Abstract

Objective.

To determine the distribution of adult and pediatric American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM) Diplomates relative to the prevalence of obesity by U.S. state.

Methods.

We used data from the ABOM physician directory to determine originating specialty and U.S. state. We labeled physician specialty as “adult medicine” physicians (i.e., internal medicine, family medicine or medicine-pediatrics), “pediatric medicine” physicians (i.e., pediatrics, family medicine or medicine-pediatrics), and “other physicians” (i.e., surgical specialty, other specialty, or unknown). We used prevalence, by state, of obesity for adults in 2017, adolescents in 2017, and children in 2014 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We conducted counts of ABOM-certified adult medicine physicians and pediatric medicine physicians relative to obesity prevalence by state.

Results.

We included 2,577 U.S.-based ABOM-certified physicians – 79% from adult medicine, 38% from pediatric medicine, and 15% from other fields. All U.S. states had more than 1 adult medicine ABOM-certified physician, although geographic disparities existed in physician availability relative to obesity prevalence. Fewer pediatric medicine ABOM Diplomates were available in all states.

Conclusions.

Promotion of ABOM training and certification in certain geographic locations and among pediatric physicians may help address disparities in ABOM Diplomate availability relative to obesity burden.

Keywords: Obesity Management, Medical Education, Medical Geography, Obesity

Introduction

In the United States, the prevalence of obesity among adults is 39% and 18% for youth ages 2 to 19 years (1–2). Projections estimate that obesity will affect 51% of U.S. adults by 2030 (3). Notably, obesity does not impact all areas of the U.S. the same, as disparities in obesity prevalence have been documented across U.S. states and regions (4–5). Typically, surveys that estimate body mass index (BMI) from self-reported height and weight identify that the South and Midwest regions of the U.S. have the greatest burden of obesity (4).

Obesity has been associated with an increased risk of death and morbidity including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, kidney disease, and certain cancers (6). In 2013, the American Medical Association (AMA) recognized obesity as a complex, chronic disease that requires medical attention (7). However, research has found that the rate of obesity counseling among practicing physicians is low (8–9).

Physicians receive little education or training to appropriately address obesity in the clinical setting. Competencies taught in medical school and internal medicine residency have identified obesity and nutrition as major knowledge gaps (10–13). Practicing primary care physicians’ have repeatedly identified insufficient training about obesity, as well as low confidence and self-efficacy with respect to weight management skills (14–16). Despite these limitations, prior research has found that patients want their physician involved in their weight-loss plan (17), and patients have greater weight-loss success in this scenario (18). This evidence indicates a role for physicians in the care of patients with obesity, but it also highlights the need for education and training on obesity.

In 2011, certification from the American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM) was established to address this gap in education and training in obesity (19). The organization merged two prior certification pathways (American Board of Bariatric Medicine and Certified Obesity Medicine Physician), as well as established requirements regarding obesity education and testing procedures to ensure that certified physicians have achieved competency in the science of and evidence-based treatments for obesity (20). Physicians either complete an obesity medicine fellowship or 60 hours of continuing medical education (CME) activities to be eligible for the ABOM examination – the first of which occurred in 2012. A 5-year report on ABOM Diplomates found that mean age was 47 years, 53% were women, and 66% originated from internal medicine or family medicine (20). Of the 2,068 Diplomates in 2017, 504 practiced in the Northeast U.S., 674 in the South, 453 in the Midwest, 394 in the West, and 40 in Canada.

In this study, our objective was to determine the number and type of ABOM Diplomates in the U.S. geographically, and examine ABOM-certified physician availability relative to the prevalence of obesity among adults, adolescents, and children by U.S. state.

Methods

For this descriptive study, we compiled data from several sources including the ABOM directory of certified physicians, obesity medicine fellowship alumni directory, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and Youth Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (YBRFSS), and the U.S. Census Bureau. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board exempted this research.

Physician variables

We conducted a retrospective analysis of data from the ABOM directory of certified physicians, which is freely available online (21). We used this directory to export information about all U.S. Diplomates as of February 22, 2019. The variables used in this analysis are described below.

