects. Data for the current analyses were collapsed across the three studies, which used the same paradigm. Study 1 was purely behavioral, Study 2 was behavioral with eye tracking, and Study 3 used functional magnetic resonance imaging. In Studies 1 and 2, a total of 36 healthy, right-handed participants were paid $25 to participate. Three participants from Study 1 were excluded due to failure to follow task instructions (n=1), familiarity with the stimuli (n=1), and failure to complete the 24-hour recognition memory test (n=1), resulting in 17 participants in Study 1 and 16 participants in Study 2. In Study 3, 24 healthy, right-handed participants were paid $50 to participate. Three participants were excluded from the present analyses due to either failure to follow task instructions (n=1) or failure to complete the memory test (n=2). Thus, the final sample size is 54 (35 females; 18–35; median age = 23). Given the secondary nature of the present work (i.e., a re-analysis of previously collected data), we opted to include all available data. A post-hoc power analysis for our main result is reported below.

General Procedure

After informed consent was obtained, participants were given instructions for the task. They then performed, in order, the pre-encoding ratings task, the encoding task, and the post-encoding ratings task (Figure 1A). The delayed recognition test was conducted after approximately 24 hours. Participants in Studies 1 and 2 (n = 33) also completed a recognition test after the encoding phase on day 1. These 33 participants completed all tasks in a behavioral testing room. Participants in Study 3 (n = 21) completed the ratings and encoding tasks in the MRI scanner and then returned the following day to complete the delayed memory test in a behavioral testing room.

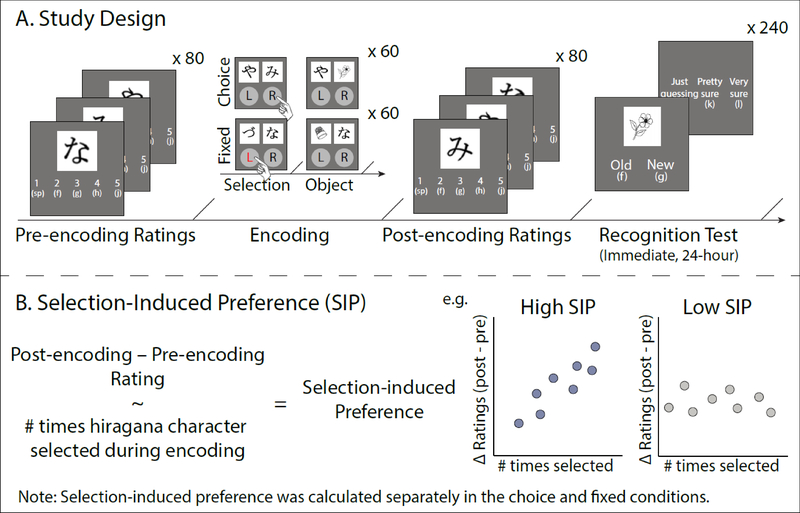

Figure 1.

(A) The study design includes 80 trials each of pre- and post-encoding ratings, 120 trials of the encoding task split across the choice and fixed conditions, and 240 trials of the recognition test. Participants in studies 1 and 2 completed half of the trials immediately and half after a 24-hour delay; participants in study 3 completed all trials after the 24-hour delay. (B) Calculation of selection-induced preference. High selection-induced preference results from greater ratings at post- than pre-encoding ratings the more times a character was selected.

Rating Task

The goal of the rating task was to measure changes in preference from before to after the encoding task for the hiragana characters that were used as occluder screens during encoding. Hiragana characters of the Japanese writing system were chosen for being abstract, eliciting some amount of aesthetic preference, and being unfamiliar and unnamable to most of our participants. The pre-encoding ratings were used to get baseline preference ratings for 80 hiragana characters. On each trial, a character was presented for 4 seconds during which participants indicated how much they liked the character on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = lowest rating, 5 = highest rating). Each trial was followed by a fixation dot for 2 – 5 seconds. We selected the 40 most neutrally-rated characters, creating 20 pairs matched for preference to use as occluder screens in the encoding task. Notably, pairs of occluder screens only appeared in either the choice or fixed condition. The post-encoding rating task followed the same procedure, and was used to quantify changes in preference for Hiragana characters as a function of the number of times they were selected during encoding (detailed below).

