Abstract

Introduction

Care escalation for patients at risk of deterioration requires that care team members are able to effectively communicate patient care concerns to more senior team members. However, multiple factors inhibit residents from escalating their concerns, which contributes to treatment delays and sentinel events.

Methods

We developed and implemented an annual 1- and 2-hour escalation curriculum for senior pediatric residents from the University of Colorado. The curriculum consisted of case presentations (one for the 1-hour or two for the 2-hour session), lecture, large-group discussion, and small-group activities. Faculty and fellows facilitated small groups, in which barriers to care escalation and specific tools for effective escalation were discussed. We administered precurriculum surveys for resident self-reflection and postcurriculum surveys for curriculum evaluation.

Results

The curriculum was delivered to 179 residents over 3 years (2016–2018). Surveys were administered during the first 2 years, and 87% of participants completed pre- and postcurriculum surveys. Of all respondents, 88% believed that the curriculum helped them recognize care escalation barriers, and 85% believed that they learned skills for effective escalation. Resident comfort in asking for attending physician help improved from 52% to 95% (p < .001). Analysis of postsurvey open-ended responses indicated that residents valued listening to faculty share their personal experiences of escalating care.

Discussion

The development and implementation of a curriculum to improve resident comfort and perceived ability to escalate patient care concerns are feasible and effective. Further work is needed to evaluate the impact of this curriculum in the clinical setting.

Keywords: Escalation, Residency Education, Patient Safety, Program Evaluation, Communication Skills

Educational Objectives

By the end of this activity, residents will be able to:

-

1.

Describe the importance of care escalation.

-

2.

Recognize barriers to care escalation.

-

3.

Examine comfort with escalating patient care concerns.

-

4.

Employ skills for effective care escalation.

Introduction

Rationale

In academic health centers, residents, who are still in training, are frequently the frontline providers responsible for the care of hospitalized patients. Once residents recognize a sick or deteriorating patient, a skill that is learned throughout training, they are then expected to communicate their concerns to senior team members such as fellows or attending physicians as part of a process known as care escalation. Failure to escalate patient concerns can result in treatment delays and contribute to patient harm and/or sentinel events.1–4 However, several interpersonal and organizational factors can affect one's ability to escalate concerns, including established hierarchies, fear of criticism, desire for autonomy, overconfidence, and fear of waking up attending physicians during overnight shifts.3,5–9 Care escalation is more of an art than a science; one's ability to escalate concerns requires not only medical knowledge but also timely and effective communication up and down the hierarchical chain of medicine. However, residents often receive no formal training on care escalation, and interventions are required to improve this critical safety process.5

Target Audience and Curricular Goal

Our goal was to develop and implement a new curriculum for senior (PGY 2 and PGY 3) residents to improve resident recognition of barriers to care escalation, comfort escalating concerns, and perceived ability to escalate. We elected to focus on senior residents because they have the unique position of escalating concerns to more senior providers on the team (e.g., fellows or attendings) but are also escalated to by interns, nurses, and other care providers.

Contribution to Existing Literature

This submission provides a unique contribution to existing literature because the creation of an escalation curriculum for residents and its impact have not been described. A MedEdPORTAL “learning from errors” curriculum has been published that uses morbidity and mortality cases to teach residents how to perform root cause analyses and identify sources of error, including failure to escalate care; however, teaching how or when to escalate concerns is not a major focus.10 Given the importance of care escalation in patient safety, the complexity of physical, cognitive and social barriers in escalation, and the lack of training provided to residents, this novel curriculum is critical for resident learners.

Methods

Curriculum Development

Based on best practices for curriculum development, we used Kern's six steps of curriculum development for medical education to develop the escalation curriculum.11 For step 1 (problem identification), there was no curriculum to teach residents to escalate concerns despite the knowledge that failure to effectively escalate contributes to adverse patient outcomes. For step 2 (targeted needs assessment), several root cause analyses at our institution identified lack of care escalation as a contributing factor to serious adverse patient safety events. After problem identification and targeted needs assessment, we subsequently followed the remaining steps in Kern's model to develop our escalation curriculum.