The ABOM directory lists the prior training certifications for each physician, which includes primary specialty (e.g., internal medicine, general surgery), and if available, additional specialty training (e.g., endocrinology). Primary specialty was available for most physicians in the database (95%). We were able to identify specialty when missing for 121 individuals by searching online (Doximity and Google), although we could not identify specialty for 9 physicians (>99% completeness). We used this information to categorize physician specialty in several ways. First, we created broad categories of all adult medicine physicians, all pediatric medicine physicians, and all other physicians. “All adult medicine” included physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine or internal medicine-pediatrics. “All pediatric medicine” included physicians trained in pediatrics, family medicine or internal medicine-pediatrics. “All other” included surgical, other specialty (e.g., dermatology) or unknown training background. Of note, adult medicine and pediatric medicine labels are not mutually exclusive. Second, we created detailed categorization by: primary care adult (internal medicine trained physicians without other specialization), specialty adult (physicians with both internal medicine and other specialty board certification), primary care pediatrics trained physicians without other specialization), specialty pediatrics (physicians with both pediatrics and other specialty board certification), primary care adult-pediatrics (family medicine and internal medicine-pediatrics physicians without other specialization), specialty adult-pediatrics (physicians from these domains that also have additional specialty board certification), surgical, or other. “Surgical” included general surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, cardiothoracic surgery, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, and urology; and “Other” included anesthesiology, dermatology, emergency medicine, nuclear medicine, occupational medicine, pathology, physical medicine & rehabilitation, preventive medicine, psychiatry & neurology, and radiology.

We were able to identify each physician’s location by state from the ABOM directory. We grouped states into census regions as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau (22). Northeast region includes Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. Midwest region includes Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota. South includes Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas. West includes Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington. We also examined data by individual state.

The ABOM directory also contained initial year of obesity medicine certification. We estimated years of obesity medicine practice by subtracting the year of obesity medicine certification from 2019. Of note, other physician demographics such as age, gender, and race and clinical practice characteristics such as percent time practicing obesity medicine were unavailable. Additionally, we identified physicians that completed fellowship training in obesity medicine in our sample from a roster of fellowship alumni that is freely available online and location of obesity medicine fellowship programs (23).

Obesity prevalence

Using estimates calculated from BRFSS and YBRFSS, we reported prevalence, by state, of obesity for adults (age 18 or older) in 2017, adolescents (defined as students in grades 9–12) in 2017, and children (defined as age 2–4 years participating in the Women, Infants, and Children Program) in 2014 (24). We used data from the U.S. Census Bureau to report the total population of each state in 2017 (25). Finally, we approximated the number of adults with obesity per adult medicine ABOM-certified physician in each state – ABOM-certified adult medicine physician availability – through several calculations. We first estimated the number of adults with obesity in each state by multiplying each state’s 2017 total adult population by 2017 adult obesity prevalence (26), which we then divided by the number of adult medicine ABOM-certified physicians in that state. We did not similarly estimate ABOM-certified pediatric medicine physicians available, as we could not reliably approximate number of children with obesity in each as states report total population under 18 in a given year, the prevalence of adolescent and child obesity were captured in different years, and not all states reported adolescent obesity.

Analyses

We used Chi2 tests to compare differences between regions in the proportions of each physician specialty (e.g., primary care adult, specialty adult). To compare differences between regions, we used ANOVA for the mean years of obesity medicine practice and Chi2 test for proportion of obesity medicine fellowship trained physicians. Finally, we conducted counts of all adult medicine physicians, all pediatric medicine physicians, and all other physicians by state, which we report alongside information on obesity prevalence and total population size. We also report approximate ABOM-certified adult medicine physician availability.

Results

Overall, we included 2,577 U.S.-based physicians available in the ABOM online directory that were certified as of February 2019. Of these physicians, 2,033 (79%) had training in an adult medicine discipline, 987 (38%) had training in a pediatric medicine discipline, and 385 (15%) had training in surgical or other fields (e.g., emergency medicine). Mean years in obesity medicine practice were 4.6 (SD 5.0), and only 1% had completed obesity medicine fellowship training.

Distribution of physicians varied by region – 22% were located in the Northeast, 23% in the Midwest, 36% in the South, and 19% in the West. Table 1 shows the distribution of physician specialty by region. There were significant differences between regions with respect to availability of primary care adult physicians, primary care adult-pediatrics physicians, specialty pediatricians, and other physicians – where typically there were fewer physicians in these areas available in the West as compared to other regions. We did find a significant difference in years of obesity practice by region – 4.0 years in the Northeast, 4.6 years in the Midwest, 4.9 years in the South, and 5.0 years in the West (p<0.01). Most obesity medicine fellowship trained physicians were located in the Northeast (4%) as compared to the other regions (all less than 1%)(p<0.01).

Table 1.