Encoding Task

The goal of the choice encoding task was to measure the effects of agency on episodic memory. Each trial started with the presentation of a cue for 1 second, followed by a fixation dot for 2–4 seconds. The cue indicated the current trial’s condition (i.e., choice or fixed). Next, the selection phase consisted of two occluder screens labeled with hiragana characters presented with a button below each that would be selected to reveal a to-be-remembered trial-unique object image underneath. On choice trials, participants selected either of the two screens, and on fixed trials, they were instructed to select a given screen indicated by red text on the button. In both cases, responses had to be made within 2 seconds to reveal an object image, which was presented for another 2 seconds. Participants were instructed to remember each object for a later memory test (note: participants were instructed that they only needed to remember object images, not hiragana characters). A fixation dot lasting 3–24 seconds (exponentially distributed, M = 6.3 seconds) followed each encoding trial. This range of ITIs was selected to optimize fMRI data analysis and was consistent across all studies despite only one using fMRI. Each participant completed 120 trials in total, 60 of each in the choice and fixed conditions. Choice and fixed trials were pseudo-randomly interleaved such that were no more than 3 subsequent presentations of the same condition.

Pairs of hiragana characters were repeated 6 times in the same condition across the experiment, and the left/right position of each character was counterbalanced across trials. Repetition of hiragana pairs allowed us to track preference changes that might arise from selection during the task. Unbeknownst to participants, their choice of hiragana characters had no effect on which objects were revealed. If no selection was made within 2 seconds or if the non-indicated screen was selected in the fixed condition, that trial was removed from analysis (mean/range of excluded trials: 2.4/0–15).

Recognition Task

In the recognition task, participants were shown object images that were either old (i.e., presented during encoding) or new (i.e., novel foil). They were asked to indicate whether they had previously seen each image (yes/no) and then rate their confidence (very sure, pretty sure, or just guessing). The test was self-paced with a 1 second ITI. Participants completed 240 trials in all, 60 objects from the choice condition, 60 from the fixed condition, and 120 novel foils. Participants in Studies 1 and 2 (n = 33) completed half of the trials immediately after the post-encoding rating task on day 1 and half when they returned on day 2. Participants in Study 3 completed all recognition trials during the day-2 memory test.

Analysis

For the rating task, we developed a behavioral marker to track how the number of times an occluder screen was selected in either the choice or fixed condition influences participants’ preference for the hiragana character appearing on that screen, i.e., selection-induced preference (Figure 1B). We calculated these scores separately for hiragana characters appearing in the choice and fixed conditions. For each participant, we calculated the difference in pre- versus post-encoding preference ratings for each hiragana character (Δ-preference). Then, we calculated how many times each character was selected during the encoding task (#- selected). Then, for all the hiragana characters within a given condition (choice, fixed), we calculated a simple regression between Δ-preference and #-selected. Positive beta values would reflect an increase in preference as a function of the number of times a hiragana character was selected.

To test for memory differences between the choice and fixed conditions, we performed paired t- tests with corrected recognition (hit rate – false alarm rate) in each condition as a within- subjects factor. This measure of corrected recognition was used to avoid altering the data, which would be necessary for calculating d-prime for individuals with no false alarms on the immediate memory test. Separate t-tests were run with memory performance at the 24-hour delay (with all 54 participants) and the immediate test (with the 33 participants in Studies 1 and 2). Note, the results of these memory analyses have been reported previously (Murty et al., 2015, 2018). For the novel preference change analyses, we again performed paired t-tests to investigate whether selection-induced preference differed between the choice and fixed conditions. We also performed post-hoc, one-sample t-tests to compare each condition against a baseline (beta = 0) that represents no influence of selection on preference change.

Given prior research demonstrating choice-related enhancements in both value and memory, we hypothesized that choice-induced preference and choice memory enhancements would be positively associated. To investigate the relationship between the influence of choice on long-term memory and its influence on selection-induced preference, we first calculated difference scores (choice minus fixed) for each individual and behavioral measure separately. Then, we ran an across-subjects correlation between memory difference scores and selection-induced preference difference scores. We also ran post-hoc tests to investigate relationships between memory benefits and selection-induced preference in each condition separately. The same procedures were then implemented for immediate recognition memory in the subgroup that performed the immediate test. Comparisons between correlations with immediate versus 24-hour memory were calculated using an R-to-Z transform.