Conceptual Framework

In planning the development of our curriculum, we chose reflective practice from cognitive psychology as our conceptual framework.12 In reflective practice, learners reflect on an experience that has already occurred, think about what could be done differently, and use new perspectives to process feelings and actions.13 To facilitate reflection in our curriculum, we incorporated storytelling, in which teachers and learners shared personal experiences involving care escalation and reflected on those experiences. Storytelling promotes reflection and maximizes learning from experience.14

Educational Strategies

The content of this curriculum was created from in-depth review of existing literature and interdisciplinary discussion with attending physicians, fellows, residents, and nurses. It included principles of care escalation, importance of care escalation, and practical methods of care escalation. We utilized multiple educational methods to meet different learning styles, maintain learner interest, and reinforce learning. These educational methods included case presentation to share personal experiences, large-group lecture and discussion, small-group discussion, and small-group report-out to the larger group.

Curriculum Context

Our escalation curriculum was implemented at the University of Colorado pediatric residency program (approximately 30 residents per class). The residency program was associated with the University of Colorado School of Medicine and Children's Hospital Colorado, a 444-bed academic children's hospital. We designed our escalation curriculum to be delivered as either a 1- or 2-hour educational workshop for rising PGY 2s and PGY 3s. Our curriculum was incorporated into the rising senior resident (PGY 2 and PGY 3) half-day orientation early in the academic year (June-August), before the residents began supervisory rotations on high-acuity inpatient services. Initially designed as a 2-hour workshop, we modified our curriculum to be delivered in a 1-hour format for the 2018–2019 academic year due to decreased time available during the resident orientation. Approximate time lines for the two escalation curricula are included (Appendix A). One session was delivered to rising PGY 2s, and a repeat session was delivered to PGY 3s. Residents were free from clinical responsibilities during this workshop, as patient care coverage was provided by resident peer cross-coverage. There was no prerequisite knowledge required of the learners.

The curriculum took place in a hospital conference room that was large enough to accommodate approximately 30 residents and used small round tables to cluster residents into four to six smaller groups. The conference room had tables, chairs, and a projector. Each table had an easel pad and marker to write down themes resulting from small-group discussion.

The small-group facilitators included a mixture of fellow and attending physicians of various levels of experience who were selectively identified by the chief residents for their commitment to resident education. A faculty member who helped create the curriculum extended an invitation for participation in this teaching opportunity. We planned to recruit teachers from varying specialties to include at least one hospitalist, one subspecialist, one intensive care unit provider, and one emergency physician to cover the spectrum of high-acuity settings in which residents work. We emailed small-group facilitators ahead of time and provided them with an overview of the curriculum. There was no other prerequisite knowledge or preparation required of the facilitators. There were no costs associated with this curriculum. Support was obtained from the hospital administration and residency program directors. The chief residents were responsible for scheduling these sessions, and faculty members recruited the small-group facilitators.

Curriculum Implementation

Curriculum overview

One or two presenters led the discussion. The presenter(s) varied depending on availability but over the 3 years included a chief resident and/or a fellow or faculty member who was involved in the development of the curriculum. A PowerPoint presentation helped guide the presenter through the curriculum (Appendix B). The curriculum started with an overview of the educational objectives and content. Volunteers then shared personal experiences with cases of care escalation. After introducing and personalizing the topic, the presenter then led a large-group lecture and discussion about what care escalation is, why concerns should be escalated, and how to escalate. Small-group discussions with report-out to the large group were incorporated throughout the presentation.

Sharing of personal experiences with a case of care escalation

We started the workshop with a presentation to the large group of one or two real cases (depending on time allotted) that occurred within the past year—typically shared by willing residents, fellows, or attendings—that highlighted either a success or failure of care escalation. Potential volunteers willing to share these stories were identified and invited to participate by the chief residents. The objective of the presentation was to personalize care escalation and lessons learned. In some cases, the speakers were the ones who escalated patient care concerns; in others, they were the ones who were escalated to by other providers. One case was presented in the 1-hour session and two cases in the 2-hour session. If we did not have personal cases from residents, we used a preprepared recounting of a real case that occurred during the year that was shared by the session presenter using PowerPoint slides. An example of a case is provided in slide 7 of Appendix B. The cases were then followed by small-group discussion with questions tailored toward one of the cases that was presented.

Large-group lecture and discussion

The large-group interactive presentation discussed the definition of care escalation, why it is important, when to escalate concerns, how to escalate concerns, barriers to care escalation, and tools for effective care escalation.

Small-group discussions

Small-group activities were incorporated throughout the large-group presentation. There were approximately four to six small groups each composed of five to 10 residents and one to two facilitators. Residents and facilitators sat around small circular tables to listen to the large-group lecture, which allowed for easy transition to small-group discussions at the table. Topics included case-specific questions on care escalation, personal and institutional barriers to care escalation, and specific tools and skills to help overcome these barriers. These discussions allowed for intimate question-and-answer sessions and sharing of personal experiences. No handouts were required. The small-group discussions were informal and loosely structured based on prompting questions on the PowerPoint slides, but they were often guided by the questions and stories from the residents.