Number of ABOM Diplomates by U.S. Census Region and Specialty*

| N (%) | Region** | p-value*** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast | Midwest | South | West | ||

| Primary Care Adult | 250 (27) | 200 (22) | 297 (32) | 178 (19) | <0.01 |

| Specialty Adult | 74 (26) | 64 (23) | 88 (31) | 54 (19) | 0.21 |

| Primary Care Pediatrics | 39 (28) | 27 (20) | 52 (38) | 19 (14) | 0.14 |

| Specialty Pediatrics | 9 (41) | 2 (9) | 10 (45) | 1 (5) | 0.04 |

| Primary Care Adult-Pediatrics | 130 (16) | 215 (26) | 304 (37) | 163 (20) | <0.01 |

| Specialty Adult-Pediatrics | 3 (19) | 1 (6) | 8 (50) | 4 (25) | 0.36 |

| Surgical | 49 (22) | 56 (25) | 92 (41) | 28 (12) | 0.06 |

| Other | 15 (10) | 25 (17) | 69 (36) | 42 (19) | <0.01 |

Abbreviations: ABOM – American Board of Obesity Medicine.

Primary care adult includes internal medicine trained physicians without other specialization, whereas specialty adult includes physicians with both internal medicine and other specialty board certification (e.g., endocrinology). Primary care pediatrics includes pediatrics trained physicians without other specialization, whereas specialty pediatric includes physicians with both pediatrics and other specialty board certification. Primary care adult-pediatrics includes family medicine and internal medicine-pediatrics physicians without other specialization, whereas specialty adult-pediatrics includes physicians from these domains that also have additional specialty board certification. Surgical includes general surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, cardiothoracic surgery, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, and urology. “Other” includes the following specialties: anesthesiology, dermatology, emergency medicine, nuclear medicine, occupational medicine, pathology, physical medicine & rehabilitation, preventive medicine, psychiatry & neurology, and radiology. Of note, no specialty was reported for 9 physicians (0 Northeast; 2 Midwest; 7 South; 0 West).

States grouped into regions as defined by the US Census Bureau (22).

p-values calculated from Chi2tests comparing row proportions between region.

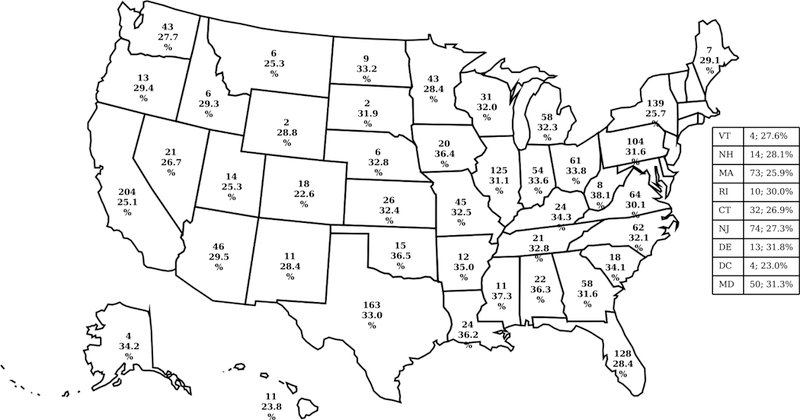

All states have more than 1 adult medicine ABOM-certified physician (Figure 1), although the number of available Diplomates does not necessarily reflect the burden of obesity in the state (Table 2). For example, Kansas had 26 Diplomates and an adult obesity prevalence of 32.4% (approximately 1 adult medicine ABOM Diplomate for every 27,423 adults with obesity), whereas Nebraska had 6 Diplomates and an adult obesity prevalence of 32.8% (approximately 1 adult medicine ABOM Diplomate for every 78,957 adults with obesity). Geographic disparities existed in availability of adult medicine ABOM Diplomates for adults with obesity (Table 3) – South Dakota had approximately 1 adult medicine ABOM Diplomate per 104,442 adults with obesity as compared to Delaware which had 1 adult medicine ABOM Diplomate per 18,529 adults with obesity. Only 5 states had adult obesity medicine fellowship programs (Table 2).

Figure 1. Number of ABOM Diplomates from Adult Medicine Specialties and Prevalence of Adult Obesity by State.

For each state, top number represents the number of Adult Medicine ABOM Diplomates as of February 2019 and the bottom number represents the prevalence of adult obesity (aged 18 or older) in 2017. Adult Medicine ABOM Diplomates include physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine or internal medicine-pediatrics. All physician information, including specialty and location, abstracted from the ABOM online directory of Diplomates (21). Adult obesity prevalence determine from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (24). Abbreviations: ABOM – American Board of Obesity Medicine.

Table 2.

