Abstract

Puberty research has been highly productive in the past few decades and is gaining momentum. We conducted an analysis of bibliographic data, including titles, abstracts, keywords, indexing terms, and citation data to assess the sheer numbers, audience and reach, publication types, and impact of puberty-related publications. Findings suggest that puberty-related publications are increasing in sheer numbers, and have reach in many fields as befits an interdisciplinary science. Puberty-related publications typically have higher impact in terms of citations than the journal averages, among the journals that published the most studies on puberty. Limitations of the field and recommendations for researchers to improve the impact and reach of puberty-related publications (e.g., clear conclusions in abstracts, highlighting the importance of puberty) are discussed.

Keywords: puberty, pubertal, publications, bibliometrics

Puberty is a process, driven by neuroendocrine changes (Dorn & Biro, 2011). It is also a social construct, a rite of passage marking the journey from childhood to being an autonomous adult member of society (Mendle, 2014). Despite widespread personal knowledge of what puberty is, there are varying definitions of puberty in research, ranging from biological neuroendocrine cascades to subjective experience to cultural construct. As observed in this special section on puberty, the paradoxically nebulous and concrete concept of puberty is important across many diverse fields, from anthropology to psychology, philosophy to medicine, cultural studies to developmental neuroscience. As detailed elsewhere in this issue, myriad biological and environmental factors have been associated with variations in pubertal maturation--both clinically atypical and normal (e.g., Aylwin, Toro, Shirtcliff, & Lomniczi, this issue; Mendle, Beltz, Carter, & Dorn, this issue). Abnormal and normal variations in puberty have also been associated with diverse physical, psychological, and social outcomes across the lifespan (e.g., Elks et al., 2013; Ullsperger & Nikolas, 2017). Certainly such an important developmental process, touching diverse fields, has been exhaustively researched. Or has it? In this paper, we conducted a bibliometric analysis of the field of puberty, broadly defined. Our overarching goal was to gauge the magnitude, audience, reach, and impact of publications on puberty, as well as a heuristic description of the types of articles and content published. Through this analysis, we identify gaps in the fields incorporating puberty research, and make recommendations for puberty researchers to improve the impact of publications on puberty in order to ensure that the knowledge on puberty expands and appropriately infuses developmental research in the decades to come.

Bibliometrics: an overview

Bibliometrics is the analysis of bibliographic data, such as the text of journal article citations, abstracts, keywords, or indexing terms. Researchers use bibliometric analyses of journal article citations and abstracts in diverse ways. For example, bibliometrics can identify publication trends in a body of research literature, such as the yearly publication volume of relevant articles and the number of journals publishing the articles on specific topics. Characteristics of authors, such as gender trends, may be determined as well (Sing, Jain, & Ouyang, 2017). Bibliometrics can establish the key journals of a research discipline, both in terms of which journals publish the greatest volume of articles in question, as well as which journals are most heavily referenced by researchers publishing in the field (Crawley-Low, 2006). It can describe the productivity of researchers from one country or institution (Kimball, Stephens, Hubbard, & Pickett, 2013) or worldwide productivity in the field of research (Hohmann, Glatt, & Tetsworth, 2017). Identifying themes across a body of research can inform researchers, administrators, and/or policymakers about the key findings or issues in the field (Hosey & Melfi, 2014).

Citation analysis, a type of bibliometrics in which attention is paid to the number of times articles are cited by other articles, can measure an author’s or journal’s influence in the field, for example, by the calculation of the h-index (an author-level metric corresponding to the number, h, of papers published that have been cited at least h times) or impact factor (a journal-level metric corresponding to the total number of citations in a given year divided by the number of publications in the previous two years), respectively. Citation analysis can also identify “citation classics” in a field, or articles that have been cited many times and for many years, and therefore may be considered highly influential (Garfield, 1977). Bibliometric analyses are particularly well-suited to gauging a field as a whole, and for giving a broad-stroke picture of the state of the field, its reach and impact, and its major players. To our knowledge, bibliometric analyses have not yet been applied to research on puberty. Thus, we use bibliometric analyses to examine our field to ascertain whether and what advances we are making and where our deficits are for promoting the inclusion of puberty research in key related fields. It is important to note that this bibliometric analysis is not a systematic review, but rather a larger-scale synopsis of the literature based on the most basic of search terms. As such, this manuscript provides a broad depiction of the field, but the wide net we cast is likely to include papers that are perhaps only marginally relevant to the topic of puberty, in addition to highly relevant publications.

Present study

In this study, we sought to answer four main questions that together would provide a “state of the field” of puberty. 1) How many publications included puberty as a keyword or key topic? This question gives the crudest measure of sheer numbers (e.g., the total number of publications identified through our search strategy). 2) Which journals published the most puberty-related publications, and which fields do they represent? This question will allow us to gauge the audience (journals) and reach (fields) of puberty in the larger scientific community, and to see whether puberty research is visible or where puberty researchers might focus their publication efforts for maximum impact. 3) What is the breakdown of publication type (e.g., reviews; case studies; empirical work), how was puberty considered (e.g., as the outcome vs. a predictor or moderator), and what were the broad content themes (e.g., most frequently examined puberty and related phenotypes)? Answers to questions will give us a slightly more refined assessment of the major foci of puberty research. Finally, 4) how are puberty-related publications cited relative to their non-puberty counterparts? This question will provide a metric for the impact of puberty research in the broader scientific community.

In order to gain both a broader perspective and a more detailed picture, for some analyses we used the span of 1990–2016 (e.g., for sheer numbers, audience, citations). However, not all questions were feasible to answer using this full span (1990–2016), so for each analysis we examined the earliest six years (1990–1995), and the latest complete six years (2010–2015 or 2011–2016 depending on the analysis, see Method section), to gain a comparison of ‘then’ and ‘now’. We restricted our date range to beginning in 1990 because we wanted a ‘long view’, but also a view using more current methods, with a feasible number of studies to review.

Method

We obtained citations and abstracts for the analyses by searching two bibliographic databases, PubMed and Web of Science-Core Collection (hereafter Web of Science or WOS). PubMed was chosen because it is the world’s preeminent source for biomedical research articles, especially across all aspects of human physical and mental health. Web of Science was chosen because it indexes a very broad collection of core journals across many research disciplines (not weighted more heavily for biomedical fields), and because it maintains citation statistics for published articles. Each of these databases has different strengths, and as such, for some questions (e.g., citations) Web of Science data was used, whereas for other questions (e.g., publication type) PubMed data was used. This methodology was not intended to be a systematic review, but rather a broad approach to gain a larger-scale, heuristic picture of the state of the field in regard to publications on puberty.

Search Strategy.

Our primary searches were as follows: We used the Web of Science-Core Collection (databases included are presented in Appendix 1), to search work published from 1990–2016 that included the phrase “puberty or pubertal” as Topic, and then limited the document type to “article” or “review” in order to focus on scholarly output (e.g., excluding conference proceedings which may not be peer reviewed, or books or book chapters which may not focus on presenting primary data). In PubMed, we searched for works published from 1990–2016 that included the terms “puberty” or “pubertal” among all titles and abstracts, as well as the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term “puberty”. Publications identified by these searches are hereafter referred to as “puberty-related publications”. Please see Appendix 1 for details on our search strategy for all searches used in this manuscript. We generated six datasets: puberty-related articles from PubMed for the intervals 1990–2016, 1990–1995, and 2011–2016 (the full focal period, and the first and last six-year periods to compare earlier vs. more recent trends), and puberty-related articles from Web of Science for the same three intervals.