Small-group report-out

After small-group discussions, a volunteer from each group shared a discussion point and a take-home lesson about care escalation with the larger group to ensure that residents learned from everyone, not just the people at their table.

One- versus 2-hour curriculum

The curriculum was delivered over 1 or 2 hours depending on time availability. In both cases, we covered the same topics, generally used the same PowerPoint slides, and had the same number of residents and small-group facilitators. The difference was the time allocated for each part (Appendix A). In the 1-hour session, we condensed the curriculum by discussing one case instead of two and decreased the time for small-group discussions.

PGY 2 versus PGY 3 curriculum

The overall curriculum was the same for PGY 2s and PGY 3s. The one difference in the PowerPoint slides was an introductory slide (slide 4 for PGY 2s and slide 5 for PGY 3s, Appendix B). The small-group discussions were based on questions and concerns of the residents, which often varied by year. Furthermore, the small groups discussed care escalation as it related to the specific clinical roles and scenarios relevant to residents’ service requirements in the upcoming year, which differed between the two classes.

Evaluation Strategy

The escalation curriculum was evaluated through surveys. We obtained institutional approval as a program evaluation through the Organizational Research Risk and Quality Improvement Review Panel at Children's Hospital Colorado. We administered pre- and postcurriculum paper surveys at the beginning and end of each session (Appendices C and D) to maximize response rates for the 2016 and 2017 academic years. We did not survey residents following the session during the 2018 academic year, as this workshop was modified to be delivered over 1 hour.

Survey Development

Attending physicians and residents involved in the curriculum development created the survey questions, which were subsequently reviewed and edited by the department's survey methodologist. Surveys consisted of multiple-choice questions with primarily ordinal scales, as well as item-specific scales and free-response questions. The objectives of the pre- and postcurriculum surveys differed. The precurriculum survey was primarily designed to promote self-reflection about perceived effectiveness at care escalation, barriers to care escalation, and comfort with care escalation in preparation for small-group activities. The aim of the postcurriculum survey was to assess the impact of the curriculum on resident comfort escalating concerns, recognition of barriers, and perceived care escalation abilities. In Kirkpatrick's four-level model of evaluation, the postcurriculum survey evaluated learners’ reactions.15 The pre- and postcurriculum surveys had only one question in common. We purposefully included the same case vignette about resident comfort escalating patient care concerns to the attending physician in both the pre- and postcurriculum surveys.

Data Analysis Plan

To assess the impact of the curriculum, we first analyzed the results from the postcurriculum survey. We then compared resident responses to the case vignette presented in both the pre- and postcurriculum surveys. Only surveys completed by the same resident before and after the curriculum were included. When evaluating the postcurriculum survey, analysis was first completed for all respondents using Fisher exact tests. We then performed two secondary analyses: (1) comparing the responses of PGY 2s and PGY 3s in the inaugural year using Fisher exact tests, and (2) comparing responses of first-time curriculum takers as a PGY 2 to those who repeated the curriculum the following year as a PGY 3 with matched responses using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Precurriculum versus postcurriculum matched survey responses to the case vignette question were compared to a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Responses of quite a bit/a lot and pretty comfortable/very comfortable were combined into single affirmative responses for purposes of data analysis. Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for statistical analysis. Responses to open-ended questions on the curriculum's impact were analyzed for major themes.

Results

Results of Implementation and Characteristics of Learners/Facilitators

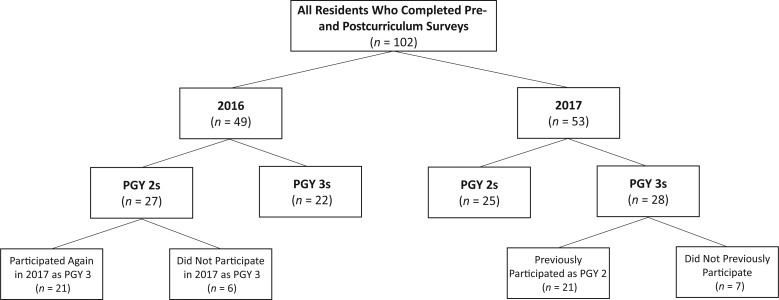

Over a 3-year period (2016–2018), a total of 179 rising pediatric senior residents participated in the curriculum, which was given twice per year (once for PGY 2s and once for PGY 3s). Surveys were administered after the 2016 and 2017 sessions, and 102 (52 PGY 2s and 50 PGY 3s) of 117 residents completed both the pre- and postcurriculum surveys (87% response rate; Figure 1). Of those who received the curriculum as a PGY 2 (N = 27), 21 attended the escalation curriculum as a rising PGY 3 (Figure 1). There were six to 10 facilitators (fellows/attending physicians) in each session from hospital medicine, subspecialty care, intensive care, and emergency medicine.