Obesity Prevalence by Age Group & State; ABOM Diplomates by Specialty* & State; Obesity Medicine Fellowships by State

| 2017 Total Population** | Obesity Prevalence*** (%) | Number ABOM Diplomates | Number & Type of Obesity Medicine Fellowship Programs**** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 Adult | 2017 Adolescent | 2014 Child | All Adult Medicine | All Pediatric Medicine | All Other | |||

| Alabama | 4,874,747 | 36.3 | NR | 16.3 | 22 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| Alaska | 739,795 | 34.2 | 13.7 | 19.1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Arizona | 7,016,270 | 29.5 | 12.3 | 13.3 | 46 | 23 | 8 | 0 |

| Arkansas | 3,004,279 | 35.0 | 21.7 | 14.4 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 0 |

| California | 39,536,653 | 25.1 | 13.9 | 16.6 | 204 | 81 | 30 | 0 |

| Colorado | 5,607,154 | 22.6 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 18 | 12 | 3 | 0 |

| Connecticut | 3,588,184 | 26.9 | 12.7 | 15.3 | 32 | 10 | 4 | 0 |

| Delaware | 961,939 | 31.8 | 15.1 | 17.2 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 1 Pediatric |

| District of Columbia | 693,972 | 23.0 | 16.8 | 13.0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Florida | 20,984,400 | 28.4 | 10.9 | 12.7 | 128 | 63 | 31 | 0 |

| Georgia | 10,429,379 | 31.6 | NR | 13.0 | 58 | 35 | 13 | 0 |

| Hawaii | 1,427,538 | 23.8 | 14.2 | 10.3 | 11 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Idaho | 1,716,943 | 29.3 | 11.4 | 11.6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Illinois | 12,802,023 | 31.1 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 125 | 55 | 19 | 0 |

| Indiana | 6,666,818 | 33.6 | NR | 14.3 | 54 | 28 | 11 | 0 |

| Iowa | 3,145,711 | 36.4 | 15.3 | 14.7 | 20 | 11 | 4 | 0 |

| Kansas | 2,913,123 | 32.4 | 13.1 | 12.8 | 26 | 11 | 4 | 0 |

| Kentucky | 4,454,189 | 34.3 | 20.2 | 13.3 | 24 | 15 | 5 | 0 |

| Louisiana | 4,684,333 | 36.2 | 17.0 | 13.2 | 24 | 15 | 8 | 0 |

| Maine | 1,335,907 | 29.1 | 14.3 | 15.1 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| Maryland | 6,052,177 | 31.3 | 12.6 | 16.5 | 50 | 24 | 12 | 0 |

| Massachusetts | 6,859,819 | 25.9 | 11.7 | 16.6 | 73 | 20 | 10 | 2 Adult |

| Michigan | 9,962,311 | 32.3 | 16.7 | 13.4 | 58 | 21 | 12 | 0 |

| Minnesota | 5,576,606 | 28.4 | NR | 12.3 | 43 | 33 | 8 | 0 |

| Mississippi | 2,984,100 | 37.3 | NR | 14.5 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| Missouri | 6,113,532 | 32.5 | 16.6 | 13.0 | 45 | 21 | 7 | 0 |

| Montana | 1,050,493 | 25.3 | 11.7 | 12.5 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Nebraska | 1,920,076 | 32.8 | 14.6 | 16.9 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Nevada | 2,998,039 | 26.7 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 21 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| New Hampshire | 1,342,795 | 28.1 | 12.8 | 15.1 | 14 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| New Jersey | 9,005,644 | 27.3 | NR | 15.3 | 74 | 27 | 13 | 0 |

| New Mexico | 2,088,070 | 28.4 | 15.3 | 12.5 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| New York | 19,849,399 | 25.7 | 12.4 | 14.3 | 139 | 59 | 19 | 2 Adult |

| North Carolina | 10,273,419 | 32.1 | 15.4 | 15.0 | 62 | 32 | 17 | 1 Adult |

| North Dakota | 755,393 | 33.2 | 14.9 | 14.4 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Ohio | 11,658,609 | 33.8 | NR | 13.1 | 61 | 37 | 11 | 1 Pediatric |

| Oklahoma | 3,930,864 | 36.5 | 17.1 | 13.8 | 15 | 11 | 6 | 0 |

| Oregon | 4,142,776 | 29.4 | NR | 15.0 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | 12,805,537 | 31.6 | 13.7 | 12.9 | 104 | 46 | 12 | 1 Adult |

| Rhode Island | 1,059,639 | 30.0 | 15.2 | 16.3 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| South Carolina | 5,024,369 | 34.1 | 17.2 | 12.0 | 18 | 7 | 10 | 0 |

| South Dakota | 869,666 | 31.9 | 12.7 | 17.1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tennessee | 6,715,984 | 32.8 | 20.5 | 14.9 | 21 | 16 | 10 | 1 Pediatric |

| Texas | 28,304,596 | 33.0 | 18.6 | 14.9 | 163 | 88 | 26 | 1 Adult |

| Utah | 3,101,833 | 25.3 | 9.6 | 8.2 | 14 | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| Vermont | 623,657 | 27.6 | 12.6 | 14.1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Virginia | 8,470,020 | 30.1 | 12.7 | 20.0 | 64 | 31 | 12 | 0 |

| Washington | 7,405,743 | 27.7 | NR | 13.6 | 43 | 25 | 12 | 0 |

| West Virginia | 1,815,857 | 38.1 | 19.5 | 16.4 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Wisconsin | 5,795,483 | 32.0 | 13.7 | 14.7 | 31 | 19 | 6 | 0 |

| Wyoming | 579,315 | 28.8 | NR | 9.9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Abbreviations: ABOM – American Board of Obesity Medicine; NR – not reported.