Finally, since data from three studies were combined in these analyses, we wanted to ensure that the observed relationships were not driven by differences between studies. Therefore, we ran an across-subjects multiple regression on memory with study number as an additional predictor variable. We tested for both a main effect of study number and an interaction with selection-induced preference. Statistical thresholds for all analyses were considered to be significant when p < 0.05, and trending when p < 0.10.

Results

Memory Performance

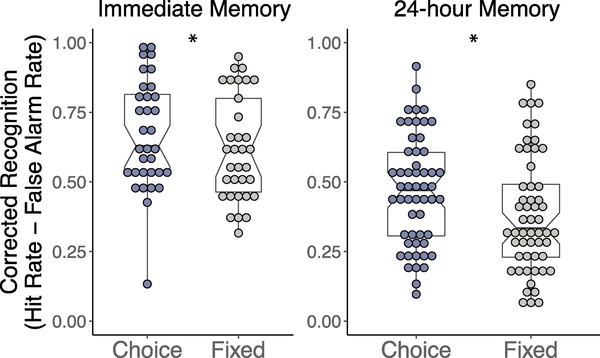

All memory scores reported are corrected recognition (i.e., hit rates minus false alarm rates=s). At the immediate memory test there was greater memory performance for items in the choice compared to the fixed condition (t(32) = 3.06, p < 0.01, d = 0.53). A similar pattern of results was also observed at the 24-hour memory test (t(53) = 5.44, p < 0.001, d = 0.74, Figure 2). A breakdown of all recognition memory data can be found in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Corrected recognition at the immediate (left) and 24-hour delay (right) memory tests in the choice and fixed conditions. * p < 0.05

Table 1.

Hit rates and false alarm rates in the choice and fixed conditions at the immediate and 24- hour tests across studies.

| Study 1 (n=17) | Study 2 (n= 16) | Study 3 (n= 21) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 Mean (SE) | Day 2 Mean (SE) | Day 1 Mean (SE) | Day 2 Mean (SE) | Day 1 Mean (SE) | Day 2 Mean (SE) | ||

| Hits | Choice | 0.83 (.20) | 0.75 (.10) | 0.76 (.19) | 0.67 (.17) | — | 0.72 (.09) |

| Fixed | 0.78 (.19) | 0.65 (.11) | 0.72 (.18) | 0.56 (.14) | — | 0.66 (.10) | |

| FA | 0.14 (.03) | 0.22 (.10) | 0.11 (.03) | 0.20 (.05) | — | 0.30 (.09) | |

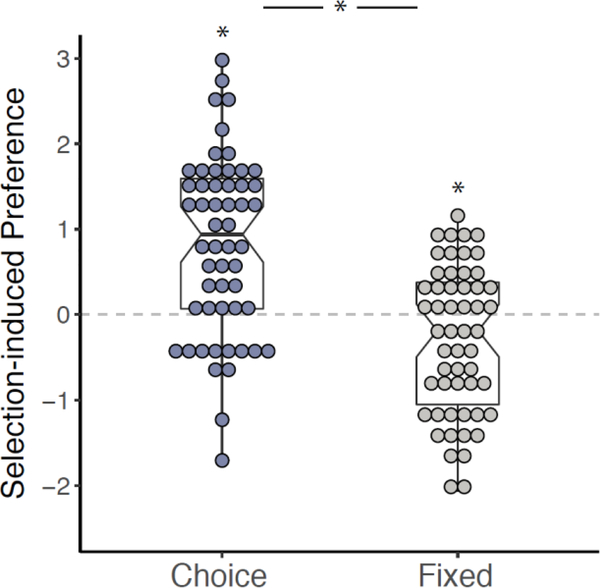

Selection-Induced Preference

Next, we wanted to investigate whether the opportunity to choose enhanced selection-induced preference, operationalized as whether more selections of an occluder screen during encoding increases participants’ preference for the hiragana character appearing on that specific occluder screen relative to its pre-encoding rating. Selection-induced preference was indeed greater in the choice versus fixed condition (t(53) = 5.72, p < 0.001, d = 0.78, Figure 3). Post-hoc tests revealed that selection-induced preference enhancement in the choice condition was also significantly greater than baseline (t(53) = 5.77, p < 0.001), indicating that the number of times an occluder screen was chosen during encoding did positively influence its preference rating. Conversely, selection- induced preference in the fixed condition was below baseline (t(53) = −2.54, p < 0.05), indicating that more frequent instructed selections actually reduced preference ratings.