Figure 1. Schematic of survey respondents by year, class, and prior experience with the curriculum.

Impact of the Escalation Curriculum

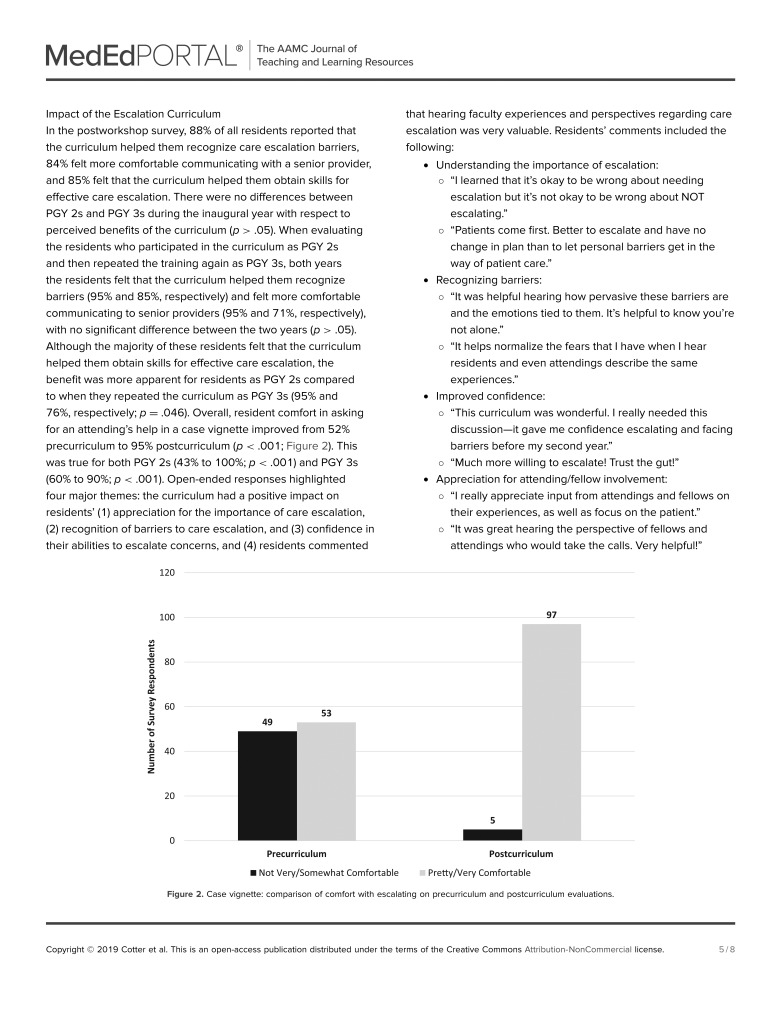

In the postworkshop survey, 88% of all residents reported that the curriculum helped them recognize care escalation barriers, 84% felt more comfortable communicating with a senior provider, and 85% felt that the curriculum helped them obtain skills for effective care escalation. There were no differences between PGY 2s and PGY 3s during the inaugural year with respect to perceived benefits of the curriculum (p > .05). When evaluating the residents who participated in the curriculum as PGY 2s and then repeated the training again as PGY 3s, both years the residents felt that the curriculum helped them recognize barriers (95% and 85%, respectively) and felt more comfortable communicating to senior providers (95% and 71%, respectively), with no significant difference between the two years (p > .05). Although the majority of these residents felt that the curriculum helped them obtain skills for effective care escalation, the benefit was more apparent for residents as PGY 2s compared to when they repeated the curriculum as PGY 3s (95% and 76%, respectively; p = .046). Overall, resident comfort in asking for an attending's help in a case vignette improved from 52% precurriculum to 95% postcurriculum (p < .001; Figure 2). This was true for both PGY 2s (43% to 100%; p < .001) and PGY 3s (60% to 90%; p < .001). Open-ended responses highlighted four major themes: the curriculum had a positive impact on residents’ (1) appreciation for the importance of care escalation, (2) recognition of barriers to care escalation, and (3) confidence in their abilities to escalate concerns, and (4) residents commented that hearing faculty experiences and perspectives regarding care escalation was very valuable. Residents’ comments included the following:

-

•Understanding the importance of escalation:

-

○“I learned that it's okay to be wrong about needing escalation but it's not okay to be wrong about NOT escalating.”

