Abstract

We report the first evidence of GEX1A, a polyketide known to modulate alternative pre-mRNA splicing, as a potential treatment for Niemann-Pick type C disease. GEX1A was isolated from its producing organism, Streptomyces chromofuscus, and screened in NPC1 mutant cells alongside several semi-synthetic analogues. We found that GEX1A and analogues are capable of restoring cholesterol trafficking in NPC1 mutant fibroblasts, as well as altering the expression of NPC1 isoforms detected by Western blot. These results, along with the compound’s favorable pharmacokinetic properties, highlight the potential of spliceosome-targeting scaffolds such as GEX1A for the treatment of genetic diseases.

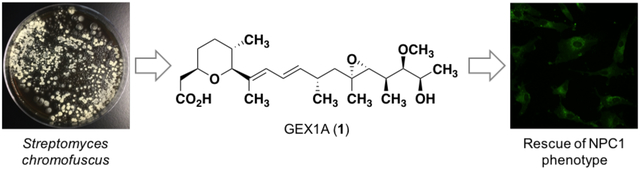

Graphical Abstract

Niemann-Pick type C disease (NPC) is a rare and fatal recessive genetic disorder that affects young children. Patients afflicted with NPC carry a mutation in either the NPC1 or NPC2 genes, with mutations in NPC1 accounting for about 95% of cases.1 Both gene products are involved in lysosomal cholesterol trafficking, and mutations result in the accumulation of unesterified cholesterol within the late endosomes and lysosomes of affected individuals.2 Despite the somber prognosis for NPC patients there is currently no FDA-approved treatment for this disease, although some strategies are currently being investigated in clinical and pre-clinical settings.3 One such approach takes advantage of the ability of small molecule histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) to restore normal cholesterol homeostasis in NPC1 mutant fibroblasts. Specific HDACi, including trichostatin A and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), appear to restore cholesterol trafficking through increased expression of the NPC1 protein, among other changes to gene expression.4

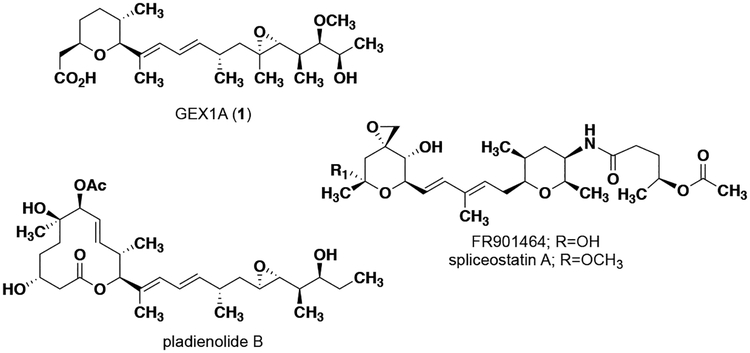

In 1997, Ohnuki and coworkers reported that the natural product GEX1A, also known as herboxidiene, (1, Figure 1) increased expression of the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor similar to the HDACi trichostatin A, but does not affect histone acetylation.5 GEX1A is a type I polyketide that was first isolated in 1992 from Streptomyces chromofuscus.6,7 In 2011, it was discovered that GEX1A can affect pre-mRNA splicing through binding to SAP155, a component of splicing factor 3B subunit 1 (SF3b1).8 The ability to modulate the pre-mRNA splicing (and therefore expression) of a number of important cell cycle regulators is believed to be responsible for the anti-proliferative activity of GEX1A,9 the related natural products pladienolide B10 and FR901464,11 and structural analogues of these compounds.12,13 GEX1A has been the focus of numerous synthetic efforts14–21 and biosynthetic studies22–24 as a result of its intriguing biological activity. Due to the biological similarities between 1 and trichostatin A in the context of cholesterol-related gene expression, we became interested in GEX1A as a potential therapeutic for NPC1 disease.

Figure 1.

Structures of small molecules that modulate splicing through targeting splicing factor 3B subunit 1.

Results and Discussion.

In order to access significant quantities of GEX1A for biological testing, we turned to fermentation of the producing organism, S. chromofuscus. We optimized production conditions to yield titers of 150 mg/L and purified GEX1A yields of ~50–70 mg/L. S. chromofuscus ATCC 49982 is cultivated on an agar-based medium (0.8% soy flour, 1.0% glucose, 0.4% yeast extract, 0.05% CaCO3), which is homogenized and filtered following the fermentation period. The organic material is then extracted via the introduction of Amberlite XAD-16 resin. Subsequent elution of the organic material in methanol followed by solvent evaporation affords crude 1 that can be purified effectively via flash column chromatography. Alternatively, crude GEX1A can be obtained by suspending the agar plates in ethyl acetate with stirring for a period of two days followed by filtration and evaporation of the organic solvent. This approach represents a marked improvement over the initial isolation titers6 and is a viable pathway towards accessing substantial amounts of GEX1A in an academic laboratory setting. We note that the addition of calcium to the fermentation medium was particularly effective for improvements in titers.