Neither PubMed nor Web of Science was adequate for obtaining accurate publication statistics for the Journal of Research on Adolescence (JRA) because PubMed selectively indexed JRA until 2016 (after which it has been comprehensively indexed), and Web of Science coverage of JRA began in 1994. Since JRA is the home of this special issue, we used a combination of Web of Science and the PsycInfo database, which has indexed JRA since its inception in 1991, to conduct parallel analyses, particularly for questions of impact (see below).

Sheer Numbers

To address questions of sheer numbers, we report the numbers of puberty-related publications yielded from the PubMed and Web of Science searches from 1990–2016. We then plotted the number of puberty-related publications and total publications from the top journals in each set (defined as the 20 journals ranked as publishing the most puberty-related articles) in order to visualize publication trends from 1990–2016.

Audience and Reach

Top Journals (Audience).

As noted above, top journals were defined as the top 20 journals (including ties) that published the greatest number of puberty-related publications during each publication date span (e.g., 1990–2016, 1990–1995, and 2011–2016) for both the Web of Science and PubMed searches. For each top journal, we recorded the total number of articles published in the time-span as well as the number of ‘puberty-related’ articles discovered through our searches. We calculated the percentage of puberty-related publications in each top journal from those numbers (‘puberty-related’ articles/total articles*100). As with the top journals, we recorded the total number of puberty-related publications, as well as the percentage of puberty-related publications for JRA using the PsycInfo search described above to determine the percentage of puberty-related publications in JRA.

Represented Fields (Reach).

To assess reach, we utilized the Web of Science Journal Citation Reports® categories as proxies for fields of study. Specifically, we entered each of the top journals from the Web of Science search from each publication date range into Journal Citation Reports®, viewed and recorded the Web of Science categories they represent, and recorded the journals’ rank (for 2016, or the latest indexed year) for each Web of Science category. We did the same for JRA. We summarized the relative ranks of the top journals in their respective fields through summary statistics (minimum, maximum, mean, median, mode). We only used the Web of Science searches for reach analyses because PubMed is primarily a biomedical research database, and thus is likely to be biased to include biomedical fields and under-representing social science fields.

Publication Type

In order to obtain a general picture of the breakdown of the prevalence of different types of puberty-related publications, we hand-coded abstracts from the PubMed search, after limiting to those with puberty as a Major MeSH heading, and including only human research (e.g., see Appendix 1, note that this is specifically a search of Medline). We chose to limit the search strategy in this way because MeSH terms are very carefully assigned to articles, and by selecting the more conservative dataset of articles with puberty as a Major MeSH heading, we were likely to get only the articles with a puberty phenotype as a truly focal construct. We imported the PubMed library into Endnote Desktop X8 citation management software, and created the following list of hand-coded categories, separately for articles published from 1990–1995, and 2010–2015 (since there can be up to an 18-month lag on assignment of MeSH terms, it is conceivable that many 2016 articles had not yet been assigned MeSH terms at the time of coding). One author coded each article using the definitions provided below, and the first author reviewed the hand-coded categories, recoding (e.g., moving an article to a different hand-coded category) as needed (this occurred < ~5% of the time):

Case Studies included case reports examining one or a few atypical cases, describing the pubertal development of a child or handful of children with a particular disease.

Not English included English abstracts for which the article was not in English and the abstract contained insufficient information to categorize into another, informative group.

Puberty Not Examined primarily included articles that used puberty to describe the sample selection (e.g., a specifically pre-pubertal or post-pubertal sample, or ‘during puberty’ as a descriptor based on an age-range), and also included articles that mentioned puberty as a future direction or in the rationale for the study in the abstract, as well as a few articles that may have been incorrectly indexed (e.g., we found no mention of puberty in the title, abstract, or full text, only in indexing terms, for example Merten, 2010). This is a meaningful group, as puberty was often considered carefully, but not actually tested in hypotheses.

Puberty Is Covariate included articles where the abstract specifically named a pubertal maturation phenotype as a “control” or “covariate” and not a focal predictor.

Reviews, Qualitative, etc., comprised mainly of reviews, but also included a number of commentaries, editorials, and letters, as well as manuscripts describing larger studies or clinical trials that include puberty as a focal phenotype, but did not present specific findings. This hand-coded category also included some descriptive, qualitative studies (without accompanying statistics).

Meta-Analyses includes only meta-analyses related to puberty.

Puberty Is Outcome included a wide range of study types, most notably any studies that compared the timing or rate of puberty across measures, disease case/control groups, cultures, or history, studies of inducing or delaying puberty through drug treatment, and studies examining various predictors of the onset or rate of puberty.

Puberty Is Predictor/Moderator included a wide range of study types, but mainly studies examining the influence of a pubertal maturation phenotype in relation to a particular mental or physical health outcome. This hand-coded category also included mean-level comparisons across pre-pubertal vs. pubertal groups on a given outcome, and several publications where genes previously related to age at menarche were associated with other phenotypes.

Some articles were difficult to place in one hand-coded category or another, and coding was necessarily subjective. We urge readers to interpret findings as a heuristic rather than fact. Please also see Appendix 2 for further information on common coding decisions, and further details and limitations of this coding approach.

Hand-coding category content.

After hand-coding abstracts, we used the text-mining capabilities of the software program VantagePoint Academic (Version 9.5; Search Technology Inc., 2016; a stand-alone text mining package) to identify themes and topics within each main substantive category from the hand coding: ‘puberty is a predictor/moderator’, ‘puberty is outcome’, ‘meta-analyses’, and ‘review, qualitative, etc.’ from 1990–1995 and 2010–2015. VantagePoint executed a natural language processing algorithm on the abstracts of each of the eight data sets, and sorted to find the most frequently found keywords and phrases. The top 100 terms in each file were exported to the online word cloud generator WordItOut (worditout.com) to visualize the content of each hand-coded category, after excluding numbers (e.g., .01) and abstract headers (e.g., abstract, conclusions) from these lists of keywords and phrases.

Impact

We used Web of Science to record the citation statistics for the top journals both by total publications and puberty-related publications as of 8/23/2017 in order to compare the impact of puberty-related publications (by recording citation statistics for only the set of puberty-related publications found through the Web of Science search in each top journal) against non-puberty-related publications in the same outlets (by recording citation statistics for all publications in each top journal).1 PubMed does not include citation statistics, and thus was not used to assess impact (e.g., citation statistics, impact comparisons, and rank).

Impact Comparisons.

We calculated the ratio of the average citations per item (total citations/the number of articles) for the puberty-related publications and journal total articles, as well as the ratio of the average citing articles per item (total citing articles/the number of articles) for puberty-related and journal total articles. If the puberty-specific ratio was higher than the journal average ratio, we concluded that puberty-related publications had a higher impact than the journal average. If the reverse was true, we concluded that puberty-related publications under-performed in terms of impact relative to the journal average.

Rank.

We also sought to quantify the relative rank of the top journals identified through our search of Web of Science within their respective Web of Science categories as an additional metric impact. We calculated rank as a percentile score where 1% is the highest ranked journal in a given category and 100% is the lowest.

Results

Sheer Numbers

How many publications included puberty as a keyword or key topic?

Web of Science reports 35,736 articles published with Puberty or Pubertal as a topic from the earliest indexed date through 12/31/2016. Prior to 1989, there were 4,943 puberty-related publications identified, whereas 30,793 occurred in our broader focal period, from 1990–2016. We then selected only articles and reviews (to maximize the likelihood that the articles were peer reviewed), yielding 27,348 articles. Results from the search of PubMed yielded 42,082 articles published with Puberty or Pubertal as a title or abstract keyword or Puberty as a MESH term from the earliest indexed date through 12/31/2016. Prior to 1989, 12,626 puberty-related articles were published, and 29,456 occurred in our broader focal period, from 1990–2016.