-

○“Patients come first. Better to escalate and have no change in plan than to let personal barriers get in the way of patient care.”

-

○

-

•Recognizing barriers:

-

○“It was helpful hearing how pervasive these barriers are and the emotions tied to them. It's helpful to know you're not alone.”

-

○“It helps normalize the fears that I have when I hear residents and even attendings describe the same experiences.”

-

○

-

•Improved confidence:

-

○“This curriculum was wonderful. I really needed this discussion—it gave me confidence escalating and facing barriers before my second year.”

-

○“Much more willing to escalate! Trust the gut!”

-

○

-

•Appreciation for attending/fellow involvement:

-

○“I really appreciate input from attendings and fellows on their experiences, as well as focus on the patient.”

-

○“It was great hearing the perspective of fellows and attendings who would take the calls. Very helpful!”

-

○

Figure 2. Case vignette: comparison of comfort with escalating on precurriculum and postcurriculum evaluations.

Discussion

Value of an Escalation Curriculum

We created an escalation curriculum after identifying failure to escalate care as a contributing factor to serious adverse patient safety events. To fill a gap in resident education, we created a structured venue to discuss the importance of care escalation, challenges in care escalation, and tools to help overcome these barriers. Our results show that this innovative escalation curriculum improved residents’ comfort and perceived ability to effectively escalate care. The open-ended comments also suggest that the curriculum helped residents appreciate the importance of care escalation, recognize the barriers to care escalation, and feel more comfortable escalating concerns, which were the objectives of this curriculum.

Reflection on Development, Implementation, and Evaluation

Finding educational time at a large and busy academic health center was a significant challenge. It was ideal to incorporate our curriculum into an already scheduled half-day orientation for rising senior residents who were free from clinical duties; however, due to changes in the orientation itinerary, we had to modify our escalation curriculum to be delivered over 1 hour instead of 2 hours for the 2018–2019 academic year.

One of the biggest keys to our success was starting off with a case example, because it helped highlight the importance of the topic and personalize our discussion. We found that it was easy to find volunteers willing to share their cases, but we recognize that this may not be the case everywhere. In that case, we recommend using a sample case such as the one on slide 7 in Appendix B.

Another key to our success was incorporating small-group facilitators including fellows and attendings. This was a common theme that many residents discussed when writing open-ended comments after the curriculum. The facilitators helped stimulate discussions, offered suggestions based on personal experience, and normalized the feelings that many residents experience with regard to care escalation. Because fellows and attendings are often the ones being escalated to, hearing them reiterate the importance of care escalation likely helped residents feel more confident and comfortable with escalating concerns. Although we found that faculty and fellows were very responsive and willing to participate, recruiting adequate numbers of small-group facilitators may be challenging at other hospitals depending on the size and availability of staff. Providing the facilitators with objectives, an outline of the curriculum ahead of time, and a small-group discussion guide will help facilitators prepare for their role in the curriculum. We also gave facilitators a letter of appreciation for their commitment to resident education that can help incentivize faculty and fellows, as this can count toward teaching scholarship for promotions in academic medicine.

The optimal frequency of delivering such a curriculum to residents is unclear. If done annually for all senior residents, there will inevitably be trainees who participated in the curriculum both as PGY 2s and then again as PGY 3s. However, repetition is important for learning, and small-group discussions were driven by learners’ questions and comments, which varied from year to year. Although residents who repeated the curriculum still found it to be beneficial, it was potentially less impactful the second time with respect to acquiring new skills for effective care escalation. We hypothesize that this was because the residents may have already acquired these skills, so there was less opportunity for them to be impacted by the curriculum.

The success of our escalation curriculum has spread to other audiences. We collaborated with nursing leadership at our institution who were interested in the curriculum. As a result, part of this curriculum has been incorporated into nurse training and was shared at nursing education forums.

We initially piloted a multimodal evaluation strategy in which we attempted to describe resident behavior at rapid response team activations; however, this was unsuccessful because this was a select clinical context that was limited by relatively infrequent occurrences, difficulties in completion of evaluation forms, and challenges attributing a change in resident behavior to the escalation curriculum. Significant adverse patient events were also too infrequent to use as feasible outcome measures. Consequently, we chose to utilize a survey questionnaire as our evaluation tool due to limited feasibility in identifying and monitoring opportunities for care escalation in the clinical setting.