Figure 3.

Selection-induced preference (i.e., change in preference ratings from pre- to post-encoding as a function of the number of times occluder screens were selected) in the choice and fixed conditions. * p < 0.05

Notably, positive preference changes for hiragana characters could not be explained simply by their appearance in the choice condition, as there was no overall difference between preference ratings for hiragana characters in the choice and fixed conditions (t(53) = 0.99, p = 0.33). Instead, this suggests that rather than having a general increase in preference for any of the characters that they were able to choose, there was a specific relationship between preference change and number of times characters were actively selected.

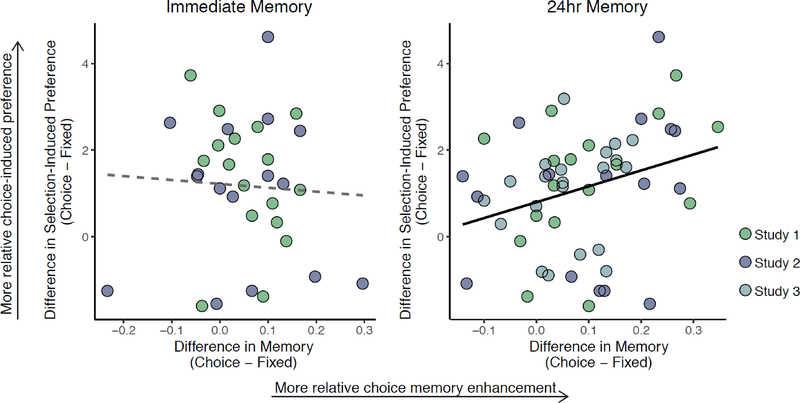

Relationships between choice’s influence on memory and preference

In the principal analysis, we tested for a relationship between choice’s influence on long-term memory and selection-induced preference using an individual differences approach. We found a significant positive relationship between choice-memory benefits on the 24-hour memory test and choice-related increases in selection-induced preference (r2(53) = 0.09, p < 0.05, Figure 4). A post-hoc power analysis indicated power of 0.60 to detect this effect. Correlations for the choice and fixed conditions separately showed a significant positive relationship between 24- hour memory and selection-induced preference in the choice condition (r2(53) = 0.12, p < 0.05) but not the fixed condition (r2(53) = 0.01, p = 0.61). This suggests that when given the opportunity to choose, people who show greater choice-induced preference for actively selected Hiragana characters are also more likely to show choice-related enhancement of long-term memory. This effect was not present at the individual trial level, as a within-subject regression between the ratings change for a particular character and memory for the associated items showed no significant relationship in either the choice (t(50) = −.76, p = .45) or fixed (t(50) = − 1.23, p = .22) conditions or when comparing conditions (t(50) = −.008, p = .99).

Figure 4.

Relationship between choice memory enhancements (choice minus fixed corrected recognition) for day 1 (left) and day 2 (right) and selection-induced preference differences between conditions (choice minus fixed). The different shades of blue and green represent data drawn from different studies. Solid line p < 0.05. Dashed line p > 0.05.

Next, we asked if this relationship between choice’s influence on memory and selection-induced preference was also evident at the immediate test, limiting our analysis to the sub-group of participants that completed both immediate and 24-hour memory tests (n=33). Despite reducing power to detect our main result to 0.39, this subgroup showed no change in effect size with a statistical trend for the relationship between choice-related memory enhancements at the 24- hour memory test and choice-related increases in selection induced preference (r2(32) = 0.09, p = 0.08). By contrast, choice-related enhancements in memory performance at the immediate test was not associated with choice-related increases in selection-induced preference (r2(32) = 0.003, p = 0.76, Figure 4). In order to test whether selection-induced preference influenced 24-hour memory significantly more than day 1 memory, we directly compared these relationships (Steiger, 1980), but found no significant difference (z(32) = 1.46, p = 0.14).

Finally, to consider the possibility that one of the three groups combined for the 24-hour memory analyses was driving the relationship between choice-memory benefits and choice-related increases in selection-induced preference, we ran a multiple regression with group as a between-subjects factor. The relationship between choice-memory benefits and selection- induced preference remained significant when controlling for study (β(53) = 0.02, p < 0.05), suggesting that group differences in preference and/or memory are not artificially driving this across-subject relationship.