Publication Trends.

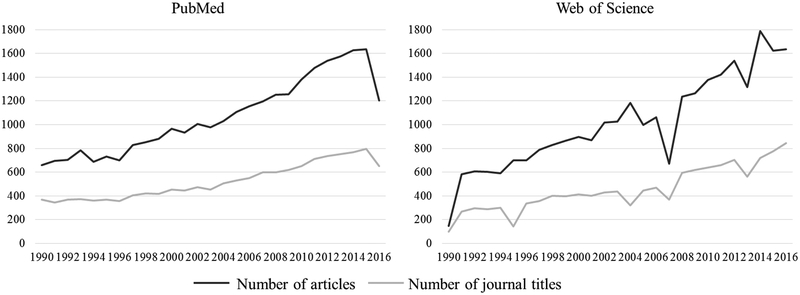

In general, the total number of puberty-related publications and journals publishing work on puberty has increased (see Figure 1). The increase in puberty-related publications was roughly eight-fold from 1995–2016, and the increase in total journals publishing puberty-related publications increased roughly five-fold according to the Web of Science search, and two-fold according to the PubMed search. The dip in PubMed articles and journal titles for 2016 may be due to a lag in indexing, rather than a true dip in publications.

Figure 1.

Puberty-related Publication Treands

WOS = Web of Science. The left plot shows the number of articles (dark line) and journal titles (light line) per year included in the search results from PubMed that included the terms “puberty” or “pubertal” among all titles and abstracts, as well as the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term “puberty”. The right plot shows the number of articles (dark line) and journal titles (light line) per year included in the search results from WoS that included the phrase “puberty or pubertal” as Topic, and then limited the document type to “article” or “review”. Quantity of articles/journals are displayed on the Y-axis. Publication year is displayed on the X-axis.

Audience and Reach

Which journals published the most puberty-related publications, and which fields do they represent?

Top Journals (Audience).

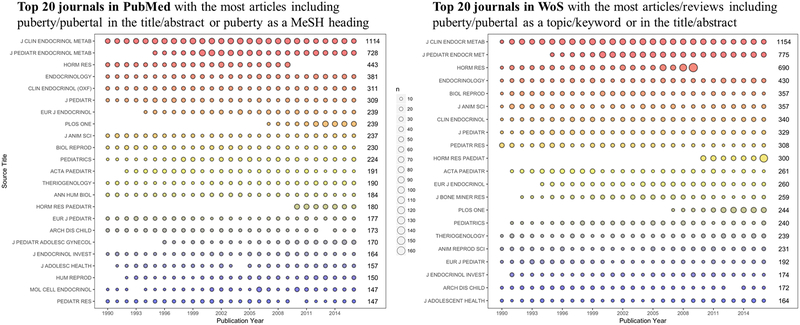

The top journals (i.e., that published the most puberty-related publications), and the numbers of puberty-related publications in those journals from 1990–2016 are summarized in bubble plots (Figure 2, PubMed on the left, Web of Science on the right). As shown in Table 1, which presents the top journals from Web of Science and PubMed (sorted according to the Web of Science ranking), most (19/25) of the same top journals were identified through both searches despite differences in search strategy and databases. Isolated large bubbles might indicate special issues where puberty was a focus. Given the changing landscape over time, we also examined bubble plots for top journals from the years 1990–1995 (Figure S1) and 2011–2016 (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Number of puberty articles published in top journals from PubMed and Wos searches: 1990–2016

WoS = Web of Science. The left panel shows the top 23 journals publishing the highest quantity of papers from PubMed that included the terms “puberty” or “pubertal” among all titles and abstracts, as well as the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term “puberty”. The right panel shows the top 21 journal publishing the highest quantity of papers from WoS that included the phrase “puberty or pubertal” as Topic, and then limited the document type to “article” or “review”. There are more than 20 journals listed because ties were included. Bubble sizes correspond to the quantity of puberty papers published in that given year. Totals for the entire period of 1990–2016 are presented along the right side of each plot. Most gaps in article publication are due to changes in coverage of journals indexed by PubMed and WOS respectively. Horm Res Paediatr is the same journal as Hormone Res, switching names ~2010. Thus, this journal actually consistently published puberty research across this timespan. Plos One was established in 2001 and later became indexed, explaining the lack of puberty-related publications prior to 2007/2009.

Table 1.

Top journals, publishing the most puberty-related publications, from 1990–2016.

| PubMed ranking by # of articles | Journal title | WOS ranking by # of articles |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM | 1 |

| 2 | JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM | 2 |

| 3 | HORMONE RESEARCH | 3 |

| 4 | ENDOCRINOLOGY | 4 |

| 8 | BIOLOGY OF REPRODUCTION | 5 |

| 5 | CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY | 6 |

| 7 | JOURNAL OF ANIMAL SCIENCE | 6 |

| 5 | JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS | 7 |

| 20 | PEDIATRIC RESEARCH | 8 |

| 13 | HORMONE RESEARCH IN PAEDIATRICS | 9 |

| 11 | ACTA PAEDIATRICA | 10 |

| 6 | EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENDOCRINOLOGY | 11 |

| 26 | JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH | 12 |

| 6 | PLOS ONE | 13 |

| 9 | PEDIATRICS | 14 |

| 10 | THERIOGENOLOGY | 15 |

| 23 | ANIMAL REPRODUCTION SCIENCE | 16 |

| 14 | EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS | 17 |

| 17 | JOURNAL OF ENDOCRINOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION | 18 |

| 15 | ARCHIVES OF DISEASE IN CHILDHOOD | 19 |

| 18 | JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT HEALTH | 20 |

| 12 | ANNALS OF HUMAN BIOLOGY | 28 |

| 19 | HUMAN REPRODUCTION | 22 |

| 16 | JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC AND ADOLESCENT GYNECOLOGY | 51 |

| 20 | MOLECULAR AND CELLULAR ENDOCRINOLOGY | 21 |

Note. WoS = Web of Science. Journal titles are ranked in terms of the top journals publishing the most puberty-related publications from the Web of Science search (from 1990–2016). Ranks are provided for every journal from both searches.

1990–2016.

The PubMed search yielded 23 top journals that published the most puberty-related publications (Supplemental Table S1, column A; Figure 2). The top three journals were Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, publishing 1,114 puberty-related publications from 1990–2016, the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, publishing 728 puberty-related publications, and Hormone Research, publishing 443 puberty-related publications from 1990–2016 (Table S1, column C). This reflected 5.32%, 18.69%, and 15.66%, respectively, of the total articles published in each journal, according to the articles included in PubMed (Table S1, column D). Hormone Research in Paediatrics (a continuation of Hormone Research; they are the same journal with a title change in 2011) published the highest percentage of puberty-related publications according to PubMed: 20.17% (Hormone Research, the title prior to 2011 also included a high percentage of puberty-related publications at 15.66%), and the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism was close behind at 18.69%. Overall, the top journals averaged about 5.21% of the total articles from 1990–2016, being highly relevant to puberty (e.g., including puberty/pubertal in the title, abstracts, keywords, or MeSH headings).

The Web of Science search also yielded 21 top journals (Table S2, Column A; Figure 2), including the same three top journals (each publishing > 690 puberty-related articles according to WoS; Table S2, column C). The average percentage of puberty-related publications in the top WoS journals from 1990–2016 was 4.14% (Table S2, column D); ranging from 19.81% (Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism) and 11.97% (Hormone Research in Paediatrics) to 0.70% (Journal of Bone and Mineral Research) and 0.14% (PLoS One).

1990–1995.