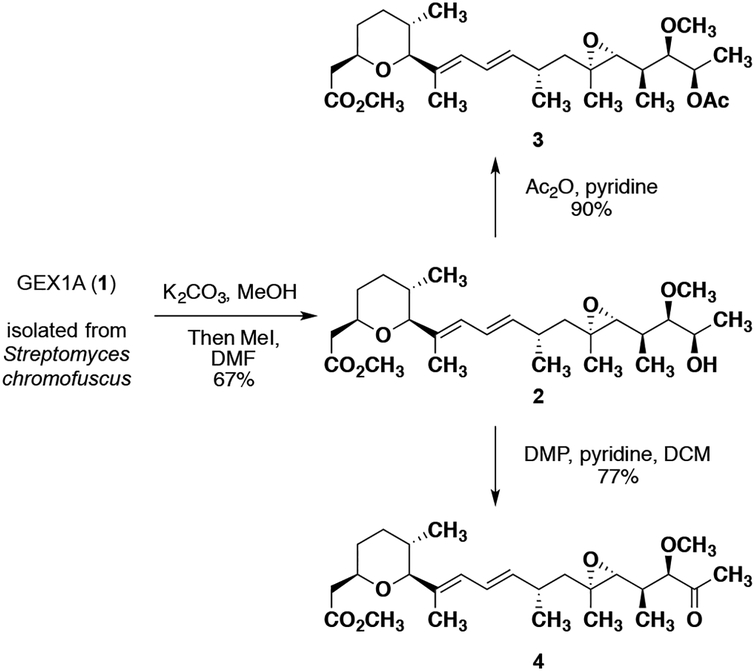

With natural product 1 in our possession, we began to target structural analogues that could be generated via chemical derivation of the parent compound. During our preliminary isolation effort, it was determined that in order to acquire GEX1A that was pure enough for biological testing multiple rounds of flash chromatography were required. To circumvent this issue, impure 1 was converted to the potassium salt through treatment with K2CO3 in MeOH and subsequently methyl iodide to furnish, upon purification, pure GEX1A methyl ester 2 in 67% yield (Scheme 1). Further manipulation of 2 led us to access two additional semi-synthetic analogues. Webb and co-workers have proposed that the C18 hydroxyl group is a vital H-bond donor for the anti-proliferative activity of GEX1A,25 and we were interested in determining if this functionality was also relevant for any potential activity in the context of NPC. Treatment of 2 with acetic anhydride and pyridine afforded the C18-OAc analogue 3 in 90% yield (Scheme 1). Due to concerns over the fact that 3 may be labile under biological assay conditions, we sought a more distinctive transformation to further determine the effect of the hydroxyl functionality. Webb and colleagues has previously demonstrated that converting the C18 alcohol to a ketone results in a significant loss in activity in cancer cell lines.25 Thus, exposing methyl ester 2 to Dess-Martin periodinane and pyridine gave rise to the C18-oxo compound 4 in 77% yield. With GEX1A 1 and analogues 2 – 4 in hand, we sought to assess their ability to restore cholesterol trafficking in NPC1 mutant fibroblasts.

Scheme 1.

Semi-synthetic access to GEX1A analogues.

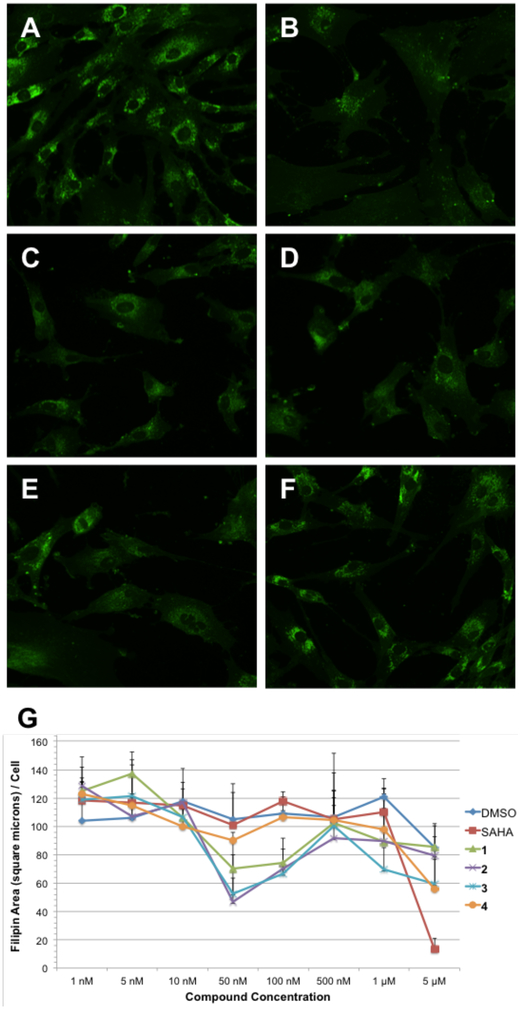

Our compounds were first evaluated in the GM18453 skin fibroblast cell line, from patients carrying the I1061T mutation on both alleles of NPC1. This mutation represents one of the most common genetic markers of NPC disease (found in 15–20% of patients).26,27 Cells were incubated for 48 hours with varying concentrations (1 nM to 5 μM) of 1 – 4. In parallel, cells were incubated with vehicle control DMSO or the HDACi SAHA (also known as Vorinostat) as a positive control. SAHA is effective in reversing cholesterol accumulation in several NPC1 mutant cell lines, including GM18453.4,28 Following incubation the cells were fixed and stained with filipin, a fluorescent polyene macrolide that specifically binds to unesterified cholesterol and allows for the visualization of localized cholesterol within the cells. Images of the filipin-stained cells were collected using an automated fluorescence microscope (Figure 2A–F), and image analysis was performed via quantification of filipin fluorescence area per cell as a measure of unesterified cholesterol (Figure 2G). As these representative images show, GEX1A and analogues correct the cholesterol accumulation phenotype at the indicated concentrations in GM18453 cells, as seen through a reduction in punctated filipin staining as compared to vehicle-treated cells.

Figure 2.

Comparison of GEX1A analogues in NPC1 mutant fibroblasts. GM18453 cells were incubated with each compound for 48 hours and subsequently fixed, stained with filipin (green false color), and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. A) DMSO; B) SAHA, 5 μM; C) GEX1A 1, 50 nM; D) GEX1A methyl ester 2, 50 nM; E) C18-OAc GEX1A methyl ester 3, 50 nM; F) C18-oxo GEX1A methyl ester 4, 50 nM. G) Dose dependence of cholesterol clearance activity. Filipin area sum and cell count were measured in fluorescence microscopy images following treatment with the indicated compound (or vehicle control) for 48 hours. Data shown are derived from four independent replicates, and four images were acquired for each condition in each experiment. Error bars represent standard deviation between images.