All adult medicine includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine or medicine-pediatrics. All pediatric medicine includes physicians trained pediatrics, family medicine or medicine-pediatrics. All other includes surgical, other specialty (e.g., dermatology) or unknown training background.

Total population obtained from U.S. Census Bureau (25).

Obesity prevalence data abstracted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System and Youth Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System, which report obesity for adults (age 18 or older), adolescents (defined as students in grades 9–12), and children (defined as age 2–4 years participating in the Women, Infants, and Children Program)(24).

Number of obesity medicine fellowships obtained from the Obesity Medicine Fellowship Council (23).

Table 3.

ABOM-Certified Adult Medicine Physician Availability by State, Ranked

| # of Adults with Obesity per 1 Adult Medicine ABOM Diplomate* | |

|---|---|

| Delaware | 18,529 |

| Massachusetts | 19,478 |

| North Dakota | 21,382 |

| New Hampshire | 21,758 |

| Connecticut | 23,910 |

| Hawaii | 24,272 |

| Illinois | 24,643 |

| Rhode Island | 25,569 |

| New Jersey | 25,923 |

| Kansas | 27,423 |

| Minnesota | 28,254 |

| New York | 29,019 |

| Nevada | 29,403 |

| Maryland | 29,451 |

| Pennsylvania | 30,813 |

| Virginia | 31,045 |

| Indiana | 31,692 |

| District of Columbia | 32,745 |

| Missouri | 34,165 |

| Arizona | 34,520 |

| Montana | 34,644 |

| Vermont | 34,971 |

| Washington | 37,105 |

| Florida | 37,236 |

| California | 37,498 |

| Utah | 39,308 |

| North Carolina | 41,270 |

| New Mexico | 41,309 |

| Texas | 42,391 |

| Georgia | 43,121 |

| Michigan | 43,358 |

| Iowa | 43,931 |

| Maine | 45,033 |

| Wisconsin | 46,584 |

| Alaska | 47,441 |

| Kentucky | 49,215 |

| Ohio | 50,165 |

| Louisiana | 53,937 |

| Colorado | 54,558 |

| Idaho | 62,172 |

| Alabama | 62,358 |

| Wyoming | 63,768 |

| Arkansas | 67,047 |

| West Virginia | 68,872 |

| Oklahoma | 72,308 |

| Oregon | 73,933 |

| South Carolina | 74,256 |

| Mississippi | 76,992 |

| Nebraska | 78,957 |

| Tennessee | 81,352 |

| South Dakota | 104,442 |

Abbreviations: ABOM – American Board of Obesity Medicine; NR – not reported.

We estimated the number of adults with obesity in each state by multiplying each state’s 2017 total adult population by adult obesity prevalence (26), which we then divided by the number of adult medicine ABOM-certified physicians in that state. All adult medicine includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine or medicine-pediatrics.

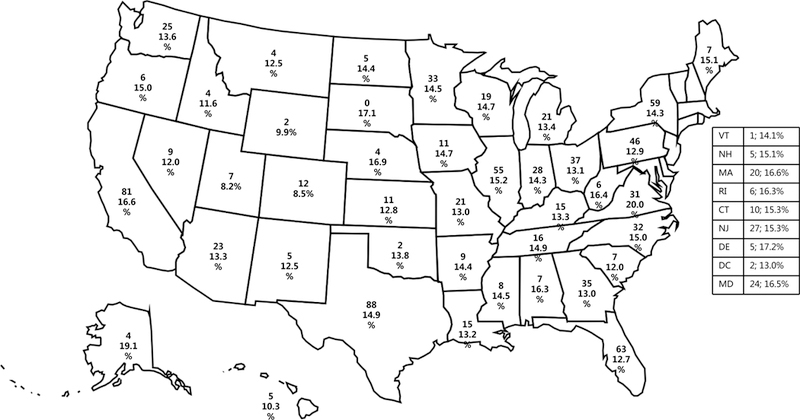

The number of pediatric medicine ABOM Diplomates was lower than adult medicine ABOM Diplomates across all states (Figure 2), and one state (South Dakota) had no ABOM-certified pediatric physicians (Table 2). Only 3 states had pediatric obesity medicine fellowship programs (Table 2).