The PubMed search yielded 22 top journals that published puberty-related articles from 1990–1995 (Table S3, column A; Figure S1). The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism and Hormone Research published > 100 puberty-related publications in the six-year timespan (Table S3, column C), reflecting 6.38% and 14.01% of the total articles published, according to PubMed (Table S3, column D). Annals of Human Biology (14.95%) and Hormone Research (14.01%) published the highest percentage of puberty-related articles. Overall, the top journals averaged about 4.58% of the total articles from 1990–1995 being relevant to puberty.

The Web of Science search yielded 22 top journals (Table S4, Column A; Figure S1), with the top three journals, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, Pediatric Research, and Hormone Research, each publishing > 100 puberty-related publications (Table S4, Column C), comprising 0.88% to 12.74% of the total articles (Table S4, Column D) from 1990–1995. Hormone Research (12.74%) and Animal Reproduction Science (8.38%) published the highest percentage of articles with a focus on puberty. Overall, the top journals averaged about 3.39% of the total articles from 1990–1995 being relevant to puberty. Although the order differed somewhat, 19 of the total 25 top journals identified by Web of Science or PubMed were on both lists.

2011–2016.

The PubMed search yielded 24 top journals that published puberty-related articles from 2011–2016 (Table S5, column A; Figure S2), with similar top journals to the other searches; PLOS One, the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, Hormone Research in Pediatrics, and Endocrinology each published > 100 puberty-related publications (Table S5, column C), reflecting 0.14% (PLOS One publishes a very high quantity of papers in many disciplines) to 18.50% of the total articles published, according to PubMed (Table S5, column D). Hormone Research in Pediatrics (18.50%), Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism (15.63%), Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology (13.40%), and Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology (10.62%) published the highest percentage of puberty-related publications. Overall, the top journals averaged about 4.39% of the total articles from 2011–2016, being relevant to puberty.

The Web of Science search yielded 27 top journals (Table S6, Column A; Figure S2). The same five top journals (PLOS One, Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, Hormone Research in Pediatrics, and Endocrinology) each published > 100 puberty-related publications from 2011–2016 (though in a different rank order; Table S6, Column C), ranging from 0.14% to 16.73% of the total journal output (Table S6, Column D). The Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology (17.20%), the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism (16.73%), and Hormone Research in Pediatrics (11.15%), published the highest percentage of puberty-related publications. The top journals averaged about 4.21% of the total articles from 2011–2016 being relevant to puberty. Although the order differed somewhat, 23 of the total 28 top journals identified by Web of Science or PubMed were on both lists.

JRA.

According to Web of Science, JRA published 8532 articles from 1994–2016, 46 of which included puberty (5.54%). From 1994–1995, one article (3.03% of the total articles) was published in JRA, whereas from 2011–2016, 18 puberty-related articles were published (4.49% of the total articles; see Table S7).

Represented Fields (Reach).

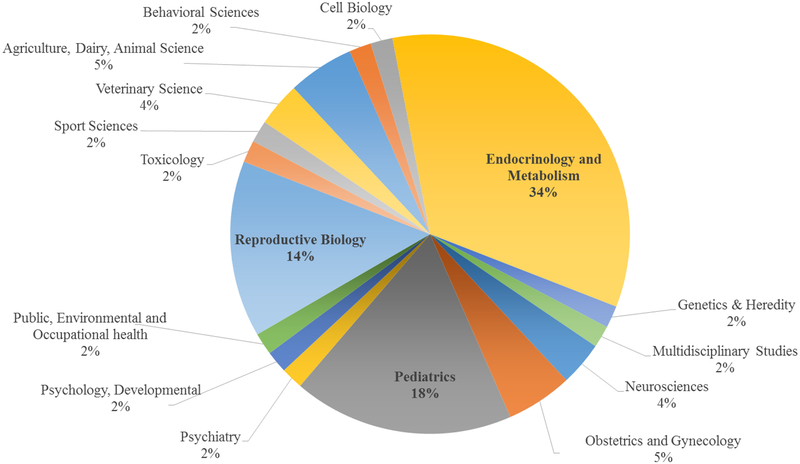

Figure 3 depicts the range and relative representation of Web of Science categories from the top journals publishing puberty-related publications across the Web of Science searches. The top journals represented 16 Web of Science categories, spanning categories with a focus on animals (Agriculture, Dairy, Animal Science; Veterinary Science), as well as biological (Cell Biology; Genetics and Heredity), physiological (Endocrinology and Metabolism; Reproductive Biology), medical (Obstetrics and Gynecology; Pediatrics), and psychological domains (Behavioral Sciences; Psychiatry; Psychology, Developmental), among others (Multidisciplinary Sciences; Neurosciences; Public, Environmental, and Occupational Health; Sport Sciences; Toxicology). The represented Web of Science categories indicate a relatively wide breadth of reach for puberty-related publications. The best-represented Web of Science categories were Endocrinology and Metabolism (34% of the top journals across all searches were indexed in this category); Pediatrics (18%), and Reproductive Biology (14%).

Figure 3.

Represented WoS Categories (fields reached) by top journals from Web of Science Search

Web of Science categories are assigned to each journal as a proxy for the field that the journal belongs to. Journals may have multiple assigned categories/fields. This figure displays the WoS categories tapped by every journal (41 in total) identified as a top puberty journal as defined by any of the 3 WoS searches (all three publication date ranges). The percentage of the top journals that were indexed as belonging to each field is depicted to display the range in fields and the best-represented fields that are exposed to relatively high amounts of puberty-related publications.

Types of publications

What is the breakdown of publication type, how was puberty considered, and what were the content themes?

1990–1995.

Results from our hand-coding of PubMed articles that were coded with Puberty as a Major MeSH heading from 1990–1995 show that out of 689 articles, there were 25 case studies (3.63%), 48 English Abstracts that did not contain sufficient information to confidently code (6.97%), 113 articles that did not include either primary or empirical data (e.g., were reviews, qualitative research, notes, letters; 16.40%), one meta-analysis (0.10%), 36 articles where puberty was explicitly named as a covariate (5.22%), 232 articles where puberty was the main outcome of interest (33.67%), 203 articles were puberty was a focal predictor or moderator (29.46%), and 31 articles where puberty was not explicitly examined (e.g., puberty/pre-pubertal/post-pubertal was used as a sample descriptor or sampling technique; 4.50%). The results of the hand-coding are available in both .csv and .ris files in addition to an Endnote library published in the Purdue University Research Repository (https://purr.purdue.edu/publications/2951/1).

Hand-coding category content.

The hand-coding category content from text-mining analyses is visualized in a series of word clouds (only the top 100 terms are included in the visualization, data available upon author request). In the 113 articles that were primarily reviews, qualitative studies, comments, or research notes (Figure S3), the top keywords/phrases were puberty, development, girls, onset, and adolescence (each appearing in more than 10 records). Notably, the keyword ‘girls’ appeared in 13 records, and ‘boys’ in eight records.

In the 223 articles where puberty was the main outcome of interest, ‘age’ (113 records) and ‘menarche’ (97 records) were the most frequent keywords (Figure S4). ‘Girls’ appeared in 83 records, whereas ‘boys’ appeared in 49 records. The top keywords/phrases related to measurement of puberty appearing in the most records were menarche-related (menarche: 97 records; menarcheal age: 21 records), LH (luteinizing hormone: 28 records), FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone: 16 records), pubertal growth spurt (16 records), pubertal stage: 15 records), followed by timing (13 records), testosterone (13 records), and early puberty (12 records). Other notable top keywords highlight constructs likely conceptualized as predictors of puberty in these papers, including weight (29 records; body weight: 10 records; body mass index: eight records), growth hormone (18 records), treatment (18 records), and bone age (12 records).