As demonstrated by our fluorescent images, fermentation product 1 and semi-synthetic analogues 2 and 3 are highly effective in GM18453 cells, demonstrating significant rescue of cholesterol accumulation at concentrations as low as 50 nM. Some cholesterol clearance can be observed upon treatment with 4 at 50 nM as compared to vehicle treatment, but to a lesser degree than treatment with 1 – 3. Notably, GEX1A is able to induce a cellular phenotype that appears very similar to that resulting from treatment with SAHA at 5 μM, but at a concentration that is several orders of magnitude lower. We observed detrimental effects on cell and nuclei shape upon treatment with GEX1A at 5 μM, suggestive of cellular toxicity at high concentrations. This may explain the increase in fluorescence observed at concentrations of 100 μM and above.

The dose dependence of treatment with GEX1A and analogues was quantified by calculating the filipin area per cell, indicative of unesterified cholesterol, for each experimental condition. Natural product 1 and analogues 2 and 3 are able to achieve the lowest filipin area/cell in GM18453 cells at 50 nM, an effect that correlates with the observed cellular phenotypes. Analogue 4 was unable to correct the cholesterol accumulation phenotype as strongly as 1 – 3, indicating that the native C18 hydroxyl, and its capacity to serve as an H-bond donor, is an important component of the GEX1A scaffold in the context of cholesterol trafficking.

Compounds 1 through 4 were further evaluated in the GM18407 fibroblast cell line, derived from patients carrying heterozygous mutations at the NPC1 locus (R404Q, M1142T). This cell line is known to have a more severe biochemical phenotype than the GM18453 line with respect to efficiency of cholesterol esterification (mean acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase catalyzed cholesterol esterification value of 52 pmol CE/mg protein/6 hr as compared to 533 pmol CE/mg protein/6 hr in GM18453 cells and 1855±1327 pmol CE/mg protein/6 hr in healthy cells).29 SAHA has been previously reported to have no effect on lysosomal cholesterol accumulation in these cells.4 Consistent with these previous reports, neither SAHA nor compounds 1 – 4 were able to effectively rescue the disease phenotype even at high concentrations in this cell line (Supplemental Figure 1). This result further highlights the similarities between GEX1A and a representative HDACi in the context of intracellular cholesterol homeostasis.

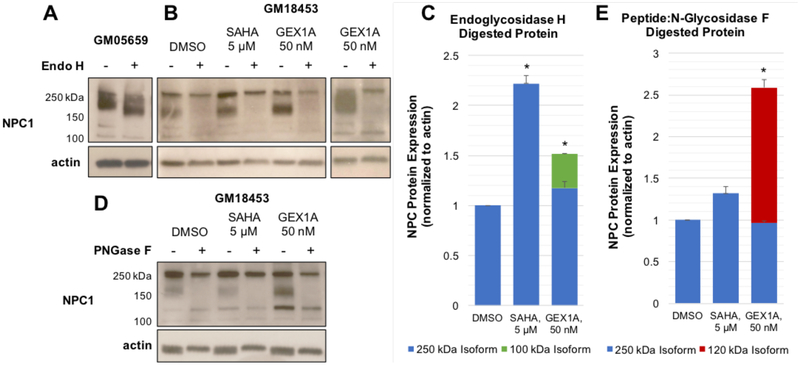

SAHA, like other HDACi, is thought to exert its beneficial effect on cholesterol trafficking through a global upregulation of gene expression, including upregulation of the mutant NPC1 protein. Specifically, SAHA has been shown to lead to an increase in an NPC1 protein isoform that is resistant to treatment with endoglycosidase H (Endo H), an enzyme that cleaves high mannose N-linked glycans from glycoproteins.30 During normal protein synthesis, newly translated proteins are decorated with N-linked glycans in the ER, and subsequently exported to the Golgi for further glycan elaboration. As these complex glycans cannot be cleaved by Endo H, resistance to Endo H indicates that a protein has undergone normal folding, stabilization, post-translational modification, and trafficking, and is available to carry out its designated cellular function. An increase in the levels of Endo H-resistant NPC1 available in the lysosomes of NPC1 mutant cells helps to explain the improved phenotype observed in SAHA-treated cells. To determine if a similar mechanism of action might contribute to the cellular phenotype induced by GEX1A, we measured NPC1 protein expression in NPC1 mutant fibroblasts following incubation with DMSO, SAHA, or GEX1A and subsequent Endo H treatment.

Cell lysates were prepared from GM18453 fibroblasts incubated with DMSO, SAHA (5 μM), or GEX1A (50 nM) for 48 hours, as well as from untreated human wild-type fibroblasts (GM05659). Lysates were treated overnight with endoglycosidase H, and total protein was subjected to Western blot analysis with an anti-NPC1 antibody (Figure 3). While the wild type NPC1 protein exhibited the expected increase in mobility upon treatment with Endo H (Figure 3A), the mutant NPC1 protein expressed in GM18453 cells presented a more heterogeneous electrophoretic pattern (Figure 3B). In DMSO-treated GM18453 cells, NPC1 appears as two major isoforms, which are immunodetected around 250 kDa and 180 kDa. Exposure to SAHA increases the expression of the larger (250 kDa) isoform relative to the vehicle control. Following deglycosylation of the DMSO- and SAHA-treated samples, NPC1 is detected around 250 kDa as a single, Endo H-resistant species. Treatment with GEX1A increases the expression of the 180 kDa species relative to levels in the DMSO-treated controls, and in some experiments also led to the appearance of a smaller NPC1 isoform, detected around 100 kDa. This 100 kDa species persists upon exposure to Endo H, while the 180 kDa protein is sensitive to Endo H and undergoes deglycosylation. Consistent with previous reports, we observed an approximately twofold increase in the levels of total NPC1 protein in fibroblasts treated with SAHA (Figure 3C). GEX1A did not cause a significant increase in the levels of the 250 kDa NPC1 isoform, however its overall impact on the expression of NPC1 protein was significant (an approximately 1.5-fold increase over controls) when the levels of the 100 kDa isoform was taken into account.