Discussion

In this study, we used an individual differences approach to investigate the relationship between choice-induced memory enhancements and choice-induced preference. We found a positive relationship between these measures across subjects, suggesting as association between the influence of the opportunity to choose on memory and preference. The results from this study are consistent with a value-based account in which the intrinsic value of choice increases preference for chosen items (Hiragana characters) and enhances long-term memory for the outcomes of those choices (object images). The finding that the relationship between preference change and memory benefits only emerges after a delay provides further evidence for a value-based mechanism, as monetary value has been shown to specifically enhance memory through consolidation-dependent processes (Murayama & Kitagami, 2014; Murayama & Kuhbandner, 2011; Patil et al., 2017). The lack of a relationship between preference and memory at the item level suggests that individual differences drives the observed relationship, whereby sensitivity to agency may induce a state that separately guides memory and preference changes.

It is important to note that neither differences in looking times nor motor demands could drive the observed memory benefits. Eye-tracking data collected for Study 2 (reported in Murty, DuBrow, & Davachi, 2015) revealed that individuals actually spent more time looking at the target objects in the fixed versus choice condition. The motor demands were matched in the two conditions, and, importantly, were insufficient to enhance preference. Rather, only when individuals exerted agency over their choices did selections increase preference. This is in line with previous work that has shown that active relative to passive encoding, in terms of motor actions, does not benefit memory unless there is a volitional component (Voss, Gonsalves, et al., 2011). Together, these data suggest that imbuing individuals with a sense of agency may be an important component of active learning that is sufficient to enhance memory.

In addition to the effects on memory, we replicated prior findings that giving individuals the opportunity to choose enhances preference. Interestingly, the current analyses show that screens that were selected more frequently in the fixed condition, per the instructions, actually decreased in preference from pre to post-encoding. These results build upon a growing literature showing that withholding agency from individuals may result in devaluation (Leotti et al., 2010). Leotti and colleagues state that because people value the opportunity to choose, it can be aversive when perceived control is taken away. In our paradigm, participants experienced interleaved choice and fixed trials such that fixed trials may have been perceived as the removal of control. Indeed, decreases in preference for selected items on fixed trials relative to baseline suggest that the lack of choice may have been aversive. Open questions remain, however, as to the mechanism driving this negative selection-induced preference and whether this devaluation is related to lower memory in the fixed condition. Because the fixed condition served as our baseline in the memory task, we cannot evaluate whether selecting items in the fixed condition would have decreased memory relative to passive encoding. However, it is unlikely that memory differences would be driven by impairments from the removal of control, as aversive states do not necessarily cause memory impairments and in many instances can actually enhance memory (LaBar & Cabeza, 2006; Murty & Adcock, 2017).

Our current behavioral findings dovetail with an emerging neuroimaging literature investigating the neurocognitive mechanisms underlying choice. In particular, cues that signal the opportunity to choose have been shown to recruit reward-sensitive brain regions including the midbrain and ventral striatum during the anticipation of choice (Leotti & Delgado, 2011). Moreover, we have shown that a similar striatal signal at choice cues correlates with later memory for choice outcomes (Murty et al., 2015), and that relationship is mediated by post-encoding consolidation processes, specifically in the choice condition (Murty et al., 2018). We extend these prior neuroimaging findings by demonstrating that the opportunity to choose is also associated with behavioral measures of value (i.e., choice-induced preference) and find that this expression of choice value predicts choice-enhancements in long-term memory across individuals. Thus, together these data are consistent with a model by which a sense of agency may enhance memory for choice outcomes by engaging anticipatory value-based processes.