Figure 2. Number of ABOM Diplomates from Pediatric Medicine Specialties and Prevalence of Childhood Obesity by State.

For each state, top number represents the number of Pediatric Medicine ABOM Diplomates as of February 2019 and the bottom number represents the prevalence of childhood obesity (defined as age 2–4 years participating in the Women, Infants, and Children Program) in 2014. Pediatric Medicine ABOM Diplomates include physicians trained in pediatrics, family medicine or internal medicine-pediatrics. All physician information, including specialty and location, abstracted from the ABOM online directory of Diplomates (21). Childhood obesity prevalence determine from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (24). Abbreviations: ABOM – American Board of Obesity Medicine.

Discussion

Since its inception in 2011, we found that ABOM has certified 2,577 physicians in obesity medicine in the United States as of February 2019 – which has risen from 2,028 U.S.-based ABOM Diplomates in 2017 (20). The 5-year report on ABOM did report the regions where ABOM-certified physicians practice (20), and our results extend this work by detailing the specialty background within regions as well as examining the distribution of physicians by state relative to the burden of obesity. Notably, we found that all states have adult medicine ABOM-certified physicians, and nearly all states have at least one pediatric medicine ABOM-certified physician. It is important to consider how the number of obesity medicine physicians compares to other similar specialty physicians. A study of endocrinologists identified 6,501 practicing adult endocrinologists and 1,203 pediatric endocrinologists in 2012 (27), and 7% of the U.S. population was estimated to have diabetes mellitus at that time (28). All states had at least one adult endocrinologist, but three states (Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming) had no pediatric endocrinologist. Relative to the availability of endocrinologists in 2012, more ABOM-certified physicians are likely needed to address obesity in the U.S.

With respect to regional differences, we found that the South had greater proportion of ABOM-certified physicians that had been trained in primary care adult medicine, specialty pediatrics, primary care adult-pediatrics, and other specialties. This higher number of physicians in the South U.S. may be helping to address the greater burden of obesity typically identified in this region (4), although we recognize that this number may still be insufficient to fully address the need. It is important to note that surveys that rely on self-reported BMI have also identified the Midwest region as having a burden of obesity nearly equivalent to the South (4), and U.S.-based surveys that measure BMI have actually found that the Midwest has the highest prevalence of obesity (5). While the Midwest region does not have the lowest numbers of ABOM-certified physicians, our results may highlight an opportunity to promote training and certification for physicians within this region to improve access to obesity medicine care in a region with substantial need. Establishment of obesity medicine fellowships in this region might be a mechanism to achieve this, as we found that currently most fellowship trained physicians are located in the Northeast.

While an adult medicine ABOM-certified physician is available in all states, we found differences in availability of these physicians by state. Availability ranged from 18,529 adults with obesity per ABOM Diplomate in Delaware to 104,442 adults with obesity per ABOM Diplomate in South Dakota. Disparities in availability of adult endocrinologists also varies by state, where the states in the Northeast and West have the greatest availability (27). With these current estimates of physician availability relative to the obesity burden, it is not feasible for these adult medicine ABOM-certified physicians to care for all adults with obesity in the state – even in the best case scenario. These findings raise the question of whether all individuals with obesity need to be evaluated and managed by an ABOM-certified physician. Prior research has found that physicians preparing for the ABOM exam differ from primary care physicians – they give higher effectiveness ratings of anti-obesity medications and bariatric surgery as treatments for obesity relative to primary care physicians, as well as place higher importance on biologic factors of obesity (29). In another study, primary care physicians, endocrinologists and cardiologists were often unfamiliar with obesity guidelines and many had unrealistic expectations for weight loss achieved with anti-obesity medications and bariatric surgery relative to bariatricians (30). These differences are likely related to a knowledge gap among physicians without obesity medicine training, as another trial demonstrated that educating primary care physicians increased their appreciation and use of evidence-based strategies for weight loss (31). Since many primary care physicians do not feel that they are the most qualified profession to help individuals with obesity lose weight (32), understanding which patients with obesity are best served by being treated by an ABOM-certified physician is critical – particularly as primary care clinicians become increasingly aware of obesity medicine as a referral option for their patients.

In general, we found fewer ABOM Diplomates with a pediatric background to treat children and adolescents with obesity. We note greater potential disparities in pediatric obesity medicine care, given that South Dakota has no pediatric medicine ABOM-certified physician and Vermont only has one. Disparities in availability of pediatric endocrinologists also varies by state, where the states in the Northeast and West have the greatest availability (27). Of note, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming had no pediatric endocrinologists in 2012. While the prevalence of childhood and adolescent obesity is lower than in adults, the number of pediatric medicine ABOM-certified physicians is unlikely to be able to meet the need. Of note, we included family medicine and internal medicine-pediatrics trained physicians in our group of pediatric medicine physicians, and it is unknown how much their time is actually dedicated to caring for children. Similar to the question raised by our findings in adults, is whether all children with obesity need to evaluated and managed by an ABOM-certified physician. Given that bariatric surgery is increasingly being considered for adolescents (33), promotion of ABOM training and certification of physicians from pediatric medicine may be warranted.