Figure 3.

Effect of GEX1A on NPC1 protein expression. A) Lysates derived from human wild-type (GM05659) fibroblasts were subjected to treatment with endoglycosidase H, and the expression of NPC1 was analyzed using SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with a rabbit anti-NPC1 antibody. B) Human NPC1 mutant (GM18453) fibroblasts were incubated with DMSO, SAHA (5 μM), or GEX1A (50 nM) for 48 hours. Cell lysates were treated with endoglycosidase H, and the expression of NPC1 was analyzed through immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-NPC1 antibody. C) NPC1 isoforms resulting from endoglycosidase H treatment were quantified using densitometry. Relative expression levels represent results from four independent experiments, and error bars represent standard deviation between experiments. * p < 0.05. D) Human NPC1 mutant (GM18453) fibroblasts were incubated with DMSO, SAHA (5 μM), or GEX1A (50 nM) for 48 hours. Cell lysates were treated with peptide:N-glycosidase F, and the expression of NPC1 was analyzed through immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-NPC1 antibody. E) NPC1 isoforms resulting from peptide:N-glycosidase F treatment were quantified using densitometry. Relative expression levels represent results from four independent experiments, and error bars represent standard deviation between experiments. * p < 0.05.

Total protein derived from DMSO, SAHA, or GEX1A-treated GM18453 fibroblasts was also subjected to deglycosylation with peptide:N-glycosidase F (PNGaseF) and subsequent Western blot analysis with an anti-NPC1 antibody (Figure 3D). PNGase F is active against a wider range of N-linked glycans than Endo H, and so digestion with this enzyme is likely to reveal distinct NPC1 glycoforms than Endo H treatment. We observed a moderate increase in the levels of the 250 kDa NPC1 isoform in our SAHA-treated samples relative to the DMSO control, which demonstrated resistance to PNGase F-catalyzed deglycosylation similar to our Endo H experiments. In the case of GEX1A treatment, we observed a clear increase in the expression of the highly glycosylated 180 kDa NPC1 isoform, which was sensitive to digestion with PNGase F. We also detected an approximately 120 kDa species that was reactive to our antibody and resistant to deglycosylation with PNGase F. Including both the 250 and 120 kDa isoforms, the level of NPC1 protein expression in GEX1A-treated fibroblasts showed a significant increase in comparison to DMSO-treated samples (Figure 3E). Overall our Western blotting and deglycosylation experiments show that GEX1A impacts both the level and variation of NPC1 protein available in mutant fibroblasts. While SAHA also increases the concentration of NPC1 protein in mutant cells compared to vehicle controls, GEX1A induces the expression of distinct isoforms of this crucial transport protein. This suggests that SAHA and GEX1A provoke a similar phenotypic effect in NPC1 models through distinct biochemical or cellular mechanisms.

The intriguing results from our biochemical studies led us to investigate the pharmacokinetic properties of GEX1A (Supplemental Figure 2). The compound has exceptional aqueous solubility, an excellent plasma protein binding profile, and is quite stable in liver microsomes. GEX1A is reasonably permeable as measured by a Caco-2 cell line with little differences observed in the presence of the efflux pump inhibitor verapamil. There is no evidence of efflux. These promising results, which hint at the potential ability of GEX1A to cross the blood-brain barrier in NPC patients, prompted further appraisal of the compound in mice. Plasma exposure for GEX1A was in agreement with in vitro properties in mice dosed at 2 mg/kg, and GEX1A displays a long half-life with an MRT of 4.53 hours. Altogether, GEX1A has a number of desirable PK properties (both in vitro and in vivo) that merit its advancement into animal models of NPC disease.

Overall our results show that GEX1A has a beneficial effect on intracellular cholesterol trafficking in NPC1 mutant cells through changes at the protein level. In the GM18453 cell line, misfolded NPC1 exists primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum and is targeted to the proteasome for degradation. Although the exact mechanism of action of SAHA and other HDACi in the context of NPC disease is unknown, the general process is thought to depend on the global upregulation of gene expression caused by these molecules. This includes an increase in the cellular concentration of chaperone proteins, which serve to facilitate the proper stabilization, folding, and trafficking of misfolded proteins like NPC1, as well as an increase in the concentration of the mutant NPC1 protein itself. Combined with an enrichment of other proteins involved in protein quality control and trafficking pathways, lipid metabolism, and cellular response to oxidative stress,30,31 SAHA induces a multifaceted biochemical response that leads to improvement of the NPC phenotype. Our results indicate that at least one pathway through which GEX1A restores intracellular cholesterol homeostasis is the increase of NPC1 expression. The increased appearance of Endo H- and PNGase F-resistant isoforms of NPC1 also suggests that GEX1A acts to improve the stability of the protein and promote its maturation and trafficking to the lysosomes, where it can play its dedicated role in cholesterol trafficking.