Finally, in the 203 articles where puberty was a focal predictor or moderator (Figure S5), the top terms remained women (29 records), pubertal maturation (21 records), and rate (21 records). ‘Males’ was found in 18 records. Notable top keywords that likely highlight outcomes associated with puberty include WHR (waist-hip ratio: 27 records), sleep (26 records), weight (20 records), lipoprotein (17 records), IFGBP-3 (the insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 gene; 16 records), and insulin (10 records) and diabetes (nine records). The most frequent keywords related to the measurement of puberty were pubertal stage (19 records; pubertal status: 15 records), testosterone (19 records), and menarche (17 records), onset (17 records), followed by estradiol, FSH, and LH (each in 13 records).

2010–2015.

From 2010–2015 there were about twice as many publications on puberty as there were from 1990–1995. Out of 1,561 articles, there were 49 case studies (3.14%), 15 English Abstracts that did not contain sufficient information to confidently code (0.96%), 345 articles that did not include either primary or empirical data (e.g., were reviews, qualitative research, notes, letters; 22.10%), 26 meta-analyses/analyses of pooled data (1.67%), 17 articles where puberty was explicitly named as a covariate (1.09%), 438 articles where puberty was the main outcome of interest (28.06%), 544 articles were puberty was a focal predictor or moderator (34.85%), and 127 articles where puberty was not explicitly examined (e.g., puberty/pre-pubertal/post-pubertal was used as a sample descriptor or sampling technique, and in a few cases, apparent miss-indexed articles; 8.14%).

Hand-coding category content.

In the 330 articles that were primarily reviews, qualitative studies, comments, or research notes, similar keywords/phrases rose to the top in 2011–2016 as did from 1990–1995 (Figure S6), including puberty (140 records), adolescence (54 records), development (50 records), girls (45 records), and onset (41 records). The gender gap grew more pronounced with ‘girls’ appearing in 45 records and ‘boys’ in 28 records. Additional keywords of interest included timing (35 records), menarche (29 records), patients (20 records), obesity (20 records), treatment (19 records), control (17 records), pregnancy (12 records), kisspeptin (13 records), behavior (nine records), genes (seven records), and breast cancer (six records), suggesting the majority of review type articles focused on treatment studies, the process of puberty, and correlations with health outcomes (e.g., pregnancy, obesity, breast cancer) and genetics.

In the 26 meta-analyses/pooled data analyses, age (20 records), menarche (15 records), and menarcheal age (six records) were the top keywords. Other keywords of note included association (11 records), girls (five records), pubertal timing (five records), (earlier/early menarche, four records each). ‘Boys’ only appeared in two records. Potential correlates of puberty included ‘genes’ (three records), obesity (three records), growth (two records), and depression, various cancers, peers, ethnicity, sexual behavior, and stroke (appearing in one record each). This may indicate that most meta-analytic and pooled data studies in this timeframe examined age at menarche, in relation to several health and psychosocial outcomes. Studies on the genetics of puberty were also highly represented.

In the 438 articles where puberty was the main outcome of interest, again age (294 records), and menarche (220 records) appeared most often (Figure S7). ‘Girls’ appeared in 178 records, whereas ‘boys’ appeared in only 96 records, showing the persistent gender gap in puberty research (see also Deardorff, Hoyt, Carter, & Shirtcliff, this issue; Mendle et al., this issue). Body Mass Index (BMI) occurred in 46 records, suggesting that BMI was a highly studied focal predictor. The top keywords/phrases related to measurement of puberty appearing in the most records were menarche (220 records), onset (94 records), timing (57 records), breast development (27 records), pubic hair development (25 records), perhaps suggesting a shift from primarily hormonal measures (all of which were found in < 18 records) to slightly more secondary sex characteristic measures. Other notable top keywords highlight an increased focus on the secular trend (22 records) in pubertal timing, and likely predictors of puberty, including height (59 records), weight (39 records), birth weight (20 records), obesity (19 records), and mothers (18 records).

Finally, in the 544 articles where puberty was a focal predictor or moderator (Figure S8), the top terms remained age (265 records), puberty (209 records), and menarche (168 records). Girls appeared in 174 records, whereas boys appeared in 115 records. Notable top keywords that likely highlight outcomes associated with puberty include height (61 records), BMI (59 records), obesity (37 records), weight (37), depressive symptoms (28 records), depression (25 records), menopause (24 records), body composition (22 records), overweight (19 records), physical activity (19 records), diabetes (17 records), breast cancer (16 records) and asthma (10 records). The most frequent keywords related to the measurement of puberty were menarche (168 records), pubertal timing (55 records), onset (53 records), pubertal status (48 records), early menarche (41 records), pubertal stage (37 records), timing (37 records), testosterone (32 records), and Tanner Stages (20 records).

Impact

How are puberty-related publications cited relative to their non-puberty counterparts?

1990–2016.

Citation statistics could be calculated by Web of Science for 10 of the 21 top journals for puberty-publications identified through Web of Science from 1990 to 2016 (Table S2). In eight cases (80%), puberty-publications were cited by more articles than the journal average (e.g., out-performed the journal average; Table S2, Column P). However, in terms of total citation count, in only four cases (40%), puberty-related publications were more highly cited than the journal average (Table S2, Column M), suggesting that for most journals, puberty-related publications under-performed relative to the journal in total citations. The average citation metrics across all 10 journals confirmed this pattern, suggesting that puberty-related publications slightly under-performed journal averages both in terms of total citation counts (by a difference of 0.63 citations) but out-performed journal averages in terms of citing articles (by a difference of 5.27 citing articles).

1990–1995.

Citation statistics could be calculated by Web of Science for 20 of the 22 top journals for puberty-publications identified through Web of Science from 1990 to 1995 (Table S4). In 15 cases (75%), puberty-publications were cited by more articles than the journal average (e.g., out-performed the journal average; Table S4, Column P). However, in terms of total citation count, in only 10 cases (50%), puberty-related publications were more highly cited than the journal average (Table S4, Column M), suggesting that in general, puberty-related publications performed near to the journal averages in total citations. The average citation metrics across all 20 journals suggested that puberty-related publications out-performed journal averages both in terms of total citation counts (by a difference of 4.84 citations) and citing articles (by a difference in 8.80 citing articles).

2011–2016.

Citation statistics could be calculated by Web of Science for 24 of the 27 top journals for puberty-publications identified through Web of Science from 2011 to 2016 (Table S4). In 22 cases (92%), puberty-publications were cited by more articles than the journal average (e.g., out-performed the journal average; Table S6, Column P). In terms of total citation count, in 19 cases (79%), puberty-related publications were more highly cited than the journal average (Table S6, Column M), suggesting that in general, puberty-related publications out-performed the journal averages in total citations. The average citation metrics across all 24 journals suggested that puberty-related publications out-performed journal averages both in terms of total citation counts (by a difference of 11.01 citations) and citing articles (by a difference in 9.63 citing articles). Together, these results suggest that puberty-related publications are increasing in their impact relative to journal averages over time.

JRA.

Puberty-related publications in JRA have been more highly cited than total articles across each publication year range (Table S7, Columns K-P).

Rank.

The summary statistics for the Web of Science rankings of the journals within their respective Web of Science categories are presented in Table 2 (full details provided in Table S8). Overall, the journals were in the top one third of their respective Web of Science categories, on average (32%). The median rank overall was 28%, and the most frequent (modal) rank was 10%. Four of the 41 journals ranked in the top 5%, and 11 ranked in the top 10%, indicating that puberty-related publications are indeed getting into Web of Sciences’ most highly-ranked journals in the field.

Table 2.