Limitations

Our curriculum was delivered to residents at a large academic children's hospital, and therefore it may not be applicable to other types of training programs or institutions. However, this curriculum was designed to allow for easy implementation at other residency programs and across disciplines. Some elements of our curriculum, such as our individualized pediatric early warning score, may be specific to our institution. Still, we believe that our curriculum could easily be modified to substitute the systems and culture at another institution. Although our curriculum allows for flexibility in scheduling with delivery in both 1- and 2-hour sessions, we only evaluated the 2-hour workshop and the impact of a 1-hour session is not known. Finally, we did not evaluate long-term learning/reaction, change in resident behavior, or patient results (Kirkpatrick's third and fourth levels of evaluation).

Future Directions

Further study is needed to examine the impact of our escalation curriculum in the clinical setting, including resident behavior and patient care outcomes. A qualitative study of residents to explore their perceptions of the impact of the escalation curriculum in the clinical setting would be feasible and add further insight into its effectiveness. Surveying or interviewing learners months after the curriculum would be useful to determine its lasting impact on the residents’ comfort and ability to escalate care and the overall culture of escalation and communication. Furthermore, asking residents to reflect on cases in which they successfully or unsuccessfully escalated patient concerns would be valuable. We also believe that structured care escalation training would benefit all care team members, including nursing, interns, and senior residents in both pediatrics and other specialties; fellows; and junior faculty. Thus, we plan to implement this curriculum more broadly at our institution.

Appendices

A. Time Line for Curriculum.docx

B. Escalation Curriculum PowerPoint.pptx

C. Precurriculum Escalation Survey.docx

D. Postcurriculum Escalation Survey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank L. Barry Seltz, MD, for his contributions to this publication.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

None to report.

Ethical Approval

Reported as not applicable.

References

- 1.Boniatti MM, Azzolini N, Viana MV, et al. Delayed medical emergency team calls and associated outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(1):26–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31829e53b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quach JL, Downey AW, Haase M, Haase-Fielitz A, Jones D, Bellomo R. Characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving a medical emergency team review for respiratory distress or hypotension. J Crit Care. 2008;23(3):325–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams M, Hevelone N, Alban RF, et al. Measuring communication in the surgical ICU: better communication equals better care. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calzavacca P, Licari E, Tee A, et al. A prospective study of factors influencing the outcome of patients after a medical emergency team review. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11):2112 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-008-1229-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston M, Arora S, King D, Stroman L, Darzi A. Escalation of care and failure to rescue: a multicenter, multiprofessional qualitative study. Surgery. 2014;155(6):989–994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cioffi J, Salter C, Wilkes L, Vonu-Boriceanu O, Scott J. Clinicians’ responses to abnormal vital signs in an emergency department. Aust Crit Care. 2006;19(2):66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1036-7314(06)80011-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farnan JM, Johnson JK, Meltzer DO, Humphrey HJ, Arora VM. Resident uncertainty in clinical decision making and impact on patient care: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(2):122–126. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2007.023184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peebles E, Subbe CP, Hughes P, Gemmell L. Timing and teamwork—an observational pilot study of patients referred to a rapid response team with the aim of identifying factors amenable to re-design of a rapid response system. Resuscitation. 2012;83(6):782–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reese J, Simmons R, Barnard J. Assertion practices and beliefs among nurses and physicians on an inpatient pediatric medical unit. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(5):275–281. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2015-0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia C, Goolsarran N. Learning from errors: curriculum guide for the morbidity and mortality conference with a focus on patient safety concepts. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10462 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kern DE, Thomas PA, Howard DM, Bass EB. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zackoff MW, Real FJ, Abramson EL, Li S-TT, Klein MD, Gusic ME. Enhancing educational scholarship through conceptual frameworks: a challenge and roadmap for medical educators. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(2):135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schön DA. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDrury J, Alterio M.. Achieving reflective learning using storytelling pathways Innov Educ Teach Int. 2001;38(1):63–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/147032901300002864 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirkpatrick D. Revisiting Kirkpatrick's four-level model. Train Dev. 1996;50(1):54–57. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Time Line for Curriculum.docx

B. Escalation Curriculum PowerPoint.pptx

C. Precurriculum Escalation Survey.docx

D. Postcurriculum Escalation Survey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.