Theories regarding how a sense of agency over one’s environment arises tend to focus on interpreting causal relationships between one’s actions and subsequent observed outcomes (Haggard & Tsakiris, 2009). However, as noted above, the action-outcome contingency involved in the selection and object reveal in the fixed condition was insufficient to drive positive selection-induced preference. An alternative account suggests that one’s sense of agency may be prospective, imbued by monitoring selection processes in anticipation of an action, independent of outcomes (Metcalfe & Greene, 2007). Findings that behavioral and neural signatures of agency are modulated by anticipatory processes support this account (Chambon, Sidarus, & Haggard, 2014; Wenke, Fleming, & Haggard, 2010). Thus, one possibility is that anticipatory processes related to agency induce a heightened encoding state such that items encountered in that state will show better long-term memory. This parallels motivated memory research in which explicit monetary rewards and intrinsic curiosity have been shown to enhance memory through anticipatory processes (Miendlarzewska et al., 2016; Murty & Adcock, 2017, Gruber & Ranganath, 2019). As agency has also been proposed to be inherently rewarding (Leotti & Delgado, 2011) and enhance intrinsic motivation (Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008), it is possible that agency enhances preference and memory through a similar anticipatory value state as monetary and curiosity-driven encoding.

Our findings also help provide a better understanding of how decision-making more generally may influence learning and memory. While a large body of research has investigated interactions between choice and learning, these interactions have predominantly been studied using classic decision-making tasks that are poorly suited to study episodic memory, as reward cues are usually repeated many times. Only a few studies have investigated how reinforcement learning and decision-making influence single-shot memory encoding. In two such studies, outcome signals (e.g., prediction error), but not anticipatory cue value, influenced memory encoding (Rouhani, Norman, & Niv, 2018; Wimmer, Braun, Daw, & Shohamy, 2014). At first glance, this may seem at odds with our current results, which focus on the mnemonic benefits of increased value in the anticipation of making a choice rather than feedback-related effects. However, one possibility is that attention may be biased towards uncertain outcomes (Pearce & Hall, 1980) in tasks that require learning through feedback. By contrast, in the present study there was no reward feedback to learn from and thus no competition for attentional resources. This may explain the clear effects of anticipatory value on memory here as well as in other tasks that do not require value learning. Future work will be necessary to characterize how agency might influence memory in tasks that do require value learning or actively manipulate uncertainty within choice-based paradigms.

In sum, the present data demonstrate a relationship between choice-induced preference and choice memory enhancements that emerges after a delay. This relationship suggests that this association affects memory through a consolidation-dependent process. Thus, we argue that anticipation of value at the cue engages reward circuitry that leads to enhanced long-term memory for outcomes. More work is needed to test this account, e.g., by making choice aversive, characterizing the timecourse of the memory benefits, and investigating how individual differences in agency-induced stress influence memory. Regardless, the present data may have important implications for education, suggesting that simple interventions that enhance active learning without significantly altering content may lead to better long-term retention.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by R01 MH074682. VPM is supported by K01 MH111991. We also want to thank Lila Davachi for her support in experiment design and data collection.

Footnotes

Open Practices Statement

The data and materials for all experiments are available at https://osf.io/jmt4q/. None of the experiments were pre-registered.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References Cited