Although GEX1A is able to achieve similar phenotypes in NPC1 cells as the HDACi SAHA, our compound is known to have no effect on histone acetylation,32 and exerts its activity on gene expression through an alternate mechanism. GEX1A has been reported to target a component of the spliceosome, as well as trigger the alternative splicing of several genes (including CDKN1B, DNAJB1, BRD2, and RIOK3) in a dose-dependent manner.8 These genes are diverse in function, size, and chromosomal location, and their shared susceptibility to modulation by GEX1A hints at the broad ranging consequences to gene expression that GEX1A can induce. Interestingly, p27 (the product of CDKN1B) has been implicated in the regulation of the unfolded protein response,33,34 and DNAJB1 encodes the chaperone protein Hsp40.35 Upregulation of either protein may therefore significantly affect the concentration of mutant NPC1, and thus the efficiency of lysosomal cholesterol trafficking. Our results suggest that GEX1A may also have a direct effect on the splicing of NPC1 itself. While the exact identity and biological relevance of our observed, GEX1A-induced NPC1 isoforms is yet to be determined, the specificity of our anti-NPC1 antibody suggests they are associated with the C-terminal region of the NPC1 protein. This region of the protein is thought to be involved with the recruitment of downstream lipid transport proteins that would shuttle cholesterol to the ER or other cytoplasmic destinations following export from the lysosomes.36 RNA sequencing of GEX1A-treated fibroblasts is currently underway in our lab, and will provide insights into the precise role of GEX1A in ameliorating the NPC1 phenotype at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Recently, small molecules that modulate alternative splicing have shown potential as therapeutic candidates for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy, a debilitating genetic disorder.37,38 Along with our results, this work suggests that the strategy of small molecule-induced splicing modulation is quite promising in the context of genetic disease.

In summary, we have revealed the potential of the polyketide natural product GEX1A, and possibly related modulators of alternative splicing, to act as a novel therapeutic for NPC disease. We established a sustainable platform for accessing GEX1A through bacterial fermentation and demonstrated access to natural product derivatives through chemical semi-synthesis to yield structural analogues. We have illustrated the ability of GEX1A and its analogues to reverse the cholesterol accumulation phenotype associated with NPC at low nanomolar concentrations, comparably to a representative member of the well-studied HDACi class of compounds. We demonstrated that GEX1A increases the concentration of glycosidase-resistant NPC1 protein available in mutant fibroblasts and leads to the accumulation of distinct protein isoforms compared to HDACi treatment. Both the intriguing biochemical activity of GEX1A and its favorable pharmacokinetic properties support its further investigation as a potential therapeutic for NPC disease. Because of the emerging importance of splicing modulators for the treatment of genetic diseases, we are further developing a structure-activity relationship for the GEX1A scaffold in the context of NPC disease through the design and production of novel analogues. These analogues, as well as further work into the exact mechanism of action of this class of compounds, will be reported in due course.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Experimental Procedures.

Unless otherwise noted, all materials were used as received from a commercial supplier without further purification. All anhydrous reactions were performed using oven-dried or flame-dried glassware, cooled under vacuum and purged with argon gas. Dichloromethane (DCM), tetrahydrofuran (THF), toluene and diethyl ether (Et2O) were filtered through activated alumina under nitrogen. Triethylamine (TEA) was distilled over CaH2 and stored over KOH pellets. 4 Å molecular sieves were oven-dried overnight and cooled under high vacuum prior to use. All reactions were monitored by Silicycle thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates (Extra Hard Layer, 60 Å, glass back) and analyzed with 254 nm UV light and/or anisaldehyde treatment. Silica gel for column chromatography was purchased from Silicycle (SiliaFlash® P60, 230 – 400 mesh). Unless otherwise noted, all 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 using either a Varian Inova 500 spectrometer operating at 499.86 MHz for 1H and 125.69 MHz for 13C, or Varian VNMRS 600 operating 599.87 MHz for 1H and 150.84 MHz for 13C. Chemical shifts (δ) were reported in ppm relative to the residual CHCl3 as an internal reference (1H: 7.26ppm, 13C 77.23 ppm). Coupling constants (J) were reported in Hertz (Hz). Peak multiplicity is indicated as follows: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), p (pentet), x (septet), h (heptet), b (broad) and m (multiplet). Mass spectra (FAB) were obtained at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame using either a JEOL AX505HA or JEOL JMS-GCmate mass spectrometer.

S. chromofuscus seed cultures were grown in ISP1 or ISP2 liquid media (50 mL) for 48 hours at 28°C, 250 rpm. Agar production media plates were prepared and the seed culture was spread onto the plates (~0.5 mL/plate). The plates were cultured at room temperature in the dark for 14 days. After incubation, the plates were homogenized into 1 L dH2O. The crude aqueous extract was filtered via vacuum filtration through Whatman filter paper. Amberlite XAD-16 resin (2% w/v) was added to the filtered aqueous extract and left to stir for 24 hours. The extract was again filtered via vacuum filtration to obtain the Amberlite XAD-16 resin. The resin was suspended in methanol and left to stir for a period of 24 hours. The organic extract was then filtered via vacuum filtration and concentrated under reduced pressure. Alternatively, the production medium plates were homogenized into 1 L ethyl acetate and sonicated for 48 hours. The crude organic extract was filtered via vacuum filtration through Whatman filter paper and concentrated under reduced pressure. All crude organic material obtained through either of these methods was purified via flash column chromatography (2–10% MeOH:DCM) to yield the desired compound as a pale yellow oil. Isolated yields of GEX1A 1 were determined to be ~50–70 mg/L. [α]20D +6.4° (c 1.00, MeOH). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 6.30 (dd, J = 15.0, 10.9 Hz, 1H), 5.92 (d, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 5.48 (dd, J = 14.9, 9.1 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (q, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 3.81 – 3.72 (m, 1H), 3.52 (s, 3H), 3.35 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 2.98 (dd, J = 6.2, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 2.66 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 2.46 (dd, J = 15.3, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 2.47–2.42 (m, 1H), 2.39 (dd, J = 15.2, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 1.93 (dd, J = 13.5, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 1.89 – 1.82 (m, 1H), 1.69 (s, 3H), 1.58–1.46 (m, 2H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.39 – 1.15 (m, 2H), 1.11 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.05 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.83 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 0.69 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H).13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD) δ 175.2, 140.7, 136.1, 129.6, 126.5, 92.1, 88.5, 75.4, 69.9, 67.8, 62.6, 61.9, 48.1, 42.3, 36.5, 36.4, 33.4, 33.3, 32.7, 22.7, 19.8, 18.1, 16.7, 12.1, 11.5. HRMS–ESI (M+Na)+ = 461.2874 calculated for C25H42NaO6, experimental = 461.2852.