Rank statistics of top journals for puberty-related publications.

| Average | Median | Mode | Lowest | Highest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Web of Science Category indexed | 32% | 24% | 10% | 2% | 97% |

| Secondary Web of Science Category indexed | 41% | 43% | N/A | 4% | 86% |

| Tertiary Web of Science Category indexed | 21% | 21% | N/A | 14% | 29% |

| Total | 32% | 28% | 10% | 2% | 97% |

Top journals were identified as top 20 journals (including ties) that published the greatest number of puberty-related publications during each publication date span. Relative rank of the top journals identified through our search of Web of Science within their respective Web of Science categories was calculated as a percentile score where 1% is the highest ranked journal in a given category and 100% is the lowest.

We next characterized the ranks of the consistently top journals in which puberty-related publications appear. In terms of quantity of puberty-related publications, the top journals were the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, ranked 14th percentile in Endocrinology and Metabolism, Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, ranked 88th percentile in Endocrinology and Metabolism, and 66th percentile in Pediatrics, Hormone Research, ranked in the 78th percentile in the Web of Science category Endocrinology and Metabolism, and the 45th percentile in Pediatrics, Endocrinology, ranked in the 21st percentile in the Web of Science category Endocrinology and Metabolism, and more recently, PLOS One, ranked 25th percentile in Multidisciplinary Sciences. The consistently top journals in terms of percentage of puberty-related publications were Hormone Research (in Pediatrics), Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, (ranks presented above) and Annals of Human Biology, ranked 44th percentile in Biology. Thus, the very top journals in terms of outlets for the most puberty-related publications are not particularly highly ranked in their respective fields.

Top Cited Journals

As a supplemental analysis, we also determined the top 50 journals that puberty-related publications themselves most frequently cite. This analysis gives a broader view of the types of journals that are important for puberty researchers. Specifically, we conducted this analysis for the time periods of 1990–1995 and 2011–2016 and for the Web of Science search (since citation metrics are only available in Web of Science). We used VantagePoint software to extract and aggregate the journal titles from the Web of Science “cited references” field for each article.

1990–1995.

Seventy-seven percent (77%) of the 1990–1995 top journals were also among the 50 most highly cited journals in the same time period. The top 10 most-cited journals that were not included in the top journals list were (in descending order) Journal of Applied Physiology, Radiology, Journal of Comparative Neurology, Metabolism, Annals of Human Biology, Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, Recent Progress in Hormone Research, Life Sciences, Cancer, and JAMA.

2011–2016.

Seventy percent (70%) of the 2011–2016 top journals were also among the most highly cited journals in that interval. The top 10 most-cited journals not included in the top journals list were (in descending order) Biological Psychiatry, Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, Molecular Endocrinology, Diabetes, Physiology & Behavior, JAMA, Neuroendocrinology, Developmental Psychology, Annals of the New York Academy of Science, and Brain Research. See Supplemental Table S9 for lists of the journals most cited by puberty papers from 1990–1995 and 2011–2016.

Discussion

We presented the first bibliometric analysis of the field of puberty research, focusing on the years 1990–2016. We investigated four main questions: 1) sheer numbers: How many publications included puberty as a keyword or key topic?; 2) audience and reach: Which journals published the most puberty-related publications, and which fields do they represent?; 3) What is the break-down of publication type, how was puberty considered, and what were the broad content themes?; and 4) impact: How are puberty-related publications cited relative to their non-puberty counterparts? Our findings regarding each question are summarized below. We also include recommendations for puberty researchers for the future in order to increase the visibility and impact of puberty research within the broader scientific community.

Sheer Numbers

The numbers of puberty-related publications increased over time, in an approximately linear fashion, indicating a consistently growing interest in and output of puberty research. We take this as a positive sign, suggesting that the importance of puberty as a developmental process or social construct is infiltrating research on a wide variety of related topics, including adolescent development. This trend may be in part due to an overall increase in publications over time.

Audience and Reach

Audience.

There was some consistency across searches in terms of top journals that published the highest quantity of puberty-related publications, but there was also some variation in the journals included via the two very different search strategies. The top journals that appeared on both PubMed and Web of Science searches, particularly in the more recent time-frame of 2011–2016, are likely to continue to publish puberty-related publications, and may be good targets for puberty researchers to consider when submitting a manuscript. Across searches and publication dates, the very top journals for publishing puberty-related publications in terms of the quantity of articles were Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, Hormone Research (in Pediatrics), Endocrinology, and more recently, PLOS One. The top journals for publishing a high percentage of puberty-related publications were Hormone Research (in Pediatrics), Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, and Annals of Human Biology. Future work on puberty submitted to these journals may have the highest likelihood of success in the review process, provided that the topical area of interest and measure of puberty fits within the journal mission. JRA published a percentage of articles on puberty that was in line with the average of the top journals (and this metric will increase by virtue of this special issue), indicating that JRA is a good outlet for puberty research in the future. It is surprising how few adolescence journals appeared on the top lists for puberty-related publications. This is a particularly important limitation in the field of developmental science. Researchers certainly will need to push puberty into those journals, even if only as a covariate or sample descriptor, as puberty is so highly relevant to adolescent health and development. Using measures of puberty that are appropriate for the question under study as well as acknowledging their strengths and limitations would be important in enhancing publication success.

Reach.

Puberty research is highly represented in the fields of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Pediatrics, and Reproductive Biology. Puberty research, only considering the top journals in terms of quantity of puberty-related publications, also represents a wide variety of fields, highlighting the interdisciplinary nature of puberty as a phenotype. However, puberty research can and should be more visible to the broader scientific community. While there is no bar for whether our audience and reach is “good” or lacking, it is somewhat surprising that none of the top puberty journals fell in the fields of Anthropology, Cultural Studies, Developmental Biology, Health Policy and Services, Social Sciences, or Substance Abuse, Web of Science categories for which we might expect puberty research to be relevant. Further, the representation of developmental science journals, including those with an adolescent focus, was surprisingly low. These areas are limitations of the field that represent great opportunities for increasing the reach and impact of puberty research. For example, puberty research can better inform developmental science by targeting publications in Developmental Psychology, Child Development, Development and Psychopathology, and JRA.

Our analysis of Web of Science categories was only for the top journals across Web of Science searches. We chose this strategy because Web of Science produces the categories we used to quantify reach, and because PubMed is a biomedical database, we thought including the top journals from PubMed might miss-represent reach by more heavily weighting biomedical fields. It is highly likely that there are many puberty-related publications across more Web of Science categories (published in journals that were not identified as “top” journals for puberty-related publications), albeit in fewer numbers. Nonetheless, targeting highly ranking journals in under-represented Web of Science categories would increase the reach of puberty research in the scientific community more broadly.

Publication Type

It is important to highlight that results from this section draw from a very specific search: PubMed is a biomedical database (and thus more likely to index biomedical research at the expense of other fields). Further, including only articles with puberty as a Major MeSH heading ensures that we were more likely to review abstracts of publications highly relevant to puberty, but also means that we are missing a very large swath of research on puberty. Thus, the following insights into publication type and content are likely to be biased toward the biomedical field, and by the coding instructions and definitions at the National Library of Medicine. Despite these limitations, we believe that the content of highly relevant articles to the likely readership of this special issue are important to discover, and may provide useful insights to the field as a whole.