- Ariely D, & Norton MI (2008). How actions create--not just reveal--preferences. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(1), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.tics.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambon V, Sidarus N, & Haggard P (2014). From action intentions to action effects: how does the sense of agency come about? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 320 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara J, Usui N, Park SQ, Williams T, lijima T, Taira M, ... Tobler PN (2013).Value of freedom to choose encoded by the human brain. Journal of Neurophysiology, 110(8), 1915–1929. 10.1152/jn.01057.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber MJ & Rangnath C (2019). How curiosity enhances hippocampus-dependent memory.OSF Preprints. May 30, doi: 10.31219/osf.io/5v6nm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber MJ, Ritchey M, Wang S-F, Doss MK, & Ranganath C (2016). Post-learning Hippocampal Dynamics Promote Preferential Retention of Rewarding Events. Neuron, 89(5), 1110–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016yj.neuron.2016.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureckis TM, & Markant DB (2012). Self-Directed Learning: A Cognitive and Computational Perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 7(5), 464–481. 10.1177/1745691612454304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggard P, & Tsakiris M (2009). The Experience of Agency: Feelings, Judgments, and Responsibility. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(4), 242–246. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01644.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MJ, Hsu M, Krajbich IM, Loewenstein G, McClure SM, Wang JT, & Camerer CF (2009). The wick in the candle of learning: epistemic curiosity activates reward circuitry and enhances memory. Psychological Science, 20(8), 963–973. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02402.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornell N, & Metcalfe J (2006). Study efficacy and the region of proximal learning framework. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 32(3), 609–622. 10.1037/0278-7393.32.3.609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornell N, & Son LK (2009). Learners’ choices and beliefs about self-testing. Memory (Hove, England), 17(5), 493–501. 10.1080/09658210902832915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leotti LA, & Delgado MR (2011). The inherent reward of choice. Psychological Science, 22(10), 1310–1318. 10.1177/0956797611417005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leotti LA, & Delgado MR (2014). The value of exercising control over monetary gains and losses. Psychological Science, 25(2), 596–604. 10.1177/0956797613514589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leotti LA, Iyengar SS, & Ochsner KN (2010). Born to Choose: The Origins and Value of the Need for Control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(10), 457–463. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.tics.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markant D, DuBrow S, Davachi L, & Gureckis TM (2014). Deconstructing the effect of self-directed study on episodic memory. Memory & Cognition, 42(8), 1211–1224. 10.3758/s13421-014-0435-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin CB, & Shohamy D (2016). Curiosity and reward: Valence predicts choice and information prediction errors enhance learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 145(3), 266–272. 10.1037/xge0000140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J, & Greene MJ (2007). Metacognition of agency. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 136(2), 184–199. 10.1037/0096-3445.136.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miendlarzewska EA, Bavelier D, & Schwartz S (2016). Influence of reward motivation on human declarative memory. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 61, 156–176. https://doi.org/10.10167j.neubiorev.2015.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama K, & Kitagami S (2014). Consolidation power of extrinsic rewards: reward cues enhance long-term memory for irrelevant past events. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 143(1), 15–20. 10.1037/a0031992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama K, & Kuhbandner C (2011). Money enhances memory consolidation--but only for boring material. Cognition, 119(1), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.10167j.cognition.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murty VP, & Adcock RA (2017). Distinct Medial Temporal Lobe Network States as Neural Contexts for Motivated Memory Formation In The Hippocampus from Cells to Systems (pp. 467–501). Springer, Cham: 10.1007/978-3-319-50406-3_15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murty VP, DuBrow S, & Davachi L (2015). The simple act of choosing influences declarative memory. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 35(16), 6255–6264. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4181-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murty VP, DuBrow S, & Davachi L (2018). Decision-making Increases Episodic Memory via Postencoding Consolidation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 1–10. 10.1162/jocn_a_01321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairne JS, Pandeirada JNS, & Thompson SR (2008). Adaptive Memory: The Comparative Value of Survival Processing. Psychological Science, 19(2), 176–180. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairne JS, Thompson SR, & Pandeirada JNS (2007). Adaptive memory: Survival processing enhances retention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 33(2), 263–273. 10.1037/0278-7393.33.2.263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patall EA, Cooper H, & Robinson JC (2008). The effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes: a meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 270–300. 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil A, Murty VP, Dunsmoor JE, Phelps EA, & Davachi L (2017). Reward retroactively enhances memory consolidation for related items. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 24(1), 65–69. 10.1101/lm.042978.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce JM, & Hall G (1980). A model for Pavlovian learning: variations in the effectiveness of conditioned but not of unconditioned stimuli. Psychological Review, 87(6), 532–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotem-Turchinski N, Ramaty A, & Mendelsohn A (2018). The opportunity to choose enhances long-term episodic memory. Memory, 0(0), 1–10. 10.1080/09658211.2018.1515317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhani N, Norman KA, & Niv Y (2018). Dissociable effects of surprising rewards on learning and memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 44(9), 1430–1443. 10.1037/xlm0000518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH (1980). Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 87(2), 245–251. 10.1037/0033-2909.87.2.245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voss JL, Gonsalves BD, Federmeier KD, Tranel D, & Cohen NJ (2011).Hippocampal brain-network coordination during volitional exploratory behavior enhances learning. Nature Neuroscience, 14(1), 115–120. 10.1038/nn.2693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss JL, Warren DE, Gonsalves BD, Federmeier KD, Tranel D, & Cohen NJ (2011). Spontaneous revisitation during visual exploration as a link among strategic behavior, learning, and the hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(31), E402–409. 10.1073/pnas.1100225108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenke D, Fleming SM, & Haggard P (2010). Subliminal priming of actions influences sense of control over effects of action. Cognition, 115(1), 26–38. 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.10.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer GE, Braun EK, Daw ND, & Shohamy D (2014). Episodic memory encoding interferes with reward learning and decreases striatal prediction errors. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 34(45), 1490114912 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0204-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]