Based on our findings, we have suggested that the promotion of obesity medicine training and ABOM certification may need to occur in different regions of the U.S., as well as among pediatric medicine physicians. This action might be accomplished through several mechanisms. One strategy could be the establishment of obesity medicine fellowships in particular regions or fellowships specializing on training pediatric physicians. The Obesity Medicine Fellowship Council may have a role in the work, particularly given that they have requested applications for obesity medicine fellowship development grants (23). Another strategy might be the promotion of ABOM training and certification through physician groups with whom ABOM already has a partnership (19), such as regions/chapters of the American College of Physicians or chapters of the American Academy of Family Physicians. In addition, other physician groups with whom a partnership has yet to be established may also need to be engaged on a regional or state level, such as districts/chapters of the American Academy of Pediatrics. This second strategy would propose extending ABOM’s role beyond certifying physicians in obesity medicine to also include determining a strategic approach to improve access to obesity medicine physicians to address these disparities.

This research has several limitations. We relied upon freely available information from the ABOM database regarding ABOM-certified physicians, and we could not verify the accuracy of data elements. Physicians may move their clinical practice to another state or maintain practices in multiple states, and we were unable to determine these changes from the data available. We abstracted information about physicians’ originating specialty or specialties, which presented a few challenges. The database did have a small degree of missingness in this field, and we were able to identify training background for most individuals where this information was missing. The accuracy of the “specialty” designation for adult-pediatric physicians may be limited, as we suspect that physicians trained in internal medicine-pediatrics may have been unable to enter additional specialty training fields (as no internal medicine-pediatrics physicians endorsed additional training). While we identified physicians as providing adult or pediatric obesity care, we do not have access to the percent of their time dedicated to treating these populations for obesity. In the 5-year ABOM report, 38% spent less than 25% of their time in obesity medicine compared to 19% that spent greater than 75% of their time on obesity care (20). The data sources for this study did not contain information regarding the percent of clinical time a physician spends practicing obesity medicine. Integrating this information in future studies will be key, as this could highlight greater disparities if ABOM Diplomates in states with low rates are not spending most of their time practicing obesity medicine. ABOM only certifies physicians, therefore, this study cannot determine the prevalence of advanced practice providers (e.g., nurse practitioners or physician assistants) that provide obesity care. We used BRFSS and YBRFSS to estimate obesity prevalence rates in the US. Because both BRFSS and YBRFSS rely on self-reported data via telephone surveys, the percentage of US adults, adolescents, and children, may be under estimated by as much as 10% (5). We could not reliably estimate the ABOM-certified pediatric medicine physician availability, given the limitations of the U.S. census and YBRFSS data. Finally, we focused our analyses within the U.S. population; however, obesity has become a global problem. Future research might consider replicating our approach on a global scale with SCOPE Diplomates (34).

In conclusion, the number of ABOM Diplomates continues to grow – all states have adult medicine ABOM-certified physicians and nearly all states have at least one pediatric medicine ABOM-certified physician. With achievement of this benchmark, our results may help identify geographic locations – such as the Midwest – where promotion of ABOM training and certification through CME or fellowship mechanisms may be warranted to address disparities in ABOM Diplomate availability relative to obesity burden. In addition, increasing ABOM certification among more physicians who treat children and adolescents may also be helpful given the rates of obesity among these age groups.

What is already known about this subject?

The American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM) began certifying physicians in 2012

A 5-year report on ABOM Diplomates described demographics of 2,068 certified physicians

What does your study add?

All states have adult medicine ABOM-certified physicians

Nearly all states have at least one pediatric medicine ABOM-certified physician

Certain geographic locations – such as the Midwest – have disparities in ABOM Diplomate availability relative to obesity burden

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research received no direct funding support. KAG was supported from grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the National Institute for Mental Health under Award Numbers K23HL116601 and P50MH115842. FCS was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers P30DK040561 and L30DK118710. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the American Board of Obesity Medicine.

Footnotes

Disclosure: KAG, CTB, and FCS are certified Diplomates of the American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM), and VRJ is currently training in an obesity medicine fellowship. KAG serves on the ABOM examination item writing committee and is also a paid consultant to the American Board of Obesity Medicine. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. FCS is on the outreach and awareness committee for ABOM.