Puberty-related publications are predominantly empirical journal articles, although there is a fair representation of review articles. There were somewhat fewer meta-analyses, case reports, and qualitative studies. Case reports and qualitative studies are particularly useful for in-depth description, and should not be discounted. There were also surprisingly few meta-analyses that were indexed with puberty as a Major MeSH header in PubMed, and those published focused mainly on genes associated with puberty (e.g., Cousminer et al., 2013; Elks et al., 2013; Wu, Xing, Wang, & Zhang, 2016) environmental factors influencing age at menarche (e.g., father absense: Webster, Graber, Gesselman, Crosier, & Schember, 2014; smoking during pregnancy: Yermachenko & Dvornyk, 2015), or physical health outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular death: Charalampopoulos, McLoughlin, Elks, & Ong, 2014; type 2 diabetes: Janghorbani, Mansourian, & Hosseini, 2014; pancreatic cancer: Tang et al., 2015). We expected that more puberty-related meta-analyses would have appeared in our analyses. Meta-analyses may have been missed by our search strategy for this particular analysis (which was not a systematic review). A positive note is that meta-analyses on puberty are continually being published (e.g., Bertelloni, Massart, Miccoli, & Baroncelli, 2017; Deng et al., 2017; Durand, Tauber, Patel, & Dutailly, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Ullsperger & Nikolas, 2017). Given the breadth and quantity of research on puberty, meta-analyses will continue to be particularly useful for synthesizing the literature on puberty in the future.

Results from hand-coding abstracts suggest that there has been a relatively equal focus on predictors and effects of puberty (in conceptualization: many studies included in these groups were not longitudinal, and the vast majority could not speak to causality), each accounting for about one third of the puberty-related publications. The differences across time periods in the percentage of publications were small (< 6% change across hand-coded categories), although the relative proportion of articles examining puberty as a focal predictor slightly increased whereas the relative proportion of articles examining puberty as an outcome slightly decreased. Generally, there was an increase in substantive work (puberty as outcome, predictor/moderator, reviews/qualitative/etc., meta-analyses, puberty as descriptor of sample/not tested), relative to English abstracts with insufficient information, case studies, and puberty as a named covariate, which decreased in percentage. This is a promising trend, along with the total increase in puberty-related publications over time. It is particularly heartening to see that researchers are characterizing their sample in terms of pubertal maturation even when puberty is not a focal variable, and we hope that this trend continues.

In reviewing abstracts, one limitation of the field stood out. Even in articles where puberty was a main focus, as defined by the PubMed search (e.g., specifically coded where Puberty was a MeSH Major heading), there was a noticeable number of studies that included puberty, but “measured” it with age brackets (e.g., pre-pubertal = less than 13 years of age, pubertal = over 13 years of age). This strategy is inappropriate, as it does not truly measure the signs (e.g., Tanner stage) or biology (e.g., hormone changes) of puberty and will likely add to confusion rather than clarity of effects in the literature. Future research needs to lead by example, prioritizing and increasing publications that use proper methodology for measuring puberty mapping onto the construct of interest. A continued and strengthened emphasis on interdisciplinary science, and particularly for experts on puberty research to engage more with experts in related and relevant fields, would enhance the quality of future research where puberty is a relevant and important domain but not the central focus (see Susman, Marceau, Dockray and Ram, this issue). The other most egregious limitation of the abstracts was clarity in defining the role of puberty, for example as a covariate, predictor, or moderator. It is difficult to summarize a paper in a short abstract, but it is crucially important because in many instances researchers (unfortunately) read abstracts only, or at the very least use the abstract to decide whether to read the full publication. The best abstracts clearly articulated the model in a sentence (e.g., we tested whether pubertal timing moderated the effect of X on Y), and presented key sample characteristics and findings. Journal reviewers and editors could play an important role in enhancing such qualities by recommending such inclusions. In the future, writing logical, substantive, and clear abstracts is likely to increase the impact of puberty-related publications.

Hand-Coding Category Content.

A few main themes can be summarized from text-mining for content from the hand-coding categories. First, age at menarche is the most frequently studied index of puberty, although there are a range of hormonal and secondary sex characteristic measures represented. This is unsurprising, as it is the most easily measured (and recalled) component of puberty. However, age at menarche is only one measure of puberty and it is late in the process of puberty, and suffers from recall bias which affects accuracy of assessment. In the future, researchers would do well to include more types of measures of puberty that are in line with the question under study. This also contributes to a second major theme: there is a large gender gap in puberty-related publications, and this gap appears to be stable (there were about 1.67x more puberty-related publications with the term “girls” than with the term “boys” in each publication date range; see also Deardorff et al., this issue; Mendle et al., this issue). Puberty researchers have to continually attend to the gender composition of samples to ensure that boys’ puberty is well represented. A third theme is that measurements of puberty may have shifted towards stage/status/timing measures of secondary sex characteristics and away from hormonal measures, on average. The final theme from the content coding was that obesity- and diabetes-related constructs have consistently been examined in conjunction with puberty over time. These outcomes are undoubtedly importantly linked to pubertal development. From 2010–2015 far more constructs have been related to puberty, most notably depression/depressive symptoms. We suspect that in the future, puberty will be linked to more physical and mental health outcomes.

Impact

In general, puberty research has a higher impact in terms of citations than the journal averages when considering the top journals for puberty research. However, those top journals are not always particularly highly ranked: only about a quarter of the top journals were within the top 10% of journals in their respective fields (according to Web of Science categories), and the five top journals for puberty research had an average rank of 50% (of average caliber in their respective fields). Puberty researchers are encouraged to target top tier journals to increase the impact of puberty research. Including (in the abstract) concise, digestible and citable take-home messages of the findings, and of what puberty buys us in terms of knowledge over age (if applicable) may help to increase the impact of puberty research in the future. Researchers are also encouraged to target the journals at the top of the list of highly cited journals by puberty-related publications (included in Supplemental Table 9), as they have been the most highly cited by puberty research thus far.

Limitations

The analyses conducted herein provide useful information describing the landscape of puberty research. However, there are a number of limitations to this type of research (i.e., bibliometrics) that should be considered. First, bibliometric analysis relies to some extent on the correct application of MeSH or other terms and keywords. This indexing is not always consistent, nor is it equivalent across searches. The magnitude of the difference between the numbers of puberty papers identified through various databases shows how much indexing matters. For example, Google Scholar showed about 583,000 articles when searching for the words puberty or pubertal, which could appear anywhere in the article (including, for example, author, or the references list – this is by far the most inclusive database, and therefore returns a high quantity of irrelevant publications). Authors are encouraged to include puberty or pubertal as a named keyword in publications to increase the likelihood that the research will be indexed as a puberty publication. We attenuated this limitation by also searching for puberty/pubertal in the title and abstract. However, when puberty is not an original or primary focus or the publication, one of these terms may have been not be included in either. With regard to JRA, it is likely that citation metrics will increase as a result of JRA now being comprehensively indexed by PubMed.

A second limitation lies in the databases used. We chose in this paper to focus on Web of Science and PubMed, which we thought would together give us the best-rounded picture of this multidisciplinary and biologically based topic. There are many more databases that are relevant (e.g., Child Development and Adolescent Studies, Family Studies, PsycInfo, ERIC, or CINAHL, to name a few). Inclusion of these databases would likely have increased the prominence of developmental psychology and adolescence journals in our analyses, in particular. Further, databases continuously shift in terms of which journals are indexed and the publication dates indexed, meaning that important publications could have been missed. These limitations underscore why utilizing multiple databases with different foci and indexing processes are so important for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

A third limitation is in our hand-coding of abstracts. We only hand-coded from the PubMed search results, after limiting to studies of humans where puberty was a Major MeSH term. This search yielded far fewer results than the main searches included in this manuscript, and we believed the indexing to be more likely to capture publications where puberty was truly a focal variable or process. However, we undoubtedly missed swaths of the landscape of puberty-related publications where puberty was not a significant enough part of the paper to merit a major MeSH heading, and that were not indexed by PubMed at all. Further, the hand-coding was done by two individuals in a primary and secondary sweep, but reliability was not calculated. Our intent was to gain a broad understanding of the landscape, not a perfect quantification. Many of the ‘calls’ were subjective and other raters may have come to different conclusions. Thus, in full transparency, we include our coding record for others to examine. Further, due to the wide scope of this paper and time-intensiveness of coding, we did not code for the quality of the measure of puberty in each article, nor did we code for whether the measure was appropriate for what was being studied. This task is left to every reader of articles on puberty, and researchers are highly encouraged to carefully review extant literature for the quality and appropriateness of measures (information often not available in only the abstract; Dorn et al., 2006). These issues are central to the impact and rigor of puberty research, and important considerations of future research.