Semi-Synthesis of GEX1A Analogues 2 – 4.

Methyl 2-((2R,5S,6S)-6-((S,2E,4E)-7-((2R,3R)-3-((2R,3R,4R)-4-hydroxy-3-methoxypentan-2-yl)-2-methyloxiran-2-yl)-6-methylhepta-2,4-dien-2-yl)-5-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl) acetate (2): To a 10 mL round bottom flask charged with a stir bar GEX1A (1) (9.0 mg, 0.021 mmol) was dissolved in MeOH (1.0 mL) with stirring. To the solution was added K2CO3 (3.0 mg, 0.021 mmol) and the mixture was left to stir for ten minutes. At this time the pH of the mixture was checked and then concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude salt was then re-dissolved in DMF (2.0 mL) and an excess of methyl iodide was added. The mixture was allowed to stir overnight at room temperature. Upon completion, the reaction was diluted in water and extracted with EtOAc (5 × 5 mL). The combined organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford the crude methyl ester as a pale yellow oil. Flash column chromatography afforded (20%−50% EtOAc:Hexanes) afforded the GEX1A methyl ester 2 as a clear colorless oil (6.0 mg, 67%). [α]20D +3.6° (c 1.00, CHCl3). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.24 (dd, J = 15.0, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.90 (d, J = 10.9 Hz, 1H), 5.44 (dd, J = 15.1, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 3.89–3.83 (m, 1H), 3.81–3.75 (m, 1H), 3.67 (s, 3H), 3.54 (s, 3H), 3.33 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 2.97(t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (dd, J = 15.2, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.47–2.37 (m, 1H), 2.41 (dd, J = 15.2, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 1.91 (dd, J = 13.6, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 1.85 (ddd, J = 13.1, 6.9, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 1.76–1.66 (m, 1H), 1.71 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 3H), 1.57–1.49 (m, 2H), 1.39 – 1.19 (m, 3H), 1.29 (s, 3H), 1.19 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H), 1.05 (d, J = 6.70 Hz, 3H), 0.88 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 0.67 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.8, 139.2, 135.2, 128.1, 125.2, 90.6, 87.6, 73.8, 68.2, 66.0, 61.3, 61.3, 51.5, 46.9, 41.3, 35.3, 35.1, 32.2, 32.0, 31.6, 22.0, 19.0, 17.6, 16.5, 11.9, 11.8. HRMS–ESI (M+Na)+ = 475.3030 calculated for C26H44NaO6, experimental = 475.3034.

Methyl 2-((2R,5S,6S)-6-((S,2E,4E)-7-((2R,3R)-3-((2R,3R,4R)-4-acetoxy-3-methoxypentan-2-yl)-2-methyloxiran-2-yl)-6-methylhepta-2,4-dien-2-yl)-5-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl) acetate (3): To a reaction vial charged with a stir bar was added methyl ester 2 (70.1 mg, 0.155 mmol) and the vial was cooled to 0°C. This was followed by the successive addition of 1.5 mL of acetic anhydride and 1.5 mL of pyridine before allowing the resultant mixture to warm to room temperature and stir for 12 hours. The reaction was then poured over water and diluted with DCM. The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted a further with DCM (5 × 5 mL). The combined organic layers were then washed with brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The product was isolated as a pale brown oil (68.0 mg, 0.140 mmol, 90%). Biological testing samples could be obtained after subsequent purification via FC (20–40% Et2O:Hexanes) to furnish the desired compound 3 as a clear colorless oil. [α]20D +12.3° (c 1.00, CHCl3). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.22 (dd, J = 15.0, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.89 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.44 (dd, J = 15.0, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (dq, J = 6.0, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 3.80 – 3.74 (m, 1H), 3.67 (s, 3H), 3.53 (s, 3H), 3.32 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (dd, J = 6.8, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (dd, J = 15.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 2.40 (dd, J = 15.2, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 2.43 – 2.35 (m, 1H), 2.06 (s, 3H), 1.92 (dd, J = 13.5, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 1.84 (ddd, J = 13.1, 6.8, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 1.70 (s, 3H), 1.69 – 1.67 (m, 1H), 1.57 – 1.48 (m, 1H), 1.48 – 1.41 (m, 1H), 1.38 – 1.28 (m, 1H), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.25 – 1.15 (m, 2H), 1.18 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H), 1.04 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.84 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 0.66 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.0, 170.8, 139.5, 135.4, 128.4, 125.4, 90.8, 84.6, 74.0, 72.7, 66.1, 61.7, 60.9, 51.8, 47.1, 41.5, 35.5, 35.3, 32.4, 32.3, 31.8, 22.3, 21.6, 17.8, 17.0, 16.8, 12.06, 10.8. HRMS-ESI: (M+Na)+ = 517.3136 calculated for C28H46NaO7, experimental = 517.3163.