References

- 1.Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Aoki Y, Ogden CL. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographic characteristics and urbanization level among adults in the United States, 2013–2016. JAMA 2018; 319:2419–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, Carroll MD, Aoki Y, Freedman DS. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographics and urbanization in US children and adolescents, 2013–2016. JAMA 2018; 319:2410–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finkelstein EA, Khavjou OA, Thompson H, Trogdon JG, Pan L, Sherry B, et al. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am J Prev Med 2012; 42:563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult obesity prevalence maps Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html on March 26, 2019.

- 5.Le A, Judd SE, Allison DB, Oza-Frank R, Affuso O, Safford MM, et al. The geographic distribution of obesity in the US and the potential regional differences in misreporting obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014; 22:300–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Cause-specific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight and obesity. JAMA 2007; 298:2028–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyle TK, Dhurandhar EJ, Allison DB. Regarding obesity as a disease: Evolving policies and their implications. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2016; 45:511–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAlpine DD, Wilson AR. Trends in obesity-related counseling in primary care. Med Care 2007; 45:322–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleich SN, Pickett-Blakley O, Cooper LA. Physician practice patterns of obesity diagnosis and weight-related counseling. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 82:123–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Block JP, DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP. Are physicians equipped to address the obesity epidemic? Knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents. Prev Med 2003; 36:699–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH. Nutrition education in U.S. medical schools: latest update of a national survey. Acad Med 2010; 85:1537–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushner RF, Butsch WS, Kahan S, Machineni S, Cook S, Aronne LJ. Obesity coverage on medical licensing examinations in the United States. What is being tested? Teach Learn Med 2017; 29:123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devries S, Dalen JE, Eisenberg DM, Maizes V, Ornish D, Prasad A, et al. A deficiency of nutrition education in medical training. Am J Med 2014; 127:804–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med 1995; 24:546–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gudzune KA, Clark JM, Appel LJ, Bennett WL. Primary care providers’ communication with patients during weight counseling: a focus group study. Patient Educ Couns 2012; 89:152–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. National survey of US primary care physicians’ perspectives about causes of obesity and solutions to improve care. BMJ Open 2012; 2:e001871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett WL, Wang NY, Gudzune KA, Dalcin AT, Bleich SN, Appel LJ, Clark JM. Satisfaction with primary care provide involvement is associated with greater weight loss: results from the practice-based POWER trial. Patient Educ Couns 2015; 98:1099–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gudzune KA, Bennett WL, Cooper LA, Bleich SN. Perceived judgment about weight can negatively influence weight loss: a cross-sectional study of overweight and obese patients. Prev Med 2014; 62:103–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Board of Obesity Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.abom.org/ on March 26, 2019.

- 20.Kushner RF, Brittan D, Cleek J, Hes D, English W, Kahan S, et al. The American Board of Obesity Medicine: Five-year report. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017; 25:982–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Board of Obesity Medicine. Diplomate Search and Certification Verification Retrieved from https://abom.learningbuilder.com/public/membersearch on March 26, 2019.

- 22.U.S. Census Bureau. Geographic terms and concepts – census divisions and census regions Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html on March 26, 2019.

- 23.Obesity Medicine Fellowship Council. Retrieved from https://omfellowship.org/ on May 1, 2019.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity: Data, Trends and Maps Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/data-trends-maps/index.html on March 26, 2019.

- 25.U.S. Census Bureau. Quick facts Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US on March 26, 2019.

- 26.U.S. Census Bureau. State Population by Characteristics: 2010–2017 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popest/state-detail.html on March 26, 2019.

- 27.Lu H, Holt JB, Cheng YJ, Zhang X, Onufrak S, Croft JB. Population-based geographic access to endocrinologists in the United States, 2012. BMC Health Services Research 2015; 15:541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabtes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:1033–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai AG, Histon T, Kyle TK, Rubenstein N, Donahoo WT. Evidence of a gap in understanding obesity among physicians. Obe Sci Pract 2018; 4:46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glauser TA, Roepke N, Stevenin B, Dubois AM, Ahn SM. Physician knowledge about and perceptions of obesity management. Obes Res Clin Pract 2015; 9:573–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwamoto S, Saxon D, Tsai A, Leister E, Speer R, Heyn H, et al. Effects of education and experience on primary care providers’ perspectives of obesity treatments during a pragmatic trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018; 26:1532–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, Cooper LA. National survey of US primary care physicians’ perspectives about causes of obesity and solutions to improve care. BMJ Open 2012; 2:e001871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai WS, Inge TH, Burd RS. Bariatric surgery in adolescents: Recent national trends in use and in-hospital outcome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007; 161:217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Obesity Federation. SCOPE Retrieved from https://www.worldobesity.org/training-and-events/training/scope on March 26, 2019.