Finally, the text-mining was limited because we chose not to combine keywords and phrases into topical themes/terms (which itself is subjective, after the creation of the hand-coded categories was already fairly subjective). Thus, duplicate terms appear in the word clouds (e.g., estrogen and oestrogen), and many terms included in the top 100 lists are unhelpful in terms of understanding the content of articles (e.g., associations, study, effect, contrast). We highlighted terms we found to be most relevant in the results section and discussion, but a more thorough process of text mining and combining keywords and phrases are likely to yield more illustrative findings.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, we provide a panorama of what puberty research has looked like over the past ~25 years. In general, we are pleased with the state of the field. Puberty-related publications are increasing in sheer number, and have reach in many fields as befits an interdisciplinary science. The main audience of puberty-related publications are the fields of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Pediatrics, and Reproductive Biology. The primary publication types are empirical articles, examining puberty as a predictor/moderator of behavioral or health phenotypes, and the predictors of puberty. Age at menarche is most often a topic of puberty papers, girls are more often included than boys, and obesity- and diabetes-related phenotypes have been most frequently examined alongside puberty. Puberty-related publications generally have higher impact in terms of citations than the journal averages, among the top journals for puberty-related publications, although this was not true in all cases, and can be further improved. In the future, puberty researchers are encouraged to target high-impact, top-tier journals and under-represented fields in order to increase the impact and reach of puberty-related publications in the broader scientific community. Promoting clear, concise take-home messages in abstracts, and highlighting the importance of puberty even in publications where puberty is a secondary focus, and conducting meta-analyses may also help to increase the impact of puberty-related publications and their impact on advancing understanding in health and development in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Marceau was funded by K01 DA039288.

Footnotes

Web of Science outputs H-index, as well as the number of total citations with and without self-citations, and the number of citing articles with and without self-citations. Because the H-index favors quantity of publications and whole journals will necessarily have more articles than only the puberty-related publications of that journal, we do not present H-index (statistics available upon author request). In order to be more conservative, we focused only on the number of total citations and citing articles without self-citations. Notably, Web of Science only analyzes data sets by the number of times each article was cited if the number of total articles does not exceed 5000, and so citation analyses were not possible for journals that published more than 5000 articles (which occurred particularly in the larger publication date interval: 1990–2016).

According to PsycInfo, JRA published 918 total articles from 1990–2016, with 30 containing puberty/pubertal in keywords.

References

- Aylwin C, Toro C, Shirtcliff E, Lomniczi A (this issue). Emerging genetic and epigenetic mechanisms underlying pubertal maturation. Journal of Research on Adolescence [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelloni S, Massart F, Miccoli M, & Baroncelli GI (2017). Adult height after spontaneous pubertal growth or GnRH analog treatment in girls with early puberty: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Pediatrics, 176(6), 697–704. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-2898-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charalampopoulos D, McLoughlin A, Elks CE, & Ong KK (2014). Age at menarche and risks of all-cause and cardiovascular death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 180(1), 29–40. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousminer DL, Berry DJ, Timpson NJ, Ang W, Thiering E, Byrne EM, … Widen E (2013). Genome-wide association and longitudinal analyses reveal genetic loci linking pubertal height growth, pubertal timing and childhood adiposity. Human Molecular Genetics, 22(13), 2735–2747. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley-Low J (2006). Bibliometric analysis of the American Journal of Veterinary Research to produce a list of core veterinary medicine journals. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 94(4), 430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Hoyt L, Carter R, and Shirtcliff E (under review, this issue). Exploring the complexity of puberty: Understudied populations and processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Li W, Luo Y, Liu S, Wen Y, & Liu Q (2017). Association between Small Fetuses and Puberty Timing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(11), 1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, & Biro FM (2011). Puberty and Its Measurement: A Decade in Review. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 180–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00722.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durand A, Tauber M, Patel B, & Dutailly P (2017). Meta-Analysis of Paediatric Patients with Central Precocious Puberty Treated with Intramuscular Triptorelin 11.25 mg 3-Month Prolonged-Release Formulation. Hormone Research in Paediatrics, 87(4), 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elks CE, Ong KK, Scott RA, van der Schouw YT, Brand JS, Wark PA, … Wareham NJ (2013). Age at menarche and type 2 diabetes risk: the EPIC-InterAct study. Diabetes Care, 36(11), 3526–3534. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield E (1977). Introducing citation classics--human side of scientific reports. Current Contents, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann E, Glatt V, & Tetsworth K (2017). Worldwide orthopaedic research activity 2010–2014: Publication rates in the top 15 orthopaedic journals related to population size and gross domestic product. World Journal of Orthopedics, 8(6), 514–523. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i6.514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosey G, & Melfi V (2014). Human-animal interactions, relationships and bonds: A review and analysis of the literature. International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 27(1), 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Janghorbani M, Mansourian M, & Hosseini E (2014). Systematic review and meta-analysis of age at menarche and risk of type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetologica, 51(4), 519–528. doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0579-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball R, Stephens J, Hubbard D, & Pickett C (2013). A Citation Analysis of Atmospheric Science Publications by Faculty at Texas A&M University. College & Research Libraries, 74(4), 356–367. [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Liu Q, Deng X, Chen Y, Liu S, & Story M (2017). Association between Obesity and Puberty Timing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(10), 1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J (2014). Beyond pubertal timing: New directions for studying individual differences in development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(3), 215–219. doi: 10.1177/0963721414530144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Beltz A, Carter R & Dorn LD (in press). Understanding puberty and its measurement: Ideas for research in a new generation of youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten MJ, (2010). Weight status continuity and change from adolescence to young adulthood: examining disease and health risk conditions. Obesity, 18(7), 1423–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sing DC, Jain D, & Ouyang D (2017). Gender trends in authorship of spine-related academic literature - a 39-year perspective. The Spine Journal: Official Journal of the North American Spine Society. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susman EJ, Marceau K, Dockray S & Ram N (under review this issue). Interdisciplinary Work is Essential for Research on Puberty: Complexity and Dynamism in Action. Journal of Research on Adolescence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B, Lv J, Li Y, Yuan S, Wang Z, & He S (2015). Relationship between female hormonal and menstrual factors and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore), 94(7), e177. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullsperger JM, & Nikolas MA (2017). A meta-analytic review of the association between pubertal timing and psychopathology in adolescence: Are there sex differences in risk? Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 903–938. doi: 10.1037/bul0000106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster GD, Graber JA, Gesselman AN, Crosier BS, & Schember TO (2014). A life history theory of father absence and menarche: a meta-analysis. Evolutionary Psychology, 12(2), 273–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Xing XK, Wang KJ, & Zhang L (2016). Lack of association between the ESR1 rs9340799 polymorphism and age at menarche: a meta-analysis. Genetic and Molecular Research, 15(3). doi: 10.4238/gmr.15038598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yermachenko A, & Dvornyk V (2015). A meta-analysis provides evidence that prenatal smoking exposure decreases age at menarche. Reprodroductive Toxicology, 58, 222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2015.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.