Methyl 2-((2R,5S,6S)-6-((S,2E,4E)-7-((2R,3R)-3-((2S,3R)-3-methoxy-4-oxopentan-2-yl)-2-methyloxiran-2-yl)-6-methylhepta-2,4-dien-2-yl)-5-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)acetate (4): To a flame dried 10 mL round bottom flask charged with a stir bar was added methyl ester 2 (30.1 mg, 0.0665 mmol) dissolved in DCM (1.0 mL). The solution was cooled to 0°C and anhydrous pyridine (54.0 μL, 0.665 mmol) was added, followed by the portion-wise addition of Dess-Martin periodinane (56.0 mg, 0.132 mmol). The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 30 minutes, at which point the reaction was quenched with a 1:1 mixture of saturated aq. NaHCO3 and saturated aq. Na2S2O3 (1.0 mL). The mixture was diluted with H2O and EtOAc and the layers were separated. The aqueous layer was extracted further with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL) and the combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the crude material as a light brown oil. Purification via FC (10 – 30% EtOAc:Hexanes) afforded the desired ketone 4 as a clear colorless oil (23.0 mg, 0.0510 mmol, 77% yield). [α]20D +25.0° (c 1.00, CHCl3). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.21 (dd, J = 15.0, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.42 (dd, J = 15.0, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (dtd, J = 11.1, 6.6, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 3.41 (s, 3H), 3.31 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 2.6 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 2.59 (dd, J = 15.2, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.43 – 2.35 (m, 1H), 2.39 (dd, J = 15.2, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 2.15 (s, 3H), 1.90 (dd, J = 13.6, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 1.83 (ddd, J = 13.2, 6.8, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 1.69 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H), 1.74 – 1.65 (m, 2H), 1.55 – 1.47 (m, 1H), 1.37 – 1.15 (m, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H) 1.03 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.81 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.64 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 211.0, 172.0, 139.4, 135.4, 128.3, 125.4, 90.8, 88.8, 74.0, 65.2, 61.2, 59.3, 51.8, 46.9, 41.5, 36.8, 35.5, 32.4, 32.3, 31.8, 26.8, 22.3, 17.8, 16.7, 12.1, 11.4. HRMS-ESI: (M+Na)+ = 473.2874 calculated for C26H42NaO6, experimental = 473.2882.

Western Blotting.

GM18453 fibroblasts were maintained in culture and seeded into 15 cm tissue culture dishes (~200,000 cells/dish). The following day cells were treated with GEX1A (50 nM), SAHA (5 μM), or DMSO (0.1% v/v), and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were subsequently harvested and lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with 2.8 μg/mL aprotinin, 100 μM leupeptin, 25 μg/mL ALLN, 5 μg/mL pepstatin A, 0.5 mM AEBSF, and 1 mM DTT. Insoluble cell debris was pelleted (14,000 rpm, 20 minutes), and the total protein contained in the resulting supernatant was quantified using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). Total protein (25–50 μg/sample) was heated at 65°C for seven minutes, separated by SDS-PAGE (4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX gels, Bio-Rad), and transferred to PVDF membrane using the Mini-Trans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were blocked for 2 hours at room temperature with 5% dry milk in PBS and treated with primary antibody (anti-NPC1: rabbit polyclonal, corresponding to the C-terminal region of the protein, Abcam #36983; 1:1000 in 2% dry milk in PBS-T (0.05% Tween20) overnight at 4°C. Anti-actin: rabbit polyclonal, Cytoskeleton, Inc. #AAN01, 1:1000 in 2% dry milk in PBS-T for 1 hour at room temperature.). Membranes were washed with PBS-T and incubated with horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit polyclonal, Jackson Immunoresearch #111-035-144), 1:10,000 in 2% dry milk in PBS-T, for two hours at room temperature. Membranes were visualized using the Pierce ECL System (Thermo Scientific) and autoradiography film.

Protein Deglycosylation.

For Endo H digestion, whole cell lysates (25 μg) were incubated with 10X Denaturing Buffer (1 μL, Promega) at 65°C for ten minutes. The reaction was subsequently treated with 10 Endo H Reaction Buffer (2 μL, Promega), ddH2O (6 μL), and Endo H (1000 U, 2 μL, Promega), and incubated overnight (~18 hours) at 37°C. The Endo H reaction mixture was cooled at 4°C for 30 minutes prior to electrophoresis. For PNGase F digestion, whole cell lysates (25 μg) were treated with 5% SDS (1 μL), 1 M DTT (1 μL), 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8 (2 μL), and PNGase F (1000 U, 2 μL, Promega), and incubated overnight (~18 hours) at 37°C. Deglycosylated protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and immunodetected as described above. Densitometry of the bands resulting from Endo H and PNGase F treatment was performed in ImageJ. Images of scanned film were converted to 32-bit images and rectangular lanes were selected using the gel analysis tool. Each band associated with deglycosylated protein was normalized to that lane’s corresponding actin band. Relative levels of NPC1 protein resulting from GEX1A and SAHA treatment were compared to the corresponding DMSO treatment. Statistical significance was determined using the student’s t-test.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Vipat Raksakulthai, field application scientist at Molecular Devices, who greatly assisted with the development of a MetaXpress analysis tool for the quantification of filipin stain per cell. This work was supported in part by the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation. EAG acknowledges support from the Chemistry-Biochemistry-Biology Interface (CBBI) Program at the University of Notre Dame, training grant T32GM075762, from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

The supporting material (including experimental, supplementary figures and spectral characterization for 1 – 4) is available free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Vanier MT J. Inherit. Metab. Dis 2015, 38, 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kwon HJ; Abi-Mosleh L; Wang ML; Deisenhofer J; Goldstein JL; Brown MS; Infante RE Cell 2009, 137, 1213–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).a. Lyseng-Williamson KA Drugs 2014, 4, 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b. Nagral A Gaucher disease. Clin. Exp, Hepatol 2014, 4, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c. Kirkegaard T; Gray J; Priestman DA; Wallom KL; Atkins J; Olsen OD; Klein A; Drndarski S; Petersen NH; Ingemann L; Smith DA; Morris L; Bornæs C; Jørgensen SH; Williams I; Hinsby A; Arenz C; Begley D; Jäättelä M; Platt FM Sci. Transl. Med 2016, 8, 355ra118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d. Ory DS; Ottinger EA; Farhat NY; King KA; Jiang X; Weissfeld L; Berry-Kravis E; Davidson CD; Bianconi S; Keener LA; Rao R; Soldatos A; Sidhu R; Walters KA; Xu X; Thurm A; Solomon B; Pavan WJ; Machielse BN; Kao M; Silber SA; McKew JC; Brewer CC; Vite CH; Walkley SU; Austin CP; Porter FD Lancet 2017, 390, 1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).a. Pipalia NH; Cosner CC; Huang A; Chatterjee A; Bourbon P; Farley N; Helquist P; Wiest O; Maxfield FR Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2011, 108, 5620–5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b. Pipalia NH; Subramanian K; Mao S; Ralph H; Hutt DM; Scott SM; Balch WE; Maxfield FR J. Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 695–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Assay RJ Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1997, 50, 970–971. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Miller-Wideman M; Makkar N; Tran M; Isaac B; Biest N; Stonard R J. Antibiotics 1992, 45, 914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Isaac BG; Ayer SW; Elliott RC; Stonard RJ J. Org. Chem 1992, 57, 7220–7226. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hasegawa M; Miura T; Kuzuya K; Inoue A; Ki SW; Horinouchi S; Yoshida T; Kunoh T; Koseki K; Mino K; et al. ACS Chem. Biol 2011, 6, 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sakai Y; Yoshida T; Ochiai K; Uosaki Y; Saitoh Y; Tanaka F; Akiyama T; Akinaga S; Mizukami TJ Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2002, 55, 855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kotake Y; Sagane K; Owa T; Mimori-Kiyosue Y; Shimizu H; Uesugi M; Ishihama Y; Iwata M; Mizui Y Nat. Chem. Biol 2007, 3, 570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kaida D; Motoyoshi H; Tashiro E; Nojima T; Hagiwara M; Ishigami K; Watanabe H; Kitahara T; Yoshida T; Nakajima H; et al. Nat. Chem. Biol 2007, 3, 576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Fan L; Lagisetti C; Edwards CC; Webb TR; Potter PM ACS Chem. Biol 2011, 6, 582–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Pham D; Koide K Nat. Prod. Rep 2016, 33, 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Banwell M; McLeod M; Premraj R; Simpson G Pure Appl. Chem 2000, 72, 1631–1634. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yun Z; Panek JS Org. Lett 2007, 9, 3141–3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Murray TJ; Forsyth CJ Org. Lett 2008, 10, 3429–3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ghosh AK; Li J Org. Lett 2011, 13, 66–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Pellicena M; Krämer K; Romea P; Urpí F Org. Lett 2011, 13, 5350–5353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Meng F; McGrath KP; Hoveyda AH Nature 2014, 513, 367–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Yadav JS; Reddy GM; Anjum SR; Reddy BVS Eur. J. Org. Chem 2014, 2014, 4389–4397. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Rohrs TM; Qin Q; Floreancig PE Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 10900–10904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Shao L; Zi J; Zeng J; Zhan J Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2012, 78, 2034–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Yu D; Xu F; Zhang S; Shao L; Wang S; Zhan J Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2013, 23, 5667–5670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yu D; Xu F; Shao L; Zhan J Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2014, 24, 4511–4514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lagisetti C; Yermolina MV; Sharma LK; Palacios G; Webb TR ACS Chem. Biol 2014, 1–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (26).Millat G; Marais C; Rafi MA; Yamamoto T; Morris JA; Pentchev PG; Ohno K; Wenger DA; Vanier MT Am. J. Hum. Genet 1999, 65, 1321–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gelsthorpe ME; Baumann N; Millard E; Gale SE; Langmade SJ; Schaffer JE; Ory DS J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 8229–8236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wehrmann ZT; Hulett TW; Huegel KL; Vaughan KT; Wiest O; Helquist P; Goodson H PloS One 2012, 7, e48561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Park WD; O’Brien JF; Lundquist PA; Kraft DL; Vockley CW; Karnes PS; Patterson MC; Snow K Hum. Mutat 2003, 22, 313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Subramanian K; Rauniyar N; Lavalleé-Adam M; Yates JR; Balch WE Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP 2017, mcp.M116.064949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Rauniyar N; Subramanian K; Lavallée-Adam M; Martínez-Bartolomé S; Balch WE; Yates JR Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP 2015, 14, 1734–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Yoshida T; Sakai Y; Tsujita T; Akiyama T; Yoshida T; Mizukami T; Akinaga S; Horinouchi S; Yoshida MJ Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2002, 55, 863–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Han C; Jin L; Mei Y; Wu M Cell. Signal 2013, 25, 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Liu J; Zhang D; Mi X; Xia Q; Yu Y; Zuo Z; Guo W; Zhao X; Cao J; Yang Q; et al. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 26058–26065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Ohtsuka K Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1993, 197, 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Soccio RE; Breslow JL J. Biol. Chem 2003, 278, 22183–22186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Naryshkin NA; Weetall M; Dakka A; Narasimhan J; Zhao X; Feng Z; Ling KKY; Karp GM; Qi H; Woll MG; et al. Science 2014, 345 (6197), 688–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Palacino J; Swalley SE; Song C; Cheung AK; Shu L; Zhang X; Van Hoosear M; Shin Y; Chin DN; Keller CG; et al. Nat. Chem. Biol 2015, 11, 511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.